Abstract

The purpose of this project was to develop a multidimensional understanding of synergistic connections between food-related and emotional health in the lives of Latina immigrants using a community-engaged approach with women who participate in a social isolation support group. The domains of interest included the intersection of social isolation, depression, diabetes and food insecurity. We tested an innovative “structured dialogue” (SD) approach to integrating the domains of interest into the group dynamic. We documented key positive impacts of participation in the group on women’s everyday experiences and emotional wellbeing. We demonstrated the extent to which this approach increases women’s knowledge of food and food resources, and their self-efficacy for dealing with diabetes and food insecurity.

Keywords: Women, Hispanics/Latinos, immigrants, peer support, social isolation, depression, food insecurity, diabetes

Social isolation is a well-established health risk factor [1] and is often associated with depression and mental health problems [2,3]. Other negative outcomes include development and progression of a variety of chronic diseases [4], obesity [5], underutilization of child immunizations and pre/post natal care [6], family disruption, residential instability and stress [7], domestic violence [8,9], poor parenting outcomes [10], and even mortality [11,12]. In contrast, strong social ties have been linked with positive emotional support, material assistance, and resource knowledge that have been found to be protective factors [e.g, 13]. Immigrants, and women in particular, are at high risk for social isolation [14,15]. For immigrant women, social interaction is an important source of support for rebuilding lives in a new context, redefining or reclaiming identity(s), and maintaining the health of families [16]. However, given the realities of the immigration experience, the process of building relationships and creating or finding a social network of support is challenging.

Syndemics.

Although links have been demonstrated between social isolation, depression, and diabetes [17], diabetes and food insecurity [18–20], and food insecurity, social isolation, and depression [21–23], the holistic conceptualization of women’s health in relation these domains as synergistic is inadequate. This is not merely saying that everything is connected to everything—a common critique of holistic and synergistic approaches that attempt to understand complex, interconnected relationships. The literature and our preliminary research suggest that we need more research to appreciate the interconnected nature of these dynamics, and to reveal ways that they influence and are influenced by women’s daily life circumstances in both positive and negative ways.

As such, recognizing social isolation, depression, diabetes and food insecurity as interconnected in the lives of Latina immigrants requires that we consider both the complex, multifactorial nature of how social isolation operates through multiple “social determinant” pathways, as well as the multilevel impact on individuals, families, and the immigrant community. Merrill Singer [24] conceptualized how multiple streams of influence can come together to form a “syndemic” in which the synergistic interaction of social, environmental, economic, and political factors produce disease—often disproportionately affecting a particular group. The syndemic framework has been further elaborated by Singer and his colleagues, Claire, Bulled, Ostrach, Lerman, and Mendenhall [25–30] and was explored in a recent special edition of The Lancet [31] as a comprehensive approach for addressing health disparities. The importance of recognizing that co-occurring diseases and social conditions may not merely be comorbidities [31,28], but rather intertwined factors that have a cumulative effect [31] that is exacerbated and concentrated in certain populations as the the bio-social comes to reflect “structural violence of inequality.” [25] For populations such as Latino immigrants that are exposed to structural violence and political inequalities over which individuals have little or not power, syndemic interactions can create “biopolitical vulnerability” [28] through which external social conditions become internalized as disease. Ostrach and Singer [28] suggest that for women, social and structural factors create specific pathways of disparity that require gender-specific interventions.

A number of studies have explored health disparities among Latinas/Latinos using syndemic frameworks. For example, Gonzalez-Guarda and colleagues used syndemics for research with Latinas to study the unhealthy synergy between intimate partner violence, depression, PTSD and suicidal ideation [32]. They demonstrated that dysfunctional power dynamics inside of intimate relationships must be understood as a social determinant. In Costa Rica, Himmelgreen and colleagues [33] used syndemic theory to understand how the effects of co-occurring changes in diet, agricultural production, food security and economic development become condensed and magnified as diet-related diseases of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension.

A syndemic framework is useful for thinking about how social isolation creates toxic health problems in immigrant communities and highlights the need for holistic, culturally based and gender-specific solutions. Mendenhall’s [34] groundbreaking model of “syndemic suffering” opens our eyes to the fundamental synergistic nature of disease and social determinants in the lives of Latina immigrants as she demonstrates the connection between social distress, depression, and diabetes risk within an experiential framework of pervasive violence (physical, emotional, and structural). Although she did not forefront food or study women’s relationships to food or food insecurity, she indicated that these themes emerged in her data as an area requiring further inquiry, and food insecurity has been identified in the literature as of particular concern among immigrants.[35] Carney [36, 37] describes how for Latina immigrants, the intersectionality of “gender, race and class as axes of power and difference, and also [as] markers of citizenship/illegality” [p. 1] produce a “biopolitics of food insecurity” where relations of power are inscribed on women’s bodies as health disparities.

At the same time, Singer and colleagues [28] suggest [p. 942] that there are also “countersyndemic” factors that can be protective against syndemic disease interactions. Using a countersyndemic approach, Gonzalez-Guarda and colleagues [38] showed how interconnections between substance abuse, violence, HIV, and depression that result in negative outcomes for Latina teens can be buffered through culturally sanctioned importance of family ties that decrease the incidence of risky sexual behavior. In separate studies of Latina teens and pregnancy, Martinez and colleagues [39,40] revealed that pregnancy results in long-term reduction in risky sexual behaviors and therefore, counter-intuitively, pregnancy itself (generally considered to be a negative among teens) because of cultural values related to motherhood, becomes a wellness-promoting factor that reduces the syndemic risk of HIV, substance abuse, and depression. Vermeesch and colleagues [41] found that for Latinas, self-esteem is a protective factor that mediates between stress and depression. Women with higher self-esteem were less likely to be depressed, even in a context of high stress.

Study background.

The Hopkins Center (HC) is a behavioral health program in the International District (ID) of Albuquerque that serves a primarily low-income Latino population including many immigrant families. In 2008, in response to concerns about a high number of female clients presenting with the combined problems of social isolation and depression, counselors from the HCi created a Social Isolation Support Group (SISG) to help women establish social relationships, build social networks, and have an opportunity for peer discussion. The group meets weekly to nurture social relationships, provide social support for depression management, and develop individual health literacy using a peer-learning approach. SISG sessions are facilitated by the counselors, but the discussion is driven by the SISG members and topics of conversation emerge organically. Because the HC is located in a church in a residential neighborhood, the ambience of the setting is informal rather than institutional. To enhance the sense of a “protected space,” SISG members sign a contract agreeing not to talk about what is discussed during SISG sessions with others outside the group. SISG sessions are conducted in Spanish and childcare is provided. Despite the fact that they come from low-income households, members of the group have elected to bring a potluck-style meal, concretely demonstrating the cultural importance they place on food and the shared experience of eating.

The SISG started with only a few participants, but by 2012 when the project discussed here was being conceptualized, the SISG had grown to more than 20 attendees, including women from a wide range of ages and domestic situations. Membership is composed of women who are clients of the HC and some have come to the group through broader word-of-mouth. At the time we were developing this study, counselors from the HC felt that the group dynamic was having a positive impact on the lives of SISG members and they were interested to learn more about whether the group was an effective approach for reducing social isolation and depression, but they had not had the capacity to systematically evaluate the SISG more broadly as a peer support model.

In addition, counselors were fascinated by the fact that food routinely emerges as a topic of conversation during the group sessions, and that when members discuss food-related issues, the discussion is always particularly animated. SISG members speak with emotion about foods they prepare and the meaning that food has in their lives—and how food causes them both joy and pain in the context of immigration, the extent to which they struggle to afford food to feed their families, concerns they have about high levels of diabetes among extended family members or in the Latino community, and how they think diabetes may impact their own health or the health of their children. However, although members of the SISG had identified food and food-related health as an area of particular interest and concern in their own lives, they did not know how to explore this dimension of women’s experience or how to incorporate it into their group activities.

Overview.

Here we discuss findings from a mixed-method, community-engaged pilot study that investigated the ways that the four domains (social isolation, depression, diabetes, food insecurity) are connected in the lives of Latina immigrant women and that a countersyndemic peer support group intervention. We build upon the work of Mendenhall [34] and Gonzalez-Guarda and colleagues [32,38] the use syndemic models for improving our understanding of Latina health disparities. Here we go beyond the complex and often indirect and subtle connections between women’s emotional health and food that go beyond psycho-social constructions commonly found in health research [23,42,43]. We gathered empirical data on women’s experience with these domains, we evaluated the impact of the SISG on the social and emotional lives of participants, and we investigated the feasibility of enhancing the existing support group dynamic to engage women in a way that improves their capacity to deal with socioeconomic conditions and food environments that promote diabetes and food insecurity. Our results expand our understanding of the complex intersection of the four domains in the lives of Latina immigrant women, and illuminate strategies with the potential to nurture social connectivity, promote positive emotional health, and give women empowering knowledge and strategies to improve the quantity, quality and healthiness of their family’s food environment.

Methods

Team.

This pilot study was conducted between 2014 and 2015 through a collaborative partnership between the members of the SISG, the HC, and investigators from [BLINDED]. At the time of the study, all but one of the members of the SISG were first generation Mexican immigrants, and the group was a mix of HC counseling clients and other women who had joined through word-of-mouth. The HC team members were [AUTHOR #4] and [AUTHOR #5], the two counselors who founded the SISG, and a social work masters student intern who assisted with data collection. All three have worked extensively with the Mexican immigrant community in Albuquerque. [AUTHOR #4] was Director of the Center (at the time called St. Joseph Center for Children and Families) and [AUTHOR #5] has since become the Director (now called the Hopkins Center [HC]). Both [AUTHOR #5] and the social work intern are themselves Mexican immigrants. [AUTHOR #3], the Family Medicine physician from [BLINDED], who conducted the health assessments, has worked for many years at clinics serving the Mexican immigrant community and is the child of a Mexican immigrant family. She knew a number of the SISG members who had been patients she had seen previously at the clinic in the neighborhood where she worked. [AUTHOR #8] is a Health Extension Regional Officer (HERO) at [BLINDED] and works as the Latino health liaison for the [BLINDED]. He has particular expertise in issues of culturally appropriate health services and a long history of community organizing and engagement work in New Mexico, and he is a Mexican immigrant. Our biostatistician, [AUTHOR #2] works for [BLINDED] and was a master in public health (MPH) student at [BLINDED] the time of the study. Two research specialists [AUTHOR #6 AND AUTHOR #7] from [BLINDED] assisted with survey instrument selection and data analysis. [AUTHOR #1], is a cultural anthropologist based in [BLINDED]. She has worked extensively with Latino and Native American communities, including immigrants, and has expertise in gender theory and work with women’s groups. She conducted extended fieldwork with women and women’s groups in Bolivia, and research with Latina women and women’s groups in Albuquerque. All members of the team except [AUTHOR $8] were female, and all of the team members who interacted with participants were bilingual (Spanish/English or English/Spanish).

Approach.

We used an ethnographically inspired, holistic framework [44] to data collection and analysis, and in keeping with a community-engaged ethic, counselors from the HC and women from the SISG participated in designing project activities and methods, and in analyzing data. Participants received a $25 e merchandise card for each research component. All study participants provided signed informed consent using bilingual consent forms and project materials.

Setting.

The ID where this study was conducted is the most densely populated and ethnically diverse sector of Albuquerque [45]. The ID’s 15,000 residents are 63% Hispanic, 24% non-Hispanic white, 8% American Indian, 3% African American, and 2% Asian, and 31.2% of Hispanic residents of the ID are immigrants [45]. The census tracts composing the ID demonstrate a low level of educational attainment, low median household income, low mean earnings, a high percentage of households receiving food stamps, and a high poverty rate [45].

Community organizations, health providers, and members of the Latino immigrant community in the ID have identified social and emotional health problems (i.e., social isolation and depression), and food-related health concerns (i.e., diabetes and food insecurity) as seemingly separate but co-existing challenges to women’s health and wellbeing. These are of particular concern when viewed through a health disparities lens, as risk within these domains increases for low-income populations. With that in mind, it is salient that New Mexico (NM) is the second poorest state and is 3rd for the percentage of women living in poverty (20% of women versus 10% of men), including disproportionate burden among Hispanic women (25%) [45]. Nationally, 25% of Hispanic women are poor, but compared to all women, Hispanic women experienced greater increases in poverty since 2009 [29]. As the state with the highest percentage of Hispanics [45], this reality influences the risk of social-, emotional-, diabetes-, and food insecurity-related health disparites.

Diabetes has been identified in the NM Department of Health’s 2017–2019 Strategic Plan as a “super priority” [46, p.15] with significant disparities in the Latino community. Dramatically, the diabetes mortality rate per 100,000 for Latina women in NM is 29.4 compared with 12.8 among non-Hispanic white women [47]. In Bernalillo County where Albuquerque is located, diabetes is the 5th leading cause of mortality [48] and there are several negative diabetes-related health outcomes and risk factors associated with residence in the ID. The area of the ID where this research was conducted has high rates of diabetes-related deaths [47,49], diabetic hospitalizations [49,50], and diabetic ambulatory hospitalizations [49,51].

Similarly, food insecurity is an enormous problem in NM, the state with the highest rate of child poverty and 49th for overall poverty [52], the 3rd highest rates of child food insecurity [52] and senior hunger [53], and 4th worst for overall food insecurity [52]. One-in-4 children, 1-in-6 adults, and 1-in-8 seniors in NM do not know where they will get their next meal. The use of federal food assistance has risen to unprecedented levels with more than 400,000 people, or 20% of the state’s population, using Food Stamps/SNAP—up 66% since 2006 [54]. Beginning about 2007, pediatric health providers in the ID reported a rise in undernourished children (personal communication, Javier Aceves, MD). Various assessments of the food environment by local nonprofits have demonstrated real and perceived challenges to food access in the ID, especially in relation to availability and cost of healthy food, and excessive availability and low cost of fast food. Members of the community have been galvanized by their concern over food insecurity to look for local solutions through expanding Food Stamp application assistance and outreach, urban gardening projects, and a variety of emergency food access improvements, including a food pantry cooperative and a subsidized mobile farmers market. Despite these efforts, however, many immigrant households continue to struggle to put food on the table.

Data collection.

We gathered data through a variety of method, using English or Spanish, depending the preference of the participant.

Health assessment.

Health screening with health history.

[AUTHOR #3] who is a family physician and as indicated above, a second generation Mexican immigrant, conducted a standard health history and physical exam with each participant to help us better understand the health dimension of participants’ lives in relation to the domains of interest. The exam focused on physical, emotional, and food-related health, including discussion of any patient concerns and current symptoms, medication list, and medical, social, and family histories, and included measurement of blood pressure, and body mass index (BMI).

Blood analysis for A1(c):

Blood was also drawn and analyzed for A1c.

Survey.

The social work intern at HC administered a pre-/post-survey including demographic questions and combining four validated instruments: 1.) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) [55], 2.) Type II Diabetes Risk Assessment Form [56], 3.) Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support [57], and 4.) U.S. Adult Food Security Module [58].

Interviews.

[AUTHOR #1] conducted in-depth (one-to two-hour) interviews with participants using open-ended questions in a semi-structured format with prompts and follow-ups to allow participants to develop answers in relation to issues and ideas that they consider to be most relevant and important. [AUTHOR #1] has a great deal of experience interviewing participants, especially women. Questions explored the participant’s personal history and experience with and perceptions of domains of interest and participation in the SISG. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Despite the fact that the participants had known [AUTHOR #1] for only a year, they were extremely forthcoming and shared amazing, often tragic, stories of their lives in great detail. In addition to a great deal of experience conducting interviews, [AUTHOR #1] employs a culturally situated and community-engaged ethic in conducting research. This allows her to develop relationships of trust with participants that make it possible and more likely for participants to share their thoughts and feelings.

Structured dialogue group sessions.

We used an innovative method we have previously developed called structured dialogue (SD) [43,59] for the SISG to learn about, explore, discuss, and analyze food system issues that they found to be of interest, and develop an understanding of the broader forces that influence the food choices and practices that structure and define what their families eat on an everyday basis. Sessions were held once a month during one of the weekly SISG meetings and were conducted in Spanish, audio-recorded, and transcribed. The SD was co-facilitated by [AUTHOR #1] together with HC counselors, [AUTHORS #4 & #5]. [AUTHOR #3] participated when it was feasible for her in relation to her clinic schedule. Discussion occured in an organic, open-ended manner. During SD sessions, we presented powerful life stories and analyses from other studies of food and women’s health, and themes that emerged from the interviews for the group to consider and discuss in relation to their lives and experience. Content experts, including [AUTHOR #8] on topics of interest identified by the group (e.g., nutrition, diabetes physiology, Food Stamp/SNAP access, etc.) were invited to attend the meetings and participate in the discussions. As part of the interactive process, the SISG developed a cookbook that included recipes, illustrations, and poetry contributed by the women.

Data analysis.

Our analytic approach was designed to be rigorous, disciplined, and empirical according to Hammersley’s [60] criteria for qualitative research based on plausibility, credibility, and relevance. Using iterative data collection and analysis, we braided analysis of different data sets, allowing development of an abstract understanding of the relationship between concepts and patterns. Analytic interface of data from different methods occurred during interpretation [61]. Interim synthesized interpretations of survey data and transcripts informed the direction of interviews and SD discussions based on emergent conceptual categories. Preliminary analyses were presented to the SISG for comment and input in an ongoing way throughout the project. Interim interpretations were refined based on this input, allowing for dynamic inclusion of participant insights. This approach provided an opportunity to identify and explore issues that may not have been obvious themes or would have been unlikely to be explored in questions developed in the absence of conversation with participants.

Quantitative analysis.

Data from demographic questions, health histories, and A1c screening results were used to characterize the participants. Quantitative analysis included review of responses to pre-post surveys and health assessment data. Since the sample size was small (n=18) and we were not able to assume normality, we used the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test to test pre-post changes in Likert score responses. Median and standard deviation of the median were calculated for both time periods. We used the McNemar test for paired dichotomous data such as whether they were able to discuss problems with family members. Using the Spearman’s coefficient we also tested for associations between variables, focusing on variables that we hypothesized would be significant and using these as “pivot points” for the data (i.e., those that seemed consistently in line with other questions and that seemed to get to the heart of the relationship between the domains of interest).

Qualitative analysis.

Our qualitative analytic approach followed Gläser and Laudel’s [62] framework for theory-driven qualitative content analysis to identify conceptual categories and patterns related to the main domains of inquiry.

Qualitative survey responses:

Qualitative responses to survey questions were analyzed for themes using content analysis guided by a consensual approach [63] and coded inductively using NVivo software.

Transcripts:

Qualitative interview and meeting transcripts were analyzed inductively. Systematic themes and sub-themes within the domains were identified and coded manually. Transcripts explored women’s perspectives on social relationships and networks, the cultural and emotional meanings that women attach to food, the food access and the food procurement strategies that women pursue, the quality of food available and factors involved in individual food choice, the food preparation techniques women employ, women’s struggles with food insecurity, how a family’s food environment is influenced by women’s social isolation, factors that contribute to depression, and the dynamics, women’s heath, and impact of the SISG on their lives. Segments relevant to the themes or sub-themes were extracted, reduced, refined, and summarized. Interconnections between theme categories were explored through “constant comparison” [64] for holistic interpretation and to contribute to an abstract understanding of the relationship between concepts and patterns. To further explore patterns within each theme or sub-theme, data were examined and organized for coherence, and further interpretations were developed.

Results

We enrolled 21 SISG participants. We conducted 21 pre-/post-surveys, 17 health screenings with health history, 16 A1c blood tests, 20 interviews, and 11 SD group meetings that included 15–20 women at each meeting.

Health assessment:

Routine health assessments were conducted to better understand health status with regard to diabetes, hypertension and mental health conditions. Participants met with the family physician on the study team who is fluent in Spanish. Ages ranged from 21 – 63 years. Four had a personal history of diabetes, three of hypertension, and seven of a mental health condition. Perhaps most remarkable was that all but one had a family history of these conditions. On physical assessment, only one had a slightly elevated blood pressure. Twelve were overweight or obese. A few had minor health concerns. Three had health issues that needed to be addressed by their primary care providers. Study participants were given information on how best to proceed. None had acute issues that required immediate care. Of interest, most reported to have at least some regular access to care, although several reported difficulty with co-pays. Several did not have health insurance but knew of low-cost or free places to access care.

Survey:

We analyzed 18 surveys that had both pre and post responses.

Social isolation.

In the pre-, respondents who answered “yes” to the question, “I have a special person who is a real source of trust to me,” provided details about their relationships with husbands, parents, and friends. Respondents rely heavily on members of their immediate family for support and guidance. However, over 25% said that they are not able to discuss problems with family and 25% indicated that they do not get emotional help and support from family. The highest percentage of ‘no’ responses belonged to questions relating to support from friends. Nearly 25% indicated that they are not able to count on friends when things go wrong, and a similar number said that they do not have a special person with whom they can share their joys and sorrows. Ten percent reported they do not have a special person who they consider to be a source of comfort, and 15% do not have a special person available when they are in need. In the post-survey, the percentage of negative responses to questions about support from friends decreased, and the number of respondents reporting that they have a special person of trust in their lives increased (McNemar exact p=0.25).

Depression.

The number of women who reported that in the past four weeks, their physical or emotional health had not interfered or interfered very little with their social activities increased from 38% (n=7) to 77% (n=14). The median post-survey Likert score for this question was higher (mdn=6, std=1.43) than the pre-survey (mdn=4, std=1.45, p=0.056). The number of women reporting they felt “downhearted and blue” all or most of the time decreased from 3 (16%) to 1 (5%), and the number of women reporting they felt downhearted or blue a little or none of the time increased from 8 (44%) to 11 (61%). The median post-survey Likert score (mdn=4, std=1.13) for women reporting they “felt downhearted and blue” increased (mdn=5, std=0.92) with a p-value=0.24.

Food insecurity.

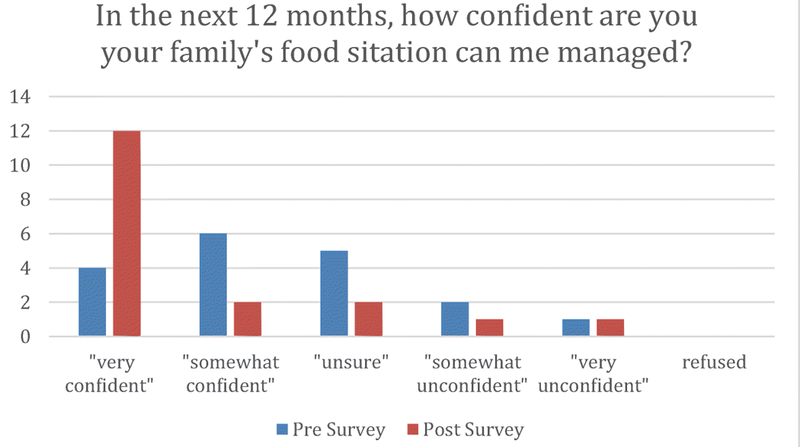

In response to the question “In the next 12 months, how confident are you that the household’s food situation can be managed?” 55% (n=10) of women reported they were “very confident” or “somewhat confident,” 27% (n=5) said they were unsure the food situation can be managed, and 16% (n=3) said they were either “somewhat unconfident” or “very unconfident.” In the post-survey, median responses to this question increased significantly (mdn=1, std=1.22) compared to the pre-survey (mdn=2, std=1.15, p=.017). Notably, for this question, the number of women reporting they were “very confident” that their household food situation could be managed went from four in the pre-survey to 12 in the post-survey. Eleven percent (n=2) of women indicated they were somewhat confident, 11% (n=2) were unsure, and only two women reported they were “somewhat unconfident” or “very unconfident” that the food situation can be managed, respectively.

There was also a decrease in the number of women who reported that in the last 12 months, there have been times when they were hungry but did not eat because they could not afford enough food (McNemar exact p=0.5) (See Figure #1 below). Although some of these p-values are above the .05 significance level, we felt the findings are relevant, as again our results may be an artifact of small sample size and they are consistent with the qualitative results of the study.

Figure 1:

Food security responses

Correlations.

Because we were interested in the associations between domains, we ran a Spearman correlation for associations on selected variables. The variables were selected based on a priori hypotheses about which associations would be significant. The scores were run on responses to the pre-survey. We found a significant association between confidence about ability to manage the household food situation and not feeling depressed or “blue” (p=<.05, Spearman’s rho=.59). These results support the trend seen in the p-values closer to significance, with women reporting a decrease in food insecurity and an improvement in mood.

Interview and group transcripts.

We reviewed 521 pages of transcript data from 20 interviews and 11 SD group sessions. Women who participated in this study shared stories of their own experiences of social isolation, depression, food insecurity, fear of diabetes (because it runs in their family), and the dangers and challenges associated with immigrant status. They described loneliness, domestic violence, rape, suicidal thoughts or attempted suicide, anger management problems, parenting challenges, interpersonal relationship dramas, physical, emotional, and financial abuse, chronic disease, legal and immigration-related threats to the health of their families, lack of self-confidence or low self-esteem, and poverty. Some women had more challenging personal histories or life situations than others, but all of the participants had experiences that they felt to be significant to their lives.

In individual interviews, 100% of interviewees reported that the SISG had been helpful or even transformational in their lives related to forming social relationships and friendships, sharing, reducing stress, relieving anxiety, making them feel as if they are not alone, and helping them understand their own problems and the problems of others with a new lens. These views were corroborated during group discussions. Talking about the what the group means to them and why it is important, participants discussed the significance of the SISG group dynamic of sharing, listening, getting help for one’s own problems, and being helpful to others:

I don’t have anyone here. No sister, or sisters-in-law, not anyone. But since I have been coming here, the others listen to me and I feel good. It is important to get everything that is inside us to come out. That’s how we feel good. It is important that people hear us. We need people to listen to us.… So I have listened to the others and then I compare my own situation with theirs and I see that mine is not as bad as some of the others. So if they can move on and move ahead, then I can do it also. This is what listening is about. I feel supported by the group by the way they listen to me.

Híjole! It is different [from seeing a counselor or psychologist]! The psychologist only diagnoses you and although you may unload your feelings or your experiences, you aren’t going to have the same discursive experience because everything stays the same. But the group is a place where you can converse about your problems with others and you can see how they made decisions when they were in your situation. You can see how their decisions worked and if they could work for you. They have experiences of this thing and that thing. And the psychologist can only advise you, but with the group you get the knowledge of their experiences and their advice and you can put it into practice for this or for that.

I have adored getting to know these women. … I am so glad to be with this group. It has been very healthy for me to get to know them. I think I will stay in the group until my blood stops running! I plan to stay because it is such a good experience. For me, this group is very important. There is no other place for people to listen to the problems I have. You know, sometimes you feel ashamed or shy, you don’t want people to know what is really happening in your life. But then you hear the braver ones talk about what they did and the others give advice on how to resolve the problem and it helps you. This is important because if the same thing happens to a few of us, you hear different situations but you say this is what is happening to me and this is what I have to do. For example, I was seeing a counselor for a problem I had but it wasn’t working so I stopped going. But here with the group, I found two different ideas about how to deal with it and it made my mind whirl with thought about how to move forward--how I need to grab onto my strengths. I had been trying to deal with this problem since I was small and wow, I found the solution. It was because the women here helped me figure it out. This group, for me, has so much value.

They also discussed the ways that the SISG is a positive influence on their health:

For me this program has been life-giving… I was suffering from a terrible depression … Thanks to the compañeras here, all of them, I’m moving forward

When you come here, you start to see changes in yourself—in your character and in your personality. I think it is because you are getting out of the house. You come here, you de-stress a bit. Then when you go back home and you continue with your kids, you are a bit more relaxed. You see things in a different manner. This is an outlet for a release of tension. I think this is really a good thing.

I suffer from nerves and stress—so this is really good for me. When I come to the group, I feel better, like I’m getting better. I have motivation (animo). This group is very helpful to me.... I have suffered a lot from depression, but the group helps … I have learned to live with this depression. … It isn’t like it was before. Now when I feel really bad, I talk with someone. I can’t talk to the counselors, the psychologists—it is friends (amigas) that I can trust. I know I can talk to them. My life isn’t like it was before. I felt so bad before but I stayed here in this group and now, it isn’t so bad.

They experience their participation in the SISG as a sort of personal renewal:

It is like a breath of fresh air.

There are people who God sends to our life and for me it is this group. Sometimes coming to the group is like wiping the slate clean and starting new. You are able to let go of what has been going on and when you leave you are like new. You have a new outlook on things. … It gives you energy and desire to do things….Or maybe you have been feeling depressed and you haven’t been wanting to eat and you come here and then you feel like trying the food. Coming here you just get motivated in a lot of ways.

Participants described how because of the special nature of the SISG in their lives, they wait with anticipation for the meetings:

I can’t stand it when the group doesn’t meet. It hurts me when there isn’t a group meeting!

We love this group. I, for one, have seen a difference in myself and now I feel that I NEED this group. In the [summer] months that we don’t have the group, I walk around feeling desperate… I love this group. Love it, love it, love it!

I don’t like to miss the group. I cancel other things so I can come. It has to be something really important to make me miss. When we started the group hardly anyone came. But then we began to interact and discuss things and then people started coming and coming. And now, thanks to God, there are a lot of us!

We keep track of what day it is by this group meeting. It is something special… Even my husband knows what day I go. He feels the respite it gives me.

Others discussed how important it is for them to have a time for themselves and how much they have grown as individuals by learning about the problems that others have faced and participating from a gendered perspective as women:

I come because it is a time that we have for ourselves as women. Having this space has helped us a lot. I have learned from each of the others things that have been important for my personal life. I always feel really happy when I come. When there isn’t a group meeting some weeks, I get bummed. It is really important to me.

Yes, it is like the everyday routine is difficult and then this time is just for ourselves. You learn about everyone’s problems and you learn the key to solving your own problems. Even if you don’t say anything, you find out how to think about things in a new way. And sometimes you don’t talk about something in the group, but there is someone you know here who you can trust who you can talk to and she helps you. Maybe she helps you learn to say no, I don’t like it, I don’t want it. You don’t have to do things just because someone asks. She is going to be your friend, regardless.

This group is really important for us. It is a time for us as women and it give us a space for the truth of that. No kids, it is just us relating to each other. We chat, we get along. It is a time just for us. It is really wonderful.

I feel as if in my life I have lacked a sense of myself as a woman and haven’t had a voice. But here I learned. It was through this group that I learned about myself and about how to be with my kids. It has been so helpful to me. And I feel really good about it.

I think the group has been important in keeping me healthy. The discussions we have help me feel good about my body, about myself… And here in the group, I learned that we don’t have to try to be perfect. Not everyone is happy with what they have been given, but you have to feel good about yourself. The group helps lift us up and feel good about ourselves—to give us self-esteem and to try so that everyone in the group feels good.

It is really beautiful here because you feel as if you blossom… You feel like you learn how to respond in any situation and what’s more, like you could help others in your family… You have no idea how much you enrich yourself from being part of the group.

In the transcripts, there was a great deal of talk about women’s strategies for stretching budgets and food products through differential shopping, price matching, clipping coupons, and utilization of food support programs such as food pantries and Food Stamps (the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program [SNAP]), what AUTHOR #1 [65, p. 19] describes as women’s “food access expertise.” In individual interviews almost all of the women reported experience with food insecurity, struggles to be able to afford food to feed their families, or challenges they face with weight management, healthy eating, and fear of the risk of diabetes. A number of interviewees cried while discussing these issues. Participants said things like:

[You feel] frustration, impotence, sadness because you feel like you can’t provide enough and that what you make won’t be sufficient.

I go to bed around 10:30. Sometimes I lie there, but I can’t sleep. I’m thinking what will I give them for lunch? What will I make for them to eat? What will I do? I go to Wal-Mart and I walk around and around. I look for the least expensive ítems, but those that will last and that I can prepare in different ways. I look for a way, because that is all I have.

I have such a problem. It totally stresses me out. I feel very bad that there isn’t food. My children suffer and it hurts me. When my kids come home from school and I don’t have anything to give them. It makes me feel terrible for them, not for me… It makes me so sad that my oldest, the poor thing, has to go to work without taking his lunch. I mean, he’s working so he should eat well. It just makes you feel terrible. It affects you. They say things like they want some fruit or a yogurt. My youngest really likes vegetables. But I don’t have any of those things.

If you go to the food bank and they give you a coffee cake… You feel sad because you have been wanting a coffee cake for a while and they were able to just give you one. So you end up wanting to eat the whole thing... and you eat too much and then you feel worse. It is bad for you and damages your health.

I really like to cook, but if I don’t have the things I want, it puts me in a bad mood. I get angry. I would like to go to the store and just get everything I need.

I had to go to the food pantry. But what do they give you? Macarroni and cheese, canned food, bread…. and this is what I’m supposed to feed my kids? That’s not sufficient for kids… no meat, no chicken… no vegetables. They don’t give you any of that, so where are the nutrients? What am I supposed to give my kids? It is ironic, we are more likely to get diabetes in my house even though we don’t have any food…

However, an interesting dynamic developed. Although a significant majority of participants discussed experiences with food insecurity and hunger in individual interviews, during group discussions of the issue of food insecurity, one participant expressed the opinion that there is no such thing as food insecurity in the U.S. and individuals who say they do not have enough food are just “lazy.” In this context, the initial response of participants was to make public statements that hid experiences and feelings that they revealed in private interviews. However, even without disclosing their own personal experience, in subsequent group meetings and interviews many of the women vehemently and angrily challenged perspectives and opinions that had been expressed by that participant.

Discussion

Outcomes of this pilot study demonstrate how countersyndemic dynamics can be leveraged and mobilized in the context of a health intervention. Our data provide a compelling argument that participation in the SISG with the SD group engagement process decreased women’s social isolation and depression, and enhanced women’s sense of their own capacity to positively influence the household food environment. The most notable quantitative data points were improvements in social relationship variables and overall confidence in managing the household food situation, and these were correlated. Group discussion with the SISG indicated that for participants, “managing the household food situation” implies both the capacity to ensure that the family has sufficient food and that the food be healthy and culturally appropriate. This means that improvements in this variable would potentially impact both food insecurity-related and diabetes-related health risk factors. Further, the association between confidence about ability to “manage the household food situation” and not feeling depressed or “blue” (p=<.05, Spearman’s rho=.5884) was significant and supports our hypothesis concerning the synergistic relationship between these domains.

Although some of the p-values we report are above the p=0.05 significance level, given the small sample size of this study, we believe they are still important to consider. Particularly notable is the percentage of respondents who said the support they received from friends increased during the study. This trend is also supported by our qualitative findings. A primary objective of the research was to determine whether participation in the SISG reduced social isolation by providing peer support and creating social ties. The evidence suggests that the SISG was successful in helping to create friendships and social network connections. Yet, more significant is the fact that in our extensive qualitative exploration of women’s experience, SISG members universally (100%) reported that the group had been extremely important to them in multidimensional ways. The narrative about this was really rather amazing. It is not often in the evaluation of a community group dynamic or project that you find universal agreement about how fabulous and important something is for participants.

And, what was clear from the stories participants told was the interconnected nature of the domains of interest in this study—social isolation, depression, diabetes, food insecurity, and immigration—and, importantly, the extent to which any one domain can not be properly understood when separated out from the others as we explored the lives of the women who participated in this study. Moreover, the factual discrepancy between experiences and feelings related to hunger and food insecurity described by the vast majority of group members and the heated, politicized narrative of one SISG member suggest the deep-seated emotional connection that women have with food and feeding others. It was striking that even in a group where individuals regularly discuss private struggles that have included rape, domestic violence, parenting challenges, weight gain, depression, and difficult interpersonal relationships, food insecurity was experienced as so deeply shameful and intimately personal that most women chose to hide or at least not to disclose to the group the battles they face in trying to feed their families nutritious meals. Andrews [66] used “cultural consonance theory” in her research on diabetes and depression among female Mexican immigrants in Alabama. Cultural consonance is the idea that individuals have culturally coded beliefs and behaviors that create cultural expectations. Andrews found that women who were not able to live up to their own ideals of a culturally consonant “good life” because of the structural conditions of immigration, internalized feelings of inadequacy and shame in a way that negatively affected wellbeing. This concept of cultural consonance is useful for thinking about what happened with hidden stories of food insecurity in our study and helps to explain the syndemic pathway through which the intersection of culture with structural dynamics of inequality produce bio impacts, or what Carney [36,37] calls the “biopolitics of food insecurity.”

The SD design of our pilot project helped SISG members to think about structural dimensions of the dynamics related to food that they were experiencing or that they see affecting their own lives and the lives of those around them. The SD provided a mechanism for them to disrupt the structural relations of power that make women feel ashamed and that create food insecurity in their homes by feeling supported in questioning the framework put forth by the one participant that echoed a narrative that is routinely articulated in the media and reflected in the design of public policy. The co-creational community engagement process that we created through the SD group sessions enhanced the peer group experience by establishing a context for nurturing what we call women’s “critical nutritional health literacy” [23,43,65] that became countersyndemic. Our preliminary research [23,43] with Latina women in another neighborhood in Albuquerque has determined that women find participation in this process to be an empowering experience that gives them information and tools to understand the root causes of food-related disparity. The group-centered learning that occurs is generative in that women are also able to develop social connections within the group, and to identify both individual actions and group strategies to improve the nutrition of their families. That research was in a historic Hispanic community with deep social roots and a significant community infrastructure. This pilot study demonstrates the feasibility of using a similar model of engagement with women from an immigrant community characterized by social isolation and shallow social ties.

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of this study was its small size. However, as a pilot study, we were able to gather rich data to help us understand the interconnected nature of the domains of interest in the lives of participants. A further limitation is that the participants had been participating in the SISG for different lengths of time when we began the pilot study. As such, we were not able to gather baseline data prior to participation in any group activities. We believe that the results that we did identify, suggest that if we had the capacity to measure a more exacting pre/post change, we would have found an even greater impact.

Through this pilot study, we identified an approach for reducing health disparities related to social isolation produced in the process of immigration. Our novel SD intervention leveraged positive cultural dynamics and women’s funds of knowledge to nurture transformative social connectedness, knowledge, and resiliency factors in the lives of participants. Especially revealing were the qualitative data where participants discussed their experiences and opinions. In 2018, we applied for research funds to scale-up our approach to replicate the intervention with more participants and conduct a larger, more controlled investigation. We will test whether participants decrease depression, stress, and social isolation, and increase social connectedness, resilience, empowerment, and knowledge. In future studies, we will investigate the cascading impacts of the intervention on the health of children and families, on the community at large, on how participation in the support group affects participants’ adaptation to the new context, if participation increases social and economic success for participants and their families, and if policy change could improve outcomes.

Table 1:

Participant Characteristics

| Total Number of Participants (N=21) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Education Level | Family History of Diabetes |

| 18–25 (2) | Less than high school (12) | No (8) |

| 26–35 (7) | High school graduate (5) | Yes, but not immediate family (4) |

| 36–45 (6) | Some college or higher (4) | Yes, immediate family (9) |

| 46–55 (5) | ||

| 56–65 (1) | ||

| Monthly Household Income | Obtained Food from Food Pantry in Last 12 Months | |

| Less than $500 (1) | Yes (8) | |

| $500-$999 (4) | No (13) | |

| $1,000-$1,499 (7) | ||

| $1,500-$1,999 (5) | ||

| $2,000-$2,499 (2) | ||

| $2,500-$2,999 (2) | ||

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank women who are members of the social isolation support group who participated in this research in multidimensional ways. Their stories are inspiring and their insights were extremely valuable as we developed our interpretations. We would also like to thank Betty Skipper, PhD for her wise advice as we prepared the statistical analysis for this article, and Helene Silverblatt, MD for her support for this research as a senior research mentor.

Funding Statement

The project discussed here, Understanding and Reducing Health Disparities Among Latina Immigrant Women in Relation to Synergistic Dynamics Associated with Social Isolation, Depression, Diabetes and Food Insecurity, was funded by a Community Engagement Pilot Award #CTSC0010–5 from the University of New Mexico (UNM) Clinical & Translational Science Center (CTSC) from April 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015.

Footnotes

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Human Subjects Statement

This project was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Protections Office (HRPO) as project #14–006 on February 4, 2014. The HRPO is the Institutional Review Board (IRB) ethics committee for research with human subjects at UNM. All participants provided signed informed consent.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

We wish to draw the attention of the Editor to the following fact that may be considered as a potential conflict of interest regarding this manuscript. We note that Jackie Perez works for the Hopkins Center, and previously worked for the Center under its previous name, St. Joseph Center for Children and Families. Tamara Thiedeman previously worked for the St. Joseph Center for Children and Families. Perez is currently the Director of the Center and Thiedeman was it’s previous Director. Both are licensed mental health professionals and they provide/provided services to clients, including some of the women who participated in this study. Both were involved in establishing the Women’s Social Isolation Support Group discussed here and both participated in the research. However, we believe that this relationship did not interfere with their ability to carry out the research, as they were interested in an objective analysis of the dynamics of the group process as part of an assessment of the services they provide.

At the time of the creation of the SISG and at the time of the study, the HC was called The St. Joseph Center for Children and Families. In 2017, the name of the Center and it’s organizational affiliation changed.

Contributor Information

Janet Page-Reeves, Department of Family & Community Medicine Office for Community Health University of New Mexico 1 University of New Mexico MSC09 5065 Albuquerque, NM 87131.

Sarah Shrum, College of Population Health University of New Mexico 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131.

Felisha Rohan-Minjares, Department of Family & Community Medicine University of New Mexico 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131.

Tamara Thiedeman, c/o The Hopkins Center for Children and Families/St. Joseph Center for Children and Families 7401 Copper Ave NE Albuquerque, NM 87108.

Jackie Perez, The Hopkins Center for Children and Families/St. Joseph Center for Children and Families 7401 Copper Ave NE Albuquerque, NM 87108.

Ambrosia Murrietta, Department of Psychology University of New Mexico Carla Cordova, MPH, Clinical and Translational Science Center University of New Mexico 1 University of New Mexico Albuquerque, NM 87131.

Francisco Ronquillo, Health Extension Officer Office for Community Health University of New Mexico 1 University of New Mexico MSC09 5065 Albuquerque, NM 87131.

References

- 1.Pedersen PV, Andersen PT, Curtis T. Social relations and experiences of social isolation among socially marginalized people. J Soc Pers Rel. 2012;29,6:839–858. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller DK, Malmstrom TK, Joshi S, et al. Clinically relevant levels of depressive symptoms in community‐dwelling middle‐aged African Americans. J Am Ger Soc. 2004;52,5:741–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullen SW, Solomon PL. Family and community integration and maternal mental health. Admin Pol Ment Health & Ment Health Serv Res. 2013;40,2:133–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, et al. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: Systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart 2016;102(13):1009–1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burdette HL, Wadden TA, Whitaker RC. Neighborhood safety, collective efficacy, and obesity in women with young children. Obes. 2006;14,3:518–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross CE, Mirowsky J. Neighborhood disadvantage, disorder, and health. J Health Soc Behav. 2001;42,3:258–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schieman S (2005). Residential stability and the social impact of neighborhood disadvantage: A study of gender-and race-contingent effects. Social Forces, 83(3), 1031–1064. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kyriakakis S, Dawson BA, Edmond T. Mexican immigrant survivors of intimate partner violence: Conceptualization and descriptions of abuse. Violence and Victims 2012;27,4:548–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizo CF, Macy RJ. Help seeking and barriers of Hispanic partner violence survivors: A systematic review of the literature. Aggression Violent Behav. 2011;16,3:250–264. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Izzo C, Weiss L, Shanahan T, et al. Parental self-efficacy and social support as predictors of parenting practices and children’s socio-emotional adjustment in Mexican immigrant families. J Prev Interv Comm. 2000;20,1–2:197–213. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor HO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, et al. Social isolation, depression, and psychological distress among older adults. J Aging Health. 2018;30,2:229–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus AF, Illescas AH, Hohl BC, et al. Relationships between social isolation, neighborhood poverty, and cancer mortality in a population-based study of U.S. adults. PloS One. 2017;12,3:e0173370. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kana’Iaupuni SM, Donato KM, Thompson-Colon T, et al. Counting on kin: Social networks, social support, and child health status. Soc For. 2005;83,3:1137–1164. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belliveau M Gendered matters: Undocumented Mexican mothers in the current policy context. Affilia. 2012;26:32–46. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez-Birkhead AC, Kennedy HP, Callister LC, et al. Navigating a new health culture: Experiences of immigrant Hispanic women. J Immig Minor Health. 2011;13,6:1168–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreby J, Schmalzbauer L. The relational contexts of migration: Mexican women in new destination sites. Soc Forum. 2013;28:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mendenhall E, Jacobs EA. Interpersonal abuse and depression among Mexican immigrant women with type 2 diabetes. Cult Med Psych. 2012;36,1:136–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bawadi HA, Ammari F, Abu-Jamous D, et al. Food insecurity is related to glycemic control deterioration in patients with type 2 diabetes. Clin Nutr. 2012;31,2:250–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laraia BA. Food insecurity and chronic disease. Adv Nutr: Int Rev J. 2013;4,2:203–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seligman HK, Jacobs EA, López A, et al. Food insecurity and glycemic control among low-income patients with type 2 diabetes. Dia Care. 2012;35,2:233–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waitzkin H, Getrich C, Heying S, et al. Promotoras as mental health practitioners in primary care: A multi-method study of an intervention to address contextual sources of depression. J Com Health. 2011;36,2:316–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bruening M, MacLehose R, Loth K, et al. Feeding a family in a recession: Food insecurity among Minnesota parents. Am J Pub Health. 2012;102,3:520–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AUTHOR, Colleagues “It is always that sense of wanting…never really being satisfied”: Women’s quotidian struggles with food insecurity in a Hispanic Community in NM. J Hung Env Nutr. 2014;92:183–209. DOI: 10.1080/19320248.2014.898176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer M Introduction to Syndemics: A Critical Systems Approach to Public and Community Health. John Wiley & Sons; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singer M, Clair S. Syndemics and public health: Reconceptualizing disease in bio‐social context. Med Anthro. 2003;17,4:423–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B. Syndemics and human health: Implications for prevention and intervention. Ann Anthro Prac. 2012;36,2:205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 2017;389:10072,941-–950.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ostrach B, Singer M. At special risk: Biopolitical vulnerability and HIV/STI syndemics among women. Health Soc Rev. 2012;21,3:258–271. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lerman S, Ostrach B, Singer M. (eds). Foundations of Biosocial Health: Stigma and Illness Interactions. Lexington Books of Rowan and Littlefield; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singer M, Bulled N, Ostrach B, Mendenhall E. Syndemics and the biosocial conception of health. Lancet. 389(10072), 941–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma A Syndemics: Health in context. Lancet,2017;389:10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gonzalez-Guarda RM, McCabe BE, Mathurin E, DeBastiani SD, Montano NP. The influence of relationship power and partner communication on the syndemic factor among Hispanic women. Wom Health Iss. 2017;27,4:478–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Himmelgreen DA, Romero‐Daza N, Amador E, Pace C. Tourism, economic insecurity, and nutritional health in rural Costa Rica: Using syndemics theory to understand the impact of the globalizing economy at the local level. Ann Anthro Prac. 2012;36,2:346–364. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mendenhall E Syndemic Suffering: Social Distress, Depression, and Diabetes Among Mexican Immigrant Women. New York NY: Left Coast Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potochnick S, Arteaga I. A decade of analysis: Household food insecurity among low-income immigrant children. J Fam Issues. 2018;39,2:527–551. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carney MA. The biopolitics of’food insecurity’: Towards a critical political ecology of the body in studies of women’s transnational migration. J Pol Ecol. 2014;21,1:1–18. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carney MA. The unending hunger: Tracing women and food insecurity across borders. Univ of California Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzalez‐Guarda RM, McCabe BE, Vermeesch AL, Cianelli R, Florom‐Smith AL, Peragallo N. Cultural phenomena and the syndemic factor: substance abuse, violence, HIV, and depression among Hispanic women. Ann Anthro Prac. 2012,36;2:212–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez I, Kershaw TS, Keene D, Perez-Escamilla R, Lewis JB, Tobin JN, Ickovics JR. Acculturation and Syndemic Risk: Longitudinal Evaluation of Risk Factors Among Pregnant Latina Adolescents in New York City. Ann Behav Med. 2017,52;1:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martinez I, Kershaw TS, Keene D, Perez-Escamilla R, Lewis JB, Tobin JN, Ickovics JR. Acculturation and Syndemic Risk: Longitudinal Evaluation of Risk Factors Among Pregnant Latina Adolescents in New York City. Ann Behav Med. 2017;52,1:42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vermeesch AL, Gonzalez-Guarda RM, Hall R, McCabe BE, Cianelli R, Peragallo NP. Predictors of depressive symptoms among Hispanic women in south Florida. W J Nurs Res. 2013;35,10:1325–1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delormier T, Frohlich KL, Potvin L. Food and eating as social practice: Understanding eating patterns as social phenomena and implications for public health. J Soc Health Ill. 2009;31,2:215–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.AUTHOR, Colleagues. “I took the lemons and I made lemonade”: Women’s quotidian strategies and the re-contouring of food insecurity in a Hispanic community in NM In AUTHOR ed. Off the Edge of the Table: Women Redefining the Limits of the Food System and the Experience of Food Insecurity. Lanham, MD: Lexington Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madden R Being Ethnographic: A Guide to the Theory and Practice of Ethnography. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 45.U.S. Census Bureau. American Community Survey 2016. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data.html

- 46.NM Department of Health. Strategic Plan 2017–19. 2017. https://nmhealth.org/publication/view/plan/2229/

- 47.NM Department of Health. NM’s Indicator-Based Information System (IBIS). 2016. Available at: https://ibis.health.state.nm.us/indicator/view/DiabDeath.RacEth.Sex.html

- 48.Bernalillo County Health Council. Bernalillo County Health Assessment. 2012. Available at: http://www.bchealthcouncil.org/Resources/Documents/CINCH%20Health%20Assessment%2012-18-12.pdf

- 49.Mishra S, Page-Reeves J, Regino L, et al. Community summary report: Results from a CTSC-funded planning project to develop a diabetes prevention initiative with East Central Ministries. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Prevention Research Center, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 50.New Mexico Department of Health. Bureau of Vital Records and Health Statistics. 2012. Available at: http://www.vitalrecordsnm.org/.

- 51.New Mexico Health Policy Commission. 2008 Hospital Inpatient Discharge Data. 2009. Available at: http://nmhealth.org/documents/2010ComprehensiveStrategicHealthPlanUpdate.pdf.

- 52.Center for American Progress. Poverty Talk: New Mexico. 2018. Available at: https://talkpoverty.org/indicator/listing/hunger/2017

- 53.Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics. Older Americans 2016: Key Indicators of Well-Being. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodriguez JC. Squeezed tighter: public assistance benefits face reductions as state battles budget woes, leaving struggling families to do without necessities. The Albuquerque Journal. December 27, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sawyer Radloff L Depression: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D): A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. 1977. Available at: http://apm.sagepub.com/content/1/3/385.abstract

- 56.Tuomilehto J, Lindström J Diabetes: Type II Diabetes Risk Assessment Form. Finnish Diabetes Association; Available at: http://www.diabetes.fi/files/502/eRiskitestilomake.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dahlem NW, Zimet GD, Walker RR. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support: A confirmation study. J Clin Psych. 1991. 47(6), 756–761. Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Available at: http://www.yorku.ca/rokada/psyctest/socsupp.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Economic Research Service United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). U.S. Adult Food Security Survey Module: Three-Stage Design, with Screeners. United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) September 2012. Available at: http://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/survey-tools.aspx#household [Google Scholar]

- 59.Williams P “I would have never “: A critical examination of women’s agency for food security through participatory action research In: AUTHOR, ed. Women Redefining the Experience of Food Insecurity: Life Off the Edge of the Table. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2014, pp. 275–314. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hammersley M Questioning Qualitative Inquiry: Critical Essays. London: Sage Publications; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Creswell JW. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gläser J, Laudel G. Life with and without coding: Two methods for early-stage data analysis in qualitative research aiming at causal explanations. Qual Forum. 2013;14,2: 10.17169/fqs-14.2.1886 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hill CS, Knox B, Thompson E. et al. Consensual qualitative research: An update. J Couns Psych. 2005;52,2:196–205. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Parry K Constant comparison From Michael Lewis-Beck, Alan Bryman & Tim Futing Liao (eds.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 65.AUTHOR. Conceptualizing food insecurity and women’s agency: A synthetic introduction In AUTHOR (ed.), Off the Edge of the Table: Women Redefining the Limits of the Food System and the Experience of Food Insecurity. Lanham, MD: Lexington Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Andrews C Culture’s Role in Immigrant Health: How Cultural Consonance Shapes Diabetes and Depression among Mexican Women in Alabama. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Alabama; 2018. [Google Scholar]