Abstract

Background

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is an important cause of ill health in women of reproductive age, causing them physical problems, social disruption and reducing their quality of life. Medical therapy has traditionally been first‐line therapy. Surgical treatment of HMB often follows failed or ineffective medical therapy. The definitive treatment is hysterectomy, but this is a major surgical procedure with significant physical and emotional complications, as well as social and economic costs. Less invasive surgical techniques, such as endometrial resection and ablation, have been developed with the purpose of improving menstrual symptoms by removing or ablating the entire thickness of the endometrium.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness, acceptability and safety of techniques of endometrial destruction by any means versus hysterectomy by any means for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Search methods

Electronic searches for relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) targeted—but were not limited to—the following: the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group's specialised register, CENTRAL via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO), MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, and the ongoing trial registries. We made attempts to identify trials by examining citation lists of review articles and guidelines and by performing handsearching. Searches were performed in 1999, 2007, 2008, 2013 and on 10 December 2018.

Selection criteria

Any RCTs that compared techniques of endometrial resection or ablation (by any means) with hysterectomy (by any technique) for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding in premenopausal women.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected trials for inclusion, extracted data and assessed trials for risk of bias.

Main results

We identified nine RCTs that fulfilled our inclusion criteria for this review. For two trials, the review authors identified multiple publications that assessed different outcomes at different postoperative time points for the same women. No included trials used third generation techniques.

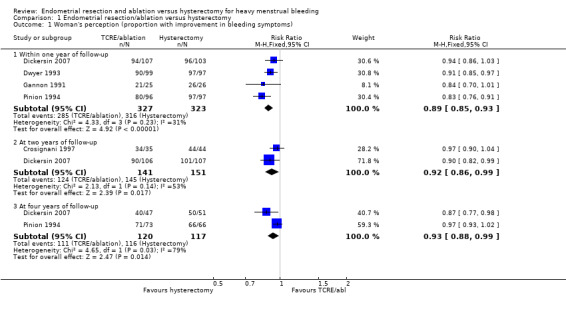

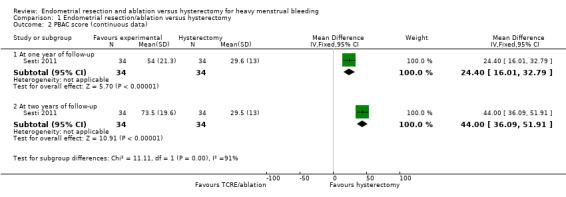

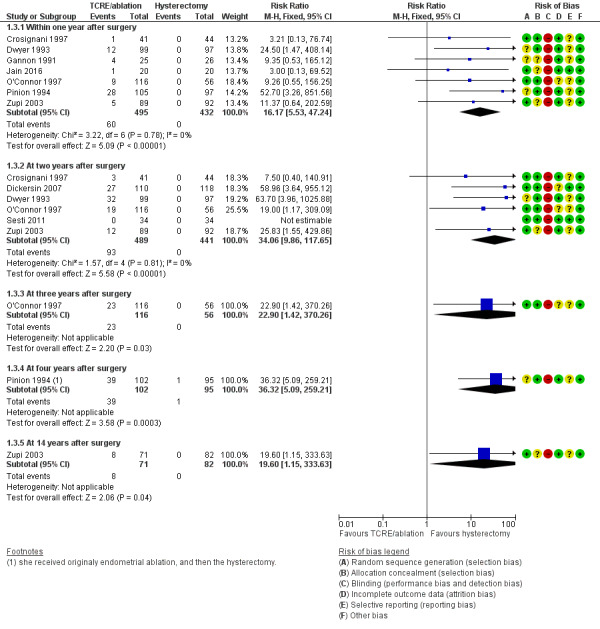

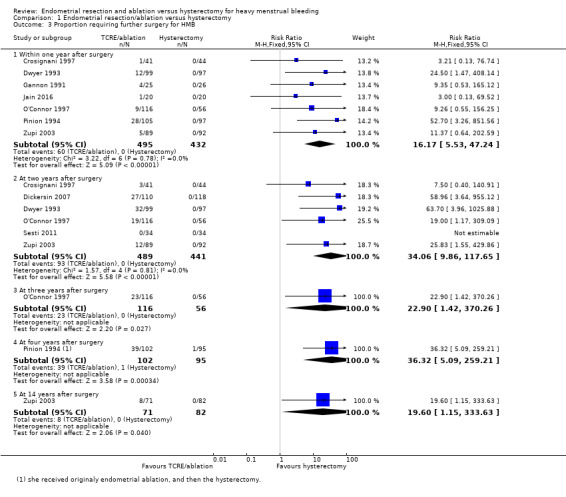

Clinical measures of improved bleeding symptoms and satisfaction rates were observed in women who had undergone hysterectomy compared to endometrial ablation. A slightly lower proportion of women who underwent endometrial ablation perceived improvement in bleeding symptoms at one year (risk ratio (RR) 0.89, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 0.93; 4 studies, 650 women, I² = 31%; low‐quality evidence), at two years (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.99; 2 studies, 292 women, I² = 53%) and at four years (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99; 2 studies, 237 women, I² = 79%). Women in the endometrial ablation group also showed improvement in pictorial blood loss assessment chart compared to their baseline (PBAC) score at one year (MD 24.40, 95% CI 16.01 to 32.79; 1 study, 68 women; moderate‐quality evidence) and at two years (MD 44.00, 95% CI 36.09 to 51.91; 1 study, 68 women). Repeat surgery resulting from failure of the initial treatment was more likely to be needed after endometrial ablation than after hysterectomy at one year (RR 16.17, 95% CI 5.53 to 47.24; 927 women; 7 studies; I2 = 0%), at two years (RR 34.06, 95% CI 9.86 to 117.65; 930 women; 6 studies; I2 = 0%), at three years (RR 22.90, 95% CI 1.42 to 370.26; 172 women; 1 study) and at four years (RR 36.32, 95% CI 5.09 to 259.21;197 women; 1 study). The satisfaction rate was lower amongst those who had endometrial ablation at two years after surgery (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.95; 4 studies, 567 women, I² = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence), and no evidence of clear difference was reported between post‐treatment satisfaction rates in groups at other follow‐up times (1 and 4 years).

Most adverse events, both major and minor, were more likely after hysterectomy during hospital stay. Women who had an endometrial ablation were less likely to experience sepsis (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.31; participants = 621; studies = 4; I2 = 62%), blood transfusion (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.59; 791 women; 5 studies; I2 = 0%), pyrexia (RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.35; 605 women; 3 studies; I2 = 66%), vault haematoma (RR 0.11, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.34; 858 women; 5 studies; I2 = 0%) and wound haematoma (RR 0.03, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.53; 202 women; 1 study) before hospital discharge. After discharge from hospital, the only difference that was reported for this group was a higher rate of infection (RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.58; 172 women; 1 study).

Recovery time was shorter in the endometrial ablation group, considering hospital stay, time to return to normal activities and time to return to work; we did not, however, pool these data owing to high heterogeneity. Some outcomes (such as a woman’s perception of bleeding and proportion of women requiring further surgery for HMB), generated a low GRADE score, suggesting that further research in these areas is likely to change the estimates.

Authors' conclusions

Endometrial resection and ablation offers an alternative to hysterectomy as a surgical treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding. Both procedures are effective, and satisfaction rates are high. Although hysterectomy offers permanent and immediate relief from heavy menstrual bleeding, it is associated with a longer operating time and recovery period. Hysterectomy also has higher rates of postoperative complications such as sepsis, blood transfusion and haematoma (vault and wound). The initial cost of endometrial destruction is lower than that of hysterectomy but, because retreatment is often necessary, the cost difference narrows over time.

Plain language summary

A comparison of the effectiveness and safety of two different surgical treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding

Review question

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is menstrual blood loss that interferes with women's quality of life. Cochrane researchers compared two surgical treatments for women with HMB. The main factors (thought to be of greatest importance) were how well each operation was able to treat the symptoms of HMB, how women felt about undergoing each operation and what the complication rates were. Additional factors studied were how long each operation took to perform, how long women took to recover from the operation and how much the operation cost the hospital and the woman herself.

Background

Surgical treatments for HMB include removal or destruction of the inside lining (endometrium) of the womb (endometrial resection or ablation) and surgical removal of the whole womb (hysterectomy). Both methods are commonly offered by gynaecologists, usually after a non‐surgical treatment has failed to correct the problem. Endometrial resection/ablation is performed via the entrance to the womb, without the need for a surgical cut. During a hysterectomy, the uterus can be removed via a surgical cut to the abdomen, via the vagina, or via 'keyhole' surgery that involves very small surgical cuts to the abdomen (laparoscopy). Hysterectomy is effective in permanently stopping HMB, but it halts fertility and is associated with all the risks of major surgery, including infection and blood loss. These risks are smaller with endometrial resection/ablation.

Search date

A systematic review of the research comparing endometrial resection and ablation versus hysterectomy for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding was most recently updated in December 2018 by Cochrane researchers. After searching for all relevant studies, review authors included nine studies involving a total of 1300 women.

Study characteristics

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are included: these are studies in which participants are randomly allocated to one of two groups, each receiving a different intervention. The two groups are then compared. This review included RCTs that compared endometrial ablation or resection and hysterectomy as treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding. The studies did not include women who had gone through menopause or had cancer (or precancer) of the uterus.

Key results and conclusions

The review of studies revealed that endometrial ablation/resection is an effective and possibly cheaper alternative to hysterectomy, with faster recovery, although retreatment with additional surgery is sometimes needed. Hysterectomy is associated with more definitive resolution of symptoms but there are longer operating times and greater potential for surgical complications. For both operations, women generally reported that undergoing the procedure was acceptable and that they were satisfied with their experience.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy has become more widely used and some outcomes such as duration of hospital stay, time to return to work and time to return to normal activities have become more comparable with those of endometrial ablation. However, laparoscopic hysterectomy is frequently associated with longer operating time than other modes of hysterectomy and requires specific surgical expertise and equipment.

Identifying harms

Both surgical treatments are considered to be generally safe, with low complication rates. Hysterectomy, however, is associated with higher rates of infection, requirement for blood transfusion, and haematoma (collection of blood in soft tissues after surgery).

Quality of the evidence

Evidence reported in this review was of moderate to low quality, suggesting that further research may change the result. This was the case for outcomes such as a woman’s perception of bleeding and proportion of women requiring further surgery for HMB.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Endometrial resection or ablation compared to hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding.

| Endometrial resection‐ablation compared to hysterectomy for heavy menstrual bleeding. | ||||||

| Patient or population: heavy menstrual bleeding Setting: Intervention: endometrial resection/ablation Comparison: hysterectomy | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with hysterectomy | Risk with endometrial resection/ablation | |||||

| Woman's perception (proportion with improvement in bleeding symptoms) ‐ within 1 year of follow‐up | 978 per 1000 | 871 per 1000 (832 to 910) | RR 0.89 (0.85 to 0.93) | 650 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| PBAC score (continuous data) ‐ at 1 year of follow‐up | The mean PBAC score (continuous data) was 29.6 | The mean PBAC score (continuous data) was 54 24.4 higher than the hysterectomy group (16.01 higher to 32.79 higher) |

‐ | 68 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Proportion requiring further surgery for HMB ‐ within 1 year after surgery | 0 per 1000 | 121 per 1000** | RR 16.17 (5.53 to 47.24) | 927 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 3 | |

| Proportion satisfied with treatment ‐ at 1 year of follow‐up | 820 per 1000 | 771 per 1000 (721 to 820) | RR 0.94 (0.88 to 1.00) | 739 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ MODERATE 1 | |

| Adverse events—short term (intraoperative and immediate postoperative) ‐ Sepsis | 319 per 1000 | 61 per 1000 (38 to 99) | RR 0.19 (0.12 to 0.31) | 621 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 2 | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% CI) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

** We are unable to anticipate the absolute risk of further surgery with Endometrial resection or ablation as the number of further surgery, at 1 year follow up, in the hysterectomy group was 0. This number represents the risk in the endometrial resection group from trial data. CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 Downgraded 1 level for risk of bias; lack of blinding (although unfeasible) is likely to bias women's responses

2 Downgraded 1 level for inconsistency; considerable heterogeneity

3 Downgraded 1 level for imprecision; wide confidence interval

Background

Description of the condition

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) is excessive blood loss that interferes with women's quality of life, either physical, psychological, material or social (Munro 2011; NICE 2018). Many other terms are used as HMB synonyms, including menorrhagia, abnormal menstrual bleeding, abnormal uterine bleeding and disordered uterine bleeding. These terms have not always been universally defined, and considerable overlap and confusion between them have been noted in the existing literature (Woolcock 2008). In response to this confusion, the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) formally defined HMB as "the woman's perspective of increased menstrual volume, regardless of regularity, frequency, or duration" (Munro 2011).

HMB is a common presenting complaint for primary care services and a frequent reason for secondary referral, with 5% of women between 30 and 49 years of age seeking medical attention for the problem (Vessey 1992; Cooper 2011).

Personal perception is often what determines the need for treatment and assessment of outcomes afterwards.

Intervention for HMB should be aimed at correction of identified underlying causes, control of bleeding, amelioration of anaemia and improvement in quality of life measures, with the woman’s contraceptive requirements or desire for future fertility taken into account, along with individual preferences for treatment.

Description of the intervention

Many well‐established treatment options for HMB are available, including hormonal and non‐hormonal medications, but among women who do not desire future fertility or for whom medical treatment may be problematic, inconvenient or prolonged, surgical management may be preferred.

Until the mid‐1980s, hysterectomy was the only option for such women, and 60% of women presenting with HMB during this time underwent hysterectomy as a first‐line treatment (NICE 2007). Hysterectomy continues to be performed via the more traditional abdominal and vaginal routes, but minimally invasive techniques have been introduced for women with benign disease, and these techniques continue to be developed. Such approaches include the introduction of laparoscopic hysterectomy (total laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy) in 1989 (Reich 1989); and single‐port laparoscopic hysterectomy in 2009 (Li 2012).

Considerable differences between types of approach have been noted with regard to intraoperative complications, duration of hospital stay, length of recovery and cost. However, as this review aims to compare hysterectomy with endometrial resection and ablation, we have pooled the results for hysterectomy by all approaches.

Endometrial ablation is a minimally invasive hysteroscopic surgical intervention for HMB involving removal or destruction of the endometrium. Since it was introduced in the 1990s, its popularity as an alternative to hysterectomy has grown (Fernandez 2011). An examination of the UK National Health Service (NHS) statistics in 2005 revealed that endometrial destruction was being performed more frequently than hysterectomy for benign HMB in the UK (Reid 2007). In a long‐term study with up to 25 years' follow‐up in the UK, only 25% of the woman with an endometrial resection or ablation underwent a subsequent hysterectomy; and 75% of the surgeries were in the first five years of follow‐up (Kalampolas 2017), suggesting endometrial ablation may have a role in limiting the number of hysterectomies performed. This, however, may also reflect progression through menopause for many of these women.

Endometrial resection and ablation techniques are classically divided, according to the requirement of hysteroscopy to perform the ablation, in first‐ and second‐generation techniques. First‐generation techniques require direct hysteroscopic vision throughout the procedure and include desiccation of the endometrium by way of rollerball endometrial ablation (REA) and transcervical resection of the endometrium with loop electrode. This can be useful to identify and remove other endometrial pathology such as polyps and fibroids. A potential complication of endometrial resection is systemic fluid overload due to absorption of hysteroscopic fluid; therefore careful intraoperative input/output fluid balance requires attention and documentation. The efficacy and safety of first‐generation techniques are often operator dependent.

Newer technologies were subsequently introduced; second‐ and third‐generation techniques are non‐hysteroscopic, are considered easier to perform, equally effective and safe (Madhu 2009), reporting lower complication rates of around 1% for bipolar ablation (Athanatos 2015; Laberge 2016). All of these techniques, with the exception of hydrothermal ablation and endometrial laser intrauterine thermal therapy, involve performing surgery with a hysteroscope, i.e. without direct visualisation. The second‐generation techniques have allowed widespread use of endometrial ablation, as they require less advanced hysteroscopic skill and do not necessitate intraoperative fluid balance. However, these procedures depend heavily on the surgical equipment itself for efficacy and safety. The difference between the second and third generation is that third‐generation techniques have replaced latex with silicone in the balloon and have active fluid circulation, which enables the total endometrial surface to receive equal heat distribution (Kumar 2016).

How the intervention might work

Hysterectomy is regarded as ‘definitive’ treatment for HMB with guaranteed amenorrhoea and cessation of fertility and little need for future treatment. However, hysterectomy by any route is associated with all the complications of major surgery, including intraoperative bleeding, infection and venous thromboembolism. Other reported complications include urinary incontinence and dyspareunia. Urinary tract injuries are an unusual hysterectomy complication, having an overall incidence in laparoscopic hysterectomy of 0.73% (bladder 0.05% to 0.66%, ureter 0.02% to 0.4%) (Adelman 2014).

Endometrial ablation is a less invasive surgical option for women with HMB, although a successful outcome after endometrial ablation is not guaranteed and further surgery is occasionally required (Nagele 1998; Bourdrez 2004). Endometrial resection/ablation is often chosen because of perceived short hospitalisation, quick return to normal functioning and avoidance of major surgery (Nagele 1998). Vaginal discharge and increased period pain are common complications following endometrial resection/ablation. Uncommon complications include intraoperative uterine perforation and associated pelvic organ injury from direct perforation or electrosurgical burns. Pregnancies occurring after endometrial ablation have been reported to be at higher risk of ectopic pregnancy, preterm birth and abnormality of placentation (Sharp 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

HMB is a common reason for women to seek treatment, and many choose a surgical option as first‐ or second‐line management. Surgical methods for treatment of HMB show a trend in favour of endometrial resection/ablation and towards newer endometrial resection/ablation techniques. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, 60% of women with HMB who were referred to a gynaecologist in the UK were treated with hysterectomy (Coulter 1991), but an examination of NHS statistics in 2005 revealed that endometrial destruction was being performed more frequently than hysterectomy for benign HMB in the UK (Reid 2007).

Despite this trend, many women still express a preference for first‐line hysterectomy (Kennedy 2002), and rates of different methods of hysterectomy are evolving.

As surgical techniques for both hysterectomy and endometrial resection/ablation continue to evolve, corresponding changes in success rates, outcomes and complications will be noted, necessitating regular comparison and review.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness, acceptability and safety of techniques of endometrial destruction by any means versus hysterectomy by any means for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Published and non‐published randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion. We excluded quasi‐randomised trials.

Types of participants

Source of recruitment

Primary care, family planning and specialist clinics.

Inclusion criterion

Women of reproductive years with heavy menstrual bleeding (including both heavy regular periods (menorrhagia) and heavy irregular periods (metrorrhagia)), measured objectively or subjectively.

Exclusion criteria

Postmenopausal bleeding (> 1 year from the last period).

HMB caused by uterine malignancy or endometrial hyperplasia.

Iatrogenic causes of HMB (e.g. intrauterine coil devices).

Types of interventions

Endometrial resection and ablation (including first‐generation techniques, such as transcervical resection of the endometrium with loop electrode or rollerball; second‐generation techniques, such as endometrial ablation by thermal balloon, microwave, thermal free‐fluid, radiofrequency and cryotherapy); and third‐generation endometrial ablation techniques that are similar to the second‐generation techniques but have replaced latex with silicone in the balloon and have active fluid circulation.

Hysterectomy (by abdominal, vaginal and laparoscopic/laparoscopically assisted routes).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Effectiveness (improvement in bleeding)

Woman's perception (proportion with improvement in bleeding symptoms).

PBAC (Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart) score: a visual measure of amount of blood loss (clinically significant HMB correlates with a score > 100).*

Requirement for further surgery.

Acceptability

Proportion satisfied with treatment.

Safety (adverse outcomes)

Adverse events: short term (intraoperative and immediately postoperative).

Adverse events: long term (after hospital discharge).

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life scores (continuous data).

Quality of life (proportion with improvement).

Duration of surgery.

Duration of hospital stay.

Time to return to normal activity.

Time to return to work.

Total health service cost per woman.

Total individual cost per woman.

*PBAC score: a score over 100 suggests significantly heavy menstrual bleeding. A reduction from over 100 to under 100 would be clinically significant at an individual level.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched all publications that would potentially describe RCTs comparing surgical techniques to resect or ablate the endometrium versus hysterectomy for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. We consulted with the Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group Information Specialist regarding our search strategies for identifying potential studies for inclusion.

Electronic searches

The original search was performed in 1999. Updated searches were performed in 2008, 2013 and 2018.

The two review authors searched the Gynaecology and Fertility Group's specialised register, ProCite platform (searched 10 December 2018; Appendix 1); CENTRAL via the Cochrane Register of Studies Online (CRSO), Web platform (searched 10 December 2018; Appendix 2); MEDLINE, OVID platform (searched from 1946 to 10 December 2018; Appendix 3); Embase, OVID platform (searched from 1980 to 10 December 2018; Appendix 4); PsycINFO, OVID platform (searched from 1806 to 10 December 2018; Appendix 5).

Searching other resources

The principal review author searched the following trial registers for ongoing trials: ClinicalTrials.gov (a service of the US National Institutes of Health); and the World Health Organization International Trials Registry Platform search portal (www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx) in December 2018 (Appendix 6).

We also searched citation lists of all studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria of the review, studies found in the literature review stage of the introduction, other relevant studies and evidence‐based guidelines on the management of abnormal bleeding.

Data collection and analysis

We performed statistical analysis in accordance with guidelines described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). When possible, we pooled outcomes statistically.

Selection of studies

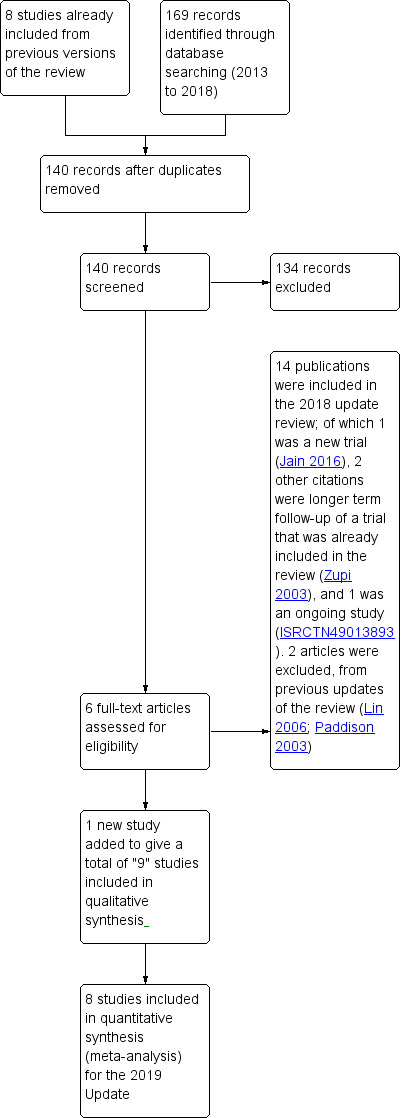

Trials for inclusion in the review were selected by two of the review authors (AL and IC or AL and SS in 2008, RJF and AL in 2013, RJF and MBR in 2019) after the search strategy described previously was employed. This task was undertaken independently, and the final list of included studies reflected consensus between the two review authors. Details of the screening and selection process are shown in Figure 1.

1.

Study screening and selection process (2013 to 2018).

Data extraction and management

All assessments of characteristics of the included studies were performed independently by two review authors (AL and IC in 2008, RJF and AL in 2013, MBR and RJF in 2019) using forms designed according to Cochrane guidelines and described in Higgins 2011.

When necessary, additional information on trial methodology or original trial data were sought from the principal or corresponding author of any trials that appeared to meet the eligibility criteria (see Acknowledgements section for details of the study authors who provided clarification of data beyond that reported in the publications).

Quality criteria and methodological details were extracted from each study as follows.

Trial characteristics

Study design.

Numbers of women randomly assigned, excluded and lost to follow‐up.

Whether an intention‐to‐treat analysis was done.

Whether a power calculation was done.

Duration, timing and location of the study.

Number of centres.

Source of funding.

Characteristics of study participants

Age and any other recorded characteristics of participants in the study.

Other inclusion criteria.

Exclusion criteria.

Type of surgery.

Source of participants.

Proportion participating of those eligible.

Interventions used

Type of endometrial destruction technique used and route of hysterectomy performed.

Outcomes

Methods used to evaluate menstrual symptoms (e.g. PBAC score, woman‐defined 'improvement in symptoms').

Methods used to measure requirement for further surgery for HMB.

Methods used to evaluate participant satisfaction and change in quality of life post surgery.

Methods used to record adverse surgical events.

Methods used to measure resource and individual costs.

Methods used to measure duration of surgery, hospital stay and recovery time.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Included trials were assessed for risk of bias using the 'Risk of bias tool' developed by the Cochrane Collaboration (known simply as 'Cochrane' since February 2015) and described in Higgins 2011.

Sequence generation (whether the allocation sequence was adequately generated to produce comparable groups).

Allocation concealment (whether the allocation was adequately concealed).

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (whether knowledge of the allocated intervention was adequately controlled during the study).

Incomplete outcome data (whether incomplete outcome data were adequately addressed).

Selective outcome reporting (whether reports of the study were free of the suggestion of selective outcome reporting).

Other sources of bias (whether the study was apparently free of other problems that could put it at high risk of bias, e.g. baseline imbalance, bias related to study design, early termination of the study).

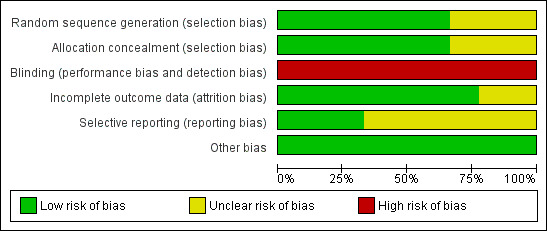

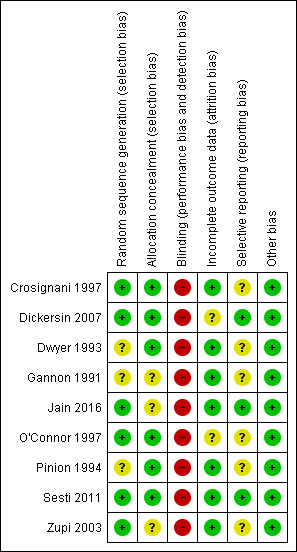

Details of the risk of bias for each included study are displayed in Characteristics of included studies and are summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data (e.g. number of adverse outcomes), we used the numbers of events in the control and intervention groups of each study to calculate risk ratios (RRs). For continuous data (e.g. PBAC score), if all studies reported exactly the same outcomes, we calculated mean differences (MDs) between treatment groups. If similar outcomes were reported on different scales, we calculated the standardised mean difference (SMD). We reversed the direction of effect of individual studies, if required, to ensure consistency across trials. We treated ordinal data (e.g. quality of life scores) as continuous data. We presented 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all outcomes. When data needed to calculate RRs or MDs were not available, we utilised the most detailed numerical data available that may facilitate similar analyses of included studies (e.g. test statistics, P values). We compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies versus how they were presented in the review, while taking account of legitimate differences.

For dichotomous data (e.g. proportion of participants satisfied with their treatment), results of each study were expressed as a risk ratio. For some dichotomous outcomes (e.g. proportion of participants requiring further surgery), a higher proportion represented a negative consequence of that treatment, and for other outcomes (e.g. proportion with improvement in menstrual blood loss), a higher proportion was considered a benefit of treatment. This approach to the categorising of outcomes should be noted when summary graphs for the meta‐analysis are viewed for assessment of benefits as opposed to harms of treatment. Thus, for some dichotomous outcomes, treatment benefit has been displayed as risk ratios and confidence intervals to the left of the centre line, but for others, a treatment benefit has been shown to the right of the centre line. Each outcome was labelled for clarification.

For other outcomes for which high values were considered a negative consequence of treatment—for example duration of surgery, length of hospital stay and time to return to work—evaluation of the summary graphs reveals that means and confidence intervals to the left were considered a benefit of endometrial destruction.

With one exception, quality of life scores were entered as continuous data—mean plus standard deviation values post treatment. One study, however, recorded the percentage mean change of EuroQol scores from baseline to four months after treatment. Some scales measured general quality of life summary score; others reported results separately in different categories, representing general quality of life but without a summary score; still others used more specific measurements of aspects of quality of life, such as anxiety, social adjustment and depression.

For some outcomes, women were assessed at different periods of follow‐up after surgery.

Menstrual symptoms were recorded at one, two, three and four years after surgery, PBAC scores at one and two years after surgery, and quality of life at four months and one, two and four years post treatment.

Adverse events were recorded before and after discharge from hospital.

Requirement for further surgery was measured separately within the first year and at two, three and four years after treatment.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the woman with HMB who was randomly assigned to endometrial resection/ablation or to hysterectomy.

Dealing with missing data

We analysed data on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible; otherwise we only analysed available data. When we found that data were missing, we made attempts to obtain this information from the original trial authors.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We examined heterogeneity (variations) between the results of different studies by visual inspection of scatter of data points on the graphs and overlap in their confidence intervals. More formally, we examined the results of the I² statistic (a quantity that describes approximately the proportion of variation in point estimates that is due to heterogeneity rather than sampling error; Higgins 2008). When we found statistical heterogeneity to be very substantial (> 90%), we considered calculation of a summary effect measure to be inappropriate and we did not pool study data. Results of these studies can be viewed in forest plots that portray the range of values for comparison in each study.

Assessment of reporting biases

We aimed to avoid reporting bias by using a robust search strategy with no restrictions on language or publication forum. We identified multiple publications of the same study for several of the included studies and we have referenced them as such. If we had found 10 or more studies to include in the analysis we planned to use funnel plots to explore the possibility of small‐study effects.

Data synthesis

Combination of data was not always possible, as some outcomes were measured differently (e.g. some trials used PBAC score as a measure of improvement in bleeding, whilst others used proportion reporting improvement in bleeding symptoms, proportion with excessive bleeding, etc.). We displayed such data in the forest plots; however, often only one trial contributed data to each plot.

For continuous data (e.g. PBAC score), if all studies reported exactly the same outcomes we calculated mean differences (MDs) between treatment groups. We displayed continuous outcomes differently according to whether benefit or harm was measured. For most quality of life scores, a high score represented a benefit of treatment, but for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD), a high score represented a greater degree of anxiety or depression. To present on the same graph quality of life scales that differed in this way, we displayed HAD scores as minus values, so that we could include all quality of life continuous outcomes in a single forest plot.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

A priori, we planned to explore the possible contribution of differences in trial design to any heterogeneity identified in the manner described above under Assessment of heterogeneity.

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a meaningful summary. Where meta‐analyses were able to be performed, we checked for heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plots for evidence of poor overlap of the 95% CIs. More formally, we used the Chi2 test (with a P value < 0.10 being evidence of significance) and the I2 value. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011) suggested a rough guide for interpretation of I2 values:

0% to 40% might not be important;

30% to 60% may represent moderate heterogeneity;

50% to 90% may represent substantial heterogeneity;

75% to 100% was considered substantial heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

To assess the robustness of pooled estimates, we conducted the following sensitivity analysis.

Estimates based on all relevant trials regardless of evidence of allocation concealment versus estimates based on trials that provided clear evidence that allocation was concealed.

We planned but did not conduct the following analysis.

Estimates based on all relevant trials regardless of missing data and loss to follow‐up versus estimates based on trials in which incomplete outcome assessment was not likely to cause bias.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' table

We generated Table 1 using GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). This table evaluates the overall quality of the body of evidence for the main review outcomes (woman's perception (proportion with improvement in bleeding symptoms), PBAC score, proportion requiring further surgery for HMB, proportion satisfied with treatment, and adverse events‒short term) using GRADE criteria.

Study limitations (i.e. risk of bias).

Consistency of effect.

Imprecision.

Indirectness.

Publication bias.

We justified, documented and incorporated judgements about evidence quality (high, moderate, low or very low) into reporting of results for each of these main outcomes.

Results

Description of studies

We included nine RCTs comparing techniques of removal or ablation of endometrium versus hysterectomy by any route for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding, together with one ongoing trial. Four of these trials had multiple publications, each based on the same study population but providing assessment of different outcomes and different follow‐up times, as well as cost‐utility analyses of previously published data (Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003). We did not consider trials comparing different types of endometrial destruction in this review but they are assessed in Bofill Rodriguez 2019. Details of included studies can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Study design

All included studies used a parallel‐group design. Seven of these studies were carried out at a single centre: three in Italy (Crosignani 1997; Sesti 2011; Zupi 2003); three in the UK (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994); and one in India (Jain 2016). One study was performed at nine centres throughout the UK (O'Connor 1997); and one study was completed at 25 centres in the USA and Canada (Dickersin 2007).

Participants

Participants in all included studies were premenopausal, had symptomatic heavy menstrual bleeding (regular or irregular prolonged or excessive bleeding) and were eligible for (i.e. had shown no response to medical treatment) or were awaiting hysterectomy. Participants in seven of the included studies had received a diagnosis of menorrhagia (heavy regular bleeding) (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Sesti 2011; Zupi 2003), and participants in two of the studies had been given a diagnosis of dysfunctional uterine bleeding (which was defined as both regular and irregular ovulatory heavy bleeding and anovulatory abnormal bleeding not due to pathology) (Dickersin 2007; Pinion 1994). Exclusion criteria included large fibroids ((over 50% intramural extension (Crosignani 1997); or over 5 cm (Jain 2016)), large uterine size over 12 gestational weeks (Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997; Zupi 2003), pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) (Gannon 1991), and endometriosis (Gannon 1991) and abnormal pathology. Four studies excluded participants with submucosal fibroids (Crosignani 1997; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Zupi 2003).

Interventions

Available data mostly compared first‐generation ablation techniques (predominantly transcervical resection of the endometrium (TCRE)) versus total hysterectomy. Two trials compared TCRE versus abdominal hysterectomy (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991); the former trial also included a preoperative procedure (medroxyprogesterone acetate injection four to six weeks before surgery) to reduce the thickness of the endometrium for participants undergoing endometrial resection. One trial compared endometrial resection versus vaginal hysterectomy (Crosignani 1997); another trial compared endometrial resection versus hysterectomy (50% abdominal, 50% vaginal) (O'Connor 1997); and another trial compared endometrial destruction after preoperative gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) treatment (50% endometrial resection and 50% laser ablation) versus hysterectomy (88% abdominal and 12% vaginal) (Pinion 1994). One study compared endometrial resection or thermal balloon ablation (according to surgeon's choice) versus total hysterectomy (vaginal, laparoscopic or abdominal approach, according to surgeon's choice) (Dickersin 2007); another study compared endometrial resection after preoperative GnRH agonist (GnRHa) treatment versus laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (Zupi 2003); and the final study compared thermal balloon endometrial ablation versus laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (Sesti 2011).

Outcomes

Follow‐up after surgery for all included studies ranged from four months to four years. Seven studies assessed change in menstrual bleeding patterns (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Jain 2016; Pinion 1994; Sesti 2011); five of these assessed whether menorrhagia‐like symptoms had resolved (amount and frequency of bleeding), one study (in which participants had a complaint of dysfunctional bleeding) measured separate components of bleeding excess (excessive amount and duration) and another study used PBAC questionnaires. Four studies assessed time to return to work in weeks (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994). Two studies in which participants had a diagnosis of dysfunctional bleeding assessed whether an improvement in overall symptoms had occurred (recorded in one trial as 'problem solved') (Dickersin 2007; Pinion 1994). Three studies measured costs of treatment (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994).

Four studies assessed satisfaction with surgery (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994) (although this was reported at different follow‐up times); postoperative complications were reported by five trials (Gannon 1991; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Sesti 2011); and duration of surgery was reported in six trials (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Zupi 2003). Seven studies assessed hospital stay (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003); and requirement for further surgery was reported by eight trials (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003).

Some outcomes measured time of surgery or recovery time and strictly speaking were time‐to‐event outcomes, such as duration of surgery, length of stay in hospital and time to return to normal activities and work. However, these were analysed as continuous data, as all participants had initial and end values representing the time that had elapsed. Time‐to‐event analysis is mandatory when censoring is performed and only a subset of participants have an event, but the authors in this review considered comparison of means to be an acceptable analysis.

Seven studies assessed quality of life after surgery (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Sesti 2011; Zupi 2003), but several different scales were used. This review has assessed quality of life as measured by the Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State (one year after surgery), the Short Form‐36 Scale (SF‐36), the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) and the Sabbatsberg Sexual Rating Scale (all one or two years after surgery). The SF‐36 is a generic measure of subjective health in the form of a profile with eight multi‐item dimensions (including physical and emotional role limitation, physical and social functioning, mental health, energy, pain and general health perception) developed in the USA and shown to be an acceptable tool when used by women with HMB (Coulter 1994; Ware 1993). The EuroQol health instrument is a generic single index measure of health‐related quality of life validated in several European countries, including the UK (Brazier 1993; EuroQol Group 1990). The Golombok Rust Inventory was modified by the investigators to obtain a brief measure of the overall quality of the marital relationship (Rust 1986), and the Sabbatsberg Sexual Rating Scale was designed to provide a self‐assessment of sexual functioning by women engaging in intercourse (Garrat 1995). The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale is a self‐assessment mood scale specifically designed to identify states of anxiety and depression and is regarded as a valid measure of the severity of these mood disorders (Zigmond 1983). Several other scales were used to evaluate aspects of quality of life in some of the trials, including the SF‐12, General Health Questionnaire, the Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale, a psychiatric mood scale, a modified social adjustment scale and an unvalidated questionnaire, but we did not enter these outcomes into the review because the data were not obtained in a suitable form for inclusion in a meta‐analysis (quantitative data provided in graphical form indicated significant skew; data could not be obtained from study authors).

Five publications from three trials (Cameron 1996 and Aberdeen 1999 from the Pinion 1994 study; Gannon 1991; and Sculpher 1998 and Sculpher 1996 from the Dwyer 1993 study) compared costs to the health service of the two techniques. Two of these trials had two publications reporting total health resource costs of the procedures (including the need for retreatment) at different follow‐up times (Cameron 1996 and Aberdeen 1999 (Pinion 1994); Sculpher 1993 and 1996 (Dwyer 1993). One trial measured direct costs to the participant after one year (Cameron 1996 (Pinion 1994)).

Four publications from two trials (Sculpher 1993 and Sculpher 1996 from Dwyer 1993, and Cameron 1996 and Aberdeen 1999 from Pinion 1994) calculated cost per participant based on resource use. The third trial calculated costs by summing the average costs of variable resources and then adding a factor of 100% to allow for fixed costs (Gannon 1991).

Results of the search

We updated the search in December 2018 and included 140 additional potential references. Two review authors (MB and CL) screened titles and abstracts. We obtained full‐text copies of six references that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria; three were re‐publication of a trial already included in the 2013 review and were added to the included studies, one was a long‐term follow‐up of a trial already included in the review (Zupi 2003), one was an ongoing study (ISRCTN49013893), and one was an additional new trial to be included (Jain 2016), leading to a total of nine trials in the updated review.

Included studies

Nine RCTs of endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy with a total of 1300 randomly assigned participants met the criteria for inclusion in the review, although not all participants contributed to the assessment of every outcome. Six authors were contacted for further details: two replied (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007); four did not (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003)

Excluded studies

In the 2008 update of this review, two studies were retrieved for closer inspection and were excluded from the review (Paddison 2003; Lin 2006). One study had allocation according to date of admission and did not satisfy the criteria for true randomisation, and the other was a review of ablation versus hysterectomy.

No further studies were retrieved for closer inspection but subsequently excluded in the 2013 and 2019 updates of the review.

Risk of bias in included studies

We assessed all included studies separately for risk of bias (Higgins 2011). We provide a summary of these assessments in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Allocation

Six of the nine included studies provided sufficient detail on the adequacy of the randomisation method (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Sesti 2011; Zupi 2003), all at low risk of bias. The other three studies did not describe how randomisation was undertaken and were therefore at unclear risk of bias in this category.

All but three studies provided sufficient details of allocation concealment (Gannon 1991; Jain 2016; Zupi 2003); these three studies were therefore at unclear risk of bias, and all other studies were at low risk of bias in this category.

Blinding

Three of the more recent studies used single blinding for assessment of some outcomes (Dickersin 2007; Sesti 2011; Zupi 2003). The other six studies did not appear to have any blinding of participants, investigators or assessors. All studies were therefore at high risk of bias in this category.

Incomplete outcome data

In two studies (Dickersin 2007; O'Connor 1997), withdrawal from the study and/or missing data were greater than 10%, and explanations were not provided to enable judgement of whether this could have biased the results. In one trial (Dickersin 2007), primary outcomes were analysed by an intention‐to‐treat method (satisfaction rate, quality of life and bleeding outcomes), but intraoperative and perioperative outcomes (adverse events, requirement for further surgery and hospital stay) were analysed according to surgery received. This trial also reported outcomes at three and four years' follow‐up, but as women who were assigned later during the trial had shorter follow‐up, these assessments are likely to be underpowered. The other seven studies had withdrawals of less than 10% at the time of calculation of outcomes at the first time point. However, in studies with longer follow‐up, additional loss to follow‐up increased with the duration of the trial.

Selective reporting

Sufficient information was provided in only one study to indicate that it was free of selective outcome reporting (Dickersin 2007). Before publication of the study results, an earlier publication provided details of the study protocol and changes made throughout the study (Dickersin 2007: 2003 paper on Dickersin 2007). Two studies reported all the outcomes that were previously specified (Jain 2016; Sesti 2011). The other studies did not provide any evidence of measures taken to prevent selective outcome reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

In all of the studies, groups were balanced at baseline. In three studies the prior experience of the operating surgeon was described (Gannon 1991; O'Connor 1997; Zupi 2003). This was not described in the remainder of the studies, however, and could be a potential source of bias, as a less experienced surgeon for either treatment group could alter results such as duration of surgery, adverse outcomes and, in the case of endometrial ablation, effectiveness.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

1 Endometrial resection and ablation versus hysterectomy

Primary outcomes

Effectiveness

Hysterectomy is probably associated with better bleeding outcomes when compared to endometrial ablation. These were assessed in different ways in the trials, and we could not pool all outcomes.

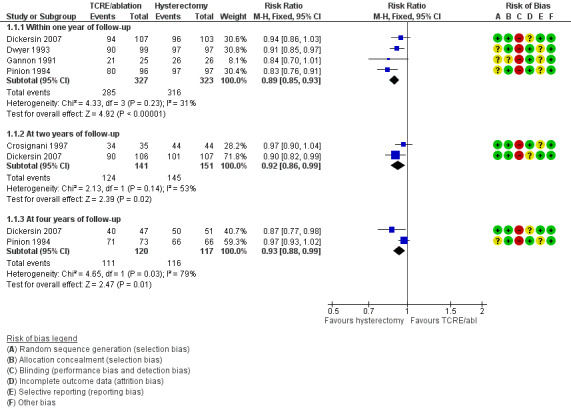

1.1 Woman's perception (proportion with improvement in bleeding symptoms)

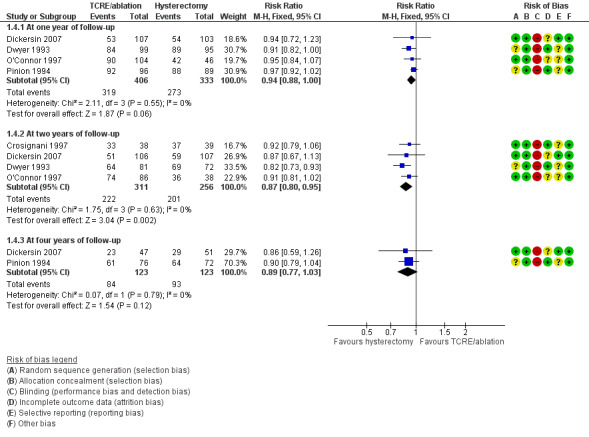

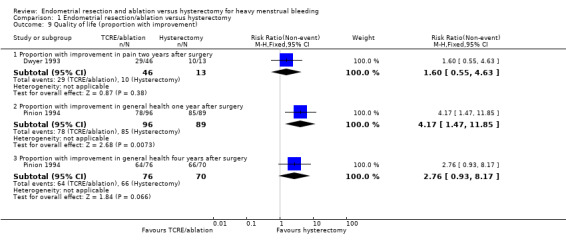

Five trials assessed whether bleeding symptoms were perceived as improved (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994). Women randomly assigned to endometrial ablation were less likely to show improvement in bleeding symptoms when compared with those randomly assigned to hysterectomy at one year (RR 0.89, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.85 to 0.93; 4 studies, 650 women, I² = 31%; low‐quality evidence) (Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994). Differences were also noted at later stages of follow‐up, but the effect reduced over time: at two years (RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.86 to 0.99; 2 studies, 292 women, I² = 53%) (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007); and at four years (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99; 2 studies, 237 women, I² = 79%; Figure 4; Analysis 1.1) (Dickersin 2007; Pinion 1994).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, outcome: 1.1 Woman's perception (proportion with improvement in bleeding symptoms).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 1 Woman's perception (proportion with improvement in bleeding symptoms).

1.2 PBAC score

One trial assessed menstrual blood loss using the PBAC (Pictorial Blood Loss Assessment Chart) score (Sesti 2011). Compared with pretreatment scores, the PBAC score was clearly reduced in both groups at one and two years postoperatively; however, this finding overall favoured women randomly assigned to hysterectomy at one year (MD 24.40, 95% CI 16.01 to 32.79; 1 study, 68 women), and even more so at two years (MD 44.00, 95% CI 36.09 to 51.91; 1 study, 68 women; moderate‐quality evidence, Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 2 PBAC score (continuous data).

1.3 Requirement for further surgery

Risk of repeat surgery for failure of the initial surgical treatment was reported at different follow‐up times. Six trials reported the requirement for further surgery at one year's follow‐up (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003); and six reported at two years' follow‐up (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997; Sesti 2011; Zupi 2003). One trial reported it at three years' follow‐up (O'Connor 1997); and one at four years' follow‐up (Pinion 1994). The risk of having a further surgery for treatment failure was more likely for TCRE/ablation than for hysterectomy at all follow‐up periods (all eight trials contributed data for at least one time point): within the first year (RR 16.17, 95% CI 5.53 to 47.24; 7 studies, 927 women, I² = 0%; low‐quality evidence), at two years (RR 34.06, 95% CI 9.86 to 117.65; 6 studies, 930 women, I² = 0%), at three years (RR 22.90, 95% CI 1.42 to 370.26; 1 study, 172 women), and at four years (RR 36.32, 95% CI 5.09 to 259.21; 1 study, 197 women) (Figure 5; Analysis 1.3). One study reported three requirements for further surgery on the hysterectomy group, but two were oophorectomies and one cystoscopy for persistent urinary symptoms after the surgery (O'Connor 1997), but no further surgery for HMB. One study reported 14 years' follow‐up with clear evidence of difference favouring hysterectomy (RR 19.60, 95% CI 1.15 to 333.63; 1 study, 153 women), but with more than 20% lost to follow‐up in the ablation group (18 women; 11 declined to participate and 7 could not be contacted).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, outcome: 1.3 Proportion requiring further surgery for HMB.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 3 Proportion requiring further surgery for HMB.

Acceptability

1.4 Proportion satisfied with treatment

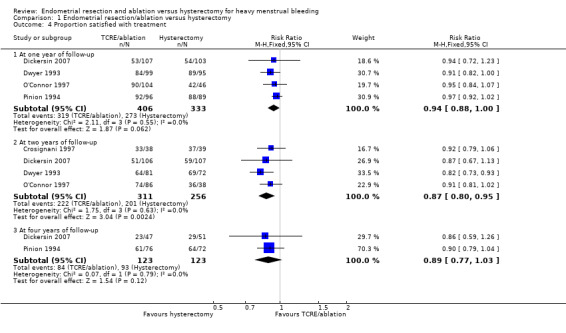

Satisfaction (very or moderately satisfied) rates were compared in five trials (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994). Although satisfaction rate was lower amongst those who had endometrial ablation at two years after surgery (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.95; 4 studies, 567 women, I² = 0%; moderate‐quality evidence), no evidence of clear difference was reported between post‐treatment satisfaction rates in groups at other follow‐up times (1 and 4 years) (Figure 6; Analysis 1.4).

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, outcome: 1.4 Proportion satisfied with treatment.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 4 Proportion satisfied with treatment.

Safety (adverse events)

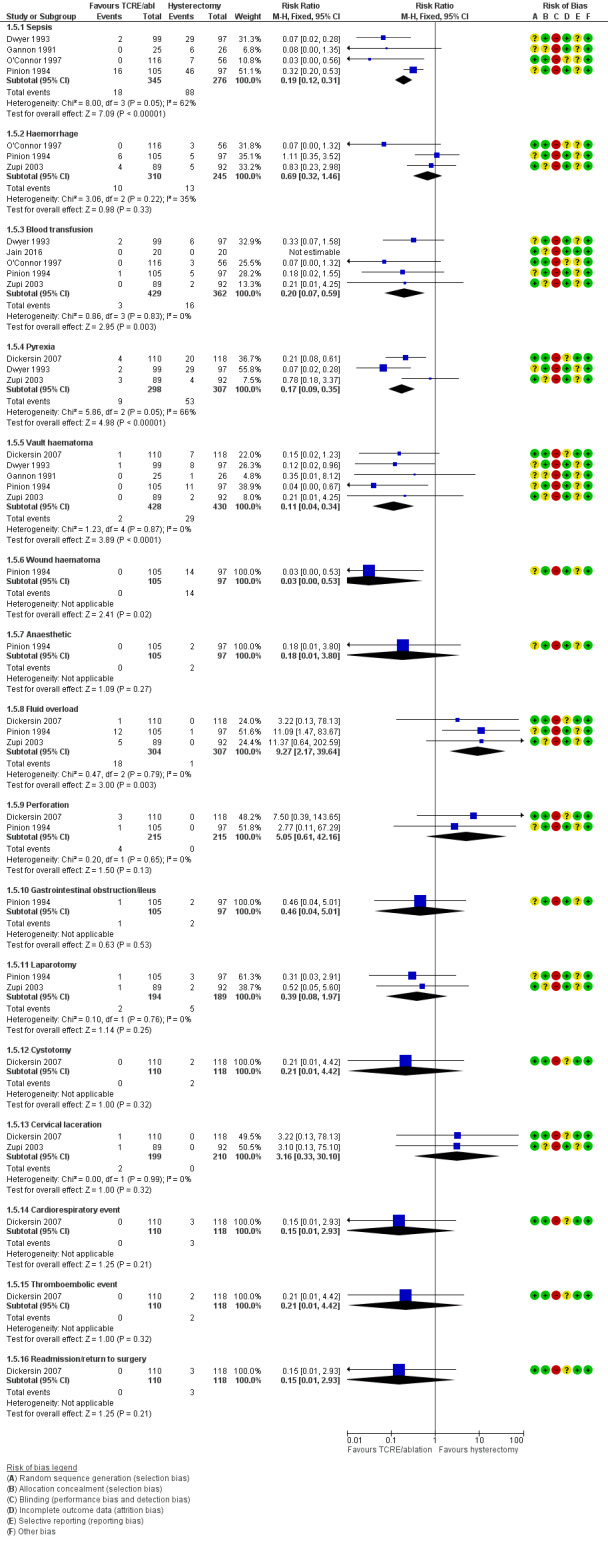

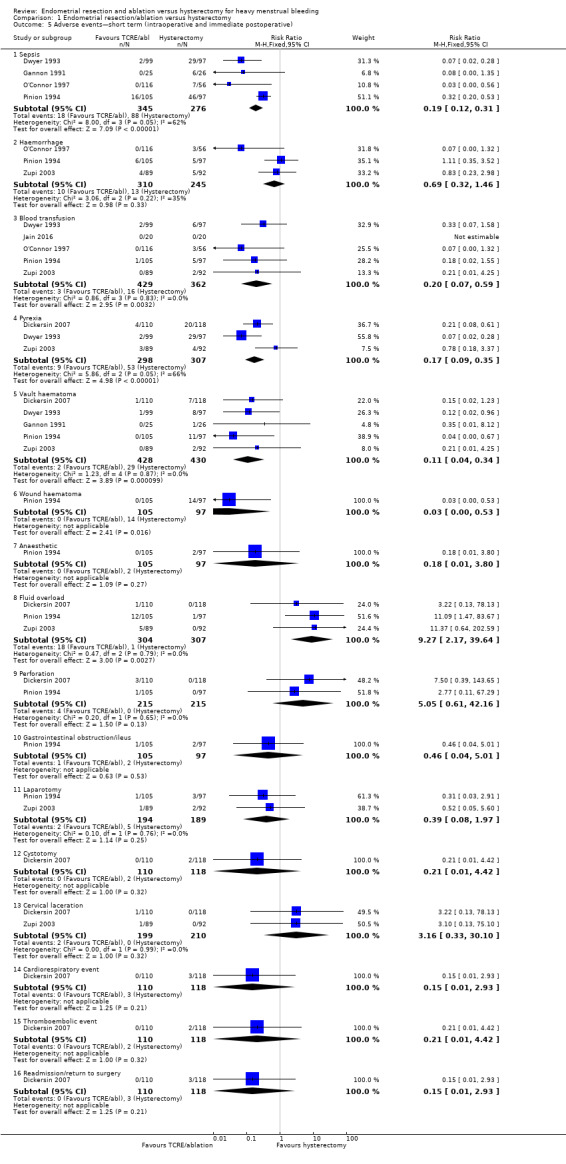

1.5 Adverse events: short term (intraoperative and immediately postoperative)

Six trials reported short‐term adverse effects, assessing sixteen different types (Figure 7; see Analysis 1.5) (Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003). Other than sepsis, there was no clear evidence of difference between groups regarding (eventually) life‐threatening complications.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, outcome: 1.5 Adverse events—short term (intraoperative and immediate postoperative).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 5 Adverse events—short term (intraoperative and immediate postoperative).

There was clear evidence of difference between endometrial resection or ablation and hysterectomy favouring endometrial resection or ablation in the following adverse effects.

Sepsis (RR 0.19, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.31; 621 women; 4 studies; I2 = 62%; low‐quality evidence) (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994).

Blood transfusion (RR 0.20, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.59; 5 studies, 791 women, I² = 0%) (Dwyer 1993; Jain 2016; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003).

Pyrexia ((RR 0.17, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.35; participants = 605; studies = 3; I2 = 66%) (Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Zupi 2003)

Vault haematoma (RR 0.10, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.30; 5 studies, 858 women, I² = 0%) (Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003).

Wound haematoma ((RR 0.03, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.53; 202 women; 1 study) (Pinion 1994).

However, there was clear evidence of difference between endometrial resection or ablation and hysterectomy favouring hysterectomy in fluid overload (RR 9.27, 95% CI 2.17 to 39.64; 611 women; 3 studies; I2 = 0%) (Dickersin 2007; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003).

There was no clear evidence of difference between groups for:

haemorrhage (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.46; 3 studies, 555 women, I² = 35%);

anaesthetic complications (RR 0.18, 95% CI 0.01 to 3.80, 1 study, 202 women) (Pinion 1994);

perforation (RR 5.05, 95% CI 0.61 to 42.16; 2 studies, 430 women, I² = 0%) (Dickersin 2007; Pinion 1994);

gastrointestinal obstruction (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.04 to 5.01; 1 study, 202 women) (Pinion 1994);

laparotomy (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.97; 2 studies, 383 women, I² = 0%) (Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003);

cystotomy (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.42; 1 study, 228 women) (Dickersin 2007);

cervical laceration (RR 3.16, 95% CI 0.33 to 30.10; 409 women; 2 studies; I2 = 0%) (Dickersin 2007; Zupi 2003)

cardiorespiratory event (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.93; 228 women; 1 study) (Dickersin 2007);

thromboembolic event (RR 0.21, 95% CI 0.01 to 4.42, 1 study, 228 women) (Dickersin 2007);

readmission or return to surgery as causes of postoperative complications (RR 0.15, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.93; 1 study, 228 women) (Dickersin 2007)

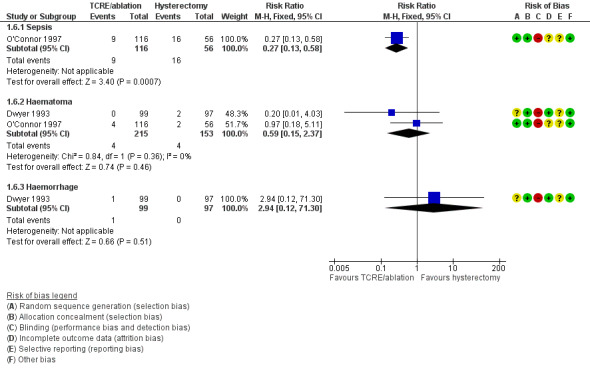

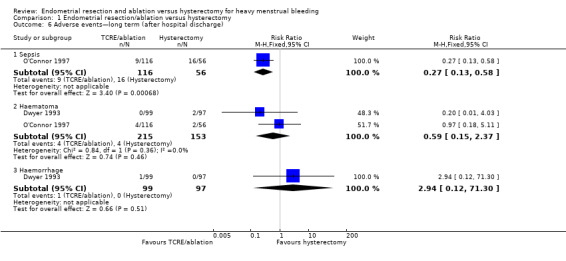

1.6 Adverse events: long term (after hospital discharge)

Adverse events after hospital discharge were reported in two trials (Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997). There was clear evidence of difference in sepsis rate between the two groups favouring endometrial resection or ablation ((RR 0.27, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.58; 1 study, 172 women) (O'Connor 1997).

There was no clear evidence of difference between groups after hospital discharge in terms of haematoma (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.37; 2 studies, 368 women, I² = 0%) (Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997); and haemorrhage (RR 2.94, 95% CI 0.12 to 71.30; 1 study, 196 women) (Dwyer 1993).

No other adverse events were reported. See Figure 8; Analysis 1.6.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, outcome: 1.6 Adverse events—long term (after hospital discharge).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 6 Adverse events—long term (after hospital discharge).

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life

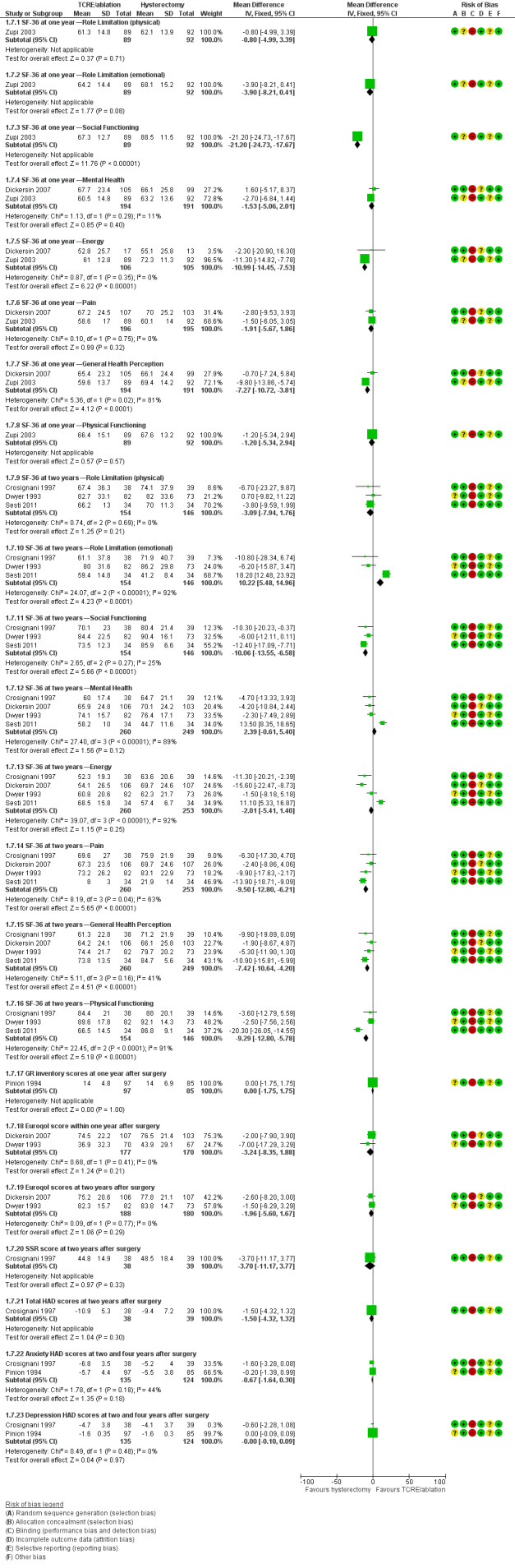

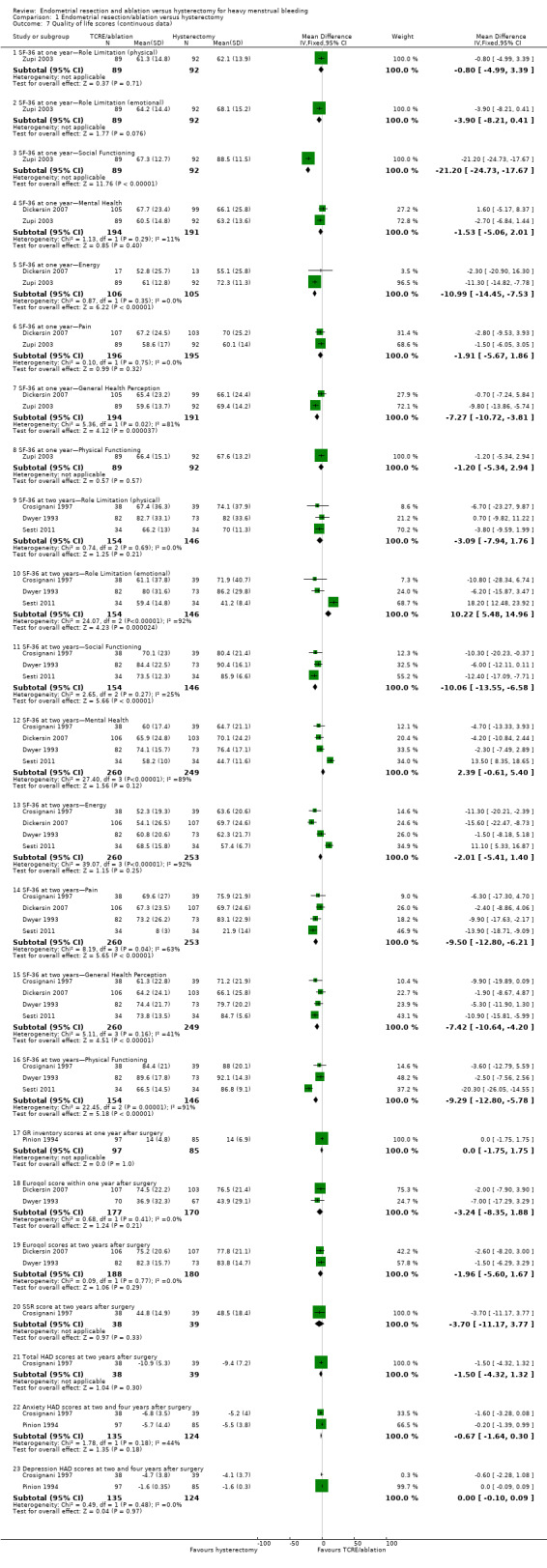

Quality of life was measured by a number of validated scales. It was not possible to combine scales, as the domains differed, measuring different aspects of quality of life.

1.7 Quality of life scores (continuous data)

We detected clear evidence of difference between groups in five domains of the SF‐36 scale measured one and two years after surgery.

There was clear evidence of difference between groups favouring hysterectomy in:

social functioning at one year (MD ‐21.20, 95% CI ‐24.73 to ‐17.67, 1 study, 181 women) (Zupi 2003); and two years (MD ‐10.06, 95% CI ‐13.55 to ‐6.58; 3 studies, 300 women, I² = 25%) (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Sesti 2011);

pain at two years (MD −9.50, 95% CI −12.80 to −6.20; 4 studies, 513 women, I² = 63%) (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Sesti 2011);

Energy at one year (MD ‐10.99, 95% CI ‐14.45 to ‐7.53, 211 women,2 studies; I² = 0%) (Dickersin 2007; Zupi 2003);

General health perception at one year (MD ‐7.27, 95% CI ‐10.72 to ‐3.81; 2 studies, 385 women, I² = 81%) (Dickersin 2007; Sesti 2011); and two years (MD ‐7.42, 95% CI ‐10.64 to ‐4.20; 4 studies, 509 women, I² = 41%) (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Sesti 2011).

There was clear evidence of difference between groups favouring endometrial ablation and resection in:

emotional role limitation at two years (MD 10.22, 95% CI 5.48 to 14.96; 3 studies, 300 women, I² = 92%) (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Sesti 2011).

We noted no clear evidence of differences in SF‐36 scores between the two interventions in the domains of physical role limitation, mental health and physical functioning (Figure 9; Analysis 1.7).

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, outcome: 1.7 Quality of life scores (continuous data).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 7 Quality of life scores (continuous data).

1.8. Quality of life at 14 years' follow‐up

One trial reported physical and mental quality of life at 14 years' follow‐up (Zupi 2003), suggesting a higher quality of life in the hysterectomy group compared to the ablation group. The physical component ranged from 57.50 to 51.40 for the hysterectomy group and from 55.04 to 45.40 for the ablation group. On the mental component, the hysterectomy group ranged from 56.80 to 50.40 and the ablation group ranged from 51.90 to 36.10. We could not enter these data on the meta‐analysis (See Analysis 1.8)

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 8 Quality of life at 14 years follow up.

| Quality of life at 14 years follow up | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Hysterectomy group | Endometrial ablation group | Heading 3 |

| Zupi 2003 | Physical score ranged from 57.5 to 51.4 Mental score ranged from 56.8 to 50.4 |

Physical score ranged from 55.04 to 45.4 Mental score ranged from 51.9 to 36.1 |

P < 0.0001 (for both) |

1.9 Quality of life (proportion with improvement)

Differences between groups were not reported in quality of life dimensions as measured by any of the other scales: Golombok Inventory, EuroQol scale, Sabbatsberg scale or HAD scale. The dichotomous outcome of proportion with improvement in pain at two years did not differ between surgical groups. However, a greater proportion of those who had undergone a hysterectomy reported an improvement in their general health one year after surgery when compared with those who had received TCRE/ablation (RR (Non‐event) 4.17, 95% CI 1.47 to 11.85; 1 study, 185 women) (Pinion 1994). At four years, this difference between groups had narrowed and did not report a clear difference (RR (Non‐event) 2.76, 95% CI 0.93 to 8.17; 146 women) (Analysis 1.9) (Pinion 1994).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 9 Quality of life (proportion with improvement).

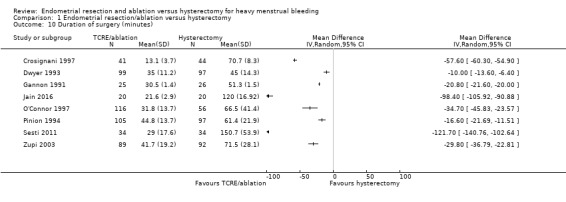

1.10 Duration of surgery

The duration of surgery was available in all but one trial (Dickersin 2007) and reported a clear difference between groups, being longer for hysterectomy in all eight trials, and ranging from ten minutes' to two hours' average difference between trials. We do not include a pooled estimate in this analysis as we noted a high degree of heterogeneity, as discussed below under 'Heterogeneity' (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 10 Duration of surgery (minutes).

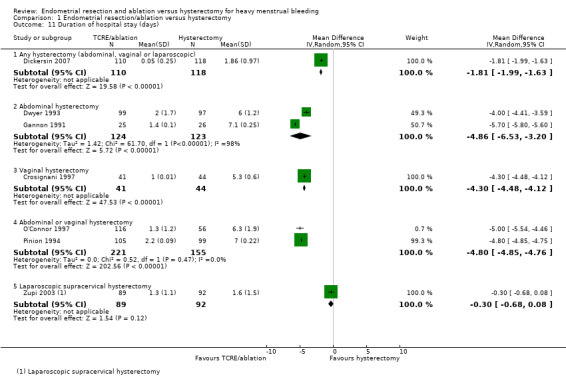

1.11. Duration of hospital stay

Seven trials evaluated this outcome (Crosignani 1997; Dickersin 2007; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994; Zupi 2003). We do not include a pooled estimate in this analysis as we noted a high degree of heterogeneity (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 11 Duration of hospital stay (days).

Mean differences in hospital stay showed clear evidence of difference for all the hysterectomy groups when compared with TCRE/ablation, being shorter in the TCRE/ablation groups in the following comparisons.

TCRE/ablation versus abdominal hysterectomy (MD −4.86, 95% CI −6.53 to −3.20; 2 studies, 247 women, I² = 98%) (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991).

TCRE/ablation versus vaginal hysterectomy (MD −4.30, 95% CI −4.48 to −4.12; 1 study, 85 women) (Crosignani 1997).

TCRE/ablation versus either abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy (MD −4.80, 95% CI −4.85 to −4.76; 2 studies, 376 women) (O'Connor 1997; Pinion 1994).

TCRE/ablation versus any route of hysterectomy (MD −1.81, 95% CI −1.99 to −1.63; 1 study, 228 women) (Dickersin 2007).

There was no clear evidence of difference in the duration of hospital stay between TCRE/ablation and laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (MD −0.30, 95% CI −0.68 to 0.08; 1 study, 181 women) (Zupi 2003).

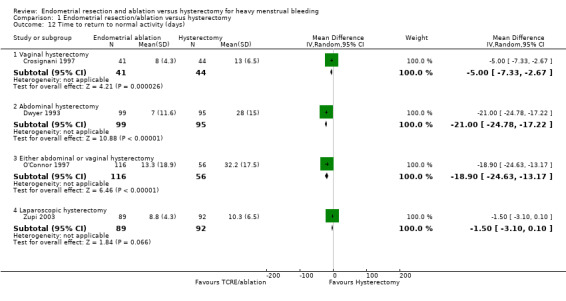

1.12. and 1.13 Time to return to normal activity and Time to return to work

Time to return to normal activity (in days) was reported in four trials (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; O'Connor 1997; Zupi 2003). There was clear evidence of difference between groups favouring endometrial ablation or resection, ranging from 1.5 to 21 days. We do not include a pooled estimate in this analysis as we noted a high degree of heterogeneity, as discussed below under 'Heterogeneity' (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 12 Time to return to normal activity (days).

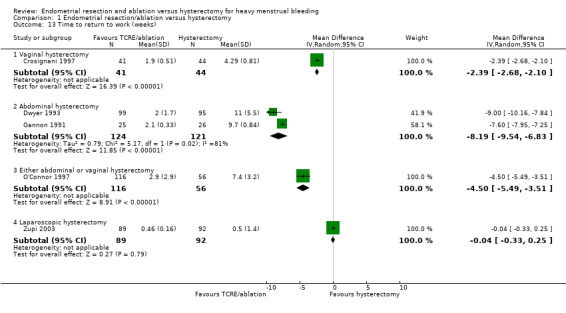

Time to return to work (in weeks) was reported in five trials (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; O'Connor 1997; Zupi 2003). There was clear evidence of difference between groups favouring endometrial resection and ablation in four trials, ranging from 2.4 to 9 weeks (Crosignani 1997; Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; O'Connor 1997); in Zupi 2003 there was no clear evidence of difference between groups. We do not include a pooled estimate in this analysis as we noted a high degree of heterogeneity (Analysis 1.13). Abdominal hysterectomy was associated with the greatest difference in time to return to normal activities (MD 21 days, 95% CI ‐24.78 to ‐17.22) and time to return to work (MD 8.2 weeks,95% CI ‐9.54 to ‐6.83) when compared with TCRE/ablation (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991). For the same outcomes, when TCRE/ablation was compared against vaginal hysterectomy (MD 5 days, 95% CI 7.33 to 2.67; MD 2.4 weeks,95% CI 2.68 to 2.10, respectively) (Crosignani 1997), the difference was less, particularly when compared against laparoscopic hysterectomy (MD 1.5 days, 95% CI 3.10 to 0.10 and MD 0.04 weeks, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.25, respectively) (Zupi 2003).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 13 Time to return to work (weeks).

1.14. Total health service cost per woman

Three trials assessed the costs (Dwyer 1993; Gannon 1991; Pinion 1994). There was clear evidence of difference between groups favouring endometrial ablation and resection for the management of heavy menstrual bleeding at short‐term follow‐up. This difference continued over a prolonged follow‐up time, but the cost gap narrowed primarily because of the retreatment rate for women who underwent endometrial resection. By four years, ablation techniques cost between 5% and 11% less than a hysterectomy in one study that evaluated long‐term follow‐up (Aberdeen 1999 (Pinion 1994); Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 14 Total health service cost per woman.

| Total health service cost per woman | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Dwyer 1993 | FOUR MONTHS FOLLOW UP

Mean resource cost per patient (UK pounds) in 1991/92 prices:

Endometrial resection: UK pounds 560.05 (SD 261.22)

Hysterectomy: UK pounds 1059.73 (SD 198.04)

These costs were made up of pre‐operative, operative and post‐operative costs, hotel costs, complications costs, re‐treatment and general practice costs.

Mean difference in cost between groups : UK pounds ‐499.68 (95% CI ‐567 to ‐432)

Statistical test not specifically stated.

Mean cost of resection at 4 months follow up 53% the cost of hysterectomy. 2.2 YEARS OF FOLLOW UP Mean resource cost per patient (UK pounds) in 1994 prices: Endometrial resection: UK pounds 790 (SD 493) Hysterectomy: UK pounds 1110 (SD 168) Costs made up of initial surgery, re‐treatment costs, other resource use after 4 months and HRT. Wilcoxon Rank Sum test used to test the difference between groups with a 5% significance level, p=0.0001. Mean cost of resection at 2.2 years of follow up 71% the cost of hysterectomy. |

| Gannon 1991 | INITIAL COSTS (NHS) Mean cost per operation (UK pounds) in 1991: Endometrial resection: UK pounds 407 Abdominal hysterectomy: UK pounds 1270 This cost was made up of: (1) variable costs: average cost of theatre consumables, staffing and maintenance in the operating theatre, marginal cost of a bed on the gynaecological ward; and (2) fixed costs: capital depreciation, hospital staffing and energy. The difference between groups in resource cost was not assessed in a statistical test. |

| Pinion 1994 | ONE YEAR OF FOLLOW UP

Mean resource cost per patient in UK pounds in 1994:

Endometrial resection: UK pounds 1001.00

Laser ablation: UK pounds 1046.00

Hysterectomy: UK pounds 1315.00

No statistical test used to compare the difference between groups.

Mean cost of endometrial resection at 1 year of follow up 76% of cost of hysterectomy.

Mean cost of laser ablation at 1 year of follow up 80% of cost of hysterectomy.

Costs based on pre‐operative costs, nights in hospital, theatre and ward costs, GP and out‐patient costs, re‐treatment costs and technical equipment costs. FOUR YEARS OF FOLLOW UP Mean resource cost per patient in UK pounds in 1994: Endometrial destruction techniques: UK pounds 1231 Hysterectomy: UK pounds 1332 Includes additional costs for re‐treatment or additional procedures arising between 1 and 4 years after surgery. Data reported as 1994 rates (discounted by 6%). Sensitivity analysis performed with variations in the discount rate. Cost of endometrial ablation techniques at 4 years reported as between 89% and 95% the costs of hysterectomy. |

1.15. Total individual cost per woman

One trial measured costs to the women (Cameron 1996 (Pinion 1994)). At one‐year follow‐up, total personal costs, in terms of travel, loss of pay and child care, were higher for women who had a hysterectomy than for women who underwent endometrial ablation. However, women who had a hysterectomy estimated greater savings in the cost of sanitary protection when compared with those who underwent endometrial ablation (savings of GBP 85.10 per year versus GBP 58.30 per year; Analysis 1.15).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Endometrial resection/ablation versus hysterectomy, Outcome 15 Total individual cost per woman.

| Total individual cost per woman | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Pinion 1994 | ONE YEAR OF FOLLOW UP

Mean patient cost in UK pounds in 1994 prices:

Hysteroscopic surgery: UK pounds 21.00 (95% CI 13.3, 33.1)

Hysterectomy: UK pounds 73.40 (95% CI 42.1, 127)

Mean cost of hysteroscopic surgery 29% the cost of hysterectomy surgery.

Costs estimated included loss of pay, child care and travel expenses.

Student t test used to compare differences between surgery groups, p<0.05. Mean annual savings from sanitary protection after treatment in UK pounds in 1994: Hysteroscopic surgery: UK pounds 58.30 (95% CI 51.4, 66) Hysterectomy: UK pounds 85.10 (95% CI 72.2, 100) Student t test used to compare differences between surgery groups, p<0.05. |

Funnel plots

We were unable to include enough studies in the review for funnel plots to have sufficient power to distinguish chance from true asymmetry.

Heterogeneity

We observed a high level of heterogeneity for some outcomes.

For many outcomes, only one trial contributed data, and analysis of heterogeneity was therefore not applicable. Data were, however, contributed from several or all trials for four outcomes and we visually inspected the forest plots for these outcomes. The estimate for proportion requiring further surgery showed a low level of heterogeneity (all confidence intervals overlapping and I² = 0% at one and two years of follow‐up). However, a very high degree of heterogeneity was evident for outcomes such as duration of surgery (I² = 99%), time to return to work (I² = 100%) and time to return to normal activities (I² = 97%).

The level of clinical heterogeneity for these outcomes may be explained in part by differences in interventions (most notably, mode of hysterectomy) throughout the trials. Two trials included abdominal hysterectomies only (Dwyer 1993;Gannon 1991); one trial included only vaginal hysterectomies (Crosignani 1997); and two trials included only laparoscopic hysterectomies (Zupi 2003; Sesti 2011). All other studies included two or all modes of hysterectomy. We conducted a sensitivity analysis as set out below to investigate this further.

All trials had similar risk profiles for most measures in the 'Risk of bias' table. We therefore assume that no significant methodological heterogeneity was present.

Sensitivity analysis

We performed an analysis to investigate the effect of clear evidence of allocation concealment on estimates. For six of the eight trials, clear evidence indicated that allocation was concealed, but for two trials (Gannon 1991 and Zupi 2003), this was not the case. When we included only trials with clear evidence of allocation concealment in the meta‐analysis, there was no significant change in the estimates compared with inclusion of all trials.

We planned but did not conduct the following analysis: estimates based on all relevant trials regardless of missing data and loss to follow‐up versus estimates based on trials for which incomplete outcome assessment was not likely to cause bias. We did not conduct this analysis as no data were missing from the included trials.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This review assessed the benefits and harms of two types of surgical procedures for the treatment of heavy menstrual bleeding. When the primary outcomes of this review—effectiveness (woman's perception of improvement in bleeding outcomes, PBAC score, requirement for further surgery), acceptability and safety (satisfaction with treatment and adverse outcomes)—are considered, this review shows that both hysterectomy and endometrial ablation and resection are effective, acceptable and safe surgical treatments for heavy menstrual bleeding.

Whilst hysterectomy is more effective at reducing bleeding symptoms and improving quality of life and is associated with less repeated surgery than endometrial ablation, considerable short‐term benefits are associated with endometrial ablation and resection techniques when compared with hysterectomy, mainly in the areas of recovery time and cost.

Hysterectomy was completely successful in treating bleeding problems (over 96% success in all trials at different follow‐up times). Endometrial ablation and resection techniques were also highly successful in reducing menstrual blood loss in most participants, but a proportion of participants (ranging from 3% to 18%) showed no improvement. At most durations of follow‐up, regardless of how bleeding symptoms were measured, women in the hysterectomy groups showed a greater reduction in symptoms than those in the endometrial ablation‐resection groups. For some outcomes, it was suggested that these differences were no longer experienced at longer durations of follow‐up; this might be due to a number of reasons, including reduced numbers, retreatment in the TCRE/ablation group and some women reaching menopause.

Hysterectomy led to very high levels of participant satisfaction up to four years after surgery. Satisfaction levels were also high for women who underwent endometrial ablation‐resection but they were lower for these women when compared with hysterectomy at two time periods.

Most quality of life measures were not markedly different between the two types of surgery, although evidence from analysis of SF‐36 scores shows that women who had a hysterectomy perceived greater benefit for their general health, social functioning and energy levels at both one and two years and for pain levels at two years after surgery was completed compared with those having endometrial ablation. All other aspects of quality of life as measured by different instruments did not differ between groups.

Both surgical treatments were considered to be safe, with low complication rates reported. However, hysterectomy was associated with higher rates of sepsis, pyrexia, requirement for blood transfusion, and haematoma of the vault and wound.