Abstract

Context:

Cancer afflicts almost all communities worldwide. Although it arises de novo in many instances, a significant proportion of oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) develops from potentially malignant disorders (PMDs). Further, the association of Candida with various potentially malignant and malignant lesions has been reported as a causative agent.

Aims:

The aim of the study is to evaluate and intercompare the predominant candidal species among individuals with PMD and OSCC.

Subjects and Methods:

The swab samples were collected for the microbiological culture followed by incisional biopsy for histopathological confirmation. The swab samples were streaked and incubated on Sabouraud-dextrose agar medium and positive candidal colonies were incubated on CHROM agar for speciation.

Settings and Design:

A total of clinically diagnosed 95 subjects of which 25 as normal controls, 30 as PMDs and 40 as OSCC were included. The collected swab samples were initially streaked and incubated on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) medium, and later, only positive candidal colonies were incubated on CHROM agar for speciation.

Statistical Analysis:

Chi-square test was utilized.

Results:

Positive candidal growth on SDA medium was seen in 24%, 43% and 82% and negative in 76%, 57% and 18% individuals of normal controls, PMDs and OSCC, respectively. On evaluation on Chromagar medium, Candida species was present in 20%, 40% and 77% and absent in 80%, 60% and 23% individuals among controls, PMDs and OSCC group, respectively. On speciation of Candida in CHROMagar among the controls, PMDs and OSCC, Candida albicans species was present in 4 (16%), 7 (23%) and 4 (10%); Candida krusei in 1 (4%), 5 (17%) and 10 (25%); Candida glabrata in nil, nil and 6 (20%) and Candida tropicalis in nil, nil, and 2 (5%) cases, respectively.

Conclusion:

There was predominant carriage of candidal species in PMDs and OSCC, but whether Candida has specific establishment in PMDs or in malignancy is still a matter of debate.

Keywords: Candida albicans, carcinogenesis, CHROMagar, oral squamous cell carcinoma, potentially malignant disorders, Sabouraud dextrose agar

INTRODUCTION

Oral cancer is currently the most frequent reason of cancer associated deaths among Indian men.[1] Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is a leading form of head-and-neck cancer in India, Pakistan, and other Southeast Asian countries. However, oropharyngeal and tongue cancers are common in the Western world.[2] Most oral cancers are squamous cell carcinoma, and some oral carcinomas are preceded by potentially malignant disorders (PMDs) that can present as leukoplakia, erythroplakia or erythroleukoplakia. Microscopically, these lesions may unveil oral epithelial dysplasia (OED), a histological diagnosis characterized by cellular changes and maturation disturbances symbolic of evolving malignancy.[3] The OED is a significant risk factor in predicting consequent development of invasive carcinoma.[4]

The World Health Organization (1978) recommended that clinical presentations of the oral cavity that are recognized as precancer be classified into two broad groups, as lesions and conditions.[5] In a recently held workshop, a recommendation to abandon the distinction between potentially malignant lesions and conditions and to use the term PMDs was proposed, as it expresses that not all lesions and conditions described under this term may transform into cancer.[6]

Oral leukoplakia is the best-known precursor lesion.[7] The clinical type of leukoplakia has a bearing on the prognosis since the nonhomogeneous leukoplakias containing an erythematous, nodular and/or verrucous component have a predisposition for hyphal invasion and have higher malignant potential than the homogeneous ones.[8] Oral submucous fibrosis (OSMF) is a high-risk precancerous condition that predominantly affects Indian youngsters due to the habit of gutkha chewing. Another PMD is oral lichen planus (OLP) which is an immunologically mediated mucocutaneous disease. Usually, they appear bilaterally unlike leukoplakia and are often superimposed with candidal infection.[9] Symptoms of OLP may be exacerbated by Candida overgrowth or infection. Candida albicans is present in about 37% of OLP lesions. Some C. albicans isolates with special genotypic profiles and virulence attributes had been considered to cause development and progression of OLP.[10]

C. albicans has the potential to infect virtually any tissue within the body.[11] The role of Candida in oral neoplasia was first reported in 1969. Few studies have also indicated that the presence of candidal infection increases the risk of malignant transformation in premalignant lesions.[9,12,13] It was proved that Candida plays a role in the development of cancer production by endogenous nitrosamine production which activates proto-oncogenes.[1]

Therefore, coexistence of Candida species within humans either as commensals or as pathogens has been a matter of interest among physicians. Further, the connotation of Candida with various potentially malignant and malignant lesions has been reported as a causative agent.[7,11,14] Thus, the present study was undertaken to evaluate and intercompare the different biotypes of Candida species associated with the various individuals among PMDs and OSCC.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

The present study was conducted in the Department of Oral Pathology and Microbiology, Institute of Dental Sciences, Bareilly. All the study individuals were selected from the Outpatient Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology and from Keshlata Cancer Institute, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh, India.

Cooperative individuals confirmed clinically with PMDs and OSCC were included in the study. Patients on topical or systemic corticosteroid therapy, long-term broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, history of immunocompromised conditions such as HIV, diabetes mellitus and severe anemia, had not underwent any chemotherapy, radiotherapy or antifungal treatment were excluded from the study.

A total number of 95 individuals were included, of which 25 individuals were without any obvious clinically diagnosed lesions as normal healthy controls, 30 individuals clinically diagnosed as PMDs such as oral leukoplakia, OSMF and OLP and 40 individuals clinically diagnosed as OSCC patients.

The ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethical committee for human experimentation as per the standard guidelines. All the included individuals were briefed about the procedure, and signed informed consent was obtained. The demographic data of all subjects were recorded on a customized case history pro forma. Detailed oral examination of all the individuals was carried out using diagnostic instruments. Initially, the swab samples were obtained for the microbiological culture technique followed by incisional biopsy of the clinical diagnosed lesion for histopathological confirmation.

For microbiological culture

Initially, the patients were requested to rinse the mouth with distilled water to clear the debris followed by saline water. Sterile cotton swabs (HiMedia, PW1184, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India) with a wooden stick mounted on a blue-capped high-density polyethylene tube sized 150 mm × 12 mm were used to collect the samples from the buccal mucosa in healthy controls and from the lesional area in case of PMD and OSCC patients. The swab samples were positioned back in the same polyethylene tube and maintained at 40°C until streaking on Sabouraud dextrose agar (SDA) medium (HiMedia MH063, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India) and incubation at 37°C for 24–48 h.

Streaking was done using a sterile tool, such as a cotton swab or commonly an inoculation loop. The inoculation loop was first sterilized by passing it through a flame until red hot. When the loop has cooled, it was dipped into an inoculum such as swab specimen and then dragged across the surface of the agar back and forth in a zigzag motion until approximately 30% of the plate has been covered. The loop was then re-sterilized and the plate was turned to 90°. Starting in the previously streaked section, the loop was dragged through it two to three times continuing the zigzag pattern. The procedure was then repeated once more being cautious to not touch the previously streaked sectors. Each time, the loop gathers fewer and fewer bacteria until it gathers just single bacterial cells that can grow into a colony. Aseptic techniques were used to maintain microbiological cultures and to prevent contamination of the growth medium.[15]

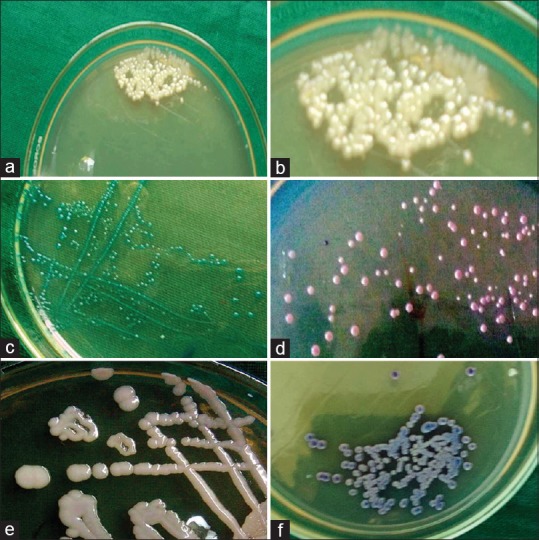

Later, only the creamy/white pasty smooth colonies representative of Candida organisms [Figure 1] were further inoculated on HiCrome Candida Differential HiVeg agar/CHROMagar (HiMedia MV1297A, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India) and incubated at 37°C for 24–48 h. The microbial-colored colonies representing various species of Candida organisms were interpreted for the color and specific colony characteristics as per the guidelines of HiMedia Laboratories.[16]

Figure 1.

The Sabouraud dextrose agar media showing white creamy pasty colonies representative of candidal species (a and b). The HiCROM Candida differential agar media showing green color colonies representative of Candida albicans (c). Purple color colonies representing Candida krusei (d). Creamy white colony representing Candida glabrata (e). and blue colour colonies representing Candida tropicalis (f)

Biopsy

The most suitable area for incisional biopsy was visually selected and soft tissue specimen was obtained. The tissue specimen was fixed in neutral-buffered formalin, processed as usual and embedded in paraffin wax. The 4–5 μ thick sections were primed and stained with hematoxylin and eosin stain for histopathological confirmation by means of a binocular research microscope (Motic BA400) ensuite with a 5 MP camera for photomicrography (Moticam 2500, USB2.0).

Statistical methods

All the data thus obtained were computed on Microsoft Excel Sheet. Statistical analysis of the data was carried out using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 17.0, Chicago, USA) using Chi-square test. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The distribution of the individuals in controls, PMD and OSCC has an age range of 17–63, 21–65 and 27–75 years, respectively, and the mean age ± standard deviation was 31.72 ± 12.76, 42.6 ± 5.09 and 49.27 ± 13.46 years, respectively. The distribution of the individuals among males and females in controls was 23 (92%) and 2 (8%), in PMD was 19 (63%) and 11 (37%) and in OSCC was 37 (92%) and 3 (8%), respectively.

On evaluation on SDA medium in controls, PMD and OSCC groups, Candida was present in 6 (24%), 13 (43%) and 33 (82%) and absent in 19 (76%), 17 (57%) and 7 (18%) individuals, respectively. On statistical analysis of intergroup comparison, an extremely significant difference (P = 0.000) was noted [Table 1]. Intragroup comparison also showed an extremely significant difference with P = 0.000 among both controls versus OSCC and PMD versus OSCC. However, controls versus PMD showed a nonsignificant, P = 0.1332 [Table 2].

Table 1.

Evaluation of Candida in Sabouraud dextrose agar media among the study groups

| Study groups | Candida in Sabouraud dextrose agar | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (%) | Absent (%) | ||

| Control | 6 (24) | 19 (76) | 0.000 (highly significant) |

| PMD | 13 (43) | 17 (57) | |

| OSCC | 33 (82) | 7 (18) | |

OSCC: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, PMDs: Potentially malignant disorders

Table 2.

Inter-group comparison of Candida in Sabouraud dextrose agar media

| Study groups | P |

|---|---|

| Control versus PMD | 0.1332 (nonsignificant) |

| Control versus OSCC | 0.000 (highly significant) |

| PMD versus OSCC | 0.000 (highly significant) |

PMD: Potentially malignant disorders, OSCC: Oral squamous cell carcinoma

On evaluation on CHROMagar media among controls, PMD and OSCC groups, Candida species was present in 5 (20%), 12 (40%) and 31 (77%) and absent in 20 (80%), 18 (60%) and 9 (23%) individuals, respectively. On statistical analysis, an extremely significant difference was noted (P = 0.000) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Evaluation of Candida in chrome agar media among study group

| Study group | Candida in chrome agar | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present (%) | Absent (%) | ||

| Control | 5 (20) | 20 (80) | 0.000 (highly significant) |

| PMD | 12 (40.0) | 18 (60.0) | |

| OSCC | 31 (77) | 9 (23) | |

OSCC: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, PMD: Potentially malignant disorders

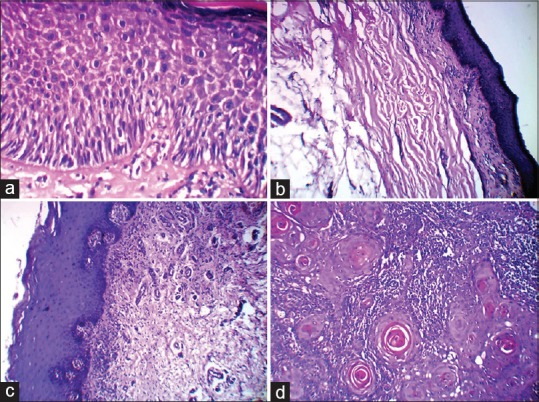

On speciation of Candida in CHROMagar among the controls, PMD and OSCC groups, C. albicans species was present in 4 (16%), 7 (23%) and 4 (10%), Candida krusei in 1 (4%), 5 (17%) and 10 (25%), Candida glabrata in 0, 0, and 6 (20%) and Candida tropicalis in 0, 0 and 2 (5%) cases, respectively [Figure 2]. However, only OSCC group showed a combination of species such as C. glabrata and C. krusei [Figure 3] was present in 1 (3%) case, C. tropicalis and C. krusei in was present 3 (7%) cases, C. tropicalis and C. glabrata was present in 1 (3%) case, C. albicans and C. tropicalis was present in 3 (7%) cases and C. krusei, C. glabrata with C. albicans was present in 1 (3%) case, respectively [Table 4 and Figure 3].

Figure 2.

The HiCROM Candida differential agar media showing a combination of purple white colonies representing Candida krusei and tropicalis (a and b). Blue and creamy white colony representing Candida tropicalis and glabrata (c). And green, blue and white colonies representing Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis and Candida glabrata (d)

Figure 3.

The photomicrograph showing hyperkeratinised mucosa with moderate epithelial dysplasia as in leukoplakia (a). Atrophic epithelium and dense collagen fiber bundles in oral submucous fibrosis (b). Basal cell degeneration and juxta-epithelial inflammatory infiltrate as in lichen planus (c). And epithelial cells in the form of islands, sheets, cords and strands with numerous keratin pearl formation as in well differentiated squamous cell carcinoma (d). (H&E, ×40)

Table 4.

Identification of various candidal species in CHROM agar among the study groups

| Candida species | Control (%) | PMD (%) | OSCC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. albicans | 4 (16) | 7 (23) | 4 (10) |

| C. krusei | 1 (4) | 5 (17) | 10 (25) |

| C. glabratta | Nil | Nil | 6 (20) |

| C. tropicalis | Nil | Nil | 2 (5) |

| C. krusei and C. tropicalis | Nil | Nil | 3 (7) |

| C. krusei and C. glabratta | Nil | Nil | 1 (3) |

| C. glabratta and C. tropicalis | Nil | Nil | 1 (3) |

| C. albicans and C. tropicalis | Nil | Nil | 3 (7) |

| C. albicans C. krusei, and C. glabratta | Nil | Nil | 1 (3) |

| Total | 5 (20) | 12 (40) | 31 (77) |

C. albicans: Candida albicans, C. krusei: Candida krusei, C. glabratta: Candida glabratta, C. tropicalis: Candida tropicalis, OSCC: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, PMD: Potentially malignant disorder

All the other forms of fungi, except Candida, were considered as contamination. On evaluation on SDA medium, contamination in the form of fungal molds was present in 10 (40%) in control, 8 (27%) in PMD and 6 (15%) in OSCC groups [Table 5].

Table 5.

Contaminations in control, potentially malignant disorders and oral squamous cell carcinoma groups

| Contamination | Control (%) | PMD (%) | OSCC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molds | 10 (40) | 8 (27) | 6 (15) |

OSCC: Oral squamous cell carcinoma, PMD: Potentially malignant disorder

DISCUSSION

Oral cancer is one of the most familiar forms of cancer in the Indian subcontinent. From the beginning of the twentieth century, frequency of oral cancer is known to be high in India.[17] Although arising de novo in many instances, a significant proportion of OSCC develops from PMDs such as leukoplakia, OSMF and lichen planus. The strong association between cancers of the oral cavity and pharynx with use of smoking, snuff and chewing tobacco is well established. Few investigators have also indicated that the presence of candidal infection increases the risk of malignant transformation in premalignant lesions.[12] Yeasts are common commensal organisms found in approximately 40% of individuals, the predominant species isolated being C. albicans. C. albicans predominantly affects oral mucosa.[18]

The possible association between Candida species and oral neoplasia was initially reported in the 1960s.[19,20] Candidal species may be capable of metabolizing ethanol to carcinogenic acetaldehyde and can thus progress oral and upper gastrointestinal tract cancer.[21] Later reports suggests link between the presence of C. albicans in the oral cavity and the development of OSCC. There are seven Candida species of major medical importance; C. albicans, C. tropicalis and C. glabrata are frequently isolated; while the sparingly isolated forms from the medical specimens are Candida parapsilosis, Candida stellatoidea, Candida guilliermondii, C. krusei and Candida pseudotropicalis.[13]

In the present study, the samples were collected using sterile swab. Contrastingly, Saigal et al.[1] used saliva for the culture technique instead of swab. Swab technique was simple to use; viable cells were isolated from the specific site, while saliva technique was not so.[22]

The collected swab sample was inoculated primarily on SDA medium followed by CHROMagar (a differential medium) for speciation. The same combination of culture media were also used by Nadeem et al.[23] and Odds and Bernaerts.[24] Contrastingly, Saigal et al.[1] used corn meal agar as primary culture media, followed by germ tube test, which identifies only C. albicans and Candida dubliniensis, and are unable to identify other Candida species.[1]

In the present study, the presence of Candida in SDA medium showed maximum specimens from OSCC followed by PMD and least in controls. Similarly, the results were demonstrated by various investigators such as Hongal et al.,[12] Saigal et al.,[1] Anila et al.[25] and Vučković et al.[7] Candida plays a fundamental role in the development of oral cancer, by means of endogenous nitrosamine, oligosaccharide and lectin-like component production.[1]

In the present study, the most prevalent Candida species identified under CHROMagar was C. albicans in control and PMD group, while OSCC group showed C. krusei. This was in consistent to the study by Gall et al.,[11] who have proved that there was a shift in distribution of Candida species with PMD undergoing malignant transformation from C. albicans to nonalbicans species such as C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei and C. parapsilosis.[25]

In the present study, all the other forms of fungi, except Candida, were considered as contamination in SDA medium. No such evidence of contamination was reported in other studies. This can be due to moist environment and improper sterilization technique followed.

CONCLUSION

However, further studies constituting larger sample size, various race and long-term follow-up studies need to be conceded to establish the exact role of Candida in carcinogenesis. Consequently, more focus should be placed on diagnosis and treatment of oral Candida infections, especially of nonalbicans species, which may cause systemic infections and are often resistant to commonly used antifungal agents such as fluconazole. The importance of antimycotic therapy before or associated with any other treatment and the importance of oral hygiene maintenance can be emphasized.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all the staff members of department of oral pathology and microbiology for their further support and guidance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saigal S, Bhargava A, Mehra SK, Dakwala F. Identification of Candida albicans by using different culture medias and its association in potentially malignant and malignant lesions. Contemp Clin Dent. 2011;2:188–93. doi: 10.4103/0976-237X.86454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhurgri Y, Bhurgri A, Usman A, Pervez S, Kayani N, Bashir I, et al. Epidemiological review of head and neck cancers in Karachi. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2006;7:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jaber MA. Oral epithelial dysplasia in non-users of tobacco and alcohol: An analysis of clinicopathologic characteristics and treatment outcome. J Oral Sci. 2010;52:13–21. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.52.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazarey V, Daftary D, Kale A, Warnakulasuriya S. Proceedings of the panel discussion on 'Standardized Reporting of Oral Epithelial Dysplasia'. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2007;11:86–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warnakulasuriya S, Johnson NW, van der Waal I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med. 2007;36:575–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2007.00582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Waal I. Potentially malignant disorders of the oral and oropharyngeal mucosa; terminology, classification and present concepts of management. Oral Oncol. 2009;45:317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vučković N, Bokor-Bratić M, Vučković D, Pićurić I. Presence of Candida albicans in potentially malignant oral mucosal lesions. Arch Oncol. 2004;12:51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reibel J. Prognosis of oral pre-malignant lesions: Significance of clinical, histopathological, and molecular biological characteristics. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 2003;14:47–62. doi: 10.1177/154411130301400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohd Bakri M, Mohd Hussaini H, Rachel Holmes A, David Cannon R, Mary Rich A. Revisiting the association between candidal infection and carcinoma, particularly oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Microbiol. 2010;2:5780–86. doi: 10.3402/jom.v2i0.5780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mehdipour M, Taghavi Zenouz A, Hekmatfar S, Adibpour M, Bahramian A, Khorshidi R. Prevalence of Candida species in erosive oral lichen planus. J Dent Res Dent Clin Dent Prospects. 2010;4:14–6. doi: 10.5681/joddd.2010.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gall F, Colella G, Di Onofrio V, Rossiello R, Angelillo IF, Liguori G. Candida spp. in oral cancer and oral precancerous lesions. New Microbiol. 2013;36:283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hongal BP, Kulkarni VV, Deshmukh RS, Joshi PS, Karande PP, Shroff AS. Prevalence of fungal hyphae in potentially malignant lesions and conditions-does its occurrence play a role in epithelial dysplasia? J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2015;19:10–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.157193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramirez-Garcia A, Rementeria A, Aguirre-Urizar JM, Moragues MD, Antoran A, Pellon A, et al. Candida albicans and cancer: Can this yeast induce cancer development or progression? Crit Rev Microbiol. 2016;42:181–93. doi: 10.3109/1040841X.2014.913004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rehani S, Rao NN, Rao A, Carnelio S, Ramakrishnaiah SH, Prakash PY. Spectrophotometric analysis of the expression of secreted aspartyl proteinases from Candida in leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Oral Sci. 2011;53:421–5. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.53.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jahanshahi G, Shirani S. Detection of Candida albicans in oral squamous cell carcinoma by fluorescence staining technique. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12:115–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.HiCrome Candida Differential Agar. Mumbai: HiMedia Laboratories Pvt., Ltd; 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Jun 29]. Available from: http://himedialabs.com/TD/M1297A.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ur, Rahaman SM, Ahmed Mujib B. Histopathological correlation of oral squamous cell carcinoma among younger and older patients. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:183–8. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.140734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams D, Lewis M. Pathogenesis and treatment of oral candidosis. Journal of Oral Microbiology. 2011;3:1–11. doi: 10.3402/jom.v3i0.5771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cawson RA. Chronic oral candidiasis and leukoplakia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1966;22:582–91. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(66)90161-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCullough M, Jaber M, Barrett AW, Bain L, Speight PM, Porter SR. Oral yeast carriage correlates with presence of oral epithelial dysplasia. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:391–3. doi: 10.1016/s1368-8375(01)00079-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deorukhkar SC, Saini S. Non albicans Candida species: Its isolation pattern, species distribution, virulence factors and antifungal susceptibility profile. Int J Med Sci Public Health. 2013;2:533–8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Singh A, Verma R, Murari A, Agrawal A. Oral candidiasis: An overview. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2014;18:S81–5. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.141325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nadeem SG, Hakim ST, Kazmi SU. Use of CHROMagar Candida for the presumptive identification of Candida species directly from clinical specimens in resource-limited settings. Libyan J Med. 2010;5:1–6. doi: 10.3402/ljm.v5i0.2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odds FC, Bernaerts R. CHROMagar Candida, a new differential isolation medium for presumptive identification of clinically important Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1923–9. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.8.1923-1929.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anila K, Hallikeri K, Shubhada C, Naikmasur V, Kulkarni R. Comparative study of Candida in oral submucous fibrosis and healthy individuals. Rev Odonto Ciência. 2011;26:71–6. [Google Scholar]