Abstract

Purpose:

Hyperglycemia affects FDG uptake in the brain, potentially emulating Alzheimer’s disease in normal individuals. This study investigates global and regional cerebral FDG uptake as a function of plasma glucose in a cohort of patients.

Methods:

120 consecutive male patients with FDG PET/CT for initial oncologic staging (July-Dee 2015) were reviewed. Patients with dementia, cerebrovascular accident, structural brain lesion, prior oncology treatment or high metabolic tumor burden (recently shown affecting brain FDG uptake) were excluded. 53 (24 nondiabetic) eligible patients (age 65.7 ± 2.8 mean ± SE) were analyzed with parametric computer software, MIMneuro™. Regional Z-scores were evaluated as a function of plasma glucose and age using multi variable linear mixed effects models with false discovery analysis adjusting for multiple comparisons. If the regression slope was significantly (p < 0.05) different than zero, hyperglycemia effect was present.

Results:

There was a negative inverse relationship (p < 0.001) between global brain FDG uptake and hyperglycemia. No regional hyperglycemia effect on uptake were present when subjects were normalized using pons or cerebellum. However, regional hyperglycemia effects were seen (p < 0.047–0.001) when normalizing by the whole brain. No obvious pattern was seen in the regions affected. Age had a significant effect using whole brain normalization (p < 0.04–0.01).

Conclusions:

Cortical variation in FDG uptake were identified when subjects were hyperglycemic. However, these variations didn’t fit a particular pattern of dementia and the severity of the affect is not likely to alter clinical interpretation.

Keywords: Regional cerebral FDG uptake, Nondiabetic patients, FDG uptake in hyperglycemia, Misdiagnosis of dementia

1. Introduction

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) brain PET/CT for dementia evaluation is increasingly utilized with specific patterns of cortical FDG uptake and distribution useful to distinguish Alzheimer’s disease (AD) from other forms of dementia, particular frontotemporal dementia and dementia with Lewy bodies [1]. Computer-assisted diagnosis using quantitative parametric software has further enhanced diagnostic accuracy and improved interobserver agreement and novice reader training [1,2]. FDG, as an analog substrate of glucose, is accumulated in organs/tissues at different rates dependent on relative FDG/glucose availability, underlying cellular metabolism and the fasting state/insulin milieu at the time of imaging. The patient’s fasting state/insulin milieu is considered to have less impact on brain PET imaging as cerebral Glut-1 and 3 receptors are relatively insensitive to insulin [3,4]. However, several authors have established that higher levels of hyperglycemia can result in global reduction in cerebral FDG uptake, presumably due to competitive inhibition of the Glut-1 and 3 transporter and/or hexokinase [5–7]. Although this effect was not presumed to have geographic variation in the brain, Ishibashi et al. have suggested that even mild levels of hyperglycemia (glucose >125 mg/ dL) in normal subjects can result in patterns of FDG uptake that emulate patterns seen in AD, specifically decreased FDG uptake preferentially found in the precuneus/posterior cingulate, lateral parietal cortex and frontal cortex [8]. These results, if independently confirmed would suggest that there are regional differences in the brain, perhaps due to varying ratio of Glut-1 or 3 receptor/hexokinase expression and activity, with implications for guidelines on brain PET/CT imaging of dementia [9].

Our goal was to retrospectively evaluate effects of plasma glucose levels on regional brain FDG uptake, in a cohort of patients with initial oncologic PET/CT. We treated plasma glucose as a continuous function (instead of binary variable), using a commercially available computer-assisted diagnostic software. This software is used to assist clinical interpretation of brain FDG PET/CT brain using parametric statistical mapping in comparison to a database. We believe the results would translate to greater clinical environment were these software packages are employed in assisting the evaluation of brain FDG PET/CT scans.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient selection

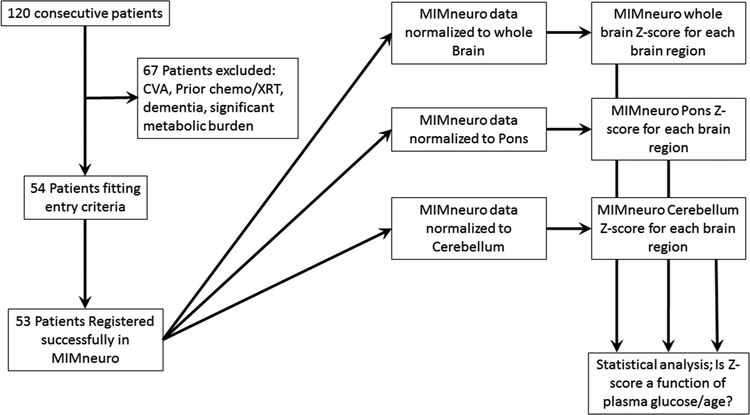

Consecutive patients (n = 120) were reviewed with patient demographic factors including: age, gender, primary tumor type, medications (in particular those known to affect glucose metabolism or neural activity), metabolic disease (thyroid disorders, etc.), body mass index (BMI, kg/m2), injected FDG dose and time intervals between glucose measurements/FDG administration and initiation of subsequent imaging. Patients were excluded if they had recently taken diabetes medications or if blood glucose was above 250mg/dL per our clinical protocol. Patients were also excluded if the reason for the PET/CT was neurodegenerative disease evaluation, history or suspected history of dementia, territorial cerebral vascular accident (CVA) either noted in the medical record or depicted on the images, had prior cheomotherapy or radiation therapy, significant metabolic burden of disease which was recently shown to effect FDG uptake [10], or failure of image registration of the patient to the reference database (n = 1). This resulted in 53 patients that were evaluated with MIMneuro™. See Fig. 1 flow chart for experimental design.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the experimental design.

2.2. Image analysis

All patients had sequential PET and CT imaging performed on an integrated PET/CT scanner (Siemens Biograph T6; Siemens Medical Solutions, Hoffman Estates, IL, USA). Helical CT from skull vertex to mid-thigh was performed with 5 mm collimation, followed immediately by whole body PET at multiple overlapping bed positions.

For ROI image analysis FDG-PET/CT images were co-registered and reviewed on a workstation using software with fusion capability (Medlmage; MedView Pty, Canton, MI, USA). Attenuation corrected images using SUV measurements based on body weight (SUVkg) were used for regions of interest (ROI). ROI were drawn (B.L.V. Fellowship trained Abdominal Radiologist/Nuclear Medicine Physician 4yrs post clinical training) in the mediastinal blood pool of the ascending aorta/ aortic arch and bilateral basal ganglia at the level of the internal capsule as previously described [7]. Briefly, ROI’s were either circular/ ellipsoid to best fit the anatomy (largest circle to fit the ascending aorta arch, ~2cm dia.) to maximize measurement volume excluding vessel wall and/or atherosclerotic disease. For the basal ganglia, the largest ellipsoid (~4–6cm dia.) was placed that included the bilateral basal ganglia at the level of the internal capsule). The ROI basal ganglia was then plotted as a function of plasma glucose.

Subsequent PET/CT brain scans were reconstructed with a single bed position over the head and subsequently analyzed MIMneuro™ (MIM Software, Cleveland, OH 44122 USA ver.). MIMneuro software provided an associated Z-score (based on their internal database) for each of the defined regions. Additionally, MIMneuro™ allowed three different normalization techniques (whole brain, pons, and cerebellum), prior to region analysis. Registration of the patient images and segmentation were left to the original default setting of the software.

2.3. Data/Statistical analysis

The MIMneuro™ software packages, Z-score analysis was also performed using the internal data base. MIMneuro™ allowed 3 different methods of user selectable software normalization of raw patient FDG uptake data prior to comparison to the database; whole brain (83 regions), pons (82 regions) and cerebellum (82 regions). This resulted in one Z-score per region normalization. The Z-scores data was fitted with linear mixed effects models [11] using R statistical software, and the ImerTest R package. ImerTest: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 2.0–33. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package = ImerTest). We adjusted for plasma glucose, patient age and injected dose. We also performed the analysis adjusting the p-values for multiple region comparisons using the False Discovery Rate (FDR) method [12]. We assumed a fixed and random intercept and a fixed slope. We also attempted a mixed slope and mixed intercept model, however, the number of observations was less than the number of random effects and we were unable to fit the data with this model. All tests are two-sided tests and significance is assessed at the alpha = 0.05 level. All p-values have been adjusted for multiple comparisons using the False Discovery Rate method. There are wo requirements for the adjusted p-values. One, is that they are monotone increasing with the sorted p-values. Two, is that the lie between 0 and 1. It turns out neither of these are always met in practice. If either is violated, the adjusted p-value is assigned the previous (sorted) adjusted p-value [12,13]. In the cases herein, all but one p-value was less than one. A statistically significant effect was considered present if the slope of the linear regression was significantly (p < 0.05) different from zero.

Demographic data was analyzed using student t-test, with p < 0.05 considered statistically different between patients with and without diabetes.

3. Results

The demographic data for the analyzed patients is shown in Table 1. From these demographics, the only significant difference with the plasma glucose was between patients with and without diabetes, with the latter being higher as expected at the time of imaging.

Table 1.

Glucose levels in our population of nondiabetic and diabetic patients. Patients’ characteristics.

| Patient Demographics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Patients (n = 53) Average ± SE | Nondiabetic (n = 24) Average ± SE | Diabetic (n = 29) Average ± SE | P-value | |

| Age (yrs) | 67.3 ± 1.29 | 60.8 ± 4.31 | 65.7 ± 2.79 | 0.325 |

| BMI | 27.8 ± 0.73 | 25.4 ± 1.03 | 28.8 ± 1.33 | 0.056 |

| Glucose (mg/dl) | 128.4 ± 5.6 | 103.0 ± 6.24 | 149.5 ± 6.87 | <0.0001 |

| Dose (mCi) | 12.8 ± 0.16 | 12.7 ± 0.184 | 12.8 ± 0.25 | 0.765 |

| Glucose to Imaging Time (min) | 71.7 ± 1.54 | 71.5 ± 1.62 | 71.8 ± 2.51 | 0.928 |

| FDG injection to Imaging Time (min) | 62.3 ± 1.34 | 63.5 ± 0.82 | 61.3 ± 2.35 | 0.411 |

| Glucose to Injection time (min) | 9.4 ± 1.12 | 8.0 ± 1.23 | 10.5 ± 1.77 | 0.267 |

| Tumor Type | ||||

| Lung | 24 | 12 | 12 | |

| SCCA | 5 | 2 | 3 | |

| ESO | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Lymph | 5 | 3 | 2 | |

| Other | 13 | 4 | 9 |

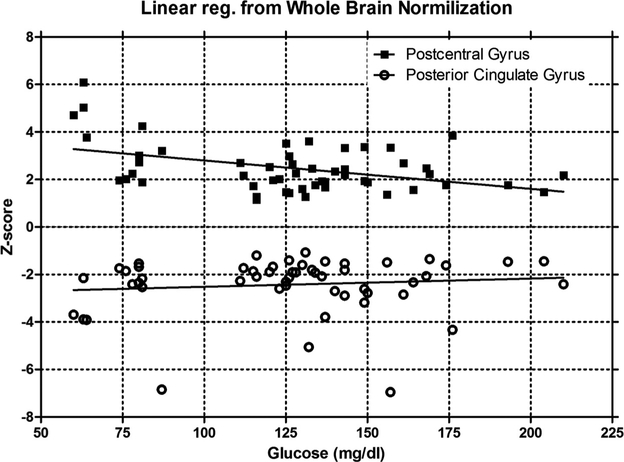

The Z-score analysis from MIMneuro on the effect of glucose and age are shown in Tables 2 and 3, respectively, and graphically in Fig. 2 for the whole brain normalization of the postcentral gyrus and posterior cingulate gyrus. Only regions that were statistically significant with a P < 0.05 using the FDR adjusted analysis or simple multivariate regression analysis (unadjusted analysis) are shown in the tables for clarity. Additionally, the pons and cerebellum were shown along with regions presumed to be involved in Alzheimer’s. (The complete result for all regions is shown in supplementary data/upon request). In addition to the significant regions being shown, the Basis Pontis and Cerebellar Hemisphere are also shown as they relate to the regions used for normalization other than whole brain.

Table 2.

Glucose analysis.

| Normalization Method | Whole Brain Normalization Method | Cerebellum Normalization Method | Pons Normalization Method | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Volume (cc) | % Volume | Slope (Z-score/ mg/dL glucose) | STE | Unadjusted p-values | FDR Adjusted p-values | Slope (Z-score/ mg/dL glucose) | STE | Unadjusted p-values | FDR Adjusted p-values | Slope (Z-score/ mg/dL glucose) | STE | Unadjusted p-values | FDR Adjusted p-values |

| Basis Pontis 8/10 | 8.36 | 0.50% | 0.003 | 0.002 | 0.168 | 0.269 | 5.00E-04 | 0.003 | 0.865 | 0.909 | ||||

| Cerebellar Hemisphere | 116.3 | 6.96% | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.739 | 0.876 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.143 | 0.226 | ||||

| 8/10 | ||||||||||||||

| Amygdala | 4.1 | 0.2% | −0.015 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.011 | 0.007 | 0.114 | 0.534 | −0.010 | 0.006 | 0.090 | 0.224 |

| Globus Pallidus | 5.3 | 0.3% | −0.006 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.047 | −0.008 | 0.006 | 0.179 | 0.534 | −0.011 | 0.005 | 0.054 | 0.224 |

| Hippocampus 8/10 | 5.1 | 0.3% | −0.013 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.010 | 0.006 | 0.124 | 0.534 | −0.009 | 0.007 | 0.204 | 0.274 |

| Inferior Occipital | 18.0 | 1.1% | −0.005 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.045 | −0.008 | 0.006 | 0.164 | 0.534 | −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.046 | 0.224 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Inferior Temporal | 47.1 | 2.8% | −0.016 | 0.004 | 0.000 | 0.002 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.194 | 0.534 | −0.011 | 0.005 | 0.038 | 0.224 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Medial Temporal Lobe | 16.6 | 1.0% | −0.005 | 0.002 | 0.007 | 0.048 | −0.008 | 0.006 | 0.151 | 0.534 | −0.011 | 0.006 | 0.055 | 0.224 |

| 8/10 | ||||||||||||||

| Middle Orbital Gyrus | 16.5 | 1.0% | −0.006 | 0.002 | 0.005 | 0.045 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.186 | 0.534 | −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.046 | 0.224 |

| Parietal Lobe | 341.8 | 20.5% | −0.007 | 0.002 | 0.004 | 0.042 | −0.005 | 0.005 | 0.282 | 0.534 | −0.009 | 0.005 | 0.064 | 0.224 |

| Precentral Gyrus | 60.8 | 3.6% | −0.010 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.004 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.258 | 0.534 | −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.054 | 0.224 |

| Postcentral Gyrus | 68.7 | 4.1% | −0.016 | 0.003 | 0.000 | 0.001 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.204 | 0.534 | −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.049 | 0.224 |

| Posterior Cingulate | 19.81 | 1.19% | 0.006 | 0.005 | 0.222 | 0.341 | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.971 | 0.971 | −0.003 | 0.004 | 0.434 | 0.468 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Posterior Cingulate | 12.85 | 0.77% | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.300 | 0.401 | −0.001 | 0.003 | 0.826 | 0.880 | −0.004 | 0.004 | 0.361 | 0.400 |

| Gyrus 8/10 | ||||||||||||||

| Precuneus | 59.31 | 3.55% | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.970 | 0.973 | −0.005 | 0.004 | 0.289 | 0.534 | −0.007 | 0.005 | 0.140 | 0.226 |

| Angular Gyrus | 75.2 | 4.5% | −0.004 | 0.001 | 0.014 | 0.066 | −0.005 | 0.005 | 0.282 | 0.534 | −0.009 | 0.005 | 0.081 | 0.224 |

| Hippocampus | 9.8 | 0.6% | −0.005 | 0.002 | 0.010 | 0.052 | −0.008 | 0.006 | 0.153 | 0.534 | −0.011 | 0.006 | 0.064 | 0.224 |

| Posterior Orbital | 6.7 | 0.4% | −0.003 | 0.001 | 0.035 | 0.146 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.242 | 0.534 | −0.010 | 0.005 | 0.055 | 0.224 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Superior Frontal Gyrus | 79.7 | 4.8% | −0.004 | 0.002 | 0.013 | 0.061 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.263 | 0.534 | −0.009 | 0.005 | 0.063 | 0.224 |

| Superior Parietal | 70.7 | 4.2% | −0.004 | 0.001 | 0.010 | 0.052 | −0.006 | 0.005 | 0.236 | 0.534 | −0.009 | 0.005 | 0.073 | 0.224 |

| Lobule | ||||||||||||||

| Supramarginal Gyrus | 46.2 | 2.8% | −0.004 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.052 | −0.005 | 0.005 | 0.295 | 0.534 | −0.009 | 0.005 | 0.064 | 0.224 |

Table 3.

Age analysis.

| Normalization Method | Whole Brain Normalization Method | Cerebellum Normalization Method | Pons Normalization Method | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structure | Volume (cc) | % Volume | Slope (Z-score/year) | STE | Unadjusted p-FDR values Adjusted p values | Slope (Z-STE score/year) | Unadjusted p-FDR values Adjusted p values | Slope (Z-score/year) | STE | Unadjusted p-FDR Adjusted values p-values | ||||

| Basis Pontis 8/10 | 8.36 | 0.5% | −0.021 | 0.010 | 0.054 | 0.110 | −0.017 | 0.014 | 0.213 | 0.993 | ||||

| Cerebellar Hemisphere 8/10 | 116.3 | 7.0% | −0.003 | 0.007 | 0.695 | 0.721 | −0.002 | 0.020 | 0.913 | 0.985 | ||||

| Amygdala | 4.1 | 0.2% | 0.053 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.039 | 0.029 | 0.187 | 0.993 | 0.038 | 0.025 | 0.136 | 0.985 |

| Amygdala 8/10 | 2.0 | 0.1% | 0.033 | 0.012 | 0.011 | 0.040 | 0.026 | 0.028 | 0.359 | 0.993 | 0.027 | 0.025 | 0.284 | 0.985 |

| Cuneus | 32.3 | 1.9% | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.039 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.979 | 0.993 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.808 | 0.985 |

| Frontal Lobe | 576.9 | 34.5% | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.034 | −0.001 | 0.020 | 0.955 | 0.993 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.825 | 0.985 |

| Hippocampus 8/10 | 5.1 | 0.3% | 0.041 | 0.013 | 0.002 | 0.034 | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.248 | 0.993 | 0.050 | 0.030 | 0.108 | 0.985 |

| Inferior Medial Frontal | 16.4 | 1.0% | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.040 | −0.002 | 0.020 | 0.930 | 0.993 | 0.006 | 0.021 | 0.786 | 0.985 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Inferior Occipital Gyrus | 18.0 | 1.1% | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.070 | 0.019 | 0.026 | 0.471 | 0.993 | 0.011 | 0.022 | 0.634 | 0.985 |

| Inferior Temporal | 47.1 | 2.8% | 0.072 | 0.016 | 0.000 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.024 | 0.694 | 0.993 | 0.017 | 0.023 | 0.455 | 0.985 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Lateral Orbital Gyrus | 19.8 | 1.2% | 0.016 | 0.005 | 0.003 | 0.034 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.993 | 0.993 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.973 | 0.998 |

| Medial Orbital Gyrus | 23.9 | 1.4% | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.040 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.966 | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.742 | 0.985 |

| Medial Temporal Lobe | 26.6 | 1.6% | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.039 | 0.002 | 0.022 | 0.922 | 0.993 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.434 | 0.985 |

| Middle Frontal Gyrus | 102.9 | 6.2% | 0.013 | 0.005 | 0.012 | 0.042 | −0.001 | 0.020 | 0.960 | 0.993 | −0.003 | 0.020 | 0.897 | 0.985 |

| Occipital Lobe | 225.7 | 13.5% | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.040 | 0.000 | 0.020 | 0.990 | 0.993 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.855 | 0.985 |

| Orbitofrontal Region | 60.2 | 3.6% | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.010 | 0.040 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.902 | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.736 | 0.985 |

| Paracentral Lobule | 22.8 | 1.4% | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.010 | 0.040 | −0.001 | 0.020 | 0.968 | 0.993 | 0.004 | 0.021 | 0.869 | 0.985 |

| Parahippocampal | 7.1 | 0.4% | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.039 | 0.000 | 0.021 | 0.992 | 0.993 | 0.013 | 0.022 | 0.567 | 0.985 |

| Gyrus 8/10 | ||||||||||||||

| Pontine Tegmentum | 5.0 | 0.3% | 0.027 | 0.010 | 0.010 | 0.040 | 0.051 | 0.031 | 0.101 | 0.993 | 0.039 | 0.027 | 0.147 | 0.985 |

| Postcentral Gyrus | 68.7 | 4.1% | 0.055 | 0.014 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 0.010 | 0.023 | 0.663 | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.747 | 0.985 |

| Posterior Orbital Gyrus | 6.7 | 0.4% | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 0.039 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.790 | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.756 | 0.985 |

| Precentral Gyrus | 60.8 | 3.6% | 0.030 | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0.040 | 0.005 | 0.022 | 0.819 | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.022 | 0.732 | 0.985 |

| Precuneus 8/10 | 29.7 | 1.8% | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.008 | 0.040 | −0.002 | 0.020 | 0.934 | 0.993 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.911 | 0.985 |

| Superior Occipital | 35.4 | 2.1% | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.004 | 0.039 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.884 | 0.993 | 0.006 | 0.021 | 0.764 | 0.985 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Supplementary Motor | 65.5 | 3.9% | 0.015 | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.039 | −0.001 | 0.021 | 0.969 | 0.993 | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.905 | 0.985 |

| Area | ||||||||||||||

| Posterior Cingulate | 19.81 | 1.19% | −0.040 | 0.020 | 0.051 | 0.109 | −0.015 | 0.014 | 0.289 | 0.993 | −0.005 | 0.019 | 0.800 | 0.985 |

| Gyrus | ||||||||||||||

| Posterior Cingulate | 12.85 | 0.77% | −0.029 | 0.017 | 0.095 | 0.146 | −0.015 | 0.014 | 0.309 | 0.993 | −0.005 | 0.019 | 0.811 | 0.985 |

| Gyrus 8/10 | ||||||||||||||

| Precuneus | 59.31 | 3.55% | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.160 | 0.207 | −0.002 | 0.019 | 0.929 | 0.993 | −0.001 | 0.020 | 0.970 | 0.998 |

| Angular Gyrus | 75.2 | 4.5% | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.027 | 0.074 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.956 | 0.993 | 0.005 | 0.021 | 0.826 | 0.985 |

| Anterior Cingulate Gyrus | 22.6 | 1.4% | −0.027 | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.087 | −0.019 | 0.013 | 0.149 | 0.993 | −0.012 | 0.014 | 0.413 | 0.985 |

| Anterior Orbital Gyrus | 9.8 | 0.6% | 0.026 | 0.017 | 0.140 | 0.184 | 0.006 | 0.023 | 0.780 | 0.993 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.710 | 0.985 |

| Globus Pallidus | 5.3 | 0.3% | 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.027 | 0.074 | 0.020 | 0.027 | 0.453 | 0.993 | 0.017 | 0.024 | 0.473 | 0.985 |

| Hippocampus | 9.8 | 0.6% | 0.017 | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.080 | 0.017 | 0.025 | 0.510 | 0.993 | 0.019 | 0.024 | 0.439 | 0.985 |

| Medial Temporal Lobe

8/10 Parietal Lobe |

16.6 | 1.0% | 0.019 | 0.008 | 0.022 | 0.070 | 0.016 | 0.025 | 0.522 | 0.993 | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.508 | 0.985 |

| 341.8 | 20.5% | 0.022 | 0.010 | 0.030 | 0.076 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.939 | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.751 | 0.985 | |

| Superior Frontal Gyrus | 79.7 | 4.8% | 0.016 | 0.007 | 0.038 | 0.087 | 0.002 | 0.021 | 0.943 | 0.993 | 0.006 | 0.022 | 0.768 | 0.985 |

| Superior Parietal Lobule | 70.7 | 4.2% | 0.015 | 0.006 | 0.016 | 0.053 | 0.003 | 0.022 | 0.908 | 0.993 | 0.006 | 0.021 | 0.768 | 0.985 |

| Superior Temporal Gyrus | 67.5 | 4.0% | −0.024 | 0.011 | 0.027 | 0.074 | −0.013 | 0.015 | 0.411 | 0.993 | −0.007 | 0.019 | 0.727 | 0.985 |

| Supramarginal Gyrus | 46.2 | 2.8% | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.046 | 0.101 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.981 | 0.993 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 0.752 | 0.985 |

| Temporal Operculum | 6.0 | 0.4% | −0.025 | 0.011 | 0.024 | 0.074 | −0.013 | 0.014 | 0.357 | 0.993 | −0.005 | 0.019 | 0.802 | 0.985 |

Fig. 2.

Representative Z-score as a function of plasma glucose of all patients for the postcentral gyrus and posterior cingulate gyrus using brian normalization is shown. The postcentral gyrus dependence on plasma glucose is statistically significant (p = 0.001, R2 = 0.187) with a slope of −0.012 Z-score / glucose. Conversely, the posterior cingulate gyrus is not dependent on plasma glucose (p = 0.456, R2 = 0.011).

From Table 2, the regions of the brain that are effected by hyperglycemia constitute a small volume of the brain, individual less then ~4% with the exception of the parietal lobe, and are only seen using the whole brain normalization. Additionally, although glucose had a significant effect, this was limited to a slope of ~ ‒ 0.01 Z-score / mg/dl-glucose. Consequently, to have the Z-Score change by 0.5 would require a glucose variation of 50 mg/dl. The most sensitive region to glucose was the postcentral gyrus at ‒ 0.016. Even the parietal lobe at 20.5% of the brain volume was relatively insensitive at ‒ 0.007 Z-score / mg/dl-glucose. Additionally, these regions are not significant when normalized by the cerebellum or pons.

From Table 3, a similar observation with age is seen. Although more regions are effected by age then glucose, the results are only present with the whole brain normalizations and the various region affected individual constitute a small volume of cortical tissue. Similarly, the effect that is seen, also appears minimal with the most significant being 0.055 Z-score / yr in the postcentral gyrus, therefore a decade would cause a change in Z-score of ~0.5.

4. Discussion

The use of brain FDG PET/CT for diagnosis of dementia, has been augmented by quantitative assessment of images as an adjunct to clinical diagnosis using parametric voxel-based techniques [1,14,15]. We have previously reported that cerebral cortical FDG uptake has a negative inverse relationship to blood glucose levels, with decreasing brain SUV as blood glucose levels increase [7], confirming similar observations by other authors [5,6]. Rather than using normal subjects our study is purposely limited to a cohort of oncology patients free of neurological disease, prior chemotherapy or radiations therapy, CVA or clinical concern for dementia, thus providing a greater number of subjects allowing us to analyze the effect of plasma glucose upon FDG uptake in different brain regions, treating plasma glucose as a continual variable rather than a binary categorical comparison as was previously done in smaller sized studies [8,16]. In our prior published work and the data in this specific cohort, we found that both absolute and normalized brain FDG uptake declined by almost 50% at blood glucose levels exceeding 150mg/dL with an inflection around 125 mg/dl [7].

More recent studies have raised the possibility that mild elevation in glucose may not only reduce image quality of brain FDG PET/CT by reducing SUV measurements, but more importantly mimic disease states due to preferential regional effects upon FDG uptake [8,17] In a small study of 19 healthy subjects, Kawasaki et al. 17] used SPM, a quantitative voxel-based technique to demonstrate a 42.7% decrease in global brain FDG uptake in mild hyperglycemia (glucose 136.1 ± 10.5mg/dL) compared to subjects with normoglycemia (glucose 91.7 ± 4.6mg/dL). The cortical regions involved were frontal, temporal and parietal association cortices, posterior cingulate and precuneus gyri, sites well-known to be affected by Alzheimer disease. More recently Ishibashi et al. [8] confirmed these findings in 51 normal subjects using voxel-based quantitative methods with FDG PET co-registered and warped to MRI, demonstrating that elevated blood glucose levels could alter the cerebral pattern of FDG distribution by reducing brain FDG uptake, preferentially in the precuneus, mimicking Alzheimer disease. FDG uptake in the precuneus was significantly lower in the mildly hyperglycemic group (fasting glucose 100–<110 mg/dL) compared with the normoglycemic group (fasting glucose 80– < 100mg/dL) (P = 0.002). The authors postulated that the normal control database requires a threshold of 100mg/dL for fasting glucose in order to maintain a predictive value for true cognitive decline, distinct from a mild hyperglycemia “effect”. Our results suggest that brain PET/CT imaging should ideally be performed when the plasma blood glucose is < 125mg/mL, to avoid global hyperglycemia leading to decreased cortical brain FDG uptake as suggested in a prior work. Although, our analysis was able to confirm a regional variation effect of elevated plasma glucose, the affect was minimal and only seen when normalization of the uptake occurred with the whole brain. Additionally, there was no discernable pattern of variation corresponding to those seen in different dementias [1].

The lack of clinically significant regional variation is supported with work dating as far back as the 1960’s. It was initially believed that in the absence of specific mental disorders or neurologically active medications, that the rate of glucose metabolism in the brain was fixed and unaffected by factors such as mental activity, dietary intake, fasting state and other such parameters [18]. The labelling of FDG, an analog of glucose and the main energy substrate of the brain, afforded direct measurement of the cerebral metabolic rate for glucose and demonstration that regional brain metabolism relates closely to neuronal and synaptic function in numerous human resting and functional activation imaging studies. Subsequent work on glucose uptake in the brain demonstrated that it was a function of the Glut-1 and 3 transporters, but was also dependent on hexokinase enzyme activity. This was explored extensively with comparative studies of kinetics of C-11/C-14-labelled glucose and FDG in the brain that were summarized in an excellent review by Louis Sokoloff [19]. Glucose and FDG have different rates constants for Glut-1 and hexokinase in brain and other tissues. The correction factor of rate constants for FDG as compared to glucose was termed the “isotope effect” by Sokoloff [19] and is now referred to as the “lumped constant”. The lumped constant was assumed to be independent of blood glucose levels (in the range where most clinical imaging is done) and therefore suggests a linear inverse relationship between FDG uptake and plasma glucose, due to competition of FDG and glucose for available Glut-1 and 3 transporters at the blood-brain barrier.

However, we and others have found that relative availability of FDG and glucose does indeed affect the FDG uptake in the brain, but in a non-linear manner [5–7]. This suggests that the lumped constant is not uniform over the physiological range under which imaging generally occurs given the non-linear (and/or dual linear) relationship of plasma glucose to global brain SUV measurements. Recent animal studies support this observation demonstrating that in rats plasma blood glucose levels affect the calculated lumped constant [20–23] such that brain SUV represents at first in the hypoglycemic-to-euglycemia range, FDG uptake in the brain is related to saturable Glut transporter function, then at higher levels of hyperglycemia switches to an intracellular hexokinase phosphorylation-limited process [20]. Given the insulin independence of Glut 1 and 3 transporters, a patients insulin sensitively is presumably has no effect on FDG uptake in the brain.

The prior work by Ishibashi et al. suggests that in normal subjects, FDG uptake in the brain is different based on categorical comparison of plasma glucose levels above and below 125 mg/dL [8]. This threshold is in the region of the inflection seen between the initial linear response of brain mean SUV uptake versus plasma glucose curve that could potentially be explained by a switch from Glut transporter limited uptake to hexokinase phosphorylation limitation [7]. Overall, although our results confirm that changes in plasma glucose affect FDG uptake in different brain regions depending on the analysis method, in clinical practice this difference will likely not result in different interoperation and believe our study contradicts prior reports. Consequently, for regional differences in the glucose effect on FDG uptake in the brain to occur biologically, it would either have to be related to glucose dependent changes to perfusion in the different regions of the brain, or variation in the lumped constant in different brain regions. It is difficult to posit the mechanisms of a glucose effect upon brain perfusion, offered by Ishibashi et al. [8,16]. There may however, be small variation in the lumped constants in different cortical regions of the brain that our results suggest, but if present these variations are not large and not likely clinical influential. The fact variation in the whole brain analysis was not seen in the Pons or Cerebellum analysis further supports a small effect. These regions constitute only 0.5% and 7% of the whole brain volume respectively, and subsequent normalization with them likely results in higher variability in Z-score estimates and consequently their results lacks the statistical significance with glucose.

We acknowledge several weaknesses in our study design. Firstly, it is a retrospective analysis of a male cohort in whom imaging was done for initial cancer staging. However, use of oncologic patients instead of normal volunteer subjects allowed our analysis to treat plasma glucose as a continuous variable, for multiple regression analysis. Secondly we did not adjust findings for patient age. Thirdly, the parametric analysis of brain SUV mean was based on vendor-specific control databases, rather than those generated on our local population which has been shown to have a significant effect depending on what population is being looked at [24]. Fourthly, we used a regional instead of voxel-wise analysis, Ishibashi et al used the later. Whilst this reduces the contribution of noise of the data, it also created dependence on which regions were selected/defined by the software reformatting and mapping process along with the characteristics of the database used. We plan to evaluate this by repeating the analysis using a second vendor’s software on the same dataset. Although a weakness, we were attempting to emulate how this imaging test is employed in the wider community clinical practice to give a “real world usage” evaluation and impact these variations may have on clinical interpretation.

5. Conclusion

Although plasma glucose does affect FDG uptake in the regional brain, the effect is small and is of greater concern on a global effect rather than a regional effect. We were unable to find a situation where FDG uptake could be altered on a regional basis by mild hyperglycemia in a clinically meaningful way that could lead to misdiagnosis of AD.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- [1].Brown RK, Bohnen NI, Wong KK, Minoshima S, Frey KA, Brain PET in suspected dementia: patterns of altered FDG metabolism, Radiographies 34 (3) (2014) 684–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shivamurthy VK, Tahari AK, Marcus C, Subramaniam RM, Brain FDG PET and the diagnosis of dementia, AJR Am. J. Roentgenol 204 (1) (2015) W76–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Barron CC, Bilan PJ, Tsakiridis T, Tsiani E, Facilitative glucose transporters: implications for cancer detection, prognosis and treatment, Metabolism 65 (2) (2016) 124–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Thorens B, Mueckler M, Glucose transporters in the 21st Century, Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab 298 (2) (2010) El41–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Claeys J, Mertens K, D’Asseler Y, Goethals I, Normoglycemic plasma glucose levels affect F-18 FDG uptake in the brain, Ann. Nucl. Med 24 (6) (2010) 501–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Keramida G, Dizdarevic S, Bush J, Peters AM, Quantification of tumour (18) F-FDG uptake: normalise to blood glucose or scale to liver uptake? Eur. Radiol 25 (9) (2015) 2701–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Viglianti BL, Wong KK, Wimer SM, et al. , Effect of hyperglycemia on brain and liver 18F-FDG standardized uptake value (FDG SUV) measured by quantitative positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, Biomed. Pharmacother 88 (2017) 1038–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ishibashi K, Onishi A, Fujiwara Y, Ishiwata K, Ishii K, Relationship between Alzheimer disease-like pattern of 18F-FDG and fasting plasma glucose levels in cognitively normal volunteers, J. Nucl. Med 56 (2) (2015) 229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Varrone A, Asenbaum S, Vander Borghi T, et al. , EANM procedure guidelines for PET brain imaging using [18F]FDG, version 2, Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 36 (12) (2009) 2103–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Viglianti BL, Wale DJ, Wong KK, et al. , Effects of tumor burden on reference tissue standardized uptake for PET imaging: modification of PERCIST criteria, Radiology 287 (3) (2018) 993–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Searle SR, Casella G, McCulloch CE, Variance Components, Wiley, New York, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y, Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing, J. R. Stat. Soc. B Methodol 57 (1) (1995) 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yekutieli D, Benjamini Y, Resampling-based false discovery rate controlling multiple test procedures for correlated test statistics, J. Stat. Plan. Inference 82 (1–2) (1999) 171–196. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Coleman RE, Positron emission tomography diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease, Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am 15 (4) (2005) 837–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Van Heertum RL, Tikofsky RS, Positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography brain imaging in the evaluation of dementia, Semin. Nucl. Med 33 (1) (2003) 77–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Ishibashi K, Kawasaki K, Ishiwata K, Ishii K, Reduced uptake of 18F-FDG and 150-H20 in Alzheimer’s disease-related regions after glucose loading, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 35 (8) (2015) 1380–1385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Kawasaki K, Ishii K, Saito Y, Oda K, Kimura Y, Ishiwata K, Influence of mild hyperglycemia on cerebral FDG distribution patterns calculated by statistical parametric mapping, Ann. Nucl. Med 22 (3) (2008) 191–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Socoloff L, The Metabolism of the Central Nervous System in Vivo, American Physiological Society, Washington, DC, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Sokoloff L, Localization of functional activity in the central nervous system by measurement of glucose utilization with radioactive deoxyglucose, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1 (1) (1981) 7–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Crane PD, Pardridge WM, Braun LD, Oldendorf WH, Kinetics of transport and phosphorylation of 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose in rat brain, J. Neurochem 40 (1) (1983) 160–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mori K, Cruz N, Dienei G, Nelson T, Sokoloff L, Direct chemical measurement of the lambda of the lumped constant of the [14C] deoxyglucose method in rat brain: effects of arterial plasma glucose level on the distribution spaces of [14C] deoxyglucose and glucose and on lambda, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 9 (3) (1989) 304–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schuier F, Orzi F, Suda S, Lucignani G, Kennedy C, Sokoloff L, Influence of plasma glucose concentration on lumped constant of the deoxyglucose method: effects of hyperglycemia in the rat, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10 (6) (1990) 765–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Suda S, Shinohara M, Miyaoka M, Lucignani G, Kennedy C, Sokoloff L, The lumped constant of the deoxyglucose method in hypoglycemia: effects of moderate hypoglycemia on local cerebral glucose utilization in the rat, J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 10 (4) (1990) 499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Mosconi L, Tsui WH, Pupi A, et al. , (18)F-FDG PET database of longitudinally confirmed healthy elderly individuals improves detection of mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease, J. Nucl. Med 48 (7) (2007) 1129–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]