Abstract

The current longitudinal study is the first comparative investigation across Low- and Middle- Income Countries (LMICs) to test the hypothesis that harsher and less affectionate maternal parenting (child age 14 years, on average) statistically mediates the prediction from prior household chaos and neighborhood danger (at 13 years) to subsequent adolescent maladjustment (externalizing, internalizing, and school performance problems at 15 years). The sample included 511 urban families in six LMICs: China, Colombia, Jordan, Kenya, the Philippines, and Thailand. Multigroup structural equation modeling showed consistent associations between chaos, danger, affectionate and harsh parenting, and adolescent adjustment problems. There was some support for the hypothesis, with nearly all countries showing a modest indirect effect of maternal hostility (but not affection) for adolescent externalizing, internalizing, and scholastic problems. Results provide further evidence that chaotic home and dangerous neighborhood environments increase risk for adolescent maladjustment in LMIC contexts, via harsher maternal parenting.

Keywords: low-income and middle-income countries, adolescence, internalizing, externalizing, academic achievement, parenting

The deleterious effects on development of growing up in chaotic homes and dangerous neighborhoods (e.g., noise, crowding, lack of routines, crime, deteriorating housing, physical and psychological threats) are well documented, with harsher and less warm parenting identified as a potential mediator of these effects on youth outcomes (Evans & Wachs, 2010; Jennings, Perez, & Reingle Gonzalez, 2018; Jocson & McLoyd, 2015). However, there are at least two major gaps in research: most of the research on chaos and neighborhood danger has focused on childhood, with relatively few studies examining adolescence; and most of the studies have been conducted in wealthy nations. Like many other domains of developmental science, there is a need to examine household chaos and neighborhood danger in a wider range of geopolitical and cultural contexts (e.g., Lansford et al., 2016), to examine whether the deleterious effects reported in the literature generalize beyond higher-income national contexts. To this end, we investigated longitudinal predictive effects of covarying chaos and danger on adolescent maladjustment via maternal parenting practices. The sample included families in six low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), defined by the World Bank (2019) as countries with an annual per capita gross national income of less than US$ 12,475 in 2015.

Chaos and Neighborhood Danger: Definitions and Theory

Household chaos and neighborhood danger are distal risk factors that may influence youth externalizing, internalizing and scholastic problems via higher levels of harsh parenting and lower levels of warm supportive parenting. Household chaos includes uncertainty, distractions, lack of routines, noise, crowding, and clutter in the home (Evans & Wachs, 2010). Neighborhood danger extends this concept to family members’ perceived threats from the immediate area around their household, including physical and social disarray and likelihood of crime (Ross & Mirowsky, 1999). Chaos and neighborhood danger are more prevalent in lower-socioeconomic status (SES) homes and neighborhoods. Although correlated, SES, chaos, and neighborhood danger have distinguishable features and sequalae (Evans & Kim, 2013; Jocson & McLoyd, 2015; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). There is mounting evidence that household chaos and neighborhood danger are powerful causes of deleterious effects of poverty on social-emotional and cognitive functioning. Although most of the research has investigated children, some evidence suggests similar effects in adolescence (e.g., Evans, Gonnella, Marcynyszyn, Gentile, & Salpekar, 2005; Kohen, Leventhal, Dahinten, & McIntosh, 2008; Petrill, Pike, Price, & Plomin, 2004; Raver, Blair, Garrett-Peters, & Family Life Project, 2015).

Chaos and neighborhood danger may influence child and adolescent maladjustment in part through their effects on parenting environments (Evans & Wachs, 2010)—that is, parenting may mediate the link between chaos and danger, and youth outcomes. This is consistent with bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner, 2005), which places parents as key socializing agents who transmit effects of broader home and neighborhood contexts to children’s developmental outcomes. More precise predictions are offered by social learning, family stress, and coercion theories (see Dishion & Snyder, 2016), which state that chronic stressors in family environments (such as chaos and neighborhood danger) increase levels of harsh reactive caregiving and reduce resources for well-regulated, warm and supportive caregiving. In turn, these parenting behaviors elicit and reinforce externalizing behaviors (e.g., aggression, conduct problems), internalizing behaviors (e.g., anxiety, depression, social withdrawal), and scholastic problems in youth (Achenbach, Rescorla, & Ivanova, 2012).

Chaos and Danger: Does Parenting Mediate Effects on Youth?

Harsh, reactive, inconsistent parenting longitudinally predicts growth in children’s and adolescents’ behavioral, emotional and scholastic problems—even when controlling for “child effects” on parenting behavior (Deater-Deckard, 2013; Hentges & Wang, 2018; Pinquart, 2017). However, only a small number of the studies in that large literature have investigated the potential mediating role of parenting, in the link between chaos or neighborhood danger and youth maladjustment. In summarizing relevant empirical evidence below, we first consider the literature on youth externalizing and internalizing problems, and then turn to academic problems.

Regarding behavioral and emotional problems, a handful of studies have tested whether parenting behavior mediates the potential effects of household chaos on youth maladjustment. Most recently, Mills-Koonce et al. (2016) reported that chaos in early childhood predicted less sensitive as well as harsher intrusive caregiving, which in turn predicted child conduct problems in first grade. Prior to that study, several others had directly tested, or presented results suggestive of, a mediating effect of parenting in the link between household chaos and child maladjustment via less supportive and harsher parenting (Coldwell, Pike, & Dunn, 2006; Deater-Deckard et al., 2009; Valiente, Lemery-Chalfant, & Reiser, 2007). Turning to neighborhood danger, a number of studies have shown mediation or an indirect effect of neighborhood risks on child and adolescent behavioral and emotional problems via harsher, less supportive parenting (Cantillon, 2006; Dodge, Greenberg, Malone, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2008; Gonzales et al., 2011; Mrug & Windle, 2009; Roosa et al., 2002; for the most recent study see Li, Johnson, Musci, & Riley, 2017; see also Colder, Mott, Levy, & Flay, 2000, for a null result).

With regard to academic problems, prior evidence indicates contemporary and longitudinal associations between higher chaos and poorer child performance of verbal and nonverbal skills that undergird scholastic problems (Berry et al., 2016; Blair, Ursache, Greenberg, & Vernon-Feagans, 2015; Deater-Deckard et al., 2009; Hanscombe, Haworth, Davis, Jaffee, & Plomin, 2011; Vernon-Feagans, Garrett-Peters, Willoughby, & Mills-Koonce, 2012). Household chaos may impede parental supervision and monitoring of child routines (including homework and studying) and parental participation in school meetings and activities. This is a concern, because parental monitoring of and involvement in children’s academic work is a consistent predictor of youth academic success (Fan & Chen, 2001). Chaos has been linked with parenting that places less value in and support of child academic growth, which in turn has been associated with poorer academic achievement skills (e.g., Johnson, Martin, Brooks-Gunn, & Petrill, 2008). However, it is not yet known whether harsh and warm parenting behaviors statistically mediate the link between chaos and child academic problems.

Compared to the literature on academic problems and chaos, there have been many more studies that investigated academic outcomes and neighborhood risks. Living in poorer, riskier neighborhoods is linked with poorer scholastic achievement (for reviews and meta-analyses see Ainsworth, 2002; Nieuwenhuis & Hooimeijer, 2016; Sirin, 2005). Evidence also points to lower levels of caregiver engagement and cognitive/linguistic stimulation in more dangerous neighborhoods (e.g., Aikens & Barbarin, 2008; Eamon, 2005; Kohl, Lengua, & McMahon, 2000). However—like the literature on chaos, parenting and child scholastic problems—there have not been investigations of the statistical mediating role of harsh or warm parenting behavior in the link between neighborhood danger and academic outcomes.

Chaos, Danger, and Adolescent Development in LMICs

In addition to the lack of testing of statistical mediation described above, there are two major limitations in the literature. First, although many of the prior studies have examined families across a wide range of SES and neighborhood contexts, nearly all research has been conducted in the United States and other wealthy industrialized nations. There are some noteworthy exceptions. Wachs and Corapci’s (2003) seminal review of international research on household and neighborhood chaos and risks, parenting, and children’s development, documented consistency in links with lower SES, harsher and less positive parenting, and youth maladjustment. Subsequent review papers and empirical studies have continued to point to a general consistency in effects across cultures and countries (Evans & Wachs, 2010; Ferguson, Cassells, MacAllister, & Evans, 2013; Skinner et al., 2014). Nevertheless, there remains an underrepresentation of studies of families in LMICs, and to our knowledge none has directly compared multiple LMICs to each other within a multiple-group study design.

A second limitation is that there is too little research in adolescence on the links between chaos, parenting and youth maladjustment—nearly all of the studies have examined early and middle childhood. A review (Devenish, Hooley, & Mellor, 2017) of mediators of the link between lower SES and adolescent maladjustment identified only one study that reported on household chaos (Evans et al., 2005); its effects were like those reported in childhood. More recently, there have been two adolescent studies published (both in the United States, with predominantly White samples). One studied middle-class families with 14-year-olds and found correlations in the .2 to .3 range between chaos, hostile parenting, and adolescent callous-unemotional behaviors (Kahn et al., 2016). The other included a low- to middle-SES Appalachian sample of 14-year-olds. This second study showed similar effect sizes to Kahn et al., for the associations between chaos, lower parental monitoring, adolescent risky decision making, and lower executive function and verbal ability (Brieant et al., 2017; Lauharatanahirun et al., 2018). Although there have been only a few studies of chaos and adolescent adjustment, the evidence suggests similar effects to those previously reported for early and middle childhood. In contrast to the sparse literature on household chaos in adolescence, there is a substantial literature on neighborhood risks and maladjustment for adolescents and children alike. Effect sizes are similar across these wide age ranges (for recent examples, see King & Mrug, 2018; Li et al., 2017; McDermott, Donlan, Anderson, & Zaff, 2017).

Study Aims and Hypothesis

In sum, our primary aim was to test the hypothesis that higher levels of household chaos and neighborhood danger (at 13 years of age) would statistically predict harsher and less warm parenting (at 14 years), which in turn would predict higher levels of adolescent externalizing, internalizing, and academic problems (at 15 years). An additional aim was to test the hypothesis while addressing gaps in the literature by examining longitudinal data in a sample of adolescents living in six LMICs. We tested the hypothesis in the total sample, and then estimated the consistency of effects across the six national sites—while controlling for household income, maternal education, and child gender and age.

Method

Participants

Ethics approval for the research was granted by IRBs at each university; parents provided written consent and youth provided assent. Participants included 511 families from an ongoing longitudinal study with data at annual study years 5, 6 and 7 (age range at study year 5: 11 to 15 years, M = 12.91, SD = 0.76; 53% girls) from urban areas in LMICs in the Parenting Across Cultures project. The countries were selected because they spanned several dimensions known to be important to family processes and youth development: average levels of and variability in individualist—collectivist orientations (Minkov et al., 2017); religiosity and predominant religions (Johnson & Grim, 2018); and family policies (e.g., systems for protecting minors; family planning and birth control; see for example the information data gathered by the United Nations, https://data.unicef.org).

Descriptive statistics by study site are reported in Table 1. The gender distributions, average age and sample sizes by location were: Shanghai, China (56% female, age=11.6, n = 61); Medellín, Colombia (49% female, age=13.4, n = 79); Zarqa, Jordan (50% female, age=12.7, n = 104); Kisumu, Kenya (60% female, age=13.0, n = 91); Manila, Philippines (47% female, age=12.6, n = 84); and Chiang Mai, Thailand (52% female, age=13.6, n = 92). The majority (86%) of parents were married couples, although a non-resident parent (if the couple was separated or divorced) also could participate. Participants were representative of the majority ethnic group in their country, except for in Kenya (the Luo, the third largest group at 13% of population). The typical family size included two to three adults, and two to three children or adolescents. On average, mothers completed 12 years of formal education. Family income was reported using 10 income ranges on an ordinal scale rated from 1 to 10; 52% of families reported income in the lowest two categories, and 14% reported income in the highest two income categories. Forty-five percent of families reported not having enough money to meet their needs, on an item pertaining to whether the family had experienced financial strain (0 = no, 1 = yes).

Table 1:

Descriptive Statistics by Site

| China | Kenya | Philippines | Thailand | Colombia | Jordan | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=85 | n=93 | n=91 | n=100 | n=85 | n=104 | |

| n=123 | n=100 | n=120 | n=120 | n=108 | n=114 | |

| n=80 | n=93 | n=91 | n=97 | n=84 | n=102 | |

| n=80 | n=93 | n=91 | n=89 | n=84 | n=102 | |

| n=83 | n=93 | n=91 | n=99 | n=84 | n=103 | |

| n=123 | n=100 | n=120 | n=119 | n=108 | n=114 | |

| n=77 | n=94 | n=92 | n=101 | n=88 | n=104 | |

| n=77 | n=94 | n=92 | n=101 | n=88 | n=104 | |

| n=77 | n=94 | n=92 | n=101 | n=88 | n=104 | |

| n=84 | n=93 | n=91 | n=100 | n=85 | n=104 | |

| n=81 | n=89 | n=88 | n=95 | n=85 | n=103 | |

| n=82 | n=79 | n=70 | n=76 | n=74 | n=101 | |

| n=85 | n=90 | n=91 | n=100 | n=85 | n=104 | |

| n=84 | n=89 | n=87 | n=94 | n=85 | n=103 | |

| n=81 | n=79 | n=70 | n=76 | n=74 | n=101 | |

| n=85 | n=90 | n=91 | n=100 | n=85 | n=104 | |

| n=52 | n=86 | n=73 | n=87 | n=81 | n=101 | |

| n=52 | n=86 | n=73 | n=87 | n=81 | n=101 | |

| n=52 | n=86 | n=73 | n=87 | n=81 | n=101 | |

| n=52 | n=86 | n=73 | n=87 | n=81 | n=101 | |

| n=55 | n=86 | n=73 | n=87 | n=81 | n=101 | |

| n=39 | n=78 | n=89 | n=82 | n=78 | n=103 | |

| n=38 | n=61 | n=64 | n=63 | n=70 | n=99 | |

| n=44 | n=78 | n=90 | n=85 | n=78 | n=104 | |

| n=39 | n=78 | n=89 | n=82 | n=78 | n=103 | |

| n=39 | n=61 | n=64 | n=63 | n=70 | n=99 | |

| n=44 | n=78 | n=90 | n=85 | n=78 | n=104 | |

| n=38 | n=77 | n=89 | n=81 | n=76 | n=103 | |

| n=36 | n=61 | n=63 | n=63 | n=67 | n=99 |

Recruitment letters were sent from private and public schools (to help ensure economic diversity) to families, when the participants were 7–10 years old; we enrolled those who responded with a returned contact form. The strategy was effective for obtaining a diverse international sample, with site-specific samples that captured the breadth of incomes in that area. Families were recruited as convenience samples from area schools spanning low- to high-income neighborhoods including public and private schools in proportion to the city’s overall population. The PIs at each site used locally available information to determine which schools to include. It is not known how representative the selected samples were of the actual population.

Attrition across these three annual assessments was 11% but varied by site, based on analysis of samples from Year 1 to the three years being examined in the current analyses (i.e., from 50% retention in China to 91% retention in Kenya and Jordan). We compared the retained and “dropout” families based on the variables in the current analysis that were available in Year 1. There were no significant differences in Kenya and Jordan. There was a significant difference on only one variable in China (maternal hostility/aggression), Thailand (paternal neglect-indifference), and Colombia (father’s education). In the Philippines, there was a difference on three variables (mother’s and father’s education, and maternal rejection). Overall, there were six significant differences of 156 tested (3.8%); given this very small proportion, we assumed data to be missing at random and used full information maximum likelihood estimation for analyses.

Procedure and Measures

Questionnaires (that had been translated and back-translated using standard procedures) were completed during interviews that were scheduled at home, school, or other locations that were convenient for families. Specific measures were administered in some but not all years; we have utilized as much available data as possible. Multi-informant composite z-scores (based on standardized scores for each informant) were computed for analyses. The bivariate correlations are provided in Table 2.

Table 2:

Bivariate Correlations (p-values): Multi-Informant Composite Z-Scores

| Chaos | Danger | Harsh | Affection | Extern. Behs | Intern. Behs | Sch. Perform. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Averaged across Reporters | (0.02) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (0.053) | (0.001) | |

| Averaged across Reporters | (0.009) | (0.697) | (<0.001) | (0.001) | (0.001) | ||

| Averaged across Reporters | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | (0.02) | |||

| Averaged across Reporters | (<0.001) | (0.325) | (0.005) | ||||

| Averaged across Reporters | (<0.001) | (<0.001) | |||||

| Averaged across Reporters | (<0.001) | ||||||

| Averaged across Parents |

In study year 5 (13 years), mothers, fathers, and youth completed an abbreviated version of the Chaos, Hubbub and Order scale (Matheny, Wachs, Ludwig, & Phillips, 1995) which captures perceptions of noise, lack of routines, clutter, and crowding in the household on a 5-point Likert-type scale. For each reporter, a scale was created by averaging 5 of the 6 items; the item regarding television use was excluded, because televisions and consistent electricity are less common in the LMICs. A chaos summary scale was created by averaging the standardized summary scales across all reporters. The reliability coefficients by site were typical for this abbreviated scale (Lauharatanahirun et al., 2018) apart from Jordan (China=0.64, Kenya=0.54, Philippines=0.62, Thailand=0.75, Colombia=0.73, and Jordan=0.35). Given the low reliability for Jordan, the statistical models presented here were also estimated without Jordan and the results were consistent.

Mothers, fathers, and youth also completed the Neighborhood Scale (Griffin et al., 1999; O’Neil et al., 2001). For each reporter, a scale was created by averaging four items (rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale) capturing whether: youth get in trouble, there are drugs and gangs, neighborhood is dangerous, and one feels scared. A neighborhood danger scale was constructed by averaging the standardized scales across reporters (α by site: China=0.73, Kenya=0.70, Philippines=0.87, Thailand=0.77, Colombia=0.86, and Jordan=0.87; Skinner et al., 2014).

In study year 6 (14 years), mothers completed the Parental Acceptance-Rejection/Control Questionnaire-Short Form (Rohner, 2005). They reported frequencies with which they used different behaviors with their child, using a 4-point scale (from 1 = never/almost never, to 4 = every day). Items were averaged into four sub-scales capturing maternal affection, hostility, neglect, and rejection. Mothers also reported on their use of psychological control (Barber, Olsen, & Shagle, 1994), based on eleven items rated on the same 4-point Likert-type scale that address parents’ use of negative emotion induction and manipulation to control adolescents’ behaviors. For the purposes of the current study, we examined maternal affection from the Rohner instrument (α by site: China=0.85, Kenya=0.69, Philippines=0.68, Thailand=0.83, Colombia=0.84, and Jordan=0.80), separately from a standardized composite score representing maternal harsh parenting from the standardized scales from the Rohner and Barber instruments (hostility, neglect, rejection, and psychological control z-scores; α by site: China=0.87, Kenya=0.70, Philippines=0.78, Thailand=0.82, Colombia=0.80, and Jordan=0.86).

In study year 7 (15 years), mothers, fathers and adolescents (self-report) rated how often the adolescent exhibited certain behaviors and emotions using the 3-point frequency scale (0 = never to 2 = often) on the Child Behavior Checklist Parent Report or Youth Self Report (Achenbach, 1991). The externalizing problem behavior scale sums across 33 items (parent report) or 30 items (youth report) regarding lying, truancy, vandalism, bullying, disobedience, tantrums, sudden mood change, physical violence, use of alcohol and drugs, and being unusually loud. A single cross-reporter externalizing problems scale was created by averaging across the standardized scales for the three reporters (α by site: China=0.94, Kenya=0.86, Philippines=0.92, Thailand=0.94, Colombia=0.93, and Jordan=0.96). The internalizing problem behavior scale sums 30 items (parents) or 29 items (youth) regarding self-consciousness, sadness, worry, nervousness, and somatic problems. A single cross-reporter internalizing problems scale was created by averaging across the standardized scales for the three reporters (α by site: China=0.93, Kenya=0.84, Philippines=0.89, Thailand=0.88, Colombia=0.93, and Jordan=0.91). Parents also completed five items regarding school performance (reading, writing, math, science, and social studies) using a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = failing to 4= above average). A single cross-reporter school performance scale was created by averaging across the standardized scales for both parents (α by site: China=0.89, Kenya=0.88, Philippines=0.82, Thailand=0.90, Colombia=0.86, and Jordan=0.96).

Data Analysis

We estimated a multi-group path model in Mplus, using full information maximum likelihood. Each maternal parenting construct (year 6, 14-years-old) was predicted by chaos, neighborhood danger, and covariates of family income, mother’s education, as well as child’s gender and age (year 5, approximately 13 years). The residual variance for affection and harsh parenting covaried. Adolescent outcomes (year 7, 15 years) were predicted by both parenting constructs (year 6) as well as chaos, danger, and covariates (year 5). Each outcome was studied in a separate model. All intercepts and residual variances could vary by site. Initially, the estimated paths were fixed to be equal across sites. Model fit was evaluated using standard criteria (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Using modification indices, site-specific paths were iteratively freed until optimal model fit was achieved.

Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the key variables. Overall across the three adolescent outcomes, only a small handful of paths in the models had to be freed in a few countries for obtaining model fit. These included: a residual correlation between harsh parenting and affection (China and Jordan); main effect from chaos to externalizing problems (Philippines and Colombia); main effect from affection to externalizing problems (Philippines); main effect from chaos to school performance (Jordan); and main effect from harsh parenting to school performance (Kenya). In each case, Wald tests (W) revealed that the freed path coefficient was statistically different (p < .05) for the identified country compared to all other countries. The overall pattern was that model paths could be fixed as equal across the six LMIC samples.

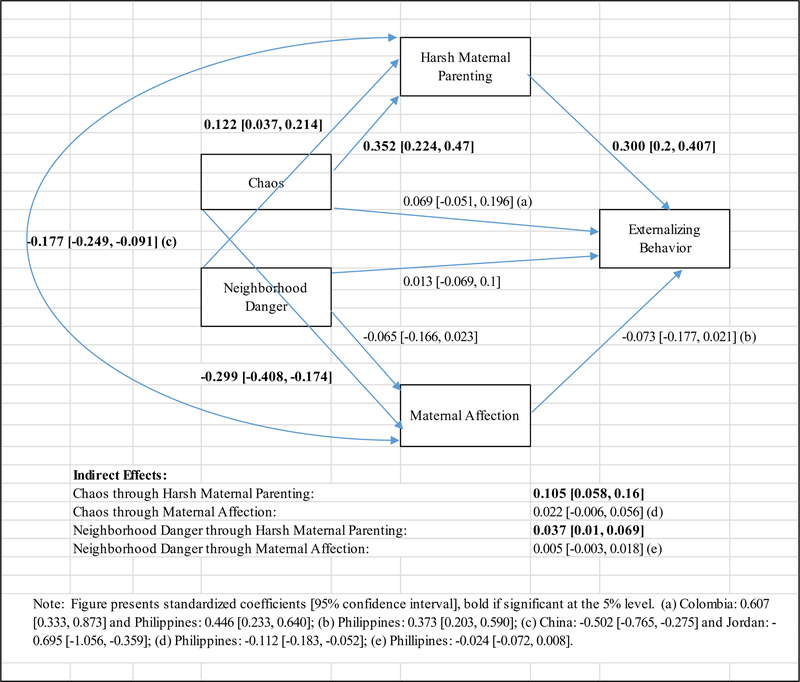

Externalizing Problems

Figure 1 summarizes results for externalizing problems. A full reporting of all parameter estimates for all sites is provided in Table 3. Optimal fit was not initially achieved when all 18 paths were fixed across the six sites (χ2 p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.101, CFI = 0.742, TLI = 0.691, SRMA =0.107). However, after releasing eight site-level paths (described in Table 3), optimal fit was achieved (χ2 p = 0.101, RMSEA = 0.047, CFI = 0.948, TLI = 0.933, SRMA = 0.082).

Figure 1:

Full-Information Maximum Likelihood Multi-Group Path Model Estimating Externalizing Problems

Table 3:

Full-Information Maximum Likelihood Multi-Group Model Results

| Externalizing Behavior | Internalizing Behavior | School Achievement | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Std Est | 95% CI | Std Est | 95% CI | Std Est | 95% CI | |

| Maternal Affection | ||||||

| Chaos | −0.299 | [−0.408, −0.174] | −0.315 | [−0.42, −0.188] | −0.303 | [−0.413, −0.183] |

| Neighborhood Danger | −0.065 | [−0.166, 0.023] | −0.047 | [−0.153, 0.042] | −0.063 | [−0.164, 0.025] |

| Mother’s Education | 0.141 | [0.046, 0.235] | 0.152 | [0.052, 0.246] | 0.140 | [0.048, 0.23] |

| Child is Male | 0.012 | [−0.133, 0.171] | −0.006 | [−0.158, 0.155] | 0.016 | [−0.133, 0.177] |

| Family Income | −0.089 | [−0.187, 0.004] | −0.085 | [−0.19, 0.014] | −0.091 | [−0.186, 0.001] |

| Child’s Age | −0.060(a) | [−0.168, 0.044] | −0.037 | [−0.143, 0.073] | −0.060(l) | [−0.167, 0.048] |

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | ||||||

| Chaos | 0.352 | [0.224, 0.47] | 0.347 | [0.216, 0.465] | 0.358 | [0.239, 0.486] |

| Neighborhood Danger | 0.122 | [0.037, 0.214] | 0.126 | [0.037, 0.221] | 0.122 | [0.037, 0.215] |

| Mother’s Education | 0.048 | [−0.047, 0.145] | 0.050 | [−0.05, 0.148] | 0.056 | [−0.039, 0.154] |

| Child is Male | −0.030(b) | [−0.193, 0.13] | 0.065 | [−0.096, 0.224] | −0.035(m) | [−0.193, 0.121] |

| Family Income | −0.140 | [−0.238, −0.038] | −0.148 | [−0.253, −0.04] | −0.146 | [−0.24, −0.04] |

| Child’s Age | 0.070 | [−0.043, 0.173] | 0.076 | [−0.04, 0.182] | 0.070 | [−0.039, 0.174] |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Chaos | 0.069(c) | [−0.051, 0.196] | 0.189 | [0.069, 0.315] | −0.221(n) | [−0.354, −0.09] |

| Neighborhood Danger | 0.013 | [−0.069, 0.1] | 0.003 | [−0.082, 0.094] | 0.041 | [−0.062, 0.142] |

| Mother’s Education | −0.014 | [−0.1, 0.072] | −0.059 | [−0.15, 0.039] | 0.170 | [0.071, 0.266] |

| Child is Male | 0.049(d) | [−0.107, 0.21] | −0.128(i) | [−0.296, 0.045] | −0.261(o) | [−0.428, −0.091] |

| Family Income | 0.038 | [−0.063, 0.134] | −0.085(j) | [−0.218, 0.044] | 0.215 | [0.095, 0.337] |

| Child’s Age | −0.058 | [−0.152, 0.046] | 0.066 | [−0.049, 0.18] | −0.058 | [−0.177, 0.062] |

| Maternal Affection | −0.073(e) | [−0.177, 0.021] | 0.036 | [−0.076, 0.143] | 0.049 | [−0.049, 0.151] |

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.300 | [0.2, 0.407] | 0.221 | [0.119, 0.342] | −0.195 | [−0.302, −0.105] |

| Residual Cov: Maternal Affection and Harsh Parenting | −0.177(f) | [−0.249, −0.091] | −0.217(k) | [−0.295, −0.124] | −0.176(p) | [−0.247, −0.09] |

| Indirect Effects: | ||||||

| Chaos Through Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.105 | [0.058, 0.16] | 0.077 | [0.035, 0.13] | −0.070 | [−0.12, −0.033] |

| Chaos Through Maternal Affection | 0.022(g) | [−0.006, 0.056] | −0.011 | [−0.047, 0.024] | −0.015 | [−0.046, 0.015] |

| Neighborhood Danger thought Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.037 | [0.01, 0.069] | 0.028 | [0.007, 0.058] | −0.024 | [−0.049, −0.006] |

| Neighborhood Danger thought Maternal Affection | 0.005(h) | [−0.003, 0.018] | −0.002 | [−0.013, 0.006] | −0.003 | [−0.015, 0.004] |

| Site Specific Intercepts and Residual Variances | ||||||

| China | ||||||

| Intercepts: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.741 | [0.383, 1.093] | 0.708 | [0.34, 1.063] | 0.760 | [0.388, 1.122] |

| Maternal Affection | −0.703 | [−1.023, −0.379] | −0.669 | [−0.983, −0.335] | −0.709 | [−1.046, −0.395] |

| Outcome | −0.851 | [−1.128, −0.567] | −0.308 | [−0.681, 0.069] | −0.581 | [−0.982, −0.205] |

| Residual Variance: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.855 | [0.47, 1.34] | 0.673 | [0.348, 1.101] | 0.856 | [0.463, 1.303] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.73 | [0.459, 1.005] | 0.563 | [0.362, 0.731] | 0.732 | [0.466, 0.989] |

| Outcome | 0.254 | [0.069, 0.447] | 0.536 | [0.236, 0.889] | 0.596 | [0.195, 1.016] |

| Kenya | ||||||

| Intercepts: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | −0.091 | [−0.306, 0.136] | −0.134 | [−0.351, 0.094] | −0.085 | [−0.297, 0.151] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.027 | [−0.193, 0.225] | 0.028 | [−0.193, 0.234] | 0.022 | [−0.194, 0.23] |

| Outcome | −0.405 | [−0.591, −0.206] | 0.036 | [−0.19, 0.258] | −0.171 | [−0.512, 0.15] |

| Residual Variance: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.830 | [0.531, 1.127] | 0.843 | [0.55, 1.136] | 0.834 | [0.546, 1.143] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.723 | [0.424, 1.096] | 0.734 | [0.435, 1.11] | 0.723 | [0.422, 1.099] |

| Outcome | 0.496 | [0.297, 0.687] | 0.552 | [0.381, 0.695] | 0.983 | [0.596, 1.351] |

| Philippines | ||||||

| Intercepts: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | −0.070 | [−0.281, 0.144] | −0.124 | [−0.342, 0.088] | −0.065 | [−0.278, 0.147] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.326 | [0.125, 0.507] | 0.333 | [0.132, 0.521] | 0.320 | [0.127, 0.508] |

| Outcome | 0.096 | [−0.1, 0.274] | 0.197 | [−0.026, 0.421] | −0.154 | [−0.35, 0.04] |

| Residual Variance: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.667 | [0.428, 0.924] | 0.710 | [0.452, 0.993] | 0.668 | [0.427, 0.921] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.541 | [0.283, 0.808] | 0.570 | [0.301, 0.844] | 0.542 | [0.284, 0.805] |

| Outcome | 0.426 | [0.276, 0.549] | 0.928 | [0.505, 1.445] | 0.566 | [0.381, 0.741] |

| Thailand | ||||||

| Intercepts: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | −0.339 | [−0.543, −0.123] | −0.388 | [−0.595, −0.168] | −0.333 | [−0.536, −0.116] |

| Maternal Affection | −0.163 | [−0.415, 0.069] | −0.175 | [−0.428, 0.059] | −0.166 | [−0.408, 0.053] |

| Outcome | −0.065 | [−0.267, 0.135] | −0.109 | [−0.303, 0.096] | −0.180 | [−0.386, 0.02] |

| Residual Variance: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.686 | [0.455, 0.897] | 0.704 | [0.472, 0.92] | 0.686 | [0.463, 0.896] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.961 | [0.555, 1.401] | 0.986 | [0.581, 1.427] | 0.961 | [0.562, 1.398] |

| Outcome | 0.553 | [0.363, 0.721] | 0.542 | [0.343, 0.723] | 0.471 | [0.32, 0.602] |

| Colombia | ||||||

| Intercepts: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | −0.032 | [−0.259, 0.193] | −0.088 | [−0.315, 0.14] | −0.021 | [−0.245, 0.205] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.306 | [0.071, 0.525] | 0.289 | [0.054, 0.512] | 0.300 | [0.07, 0.525] |

| Outcome | 1.180 | [0.85, 1.47] | 0.998 | [0.638, 1.368] | −0.338 | [−0.593, −0.101] |

| Residual Variance: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 0.350 | [0.229, 0.453] | 0.385 | [0.254, 0.504] | 0.349 | [0.231, 0.453] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.450 | [0.222, 0.683] | 0.483 | [0.247, 0.725] | 0.450 | [0.222, 0.68] |

| Outcome | 0.463 | [0.288, 0.596] | 0.881 | [0.598, 1.111] | 0.620 | [0.4, 0.833] |

| Jordan | ||||||

| Intercepts: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | −0.301 | [−0.651, 0.096] | −0.066 | [−0.356, 0.254] | −0.314 | [−0.663, 0.074] |

| Maternal Affection | 0.268 | [−0.032, 0.524] | 0.193 | [−0.111, 0.446] | 0.269 | [−0.023, 0.526] |

| Outcome | 0.173 | [−0.13, 0.467] | −0.379 | [−0.677, −0.091] | 0.447 | [−0.066, 0.936] |

| Residual Variance: | ||||||

| Harsh Maternal Parenting | 1.288 | [0.843, 1.763] | 1.332 | [0.915, 1.788] | 1.280 | [0.84, 1.746] |

| Maternal Affection | 1.148 | [0.773, 1.505] | 1.236 | [0.832, 1.644] | 1.145 | [0.779, 1.492] |

| Outcome | 1.200 | [0.817, 1.563] | 1.102 | [0.639, 1.564] | 0.774 | [0.468, 1.036] |

Note: Parameter estimates that differed in some sites are denoted in parenthesis.

Jordan: 0.654 [0.134, 1.156];

Jordan: 0.513 [0.123, 0.887];

Colombia: 0.607 [0.333, 0.873] and Philippines: 0.446 [0.233, 0.640];

Colombia: −0.469 [−0.804, −0.144];

Philippines: 0.373 [0.203, 0.590];

China: −0.502 [−0.765, −0.275] and Jordan: −0.695 [−1.056, −0.359];

Philippines: −0.112 [−0.183, −0.052];

Philippines: −0.024 [−0.072, 0.008];

Colombia: −0.844 [−1.300, −0.400];

Philippines: 0.285 [0.062, 0.526];

Jordan: −0.713 [−1.094, −0.349];

Jordan: 0.660 [0.152, 1.176];

Jordan: 0.521 [0.134, 0.885];

Jordan: 0.403 [0.126, 0.696];

Kenya: 0.465 [0.024, 0.926];

China: −0.504 [−0.752, −0.276] and Jordan: −0.689 [−1.050, −0.362].

Looking first at the predictors of parenting behaviors, across sites without exception, greater chaos in the home predicted lower maternal affection and greater harsh maternal parenting. Effects in SD units are reported in Fig. 1 with 95% CIs. For example, for the path between chaos and affection, across all sites a 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a −0.299 SD decrease in affection. In contrast, a 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.352 SD increase in harsh parenting. Regarding neighborhood danger, across all sites, greater danger predicted greater harsh maternal parenting higher; in contrast, there were no significant links with affection. A 1 SD increase in neighborhood danger predicted a 0.122 SD increase in harsh parenting.

Turning to the predictors of externalizing behaviors, greater harsh maternal parenting predicted higher externalizing problems in all sites. One SD increase in harsh maternal parenting predicted a 0.300 SD increase in externalizing problems. Across all sites except the Philippines, there was not a significant link between maternal affection and externalizing behavior. In the Philippines, a 1 SD increase in affection predicted a 0.373 increase in externalizing behaviors (significantly different from the other sites, W (1) = 8.218, p = 0.004).

Indirect Effects.

The indirect effects between chaos and externalizing problems via harsh maternal parenting were significant for all sites. A 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.105 SD increase in externalizing behaviors via harsh parenting. The indirect effect of chaos on externalizing behaviors through maternal affection was only significant in the Philippines. In the Philippines, 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a −0.112 SD decrease in externalizing behaviors via maternal affection (significantly different from the other sites, W (1) = 9.299, p = 0.0023). After accounting for indirect effects, there remained a significant direct effect from chaos to externalizing behaviors in two of the six sites. In Colombia, a 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.607 SD increase in externalizing problems, and a 1 SD increase in chaos in the Philippines predicted a 0.446 SD increase in externalizing problems (significantly different from the other sites, W (1) = 18.914, p < 0.0001 for Colombia; 9.238, p = 0.002 for the Philippines).

Turning to the indirect effect of higher neighborhood danger, greater danger indirectly predicted higher externalizing behaviors via harsh maternal parenting in all sites. A 1 SD increase in neighborhood danger predicted a 0.037 SD increase in externalizing behaviors via harsh parenting. There was not a significant indirect effect of neighborhood danger on externalizing behaviors via maternal affection for any site.

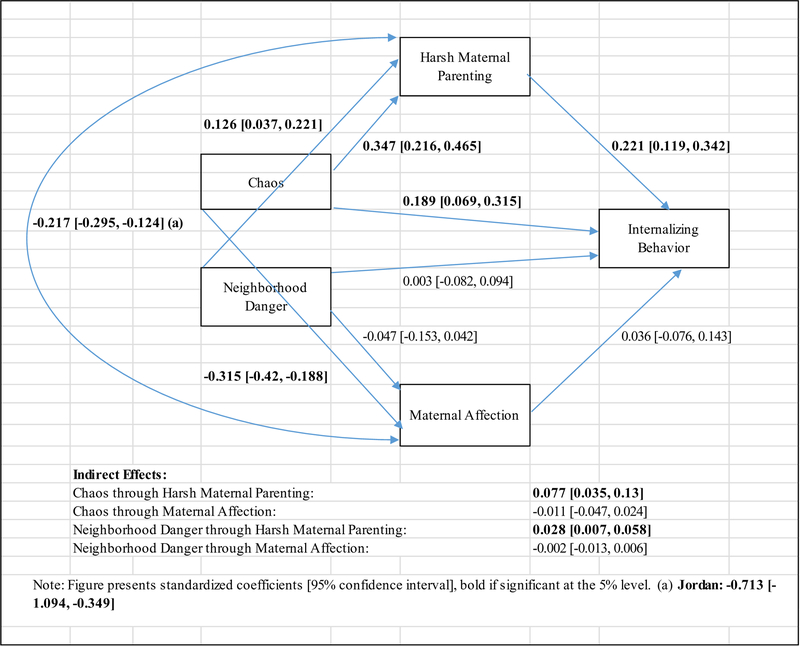

Internalizing Problems

Figure 2 summarizes results for internalizing problems. A full reporting of all parameter estimates for all sites is provided in Table 3. Optimal fit was not initially achieved when all 18 paths were fixed across the six sites (χ2 p = 0.001, RMSEA = 0.077, CFI = 0.801, TLI = 0.762, SRMA = 0.095). However, after releasing three site-level paths (described in Table 3), optimal fit was achieved (χ2 p = 0.061, RMSEA = 0.051, CFI = 0.914, TLI = 0.894, SRMA = 0.085).

Figure 2:

Full-Information Maximum Likelihood Multi-Group Path Model Estimating Internalizing Problems

The predictive effects of chaos and danger for maternal affection and harsh parenting were nearly identical to those reported for externalizing problems so are not repeated here. Regarding the paths from parenting to internalizing behaviors (see Fig. 2), as with externalizing behaviors (Fig. 1), greater harsh maternal parenting predicted more internalizing problems in all sites. One SD increase in harsh maternal parenting predicted a 0.221 SD increase in internalizing problems. There was no significant link between maternal affection and internalizing behaviors in any site.

Indirect Effects.

The indirect effects between chaos and internalizing problems via harsh maternal parenting were significant for all sites. A 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.077 SD increase in internalizing behaviors via harsh parenting. The indirect effect of chaos on internalizing behaviors through maternal affection was not significant for any site. After accounting for indirect effects, there remained a significant direct effect from chaos to internalizing behaviors in all sites. A 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.189 SD increase in internalizing behaviors.

Turning to the indirect effect of higher neighborhood danger, greater danger indirectly predicted higher internalizing behaviors via harsh maternal parenting in all sites. A 1 SD increase in neighborhood danger predicted a 0.028 SD increase in internalizing behaviors via harsh parenting. There was not a significant indirect effect of neighborhood danger on internalizing behaviors via maternal affection for any site. After accounting for indirect effects, the direct effect of neighborhood danger on internalizing behaviors was not significant.

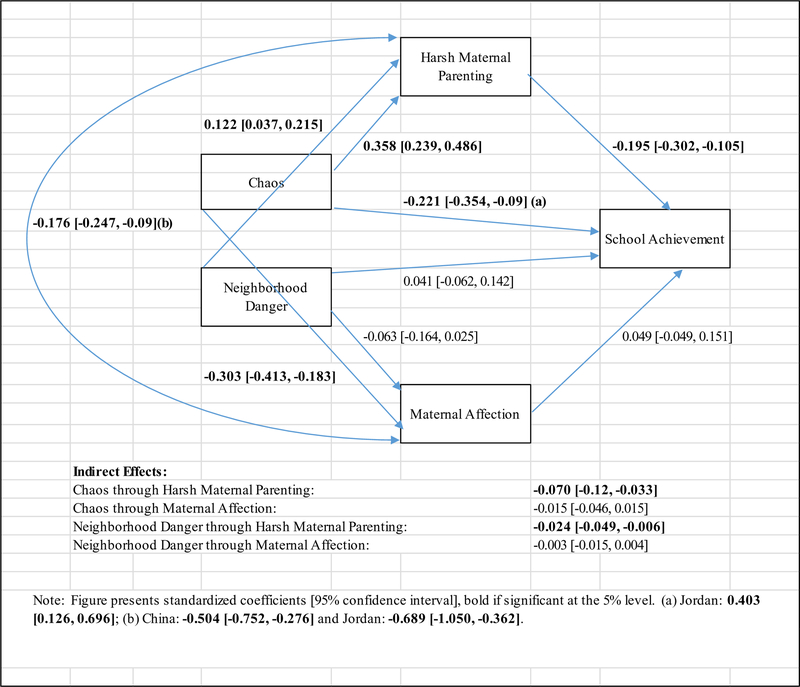

Problems in School Performance

Figure 3 summarizes results for school performance. A full reporting of all parameter estimates for all sites is provided in Table 3. Optimal fit was not initially achieved when all 18 paths were fixed across the six sites (χ2 p = 0.000, RMSEA = 0.090, CFI = 0.789, TLI = 0.746, SRMA = 0.096). However, after releasing six site-level paths (described in Table 3), optimal fit was achieved (χ2 p = 0.089, RMSEA = 0.048, CFI = 0.942, TLI = 0.927, SRMA = 0.081). The predictive effects of chaos and danger for maternal affection and harsh parenting were nearly identical to those reported for externalizing and internalizing problems so are not repeated here.

Figure 3:

Full-Information Maximum Likelihood Multi-Group Path Model Estimating School Performance

Greater harsh maternal parenting predicts lower school performance in all sites. One SD increase in harsh maternal parenting predicted a −0.195 SD decrease in school. There was no significant link between maternal affection and school performance in any site.

Indirect Effects.

The indirect effect between chaos and school performance via harsh maternal parenting was significant for all sites. A 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.070 SD decrease in school performance via harsh parenting. The indirect effect of chaos on school performance through maternal affection was not significant for any site. After accounting for indirect effects, there remained a significant and negative direct effect from chaos to school performance in all sites except Jordan. A 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.221 SD decrease in school performance. In Jordan, a 1 SD increase in chaos predicted a 0.403 SD increase in school performance (significantly different from the other sites, W (1) = 11.819, p = 0.001).

Turning to the indirect effect of higher neighborhood danger, greater danger indirectly predicted lower school performance via harsh maternal parenting. A 1 SD increase in neighborhood danger predicted a 0.024 SD decrease in school performance via harsh parenting in all sites. There was no significant indirect effect of neighborhood danger on school performance via maternal affection for any site. After accounting for indirect effects, the direct effect of neighborhood danger on school performance was not significant.

Discussion

The goal of the current study of families in six LMICs was to test a hypothesized mediation model, whereby greater household chaos and neighborhood danger at 13 years of age predicted subsequent harsher (i.e., hostility, neglect, rejection, and psychological control) and less affectionate maternal parenting at 14 years of age, which in turn predicted adolescent maladjustment at 15 years of age. Overall, significant paths were consistent across countries, and the “signs” of hypothesized effects (i.e., positive or negative coefficient) were as expected. However, a few of the effects were site-specific, and the indirect effect sizes were modest in magnitude.

With these general points in mind, several major findings emerged that supported the hypothesis. There were longitudinal associations between higher chaos and danger, and greater maternal harsh parenting and less maternal affection. These effect sizes were generally consistent across sites, ranging from .122 to .352 (with a few exceptions as noted in Results). In addition, there were six significant longitudinal indirect effects from chaos and danger to all three youth outcomes via harsher parenting (indirect effect sizes of .024 to .105; see Figs. 1–3). This range of modest yet significant indirect effects is typical when estimating mediated effects over several years, especially when individual differences in the constructs are moderately stable over time.

Significant effects were largest and most consistent for maternal hostility (as opposed to affection). Furthermore, direct and indirect effects were generally similar for externalizing problems, internalizing problems, and scholastic outcomes. For every site, higher levels of household chaos and neighborhood danger longitudinally predicted greater maternal hostility, which in turn predicted subsequent youth externalizing and internalizing behaviors, and poorer school performance. The overall pattern of significant effects was consistent with the literature from high-income (typically Western) country samples (Cantillon, 2006; Coldwell et al., 2006; Deater-Deckard et al., 2009; Dodge et al., 2008; Evans & Wachs, 2010; Gonzales et al., 2011; Li et al., 2017; Mills-Koonce et al., 2016; Mrug & Windle, 2009; Roosa et al., 2002; Valiente et al., 2007).

It is noteworthy that like the current results, prior cultural comparative work also pointed to similarities rather than differences between wealthy versus poorer countries in the direction and magnitude of the associations between chaos, neighborhood danger, harsher parenting, and child maladjustment (Evans & Wachs, 2010; Ferguson et al., 2013; Skinner et al., 2014; Wachs & Corapci, 2003). The similarity in effect sizes is particularly noteworthy, when one considers that there are much higher levels of poverty, crime, and social disarray in many LMICs compared to high-income countries; this may alter risk and resilience processes, and the statistical effects detected in studies (Barry, Clarke, Jenkins, & Patel, 2013). In addition, the current study joins several others in addressing the gap in research on adolescent (rather than childhood) maladjustment and family SES, chaos and danger (Devenish et al., 2017; King & Mrug, 2018; Li et al., 2017; McDermott et al., 2017). The similar effects across age in the literature may be due in part to the longitudinally stable or “chronic” presence of levels of household chaos and neighborhood danger.

Several theories provide a lens for interpreting the major result of an indirect effect on adjustment problems via harsher maternal parenting. Social learning, family stress and coercion theory stipulate that harsh, reactive, hostile caregiver behavior serves a modeling and reinforcing role in aggressive and non-aggressive behavioral and emotional problems that can also impair scholastic functioning—for children and teenagers alike (Dishion & Snyder, 2016). More broadly, problematic parent-youth relationship dynamics reflected in harsh caregiving behavior arise in part in response to a chronically chaotic and dangerous home and neighborhood environment. In turn, this can contribute to growth in youth maladjustment. Thus, parenting can serve as a proximal risk factor through which flow the effects of more distal stressors (Bronfenbrenner, 2005). However, research on high-income and LMICs also shows that a focus on any particular mediator—such as maternal parenting in the current study—typically underestimates effects that arise from cumulative risk exposure spanning home and neighborhood chaos and danger, parenting, and other proximal and distal risk factors (Wachs, Cueto, & Yao, 2016). Nevertheless, parenting is a worthwhile target for prevention and intervention, and is one of the key malleable factors for reducing adolescent maladjustment.

There are limitations of the current research that must be considered. We did not have chaos and danger measured at all three waves, nor did we have all informants reporting on parenting and youth adjustment at all three waves. Therefore, it was not possible to test models with a complete multivariate longitudinal design. It is plausible that adolescent adjustment problems and parenting are contributing over time to changes in household chaos, for instance; we were not able to test for that or other competing longitudinal direct or indirect effects. With a complete longitudinal measurement design, it would be plausible (and preferred) to test competing indirect mediated pathways, to infer with more confidence the potential temporal patterns of effects. More generally, the data were correlational; causal effects could not be determined. In addition, the measure of school performance was very general and did not capture potentially essential details of individual differences in adolescents’ academic competencies.

Another shortcoming is that we did not test measurement invariance across sites. Full measurement invariance in multi-sample studies is the gold standard, but the probability was low of achieving this across six diverse countries. In addition, the samples were arguably too small at each site for conducting measurement invariance testing (Meade & Lautenschlager, 2004), and aside from statistical power limitations there are questions as to whether stringent confirmatory factor analysis measurement assumptions should be applied to subjective psychological measures (Marsh et al., 2009). Also, the absence of measurement invariance does not necessarily change findings of a study (Borsboom, 2006). For example, if country variation in differential item functioning (DIF) is not systematic and the effects “wash out” across item sets and countries, measurement metric equivalence will not be achieved.

Turning to a different measurement issue, the internal-consistency alpha coefficient for the chaos scale ranged from .35 to .75 (unweighted average = .61), raising concerns about its reliability. However, we retained it because the alpha coefficients were in line with previously published studies. Finally, although sampling in six LMICs was a novel feature of the design, the samples were not nationally representative. Therefore, caution is warranted when attempting to draw conclusions about potential cultural differences in the neighborhood and home environments and their potential effects on growth in adolescent problem behaviors.

In closing, the current findings should be interpreted within the broader context of cross-national comparative studies of child and adolescent development. None of those has focused specifically on chaos and danger. However, they have yielded a wealth of new knowledge about the differential and universal correlates and predictors (e.g., poverty, access to childcare and healthcare, exposure to violence) of adjustment and maladjustment across development, between low-to-high income national contexts (e.g., the Young Lives Project, https://www.younglives.org.uk/; the current Parenting Across Cultures project, http://parentingacrosscultures.org/). In addition, there is a vast literature on nation-, culture- and context-specific research in various social and behavioral science fields (e.g., anthropology, cultural psychology, sociology) that argue against reliance on “etic” methods like those used in the current study (Kagitcibasi, 2017). Using statistical comparisons of scores on measures not originally developed for the nations and cultural groups being studied provides only one viewpoint on such data. This information does not capture the much wider variety of indicators of household and neighborhood dynamics, parenting processes, and adolescent adjustment that do not lend themselves to direct quantitative comparisons. Nevertheless, with these caveats in mind, the current study presents clear evidence that harsher maternal parenting explains some of the well-established connections among chaos, neighborhood danger, and adolescent externalizing behavior problems—and does so consistently across a variety of families in low-, middle- and high-income countries.

Research Highlights.

There is a need for longitudinal studies in low- and middle-income countries on links between home and neighborhood risk factors, parenting, and adolescent adjustment

The current longitudinal study spanning the transition to adolescence involved 511 families in six LMICs: China, Colombia, Jordan, Kenya, the Philippines, and Thailand

Household chaos and neighborhood danger (13 years old) predicted harsher maternal parenting (14 years), which predicted more externalizing, internalizing and scholastic problems (15 years)

Overall, significant effects were consistent across the six countries, with a few exceptions

Acknowledgement

This research has been funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development grant RO1-HD054805, Fogarty International Center grant RO3-TW008141, and the Jacobs Foundation. This research also was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH/NICHD, USA, and an International Research Fellowship in collaboration with the Centre for the Evaluation of Development Policies (EDePO) at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), London, UK, funded by the European Research Council (ERC) under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement No 695300-HKADeC-ERC-2015-AdG). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or NICHD.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Contributor Information

Kirby Deater-Deckard, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA,.

Jennifer Godwin, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA,.

Jennifer E. Lansford, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA,

Liliana Maria Uribe Tirado, Universidad San Buenaventura, Medellín, Colombia,.

Saengduean Yotanyamaneewong, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand,.

Liane Peña Alampay, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, Philippines,.

Suha M. Al-Hassan, Hashemite University, Zarqa, Jordan, and Emirates College for Advanced Education, Abu Dhabi, UAE,

Dario Bacchini, University of Naples “Federico II,” Naples Italy,.

Marc H. Bornstein, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda, MD, USA, USA, and Institute for Fiscal Studies, London, UK

Lei Chang, University of Macau, China,.

Laura Di Giunta, Università di Roma “La Sapienza,” Rome, Italy,.

Kenneth A. Dodge, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA,

Paul Oburu, Maseno University, Maseno, Kenya,.

Concetta Pastorelli, Università di Roma “La Sapienza,” Rome, Italy,.

Ann T. Skinner, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA,

Emma Sorbring, University West, Trollhättan, Sweden,.

Laurence Steinberg, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA, and King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Sombat Tapanya, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand,.

References

- Achenbach TM (1991). Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL 14–18, YSR, and TRF Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA, & Ivanova MY (2012). International epidemiology of child and adolescent psycho-pathology: Diagnoses, dimensions, and conceptual issues. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51, 1261–1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aikens NL, & Barbarin O (2008). Socioeconomic differences in reading trajectories: The contribution of family, neighborhood, and school contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth JW (2002). Why does it take a village? The mediation of neighborhood effects on educational achievement. Social Forces, 81(1), 117–152. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Olsen JE, & Shagle SC (1994). Association between psychological and behavioral control and youth internalized and externalized behavior. Child Development, 65, 1120–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry MM, Clarke AM, Jenkins R, & Patel V (2013). A systematic review of the effectiveness of mental health promotion interventions for young people in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry D, Blair C, Willoughby M, Garrett-Peters P, Vernon-Feagans L, Mills-Koonce WR, & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2016). Household chaos and children’s cognitive and socio-emotional development in early childhood: Does childcare play a buffering role? Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 34, 115–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair C, Ursache A, Greenberg M, & Vernon-Feagans L (2015). Multiple aspects of self-regulation uniquely predict mathematics but not letter–word knowledge in the early elementary grades. Developmental Psychology, 51(4), 459–472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom D (2006). When does measurement invariance matter? Medical Care, 44(11), S176–S181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brieant A, Holmes C, Deater-Deckard K, King-Casas B, & Kim-Spoon J (2017). Household chaos as a context for intergenerational transmission of executive functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 58, 40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (2005). The bioecological theory of human development In Bronfenbrenner U (Ed.), Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development (pp. 3–15). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cantillon D (2006). Community social organization, parents, and peers as mediators of perceived neighborhood block characteristics on delinquent and prosocial activities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 37(1–2), 413–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colder CR, Mott J, Levy S, & Flay B (2000). The relation of perceived neighborhood danger to childhood aggression: A test of mediating mechanisms. American Journal of Community Psychology, 28(1), 83–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coldwell J, Pike A, & Dunn J (2006). Household chaos: Links with parenting and child behaviour. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47(11), 1116–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K (2013). The social environment and the development of psychopathology In Zelazo P (Ed.), Oxford Handbook of Developmental Psychology, Volume 2 (pp. 527–548). Oxford UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deater‐Deckard K, Mullineaux PY, Beekman C, Petrill SA, Schatschneider C, & Thompson LA (2009). Conduct problems, IQ, and household chaos: A longitudinal multi‐informant study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(10), 1301–1308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenish B, Hooley M, & Mellor D (2017). The pathways between socioeconomic status and adolescent outcomes: A systematic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 59(1–2), 219–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion T, & Snyder J (Eds.) (2016). Oxford handbook of coercive dynamics in close relationships. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dodge KA, Greenberg MT, Malone PS, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group. (2008). Testing an idealized dynamic cascade model of the development of serious violence in adolescence. Child Development, 79(6), 1907–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eamon MK (2005). Social-demographic, school, neighborhood, and parenting influences on the academic achievement of Latino young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(2), 163–174. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW (2004). The environment of childhood poverty. American Psychologist, 59(2), 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, Gonnella C, Marcynyszyn LA, Gentile L, & Salpekar N (2005). The role of chaos in poverty and children’s socioemotional adjustment. Psychological Science, 16(7), 560–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Kim P (2013). Childhood poverty, chronic stress, self‐regulation, and coping. Child Development Perspectives, 7(1), 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Evans GW, & Wachs TD (Eds.) (2010). Chaos and its influence on children’s development. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Fan X, & Chen M (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 13(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson KT, Cassells RC, MacAllister JW, & Evans GW (2013). The physical environment and child development: An international review. International Journal of Psychology, 48(4), 437–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales NA, Coxe S, Roosa MW, White R, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, & Saenz D (2011). Economic hardship, neighborhood context, and parenting: Prospective effects on Mexican–American adolescent’s mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 47(1–2), 98–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KW, Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Diaz T, & Miller N (1999). Interpersonal aggression in urban minority youth: Mediators of perceived neighborhood, peer, and parental influences. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Hanscombe KB, Haworth C, Davis OS, Jaffee SR, & Plomin R (2011). Chaotic homes and school achievement: A twin study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(11), 1212–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges RF, & Wang MT (2018). Gender differences in the developmental cascade from harsh parenting to educational attainment: an evolutionary perspective. Child Development, 89(2), 397–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings WG, Perez NM, & Reingle Gonzalez JM (2018). Conduct disorders and neighborhood effects. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 317–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jocson RM, & McLoyd VC (2015). Neighborhood and housing disorder, parenting, and youth adjustment in low‐income urban families. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(3–4), 304–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson AD, Martin A, Brooks-Gunn J, & Petrill SA (2008). Order in the house! Associations among household chaos, the home literacy environment, maternal reading ability, and children’s early reading. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54(4), 445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson TM, & Grim BJ (Eds). (2018). World religion database. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Kagitcibasi C (2017). Family, self, and human development across cultures. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Kahn R, Deater-Deckard K, King-Casas B, & Kim-Spoon J (2016). Intergenerational similarity in callous-unemotional traits: Contributions of hostile parenting and household chaos during adolescence. Psychiatry Research, 246, 815–820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King VL, & Mrug S (2018). The relationship between violence exposure and academic achievement in African American adolescents is moderated by emotion regulation. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(4), 497–512. [Google Scholar]

- Kohen DE, Leventhal T, Dahinten VS, & McIntosh CN (2008). Neighborhood disadvantage: Pathways of effects for young children. Child Development, 79(1), 156–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, & McMahon RJ (2000). Parent involvement in school conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. Journal of School Psychology, 38(6), 501–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauharatanahirun N, Maciejewski D, Holmes C, Deater-Deckard K, Kim-Spoon J, & King-Casas B (2018). Neural correlates of risk processing among adolescents: Influences of parental monitoring and household chaos. Child Development, 89(3), 784–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, & Brooks-Gunn J (2000). The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 309–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Johnson SB, Musci RJ, & Riley AW (2017). Perceived neighborhood quality, family processes, and trajectories of child and adolescent externalizing behaviors in the United States. Social Science & Medicine, 192, 152–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Muthén B, Asparouhov A, Lüdtke O, Robitzsch A, Morin AJS, … Trautwein U (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling, integrating CFA and EFA: Application to students’ evaluations of university teaching. Structural Equation Modeling, 16, 439–476. [Google Scholar]

- Matheny AP, Wachs TD, Ludwig J, & Phillips K (1995). Bringing order out of chaos: Psychometric characteristics of the Confusion, Hubbub, and Order Scale. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16, 429–444. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott ER, Donlan AE, Anderson S, & Zaff JF (2017). Self-control and adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems: Neighborhood-based differences. Journal of Community Psychology, 45(3), 297–314. [Google Scholar]

- Meade AW, & Lautenschlager GJ (2004). A comparison of item response theory and confirmatory factor analytic methodologies for establishing measurement equivalence/invariance. Organizational Research Methods, 7(4), 361–388. [Google Scholar]

- Mills-Koonce WR, Willoughby MT, Garrett-Peters P, Wagner N, Vernon-Feagans L, & Family Life Project Key Investigators. (2016). The interplay among socioeconomic status, household chaos, and parenting in the prediction of child conduct problems and callous–unemotional behaviors. Development and Psychopathology, 28(3), 757–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkov M, Dutt P, Schachner M, Morales O, Sanchez C, Jandosova J, … & Mudd B (2017). A revision of Hofstede’s individualism-collectivism dimension: A new national index from a 56-country study. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24(3), 386–404. [Google Scholar]

- Mrug S, & Windle M (2009). Mediators of neighborhood influences on externalizing behavior in preadolescent children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(2), 265–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwenhuis J, & Hooimeijer P (2016). The association between neighbourhoods and educational achievement, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31(2), 321–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil R, Parke RD, McDowell DJ (2001). Objective and subjective features of children’s neighborhoods: Relations to parental regulatory strategies and children’s social competence. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 22, 135–155. [Google Scholar]

- Petrill SA, Pike A, Price T, & Plomin R (2004). Chaos in the home and socioeconomic status are associated with cognitive development in early childhood: Environmental mediators identified in a genetic design. Intelligence, 32(5), 445–460. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M (2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 873–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raver CC, Blair C, Garrett-Peters P, & Family Life Project Key Investigators (2015). Poverty, household chaos, and interparental aggression predict children’s ability to recognize and modulate negative emotions. Development and Psychopathology, 27(3), 695–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohner RP (2005). Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire (PARQ): Test manual In Rohner RP & Khaleque A (Eds.), Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection (4th ed., pp. 43–106). Storrs, CT: Center for the Study of Parental Acceptance and Rejection, University of Connecticut. [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Deng S, Ryu E, Lockhart Burrell G, Tein JY, Jones S, … & Crowder S (2005). Family and child characteristics linking neighborhood context and child externalizing behavior. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67(2), 515–529. [Google Scholar]

- Sirin SR (2005). Socioeconomic status and academic achievement: A meta-analytic review of research. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 417–453. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner AT, Bacchini D, Lansford JE, Godwin JW, Sorbring E, Tapanya S, … & Bombi AS (2014). Neighborhood danger, parental monitoring, harsh parenting, and child aggression in nine countries. Societies, 4(1), 45–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente C, Lemery‐Chalfant K, & Reiser M (2007). Pathways to problem behaviors: Chaotic homes, parent and child effortful control, and parenting. Social Development, 16(2), 249–267. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon-Feagans L, Garrett-Peters P, Willoughby M, & Mills-Koonce R (2012). Chaos, poverty, and parenting: Predictors of early language development. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27(3), 339–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wachs TD, & Corapci F (2003). Environmental chaos, development, and parenting across cultures In Benson J & Raeff C (Eds.), Social and cognitive development in the context of individual, social, and cultural processes (pp. 54–83). London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Wachs TD, Cueto S, & Yao H (2016). More than poverty: Pathways from economic inequality to reduced developmental potential. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(6), 536–543. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank (2019). Data: World Bank country and lending groups. URL: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed May 8, 2019.

- [dataset] Parenting Across Cultures Work Group; 2019; Parenting Across Cultures; Duke University; www.parentingacrosscultures.org [Google Scholar]