Abstract

The inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) has pharmaceutical applications as well as potential neurotoxic effects. The in vivo metabolites of some chemicals including organophosphorus pesticides can become more potent AChE inhibitors compared to their parental compounds. To account for the effects of biotransformation, we have developed and characterized a high-throughput screening method for identifying AChE inhibitors that become active or more potent following xenobiotic metabolism. In this study, an enzyme-based assay was developed in 1536-well plates using recombinant human AChE combined with human or rat liver microsomes. The AChE activity was measured by two methods with different readouts: colorimetric and fluorescent. The assay exhibited exceptional performance characteristics including large assay signal window, low well-to-well variability and high reproducibility. The performance of the assays with microsomes was characterized by testing a group of known AChE inhibitors including parent compounds and their metabolites. Large potency differences between the parent compounds and the metabolites were observed in the assay with microsome addition. Both assay readouts were required for maximal sensitivity. These results demonstrate that this platform is a promising method to profile large numbers of chemicals that require metabolic activation for inhibiting AChE activity.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase (AChE), liver microsomes, metabolic activation, organophosphorus, quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS)

INTRODUCTION

Acetylcholinesterase (AChE), located at the neuromuscular junctions and cholinergic nerve synapses, terminates neurotransmission at cholinergic synapses by catalyzing the breakdown of acetylcholine (ACh) into choline (Massoulie et al., 1993). Such activity is exploited for pesticidal activity against a wide range of insects as well as in human therapeutic applications and chemical warfare agents. Inhibition of AChE activity leads to cholinergic poisoning including vomiting, diarrhea, muscle fasciculation and even flaccid paralysis (McHardy et al., 2017). Many compounds including synthesized drug candidates, food additives, and industrial chemicals have not been thoroughly evaluated for effects on AChE activity. Moreover, some of the chemicals may need metabolic activation to show inhibitory effects. Therefore, there is a need to develop in vitro, high-throughput methods with xenobiotic metabolism capability for identifying AChE inhibitors, which can prioritize compounds for subsequent toxicological study.

One class of chemicals of public health concern are the organophosphorus pesticides (OPs) due to their worldwide use in agriculture (Jaga and Dharmani, 2006; Farahat et al., 2011). OPs exert pesticidal activity by inhibiting AChE acitivity. Some OPs are not active AChE inhibitors in their parent form and require bioactivation in order to be effective AChE inhibitors (Sultatos, 1994). A variety of OPs has been shown to be bioactivated by cytochromes P450 (Buratti et al., 2003; Sams et al., 2004; Foxenberg et al., 2007). The cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily is composed of 57 genes and regarded as the most important class of enzyme systems responsible for the metabolism of a diverse array of endogenous and exogenous compounds (Martiny and Miteva, 2013; Zanger and Schwab, 2013). For example, the OP diazinon is activated by human hepatic CYP2C19 (Kappers et al., 2001), while another OP parathion is activated primarily by CYP3A4/5 and CYP2C8 (Buratti et al., 2003). Chlorpyrifos (CPS) can be activated by CYP2B6 to produce the active metabolite chlorpyrifos oxon (CPO) (Tang et al., 2001; Dai et al., 2001).

In vitro screening assays with metabolic capability are used to estimate the human drug metabolic fates in vivo (Li, 2001; Li, 2004). There are a number of methods for providing xenobiotic metabolism in vitro, such as perfused liver, liver slices, primary hepatocytes, liver cytosol, S9 fractions, supersomes (recombinant enzymes expressed in an insect cell system), human colon cancer derived cell line (Caco-2), and microsomes (Zhang et al., 2012; Tingle and Helsby, 2006; Asha and Vidyavathi, 2010). Microsomes are rich in cytochrome P450s, flavin monooxygenases, carboxyl esterases, epoxide hydrolase, and uridine 5′-diphospho-glucuronosyltransferase (UDP-glucuronyltransferases, UGT), and can be prepared from microsomal vesicles of liver slices, liver cell lines, and primary hepatocytes (Ekins et al., 2000; Reed and Backes, 2012; Fujiki et al., 1982). Human liver microsomes represent a popular in vitro model for their reproducibility, capacity for long-term storage, and extensive characterization of optimal incubation conditions (Asha and Vidyavathi, 2010; Zhang et al., 2015). Generally in vitro metabolic activity of CYP is expressed per mg of microsomal protein. Microsomes are often pooled from multiple donors to avoid inter-individual variation (Zhang et al., 2015; Araya and Wikvall, 1999). Alternatively, rat liver microsomes from animals treated with the polychlorinated biphenyl arochlor show highly induced xenobiotic metabolism and are routinely used for studying drug metabolism. While species differences exist, the robust metabolic capacity is considered a useful attribute.

In the present study, we developed a high-throughput AChE assay with in vitro metabolism using human or rat liver microsomes. To validate the assay, a group of OP compounds containing both parental compounds and active metabolites were tested. The assay utilized recombinant human AChE protein and human or rat liver microsomes, and the Ellman colorimetric or fluorescent method were used to measure AChE activity. The assay reproducibility was evaluated and compounds were ranked by their potency. Together, these data demonstrated that the AChE assay with metabolism capability is promising for profiling AChE inhibitors for further study that will be vital for chemical safety assessment.

MATERIALS and METHODS

Reagents

Twenty-six AChE inhibitors (Table 1) were selected from the Tox21 10 K library. Amplite™ Colorimetric Acetylcholinesterase Assay kit (Ellman assay) and Amplite™ Fluorimetric Acetylcholinesterase Assay kit (Green Fluorescence) were purchased from AAT Bioquest, Inc. (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Chlorpyrifos-oxon was purchased from Chem Service, Inc. (West Chester, PA, USA). Chlorpyrifos (CAS#: 2921–88-2), BW284c51, β-Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide 2′-phosphate (NADPH), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and purified recombinant human AChE protein were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). InVitroCYP™ 150-D human liver microsomes (HLM), prepared from 150 donor human liver tissue fraction pools with mixed gender, were purchased from BIOIVT (Baltimore, MD, USA). Acroclor 1254-induced male Sprague-Dawley rat liver microsomes (RLM) were purchased from Molecular Toxicology Inc. (Boone, NC, USA).

Table 1.

Potency and efficacy values of the compounds in AChE assays.

| Sample Name | Parent or oxon | CASRN | Analytical QC grade | IC50 (μM), efficacy (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric | Fluorescence | ||||

| Diazoxon | Oxon | 962–58–3 | A | 1.33 ± 0.15 (−95.23 ± 1.27) | 0.50 ± 0.10 (−77.68 ± 3.77) |

| Profenofos | Oxon | 41198–08–7 | Ac | 12.15 ± 2.59 (−83.18 ± 2.51) | 1.89 ± 0.00 (−93.71 ± 2.58) |

| Dichlorvos | Oxon | 62–73–7 | D | 31.16 ± 2.85 (−34.90 ± 18.79) | 18.94 ± 2.18 (−76.75 ± 7.46) |

| Diazinon | Parent | 333–41–5 | A | 37.99 ± 3.32 (−102.16 ± 3.10) | 30.10 ± 7.52 (−96.32 ± 10.13) |

| Naled | Oxon | 300–76–5 | D | 61.32 ± 4.47 (−46.54 ± 10.72) | Inactive |

| Ethoprop | Oxon | 13194–48–4 | Z | 61.62 ± 9.39 (−43.42 ± 16.97) | 16.57 ± 1.12 (−97.79 ± 1.82) |

| Tebupirimfos | Parent | 96182–53–5 | A | 63.81 ± 5.83 (−52.97 ± 14.85) | 21.71 ± 0.00 (−90.42 ± 4.12) |

| Dicrotophos | Oxon | 141–66–2 | A | 66.84 ± 7.74 (−32.45 ± 17.59) | 23.61 ± 1.54 (−82.68 ± 1.92) |

| Trichlorfon | Oxon | 52–68–6 | A | 67.55 ± 5.91 (−30.02 ± 12.96) | 41.93 ± 5.77 (−91.50 ± 1.15) |

| Chlorethoxyfos | Parent | 54593–83–8 | A | 70.04 ± 3.42 (−46.27 ± 7.72) | 37.20 ± 2.42 (−99.25 ± 3.99) |

| Methamidophos | Oxon | 10265–92–6 | A | 72.84 ± 4.59 (−38.74 ± 7.88) | 43.50 ± 5.00 (−102.92 ± 5.19) |

| Malaoxon | Oxon | 1634–78-2 | A | 8.84 ± 3.71 (−91.09 ± 4.14) | 1.01 ± 0.07 (−95.22 ± 1.05) |

| Coumaphos | Parent | 56–72–4 | A | Inactive | 31.06 ± 5.80 (−83.34 ± 9.14) |

| Omethoate | Oxon | 1113–02-6 | A | Inactive | 68.95 ± 7.93 (−46.31 ± 7.03) |

| Z-Tetrachlorvinphos | Oxon | 22248–79–9 | A | Inactive | 45.07 ± 3.05 (−75.68 ± 1.17) |

| Chlorpyrifos | Parent | 2921–88-2 | A | Inactive | 40.17 ± 2.72 (−100.41 ± 4.09) |

| Malathion | Parent | 121–75–5 | A | Inactive | 54.53 ± 0.00 (−76.98 ± 2.92) |

| Phosmet | Parent | 732–11–6 | A | Inactive | 61.18 ± 0.00 (−65.27 ± 2.96) |

| Acephat | Oxon | 30560–19–1 | A | Inactive | Inactive |

| Bensulide | Parent | 741–58–2 | A | Inactive | 52.55 ± 3.42 (−34.09 ± 4.28) |

| Dimethoate | Parent | 60–51–5 | A | Inactive | Inactive |

| Fosthiazate | Oxon | 98886–44–3 | A | Inactive | Inactive |

| Phorate | Parent | 298–02–2 | A | Inactive | 61.18 ± 0.00 (−44.37 ± 5.38) |

| Pirimiphos-methyl | Parent | 29232–93–7 | A | Inactive | Inactive |

| Terbufos | Parent | 13071–79–9 | A | Inactive | Inactive |

| Tribufos | Oxon | 78–48–8 | A | Inactive | 35.80 ± 2.42 (−60.75 ± 0.97) |

Note: CASRN, Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number; IC50, concentration of half-maximal inhibition; each value of potency (IC50, μM) and efficacy (% of positive control, expressed in parentheses) is the mean ± SD of the results from three experiments. Purity Rating: A = MW Confirmed, Purity >90%; Ac = MW Confirmed, Purity >90%, Low concentration of sample; D = MW Confirmed, Purity <50%; Z = MW Confirmed, No Purity information

AChE assays

Colorimetric readout

AChE activity was measured using a modified, colorimetric acetylcholinesterase assay kit. Recombinant human AChE (50 mU/mL) was dispensed at 4 μL per well into black-clear bottom 1536- well plates (Greiner Bio-One North America, Monroe, NC) using a Multidrop Combi 8-channel dispenser (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Test compounds or controls (23 nL) were transferred into the assay plates using a Wako Pintool station (Wako Automation, San Diego, CA, USA) and the assay plates were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Next, 4 μL of colorimetric detection cocktail solution (DTNB, acetylthiocholine) was added to each well (final concentration of AChE was 25 mU/mL) using a Flying Reagent Dispenser (Aurora Discovery, Carlsbad, CA). Assay plates were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, followed by measuring absorbance (ex = 405 nm) using Envision plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Fluorescent readout

Recombinant human AChE (20 mU/mL) was dispensed at 4 μL per well into 1536-well black wall/solid bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One North America, Monroe, NC) using a Multidrop Combi (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Test compounds or controls (23 nL) were transferred into the assay plates using a Wako Pintool station (Wako Automation, San Diego, CA, USA) and the assay plates were incubated for 30 min at room temperature. Next, 4 μL of fluorescent detection cocktail solution (Thiolite™ Green, acetylthiocholine) was added to each well (final concentration of AChE was 10 mU/mL) using a Flying Reagent Dispenser (Aurora Discovery, Carlsbad, CA). Fluorescence intensity was measured at 490 nm excitation and 520 nm emission by an EnVision plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

AChE assays with microsome addition

Colorimetric readout

The mixture of hAChE (50 mU/mL) and human or rat liver microsomes (0.25 mg/mL, final concentration) was dispensed at 3 μL/well in 1536-well blackclear-bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One North America, Monroe, NC) using a Multidrop Combi (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). Next, 23 nL of compound dissolved in DMSO, positive control (chlorpyifos) or negative control (DMSO) was added to the assay plates via Wako Pintool station (Wako Automation, San Diego, CA). Following compound addition, 1 μL of NADPH at final concentration of 0.25 mg/mL was transferred to the assay plate by a Flying Reagent Dispenser (Aurora Discovery, Carlsbad, CA). After 30 min incubation at 37 °C, 4 μL of colorimetric detection cocktail solution (DTNB, acetylthiocholine) was added to each well and the plates were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min. Absorbance intensity was measured at 405 nm by a PHERAstar plate reader (BMG LABTECH, Cary, NC, USA).

Fluorescent readout

The mixture of hAChE (20 mU/mL) and human or rat liver microsomes (0.25 mg/mL) was dispensed at 3 μL per well in 1536-well blacksolid-bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One North America, Monroe, NC) using a Multidrop Combi (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA). 23 nL of compound and controls were added to the assay plates via pintool (Kalypsys, San Diego, CA). Following compound addition, 1 μL of NADPH at final concentration (0.25 mg/mL) were transferred to the assay plate by a Flying Reagent Dispenser (Aurora Discovery, Carlsbad, CA). After 30 min incubation at 37 °C, 4 μL of fluorescent detection cocktail solution (Thiolite Green, acetylthiocholine) was added to each well and the plates were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 20 min. Fluorescence intensity was measured at 490 nm excitation and 520 nm emission by an EnVsion plate reader (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA).

Data Analysis

Analysis of compound concentration-response data was performed as previously described (Huang, 2016). Briefly, raw plate measurements for each titration point were first normalized relative to the positive control compound (chlorpyrifos oxon for assays without microsomes and chlorpyrifos for assays with microsomes; −100%) and DMSO-only wells (0%) as follows: Activity (%) = ([Vcompound − VDMSO]/[VDMSO − Vpos]) × 100, where Vcompound denotes the compound well values, Vpos denotes the median value of the positive control wells, and VDMSO denotes the median values of the DMSO-only wells. The data set was then corrected using an in-house pattern correction algorithm (Wang and Huang, 2016). The half-maximum inhibitory values (IC50) for each compound and maximum response (efficacy) values were obtained by fitting the concentration-response curves of each compound to a four-parameter Hill equation (Wang et al., 2010). Compounds with efficacy <30% were considered as inactive compounds. The analytical QC information for the compounds in the current study is listed in Table 1. Each value of potency and efficacy is the mean ± SD of the results from three experiments. Data were further analyzed and depicted using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Development of human AChE assay in a 1536-well plate format

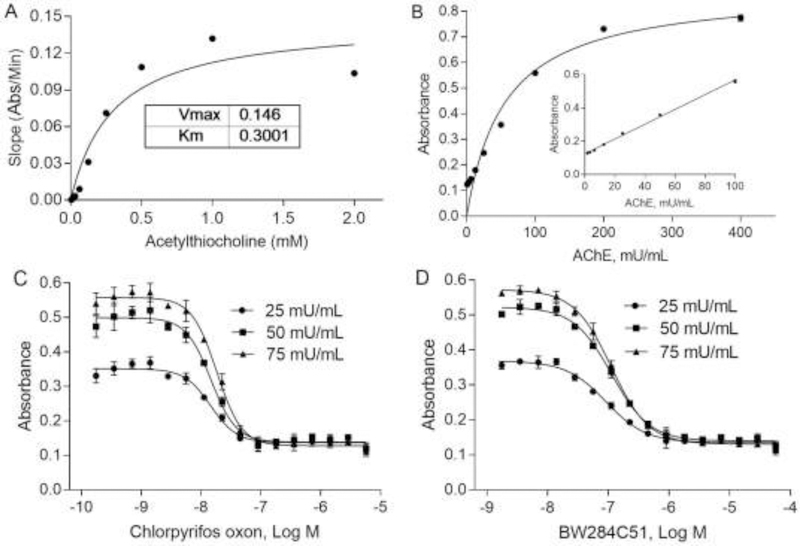

Human AChE activity was measured using colorimetric and fluorimetric-based AChE methods. To optimize the concentration of the substrate, acetylthiocholine, for the colorimetric assay, nine concentrations ranging from 0.04 to 10.5 mM were incubated with AChE (20 mU/mL) at varying time points from 0 to 30 min. The assay reaction slope was calculated by the equation (Slope = ΔY/ΔX) using linear regression. The calculated slopes for the reaction progress curves were plotted on the Y-axis versus the various concentration of substrate (X-axis). Then, a rectangular hyperbola model was used for nonlinear regression analysis (Fig. 1A) with Km of 0.3 mM. Based on the Km value, the substrate (acetythiocholine) concentration at 0.15 mM was selected for the assay. The assay showed a linear response with the enzyme concentrations from 1.56 to 100 mU/mL (Fig. 1B). Three enzyme concentrations (25 mU/mL, 50 mU/mL, or 75 mU/mL) with 0.15 mM substrate were further evaluated for assay performance using two positive controls, chlorpyrifos oxon and BW284c51. The IC50s of chlorpyrifos oxon on AChE inhibition are 13.77 ± 3.61 nM, 14.67 ± 2.98 nM and 18.29 ± 2.85 nM at 25, 50, and 75 mU/mL of AChE, respectively, while the IC50s of BW284c51on AChE inhibition are 91.5 ± 24.13 nM, 113.2 ± 17.18 nM and 112.2 ± 12.52 nM, at 25, 50, and 75 mU/mL of AChE, respectively (Fig. 1C, D). The signal to background ratios were 3.26, 4.42, and 4.89 fold at 25, 50, and 75 mU/mL of AChE used in the assay. Based on the IC50s and S/B ratios, 50 mU/mL of AChE was chosen in the subsequence assays. Fifty mU/mL AChE and 0.15 mM substrate were selected for colorimetric assay, and the reactions were linear with respect to time.

Fig. 1.

Optimization of human AChE assays. Vmax and Km were determined for acetylthiocholine (A) as well as enzyme concentration (B). There were dose-dependent inhibition curves using different AChE concentrations in 1536-well plates treated with chlorpyrifos oxon (C) and BW284C51 (D). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

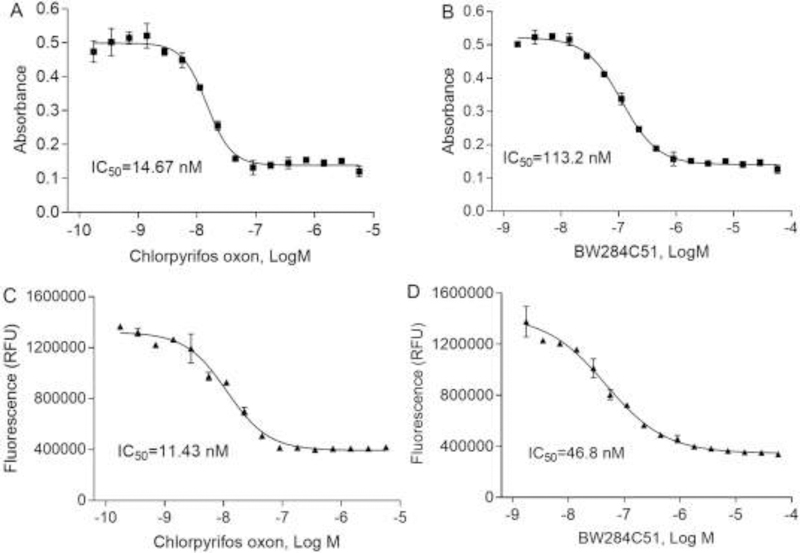

The substrate concentrations ranging from 0.2 to 50 μM were also optimized in the fluorescent method, with calculated Km of 0.98 μM. One μM of the substrate and 20 mU/mL AChE were used for fluorescent AChE assay. There were dose-response curves in response to chlorpyrifos oxon and BW284c51 treatment using both the colorimetric method (Fig. 2A, B) and the fluorescent method (Fig. 2C, D). The colorimetric assay substrate showed good assay performances with coefficient of variation (CV, %), signal-to-background ratio (S/B) and Z’ factor of 2.00 ± 0.01, 4.84 ± 0.04 and 0.84 ± 0.01, respectively. The fluorescent assay using 20 mU/mL AChE and 1 μM substrate showed assay performances with coefficient of variation (CV, %), signal-to-background ratio (S/B) and Z’ factor of 5.00 ± 0.01, 3.74 ± 0.36 and 0.76 ± 0.01. The reaction was linear with respect to time.

Fig. 2.

Concentration-response curves of human AChE assays. There were concentration-dependent inhibition curves in 1536-well plates treated with two positive controls, chlorpyrifos oxon and BW284C5. Two methods were used to measure AChE activity including colorimetric (A, B) and fluorescent methods (C, D). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

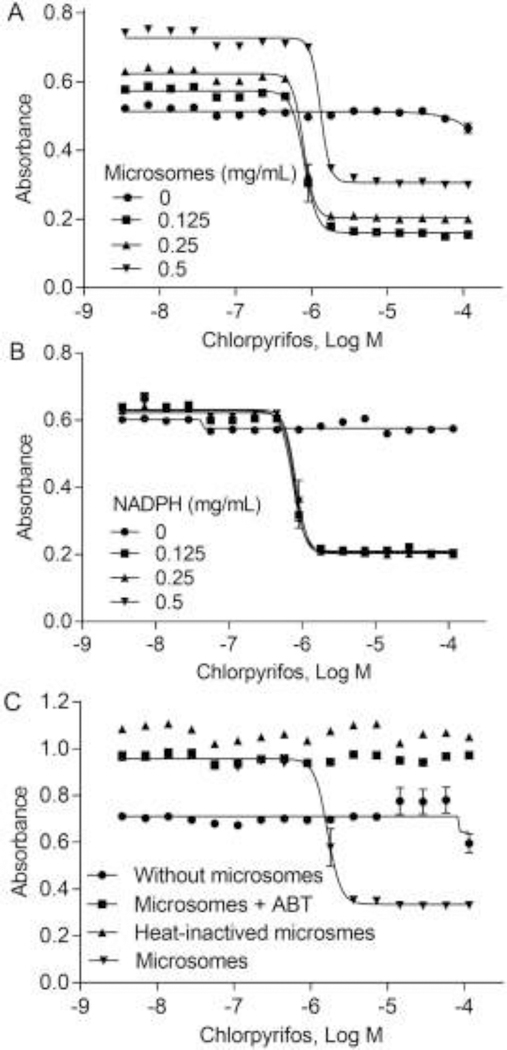

Optimization of human AChE assay in the presence of microsomes

The AChE assay in the presence of human liver microsomes was further optimized. The test compounds were incubated with AChE and liver microsomes first and then NADPH-generating system was added to initiate the reaction at 37 °C. With addition of three different microsome concentrations (0.125 mg/mL, 0.25 mg/mL, 0.5 mg/mL) chlorpyrifos, an OP requiring bioactivation, showed concentration-dependent inhibition of AChE with IC50s of 1.31 μM, 0.78 μM, and 0.80 μM at 0.125 mg/mL, 0.25 mg/mL, 0.5 mg/mL of the microsomes, respectively (Fig. 3A). NADPH was also optimized at the concentrations of 0.125 mg/mL, 0.25 mg/mL, and 0.5 mg/mL. We found that different NADPH concentrations did not change chlorpyrifos concentration-response curves (Fig. 3B). When the AChE assay was treated with heat-inactivated microsomes or the CYP inhibitor (1-aminobenzotriazole, ABT) or without microsome addition, chlorpyrifos did not inhibit AChE activity, demonstrating that chlorpyrifos needs to be metabolized to chlorpyrifos oxon (the active inhibitor) (Fig. 3C). The optimal concentration for the AChE assay with in vitro metabolism was 0.25 mg/mL microsome and 0.25 mg/mL NADPH. The enzyme assay with human microsome (n = 72) showed good assay performances with coefficient of variation (CV), signal-to-background ratio (S/B) and Z’ factor of 2.03 ± 0.05, 3.29 ± 0.01 and 0.85 ± 0.02, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Optimization of AChE assay with human liver microsome addition. Various concentrations of (A) microsomes and (B) NADPH were tested in AChE assay; (C) Chlorpyrifosdose-dependently inhibited AChE activity, but there were no inhibitory effects in AChE activity when treated with heat-inactivated microsomes, CYP inhibitor, or without microsomes (ABT). Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

Performance of human AChE assay using a group of common OP compounds

To characterize the AChE assay, 26 OP pesticides were tested, and their potencies and efficacies presented in Table 1. For the entire set of OP compounds studied, 12/26 (46%) and 20/26 (76%) of the chemicals had inhibitory effects on AChE activity using colorimetric and fluorescent methods, respectively (Table 1). Among these 26 compounds, 12 were parental organophosphorus pesticides that need to be metabolized to the oxon by CYP enzymes for inhibitory activity (also noted in Table 1). Among parent compounds, the colorimetric assay detected 3/12 compounds and the fluorescent assay detected 9/12.

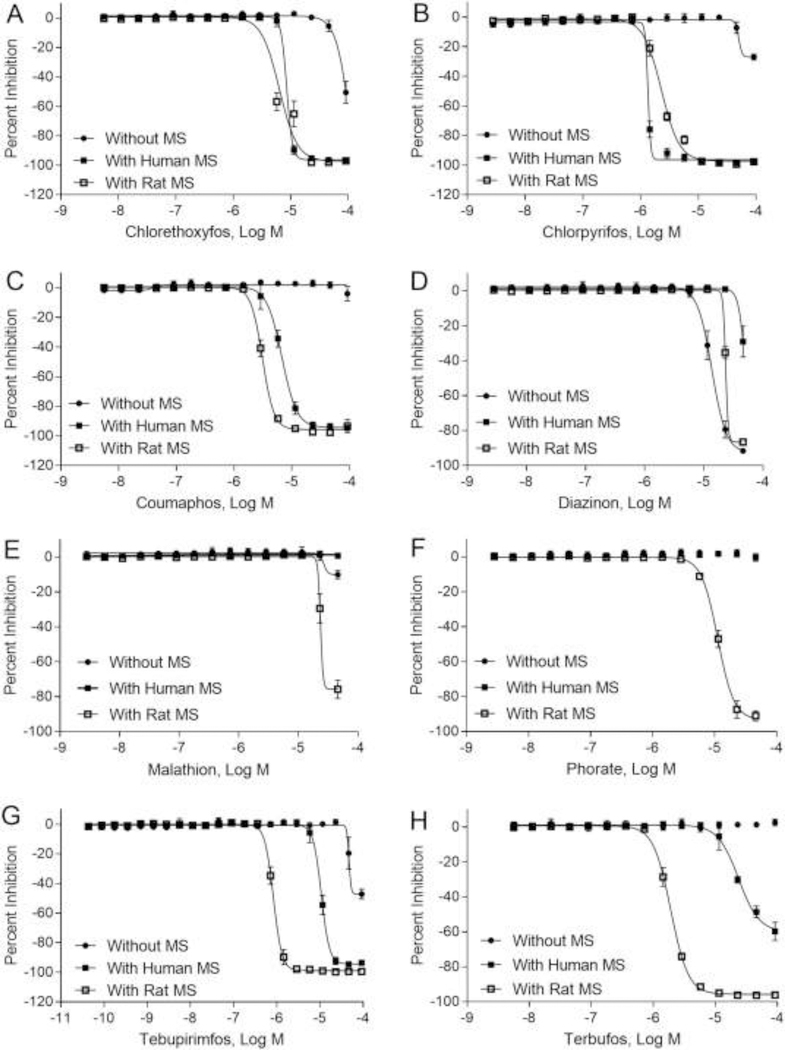

Next, parental compounds were tested for AChE activity in the presence of microsomes to study the effects of metabolism. Several concentration-response curves are presented in Fig. 4. For each OP compound, concentration-response profiles are presented for AChE assays with and without microsomes (rat or human). Shifts in concentration-response profiles can be observed for these OP compounds, illustrating the influence of metabolism on AChE inhibition.

Fig. 4.

Concentration -response curves of representative parental compounds in AChE assay with or without human/rat liver microsomes (MS). (A) Chlorethoxyfos; (B) Chlorpyrifos; (C) Coumaphos; (D) Diazinon; (E) Malathion; (F) Phorate; (G) Tebupirimfos; and (H) Terbufos. Each value represents the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

A summary of potency and efficacy data for parental OP compounds with and without microsomes were listed in Table 2. Evaluation using AChE assay plus human or rat microsomes detected an additional 3 and 5 parent compounds in the colorimetric assay and 0 and 2 compounds in the fluorescent assay, respectively. Combining the no microsome and added microsome assays (Table 2) yielded overall assay sensitivity of 65.4% (colorimetric, rat microsomes), 57.7% (colorimetric, human microsomes), 84.6% (fluorescence, rat microsomes), and 76.9% (fluorescence, human microsomes).

Table 2.

Potency and efficacy values of the parental OP compounds in AChE assays with human or rat microsomes (MS).

| Sample Name | IC50 (μM), efficacy (%), Colorimetric | IC50 (μM), efficacy (%), Fluorescence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −MS | +Human MS | +Rat MS | −MS | +Human MS | +Rat MS | |

| Chlorpyrifos | Inactive | 1.71±0.47 (−93.65±1.00) | 3.07±0.00 (−98.84±0.57) | 40.17±2.72 (−100.41±4.09) | 1.22±0.00 (−102.89±2.97) | 5.26±0.34 (−89.76±2.82) |

| Coumaphos | Inactive | 8.06±1.94 (−98.15±5.15) | 3.86±0.00 (−96.45±0.24) | 31.06±5.80 (−83.34±9.14) | 12.95±1.05 (−67.18±4.87) | 3.86±0.00 (−95.03±1.04) |

| Chlorethoxyfos | 70.04±3.42 (−46.27±7.72) | 10.88±0.00 (−102.91±1.64) | 10.09±0.68 (−105.17±2.46) | 37.20±2.42 (−99.25±3.99) | 31.57±8.80 (−99.07±7.79) | 29.55±1.93 (−100.22±1.52) |

| Tebupirimfos | 63.81±5.83 (−52.97±14.85) | 14.39±2.31 (−95.21±2.02) | 1.05±0.07 (−100.02±0.22) | 21.71±0.00 (−90.42±4.12) | 48.81±5.61 (−70.67±3.28) | 1.27±0.09 (−91.03±1.12) |

| Terbufos | Inactive | 31.74±5.73 (−57.67±2.16) | 2.35±0.15 (−95.72±0.97) | Inactive | Inactive | 1.60±0.10 (−85.32±0.32) |

| Diazinon | 37.99±3.32 (−102.16±3.10) | Inactive | 68.65±0.00 (−73.06±1.70) | 30.10±7.52 (−96.32±10.13) | 113.22±7.66 (−71.22±6.26) | Inactive |

| Dimethoate | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive |

| Bensulide | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 52.55±3.42 (−34.09±4.28) | Inactive | Inactive |

| Malathion | Inactive | Inactive | 68.65±0.00 (−59.41±8.66) | 54.53±0.00 (−76.98±2.92) | Inactive | Inactive |

| Phorate | Inactive | Inactive | 31.06±5.80 (−96.28±5.09) | 61.18±0.00 (−44.37±5.38) | Inactive | 14.81±0.96 (−72.00±2.38) |

| Phosmet | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 61.18±0.00 (−65.27±2.96) | Inactive | 52.55±3.42 (−43.55±1.26) |

| Pirimiphos-methyl | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | 41.74±2.72 (−41.96±3.86) |

Note: IC50, concentration of half-maximal inhibition; each value of potency (IC50, μM) and efficacy (% of positive control, expressed in parentheses) is the mean ± SD of the results from three experiments.

Among the 3 active parental compounds using colorimetric method without microsomes, 2 compounds, chlorethoxyfos and tebupirimfos, had increased potency after human or rat microsome addition but diazinon became either inactive (human) or lower potency (rat). Seven compounds (diazinon, dimethoate, malathion, phorate, phosmet, pirimiphos-methyl and bensulide) did not show inhibitory effects for AChE activity with human microsome addition and 4 compounds (dimethoate, phosmet, pirimiphos-methyl and bensulide) did not have inhibitory effects with rat microsomes addition. Three of 9 parental compounds active without microsomes using the fluorescent method (chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, and chlorethoxyfos) became more potent with human microsomes but tebupirimfos and diazinon less so (Table 2). With addition of rat microsomes, six compounds originally active without microsomes (chlorpyrifos, coumaphos, chlorethoxyyfos, tebupirimfos, phorate and phosmet) became more potent in AChE inhibition. However, diazinon, bensulide and malathion became inactive with rat microsomes added in fluorescence method.

DISCUSSION

In this study, assays using recombinant human AChE protein were developed for primary screening of chemicals that inhibit AChE. Moreover, the enzyme assays, using colorimetric or fluorescent methods, were then coupled with human or rat liver microsomes for identifying chemicals that need metabolism to be AChE inhibitors. Two detection methods which used different readouts, colorimetric and fluorescent, were employed to measure AChE activity. The integrated interpretation of these approaches can mitigate assay interferences caused by specific compounds and assay technology combinations, thereby increasing overall chemical assessment accuracy (Thorne et al., 2010). The assays were optimized in a 1536-well plate format, which enabled efficient screening of large chemical libraries.

The performance of the assays was characterized by screening a group of known OP chemical compounds including parental compounds and their active oxon forms. The oxon derivative, formed metabolically by CYP isozymes, and has much more potent inhibitory effect on acetylcholinesterase. The AChE assays with CYP activity added in the form of liver microsomes performed well with CV ≤ 3%, S/B ≥ 3 and Z’ factor value >0.7. Of the 26 chemicals tested using the colorimetric method, 12 (10 oxon derivatives and 2 parental compounds) showed AChE inhibition. There were 20 compounds (13 oxon derivatives and 7 parental compounds) that showed AChE inhibition using the fluorescent method (Table 1). Some oxon derivatives, such as omethoate and tetrachlorvinphos, inhibited AChE activity in fluorescent method, but did not show the inhibitory effects using colorimetric method. However, some compounds, such as naled, showed inhibitory effect on AChE activity in colorimetric method, but not in fluorescent method. Overall, fluorescence detection is more sensitive than the absorbance-based detection in high-throughput screening that has small sample amounts and volumes (Inglese et al., 2007). Therefore, the fluorescent method employed for screening in parallel with the colorimetric method can greatly increase hits and reduce interferences. Some oxon compounds including acephate and fosthiazate did not show inhibition effects on AChE using either method. Acephate was reported to be a weak inhibitor of AChE in human with IC50 of 5.4 mM (Bennett and Morimoto, 1982), which is much higher than the highest concentration of tested compounds in our screening. Fosthiazate was also a week AChE inhibitor, and IC50 cannot be determined directly, since the concentration range has exceeded the solubility (Lin et al., 2007). Discrepant results between the two methods can be explained by assay interferences. The colorimetric method is prone to interference by thiols and oximes (Ellman, 1959; Sakurada et al., 2006) and the fluorescent method can also lead to false positives, since many compounds are themselves fluorescent. The combination of the two methods is recommended for evaluation of the AChE inhibitors.

Many parental OPs, such as chlorpyrifos, tebupirimfos and chlorethoxyfos, only showed the inhibitory effects on AChE after addition of metabolic component into the reaction, signifying these parental compounds need metabolism to be AChE inhibitors. The role of human CYPs such as CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2B6 in pesticides biotransformation in vitro was reviewed comprehensively (Abass et al., 2011). Microsomes are a practical model to study xenobiotic metabolism: they are easy to prepare, have good stability, are easy to adapt to higher throughput assays, and containing high CYP concentration (Ekins et al., 2000; Pelkonen et al., 2005; Brandon et al., 2003). From the present study, chlorpyrifos, tebupirimfos, chlorethoxyfos, and coumaphos had more inhibitory effect on AChE after addition of human or rat microsomes. We also found that the colorimetric AChE assay treated with rat microsomes identified three more compounds as AChE inhibitors, diazinon, malathion and phorate, than did the assay treated with human microsomes. The fluorescent AChE assay treated with rat microsomes also identified more compounds than those with human microsomes, such as terbufos, phorate, phosmet, and pirimiphos-methyl. This difference may be due to difference in CYP activity between human and rat microsomes. Rat microsomes prepared from aroclor 1254-induced rat liver, have much higher CYP activity than that for the untreated rat liver microsomes and may also differ from human microsomes with respect to isozymes expressed (Easterbrook et al., 2001). Aroclor 1254-induced and uninduced rat liver microsomes or human liver microsomes have been compared in the metabolism of substrates selectively metabolized by CYP isoforms and it was concluded that rat liver microsomes may not always be relevant to human (Easterbrook et al., 2001). Moreover, AChE assay with rat microsomes was included in the current study because one of the goals of Tox21 program is to prioritize the compounds for further in-depth investigation including in vivo animal study.

In our study, some of the parental compounds were not activated by human microsomes, such as dimethoate, malathion, and pirimiphos-methyl. Following exposure to dimethoate, cholinesterase activity was inhibited in rats, mice, birds, fish, and farm animals, while no AChE inhibition was observed in human volunteers (International Programme on Chemical Safety, 1989). Malathion can be rapidly degraded by carboxylesterases, which competes with CYP-catalyzed formation of malaoxon, the toxic metabolite (Buratti et al., 2005). Therefore, the degradation by carboxylesterases would reduce production of the toxic metabolite malaoxon, which is a potent AChE inhibitor. Upon oral intake of 0.25 mg pirimiphos-methyl/kg bw/day for 56 days, no erythrocyte cholinesterase effects were observed in seven human volunteers (Evaluation For Acceptable Daily Pirimiphos-methyl Intake, 2018).

Some parental compounds such as diazinon and phorate, did not inhibit AChE after treatment with human microsomes, but they did with rat microsomes. In addition to forming an active, highly toxic oxon intermediate metabolite that inhibits AChE, the parent OP compound can also form detoxified metabolites by undergoing a dearylation reaction catalyzed by CYPs (Ma and Chambers, 1994). The balance between activating and detoxifying processes of OPs determines their potential risk to humans. In our study, diazinon showed inhibitory effects on AChE with IC50 of 37.99 μM after incubation with rat microsomes, but had no inhibitory effect on AChE after treatment with human microsomes using colorimetric method. Diazinon has been reported to be metabolized by CYP2C19, demonstrating higher activity of forming detoxified metabolite compared with the bioactive oxon metabolite (Sams et al., 2004; Ellison et al., 2012; Mutch and Williams, 2006), consistent with our results. Phorate, which can interact with both CYP and flavin-containing monooxygenase (Levi and Hodgson, 1988), may account for its inactive role in inhibiting AChE after incubation with human microsomes.

In our study, the AChE assays with or without microsome were developed and optimized into a high-throughput format. The assays were also characterized with a group of OP compounds that include parental compounds and oxon derivatives. The results demonstrated important methodology for providing xenobiotic metabolism capacity to biochemical assays, a critical goal for in vitro approaches. From the current study, several steps to identify AChE inhibitors are recommended. First, the compounds should be screened using both assay methods. Second, the human and rat micrsomes should be included to identify compounds that need metabolic activation. Third, a group of reference compounds such as chlorpyrifos oxon, diazoxon, malaoxon, chlorpyrifos, chlorethoxyfos and terbufos should be used to evaluate AChE inhibition assay performance. In summary, the enzyme-based assays with and without liver microsomes are promising for the profiling of AChE inhibitors as well as for studies of OP metabolism and inclusion of liver microsomal metabolism capacity increases assay sensitivity. Results must be interpreted carefully, however, as use of varied assay technologies and metabolic activation systems can yield complex outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. Stephanie Padilla and Jeremy Fitzpatrick for providing valuable comments and editing the manuscript. This study was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and Interagency Agreement IAA #NTR 12003 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences/Division of the National Toxicology Program to the NCATS, National Institutes of Health. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the statements, opinions, views, conclusions, or policies of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, the NIH, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Reference

- 1.Massoulie J, et al. , Molecular and cellular biology of cholinesterases. Prog Neurobiol, 1993. 41(1): p. 31–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McHardy SF, et al. , Recent advances in acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Reactivators: an update on the patent literature (2012–2015). Expert Opin Ther Pat, 2017. 27(4): p. 455–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaga K and Dharmani C, Methyl parathion: an organophosphate insecticide not quite forgotten. Rev Environ Health, 2006. 21(1): p. 57–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farahat FM, et al. , Biomarkers of chlorpyrifos exposure and effect in Egyptian cotton field workers. Environ Health Perspect, 2011. 119(6): p. 801–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sultatos LG, Mammalian toxicology of organophosphorus pesticides. J Toxicol Environ Health, 1994. 43(3): p. 271–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buratti FM, et al. , CYP-specific bioactivation of four organophosphorothioate pesticides by human liver microsomes. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2003. 186(3): p. 143–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sams C, Cocker J, and Lennard MS, Biotransformation of chlorpyrifos and diazinon by human liver microsomes and recombinant human cytochrome P450s (CYP). Xenobiotica, 2004. 34(10): p. 861–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foxenberg RJ, et al. , Human hepatic cytochrome p450-specific metabolism of parathion and chlorpyrifos. Drug Metab Dispos, 2007. 35(2): p. 189–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martiny VY and Miteva MA, Advances in molecular modeling of human cytochrome P450 polymorphism. J Mol Biol, 2013. 425(21): p. 3978–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zanger UM and Schwab M, Cytochrome P450 enzymes in drug metabolism: regulation of gene expression, enzyme activities, and impact of genetic variation. Pharmacol Ther, 2013. 138(1): p. 103–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kappers WA, et al. , Diazinon is activated by CYP2C19 in human liver. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2001. 177(1): p. 68–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tang J, et al. , Metabolism of chlorpyrifos by human cytochrome P450 isoforms and human, mouse, and rat liver microsomes. Drug Metab Dispos, 2001. 29(9): p. 1201–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dai D, et al. , Identification of variants of CYP3A4 and characterization of their abilities to metabolize testosterone and chlorpyrifos. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics, 2001. 299(3): p. 825–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li AP, Screening for human ADME/Tox drug properties in drug discovery. Drug Discov Today, 2001. 6(7): p. 357–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li AP, In vitro approaches to evaluate ADMET drug properties. Curr Top Med Chem, 2004. 4(7): p. 701–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang DL, et al. , Preclinical experimental models of drug metabolism and disposition in drug discovery and development. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B, 2012. 2(6): p. 549–561. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tingle MD and Helsby NA, Can in vitro drug metabolism studies with human tissue replace in vivo animal studies? Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 2006. 21(2): p. 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asha S and Vidyavathi M, Role of human liver microsomes in in vitro metabolism of drugs-a review. Appl Biochem Biotechnol, 2010. 160(6): p. 1699–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ekins S, et al. , Present and future in vitro approaches for drug metabolism. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods, 2000. 44(1): p. 313–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reed JR and Backes WL, Formation of P450. P450 complexes and their effect on P450 function. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2012. 133(3): p. 299–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujiki Y, et al. , Isolation of Intracellular Membranes by Means of Sodium-Carbonate Treatment - Application to Endoplasmic-Reticulum. Journal of Cell Biology, 1982. 93(1): p. 97–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang H, et al. , Content and activity of human liver microsomal protein and prediction of individual hepatic clearance in vivo. Sci Rep, 2015. 5: p. 17671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Araya Z and Wikvall K, 6 alpha-hydroxylation of taurochenodeoxycholic acid and lithocholic acid by CYP3A4 in human liver microsomes. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1999. 1438(1): p. 47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang R, A Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Data Analysis Pipeline for Activity Profiling. Methods Mol Biol, 2016. 1473: p. 111–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang Y and Huang R, Correction of Microplate Data from High-Throughput Screening. Methods Mol Biol, 2016. 1473: p. 123–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y, et al. , A grid algorithm for high throughput fitting of dose-response curve data. Curr Chem Genomics, 2010. 4: p. 57–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abass K, et al. , Metabolism of Pesticides by Human Cytochrome P450 Enzymes In Vitro - A Survey. Insecticides - Advances in Integrated Pest Management, 2011: p. 165–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelkonen O, et al. , Prediction of drug metabolism and interactions on the basis of in vitro investigations. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology, 2005. 96(3): p. 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brandon EF, et al. , An update on in vitro test methods in human hepatic drug biotransformation research: pros and cons. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol, 2003. 189(3): p. 233–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Easterbrook J, Fackett D, and Li AP, A comparison of aroclor 1254-induced and uninduced rat liver microsomes to human liver microsomes in phenytoin O-deethylation, coumarin 7-hydroxylation, tolbutamide 4-hydroxylation, S-mephenytoin 4’-hydroxylation, chloroxazone 6-hydroxylation and testosterone 6beta-hydroxylation. Chem Biol Interact, 2001. 134(3): p. 243–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma T and Chambers JE, Kinetic parameters of desulfuration and dearylation of parathion and chlorpyrifos by rat liver microsomes. Food Chem Toxicol, 1994. 32(8): p. 763–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ellison CA, et al. , Human hepatic cytochrome P450-specific metabolism of the organophosphorus pesticides methyl parathion and diazinon. Drug Metab Dispos, 2012. 40(1): p. 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mutch E and Williams FM, Diazinon, chlorpyrifos and parathion are metabolised by multiple cytochromes P450 in human liver. Toxicology, 2006. 224(1–2): p. 22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levi PE and Hodgson E, Stereospecificity in the oxidation of phorate and phorate sulphoxide by purified FAD-containing mono-oxygenase and cytochrome P-450 isozymes. Xenobiotica, 1988. 18(1): p. 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]