Abstract

Standard anticoagulant treatment alone for acute lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is ineffective in eliminating thrombus from the deep venous system, with many patients developing postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). Because catheter-directed thrombolysis (CDT) can dissolve the clot, reducing the development of PTS in iliofemoral or femoropopliteal DVT. This meta-analysis compares CDT plus anticoagulation versus standard anticoagulation for acute iliofemoral or femoropopliteal DVT. Ten trials were included in the meta-analysis. Compared with anticoagulant alone, CDT was shown to significantly increase the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein (P < .00001; I 2 = 44%) and reduce the risk of PTS (P = .0002; I 2 = 79%). In subgroup analysis of randomized controlled trials, CDT was not shown to prevent PTS (P = .2; I 2 = 59%). A reduced PTS risk was shown, however, in nonrandomized trials (P < .00001; I 2 = 47%). Meta-analysis showed that CDT can reduce severe PTS risk (P = .002; I 2 = 0%). However, CDT was not indicated to prevent mild PTS (P = .91; I 2 = 79%). A significant increase in bleeding events (P < .00001; I 2 = 33%) and pulmonary embolism (PE) (P < .00001; I 2 = 14%) were also demonstrated. However, for the CDT group, the duration of stay in the hospital was significantly prolonged compared to the anticoagulant group (P < .00001; I 2 = 0%). There was no significant difference in death (P = .09; I 2 = 0%) or recurrent venous thromboembolism events (P = .52; I 2 = 58%). This meta-analysis showed that CDT may improve patency of the iliofemoral vein or severe PTS compared with anticoagulation therapy alone, but measuring PTS risk remains controversial. However, CDT could increase the risk of bleeding events, PE events, and duration of hospital stay.

Keywords: catheter-directed thrombolysis, anticoagulation, deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

Introduction

Acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) of the lower extremities occurs in about 1 or 2 cases/1000 persons in the general population.1 Deep vein thrombosis is a potentially progressive disease with complex clinical sequelae, such as pulmonary embolism (PE) and postthrombotic syndrome (PTS). Although anticoagulation aids in the prevention of thrombus extension, PE, and thrombus recurrence, many patients develop venous dysfunction leading to PTS.2 Postthrombotic syndrome occurs in 25% to 46% of patients with DVT3 and is characterized by a multitude of symptoms such as leg swelling, heaviness, pain, skin hyperpigmentation, venous varicosities, and venous ulcers.4 Postthrombotic syndrome is associated with reduced individual, health-related quality of life and a substantially increased economic burden.5

Because anticoagulation does not directly promote thrombus dissolution to reduce the thrombus burden, chemical, surgical, and mechanical strategies have been developed for removing thrombus, rather than leaving it in situ.6 Catheter-directed thrombolysis has been recommended as an effective therapy for DVT because it can reduce the thrombus load rapidly, relieve DVT symptoms promptly, maintain venous valve function, and reduce recurrence of DVT.7–10 Catheter-directed thrombolysis therapy was achieved by placing a catheter in the contralateral femoral vein, the right internal jugular vein, or the ipsilateral popliteal vein for direct intraluminal thrombus infusion. An attempt was used to cross the thrombosed vein with a 0.035-inch guidewire. Once the guidewire is across the thrombus, multiple side-hole catheters were advanced into the thrombus to assure maximum delivery of thrombolytics. However, bleeding events are higher in CDT than in anticoagulation, impacting the safety of CDT therapy.7,8 We performed an updated meta-analysis on 4 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and 6 comparative studies contrasting CDT plus anticoagulation with anticoagulation alone for the treatment of lower extremity DVT, in an attempt to resolve this discrepancy and provide evidence to physicians.

Methods

Literature Search

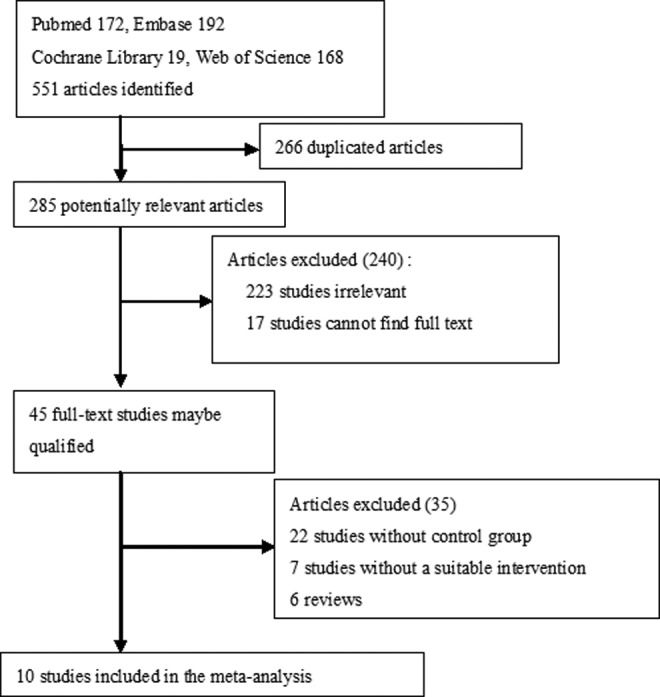

Using PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library, we searched literature published between January 1, 1980, and April 1, 2017. The search terms included the following: CDT or standard anticoagulation or iliofemoral/lower extremity or DVT; and/or comparative studies or RCTs or cohort studies or retrospective or prospective studies. Inclusion criteria were (1) studies comparing CDT plus anticoagulation (experimental group) with anticoagulation (control group) and (2) effectiveness of intact clinical data. There were no language restrictions. Ten studies were located (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature review.

Two investigators (Tang and Lu) independently extracted data utilizing a data abstraction tool: number of patients in experimental (CDT plus anticoagulation) and control (anticoagulation) group, study quality, time of follow-up, and primary and secondary outcomes. The primary outcome was the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein, and the secondary outcomes included the risk of PTS, bleeding events, PE events, death, duration of hospital stay, and hospital charges.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Details of the publication, inclusion and exclusion criteria, demographics of the study participants, interventions, and outcomes (primary and secondary outcomes) were gathered and reviewed. Risk of bias in the studies (eg, containing masking of participants, intention-to-treat analysis, incomplete or unclear data, and time to follow-up) was also assessed. Study quality was assessed by the modified Jadad scale and Newcastle–Ottawa scale (NOS).11 Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Review Manager (version 5.1; Cochrane Collaboration software). We used fixed-effects models for primary outcomes and partial secondary outcomes (adverse events) and utilized random-effects models for outcomes related to duration of stay in hospital and hospital charges. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by I 2. The level of heterogeneity was demarcated as low (I 2 = 25%-49%), moderate (I 2 = 50%-74%), and high (I 2 ≥ 75%) heterogeneity. Primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed using odds ratios, with a 2-sided statistical significance level of 5%.

Results

Study Characteristics and Quality

The initial search strategy identified 45 full-text articles, and 35 citations were initially screened. Ten trials met the appropriate criteria for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). Four RCTs7,10,12,15 (the ATTRACT study was presented by Suresh Vedantham, MD, at the 2017 Society of Interventional Radiology [SIR] Annual Scientific Meeting) and 6 comparative studies12–17 included experimental groups that received CDT therapy for acute lower extremity DVT and control groups that received standard anticoagulation therapy for acute lower extremity DVT. The quality of RCTs was evaluated by the modified Jadad score and the nonrandomized trials were assessed by the NOS score.11 Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics for each study.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Included Clinical Trials.

| Study | Group | Sample | Follow-up | Mean age, years | Females, % | Region | Outcomes | Dosage of Thrombolytic | Study Quality Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enden12 | CDT+AC | 50 | 6 months | 53 | 64 | Norway | Iliofemoral patency | Alteplase, 20 mg, 24-96 hours | RCT |

| AC | 53 | 51 | 60.4 | Bleeding events | LMWH (75-100 µ/kg, every 12 hours), warfarin INR: 2.0-3.0 | Jadad: 5 | |||

| Riyaz14 | CDT+AC | 3594 | 72 months | 53.2 | 49.3 | United States | Mortality, duration of hospital | NA | Retrospective NOS:8 |

| AC | 3594 | 65.4 | 53.6 | Bleeding, PE events | NA | ||||

| Elsharawy10 | CDT+AC | 18 | 6 months | 44 | 66.6 | Egypt | Iliofemoral patency, duration of hospital stay | Streptokinase, first hour 1 million units, 100 000 units/h | RCT; Jadad: 5 |

| AC | 17 | 49 | 70.6 | Mortality, PE events | UFH (initial of 5000 U, maintain PTT twice the normal), warfarin INR: 2.0-3.0 | ||||

| Wang9 | CDT+AC | 47 | 38 months | NA | NA | China | Iliofemoral patency, PTS | Urokinase, 2000-40 000 U/h, 3-7 days | Retrospective |

| AC | 81 | NA | NA | LMWH (75-100 µ/kg, every 12 h), warfarin INR: 2.0-3.0 | NOS:7 | ||||

| Srinivas16 | CDT+AC | 27 | 6 months | 39 | 48.1 | India | Iliofemoral patency, PTS | Streptokinase, 100 000 units/h | Prospective NOS:9 |

| AC | 28 | C | 53 | 42.9 | Bleeding, PE events, mortality | UFH (initial of 5000 U, 1000 U/h for 48 hours), warfarin INR: 2.0-3.0 | |||

| Yevgeniy17 | CDT+AC | 306 | 72 months | NA | NA | United States | Mortality, hospital charges | NA | Retrospective |

| AC | 306 | NA | NA | Duration of hospital stay | NA | NOS:7 | |||

| AbuRahma13 | CDT+AC | 18 | 60 months | 46 | 61 | United States | Iliofemoral patency, PTS | Urokinase, 4500 U/kg/h, 24-48 hours | Prospective |

| AC | 33 | 49 | 58 | Bleeding, PE events, mortality | UFH (initial of 5000 U, 1000 U/h for 5 days) warfarin INR: 2.0-3.0 | NOS:9 | |||

| Enden7 | CDT+AC | 90 | 24 months | 53.3 | 35.6 | Norway | Iliofemoral patency, PTS | Alteplase, 20 mg, 24-96 hours | RCT |

| AC | 99 | 50 | 38.4 | Bleeding events | LMWH (75-100 µ/kg, every 12 hours), warfarin INR: 2.0-3.0 | Jadad: 5 | |||

| Lee8 | CDT+AC | 27 | 15.2 months | 62.4 | 51.8 | Taiwan | Iliofemoral patency, PTS | Urokinase, 600-1200 U/kg/h, 2-3 days | Retrospective |

| AC | 26 | 59.8 | 46.2 | Bleeding events | LMWH (75-100 µ/kg, every 12 hours), warfarin INR: 2.0-3.0 | NOS: 9 | |||

| Suresh15 | CDT+AC | 337 | 24 months | 53 | 38% | United States | PTS, bleeding events | NA | RCT |

| AC | 355 | Recurrent VTE events | NA | Jadad: 5 |

Abbreviations: AC, anticoagulant; CDT, catheter-directed thrombolysis; INR, international normalized ratio; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; NA, not available; NOS, Newcastle–Ottawa Scale; PE, pulmonary embolism; PTS, postthrombotic syndrome; PTT, partial thromboplastin time; RCTS, randomized controlled trials; UFH, unfractionated heparin; VTE, venous thrombus embolism.

Primary Outcome

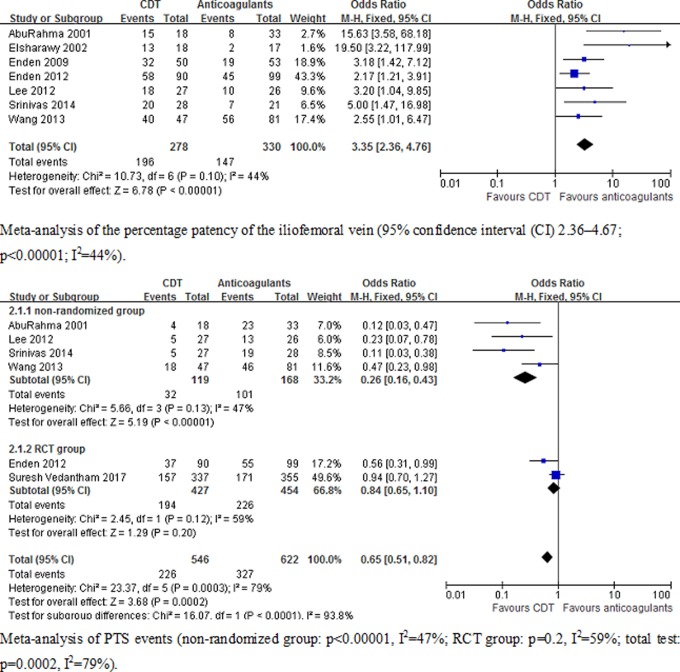

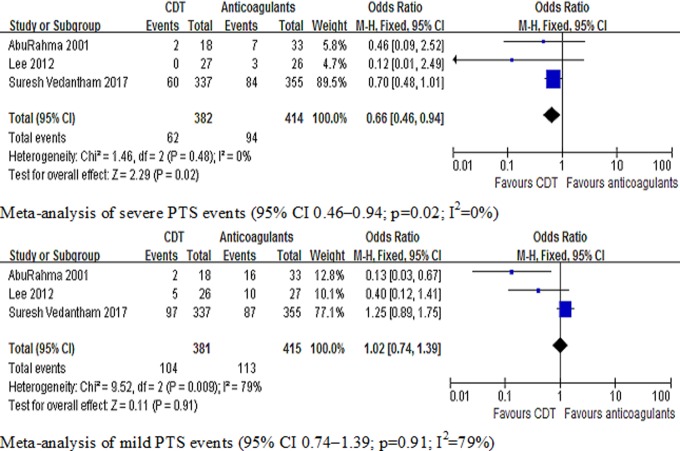

Primary and secondary outcomes are shown in Table 2. Seven studies7–10,12,13,15,16 included the results of the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein, and 6 studies 7–9,13,15,16 included the results of PTS. Meta-analysis indicated that CDT can increase the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.36-4.67; P < .00001; I 2 = 44%) and reduce the risk of PTS (95% CI 0.51-0.82; P = .0002; I 2 = 78%) compared with anticoagulant. In the anticoagulant group, the number of patients was less than the CDT group on iliofemoral vein patency. In CDT group, the number of PTS was less than that in the anticoagulant group. When we input data in Review Manager, the data of patency and PTS on figure 2 showed that CI was on the side of smaller data. It explained that the tendency of CI of patency and PTS on reverse direction in figure 2. The graph revealed that the number of patients on iliofemoral vein patency decreased significantly in the anticoagulant group, the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein favoring the CDT group. We found that heterogeneity of PTS events was high (I 2 = 78%), suggesting the need to explore heterogeneity sources. We divided PTS events into 2 types: RCT group (the Catheter-Directed Venous Thrombolysis in Acute Iliofemoral Vein Thrombosis [CAVENT] and Acute Venous Thrombosis: Thrombus Removal With Adjunctive Catheter-Directed Thrombolysis [ATTRACT] trial), in which literature quality was high, and nonrandomized studies, in which the sample size of patients and follow-up time was lower than RCT group. Subgroup analysis demonstrated that CDT did not prevent PTS in RCTs group (95% CI 0.65-1.10; P = .2; I 2 = 59%). A reduced risk of PTS was shown, however, in nonrandomized trials (95% CI 0.16-0.43; P < .00001; I 2 = 47%). Figure 2 is the meta-analysis of the primary outcomes. Two studies8,13 and the ATTRACT study stratified according to the prevention of severe versus mild PTS. Meta-analysis indicated that CDT can reduce the risk of severe PTS (95% CI 0.46-0.94; P = .002; I 2 = 0%). However, CDT was not shown to prevent mild PTS compared to anticoagulant group (95% CI 0.74-1.39; P = .91; I 2 = 79%). Figure 3 shows the meta-analysis of PTS classification.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes in Clinical Trials.

| Study | Group | Iliofemoral Patency | PTS | Bleeding | Death | PE | Duration of Hospital Stay, days | Recurrent VTE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enden12 | CDT+AC | 32 (64%) | NA | 10 (20%) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| AC | 19 (35%) | NA | 2 (4%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Riyaz14 | CDT+AC | NA | NA | 177 (49%) | 42 (1%) | 642 (18%) | 7.23 ± 5.8 | NA |

| AC | NA | NA | 88 (24%) | 31 (0.8%) | 408 (11%) | 5.02 ± 4.67 | NA | |

| Elsharawy10 | CDT+AC | 13 (72%) | NA | NA | 0 | 0 | 7 | NA |

| AC | 2 (12%) | NA | NA | 0 | 1 (6%) | 5.5 | NA | |

| Wang9 | CDT+AC | 40 (85%) | 18 (38%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| AC | 56 (69%) | 46 (57%) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| Srinivas16 | CDT+AC | 20 (71%) | 5 (19%) | 4 (15%) | 2 (7%) | 4 (15%) | 5 ± 1.3 | NA |

| AC | 7 (33%) | 19 (68%) | 0 | 2 (7%) | 6 (21%) | 4.8 ± 1.4 | NA | |

| Yevgeniy17 | CDT+AC | NA | NA | NA | 14 (3%) | NA | 9.97 ± 9.1 | NA |

| AC | NA | NA | NA | 8 (2%) | NA | 6.83 ± 5.5 | NA | |

| AbuRahma13 | CDT+AC | 15 (83%) | 4 (22%) | 5 (28%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | NA | NA |

| AC | 8 (24%) | 23 (70%) | 5 (15%) | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | |

| Enden7 | CDT+AC | 58 (64%) | 37 (41%) | 20 (22%) | NA | NA | NA | 10 (11%) |

| AC | 45 (45%) | 55 (56%) | 0 | NA | NA | NA | 18 (18%) | |

| Lee8 | CDT+AC | 18 (67%) | 5 (19%) | 8 (30%) | NA | NA | NA | 1 (4%) |

| AC | 10 (39%) | 13 (50%) | 5 (19%) | NA | NA | NA | 2 (7%) | |

| Suresh15 | CDT+AC | NA | 157 (47%) | 15 (45%) | NA | NA | NA | 42 (12%) |

| AC | NA | 171 (48%) | 6 (17%) | NA | NA | NA | 30 (8%) |

Abbreviations: AC, anticoagulant; CDT, catheter-directed thrombolysis; NA, not available; PE, pulmonary embolism; PTS, postthrombotic syndrome; VTE, venous thrombus embolism.

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of primary outcomes of clinical trials (patency of the iliofemoral vein 95% CI 2.36-4.67; risk for PTS 95% CI 0.51-0.82). CI indicates confidence interval; PTS, postthrombotic syndrome.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of the classification of PTS (risk for severe PTS 95% CI 0.46-0.94; risk for mild PTS 95% CI 0.74-1.39). CI indicates confidence interval; PTS, postthrombotic syndrome.

Secondary Outcomes

Seven articles7,8,12-16 had data about bleeding events. Bleeding events included both small and major bleeding events. A statistically significant increase in bleeding events (95% CI 1.91–3.04; P < .00001; I 2=33%) was reported, and heterogeneity was low (I 2 < 50%), suggesting that the risk of bleeding was high in the CDT group. Four articles10,13,14,16 contain data about PE events. The rates of PE events were statistically significant, increasing in CDT (95% CI 1.47-1.92; P < .00001; I 2 = 14%). There was no significant difference in death (95% CI 0.95-2.13; P = .09; I 2 = 0%) and recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) events (95% CI 0.76-1.72; P = .52; I 2 = 58%). Figure 4 shows the meta-analysis of adverse events (bleeding, PE, recurrent VTE, and death).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of adverse events (secondary outcomes) of clinical trials (bleeding events 95% CI 1.91-3.04; PE events 95% CI 1.47-1.92; death 95% CI 0.95-2.13; recurrent VTE 95% CI 0.76-1.72). CI indicates confidence interval; PE, pulmonary embolism; VTE, venous thrombus embolism.

Four articles10,14,16,17 included data about the duration of stay in the hospital, and 2 articles14,17 had data about hospital charges. Also, in the CDT group, the duration of hospital stay was significantly prolonged compared to the anticoagulant alone group (95% CI 0.37-0.46; P < .00001; I 2 = 0%), and hospital charges were also higher in the CDT group (95% CI 0.86-1.07; P < .00001; I 2 = 43%). Figure 5 shows the meta-analysis of the duration of hospital stay and hospital charges.

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of duration of hospital stay and hospital charges (secondary outcomes) of clinical trials (duration in hospital 95% CI 0.37-0.46; hospital charges 95% CI 0.86-1.07). CI indicates confidence interval.

Discussion

Anticoagulation alone was not associated with the dissolving of venous thrombus, leading to chronic venous dysfunction in patients with DVT.18 Systemic thrombolytic therapy was also abandoned because of high risk of bleeding events and inefficiency in removing thrombus.19 Therefore, CDT has been developed for dissolving thrombus in patients with acute lower extremity DVT. Compared with systemic thrombolytic or anticoagulation alone therapy, CDT plus anticoagulation therapy was demonstrated as more effective for dissolving venous thrombus.20 However, in the recent guidelines for acute proximal DVT of the leg, anticoagulant treatment alone is still recommended over CDT, and the evidence grade is not high (2C).21 Thus, CDT therapy for acute lower extremity DVT remains controversial. In the past few years, there has been a number of clinical studies about CDT for acute lower extremity DVT and assessing the treatment effects.22–25 Our meta-analysis, based on 4 RCTs and 6 comparative studies, compared CDT plus anticoagulation with anticoagulation alone for the therapeutic of acute lower extremity DVT.

Seven studies (3 RCTs and 4 non-RCTs)7–10,12,13,16 included the result of the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein. The 6-month follow-up of the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein in 6 studies and 1 study (CAVENT trial)7 follow-up was 24 months, revealing that rapidly eliminated iliofemoral vein thrombus could improve iliofemoral vein flow. Because CDT thepary was used in acute phase and meta-analysis revealed that CDT can increase the percentage patency of the iliofemoral vein. Moreover, this finding calls attention to prior research that has shown that 20% of patients with lower limb DVT having iliofemoral position thrombus may be recanalized independently without intravenous thrombolysis or CDT after 5-year follow-up.26 Furthermore, 5 studies (1 RCT and 4 non-RCTs)7,8,9,13,16 revealed that CDT was effective in reducing the morbidity rate of PTS. However, the 2-year results from the ATTRACT study demonstrated that CDT could not prevent PTS. Although there were few RCTs in this meta-analysis, the results of percentage patency of iliofemoral vein heterogeneity were not high (I 2 = 44%), and the incidence of PTS was statistically significant (P = .00002, I 2 = 79%). Because the heterogeneity of PTS events was high (I 2 > 75%), the result was not convincing, thereby promoting the need to explore the heterogeneity. For subgroup analysis, we found that CDT did not prevent PTS in the RCT group (the CAVENT and ATTRACT trial; P = .2; I 2 = 59%), and the sample size of patients (>100) and follow-up time (24 months) were high compared to the nonrandomized group. In sum, quality, sample size, and follow-up time may have affected the meta-analysis results of PTS events.

Two studies8,13 and the ATTRACT study stratified according to the prevention of severe versus mild PTS. However, 3 studies did not have uniform standard definition for the grade of PTS. The Lee et al8 study didn’t report on the method that was used to classify PTS. The ATTRACT study used Villalta score to classify PTS, and the AbuRahma et al13 study used clinical, etiologic, anatomic, pathophysiologic measures to stratify PTS. In the future, more RCTs should assess the severity of PTS using the Villalta scale and record the Villalta score in the study. Meta-analysis indicated that CDT could reduce the severity of PTS (P = .002; I 2 =0 %). Patients’ quality of life and early DVT symptoms may be improved by CDT therapy. However, CDT was not shown to prevent mild PTS (P = .91; I 2 = 79%). The occurrence of PTS was still debatable in CDT therapy. The CDT therapy for patients with acute iliofemoral DVT in the acute stage can significantly improve the patency rate of deep venous and prevent venous refluence in the early stage. However, for long-term follow-up, CDT therapy to prevent PTS remains controversial, and more high-quality, multiple-center, large-sample RCTs are needed.

Adverse events included bleeding, PE, recurrent VTE events, and death. In our meta-analysis, we showed that bleeding and PE events were significantly higher in the CDT group (P < .00001, I 2 = 33%; P .00001; I 2 = 14%), and there were no significant differences in death and recurrent VTE between the CDT and anticoagulation groups (P = .09, I 2 = 0%; P = .52, I 2 = 58%). Data analysis also demonstrated that the heterogeneity of the results was low. Bleeding can be major and minor. With CDT therapy, most bleeding complications happened in the puncture site, and the severe bleeding events (eg, intracranial hemorrhage) were a small minority.27 Additionally, many factors caused bleeding, such as the (older) age of the patients, dosage of thrombolytics or anticoagulants, history of bleeding, the duration of thrombolysis or anticoagulation therapy and so on.

For patients with a relatively high risk of bleeding, CDT therapy should be implemented through careful consideration of a comprehensive benefit-to-risk assessment.28 Moreover, adept operative technique for CDT endovascular therapy may decrease the incidence rate of puncture-related bleedings events. Four studies10,13,14,16 demonstrated that PE was significantly increased in the CDT group. However, among these 4 studies, the sample size of the Bashir et al study14 was significantly larger than that of the other studies; sample size may be an important factor influencing the statistical results of PE events. In addition, the other 3 aforementioned studies included symptomatic PE events, while the Bashir et al14 study did not illustrate PE events with clinical symptoms. For sensitivity analysis, the Bashir et al study was excluded from statistical assessment, and symptomatic PE events showed no significant difference between the CDT and anticoagulation groups (P = .71; I 2 = 0%). Irrespective of the CDT group or the anticoagulation group, the total mortality was low, and death was primarily from PE and intracranial hemorrhage. Therefore, preventive measures (such as implantation of vena cava filter) against PE and intracranial hemorrhage should perhaps receive more attention during CDT or anticoagulation therapy.

We found that the duration of hospital stay was significantly longer (P < .00001; I 2 = 0%), and hospital charges were also higher in the CDT group (P < .00001; I 2 = 43%). The charges for endovascular therapy and the longer duration of hospital stay may increase the economic burden of patients without health insurance. However, the expense may be worthwhile if CDT therapy could improve the patency of the iliofemoral vein, reduce the incidence of PTS, and produce no severe bleeding or PE events.

Catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation therapy could provide a safe and effective method for removing venous thrombosis in patients with acute iliofemoral DVT. After the acute phase, the duration of anticoagulation therapy should comply with the latest American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) guideline of antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease.21 The benefits of CDT were assessed using 3 major trials (the CAVENT trial, the ATTRACT trial, and the Catheter Versus Anticoagulation [CAVA] trial). The CAVENT trial was a multicenter, RCT that included 209 patients with acute DVT in the iliac, common femoral, and/or upper femoral vein. For this trial, data suggested that CDT improved the clinically relevant long-term outcome in iliofemoral DVT by reducing PTS compared with the conventional therapy with anticoagulation alone.

The ATTRACT study was a multicenter, randomized, assessor-blinded clinical trial in the United States. Whereas in the CAVENT study, conventional perfusion catheters were used; in the ATTRACT study, pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis (PCDT) was used. The much-anticipated 2-year results from the ATTRACT study were presented by Suresh Vedantham, MD, FSIR, on behalf of the trial’s investigators, at the 2017 SIR Annual Scientific Meeting. In the ATTRACT study, PCDT does not prevent the occurrence of PTS, and there was a slight increase in bleeding with the procedure. However, PCDT did reduce early DVT symptoms and the severity of PTS. The ATTRACT study stratified randomization based on whether the common femoral iliac was involved, thus the subgroup analyses enable insight into the differences between the risk–benefit ratio of lysing iliofemoral DVT versus femoral-only DVT. Although the trial did not show statistically significant differences between the subgroups, the patients who may be most likely to benefit are those with iliofemoral DVT; however, it was difficult to justify treating those with isolated femoropopliteal DVT. The inclusion of patients with only a femoropopliteal DVT who still have good outflow through the common femoral vein could influence the outcome negatively, as conservative treatment in these patients is not expected to perform poorly.

Furthermore, the Dutch CAVA trial is an ongoing RCT for CDT therapy compared with anticoagulation therapy alone. The data from CAVA trial may give more clinical evidence for CDT versus anticoagulation therapy. Nevertheless, the risk–benefit ratio for patients with DVT must be considered before any therapeutic protocol is clinically implemented.

Our meta-analysis had limitations. Six non-RCTs were included in this meta-analysis, and the quality of literature was not high. Thus, the data from the non-RCTs may influence the statistical results of the meta-analysis. Although the heterogeneity of most primary and secondary outcomes was not high, we did not carefully explore the sources of heterogeneity. Also, the literature quality, sample size of the studies, and follow-up time may be important factors affecting the results of the meta-analysis, and we did not rule out the other sources of heterogeneity like age, body surface area, race, usage of iliac stenting and different drugs for thrombolysis, or anticoagulation. Similarly designed trials are required to reduce heterogeneity and offer more convincing statistical data.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis demonstrated that CDT improved the patency of the iliofemoral vein or the severity of PTS compared with anticoagulation therapy alone, while demonstrating that PTS incidence remains debatable. However, substantially more bleeding and PE events occurred in the CDT group. The average duration of hospital stay was also higher in the CDT group compared with the anticoagulation therapy group.

Footnotes

Authors’ Note: This article does not include studies involving human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was funded by Project of Scientific Research of Luqiao District, Tai Zhou Science and Technology Agency (grant number 2016A23004).

References

- 1. Lee CH, Cheng CL, Lin LJ, Tsai LM, Yang YH. Epidemiology and predictors of short-term mortality in symptomatic venous thromboembolism. Circ J. 2011;75(8):1998–2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kahn SR. The post-thrombotic syndrome: progress and pitfalls. Br J Haematol. 2006;134(4):357–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kahn SR, Elman EA, Bornais C, Blostein M, Wells PS. Post-thrombotic syndrome, functional disability and quality of life after upper extremity deep venous thrombosis in adults. Thromb Hemost. 2005;93(3):499–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Amin VB, Lookstein RA. Catheter-directed interventions for acute iliocaval deep vein thrombosis. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2014;17(2):96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guanella R, Ducruet T, Johri M, et al. Economic burden and cost determinants of deep vein thrombosis during 2 years following diagnosis: a prospective evaluation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(12):2397–2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD002783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Enden T, Haig Y, Klow NE, et al. Long-term outcome after additional catheter-directed thrombolysis versus standard treatment for acute iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis (the CaVenT study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9810):31–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lee CY, Lai ST, Shih CC, Wu TC. Short-term results of catheter-directed intrathrombus thrombolysis versus anticoagulation in acute proximal deep vein thrombosis. J Chin Med Assoc. 2013;76(5):265–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang ZH, Shan Z, Wang WJ, Li XX, Wang SM. Outcome comparisons of anticoagulation, systematic thrombolysis and catheter-directed thrombolysis in the treatment of lower extremity acute deep venous thrombosis. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2013;93(29):2271–2274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Elsharawy M, Elzayat E. Early results of thrombolysis vs anticoagulation in iliofemoral venous thrombosis. A randomised clinical trial. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002. 24(3):209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, Demers L, Momoli F, Moride Y. Interrater reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer’s disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001;12(3):232–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Enden T, Klow NE, Sandvik L, et al. Catheter-directed thrombolysis vs. anticoagulant therapy alone in deep vein thrombosis: results of an open randomized, controlled trial reporting on short-term patency. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7(8):1268–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. AbuRahma AF, Perkins SE, Wulu JT, Ng HK. Iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: conventional therapy versus lysis and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting. Ann Surg. 2001;233(6):752–760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bashir R, Zack CJ, Zhao H, Comerota AJ, Bove AA. Comparative outcomes of catheter-directed thrombolysis plus anticoagulation vs anticoagulation alone to treat lower-extremity proximal deep vein thrombosis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(9):1494–1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The 2017 Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) Annual Scientific Meeting. Report on the much-anticipated 2-year results from the ATTRACT study. Washington DC,USA: Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR) Annual Scientific Meeting; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Srinivas BC, Patra S, Nagesh CM, Reddy B, Manjunath CN. Catheter-directed thrombolysis along with mechanical thromboaspiration versus anticoagulation alone in the management of lower limb deep venous thrombosis—A comparative study. Int J Angiol. 2014;23(4):247–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Brailovsky Y, Lakhter V, Zack C, Gaughan J, Bove A.&Bashir R. Comparative outcomes of catheter–directed thrombolysis with anticoagulation versus anticoagulation alone in cancer patients with deep venous thrombosis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 61(10): E2073): E2073. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Comerota AJ. Thrombolysis for deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(2):607–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Watson L, Broderick C, Armon MP. Thrombolysis for acute deep vein thrombosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;11:CD002783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liew A, Douketis J. Catheter-directed thrombolysis for extensive iliofemoral deep vein thrombosis: review of literature and ongoing trials. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2016;14(2):89–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(2):315–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Broholm R, Just S, Jorgensen M, Baekgaard N. Acute iliofemoral deep venous thrombosis should be treated with catheter-directed thrombolysis. Ugeskr Laeger. 2012;174(14):930–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sharifi M, Bay C, Nowroozi S, Bentz S, Valeros G, Memari S. Catheter-directed thrombolysis with argatroban and tPA for massive iliac and femoropopliteal vein thrombosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radio. 2013;36(6):1586–1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Goktay AY, Senturk C. Endovascular treatment of thrombosis and embolism. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;906:195–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Che H, Zhang J, Sang G, Yong J, Li L, Yang M. Popliteal vein puncture technique based on bony landmark positioning in catheter-directed thrombolysis of deep venous thrombosis: a retrospective review. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;35:104–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baekgaard N. Benefit of catheter-directed thrombolysis for acute iliofemoral DVT: myth or reality? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2014;48(4):361–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Broholm R, Panduro L, Baekgaard N. Catheter-directed thrombolysis in the treatment of iliofemoral venous thrombosis. A review. Int Angiol. 2010;29(4):292–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin PH, Ochoa LN, Duffy P. Catheter-directed thrombectomy and thrombolysis for symptomatic lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis: review of current interventional treatment strategies. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2010;22(3):152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]