Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) help determine the systems-level structure of the nervous system by controlling the physical interactions between neurons and glia during development and regeneration. Abnormalities in these molecules are becoming associated with a wide range of neurological disorders, including hydrocephalus, fetal alcohol syndrome, schizophrenia, and others, providing new insights into both clinical and basic research.

CAMs comprise a large group of cell surface macromolecules that provide recognition and adhesion between cells that express appropriate CAMs. Binding is primarily homophilic, that is, between like CAMs on adjacent cells, but heterophilic binding between similar molecules is also an important mode of interaction. CAMs are critical for migration and recognition of appropriate cells to form functional assemblies of neurons and for innervation of appropriate targets. They are involved in most of the major developmental processes, including cell migration, neurite initiation, neurite outgrowth, axon pathfinding, axon fasciculation, synaptogenesis, synapse stabilization, and myelination. They perform these functions not only by regulating cell adhesion, but also by activating intracellular signaling cascades that in turn control cytoskeletal dynamics, cell morphology, and neurite outgrowth.

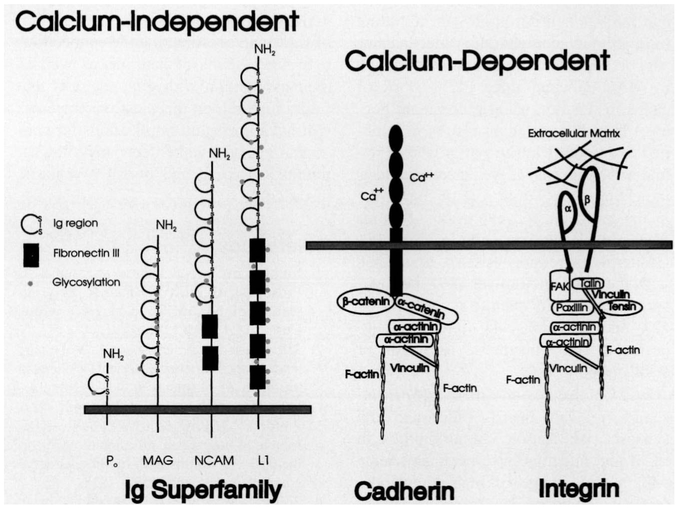

CAMs are divided functionally into calcium-dependent and calcium-independent groups (Fig. 1). The calcium-dependent CAMs include the cadherins, which contain several extracellular calcium-binding domains as well as an intracellular domain that interacts with the actin cytoskeleton and intracellular signaling pathways. Integrals require extracellular calcium for binding, and they are distinguished from the other CAMs by providing cell-to-extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesive contacts. Integrins are heterodimeric proteins that interact with the actin cytoskeleton through several intermediate proteins and signal transduction pathways.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of the molecular structure of the three major classes of cell adhesion molecules. The immunoglobulin (lg) superfamily of calcium-independent cell adhesion molecules do not require extracellular calcium ions for binding. Members of this class of CAMs have one or more lg domains and often fibronectin type III repeats in the extracellular domain. Cadherins and integrins require calcium ions for binding, and they interact with cytoskeletal proteins and proteins involved in signal transduction pathways. Integrins bind to components of the extracellular matrix, and cadherins bind homophilically to like molecules on adjoining cells.

The large family of calcium-independent CAMs do not require extracellular calcium ions for binding, and they include members of the immunoglobulin superfamily of CAMs. These molecules share a similar extracellular structure, consisting of several immunoglobulin (Ig) domains and often fibronectin type III repeats. Various isoforms are known, and many are regulated by phosphorylation and glycosylation. Expression of the various isoforms is highly regulated during development and regeneration.

NCAM

NCAM is the best known member of the Ig superfamily of CAMs. Its function is regulated during development by changes in gene expression, and by posttranslational modification; particularly glycosylation. This involves the addition of polysialic acid (PSA) to NCAM, catalyzed by the enzyme polysialyltransferase (1). Generally, PSA residues reduce the adhesive interaction between NCAM molecules because of steric interference from these large carbohydrate structures (2).

Abnormal levels of different isoforms of NCAM have been associated with some psychiatric disorders. People suffering from bipolar mood disorder type 1, recurrent unipolar major depression (3), and schizophrenia (4) show elevated levels of the 120-kDa isoform of NCAM in their CSF. Medication treatment does not affect CSF NCAM concentrations in these patients. This NCAM may be derived from CNS cells as a secreted soluble NCAM isoform. Patients with bipolar mood disorder type II have normal levels of NCAM 120 in the CSF.

Abnormalities in NCAM in these patients suggests that pathogenesis of schizophrenia and some mood disorders may be related to systems-level neuro-developmental defects. Certain structural abnormalities, including ventriculomegaly (moderately enlarged ventricles) and decreased temporal lobe volume have been reported for both schizophrenia and mood disorders of the type associated with abnormal NCAM levels (3). A corollary of abnormal CAM expression is suggested by experiments showing that skin fibroblasts cultured from schizophrenic patients display decreased cell adhesiveness and abnormal growth and morphology (5).

Recent research has shown that CAMs are involved in activity-dependent plasticity during development and activity-dependent synaptic plasticity in the postnatal nervous system (6). Disturbances in synaptic plasticity and restructuring may be involved in pathogenesis of certain neuropsychiatric diseases. In support of this hypothesis, PSA-NCAM has been implicated in long-term potentiation and learning and memory (7, 8), and postmortem examination of the hippocampal region shows a 20%–95% reduction in the number of PSA-NCAM immunoreactive cells in the hilus region of schizophrenic patients (9).

L1

The cell adhesion molecule L1 (Fig. 1) is expressed on neurons and Schwann cells, where it regulates neurite outgrowth, fasciculation, and Schwann cell-axon association, including myelination (10). The L1 gene is located in the q28 region of the long arm of the X chromosome (11). A number of severe neurological disorders show X-linked inheritance patterns, and in recent years it has become clear that many of these disorders are caused by mutations in the L1 gene. A number of reviews have been recently published on L1 mutations in neurological disease (12-14), including an excellent site on the internet by G. Van Camp, E. Fransen, G. Raes, and P. Willems from the University of Antwerp, Belgium (http://hgins.uia.ac.be/dnalab/11). This resource provides a detailed table of the 79 mutations, gene sequences and structure, references to the literature, and clinical descriptions of disorders associated with L1 mutations, with links to related internet sites.

The acronym “CRASH” has been proposed for the clinical syndrome consisting of Corpus callosum hypoplasia, mental Retardation, Adducted thumbs, Spastic paraplegia and Hydrocephalus, to encompass a number of X-linked disorders now known to be associated with mutations in the L1 gene (15). The CRASH syndrome therefore encompasses patients with X-linked hydrocephalus (HSAS), X-linked spastic paraplegia (SP1), agenesis of corpus callosum (ACC), and MASA syndrome, an acronym for an X-linked neurological disorder involving Mental retardation, Aphasia, Shuffling gait, and Adducted thumbs.

The fundamental importance of CAMs in nervous system development is evident from the diverse and serious consequences of defects in this one molecule. Agenesis of corpus callosum is an X-linked recessive disorder resulting in partial agenesis of the corpus callosum. These patients exhibit severe intellectual retardation and intractable seizures. An unusual facial appearance, spasticity, or hydrocephalus may be associated with the disease (16-18). X-linked spastic paraplegia, associated with mutation in the L1 gene (19, 20), is designated SPG1 to differentiate it from a similar phenotype resulting from mutation in the proteolipid protein (PLP) gene (designated SPG2). The disease is characterized by spasticity of lower extremities with varying degrees of mental retardation. X-linked hydrocephalus (HASA) is responsible for one-fourth of all male patients with hydrocephalus (21). The severity of the disorder can range from severe mental retardation (IQ 20–50), macrocephaly, and perinatal death, to relatively minimal enlargement of ventricles. Rosenthal et al. (22) showed that mutation in the L1 gene is associated with this phenotype. Hydrocephalus may result from congenital stenosis of the aqueduct of sylvius. Possible support for this may be provided by experimental studies showing that cleavage of sialic acid by injection of neuraminidase into experimental animals induces ependymal cell death and edema, leading to fusion of the lateral walls of the cerebral aqueduct and hydrocephalus of the third and lateral ventricles (23). However, HASA has also been reported in patients without aqueductal stenosis, suggesting that aqueductal stenosis may be the result rather than the cause of hydrocephalus (24). Adducted thumbs are present in about one-fourth of the cases (25).

Analysis of the functional consequences of mutations in the L1 gene is providing valuable insight into the function of this CAM during human development. The human L1 gene is 16 kilobases long and contains 28 exons. It encodes a protein of 1275 amino acids in length, including the 19-amino acid signal peptide that is cleaved from the mature protein (15). The cytoplasmic domain is highly conserved, sharing 100% homology between human and mouse. Currently, 79 mutations in the L1 gene have been described, consisting of missense point mutations, frame shifts, duplications, deletions, and premature stop codons in the extracellular domain that may result in a secreted form (12). Defects in both the cytoplasmic and extracellular domain of L1 are associated with these neurological disorders. Defects in the short cytoplasmic domain point to the importance of this molecule in interacting with cytoskeletal or intracellular signaling proteins during development because the extracellular domain would retain adhesive properties. Truncations of the L1 molecule can be lethal or result in severe hydrocephalus.

Mental retardation, hydrocephalus, and agenesis of the corpus callosum are also observed in children with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS). A recent study shows that ethanol interacts with a hydrophobic pocket within L1 to inhibit adhesion in rat cerebellar granule cells in a culture assay (26). Ethanol at a concentration reached in blood and brain after ingesting a single alcoholic beverage inhibits L1-dependent adhesion in mouse fibroblasts transfected with the human L1 gene. Alcohol had no detectable effect on NCAM140-mediated adhesion. These data suggest that disruption of L1-mediated cell-cell interactions could contribute to FAS and possibly other ethanol-associated impairments, such as memory disorders.

CAMs and Myelination

Antibody blockade experiments show that initiation of myelination of sensory neurons in culture is critically dependent on the neural cell adhesion molecule L1 (27). In addition, a number of other CAMs within the Ig superfamily, including myelin protein zero (Po) (28), myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAG), and myelin/oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) (29) are important components of myelin (30).

Po (Fig. 1) accounts for more than half of the total protein in compact PNS myelin (31), where it functions to stabilize the intraperiod line of compact PNS myelin by homophilic binding (32). Mice lacking Po show severe hypomyelination, abnormal motor coordination, and convulsions (33). Several point mutations in the Po gene in human chromosome la22–23 have been found in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 1B (CMT1), and in Dejerine-Sottas (DS) disease and congenital hypomyelination (CH) (13, 34). These diseases are characterized by peripheral nerve demyelination and progressive distal muscle atrophy.

MOG, a CNS myelin component with a single Ig domain, is absent from compact myelin, but it is expressed on the surface of oligodendrocytes and myelin sheath (35), where it presents an important antigen that may be involved in the pathogenesis of autoimmune demyelinating diseases of the CNS, for example, multiple sclerosis (MS) (36-38).

A carbohydrate epitope reacting with the HNK-1 antibody can be expressed on NCAM, L1, Po, MAG, and MOG, where it may function in homophilic and heterophilic binding (30). MAG, which has 5 Ig domains, is abnormally glycosylated in the trembler and quaking mice mutants, which exhibit dysmyelination and pathological symptoms of abnormal impulse conduction (39). Anti-MAG antibodies have been detected in patients with demyelinating neuropathy (40). These antibodies have similarities to the HNK-1 antibody (41), and they cause demyelination in experimental animals (42), with anatomical similarities to MS (41).

CAMs, Neurite Outgrowth and Regeneration, and Synaptic Plasticity

Neurite outgrowth and, therefore, nerve regeneration depend on local cues in the environment provided by ECM and cell adhesion molecules. MAG can bind some ECM components (43) and influence neurite outgrowth (44, 45). MAG has been shown to be a possible factor impeding axon regeneration in the CNS because it induces growth cone collapse and inhibits neurite outgrowth in culture (46), although compensatory mechanisms support axon outgrowth and myelination in MAG-deficient mice (47). Block of cadherin function using a dominant negative N-cadherin mutant results in inhibited axon and dendrite outgrowth of retinal ganglion cells, as well as other effects indicating an essential role of this CAM in the initiation and extension of axons from retinal ganglion cells in vivo (48). Cadherin expression is also associated with the node of Ranvier (49), postsynaptic densities of central synapses (50-52), and neuromuscular junction, suggesting a role in synapse formation or stabilization (53).

ECM molecules and their integrin receptors regulate neurite outgrowth and synapse stabilization. Abnormalities in ECM and integrins have been associated with a wide range of neurological defects, including defects in cerebellar development (54, 55); experimental allergic encephalomyelitis, an animal model of MS (56, 57); processing and aggregation of beta-amyloid-containing peptides in Alzheimer’s disease (58-60); invasion of glioma tumors in rat spinal cord (61); an X-linked form of Kallmann’s syndrome resulting in anosmia (62); Hirschprung’s disease (congenital absence of ganglion cells in the wall of colon) (63); and congenital muscular dystrophy, an autosomal recessive neurological disorder characterized by muscular dystrophy and brain white matter abnormalities (64). The importance of integrins in synaptic plasticity is suggested by their localization at synapses (65, 66) and blockade of LTP in slices incubated with a peptide inhibiting integrin function (67).

Therapeutic Opportunities

A better understanding of the role of CAMs in neurological disease and nerve regeneration may lead to better therapies. For example, experimental allergic encephalomyelitis is suppressed by monoclonal antibody to alpha 4 integrin (57) or MOG peptide (68), findings that could be useful in the treatment of autoimmune diseases, such as MS. Antibodies neutralizing CNS myelin-associated proteins improve regeneration in the CNS of experimental animals (69), and grafts of genetically modified fibroblasts expressing L1 improve regeneration in transected rat spinal cord (70).

Defective function of neurotransmitter receptors and cytosolic proteins are involved in the causation of many neurological disorders. The important function of CAMs in coordinating the connections between systems of neurons, as well as their association with glia, suggests that future research on this class of molecules will have important implications for congenital neurological defects, neurological trauma, disease, and some psychiatric disorders.

References

- 1.Muhlenhoff M, Eckhardt M, Bethe A, Frosch M, Gerardy-Schahan R. Polysialylation of NCAM by a single enzyme. Curr Biol 1966;6:1188–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rutishauser U, Landmesser L. Polysialic acid in the vertebrate nervous system: a promoter of plasticity in cell-cell interactions. Trends Neurosci 1996; 19:422–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Poltorak M, Frey MA, Wright R, et al. Increased neural cell adhesion molecule in the CSF of patients with mood disorder. J Neurochem 1966;66:1532–1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Poltorak M, Khoja I, Hemperly JJ, et al. Disturbances in cell recognition molecules (N-CAM and L1 antigen) in the CSF of patients with schizophrenia. Exp Neurol 1995;131:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahadik SP, Mukherjee S, Wakade CG, Laev H, Reddy RR, Schnur DB. Decreased adhesiveness and altered cellular distribution of fibronectin in fibroblasts from schizophrenic patients. Psychiatry Res 1994;53:878–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields RD, Itoh I. Neural cell adhesion molecules in activity-dependent development and synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci 1996;19:473–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muller D, Wang C, Skibo G, et al. PSA-NCAM is required for activity-induced synaptic plasticity. Neuron 1996; 17:413–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Becker CG, Artola A, Gerardy-Schahn R, Becker T, Wezl H, Schachner M. The polysialic acid modification of the neural cell adhesion molecule is involved in spatial learning and hippocampal long-term potentiation. J Neurosci Res 1996;45:143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbeau D, Liang JJ, Robitalille Y, Quirion R, Srivastava LK. Decreased expression of the embryonic form of the neural cell adhesion molecule in schizophrenic brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1995;92:2785–2789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faissner A, Krus J, Nieke J, Schachner M. Expression of neural cell adhesion molecule L1 during development in neurological mutants and in the peripheral nervous system. Dev Brain Res 1984;15:69–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djabali M, Mattei MG, Roux D, et al. The human L1 adhesion molecule is encoded by an HTF-associated gene located in Xq28. Cytogenet Cell Genet 1989;51:991. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fransen E, Vits L, Van Camp G, Willems PG. The clinical spectrum of mutations in L1, a neuronal cell adhesion molecule. Am J Med Genet 1996;64:73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uyemura K, Takeda Y, Asou H, Hayasaka K. Neural cell adhesion proteins and neurological diseases. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1994;116:1187–1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kenwrick S, Jouet M, Donnai D. X-linked hydrocephalus and MASA syndrome. J Med Genet 1996;33:59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fransen E, Lemmon V, Van Camp G, Vits L, Coucke P, Willems PJ. CRASH syndrome: clinical spectrum of corpus callosum hypoplasia, retardation, adducted thumbs, spastic paraparesis and hydrocephalus due to mutations in one single gene, L1. Eur J Hum Genet 1995;3:273–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menkes JH, Philippart M, Clark DB. Hereditary partial agenesis of corpus callosum. Arch Neurol 1964;11:198–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan P X-linked recessive inheritance of agenesis of the corpus callosum. J Med Genet 1983;20:122–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kang W-M, Huang C-C, Lin S-J. X-linked recessive inheritance of dysgenesis of corpus callosum in a Chinese family. Am J Med Genet 1992;44:619–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jouet M, Rosenthal A, Armstrong G, et al. X-linked spastic paraplegia (SPG1), MASA syndrome and X-linked hydrocephalus result from mutations in the L1 gene. Nat Genet 1994;7:402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi H, Garcia CA, Alfonso G, Marks HG, Hoffman EP. Molecular genetics of familial spastic paraplegia: a multitude of responsible genes. J Neurol Sci 1996;137:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burton BK. Recurrence risk for congenital hydrocephalus. Clin Genet 1979; 16:47–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosenthal A, Joulet M, Kenwrick S. Aberrant splicing of neural cell adhesion molecule L1 mRNA in a family with X-linked hydrocephalus. Nat Genet 1992;2:107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grondona JM, Perez-Martin M, Cifuentes M, et al. Ependymal denudation, aqueductal obliteration and hydrocephalus after a single injection of neuraminidase into the lateral ventricle of adult rats. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1996;55:999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willems PJ, Brouwer OF, Dijkstra I, Wilmink J. X-linked hydrocephalus. Am J Med Genet 1987;27:921–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landrieu P, Ninane J, Ferrier G, Lyon G. Aqueductal stenosis in X-linked hydrocephalus: a secondary phenomenon? Dev Med Child Neurol 1979;21:637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramanathan R, Wilkemeyer MF, Mittal B, Peridwes G, Charness ME. Alcohol inhibits cell-cell adhesion mediated by human L1. J Cell Biol 1996;133:381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood PM, Schachner M, Bunge RP. Inhibition of Schwann cell myelination in vitro by antibody to the L1 adhesion molecule. J Neurosci 1990;10:3635–3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemke G, Lamar E, Patterson J. Isolation and analysis of the gene encoding peripheral myelin protein zero. Neuron 1988; 1:73–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Linington C, Webb M, Woodhams P. A novel myelin associated glycoprotein defined by a mouse monoclonal antibody. J Neuroimmunol 1984;6:387–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quarles RH. Glycoproteins of myelin sheath. J Mol Neurosci 1997;81:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uyemura K, Kitamura K, Miura M. Structure and molecular biology of P0 glycoprotein In: Martenson RE, editor. Myelin: chemistry and biology. Boca Raton: CRC; 1992. p. 481–508. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Choe S. Packing of myelin protein zero. Neuron 1996;17:363–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giese KP, Martini R, Lemke G, Soriano P, Schachner M. Mouse PO gene disruption leads to hypomyelination, abnormal expression of recognition molecules, and degeneration of myelin and axons. Cell 1992;71:565–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warner LE, Hilz MJ, Appel SH, et al. Clinical phenotypes of different MPZ (PO) mutations may include Charcot-Marie Tooth type 1B, Dejerine-Sottas, and congenital hypomyelination. Neuron 1996;17:451–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brunner D, Lassmann H, Waehneldt TV, Matthieu JM, Linington C. Differential ultrastructural localization of myelin basis protein, myelin/oligodendroglial glycoprotein, and 2',3'-cyclic nucleotide 3'-phosphodiesterase in the CNS of adult rats. J Neurochem 1989;52:296–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adelmann M, Wood J, Benzel I, et al. The N-terminal domain of the myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) induces acute demyelinating experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the Lewis rat. J Neuroimmunol 1995;63:17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mendel I, Kerlero de Rosbo N, Ben-Nun A. A myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein peptide induces typical chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in H-2b mice: fine specificity and T cell receptor V beta expression of encephalitogenic T cells. Eur J Immunol 1995;25:1951–1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johns TG, Kerlero de Rosbo N, et al. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein induces a demyelinating encephalomyelitis resembling multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 1995;154:5536–5541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartoszewicz ZP, Noronha NB, Fujita N, et al. Abnormal expression and glycosylation of the large and small isoforms of myelin-associated glycoprotein in dysmyelinating trembler mutants. J Neurosci Res 1995;41:27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gabriel JM, Erne B, Miescher GC, et al. Selective loss of myelin-associated glycoprotein from myelin correlates with anti-MAG antibody titer in demyelinating paraproteinaemic polyneuropathy. Brain 1996;119:775–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quarles R, Colman D, Salzer J, Trapp B. Myelin-associated glycoprotein: structure-function relationships and involvement in neurological diseases In: Martenson R, editor. Myelin: biology and chemistry. Boca Raton: CRC; 1992. p. 4413–4448. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tatum AH. Experimental paraprotein neuropathy, demyelination by passive transfer of human IgM anti-myelin-associated glycoprotein. Ann Neurol 1993;33:502–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Probstmeier R, Fahrig T, Spiess E, Schachner M. Interactions of the neural cell adhesion molecule and myelin-associated glycoprotein with collagen type I: involvement in fibrillogenesis. J Cell Biol 1992;116:1063–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mukhopadhyay G, Doherty P, Walsh FS, Crocker PR, Filbin MT. A novel role for myelin-associated glycoprotein as an inhibitor of axonal regeneration. Neuron 1994;13:757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKerracher L, David S, Jackson DL, Kottis V, Dunn RJ, Braun PE. Identification of myelin-associated glycoprotein as a major myelin-derived inhibitor of neurite growth. Neuron 1994;13:805–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li M, Shibeta A, Li C, et al. Myelin-associated glycoprotein inhibits neurite/axon growth and causes growth cone collapse. J Neurosci Res 1996;46:404–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bartsch U. Myelination and axonal regeneration in the central nervous system of mice deficient in myelin-associated glycoprotein. J Neurocytol 1996;25:303–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Riehl R, Johnson K, Bradley R, et al. Cadherin function is required for axon outgrowth in retinal ganglion cells in vivo. Neuron 1996;17:837–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cifuentes-Diaz C, Nicolet M, Goudou D, Rieger F, Mege RM. N-cadherin expression in developing adult and denervating chicken neuromuscular system: accumulations at both the neuromuscular junction and the node of Ranvier. Development 1994;120:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beesley PW, Mummery R, Tibaldi J. N-cadherin is a major glycoprotein component of isolated rat forebrain postsynaptic densities. J Neurochem 1995;64:2288–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamagata M, Herman JP, Sanes JR. Lamina-specific expression of adhesion molecules in developing chick optic tectum. J Neurosci 1995;15:4556–4571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Uchida N, Honjo Y, Johnson KR, Wheelock JM, Takeichi M. The catenin/cadherin adhesion system is localized in synaptic junctions bordering transmitter release zones. J Cell Biol 1996; 135:767–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fannon AM, Colman DR. A model for central synaptic junctional complex formation based on the differential adhesive specificities of cadherins. Neuron 1996; 17:423–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeSilva U, D’Arcangelo G, Braden VV, et al. The human reelin gene: isolation, sequencing and mapping on chromosome 7. Genome Res 1997;2:157–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D’Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T. A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature 1995;374:719–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rose LM, Richards TL, Peterson J, Petersen R, Alvord EC Jr. Resolution of CNS lesions following treatment of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in macaques with monoclonal antibody to the CD18 leukocyte integrin. Mult Scler 1997;2:259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kent SJ, Karlik SJ, Cannon C, et al. A monoclonal antibody to alpha 4 integrin suppresses and reverses active experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 1995;58:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matsumota A, Enomoto T, Fujiwara Y, Baba H, Matsumoto R. Enhanced aggregation of beta-amyloid-containing peptides by extracellular matrix and their degradation by the 68 kDa serine protease prepared from human brain. Neurosci Lett 1996;220:159–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Storey E, Spurck T, Pickett-Heaps J, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. The amyloid precursor protein of Alzheimer’s disease is found on the surface of static but not activity motile portions of neurites. Brain Res 1996;735:59–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yamazaki T, Koo EH, Selkoe DJ. Cell surface amyloid beta-protein precursor colocalizes with beta 1 integrins at substrate contact sites in neural cells. J Neurosci 1997;17:1004–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Muir D, Johnson J, Rojiani M, Inglis BA, Rojiani A, Maria BL. Assesment of laminin-mediated glioma invasion in vitro and by glioma tumors engrafted with rat spinal cord. J Neurooncol 1996;30:199–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soussi-Yanicostas H, Hardelin JP, Arroyo-Jimenez MM, et al. Initial characterization of anosmin-1, a putative extracellular matrix protein synthesized by definite neuronal cell populations in the central nervous system. J Cell Sci 1996;109:1749–1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sullivan PB. Hirschprung’s disease. Arch Dis Child 1996;74:5–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matsumura K, Yamada H, Saito F, Sunada Y, Shimizu T. Peripheral nerve involvement in merosin-deficient congenital muscular dystrophy and dy mouse. Neuromuscul Disord 1997;7:7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Martin PT, Kaufman SJ, Kramer RH, Sanes JR. Synaptic integrins in developing, adult, and mutant muscle: selective association of alpha 1, alpha 7A, and alpha 7B integrins with the neuromuscular junction. Dev Biol 1996;174:125–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Einheber S, Schnapp LM, Salzer JL, Cappiello ZB, Milner TA. Regional and ultrastructural distribution of the alpha 8 integrin subunit in developing and adult rat brain suggests a role in synaptic function. J Comp Neurol 1996;370:105–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bahr BA, Staubli U, Xiao P, et al. Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser-selective adhesion and the stabilization of long-term potentiation: pharmacological studies and the characterization of a candidate matrix receptor. J Neurosci 1997;17:1320–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devaux B, Enderlin F, Wallner B, Smilek DE. Induction of EAE in mice with recombinant human MOG, and treatment of EAE with MOG peptide. J Neuroimmunol 1997;75:169–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bregman BS, Kunkel-Bagden E, Schnell L, Dia HN, Gao D, Schwab ME. Recovery from spinal cord injury mediated by antibody to neurite growth inhibitors. Nature 1995;378:498–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kobayashi S, Miura M, Asou H, Inoue HK, Ohye C, Uyemura K. Grafts of genetically modified fibroblasts expressing neural cell adhesion molecule L1 into transected spinal cord of adult rats. Neurosci Lett 1995;188:191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]