Abstract

Background/Aim:

The aim of the study was to identify the recurrence rate of Helicobacter pylori after successful eradication in an endemic area and investigate baseline and clinical factors related to the recurrence.

Patients and Methods:

H. pylori infected patients from a screening cohort of National Cancer Center between 2007 and 2012 were enrolled in the study. A total of 647 patients who were confirmed to be successfully eradicated were annually followed by screening endoscopy and rapid urease test. Median follow-up interval was 42 months. Annual recurrence rate of H. pylori was identified. Demographics, clinical factors, and endoscopic findings were compared between H. pylori recurrence group and persistently eradicated group (control group).

Results:

H. pylori recurrence was observed in 21 (3.25%) patients. Its annual recurrence rate was 0.91% (1.1% in males and 0.59% in females). Mean age was higher in the recurrence group than that in the control group (55.9 vs 50.7, P = 0.006). Median follow-up was shorter in the recurrence group than that in the control group (34 vs. 42.5 months, P = 0.031). In multivariate analysis, OR for H. pylori recurrence was 1.08 per each increase in age (P = 0.012). Adjusted ORs for H. pylori recurrence were 0.20 (95% CI: 0.06–0.69) and 0.25 (95% CI: 0.08–0.76) in age groups of 50–59 years and less than 50 years, respectively, compared to the group aged 60 years or older.

Conclusion:

H. pylori recurrence rate in Korea is very low after successful eradication. Advanced age is at increased risk for H. pylori recurrence. Thus, H. pylori treatment for patients who are under 60 years of age is more effective, leading to maintenance of successful eradication status.

Keywords: Eradication, Helicobacter pylori, recurrence

INTRODUCTION

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is known as a risk factor for gastric cancer. It was classified as a type I carcinogen by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) in 1994.[1] Long-term H. pylori infection can lead to premalignant histological changes such as atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia.[2] Although the incidence of gastric cancer has decreased substantially in the Western world, it is still the fourth most common cancer and the second leading cause of mortality due to cancers worldwide.[3] South Korea has the highest incidence rate of gastric cancer.[3] Nationwide biennial gastric cancer screening for individuals aged 40 years or older has been conducted in South Korea since 1999.[4] Recently, there has been an increased concern about early eradication of H. pylori to prevent gastric cancer.[5]H. pylori infection is also a risk factor for peptic ulcer diseases (PUD) and gastric MALT lymphoma. The updated American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guideline strongly recommends H. pylori eradication for patients with PUD, a history of PUD, low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, or a history of endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer.[6] The success rate of eradication therapy in South Korea has been reported to be around 80% recently.[7,8] However, a negative result on follow-up test after H. pylori treatment does not guarantee subsequent persistent eradication status in the future. To prevent progression of premalignant histological changes and recurrent peptic ulcer diseases, it is important to maintain H. pylori eradication status after successful treatment.

After successful eradication, H. pylori may be detected again. This is usually considered a recurrence. However, recurrence refers to the recrudescence of the original strain of H. pylori that remains suppressed and undetectable, whereas reinfection refers to infection by a new strain of H. pylori.[9] Reported rate of annual recurrence, sometimes including reinfection, ranges from 2.0% to 9.1% in Korean studies.[10,11,12,13,14] The rate of recurrence generally varies depending on the country, race, research period, research method, and so on. Reviewing recurrence rate can help us assess the relevance of treatment and predict future development of H. pylori-related diseases. Due to socioeconomic development and improved hygiene in South Korea, the prevalence of H. pylori infection has gradually decreased, although it is still over 50%.[15] Types of eradication regimens and bacterial resistance may also affect the recurrence rate. Along with these various changes, the recurrence rate of H. pylori in South Korea is also changing. The aim of this study was to determine the recurrence rate of H. pylori after successful eradication in an endemic area and to identify baseline and clinical factors related to the recurrence.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study design and patients

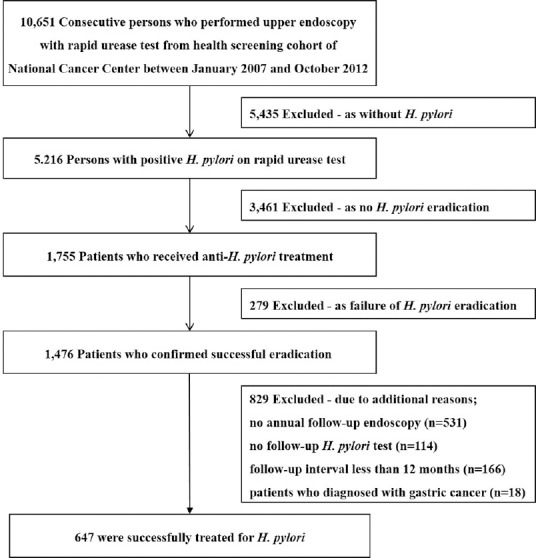

Consecutive persons who participated in the voluntary health screening program at National Cancer Center, South Korea, between January 2007 and December 2012 were considered. The National Cancer Center has established a screening cohort for health checkups since 2001. Inclusion criteria were: screening cohort participants who provided informed consent screening cohort, those who underwent annual gastric cancer screening with upper endoscopy and H. pylori test, and those who were suitable as study subjects based on appropriate physical examination and questionnaire. Among 10,651 persons who met the inclusion criteria, 5,216 case persons had positive H. pylori test results during the study period, and 1,755 persons received anti-H. pylori treatment. Among them, 1,476 cases for which H. pylori eradication was successful were eligible for the studyFigure 1. Of them, 531 subjects were excluded as they did not undergo annual follow-up endoscopy after successful eradication. We additionally excluded subjects because of the following reasons: follow-up endoscopy with interval less than 12 months (n = 166), those who did not undergo H. pylori test on follow-up endoscopy (n = 114), and those who were diagnosed with primary or metastatic gastric cancer (n = 18). Finally, 647 subjects were included in the analysis. Information relating to patients' endoscopic findings and their baseline characteristics was obtained via questionnaires and review of medical records. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Cancer Center (NCCNCS13739).

Figure 1.

Study flow of screening cohort. We selected 647 subjects who were successfully treated for H. pylori

Endoscopy and H. pylori eradication

All participants underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (GIF-H260, Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) after fasting overnight. Pharyngeal anesthesia with 4% xylocaine spray was routinely performed and intravenous midazolam was administered for conscious sedation. During each endoscopic examination, a rapid urease test (Pronto Dry; Medical Instruments, Solothurn, Switzerland) was routinely performed via a specimen obtained from the greater curvature of the corpus. H. pylori-positive subjects, who were clinically indicated for H. pylori eradication or according to patients' desire, received a 7-day triple therapy with omeprazole 20 mg twice daily, amoxicillin 1000 mg twice daily, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily as the first-line anti-H. pylori treatment. Quadruple regimen was provided as a second line therapy for patients who were considered as having triple therapy failure. Assessment of successful H. pylori treatment was performed at least 4–5 weeks after the end of the eradication treatment, using a histological examination, a rapid urease test, or a C13urea breath test. Patients were instructed not to take antacids during the period. Those with all negative results from available tests were regarded as successfully eradicated persons. H. pylori recurrence was defined when H. pylori infection was confirmed in a rapid urease test on follow-up screening endoscopy performed at intervals of 12 months or more after a confirmed successful H. pylori eradiation. The period was defined as follow-up interval. For subjects who did not have a recurrence, follow-up interval was calculated as the period from the time of successful eradication to the last follow-up endoscopy within the study period.

Statistical analysis

Annual recurrence rate of H. pylori in the study population was calculated by dividing the total number of re-infected subjects by the total number of patient year observed (%), and Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was performed. Baseline characteristics and clinical findings were compared between subjects with H. pylori recurrence (“case group”) and those who showed persistently successful eradication status (“control group”). Pearson's Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables (sex, regimen of eradication, smoking and drinking status, comorbidity, medication history, and endoscopic findings) whereas independent sample t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare continuous variables (age, follow-up period, and anthropometric indices). Multivariate logistic regression analyses using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were performed considering significant factors with P values less than 0.05 in the univariate analysis and possible confounding factors. All P values are two-sided. Statistical significance was considered when P value was less than 0.05. SPSS Statistics 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

Baseline demographic data

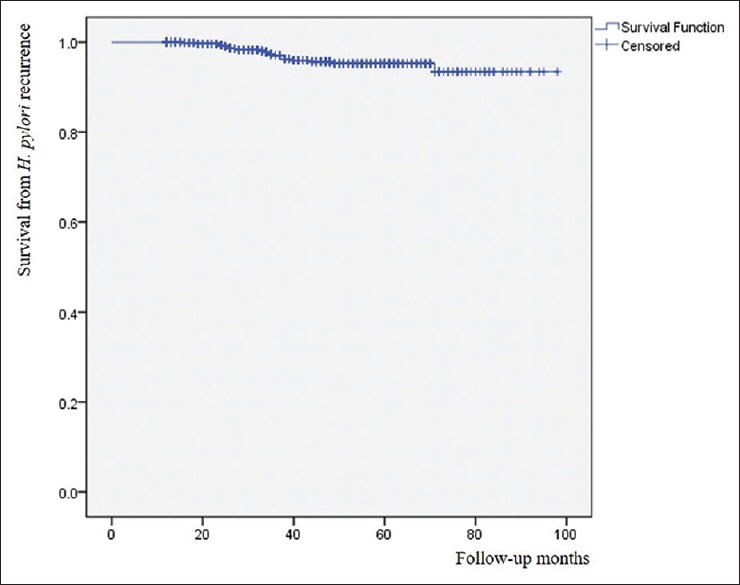

The mean age of the study population was 50.9 ± 8.5 years, and 62% were male. Median follow-up interval was 42 months (range: 12-98 months). H. pylori recurrence was observed in 21 (3.25%) of 647 enrolled subjects, whereas the remaining 626 subjects showed persistent eradication status. Annual recurrence rate was 0.91% (1.1% in males and 0.59% in females). Kaplan–Meier survival curve was shown in Figure 2. Results of comparison of baseline demographics and clinical findings between patients with H. pylori recurrence and those with persistent eradication are shown in Table 1. Mean age was significantly higher in H. pylori recurrence group than that in the control group (55.9 vs 50.7 years, P = 0.006). Median follow-up was significantly lower in H. pylori recurrence group (34 months, range: 16–71 months) than that in control group (42.5 months, range: 12–98 months) (P = 0.031). Among the study population, 88 (13.6%) subjects received second line therapy. The number of subjects receiving second line therapy was not significantly different between the recurrence group and the control group. There was no significant difference in anthropometric indices, smoking status, drinking status, comorbidity, medication history, or endoscopic findings between the two groups.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for H. pylori recurrence

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Variables | Total (n=647) | Control group (n=626) | Recurrence group (n=21) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean±SD | 50.9±8.5 | 50.7±8.5 | 55.9±8.4 | 0.006 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 401 (62.0) | 385 (61.5) | 16 (76.2) | 0.173 |

| Follow-up (mo), mean±SD | 42.7±19.2 | 43.0±19.3 | 33.6±11.9 | 0.002 |

| Second line regimen, n (%) | 88 (13.6) | 86 (13.7) | 2 (9.5) | 0.755 |

| Height (cm), mean±SD | 165.6±8.1 | 165.5±8.0 | 168.1±8.5 | 0.139 |

| Weight (kg), mean±SD | 66.6±11.3 | 66.5±11.2 | 70.0±14.1 | 0.172 |

| Current smoking, n (%) | 169 (26.1) | 164 (26.2) | 5 (23.8) | 0.806 |

| Current drinking, n (%) | 427 (66.0) | 412 (65.8) | 15 (71.4) | 0.593 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 115 (17.8) | 111 (17.7) | 4 (19.0) | 0.777 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 38 (5.9) | 37 (5.9) | 1 (4.8) | 0.999 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 66 (10.2) | 64 (10.2) | 2 (9.5) | 0.999 |

| Cancer, n (%) | 30 (4.6) | 28 (4.5) | 2 (9.5) | 0.254 |

| Heart disease, n (%) | 31 (4.8) | 30 (4.8) | 1 (4.8) | 0.999 |

| Aspirin, n (%) | 59 (9.1) | 57 (9.1) | 2 (9.5) | 0.999 |

| NSAID, n (%) | 4 (0.6) | 4 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0.999 |

| Atrophic gastritis, n (%) | 264 (40.8) | 254 (40.6) | 10 (47.6) | 0.518 |

| Intestinal metaplasia, n (%) | 83 (12.8) | 80 (12.8) | 3 (14.3) | 0.743 |

| Peptic ulcer, n (%) | 71 (11.0) | 69 (11.0) | 2 (9.5) | 0.999 |

SD: Standard deviation

Clinical features related to H. pylori recurrence

We performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses [Table 2]. The model included age, sex, follow-up month, type of regimens, smoking status, drinking status, history of cancer, atrophic gastritis and height. Adjusted OR for H. pylori recurrence was 1.08 per each increase in age (P = 0.012). Follow-up duration was significantly different in univariate analysis. However, it did not show significant difference between the two groups in the multivariate analysis (adjusted OR: 0.98, P = 0.085). Other variables showed no significance in multivariate logistic regression analysis either. Next, we performed multivariate regression analysis with age as a categorical variable (<50, 50–59 and ≥60 years). Adjusted ORs for H. pylori recurrence were 0.20 (95% CI: 0.06–0.69) and 0.25 (95% CI: 0.08–0.76) for age group of 50–59 years and age group of less than 50 years (P = 0.011 and P = 0.014, respectively) compared to age group of ≥60 years.

Table 2.

Odds ratios for H. pylori recurrence in regression model

| Variables | Crude OR | 95% CI | P | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age* | 1.07 | 1.02-1.13 | 0.006 | 1.08 | 1.02-1.14 | 0.012 |

| Male sex | 2.00 | 0.72-5.54 | 0.181 | 0.98 | 0.20-4.92 | 0.981 |

| Follow-up (mo)* | 0.97 | 0.95-0.99 | 0.031 | 0.98 | 0.95-1.00 | 0.085 |

| Second regimen | 0.66 | 0.15-2.89 | 0.582 | 0.53 | 0.11-2.49 | 0.418 |

| Current smoking | 0.88 | 0.32-2.44 | 0.807 | 0.89 | 0.30-2.65 | 0.830 |

| Current drinking | 1.30 | 0.50-3.40 | 0.594 | 1.19 | 0.39-3.64 | 0.762 |

| Cancer | 2.25 | 0.50-10.13 | 0.292 | 2.23 | 0.43-11.51 | 0.337 |

| Atrophic gastritis | 1.33 | 0.56-3.18 | 0.520 | 1.20 | 0.46-3.14 | 0.710 |

| Height (cm)* | 1.04 | 0.99-1.10 | 0.141 | 1.06 | 0.97-1.15 | 0.213 |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.*Included as continuous variables

DISCUSSION

Some meta-analyses have reported that the global recurrence rate of H. pylori is approximately 2.8% to 4.3% per person-year.[16,17] Our finding showed an annual recurrence rate of 0.91%, which was much lower than results reported in recent Korean studies.[11,12,13,18] The low recurrence rate of our study could be due to some plausible reasons. It is known that the recurrence rate is high in areas with high prevalence of H. pylori.[19,20] Therefore, our low recurrence could be due to a gradually decreasing trend of H. pylori prevalence in Korea recently.[15] A recent meta-analysis showed that the recurrence rate of H. pylori is inversely correlated with national health development index (HDI).[16] HDI is a composite index measuring average achievement in three basic dimensions of human development: (i) life expectance at birth; (ii) mean and expected years of schooling; and (iii) gross national income per capita.[16] Therefore, another reason for the low recurrence rate might be associated with an increasing HDI in South Korea. Because recrudescence rather than reinfection is likely to be responsible for most cases of recurrence,[20] public interest in H. pylori eradication and increase in compliance might have contributed to the decreased recurrence rate in South Korea. Lastly, our study targeted a health screening population. This might lead to outcomes different from previous studies that targeted patients who visited outpatient clinics.

As mentioned earlier, chronic H. pylori infection can induce premalignant histological changes. Recent researches have highlighted the global burden of noncardiac gastric cancer attributable to chronic H. pylori infection.[21,22] It is known that H. pylori treatment can improve gastric histology including mucosal inflammation and atrophic change.[23,24] Therefore, early treatment of H. pylori and persistence of treated condition might be important for the prevention of gastric cancer. In addition, recurrence of peptic ulcers is significantly lower in successfully eradicated patients.[25,26] In a recent randomized trial, no ulcer recurred in patients who maintained persistent H. pylori eradication for one year while the rate of ulcer recurrence after H. pylori eradication in ulcer patients was 6.7% to 25.7%.[27] To maintain H. pylori eradicated status, it is necessary to know which patients are more likely to have recurrence. In previous studies, underdeveloped country, male gender, low education level, low income, high number of family members, and the presence of peptic ulcer have been found to be risk factors related to H. pylori recurrence.[11,28,29,30]

The present study found that increasing age was an independent risk factor for H. pylori recurrence, consistent with a recent study,[31] but inconsistent with others.[32,33,34] There are a few possibilities to consider in terms of the positive association between advanced age and recurrence rate. First, severe atrophic and metaplastic changes due to increasing age can lead to false negative result on follow-up test after H. pylori eradication. Frequent use of proton pump inhibitors also can affect the result of H. pylori test. In addition, decreasing compliance due to lack of concern in H. pylori eradication and increasing resistance of H. pylori to eradication according to advanced age might be possible causes. Recurrence rates are known to be high in young children or adults with intellectual disability in some previous studies.[35,36,37] This may represent the importance of compliance in terms of maintaining successful eradication status. Lastly, elderly people tend to lack the idea of hygiene and maintain traditional eating habits in Korea. They could be vulnerable to H. pylori recurrence compared to younger people.

This is a relatively large-scale cohort study performed in an endemic areaof H. pylori. Because study subjects were enrolled from a screening cohort of participants who underwent regular follow-up endoscopy and routine urea breath test, results of H. pylori tests and follow-up intervals were strongly reliable. Moreover, we identified various clinical conditions including social history, anthropometrics, comorbidity, medication history, and endoscopic findings of cohort subjects. Thus, it could minimize possible confounders. In addition, we performed a follow-up test at least 4–5 weeks after the end of H. pylori eradication. Moreover, patients were instructed not to take any antacids during the period from the end of the treatment until the follow-up test of H. pylori. This might have increased the accuracy of follow-up tests. Nevertheless, this study had several limitations. First, this was a single-center study of a tertiary cancer center. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility of selection bias which could affect H. pylori recurrence rate. Multicenter studies to determine whether geographic location is associated with H. pylori recurrence rate will help identify the overall recurrence rate of the general population. Second, enrolled subjects voluntarily participated in screening endoscopy. These subjects may have had higher health concerns and better health behaviors or economic status compared to the general population. Third, we did not have data related to self-administration of proton pump inhibitors or antibiotics that could affect H. pylori results and underestimate the recurrence rate. Further observations are required to confirm persistent eradication status. Fourth, some patients with recurrence could potentially have had a false negative H. pylori test, meaning an eradication failure rather than a recurrence. In addition, patients without recurrence during the study period might be positive in subsequent follow-up, especially in those with short-term intervals. However, because annual follow-up was done and median follow-up period was relatively long, the probability of false negatives can be neglected. Fifth, we routinely performed rapid urease test on screening endoscopy after successful H. pylori eradication, some of which may be false negative. However, the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid urease test performed at the greater curvature of the corpus were as high as 96% and 100%, respectively, in our institute.[38] Finally, recrudescence and reinfection could not be clearly distinguished in our study.

CONCLUSION

Annual H. pylori recurrence rate is 0.91% in South Korea. Advanced age is at increased risk for H. pylori recurrence, and H. pylori treatment for patients under 60 years of age was more effective to maintain successful eradication status. In addition, our study implies that additional follow-up tests are required after a confirmation of successful H. pylori eradication, especially for elderly patients.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Humans, Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuipers EJ, Uyterlinde AM, Pena AS, Roosendaal R, Pals G, Nelis GF, et al. Long-term sequelae of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Lancet. 1995;345:1525–8. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)91084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahm MI, Choi KS, Park EC, Kwak MS, Lee HY, Hwang SS. Personal background and cognitive factors as predictors of the intention to be screened for stomach cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2473–9. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nam JH, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Nam SY, et al. OLGA and OLGIM stage distribution according to age and Helicobacter pylori status in the Korean population. Helicobacter. 2014;19:81–9. doi: 10.1111/hel.12112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chey WD, Leontiadis GI, Howden CW, Moss SF. ACG Clinical Guideline: Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:212–39. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim BJ, Kim HS, Song HJ, Chung IK, Kim GH, Kim BW, et al. Online registry for Nationwide Database of Current Trend of Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Korea: Interim Analysis. J Korean Med Sci. 2016;31:1246–53. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2016.31.8.1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Park JS, Park JE, Oh BS, Yoon BW, Kim HK, Lee JW, et al. Trend in the eradication rates of helicobacter pylori infection over the last 10 years in West Gyeonggi-do, Korea: A single center experience. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2017;70:232–8. doi: 10.4166/kjg.2017.70.5.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pellicano R, Ribaldone DG, Fagoonee S, Astegiano M, Saracco GM, Megraud F. A 2016 panorama of Helicobacter pylori infection: Key messages for clinicians. Panminerva Med. 2016;58:304–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JH, Kim N, Chung JI, Kang KP, Lee SH, Park YS, et al. Long-term follow up of Helicobacter pylori IgG serology after eradication and reinfection rate of H. pylori in South Korea. Helicobacter. 2008;13:288–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2008.00616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim MS, Kim N, Kim SE, Jo HJ, Shin CM, Lee SH, et al. Long-term follow-up Helicobacter pylori reinfection rate and its associated factors in Korea. Helicobacter. 2013;18:135–42. doi: 10.1111/hel.12018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Jung SW, Koo JS, Yim HJ, Lee SW. Helicobacter pylori recurrence after first- and second-line eradication therapy in Korea: The problem of recrudescence or reinfection. Helicobacter. 2014;19:202–6. doi: 10.1111/hel.12117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ryu KH, Yi SY, Na YJ, Baik SJ, Yoon SJ, Jung HS, et al. Reinfection rate and endoscopic changes after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:251–5. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheon JH, Kim N, Lee DH, Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, et al. Long-term outcomes after Helicobacter pylori eradication with second-line, bismuth-containing quadruple therapy in Korea. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:515–9. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200605000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim SH, Kwon JW, Kim N, Kim GH, Kang JM, Park MJ, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: Nationwide multicenter study over 13 years. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:104. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yan TL, Hu QD, Zhang Q, Li YM, Liang TB. National rates of Helicobacter pylori recurrence are significantly and inversely correlated with human development index. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:963–8. doi: 10.1111/apt.12293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu Y, Wan JH, Li XY, Zhu Y, Graham DY, Lu NH. Systematic review with meta-analysis: The global recurrence rate of Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:773–9. doi: 10.1111/apt.14319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MS, Kim N, Kim SE, Jo HJ, Shin CM, Park YS, et al. Long-term follow up Helicobacter Pylori reinfection rate after second-line treatment: Bismuth-containing quadruple therapy versus moxifloxacin-based triple therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:138. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsonnet J. What is the Helicobacter pylori global reinfection rate? Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17(Suppl B):46–8. doi: 10.1155/2003/567816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gisbert JP. The recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection: Incidence and variables influencing it. A critical review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2083–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.50043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Plummer M, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Forman D, de Martel C. Global burden of gastric cancer attributable to Helicobacter pylori. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:487–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leja M, Axon A, Brenner H. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2016;21(Suppl 1):3–7. doi: 10.1111/hel.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ito M, Haruma K, Kamada T, Mihara M, Kim S, Kitadai Y, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy improves atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia: A 5-year prospective study of patients with atrophic gastritis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1449–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu B, Chen MT, Fan YH, Liu Y, Meng LN. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on atrophic gastritis and intestinal metaplasia: A 3-year follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6518–20. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i41.6518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheeldon TU, Hoang TT, Phung DC, Bjorkman A, Granstrom M, Sorberg M. Long-term follow-up of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in Vietnam: Reinfection and clinical outcome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1047–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02408.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rollan A, Giancaspero R, Fuster F, Acevedo C, Figueroa C, Hola K, et al. The long-term reinfection rate and the course of duodenal ulcer disease after eradication of Helicobacter pylori in a developing country. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:50–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das R, Sureshkumar S, Sreenath GS, Kate V. Sequential versus concomitant therapy for eradication of Helicobacter Pylori in patients with perforated duodenal ulcer: A randomized trial. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:309–15. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.187605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McMahon BJ, Bruce MG, Hennessy TW, Bruden DL, Sacco F, Peters H, et al. Reinfection after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori: A 2-year prospective study in Alaska Natives. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1215–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruce MG, Bruden DL, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Sacco F, Hurlburt D, et al. Reinfection after successful eradication of Helicobacter pylori in three different populations in Alaska. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:1236–46. doi: 10.1017/S0950268814001770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salih BA. Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries: The burden for how long? Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:201–7. doi: 10.4103/1319-3767.54743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vilaichone RK, Wongcha Um A, Chotivitayatarakorn P. Low re-infection rate of helicobacter pylori after successful eradication in Thailand: A 2 years study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2017;18:695–7. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.3.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Soto G, Bautista CT, Roth DE, Gilman RH, Velapatino B, Ogura M, et al. Helicobacter pylori reinfection is common in Peruvian adults after antibiotic eradication therapy. J Infect Dis. 2003;188:1263–75. doi: 10.1086/379046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gomez Rodriguez BJ, Rojas Feria M, Garcia Montes MJ, Romero Castro R, Hergueta Delgado P, Pellicer Bautista FJ, et al. Incidence and factors influencing on Helicobacter pylori infection recurrence. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2004;96:620–7. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082004000900005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gisbert JP, Arata IG, Boixeda D, Barba M, Canton R, Plaza AG, et al. Role of partner's infection in reinfection after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2002;14:865–71. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200208000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nguyen TV, Bengtsson C, Nguyen GK, Yin L, Hoang TT, Phung DC, et al. Age as risk factor for Helicobacter pylori recurrence in children in Vietnam. Helicobacter. 2012;17:452–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2012.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sivapalasingam S, Rajasingham A, Macy JT, Friedman CR, Hoekstra RM, Ayers T, et al. Recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Bolivian children and adults after a population-based “screen and treat” strategy. Helicobacter. 2014;19:343–8. doi: 10.1111/hel.12137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wallace RA, Schluter PJ, Webb PM. Recurrence of Helicobacter pylori infection in adults with intellectual disability. Intern Med J. 2004;34:131–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1444-0903.2004.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kim CG, Choi IJ, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Nam BH, Kook MC, et al. Biopsy site for detecting Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:469–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]