Abstract

During the last 6 months of life, 75% of older adults with preexisting serious illness, such as advanced heart failure, lung disease, and cancer, visit the emergency department (ED). ED visits often mark an inflection point in these patients’ illness trajectories, signaling a more rapid rate of decline. Although most patients are there seeking care for acute issues, many of them have priorities other than to simply live as long as possible; yet without discussion of preferences for treatment, they are at risk of receiving care not aligned with their goals. An ED visit may offer a unique “teachable moment” to empower patients to consider their ability to influence future medical care decisions. However, the constraints of the ED setting pose specific challenges, and little research exists to guide clinicians treating patients in this setting. We describe the current state of goals-of-care conversations in the ED, outline the challenges to conducting these conversations, and recommend a research agenda to better equip emergency physicians to guide shared decisionmaking for end-of-life care. Applying best practices for serious illness communication may help emergency physicians empower such patients to align their future medical care with their values and goals.

INTRODUCTION

During the last 6 months of life, 75% of older adults with preexisting serious, life-limiting illness, such as advanced heart failure, lung disease, and cancer, visit the emergency department (ED).1 An ED visit by an older adult often represents an inflection point in the trajectory of illness, after which function and quality of life tend to decline more rapidly.2-4 Older adults being discharged from the ED are at 37% higher risk of loss in their activities of daily living4 and have an increasingly difficult time accessing primary care because of their physical disability from the severity of their illness.5 For patients admitted to the hospital, the intensity of care determined in the ED often continues during the hospitalization, and by default that care plan is most often focused on life-prolonging interventions.6 However, older adults with serious illness may possess priorities other than simply living as long as possible. These may include maximizing time at home, preserving dignity, and finding relief from suffering.7 Yet 56% to 99% of older adults do not have advance directives available at ED presentation.8 Therefore, these ED visits present an opportune “teachable moment” in that patients are a captive audience, with a mean length of stay of 4 hours9 and a change in health status that is likely to reflect overall disease progression.4 This is an opportune moment for physicians to empower patients who are able to formulate and communicate their goals for immediate or future medical care. The challenge is to take advantage of this “teachable moment” by identifying and engaging older adults with serious illness while they are in the ED.

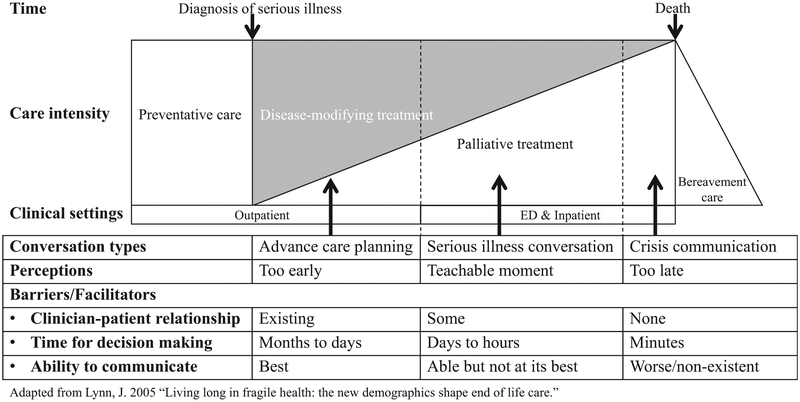

In 2016, the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference released a consensus statement on the state of shared decisionmaking in the ED,10 emphasizing that excellent emergency care depends on enhanced shared decisionmaking toward the end of life. Shared decisionmaking can only occur after goals-of-care conversations that explore patients’ values and preferences. For seriously ill older adults, goals-of-care conversations are associated with improved quality of life, lower rates of in-hospital death, less aggressive medical care near death, earlier hospice referrals, increased peacefulness, and a 56% greater likelihood of having wishes known and followed.11-18 For caregivers, such conversations are associated with better bereavement adjustment12 and reduced distress in decisionmaking.19,20 Furthermore, patients who participate in these conversations have 36% lower cost of end-of-life care in the last week of life, with average cost savings of $1,041 per patient.21 Such conversations should preferentially occur in outpatient settings in which patients have long-standing relationships with their physicians.22 Yet determining the “right time” to have a conversation about future care preferences is difficult in outpatient settings, and only 37% of patients with cancer have conversations about end-of-life care with their physicians,12 with the first conversation occurring on average 33 days before death.23 Clinician-level barriers to discussing end-of-life care include uncertainty about prognosis,24 fear of provoking anxiety,25 and time constraints.26 Patient-level barriers include passivity,27 lack of knowledge,28 and denial of the reality of life’s trajectory toward death.29 As a result, in the outpatient care setting, both patients and physicians frequently perceive the conversation about future care preferences to be too early, which results in less advance care planning (Figure 1).30,31

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of goals-of-care conversations in the ED.

When seriously ill patients arrive in the ED with a hyperacute clinical crisis, the “crisis communication” becomes challenging because there is less time to make critical decisions, less time to develop a patient-clinician relationship, and decreased ability to communicate because of clinical instability (the conversation is perceived to be too late). Many seriously ill patients in the ED, however, are not critically ill. Because the ED visit signals a patient’s clinical decline, untapped opportunities exist to introduce or reinitiate the conversation about future care preferences in the context of evident clinical decline (possibly a teachable moment).

Emergency physicians often encounter older adults with serious illness at an opportune moment; however, previously published research on goals-of-care conversations in the ED are limited by small sample sizes,32,33 and most represent expert commentaries.34-36 The present state of practice and opportunities to improve such conversations are not well understood. We provide a conceptual framework of goals-of-care conversations in the ED to identify areas of future research. This framework reflects the review of existing literature and inputs from emergency medicine and palliative care experts. Given the novelty of ED goals-of-care conversation and the relative dearth of published work on the topic, the value of a systematic review is limited. Therefore, the lead author (K.O.) solicited narrative inputs on this topic from selected experts in palliative medicine, goals-of-care conversations, and aging research with track records of publications or funding (C.L., R.S., M.A.S., S.D.B., and J.A.T.). Then we sought local emergency physicians with expertise in palliative care, communication interventions, and health policy (N.R.G., J.D.S., E.L.A., and E.B.) to identify the information thought to be most relevant to the practice of emergency medicine.

GOALS-OF-CARE CONVERSATIONS IN THE ED: THE “CRISIS COMMUNICATION” VERSUS THE “SERIOUS ILLNESS CONVERSATION”

In the ED, 2 types of goals-of-care conversations, hyperacute and subacute, tend to take place, depending on the acuity of the medical issues and the urgency of decisionmaking. In the hyperacute clinical setting, a patient with underlying serious illness experiences an acute decompensation in health, prompting him or her to seek care in the ED (eg, acute pulmonary edema from heart failure decompensation). These medical emergencies require emergency physicians and patients or caregivers to engage in goals-of-care conversations during which they rapidly decide between multiple treatment strategies, each leading down a divergent path (eg, intubation versus comfort care only). We refer to such goals-of-care conversations as “crisis communication.”

Other patients present to the ED at some point during a more long-term decline (eg, dehydration, failure to thrive), and the visit serves as an inflection point in their illness trajectory, portending a worsening course.2-4 These seriously ill patients may or may not have had goals-of-care conversations with their outpatient clinicians, and the ED visit is an indicator of a likely change in clinical status. Some of these patients may have changed their previously stated preferences,37 which may require reinitiation of the conversations about future care preferences. In this subacute situation, emergency physicians often act as the intermediaries to other clinicians in inpatient or outpatient settings, who will have more time to make difficult decisions with the patient. Here, the role of the emergency physician is to support patients in formulating or reformulating future care preferences and to encourage them to discuss their preferences with their outpatient or inpatient clinicians. We refer to these conversations as “serious illness conversations” (Figure 1).30

In both circumstances, emergency physicians lack evidence-based, practical methods to guide seriously ill patients to discuss their values and preferences for future care. Some emergency physicians recognize the opportunity an ED visit presents to discuss goals of care, and many have expressed interest in engaging older adults with serious illness in goals-of-care conversations.38 However, the lack of training in serious illness communication and the time-pressured ED environment discourage emergency physicians from conducting detailed conversations with these patients.39 Also, the skills and tools for such conversations differ in these 2 settings. Practical methods are needed to help emergency physicians guide these difficult conversations with the patients in this setting.

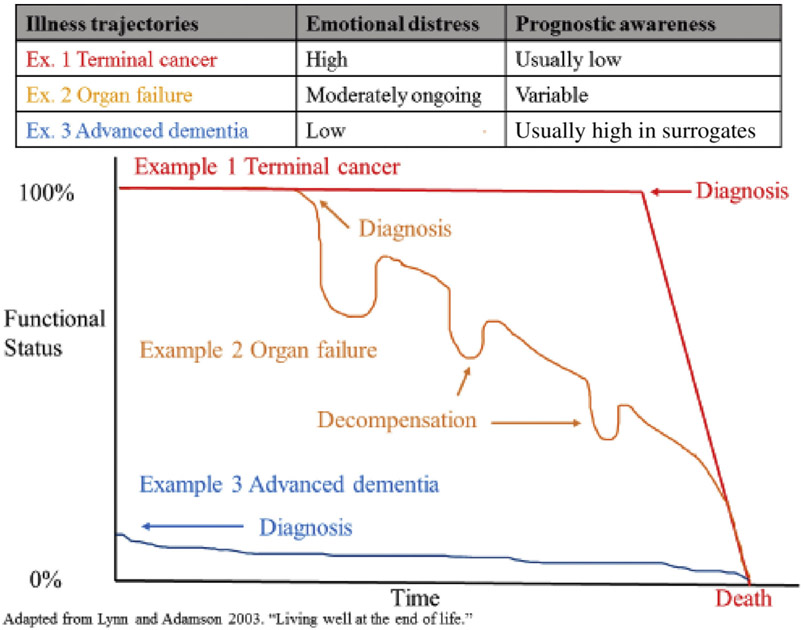

Challenges and Opportunities in Crisis Communication

Although every patient’s illness is unique, most seriously ill older adults will experience episodes of decompensation and stability that fit 1 of 3 common patterns known as a “serious illness trajectory” (Figure 2).40 The illness trajectory of patients with advanced organ failure often differs radically from the trajectory of those living with terminal cancer. Although these trajectories do not necessarily convey any information about individual patients, understanding of these patterns provides important insight into their likely emotional status and prognostic awareness (ie, how aware they are about their own prognosis). Among 1,193 incurable lung and colorectal cancer patients, 50% to 65% reported that it was “very likely” or “somewhat likely” that their chemotherapy would cure their cancer, despite having been informed about its palliative intent.29 When these patients visit the ED, their prognostic awareness is expected to be low. In contrast, the surrogates of patients with advanced dementia may be more aware of the expected course of illness because of a longer duration of progressive clinical decline.41 Recognizing that a given patient’s health crisis may fit into a pattern of decline may help ED clinicians to recognize the communication type necessary during an ED visit.

Figure 2.

Serious illness trajectories and patients’ or surrogates’ emotional status and awareness of prognosis tendencies.

With minimal time to develop familiarity with patients, their illness, or their goals of care,2,3,6 emergency physicians are tasked with rapidly communicating medical updates, disclosing bad news, exploring a patient’s values and preferences, and navigating initial treatment decisions (eg, intubation). However, few have studied these challenges in practice or tested interventions to mitigate them.19,24 Guidelines for goal-of-care conversations have been developed by palliative care, internal medicine, surgery, and other fields.22,25-28 These guidelines provide neither recommendations for conversations during an acute clinical decompensation when time is of the essence nor strategies adapted for the ED context. Initial efforts to adapt palliative care communication skills to the ED environment are underway and appear promising.42 The crisis communications and decisionmaking in the ED are likely to have a tremendous influence on the patient’s subsequent trajectory.43-45

Research Gaps for Crisis Communications in the ED

Empiric studies of the frequency, content, barriers or facilitators, and quality of crisis communication in the ED, as well as strategies to improve it, are needed.

Question 1: What are the incidence and contextual circumstances (eg, clinical, environmental) of crisis communications in the ED?

No empiric studies that describe the incidence and contextual circumstances of crisis communications exist, to our knowledge. Thus, observational and ethnographic investigations of clinicians and patients or caregivers involved in ED crisis communication will be essential to developing our understanding of these phenomena in situ. Important questions to address include the following:

What are the common clinical scenarios in which ED crisis communication must occur? Ideally, advance care planning occurs before institution of life-sustaining treatment (cardiopulmonary resuscitation, intubation, vasopressor use, dialysis, and emergency surgery) or before significant escalation of care (transfer to a tertiary center or ICU).

What kinds of decisions are made during these conversations?

Who is involved in this decisionmaking (eg, surrogate)?

How long does it take to conduct these conversations?

What are reasonable milestones to complete in these conversations in the ED?

What is the extent of shared decisionmaking during these conversations?

How do decisionmakers and ED clinicians (physicians and nurses) perceive these conversations?

What are the outcomes considered most important by patients, family, decisionmakers, and health care providers from these conversations?

Question 2: What are the barriers and facilitators of crisis communications in the ED?

After the patterns of crisis communication in the ED are understood, clinical and contextual barriers and facilitators must be determined. Identifying patient, caregiver, and system factors associated with the crisis communication can further elucidate the essential next steps to improving patient-centered outcomes. Key research questions to consider include the following:

What factors would make ED clinicians more likely to have ED crisis communication when a decision for intervention is urgent but not an emergency (eg, shock on vasopressors but not requiring intubation)?

What factors would empower patients or surrogates to seek out ED crisis communication when not offered by ED clinicians?

What are the expert recommended circumstances in which a health system should mandate that ED crisis communication occur?

Which types of ED clinicians can best have these conversations with patients? Can additional members of the health care team (eg, social workers, care managers) have outcomes similar to those of physicians or nurses?

Question 3: What are clinically meaningful patient-centered outcomes of the crisis communications in the ED?

Understanding clinically meaningful patient-centered outcomes of crisis communications will help in designing and measuring the effect of an intervention to standardize the crisis communication in the ED. Potential outcomes might include patient or caregiver satisfaction, decisional conflict, knowledge about prognosis and expected course of events after the patient leaves the hospital, and patient or caregiver behaviors leading to further discussion of end-of-life care preferences (eg, writing down what to ask and communicating it to the treating clinician). Additionally, early identification and documentation of a surrogate decisionmaker(s), early family meetings for admitted patients, burden of subsequent life-sustaining treatments sustained by the patient, and ultimate disposition of the patient (eg, home, hospice, nursing home) are potentially important patient-centered outcomes. Finally, the effects of crisis communication improvements on health care use (ie, hospital length of stay) and cost will be valuable.

Question 4: What are acceptable and scalable best practices for the crisis communications in the ED?

Best practices in serious illness communication exist in non-ED settings (eg, key questions to ask, communication skills to explore patient values).22,46 However, it is unclear how to adapt these practices to the ED settings to achieve outcomes that matter most to the patients. Key questions to address are the following:

What are the expert-recommended, patient- or surrogate-accepted, and scalable methods to conduct ED crisis communications?

How are the best practices perceived by ED clinicians, patients, and surrogates when implemented?

What are the differences between crisis communication practices for patients in a trauma context versus medically ill one?

What are strategies to disseminate the implementation of the best practices in emergency medicine nationally?

Challenges and Opportunities in Serious Illness Conversations

Emergency physicians have competing priorities in the ED to address the most life-threatening problems first; this imperative may make it challenging to focus on outcomes that may not have an immediately apparent result. Although emergency physicians often see the need for serious illness conversations, they are often unsure of their roles in these conversations in relation to those of other physicians, lack an effective and practical method to initiate or reintroduce this conversation, and lack a process to communicate the handoff to inpatient or outpatient clinicians who will continue the discussion. There have not been efforts to investigate the best means of engaging older adults in serious illness conversations, to our knowledge. Further research to evaluate structured conversations, decision aids, prognostic tools, and clinician training necessary to conduct structured conversations would help focus intervention development on promising approaches.47

A brief negotiated interview intervention is a patient-centered approach used in the ED in other contexts (eg, substance abuse disorder) to facilitate engagement and activation of the patient for a behavior change (eg, alcohol abstinence). Brief negotiated interview interventions use clinicians’ empathetic, reflective listening to elicit behavior change by helping patients to evoke discrepancy between their own goals (eg, having control over medical decisions about their care) and their current behavior (eg, having no advance directive) and ultimately resolve ambivalence.48 The brief negotiated interview elicits the patient perspective and allows the emergency physician to respectfully provide information, motivation, and resources to empower the patient. Such interventions allow patients to take better control of their health care decisions, which promotes better health outcomes and care experiences.49 Brief negotiated interview interventions in the ED for substance abuse disorders have been shown to be effective in reducing future abuse.50-54 These studies demonstrate that emergency physicians can engage patients in brief negotiated interview interventions not directly related to acute care. A brief negotiated interview method for serious illness conversations in the ED has been developed and found to be acceptable to seriously ill older adults.55,56 The brief negotiated interview intervention for serious illness conversation in the ED is designed to engage seriously ill older adults to formulate their values and preferences; therefore, the intervention is intended to encourage detailed conversation with the outpatient clinician regardless of the patient’s preferences for life-prolonging care. It is not intended for emergency physicians to talk patients into choosing comfort-only care.

Research Gaps for Serious Illness Conversation in the ED

Several research gaps remain in establishing evidence-based approaches to supporting serious illness conversations in the ED.

Question 1: What are the critical tasks that must be accomplished in the ED to help ensure follow-up in other, more appropriate settings after the ED visit?

In non-ED settings, key elements of the serious illness conversations that are tested for validity with patients are understanding of prognosis, information preference, patient goals, fears and worries, functional ability critical for life, acceptable and unacceptable trade-offs, and family involvement.22 It is not yet clear which of these or other tasks are necessary and feasible within the constraints of the ED environment to facilitate communication with the patient’s primary inpatient or outpatient physician. Future studies should focus on qualitative exploration of perspectives of emergency and nonemergency physicians about these issues.

Question 2: What is the appropriate level of participation emergency physicians should seek from caregivers in the ED?

As many as 42% of older adults in the ED may exhibit cognitive impairment.57 Emergency physicians often conduct serious illness conversations not only with the patients but also with the caregivers in this setting. However, to our knowledge research is not available to inform one about the level of participation that caregivers seek in the ED. Qualitative studies to define the role and engagement preferences of caregivers, preferences of clinicians and patients about caregiver involvement in these interactions, and practical tools to optimize interactions with caregivers are needed to improve serious illness conversations in the ED.

Question 3: What are clinically meaningful outcomes that matter the most to patients and caregivers after serious illness conversations in the ED?

As with crisis communications, it is important to characterize meaningful patient-centered outcomes after the serious illness conversations in the ED from both clinicians’ and patients’ and caregivers’ perspectives. Such understanding will allow the design of effective interventions to facilitate shared decisionmaking toward the end of life. Key outcomes to consider and refine with inputs from patients and caregivers may include patient activation, prognostic awareness, and conversation aids for patients to help them know what to ask their primary outpatient clinicians.

Question 4: What is the patient-centered effect of conducting serious illness conversations in the ED?

There is ample evidence of improvement in patient-centered outcomes after serious illness communication intervention(s) across multiple disciplines and practice environments. Outcomes are likely to improve among patients participating in serious illness conversations in the ED as well. However, a prospective study demonstrating these improvements is lacking.

Question 5: Can an ED-based brief negotiated interview intervention improve advance care planning for seriously ill older adults in the ED (eg, documentations, patient engagement, decisional conflict)?

An ED-based brief negotiated interview intervention for serious illness communication is found to be acceptable to seriously ill older adults and can be administered with high fidelity by trained ED clinicians.55,56 Further studies are needed to establish its effects on advance care planning after patients leave the ED.

REIMBURSEMENT FOR CLINICAL CARE

Using Current Procedural Terminology codes, ED clinicians can be financially compensated for leading the conversations about serious illness in the ED. In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services started to reimburse for advance care planning conversations between patients and health care professionals (physicians, physician assistants, and other qualified professionals) to explain, discuss, and complete advance directives.58 The Table provides the details of the new Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Current Procedural Terminology codes (99497 and 99498) and billing requirements. Practices are eligible for reimbursement only from codes 99479 and 99484 for face-to-face communication. Conversations qualify if they are conducted by a physician or any other qualified health care professional, and the patient or his or her family or surrogate decisionmaker. No specific training in communication is required. The first code, 99497, is used to designate the first 30 minutes of discussion. The second code, 99498, is invoked only if the conversation exceeds 30 minutes. Neither code can be reported in addition to critical care services (99291).58

Table.

| CPT codes | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Patient eligibility | No specific diagnosis requirement, enrolled in Medicare |

| Clinician eligibility | Physicians and nonphysician practitioners with minimal direct supervision |

| Place of service | Facility and nonfacility settings |

| Frequency of CPT code use | No limits if changes in health status or wishes about end-of-life care documented |

| Content | ≥15 min of face-to-face explanation and discussion of advance directives with or without completion of such forms by the physician or other qualified health care professional with the patient, family member(s), or surrogate |

| Recommended components of documentation |

Rationale in regard to medical necessity of the advance care planning, content of the discussion, explanation of the advance directives, individuals present, and the time spent in the face-to-face encounter |

| Reimbursement | 1.5 RVU for 99497 and 1.4 RVU for 99498 (approximately $55 per CY2017 physician fee schedule) |

Early observational studies have not shown a significant, direct effect of this change on advance care planning billing or practice.59 The American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) has recognized its potential applications in the ED,60 but this billing mechanism is not widely used among emergency physicians. Establishing a standardized approach to using this Current Procedural Terminology code could help sustain an evidence-based approach to conversations about serious illness in the ED.

CONCLUSION

Most seriously ill patients who visit the ED have not had an opportunity to discuss their goals for end-of-life medical care. The ED visit is a “teachable moment” to introduce or reinitiate such conversations. ED conversations about serious illness care goals and the end of life can be categorized into hyperacute (crisis communication) and subacute (serious illness conversations) scenarios. We present a conceptual model of goals-of-care conversations in the ED—a model stratified by patient acuity—and highlight the gaps in knowledge. Future research should address these challenges to improve the quality of end-of-life care in the ED.

Acknowledgments

Funding and support: By Annals policy, all authors are required to disclose any and all commercial, financial, and other relationships in any way related to the subject of this article as per ICMJE conflict of interest guidelines (see www.icmje.org). Dr. Ouchi is supported by the Grants for Early Medical and Surgical Subspecialists’ Transition to Aging Research award from the National Institute on Aging (R03 AG056449), the Emergency Medicine Foundation, and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Dr. Lindvall is supported by the Cambia Health Foundation. Dr. Sudore is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K24AG054415, P30AG044281). Dr. Schonberg is supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01CA181357). Dr. Tulsky is supported by the National Institute on Aging (UG3AG060626).

Footnotes

Trial registration number:

Contributor Information

Kei Ouchi, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Serious Illness Care Program, Ariadne Labs, Boston, MA; Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA.

Naomi George, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Jeremiah D. Schuur, Department of Emergency Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA.

Emily L. Aaronson, Department of Emergency Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA; Department of Emergency Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Charlotta Lindvall, Division of Palliative Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA; Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA; Department of Medicine, Division of Palliative Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

Edward Bernstein, The Brief Negotiated Interview Active Referral to Treatment Institute, Boston University School of Public Health, and the Department of Emergency Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA.

Rebecca L. Sudore, Department of Medicine, University of California, San Francisco, CA.

Mara A. Schonberg, Department of Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA.

Susan D. Block, Division of Palliative Medicine, Department of Medicine, Serious Illness Care Program, Ariadne Labs, Boston, MA; Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA; Department of Psychiatry, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

James A. Tulsky, Division of Palliative Medicine, Department of Medicine, Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA; Department of Medicine, Division of Palliative Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA.

REFERENCES

- 1.Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31:1277–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deschodt M, Devriendt E, Sabbe M, et al. Characteristics of older adults admitted to the emergency department (ED) and their risk factors for ED readmission based on comprehensive geriatric assessment: a prospective cohort study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilber ST, Blanda M, Gerson LW, et al. Short-term functional decline and service use in older emergency department patients with blunt injuries. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:679–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagurney JM, Fleischman W, Han L, et al. Emergency department visits without hospitalization are associated with functional decline in older persons. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henning-Smith CE, Gonzales G, Shippee TP. Barriers to timely medical care for older adults by disability status and household composition. J Disability Policy Studies. 2016;27:116–127. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Le Conte P, Riochet D, Batard E, et al. Death in emergency departments: a multicenter cross-sectional survey with analysis of withholding and withdrawing life support. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, et al. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284:2476–2482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oulton J, Rhodes SM, Howe C, et al. Advance directives for older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horwitz LI, Green J, Bradley EH. US emergency department performance on wait time and length of visit. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:133–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.George NR, Kryworuchko J, Hunold KM, et al. Shared decision making to support the provision of palliative and end-of-life care in the emergency department: a consensus statement and research agenda. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23:1394–1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ray A, Block SD, Friedlander RJ, et al. Peaceful awareness in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1359–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khandelwal N, Kross EK, Engelberg RA, et al. Estimating the effect of palliative care interventions and advance care planning on ICU utilization: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2015;43:1102–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lakin JR, Block SD, Billings JA, et al. Improving communication about serious illness in primary care: a review. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:1380–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon J, Matosevic T, Knapp M. The economic evidence for advance care planning: systematic review of evidence. Palliat Med. 2015;29:869–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khandelwal N, Benkeser DC, Coe NB, et al. Potential influence of advance care planning and palliative care consultation on ICU costs for patients with chronic and serious illness. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:1474–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen MJ, Prigerson HG, Paulk E, et al. Impact of end-of-life discussions on the reduction of Latino/non-Latino disparities in do-not-resuscitate order completion. Cancer. 2016;122:1749–1756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1211–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wendler D, Rid A. Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:336–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang B, Wright AA, Huskamp HA, et al. Health care costs in the last week of life: associations with end-of-life conversations. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:480–488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernacki RE, Block SD. American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: a prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4387–4395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, et al. Discussing life expectancy with terminally ill cancer patients and their carers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dunlay SM, Foxen JL, Cole T, et al. A survey of clinician attitudes and self-reported practices regarding end-of-life care in heart failure. Palliat Med. 2015;29:260–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsaroop SD, Reid MC, Adelman RD. Completing an advance directive in the primary care setting: what do we need for success? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:277–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hancock K, Clayton JM, Parker SM, et al. Truth-telling in discussing prognosis in advanced life-limiting illnesses: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2007;21:507–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casarett D, Crowley R, Stevenson C, et al. Making difficult decisions about hospice enrollment: what do patients and families want to know? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weeks JC, Catalano PJ, Cronin A, et al. Patients’ expectations about effects of chemotherapy for advanced cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1616–1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynn J. Living long in fragile health: the new demographics shape end of life care. Hastings Cent Rep. 2005; Spec No:S14–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahluwalia SC, Levin JR, Lorenz KA, et al. Missed opportunities for advance care planning communication during outpatient clinic visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:445–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Hopper SS, et al. Does palliative care have a future in the emergency department? discussions with attending emergency physicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith AK, Fisher J, Schonberg MA, et al. Am I doing the right thing? provider perspectives on improving palliative care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:86–93, 93.e81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang DH. Beyond code status: palliative care begins in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69:437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Derse A. The emergency physician and end-of-life care. Virtual Mentor. 2001;3; 10.1001/virtualmentor.2001.3.4.elce1-0104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Limehouse WE, Feeser VR, Bookman KJ, et al. A model for emergency department end-of-life communications after acute devastating events—part II: moving from resuscitative to end-of-life or palliative treatment. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19:1300–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim YS, Escobar GJ, Halpern SD, et al. The natural history of changes in preferences for life-sustaining treatments and implications for inpatient mortality in younger and older hospitalized adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:981–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stone SC, Mohanty S, Grudzen CR, et al. Emergency medicine physicians’ perspectives of providing palliative care in an emergency department. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:1333–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? a review of the evidence. J Support Oncol. 2011;9:87–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lynn J, Adamson DM. Living Well at the End of Life. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Black BS, Fogarty LA, Phillips H, et al. Surrogate decision makers’ understanding of dementia patients’ prior wishes for end-of-life care. J Aging Health. 2009;21:627–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grudzen CR, Emlet LL, Kuntz J, et al. EM talk: communication skills training for emergency medicine patients with serious illness. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6:219–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. Emergency department–initiated palliative care in advanced cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:591–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Childers JW, Back AL, Tulsky JA, et al. REMAP: a framework for goals of care conversations. J Oncol Pract. 2017;13:e844–e850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D’Onofrio G, Degutis LC. Screening and brief intervention in the emergency department. Alcohol Res Health. 2004;28:63–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miller WR. Motivational interviewing: research, practice, and puzzles. Addict Behav. 1996;21:835–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:207–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.D’Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, Pantalon MV, et al. A brief intervention reduces hazardous and harmful drinking in emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:181–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bernstein E, Edwards E, Dorfman D, et al. Screening and brief intervention to reduce marijuana use among youth and young adults in a pediatric emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1174–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, et al. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:49–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bruguera P, Barrio P, Oliveras C, et al. Effectiveness of a specialized brief intervention for at-risk drinkers in an emergency department: short-term results of a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2018;25:517–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sommers MS, Lyons MS, Fargo JD, et al. Emergency department-based brief intervention to reduce risky driving and hazardous/harmful drinking in young adults: a randomized controlled trial. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2013;37:1753–1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leiter RE, Yusufov M, Hasdianda MA, et al. Fidelity and feasibility of a brief emergency department intervention to empower adults with serious illness to initiate advance care planning conversations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;56:878–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ouchi K, George N, Revette AC, et al. Empower seriously ill older adults to formulate their goals for medical care in the emergency department. J Palliat Med. 2018; 10.1089/jpm.2018.0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirschman KB, Paik HH, Pines JM, et al. Cognitive impairment among older adults in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2011;12:56–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: CMS finalizes 2016 payment rules for physicians, hospitals, and other providers. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/AdvanceCarePlanning.pdf. Accessed February 5, 2018.

- 59.Tsai G, Taylor DH. Advance care planning in Medicare: an early look at the impact of new reimbursement on billing and clinical practice. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2018;8:49–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.American College of Emergency Physicians Reimbursement and Coding Committees. Advance care planning FAQ. Available at: https://www.acep.org/Clinical—Practice-Management/Advance-Care-Planning-FAQ/#sm.000000csebfyfchdhxry3ohfdgmft. Accessed February 6, 2018 [Google Scholar]