Abstract

Guided by a community-based participatory research (CBPR) and systems-based approach, this three-year mixed-methods case study describes the experiences and capacity development of a Community-Academic Advisory Board (CAB) formed to adapt, implement, and evaluate an evidence-based childhood obesity treatment program in a medically underserved region. The CAB included community, public health, and clinical partners (n=9) and academic partners (n=9). CAB members completed capacity evaluations at four points. Partners identified best practices that attributed to the successful execution and continued advancement of project goals. The methodological framework and findings can inform capacity development and sustainability of emergent community-academic collaborations.

Keywords: community-based participatory research, community capacity, mixed-methods, childhood obesity, medically underserved area

Introduction

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is an action-oriented research approach that aims to build equitable community-academic partnerships and encourage community participation in all phases of the research, including research development, implementation, and evaluation processes.1–3 The benefits of CBPR include capacity building and the increased likelihood of sustainable adoption of evidence based practices.1–3 A few key CBPR principles include supporting participatory decision making processes and developing strong interpersonal relationships between practice and research partners. Although understanding these processes and outcomes are critical to promoting the translation of evidence-based programs into practice-based settings, there is limited knowledge of the process and practical experiences of stakeholders involved in research and capacity building activities.4,5

This gap extends to family-based childhood obesity treatment interventions. Although there is a large body of literature and a number of systematic reviews documenting the efficacy of family-based childhood obesity treatment interventions; 6–10 there is little evidence of systematic translation into regular practice in regions experiencing health disparities.11 There are also substantial gaps in the literature related to the features and capacities within clinical and community settings that could improve the translation and sustainability of family-based childhood obesity treatment interventions into typical practice.12,13 While CBPR has demonstrated success for recruiting, retaining and effectively impacting disadvantaged populations,14 including some childhood obesity prevention efforts;15–17 there is relatively less evidence for CBPR projects in the context of family-based childhood obesity treatment programs.18 This is especially problematic given the steady increase in prevalence and severity in childhood obesity across all genders and ages between 1999 and 201619 and the disproportionate distribution of childhood obesity among ethnic and racial minorities as well as rural and economically disadvantaged populations.20

This study builds upon a first year capacity analysis which identified best practices for the initiation phase of a CBPR childhood obesity treatment initiative.21 The overall goal of this three-year mixed-methods community case study is to describe the capacity building processes and experiences of Community-Academic Advisory Board (CAB) partners involved with the adaptation, implementation, and evaluation of an evidence-based childhood obesity treatment program in a medically underserved region. Facilitators and barriers related to partnership and program sustainability are highlighted.

Background of Targeted Community

This case study targets the Dan River Region located in south central Virginia and north central North Carolina. This region is federally designated as medically underserved and burdened with educational, economic, and health inequalities.22 Regional unemployment rates range from 4% to 6%, considerably higher than the current state (3.1%) and national averages (3.9%).23 In the region, 52% are female, 34% black, 15.3% living below the Federal Poverty Level, and only 18.6% have obtained a bachelor’s degree.24 The region has some of the highest rates of obesity and poorest health behaviors in the country.25 Unfortunately, locally available data indicate that the childhood obesity prevalence rate is three times higher than the state average. Additionally, the region faces challenges related to effectively addressing obesity, including limited access to primary care, low availability of weight loss programs and a lack of organized community health coalitions.26 In response to these data, an obesity-focused coalition was initiated in the Dan River Region in 2010 and included many of the academic and community partners involved in this childhood obesity project.27,28

In early 2012, academic members hosted a series of planning meetings with regional community organizations that had missions related to child health services and serving low socioeconomic families. Local health data and research opportunities were discussed and childhood obesity treatment emerged as the top identified regional health priority. The group then engaged in a SWOT analysis to further define strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats for childhood obesity treatment options in the region. This information was then used to write a National Institutes of Health (NIH) 3-year planning grant titled, “Partnering for Obesity Planning and Sustainability (POPS)” which was submitted and funded in June 2012 and January 2013, respectively. Primary aims were to build and assess local capacity and partnerships pertaining to childhood obesity treatment. Secondary aims were to select, adapt, implement and evaluate an evidence-based childhood obesity treatment program.

Background on Partnership: POPS-Community Advisory Board (CAB)

The CAB officially initiated in January of 2013 and was a mix of community partners from Pittsylvania/Danville Health District (PDHD), Children’s Healthcare Center (CHC), Danville Parks & Recreation (DPR), and Boys & Girls Club of the Danville Area (BGCDA) and academic partners from Virginia Tech (VT). Community partners were strategically identified for their missions related to child health and services that target low socioeconomic families. All of these partners had participated in developing and submitting the NIH planning grant, including providing letters of support. As such, both academic and community partners shared a commitment to mutual capacity building to develop and implement a culturally relevant and sustainable childhood obesity treatment program for the region.

While all of the CAB partners were involved in the initial selection and adaptation of the evidence-based childhood obesity treatment program, subcontracted partners served in areas of recruitment, enrollment, and data collections (CHC, PDHD, DPR) as well as program implementation (DPR and PDHD). The VT research partners helped to organize the planning meetings, program implementation and evaluation efforts for primary and secondary aims. Virginia Tech’s Institutional Review Board approved the partnership evaluation plan and CAB members provided written informed consent to participate.

Background and Outcomes of the Childhood Obesity Treatment Program, iChoose

At the inception of the project, VT partners presented three evidence-based programs (i.e., Bright Bodies, 6 Traffic Light Diet,7 and Home Environmental Change Model8) to the CAB. Over the course of three monthly meetings, the CAB followed the National Cancer Institute’s “Using What Works – Guide to Choosing an Evidence Based Program” process 29 to select Bright Bodies for implementation in the region. Bright Bodies was subsequently adapted into iChoose, a 3-month family-based childhood obesity program for the Dan River Region. This multicomponent intervention included biweekly family nutrition and behavioral strategy sessions, telephone support calls, and child newsletters along with exercise sessions twice weekly. iChoose was implemented and evaluated over three cohorts during the planning grant. Process and outcome analyses revealed several key findings. First, the CAB demonstrated their ability to engage low income and minority families (n=101 families across 3 waves over ~12 months). Second, community and clinical partners successfully implemented the multicomponent iChoose program with high fidelity. Third, the 3-month iChoose program resulted in a modest and significant improvement in weight status among children and parents between baseline and 3-month data collections that was not sustained at 6-months thereby suggesting a need for maintenance programming.30 Given these mainly encouraging findings, the remaining focus of this mixed-methods case study is to describe how the community capacity of the CAB was built and assessed, and explore how capacity procedures influenced evolution and sustainability of this intervention.

Methods

CAB Procedures

The CBPR conceptual logic model, community capacity and group dynamics literature guided the CAB capacity building framework and evaluation.2,3,31 In the first year, community and academic partners of the CAB met monthly for approximately 5–6 hours. Meetings were facilitated by an external consultant. A recording secretary compiled meeting minutes as well as any materials reviewed by the CAB. In the second and third years, larger CAB meetings occurred on a more quarterly basis with conference calls occurring on a monthly basis in between these meetings. Also, regular trainings were conducted with community partners who were leading the iChoose program implementation and participating in data collection activities.

Capacity Measures: Defining Community Capacity for the CAB

During the initial months, CAB members developed a Community Capacity Evaluation Plan. Academic partners gathered literature to present to community partners regarding various constructs and dimensions identified as critical to building capacity. Based on discussions, the CAB identified and refined 13 capacity dimensions (see Table 1—insert here). Feedback from these discussions indicated that trust, communication, collective efficacy, group roles and member participation and influence were foundational elements for future success. During analyses, these 13 constructs were organized within three conceptual groups that are reflective of CBPR procedures and outcomes: 1) capacity efforts (e.g., how the group operates using CBPR principles), 2) capacity outcomes (e.g., how the group develops because of efforts), and 3) sustainability outcomes (e.g., outcomes that contribute to longevity of the CAB and its efforts).

Table 1.

Community Advisory Board (CAB) identified and prioritized capacity constructs specific to the project goals

| Capacity Efforts | |

| Decision making | Process by which decisions are made and how those decisions keep the project moving forward |

| Conflict Resolution | Process by which disagreements or conflicts are resolved to keep the project moving forward |

| Communication | Channels of communication are identified and utilized to share information openly and regularly |

| Problem Assessment | The ability of the advisory board to identify, prioritize, find solutions, and act on a problem |

| Group Roles | Defining clear responsibilities and expectations for group members within the advisory board |

| Resources | Effective use of individual, organization, and community assets to move the goals of the project forward |

| Capacity Outcomes | |

| Trust | Degree to which advisory board members rely on each other to share information, complete tasks, and remain committed to the project |

| Leadership | Demonstrated ability and willingness to guide and direct efforts of the advisory board |

| Participation and Influence | Degree to which every advisory board member feels equally valued, heard, and empowered regarding the direction of the project |

| Collective Efficacy | Level of group confidence in developing, implementing and sustaining an effective childhood obesity intervention |

| Sustainabilty Outcomes | |

| Sustainability | Commitment to project continuation via active planning, including efforts to improve feasiblility and seek additional resources |

| Accomplishments | Demonstrated success toward project goals that includes both process and project outcome achievements |

| Community Power | Garnering legitimacy in the community by dissemination of impacts and leveraging that legitimacy to further the goals of the project |

Note: Capacity constructs adapted from Sandoval J, Lucero J, Oetzel J, et al. Process and outcome constructs for evaluating community-based participatory research projects: a matrix of existing measures. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(4):680–690.

Guided by the identified capacity dimensions, partners worked together to develop a mixed methods approach to measure progress in capacity development within the CAB. Adapted from existing scales, 31 the quantitative measure was a 63-item survey consisting of the 13 capacity constructs described above. Reliability analysis of the subscales indicate Cronbach Alpha’s greater than .65 for all scales, except Community Power and Accomplishments which were not used in the quantitative analysis. The qualitative assessment was a 21-item semi-structured interview also based upon the 13 capacity constructs.

CAB Capacity Evaluation Procedures and Sample

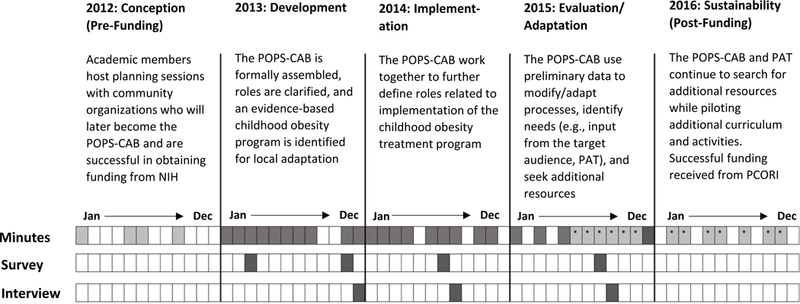

Capacity growth was systematically assessed across the phases of the project via quantitative and qualitative methods (see Figure 1—insert here). The CAB’s independent facilitator conducted the qualitative phone interviews and initial thematic data synthesis, and presented annual progress reports to the CAB. The sample size varied somewhat across each time period (see figures and tables) but averaged 9 community members (range 8–11) and 9 academic members (range 7–10). Phone interviews averaged 52 minutes (range 30–72 minutes) and were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Figure 1. Study design and data sources.

Notes: Dark shaded months indicate POPS-CAB minutes, surveys, and interviews conducted with the purposes of analyzing for capacity building activities and progress during the three year NIH-R24 funding period (2013–2015)

Light shaded months indicate meeting minutes prior to the formal creation of the POPS-CAB that were analyzed for context

Light shaded months with asterisks indicate PAT meeting minutes in which a select number of CAB members participated. These minutes were analyzed for themes and progress around project sustainability.

Analysis

Progress towards the CAB’s project goals were determined via review of meeting minutes for project processes and outputs and the analysis of the Capacity Evaluation Plan (survey and interview). The quantitative data were entered into SPSS (version 22). ANOVAs were used to explore changes over time and independent t-tests were used to explore pattern differences between academic and community partners. The qualitative data were entered into NVivo (version 10 QSR International, Burlington, MA) and coded for 13 capacity constructs of the Capacity Evaluation Plan. After reviewing the qualitative data transcripts, two research members met with the independent facilitator to identify initial emergent themes for each dimension, operationalized as facilitators or barriers, and develop theme definitions. Subsequently, four research team members worked in randomly assigned pairs to code meaning units from each transcript using a hybrid inductive-deductive qualitative analysis approach.32,33 The generation of emergent themes from the meaning units illustrates an inductive approach, while the a priori coding of the data to community capacity and group dynamics dimensions illustrates a deductive approach. Meaning units were defined as the constellation of words or statements that relate to the same central meaning and can also be referred to as a content unit or coding unit, a keyword and phrase, and a unit of analysis.33 The coding and development of emergent themes was an iterative process, and the team met regularly to troubleshoot coding issues and refine themes. As a final step, the emergent facilitator and barrier themes were examined and coded once again for their relation to sustainability. Researchers used data queries to cross-tabulate the number of members reporting themes under facilitators and barriers with the sustainability codings. These tallies were further organized by project phase, capacity groupings, and the individual capacity dimensions. In the discussion, data are triangulated across all sources and interpreted in relationship to sustainability outcomes.

Results

Timeline, Capacity and Sustainability Activities, and Outcomes

As seen in Table 2—insert here, capacity efforts and outcomes demonstrate partners’ ability to successfully work together to achieve the aims of each phase of the project. These deliberate efforts build upon one another such that success within capacity efforts influenced positive capacity outcomes, which in turn built momentum for sustainability outcomes. For instance, in the development phase, sharing information about CAB partners helped to identify expertise and define group roles that in turn built confidence in collective abilities, and initiated sustainability action through the establishment of a common vision for the project.

Table 2.

Timeline of capacity efforts and outcomes made by the Community Advisory Board (CAB)

| CAPACITY EFFORTS | CAPACITY AND SUSTAINABILTY OUTCOMES | |

|---|---|---|

| Conception | • Conducted planning meetings with select partners • SWOT analysis used to further understand childhood obesity treatment needs in the region • Developed research aims for an NIH Planning Grant • Partners provided input on budget and scope of work necessary for proposed project |

•Successful submission of NIH Planning grant • Awarded funding for a 3 year NIH planning grant “Partnering for Obesity Planning and Sustainability (POPS)” |

| Development | •Met face to face regularly on a monthly basis • Neutral facilitator to lead meetings/team building activities • Established decision and shared agenda making procedures • Members identified individual/organizational resources • Identification of key capacity constructs and development of a capacity evaluation plan to monitor progress of the CAB • Collaborative review of evidence-based childhood obesity treatment programs • Group roles defined (e.g., development, recruitment, implementation, dissemination) • Creation of subcommittees for curriculum development, recruitment, and implementation |

•Established a common vision that connects with the mission of each partner organization • Identified a childhood obesity program for adaptation • Expertise on target population used to adapt the program • Implemented the capacity evaluation plan • Planned and executed recruitment procedures for cohort 1 • Planned an implementation strategy for cohort 1 |

| Implementation | • Established regular communication channels to problem solve issues with implementation • Community partners trained in program implementation • Adapted program materials to address health literacy using feedback from participants and CAB members • Trained community partners for leadership role in cohort 2 • Recruited and enrolled participants into cohort 1 • Collected and analyzed cohort 1 data • Rresults from cohort 1 informed adaptations for cohort 2 • Recruited and enrolled eligible participants into cohort 2 |

• Adapted program materials using universal health literacy precautions • Identified key aspects of the sustainably action plan • Presented a poster of capacity findings at the Minority Health and Health Disparities Grantee’s Conference • Implemented Cohorts 1 and 2 with high levels of fidelity • Analysis of cohort 1 data indicated preliminary success with primary outcomes • Initial capacity evaluation findings indicated positive capacity building efforts |

| Evaluation/Adaptation | • Review Cohort 1 and 2 data analyses • Identify and brainstorm on problems identified through the data (e.g., recruitment, retention, adherence) • Developed and disseminated a marketing video on iChoose • Recruited and enrolled participants into cohort 3 • Piloted open referral processes, including eligibility screening • Collected and analyzed cohort 2 and 3 data • CAB members are involved in discussing research questions to guide grant proposals • Collaborative grant writing efforts • CAB members solicit additional future members to include in future efforts • Celebrated successes with community stakeholders |

• Community partners implemented Cohort 3 with high fidelity • Obtained supplemental NIH funding to create a PAT made up of former iChoose participants to inform curriculum enhancements and strategize on recruitment and engagment • Vision of the PAT becomes central to proposal aims • Submitted proposal for NIH R01 grant [unsuccessful] • Submitted proposal for NIH U01 grant [unsuccessful] • Received letters of support from Danville City Public Schools and Piedmont Access to Health Services as potential future CAB members • Three conference research posters presented (health literacy, process evaluation, and call engagement) • CAB members present iChoose at local Health Summit |

| Sustainability | • CAB members continue to contribute to grant writing efforts • PAT continues to meet on a regular basis to pilot future curriculum ideas |

• Funding gap addressed through overhead funds and in-kind contributions from partners • Submitted third proposal for NIH R01 grant funding [not successful] • Submitted fourth proposal to PCORI funding [successful—project start date is set as June 1st, 2017] • Lessons Plans for expanded iChoose curriculum created • Submission of manuscripts on capacity and health literacy • Conference research poster presentation on engagement and satisfaction |

Notes: Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT); Children’s Healthcare Center (CHC); Pittsylvania Danville Health District (PDHD); Virginia Tech (VT); Parent Advisory Team (PAT); Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI)

In the implementation phase of the project, these foundational efforts were put into action as partners worked collaboratively to successfully recruit and enroll families, implement three cohorts of iChoose, and problem solve challenges to program feasibility. This included community partner input into the material compliance with universal health precautions, inclusion of parents in the physical activity classes, expansion of recruitment efforts into schools and an additional health district, and the inclusion of a field trip to the local farmer’s market within the iChoose curriculum.

Late in the implementation phase and through the sustainability phase, partners were able to reflect upon evaluation results to determine their success. During this time, community partners collaborated with their academic counterparts in manuscript development by providing input on background, specifics on procedures, and interpretations of results. These collaborative endeavors to translate study findings and reflect on capacity efforts of the CAB helped to inform decisions regarding future sustainability of the partnership and the resulting iChoose program.

Upon interpreting the iChoose outcome data,24 the CAB concluded that the program was promising in its ability to reach families and improve BMI status, but not at maintaining BMI improvements. Furthermore, reach data and process evaluation suggested continued challenges in recruitment and engagement. The CAB concluded the need for additional research into the viability of iChoose as an effective and sustainable childhood obesity treatment option for the region. The CAB also concluded that if they are to address some of these important issues, their stakeholder group needed to include input from the targeted population. Thus, in 2015 the academic partners successfully submitted and obtained a supplemental grant to create a Parent Advisory Team (PAT). The CAB recruited the PAT from a pool of previous iChoose participants with the purpose of engaging them to improve reach, retention, and adherence as well as develop additional skill building curriculum activities for iChoose. The PAT’s efforts and feedback over the last phase of the project proved central to the collaborative grant writing process between the CAB and PAT. Over the next two years, PAT and CAB members contributed input on research, reviewed research plans, and provided letters of support for four grant proposals. Thus, in conjunction with capacity building activities, activities related to sustainability matured from a common vision and commitment in the development phase of the project to concrete sustainability action in later phases.

Quantitative Changes in Perceptions of Capacity and Sustainability Constructs Over Time and Differences between Community and Academic Partners

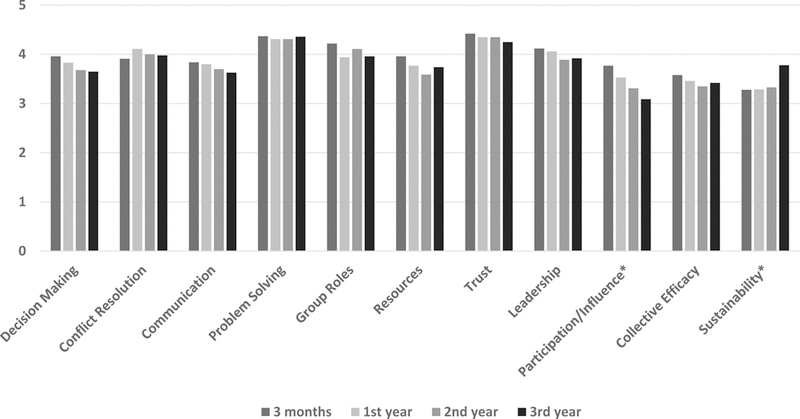

CAB member ratings of capacity constructs were relatively high at three months (above the midpoint of the scale) and remained high across time (Figure 2—insert here). Analyses of capacity constructs across the four time points indicated significant differences for Participation and Influence and Sustainability, but not for the other constructs. Post-hoc comparisons revealed improvement in perceptions of Sustainability from 2013 to 2015, which are reflective of maturation of project activities related to sustainability growth. However, Participation and Influence significantly declined during the same period. When exploring pattern differences between partners, community partners rated Participation and Influence higher than academic partners in the development phase (Table 3—insert here). Alternatively, community partners rated Group Roles lower than academic partners in the developmental and implementation phases. In the later sustainability phase, perceptions of Problem Assessment were rated higher among academic partners. When triangulated with the qualitative data detailed furthered below, these quantitative findings are contextualized within the project timeline and goals.

Figure 2.

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) results in examining changes in perceptions of capacity constructs among Community Advisory Board (CAB) members over the three years of the project

*p<0.05

Table 3.

Independent t-test analysis to examine trends in perceptions of capacity constructs between community partners (CP) and academic partners (AP) within the Community Advisory Board (CAB) over the three years of the project

| Dimension | # of items |

Cronbach alpha (baseline) |

March 2013 Development Mean (sd) n=15 |

November 2013 Development Mean (sd) n=19 |

July 2014 Implementation Mean (sd) n=19 |

August 2015 Evaluation/Adaptation Mean (sd) n=20 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP (n=8) | AP (n=7) | CP (n=9) | AP (n=10) | CP (n=11) | AP (n=8) | CP (n=11) | AP (n=9) | |||

| Decision-Making Procedures | 9 | .787 | 4.01 (0.42) | 3.89 (0.31) | 3.85 (0.34) | 3.81 (0.48) | 3.58 (0.45) | 3.82 (0.45) | 3.65 (0.54) | 3.65 (0.39) |

| Conflict Resolution | 3 | .889 | 4.13 (0.35) | 3.67 (0.72) | 4.00 (0.53) | 4.20 (0.50) | 3.85 (0.58) | 4.21 (0.50) | 4.09 (0.34) | 3.85 (0.47) |

| Communication | 5 | .768 | 4.90 (0.14) | 4.66 (0.43) | 4.90 (0.20) | 4.60 (0.54) | 4.51 (0.62) | 4.73 (0.38) | 4.44 (0.82) | 4.58 (0.60) |

| Problem Assessment | 4 | .811 | 4.38 (0.33) | 4.36 (0.61) | 4.19 (0.40) | 4.40 (0.44) | 4.15 (0.56) | 4.50 (0.35) | 4.10 (0.63) | 4.64 (0.49) |

| Group Roles | 4 | .711 | 4.06 (0.37) | 4.39 (0.52) | 3.66 (0.50) | 4.18 (0.57) | 3.82 (0.70) | 4.50 (0.52) | 3.86 (0.83) | 4.08 (0.60) |

| Resources | 7 | .769 | 3.91 (0.48) | 4.02 (0.36) | 3.80 (0.47) | 3.76 (0.38) | 3.43 (0.44) | 3.82 (0.77) | 3.65 (0.38) | 3.86 (0.60) |

| Trust | 3 | .746 | 4.50 (0.50) | 4.33 (0.47) | 4.46 (0.43) | 4.27 (0.66) | 4.42 (0.52) | 4.25 (0.58) | 4.33 (0.67) | 4.15 (0.29) |

| Leadership | 5 | .724 | 4.25 (0.37) | 3.97 (0.42) | 4.22 (0.29) | 3.92 (0.55) | 3.93 (0.43) | 3.85 (0.53) | 4.07 (0.55) | 3.73 (0.52) |

| Participation & Influence | 7 | .751 | 4.00 (0.61) | 3.51 (0.41) | 3.76 (0.36) | 3.33 (0.52) | 3.29 (0.49) | 3.34 (0.51) | 3.17 (0.46) | 2.98 (0.38) |

| Collective Efficacy | 3 | .794 | 3.63 (0.49) | 3.52 (0.88) | 3.29 (0.49) | 3.60 (0.64) | 3.21 (0.79) | 3.54 (0.47) | 3.21 (0.90) | 3.67 (0.91) |

| Sustainability | 4 | .656 | 3.25 (0.38) | 3.32 (0.53) | 3.31 (0.37) | 3.28 (0.34) | 3.23 (0.56) | 3.47 (0.57) | 3.66 (0.55) | 3.92 (0.63) |

Note: Bold italicized indicates a trend of p<0.10; bold indictes a significant difference of p < 0.05

Qualitative Facilitators and Barriers to Capacity as they Relate to Sustainability

Analysis of the capacity interviews across the lifespan of the study revealed emerging patterns. There were both consistencies and fluctuations within facilitators and barriers across capacity efforts and capacity outcomes as they relate to sustainability outcomes (Table 4—insert here).

Table 4.

Qualitative facilitators and barriers to capacity building of the Community Advisory Board (CAB) as they pertain to project sustainability across time

| Facilitators to Sustainability | Barriers to Sustainability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DEVELOPMENT 2013 | Capacity Efforts |

Recognize/Leverage Expertise (Comm=9, Acad=8) I am biased, but I feel like the team is well constructed. So from an academic perspective, the PI’s have enough experience with that type of program validity building. But, they also found the community partners that cover quite a good range of the locality there. So, the local infrastructures are fully supportive. Academic Opportunities for participation (Comm=8, Acad=8) … being in this environment makes one realize their own potential. So that…next year…POPS CAB [community members]…would be willing to take a more active leadership role. Community |

Limited continuity of communication between meetings (Comm=2, Acad=7) I do often times…find myself worrying about the communication that happens in between the meetings; and if we’re being as effective as we could with …keeping everyone in the loop… Academic Limited time (Comm=7, Acad=2) I think probably the challenge for myself or people that work outside of the academia is… we have our regular jobs and we have responsibilities there and it’s not always easy to find time. Community |

| Capacity Outcomes |

Trust promotes open communication, including dissent (Comm=7, Acad=7) So if someone agrees then they have no problem speaking up; as well as if there’s something that they seem to be uncomfortable with, it seems that they’ll go ahead and voice their opinion. Academic Confidence in project success (Comm=9, Acad=9) I think we all feel like that it’s a project that will make an impact. And then once it makes an impact, there will be…ways to put in processes to sustain it. Community |

Uncertain implementation abilities (Comm=9, Acad=8) I think for people who haven’t delivered a childhood obesity intervention before, that they’re not as confident … that all of it will come together… Academic |

|

| Sustain-ability Outcomes |

Commitment to a shared vision (Comm=7, Acad=7) I think we all collectively have a passion for reducing obesity and helping… people to seek a healthier lifestyle. Community |

||

| IMPLEMENTATION 2014 | Capacity Efforts |

Recognize/Leverage Expertise (Comm=6, Acad=6) And so when I say that we’re…the content experts, I believe that we have that expertise, but … that we also have partners that have expertise on how best to attract families to these types of programs…so that they stick with [it]. So they have that knowledge of the…target population that I think is critical for us to …develop something…effective and sustainable. Academic Adaptive/flexible as problems arise (Comm=8, Acad=7) But as we went along, we found out that [research protocols] may be…too restricted….We have to be ready for whatever happens..but…this was foreign territory for all of us except for the Virginia Tech folks. So we depended on their knowledge until we …got comfortable with it, and then realized well maybe we need to do this. And they were very willing to change and to roll with it. And I think at the very end, we had a pretty good, pretty well-oiled machine. Community |

Limited continuity of communication between meetings (Comm=3, Acad=5) When everyone is not at the meetings…they might miss out on something that was said that might not be in the minutes. Community Uncertainty in continued funding (Comm=9, Acad=5) … it’s going to be very difficult to sustain. So we have to look at ways to…adapt it…to make it more sustainable and [affordable]. Community Difficulties in recruitment (Comm=10, Acad=6) …in my opinion… sending out a letter to X number of people and making a follow up phone call probably wasn’t going to get the numbers [VT was] expecting… I think that’s one of the main challenges. I think the group needs to look at different ways of doing that. Community |

| Capacity Outcomes |

Trust promotes open communication, including dissent (Comm=10, Acad=7) I feel like…the relationship has developed [so] that the community partners…feel more comfortable to say…this isn’t going to work or we need to do it this way…. Academic |

Churn in membership impedes open communication

(Comm=6, Acad=6) …I didn’t come in from the beginning so I don’t quite know what we have done…so far. And it is a little challenging just because I want to speak up, but I don’t know what to speak up about… if I came on at the very beginning, I would be more comfortable… Community |

|

| Sustain-ability Outcomes |

Evaluation/dissemination valued (Comm=5, Acad=5) I feel like after I get the next…maybe at the end of wave three we will have the results that we need to prove that this program works. And I believe, with that being said, other programs would start to implement it. Community Commitment to sustainability (Comm=8, Acad=7) … for us to just be on the first iteration, and we’re already thinking about sustainability, gives me the feeling that everyone understands the importance of what we’re doing and wants to see it continue, and is willing to work to try and help it continue… Community |

Timing in dissemination (Comm=3, Acad=2) I know it’s been said that we’re not yet ready to make this public. I guess my question would be—when will that be? I think if you want somebody to invest in it, they need to know that you’re working on it right now. Community Lack of stakeholder awareness (Comm=9, Acad=4) I think we’ve done very little in terms of talking to anyone who really matters in the region about what we’re doing. I mean, I think people might have an idea, but I mean I also don’t think we’ve really pursued that. Academic Uncertain commitment to delivery (Comm=6, Acad=7) I think the challenges are knowing up front what the commitment levels…[are]needed from each partner or agency…[to avoid] misunderstandings about the work… [they] could contribute [to] sustainability. Community |

|

| EVALUATION/ADAPTATION 2015 | Capacity Efforts |

Recognize/Leverage Expertise (Comm=6, Acad=5) I feel like we have the potential and we have the expertise both in the community and academic side…[to address the] problems that come specifically to the region. Academic Grant writing/marketing efforts (Comm=5, Acad=7) Well I think just Virginia Tech being very clear on applying for different funding and that type of stuff that it’s obvious they have an eye on sustainability. Community |

Limited continuity of communication between meetings (Comm=1, Acad=8) I feel more disconnected…the conference calls—I had not really participated. [But] I would make a schedule change to participate in a face to face meeting. Community Limited time (Comm=6, Acad=8) iChoose is a major part of what I do, but it’s not the only thing… Time to fit a 4 [to] 6 hour meeting—it’s kind of touchy, even it it’s planned well in advance. Community Uncertainty in continued funding (Comm=7, Acad=9) I mean this is a pretty costly program to run. And doing everything, I know we’re doing…potentially asking for people to do the roles and responsibilities now as an in-kind service, I just don’t think will work. Academic Difficulties in recruitment (Comm=3, Acad=0) We got all kinds of…excuses…[for] things that just stood in the way of…coming to the program. Some were simply not interested. Some didn’t think their children were overweight. Community Feasibility of evidence based practices (Comm=2, Acad=3) …we’re trying to ensure that as we move forward we’re sticking with the evidence base while also having local adaptation…but [the adaptations] might be completely disentangled from…our theoretical…base. …how do we integrate adaptations [that] still makes sense? Academic |

| Capacity Outcomes |

Trust promotes open communication, including dissent (Comm=7, Acad=7) …everyone feels comfortable just throwing out ideas… And because we’re so diverse, I feel like we bring a little extra [to the] table…coming up with ideas that other people have not thought of. Community Established trust in cooperative efforts/processes (Comm=6, Acad=8) I felt… we all know our responsibilities… we have a very good trust system. We don’t have to constantly [say] are you doing this or…that? Community Development of a PAT (Comm=1, Acad=3) … now that … families [finished]…iChoose… it’s time to engage [them] so that they can provide …insight… [to] help make the program better. Academic |

Inequities in contributions (Comm=3, Acad=8) And I think from the researchers’ standpoint, if we didn’t initiate, I don’t think the community would be initiating the conversation. Academic Uncertain community leadership (Comm=2, Acad=5) I think we assume that shared leadership or community leadership is the ultimate goal, but maybe they have no interest in doing that; you know, that’s not their comfort level or even where they have an interest. Academic |

|

| Sustain-ability Outcomes |

Recognition of successful collaboration toward a common goal (Comm=6, Acad=9) I think just working for a common goal [together]; knowing that you’ve [the CAB] put together a program that’s attractive and appealing…. I think that to see the things that you envisioned come to being—I think that’s always encouraging. Community |

Need for strategic sustainability planning to support a post-funding transition (Comm=5, Acad=5) …when we get funded for the future, it’s just looking at that sustainability piece [earlier]…so that when the next round of funding ends…we’ve already developed some type of method to keep it going. Community |

|

Note: Comm=Community Partners and Acad=Academic Partners

Development

The primary sustainability outcomes of the development phase of the CAB were to develop a shared vision, identify and adapt an evidence based program, and determine recruitment and implementation strategies. It is clear that recognizing and leveraging expertise was crucial to these sustainability outcomes in that they boosted CAB member confidence in their collective ability to achieve project goals. To initiate this collective efficacy, initial meetings spent considerable time sharing details about the project budget as well as having each of the member organizations present on their mission and potential assets (see Table 2). Confidence and trust were necessary for commitment to a shared vision. These foundational elements expanded with evidence of successful progress towards goals, thereby leading to member commitment to sustainability.

Implementation

The primary sustainability outcomes of the implementation phase of the project were to implement the first cohorts with high levels of fidelity and preliminary success with achieving primary outcomes. As with the development phase, leveraging expertise facilitated sustainability outcomes at the implementation phase. While at the development phase expertise established collective efficacy, at the implementation phase it was applied to recruitment and program facilitation. As preliminary data analyses revealed problems, listening to others and being adaptive to community needs became crucial to continued success. For instance, identified recruitment issues resulted in an additional advertising campaign in the local newspapers, flyers sent out to all of the public schools in the area, and a promotional video using former iChoose participants. The CAB’s ability to use data to help measure project progress, identify problems, and adapt procedures helped to propel the CAB from commitment to a shared vision to a commitment to sustainability.

Evaluation/Adaptation

The primary sustainability outcomes of the evaluation/adaptation phase of the project were to finalize outcome analyses of and begin implementation of a post-funding sustainability plan. Perhaps a key contributor to the successful sustainability of the project was the expansion of leadership to include the PAT. By including parents who experienced the intervention, expertise expanded to better identify community needs and the challenges of families seeking childhood obesity treatment interventions. This addition was used to provide insight and potential solutions for recruitment and retention issues as well as to help market the program to key stakeholder, including potential funders.

In addition to the establishment of the PAT, CAB members were also experiencing a high level of confidence in their collective abilities based upon their experience in working together to implement three cohorts of participants. However, this confidence was tempered by recognized inequities in contributions and influence among CAB members. In particular, academic partners were doubtful on whether community partners would take more of a lead in developing future research questions and committing additional resources to implementation. At the same time, community partners indicated that their input was not always heard. This frustration might stem from misunderstandings about research methodology and policies related to research procedures. Implementation within the context of a research study requires rigor and strict adherence to procedures. It appears that academic partners did not always adequately explain how suggested changes could compromise the integrity or of the research or the intervention, weaken the analysis, or violate institutional policies. In this failure to communicate these limitations, community partners attributed the rejection of ideas to an imbalance in power:

• …you see them [Virginia Tech members] as the powerhouse of the group. And I feel like sometimes when…everyone is openly discussing a topic and we’re all on board and then Virginia Tech…[says] well we’ve always done this and we like this…It’s kind of like, oh, everyone else is on board with it; but yet they’re not. And if they’re not, then we’re not going to do it.

-Community Member

While conflict or concern over power imbalances did not emerge until the final year of the study, evidence of potential problems existed early in the CAB development. Both community and academic partners readily admitted to academic partner dominance, but did not identify this imbalance as a current or future barrier to CAB efforts. In fact, a good number of CAB members identified the dominance of academic partners as necessary for project momentum:

• I feel like [Virginia] Tech does dominate the meetings; but that’s not a bad thing because they’re the ones that are getting this thing going and teaching the people in the community what it’s all about and what needs to be done.

–Community Member

• …but we [academic partners] really do drive the agenda… So…it’s hard not to think that the [academic] team has more influence…. I don’t think that it’s necessarily a negative thing because I think that we also don’t want to overwhelm our community partners and take a whole bunch of their time for the things what we feel like they’ve contributed to and we’re doing more refinement [on].

–Academic Member

This dominance early in CAB development may be inevitable, but later conflict suggests a missed opportunity to discuss these inequities and build a vision for more equitable leadership.

Facilitators and Challenges to Communication

Throughout the developmental phases of the project, open communication and respect were foundational to achieving sustainability outcomes. This established a safe environment for brainstorming procedures, finding solutions to problems, and discussing disagreements. Having a neutral facilitator, time devoted to team building activities at all meetings, and shared agenda development helped establish and maintain this environment. However, while CAB members describe communication in very positive terms, its effectiveness suffered from time limitations, work norms, scheduling conflicts, and difficulties in identifying alternate channels during the intervals between scheduled meetings. Additional challenges to CAB communication included churn in membership and disagreements about when and how to increase stakeholder awareness, including the targeted population, of CAB efforts.

The Role of Uncertainty

Throughout the lifespan of the project, CAB members worried. They worried about their abilities, about limited funds, and partner commitment. Though these worries and uncertainties were expressed as challenges or obstacles, they did not appear to slow project progress. Ultimately, the growing confidence in efforts outweighed doubts. Members maintained their commitment to the project which resulted in a successful grant proposal. Reflections at the evaluation/adaptation phase of the project revealed that the CAB attributed successful collaboration to the expertise, openness, and commitment of the partners.

Discussion

Our mixed methods approach to understanding CAB capacity resulted in a number of lessons learned from project successes and challenges. These findings provide insight for best practices to establish and sustain collaborative partnerships that integrated resources across local healthcare, public health, community, and research systems. Recommendations include: (1) build and nurture strategic partnerships (2) establish trust with procedures that promote relationships and open communication, (3) openly discuss challenges in communication and participation, (4) recognize, discuss, and problem solve imbalances in participation and influence, (5) develop feedback loops to report progress toward goals and inform decision-making, (6) start sustainability planning early and discuss and refine it often, and (7) understand diversity in perceptions as a strength.

Build and nurture strategic partnerships

From the conception of the study, partnerships were developed and maintained strategically to optimize both time and effectiveness of efforts. A history of working together can be an asset to collaborative success and sustainability.34 Overall, the quantitative data indicated that CAB members generally perceived the capacity constructs as strong at baseline. Contextually speaking, these high ratings, even at “baseline” are not particularly surprising given that many of these partners worked together previously on a broader regional coalition.27,28 Furthermore, they had worked specifically to identify the issue of childhood obesity and submit a successfully funded proposal to NIH almost a year ahead of the starting of the project (see Figure 2). This contextual advantage may have shortened lead-time for relationship building and trust development and accelerated problem solving, decision-making, and role defining. Cross-examination of perceptions with CAB accomplishments outlined in Table 2, provide additional evidence for this supposition. In the first year of the project alone, the CAB was able to identify and adapt an evidence-based childhood obesity treatment program, develop and execute recruitment procedures, and plan implementation strategies. In years two and three, they demonstrated successful recruitment and implementation, worked on continued feasibility adaptations, made dissemination plans and searched for future funding for continued sustainability. It is a considerable asset that these strong perceptions at “baseline” were maintained even in the face of difficult tasks that are demanding of a partnership.

While building collaborative work experiences prior to implementation of a study is helpful to project initiation, collective expertise is most beneficial when identified, recognized and leveraged across all phases. Overall, CAB members acknowledged that their success in this area was instrumental to accomplishing project goals across the project lifespan. Having the right people at the table is a considerable asset to project success and sustainability.34 Consistent with project activities summarized in Table 2, the collective expertise of the CAB provided insight into the targeted population that guided adaptations to a childhood obesity treatment program, informed roles and responsibilities, and contributed to problem solving around health literacy, recruitment, and retention. These accomplishments may be attributed to the strategic selection of partners for their strengths in research strategy (VT), targeted population health behaviors (CHC, PDHD), and program implementation feasibility (DPR and PDHD).

Establish trust with procedures that promote relationships and open communication

Trust is a foundational construct to building capacity. It takes time and experience, but there are established CBPR strategies to help nurture safe environment that encourages open discussion and debate.1 Strategies applied by this CAB included well-constructed ice breakers (e.g., content relevant or “get to know you” statements) at each of the face to face meetings and CAB conference calls, the use of an independent facilitator, established time to share information about partnering organizations, and the creation of agreed upon decision-making and conflict resolution procedures (see Table 2). CAB identified contributors of trust to project sustainability included partner follow-through on tasks and commitments, achievement of project goals, and implementation of trust building activities that created a safe meeting environment to express opinions openly (Table 4). The importance of trust in the qualitative data is consistent with the quantitative data in which Trust is the second highest rated construct of the capacity framework.

Openly discuss challenges in communication and participation

While quantitative rankings of communication are similar to other constructs, qualitative data suggests communication may suffer from unavoidable inefficiencies, namely lack of time and scheduling conflicts. This is a struggle with any collaborative process, and as such, is an obstacle for future sustainability. Members reflected this uncertainty with concerns regarding funding, feasibility, and the commitment of community partners to implement, lead, and sustain the project. As seen in Table 2, alternate communication channels were identified and implemented early in the project; however, the qualitative data indicates that they were not always successful at soliciting productive discussion and problem solving. As a result, imbalances in influence (either real or perceived) may have developed between those partners who could attend face-to-face meetings and those who had sporadic attendance. This is consistent with the significant decline in the quantitative data for Participation and Influence. Much of these time challenges are outside of the CAB’s control; however, it may suggest that simply establishing alternate channels of communication is not enough. Acceptability and feasibility of channel use should be established along with the identification of training needs.

Recognize, discuss, and problem solve imbalances in participation and influence

Quantitative declines in Participation and Influence were recognized early in the project; however, these declines were not vocalized as a problem for sustainability until the third year. Some of this lack of recognition may be attributed to the challenges of time, design of the CAB, hierarchy within partner organizations, and expertise within each phase of the project. For example, the partnership was designed using a vertical and horizontal systems-based approach that valued expertise and contribution across organizations, while focusing on the vertical structure within organizations.35 Key to recognizing the vertical system, organizational CAB membership included both an administrative representative with decision-making authority and a practice representative who would ultimately be involved in implementing an aspect of the intervention. This structure works best to inform feasibility of project tasks. While the system worked well early in the funding cycle, time and scheduling conflicts in later developmental phases meant that one or both of these representatives were not always available or engaged.

Related to the vertical and horizontal systems-based approach to the CAB, is the impact of organizational hierarchy on open communication. For instance, the CAB experienced a small influx of practice representatives from community organizations that were actively involved in program implementation (e.g., DPR, PDHD). This influx reflected the implementation phase of the project in which roles for practice representatives were defined and approved by the administrators and the primary project tasks moved towards evaluating the implementation process and outcomes. Feedback during this phase from practice representatives indicated that they were more task oriented, were hesitant to participate in discussions they were not initially a part of, and were more likely to follow the decisions of those they perceived in authority. While this may have reduced input from front-line staff, this did not result in a concern or inefficiencies in implementation. Still, efforts to engage implementation and delivery staff in discussions related to project sustainability is recommended to reduce perceptions of imbalance in participation and influence between academic and community partners. Consistent with the quantitative findings, qualitative analysis indicated that community partners were less likely to acknowledge problems in Participation and Influence (i.e., imbalances in contributions) than were academic partners.

Finally, CBPR literature demonstrates the struggle to move community partners into a comfort zone with a scientific procedure that may not be familiar or make sense within their daily activities.36 While the CAB did develop strategies (see Table 3) to establish greater equity or prevent imbalance (e.g., use of an independent facilitator, shared agenda creation, small group discussions and subcommittees, and inclusion in grant writing activities), the community partners did not develop the confidence necessary to fully share in the leadership of research efforts. As seen from the qualitative data, a complacency developed in which imbalances were recognized, but overlooked because the community partners perceived the research expertise of the academic partners as a high value asset—perhaps higher than their own contributions of expertise. Ultimately, it is of note that regardless of these perceived and real imbalances, community partners were instrumental in all of the project accomplishments outlined in Table 3, including continued sustainability. It is also of note that when imbalances in contributions became a concern in the third year of the project, this concern was primarily expressed by academic partners, rather than community partners. Addressing the normalcy of these imbalances early and brainstorming together on trainings and other ways to become more comfortable, may be key to finding greater equity in these partnerships.36

Develop a feedback loop to report progress toward goals and inform decision-making

The CAB maintained a collective ability to adapt to changing circumstances via continuous communication of preliminary process and outcome evaluation findings. As seen in Table 2, this feedback loop encouraged efficacy in collective efforts, maintained commitment, and allowed for evidence driven modifications. As a result, members reviewed and translated program materials using the universal precautions approach to health literacy, added more physical activity opportunities, and used the PAT to pilot future skill building activities. These qualitative findings are consistent with quantitative perceptions of Problem Assessment. Difference between community and academic members’ ratings of Problem Assessment in the sustainability phase was, in part, related to perceived difficulties in recruitment of iChoose families and feasibility of implementing evidence based practices. Overall, Problem Assessment was the highest rated capacity construct and it proved essential in maintaining program implementation as well as proposing new CBPR projects to sustain the efforts of the CAB.

Start a sustainability plan early and discuss and refine it often

Quantitative data demonstrates a steady and significant increase in perceptions of project sustainability even in the face of complicated CBPR challenges. As seen from the qualitative data, some major obstacles to sustainability included uncertainties in feasibility of implementing evidence-based practices, recruitment and retention issues, and ambiguous commitment to project leadership by community partners. There were also legitimate concerns about sustainability during a potential funding gap. Despite these concerns and a one and a half year funding gap, the project has sustained. This is due, in part, to the capacity framework that strategically guided CAB efforts with a strong sustainability focus. This framework provided a guide in identifying a common vision, encouraging a commitment to sustainability, establishing evidence of success, and expanding leadership opportunities to include the targeted audience. As seen in Table 2, all CAB efforts, starting with the proposal phase, were leading up to the goal of developing a CAB that could sustain continued CBPR inquiry.

Understand diversity in perceptions as a strength

The primary benefit, and challenge, of a CBPR approach is that it brings together a group of individuals from various organizations that have different expertise and approaches to the same identified community issues.1,2 Integrating these diverse insights can result in tension among various participating organizations. For instance, in the sustainability phase, discussions around adaptations to improve feasibility and sustainability of the program spurred debates between community and academic partners regarding fidelity to evidence-based practices (see Table 3). Overall, community partners were more likely to express practical concerns about how to solve recruitment and retention issues, procure resources, and acquire additional strategic partners whereas academic partners were more likely to ponder conceptual issues related to leadership, equity, and effective group functioning. Balancing the perspectives of both community and academic partners was instrumental in project sustainability. It led to expanded recruitment and marketing processes, as well as the addition of strategic partners through the creation of the PAT and the continued research on the feasibility and effectiveness of iChoose.

Study Limitations

Similar to other multisector, collaborative partnerships,3,31 our research is embedded within a unique set of contextual factors and focused on addressing specific program outcomes (i.e. childhood obesity); therefore, identified facilitators and barriers are unique to our circumstances. Despite this limitation, our case study provides generalizable methodology and the lesson learns may be useful to other community-academic teams interested in CBPR processes aimed at developing and sustaining partnerships to translate evidence-based interventions into practice-based settings. The strengths of our conclusions are in the systematic analysis and triangulation of mixed-methods data across sources, time and member type

Conclusion and Implications

The maintenance of strong perceptions of capacity, the successful milestone completions within each phase of the project, and the promising reach and impacts on BMI status for children and parents suggest that out efforts were successful in building the CAB’s capacity to achieve and sustain project goals. Continued funding for the next research phase (i.e., a fully-powered comparative effectiveness study of iChoose) and the commitment of CAB members’ organizations highlight initial sustainability. Collectively, our case study exposes key processes and outcomes related to the development, evaluation, and sustainability of partnerships.

Many of our lessons learned align with other reports of capacity building within the CBPR literature.18,21 However, our contributions are also distinct in three main ways. First, there are few reports of longitudinal mixed-methods data points highlighting the evolution of a CBPR partnership through different research phases37 and none specific to childhood obesity. In conjunction with the recent report on the continued rise of childhood obesity, is the recognition and demand for focused collaborations among multi-sector organizations to reverse the childhood obesity epidemic.19 Our case study highlights key capacity steps and research phases for establishing and sustaining collaborative partnerships committed to childhood obesity treatment. Second, though not without some limitations, we made an a priori and concerted effort to capture potential differences in perceptions among community and academic members across time. This effort enriched the lessons learned and conclusions drawn from our process. Unfortunately, most existing CBPR capacity and partnership development literature do not attempt to compare and contrast perceptions of community and academic partners, thereby failing to acknowledge potential bias.31,38 Third, we present a capacity framework and analytic approach that evaluated sustainability as both an outcome of capacity efforts and a stimulus to continued capacity building. Though unanswered questions pertaining to sustainability persist across the CBPR-focused literature, ours is one of the first known CBPR studies that aimed to triangulate and interpret mixed-method data in relationship to sustainability.

As a final point, it would be misleading to imply that our capacity building processes or sustainability efforts are complete with the next funding award. Though we have maintained the CAB structure with a new funding source, there has been 100% turnover in the community staff members representing their partner organizations. Our success in capacity building was in part due to a long-range focus on building capacity.27,28 Fundamentally, CBPR needs and demands an ongoing emphasis on capacity building and CAB work procedures, along with initiation of-and revision to sustainability plans. Likewise, building relationships, trust, and shared vision within the broader community and clinical organizations is as important as targeting individual members. The challenge and opportunity for partnership and others is to apply lessons learned to address and minimize known and anticipated barriers, as well as amplify facilitators, in efforts to sustain evidence-based interventions into practice-based settings and ultimately improve the health of residents in medically-underserved regions.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and thank all members of the Partnering for Obesity Planning and Sustainability Community–Academic Advisory Board. This research was conducted at Virginia Tech. Jamie Zoellner, Donna Brock, and Bryan Price are now at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA. Paul Estabrooks and Jennie Hill are now at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, Nebraska, USA. Ramine Alexander is now at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Virginia, USA. At the time of the study, both Bryan Price and Ruby Marshall were administrative level community partners on the advisory board representing Danville Parks and Recreation and the Children’s Healthcare Center respectively. Morgan Barlow served as the independent facilitator for the advisory board.

The authors wish to acknowledge the following funding sources: National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities(R24MD008005) and Virginia Tech, Fralin Translational Obesity Research Center.

Contributor Information

Donna-Jean P. Brock, Public Health Sciences, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia.

Paul A. Estabrooks, Department of Health Promotions, University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska.

Harold M. Maurer, Department of Health Promotions, University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska.

Jennie L. Hill, Department of Epidemiology University of Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, Nebraska.

Morgan L. Barlow, Administration and Program Development, DukeImmerse Office of Undergraduate Education Duke University Durham, North Carolina.

Ramine C. Alexander, Department of Nutrition University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

Bryan E. Price, Community Outreach Cancer Center University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia.

Ruby Marshall, Sovah Health Danville, Virginia.

Jamie M. Zoellner, Public Health Sciences University of Virginia Charlottesville, Virginia.

References

- 1.Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E, eds. Methods in Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minkler M, Wallerstein N, eds. Community Based Participatory Research for Health: From process to outcomes. 2nd edition ed. San Francisco: Jossey Bass; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallerstein N, Duran B. Community-based participatory research contributions to intervention research: the intersection of science and practice to improve health equity. Am J Public Health. 2010;Suppl 1:S40–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tapp H, White L, Steuerwald M, Dulin M. Use of community-based participatory research in primary care to improve healthcare outcomes and disparities in care. J Comp Eff Res. 2013;2(4):405–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bodison SC, Sankare I, Anaya H, et al. Engaging the Community in the Dissemination, Implementation, and Improvement of Health-Related Research. Clin Transl Sci. 2015;8(6):814–819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savoye M, Berry D, Dziura J, et al. Anthropometric and psychosocial changes in obese adolescents enrolled in a Weight Management Program. J Am Diet Assoc. 2005; 105(3):364–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Epstein LH, Valoski A, Wing RR, McCurley J. Ten-year outcomes of behavioral family-based treatment for childhood obesity. Health Psychol. 1994;13(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golan M, Kaufman V, Shahar DR. Childhood obesity treatment: targeting parents exclusively v. parents and children. Br J Nutr. 2006;95(5):1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wolfenden L, Wiggers J, d’Espaignet ET, Bell AC. How useful are systematic reviews of child obesity interventions? Obesity Rev. 2010;11(2):159–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Altman M, Wilfley DE. Evidence update on the treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44(4):521–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katzmarzyk PT, Barlow S, Bouchard C, et al. An evolving scientific basis for the prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity. Int J Obes. 2014;38(7):887–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berrey M, Davy B, Dunsmore J, Berry D, Estabrooks P, Frisard M. Evaluation of pediatric weight management programs using the RE-AIM framework. Poster Presentation presented at Virginia Dietetics Association; 2012; Blacksburg VA. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilfley DE, Staiano AE, Altman M, et al. Improving access and systems of care for evidence-based childhood obesity treatment: Conference key findings and next steps. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2017;25(1):16–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Las Nuesces D, Hacker K, DiGirolamo A, LeRoi H. A Systematic Review of Community-Based Participatory Research to Enhance Clinical Trials in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(3 (pt 2)):1363–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurkowski JM, Lawson HA, Green Mills LL, Wilner PG 3rd, Davison KK. The empowerment of low-income parents engaged in a childhood obesity intervention. Fam Community Health. 2014;37(2):104–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jurkowski JM, Green Mills LL, Lawson HA, Bovenzi MC, Quartimon R, Davison KK. Engaging low-income parents in childhood obesity prevention from start to finish: a case study. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berge JM, Jin SW, Hanson C, et al. Play it forward! A community-based participatory research approach to childhood obesity prevention. Fam Syst Health. 2016;34(1):15–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coughlin SS, Smith SA. Community-Based Participatory Research to Promote Healthy Diet and Nutrition and Prevent and Control Obesity Among African-Americans: a Literature Review. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4(2):259–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skinner AC, Ravanbakht SN, Skelton JA, Perrin EM, Armstrong SC. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity in US Children, 1999–2016. Pediatrics. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):45–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zoellner J, Hill JL, Brock D, et al. One-Year Mixed-Methods Case Study of a Community–Academic Advisory Board Addressing Childhood Obesity. Health Promot Pract. 2017;18(6):833–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Virginia Department of Health Equity: Shortage designations and maps. http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/health-equity/shortage-designations-and-maps/ Accessed August 26, 2018.

- 23.United States Department of Labor. Bureau of Labor Statistics. BLS Data Viewer. https://beta.bls.gov/dataViewer. Accessed August 26, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. Quick Facts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045217, Accessed August 25, 2018.

- 25.Mettler M, Stone W, Herrick A, Klein D. Evaluation of a community-based physical activity campaign via the transtheoretical model. Health Promot Pract. 2000;1(4):351–359. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byington R, Naney C, Hamilton R, Behringer B. Dan River Region health assessment MDC, Inc.;October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zoellner J, Motley M, Hill J, Wilkinson M, Jackman B, Barlow M. Engaging the Dan River Region to reduce obesity: Application of the Comprehensive Participatory Planning and Evaluation Process. Fam Community Health. 2011;35(1):44–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motley M, Holmes A, Hill J, Plumb K, Zoellner J. Evaluating Community Capacity to Reduce Obesity in the Dan River Region. Am J Health Behav. 2013;37(2):208–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobs JA, Jones E, Gabella BA, Spring B, Brownson RC. Tools for implementing an evidence-based approach in public health practice. Prev Chronic Dis. 2012;9:E116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hill J, Zoellner J, Alexander R, et al. Development and pilot testing of iChoose: A community-based participatory adaptation and implementation of an evidence-based childhood obesity intervention International Society of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2016. (manuscript in preparation); Cape Town, Africa. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandoval J, Lucero J, Oetzel J, et al. Process and outcome constructs for evaluating community-based participatory research projects: a matrix of existing measures. Health Educ Res. 2012;27(4):680–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Graneheim U, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Butterfoss F. Coalitions and Partnerships in Community Health. San Fransisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(4 Suppl):S45–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL, Avila M, Belone L, Duran B. Reflections on Researcher Identity and Power: The Impact of Positionality on Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) Processes and Outcomes. Crit Sociol. 2015;41(7–8):1045–1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salimi Y, Shahandeh K, Malekafzali H, et al. Is Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) Useful? A Systematic Review on Papers in a Decade. Int J Prev Med. 2012;3(6):386–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zakocs RC, Edwards EM. What explains community coalition effectiveness? A review of the literature. Am J Prev Med. 2006;30(4):351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]