Abstract

Background:

Despite growing demand for home care nursing, there is a growing home care workforce shortage, due in part to hospital-centric nursing curricula that lead students to undervalue of home care and community practice setting (Van Iersel, et al., 2018a, 2018b).

Objectives:

Articulate an international vision for the future of home care education, research, practice, and management shared by experienced home care nurses working in leadership roles.

Design:

Qualitative content analysis.

Settings and Participants:

The sample included 50 home care professionals from 17 countries.

Methods:

Home care nurse leaders (in education, research, practice, and management roles) were recruited through professional international nursing networks to participate in a structured online survey about priorities for the future of home care in 2014. Responses were open coded by two independent researchers. Preliminary categories and sub-themes were developed by the research team and revised after a modified member-checking process that included presentation and discussion of preliminary findings at three international nursing meetings in 2015 and 2016.

Results:

Four major themes emerged reflecting international priorities for the future of home care education, research, practice, and management: 1) Build the evidence base for home care; 2) Design better systems of care; 3) Develop leaders at all levels; and 4) Address payment and policy issues.

Conclusions:

Collectively, the findings provide a major call to action for nurse educators to redesign existing pre- and post-licensure educational programs to meet the growing demand for home care nurses. Innovations in education that focus on filling gaps in the evidence-base for community nursing practice, and improving access to continuing education and evidence-based resources for practicing home care nurses and nurse managers should be prioritized.

1. INTRODUCTION

Home care has multiple meanings around the world. In some places, it is the provision of skilled and professional nursing care in the home, while in other places care is mostly provided by family members with teaching and support by hospital or clinic-based health care providers. For the purpose of this paper, home care is defined as the provision of health care in the home provided by licensed or registered health care professionals including (but not limited to) nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, and physicians. Regardless of the kind of home care system in place, the predictions are that home care will grow with the aging of the world’s population, the growth of chronic conditions, and the development of technology to support the provision of health care at home.

2. BACKGROUND

The demand for home care is predicted to greatly increase over the coming decade. One reason for the projected increase in demand for home care is the dramatic increase in average life expectancy with the number of people over 60 years expected to double by 2050 (World Health Organization, 2015). In addition to increased life span, fertility rates have declined globally, contributing to the shift in demographics and greying of the population (World Health Organization, 2015). Advances in public health and medical care have also changed the patterns of caregiving for the ill and elderly, extending intensive caregiving for advanced chronic illnesses from periods of days and weeks to years and decades. Additionally, there are financial incentives and public demand for national and private health insurers to provide medical and supportive care in the family home, as opposed to more costly and restrictive hospitals. Even in countries and cultures where multi-generational homes and care of aging parents and grandparents is the norm, frail elders often require additional community services or institutional housing and care. Finally, home is becoming the preferred site of primary, secondary, and tertiary care due to technological advances, ranging from smartphones and telehealth to home use of equipment previously only found in hospitals and intensive-care units (World Health Organization, 2015).

In most countries, nursing is a key component of the home care system. In contrast to the growing need for home care nurses, nursing education is predominately focused on preparation of nurses for hospital settings. Home care nurses depend on evidence to guide their practice yet there is a paucity of evidence for practice as well as a lack of education to prepare home care nurses and the best practices for management of home care services. While nursing is the most common provider of home care around the world, there is little evidence on what home care nurses need to better support their practice. Much of the comparative research that has been done in this area has been country or continent-specific, and predominately in North America and Europe (Maetens, et al., 2017; Narayan & Scafide, 2017; Sutcliffe, 2017).

3. METHODS

3.1. Design

This study used a descriptive, qualitative content analysis design with conventional content analysis of responses to open-ended questions about priorities for the future of home care education, research, practice, and management.

3.2. Data Collection

Data were collected using an on-line survey between January and December 2014 through Qualtrics Online Survey Software. The survey consisted of four open-ended questions eliciting participants’ expert opinion about priorities for home care 1) education, 2) research, 3) clinical practice, and 4) management. Each question was asked in the format: “Thinking broadly, please list below the priorities for [education / research/ clinical practice / management] in home care nursing.” Additionally, demographic information collected included participant gender, country of residence, years of nursing experience, and years of home care experience.

3.3. Settings

Participants were recruited through a modified snowball sampling approach, with a goal of global representation of perspectives on home care priorities. Rigorous efforts were made to engage home care experts living outside the United States. An invitation to participate in the survey was distributed through professional networks of members of the International Home Care Nurses Organization (IHCNO). IHCNO members then shared information about the survey and an electronic invitation to participate with their professional home care nurse networks. In addition, one of the authors disseminated the study invitation to authors of 30 international peer-reviewed journal articles related to home care education, research, practice, management, and health policy.

3.4. Participants

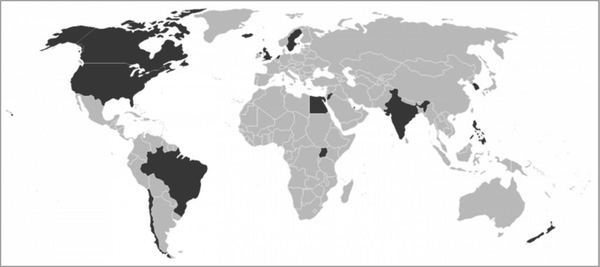

Completed surveys were received from 50 participants. The participants all had home care nursing experience, with an average of 29 years of nursing experience (range 8–50 years, s.d. = 11 years), and an average of 17 years of home care experience (range 1–49 years, s.d. = 12 years). Participants self-identified from 17 countries: Brazil, Canada, Chile, Egypt, Iceland, India, Jordan, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Philippines, Qatar, Singapore, South Korea, Sweden, Uganda, United Kingdom, the United States of America (U.S.), and the U.S. territory of Puerto Rico (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Map Highlighting the 17 Countries Represented by Survey Respondents

3.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Case Western Reserve University, IRB #2013–649. Informed consent with waiver of signature was provided as the opening page of the survey. Waiver of signature was employed as it provided anonymity for the participants. For confidentiality, the online survey system was set to not include Internet Protocol (IP) address which would have allowed for location determination. As part of the informed consent process, participants were given information on the purpose of the study, provided the option to not participate, informed of potential risks and benefits, and assured of confidentiality.

3.6. Data Analysis

Research team members iteratively identified categories and sub-themes for each open-ended research question, and sub-themes were later compared and contrasted across questions using conventional content analysis. Conventional content analysis is used to describe a phenomenon when existing theory or research literature is limited, in this case global priority areas for the future of home care scholarship and leadership (Elo & Kyngas, 2007). The advantage of conventional content analysis is that data from the participants drives the generation of codes and interpretation without the imposition of preconceived categories or theoretical perspectives (Hsiu-Fang & Shannon, 2005).

Because the analysis sought to identify global priorities for home care, responses from each participant were coded with a participant and country code, and then split into work files, corresponding to the four main survey questions (asking about priorities for education, research, practice, and management). Conventional content analysis was used to develop data-driven clusters of categories and themes within each focus area (education, research, management, and practice). The first two authors worked individually and jointly to code participants’ answers, create categories, and summarize into major and minor themes for each open-ended question. After initial coding of the responses using word processing software, the higher level analysis was done manually, using a card sort method that maximized integration of perspectives from different countries and participants in the definition of categories and selection of sub-themes and cross-cutting major themes.

3.7. Rigor

Through an iterative process, with input from the senior author, a consistent and reliable method of coding and categorization was developed, with the goal of achieving results that were dependable and confirmable. For example, the category “recruitment and retention” began with a cluster of statements from different participants that included the responses: retention, staff retention, recruiting, recruitment and retention, and expanded to include commitment to staff development, mentorship of field clinicians, and what empowers the home care nurse. The categories and emerging sub-themes developed for each focus question were then considered in context to each other, and synthesized to develop over-arching major themes that encompassed priorities from each of the core areas (education, research, management, and practice).

Research team: The study authors collectively have over 60 years of relevant home care nursing experience and include internationally and nationally recognized content experts with experience in home care education, research, practice, and management. The first author is a federally funded health services researcher with home health care experience in low-income, and Spanish-speaking communities in the United States. The second author has home care management and related teaching experience in Qatar. At the time of the study, the senior author was the director of the World Health Organization Collaborating Center for Home Care and co-chair of the Institute of Medicine workshop on “The Future of Home Health Care” in the United States (Landers et al., 2016).

Preliminary findings were presented by each of the authors in turn at three international nursing conferences. After each author presented the preliminary findings, conference attendees in the audience were engaged in the discussion of findings, which helped to clarify categories, enriched interpretation of findings, and development of policy recommendations. The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution to the discussion and conclusions of this paper by the attendees at the 2015 International Home Care Nurses Organization Conference, the 2015 Sigma Theta Tau International Research Congress, and the 2016 World Health Organization Collaborating Centers for Nursing and Midwifery Conference.

4. RESULTS

Four major, cross-cutting themes and 16 sub-themes emerged reflecting a global call to action to: 1) generate and use evidence-based guidelines for home care; 2) re-design health care delivery systems to better support home care; 3) develop leaders for home care at all levels that work within and across sectors to create community health; and 4) address payment and policy issues that create barriers to optimal care at organizational and national levels. The text that follows presents each theme in the context of defining priorities for a global agenda in home care education, research, practice, and management and are summarized in Table 1. Details of the major and minor themes, 51 categories, and hundreds of codes and detailed statements that are included as Supplemental Digital Content.

Table 1.

Summary of Cross-Cutting Themes for Home Care Priorities by Focus Area

| Generate and Use Evidence-Based Guidelines | Design Better Systems of Care | Develop Leaders at All Levels | Address Payment and Policy Issues | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Priorities for Home Care Education | Prepare generalist and specialist nurses to deliver evidence-based care and work autonomously at the top of their professional licenses. | Cultivate culture of continuous education at nurse and organization level to keep current on new technologies and approaches to home care. | Advance home care through emphasis on advanced practice training in home care and role of interprofessional care team members. | Create centers of excellence, certification programs, and include principles of home care payment and policy in graduate and undergraduate curricula. |

| Priorities for Home Care Research | Demonstrate the value of home care and what works, for patients, caregivers, public health/community impact. | Evaluate home care service delivery and staffing models to determine best outcomes for patients and workforce. | Understand the relationship between nurses’ education level, communication across health care team & outcomes. | Be rigorous in designing studies that demonstrate the value of home care, communicate results to payers and policy makers. |

| Priorities for Home Care Practice | Integrate evidence-based care and teaching strategies into basic and advanced home care to improve patient outcomes. | Embrace interdisciplinary care coordination and management, and new roles for advanced home care nurses to bridge gaps in healthcare system. | Define excellence in home care through consensus on minimum competencies for home care nurses, and home care specialty certification. | Advocate [for yourselves] to have the resources (staffing and equipment) needed. Understand that documentation of nursing care is key to getting resources. |

| Priorities for Home Care Management | Ensure staff and management have access to evidence-based practice guidelines and decision support tools. | Develop infrastructure for nursing excellence through use of electronic resources/record and decision support. | Be a change agent to create conditions for optimal team relationships, care delivery, and community partnerships. | Learn to lead with increased regulations, meeting clinical and financial objectives while preserving (human) resources. |

4.1. A call to generate (and use) evidence-based guidelines for home care

Survey participants consistently stressed the need for the development of an evidence base for home care nursing, and to show the value of home care nursing through improvement of outcomes for patients, their families, and society at large. Specifically, priority areas for establishing the best practices and effectiveness of home care were around patient and caregiver education/engagement; chronic condition management; medication management, patient safety; and prevention of unnecessary hospitalizations. Additionally, participants said that best practice knowledge will empower nursing education and, as a result, improve patient, family and caregiver education. Some participants stressed the importance of home care infrastructure and decision support to identify patients at risk for complications, and ensure nurses have the resources (including time) to provide optimal nursing care and services.

4.2. A call to re-design health systems for home care

Home care nurses described a need for a better system of care that they envisioned developing through research on models of home care, educating future generations of nurses for advanced practice in home care practice and administration, formalizing home care as a nursing specialty area of practice, and through management practices that support coordination of patient care and care management using new technologies and electronic record systems.

4.3. A call to develop home care leaders at all levels

The need for leadership development in home care was exemplified through a call for research on the role of nurses in inter-professional teams and as leaders in care coordination. Nurse educators are challenged to educate all nursing students in leadership necessary for patient care and advocacy in inter-professional team-based care. Priorities for home care practice include developing patients and their caregivers as full members of the health care team through education and empowerment. Similarly, home care management is tasked with prioritizing leadership development among managers and staff nurses alike, and the recruitment and retention of the home care workforce for the near future.

4.4. A call to address payment and policy issues that create barriers to care

The final theme unites many priorities that at first seemed unrelated, due to the global differences in health policy and the financing of social services. Participants asked for researchers to consider the impact of payment models on the home care workforce and patient outcomes. Nurse educators are tasked with preparing nurses who are prepared to utilize standardized assessment and outcome measurement tools, and to document their care in a way that meets regulations and is sensitive to requirements for payment of services. Finally, home care management is in need of resources and support to balance cost-containment, quality outcomes, and home care workforce health and retention.

5. LIMITATIONS

This study was limited by online delivery methods, which largely restricted recruitment of participants to nurses who used email and were connected professionally to IHCNO members. Additionally, the information and instructions for the survey were written in English, which may have inhibited participation among nurses who were not comfortable writing in English.

6. DISCUSSION

While there was some variation in survey participants’ prioritization of payment and documentation issues that were specific to their unique health care delivery systems (Cabin, 2015; Lustbader, et al., 2017), many common and cross-cutting themes emerged. For example, participants universally described a need for home care specific education and expanding the evidence-base to support home care nursing (Campbell-Yeo, et al., 2014; Dodzo & Mhloyi, 2017; Oltra-Rodríguez, et. al., 2017; Ploeg, et al., 2017). When compared to other sites of care like hospitals and nursing homes, there is a dearth of evidence for practice in home care. The emerging use of technology and telehealth was also one subtheme that emerged as a priority for home care education (see Supplemental Digital Content). For example, countries with a limited number of nurses may use telehealth to expand access to care (Chia, et. al., 2017; Flood, Hawkins & Rohloff, 2017; Lewis, et al., 2017), while countries with more plentiful resources may utilize telehealth for greater efficiency and cost-savings (Tsai, et al., 2016; Smith-Strøm, et al., 2016). Issues relative to regulation of home care practice and the financial system supporting home care were also a priority and reinforce country-specific accounts published in the literature (Bäck & Calltorp, 2015; Thumé, Facchini, Tommasi & Saraiva Viera, 2010; Timonen, Doyle & O’Dwyer, 2012).

Similarly, while nursing management skills may be similar between hospitals and home care, there are context-specific issues for home care management that include coordination of care across multiple organizations, and between professional and lay caregivers, including family members who are central to the delivery and effectiveness of home care. As emphasized by survey participants, attention to working conditions and management practices in home health care is critical to the future of high quality home-based care (De Groot, Maurits & Francke, 2017; Jarrín, Flynn, Lake & Aiken, 2014; Jarrín, Kang & Aiken, 2017). In addition, participants identified preparation of nurses for their role in care coordination and care planning as a high priority, reflecting the leadership role nurses provide in communication across health and social service sectors (Abrashkin, et al., 2016; Cao, et al. (2014; Moffett, Kaufman & Bazemore, 2017; Szebehely & Trydegård, 2012).

7. CONCLUSION

In summary, the cross-cutting themes reflect a global call to action for nursing education to: 1) develop and use evidence-based guidelines for home care; 2) re-design health care delivery systems to better support home care; 3) develop leaders for home care at all levels to work within and across sectors to create community health; and 4) address payment and policy issues that create barriers to optimal care at organizational and national levels. Findings related to home care education, practice, and management priorities reinforce key recommendations from a World Health Organization study of community health nursing in 12 countries facing health crises (Nkowane, et al., 2016). In addition, the findings related to home care research priorities focusing on development of evidence-based practice guidelines and minimum competencies for use in nursing education and certification programs reinforce prior work by Madigan & Vanderboom (2005). Their work was limited to the United States of America, and described high level home care research priorities to be: a) outcomes, b) health policy, c) use of advanced practice nurses (APNs), d) models of care/best practice, e) and resource use (Madigan & Vanderboom, 2005). The persistence of the similar themes over time and across 27 countries (including 12 from study by Nkowane, et al., 2016) reinforces the validity of the findings, and the importance of addressing these topics.

8. RECOMMENDATIONS

Collectively, the findings provide a major call to action for nurse educators to re-design existing pre- and post-licensure education for nurses to meet the critical home care needs of a rapidly aging population and their family caregivers. To meet the growing community nursing workforce demands, educators must begin with the curricula used during the first weeks and months of nursing school, that traditionally have focused on hospital and acute care. These first exposures to nursing through text books, lectures, and simulation labs have a strong impact on nursing students’ attitudes and beliefs regarding the desirability and status of different types of nursing, often resulting in an undervaluing of community nursing and home care (van Iersel, et al., 2017; van Iersel, et al., 2018; Algoso, et al., 2016). In addition, there is a need for post-basic nursing education programs to work with health care organizations to prepare home care nurses and nurse mangers with the specialized skills needed for successful practice in community settings. Nurse educators can also help to fill the gap in evidence-based guidelines for home care through collaboration with researchers on the development and synthesis of best-practice guidelines. Finally, nurse educators can work with students and professionals at all levels to prepare nurses to effectively communicate with local and national policy makers about education, regulation, payment, and health policies that impact quality of care and access to home and community nursing care.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Global priorities for the future of home care education, research, practice, and management include:

A call to generate (and use) evidence-based guidelines for home care

A call to re-design health systems for home care

A call to develop home care leaders at all levels

A call to address payment and policy issues that create barriers to care

Funding:

This project was supported, in part, by grant number R00HS022406 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement:

No conflict of interest has been declared by the author(s).

Contributor Information

Olga Jarrín, School of Nursing, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, Institute for Health, Health Care Policy, and Aging Research, 112 Paterson Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901.

Fatemah Ali Pouladi, Home Healthcare Service, Hamad Medical Corporation, Qatar.

Elizabeth A. Madigan, Case Western Reserve University.

References

- Abrashkin KA, et al. (2016) Providing acute care at home: Community paramedics enhance an advanced illness management program-preliminary data. J American Geriatric Society. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht MN, & Perry KM (1992) Home health care. Delineation of research priorities and formation of a national network group. Clinical Nursing Research, 1:305–311. doi: 10.1177/105477389200100309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Algoso M, Peters K, Ramjan L, East L (2016). Exploring undergraduate nursing students’ perceptions of working in aged care settings: A review of the literature. Nurse Education Today, 36:275–280. doi: 10.1016/jnedt.2015.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bäck MA, Calltorp J. (2015) The Norrtaelje model: A unique model for integrated health and social care in Sweden. Int J Integr Care, 15:e016 Available online at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4628508/ (accessed 25 Aug 2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabin WD (2015) Medicare constrains social workers’ and nurses’ home care for clients with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Work, 60(1):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell-Yeo M, et al. (2014) Educational barriers of nurses caring for sick and at-risk infants in India. International Nursing Review, 61:398–405. doi: 10.1111/inr.12121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao MJ, et al. (2014) Chinese community-dwelling elders’ needs: promoting ageing in place. International Nursing Review, 61:327–335. doi: 10.1111/inr.12119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia YC, et al. (2017) Current status of home blood pressure monitoring in Asia: Statement from the HOPE Asia Network. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). doi: 10.1111/jch.13058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot K, Maurits EEM & Francke AL (2017) Attractiveness of working in home care: An online focus group study among nurses. Health Soc Care Community. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodzo MK & Mhloyi M (2017) Home is best: Why women in rural Zimbabwe deliver in the community. PLoS One. 12(8):e0181771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S & Kyngäs H (2007) The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62:107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood D, Hawkins J & Rohloff P (2017) A Home-Based Type 2 Diabetes Self-Management Intervention in Rural Guatemala. Prev Chronic Dis, 10:14:E65. doi: 10.5888/pcd14.170052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiu-Fang H & Shannon SE (2005) Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrín O, Kang Y & Aiken LH (2017) Pathway to better patient care and nurse workforce outcomes in home care. Nursing Outlook. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2017.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrín O, Flynn L, Lake ET & Aiken LH (2014) Home health agency work environments and hospitalizations. Medical Care, 52:877–83. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landers S, et al. (2016) The Future of Home Health Care: A Strategic Framework for Optimizing Value. Home Health Care Manag Pract, 28(4):262–278. doi: 10.1177/1084822316666368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C et al. (2017) A community virtual ward model to support older persons with complex health care and social care needs. Clin Interv Agin, 12:985–993. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S130876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustbader D, et al. (2017) The impact of a home-based palliative care program in an Accountable Care Organization. JPalliative Medicine, 20(1 ):23–28. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.150170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madigan EA & Vanderboom C (2005) Home health care nursing research priorities. Applied Nursing Research, 18:221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2004.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maetens A, et al. (2017) Policy measures to support palliative care at home: a cross-country case comparison in three European countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffett ML, Kaufman A & Bazemore A (2017) Community health workers bring cost savings to patient-centered medical homes. J Community Health. doi: 10.1007/s10900-017-0403-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan MC & Scafide KN (2017) Systematic review of racial/ethnic outcome disparities in home health care. J Transcult Nurs. doi: 10.1177/1043659617700710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nkowane AM, Khayesi J, Suchaxaya P, Phiri ML, Malvarez S, Ajuebor P (2016). Enhancing the role of community health nursing for universal health coverage: A survey of the practice of community health nursing in 13 countries. Annals of Nursing and Practice, 3(1):1042 ISSN: 2379–9501 [Google Scholar]

- Oltra-Rodríguez E, et al. (2017) The training of specialists in family and community health nursing according to the supervisors of the teaching units. Enferm Clin, 27(3):179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2017.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ploeg J, et al. (2017) An exploration of experts’ perceptions on the use of interprofessional education to support collaborative practice in the care of community-living older adults. J Interprof Care. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2017.1347610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Strøm H, et al. (2016) An integrated wound-care pathway, supported by telemedicine, and competent wound management--Essential in follow-up care of adults with diabetic foot ulcers. International JMedical Informatics, 94:59–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2016.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutcliffe C, et al. (2017) Caring for a person with dementia on the margins of long-term care: A perspective on burden from 8 European countries. J Am Med Dir Assoc. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szebehely M & Trydegard GB (2012) Home care for older people in Sweden: A universal model in transition. Health and Social Care in the Community, 20:300–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01046.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thumé E, Facchini LA, Tommasi E & Saraiva Viera LA (2010) Home health care for the elderly: Associated factors and characteristics of access and health care. Rev Saúde Pública, 44:1–9. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89102010005000038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timonen V, Doyle M & O’Dwyer C (2012) Expanded, but not regulated: Ambiguity in home-care policy in Ireland. Health and Social Care in the Community, 20:310–318. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2011.01048.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai LLY, et al. (2016) Satisfaction and experience with a supervised home-based real-time videoconferencing telerehabilitation exercise program in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Int J Telerehabil, 8(2):27–38. doi: 10.5195/ijt.2016.6213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Iersel M, Latour CHM, de Vos R, Kirschner PA, Scholte op Reimer WJM (2018a). Perceptions of community care and placement preferences in first-year nursing students: A multicenter, cross-sectional study. Nurse Education Today, 60:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Iersel M, Latour CHM, van Rijn M, de Vos R, Kirschner PA, Scholte Op Reimer WJM (2018b). Factors underlying perceptions of community care and other healthcare areas in first-year baccalaureate nursing students: A focus group study. Nurse Education Today, 66:57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2015) World report on ageing and health. Available at: http://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/ (accessed 21 Mar 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.