Abstract

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), which are a class of pattern-recognition receptors, can sense specific molecules of pathogens and then activate immune cells, such as neutrophils. The regulation of TLR signaling in immune cells has been investigated by various studies. However, the interaction of TLR signaling-activated microRNAs (miRNAs) and genes has not been well investigated in a specific type of immune cells. In the present study, neutrophils were isolated from peripheral blood of a healthy donor, and then treated for 16 h with Staphylococcus aureus lipoteichoic acid (LTA), which is an agonist of TLR2. The miRNA and mRNA expression profiles were analyzed via next-generation sequencing and bioinformatics approaches. A total of 290 differentially expressed genes between LTA-treated and vehicle-treated neutrophils were identified. Gene ontology analysis revealed that various biological processes and pathways, including inflammatory responses, defense response, positive regulation of cell migration, motility, and locomotion, and cell surface receptor signaling pathway, were significantly enriched. In addition, 38 differentially expressed miRNAs were identified and predicted to be involved in regulating signal transduction and cell communication. The interaction of 4 miRNAs (hsa-miR-34a-5p, hsa-miR-34c-5p, hsa-miR-708-5p, and hsa-miR-1271-5p) and 5 genes (MET, CACNB3, TNS3, TTYH3, and HBEGF) was proposed to participate in the LTA-induced signaling network. The present findings may provide novel information for understanding the detailed expression profiles and potential networks between miRNAs and their target genes in LTA-stimulated healthy neutrophils.

Keywords: neutrophil, lipoteichoic acid, microRNA, innate immunity

Introduction

The innate immune system can detect the presence of pathogens, such as viruses and bacteria, and activate immune responses to eliminate the infections. These pathogens can be recognized by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and trigger activation of innate immunity (1,2). The family of Toll-like receptors (TLRs) is a class of PRRs in mammals (3). TLR4 is an important receptor recognizing lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria (4,5). By contrast, the wall components of Gram-positive bacteria, such as peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipoteichoic acid (LTA), are recognized by TLR2 (6-8). PGN and LTA can induce septic shock and multiple organ failure (9).

TLR2 expression can be detected in various types of human immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and polymorphonuclear leukocytes (also termed granulocytes and include neutrophils, basophils and eosinophils) (10). In peripheral blood, neutrophils are the most abundant type of granulocytes and the first r immune cells to respond to infections. When human neutrophils are exposed to LTA, cell migration, degranulation, secretion of pro-inflammatory factors [including interleukin (IL)-8, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF)], increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and antimicrobial activity, and activation of TLR2 and NF-κB-mediated signaling pathways have been reported (11-14).

MicroRNA (miRNA) is a group of small non-coding RNAs with ~22 nucleotides. Emerging evidence suggests that miRNAs are involved in regulation of gene expression and immune responses (15,16). For example, miR-155, miR-146a, miR-UL112-3p and miR-344b-1-3p have been demonstrated to interact with TLR2 in pathological conditions (17-21). However, the interaction of miRNA and LTA-mediated immune activation has not been extensively investigated in a specific type of immune cells. Thus, the present study aimed to investigate the expression mRNA and miRNA in Staphylococcus aureus LTA-stimulated human neutrophils via next-generation sequencing. To understand the LTA-mediated effect in healthy immune cells, neutrophils were obtained from the peripheral blood of a healthy donor.

Materials and methods

Neutrophil isolation and LTA treatment

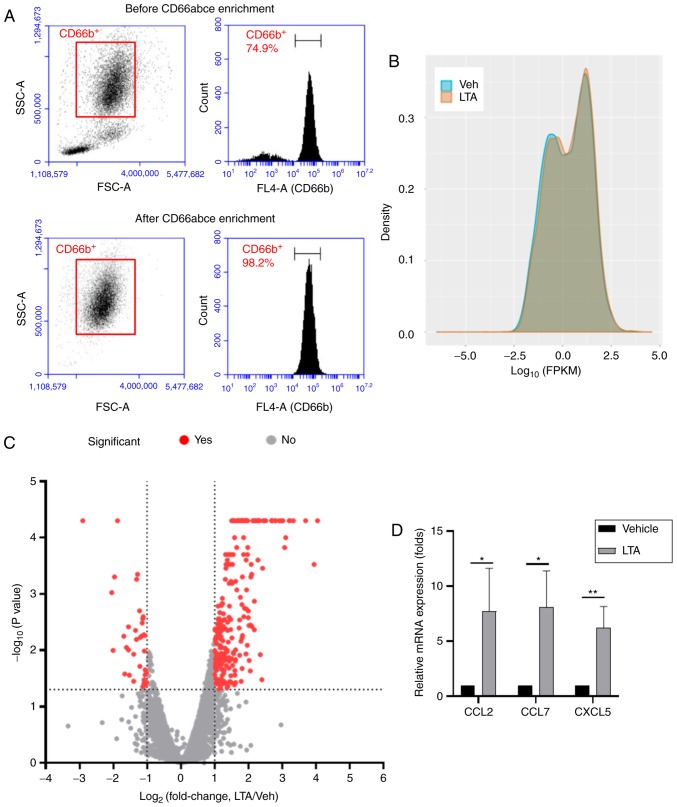

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (IRB no. KMUH-IRB-20120287). A total of 10 ml venous blood was obtained from a healthy donor. The participant agreed to the use of their sample in research and signed informed consent during the period Jan 2013 to Jan 2014. Human neutrophils were separated from whole blood using CD66abce microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec GbmH), according to manufacturer's instruction. Subsequently, 3×107 isolated neutrophils were cultured in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin G, 100 µg/ml streptomycin and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin B (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), and 1 µg/ml of LTA (from S. aureus; LTA group; cat. no. L2515; Sigma-Aldrich; Merck KgaA) or double distilled water (vehicle group) in 5% CO2 air atmosphere at 37°C for 16 h. Neutrophils were collected for RNA isolation. The purity of isolated CD66abce+ cells was evaluated via flow cytometry. Cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-human CD66b (1:20; cat. no. 561645; BD Pharmingen), according to manufacturer's instructions. The cells were then washed and analyzed using a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer with BD Accuri C6 software version 1.0.264.21 (BD Biosciences).

RNA isolation

Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol® reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) according to the supplier's protocol. Purified RNA was quantified using a ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and the quality was confirmed using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and an RNA 6000 Pico LabChip RNA (Agilent Technologies, Inc.). The RNA integrity number (RIN) resulting from the Agilent Bioanalyzer was 8.3 for the LTA-stimulated cells and 7.6 for the vehicle-stimulated cells. The quality report is shown in Fig. S1.

Library preparation, sequencing, alignment and differential expression analysis

Sequencing for mRNA and miRNA was commercially performed by Welgene Biotech Co., Ltd. All RNA sample preparation procedures were carried out according to the official Illumina protocol (Illumina, Inc.). For mRNA sequencing, Agilent's SureSelect Strand-Specific RNA Library Preparation kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) was used for library construction, followed by AMPure XP Beads (Agilent Technologies, Inc.) size selection. The sequence was directly determined via Illumina's sequencing-by-synthesis technology. Sequencing data were generated by Welgene's pipeline based on Illumina's base-calling program bcl2fastq v2.2.0. For miRNA sequencing, samples were prepared using the TruSeq™ miRNA Library kit (Illumina, Inc.), following the supplier's guide. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina instrument (75-cycle single-end read; 75SE) and miRNA sequencing data was processed using the Illumina software BCL2FASTQ v2.20. Sequence Quality Trimming, performed by Trimmomatic version 0.36 (22). HISAT2 was used for mRNA alignment (23) and miRDeep2 was used for miRNA alignment (24). The expression levels were normalized by calculating fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM). Differential expression analysis was performed via Cuffdiff (Cufflinks 2.2.1) (25). P-value was calculated by Cuffdiff with non-grouped sample using the 'blind' method, in which all samples are treated as replicates of a single global 'condition' and used to build one model (25).

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Isolated cells (5×105) were seeded into several wells of a 24-well plate and treated with vehicle or 1 µg/ml LTA for 16 h. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Equal amount of total RNA was reverse transcribed via the PrimeScript RT reagent kit (Clontech Laboratories, Inc.). qPCR was performed with SYBR-Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) on a Real-Time PCR system (QuantStudio 3D Digital PCR System; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The thermocycling conditions were: 20 sec at 95°C, followed by 40 amplification cycles of 95°C for 3 sec and 60°C for 30 sec. The primers were as follows: Human chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL) 2, forward 5′-TCTGTGCCTGCTGCTCATAG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGGAATCCTGAACCCACTTC-3′; human CCL7, forward 5′-ACCACCAGTAGCCACTGTCC-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGGGTTTTCTTGTCCAGGT-3′; human C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 5 (CXCL5), forward 5′-TGTTTACAGACCACGCAAGG-3′ and reverse 5′-GGGGCTTCTGGATCAAGAC-3′; and human GAPDH, forward 5′-GAGTCAACGGATTTGGTCGT-3′ and reverse 5′-TTGATTTTGGAGGGATCTCG-3′. The relative mRNA expression levels were normalized to the GAPDH expression and calculated using the 2−∆∆Cq method (26).

Gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes and miRNAs

The criteria of differential mRNA expression were set at fold change ≥2.0, FPKM >0.8 and P-value <0.05. For determining the function of LTA-affected genes, the biological process of GO (GOTERM_BP_ALL) analysis and Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis were performed via DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/home.jsp) (27,28). In addition, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA; http://www.broad.mit.edu/gsea/) (29,30) was performed using the GO biological processes database c5.bp.v6.2. The criteria of differential miRNA expression were set at fold change ≥2.0 and reads per million (RPM) >1. GO analysis of miRNA was performed via the GSEA method of miRNA Enrichment Analysis and Annotation Tool (miEAA; https://ccb-compute2.cs.uni-saar-land.de/mieaa_tool/) (31).

Interaction between miRNA and mRNA

To predict the miRNA-targeted mRNAs, the Funrich software version 3.1.3 (32) and miRDB 6.0 (miRNAs with Target Score >90 were selected) were used (33). The miRNA target genes were determined using two databases: TargetScan 7.2 (http://www.targetscan.org/vert_72/) (34) and miRTarBase 7.0 (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/php/index.php) (35). The network was drawn by using stringApp 1.4.1 plugin in Cytoscape software 3.7.1 (36,37).

Statistical analysis

The Venn diagram was drawn via the website http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/Venn/, accessed on 22 January 2019. The statistical analysis associated with the Venn diagram was performed via the website http://nemates.org/MA/progs/overlap_stats.html. The number of genes in the genome was set to 1,917 miRNAs according to the latest information of miRBase. For GSEA, P-values <0.01 and false discovery rate (FDR) <25% were considered significant. For GSEA of miRNAs P-values <0.05 were considered significant. All other graphs were produced in GraphPad Prism 8 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The Student's t-test was used for analysis of differences between the vehicle and LTA-treated groups, using GraphPad Prism 8. P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Distribution of mRNA expression in human neutrophils following LTA stimulation

Previous publications have reported that stimulation with 0.1-10 µg/ml of S. aureus LTA induced the release of cytokines, such as IL-8 and TNF-α, in human monocytes within 1-6 h (38,39). In addition, the gene expression profile of the human monocyte cell line THP-1 following stimulation with 25 µg/ml LTA for 6 h was detected via microarray analysis (40). The results indicated that genes involved in inflammatory responses, cell adhesion, cytokines and chemokines were upregulated following S. aureus LTA stimulation (40). In the present study, to investigate the mRNA and miRNA expression changes in human neutrophils, human CD66abce+ cells were enriched from peripheral blood obtained from a healthy donor. In peripheral blood, the majority of the enriched CD66abce+ cells are considered neutrophils (41,42). The purity of the CD66acbe+ cells following enrichment was >98%, as evidenced by flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 1A). Because 1 µg/ml of LTA stimulation has been shown to be sufficient to activate signaling downstream of TLR2 in immune cells (43), and the gene expression profile of LTA-stimulated neutrophils has not been investigated, the isolated human CD66abce+ cells were stimulated with 1 µg/ml LTA from S. aureus (LTA group) or vehicle control (ddH2O; Veh group) for 16 h and then the total RNA was extracted. Quality assessment of the RNA sequencing analysis is shown in Figs. S2 and S3, reporting high scores in per-base sequence quality and per-sequence quality in both groups. The mapped reads for both RNA and small RNA sequencing are listed in Table SI. The expression was normalized in FPKM mapped reads. The distribution of the FPKM values of the two samples was presented in a density plot (Fig. 1B). The results suggested that the FPKM distribution was similar in the two samples. To further investigate the differential gene expression in response to LTA stimulation, the distribution of differentially expressed genes between the two samples was plotted in a volcano plot (Fig. 1C). Genes with fold change ≥2.0 (log2 fold change >1 or <-1), FPKM >0.8 and P-value <0.05 (-log10 P-value >1.3) were considered as significant. According to these criteria, 290 significant differentially expressed genes were selected for subsequent analysis (the full gene list is presented in Table SII). Furthermore, the mRNA expression changes of CCL2, CCL7 and CXCL5 were validated by RT-qPCR (Fig. 1D), confirming that these genes were demonstrate to be significantly upregulated following LTA stimulation by both the RT-qPCR and the RNA sequencing analyses.

Figure 1.

Distribution of mRNA expression in LTA and vehicle-stimulated neutrophils. (A) Purity of enriched human CD66abce+ cells. Upper panel and lower panel reveal the total cell population (left) and the CD66b expression (right) before and after CD66abce enrichment, respectively. (B) Density plot of the distributions of FPKM scores across the two samples. (C) Volcano plot (log2 fold-change vs. log10 P-value) of upregulated and downregulated genes shows the differential mRNA distribution for the sample pair. The dash line indicated the criteria of significant genes. (D) Reverse transcription-qPCR analysis of the CCL2, CCL7 and CXCL5 mRNA expression levels. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Three replicates were performed. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. vehicle group. LTA, lipoteichoic acid; FPKM, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million; FSC, forward scatter; SSC, side scatter; Veh, vehicle.

Evaluating the function of LTA-affected genes

Previous studies have suggested that LTA stimulation results in induction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, cell migration and antimicrobial responses in immune cells. To further investigate the function of the differential gene expression in response to LTA stimulation, the 290 selected genes were subjected to GO analysis for biological processes and KEGG pathway analysis via the DAVID gene functional classification tool. Results with P-values <0.001 and FDR <25% were considered as significantly enriched biological processes and KEGG pathways. The results revealed that >200 biological processes and 4 KEGG pathways were enriched. The gene list in each enriched biological process and KEGG pathway is present in Tables SIII and SIV. The top 20 most significant enriched biological processes are presented in Table I. These biological processes, including positive regulation of cell migration and motility, positive regulation of cellular component movement, response to external stimulus, defense responses, inflammatory responses and cell surface receptor signaling pathway, were similar with the LTA-induced responses of neutrophils in previous studies (11-14). The results of KEGG pathway analysis are presented Table II.

Table I.

GO analysis for biological processes via DAVID gene functional classification tool.

| GO ID | GO term | Enrichment | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0030335 | Positive regulation of cell migration | 6.237193 | 6.81×10−19 | 1.29×10−15 |

| GO:0051272 | Positive regulation of cellular component movement | 6.020298 | 7.20×10−19 | 1.36×10−15 |

| GO:2000147 | Positive regulation of cell motility | 6.023695 | 2.17×10−18 | 4.11×10−15 |

| GO:0030334 | Regulation of cell migration | 4.543111 | 2.72×10−18 | 5.16×10−15 |

| GO:0040017 | Positive regulation of locomotion | 5.838131 | 6.11×10−18 | 1.16×10−14 |

| GO:2000145 | Regulation of cell motility | 4.316392 | 8.70×10−18 | 1.65×10−14 |

| GO:0006954 | Inflammatory response | 4.580108 | 2.92×10−17 | 5.54×10−14 |

| GO:0040012 | Regulation of locomotion | 4.136543 | 4.70×10−17 | 8.90×10−14 |

| GO:0006952 | Defense response | 2.989709 | 4.85×10−17 | 9.19×10−14 |

| GO:0051270 | Regulation of cellular component movement | 4.042019 | 5.25×10−17 | 9.93×10−14 |

| GO:0016477 | Cell migration | 3.285506 | 3.73×10−16 | 6.33×10−13 |

| GO:0070887 | Cellular response to chemical stimulus | 2.301508 | 9.52×10−16 | 1.89×10−12 |

| GO:0006950 | Response to stress | 2.010083 | 2.23×10−15 | 4.21×10−12 |

| GO:0009605 | Response to external stimulus | 2.502035 | 4.33×10−15 | 8.19×10−12 |

| GO:0051674 | Localization of cell | 3.022336 | 4.56×10−15 | 8.62×10−12 |

| GO:0048870 | Cell motility | 3.022336 | 4.56×10−15 | 8.62×10−12 |

| GO:0007166 | Cell surface receptor signaling pathway | 2.234817 | 1.38×10−14 | 2.61×10−11 |

| GO:0032879 | Regulation of localization | 2.280856 | 3.45×10−14 | 6.54×10−11 |

| GO:0010033 | Response to organic substance | 2.159601 | 4.98×10−14 | 9.42×10−11 |

| GO:0048583 | Regulation of response to stimulus | 1.961424 | 6.01×10−14 | 1.14×10−10 |

GO, Gene Ontology; FDR, false discovery rate.

Table II.

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes pathway analysis via DAVID gene functional classification tool.

| Path ID | Path name | Enrichment | P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa04060 | Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 4.2657 | 2.88×10−8 | 3.62×10−5 |

| hsa05205 | Proteoglycans in cancer | 3.5337 | 7.46×10−5 | 0.0938 |

| hsa04015 | Rap1 signaling pathway | 3.3655 | 1.26×10−4 | 0.1585 |

| hsa04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 3.5464 | 1.38×10−4 | 0.1738 |

FDR, false discovery rate.

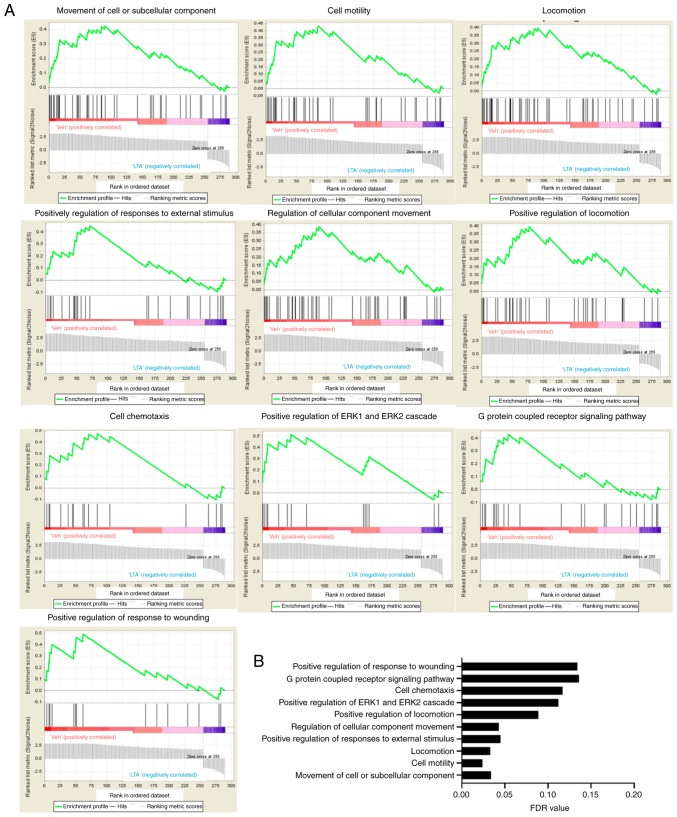

The functions of the 290 genes were also analyzed by GSEA. The results revealed that 53 gene sets were significant at FDR <25% and 16 gene sets were significant at nominal P-value <1%. According to the FDR value, the top 10 most significant gene sets are presented in Fig. 2. The gene sets identified by GSEA analysis were similar with those from GO analysis, including cell motility, locomotion, cellular component movement, G protein-coupled receptor signaling and positive regulation of ERK1 and ERK2 cascade, were shown. Upregulation of cell migration and granule degranulation in LTA-stimulated neutrophils has been reported in previous studies (11-14). By contrast, upregulation of cytokines, such as IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α and G-CSF, was not observed in the present results; the expression changes of those four genes were <2-fold in the present RNA sequencing results (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Gene ontology analysis for biological processes via Gene Set Enrichment Analysis. (A) Histograms of selected top enriched signatures. (B) FDR values of the top ten significantly enriched-biological processes. FDR, false discovery rate.

Evaluating the function of LTA-affected miRNAs

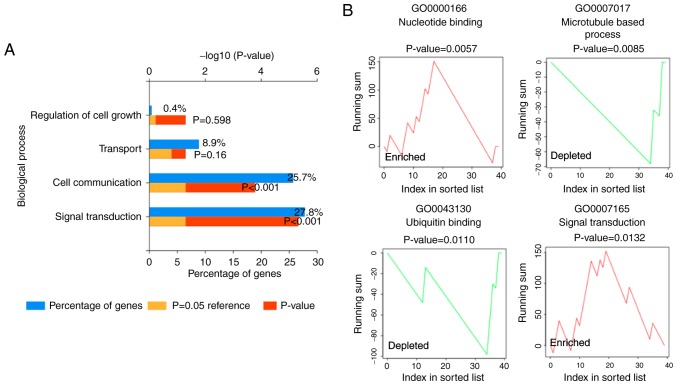

The miRNA expression was also determined via miRNA sequencing in the present study. miRNA expression was considered significantly changed based on fold change ≥2.0 and reads per million (RPM) >1. Compared to vehicle-stimulated neutrophils, 38 miRNAs, including 36 downregulated miRNAs and 2 upregulated miRNAs, were identified as significantly differentially expressed in LTA-stimulated neutrophils. The list of the 38 significant differentially expressed miRNAs is presented in Table SV. The miRNA enrichment analysis was determined via Funrich software according to biological process. The Funrich analysis suggested that these miRNAs were signifi-cantly involved in signal transduction and cell communication (P<0.05; Fig. 3A). In addition, the GSEA-like method of gene ontology analysis was performed via the miEAA website, which is a miRNA enrichment analysis and annotation web-based application. Pathways such as nucleotide binding, signal transduction, cell cortex, protein autophosphorylation, transcription corepressor and energy reserve metabolic process were enriched in the LTA-stimulated neutrophils (Fig. 3B and Table III). Pathways such as microtubule-based process, cytoskeleton-dependent intracellular transport, protein polymerization and ubiquitin binding were suppressed (Fig. 3B and Table III). Signal transduction was the only enriched biological process observed with both the analysis methods.

Figure 3.

Gene ontology analysis of miRNAs. (A) Enriched biological pathways generated by the Funrich software analysis. (B) Enriched biological pathways generated by the miEAA website. Two enriched (red) and two depleted (green) biological pathways are shown.

Table III.

GO analysis of miRNA via miEAA website.

| GO ID | Path name | Enrichment | P-value | miRNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO0000166 | Nucleotide binding | Enriched | 0.0057 | hsa-miR-10a-3p; hsa-miR-193a-3p; hsa-miR-22-5p; hsa-miR-331-5p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-34c-5p; hsa-miR-362-5p; hsa-miR-378a-5p; hsa-miR-940 |

| GO0007017 | Microtubule based process | Depleted | 0.0085 | hsa-miR-708-5p; hsa-miR-940 |

| GO0030705 | Cytoskeleton dependent | Depleted | 0.0085 | hsa-miR-708-5p; hsa-miR-940 |

| intracellular transport | ||||

| GO0051258 | Protein polymerization | Depleted | 0.0085 | hsa-miR-708-5p; hsa-miR-940 |

| GO0043130 | Ubiquitin binding | Depleted | 0.0110 | hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-708-5p; hsa-miR-708-3p; hsa-miR-940 |

| GO0007165 | Signal transduction | Enriched | 0.0132 | hsa-miR-10a-3p; hsa-miR-1271-5p; hsa-miR-22-5p; hsa-miR-31-3p; hsa-miR-331-5p; hsa-miR-337-3p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-34c-5p; hsa-miR-378a-5p; hsa-miR-3928-3p; hsa-miR-625-5p; hsa-miR-708-5p |

| GO0005938 | Cell cortex | Enriched | 0.0149 | hsa-miR-193a-3p; hsa-miR-31-3p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-34c-5p |

| GO0046777 | Protein autophosphorylation | Enriched | 0.0149 | hsa-miR-193a-3p; hsa-miR-31-3p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-34c-5p |

| GO0003714 | Transcription corepressor activity | Enriched | 0.0176 | hsa-miR-193a-3p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-34c-5p; hsa-miR-362-3p; hsa-miR-378a-5p |

| GO0006112 | Energy reserve metabolic process | Enriched | 0.0176 | hsa-miR-10a-3p; hsa-miR-337-3p; hsa-miR-34a-5p; hsa-miR-34c-5p; hsa-miR-378a-5p |

GO, Gene Ontology; miRNA, microRNA.

Evaluating the potential interaction between LTA-affected miRNA and genes

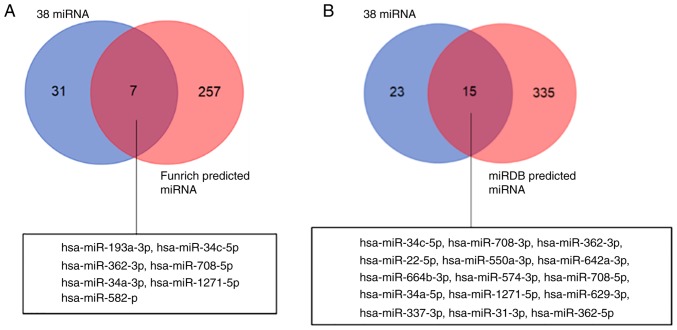

To further identify whether the 38 miRNAs may interact with the 290 LTA-affected genes, the Funrich software and the miRDB website were used. The analysis results of the Funrich software and the miRDB website, respectively, indicated 264 miRNAs and 350 miRNAs might target to 342 genes. Seven and 15 shared miRNAs were respectively identified between the 38 miRNAs and 264 Funrich-predicted miRNAs (Fig. 4A), and 38 miRNAs and 350 miRDB-predicted miRNAs (Fig. 4B). The results further revealed that 5 miRNAs, hsa-miR-1271-5p, hsa-miR-708-5p, hsa-miR-362-3p, hsa-miR-34c-5p and hsa-miR-34a-5p, were observed in both analyses. The potential interaction between 5 miRNAs and 290 genes was further validated by Targetscan and miRTarBase database analyses. The interaction between the 4 miRNAs and the 5 genes is presented in Table IV. These genes were involved in various biological processes. For example, MET proto-oncogene (MET) and heparin binding EGF like growth factor (HBEGF) were involved in positive regulation of cell migration and cellular component movement, calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit β3 (CACNB3) was involved in immune system process and immune response, tensin 3 (TNS3) was involved in cell migration and motility, and tweety family member 3 (TTYH3) involved in localization (Table SII). The interactions between hsa-miR-34a-5p, hsa-miR-34c-5p and MET, hsa-miR-34a-5p and CACNB3, and their biological function have been validated in other publications (44-52).

Figure 4.

The potential targeted genes of miRNAs. The results of miRNA sequencing revealed that 38 miRNAs exhibited differential expression between lipoteichoic acid and vehicle-stimulated neutrophils. (A) Venn diagram showing that the 7 miRNAs identified in the Funrich software predicted 264 miRNAs (red circle) and 38 miRNAs (blue circle; P=0.262). (B) Venn diagram showing that the 15 miRNAs in the miRDB website predicted 350 miRNAs (red circle) and 38 miRNAs (blue circle; P=0.002).

Table IV.

Target genes of miRNAs.

| miRNA | Fold change of miRNAa | Gene symbol | Fold change of mRNAa | TargetScan | miRTarBase | (Refs.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-34a-5p | −2.18 | MET | 2.23 | Yes | Yes | (40,46-48) |

| hsa-miR-34a-5p | −2.18 | CACNB3 | 0.49 | Yes | Yes | (45) |

| hsa-miR-34c-5p | −2.11 | MET | 2.23 | Yes | Yes | (40-44) |

| hsa-miR-708-5p | −2.07 | TNS3 | 6.41 | Yes | No | |

| hsa-miR-1271-5p | −2.98 | TTYH3 | 2.70 | Yes | No | |

| hsa-miR-1271-5p | −2.98 | TNS3 | 6.41 | Yes | No | |

| hsa-miR-1271-5p | −2.98 | HBEGF | 3.78 | Yes | No |

Fold change in lipoteichoic acid-treated group vs. vehicle group. MET, MET proto-oncogene; CACNB3, calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit β3; TNS3, tensin 3; TTYH3, tweety family member 3; HBEGF, heparin binding EGF like growth factor.

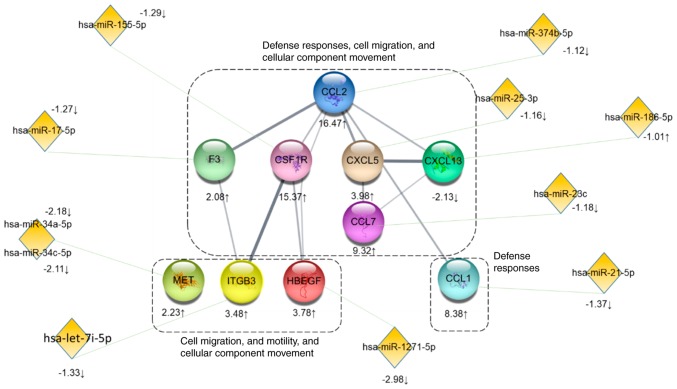

Although interactions were predicted between the 4 miRNAs and the 5 genes, potential interactions between most of genes and miRNAs identified in the present study were not identified. Because LTA stimulation induces defense responses, further analysis focused on the genes and miRNAs involved in the biological processes of positive regulation of cell migration and motility and cellular component movement (Fig. 5). The results revealed that various genes with >2-fold changes may also interact with miRNAs with <2-fold changes. Further experimental evidence will be necessary to confirm whether miRNA-mRNA interactions may be important for regulation of LTA-induced signaling pathways.

Figure 5.

Interactions of miRNAs and genes. The genes involved in the biological processes 'defense responses', 'positive regulation of cell migration and mobility' and 'positive regulation of cellular component movement' were selected and potential targeted miRNAs were predicted by the Funrich software and the miRDB website (target score >90). The circles represent genes and the diamonds represent miRNAs. The numbers beside the genes and the miRNAs indicate fold changes. The green lines linking between genes and miRNAs indicate potential interactions.

Discussion

LTA is a cell wall polymer in Gram-positive bacteria and a risk factor for sepsis. Based on their chemical structures, LTAs can be grouped into different types. Type I LTA is present in bacteria including S. aureus, Listeria monocytogenes and Bacillus subtilis (53). Prior publications have reported that LTAs from S. aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae (type IV) can induce secretion of IL-8, IL-6, IL-1β and TNF-α in monocytes and macrophages (54,55). Although the half-life of circulating neutrophils is only 6-8 h (56), a previous study demonstrated that the production of IL-1β, IL-8 and TNF-α was significantly induced when human neutrophils were incubated with 10 µg/ml S. aureus LTA for 16 and 24 h (14). In addition, Hattar et al (14) demonstrated that the protein levels of IL-8 were induced by stimulation with 1, 5 and 10 µg/ml LTA after 16 h of incubation. In the present study, the results of RNA sequencing provided a whole molecular picture of LTA-induced gene expression, including a trend for increased expression of IL-8, IL-6, TNF-α and G-CSF (although <2-fold), and 290 genes with significantly differential expression in human neutrophils following 16 h stimulation with 1 µg/ml LTA.

LTA-affected genes have been reported in several types of cells in previous studies. Two previously published datasets in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, GSE15512 and GSE21188, include results from microarray analysis determining the gene expression of an LTA-treated monocyte cell line (25 µg/ml LTA was used to stimulate THP-1 cells for 6 h) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs; 10 µg/ml LTA was used to stimulate PBMCs for 7 h), respectively. Although the dose and duration of the LTA stimulations were not identical, the expression of inflammatory genes in the present study was compared with that in both datasets. In general, the upregulated expression of genes including IL-1β, IL-6, CXCL8, CCL2 and CCL20 were similar in the present study and both datasets. Notably, LTA stimulation in THP-1 cells induced more significant changes in gene expression compared with LTA stimulation in PBMCs and in the present study. Based on 20 shared inflammatory-associated genes among the present study and the two public databases, the gene expression profile in the present study was moderately positively correlated with that in the public databases. These findings might suggest that genes can be affected differently by the various doses of LTA in a short (6-7 h) and long (16 h) incubation period.

The results of mRNA sequencing revealed various biological processes and signaling pathways that were enriched following LTA stimulation. In Table I, positively regulation of cell migration, cell motility and locomotion, as well as defense responses and inflammatory responses, were observed. Additionally, KEGG pathway analysis revealed that 4 pathways were enriched, including cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and chemokine signaling pathway (Table II). A previous study demonstrated that B. subtilis LTA increases the secretion of CCL2 and CXCL10 in odontoblasts (57). To the best of our knowledge, the induction of chemokines is not fully elucidated in neutrophils. In odontoblasts, fibroblasts and pulpal cells, activation of TLR2, TLR3 and TLR4 pathways induces the production of several chemokines, such as CCL2, CCL7, IL-8 (CXCL8) and CXCL10 (58,59). In human lymphatic endothelium cells, LTA stimulation induces the expression of CCL2, CCL5, CXCL1, CXCL3, CXCL5, CXCL6 and IL-8 (CXCL8) through a TLR2-depedent mechanism (60). The present study revealed upregulation of CCL2, CCL7 and CXCL5 in LTA-stimulated neutrophils (Fig. 5). In addition, the expression of TLR2 was also upregulated (by 2.02-fold) following LTA stimulation. Therefore, it is supposed that TLR2 might be also essential for chemokine signaling pathway in human neutrophils. The role of TLR2 in the regulation of the chemokine signaling pathway, the function of proteoglycans, and the role of the Rap1 signaling pathway in neutrophils, will be further investigated in subsequent studies.

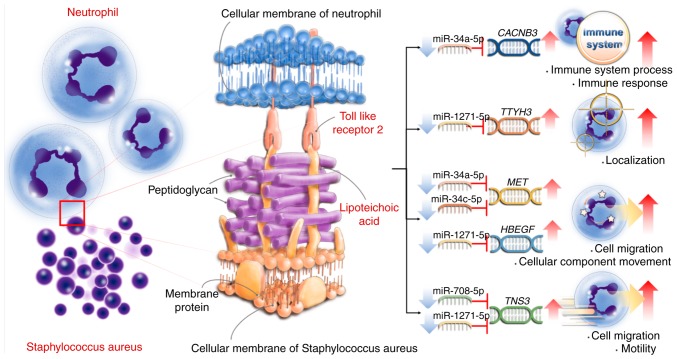

The effect of LTA stimulation on the miRNA expression remained unclear. In a mouse model, Staphylococcus epidermidis LTA induced the expression of miR-143 via TLR2 signaling (61). When mice were exposed to LTA from B. subtilis, S. faecalis and S. aureus, the expression of miR-451, miR-668, miR-1902 and miR-1904 was induced in whole blood and serum (62). The present study found 38 miRNAs with >2-fold change in expression following LTA stimulation; the majority of these 38 miRNAs were novel and not reported in previous publications. However, miR-143, miR-451, miR-668, miR-1902 and miR-1904 were not significantly altered in the human LTA-stimulated neutrophils in the present study. Because a miRNA can target many genes (63), GO analysis of the 38 miRNAs was performed (Table III). However, the function of these miRNAs and the regulatory mechanism of these enriched biological processes and LTA-mediated responses remained unknown. Therefore, the miRNA-target gene interactions were further investigated via multiple bioin-formatic tools. The results revealed potential novel interactions between hsa-miR-34a-5p, hsa-miR-34c-5p, hsa-miR-708-5p hsa-miR-1271-5p and MET, HBEGF, CACNB3, TNS3 and TTYH3, and that these interactions may regulate cell migration and motility, cellular component movement, immune system process and immune response. Although these findings were interesting, there are some limitations in the current study. Firstly, only one sample from one donor was analyzed in the present study. Furthermore, the interactions between miRNA and mRNA were not experimentally confirmed. The proposed interactions require further validation through functional experiments in the future. The summary of the present findings is presented in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Schematic summary of proposed miRNA-target gene interactions and biological processes in human neutrophils following lipoteichoic acid stimulation. CACNB3, calcium voltage-gated channel auxiliary subunit β3; TTYH3, tweety family member 3; MET, MET proto-oncogene; HBEGF, heparin binding EGF like growth factor; TNS3, tensin 3.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to provide comprehensive information about transcriptome analysis of LTA-stimulated human neutrophils. A total of 290 mRNAs and 38 miRNAs which were significantly altered by 16 h-stimulation of S. aureus LTA in human neutrophils were identified. Furthermore, bioinformatic analysis proposed novel interactions between 4 miRNAs and 5 target genes. These findings may provide new insights of the LTA-mediated effect on peripheral neutrophils and the innate immune responses in a healthy person.

Supplementary Data

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Center for Research Resources and Development of Kaohsiung Medical University.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology (grant nos. MOST 108-2314-B-037-097-MY3, 107-2320-B-037-011-MY3 and 106-2320-B-037-029-MY3), the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (grant nos. KMUH107-7M36, KMUH107-7R81, KMUHS10701 and KMUHS10712), the Kaohsiung Medical University Research Center Grant (grant no. KMU-TC108A04) and the Kaohsiung Medical University (grant nos. KMU-DK108003 and KMU-Q108005).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

MY and MT conceived and designed the experiments. IY, KL and SJ prepared the materials and performed the experiments. MY, IY, CL, MT and PK analyzed the data. MY wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (IRB no. KMUH-IRB-20120287). Signed informed consent was obtained.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Brubaker SW, Bonham KS, Zanoni I, Kagan JC. Innate immune pattern recognition: A cell biological perspective. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33:257–290. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032414-112240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev. 22:240–273. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00046-08. Table of Contents, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kawasaki T, Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu YC, Yeh WC, Ohashi PS. LPS/TLR4 signal transduction pathway. Cytokine. 2008;42:145–151. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park BS, Lee JO. Recognition of lipopolysaccharide pattern by TLR4 complexes. Exp Mol Med. 2013;45:e66. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seo HS, Michalek SM, Nahm MH. Lipoteichoic acid is important in innate immune responses to gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun. 2008;76:206–213. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01140-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning CJ. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17406–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira-Nascimento L, Massari P, Wetzler LM. The role of TLR2 in infection and immunity. Front Immunol. 2012;3:79. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kengatharan KM, De Kimpe S, Robson C, Foster SJ, Thiemermann C. Mechanism of gram-positive shock: Identification of peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid moieties essential in the induction of nitric oxide synthase, shock, and multiple organ failure. J Exp Med. 1998;188:305–315. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurt-Jones EA, Mandell L, Whitney C, Padgett A, Gosselin K, Newburger PE, Finberg RW. Role of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) in neutrophil activation: GM-CSF enhances TLR2 expression and TLR2-mediated interleukin 8 responses in neutrophils. Blood. 2002;100:1860–1868. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lotz S, Aga E, Wilde I, van Zandbergen G, Hartung T, Solbach W, Laskay T. Highly purified lipoteichoic acid activates neutrophil granulocytes and delays their spontaneous apoptosis via CD14 and TLR2. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;75:467–477. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0803360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ginsburg I. Role of lipoteichoic acid in infection and inflammation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:171–179. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(02)00226-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathan C. Neutrophils and immunity: Challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:173–182. doi: 10.1038/nri1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hattar K, Grandel U, Moeller A, Fink L, Iglhaut J, Hartung T, Morath S, Seeger W, Grimminger F, Sibelius U. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) from Staphylococcus aureus stimulates human neutrophil cytokine release by a CD14-dependent, Toll-like-receptor-independent mechanism: Autocrine role of tumor necrosis factor-[alpha] in mediating LTA-induced interleukin-8 generation. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:835–841. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000202204.01230.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drury RE, O'Connor D, Pollard AJ. The clinical application of MicroRNAs in infectious disease. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1182. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu H, Lei C, He Q, Pan Z, Xiao D, Tao Y. Nuclear functions of mammalian MicroRNAs in gene regulation, immunity and cancer. Mol Cancer. 2018;17:64. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0765-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen Z, Xu L, Chen X, Xu W, Yin Z, Gao X, Xiong S. Autoantibody induction by DNA-containing immune complexes requires HMGB1 with the TLR2/microRNA-155 pathway. J Immunol. 2013;190:5411–5422. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yao H, Zhang H, Lan K, Wang H, Su Y, Li D, Song Z, Cui F, Yin Y, Zhang X. Purified Streptococcus pneumoniae endo-peptidase O (PepO) enhances particle uptake by macrophages in a toll-like receptor 2- and miR-155-dependent manner. Infect Immun. 2017;85:e01012–e01016. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01012-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xu H, Wu Y, Li L, Yuan W, Zhang D, Yan Q, Guo Z, Huang W. MiR-344b1-3p targets TLR2 and negatively regulates TLR2 signaling pathway. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:627–638. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S120415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Landais I, Pelton C, Streblow D, DeFilippis V, McWeeney S, Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus miR-UL112-3p targets TLR2 and modulates the TLR2/IRAK1/NFκB signaling pathway. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004881. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quinn EM, Wang JH, O'Callaghan G, Redmond HP. MicroRNA-146a is upregulated by and negatively regulates TLR2 signaling. PLoS One. 2013;8:e62232. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: A fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357–360. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedlander MR, Mackowiak SD, Li N, Chen W, Rajewsky N. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:37–52. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mootha VK, Lindgren CM, Eriksson KF, Subramanian A, Sihag S, Lehar J, Puigserver P, Carlsson E, Ridderstråle M, Laurila E, et al. PGC-1alpha-responsive genes involved in oxidative phosphorylation are coordinately downregulated in human diabetes. Nat Genet. 2003;34:267–273. doi: 10.1038/ng1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Backes C, Khaleeq QT, Meese E, Keller A. miEAA: microRNA enrichment analysis and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:W110–W116. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pathan M, Keerthikumar S, Ang CS, Gangoda L, Quek CY, Williamson NA, Mouradov D, Sieber OM, Simpson RJ, Salim A, et al. FunRich: An open access standalone functional enrichment and interaction network analysis tool. Proteomics. 2015;15:2597–2601. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201400515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu W, Wang X. Prediction of functional microRNA targets by integrative modeling of microRNA binding and target expression data. Genome Biol. 2019;20:18. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1629-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia DM, Baek D, Shin C, Bell GW, Grimson A, Bartel DP. Weak seed-pairing stability and high target-site abundance decrease the proficiency of lsy-6 and other microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:1139–1146. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chou CH, Shrestha S, Yang CD, Chang NW, Lin YL, Liao KW, Huang WC, Sun TH, Tu SJ, Lee WH, et al. miRTarBase update 2018: A resource for experimentally validated microRNA-target interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D296–D302. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, Baliga NS, Wang JT, Ramage D, Amin N, Schwikowski B, Ideker T. Cytoscape: A software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Gorodkin J, Jensen LJ. Cytoscape stringApp: Network analysis and visualization of proteomics data. J Proteome Res. 2019;18:623–632. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Finney SJ, Leaver SK, Evans TW, Burke-Gaffney A. Differences in lipopolysaccharide- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cytokine/chemokine expression. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38:324–332. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2444-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schröder NW, Morath S, Alexander C, Hamann L, Hartung T, Zähringer U, Göbel UB, Weber JR, Schumann RR. Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus activates immune cells via Toll-like receptor (TLR)-2, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), and CD14, whereas TLR-4 and MD-2 are not involved. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15587–15594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212829200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zeng RZ, Kim HG, Kim NR, Gim MG, Ko MY, Lee SY, Kim CM, Chung DK. Differential gene expression profiles in human THP-1 monocytes treated with Lactobacillus plantarum or Staphylococcus aureus lipoteichoic acid. J Korean Soc Appl Bi. 2011;54:763–770. doi: 10.1007/BF03253157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharma S, Davis RE, Srivastva S, Nylen S, Sundar S, Wilson ME. A subset of neutrophils expressing markers of antigen-presenting cells in human visceral leishmaniasis. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1531–1538. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiw394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X, Li SJ, Ojcius DM, Sun AH, Hu WL, Lin X, Yan J. Mononuclear-macrophages but not neutrophils act as major infiltrating anti-leptospiral phagocytes during leptospirosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0181014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Long EM, Millen B, Kubes P, Robbins SM. Lipoteichoic acid induces unique inflammatory responses when compared to other toll-like receptor 2 ligands. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hermeking H. The miR-34 family in cancer and apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2010;17:193–199. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2009.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai KM, Bao XL, Kong XH, Jinag W, Mao MR, Chu JS, Huang YJ, Zhao XJ. Hsa-miR-34c suppresses growth and invasion of human laryngeal carcinoma cells via targeting c-Met. Int J Mol Med. 2010;25:565–571. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong F, Lou D. MicroRNA-34b/c suppresses uveal melanoma cell proliferation and migration through multiple targets. Mol Vis. 2012;18:537–546. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagman Z, Haflidadottir BS, Ansari M, Persson M, Bjartell A, Edsjö A, Ceder Y. The tumour suppressor miR-34c targets MET in prostate cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:1271–1278. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang F, Lu J, Peng X, Wang J, Liu X, Chen X, Jiang Y, Li X, Zhang B. Integrated analysis of microRNA regulatory network in nasopharyngeal carcinoma with deep sequencing. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2016;35:17. doi: 10.1186/s13046-016-0292-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bavamian S, Mellios N, Lalonde J, Fass DM, Wang J, Sheridan SD, Madison JM, Zhou F, Rueckert EH, Barker D, et al. Dysregulation of miR-34a links neuronal development to genetic risk factors for bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2015;20:573–584. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan D, Zhou X, Chen X, Hu DN, Dong XD, Wang J, Lu F, Tu L, Qu J. MicroRNA-34a inhibits uveal melanoma cell proliferation and migration through downregulation of c-Met. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:1559–1565. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guessous Li Y, Zhang F, Dipierro Y, Kefas C, Johnson B, Marcinkiewicz E, Jiang L, Yang J, Schmittgen YTD, et al. MicroRNA-34a inhibits glioblastoma growth by targeting multiple oncogenes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7569–7576. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan K, Gao J, Yang T, Ma Q, Qiu X, Fan Q, Ma B. MicroRNA-34a inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of osteosarcoma cells both in vitro and in vivo. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Percy MG, Grundling A. Lipoteichoic acid synthesis and function in gram-positive bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2014;68:81–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-091213-112949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Standiford TJ, Arenberg DA, Danforth JM, Kunkel SL, VanOtteren GM, Strieter RM. Lipoteichoic acid induces secretion of interleukin-8 from human blood monocytes: A cellular and molecular analysis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:119–125. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.1.119-125.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mattsson E, Verhage L, Rollof J, Fleer A, Verhoef J, van Dijk H. Peptidoglycan and teichoic acid from Staphylococcus epidermidis stimulate human monocytes to release tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 beta and interleukin-6. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1993;7:281–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1993.tb00409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Summers C, Rankin SM, Condliffe AM, Singh N, Peters AM, Chilvers ER. Neutrophil kinetics in health and disease. Trends Immunol. 2010;31:318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Durand SH, Flacher V, Roméas A, Carrouel F, Colomb E, Vincent C, Magloire H, Couble ML, Bleicher F, Staquet MJ, et al. Lipoteichoic acid increases TLR and functional chemokine expression while reducing dentin formation in in vitro differentiated human odontoblasts. J Immunol. 2006;176:2880–2887. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.5.2880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park C, Lee SY, Kim HJ, Park K, Kim JS, Lee SJ. Synergy of TLR2 and H1R on Cox-2 activation in pulpal cells. J Dent Res. 2010;89:180–185. doi: 10.1177/0022034509354720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Staquet MJ, Durand SH, Colomb E, Roméas A, Vincent C, Bleicher F, Lebecque S, Farges JC. Different roles of odonto-blasts and fibroblasts in immunity. J Dent Res. 2008;87:256–261. doi: 10.1177/154405910808700304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sawa Y, Tsuruga E, Iwasawa K, Ishikawa H, Yoshida S. Leukocyte adhesion molecule and chemokine production through lipoteichoic acid recognition by toll-like receptor 2 in cultured human lymphatic endothelium. Cell Tissue Res. 2008;333:237–252. doi: 10.1007/s00441-008-0625-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xia X, Li Z, Liu K, Wu Y, Jiang D, Lai Y. Staphylococcal LTA-induced miR-143 inhibits propionibacterium acnes-mediated inflammatory response in skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:621–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2015.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hsieh CH, Yang JC, Jeng JC, Chen YC, Lu TH, Tzeng SL, Wu YC, Wu CJ, Rau CS. Circulating microRNA signatures in mice exposed to lipoteichoic acid. J Biomed Sci. 2013;20:2. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-20-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: Target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.