Abstract

Objective

To examine the efficacy and safety of a sequential combination of chemotherapy and autologous cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cell treatment in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) patients.

Methods

A total of 294 post-surgery TNBC patients participated in the research from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2015. After adjuvant chemotherapy, autologous CIK cells were introduced in 147 cases (CIK group), while adjuvant chemotherapy alone was used to treat the remaining 147 cases (control group). The major endpoints of the investigation were the disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS). Additionally, the side effects of the treatment were evaluated.

Results

In the CIK group, the DFS and OS intervals of the patients were significantly longer than those of the control group (DFS: P = 0.047; OS: P = 0.007). The multivariate analysis demonstrated that the TNM (tumor-node-metastasis) stage and adjuvant CIK treatment were independent prognostic factors for both DFS [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.520, 95% confidence interval (CI):0.271-0.998, P = 0.049; HR = 1.449, 95% CI:1.118-1.877, P = 0.005, respectively] and OS (HR=0.414, 95% CI:0.190-0.903, P = 0.027; HR = 1.581, 95% CI:1.204-2.077, P = 0.001, respectively) in patients with TNBC. Additionally, longer DFS and OS intervals were associated with increased number of CIK treatment cycles (DFS: P = 0.020; OS: P = 0.040). The majority of the patients who benefitted from CIK cell therapy were relatively early-stage TNBC patients.

Conclusion

Chemotherapy in combination with adjuvant CIK could be used to lower the relapse and metastasis rate, thus effectively extending the survival time of TNBC patients, especially those at early stages.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, triple-negative breast cancer, cytokine-induced killer cell, prognosis, disease-free survival, overall survival

Introduction

As a subtype of breast cancer, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined by the lack of estrogen receptors (ERs), progesterone receptors (PRs), and the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). The TNBC constitutes up to 15% to 20% of all pathological types of breast cancer, with a tendency towards aggressive behavior, clinically shown by younger onset age, higher histological grade and distant metastasis rate, as well as poorer prognosis1. As the TNBC patients are not eligible for conventional targeted therapies for lacking the molecular target renders, chemotherapy based on anthracyclines and taxanes is currently the main post-surgical therapeutic strategy2. However, the recurrence rate in patients with TNBC remains at a high level, leading to a significant decline in survival rate in the initial 3 to 5 years after surgery3. Therefore, exploring novel therapeutic strategies is an important clinical challenge in treating TNBC.

Based on the gene expression data, TNBC was categorized by Lehmann et al.4 into 6 subtypes, including basel-like 1 and 2 (BL1 and BL2), mesenchymal (M), immunomodulatory (IM), mesenchymal stem-like (MSL), and luminal androgen receptor (LAR). TNBC is a heterogeneous disease with varied sensitivity to different therapies. The IM subtype (featured by enhanced expression of immune genes) indicates that immune-based therapies might be beneficial to some of the TNBC patients5. Therefore, chemotherapies coupled with immunotherapies may be considered as an alternative option for treating TNBC patients.

The principle of adoptive immunotherapy is to collect the immune cells from the human body, and then transmit them back to the human body for anti-tumor activity, after an in vitro transformation and expansion. Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells are defined as a subset of cytotoxic T lymphocytes with an immunophenotype of CD3+CD56+. The CIK cells have been proven to be ideal for use in immunotherapy as they can reproduce rapidly outside the human body and directly kill tumor cells6, thereby regulating and enhancing host cell immune function in vivo7. Compared with another cytotoxic effector T cells, named lymphokine-activated killer (LAK) cells, the CIK cells present enhanced tumor cell lytic activity and reproduction rate, and lowered toxicity8. Subsequently, CIK cell-based therapy has been broadly adopted as an adjuvant treatment combined with chemotherapy for treating multiple types of cancers, such as renal cell carcinoma9, gastric cancer10, non-small cell lung cancer11, colon cancer12, and liver cancer13, with great efficacy and safety.

However, a few studies have been conducted on the efficacy of CIK treatment in breast cancer, especially in TNBC. The existing clinical studies on treating breast cancer with CIK cells have mostly concentrated on advanced or metastatic breast cancer14-17. These studies have shown that CIK cell therapy can be used as a rescue therapy to facilitate the prognosis of advanced or metastatic breast cancer, and to improve the patient’s quality of life. Therefore, a clinical retrospective study regarding the efficacy of CIK cell therapy on the prognosis of postoperative TNBC patients was performed.

Materials and methods

Patients

A retrospective study was conducted to examine the clinical outcomes of autologous CIK immunotherapy in TNBC patients after surgery. The patients were recruited to the study from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2015. In the CIK group, 147 postoperative TNBC patients received autologous CIK cells after chemotherapy. Concomitantly, 147 participants (control group) were selected that received chemotherapy alone after the surgery, and also matched with age ± 1 year to the index patients. The following is the brief outline of patient enrollment procedure in the control group: Initially, between January 1, 2009 and January 1, 2015, a review of the medical records of patients diagnosed with TNBC from a computerized database in our hospital was performed; then, the matching cases were selected in accordance with the enrollment and exclusion criteria; finally, matching patients with same age as those in CIK group were chosen; if there is no same-aged case as that of patients in CIK group, the cases with age ±1 were selected randomly; if there are more than one same-aged cases, then one case was selected randomly by random number method.

The following were the inclusion criteria for selecting patients: 1) The selected patients must be histologically diagnosed with TNBC. TNBC is defined by the immunohistochemical staining feature of ER, PR, and HER2. The staining feature categorization is as follow: ER and PR negative is defined as ER and PR staining < 1%; HER2 negative is defined as HER2 staining 0 to 2+ by, or a nonamplified HER2 by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH); 2) No occurrence of distant metastasis prior to surgery; 3) Absence of other malignant tumor; 4) Karnofsky performance status score higher than 70 %; 5) Reception of CIK treatment before disease progression. The exclusion criteria were as below: 1) absence of adjuvant chemotherapy, or inability to tolerate or complete the chemotherapy due to serious adverse reactions; 2) severe disease of heart, lung, liver or kidney, bone marrow dysfunction, autoimmune diseases; 3) pregnancy or lactation. Guided by the Declaration of Helsinki, this study has been authorized by the Ethics Committee of Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital (Approval No. bc2019024) and by the State Food and Drug Administration of China (No. 2006L01023). The detailed clinical characteristics of patients in the both groups are shown in the Supplementary Table S1.

1.

Clinical characteristics of patients in the two groups

| Characteristics | CIK group | Control group | P |

| Patients, n | 147 | 147 | |

| Age (years) | 1.000 | ||

| < 35 | 9 | 9 | |

| ≥ 35 | 138 | 138 | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.644 | ||

| ≤ 2 | 64 | 68 | |

| > 2, ≤ 5 | 65 | 58 | |

| > 5 | 11 | 14 | |

| Unable to value | 7 | 7 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.338 | ||

| Yes | 53 | 61 | |

| No | 94 | 86 | |

| TNM stage | 0.064 | ||

| I | 46 | 43 | |

| IIa | 56 | 56 | |

| IIb | 23 | 11 | |

| IIIa | 5 | 14 | |

| IIIb | 1 | 2 | |

| IIIc | 9 | 15 | |

| Unable to value | 7 | 6 | |

| Histological grade | 0.365 | ||

| 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| 2 | 89 | 88 | |

| 3 | 58 | 57 | |

| Pathological type | 0.069 | ||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma | 138 | 129 | |

| Others | 9 | 18 | |

| Surgery | 0.469 | ||

| Radical mastectomy | 24 | 17 | |

| Modified radical mastectomy | 110 | 118 | |

| Breast-conserving surgery | 13 | 12 | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.162 | ||

| Yes | 38 | 28 | |

| No | 109 | 119 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 1.000 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 21 | |

| No | 126 | 126 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy regimens | 0.319 | ||

| Anthracycline-based | 17 | 10 | |

| Anthracycline-and taxane-based | 113 | 122 | |

| Taxane-based | 17 | 15 |

Treatments

All participating patients underwent modified radical mastectomy, radical mastectomy, or breast-conserving surgery. Postoperatively, these patients underwent 4 to 8 cycles of standard adjuvant chemotherapy in accordance with the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Chemotherapy regimens involved anthracycline-based [AC (adriamycin 60 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 d1, 21 days a cycle) or EC (epirubicin 90 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 d1, 21 days a cycle) or CAF (5-Fu 500 mg/m2, adriamycin 50 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 d1, 21 days a cycle) or CEF (5-Fu 500 mg/m2, epirubicin 100 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 d1, 21 days a cycle)], anthracycline- and taxane-based [TAC (docetaxel 75 mg/m2, adriamycin 50 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 500 mg/m2 d1, 21 days a cycle) or AC-T (adriamycin 60 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 d1, 4 cycles, docetaxel 80-100 mg/m2 d1, 4 cycles, 21 days a cycle)], or taxane-based [TC (docetaxel 75 mg/m2, cyclophosphamide 600 mg/m2 d1, 21 days a cycle)] regimens.

It was observed that some patients received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or adjuvant radiotherapy based on their clinical stage and operation. For all patients who are diagnosed with invasive breast cancer and choose breast-conserving surgery, whole breast radiotherapy (RT) is recommended. In cases of adjuvant RT after radical/modified radical mastectomy, radiation should be administered mainly to the ipsilateral chest wall and supraclavicular region on the same side as the tumor in patients with four or more positive axillary nodes, or with tumor ≥ 5 cm; for the patients with negative nodes or those with tumors < 5 cm, the guidelines recommend radiation to the chest wall. Patients with small tumors and no nodal involvement do not need to undergo radiation therapy. RT is administered to the chest wall with 6 MV X-ray at a total dose of 45-50 Gy with 1.8-2.0 Gy/fraction, 5 fractions/week. Introducing a boost to the tumor bed for patients with greater risk (age < 50 and high-grade disease) using doses of 10-16 Gy at 2 Gy/fx is recommended.

CIK cells preparation and injection

At least 2 weeks after the patients completed post-mastectomy chemotherapy (with/without radiotherapy) and when routine blood count returned to normal, 50 mL of peripheral blood samples were collected for the preparation of CIK cells. The previously published research9, 12, 18-20 has provided the detailed method of CIK preparation. In brief, to gather the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from TNBC patients, a COBE Spectra Apheresis System was used. The PBMCs were then cultured in a medium containing 1000 U/mL interferon-γ (IFN-γ), 100 U/mL recombinant human interleukin-1α (IL-1α), and 50 ng/mL anti-CD3 antibody, with 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 24 h, followed by the addition of 300 U/mL of recombinant human IL-2 to the medium. This medium was constantly replaced with a fresh medium containing IFN-γ and IL-2 every 5 days. By using this approach, a cellular subset with noticeably higher CD3+CD56+ was prepared. On the 14th day, the CIK cells were harvested. Eventually, over 5 × 109 of CIK cells with > 95% viability were obtained. No fungus, mycoplasma, or bacteria were found in the reagents.

In the CIK group, on day 15 and day 16 of each chemotherapy cycle, patients received an intravenous infusion of at least 5 × 109 CIK cells. During the input, routine body indexes, such as body temperature, heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, and other basic vital signs, were monitored. Maintenance treatment was accessible to these patients unless they refused to proceed or in case of recurrence or distant metastasis.

Follow-up and clinical assessment

From the date of surgery until May 1, 2018 or death, a follow-up was performed for all the patients. The median follow-up time was 75 months (ranging from 39-110 months). The overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were defined in accordance with the National Cancer Institute’s Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST)21. OS was measured from the date of surgery until decease and living patients were examined at the time of the last follow-up. DFS was calculated from the date of surgery until first recurrence or metastasis, or death from any cause. Patients that achieved a stable state were evaluated at the final follow-up. Besides, based on the criteria specified by the World Health Organization (WHO), adverse clinical activities were monitored and evaluated.

In the initial 2 years after the surgery, the follow-up was conducted in a 3-month cycle. The interval was extended to 6 months from year 2 through year 5, and annually thereafter. The reviewed patient records included breast ultrasound, breast tumor markers, mammography, X-ray or computed tomography (CT) on the chest, liver and abdomen ultrasound, bone scan, and head magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) if necessary. In this study, telephonic consultation was offered to each patient and no loss to follow-up was experienced.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to analyze the differences in variables of the two groups, in terms of both demographic and clinical characteristics. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to evaluate the survival time and rate distribution. The log-rank test univariate analyses were used to assess the relationship between survival and the potential prognostic factors. This was further verified by the multivariate analysis of Cox proportional hazards regression. Further, SPSS 20.0 software was used as a tool to analyze all the calculations. Statistical significance was considered at two-tailed P < 0.05 for all the calculations.

Results

Patients’ characteristics

This retrospective analysis involved total 294 patients, with 147 members in each group (CIK and control group). Each participant was compared to the matching patient from the other group for the time of diagnosis, age at onset of disease, pathological type, tumor size, TNM stage and regional lymph node metastasis at the first visit, operation and treatment, and subsequent therapies. It was found that there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (P > 0.05). Table 1 shows the data for all the patients.

Survival analysis

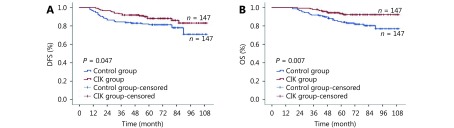

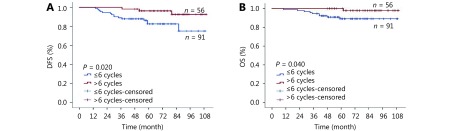

It was observed that the patients in the CIK group experienced significantly longer DFS intervals than their counterparts in the control group (P = 0.047, Figure 1A). DFS rates of the CIK and control group after 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals were 99.3% vs. 95.9%, 91.8% vs. 83.7%, and 88.1% vs. 81.3%, respectively. Similarly, the OS interval of the CIK group was significantly longer than that of the control group (P = 0.007, Figure 1B), and the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of the CIK and control group were 99.3% vs. 98.0%, 96.6% vs. 91.8%, and 93.4% vs. 84.1%, respectively. Therefore, compared to the control group patients treated with adjuvant chemotherapy (with or without radiotherapy), post-mastectomy TNBC patients, who received additional sequential CIK treatment, had significantly improved DFS and OS rates. In the CIK group, the median courses of CIK treatment were 6 cycles (range 1-26 cycles). Patients undergoing ≥ 6 cycles of CIK cell therapy had greater DFS (P = 0.020, Figure 2A) and OS (P = 0.040, Figure 2B) rates than those treated with < 6 cycles. Therefore, it can be inferred that longer CIK treatment courses are associated with better prognosis.

1.

Survival analysis of patients in cytokine-induced killer (CIK) group and control group. (A) Disease-free disease-free survival (DFS) curves. (B) Overall survival (OS) curves. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the DFS and OS between the CIKgroup and control group.

2.

Prognostic impact of the frequency of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) treatment on patients in the CIK group. (A) Disease disease-free survival (DFS) curves. (B) Overall survival (OS) curves. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to compare the survival rates between the patients in the CIK group underwent ≤ 6 cycles CIK cells injection and the patients in the CIK group underwent > 6 cycles CIK cells injection.

Until the completion of follow-up, recurrence or metastasis was observed in 16 patients in the CIK group, and 29 patients in the control group. Statistically, the two groups had no difference in the metastatic sites or the number of sites. It was found that the most common sites of distant metastases were the bone, lung, liver, and brain (Table 2).

2.

The details of recurrence and metastasis between the two groups

| CIK group (n = 16) | Control group (n = 29) | P | |

| Sites | 0.581 | ||

| Chest wall | 3/16 (18.8%) | 6/29 (20.7%) | |

| Regional lymph node | 4/16 (25.0%) | 5/29 (17.2%) | |

| Lung | 6/16 (37.5%) | 12/29 (41.4%) | |

| Bone | 6/16 (37.5%) | 9/29 (31.0%) | |

| Liver | 3/16 (18.8%) | 5/29 (17.2%) | |

| Brain | 3/16 (18.8%) | 4/29 (13.8%) | |

| Other sites | 1/16 (6.3%) | 2/29 (6.9%) | |

| Numbers of metastatic sites | 0.628 | ||

| 1 | 7/16 (43.7%) | 14/29 (48.3%) | |

| 2 | 1/16 (6.3%) | 4/29 (13.8%) | |

| ≥ 3 | 8/16 (50.0%) | 11/29 (37.9%) |

Subgroup analysis

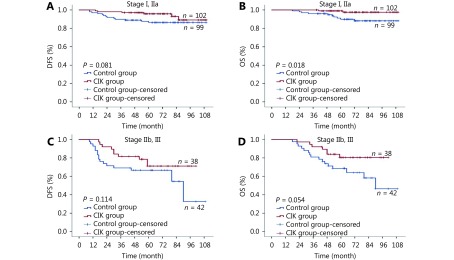

Further study was conducted to analyze the TNM stages of the patients that received better benefits from the CIK cell treatment. For this, all 294 patients were divided into an early-stage group (I, IIa stage) and a late-stage group (IIb, III stage), and a survival analysis of each subgroup was conducted. It was observed that the OS of TNBC patients in the early-stage group was extended by CIK treatment (P = 0.018, Figure 3B). However, such results were not obtained for the DFS (P = 0.081, Figure 3A; P = 0.114, Figure 3C) or the OS of late-stage TNBC patients (P = 0.054, Figure 3D).

3.

(A) Subgroup analysis to estimate the benefits of CIK treatment according to TNM stages. A, disease-free survival (DFS) curves of TNBC patients with stage I, IIa. (B) Subgroup analysis to estimate the benefits of CIK treatment according to TNM stages. B, overall survival (OS) curves of TNBC patients with stage I, IIa. (C) Subgroup analysis to estimate the benefits of CIK treatment according to TNM stages. A, disease-free survival (DFS) curves of TNBC patients with stage IIb, III. (D) Subgroup analysis to estimate the benefits of CIK treatment according to TNM stages. B, overall survival (OS) curves of TNBC patients with stage IIb, III.

Prognosis analysis

In the univariate and multivariate analysis, the impact of CIK treatment on the prognosis of post-surgery patients with TNBC was further evaluated. It was revealed by the log-rank test univariate analysis that the size of a tumor, TNM stage, lymph node metastasis, histological grade, radiotherapy, and CIK treatment were the prognostic factors influencing DFS and OS in TNBC patients. Additional Cox multivariate analysis showed that for TNBC patients, the adjuvant CIK treatment and TNM stage remained independent prognostic factors for both DFS (CIK treatment: HR = 0.520, 95% CI:0.271-0.998, P = 0.049; TNM stage: HR = 1.449, 95% CI:1.118-1.877, P = 0.005, respectively) and OS (CIK treatment: HR = 0.414, 95% CI:0.190-0.903, P = 0.027; TNM stage: HR = 1.581, 95% CI:1.204-2.077, P = 0.001, respectively, Table 3).

3.

Multivariate analysis of DFS and OS in patients with TNBC

| Parameter | DFS | OS | |||

| HR (95%CI) | P | HR (95%CI) | P | ||

| *P < 0.05 | |||||

| TNM stage | 1.449 (1.118-1.877) | 0.005* | 1.581 (1.204-2.077) | 0.001* | |

| Tumor size | 1.943 (0.847-4.459) | 0.117 | 2.018 (0.761-5.352) | 0.158 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 1.001 (0.426-2.352) | 0.998 | 1.258 (0.465-3.403) | 0.652 | |

| Histological grade | 1.510 (0.821-2.778) | 0.185 | 1.576 (0.796-3.119) | 0.191 | |

| Radiotherapy | 0.578 (0.198-1.692) | 0.317 | 0.738 (0.209-2.605) | 0.637 | |

| CIK treatment | 0.520 (0.271-0.998) | 0.049* | 0.414 (0.190-0.903) | 0.027* | |

Toxic and side effects

Adverse reactions during the treatment in both groups of patients were observed. Both groups experienced common adverse reactions, including myelosuppression, fever, nausea and vomiting, liver dysfunction, kidney dysfunction, and the peripheral nerve toxicity. The main adverse reactions were I to II degrees. In the III-IV-degree myelosuppression group, 11 were in the CIK group and 12 in the control group; the side effects of the digestive tract were within the III degree; fever, renal impairment, and neurotoxicity were of I-II degrees. No intolerable adverse reactions were observed in both the groups, and no statistical difference was observed on comparing the adverse events between two groups (Table 4). There were no obvious adverse reactions observed during the injection of CIK cells. In the CIK group, 11 patients had a transient fever reaction (temperature < 38.5°C) that returned to normal condition within 24 h after symptomatic treatment. Moreover, during the course of CIK cell treatment, no patient quit midway due to intolerant side effects.

4.

Adverse events of the two groups

| Adverse events | CIK group

(n = 147) |

Control group

(n = 147) |

P |

| Bone marrow suppression | 0.222 | ||

| 0 | 98 | 84 | |

| I | 20 | 35 | |

| II | 18 | 16 | |

| III | 8 | 10 | |

| IV | 3 | 2 | |

| Fever | 0.491 | ||

| 0 | 118 | 112 | |

| I | 28 | 32 | |

| II | 1 | 3 | |

| III | 0 | 0 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 0.545 | ||

| 0 | 98 | 94 | |

| I | 18 | 13 | |

| II | 23 | 31 | |

| III | 8 | 9 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Liver dysfunction | 0.641 | ||

| 0 | 120 | 117 | |

| I | 17 | 21 | |

| II | 10 | 8 | |

| III | 0 | 1 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Kidney dysfunction | 0.415 | ||

| 0 | 137 | 134 | |

| I | 9 | 13 | |

| II | 1 | 0 | |

| III | 0 | 0 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

| Peripheral nerve toxicity | 0.542 | ||

| 0 | 132 | 126 | |

| I | 10 | 13 | |

| II | 5 | 8 | |

| III | 0 | 0 | |

| IV | 0 | 0 | |

Discussion

Compared to the non-triple-negative breast cancers, TNBC shows more biological aggression. It is also associated with poorer prognosis and shorter survival time1. On account of the stronger antigenicity owing to genomic instability and tumor mutation load, as well as higher expression of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs)22, and programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1)23 in TNBC make them a suitable target for immunotherapy, in contrast to the other subtypes of breast cancer. As the immunotherapy is non-organ-specific or non-tumor-specific, it is important to find the proper patient and treatment time, while combining it with existing treatment to achieve maximum efficacy. A breakthrough was achieved recently as immune checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 antibodies24, 25) became clinically effective. These previous significant studies have encouraged us to conduct the retrospective research on the effectiveness and safety of autologous CIK cell therapy coupled with chemotherapy in TNBC patients.

We found that CIK treatment combined with chemotherapy could effectively reduce the recurrence and metastasis in TNBC patients, thereby prolonging overall survival, and it had a stronger effect on patients at relatively early-stage of the disease. The conclusion that the patients in the early stages are the ones most benefited from CIK treatment was in line with some of the results from available studies on the treatment of other early-stage tumors by CIK immune cells26, 27. Several mechanisms could further contribute to the observed phenomenon. On one hand, the immune function of patients with late-stage cancer could be suppressed by the heavy tumor burden, which also influences the activity of infused CIK cells28. Immune system suppression related to tumor stages may hinder the initial expansion of CIK cells29. On the other hand, to evade the immune surveillance or immunotherapy, late-stage cells of metastatic cancer may evolve at molecular level30. Relevant information that could contribute to preventing recurrence and metastasis in early-stage TNBC patients using the new immunotherapy protocol is provided in the study.

Sequential CIK cell therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy resulted in dramatic lengthening of both DFS and OS intervals compared to those after chemotherapy alone, with a median DFS of 59 versus 55 months, and a median OS of 60 versus 59 months, respectively. The therapeutic model of cytotoxic chemotherapy combined with immunotherapy has been supported by some preclinical studies. These studies have shown that there is a synergy and complementation relationship between immunotherapy and chemotherapy31. The left-out tumor cells after chemotherapy and some chemotherapy-insensitive tumor cells can be removed by CIK cells32. Furthermore, it was demonstrated in previous studies that CIK cells could function as anti-cancer stem cells33. In this way, CIK cell therapy can reduce tumor recurrence and metastasis. Additionally, CIK cells secrete cytokines, such as IFN-γ, IL-2, and TNF-α, which can activate the anti-tumor properties of macrophages, reduce the immunological damage resulting from chemotherapeutic drugs, and facilitate the immune surveillance function of the body, to inhibit the growth of tumor cells34. Some chemotherapeutics, such as anthracycline can not only kill tumor cells directly, but also increase the sensitivity of tumor cells to immune effector cells35, thereby promoting their eradication by immune cells. With weakly immunogenic and immunosuppressive properties, immune escape is a typical biological feature of tumor cells36. Regulatory T (Treg) cells could limit the anti-tumor effect of immune cells by hindering CD3+CD4+ and CD3+CD8+ T lymphocytes from activation and proliferation, preventing NK cells proliferation, producing inhibitory cytokines, and eliminating effector cells, thereby promoting the immune escape of tumor cells, thus stimulating tumor progression37. CIK cells are capable of decreasing Treg cells ratio in peripheral blood of tumor patients, thereby increasing the proportion of CD3+CD4+T cells and the ratio of CD4+/CD8+T cells, thus the immunosuppressive status of tumor patients could be reduced or eliminated38. Therefore, chemotherapy can significantly lower the tumor burden, and then immune suppression can be alleviated or restored, hence sequential immunotherapy could achieve better therapeutic efficacy.

Additionally, besides the synergic effect with chemotherapy, immunotherapy also shows synergy with radiotherapy. Preclinical and clinical evidence suggests that RT may be a motivating factor to enhance the therapeutic benefits of immunotherapy for cancers39, 40.The potential effects of radiotherapy combined with immunotherapy are complex and multifactorial. Briefly, a combination of RT and immunotherapy induces the release of antigens during cancer cell death in association with proinflammatory signals that trigger the innate immune system to activate the tumor-specific T cells; thus, tumor targeted radiation therapy can be converted into an in-situ tumor vaccine41. To summarize, RT could improve the efficacy of immunotherapy and the immune system also functions in the action of radiotherapy.

No significant difference was found in the adverse reactions to chemotherapy plus CIK immunotherapy or chemotherapy alone, which indicates that the adverse effects of CIK immunotherapy are minor. The number of cycles for CIK treatment in this study depended on the patient’s disease progression, willingness to treat, and family economic status, ranging from 1 to 26 cycles, with the median of 6 treatment cycles. Survival analysis showed that the patients treated for more than 6 cycles with CIK cells had greater DFS and OS intervals than those treated with less than 6 cycles, demonstrating that the prognosis of patients was related to the frequency of CIK administration. However, the specific connection between the number of CIK treatment cycles and survival remains to be explored. Furthermore, the equilibrium of treatment efficacy and costs, and the exploration of the number of cycles to the greatest benefit of patients remains to be studied.

The study was novel for a number of reasons. First, the objects of the study were TNBC patients without distant metastasis, which forms a complementation with existing clinical studies of the patients at an advanced stage of breast cancer or metastatic breast cancer using CIK cells for treatment14-17. Therefore, this study enhanced our understanding of the potential of CIK cells in breast cancer treatment. Additionally, previous studies mostly concentrated on treatment using a single chemotherapy regimen42; in this study, the chemotherapy regimens were classified into anthracycline-based, anthracycline- and taxane-based, and taxane-based regimens, which provided a more comprehensive description of the efficacy of CIK cell therapy. However, this study also has some limitations. First, the precise assessment of CIK cell-induced treatment might be limited by the patient selection bias in the retrospective study. Second, the data collected in this study spanned from January 1, 2009 to January 1, 2015 and the follow-up period was up to May 1, 2018. The short follow-up time did not reflect the effect of CIK cell therapy on the long-term survival of patients with TNBC after surgery. A previous study revealed that CIK cells have a long half-life in vivo43, which could explain the long-lasting effects of CIK cells. Even if the disease progresses, the remaining active CIK cells can eliminate tumor cells and slow down the disease progression. Therefore, a prospective, multi-center, long-lasting follow-up assessment of CIK cell therapy for TNBC is required.

Conclusions

In summary, the strategy of CIK cell therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy could reduce recurrence and metastasis in postoperative TNBC patients, thereby prolong the overall survival time with minimum side effects. Therefore, CIK cell immunotherapy could be a potential new strategy for systemic adjuvant therapy after surgery for TNBC patients in the near future. Recently, the development of a gene expression profile facilitated re-classification of TNBC into six new subtypes, which showed varied sensitivities to different therapies. As precision medicine develops, precision therapy may be directed at various, potentially actionable molecular mutations in different subtypes of TNBC.

Conflict of interest statement

No potential conflicts of interest are disclosed.

Supplementary material

1.

Clinical characteristics of patients in the two groups

| Patient | Group | Age, years | TNM stage | Lymph node | Pathological grades | Radiotherapy | Recurrence | Survival |

| 1 | CIK group | 77 | IIb | Positive | III | No | Yes | Alive |

| 2 | CIK group | 52 | IIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 3 | CIK group | 38 | Unable to value | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 4 | CIK group | 60 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 5 | CIK group | 58 | I | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 6 | CIK group | 60 | Unable to value | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 7 | CIK group | 37 | IIb | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 8 | CIK group | 49 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 9 | CIK group | 51 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 10 | CIK group | 50 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 11 | CIK group | 60 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 12 | CIK group | 61 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 13 | CIK group | 76 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 14 | CIK group | 46 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 15 | CIK group | 54 | IIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 16 | CIK group | 64 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 17 | CIK group | 58 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 18 | CIK group | 44 | IIb | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 19 | CIK group | 50 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 20 | CIK group | 33 | IIb | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 21 | CIK group | 57 | IIIc | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 22 | CIK group | 52 | Unable to value | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 23 | CIK group | 56 | IIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 24 | CIK group | 38 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 25 | CIK group | 33 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 26 | CIK group | 51 | IIb | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 27 | CIK group | 58 | IIIc | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 28 | CIK group | 53 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | Yes | Alive |

| 29 | CIK group | 40 | IIa | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 30 | CIK group | 54 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 31 | CIK group | 56 | IIa | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 32 | CIK group | 51 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 33 | CIK group | 53 | IIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 34 | CIK group | 56 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 35 | CIK group | 59 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 36 | CIK group | 66 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 37 | CIK group | 56 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 38 | CIK group | 42 | IIb | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 39 | CIK group | 50 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 40 | CIK group | 49 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 41 | CIK group | 69 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 42 | CIK group | 47 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 43 | CIK group | 55 | I | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 44 | CIK group | 50 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 45 | CIK group | 59 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 46 | CIK group | 59 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 47 | CIK group | 50 | IIIc | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 48 | CIK group | 56 | Unable to value | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 49 | CIK group | 57 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 50 | CIK group | 60 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 51 | CIK group | 63 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 52 | CIK group | 62 | IIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 53 | CIK group | 60 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 54 | CIK group | 54 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 55 | CIK group | 48 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 56 | CIK group | 58 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 57 | CIK group | 31 | I | Negative | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 58 | CIK group | 56 | IIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 59 | CIK group | 60 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 60 | CIK group | 52 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 61 | CIK group | 42 | IIIc | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 62 | CIK group | 52 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 63 | CIK group | 53 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 64 | CIK group | 61 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 65 | CIK group | 48 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 66 | CIK group | 34 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 67 | CIK group | 71 | IIb | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 68 | CIK group | 48 | Unable to value | Negative | II | No | Yes | Alive |

| 69 | CIK group | 46 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 70 | CIK group | 37 | IIb | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 71 | CIK group | 45 | IIIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 72 | CIK group | 61 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 73 | CIK group | 45 | IIIc | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 74 | CIK group | 56 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 75 | CIK group | 59 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 76 | CIK group | 46 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 77 | CIK group | 41 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 78 | CIK group | 46 | IIb | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 79 | CIK group | 49 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 80 | CIK group | 54 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 81 | CIK group | 61 | IIb | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 82 | CIK group | 49 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 83 | CIK group | 55 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 84 | CIK group | 50 | IIa | Negative | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 85 | CIK group | 46 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 86 | CIK group | 57 | IIIb | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 87 | CIK group | 33 | IIb | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 88 | CIK group | 61 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 89 | CIK group | 52 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 90 | CIK group | 47 | IIa | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 91 | CIK group | 58 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 92 | CIK group | 45 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 93 | CIK group | 53 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 94 | CIK group | 32 | IIa | Negative | III | Yes | Yes | Alive |

| 95 | CIK group | 38 | IIa | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 96 | CIK group | 31 | Unable to value | Negative | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 97 | CIK group | 50 | IIb | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 98 | CIK group | 44 | IIb | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 99 | CIK group | 62 | IIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 100 | CIK group | 54 | I | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 101 | CIK group | 50 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 102 | CIK group | 68 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 103 | CIK group | 26 | Unable to value | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 104 | CIK group | 60 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 105 | CIK group | 35 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 106 | CIK group | 36 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 107 | CIK group | 52 | IIb | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 108 | CIK group | 60 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 109 | CIK group | 43 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 110 | CIK group | 57 | IIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 111 | CIK group | 73 | IIIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 112 | CIK group | 72 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 113 | CIK group | 47 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 114 | CIK group | 49 | IIa | Negative | III | No | Yes | Alive |

| 115 | CIK group | 40 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 116 | CIK group | 52 | IIb | Positive | III | No | Yes | Alive |

| 117 | CIK group | 38 | IIb | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 118 | CIK group | 53 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 119 | CIK group | 50 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 120 | CIK group | 57 | I | Negative | II | No | Yes | Alive |

| 121 | CIK group | 54 | IIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 122 | CIK group | 50 | IIb | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 123 | CIK group | 64 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 124 | CIK group | 61 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 125 | CIK group | 49 | I | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 126 | CIK group | 59 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 127 | CIK group | 68 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 128 | CIK group | 59 | IIb | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 129 | CIK group | 59 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 130 | CIK group | 48 | IIa | Negative | II | No | Yes | Alive |

| 131 | CIK group | 53 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 132 | CIK group | 60 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 133 | CIK group | 45 | IIIc | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 134 | CIK group | 60 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 135 | CIK group | 69 | IIIc | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 136 | CIK group | 45 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 137 | CIK group | 39 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 138 | CIK group | 42 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 139 | CIK group | 44 | I | Negative | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 140 | CIK group | 44 | I | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 141 | CIK group | 32 | IIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 142 | CIK group | 55 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 143 | CIK group | 43 | IIa | Negative | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 144 | CIK group | 40 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 145 | CIK group | 64 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 146 | CIK group | 69 | IIIc | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 147 | CIK group | 44 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 148 | Control group | 78 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 149 | Control group | 76 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 150 | Control group | 73 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 151 | Control group | 72 | IIb | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 152 | Control group | 71 | IIIc | Positive | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 153 | Control group | 69 | IIb | Positive | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 154 | Control group | 69 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 155 | Control group | 69 | IIIb | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 156 | Control group | 68 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 157 | Control group | 68 | I | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 158 | Control group | 66 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 159 | Control group | 64 | I | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 160 | Control group | 64 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 161 | Control group | 64 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 162 | Control group | 63 | Unable to value | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 163 | Control group | 62 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 164 | Control group | 62 | IIa | Negative | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 165 | Control group | 61 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 166 | Control group | 61 | IIa | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 167 | Control group | 61 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 168 | Control group | 61 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 169 | Control group | 61 | IIa | Negative | I | No | No | Alive |

| 170 | Control group | 61 | IIb | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 171 | Control group | 61 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 172 | Control group | 60 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 173 | Control group | 60 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 174 | Control group | 60 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 175 | Control group | 60 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 176 | Control group | 60 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 177 | Control group | 60 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 178 | Control group | 60 | IIIc | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 179 | Control group | 60 | IIIc | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 180 | Control group | 60 | Unable to value | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 181 | Control group | 59 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 182 | Control group | 59 | IIb | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 183 | Control group | 59 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 184 | Control group | 59 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 185 | Control group | 59 | IIa | Positive | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 186 | Control group | 59 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 187 | Control group | 59 | IIa | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 188 | Control group | 58 | IIb | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 189 | Control group | 58 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 190 | Control group | 58 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 191 | Control group | 58 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 192 | Control group | 58 | IIa | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 193 | Control group | 56 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 194 | Control group | 57 | I | Negative | II | No | Yes | Alive |

| 195 | Control group | 57 | IIIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 196 | Control group | 57 | I | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 197 | Control group | 57 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 198 | Control group | 56 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 199 | Control group | 56 | IIIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 200 | Control group | 56 | IIIb | Negative | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 201 | Control group | 56 | I | Negative | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 202 | Control group | 56 | IIa | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 203 | Control group | 56 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 204 | Control group | 56 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 205 | Control group | 55 | IIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 206 | Control group | 55 | IIa | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 207 | Control group | 55 | I | Negative | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 208 | Control group | 54 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 209 | Control group | 54 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 210 | Control group | 54 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 211 | Control group | 54 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 212 | Control group | 54 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 213 | Control group | 54 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 214 | Control group | 53 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 215 | Control group | 53 | IIa | Negative | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 216 | Control group | 53 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 217 | Control group | 53 | IIa | Positive | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 218 | Control group | 53 | I | Negative | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 219 | Control group | 53 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 220 | Control group | 52 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 221 | Control group | 52 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 222 | Control group | 52 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 223 | Control group | 52 | I | Negative | II | Yes | Yes | Alive |

| 224 | Control group | 52 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 225 | Control group | 52 | I | Negative | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 226 | Control group | 52 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 227 | Control group | 51 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 228 | Control group | 51 | IIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 229 | Control group | 51 | I | Negative | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 230 | Control group | 50 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 231 | Control group | 50 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 232 | Control group | 50 | IIa | Negative | II | No | Yes | Alive |

| 233 | Control group | 50 | IIIc | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 234 | Control group | 50 | IIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 235 | Control group | 50 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 236 | Control group | 50 | IIIc | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 237 | Control group | 50 | Unable to value | Negative | I | No | No | Alive |

| 238 | Control group | 50 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 239 | Control group | 50 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 240 | Control group | 49 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 241 | Control group | 49 | IIIc | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 242 | Control group | 49 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 243 | Control group | 49 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 244 | Control group | 49 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 245 | Control group | 49 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 246 | Control group | 48 | IIIa | Positive | II | Yes | Yes | Alive |

| 247 | Control group | 48 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 248 | Control group | 48 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 249 | Control group | 48 | IIb | Positive | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 250 | Control group | 47 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 251 | Control group | 47 | IIa | Positive | II | Yes | No | Alive |

| 252 | Control group | 47 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 253 | Control group | 46 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 254 | Control group | 46 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 255 | Control group | 46 | IIIc | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 256 | Control group | 46 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 257 | Control group | 46 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 258 | Control group | 45 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 259 | Control group | 45 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 260 | Control group | 45 | IIIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 261 | Control group | 45 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 262 | Control group | 45 | IIIa | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 263 | Control group | 44 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 264 | Control group | 44 | IIa | Negative | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 265 | Control group | 44 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 266 | Control group | 44 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 267 | Control group | 44 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 268 | Control group | 43 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 269 | Control group | 43 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 270 | Control group | 42 | IIIa | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 271 | Control group | 42 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 272 | Control group | 42 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 273 | Control group | 41 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 274 | Control group | 40 | IIa | Negative | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 275 | Control group | 40 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 276 | Control group | 40 | Unable to value | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 277 | Control group | 39 | IIa | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 278 | Control group | 38 | IIb | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 279 | Control group | 38 | Unable to value | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 280 | Control group | 38 | IIIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 281 | Control group | 38 | IIa | Positive | III | No | Yes | Death |

| 282 | Control group | 37 | IIIa | Positive | II | No | Yes | Death |

| 283 | Control group | 37 | IIIc | Positive | III | No | No | Alive |

| 284 | Control group | 36 | IIb | Positive | III | Yes | Yes | Death |

| 285 | Control group | 35 | IIIa | Positive | II | No | Yes | Alive |

| 286 | Control group | 34 | IIb | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 287 | Control group | 33 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 288 | Control group | 33 | IIa | Positive | II | No | No | Alive |

| 289 | Control group | 33 | IIIc | Positive | III | Yes | No | Alive |

| 290 | Control group | 32 | I | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 291 | Control group | 32 | Unable to value | Negative | II | No | No | Alive |

| 292 | Control group | 31 | I | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 293 | Control group | 31 | IIa | Negative | III | No | No | Alive |

| 294 | Control group | 26 | IIa | Negative | III | No | Yes | Death |

References

- 1.Dent R, Trudeau M, Pritchard KI, Hanna WM, Kahn HK, Sawka CA, et al Triple-negative breast cancer: clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:4429–34. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-3045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwentner L, Wolters R, Koretz K, Wischnewsky MB, Kreienberg R, Rottscholl R, et al Triple-negative breast cancer: the impact of guideline-adherent adjuvant treatment on survival--a retrospective multi-centre cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:1073–80. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1935-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haffty BG, Yang QF, Reiss M, Kearney T, Higgins SA, Weidhaas J, et al Locoregional relapse and distant metastasis in conservatively managed triple negative early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5652–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lehmann BD, Bauer JA, Chen X, Sanders ME, Chakravarthy AB, Shyr Y, et al Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2750–67. doi: 10.1172/JCI45014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stagg J, Allard B Immunotherapeutic approaches in triple-negative breast cancer: latest research and clinical prospects. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2013;5:169–81. doi: 10.1177/1758834012475152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmidt-Wolf IG, Negrin RS, Kiem HP, Blume KG, Weissman IL Use of a scid mouse/human lymphoma model to evaluate cytokine-induced killer cells with potent antitumor cell activity. J Exp Med. 1991;174:139–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.1.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verneris MR, Kornacker M, Mailänder V, Negrin RS Resistance of ex vivo expanded CD3+CD56+ T cells to fas-mediated apoptosis . Cancer Immunol, Immun. 2000;49:335–45. doi: 10.1007/s002620000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hontscha C, Borck Y, Zhou H, Messmer D, Schmidt-Wolf IGH Clinical trials on CIK cells: first report of the international registry on CIK cells (IRCC) J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:305–10. doi: 10.1007/s00432-010-0887-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu L, Zhang WH, Qi XY, Li H, Yu JP, Wei S, et al Randomized study of autologous cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in metastatic renal carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1751–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi LR, Zhou Q, Wu J, Ji M, Li GJ, Jiang JT, et al Efficacy of adjuvant immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells in patients with locally advanced gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2012;61:2251–9. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1289-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang LL, Ren BZ, Li H, Yu JP, Cao S, Hao XS, et al Enhanced antitumor effects of DC-activated CIKs to chemotherapy treatment in a single cohort of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol, Immun. 2013;62:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1311-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao H, Wang Y, Yu JP, Wei F, Cao S, Zhang XW, et al Autologous cytokine-induced killer cells improves overall survival of metastatic colorectal cancer patients: results from a phase II clinical trial. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15:228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2016.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Wang YM, Kellner DB, Zhao LD, Xu LP, Gao QL Efficacy of retronectin-activated cytokine-induced killer cell therapy in the treatment of advanced hepatocelluar carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2016;12:707–14. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin M, Liang SZ, Jiang F, Xu JY, Zhu WB, Qian W, et al 2003-2013, a valuable study: autologous tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cell immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells improves survival in stage IV breast cancer. Immunol Lett. 2017;183:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2017.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ren J, Di LJ, Song GH, Yu J, Jia J, Zhu YL, et al Selections of appropriate regimen of high-dose chemotherapy combined with adoptive cellular therapy with dendritic and cytokine-induced killer cells improved progression-free and overall survival in patients with metastatic breast cancer: reargument of such contentious therapeutic preferences. Clin Trans Oncol. 2013;15:780–8. doi: 10.1007/s12094-013-1001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Ren J, Zhang J, Yan Y, Jiang N, Yu J, et al Prospective study of cyclophosphamide, thiotepa, carboplatin combined with adoptive DC-CIK followed by metronomic cyclophosphamide therapy as salvage treatment for triple negative metastatic breast cancers patients (aged <45) Clin Trans Oncol. 2016;18:82–7. doi: 10.1007/s12094-015-1339-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mao QX, Li LF, Zhang CJ, Sun YD, Liu SQ, Cui SD Clinical effects of immunotherapy of DC-CIK combined with chemotherapy in treating patients with metastatic breast cancer. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2015;28:1055–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu XZ, Zhao H, Liu L, Cao S, Ren BZ, Zhang NN, et al A randomized phase II study of autologous cytokine-induced killer cells in treatment of hepatocelluar carcinoma. J Clin Immunol. 2014;34:194–203. doi: 10.1007/s10875-013-9976-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhao H, Fan YL, Li H, Yu JP, Liu L, Cao S, et al Immunotherapy with cytokine-induced killer cells as an adjuvant treatment for advanced gastric carcinoma: a retrospective study of 165 patients. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2013;28:303–9. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2012.1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li RM, Wang CL, Liu L, Du CJ, Cao S, Yu JP, et al Autologous cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in lung cancer: a phase II clinical study. Cancer Immunol, Immun. 2012;61:2125–33. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1260-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised recist guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loi S, Sirtaine N, Piette F, Salgado R, Viale G, Van Eenoo F, et al Prognostic and predictive value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in a phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trial in node-positive breast cancer comparing the addition of docetaxel to doxorubicin with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy: BIG 02-98. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:860–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali HR, Glont SE, Blows FM, Provenzano E, Dawson SJ, Liu B, et al PD-L1 protein expression in breast cancer is rare, enriched in basal-like tumours and associated with infiltrating lymphocytes. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1488–93. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pusztai L, Karn T, Safonov A, Abu-Khalaf MM, Bianchini G New strategies in breast cancer: immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2105–10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li M, Li AQ, Zhou SL, Xu Y, Xiao YX, Bi R, et al Heterogeneity of PD-L1 expression in primary tumors and paired lymph node metastases of triple negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18:4. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3916-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li H, Huang L, Liu LB, Wang XM, Zhang Z, Yue DL, et al Selective effect of cytokine-induced killer cells on survival of patients with early-stage melanoma. Cancer Immunol, Immun. 2017;66:299–308. doi: 10.1007/s00262-016-1939-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li DP, Li W, Feng J, Chen K, Tao M Adjuvant chemotherapy with sequential cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells in stage IB non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Res. 2015;22:67–74. doi: 10.3727/096504014X14024160459168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fichtner S, Hose D, Engelhardt M, Meißner T, Neuber B, Krasniqi F, et al Association of antigen-specific T-cell responses with antigen expression and immunoparalysis in multiple myeloma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:1712–21. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joseph RW, Peddareddigari VR, Liu P, Miller PW, Overwijk WW, Bekele NB, et al Impact of clinical and pathologic features on tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte expansion from surgically excised melanoma metastases for adoptive T-cell therapy. Clin Cancer. 2011;17:4882–91. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Volonté A, Di Tomaso T, Spinelli M, Todaro M, Sanvito F, Albarello L, et al Cancer-initiating cells from colorectal cancer patients escape from T cell-mediated immunosurveillance in vitro through membrane-bound IL-4. J Immunol. 2014;192:523–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lake RA, Robinson BWS Immunotherapy and chemotherapy–a practical partnership. Nat Rev. Cancer. 2005;5:397–405. doi: 10.1038/nrc1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang YS, Yuan FJ, Jia GF, Zhang JF, Hu LY, Huang L, et al Cik cells from patients with HCC possess strong cytotoxicity to multidrug-resistant cell line bel-7402/R. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3339–45. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gammaitoni L, Giraudo L, Leuci V, Todorovic M, Mesiano G, Picciotto F, et al Effective activity of cytokine-induced killer cells against autologous metastatic melanoma including cells with stemness features. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:4347–58. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-0061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schmidt-Wolf IG, Lefterova P, Mehta BA, Fernandez LP, Huhn D, Blume KG, et al Phenotypic characterization and identification of effector cells involved in tumor cell recognition of cytokine-induced killer cells. Exp Hematol. 1993;21:1673–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramakrishnan R, Assudani D, Nagaraj S, Hunter T, Cho HI, Antonia S, et al Chemotherapy enhances tumor cell susceptibility to ctl-mediated killing during cancer immunotherapy in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1111–24. doi: 10.1172/JCI40269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andersen MH, Sørensen RB, Brimnes MK, Svane IM, Becker JC, thor Straten P Identification of heme oxygenase-1-specific regulatory CD8+ T cells in cancer patients . J Clin Invest. 2009;119:2245–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI38739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao X, Ji CY, Liu GQ, Ma DX, Ding HF, Xu M, et al Immunomodulatory effect of DC/CIK combined with chemotherapy in multiple myeloma and the clinical efficacy. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:13146–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Twyman-Saint Victor C, Rech AJ, Maity A, Rengan R, Pauken KE, Stelekati E, et al Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature. 2015;520:373–7. doi: 10.1038/nature14292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Huguenin PU, Kieser S, Glanzmann C, Capaul R, Lütolf UM Radiotherapy for metastatic carcinomas of the kidney or melanomas: an analysis using palliative end points. Int J Radiat Oncol, Biol, Phys. 1998;41:401–5. doi: 10.1016/S0360-3016(98)00021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Demaria S, Golden EB, Formenti SC Role of local radiation therapy in cancer immunotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:1325–32. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.2756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hu J, Hu J, Liu X, Hu C, Li M, Han W Effect and safety of cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cell immunotherapy in patients with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Medicine. 2017;96:e8310. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mesiano G, Todorovic M, Gammaitoni L, Leuci V, Giraudo Diego L, Carnevale-Schianca F, et al Cytokine-induced killer (CIK) cells as feasible and effective adoptive immunotherapy for the treatment of solid tumors. Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12:673–84. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.675323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]