Abstract

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a complication of pregnancy that can be associated with neonatal complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Recently, probiotic use has been proposed for better control of glucose in GDM patients. The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of probiotic yoghurt compare with ordinary yoghurt on GDM women.

Methods

In this double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial, 84 pregnant women with GDM were randomly assigned into two groups of 42 recipients who underwent 300 g/day of probiotic yoghurt or placebo for 8 weeks. Blood glucose, HbA1c, and the outcome of pregnancy were compared between the two groups after the intervention.

Results

According to the findings of present trial no significant differences were observed in general characteristics between the two groups (p > 0.05). Both fasting and post prandial blood glucose as well as the level of HbA1c were decreased significantly in probiotic group (p < 0.05), although these changes are not statistically significant in the placebo group. The between group differences was significant after the 2 month intervention (p < 0.05). Neonates born of probiotic group mothers, have significantly lower weight and fewer macrosome neonates were born in this group compared with control group (p < 0.05). However, no difference was observed in other values of outcome.

Conclusions

Our study revealed that better control of blood glucose can be achieved by consumption of probiotic yoghurt in patients whose pregnancy is complicated by GDM, compared with placebo. Also incidence of macrosomia may be decreased by this regimen.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Probiotic, Yoghurt

Plain English summary

Present trial conducted to evaluate the effect of probiotic yoghurt containing L. acidophilus and B. lactis compare with ordinary yoghurt containing S. thermophilus and L. bulgaricus on GDM women. In this double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial, 84 pregnant women with GDM were randomly assigned into two groups of 42 recipients who underwent 300 g/day of probiotic yoghurt or placebo for 8 weeks. Biochemical parameters and the outcome of pregnancy were compared between the two groups after the intervention. The results of this study revealed that better control of blood glucose can be achieved by consumption of probiotic yoghurt in patients whose pregnancy is complicated by GDM, compared with placebo. Also incidence of macrosomia may be decreased by this regimen.

Background

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is known as a complication of pregnancy and is characterized by glucose intolerance which leads to adverse events such as macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycemia, neonatal hyper-bilirubinemia, preterm labor and increased risk of cesarean section [1, 2]. About 7% of all pregnancies in the United States are complicated by GDM, and its prevalence in Iran is approximately 6% of pregnancies [3, 4]. Recently, various complementary therapies have been considered for controlling blood glucose. Probiotics are microorganisms which can produce a microbial balance in the intestine and have a positive effect on the host [5–8]. Some of the mostly documented health benefits for probiotics include effectiveness against diarrhea, improvement of lactose metabolism, immunomodulation, as well as anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic, anti-diabetic, hypo-cholesterolemic, and hypotensive characteristics [6, 9–11]. In addition to their impact on gastrointestinal disorders, the effect of probiotics on the improvement of blood glucose and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and GDM has been reported [12–15]. It has been also reported that probiotics reduce blood glucose and improve insulin resistance in diabetic rats and humans [11, 16]. Despite of the importance of GDM and its impacts on maternal and neonatal outcomes, few studies have evaluated the probiotics effect on improving glucose intolerance and insulin resistance as well as the outcomes of pregnancies complicated by GDM. Considering the potential of probiotic bacteria, the aim of the present trial was to investigate the effects of probiotic yoghurt containing L. acidophilus and B. lactis consumption on the glycemic parameters including FBG, post prandial BS, and HbA1c and the outcome of pregnancy including gestational age, weight, length, head circumference, macrosomia, and admission to NICU in GDM patients.

Methods

Subjects

In this double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial, 84 patients with the diagnosis of GDM were recruited consecutively from the outpatient obstetrics clinic of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Inclusion criteria was as the following: patients referring to Tabriz Al-Zahra and Talegani high-risk outpatient clinic with the diagnosis of GDM, patients in their second trimester of pregnancy and patients diagnosed by oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 24th and 28th weeks of pregnancy. Exclusion criteria was presence of other physical or psychological problems, presence of already-known fetal anomalous and not to consent to involve in the study.

Sample size

The sample size for the study was calculated on the basis of the results (mean ± SD) for FBG as reported by Ejtahed et al. [12] with a confidence level of 95% and a power of 80%. Taking into account the probable dropout of patients during the intervention course as well as those who may not adhere to the study protocol, 42 patients with GDM were recruited for each group.

Study design

Subjects were randomly assigned to the probiotic group (n = 20) receiving 300 mg/day of probiotic yoghurt (contained 106 Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis) or placebo (n = 20) group receiving 300 mg/day of ordinary yoghurt for 8 weeks, using a block randomization procedure with stratified subjects in each block based on age and week of pregnancy. All cans were coded by the company (Pegah Dairy Industries Company) and either the researcher or the patients were unaware of the contents. One week before the beginning of the trial, all patients refrained from eating yoghurt or any other fermented foods. All patients were asked, throughout the 8-week trial, to maintain their usual dietary habits and lifestyle and to avoid consuming any yoghurt other than that provided to them by the researchers and any other fermented foods. The patients were instructed to keep the yoghurt under refrigeration and to avoid any changes in medication, if possible.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences (Iran) and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before inclusion in the study.

Clinical and biochemical measurements

At baseline, all participants were examined by an obstetrician and the parameters including age, history of pregnancies, weight, height, body mass index, smoking, and blood pressure were measured. Ten ml of venous whole blood was obtained from each participant both before and after intervention after 12-h overnight fasting. The primary outcomes were the level of fasting blood glucose (FBG), post prandial blood glucose (BG), and HbA1c. Additionally, the secondary outcomes were the neonatal outcomes including weight, length, head circumference, presence of macrosomia and need for NICU admission that were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 18.0 (SPSS, Inc., USA). Normality of variables distribution was evaluated using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Variables not normally distributed were analyzed using nonparametric tests. Categorical and normally distributed quantitative variables were displayed as numbers (percentages) and mean ± SD, respectively. Non-normally distributed quantitative variables were presented as median (interquartile range). Between groups comparisons were made by χ2, independent-sample t test, and paired sample t test, as appropriate. Correlations between variables were analyzed by Pearson correlation test or Spearman rank correlation analysis. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of patients

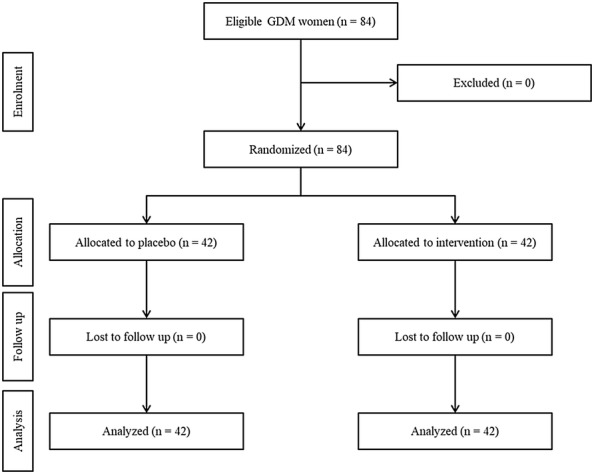

As revealed in the study flow diagram (Fig. 1), 84 pregnant women [probiotic (n = 42) and placebo (n = 42)] completed the trial. General characteristics of study subjects are showed in Table 1. The mean ± SD age of all participants was 31.6 ± 5.7 years. The mean ± SD weight, height and body mass index were 79.2 ± 11.5 kg, 161.8 ± 5.1 cm and 30.7 ± 4.5 kg/m2 respectively. The mean ± SD systolic and diastolic blood pressures were 111.4 ± 6.6 and 71.9 ± 5.5 mmHg respectively. As shown, No significant differences were observed in general characteristics between two groups.

Fig. 1.

Summary of patient flow diagram

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | Probiotic yoghurt group (n = 42) | Conventional yoghurt group (n = 42) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 31.64 ± 5.97 | 31.61 ± 5.49 | 0.98 |

| History of GDM (n (%)) | 0 | 4(9.5) | 0.11 |

| Smoking (n (%)) | 0 | 4(9.5) | 0.11 |

| Weight (kg) (mean ± SD) | 79.5 ± 17.31 | 73.73 ± 17.74 | 0.13 |

| Height (cm) (mean ± SD) | 161.32 ± 4.98 | 161 ± 4.64 | 0.76 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD) | 31.67 ± 5.44 | 29.67 ± 3.03 | 0.06 |

| SBP (mmHg) (mean ± SD) | 111.66 ± 4.89 | 111.05 ± 63 | 0.66 |

| DBP (mmHg) (mean ± SD) | 71.19 ± 4.52 | 72.63 ± 6.44 | 0.24 |

| Activity | |||

| Light (n (%)) | 11 (26.2) | 5 (11.9) | 0.09 |

| Heavy (n (%)) | 31 (73.8) | 37 (88.1) | |

| FBG (mg/dl) | 97.1 ± 9.4 | 96.4 ± 10.4 | 0.24 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 5.65 ± 0.67 | 5.86 ± 1.12 | 0.48 |

GDM gestational diabetes mellitus, SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FBG fasting blood glucose, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin

* p values indicate comparison between groups (χ2 or independent-sample t test, as appropriate)

Primary outcomes

Table 2 evaluates the findings related to the level of blood glucose. As shown, both fasting and post prandial blood glucose as well as the level of HbA1c is decreased significantly in probiotic group, although these changes are not statistically significant in the placebo group. Moreover the between group differences were statistically different after 2 weeks intervention.

Table 2.

Level of blood glucose and glycemic response

| Variable | Probiotic yoghurt group (n = 42) | Conventional yoghurt group (n = 42) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| FBG (mg/dl) | |||

| Before | 97.1 ± 9.4 | 96.4 ± 10.4 | 0.241 |

| After | 94 ± 8.5 | 97.6 ± 14.3 | 0.048 |

| p value* | 0.013 | 0.36 | |

| Post prandial BS (mg/dl) | |||

| Before | 144.3 ± 26.8 | 136.8 ± 23.7 | 0.452 |

| After | 123.9 ± 16.2 | 136.8 ± 18.7 | 0.002 |

| p value* | < 0.001 | 0.95 | |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | |||

| Before | 5.65 ± 0.67 | 5.86 ± 1.12 | 0.488 |

| After | 5.48 ± 0.62 | 5.76 ± 1.02 | 0.025 |

| p value* | < 0.001 | 0.092 | |

FBG fasting blood glucose, BG blood glucose, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin

For baseline between group comparisons, p-values are based on independent t-test

For after intervention between group comparisons, p-values and confidence intervals are based on analysis of covariance

* For within group comparisons, p values and confidence intervals are based on paired t-test

Secondary outcomes

Table 3 evaluates differences in neonatal outcomes between the two groups. As shown, neonates born to probiotic group mothers have significantly lower weight and fewer macrosome neonates were born in this group. However, no difference was observed in other values of outcome.

Table 3.

Characteristics of neonates

| Characteristics | Probiotic yoghurt group (n = 42) | Conventional yoghurt group (n = 42) | p value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational age (weeks)* | 37.7 ± 1.9 | 38.1 ± 1.3 | 0.25 |

| Weight (g)* | 3105.7 ± 533.8 | 3435 ± 473.5 | 0.004 |

| Length (cm)* | 49.8 ± 3.5 | 50.5 ± 2.9 | 0.61 |

| Head circumference (cm)* | 36 ± 2.3 | 36.2 ± 2 | 0.76 |

| Macrosomia** | 2 (4.8) | 8 (19) | 0.04 |

| Admission to NICU** | 2 (4.8) | 3 (7.1) | 0.64 |

NICU, Neonatal intensive care unit

* Data are expressed as mean (SD) and p value based on independent t-test

** Frequency (percent) is reported and p value based on Chi-squared test

Discussion

Management of GDM without any side effects by natural food is a challenge for medical nutrition therapy of GDM. The present research is the first study evaluated the effect of consumption of probiotic yoghurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis on glycemic response the outcome of pregnancy in GDM patients. According to the findings of present study, we found that using probiotic yoghurt causes a significant improvement in blood glucose levels and reduce risk of macrosomia.

Throughout pregnancy the gut microbiota undergoes significant changes. From the first (T1) to the third trimester (T3), the species richness of the gut microbiome decreases [17], although this has not been observed in all studies [18]. There is an increase in Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria phyla and a reduction in beneficial bacterial species Roseburia intestinalis and Faecalibacterium prausnitzii [17, 19]. These changes in gut microbial composition cause inflammation and correlate with increases in fat mass, blood glucose, insulin resistance and circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines in the expectant mother [20]. This “diabetic-like” state observed during the later stages of all healthy pregnancies is thought to maximize nutrient provision to the developing fetus [21]. However, increased insulin resistance combined with an inability to secrete the additional insulin required to maintain glucose homeostasis can result in the development of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) in the mother and macrosomia in the baby. The fasting hyperglycemia in women with GDM is associated with increased short-term and long-term complications in neonates [22]. Safe and inexpensive interventions for prevention and treatment of GDM are needed. Considering that certain microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract can produce a positive effect on host metabolism, probiotic supplements can help maintain bacterial diversity and homeostasis in people with metabolic disorders [22, 23]. Experiments involving human intubation and sampling of probiotics from the cecum showed that probiotics, when given in fermented milk, survive to the extent of 23.5% ± 10.4% of the administered dose. With the use of known probiotic species and strains, it was determined that the delivery of Lactobacillus and bifidobacteria to the cecum was ≈ 30% and 10% of the administered dose, respectively [24]. In a research conducted by Homayouni et al. in 2012, the made it clear that foods are better carriers for probiotics than supplements [25]. Considering the survivability of Lactobacillus and bifidobacteria in human gastric trac and by knowing that fermented dietary products are better vehicle for probiotics we have evaluated the efficacy of yoghurt containing L. acidophilus and B. lactis in patients whose pregnancy is complicated by GDM.

Several studies showed benefits of probiotic use for improving blood glucose control in patients with GDM and T2DM (type 2 diabetes mellitus) [9, 26–30]; however, the efficacy of probiotics on pregnancy outcomes in GDM patients was not studied before. The findings of present research indicated that consumption of probiotic yoghurt containing L. acidophilus and B. lactis for 2 months could improve glycemic control in women with GDM.

Asemi et al. [29] evaluated the effects of daily consumption of probiotic yoghurt on insulin resistance and levels of insulin in the serum of pregnant women in the third trimester of gestation. The probiotic yoghurt used in this study was enriched with a probiotic culture of L. acidophilus LA5 and Bifidobacterium animalis BB12 with at least 107 Colony Forming Unities. Daily consumption of probiotic yoghurt for 9 weeks was effective in maintaining normal serum insulin levels in pregnant women and thus contributing to prevent the development of insulin resistance, which usually develops during the last trimester in pregnant women. The study demonstrated an improvement in glycemic control during the last trimester of pregnancy, extending in the postpartum period for 12 months.

In the study conducted by Badehnoosh et al. [31] on 60 subjects with GDM they found that consumption of probiotic capsule containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei and Bifidobacterium bifidum (2 × 109 CFU/g each) for 6 weeks had beneficial effects on glycemic response, and serum inflammatory and oxidative stress biomarkers.

Dolatkhah et al. [27] conducted a study with women between 18 and 45 years of age with GDM between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy. The study was based on the daily consumption of probiotic capsules containing four bacterial strains (4 × 109 CFU) in lyophilized culture, or placebo. The probiotic supplement appeared to improve glucose metabolism and weight gain among pregnant women with GDM.

Karamali et al. [28] analyzed the effects of probiotic supplementation on glycemic control and the lipid profiles over a period of 6 weeks. This study included 60 pregnant women with GDM, from 24 to 28 weeks of pregnancy. The probiotic group took a daily capsule containing 109 CFU/g L. acidophilus, L. casei, and Bifidobacterium bifidum. After 6 weeks of treatment with probiotics, glycaemia, triglycerides, and VLDL cholesterol concentration decreased compared with the placebo group. In another 12-week study in pregnant women, probiotic supplementation containing the same strains, concluded that the probiotics had a positive effect on the metabolism of insulin, triglycerides, biomarkers of inflammation, and oxidative stress [32].

Recently, Jafarnejad et al. [33] analyzed the effects of a mixture of probiotics (VSL#3) on the glycemic state and inflammatory markers in 72 GDM patients through a double blind and randomized controlled clinical trial. The study groups consumed either a probiotic or placebo capsules twice a day for 8 weeks. The study concluded that for women with GDM, a probiotic supplementation can modulate some of the inflammatory markers and improve glycemic control.

In the study of Lindsay et al. [34], 149 pregnant women older than 18 years, before 34 weeks of pregnancy, were divided between probiotic and placebo groups and the aim of their study was to investigate the effects of probiotic capsule contained 100 mg Lactobacillus salivarius on metabolic parameters and pregnancy outcomes in pregnant women with GDM. No significant differences were observed between the groups concerning the post-intervention fasting blood glucose and birth weight. In addition, Lindsay et al. [35] investigated the effects of probiotic supplementation on fasting maternal glycaemia in obese pregnant women with a Body Mass Index (BMI) of > 30 kg/m2 between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy. A probiotic or placebo capsule was ingested daily, each probiotic capsule containing 100 mg of lyophilised Lactobacillus salivarius. The study showed no effect of probiotic intervention during 4 weeks on glycaemia. Their findings were different maybe because of the use of other probiotic strain and/or different intervention duration.

In general, probiotics can improve glycemic control and neonatal outcomes of patients with GDM [36]; however, the mechanisms whereby probiotics alter glucose homeostasis are not completely understood. One proposed method is by the production of short chain fatty acids (SCFAs), generated as a by-product of bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers. SCFAs act as an energy source for intestinal cells and have been found to regulate the production of hormones affecting energy intake and expenditure such as leptin and grehlin [37]. The binding of SCFAs to G protein-coupled receptors GPR41 and GPR43 increases the intestinal expression of Peptide YY and Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) hormones which act to reduce appetite by slowing intestinal transit time and increasing insulin sensitivity [19]. Another hypothesized mechanism of SCFA action includes reducing gastrointestinal permeability by up-regulating transcription of tight junction proteins, enhancing production of Glucagon-like peptide-2 (GLP-2) which promotes crypt cell proliferation, and reducing inflammation in colonic epithelial cells by increasing PPAR-gamma activation [38]. Maintenance of the integrity of the gut barrier minimizes the concentration of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) in circulation. LPS is a structural component of gram negative bacterial cell walls, which induces an immune-cell response upon absorption into the human bloodstream, stimulating pro-inflammatory cytokine production and the onset of insulin resistance and hyperglycemia [39].

Considering the beneficial effects of probiotic supplementation in present research and the less amount of studies in this field, further research are needed to investigate the beneficial effects of several probiotic strains in different dose and duration on biochemical parameters and pregnancy outcomes in GDM patients.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study revealed better control of blood glucose is achieved by consumption of probiotic yoghurt containing L. acidophilus and B. lactis in patients, whose pregnancy is complicated by GDM, compare with placebo. The positive effects of probiotics on glycemic control could be translated into favorable effect on decreasing the incidence of macrosomia.

The limitation of this study was the small sample size. A plan for more subjects, longer duration in the long term, and evaluating the effect of other probiotic strains is currently underway.

Acknowledgements

The results of this article are derived from the MD (specialty degree in Internal Medicine) thesis of Metanat Mosen registered in the Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran. The authors wish to thank the Women’s Reproductive Health Research Center of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences for financial support. They also thank all the subjects for their participation in this research.

Abbreviations

- GDM

gestational diabetes mellitus

- HbA1c

hemoglobin A1c

- OGGT

oral glucose tolerance test

- FBG

fasting blood glucose

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- CFU

colony-forming unit

- BMI

body mass index

- SCFA

short chain fatty acid

- GLP

glucagon-like peptide

- PPAR

peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors

- LPS

lipopolysaccharides

Authors’ contributions

AHR, FSE, and MM conceived the idea, participated in study design, performed the experiments, conducted the biochemical analysis, and supervised the entire work. AHR and LK conducted the statistical analysis and helped with drafting of manuscript. FA and AT participated in the performance of the experiments. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data are all contained within the paper.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethical Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study (No. IRCT20121224011862N2).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Aziz Homayouni Rad, Email: homayounia@tbzmed.ac.ir.

Leila Khalili, Phone: 0098-9016114517, Email: leylakhalili1990@gmail.com, Email: khalilil@tbzmed.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Group HSCR Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):1991–2002. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0707943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai P-JS, Roberson E, Dye T. Gestational diabetes and macrosomia by race/ethnicity in Hawaii. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6(1):395. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harlev A, Wiznitzer A. New insights on glucose pathophysiology in gestational diabetes and insulin resistance. Curr Diab Rep. 2010;10(3):242–247. doi: 10.1007/s11892-010-0113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Almasi S, Salehiniya H. The prevalence of gestational diabetes mellitus in Iran (1993–2013): a systematic review. J Isfahan Med Sch. 2014;32(299):1396–1412. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homayouni A. Letter to the editor. Food Chem. 2009;114:1073. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.10.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bastani P, Akbarzadeh F, Homayouni A, Javadi M, Khalili L. Health benefits of probiotic consumption. Microbes in food and health. Berlin: Springer; 2016. pp. 163–183. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rad AH, Mehrabany EV, Alipoor B, Mehrabany LV, Javadi M. Do probiotics act more efficiently in foods than in supplements? Nutrition. 2012;28(7):733–736. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vaghef-Mehrabany E, Homayouni-Rad A, Alipour B, Sharif S-K, Vaghef-Mehrabany L, Alipour-Ajiry S. Effects of probiotic supplementation on oxidative stress indices in women with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized double-blind clinical trial. J Am Coll Nutr. 2016;35(4):291–299. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2014.959208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khalili L, Alipour B, Asghari Jafar-Abadi M, Faraji I, Hassanalilou T, Mesgari Abbasi M, et al. The effects of Lactobacillus casei on glycemic response, serum Sirtuin1 and Fetuin-A levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Iran Biomed J. 2016;23(1):68–77. doi: 10.29252/.23.1.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maleki Davood, Homayouni Aziz, Khalili Leila, Golkhalkhali Babak. Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Synbiotics. 2016. Probiotics in Cancer Prevention, Updating the Evidence; pp. 781–791. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalili L, Alipour B, Jafarabadi MA, Hassanalilou T, Abbasi MM, Faraji I. Probiotic assisted weight management as a main factor for glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019;11(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s13098-019-0400-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 12.Ejtahed H, Mohtadi-Nia J, Homayouni-Rad A, Niafar M, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Mofid V, et al. Effect of probiotic yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium lactis on lipid profile in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Dairy Sci. 2011;94(7):3288–3294. doi: 10.3168/jds.2010-4128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Q, Wu Y, Fei X. Effect of probiotics on glucose metabolism in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Medicina. 2015;52(1):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.medici.2015.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yan Q, Li X, Feng B. The efficacy and safety of probiotics intervention in preventing conversion of impaired glucose tolerance to diabetes: study protocol for a randomized, double-blinded, placebo controlled trial of the Probiotics Prevention Diabetes Programme (PPDP) BMC Endocr Disord. 2015;15(1):74. doi: 10.1186/s12902-015-0071-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ejtahed HS, Mohtadi Nia J, Homayouni Rad A, Niafar M, Asghari Jafarabadi M, Mofid V. The effects of probiotic and conventional yoghurt on diabetes markers and insulin resistance in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Iran J Endocrinol Metab. 2011;13(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yadav H, Jain S, Sinha P. Antidiabetic effect of probiotic dahi containing Lactobacillus acidophilus and Lactobacillus casei in high fructose fed rats. Nutrition. 2007;23(1):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Bäckhed HK, et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell. 2012;150(3):470–480. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiGiulio DB, Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Costello EK, Lyell DJ, Robaczewska A, et al. Temporal and spatial variation of the human microbiota during pregnancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112(35):11060–11065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1502875112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Food, immunity, and the microbiome. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(6):1107–1119. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gohir W, Whelan FJ, Surette MG, Moore C, Schertzer JD, Sloboda DM. Pregnancy-related changes in the maternal gut microbiota are dependent upon the mother’s periconceptional diet. Gut Microbes. 2015;6(5):310–320. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2015.1086056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang Q, Würtz P, Auro K, Mäkinen V-P, Kangas AJ, Soininen P, et al. Metabolic profiling of pregnancy: cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):205. doi: 10.1186/s12916-016-0733-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LCM, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(3):859–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregor MF, Hotamisligil GS. Inflammatory mechanisms in obesity. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:415–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bezkorovainy A. Probiotics: determinants of survival and growth in the gut. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;73(2):399s–405s. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/73.2.399s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rad AH, Mehrabany EV, Alipoor B, Mehrabany LV, Javadi M. Do probiotics act more efficiently in foods than in supplements? Nutrition. 2012;28(7/8):733. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ejtahed HS, Mohtadi-Nia J, Homayouni-Rad A, Niafar M, Asghari-Jafarabadi M, Mofid V. Probiotic yogurt improves antioxidant status in type 2 diabetic patients. Nutrition. 2012;28(5):539–543. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dolatkhah N, Hajifaraji M, Abbasalizadeh F, Aghamohammadzadeh N, Mehrabi Y, Abbasi MM. Is there a value for probiotic supplements in gestational diabetes mellitus? A randomized clinical trial. J Health Popul Nutr. 2015;33(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s41043-015-0034-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karamali M, Dadkhah F, Sadrkhanlou M, Jamilian M, Ahmadi S, Tajabadi-Ebrahimi M, et al. Effects of probiotic supplementation on glycaemic control and lipid profiles in gestational diabetes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diabetes Metab. 2016;42(4):234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.diabet.2016.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Asemi Z, Samimi M, Tabassi Z, Rad MN, Foroushani AR, Khorammian H, et al. Effect of daily consumption of probiotic yoghurt on insulin resistance in pregnant women: a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(1):71. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Li X, Han H, Cui H, Peng M, Wang G, et al. Effect of probiotics on metabolic profiles in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Medicine. 2016;95(26):e4088. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000004088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Badehnoosh B, Karamali M, Zarrati M, Jamilian M, Bahmani F, Tajabadi-Ebrahimi M, et al. The effects of probiotic supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation, oxidative stress and pregnancy outcomes in gestational diabetes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31(9):1128–1136. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1310193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jamilian M, Vahedpoor Z, Dizaji SH. Effects of probiotic supplementation on metabolic status in pregnant women: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Iran Med. 2016;19(10):687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jafarnejad S, Saremi S, Jafarnejad F, Arab A. Effects of a multispecies probiotic mixture on glycemic control and inflammatory status in women with gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Nutr Metab. 2016;2016:5190846. doi: 10.1155/2016/5190846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindsay KL, Kennelly M, Culliton M, Smith T, Maguire OC, Shanahan F, et al. Probiotics in obese pregnancy do not reduce maternal fasting glucose: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial (Probiotics in Pregnancy Study) Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(6):1432–1439. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.113.079723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsay KL, Brennan L, Kennelly MA, Maguire OC, Smith T, Curran S, et al. Impact of probiotics in women with gestational diabetes mellitus on metabolic health: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(4):496.e1–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rad AH, Abbasalizadeh S, Vazifekhah S, Abbasalizadeh F, Hassanalilou T, Bastani P, et al. The future of diabetes management by healthy probiotic microorganisms. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2017;13(6):582–589. doi: 10.2174/1573399812666161014112515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kellow NJ, Coughlan MT, Reid CM. Metabolic benefits of dietary prebiotics in human subjects: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Br J Nutr. 2014;111(7):1147–1161. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513003607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jayashree B, Bibin Y, Prabhu D, Shanthirani C, Gokulakrishnan K, Lakshmi B, et al. Increased circulatory levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and zonulin signify novel biomarkers of proinflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Mol Cell Biochem. 2014;388(1–2):203–210. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761–1772. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are all contained within the paper.