Abstract

cAMP response-element binding protein (CREB) dependent genes are differentially expressed in brains of temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) patients and also in animal models of TLE. Previous studies have demonstrated the importance of CREB regulated transcription in TLE. However, the role of the key regulator of CREB activity, CREB-regulated transcription coactivator 1 (CRTC1), has not been explored in epilepsy. In the present study the pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (SE) model of TLE was used to study the regulation of CRTC1 during and following SE. Nuclear translocation of CRTC1 is critical for its transcriptional activity, and dephosphorylation at serine 151 residue via calcineurin phosphatase regulates cytoplasmic to nuclear transit of CRTC1. Here, we examined the localization and phosphorylation (Ser151) of CRTC1 in SE-induced rat hippocampus at two different time points after SE onset.

One hour after SE onset, we found that CRTC1 translocates to the nucleus of CA1 neurons but not CA3 or dentate granule neurons. We further found that this CRTC1 nuclear localization is independent of Ser151 dephosphorylation since we did not detect any difference in dephosphorylation of Ser151 between control and SE animals at this time point. In contrast, 48 hours after SE CRTC1 shows increased nuclear localization in the dentate gyrus of the SE-induced rats. At 48 hours after SE, FK506 treatment blocked CRTC1 nuclear localization and dephosphorylation of Ser151.

Our results provide evidence that CREB cofactor CRTC1 translocates into the nucleus of a distinct subset of hippocampal neurons during and following SE and this translocalization is regulated by calcineurin at a later time point following SE. Nuclear CRTC1 can bind to CREB possibly altering transcription during epileptogenesis.

Keywords: CRTC1, CREB, Status epileptics, Epilepsy, FK506, Calcineurin

1. Introduction

Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders with approximately one-third of the patients unresponsive to current treatments (WHO, May 2015). To find novel therapeutics for epilepsy, understanding the process of epilepsy development or epileptogenesis is of utmost importance. Various studies done in animal models of epilepsy and human epileptic brains show that gene expression is altered during epileptogenesis. (Pitkanen et al., 2007, Beaumont et al., 2012, Venugopal et al., 2012, Hansen et al., 2014)

In animal models alterations in gene expression start during the brain insult including status epilepticus (SE) and continues throughout the process of epileptogenesis (Okamoto et al., 2010, Hansen et al., 2014). Interestingly, a majority of the genes altered in epilepsy are regulated by cAMP-responsive element-binding protein (CREB) (Beaumont et al., 2012, Hansen et al., 2014). Studies from our laboratory and others have shown that CREB activity increases in epilepsy and decreasing CREB activity can suppress spontaneous seizures and also reduce the duration of SE in a rodent model of epilepsy (Lopez de Armentia et al., 2007, Zhu et al., 2012, Hansen et al., 2014, Zhu et al., 2015).

CREB-regulated transcriptional coactivator (CRTC), also known as transducer of regulated CREB activity (TORC), has recently emerged as a unique CREB coactivator that binds to the bZIP domain of CREB and regulates its transcriptional activity (Conkright et al., 2003). There are three known isoforms of CRTC (CRTC1, 2, and 3), of which CRTC1 is the most abundantly expressed isoform in the hippocampus (Watts et al., 2011).

CRTC1 is a serine and threonine rich protein (Nonaka et al., 2014), and the nuclear translocation of CRTC1 is mediated by its phosphorylation state at different serine residues that are regulated by calcineurin phosphatase and different kinases including MEKK1, SIK/ AMPK, MARK2(Sasaki et al., 2011) (Conkright et al., 2003, Bittinger et al., 2004, Siu et al., 2008, Mair et al., 2011, Nonaka et al., 2014). The most studied phosphorylation site of CRTC1 is serine151 (Ser151). CRTC1 phosphorylated at Ser151 is concentrated in the cytoplasm bound to anchor protein 14–3-3 (Ch’ng et al., 2012). Dephosphorylation at Ser151 by calcineurin phosphatase allows CRTC1 to translocate to the nucleus where it interacts with CREB and specifies which genes are transcribed (Altarejos et al., 2008, Jeong et al., 2012, Parra-Damas et al., 2014). Interestingly, CRTC1 has been implicated in the neuronal survival after ischemia (Sasaki et al., 2011), regulation of circadian clock (Sakamoto et al., 2013), and long-term fear memory formation (Nonaka et al., 2014). Despite the importance of CREB-CRTC1 regulated transcription in many critical neurological processes and the significance of CREB regulated transcription in epilepsy, CRTC1’s role in epilepsy has not been examined.

In the current study, we utilized pilocarpine-induced SE, a common rodent model of epileptogenesis(Curia et al., 2008) to examine CRTC1 regulation during and following SE. We measured the subcellular localization and the phosphorylation of CRTC1 (Ser151) in the hippocampus of SE and control rats at two time points, during SE (15 minutes and 1 hour) and post-SE (48 hours). To begin to understand the mechanism of CRTC1 nuclear translocation in epilepsy, we measured calcineurin phosphatase activity and examined the effect of calcineurin phosphatase inhibitor FK506 (Pardo et al., 2006, Chen et al., 2014) on the localization and phosphorylation of CRTC1 in the pilocarpine-induced rats. We found that SE causes nuclear translocation of CRTC1 in different subsets of hippocampal neurons at different time points tested. We hypothesize that the nuclear localization of CRTC1 allows its interaction with CREB, which might contribute to epileptogenesis.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Animals

Two month old male Sprague Dawley (SD) rats (Charles River Laboratories International, CA) were provided with unrestricted access to food and water in temperature and humidity controlled housing with a 12 hours light- 12 hours dark cycle (lights on 7:00 AM). The Stanford Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all the protocols used.

2.2. Induction of status epilepticus

Two month old male SD rats were injected with 1mg/kg methyl-scopolamine intraperitoneally (IP) (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., MO) followed by IP injection of 385mg/kg body weight of pilocarpine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., MO). Control rats received sub-convulsive dose of 38.5mg/kg body weight of pilocarpine. Rats were monitored for behavioral seizures and SE induction onset was measured from the start of the first stage five seizure on racine scale (Racine, 1972). One hour after the induction of SE, 6mg/kg diazepam (Hospira Inc., IL) was given by IP injection to both the SE-induced and control rats. The seizure group received an additional half dose (3 mg/kg) of diazepam every two hours after the initial diazepam injection till all behavioral seizures ended.

2.3. FK506 treatment

FK506 was dissolved in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., MO) as a stock of 5mg/ml and a dose of 5mg/kg of body weight was given to rats as IP injection at the times stated in the experiments. This dose of FK506 has been effectively used in other rodent brain studies (Pardo et al., 2006). Control animals received an equal volume of DMSO (vehicle). No behavioral or physiological changes were detected in the rats given IP injection of DMSO as vehicle at this concentration and dosage as used by other studies (Neasta et al., 2010)

2.4. Immunofluorescence

Under the influence of 3% isoflurane as anesthesia, status epilepticus-induced and control rats underwent intra-cardiac perfusion with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., MO) 15 minutes, 1 hour or 48 hours after induction of SE. Rats were euthanized while deeply anesthetized, via exsanguination and vascular perfusion. The brains were harvested and post fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by dehydration with 30% sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., MO) for two days at 4°C. After freezing on dry ice, 40-micron sections of brain were cut using a sliding microtome. Free floating sections were blocked in PBS containing 0.1% TritonX-100 and 3% goat serum, followed by overnight incubation in primary antibody anti-CRTC1 (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology, MA) at 4°C followed by 4 hours incubation in Alexa Flour 488 conjugated rabbit IgG (1:400, Life Technologies, NY) at room temperature. The sections were then mounted using VECTASHIELD® mounting medium with DAPI (4’, 6- diamidino- 2-phenylindole) (Vector Laboratories, CA) for staining nuclei. Sections lacking primary antibody incubation were used as a control for CRTC1 antibody specificity. Three brain sections per rat were processed for immunohistochemistry and observed for persistence in the pattern of staining across the sections under a fluorescent microscope. Confocal images of hippocampal sub regions from one brain section per animal were captured using microscope (Leica Microsystems, IL) with a 63X magnification oil lens. Nuclei (DAPI) and CRTC1 (Alexa flour 488) fluorescence signals were captured using sequential acquisition to have separate image files for each. These confocal images were then used for quantification of nuclear CRTC1. Quantification of the nuclear CRTC1 was done using cell counter plugin of Image J64. Briefly, an observer blinded to treatment marked 25 healthy nuclei on each DAPI image, these selections were transferred to its corresponding CRTC1 (Alexa488 stained) image and the marked nuclei positive for CRTC1 staining were counted. A ratio of CRTC1 positive nuclei to total number of nuclei counted was used to compare the nuclear localization of CRTC1 across different samples. Ordinary one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni multiple comparisons was performed using Prism 6 and values were plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

2.5. Calcineurin assay

Hippocampi were quickly dissected from SE-induced and control rats euthanized at different time points after SE induction and frozen in dry ice. Hippocampal lysates were prepared using reagents provided in the calcineurin cellular activity assay kit (BML-AK816–0001, Enzo Life Sciences, NY) and assay was performed following manufacturer’s instructions. The absorbance values from the assay were converted into amount of PO4 released by calcineurin using manufacturer’s instructions. All values were normalized to the values from control animals and plotted. Two- tailed unpaired t-test was performed for statistical significance using Prism 6.0 software.

2.6. Immunoblotting

Status epilepticus-induced and control rats were euthanized while deeply anesthetized using 3% isoflurane at the specific time points as mentioned in the experimental designs after induction of SE and hippocampi were quickly dissected and frozen in dry ice. Hippocampus was homogenized in lysis buffer (150mM NaCl, 50mM Tris pH 7.4, 1mM EDTA, 1% TritonX-100, 10 % glycerol, 1mM PMSF, 1X protease inhibitor cocktail, 0.001M Na3VO4 and 1X phosphatase inhibitor cocktail) and approximately 300 mg of protein was immunoprecipitated with anti-CRTC1 (Cell Signaling Technology, MA) using Dynabeads (Life Technologies, NY) to concentrate phosphoCRTC1 protein to facilitate detection by anti-phosphoCRTC1 Ser151 antibody. Immunoprecipitated proteins were eluted from beads by boiling in SDS buffer and separated on a denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The proteins were then transferred on nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 5% Bovine serum albumin in Tris buffered saline supplemented with 0.01% Tween 20 for 1 hour at room temperature. The blocked membranes were incubated with anti-phosphoCRTC1 Ser151 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, Cat No# 3359)(Jeong et al., 2012) overnight at 4°C followed by secondary anti-rabbit IgG (1:20,000, Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, PA) for 1 hour at room temperature. Immunoblots were developed with enhanced chemiluminescence (Thermo fisher Scientific, IL) on X-ray films. The membranes were stripped and reprobed with anti-CRTC1 (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA) antibody following similar procedure. Alternatively, anti-phosphoCRTC1 Ser151 antibody (1:1000, Cat No # ABE560, EMD Millipore, MA)(Altarejos et al., 2008) was used for detecting phosphorylated CRTC1 directly from hippocampal lysates without immunoprecipitating total CRTC1 protein. For detecting ICER and GABRA1, anti-CREM X12 (1:1000, SantaCruz Biotech) and anti-GABAA receptor alpha1 (1:10,000, EMD Millipore, MA) were used respectively. Membranes were stripped and probed with anti-tubulin (1:20,000, Cell Signaling Technology, MA) for loading control. Quantitative analysis of the intensity of the bands of interest on the X-ray films was done using Image J64 software, and statistical analysis (two-tailed unpaired t-test) was performed using Prism 6.0.

2.7. Real-time PCR

As described previously (Zhu et al., 2015), RNA was extracted from whole hippocampus using the RNAqueous®-4PCR Total RNA Isolation Kit (Life Technologies, NY) and complementary DNA (cDNA) using 500 ng of RNA per sample was reverse transcribed with SuperScript II reverse transcription kit (Life Technologies, NY). Twenty microliter reactions were carried out in 96-well plates with either the gene of interest; GABRA1 Mm00439046_m1, ICER Mm01230944_g1 or PPIA (cyclophilin) (Rn00690933_m1), ddH2O, Taqman Universal PCR master mix (Life Technologies, NY). Approximately 50 ηg of sample cDNA was used for each reaction. For each sample, two sets of triplicates, one set with the probe for the gene of interest and one for PPIA (cyclophilin) were run. No difference was detected in PPIA mRNA levels between treatment groups. Real-time PCR assays were carried out on a StepOnePlus™ Real-Time PCR System (Thermofisher Scientific, MA) with the settings, 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, and then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 secs and 60 °C for 1 min. Ordinary one-way ANOVA test with Bonferroni multiple comparisons was performed using Prism 6 and values were plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results

3.1. During SE, CRTC1 translocates to the nucleus of CA1 pyramidal neurons

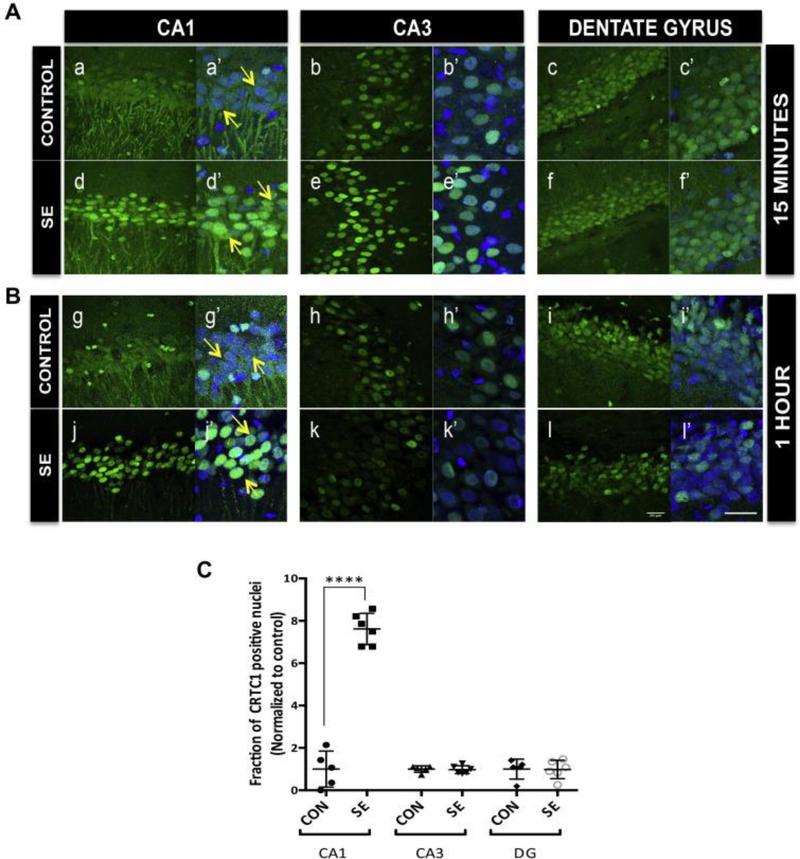

To investigate if CRTC1, the CREB cofactor, is located in the nucleus and capable of co-regulating CREB-mediated transcription during SE, we measured CRTC1 subcellular localization in the hippocampus during pilocarpine-induced SE using confocal microscopy. Status epilepticus (SE) was induced, and brains were fixed at 15 minutes or 1 hour after SE onset. In the majority of CA1 pyramidal neurons, CRTC1 staining (in green) colocalized with the nuclear staining (DAPI in blue), suggesting nuclear localization of CRTC1 starts as early as 15 minutes after pilocarpine-induced SE onset compared to control rats (Figure 1A panel a) and was also observed at 1 hour after SE onset (1B panels g and j). CA3 pyramidal neurons (Figure 1A panels b, e and 1B panels h, k) and dentate granule neurons (DG) (Figure 1A panels c, f and 1B panels i, l) of the hippocampus did not show a consistent difference in CRTC1 localization across the SE and control animals at either 15 minutes or one hour after the onset of SE. A combined quantitative analysis for images taken from the SE-induced (N=6) and control animals (N=5) during SE showed significant increase (~ 8 fold) in the nuclear localization of CRTC1 only in the CA1 region of SE-induced animals compared to control animals (p<0.0001, ANOVA).

Fig. 1.

Nuclear localization of CRTC1 in hippocampal neurons during status epilepticus. Representative confocal images of rat hippocampus perfused and fixed A. Fifteen minutes and B. One hour after SE onset are shown. Forty-micron sections were stained for CRTC1 in green and counterstained with nuclear dye DAPI in blue. (A) Fifteen minutes after the onset of a stage five seizure there was intense nuclear staining for CRTC1 in CA1 region of SE rats (d and d′) compared to diffuse staining in control rats (a and a′) (marked with arrows). There was no consistent difference in the CRTC1 staining pattern in CA3 or dentate gyrus (DG) regions between SE (e, e′ and f, f′) and control rats (b, b′ and c, c′) 15 min after SE onset. (B) The intense nuclear staining for CRTC1 in CA1 region persists at 1 h after SE onset. Nuclear staining in SE rats (j and j′) compared to diffuse staining in control rats (g and g′) (marked with arrows). No difference in the CRTC1 staining pattern in CA3 or DG regions between SE (k, k′ and l, l′) and control rats (h, h′ and i, i′) at 1 h after onset of SE. Images a′, b′, c′, d′, e′, f′, g′, h′, i′, j′, k′, I′ are magnified merged images of DAPI and CRTC1. Scale bars are 20 μm. (C) Quantification of collective confocal images from 15 min and 1 h after SE onset was done. Twenty-five nuclei were marked in each image and the fraction of nuclei positive for CRTC1 staining was determined and plotted for SE-induced (N = 6) and control rats (N = 5) for CA1, CA3 and DG sub region of hippocampus. Values are plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ****p-value < 0.0001 ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comcomparisons. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.2. Calcineurin activity increased during SE

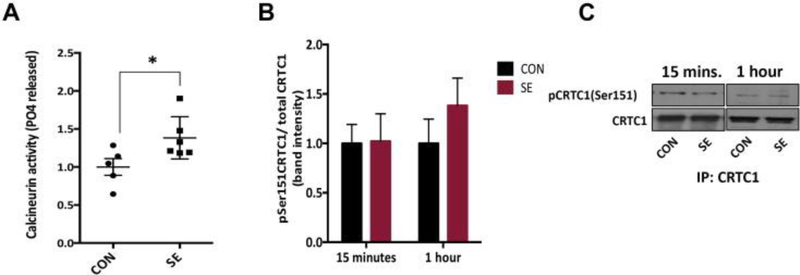

Nuclear localization of CRTC1 is regulated by dephosphorylation at certain critical residues including Ser151 previously shown to be a site dephosphorylated by calcineurin phosphatase (Altarejos et al., 2008, Parra-Damas et al., 2014). We first measured the calcineurin activity in the hippocampal lysates of SE-induced and control rats. As reported by others (Kurz et al., 2001), calcineurin activity increased ~ 1.4 fold (p-value= 0.0404, two-tailed unpaired t-test) in the hippocampus of SE-induced rats (N=6) compared to control rats (N=5), 1 hour after SE induction (Figure 2A).

Fig. 2.

Increased calcineurin activity but no change in the phosphorylation of CRTC1 at Ser151 during SE. The hippocampi harvested from SE-induced and control rats 15 min or 1 h after SE induction were lysed for calcineurin activity assay or immunoblotting for phosphoCRTC1 (Ser151) levels. (A) Values (mean ± SD) of the PO4 released by calcineurin in the assay were averaged from duplicate experiments and plotted as fold difference between SE (N = 6) and control (N = 5) samples 1 h after SE induction. Unpaired t-test *p = 0.0404. (B) Ratio of the band intensities of the phoshoCRTC1 and CRTC1 protein bands were calculated from the western blots from the immunoprecipitated hippocampal lysates of SE and control rats 15 min and 1 h from SE onset (N = 5–8). Experiments were done in duplicate and average values from two replicate experiments (mean ± SD) were plotted. Unpaired t-test p > 0.05. (C) Representative western blot image for each time point is shown.

Next we measured the ratio of phosphoCRTC1 Ser151/ total CRTC1 in the whole hippocampal lysates of the SE-induced and control rats using western blotting of immunoprecipitated CRTC1 proteins as described in material and method at two time points during SE. As shown in Figure 2B and C, no difference was found in the phosphoCRTC1 Ser151/ total CRTC1 levels between SE-induced (N=8 and 7, respectively) or control rats (N=5 and 6, respectively), 15 minutes or 1 hour after SE induction. Total CRTC1 protein levels were similar in all animals (data not shown).

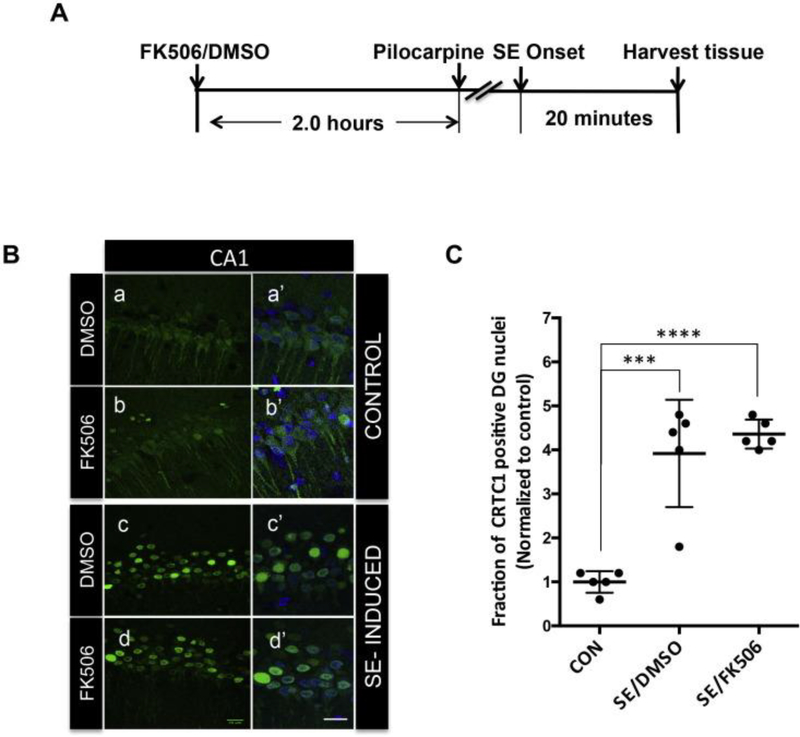

3.3. Calcineurin inhibitor FK506 did not block the nuclear localization of CRTC1 during SE

While we did not detect a significant decrease in the phosphoCRTC1 Ser151/ total CRTC1 ratio during SE we did, however, detect increased levels of calcineurin activity at this time point. To investigate if calcineurin regulates the nuclear localization of CRTC1 during SE, we used FK506, a well-studied inhibitor of calcineurin (Pardo et al., 2006, Chen et al., 2014). First, we treated rats with a single dose of 5mg/kg body weight FK506 or vehicle (DMSO) 2.0 hours before pilocarpine injection. This dose and time point has been shown to be effective for calcineurin inhibition by FK506 in rodent brain (Pardo et al., 2006). The animals were perfused and the brains were fixed 15–30 minutes after SE onset as shown in Figure 3A. We detected similar nuclear localization of CRTC1 in the CA1 neurons of the FK506- or DMSO-treated SE rats (Figure 3B panels c and d). As shown in Figure 3B panels a and b, the control animals showed no nuclear staining irrespective of the treatment. No difference was detected in the staining pattern in the other regions of the hippocampus between the FK506- or DMSO-treated SE and control rats (data not shown), suggesting that FK506 did not block the nuclear localization of CRTC1 in CA1 neurons during SE. A quantitative analysis (Figure 3C) from images taken from DMSO- and FK506- treated rats and control rats (N=5 each) shows a significant increase (~ 4 fold) increase in the fraction of CRTC1 positive nuclei in both DMSO-and FK506- treated SE-induced rats (p< 0.0001, ANOVA) compared to controls. However, no difference was seen in the quantitative analysis between DMSO- treated and FK506- treated SE induced rats (Figure 3C).

Fig. 3.

Calcineurin inhibitor FK506 did not change subcellular localization of CRTC1during SE. (A) Schematic showing the experimental design for calcineurin inhibition using FK506 treatment. (B) Representative confocal images of the CA1 region of the hippocampus of the SE-induced or control rats treated with 1 dose of FK506 or DMSO, 2 h before SE induction as shown in the schematic A. Forty-micron sections were stained for CRTC1 in green and counterstained with nuclear dye DAPI in blue. 15 min after SE onset there was intense nuclear staining for CRTC1 in CA1 of DMSO-treated SE animals (c and c′) compared to diffuse staining in control animals (a, a′ and b, b′). Nuclear staining was detected in the FK506-treated SE rats (d, d′) which was similar to the DMSO-treated SE rats. Images a′, b′, c′, d′ are magnified merged images of DAPI and CRTC1. Scale bars are 20 μm. (C) Quantification of confocal images from CA1 region was done as explained earlier. Fraction of nuclei positive for CRTC1 staining was determined and plotted for SE-induced DMSO-treated (N = 5) and FK506-treated (N = 5) and control rats (N = 5). Values were plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ANOVA p-value < 0.0001. Bonferroni multiple comparisons ***p-value < 0.001 and ****p-value < 0.0001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

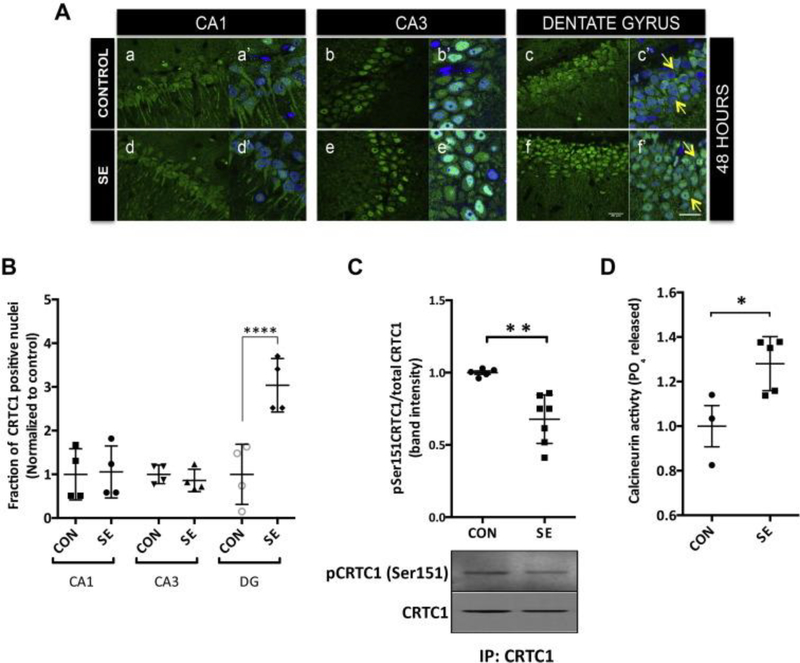

3.4. Following SE, CRTC1 nuclear localization increased in DG neurons

We performed CRTC1 immunofluorescence of the rat hippocampus 48 hours after SE. Interestingly in contrast to SE time points there was increased nuclear staining of CRTC1 in DG neurons of SE rats compared to control rats (Figure 4A panels c and f). A four-fold increase (p<0.0001, ANOVA) in the fraction of DG nuclei showing CRTC1 immunofluorescence was found in the SE-induced rats (N=4) when compared to control rats (N=4) as shown in the figure 4B. The CA3 region showed variation across animals in the number of neurons having CRTC1 immunofluorescence colocalized with DAPI staining (Figure 4A panels b and e). The CA1 region showed no difference in CRTC1immunostaining between SE or control rats at this time point (Figure 4A panels a and d). No difference was observed in the number of nuclei stained with CRTC1immunofluouresence in the CA1 and CA3 region of SE-induced and control rats (Figure 4B).

Fig. 4.

Increased nuclear localization of CRTC1 in dentate granule neurons and dephosphorylation of CRTC1 ser151 48 h after SE. (A) Representative confocal images of rat hippocampus perfused and fixed 48 h after SE onset. Forty-micron sections were stained for CRTC1 in green and counterstained with nuclear dye DAPI in blue. 48 h after SE onset there was intense nuclear staining for CRTC1 in dentate gyrus (DG) of SE animals (f and f′) compared to diffuse staining in control animals (c and c′) (marked with arrows). There was no consistent difference in the CRTC1 staining pattern in CA1 or CA3 regions between SE (d, d′ and e, e′) and control animals (a, a′ and b, b′) at 48 h after onset of SE. Images a′, b′, c′, d′, e′, f′ are magnified merged images of DAPI and CRTC1. Scale bars are 20 μm. (B) Quantification of confocal images for 48 h after SE onset. The fraction of nuclei positive for CRTC1 staining was determined and plotted for SE-induced (N = 4) and control rats (N = 4) for CA1, CA3 and DG sub regions of hippocampus. Values are plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ****p-value < 0.0001 ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparisons. (C) A significant decrease in the level of phosphorylated CRTC1 (Ser151) in SE-induced compared to control rats. Ratio of the band intensities of the phosphoCRTC1 and CRTC1 protein bands were calculated from the western blots run from hippocampal lysates of SE (N = 7) and control rats (N = 5) 48 h from SE onset. Representative western blot image is shown below the graph. Values averaged from duplicate experiments were plotted as mean ± SD. Unpaired t-test **p = 0.0019. (D) Values (mean ± SD) of the PO4 released by calcineurin in the assay are plotted as fold difference between control (N = 3) and SE (N = 5) samples 48 h after SE induction. The plotted values are average of duplicate experiments, unpaired t-test *p = 0.0299. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

3.5. CRTC1 Ser151 is dephosphorylated 48 hours after status epilepticus

We performed immunoblot analysis of the hippocampal lysates of SE and control rats 48 hours after SE onset using phosphoCRTC1 Ser151 antibody. In contrast to our findings during SE, we detected ~ 1.5 fold reduction (p-value=0.0019, two-tailed unpaired t-test) in the phosphoCRTC1 Ser151/total CRTC1 ratio in SE animals (N=7) compared to control (N=5) (Figure 4C). Suggesting decreased phosphorylation or increased dephosphorylation of CRTC1 at Ser151, 48 hours after SE induction. The level of total CRTC1 protein across all the SE and control rats was unchanged (data not shown).

We detected a small but significant increase ~1.3 fold (p-value= 0.0299, two-tailed unpaired t-test) in the calcineurin activity of SE-induced rats (N=5) compared to control rats (N=3) hippocampus, 48 hours after SE induction (Figure 4D).

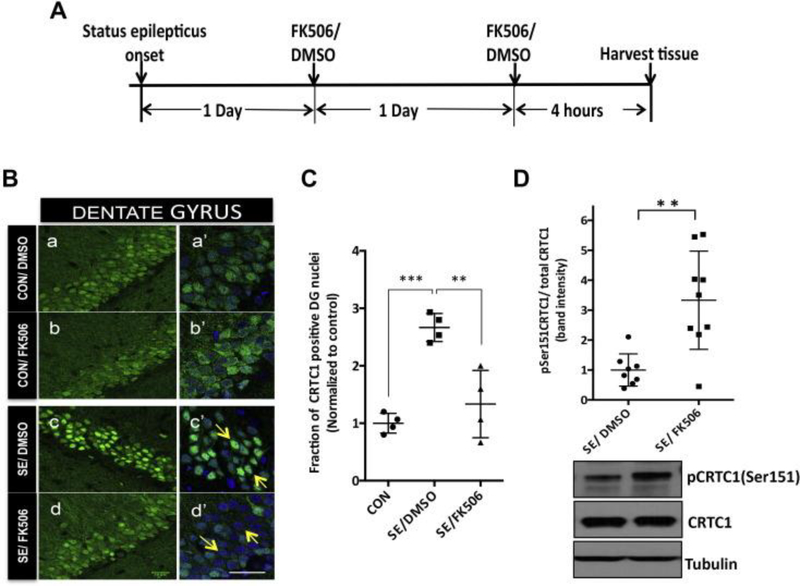

3.6. Calcineurin inhibitor FK506 increased CRTC1 Ser151 phosphorylation and decreased nuclear localization of CRTC1 following SE

To determine if dephosphorylation of CRTC1 Ser151 in the hippocampus at 48 hours after SE onset was due to calcineurin we again used FK506, the inhibitor of calcineurin. We induced SE in rats and gave them two doses of 5mg/kg body weight of FK506 or equal volume of DMSO at 24 and 48 hours after SE induction and rats were sacrificed approximately 4 hours after the second dose (Figure 5A). We observed decreased nuclear staining for CRTC1 in the DG region of the SE rats treated with FK506 compared to the DMSO (Figure 5B panels c and d, marked with arrows, and quantified in figure 5C). There was a significant increase (~2.5 fold) in the fraction of CRTC1 positive DG nuclei in the DMSO-treated SE-induced (N=4) compared to control rats (N=4) (p<0.001, ANOVA) as shown previously (Figure 4A and B). The fraction of DG nuclei with CRTC1 immunofluorescence was significantly reduced in FK506-treated SE-induced rats (N=4) (p<0.01, ANOVA) and was similar to control DG nuclear staining. The DG region of the control rats did not show any difference in CRTC1 immunofluorescence with or without FK506 treatment (Figure 5B, panels a and b). We did not find any consistent difference in the staining of CRTC1 with FK506 in other regions of the hippocampus (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Calcineurin inhibitor FK506 reduces CRTC1 nuclear localization and Ser151 dephosphorylation of CRTC1 following SE. (A) Schematic showing the experimental design for calcineurin inhibition using FK506 treatment. Rats were either perfused and the brains were fixed for immunohistochemical analysis or hippocampi harvested for immunoblot analysis 48 h after SE onset. (B) Representative confocal images of DG region of the SE-induced or control rats treated with 2 doses of FK506 or DMSO as shown in the schematic A. Forty-micron sections were stained for CRTC1 in green and counterstained with nuclear dye DAPI in blue. Forty-eight hours after SE onset there was intense nuclear CRTC1staining in DG of DMSO-treated SE animals (c and c′) compared to diffuse staining in control animals (a, a′ and b, b′) (marked with arrows). The nuclear staining in the FK506-treated SE-induced rats decreased significantly (d, d′) (marked with arrows). Images a′, b′, c′, d′ are magnified merged images of DAPI and CRTC1. Scale bars are 20 μm. (C) Quantification of confocal images from DG region was done as explained earlier. Fraction of nuclei positive for CRTC1 staining was determined and plotted for SE-induced DMSO-treated (N = 4) and FK506-treated (N = 4) and control rats (N = 4). Values were plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ANOVA p-value = 0.0004. Bonferroni multiple comparisons **p-value < 0.01 and ***p-value < 0.001. (D) There was a significant increase in the phospho CRTC1(Ser151) level in the FK506-treated SE rats (N = 9) compared to DMSO-treated SE rats (N = 8) 48 h after SE onset. Ratio of the band intensities of the pCRTC1 and CRTC1 protein bands were calculated from the western blots run from hippocampal lysates of FK506- or DMSO-treated SE rats. Representative western blot image is shown below the graph. The values were normalized for loading control with β-tubulin. Values averaged from duplicate experiments were plotted as mean ± SD. Unpaired t-test, **p = 0.0017. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

There was a ~3 fold increase (p-value= 0.0017, two-tailed unpaired t-test) in the Ser 151 phosphoCRTC1/total CRTC1 level in SE-induced rats with FK506 treatment (N=9) compared to those with DMSO treatment (N=8). Suggesting that calcineurin inhibitor FK506 blocks the dephosphorylation of CRTC1 at Ser151 residue 48 hours after SE (Figure 5C). Post-SE induction of increased calcineurin activity is a strong candidate for dephosphorylating CRTC1 causing its nuclear translocation in DG neurons 48 hours after SE.

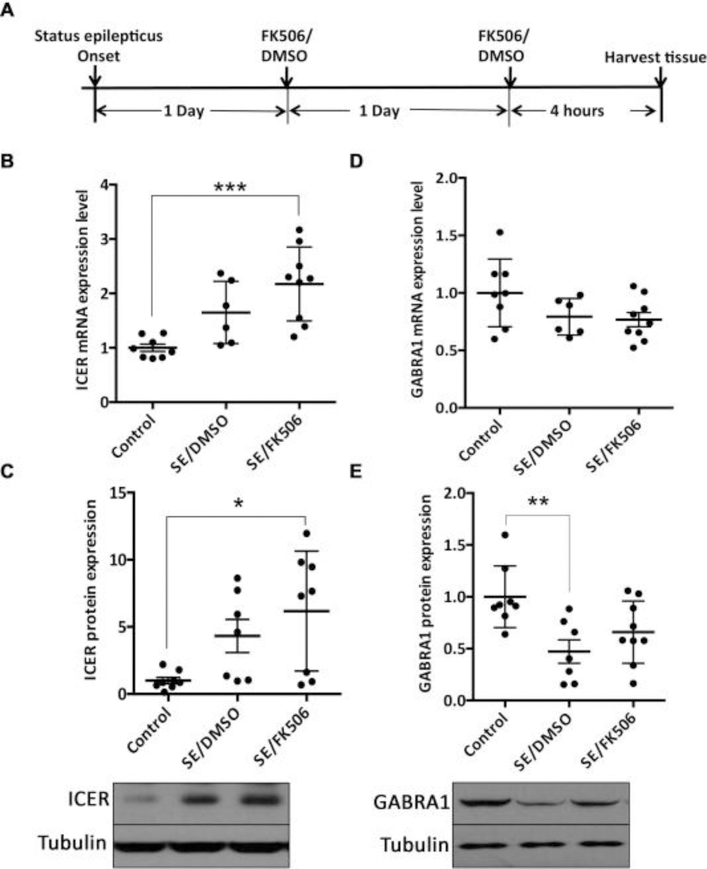

3.7. Calcineurin blocker FK506 did not modulate the expression of ICER and GABRA1, known targets for transcription regulation by CREB, 48 hours after SE induction

As we found a reduction in the nuclear localized CRTC1 on calcineurin inhibition in SE induced rats 48 hours after SE induction, we wanted to explore whether nuclear localization of CRTC1 induced by SE is associated with transcription of CREB regulated genes. We measured the expression of ICER (inducible cAMP early repressor) and GABRA1 (gamma -aminobutyric acid receptor alpha 1) in the hippocampus. Both Icer and Gabra1 are known targets of CREB and are regulated in pilocarpine induced SE (Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998, Lund et al., 2008, Zhu et al., 2012). Using qPCR and western blotting we checked the mRNA and protein levels of the two genes in the hippocampus of the control (N=8), vehicle (N=7) OR FK506-treated (N=9) SE-induced rats, 48 hours after SE induction as shown in the schematic Figure 6A. As shown in Figure 6B and C, ICER showed increase in both mRNA and protein levels in SE induced animals compared to control, however, we could not detect any significant difference between vehicle- and FK506-treated SE-induced rats. Similarly, GABRA1 showed a decrease in the protein levels between control and vehicle- treated SE-induced rats. However no significant difference was found in either mRNA or protein expression levels of GABRA1 between vehicle-and FK506-treated SE-induced rats (Figure 6D and E).

Fig. 6.

Calcineurin inhibitor FK506 did not modulate the expression of ICER and GABRA1 following SE. (A) Schematic showing the experimental design for calcineurin inhibition using FK506 treatment. Hippocampi were harvested from rats for RNA isolation or immunoblot analysis 48 h after SE onset. Hippocampus from control (N = 8), vehicle-treated (N = 7) and FK506-treated (N = 9) SE-induced rats were processed for qPCR analysis to detect mRNA expression level of (B) ICER and (D) GABRA1. Values calculated using standard curve method were normalized with control and plotted as mean ± standard deviation (SD). ANOVA p-value = 0.0008. Bonferroni multiple comparisons ***p-value < 0.001. Immunoblot analysis was done using the same animals for (C) ICER and (E) GABRA1. Western blots were run from hippocampal lysates of control, FK506- or DMSO-treated SE rats. The band intensities were determined using Image J software. Representative western blot images are shown below the graphs. The values were normalized for loading control with β-tubulin. Values averaged from duplicate experiments were plotted as mean ± SD. For ICER (C) ANOVA p-value = 0.014. Bonferroni multiple comparisons *p-value < 0.05. For GABRA1 (E) ANOVA p-value = 0.008. Bonferroni multiple comparisons **p-value < 0.01.

4. Discussion

In this study, SE altered the subcellular localization of the CREB cofactor CRTC1 in the hippocampus of pilocarpine-induced rats both during and following SE. The nuclear localization of CRTC1, thought to be an important mechanism for regulating CRE transcription, was found in specific subsets of hippocampal neurons both during (CA1) and following SE (DG neurons). Calcineurin is an activity dependent phosphatase that is known to dephosphorylate CRTC1 at Ser151 and contribute to release of cytoplasmic bound CRTC1 and subsequent nuclear localization. While calcineurin activity was increased during and following SE, no change in the phosphorylation of CRTC1 at Ser151 was detected in SE-induced rats during SE. In contrast, at 48 hours after SE, CRTC1 was highly enriched in the nuclei of DG neurons and dephosphorylation of CRTC1 at Ser151 increased in SE animals. Calcineurin inhibition with FK506 blocked dephosphorylation and nuclear enrichment of CRTC1 48 hours after SE.

CRTC1 via binding to anchor protein 14–3-3 is sequestered in the synapse and cytoplasm of neurons. Upon synaptic activity, CRTC1 translocates to the nucleus of excitatory neurons, which is essential for its ability to function as a transcription cofactor (Ch’ng et al., 2012, Nonaka et al., 2014). We observed intense nuclear staining of CRTC1 in the CA1 region of rat hippocampus during SE. In contrast, at 48 hours after SE, CRTC1 showed increased nuclear localization in DG neurons in SE animals compared to controls. The regional specificity of the nuclear localization of CRTC1 during and following SE is rather surprising considering that nuclear localization of CRTC1 is triggered by synaptic activity and all the three regions CA1, CA3 and DG, in the hippocampus are connected via the trisynaptic network and have increased synaptic input during SE.

Cell type specific nuclear localization following SE may be secondary to differences in the cell specific machinery regulating CRTC1 nuclear localization. Previous reports suggest that activity dependent nuclear translocation of CRTC1 is regulated by its phosphorylation/dephosphorylation. PKC/PKA pathways have been shown to induce or maintain nuclear localization of CRTC1(Mair et al., 2011, Ch’ng et al., 2012) and a study by Tang et al., 2004 found that immunoreactivity of protein kinase C (PKC) isoforms varies in a time dependent manner in the CA1 and DG regions of pilocarpine-induced SE rats (Tang et al., 2004). It will require more study to determine if region specific PKC activity might be responsible for CRTC1 nuclear localization during SE.

Calcineurin has been previously described as a regulator of CRTC1 nuclear localization via dephosphorylation of ser151(Mair et al., 2011). Intense staining of calcineurin was found in the apical dendrites of the pyramidal neurons (CA1 and CA3) one hour after onset of pilocarpine induced SE compared to diffuse staining in control rats(Kurz et al., 2003). Calcineurin immunohistochemical staining was not prominent in DG neurons and cortex one hour after SE(Kurz et al., 2003). Thus, it is possible that the molecular mechanisms that translate synaptic activity into CRTC1 nuclear translocation differ amongst hippocampal neurons and with time after SE onset.

CRTC1 contains 146 serine, threonine and tyrosine residues (Ch’ng et al., 2012). When ser151 is dephosphorylated, CRTC1 is released from cytoplasmic 14–3-3 and transits to the nucleus(Altarejos et al., 2008, Ch’ng et al., 2012). Using an antibody that specifically recognizes CRTC1 phosphorylated on Ser151, 48 hours after SE onset there was decreased phosphorylation of CRTC1 (Ser151) in the hippocampus of SE rats. This finding supports dephosphorylation of Ser151 residue as a candidate for the regulation of nuclear localization of CRTC1 in DG neurons after SE.

Calcineurin is a calcium dependent serine/threonine phosphatase, that is highly expressed in rat hippocampus (Polli et al., 1991, Klee et al., 1998). Elevated cAMP and Ca++ levels increase calcineurin phosphatase activity (Sakamoto et al., 2013). Consistent with the previous studies (Kurz et al., 2001, Kurz et al., 2003), we found that the calcineurin activity was increased in the hippocampus of SE rats compared to controls during and following SE. FK506 is a well-characterized inhibitor of calcineurin (Liu et al., 1991) and has been successfully used in multiple rodent brain studies (Butcher et al., 1997, Pardo et al., 2006, Kurz et al., 2008). FK506 was effective in inhibiting the nuclear translocation of CRTC1 in the dentate granular neurons and blocking dephosphorylation at Ser151 in SE-induced rats, 48 hours after SE onset. Suggesting that CRTC1 nuclear localization in DG neurons 48 hours after SE is calcineurin dependent.

Intriguingly, we could not detect any difference in the phosphorylation of CRTC1 Ser151 between the SE and control rat hippocampi during SE. This observation leads to the possibility that dephosphorylation of CRTC1 ser151 during SE is not necessary for its nuclear localization. It is also possible that we were unable to detect a change in phosphorylation of Ser151 during SE in the hippocampus samples because it was masked by unchanged or increased ser151 phosphorylation in other hippocampal sub-regions. Serine residues other than Ser151 including Ser 64, Ser169 and Ser245 have been reported to regulate CRTC1’s transcriptional activity and nuclear localization (Siu et al., 2008, Nonaka et al., 2014, Ch’ng et al., 2015). Different combinations of CRTC1 residues may be phosphorylated and/or dephosphorylated in a time and cell type dependent manner during and following SE. We have not yet been able to measure the phosphorylation state of other CRTC1 serine residues due to lack of available antibodies.

Siu et al., 2008 have shown that in HeLa cells, phosphorylation of C-terminus of CRTC1 causes its translocation into the nucleus via Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase 1 (MEKK1). This phosphorylation-dependent nuclear localization of CRTC1 was independent of calcineurin (Siu et al., 2008). During SE, CRTC1 nuclear localization in CA1 neurons is likely calcineurin -independent and needs further investigation to identify the mechanism.

CREB activity prolongs SE, promotes the development of epilepsy and increases spontaneous seizures(Lopez de Armentia et al., 2007, Zhu et al., 2012, Hansen et al., 2014, Zhu et al., 2015). Various studies have shown a time course and cell type specific modulation of gene expression by CREB in rodent epilepsy models and in tissue resected for treatment of medically refractory epilepsy (Becker et al., 2003, Hansen et al., 2014). CRTC1 is a CREB transcription co-activator that when transported to the nuclei binds CREB and specifies which CREB regulated genes are expressed and is a strong candidate for contributing to CREB dependent gene expression in epilepsy.

48 hours following SE is a post-ictal or latent period where the epileptiform activity is mostly quite in the rats, however, we found CRTC1 activated in the DG region of SE induced rats at this time point. Since calcineurin inhibitor FK506 effects the localization and phosphorylation of CRTC1 at this time point, we speculated to see the effect of FK506 on the transcription of a few CREB regulated genes. However, we could not detect any significant difference in the ICER or GABRA1 mRNA or protein expression levels between vehicle and FK506-treated SE rats. Interestingly, we found modulation in the expression level of these two genes between control and SE rats as also shown by previous studies (Brooks-Kayal et al., 1998, Lund et al., 2008, Zhu et al., 2012). This suggests that either 1) the tested genes are not the target for CRTC1 at this time point, 2) calcineurin inhibitor FK506 could not sufficiently block the nuclear localization and activity of CRTC1 or 3) FK506 has alternate non CRTC1 targets which might influence the regulation of the tested genes. Undoubtedly, we need better ways to manipulate the activity of CRTC1 in order to determine which genes are regulated by CREB/CRTC1 and their role in epilepsy will hopefully identify novel molecular targets for treating SE and epileptogenesis.

CRTC1 concentrates in the nucleus of CA1 pyramidal neurons during SE.

Nuclear localization of CRTC1 increases in the dentate granule neurons 48 hours after SE.

Increased dephosphorylation of CRTC1 at Serine 151, 48 hours following SE

FK506 blocks CRTC1 serine 151 dephosphorylation and nuclear localization 48 hours after SE.

5. Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Elyse Rankin-Gee and KaYam Chak for their technical support and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) for financial support (NSRO1 N5056222).

Abbreviations

- CRTC1

CREB-regulated transcription cofactor 1

- TLE

Temporal lobe epilepsy

- CREB

cAMP response-element binding protein

- SE

Status epilepticus

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulphoxide

- Ser151

Serine151

- DG

Dentate gyrus

- IP

Intraperitoneal

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

6. References

- Altarejos JY, Goebel N, Conkright MD, Inoue H, Xie J, Arias CM, Sawchenko PE, Montminy M (2008) The Creb1 coactivator Crtc1 is required for energy balance and fertility. Nature medicine 14:1112–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont TL, Yao B, Shah A, Kapatos G, Loeb JA (2012) Layer-specific CREB target gene induction in human neocortical epilepsy. J Neurosci 32:14389–14401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker AJ, Chen J, Zien A, Sochivko D, Normann S, Schramm J, Elger CE, Wiestler OD, Blumcke I (2003) Correlated stage- and subfield-associated hippocampal gene expression patterns in experimental and human temporal lobe epilepsy. Eur J Neurosci 18:2792–2802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittinger MA, McWhinnie E, Meltzer J, Iourgenko V, Latario B, Liu X, Chen CH, Song C, Garza D, Labow M (2004) Activation of cAMP response element-mediated gene expression by regulated nuclear transport of TORC proteins. Current biology : CB 14:2156–2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Kayal AR, Shumate MD, Jin H, Rikhter TY, Coulter DA (1998) Selective changes in single cell GABA(A) receptor subunit expression and function in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nature medicine 4:1166–1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher SP, Henshall DC, Teramura Y, Iwasaki K, Sharkey J (1997) Neuroprotective actions of FK506 in experimental stroke: in vivo evidence against an antiexcitotoxic mechanism. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 17:6939–6946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng TH, DeSalvo M, Lin P, Vashisht A, Wohlschlegel JA, Martin KC (2015) Cell biological mechanisms of activity-dependent synapse to nucleus translocation of CRTC1 in neurons. Frontiers in molecular neuroscience 8:48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ch’ng TH, Uzgil B, Lin P, Avliyakulov NK, O’Dell TJ, Martin KC (2012) Activity-dependent transport of the transcriptional coactivator CRTC1 from synapse to nucleus. Cell 150:207–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SR, Hu YM, Chen H, Pan HL (2014) Calcineurin inhibitor induces pain hypersensitivity by potentiating pre- and postsynaptic NMDA receptor activity in spinal cords. J Physiol 592:215–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conkright MD, Canettieri G, Screaton R, Guzman E, Miraglia L, Hogenesch JB, Montminy M (2003) TORCs: transducers of regulated CREB activity. Mol Cell 12:413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curia G, Longo D, Biagini G, Jones RS, Avoli M (2008) The pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci Methods 172:143–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen KF, Sakamoto K, Pelz C, Impey S, Obrietan K (2014) Profiling status epilepticus-induced changes in hippocampal RNA expression using high-throughput RNA sequencing. Scientific reports 4:6930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H, Cohen DE, Cui L, Supinski A, Savas JN, Mazzulli JR, Yates JR 3rd, Bordone L, Guarente L, Krainc D (2012) Sirt1 mediates neuroprotection from mutant huntingtin by activation of the TORC1 and CREB transcriptional pathway. Nature medicine 18:159–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klee CB, Ren H, Wang X (1998) Regulation of the calmodulin-stimulated protein phosphatase, calcineurin. J Biol Chem 273:13367–13370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz JE, Moore BJ, Henderson SC, Campbell JN, Churn SB (2008) A cellular mechanism for dendritic spine loss in the pilocarpine model of status epilepticus. Epilepsia 49:1696–1710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz JE, Rana A, Parsons JT, Churn SB (2003) Status epilepticus-induced changes in the subcellular distribution and activity of calcineurin in rat forebrain. Neurobiol Dis 14:483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurz JE, Sheets D, Parsons JT, Rana A, Delorenzo RJ, Churn SB (2001) A significant increase in both basal and maximal calcineurin activity in the rat pilocarpine model of status epilepticus. J Neurochem 78:304–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Farmer JD Jr., Lane WS, Friedman J, Weissman I, Schreiber SL (1991) Calcineurin is a common target of cyclophilin-cyclosporin A and FKBP-FK506 complexes. Cell 66:807–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez de Armentia M, Jancic D, Olivares R, Alarcon JM, Kandel ER, Barco A (2007) cAMP response element-binding protein-mediated gene expression increases the intrinsic excitability of CA1 pyramidal neurons. J Neurosci 27:13909–13918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund IV, Hu Y, Raol YH, Benham RS, Faris R, Russek SJ, Brooks-Kayal AR (2008) BDNF selectively regulates GABAA receptor transcription by activation of the JAK/STAT pathway. Science signaling 1:ra9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mair W, Morantte I, Rodrigues AP, Manning G, Montminy M, Shaw RJ, Dillin A (2011) Lifespan extension induced by AMPK and calcineurin is mediated by CRTC-1 and CREB. Nature 470:404–408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neasta J, Ben Hamida S, Yowell Q, Carnicella S, Ron D (2010) Role for mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 signaling in neuroadaptations underlying alcohol-related disorders. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107:20093–20098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nonaka M, Kim R, Fukushima H, Sasaki K, Suzuki K, Okamura M, Ishii Y, Kawashima T, Kamijo S, Takemoto-Kimura S, Okuno H, Kida S, Bito H (2014) Region-specific activation of CRTC1-CREB signaling mediates long-term fear memory. Neuron 84:92–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto OK, Janjoppi L, Bonone FM, Pansani AP, da Silva AV, Scorza FA, Cavalheiro EA (2010) Whole transcriptome analysis of the hippocampus: toward a molecular portrait of epileptogenesis. BMC Genomics 11:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo R, Colin E, Regulier E, Aebischer P, Deglon N, Humbert S, Saudou F (2006) Inhibition of calcineurin by FK506 protects against polyglutamine-huntingtin toxicity through an increase of huntingtin phosphorylation at S421. J Neurosci 26:1635–1645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra-Damas A, Valero J, Chen M, Espana J, Martin E, Ferrer I, Rodriguez-Alvarez J, Saura CA (2014) Crtc1 activates a transcriptional program deregulated at early Alzheimer’s diseaserelated stages. J Neurosci 34:5776–5787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkanen A, Kharatishvili I, Karhunen H, Lukasiuk K, Immonen R, Nairismagi J, Grohn O, Nissinen J (2007) Epileptogenesis in experimental models. Epilepsia 48 Suppl 2:13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polli JW, Billingsley ML, Kincaid RL (1991) Expression of the calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase, calcineurin, in rat brain: developmental patterns and the role of nigrostriatal innervation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res 63:105–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ (1972) Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:281–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K, Norona FE, Alzate-Correa D, Scarberry D, Hoyt KR, Obrietan K (2013) Clock and light regulation of the CREB coactivator CRTC1 in the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. J Neurosci 33:9021–9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Takemori H, Yagita Y, Terasaki Y, Uebi T, Horike N, Takagi H, Susumu T, Teraoka H, Kusano K, Hatano O, Oyama N, Sugiyama Y, Sakoda S, Kitagawa K (2011) SIK2 is a key regulator for neuronal survival after ischemia via TORC1-CREB. Neuron 69:106–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu YT, Ching YP, Jin DY (2008) Activation of TORC1 transcriptional coactivator through MEKK1-induced phosphorylation. Mol Biol Cell 19:4750–4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang FR, Lee WL, Gao H, Chen Y, Loh YT, Chia SC (2004) Expression of different isoforms of protein kinase C in the rat hippocampus after pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus with special reference to CA1 area and the dentate gyrus. Hippocampus 14:87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal AK, Sameer Kumar GS, Mahadevan A, Selvan LD, Marimuthu A, Dikshit JB, Tata P, Ramachandra Y, Chaerkady R, Sinha S, Chandramouli B, Arivazhagan A, Satishchandra P, Shankar S, Pandey A (2012) Transcriptomic Profiling of Medial Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. J Proteomics Bioinform 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts AG, Sanchez-Watts G, Liu Y, Aguilera G (2011) The distribution of messenger RNAs encoding the three isoforms of the transducer of regulated cAMP responsive element binding protein activity in the rat forebrain. J Neuroendocrinol 23:754–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (May 2015) Epilepsy fact sheet Available at http://wwwwhoint/mediacentre/factsheets/fs999/en/.

- Zhu X, Dubey D, Bermudez C, Porter BE (2015) Suppressing cAMP response element-binding protein transcription shortens the duration of status epilepticus and decreases the number of spontaneous seizures in the pilocarpine model of epilepsy. Epilepsia. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Han X, Blendy JA, Porter BE (2012) Decreased CREB levels suppress epilepsy. Neurobiol Dis 45:253–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]