Abstract

Low-dose antithrombin supplementation therapy (1500 IU/d for 3 days) improves outcomes in patients with sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). This retrospective study evaluated the optimal antithrombin activity threshold to initiate supplementation, and the effects of supplementation therapy in 1033 patients with sepsis-induced DIC whose antithrombin activity levels were measured upon admission to 42 intensive care units across Japan. Of the 509 patients who had received antithrombin supplementation therapy, in-hospital mortality was significantly reduced only in patients with very low antithrombin activity (≤43%; bottom quartile; adjusted hazard ratio: 0.603; 95% confidence interval: 0.368-0.988; P = .045). Similar associations were not observed in patients with low, moderate, or normal antithrombin activity levels. Supplementation therapy did not correlate with the incidence of bleeding requiring transfusion. The adjusted hazard ratios for in-hospital mortality increased gradually with antithrombin activity only when initial activity levels were very low to normal but plateaued thereafter. We conclude that antithrombin supplementation therapy in patients with sepsis-induced DIC and very low antithrombin activity may improve survival without increasing the risk of bleeding.

Keywords: antithrombin, disseminated intravascular coagulation, mortality, sepsis, transfusion

Introduction

The activation of systemic coagulation and consequent disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is frequently observed in patients with sepsis and septic shock.1–3 Reduced plasma levels of physiological anticoagulants, including antithrombin (AT) and protein C, serve as markers of systemic coagulation activation.2,3 Particularly, decreased AT activity is a consequence of excessive thrombin generation,4 increased vascular permeability,5 accelerated AT degradation,6 and impaired AT synthesis during sepsis-induced DIC7 and is significantly associated with high mortality rates.8,9

Several randomized controlled trials have investigated the effects of high-dose AT administration in patients with sepsis.10–14 Although some have reported beneficial effects,10–12 the large KyberSept trial failed to show any overall beneficial effect of high-dose AT administration in the study population.13 However, a subgroup analysis of the KyberSept trial demonstrated that AT administration significantly improved survival in patients with sepsis-induced DIC.15 Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis of 3 randomized control trials by Umemura et al16 indicated in that although AT administration yielded survival benefits in patients with sepsis-induced DIC, such positive effect was not seen in all patients with sepsis. They also concluded that anticoagulant therapy increased the overall incidence of bleeding complications in patients with sepsis, but not in patients with sepsis-induced DIC.16

Several recent studies revealed that low-dose AT supplementation therapy (1500 IU/d for 3 days) improved treatment outcomes in patients with sepsis-induced DIC and decreased AT activity.17–20 In Japan, although AT supplementation therapy has been approved for patients with sepsis-induced DIC at AT activity ≤70%, there is no clear threshold for optimal AT activity to start supplementation. Therefore, we investigated AT activity levels and the effects of AT supplementation in patients with sepsis-induced DIC to determine the optimal AT activity threshold at which supplementation therapy should be initiated.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection and Data Collection

The Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (J-SEPTIC DIC) study (University Medical Information Network Clinical Trials Registry number UMIN000012543), a retrospective observational study, was conducted in 42 intensive care units (ICUs) at 40 institutions across Japan. The study was approved by the institutional review board of each participating hospital, and the need for informed consent was waived because of its retrospective design.

Patients admitted to the participating ICUs for the treatment of severe sepsis or septic shock between January 2011 and December 2013 were included in the J-SEPTIC DIC study. The definitions of “severe sepsis” and “septic shock” were based on the definitions issued by the International Sepsis Definitions Conference.21 Patients were excluded if they were younger than 16 years or developed severe sepsis/septic shock after admission to the ICU.

The J-SEPTIC DIC study retrospectively collected the following data: ICU characteristics; ICU admission route; patient age, sex, and body weight; preexisting organ dysfunction and hemostatic disorders; Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II score; Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score; systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) score; primary infection site; blood culture results; microorganism(s) causing sepsis; daily results of laboratory tests; adjunctive treatments; number of transfusions needed; bleeding complications; and hospital outcomes. Details of the collected data have been described in previous reports.19,22 The DIC scores were calculated using a scoring algorithm developed by the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine,23 and missing values were scored as zeroes. Participants without preexisting hemostatic disorders who had single-day DIC scores ≥4 during the first week after ICU admission were considered patients with DIC. We previously reported the results of several analyses based on data from the J-SEPTIC DIC study.19,22,24,25

In the present investigation, patients with sepsis-induced DIC and measured AT activity at the time of ICU admission were selected from the patients included in the J-SEPTIC DIC study. Patients with DIC received AT supplementation therapy at the discretion of the attending physician and were accordingly stratified into 2 groups: the AT group included patients who received AT supplementation therapy, and the control group included patients who did not receive AT supplementation therapy. Although no AT supplementation protocol was predefined, patients with DIC were typically administered 1500 IU of AT per day. Antithrombin supplementation therapy was continued for 3 days or until the patient’s condition improved.

Statistical Analyses

Data are expressed as numbers (%), means (standard deviations), or medians (interquartile ranges) as appropriate. Intergroup comparisons were performed using the Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 test, and Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the correlations between 2 variables.

An adjusted mortality analysis using propensity scores was performed to address the existing differences in the baseline characteristics between the AT and control groups caused by the retrospective nature of the study.26,27 The findings of various therapeutic interventions were used to estimate the propensity score because such investigations were usually performed simultaneously with AT supplementation, and the resulting scores were stratified into quintiles. To estimate the propensity scores, data were fitted to a logistic regression model in which AT treatment was set as a function of several variables, including patient characteristics, therapeutic interventions, and ICU characteristics. This resulted in models based on age, sex, body weight, admission route to the ICU, preexisting organ dysfunction, APACHE II score, total SOFA score on day 1, SIRS score on day 1, DIC score on day 1, primary infection site, blood culture results, microorganisms responsible for sepsis, laboratory tests (including white blood cell count, platelet count, hemoglobin level, AT activity level, and prothrombin time-international normalized ratio) on day 1, use of anti-DIC drugs, immunoglobulin use, low-dose steroid use, surgical interventions at the infection site, renal replacement therapy, renal replacement therapy for nonrenal indications, polymyxin B-direct hemoperfusion, ICU characteristics, ICU management policy, and the number of beds in the ICU. Some laboratory results (fibrinogen, fibrin/fibrinogen degradation product, D-dimer, and lactate levels) were not used to estimate propensity scores because the proportions of missing data in these categories exceeded 5%.

Patients were stratified into 4 subsets corresponding to the quartiles of AT activities distribution, recorded upon ICU admission. The overall association between AT supplementation therapy and mortality outcomes was assessed using a Cox regression model with the propensity score strata as a covariate. For bleeding complications, the odds ratio and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using a logistic regression model with the propensity score strata as the covariate. SPSS version 22.0 J (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois) was used for all statistical analyses. The level of statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

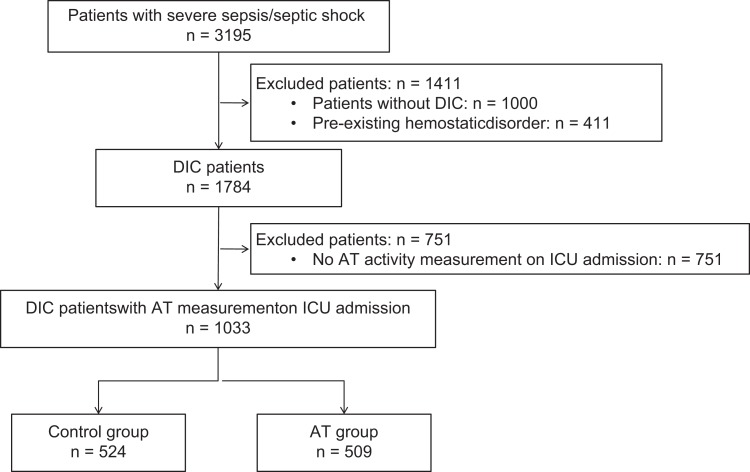

A total of 3195 patients with severe sepsis/septic shock were enrolled in the J-SEPTIC DIC study. Among these, 1784 patients were diagnosed with DIC, but AT activity levels measured upon ICU admission (day 1) were available only for 1033 patients; of these, 509 received AT therapy, while 524 did not (Figure 1). The characteristics of the patients with DIC with available day 1 AT activity measurements are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Study design for the selection of patients with DIC. AT indicates antithrombin; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients With Sepsis-Induced DIC.a,b

| Control | AT Supplementation | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 524 | n = 509 | ||

| ICU characteristics | |||

| General ICU | 219 (42) | 242 (48) | .069 |

| Emergency ICU | 305 (58) | 267 (53) | |

| ICU management policy | |||

| Closed policy | 354 (68) | 275 (54) | <.001 |

| Open policy | 84 (16) | 123 (24) | |

| Other | 86 (16) | 111 (22) | |

| Number of beds | 12 (8-20) | 10 (7-15) | <.001 |

| Age, years | 68 (1) | 70 (1) | .345 |

| Male sex | 298 (57) | 282 (55) | .661 |

| Body weight, kg | 56.9 (0.6) | 55.9 (0.6) | .181 |

| Admission route to ICU | |||

| Emergency department | 225 (43) | 202 (40) | .031 |

| Other hospital | 181 (35) | 156 (31) | |

| Hospital ward | 118 (23) | 151 (30) | |

| Preexisting organ dysfunction | |||

| Liver insufficiency | 7 (1) | 7 (1) | 1.000 |

| Chronic respiratory disorder | 21 (4) | 14 (3) | .304 |

| Chronic heart failure | 37 (7) | 24 (5) | .115 |

| Chronic hemodialysis | 37 (7) | 30 (6) | .452 |

| Immunocompromised | 67 (13) | 58 (11) | .506 |

| Severity | |||

| APACHE II score | 23 (17-29) | 25 (18-30) | .064 |

| SOFA score | |||

| Total | 10 (7-12) | 11 (8-14) | <.001 |

| Respiratory | 2 (1-3) | 2 (1-3) | .436 |

| Renal | 2 (0-3) | 2 (1-3) | .007 |

| Liver | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0-1) | .022 |

| Cardiovascular | 3 (0-4) | 3 (2-4) | <.001 |

| Coagulation | 1 (0-2) | 2 (1-2) | <.001 |

| Central nervous | 1 (0-3) | 1 (0-3) | .389 |

| DIC score | 5 (4-6) | 6 (4-7) | <.001 |

| SIRS score | 3 (3-4) | 3 (2-4) | .531 |

| Primary infection site | |||

| Abdomen | 160 (31) | 192 (38) | .069 |

| Lung | 126 (24) | 91 (18) | |

| Urinary tract | 98 (19) | 106 (21) | |

| Bone/soft tissue | 61 (12) | 60 (12) | |

| Cardiovascular | 15 (3) | 10 (2) | |

| Central nervous system | 19 (4) | 10 (2) | |

| Catheter related | 6 (1) | 7 (1) | |

| Others | 8 (2) | 11 (2) | |

| Unknown | 31 (6) | 22 (4) | |

| Blood culture | |||

| Positive | 252 (48) | 283 (56) | .039 |

| Negative | 254 (48) | 215 (42) | |

| Not taken | 18 (3) | 11 (2) | |

| Microorganisms causing sepsis | |||

| Gram-negative rod | 198 (38) | 241 (47) | .007 |

| Gram-positive coccus | 136 (26) | 125 (25) | |

| Fungus | 6 (1) | 4 (1) | |

| Virus | 6 (1) | 2 (0) | |

| Mixed infection | 64 (12) | 56 (11) | |

| Other | 17 (3) | 4 (1) | |

| Unknown | 97 (19) | 77 (15) | |

| Laboratory results on admission to ICU | |||

| White blood cell count, 109/L | 11.9 (5.7-19.3) | 11.4 (3.8-18.8) | .209 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 112 (59-183) | 82 (50-140) | <.001 |

| Hemoglobin, mmol/L | 11.0 (9.1-12.8) | 10.4 (8.9-12.2) | .003 |

| PT-INR | 1.3 (1.2-1.5) | 1.4 (1.3-1.7) | <.001 |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 424 (278-589) | 350 (225-513) | <.001 |

| FDP, mg/L | 26.6 (15.0-59.2) | 25.8 (14.8-63.8) | .879 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 13.6 (6.2-29.2) | 13.3 (6.1-27.9) | .696 |

| AT activity, % | 60 (48-75) | 51 (40-61) | <.001 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 2.9 (1.7-5.7) | 3.9 (2.3-6.7) | <.001 |

| Coadministered anti-DIC drug | |||

| Recombinant thrombomodulin | 161 (31) | 285 (56) | <.001 |

| Protease inhibitors | 45 (9) | 121 (24) | <.001 |

| Heparinoids | 29 (6) | 44 (9) | .033 |

| Other therapeutic intervention | |||

| Surgical intervention | 192 (37) | 252 (50) | <.001 |

| Immunoglobulin | 139 (27) | 286 (56) | <.001 |

| Low-dose steroid | 136 (26) | 184 (36) | <.001 |

| RRT | 147 (28) | 223 (44) | <.001 |

| Nonrenal indication RRT | 38 (7) | 72 (14) | <.001 |

| PMX-DHP | 87 (17) | 200 (39) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; AT, antithrombin; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; FDP, fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products; ICU, intensive care unit; PMX-DHP, polymyxin B-direct hemoperfusion; PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio; RRT, renal replacement therapy; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

aClosed policy, in ICU with closed policy, intensivists are the patient’s primary attending physician or are consulted as part of mandatory critical care; open policy, in ICU with open policy, intensivists are unavailable or are involved in the care only when the attending physician requests a consultation.

bData are expressed as numbers (%), means (SD), or medians (interquartile ranges). Patients were stratified into 2 groups according to whether or not they received AT supplementation therapy.

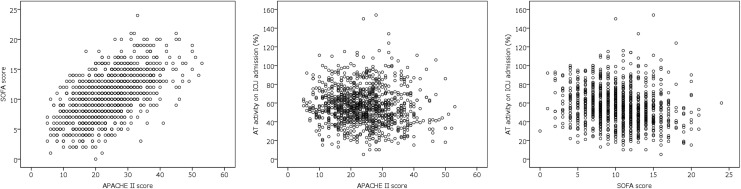

The relationships between APACHE II scores, SOFA scores, and AT activity levels upon ICU admission are presented in Figure 2. A strong correlation was observed between the APACHE II score and SOFA score (ρ = 0.568; P < .001). However, the AT activity on ICU admission did not correlate strongly with neither the APACHE II score (ρ = −0.097; P = .002) nor SOFA score (ρ = −0.223; P < .001).

Figure 2.

Scatter plots of APACHE II scores, SOFA scores, and AT activities. A strong correlation was observed between the APACHE II and SOFA scores (ρ = 0.568; P < .001). However, no strong correlation was observed between AT activity on ICU admission and the APACHE II score (ρ = −0.097; P = .002) or SOFA score (ρ = −0.223; P < .001). APACHE indicates Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; AT, antithrombin; ICU, intensive care unit; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment.

The C-statistic for the calculated propensity score was 0.815 and the Hosmer-Lemeshow χ2 value was 7.010 (df = 8), with a nonsignificant P value of .536 for the goodness of fit. The stratification of sepsis-induced DIC patients, based on AT activity upon ICU admission, yielded the following quartile-based subsets: very low AT activity (≤43%), low AT activity (44%-55%), moderate AT activity (56%-69%), and normal AT activity (≥70%). This approach led to similar sample sizes among the quartile-based patient subsets (ie, each group corresponded to one quartile of the distribution of AT activities recorded upon ICU admission). The characteristics of patients with sepsis-induced DIC stratified by AT activity level are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients With Sepsis-Induced DIC, Stratified According to AT Activity Levels.a

| Quartile of AT Activity on ICU Admission | Very Low ≤43% | Low 44% to 55% | Moderate 56% to 69% | Normal ≥70% | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | AT Supplementation | Control | AT Supplementation | Control | AT Supplementation | Control | AT Supplementation | |

| n = 89 | n = 170 | n = 123 | n = 146 | n = 137 | n = 127 | n = 175 | n = 66 | |

| Age, years | 70 (1) | 72 (1) | 69 (1) | 69 (1) | 67 (1) | 69 (1) | 68 (1) | 68 (2) |

| Male sex | 48 (54) | 105 (62) | 76 (62) | 76 (52) | 80 (58) | 76 (60) | 94 (54) | 25 (38) |

| Body weight, kg | 54.7 (1.5) | 54.9 (0.9) | 58.0 (1.2) | 58.0 (1.1) | 56.8 (1.2) | 56.9 (1.5) | 57.4 (1.2) | 56.2 (1.6) |

| Pre-existing organ dysfunction | ||||||||

| Liver insufficiency | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Chronic respiratory disorder | 3 (3) | 5 (3) | 7 (6) | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | 4 (3) | 6 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Chronic heart failure | 3 (3) | 9 (5) | 8 (7) | 8 (5) | 11 (8) | 5 (4) | 15 (9) | 2 (3) |

| Chronic hemodialysis | 7 (8) | 13 (8) | 10 (8) | 10 (7) | 9 (7) | 5 (4) | 11 (6) | 2 (3) |

| Immunocompromised | 12 (13) | 17 (10) | 11 (9) | 19 (13) | 12 (9) | 12 (9) | 32 (18) | 10 (15) |

| Severity | ||||||||

| APACHE II score | 25 (18-33) | 27 (20-32) | 23 (17-30) | 22 (16-28) | 21 (17-28) | 23 (17-28) | 23 (17-29) | 26 (19-31) |

| SOFA score, total | 11 (8-14) | 12 (10-14) | 10 (8-13) | 11 (8-13) | 10 (7-12) | 10 (8-13) | 9 (6-11) | 10 (7-13) |

| DIC score | 5 (4-7) | 6 (4-7) | 5 (4-7) | 6 (5-7) | 5 (4-6) | 5 (4-7) | 5 (4-6) | 5 (4-7) |

| SIRS score | 3 (3-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (3-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (2-4) | 3 (3-4) |

| Primary infection site | ||||||||

| Abdomen | 37 (42) | 84 (49) | 44 (36) | 53 (36) | 38 (28) | 40 (31) | 41 (23) | 15 (23) |

| Lung | 22 (25) | 28 (16) | 22 (18) | 23 (16) | 31 (23) | 29 (23) | 51 (29) | 11 (17) |

| Urinary tract | 7 (8) | 17 (10) | 21 (17) | 38 (26) | 32 (23) | 32 (25) | 38 (22) | 19 (29) |

| Bone/soft tissue | 11 (12) | 24 (14) | 12 (10) | 17 (12) | 19 (14) | 13 (10) | 19 (11) | 6 (9) |

| Cardiovascular | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (3) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 4 (6) |

| Central nervous system | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 5 (4) | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | 1 (1) | 8 (5) | 6 (9) |

| Catheter related | 0 (0) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | 2 (3) |

| Others | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (3) |

| Unknown | 8 (9) | 8 (5) | 11 (9) | 7 (5) | 5 (4) | 6 (5) | 7 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Blood culture | ||||||||

| Positive | 37 (42) | 88 (52) | 65 (53) | 85 (58) | 66 (48) | 67 (53) | 84 (48) | 43 (65) |

| Negative | 49 (55) | 75 (44) | 56 (46) | 59 (40) | 63 (46) | 59 (46) | 86 (49) | 22 (33) |

| Not taken | 3 (3) | 7 (4) | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 8 (6) | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Microorganisms causing sepsis | ||||||||

| Gram-negative rod | 31 (35) | 74 (44) | 52 (42) | 74 (51) | 49 (36) | 60 (47) | 66 (38) | 33 (50) |

| Gram-positive coccus | 26 (29) | 42 (25) | 29 (24) | 37 (25) | 43 (31) | 30 (24) | 38 (22) | 16 (24) |

| Fungus | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Virus | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Mixed infection | 11 (12) | 23 (14) | 16 (13) | 12 (8) | 17 (12) | 15 (12) | 20 (11) | 6 (9) |

| Other | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 8 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Unknown | 16 (18) | 30 (18) | 19 (15) | 18 (12) | 24 (18) | 18 (14) | 38 (22) | 11 (17) |

| Laboratory results on admission to ICU | ||||||||

| WBC count, 109/L | 8.5 (2.9-19.5) | 11.5 (2.7-18.2) | 11.6 (5.1-18.6) | 10.6 (4.1-18.1) | 13.9 (7.7-20.7) | 11.2 (3.8-19.6) | 11.8 (6.9-17.6) | 14.7 (6.9-20.3) |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 92 (49-164) | 76 (48-130) | 87 (49-143) | 65 (42-109) | 116 (66-186) | 104 (58-161) | 134 (80-212) | 114 (56-190) |

| Hemoglobin, mmol/L | 9.2 (7.9-10.8) | 9.6 (8.1-11.0) | 10.6 (9.0-12.6) | 10.2 (8.9-12.1) | 11.4 (9.7-12.9) | 11.3 (9.5-13.2) | 11.9 (9.9-13.1) | 11.4 (9.7-13.1) |

| PT-INR | 1.5 (1.3-1.9) | 1.6 (1.4-2.0) | 1.4 (1.2-1.6) | 1.4 (1.3-1.7) | 1.3 (1.1-1.4) | 1.4 (1.2-1.5) | 1.2 (1.1-1.4) | 1.3 (1.2-1.6) |

| Fibrinogen, g/L | 243 (148-391) | 259 (168-425) | 435 (272-546) | 376 (260-576) | 488 (323-656) | 402 (278-536) | 457 (327-616) | 379 (267-572) |

| FDP, mg/L | 24.4 (12.0-70.0) | 23.2 (13.4-54.0) | 26.4 (16.0-55.0) | 24.4 (14.4-56.4) | 26.5 (15.3-65.2) | 30.7 (17.0-72.1) | 29.0 (15.0-54.1) | 34.0 (14.6-85.2) |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 12.6 (5.1-32.6) | 12.0 (6.1-26.7) | 13.0 (6.1-23.5) | 12.4 (6.0-23.9) | 13.1 (5.7-32.4) | 15.3 (7.0-29.9) | 15.6 (6.6-30.8) | 10.4 (4.2-35.1) |

| AT activity, % | 35 (30-40) | 35 (27-40) | 50 (47-53) | 49 (46-53) | 62 (59-66) | 61 (58-65) | 84 (75-91) | 78 (72-90) |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 4.3 (2.4-8.9) | 4.5 (2.7-7.9) | 2.8 (1.8-5.8) | 3.2 (2.0-6.3) | 2.7 (1.6-5.3) | 3.8 (2.3-5.8) | 2.7 (1.7-5.0) | 4.0 (1.9-6.5) |

| Coadministered anti-DIC drug | ||||||||

| rTM | 23 (26) | 96 (56) | 44 (36) | 80 (55) | 47 (34) | 73 (57) | 47 (27) | 36 (55) |

| Protease inhibitors | 7 (8) | 46 (27) | 8 (7) | 38 (26) | 14 (10) | 25 (20) | 16 (9) | 12 (18) |

| Heparinoids | 2 (2) | 13 (8) | 8 (7) | 13 (9) | 7 (5) | 12 (9) | 12 (7) | 6 (9) |

| Other therapeutic intervention | ||||||||

| Surgical intervention | 39 (44) | 92 (54) | 56 (46) | 68 (47) | 55 (40) | 62 (49) | 42 (24) | 30 (45) |

| Immunoglobulin | 22 (25) | 93 (55) | 26 (21) | 85 (58) | 42 (31) | 72 (57) | 49 (28) | 36 (55) |

| Low-dose steroid | 30 (34) | 71 (42) | 30 (24) | 50 (34) | 31 (23) | 43 (34) | 45 (26) | 20 (30) |

| RRT | 19 (21) | 90 (53) | 30 (24) | 58 (40) | 45 (33) | 55 (43) | 53 (30) | 20 (30) |

| Nonrenal indication RRT | 8 (9) | 21 (12) | 3 (2) | 21 (14) | 14 (10) | 17 (13) | 13 (7) | 13 (20) |

| PMX-DHP | 16 (18) | 78 (46) | 25 (20) | 54 (37) | 27 (20) | 46 (36) | 19 (11) | 22 (33) |

| Transfusion | ||||||||

| Red cell concentrates | 2 (0-6) | 4 (0-8) | 0 (0-4) | 2 (0-6) | 0 (0-4) | 0 (0-4) | 0 (0-2) | 2 (0-4) |

| Fresh frozen plasma | 0 (0-10) | 5 (0-12) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-10) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-5) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-5) |

| Platelet concentrates | 0 (0-10) | 0 (0-30) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-20) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-15) | 0 (0-0) | 0 (0-20) |

| AT activity after admission to ICU | ||||||||

| AT activity on day 1 | 35 (30-40) | 35 (27-40) | 50 (47-53) | 49 (46-53) | 62 (59-66) | 61 (58-65) | 84 (75-91) | 78 (72-90) |

| AT activity on day 3 | 41 (28-53) | 60 (46-74) | 59 (44-60) | 69 (55-87) | 58 (47-67) | 74 (58-90) | 64 (54-73) | 68 (53-87) |

| AT activity on day 7 | 48 (40-64) | 59 (45-68) | 60 (53-62) | 74 (62-83) | 69 (57-81) | 75 (57-83) | 78 (60-89) | 85 (69-98) |

Abbreviations: AT, antithrombin; APACHE, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; FDP, fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products; ICU, intensive care unit; PMX-DHP, polymyxin B-direct hemoperfusion; PT-INR, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio; RRT, renal replacement therapy; rTM, recombinant thrombomodulin; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome; SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; WBC, white blood cell.

aData are expressed as numbers (%), means (SD), or medians (interquartile ranges). Patients were first stratified into 4 groups corresponding to the distribution quartiles of AT activity levels upon ICU admission and were further stratified according to whether or not they received AT supplementation therapy.

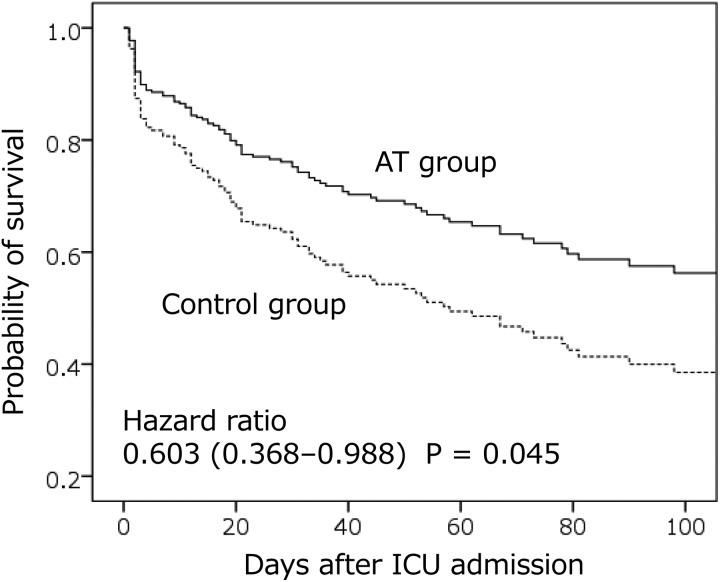

A Cox regression analysis revealed AT supplementation therapy significantly reduces mortality (adjusted hazard ratio: 0.603; 95% CI: 0.368-0.988; P = .045) in patients with sepsis-induced DIC and very low AT activity (≤43%; bottom quartile). However, no association between AT supplementation and survival was observed in patients with low, moderate, or normal AT activity. The subset-specific adjusted hazard ratios (95% CI) and P values were as follows: low AT activity: 0.921 (0.559-1.515), P = .745; moderate AT activity: 1.309 (0.713-2.404), P = .385; and normal AT activity: 0.607 (0.316-1.172), P = .138. Survival curves for patients with very low AT activity in the AT supplementation group and the control group are presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Survival curves in patients with sepsis-induced DIC and AT activity ≤43%. Antithrombin supplementation therapy significantly reduces mortality in patients with sepsis-induced DIC and very low AT activity. The solid line represents survival in the group receiving AT supplementation therapy (AT group), whereas the dotted line represents survival in the control group (ie, no AT supplementation therapy). AT indicates antithrombin; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; ICU, intensive care unit.

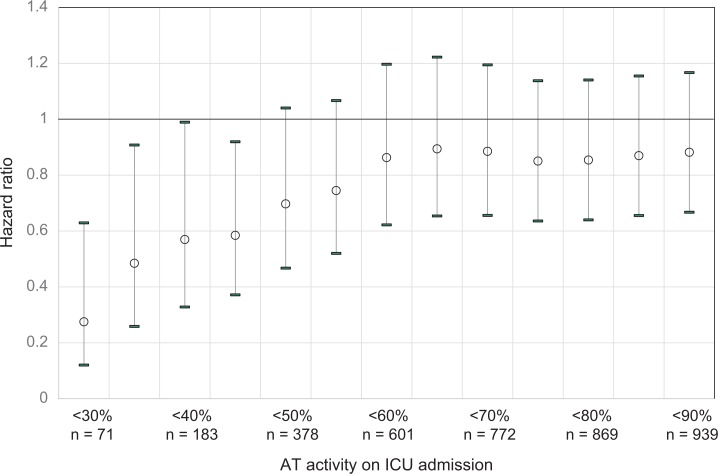

Table 3 summarizes the incidence of bleeding complications in each quartile subset in relation to AT supplementation therapy (AT supplementation vs control). There was no significant correlation between AT supplementation therapy status and the incidence of bleeding complications requiring transfusion, regardless of the AT activity level upon ICU admission. No bleeding-related death events occurred during the observation period. Additionally, the adjusted hazard ratios for inpatient mortality were found to increase gradually with each 10% increment in the AT activity threshold from very low to normal but remained relatively constant thereafter (Figure 4).

Table 3.

Relationship Between AT Levels and Incidence of Bleeding Complications.a

| AT Activity on ICU Admission | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | ≤43% | 0.942 (0.421-2.108) | .89 |

| Low | 44-55% | 0.555 (0.241-1.277) | .17 |

| Moderate | 56-69% | 0.579 (0.231-1.456) | .25 |

| Normal | ≥70% | 0.608 (0.228-1.620) | .32 |

Abbreviations: AT, antithrombin; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

aBleeding event data are expressed as number (%). Patients were first stratified into 4 groups corresponding to the distribution quartiles of AT activity levels upon ICU admission and were further stratified according to whether or not they received AT supplementation therapy. P values are given for the comparison between the AT supplementation group and control group in each AT activity quartile.

Figure 4.

Adjusted hazard ratios for in-hospital mortality in patients stratified according to AT activity levels. The adjusted hazard ratios increased gradually with every 10% increment in AT activity levels among patients exhibiting very low to normal AT activity. Thereafter, the hazard ratios remained relatively constant, regardless of AT activity levels. Open circles, hazard ratios; error bars, upper and lower 95% confidence intervals. AT indicates antithrombin; ICU, intensive care unit.

Discussion

This multicenter, nationwide, retrospective, observational study revealed that patients with sepsis-induced DIC and very low AT activity (≤43%) were optimal candidates for AT supplementation therapy. Furthermore, AT supplementation therapy was not found to increase bleeding complications in this patient subset. Some previous clinical trials included sepsis patients with AT activity levels ≤70%, which was approved for the initiation of AT supplementation therapy by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare in Japan.11,28–30 Hence, although the reports of these trials did not explicitly discuss the basis of the selected AT activity threshold values,11,28–30 these thresholds were most likely based on the normal range of AT activity (70%-120%).31 Although the KyberSept trial included patients with severe sepsis, irrespective of AT activity, more than 45% of the patients had AT activity levels <60%.13 A post hoc analysis of said study revealed patients with sepsis-induced DIC were more likely to have AT activity levels <60% than those without sepsis-induced DIC (72% vs 15%). Furthermore, AT administration significantly improved survival in patients with sepsis-induced DIC.15 Therefore, AT administration therapy may be more effective in patients with lower AT activity.

Through nonrandomized multicenter postmarketing surveys, Iba et al32,33 also reported that AT supplementation therapy was more effective in patients with DIC and decreased AT activity. Specifically, patients with DIC and an AT activity <40%, who were treated with 3000 IU AT per day had higher rates of survival and recovery from DIC than did those treated 1500 IU AT per day, without any increased risk of bleeding complications,33 a level of activity close to what we observed in the present study.

Antithrombin, an important physiologic anticoagulant, inhibits an estimated 80% of the coagulation activities of thrombin and coagulation factors X, IX, VII, XI, and XII.34 However, AT activity is frequently decreased in sepsis-induced DIC4–7 and is associated with high disease severity and mortality.8,9 A recent study revealed AT interacts with vascular endothelial cells35 and protects them by binding to glycosaminoglycans and suppressing capillary leakage,36 which in itself is found to exert anti-inflammatory effects during sepsis.37 Therefore, AT supplementation may improve outcomes in patients with sepsis and decreased AT activity.

In the present study, we stratified patients into 4 subsets corresponding to the quartiles of AT activity distribution. Although some studies used the classification and regression trees method to categorize patients,24,38 we used quartile-based stratification because the quartile is the most popular nonparametric criterion and can be used to group patients into comparably sized subsets.

The present study had several limitations due to its retrospective design. Hence, the results should be considered with care. The most significant limitation is that we could not identify the exact timing and duration of therapeutic interventions. However, AT supplementation therapy was usually administered simultaneously with other therapeutic interventions upon ICU admission, which were unaffected by AT supplementation therapy. Therefore, we considered it acceptable to use these therapeutic interventions for estimating the propensity scores. Second, the AT activities of patients with sepsis-induced DIC were not measured in more than 40% of cases upon ICU admission, as measurement of AT activity is not common practice in emergency settings in Japan. These patients were excluded from the present analysis. Third, detailed information on the cause of death was unavailable in the present study. Fourth, the baseline clinical risk factors for a bleeding tendency were not evaluated, although their effects may be reflected in the estimation of propensity scores. Fifth, the data set was occasionally incomplete for specific laboratory results (fibrinogen, fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products, D-dimers, and lactate levels) upon ICU admission.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the optimal candidates for AT supplementation therapy for sepsis-induced DIC were not those with ≤70% AT activity but those with very low AT activity (<43%). In this specific patient subset, AT supplementation therapy may improve survival rates without increasing the risk of bleeding complications.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their appreciation for the investigators of the J-SEPTIC DIC study group, who collected and assessed data at each participating institution. Their support and efforts over the course of the study were invaluable. The J-SEPTIC DIC study group included Shinjiro Saito (Jikei University School of Medicine), Shigehiko Uchino (Jikei University School of Medicine), Yusuke Iizuka (Shonan Kamakura General Hospital), Masamitsu Sanui (Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center), Kohei Takimoto (Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine), Toshihiko Mayumi (University of Occupational and Environmental Health), Takeo Azuhata (Nihon University School of Medicine), Fumihito Ito (Ohta Nishinouchi Hospital), Shodai Yoshihiro (JA Hiroshima General Hospital), Katsura Hayakawa (Saitama Red Cross Hospital), Tsuyoshi Nakashima (Wakayama Medical University), Takayuki Ogura (Japan Red Cross Maebashi Hospital), Eiichiro Noda (Kyushu University Hospital), Yoshihiko Nakamura (Fukuoka University Hospital), Ryosuke Sekine (Ibaraki Prefectural Central Hospital), Yoshiaki Yoshikawa (Osaka General Medical Center), Motohiro Sekino (Nagasaki University Hospital), Keiko Ueno (Tokyo Medical University Hachioji Medical Center), Yuko Okuda (Kyoto First Red-Cross Hospital), Masayuki Watanabe (Saiseikai Yokohamasi Tobu Hospital), Akihito Tampo (Asahikawa Medical University), Nobuyuki Saito (Nippon Medical School Chiba Hokusoh Hospital), Yuya Kitai (Kameda Medical Center), Hiroki Takahashi (Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine), Iwao Kobayashi (Asahikawa Red Cross Hospital), Yutaka Kondo (University of the Ryukyus), Wataru Matsunaga (Jichi Medical University Saitama Medical Center), Sho Nachi (Gifu University Hospital), Toru Miike (Saga University Hospital), Hiroshi Takahashi (Steel Memorial Muroran Hospital), Shuhei Takauji (Sapporo City General Hospital), Kensuke Umakoshi (Ehime University Hospital), Takafumi Todaka (Tomishiro Central Hospital), Hiroshi Kodaira (Akashi City Hospital), Kohkichi Andoh (Sendai City Hospital), Takehiko Kasai (Hakodate Municipal Hospital), Yoshiaki Iwashita (Mie University Hospital), Hideaki Arai (University of Occupational and Environmental Health), Masato Murata (Gunma University), Masahiro Yamane (KKR Sapporo Medical Center), Kazuhiro Shiga (Seirei Mikatahara General Hospital), and Naoto Hori (Hyogo College of Medicine). The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.jp) for English language editing.

Authors’ Note: M.H. contributed to data acquisition, as well as to the design of the present study, statistical analysis of the data, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. K.Y. and D.K. contributed to data acquisition, as well as to the design of the present study and interpretation of the results. K.O. contributed substantially to the statistical analysis of the collected data. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: M.H. was a principal investigator of the J-SEPTIC DIC study. K.Y. and D.K. were the main investigators of the J-SEPTIC DIC study.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: M.H. received a speaker’s fee and research funding from Asahi Kasei Pharma Co for an unrelated basic research project.

References

- 1. Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(9):840–851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hunt BJ. Bleeding and coagulopathies in critical care. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):847–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Okamoto K, Tamura T, Sawatsubashi Y. Sepsis and disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Intensive Care. 2016;4:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Opal SM, Kessler CM, Roemisch J, Knaub S. Antithrombin, heparin, and heparan sulfate. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(5 Suppl):S325–S331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Aibiki M, Fukuoka N, Umakoshi K, Ohtsubo S, Kikuchi S. Serum albumin levels anticipate antithrombin III activities before and after antithrombin III agent in critical patients with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Shock. 2007;27(2):139–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Seitz R, Wolf M, Egbring R, Havemann K. The disturbance of hemostasis in septic shock: role of neutrophil elastase and thrombin, effects of antithrombin III and plasma substitution. Eur J Haematol. 1989;43(1):22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sie P, Letrenne E, Caranobe C, Genestal M, Cathala B, Boneu B. Factor II related antigen and antithrombin III levels as indicators of liver failure in consumption coagulopathy. Thromb Haemost. 1982;47(3):218–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fourrier F, Chopin C, Goudemand J, et al. Septic shock, multiple organ failure, and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Compared patterns of antithrombin III, protein C, and protein S deficiencies. Chest. 1992;101(3):816–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Levi M, van der Poll T. The role of natural anticoagulants in the pathogenesis and management of systemic activation of coagulation and inflammation in critically ill patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2008;34(5):459–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Inthorn D, Hoffmann JN, Hartl WH, Muhlbayer D, Jochum M. Antithrombin III supplementation in severe sepsis: beneficial effects on organ dysfunction. Shock. 1997;8(5):328–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Baudo F, Caimi TM, de Cataldo F, et al. Antithrombin III (ATIII) replacement therapy in patients with sepsis and/or postsurgical complications: a controlled double-blind, randomized, multicenter study. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(4):336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Eisele B, Lamy M, Thijs LG, et al. Antithrombin III in patients with severe sepsis. A randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind multicenter trial plus a meta-analysis on all randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trials with antithrombin III in severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24(7):663–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Warren BL, Eid A, Singer P, et al. KyberSept Trial Study Group. Caring for the critically ill patient. High-dose antithrombin III in severe sepsis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1869–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gonano C, Sitzwohl C, Meitner E, Weinstabl C, Kettner SC. Four-day antithrombin therapy does not seem to attenuate hypercoagulability in patients suffering from sepsis. Crit Care. 2006;10(6):R160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kienast J, Juers M, Wiedermann CJ, et al. Treatment effects of high-dose antithrombin without concomitant heparin in patients with severe sepsis with or without disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4(1):90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Umemura Y, Yamakawa K, Ogura H, Yuhara H, Fujimi S. Efficacy and safety of anticoagulant therapy in three specific populations with sepsis: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Thromb Haemost. 2016;14(3):518–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tagami T, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Supplemental dose of antithrombin use in disseminated intravascular coagulation patients after abdominal sepsis. Thromb Haemost. 2015;114(3):537–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tagami T, Matsui H, Horiguchi H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Antithrombin and mortality in severe pneumonia patients with sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation: an observational nationwide study. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12(9):1470–1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hayakawa M, Kudo D, Saito S, et al. Antithrombin supplementation and mortality in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: a multicenter retrospective observational study. Shock. 2016;46(6):623–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gando S, Saitoh D, Ishikura H, et al. A randomized, controlled, multicenter trial of the effects of antithrombin on disseminated intravascular coagulation in patients with sepsis. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):R297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. International Sepsis Definitions Conference. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hayakawa M, Yamakawa K, Saito S, et al. Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (JSEPTIC DIC) Study Group. Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin and mortality in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation. A multicentre retrospective study. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115(6):1157–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gando S, Iba T, Eguchi Y, et al. Japanese Association for Acute Medicine Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (JAAM DIC) Study Group. A multicenter, prospective validation of disseminated intravascular coagulation diagnostic criteria for critically ill patients: comparing current criteria. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(3):625–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yamakawa K, Umemura Y, Hayakawa M, et al. Japan Septic Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (J-Septic DIC) Study Group. Benefit profile of anticoagulant therapy in sepsis: a nationwide multicentre registry in Japan. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hayakawa M, Saito S, Uchino S, et al. Characteristics, treatments, and outcomes of severe sepsis of 3195 ICU-treated adult patients throughout Japan during 2011-2013. J Intensive Care. 2016;4:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gayat E, Pirracchio R, Resche-Rigon M, Mebazaa A, Mary JY, Porcher R. Propensity scores in intensive care and anaesthesiology literature: a systematic review. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(12):1993–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. D’Agostino RB, Jr, D’Agostino RB., Sr Estimating treatment effects using observational data. JAMA. 2007;297(3):314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nishiyama T, Kohno Y, Koishi K. Effects of antithrombin and gabexate mesilate on disseminated intravascular coagulation: a preliminary study. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(7):1219–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Diaz-Cremades JM, Lorenzo R, Sanchez M, et al. Use of antithrombin III in critical patients. Intensive Care Med. 1994;20(8):577–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Blauhut B, Kramar H, Vinazzer H, Bergmann H. Substitution of antithrombin III in shock and DIC: a randomized study. Thromb Res. 1985;39(1):81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Khor B, Van Cott EM. Laboratory tests for antithrombin deficiency. Am J Hematol. 2010;85(12):947–950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Iba T, Saito D, Wada H, Asakura H. Efficacy and bleeding risk of antithrombin supplementation in septic disseminated intravascular coagulation: a prospective multicenter survey. Thromb Res. 2012;130(3):e129–e133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iba T, Saitoh D, Wada H, Asakura H. Efficacy and bleeding risk of antithrombin supplementation in septic disseminated intravascular coagulation: a secondary survey. Crit Care. 2014;18(5):497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roemisch J, Gray E, Hoffmann JN, Wiedermann CJ. Antithrombin: a new look at the actions of a serine protease inhibitor. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2002;13(8):657–670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chappell D, Brettner F, Doerfler N, et al. Protection of glycocalyx decreases platelet adhesion after ischaemia/reperfusion: an animal study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2014;31(9):474–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Iba T, Saitoh D. Efficacy of antithrombin in preclinical and clinical applications for sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation. J Intensive Care. 2014;2(1):66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Iba T, Thachil J. Present and future of anticoagulant therapy using antithrombin and thrombomodulin for sepsis-associated disseminated intravascular coagulation: a perspective from Japan. Int J Hematol. 2016;103(3):253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yoshimura J, Yamakawa K, Ogura H, et al. Benefit profile of recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin in sepsis-induced disseminated intravascular coagulation: a multicenter propensity score analysis. Crit Care. 2015;19:78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]