Abstract

Many unrelated proteins and peptides have been found spontaneously to form amyloid fibers above a critical concentration. Even for a single sequence, however, the amyloid fold is not a single well-defined structure. Although the cross-β hydrogen bonding pattern is common to all amyloids, all other aspects of amyloid fiber structures are sensitive to both the sequence of the aggregating peptides and the solvent conditions under which the aggregation occurs. Amyloid fibers are easy to identify and grossly characterize using microscopy, but their insolubility and aperiodicity along the dimensions transverse to the fiber axis have complicated detailed experimental structural characterization. In this paper, we explore the landscape of possibilities for amyloid protofilament structures that are made up of a single stack of peptides associated in a parallel in-register manner. We view this landscape as a two-dimensional version of the usual three-dimensional protein folding problem: the survey of the two-dimensional folds of protein ribbons. Adopting this view leads to a practical method of predicting stable protofilament structures of arbitrary sequences. We apply this scheme to variants of Aβ, the amyloid forming peptide that is characteristically associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Consistent with what is known from experiment, we find that Aβ protofibrils are polymorphic. To our surprise, however, the ribbon-folding landscape of Aβ turned out to be strikingly simple. We confirm that, at the level of the monomeric protofilament, the landscape for the Aβ sequence is reasonably well funneled toward structures that are similar to those that have been determined by experiment. The landscape has more distinct minima than does a typical globular protein landscape but fewer and deeper minima than the landscape of a randomly shuffled sequence having the same overall composition. It is tempting to consider the possibility that the significant degree of funneling of Aβ’s ribbon-folding landscape has arisen as a result of natural selection. More likely, however, the intermediate complexity of Aβ’s ribbon-folding landscape has come from the post facto selection of the Aβ sequence as an object of study by researchers because only by having a landscape with some degree of funneling can ordered aggregation of such a peptide occur at in vivo concentrations. In addition to predicting polymorph structures, we show that predicted solubilities of polymorphs correlate with experiment and with their elongation free energies computed by coarse-grained molecular dynamics.

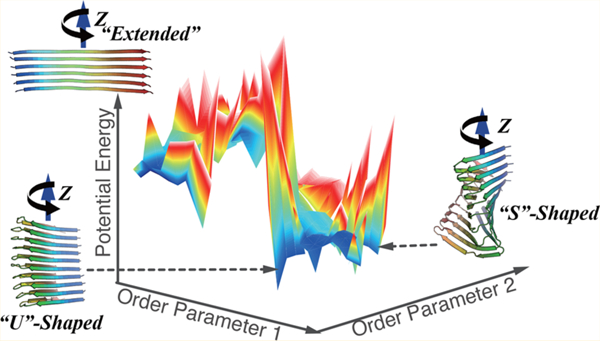

Graphical Apstract

INTRODUCTION

Along their twisting fiber axis, amyloid protofilaments are periodic, but along their two other transverse dimensions, individual protofilaments are aperiodic structures. As noted by Schrödinger, frozen aperiodicity gives molecular structures the ability to carry and preserve information, thus endowing them with the possibility to be alive.1 Indeed, some amyloid fibrils are able to multiply themselves and reproduce their particular structures from generation to generation.2 Apparently, using a secondary nucleation mechanism3 like that discovered by Eaton in the context of sickle cell hemoglobin aggregation,4 some of these protein fibrils can become infectious. Infectious protein particles called “prions” cause several neurodegenerative diseases, notably kuru, scrapie, and bovine spongiform encephalopathy (“mad cow disease”).5

The infectious agents in these prion diseases come in various strains, implying the existence of multiple polymorphs of their amyloid fibers. Each of these structures can reproduce itself faithfully and specifically and can lead to different courses of disease progression. The precise mechanism of infection by prions remains obscure.6 Nevertheless, there has been speculation that the development of the more common neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s may also involve an element of prion-like infection carrying the disease from neuron to neuron.7 In any case, it is well established that the amyloid fibrils found in Alzheimer’s patients can take on several distinct structures and are thus polymorphic.8 The structures of several of these polymorphs have been inferred through difficult and painstaking solid-state NMR methods.8–11 These considerations set the stage for the present paper, which aims to predict computationally the possible polymorph structures of amyloid fibrils and to characterize theoretically some of the aspects of their energy landscapes that underlie amyloid fibril polymorphism.

Ideally, the problem of amyloid polymorphism should be addressed kinetically, following the detailed molecular steps of nucleation, growth, fracture, and secondary nucleation through computation. It is hard not to believe that the formation of the observed polymorphs is primarily kinetically controlled.12 Nevertheless, here we initially take a different approach by surveying the energy landscape for the thermodynamically most stable fibril structures. We limit our survey to fibril polymorphs that preserve the energetically favored cross-β hydrogen bonding. This pattern of bonding leads to a layered structure with the layers stacking approximately normal to the fiber axis. We also limit our survey to the most commonly encountered arrangement of β-strands in the fibril core, the parallel in-register arrangement. Under these assumptions, when we look at several monomeric chains arranged in a stack, the assembly resembles a ribbon (see Figure 1). Possible polymorphs of the fiber then correspond to different two-dimensional folds of these ribbons. In this way, understanding the landscape of possible polymorphs can be looked at as a protein folding problem, but one in two dimensions: the two-dimensional folding of polypeptide ribbons. Under this ribbon hypothesis, the meanders of the ribbon and the locations of the contacting pleats of the ribbon are, at least initially, determined by the same solvent averaged forces that determine the tertiary folds of all globular proteins. In this paper, to study and exploit the ribbon polymorph force field landscape, we employ simulations using AWSEM. AWSEM (the Associative memory, Water-mediated, Structure and Energy Model) is a coarse-grained transferable force field that has been optimized using energy landscape theory to predict globular protein structure.13 For an evolved natural globular protein, AWSEM leads to a funneled energy landscape that guides the molecule to its native tertiary structure. In this paper, to implement the ribbon model in AWSEM, each chain is first replicated six-fold and the six chains are aligned in each layer in nearly exact registry and, after this, are then confined to these layers. This near-exact registry is expected if, in fact, amyloids form through the self-recognition of peptide fragments in different monomers, as has been hypothesized for some time14 and has been observed in AWSEM simulations of multidomain globular proteins.15 This registry is observed in most of the experimentally determined β-sheets in the amyloid fibril structures that are presently known. The registered ribbon hypothesis then reduces the prediction of possible amyloid fibril polymorphs to an effectively two-dimensional fold prediction problem, a problem one dimension lower from three-dimensional globular protein fold prediction. The details of implementing this idea in the LAMMPS instantiation of AWSEM are described in the Methods section.

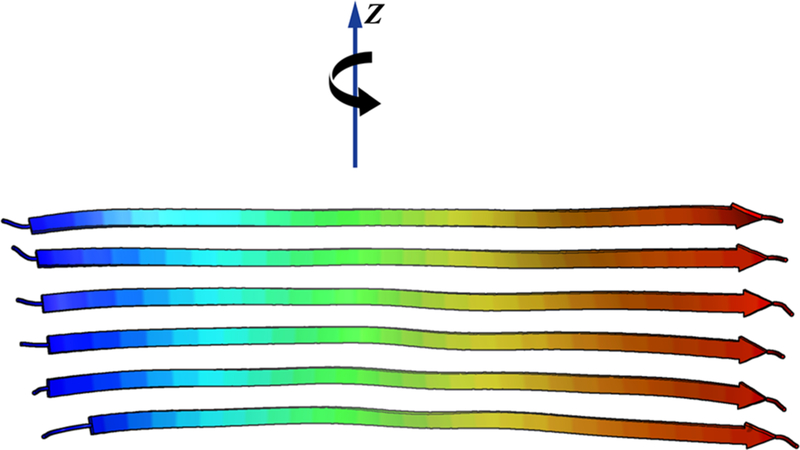

Figure 1.

Starting structure for ribbon-folding simulations. Six β-strands are arranged in a parallel in-register stack that is otherwise completely extended. During the ribbon-folding simulations, each β-strand is confined by a relatively stiff harmonic potential to remain in its original xy-plane, where the z-axis is taken to be parallel to the fibril axis. This scheme transforms the problem of predicting thermodynamically stable amyloid polymorphs into a two-dimensional ribbon-folding problem, where the forces that determine stable polymorphs are taken to be the same as those that guide globular protein folding in the absence of the ribbon constraints.

The present paper starts by describing the landscapes of protofilaments that have a single chain in each layer, which we call ribbon monomers. For illustration, we focus on peptides derived from Aβ, which is known to have a polymorphic amyloid landscape16–18 and is thought to be a key player in Alzheimer’s pathogenesis. Surprisingly, only a modest number of polymorphs come out of the structure prediction runs for the ribbon monomers. The sampled structures contain many features manifested by the experimentally observed structures, including a predominance of “U”-shaped structures that bring together two highly hydrophobic segments within the sequence of Aβ11−42. A detailed comparison of the polymorphs predicted using the ribbon-folding scheme with the currently available experimentally solved Aβ fibril structures shows that the predicted structures that are most similar to any given experimental structure have CE-RMSD values of between 2.5 and 4.0 Å when at least 75% of the residues are aligned.

The polymorphs produced by simulated annealing using the AWSEM-Ribbon model are distinguished in energy, and their energies can be usefully decomposed to help us understand why some polymorphs are more stable and may form more readily than the others. The total potential energy of the AWSEM-Ribbon Hamiltonian is a signature of the stability of an aggregate with fixed length. If we imagine the process of adding a monomer from solution to a preformed fibril as a two-step process involving, first, folding of the monomer into a structure that is compatible with the existing fibril template and, second, attaching this folded monomer structure to the end of the fibril, then the energy changes associated with each of these steps can be denoted as the “folding energy” and “binding energy”, respectively. We find that across polymorphs the binding energy is much larger than the folding energy and shows a correspondingly higher degree of variation. This comparison suggests that differences in backbone hydrogen bonding patterns and interchain side chain−side chain interactions more strongly influence polymorph stability than do the intramonomer side chain−side chain interactions. The sum of the folding and binding energies, i.e., the “elongation energy”, is proportional to the total energy change associated with the addition of an unfolded monomer from solution. This elongation energy ultimately dictates the relative thermodynamic stability of polymorphs that are allowed to grow and shrink through the addition and dissociation of monomers. The elongation energies should directly correlate with the solubility limits for forming each polymorph, and we can compute those differences for the possible predicted structures. In many systems, the degree of supersaturation, a thermodynamic quantity, also is a strong predictor of aggregation rate;19 therefore, all things being equal, the least soluble polymorph should form most rapidly and would be expected to dominate the race for survival among its polymorphic cousins. The predicted polymorph of Aβ11−42 with the most favorable elongation energy resembles the three “S”-shaped structures that have been determined by experiment for Aβ11−42 (∼4 Å CE-RMSD).

Next, we examine the free energy landscape of the Aβ11−42 ribbon and find that several distinct but structurally similar U-shaped structures, differing from each other mostly by subtle shifts in the intramonomer side chain interactions, are present in the “folded” basin, while the “unfolded” basin contains extended ribbons that are kinked at the location that will ultimately become the sharp turn in the U-shaped structures. Collapse of these extended structures comes with a large drop in the AWSEM contact energy as the two hydrophobic segments within Aβ11−42 come together, while moving from one structure to another within the folded basin can come about with relatively small changes in the total potential energy.

Studying the full thermodynamics and mechanism of formation of the predicted polymorphs of Aβ11−42 requires simulations without ribbon constraints. Once candidate polymorph structures are known, we develop free energy profiles for the initial stages of aggregation using a technique that we have already successfully employed for several other aggregating peptide systems.20,21 Applying this method allows us to determine the relative free energies of the dominant oligomeric species of various sizes and to extrapolate these free energies to concentrations other than that at which the system was simulated. The resulting estimates of the critical concentrations, above which the aggregation would proceed downhill to large aggregate sizes, indicate that the S-shaped polymorph of Aβ11−42, which was earlier found to have the most favorable elongation energy, does indeed have a lower critical concentration than the U-shaped polymorph.

While there are more distinct structures present on the landscape of the Aβ11−42 monomer ribbon than one would expect for a globular protein of similar size, the landscape is not overly complex. Just as for a natively folded globular protein, low-energy structures dominate the structure prediction simulations of amyloid ribbons, and the majority of the 100 predictions can be unambiguously assigned to a relatively small number of polymorph clusters. In other words, the polymorph landscape seems to display some degree of funneling. Is this funneled character an evolved feature of these landscapes, as is the funnel for tertiary folding of native proteins, or has the simplicity of the landscape arisen in some other way? To begin to answer this question about selection, we also characterized the fibril landscape of two distinct ribbon monomers made up of peptides having scrambled Aβ11−42 sequences. The landscapes of these randomized sequences turn out to be more rugged than the landscape that was found for the natural Aβ11−42 sequence. The scrambled sequences give rise to a greater diversity of structures. All of these structures are much less stable than the dominant polymorphs sampled by the ribbon-folding technique for the natural Aβ11−42 sequence. The fact that all of the polymorphs of the scrambled sequence are less stable than those of the natural Aβ sequence suggests that there is another form of selection, other than natural selection, likely at work: Aβ has attracted the attention of researchers because it forms aggregates in vivo. The low solubility necessary to do this, we see, arises from the unusual degree of funneling in the amyloid polymorphic landscape for the natural sequence. Thus, the funneled landscape of the Aβ ribbon may have no fitness value to the host organism but, rather, is related to Aβ’s ability to rapidly form large aggregates at the modest concentrations found in vivo.

The most common variants of Aβ in vivo are Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42. In most experimentally determined Aβ fibril structures, the first 10 residues on the N-terminal end are left unresolved or are stabilized by contacts with other copies of Aβ in the plane. These N-terminal residues seem to be largely disordered in fibril structures, in contrast with the latter 30 or 32 residues, which make up the fibril core. To understand the influence of these additional residues on the ribbon monomer folding landscape of Aβ, we performed ribbon-folding polymorph prediction simulations on both of the longer sequence peptides, Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42. For both of these ribbon constructs, the predicted structures exhibit a high degree of fraying on their N-termini despite the presence of the ribbon constraints, consistent with their tendency toward disorder as manifested in the absence of resolved N-terminal segments in most of the available experimental structures.

In this work, we focus mostly on the polymorphism arising from different two-dimensional folds of ribbon monomers. The experimentally determined protofibril structures for Aβ, however, invariably have several chains (two or three) in each layer,22 which allows diversity in the relative placement of the chains in a plane. We also therefore study the landscapes of oligomers of ribbons. In the oligomer structure prediction simulations, several ribbon monomers are allowed to fold and dock. In most trajectories, the ribbon monomers fold independently before docking, which leads to a diverse set of structures that mostly lack symmetry. Nonetheless, out of 100 prediction simulations on dimers, we found 5 resulting structures having approximate symmetry. All of these symmetrical structures have particularly favorable binding energies, suggesting that they would indeed have the lowest solubilities and would win out over the asymmetric structures for aggregation mechanisms involving a step of lateral association of protofilaments. Several of the symmetric dimer structures sampled in the ribbon dimer predictions strongly resemble an experimentally determined Aβ fibril structure with two-fold symmetry. Trimer structures are found experimentally too, but the landscape for trimers was apparently too extensive to sample because no structures with exact three-fold symmetries showed up in the simulated annealing simulations of ribbon trimers.

METHODS

AWSEM-Ribbon Force Field.

The Associative memory, Water-mediated, Structure and Energy Model (AWSEM) is a coarse-grained protein force field that represents the conformation of the protein at the resolution of three atoms per residue. This resolution is sufficient to reconstruct the complete backbone unambiguously. AWSEM was parametrized by applying an algorithm that relies on the principles of energy landscape theory23 to a database of experimentally determined protein structures to learn tertiary interactions that give rise to funneled landscapes. We encourage those readers who are interested to see Davtyan et al.13 for a complete description of the AWSEM force field. For a historical and pedagogical overview that covers the principles of landscape optimization and the development of the AWSEM force field and its predecessors, see Schafer et al.24 The AWSEM-Ribbon Hamiltonian as summarized in eq 1 is made up of the optimized transferable tertiary energy terms along with the specific knowledge-based terms from ordinary AWSEM with the addition of a “ribbon constraint”.

| (1) |

Among the terms in eq 1 that are transferable between proteins, the backbone term, Vbackbone, ensures that the backbone adopts protein-like conformations, following the rules set forth by Pauling.25 The burial term, Vburial, is a many-body term that attempts to sort each of the residues into particular burial environments, ranging from completely buried to completely exposed, depending on the amino acid type burial preferences. The contact term, Vcontact, which also takes into account the local density of the interacting residues, has direct contact, protein-mediated, and water-mediated terms. The hydrogen bonding term, VHB, assists in the formation of secondary structures by favoring formation of hydrogen bonds in either α-helices or β-sheets. Information from a secondary structure prediction can be introduced to VHB as additional guidance. For the purposes of predicting ribbon-folded structures, each residue is assigned a β-sheet preference, consistent with the presumed cross-β hydrogen bonding pattern of the predicted structures. The fragment memory term that is usually employed in AWSEM simulation predictions for globular proteins has been left out of the Hamiltonian in this study due to the under-representation of amyloid structures in the presently existing protein databases.

The full AWSEM force field has already been used with considerable success in predicting globular protein structures for both monomers and dimers. AWSEM has also been used to study the initial stages of misfolding and aggregation of Titin,26 Aβ1−40,27 Aβ1−42,28 polyglutamine repeats,20 and Huntingtin Exon1 fragments.21 We have recently developed the AWSEM-Amylometer algorithm,29 which is based on the AWSEM Hamiltonian. The AWSEM-Amylometer has proved able to predict both the aggregation propensity and the topology of fibrils with good accuracy,29 again giving confidence that the ingredients of the AWSEM force field are adequate for understanding amyloid formation.

Implementation of Ribbon Constraints.

Almost all explicitly solved amyloid fibril structures have a parallel in-register arrangement of the hydrogen bonds, with each monomer approximately spanning across one layer in its fibril form in two dimensions, like a ribbon. To implement the ribbon model in AWSEM, each chain is first replicated six-fold and the six chains are aligned in stacked layers and in perfect registry. During the simulations, each chain is confined to a given layer by applying harmonic forces along the z-axis, with strength 1.0 kcal/mol/Å2 (kribbon in eq 2). Different layers are restricted to different xy-planes separated from each other by 5 Å to approximate the typical β-strand separation in β-sheets. This 5 Å distance between neighboring layers allows for the formation and stabilization of hydrogen bonds. The strength of the ribbon constraint, kribbon, is relatively large but allows for fluctuations along the z-axis and in this way also allows for the formation of twisted β-sheets, as are sometimes seen in experimentally determined fibril structures. With these ribbon constraints in place, the preformed β-sheet ribbon can sample widely across the two-dimensional ribbon-folding space to find favorable configurations, which we take as predictions of possible protofilament polymorphs. In eq 2, j is the layer index, and i is an atom index. zi is the z-coordinate of atom i in layer j, and zj is the z-coordinate of the jth layer. The bias is applied to all three explicitly represented atoms for 16 residues along the chain. These fiducial sites were chosen to be approximately equally distributed along the sequence being simulated.

| (2) |

Simulation Details for Predicting Ribbon Structures.

Prediction simulations using the AWSEM-Ribbon Hamiltonian were performed using the Large-Scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator (LAMMPS) software package.30 For each of the ribbon constructs, 100 annealing simulations from 300 to 200 K were performed in 2 million steps with a time step of 5 fs. All of the predictions start from a fully extended ribbon that is already a β-sheet. In order to accelerate the two-dimensional folding process, a weak cylindrical radius of gyration bias (0.05 kcal/mol/Å2) in the xy-plane is applied.

Clustering Analysis of Predicted Ribbon Structures.

A hierarchical algorithm, with a “centroid” linkage scheme, is used to cluster the predicted ribbon structures obtained by annealing at the end of each AWSEM-Ribbon simulation. We obtain clusters by using the set of mutual-Q order parameters to build the linkage matrix.31 Q as defined in eq 4 is symmetric. The mutual-Q value for a pair of structures is obtained by assuming that one of the structures is this “native” structure (has pair distances ) and computing the Q of the other structure using the native structure as a reference. Clusters of structures are identified as being those sets of structures that have an average mutual-Q value of greater than 0.6. The centroid structure of each cluster is visualized in the accompanying figures. The mean value of the mutual-Q inside of each cluster roughly describes the tightness of the cluster.

Calculation of the Binding Energy, Folding Energy, and Elongation Energy.

From a thermodynamic perspective, the process of elongating a ribbon by monomer addition can, in principle, be divided into two steps: folding of the monomer into a conformation that is the same as the monomers that are already incorporated into the ribbon and binding of this folded monomer to the pre-existing ribbon. The first step is associated with an energy change Efolding, while the second step gives an energy change Ebinding. Therefore, the total energy associated with elongation of the ribbon by one monomer, Eelongation, can be computed within the AWSEM Hamiltonian, as shown in eq 3, where Efolding, Ehexamer, and Epentamer are the AWSEM energy evaluated on a structure with either one copy, six copies, or five copies, respectively, of the folded peptide arranged in a ribbon stack.

| (3) |

Computing Ribbon Free Energy Landscapes.

To compute the various ribbon free energy profiles for a sequence, we used umbrella sampling along an order parameter, Q, with respect to a given fiducial structure for the ribbon. The fiducial structure can be one of the “predictions” from the annealing runs or an experimentally determined structure. The harmonic biasing potential used for constant temperature (300 K) umbrella sampling simulations for 8 million steps is shown in eq 4.

| (4) |

In eq 4, kQ-bias = 500 kcal/mol. The biasing center values Q0 were chosen to be equally spaced from 0 to 0.98 with a step size 0.02. The weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM)32 was then used to obtain the unbiased free energy landscapes, which can also be extrapolated to temperatures other than the temperature at which the sampling was carried out.

Calculation of Grand Canonical Free Energy Profiles, Fn − nμ, for Oligomerization of Monomer Ribbon Polymorphs.

Similar to the computation of ribbon free energy landscapes, the calculation of aggregation free energy profiles along the aggregation pathway toward the formation of a particular fibril structure can be done by using importance sampling along the biasing coordinate Q with respect to a given fibril structure. Because the number of peptides in clusters must be allowed to vary, unlike for the computation of ribbon free energy landscapes described above, however, for the calculation of the grand canonical free energy profiles, the ribbon constraint, Vribbon, was not applied during the simulations. Simulations of 10 peptide chains were performed in a cubic box (1000 Å × 1000 Å × 1000 Å) with periodic boundary conditions for 8 million steps at 300 K. The initial configurations of the umbrella sampling for unconstrained oligomer simulations are 10 monomers randomly distributed over the cubic box, which gives a nominal concentration of around 16 μM. For each snapshot output from these simulations, order parameters including the size of the largest oligomer present are calculated. The unbiased free energy landscapes along the biasing coordinate, Q, were reconstructed from the above sampling data using WHAM and then projected onto the size of the largest oligomer in the simulation box to give the free energy as a function of oligomer size, Fn.

During the simulation of peptide aggregation, the concentration of free monomers varies, decreasing due to association of individual monomers as they form larger aggregates. Depletion of the free monomers must be taken into account in the calculation of the grand canonical free energy profiles versus aggregate size. We have detailed our approach to correct for this finite size effect from simulation results in our earlier papers on Aβ aggregation27 and poly-Q aggregation.20 We review this briefly below.

In a system with N monomers, when only one oligomer of size n is formed and the rest N − n free monomers remain unassociated, the probability that there is at least one n-oligomer in the system according to the approach of Reiss and Bowles’s33 is given by eq 5.

| (5) |

In eq 5, Qn(N,V,T) is the partition function of the system constrained to contain at least one n-sized oligomer and Q(N,V,T) is the total unconstrained partition function. qn(V,T) is the partition function of the oligomer including interactions with with the remaining N − n monomers, and Q(N − n,V,T) is the partition function for the decoupled remaining N − n monomers. μ is the chemical potential of a monomer. In our simulations, multiple large n-oligomers are rarely found simultaneously; therefore, Pn is roughly equal to the probability that there is exactly one n-oligomer in the system. The relative free energies of clusters of size n are then given by eq 6.

| (6) |

Equation 6 is then used to compute the thermodynamic potential for the grand canonical ensemble, Fn − nμ. The gradients of this potential determine the growth or dissociation of clusters of size n in a system of fixed chemical potential μ.

Once we have the free energy for the grand canonical ensemble Fn − nμ at a given concentration C0, we can extrapolate the free energy to any different concentration C1 by using eq 7.

| (7) |

In eq 7, μ1 and μ0 are the chemical potentials of the free monomers at concentrations C1 and C0, respectively. This scheme assumes that aggregation proceeds at a low enough concentration so that thermodynamic crowding effects in the supernatant solution are negligible.

RESULTS

Predicted Polymorphs for a Monomeric Ribbon of Aβ11−42.

We first compute the polymorph landscape of the short peptide Aβ11−42 by folding the monomer ribbon composed of six Aβ11−42 peptides. The details of the way that ribbon polymorph predictions are performed can be found in the Methods section. In brief, six copies of the target sequence are stacked in an in-register parallel β-sheet, and with ribbon constraints ensuring that each peptide remains close to its original xy-plane (where the z-axis is parallel to the fibril axis), the ribbon is allowed to fold as the temperature is gradually lowered. This procedure, which we repeated 100 times while varying the initial velocities assigned to the particles in the system, yields a panel of low-energy predictions of ribbon polymorphs. Clustering analysis, based on the similarity measure mutual-Q, was performed on the 100 predicted structures to visualize and quantify the similarities and differences between the predicted structures (see Figure 2A). We identify each tight and significantly populated cluster as a polymorph. These polymorphs, along with their average energies, constitute the polymorph landscape. For the Aβ11−42 peptide, seven significantly populated clusters covering about 90% of all of the predictions are obtained by clustering analysis, where the average mutual-Q within a cluster satisfies Qavg > 0.6. This value of Qavg means that the structures within a cluster visually all appear to be quite similar to each other.

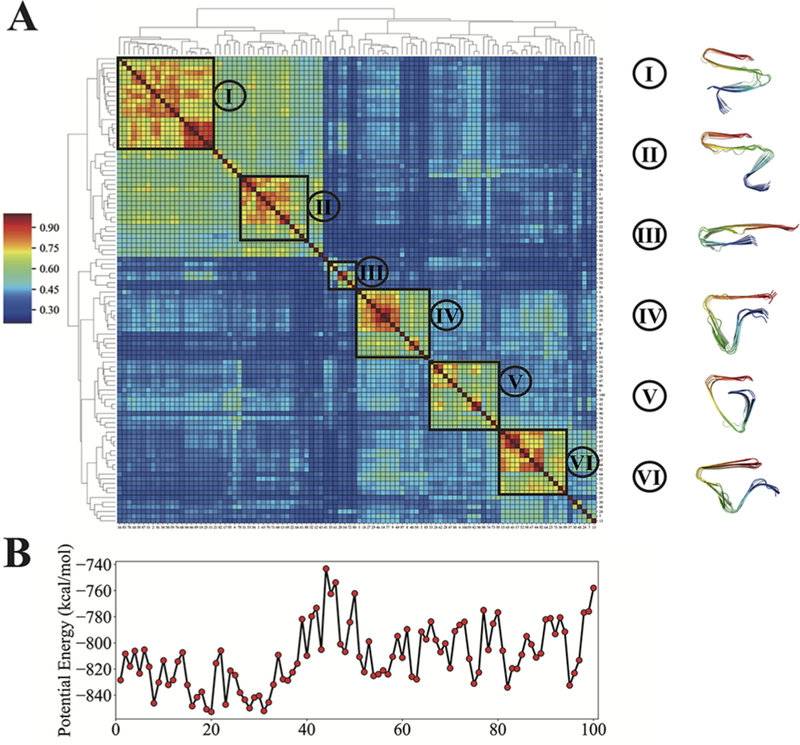

Figure 2.

Polymorph landscape of the monomeric Aβ11−42 ribbon. (A) Clustered polymorphs for 100 predictions of six Aβ11−42 peptides in a monomer protofilament, using mutual-Q as the metric for measuring structural similarity. One hundred predicted ribbon structures were hierarchically clustered and are shown in a heatmap on the left. The identified clusters are enclosed in black squares on the heatmap, and the centroid structure from each cluster is shown and colored according to the sequence index from blue (N-terminal) to red (C-terminal) on the right. (B) Potential energy values of 100 predicted structures in the same order as the clustered results shown in panel (A). (C) Energies of folding a Aβ11−42 monomer into a structure that is compatible with the fibril polymorph. (D) Binding energies of folded monomers when bound to pentamer fibrils. (E) Energy gain of elongation by one monomer. The energy values of selected low-energy clusters are labeled by their corresponding cluster indices.

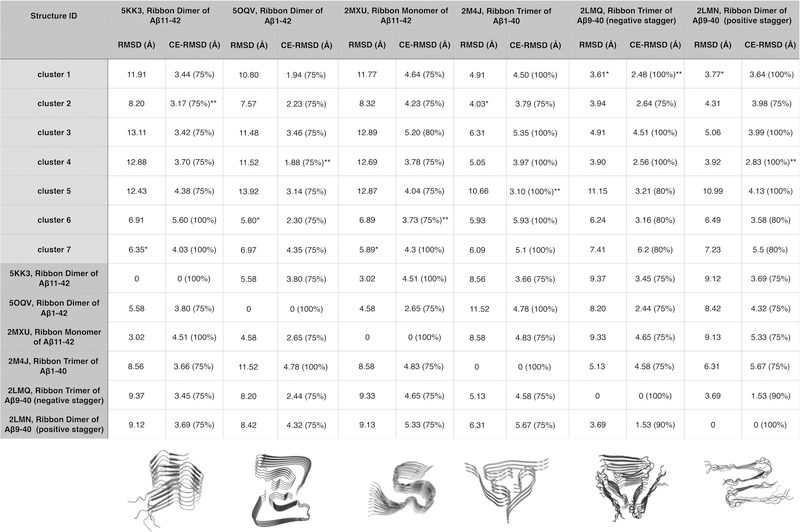

In Figure 3, we provide a summary of structural comparisons between the predicted polymorph cluster centroid structures and the available experimentally determined Aβ fibril structures. We also include similar comparisons of the different experimental structures with each other. Both the predicted and the experimentally determined structures are approximately periodic along their (sometimes twisting) fibril axes, meaning that the folds of the different monomers within the fibril segments are largely the same. We therefore made structural comparisons on the basis of monomers taken from the structures rather than on the basis of whole hexamer fibril segments. There are six experimentally determined structures listed in Figure 3. The first four of the six experimental structures (5KK3, 5OQV, 2MXU, and 2M4J) satisfy the “one-molecule-per-plane” aspect of the ribbon constraint: all of the residues in each chain of these structures occupy a single z-plane within the tolerance of the harmonic constraining potential. These structures can therefore be directly compared to our predicted polymorphs. The last two experimental structures (2LMQ and 2LMN) do not satisfy the one-molecule-per-plane aspect of the ribbon constraint. Instead, they exhibit a “stagger” in which two halves of the Aβ9−40 structure occupy two different z-planes. For these structures, the interactions between side chains are made within the plane between two different copies of the Aβ molecule. These interactions between distant monomers in the experimental structures, in fact, are quite isomorphic to those within the monomers for some of the polymorphs that were predicted using ribbon constraints. This similarity can be seen in the contact maps (Figure S3). We also can compare the overall structures of the predicted polymorphs to the experimental structures that exhibit a stagger by combining the coordinates for residues 9−24 from one copy of Aβ in the experimental structures with the coordinates for residues 29−40 of another copy of Aβ. The copies of Aβ whose coordinates were combined were chosen such that the two halves occupy the same z-plane. The combined coordinates were then used as the reference structure for comparison to both the predicted polymorph structures and to the other experimental structures that do satisfy the ribbon hypothesis. Once we obtained the monomer reference structures from the fibril segments, either by directly taking a single monomer structure (for the predicted polymorphs and for the experimental structures without a stagger) or by combining the coordinates from two copies of Aβ as described above (for the experimental structures with a stagger), we computed both the standard RMSD and the CE-RMSD values between all pairs of monomers. The CE alignments, often used in assessing globular protein structure predictions, allow deletions of those parts of the structure that do not match up. Thus, the fraction of matching residues is also indicated. The results of this analysis are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Summary of structural comparisons between the predicted structures of monomeric ribbons of Aβ11−42 and experimentally determined structures of Aβ fibrils. Seven representative structures from the seven identified clusters are compared with six experimentally determined structures of Aβ fibrils: a ribbon dimer of Aβ11−42 (PDB ID: 5KK3), a ribbon dimer of Aβ1−42 (PDB ID: 5OQV), a ribbon monomer of Aβ11−42 (PDB ID: 2MXU), a ribbon trimer of Aβ1−40 (PDB ID: 2M4J), a ribbon trimer of Aβ9−40 with a negative stagger (PDB ID: 2LMQ), and a ribbon dimer Aβ9−40 with a positive stagger (PDB ID: 2LMN). The RMSD and CE-RMSD values (along with the percentage of aligned residues in the CE alignment) are shown for each comparison. The structures of 2LMQ and 2LMN have a stagger, meaning that two halves of a single copy of Aβ occupy two different z-planes, where the z-axis is parallel to the fibril axis. The current ribbon-folding scheme assumes that fibrils do not have a stagger. To compute the RMSDs and CE-RMSDs of our predicted structures and the other experimental structures from 2LMQ and 2LMN, we combined the coordinates of the N-terminal (residues 9−24) and C-terminal (residues 29−40) halves of two copies of Aβ that occupy the same z-plane in the experimental fibril structure and used those combined coordinates as the reference structure. For each experimental structure, the lowest RMSD values (*) and CE-RMSD (**) values from the set of predicted structures are indicated with asterisks.

It is useful when evaluating the results of the polymorph predictions to first examine the comparisons among the experimental structures themselves, which can be found under the table in Figure 3. All of the experimental structures except for one were reported as being ribbon oligomers, i.e., oligomeric protofilaments. Only 2MXU was reported as being a monomeric protofilament.34 In the paper that reported the structure of 2MXU, the authors state that their structural data are also consistent with a dimer of protofilaments, but the authors did not report the dimer structure. In the following year, a fiber structure with a protofilament structure that is highly similar to that of 2MXU, 5KK3, was reported as a dimer.35 Thus, it seems safe to assume that the stable forms of most large Aβ fibrils have multiple protofilaments in their cross sections. Furthermore, the experimental structures cluster into two dominant protofilamentary ribbon folds depending on whether or not residues 41 and 42 are present. Those constructs that include residues 41 and 42 (Aβ11−42 and Aβ1−42) have S-shaped ribbon folds and are ribbon dimers. Those constructs that lack residues 41 and 42 (Aβ1−40 and Aβ9−40) have U-shaped ribbon folds and form either ribbon trimers or ribbon dimers. Thus, assuming that the ribbon oligomer landscape selects from relatively stable ribbon monomer conformations, the experimental studies suggest that, grossly speaking, there are two dominant ribbon monomer folds of the Aβ sequence: U-shaped structures and S-shaped structures.

Turning back now to the ribbon monomer structures of Aβ11−42 predicted by ribbon-folding simulations, we see that Cluster 1 is the largest cluster. This dominant cluster contains more than 60% of the predictions. The common structural theme in this cluster is a two-layer U-shaped structure (Figure 2A). The kinked turn region, GSKNKG, connects the two highly amyloidogenic segments, Aβ16−21 and Aβ30−35, and is the same turn that has been emphasized by Nussinov and co-workers.36 This pairing of the amyloidogenic segments is also seen in several experimentally determined structures and is consistent with AWSEM-Amylometer calculations.29 The centroid structure from Cluster 1 has a RMSD value of 3.61 Å and a CE-RMSD value of ∼2.5 Å in comparison with the Aβ fibril structure (PDB ID: 2LMQ) inferred from solid-state NMR and electron microscopy measurements by Tycko and co-workers8 (Figure 3). The Cluster 1 centroid structure is also quite similar to 2LMN, with a RMSD value of 3.77 Å and a CE-RMSD value of 3.64 Å. The predicted structure that is closest in terms of RMSD to 2M4J is the centroid structure of Cluster 2, which has a RMSD value of 4.03 Å from 2M4J. Cluster 2 from the predictions contains “e”-shaped ribbon structures that are different from all currently known structures for fibrillar Aβ peptides. The C-terminal residues in the e-shaped structure protrude in between the two amyloidogenic segments, thus making the ribbon overall more compact than what is seen in the existing experimental structures. Clusters 3 and 5 display U-shaped ribbons, but structures in these clusters have somewhat different interfaces between their layers and different patterns of curvature than do structures in Cluster 1. Structures from Clusters 3 and 4 visually resemble the structures in Cluster 1 and share a fairly high mutual-Q of ∼0.55 with structures in Cluster 1. Structures from Clusters 1, 2, and 4 all have relatively low CE-RMSD values relative to the solid-state NMR structure 2LMQ.

In addition to finding these clusters containing U-shaped and e-shaped structures, one also finds in the annealing results that Clusters 6 and 7 display inverted S-shaped ribbons with two sharp β-turns occurring around three glycines. Cluster 6 has a CE-RMSD of ∼4 Å over the 75% of the residues that overlap with the experimentally determined structure with PDB ID 2MXU (Figure 3). Structures from Cluster 6 largely maintain the U-shaped character of the clusters discussed above, with only the last few residues on the C-terminal end turning back to make contact with one of the layers in the U-shape. Structures from Cluster 7 show significant twists along the fibril elongation axis. The twisted ribbon structures in Cluster 7 are structurally similar to the PDB structures 5KK3 and 2XMU, with a CE-RMSD of ∼4 Å over all of the overlapping residues. The centroid structure that is most similar to 5OQV is that of Cluster 6, with a RMSD of 5.8 Å.

Overall, the ribbon monomer predictions for Aβ11−42 are more similar to the experimental U-shaped structures than they are to the experimental S-shaped structures. Nonetheless, in the predictions, we do find structures that are similar to the experimental S-shaped structures. Taken together with the experimental structures, these prediction results suggest that the existing experimental structures cover the dominant basins of the ribbon monomer landscape of Aβ and that stable ribbon oligomer structures are made from relatively stable ribbon monomer folds that can associate in various ways to yield additional polymorphism at higher length scales of organization.

To have an energetic picture of the different clustered polymorphs, we plot several different energies for each of the 100 structural predictions in the same order from hierarchical clustering (see Figure 2B). For each structure, we plot the potential energy, the folding energy, the binding energy, and the elongation energy. Details of how these energies are computed can be found in the Methods section. Clusters 1, 2, 3, and 7 are energetically much more favorable than the other clustered polymorphs according to their potential energies. The other predictions that do not fall into any of the seven dominant clusters are all energetically unfavorable in comparison. Structures in Cluster 7, which adopt an S-shaped topology, have the lowest potential energy, as well as the most favorable binding energy and elongation energy upon the addition of free monomers (Figure 2E). In comparison, the energetic stabilization for elongation in Cluster 1 is around 20 kcal/mol less favorable than it is for Cluster 7 (Figure 2E). These elongation energies should correlate with the solubility limits for forming such polymorphs. Thus far, only structures with an inverted S-shaped topology like that seen in Cluster 7 have been observed for Aβ11−42 (PDB IDs: 5KK3, 5OQV, and 2MXU), suggesting that these topologies do indeed dominate kinetically, in keeping with their much more favorable elongation energies and lower predicted solubilities.

Ribbon Free Energy Landscape of the Aβ11−42 Monomer Ribbon.

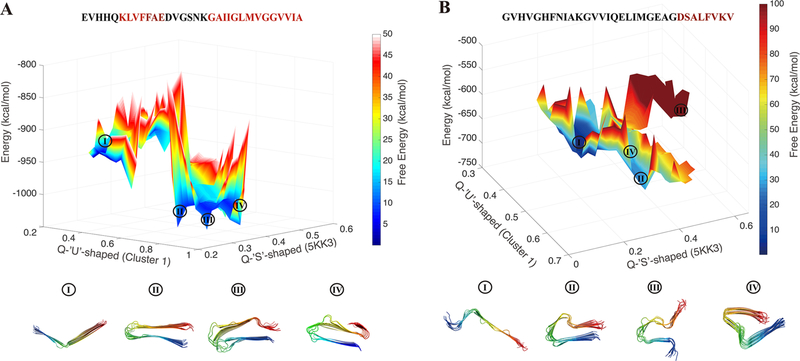

To better understand the energy landscape of amyloid fibrils under the ribbon constraints, we computed a free energy surface for Aβ11−42 as a function of several order parameters. We computed the free energy surface as a function of QU-shaped and QS-shaped. QU-shaped is a measure of the structural similarity to the centroid structure of Cluster 1, the dominant cluster found in the prediction of Aβ11−42 polymorphs. QS-shaped is a measure of the structural similarity to an experimentally determined Aβ fibril structure, 5KK3. The free energy surface as a function of these two order parameters is shown at a temperature of 300 K in Figure 4. The AWSEM-Ribbon energy is indicated on the vertical axis. There are two large basins with low free energy: the first basin with QU-shaped ≈ 0.4 and QS-shaped ≈ 0.2 contains unfolded and extended ribbons; the other basin, with a QU-shaped ≈ 0.9, contains folded ribbons with U-shaped topologies. We also visualized representative structures from both basins. Schmidt et al. have presented a cryo-EM reconstruction with two extended monomers of Aβ1−42 with a poorly ordered N-terminus.37 The unfolded ensemble from our sampling configurations shares a good deal of structural similarity with a monomer from within the dimer structures that Schmidt et al. observed. The high barrier between the unfolded and folded basins implies, unsurprisingly, that transitions between fibril polymorphs via an extended state would be very slow. The folded ribbons (QU-shaped > 0.6) are heavily energetically favored because the potential energy drops sharply as the similarity to solved structures grows. The energy differences among the U-shaped structures within the folded basin are significant but small compared to the energy gap between the folded and unfolded states. The lowest-energy U-shaped structures have the turn in a location that yields two approximately equal length β-strands, which in turn leads to a straight and well-ordered protofilament. The higher-energy U-shaped structures are either curved or have an additional kink and display more fraying near the turn region than does the straight filament structure.

Figure 4.

Ribbon energy landscapes for the Aβ11−42 monomer ribbon and a scrambled variant at 300 K. (A) Free energy landscape of a natural Aβ11−42 protofilament under ribbon constraints plotted using Q with respect to an S-shaped structure, 5KK3, and Q with respect to the U-shaped structure, the centroid structure from Cluster 1. In both parts of the figure, the free energy values are indicated with color coding ranging from blue, the most stable, to red, highly disfavored. The AWSEM-Ribbon energy is indicated on the vertical axis. To give an idea of the ruggedness of the landscape, the mean value of the potential energy has been augmented by a random fluctuation chosen from a Gaussian distribution computed using the local value of the variance of the potential energy. The potential energy is low when the ribbon is folded into U-shaped forms, while the potential energy remains high when the ribbon is not compact. The local basins for different polymorphs are labeled with Roman numerals. Representative structures from each basin are shown below the free energy surface. The monomers within the ribbon are colored from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus). The expectation value of the potential energy decreases as QU-shaped increases, dropping sharply at around QU-shaped ≈ 0.6. (B) The free energy landscape of the scrambled Aβ11−42 protofilament under ribbon constraints is plotted in the same manner as that of the unscrambled sequence in panel (A). Unlike what was found for the natural (unscambled) Aβ11−42 sequence, the average potential energy is relatively flat across the sampling space. Thus, the fluctuations are relatively more prominent than those for the natural sequence. The segments of the sequences that are predicted to be amyloidogenic according to the AWSEM-Amylometer are colored red in the one-letter representations of the sequences above the free energy surfaces. The natural variant has two such sequences, leading naturally to association into a U-shaped structure, while the scrambled variant contains only one segment that is predicted to be amyloidogenic.

Grand Canonical Free Energy Profile of Oligomerization for Several Predicted Polymorphs of Aβ11−42.

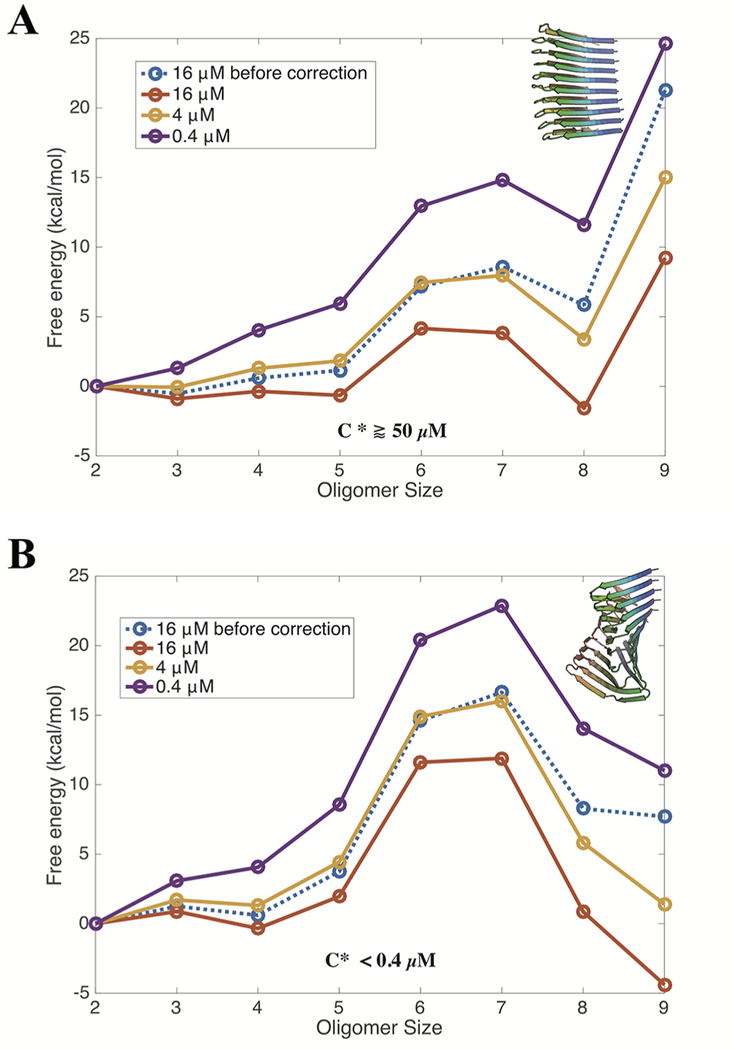

In previous studies, we have shown that predictions of fibril solubilities obtained by computing the aggregation free energy landscapes using AWSEM agree well with existing measurements for Aβ1−40,27 Aβ1−42,28 and Huntingtin Exon-1 fragments.21 We therefore again employ umbrella sampling using the similarity, Q, to several of the different polymorphs as biasing coordinates to find free energy profiles along the aggregation pathway for forming each of the referenced polymorphs. By sampling the configurations of a fixed number of molecules in a periodic box and monitoring the size of the largest cluster, we compute the aggregation free energy profiles of Aβ11−42 for forming two of the polymorphs predicted during the annealing simulations: a U-shaped structure from Cluster 1 and an S-shaped structure from Cluster 7, shown in Figure 2. As shown in the 1D free energy plot detailing the formation of the Cluster 1 polymorph at the nominal concentration of the simulation, 16 μM, the free energy eventually becomes uphill as the oligomer size grows (Figure 5A). The uphill slope at large n indicates that aggregation toward a 9-mer is unfavorable at this nominal concentration. In comparison, the aggregation profiles for forming the Cluster 7 polymorph are uphill at small oligomer sizes (n ≤ 7) but eventually become downhill for larger sizes (Figure 5B), suggesting that large oligomers adopting the structure of the Cluster 7 polymorph are lower in free energy compared with those adopting a Cluster 1 structure. The Cluster 7 polymorph is therefore predicted to be less soluble.

Figure 5.

Grand canonical free energy profiles for Aβ11−42 forming either a Cluster 1 or Cluster 7 structure at a temperature of 300 K. The grand canonical free energy, F − nμ, as a function of oligomer size and corrected for the monomer concentration changes in the fixed number simulation allows one to infer the critical value of the concentration of free monomers. The aggregation free energy profiles for the Cluster 1 polymorph (A) and the Cluster 7 polymorph (B) were obtained by simulating 10 monomers in a box at a concentration of 16 μM. The uncorrected free energy profiles are shown with blue dashed lines. The solid lines represent the aggregation profiles after accounting for the finite size effect33 and extrapolating to concentrations other than the one at which the simulation was performed. The last data point (n = 9) is the most uncertain because of the sparse sampling of when the initial monomer pool is maximally depleted.

Fibril Polymorphism of Scrambled Aβ11−42 Sequences.

In the polymorph landscape of Aβ11−42, the modest number of polymorphs predicted in annealing runs parallels the rather small number of structures that have been characterized in detail in the laboratory. The existence of a dominant cluster and several minor clusters seems to suggest some degree of funneling with ruggedness of the landscape for the natural sequence. The rugged features of fibril polymorphism have been emphasized by Nussinov and co-workers.38 To us, more remarkable than finding ruggedness in the polymorph landscape is the apparent existence also of a polymorph funnel, similar to the funnel for tertiary folding of globular proteins.23 The funnel for functional globular proteins is sculpted by evolution, according to energy landscape theory, and indeed, this aspect of the theory has been confirmed by comparing the physical landscape with evolutionarily informed landscapes obtained independently by direct coupling analysis of protein families:39,40 natural sequences are selected for foldability.

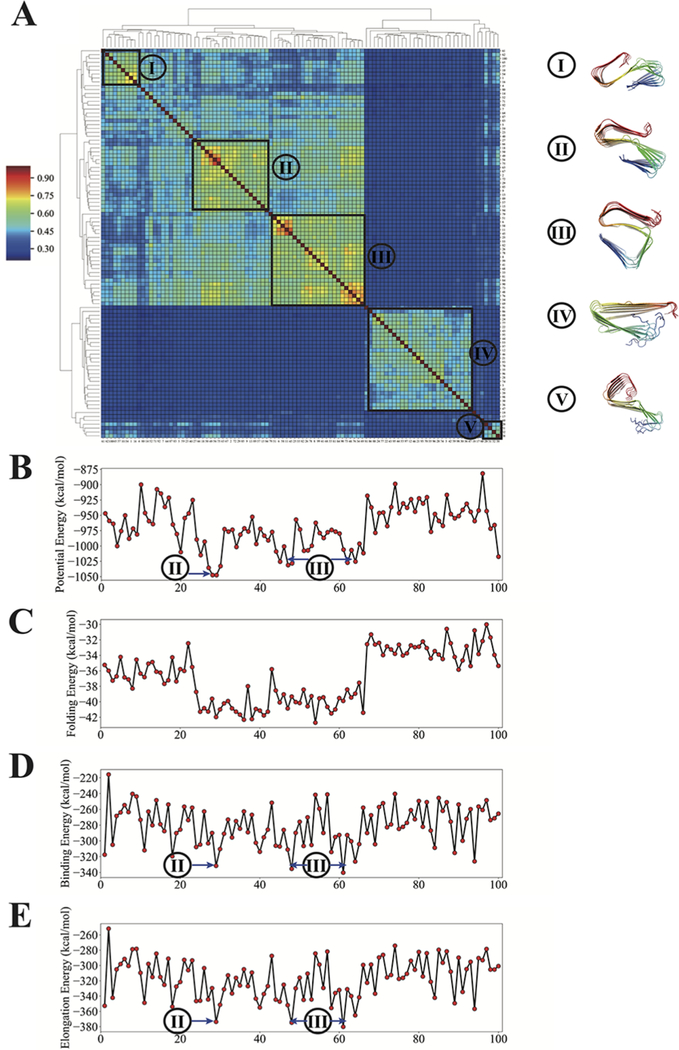

To check whether the polymorph funnel arises from evolution or some other form of selection, we also surveyed the polymorph landscapes for two scrambled Aβ11−42 sequences (Figures 6 and S1). Unlike the situation for the natural sequence, the landscapes of the predictions for the scrambled sequences do not reveal any particular dominant patterns when clustered by relative Q. All of the various clusters from both scrambled sequences are all small in comparison to the dominant cluster present in the natural Aβ11−42 polymorph landscape. This wide distribution of ribbon polymorph structures for the scrambled sequences resembles what one finds in folding random sequences in three dimensions. It is also noteworthy that the stabilization energy of the annealed structures, ∼−820 kcal/mol, from both of the scrambled sequences is significantly smaller than the stabilization of the WT peptides, ∼−940 kcal/mol. The diverse and relatively unstable set of structures found during the annealing simulations is consistent with the flat and rugged landscape found for the scrambled sequence using importance sampling, which can be found in Figure 4B.

Figure 6.

Polymorph landscape of a randomized Aβ11−42 polypeptide. (A) Clustered polymorphs for 100 predictions of six randomized Aβ11−42 monomers in a monomer ribbon, using mutual-Q as the measure of structural similarity. One hundred predicted protofilament structures were hierarchically clustered and are shown in a heatmap on the left. The identified clusters are enclosed in black squares on the heatmap, and the representative structures from each cluster are shown and colored from blue (N-terminus) to red (C-terminus) on the right. (B) Potential energy values of 100 predicted structures in the same order as the clustered results shown in panel (A). Note that the potential energies are ∼100 kcal/mol less stable than those from the natural Aβ11−42 ribbon constructs.

These results together suggest that some sort of selection does underlie the polymorph funnel. Some have suggested that amyloid fibrils may usefully sequester peptides that might otherwise form harmful soluble oligomers. This notion would suggest that there would be a survival value favoring facile aggregation. Even more intriguingly, at least one study of mouse and worm models of Alzheimer’s disease has suggested that fibrils of Aβ might act as a defense against microbial infection.41 Nonetheless, the selection underlying the polymorph funnel may, in fact, not be related to any clear functional aspect in vivo at all. Perhaps the selection arises post facto. The randomized sequences have less stable polymorphs than does the natural Aβ sequence. By thus being more soluble, the random sequence, had it ever evolved naturally, would have been less likely to attract our attention by forming aggregates in vivo. The random sequence would not have been “selected” by scientists for study.

Comparing the Polymorph Landscapes of Aβ11−42 with the Landscapes of Full-Length Aβ Peptides, Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42.

In four out of the six experimentally determined Aβ fibril structures shown in Figure 3, with the exceptions of 5OQV and 2M4J, the first 8−10 N-terminal residues are either missing or disordered. The full-length fibril structure of Aβ1−40 has been solved by Tycko et al. in a trimeric form (PDB ID: 2M4J). In the 2M4J structure, there are three copies of Aβ1−40 in each layer of the fibril structure, and the N-terminal residues are apparently stabilized through interactions with other copies of the Aβ molecule in the same layer. Likewise, the N-terminal segment in 5OQV is thought to be stabilized by formation of a salt bridge on the ribbon dimer interface.42 The fact that the stabilization of the N-terminal segment seems to require ribbon dimer contacts to be stabilized suggests that full-length Aβ peptides, which include the first 10 N-terminal residues, may have significantly different polymorph landscapes at the level of ribbon monomers than does the shorter fragment Aβ11−42, which can fold into stable and compact structures as a ribbon monomer, as we have seen above. To investigate the question of how the ribbon polymorph landscapes of full-length Aβ peptides differ from that of Aβ11−42, we computed the polymorph landscapes for Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42 monomer ribbons.

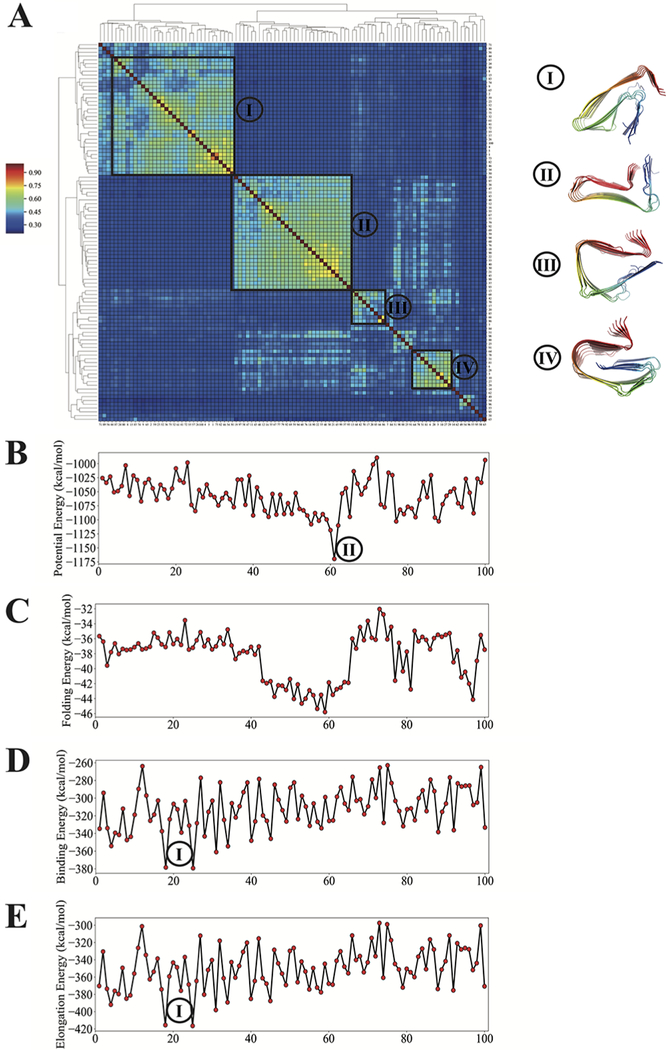

In the case of Aβ1−40, five significant clusters emerge from hierarchical clustering using mutual-Q as a similarity measure in the linkage matrix. It is noteworthy that these clusters are not as tight as those that were identified in the landscape of the shorter peptide, Aβ11−42. The average mutual-Q values within the clusters for Aβ1−40 are around 0.60. The greater spread of structures arises from the fact that N-terminal segments of the longer peptide are not themselves amyloidogenic, and these are sometimes disordered even with ribbon constraints in place (see representative structures from clusters IV and V in Figure 7A). Clusters 1, 2, and 3 are quite similar to each other, with mutual-Q values of around 0.5. In each of these clusters, the C-terminal regions resemble the U-shaped structure sampled from the Aβ11−42 polymorph landscape. The N-terminal segments display more varied orientations than the C-terminal segments, suggesting that the N-terminal region is very flexible, at least when the monomer ribbon is in isolation. Structures from clusters 2 and 3 also manifest the greatest stabilization upon elongation, suggesting the dominance of those polymorphs during fibril growth. Overall, these results suggest that having an ordered N-terminal segment does not contribute to forming a compact ribbon monomer folded structure, consistent with the findings from experiment that these residues are either disordered or stabilized by ribbon oligomer contacts.

Figure 7.

Polymorph landscape of the monomeric Aβ1−40 ribbon. (A) Clustered polymorphs for 100 predictions of six Aβ1−40 peptides in a monomer protofilament, using mutual-Q as the metric for measuring structural similarity. One hundred predicted ribbon structures were hierarchically clustered and are shown in a heatmap on the left. The identified clusters are enclosed in black squares on the heatmap, and the centroid structure from each cluster is shown and colored according to a sequence index from blue (N-terminal) to red (C-terminal) on the right. (B) Potential energy values of 100 predicted structures in the same order as the clustered results shown in panel (A). (C) Energies of folding a Aβ1−40 monomer into a structure that is compatible with the fibril polymorph. (D) Binding energies of folded monomers when bound to pentamer fibrils. (E) Energy gain of elongation by one monomer. The energy values of selected low-energy clusters are labeled by their corresponding cluster indices.

The interplay in vivo between the different length fragments, Aβ1−42 and Aβ1−40, has been a core subject in the discussion about Alzheimer’s disease progression. In order to compare the polymorph landscapes of Aβ1−42 and Aβ1−40, we also simulated the polymorph landscape of the longer fragment Aβ1−42 in a monomer ribbon. Four significant clusters emerge after hierarchical clustering (Figure 8A). Similar to what was seen for Aβ1−40, the N-terminal segment is found to be quite flexible. The polymorph with the greatest elongation stabilization energy of Aβ1−42 turns out to be around ∼−418 kcal/mol, significantly greater than what is found for Aβ1−40 (−378 kcal/mol). The more favorable Aβ1−42 elongation is in line with experimental observations that Aβ1−42 aggregates more quickly at a comparable concentration as well as earlier predictions using AWSEM for the solubilities of Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42. The large variations in elongation stabilization energy inside of each cluster (e.g., Cluster 1 of Aβ1−42) suggest a higher degree of ruggedness to the full-length polymorph landscapes in comparison to the polymorph landscape of Aβ11−42 as a result of the presence of the flexible N-terminal segment.

Figure 8.

Polymorph landscape of the monomeric Aβ1−42 ribbon. (A) Clustered polymorphs for 100 predictions of six Aβ1−42 peptides in a monomer protofilament, using mutual-Q as the metric for measuring structural similarity. One hundred predicted ribbon structures were hierarchically clustered and are shown in a heatmap on the left. The identified clusters are enclosed in black squares on the heatmap, and the centroid structure from each cluster is shown and colored according to a sequence index from blue (N-terminal) to red (C-terminal) on the right. (B) Potential energy values of 100 predicted structures in the same order as the clustered results shown in panel (A). (C) Energies of folding a Aβ1−42 monomer into a structure that is compatible with the fibril polymorph. (D) Binding energies of folded monomers when bound to pentamer fibrils. (E) Energy gain of elongation by one monomer. The energy values of selected low-energy clusters are labeled by their corresponding cluster indices.

Predicted Polymorph Landscape for Dimeric Aβ11−42 Ribbons.

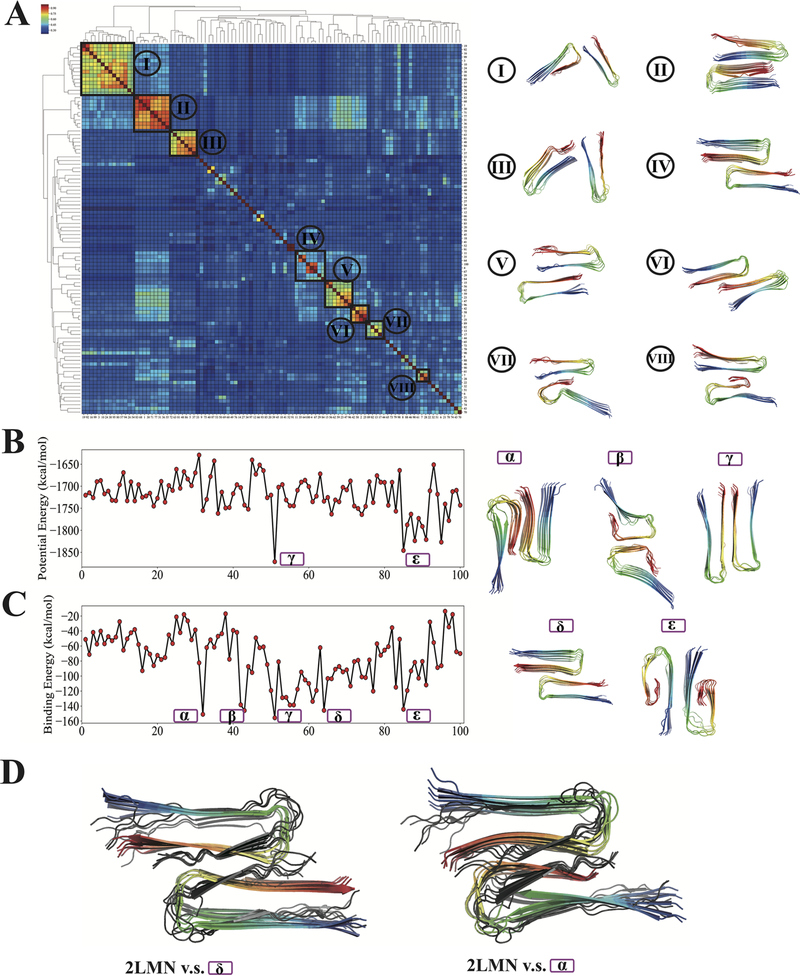

Several fundamental aspects of fibrillar polymorphism are already apparent in the ribbon monomer simulations of Aβ11−42, Aβ1−40, and Aβ1−42. The polymorph landscapes of monomeric ribbons are rugged but do have something of a funneled nature, which probably has been shaped by selection of some sort. A further source of protofibril polymorph complexity arises through the various association possibilities of monomeric ribbons within the plane.43 To visualize the polymorphism of oligomeric ribbons, we studied the polymorph landscape for dimeric Aβ11−42 ribbons. Eight small clusters emerge after hierarchical clustering of the 100 predictions. As shown in Figure 9A, most of the monomers from these representative structures still manifest the characteristic U-shaped structure seen in the monomeric ribbon, and one also finds inverted S-shaped monomers (e.g., Cluster 8). Most of the clusters, including Clusters 1, 2, and 3, are energetically unfavorable compared to the one that we found to have the lowest energy (structure γ in Figure 9B,C). Visualization of the centroid structures of these clusters reveals that most of the centroid structures lack symmetry at the level of the dimer, except for the centroid structure of Cluster 4. In keeping with general arguments about the origin of biomolecular symmetry,44 all known experimentally determined Aβ fibril structures exhibit symmetry at the level of ribbon oligomers. Although most of the structures found in the clusters are not symmetric, here we do find that the most energetically favorable structures are indeed all symmetric. In particular, we find that strong binding energies invariably signal a high degree of symmetry of the binding interface. These structures either exhibit a rotational symmetry (structures α, β, δ, and ϵ) or have a mirror symmetry (structure γ). The structures with rotational symmetry resemble the experimentally solved Aβ fibrils that have two-fold symmetry (PDB ID: 2LMN, gray in Figure 9D). Structures α and δ have RMSD values of around 4 Å with respect to 2LMN. In four out of the five symmetric structures, the monomers make contacts between their C-termini, which are more hydrophobic. Structure ϵ displays an association pattern through the less hydrophobic N-terminal segments. Although the corresponding observations from experiments are still limited, the agreement with the experimental structure 2LMN suggests a reasonable likelihood that the other polymorphs seen here may also exist.

Figure 9.

Polymorph landscape of the dimeric Aβ11−42 ribbons. (A) Clustered polymorphs for 100 predictions of 12 Aβ11−42 peptides in two protofilaments, using mutual-Q as the metric for measuring structural similarity. One hundred predicted ribbon structures were hierarchically clustered and are shown in a heatmap on the left. The identified clusters are enclosed in black squares on the heatmap, and the centroid structure from each cluster is shown and colored according to a sequence index from blue (N-terminal) to red (C-terminal) on the right. (B) Potential energy values of 100 predicted structures in the same order as the clustered results shown in panel (A). (C) Binding energies of ribbon dimers. Selected symmetric structures are shown with Greek letters as identifiers. The energy values of selected low-energy symmetric structures are labeled by their corresponding structure identifiers. (D) Structural comparisons of an experimentally determined structure (2LMN) with predicted structures α and δ. The experimentally determined model 2LMN is colored in gray, while the predicted structures are colored from blue (N-terminal) to red (C-terminal).

We also carried out similar calculations for the association of three Aβ11−42 ribbon monomers in the plane. Seven clusters of structures were identified from hierarchical clustering, and these seven clusters contain around 40% of the 100 predictions (Figure S2). No structure with an exact three-fold symmetry showed up in the prediction runs. The issue of the size of the sampling space, however, plagues the study of these larger protein−protein associations and will become still more serious when the number of monomers in each plane builds up.

DISCUSSION

Ribbon-Folding Simulations and Energy Landscape Analyses Together Provide a Useful Framework for Predicting and Characterizing Amyloid Polymorphism Landscapes in Silico.

Many proteins are known to form amyloid fibrils above a critical concentration that depends on both the sequence of the aggregating polypeptide and the solvent conditions. Only a handful of amyloid fiber structures, however, have been determined by experimentalists in detail. Detailed determination of protein fibril structures is, in many ways, substantially more difficult than the determination of globular protein structures. While there are now theoretical tools for reliably generating high-quality structural models for globular proteins from sequence, corresponding theoretical tools in the area of amyloids have mostly been limited to identifying those short peptides that are responsible for driving amyloid formation.29,45–48 By viewing the problem of predicting the structures of stable amyloid polymorphs as a two-dimensional protein ribbon-folding problem, we have developed a practical algorithm that can, in principle, predict the most stable amyloid folds of any sequence. In this paper, we have tested the method on variants of the Aβ sequence and have found good agreement with what is known experimentally about Aβ fibrillar aggregation. We are currently testing the idea for several other systems, such as the Tau and FUS proteins, where there are fewer experimental data for comparison. The study of the Aβ peptides already has yielded some insights into its polymorphism. Aβ11−42 exhibits polymorphism in which the most stable monomeric protofilament structures adopt either U-shaped or S-shaped configurations. The N-terminal segment of the full-length Aβ sequences, Aβ1−40 and Aβ1−42, cannot be stably accommodated in the fold of the monomeric Aβ ribbon. This fact about the ribbon monomer landscape explains why the N-terminal segment is found to be either disordered or stabilized by oligomeric contacts in its known experimental structures. Simulations of oligomeric ribbons show that the most stable associations between ribbon monomers arise by forming symmetric interfaces between again similarly folded ribbon monomers. This fact is consistent with the nearly universal symmetric nature of fibril structures found for Aβ by both high-and low-resolution experimental structure determination methods. While detailed experimental characterization of the structure of amyloid folds is by itself challenging, directly probing the energetics of amyloid folds is more challenging still. By assuming that the same types of physicochemical forces that guide globular protein folding also describe the amyloid polymorph energetic landscape, we have found, somewhat to our surprise, that the ribbon-folding landscape of monomeric Aβ11−42 exhibits a significant degree of funneling. Scrambled versions of Aβ11−42, in contrast, exhibit much more rugged landscapes. Ribbons made up of these scrambled peptides apparently cannot fold into conformations that are as stable as those found for the ribbons composed of the natural Aβ11−42 sequence. Amyloid fibers made up of such scrambled peptides thus would be more soluble than the fibers formed by the natural Aβ sequence. While it is possible that the partially funneled nature of Aβ’s ribbon landscape and the corresponding low solubility are evolved characteristics that serve some biological function, it would seem at least as likely that these characteristics are the result of a post facto selection of Aβ for study by researchers: without Aβ’s ability to form aggregates at concentrations found in vivo, caused by its funneled landscape, these aggregates would not have attracted much attention.

We caution that ribbon-folding simulations are not intended to provide a realistic kinetic description of the formation of amyloid fibers. Once stable amyloid polymorphs have been predicted using the ribbon-folding algorithm, however, we can use importance sampling without having the ribbon constraints in place to investigate both the solubility and the structural mechanism of formation of the predicted polymorphs, as we have done previously using experimentally determined fiber structures as input.27,28 Detailed calculations of solubilities that involve following aggregation pathways toward several predicted polymorphs of Aβ11−42 suggest that elongation energies, which are easy to calculate given the predicted protofibril structure, correlate with the predicted solubilities. Together, the ribbon-folding algorithm and the detailed solubility calculations can be used to probe the structure and energetics of the most favorable amyloid folds of arbitrary sequences as well as to examine their structural mechanisms of formation.

Limitations and Extensions of the Current Ribbon-Folding Scheme.

There are several limitations of the ribbon-folding algorithm presented here that are worth noting. The current version of the algorithm assumes that the most stable amyloid polymorphs will be based on parallel in-register β-sheets. This assumption is consistent with the majority of amyloid fibril structures that have been determined so far by experiment in detail. Although crystal structures of amyloid fibers with parallel out-of-register β-strands have been observed, these are for very short peptides (∼6 residues).49 The out-of-register parallel β-sheet does not appear to be favorable for longer peptides that form amyloid fibers. Tycko and co-workers have presented the structure of a metastable antiparallel Aβ fibril structure formed by Aβ molecules containing the disease-causing “Iowa” mutation.10 This antiparallel form, however, eventually converts to a parallel fibril structure, which therefore must be lower in free energy. Developing a ribbon-folding algorithm for presumed anti-parallel β-sheets is certainly possible but would be complicated by the fact that one must search through many possible antiparallel registrations while the in-register association through self-recognition is generally the most favorable for the parallel arrangement.

In addition to the assumption of parallelism, the algorithm described here assumes that each polypeptide chain primarily occupies a single xy-plane, with the z-axis being parallel to the fibril axis. Most experimental structures at least approximately satisfy this constraint, but there are several notable exceptions: the Aβ9−40 fibril structures 2LMN and 2LMQ have positive and negative staggers, meaning that the N-terminal and C-terminal halves of each individual polypeptide occupy different xy-planes. To predict with greater fidelity such structures using the present ribbon-folding code, either the degree of stagger would need to be known and incorporated into ribbon constraints or multiple guesses of the stagger could be tried to see which (discrete) value yielded the most stable structures. We again note, however, that the presently predicted arrangement of the β-strands in the plane is similar to 2LMN and 2LMQ even though no stagger was incorporated in the constraints. In this sense, the experimental structures can be thought of as “runaway domain-swapped”50 versions of the monomeric U-shaped structures predicted when using the ribbon constraints. It is interesting, but beyond the scope of the current study, to consider why such domain-swapped structures should be found rather than only the seemingly simpler arrangements with a single molecule per z-plane. We do note, however, that such domain-swapped structures are not unprecedented. Domain-swapped structures are stabilized by strong native-like contacts in globular proteins and thus show up on occasion in X-ray determinations there as well. Because the loop region in the protofilament structure makes a relatively small contribution to the total energy and, owing to the domain swap, the interactions between the β-strands remain the same in the structures with and without stagger, then long filaments with staggered and unstaggered associations would indeed be nearly energetically degenerate. While these structures would therefore have similar solubilities, structures exhibiting a stagger might still be favored by some aspect of the kinetic mechanism of fibril formation. Obviously there would be significant energy costs to incorporating both types of pairing in the same fibril. This suggests a mechanism for a very strong “species barrier”.

Another more subtle violation of the one-molecule-per-plane assumption is associated with structures of amyloid fibers that exhibit a significant degree of twist along their fiber axes. The harmonic ribbon constraints as implemented in this work already do allow for the formation of such twisted structures, e.g., the structures in Cluster 7 on the Aβ11−42 polymorph landscape (see Figure 2), but further investigations of the twist energetics are certainly warranted.

Finally, experimentally determined structures of mature Aβ fibrils typically contain more than one protofilamentary stack, indicating that the lateral association of protofilaments probably contributes to the stability of these structures. Without imposing a symmetry constraint, the current ribbon-folding algorithm mostly samples asymmetric structures that contain differently folded protofilaments. Imposition of symmetry constraints during ribbon folding may help to overcome the problem of sampling the very large space of protofilament folding and association.

Higher Length Scale Polymorphism.

It is known that a given protein sequence can form amyloid fibers with different degrees of twist while still having very similar structures at the protofilament level.51 We see that this is possible because even the ordered amyloid basin is quite broad and can accommodate structurally similar substates.52 Some of these different substates can be assembled going along the fiber in a variety of orders, and these differences can be accommodated by twist and perhaps be stabilized by interactions between protofilaments. Twist is apparently a source of gross polymorphism that is separable from the polymorphism seen at the ribbon fold level for protofilaments. Polymorphism on longer length scales is an interesting problem in statistical physics involving frustration between local tendencies to form helices with certain periodicities and mismatches of the interactions between the resulting noncrystallographic helices.53

Many interesting problems come to the fore in under-standing the higher length scale polymorphism of amyloid fibrils. These issues are important especially when amyloids are prepared under great stress.54–59 Forming amyloids out of the peptides that are the product of hydrolyzing either β-lactoglobulin or lysozyme can give rise to large multistranded fibrils despite the fact that or, perhaps, because the proteins are not covalently intact.54,55,57 The degree of twist of the resulting fibrils has been shown to depend on the ionic strength,56 and further quantification of the factors that contribute to determining the twist periodicity showed that a balance between elastic and electrostatic contributions can explain the observed periodicities.57 More recently, a series of three homologous hexapeptides were used to form amyloid fibrils, and it was shown that twisted amyloid fibrils formed from these peptides gradually convert into flat amyloid crystal structures.58

We see that by exploiting the relatively controlled diversity of substates in the monomer ribbon landscape, allowing domain swapping (i.e., stagger) along with twist and interaction between protofilaments in larger filamentary assemblies, the space of possible polymorphisms of complete fibrils is astoundingly large. The situation is much like that in music where by working out many lines in parallel, each based on a simple theme undergoing numerous transformations, obeying harmonious interactions between the voices, an enormous range of compositions is possible.60 Does the diversity of long length scales matter in physiology? Obviously, at short lengths, there can be significant energetic differences between the polymorphs, giving them different solubilities, as we have seen. Also, domain swapping/stagger clearly would give kinetic barriers between species. It would seem that primarily at large length scales polymorphism would be manifested most strongly in the mechanical properties of the fibers and thus may influence secondary nucleation caused by fragmentation19 and thereby possibly the course of disease progression.

CONCLUSIONS

Debates over whether amyloid fibers are directly toxic to cells or only indirectly toxic, as well as debates concerning the countervailing idea that fibers provide protection to cells by sequestering monomers from forming toxic soluble oligomers, still rage.61–63 There is, however, mounting evidence for prion-like spreading of protein aggregates within the brain, which suggests a connection between amyloid fiber polymorphism and rates of disease progression in neurodegenerative disorders.64–70 Theoretical methods for modeling the globular protein structure have greatly expanded the range of questions that can be addressed by structural biologists. Likewise, we hope that the ribbon-folding algorithm and the associated energy landscape analyses will be useful in accelerating our understanding of the amyloid polymorph landscape in a wide range of contexts in medicine and cell biology.71,72

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Grant R01 GM44557 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences. Additional support was also provided by the D.R. Bullard-Welch Chair at Rice University, Grant C-0016. We thank the Data Analysis and Visualization Cyberinfrastructure funded by National Science Foundation Grant OCI-0959097. One of us, P.G.W., remembers with great fondness his time in the Laboratory of Chemical Physics at NIH more than 2 decades ago as well as his interactions there when he was a Fogarty Scholar-in-Residence, at which time his interest in the prion species problem was kindled.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.jpcb.8b07364.

Fibril polymorphism of amyloid-β11−42 trimeric ribbon, fibril polymorphism of scrambled amyloid-β11−42 polypeptides, and contact maps of experimentally determined Aβ fibril structures exhibiting stagger and several centroid structures of Aβ11−42 predicted polymorphs (PDF, ZIP)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Schrodinger E; Penrose R What is Life?: With Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Spirig T; Ovchinnikova O; Vagt T; Glockshuber R Direct evidence for self-propagation of different amyloid-β fibril conformations. Neurodegener. Dis 2014, 14, 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Orgel LE Prion replication and secondary nucleation. Chem. Biol 1996, 3, 413–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Hofrichter J; Ross PD; Eaton WA Kinetics and Mechanism of Deoxyhemoglobin S Gelation: A New Approach to Understanding Sickle Cell Disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 1974, 71, 4864–4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]