Shewanella species have long been described as interesting microorganisms in regard to their ability to reduce many organic and inorganic compounds, including metals. However, members of the Shewanella genus are often depicted as cold-water microorganisms, although their optimal growth temperature usually ranges from 25 to 28°C under laboratory growth conditions. Shewanella decolorationis LDS1 is highly attractive, since its metabolism allows it to develop efficiently at temperatures from 24 to 40°C, conserving its ability to respire alternative substrates and to reduce toxic compounds such as chromate or toxic dyes. Our results clearly indicate that this novel strain has the potential to be a powerful tool for bioremediation and unveil one of the mechanisms involved in its chromate resistance.

KEYWORDS: Shewanella, bioremediation, chromium, decolorization, dndBCDE, dyes, temperature

ABSTRACT

The genus Shewanella is well known for its genetic diversity, its outstanding respiratory capacity, and its high potential for bioremediation. Here, a novel strain isolated from sediments of the Indian Ocean was characterized. A 16S rRNA analysis indicated that it belongs to the species Shewanella decolorationis. It was named Shewanella decolorationis LDS1. This strain presented an unusual ability to grow efficiently at temperatures from 24°C to 40°C without apparent modifications of its metabolism, as shown by testing respiratory activities or carbon assimilation, and in a wide range of salt concentrations. Moreover, S. decolorationis LDS1 tolerates high chromate concentrations. Indeed, it was able to grow in the presence of 4 mM chromate at 28°C and 3 mM chromate at 40°C. Interestingly, whatever the temperature, when the culture reached the stationary phase, the strain reduced the chromate present in the growth medium. In addition, S. decolorationis LDS1 degrades different toxic dyes, including anthraquinone, triarylmethane, and azo dyes. Thus, compared to Shewanella oneidensis, this strain presented better capacity to cope with various abiotic stresses, particularly at high temperatures. The analysis of genome sequence preliminary data indicated that, in contrast to S. oneidensis and S. decolorationis S12, S. decolorationis LDS1 possesses the phosphorothioate modification machinery that has been described as participating in survival against various abiotic stresses by protecting DNA. We demonstrate that its heterologous production in S. oneidensis allows it to resist higher concentrations of chromate.

IMPORTANCE Shewanella species have long been described as interesting microorganisms in regard to their ability to reduce many organic and inorganic compounds, including metals. However, members of the Shewanella genus are often depicted as cold-water microorganisms, although their optimal growth temperature usually ranges from 25 to 28°C under laboratory growth conditions. Shewanella decolorationis LDS1 is highly attractive, since its metabolism allows it to develop efficiently at temperatures from 24 to 40°C, conserving its ability to respire alternative substrates and to reduce toxic compounds such as chromate or toxic dyes. Our results clearly indicate that this novel strain has the potential to be a powerful tool for bioremediation and unveil one of the mechanisms involved in its chromate resistance.

INTRODUCTION

Shewanella species are part of the Gammaproteobacteria class of the Proteobacteria phylum. They have been found all around the world in briny or fresh water and in sediments from polar circles to equatorial biotopes (1, 2). Their trademark is their tremendous variety of respiratory capacities, which allows their growth with a large panel of exogenous electron acceptors, including solid and soluble metals, explaining why they belong to the restricted family of dissimilatory metal-reducing bacteria (3). Partly due to their reducing abilities, Shewanella species have the capacity to cope with elevated concentrations of toxic products such as hydrocarbons, arsenate, and hexahydro-1,3,5-trinitro-1,3,5-triazine (4–9). This ability has made them a useful tool for bioremediation and cleanup (1–3, 10, 11). Moreover, it appears that the members of this genus adapt easily to various life conditions. Although they are usually found in aquatic habitats, some can develop in other biotopes, like butter, crude oil, or even human corpses (1, 2, 12).

Within the genus, Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 has become the strain of reference in many laboratories, and it is clearly the best described. Like most of the other species in the genus, its optimal growth temperature is around 2 to 28°C (13), and it requires the HtpG general chaperone to survive at 35°C (14). It can grow in either brackish or fresh water, and it possesses an efficient chemosensory system that allows it to adapt rapidly under nutrient deprivation or stressful conditions (15–17). It was shown that S. oneidensis MR-1 survives in elevated concentrations of chromate by developing several resistance strategies, such as oxidative stress protection, detoxification, SOS-controlled DNA repair mechanisms, and different pathways for Cr(VI) reduction (18, 19). Indeed, in addition to enzymatic reduction of chromate [hexavalent chromium Cr(VI)] into a less mobile form [Cr(III)] that presents a decreased toxicity (20–23), S. oneidensis, like other members of the genus, possesses a chromate efflux pump able to extrude chromate from the cell, increasing its resistance against the metal (24).

Although S. oneidensis is the model bacterium of the genus, many other species are studied because, beside their common characteristics, they present peculiar aspects that confer useful properties, especially for biotechnology (1–3, 25). Thus, these bacteria often have been isolated from polluted areas, wastewater, or sewage plants. Recently, the genome of Shewanella algidipiscicola H1, isolated from the sediment of the industrial Algerian Skikda harbor, was sequenced (26). This strain is proposed to be the most resistant Shewanella in chromium-containing medium. A second strain highly resistant to toxic metals, Shewanella sp. strain ANA-3, comes from water contaminated with arsenate that the bacterium uses as a respiratory substrate (5). Shewanella halifaxensis, isolated from an immersed munition-dumping zone, can degrade explosive compounds to generate respiratory substrates (9). As a last example, Shewanella decolorationis S12, capable of efficient dye-decolorization activity, was isolated from sludges of a textile-printing wastewater treatment plant in China (27). Thus, in the genus Shewanella, the various species present distinctive properties that make them genuine tools to cope with a large range of human environmental misconducts.

This large panel of enzymatic activities is correlated with the genetic variability found in the genus Shewanella. This genus was difficult to define correctly because of the diversity of the species it contains (1–3, 25). This point is illustrated by the increasing number of Shewanella species found in databases, corresponding to almost 70 species and 30 sequenced genomes. The high diversity of Shewanella genomes is really astonishing. Recently, pangenome analyses of 24 Shewanella strains established that the core genome corresponds to only 12% of the total genes (25). This small number of shared genes is consistent with a genus that is genetically versatile and has had frequent lateral gene transfer events.

The purpose of the current study is to characterize a novel strain, S. decolorationis LDS1, to gain greater insight into Shewanella behaviors in bioremediation and depollution. Since S. decolorationis LDS1 reduces chromate into a less soluble and thus less toxic compound and decolorizes various dyes, both in a large range of temperatures, and possesses a DNA modification system that is suspected to protect bacteria against environmental stresses, this novel strain presents interesting biotechnological potential.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Strain isolation and characterization.

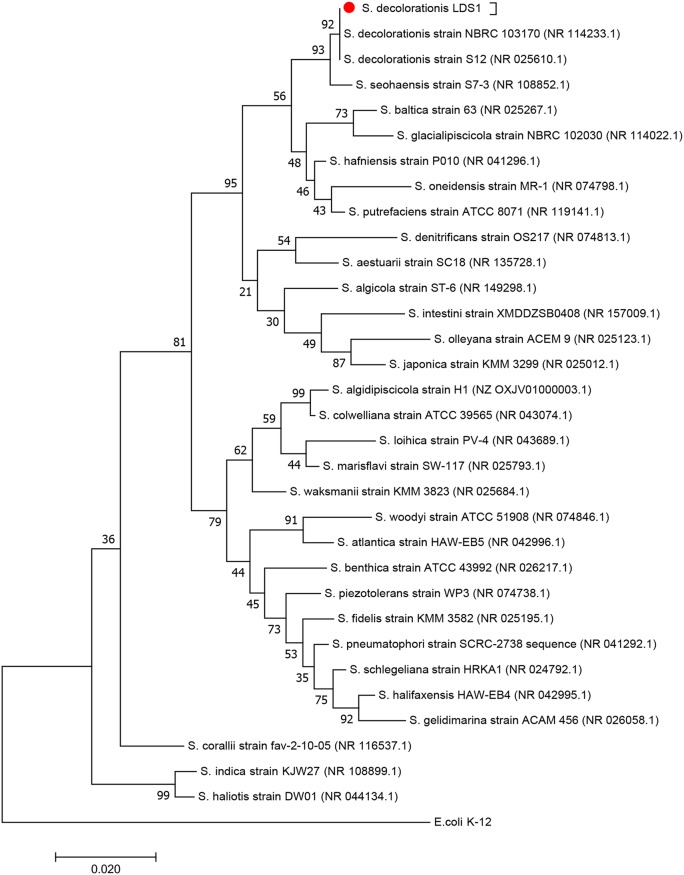

S. decolorationis strain LDS1 (for La Digue Seychelle; also named S. decolorationis subsp. sesselensis [CP037898]) was isolated from a sample of sediments collected in a pond at the Anse Coco beach (La Digue Island, Republic of Seychelles, Indian Ocean) on the basis of its capability to grow on rich medium containing trimethylamine oxide (TMAO). Indeed, the latter is a compound widespread in marine environments, and, with a few exceptions, it is used as a major respiratory substrate by Shewanella species (28–31). Based on a comparison of the conserved 16S rRNA genes of over thirty Shewanella species, a phylogenetic tree was constructed (Fig. 1). Members of the genus Shewanella can be divided into two types, mesophilic and piezotolerant species (32, 33). S. decolorationis LDS1 was among the mesophilic subgroup in the clade containing the two other defined strains of S. decolorationis species, with which it shared 100% 16S rRNA gene identity (27, 34). These species, known for their decolorization activities, are described as growing at higher temperatures than do S. oneidensis and most other species, since they survive at 40°C, although they present optimal growth from 20 to 30°C.

FIG 1.

Evolutionary relationships of taxa. Phylogenetic tree reconstructed by the maximum composite likelihood method (50) based on the nucleotide sequence of 16S rRNA of 33 species of Shewanella. The tree with the highest log likelihood (−4,930.1497) is shown. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. The initial tree(s) for the heuristic search was obtained automatically by applying neighbor joining and BioNJ algorithms to a matrix of pairwise distances estimated using the maximum composite likelihood (MCL) approach and then selecting the topology with the superior log likelihood value. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 33 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There was a total of 1,128 positions in the final data set.

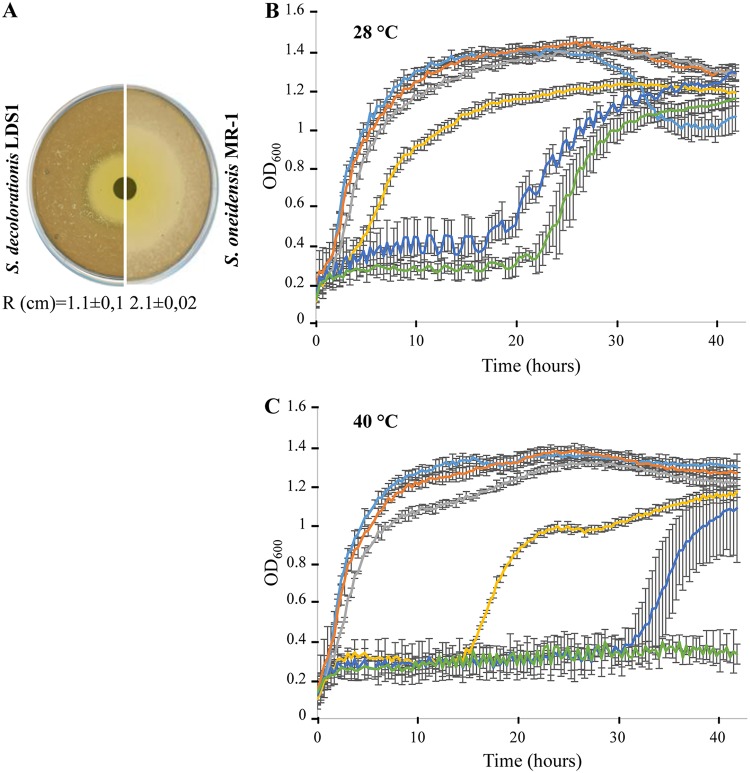

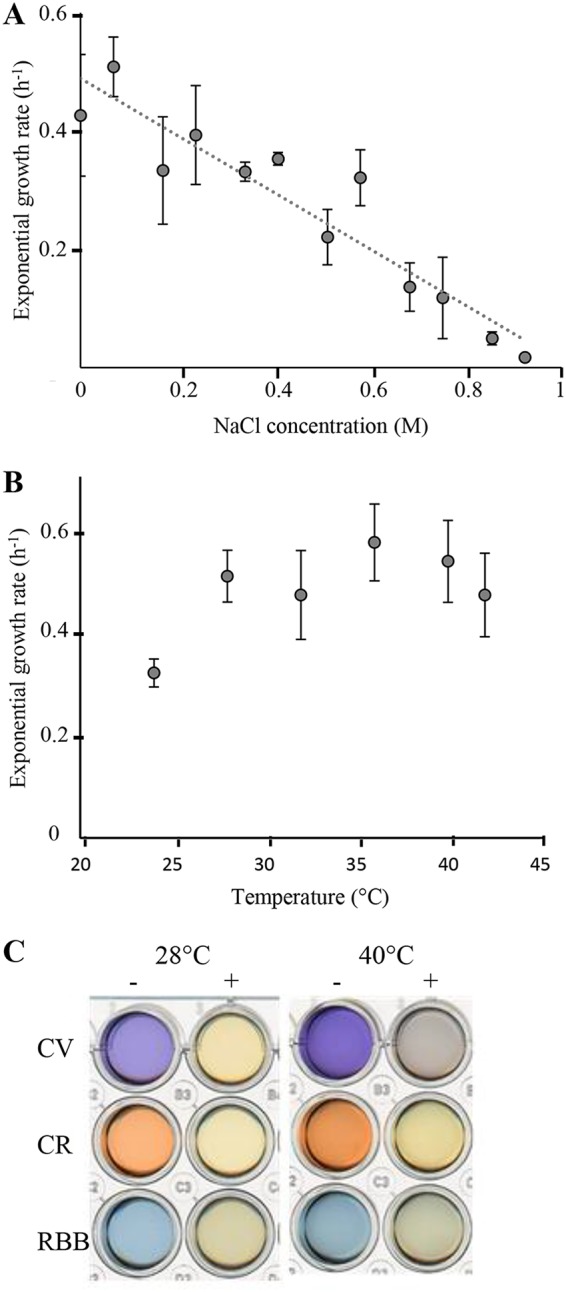

Since Shewanella species are originally marine bacteria (2), S. decolorationis LDS1 was cultivated at various salt concentrations. It was able to grow from very low to high concentrations of salt, even higher than that of the ocean (about 0.5 M) (Fig. 2A) (17). S. decolorationis LDS1 was then phenotypically characterized in order to test its abilities to grow at high temperatures and to decolorize dyes and thus to explore if it exhibits different features compared to the already known strains of the clade. The strain was cultivated at various temperatures from 24 to 42°C, and the exponential growth rates are presented in Fig. 2B. Like the other S. decolorationis strains (27), S. decolorationis LDS1 could grow at more elevated temperatures than most of other Shewanella species and, although less efficiently, growth still occurred at 42°C. Interestingly, in contrast to the other Shewanella species described, S. decolorationis LDS1 showed a uniquely wide optimal growth temperature, since it presented a plateau ranging from 24 to 40°C. S. decolorationis LDS1 was then challenged for its ability to decolorize Remazol brilliant blue (RBB), crystal violet (CV), and Congo red (CR), which are members of the anthraquinone, triarylmethane, and azo dye families, respectively. As expected for the strains of this species, the dyes were at least partially converted by S. decolorationis LDS1 at 28°C (Fig. 2C). We used this property to check the efficiency of the strain at 40°C, and, as shown in Fig. 2C, S. decolorationis LDS1 was still able to decolorize the three families of dyes. At both temperatures, the color of the medium without bacteria remained identical for more than ten days (Fig. 2C). This strain seems to be able to decolorize dyes, including anthraquinone, triarylmethane, and azo dyes, from 28 to 40°C. This characterization suggests that S. decolorationis LDS1 presents an adapted metabolism that allows it to cope efficiently from medium to elevated temperatures.

FIG 2.

S. decolorationis LDS1 behaviors. (A) Exponential growth rate of S. decolorationis LDS1 as a function of NaCl concentration in the medium. The strain was grown aerobically in LB medium. Each point corresponds to the average of at least three independent replicates. (B) Exponential growth rate of S. decolorationis LDS1 as a function of incubation temperature. The strain was grown aerobically in LB medium. Each point corresponds to the average of at least three independent replicates. (C) Dye decolorization by S. decolorationis LDS1 at 28 and 40°C. Cellfree supernatant of a 10-day culture of S. decolorationis LDS1 in LB medium in the presence of crystal violet (CV), Congo red (CR), or Remazol brilliant blue (RBB) from the triarylmethane, azo, and anthraquinone dye families, respectively. +, bacteria were added prior to incubation; −, bacteria were not added prior to incubation.

To better determine the physiological capacities of the strain at high temperature, we decided to compare its TMAO reductase activity at 28 and 40°C. The TMAO reductase activity was first followed through the alkalization of the growth medium, indicating that the increase of the temperature has no effect since the alkalization of the medium was similar (Table 1). For a more accurate activity, we measured the TMAO reductase activity of crude extracts of cells grown at 28 or 40°C. The TMAO reductase specific activity of this strain at 40°C was half that at 28°C (2.8 ± 0.17 μmol/min/mg versus 5.95 ± 0.40 μmol/min/mg, respectively). Measures of nitrate reduction and other phenotypic characteristics obtained with API 20NE plates (bioMérieux, France) are recorded in Table 1 and showed no significant difference at 28 and 40°C, except for the hydrolysis of capric acid, which could be due to the instability of the product rather than to the activity of the enzyme. Together, these results suggest that the strain has fully adapted from medium to elevated temperatures by increasing the range of its optimal growth temperature. The tested respiratory activities (oxygen, TMAO, and nitrate) confirmed that they were efficient from 28 to 40°C. In contrast to S. decolorationis S12 and the other strains presented in Table 2, S. decolorationis LDS1 could not grow at very low temperatures. The fact that this strain seemed to have lost this ability was not surprising, considering that the biotope from which it was isolated probably does not encounter temperatures below 25°C.

TABLE 1.

Enzymatic activities and carbon source assimilation of S. decolorationis LDS1 at 28 and 40°C

| Enzyme activity or carbon source assimilation | Temperature (°C) |

|

|---|---|---|

| 28 | 40 | |

| Enzyme activity | ||

| Nitrate reductase | + | + |

| TMAO reductasea | + | + |

| Gelatinase | + | + |

| Iron reduction | + | + |

| Assimilation | ||

| d-Glucose | + | + |

| N-Acetylglucosamine | + | + |

| d-Maltose | + | + |

| Caprate | + | − |

| Malate | + | + |

Activity estimated by the alkalization of the growth medium (29).

TABLE 2.

Phenotypic characteristics of various Shewanella species

| Phenotypic characteristic | Present in Shewanella speciesa: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Growth (4°C) | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Growth (40°C) | + | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Enzyme activity (28°C) | |||||||

| Nitrate reductase | + | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND |

| Tryptophanase | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

| Arginine dehydrolase | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

| Urease | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

| Esculinase | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

| Gelatinase | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| β-Galactosidase | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

| Fermentation of glucose | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| Assimilation (28°C) | |||||||

| d-Glucose | + | + | + | − | + | − | − |

| l-Arabinose | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| d-Mannose | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

| d-Mannitol | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| N-Acetylglucosamine | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| d-Maltose | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Gluconate | − | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| Caprate | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Adipate | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

| Malate | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Citrate | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| Phenylacetate | − | ND | ND | ND | ND | − | ND |

Other differences could be pointed out. Indeed, unlike S. decolorationis S12, S. decolorationis LDS1, like many other Shewanella species, did not use glucose for fermentation, although it performed its assimilation (Table 2). Moreover, the range of optimal pH for growth ranged from 6.0 to 11.0, which was slightly wider than that of other Shewanella strains (27). This probably results from the sampling of S. decolorationis LDS1 from brackish water, which can be more acidic than seawater. Together, these results indicate that the S. decolorationis LDS1 shares with other S. decolorationis strains the ability to grow at higher temperatures than most of the other Shewanella species. However, only S. decolorationis LDS1 presents the same growth rate from 24 to 40°C. Moreover, it appears that its metabolism is not drastically affected by high temperature, since most of the tested activities were similar or still measurable regardless of the growth temperature.

Chromate resistance and reduction.

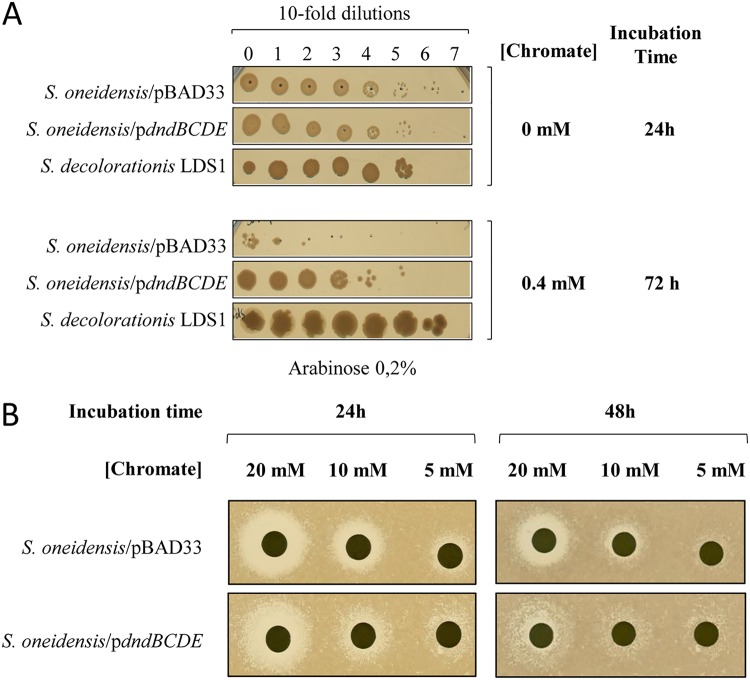

Recent studies have focused on the ability of Shewanella species to reduce chromate (19, 21–24). For instance, S. oneidensis MR-1 can resist 1 mM chromate, whereas, Shewanella algidipiscicola H1 grows in 3 mM chromate (18, 26). In order to compare the resistance against chromate of S. decolorationis LDS1 with that of the model bacterium S. oneidensis, a preliminary test was done on solid medium containing a filter soaked with a 1 M chromate solution, leading to the formation of a gradient of chromate by diffusion in the solid medium. As shown in Fig. 3A, S. decolorationis LDS1 was more resistant than S. oneidensis at 28°C, since it was able to grow closer to the filter. Moreover, in liquid medium, S. oneidensis barely resisted 1 mM chromate (18), while this concentration did not affect S. decolorationis LDS1 (Fig. 3B). This indicates that S. decolorationis LDS1 can resist higher chromate concentrations. To confirm this point, its growth was followed under aerated conditions at 28°C in the presence of increasing concentrations of chromate. As shown in Fig. 3B, no drastic growth difference was noticeable in the range of chromium concentration from 0 to 2 mM, although a short lag phase was observed at 2 mM. In the presence of 3 and 4 mM chromate, the cell growth presented a pronounced lag phase of about 20 h, but the curves finally reached the same plateau value in comparison to that of the cultures grown at lower concentrations or without the addition of chromate. This long lag phase could be necessary for the bacteria to adapt to the high chromate concentrations by producing either Cr(VI)-reducing systems or Cr efflux pumps. In addition, chromate resistance was followed at 40°C (Fig. 3C). The results indicate that growth is not modified until 1 mM chromate in the medium. At higher concentrations, the lag phases were increased (15 and 30 h for 2 and 3 mM, respectively), while at 4 mM no growth was observed after 40 h. Together, these data establish that S. decolorationis LDS1 resists chromate, even at elevated temperatures.

FIG 3.

Chromate resistance of S. decolorationis LDS1 and S. oneidensis MR-1. (A) Chromate resistance was tested on solid LB medium. Cells (150 μl; OD = 0.001) were spread on the plate, and 50 μl of chromate (1 M) was loaded on the filter. Plates were incubated for 12 h at 28°C. The radius (R) of each halo is indicated in centimeters. (B and C) Chromate resistance of S. decolorationis LDS1 was tested on liquid LB medium at 28°C (B) and 40°C (C) with increasing concentration of chromate, as follows: 0 mM (light blue), 0.5 mM (orange), 1 mM (gray), 2 mM (yellow), 3 mM (dark blue), and 4 mM (green). Each point corresponds to the average of at least three independent replicates. Averages and standard deviations from at least three independent experiments are shown.

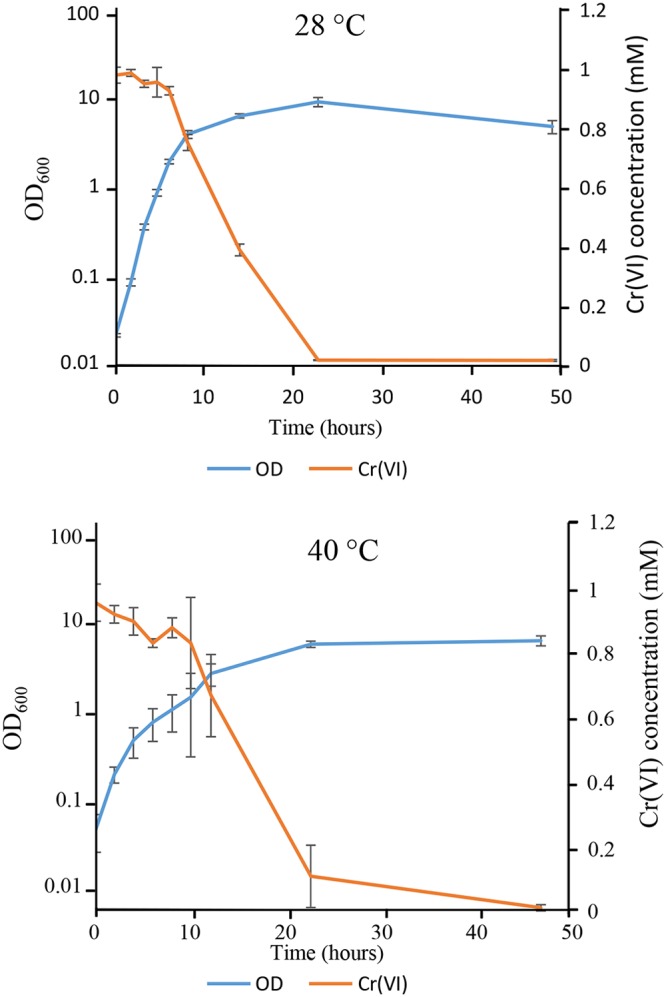

Finally, we wondered whether S. decolorationis LDS1 was able to reduce chromate during its growth. This is of great interest, since chromate reduction leads to a less soluble and less toxic form for the environment (20, 23). Thus, S. decolorationis LDS1 was grown at 28°C in the presence of 1 mM chromate to guarantee robust growth, and reduction of Cr(VI) to Cr(III) in the growth medium was followed. Strikingly, when the medium was inoculated with cells of S. decolorationis LDS1, Cr reduction appeared when the culture entered into the stationary phase (Fig. 4). From that time, reduction of chromate was almost complete within 15 h. A similar experiment was performed at 40°C. As for the lower temperature, the reduction of chromate started when the cells reached the stationary phase (Fig. 4). From these results, it is clear that S. decolorationis LDS1 can reduce chromate at high temperature with the same efficiency as that at 28°C. The mechanism involved is clearly acting from the beginning of the stationary phase, as suggested by the trigger of the reduction when the bacteria reach it, as already described under anaerobic growth of S. oneidensis MR-1 (23).

FIG 4.

Chromate reduction by S. decolorationis LDS1 at 28 and 40°C. Cells were grown in LB medium containing 1 mM chromate. The growth was followed spectrophotometrically (OD = 600 nm), and Cr(VI) reduction was measured by the DPC method. Averages and standard deviations from at least three independent experiments are shown.

Data from genome sequence.

Since S. decolorationis LDS1 was able to cope better with various stresses than does S. oneidensis and has a better heat resistance than S. decolorationis S12, we wondered whether this strain has specific machineries leading to an increase of its resistance to environmental cues. Indeed, Shewanella species are described as presenting a high level of genetic variability that confers to each of them peculiar properties (3, 25). The genome of S. decolorationis LDS1 was sequenced at the Molecular Research LP (MR DNA) Laboratory (USA). A preliminary analysis indicated that the draft genome sequence contained 4,223 potential protein-coding genes. A genome comparison was undertaken between the two sequenced S. decolorationis strains (S12 and LDS1) and S. oneidensis MR-1 (Table 3). Among genes shared by the two other species, more than 40 code for c-type cytochromes, which are a trademark of bacteria of the Shewanella genus. However, the results indicated that 12% of the S. decolorationis LDS1 genome was not shared by the two other strains.

TABLE 3.

Genome overview of S. decolorationis LDS1, S. decolorationis S12, and S. oneidensis MR-1

| Genome descriptor | S. decolorationis LDS1 | S. decolorationis S12 | S. oneidensis MR-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| GC content (%) | 47.12 | 47.09 | 45.96 |

| Size (bp) | 4,719,362 | 4,851,566 | 4,969,811 |

| No. of DNA scaffolds | 16 | 77 | 0 |

| Total no. of genes | 4,430 | 4,451 | 5,031 |

| No. of coding sequences | 4,223 | 4,309 | 4,444 |

| No. of common genes | 3,535 | 3,535 | 3,535 |

| No. of strain-specific genes | 259 | 345 | 375 |

Among the 259 potential genes present only in the S. decolorationis LDS1 genome, 153 have been annotated, but 99 of them have an unknown function (Table 4). Several of the other 54 genes drew our attention (Table 4). For instance, we noticed two operons that could play a central role in the adaptation of the strain to environmental stresses. First, the dndBCDE operon encodes the phosphorothioate (PT) modification machinery that replaces a nonbridging oxygen by a sulfur in the DNA sugar phosphate backbone (35–37) (Table 4). The sequences recognized by the modification machinery are not fully established, and studies have shown that only 12% of the potential sites recognized by the PT system are effectively modified and that from one cell to another, the modifications are not conserved (38, 39). Moreover, it seems that when the potential target site is present in the binding motif of an important regulatory protein, no modification occurs. This was demonstrated for TorR and RpoE binding sites (38). In Shewanella species, the Tor system, which is regulated by TorR, is a major respiratory system (40), and RpoE controls the expression of stress response genes (41). Generally, the modification machinery includes an additional protein, DndA, a cysteine desulfurase (42). The dndA gene is absent in S. decolorationis LDS1 and, as described in the literature, it is probably replaced in the machinery by IscS (SDECO_v1_40139) (39). A bioinformatics analysis using the DndC sequence as a probe indicated that only three unrelated species of Shewanella, Shewanella baltica, Shewanella pealeana ATCC 700345, and Shewanella violacea DSS12, possess this machinery, with 92.8%, 67.8%, and 66.5% identity, respectively. This indicates that S. decolorationis LDS1 has probably acquired the genes of the Dnd machinery from another bacterial genus.

TABLE 4.

Proteins specifically found in S. decolorationis LDS1 by genome sequencing and annotation

| Locus | Predicted functiona |

|---|---|

| SDECO_v1_10304 | Transcriptional regulator |

| SDECO_v1_10308 | IclR family transcriptional regulator |

| SDECO_v1_10310 | Transposase |

| SDECO_v1_10317 | Phage tail tape measure protein |

| SDECO_v1_10321 | DUF1983 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_10405 | DUF262 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_11406 | Arc family DNA-binding protein |

| SDECO_v1_10464 | DUF4868 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_10506 | DUF5071 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_10701 | DUF4265 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_10782 | Restriction endonuclease |

| SDECO_v1_10884 | DUF3916 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_11229 | SMP-30/gluconolactonase/LRE family protein |

| SDECO_v1_11230 | Glycosyltransferase family 2 |

| SDECO_v1_11231 | Acylneuraminate cytidylyltransferase family protein |

| SDECO_v1_11234 | DUF115 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_11235 | Polysaccharide biosynthesis protein |

| SDECO_v1_11238 | DUF115 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_11243 | DUF1972 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_11404 | Transcriptional regulator |

| SDECO_v1_11405 | DNA-binding protein |

| SDECO_v1_11468 | DGQHR domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20119 | DUF3578 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20120 | DUF2357 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20196 | DUF4065 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20376 | DUF4297 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20377 | NYN domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20445 | Helicase |

| SDECO_v1_20479 | Esterase |

| SDECO_v1_20492 | DUF4263 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20493 | DUF4062 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_20559 | Zinc chelation protein SecC |

| SDECO_v1_20672 | Polysaccharide lyase |

| SDECO_v1_30058 | Serine protease |

| SDECO_v1_30517 | Type I-F CRISPR-associated endoribonuclease Cas6/Csy4 |

| SDECO_v1_30520 | CRISPR-associated endonuclease Cas3 |

| SDECO_v1_30521 | Type I-F CRISPR-associated endonuclease Cas1 |

| SDECO_v1_30534 | DNA sulfur modification protein DndB |

| SDECO_v1_30535 | DNA phosphorothioation system sulfurtransferase DndC |

| SDECO_v1_30536 | DNA sulfur modification protein DndD |

| SDECO_v1_30537 | DNA sulfur modification protein DndE |

| SDECO_v1_30540 | DNA phosphorothioation-dependent restriction protein DptH |

| SDECO_v1_30541 | DNA phosphorothioation-dependent restriction protein DptG |

| SDECO_v1_30542 | DNA phosphorothioation-dependent restriction protein DptF |

| SDECO_v1_40174 | DUF4062 domain-containing protein |

| SDECO_v1_40306 | MBL fold hydrolase |

| SDECO_v1_50042 | HNH endonuclease |

| SDECO_v1_50046 | ATP-binding protein |

| SDECO_v1_50214 | Glycosyltransferase |

| SDECO_v1_50216 | Glycosyltransferase |

| SDECO_v1_60106 | ATP-binding protein |

| SDECO_v1_80044 | Host-nuclease inhibitor protein Gam |

| SDECO_v1_80074 | Phage tail tape measure protein |

| SDECO_v1_80075 | Tape measure domain-containing protein |

MBL, metallo-β-lactamase.

pthFGH, the other interesting operon (43), is found in the same locus as the dndBCDE operon. It is related to the dnd gene products, and it encodes DNA restriction enzymes, which together the modification-restriction (M-R) system. In many bacteria producing the Dnd machinery, the restriction system is absent (38). The inability of S. decolorationis LDS1 to grow at low temperatures is noticeable. Indeed, it was established in Escherichia coli B7A and in Salmonella enterica serovar Cerro strain 87 that the restriction system is temperature dependent and is activated at 15°C (44). The temperature dependence of the restriction system in S. decolorationis LDS1 is yet to be determined, as is the role of that restriction system once activated.

Protection by the DndBCDE machinery.

The function of this M-R system is not well understood, and an additional role in the epigenetic control of gene expression is suspected (39). Indeed, the products of the dnd operon were shown to sustain bacterial growth under stresses like H2O2, heat, or salinity by protecting DNA from oxidative damage and restriction enzymes (44). In agreement with experiments done in Escherichia coli and Shewanella piezotolerans, our hypothesis is that the production of DndB through DndE proteins improves the growth of S. decolorationis LDS1 under oxidative conditions. The presence of chromate leads to oxidative damages in bacteria. Thus, to investigate whether the dnd operon plays a role in the robustness of S. decolorationis LDS1 toward chromate, dndBCDE genes carried by the pBAD33 vector (pdndBCDE) were introduced into S. oneidensis MR-1. S. oneidensis MR-1 harboring either pdndBCDE or the pBAD33 vector and S. decolorationis LDS1 were grown aerobically in the presence of arabinose to induce dndBCDE expression from the plasmid, and serial dilutions were spotted on plates containing chromate (0.4 mM) (Fig. 5). The growth of S. oneidensis MR-1 harboring pBAD33 was drastically affected, whereas when carrying pdndBCDE, the strain was able to grow. Growth of S. decolorationis LDS1 was similar in the presence or absence of chromate. This result indicates that the presence and expression of the dndBCDE operon allow S. oneidensis to resist higher chromate concentrations. However, since S. decolorationis LDS1 resists better than the recombinant S. oneidensis MR-1 strain and also resists higher concentrations than this strain does, we suggest that the DndBCDE machinery is only one element of the bacterial equipment allowing the high level of resistance of S. decolorationis LDS1. To ascertain the effect due to the expression of the dndBCDE operon in S. oneidensis MR-1, the reverse experiment was done, and increased chromate concentrations were spotted on a lawn of bacteria. As shown in Fig. 5B, the presence of dndBCDE genes led to a better resistance of the strain after 24 and 48 h of incubation. Moreover, we tested whether the DndBCDE machinery led S. oneidensis MR-1 to develop at temperatures higher than 28°C. At both 38 and 40°C, the growth of S. oneidensis MR-1 was not improved by the presence of DndBCDE, suggesting that this machinery is not sufficient to allow temperature resistance.

FIG 5.

Effect of the presence of dndBCDE genes in S. oneidensis. (A) S. oneidensis harboring either the pBAD33 vector or the pdndBCDE plasmid and S. decolorationis LDS1 cells were grown at 28°C. For the two S. oneidensis recombinant strains, arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol) was added at an OD600 of 0.7 over 2 h. The three strains were diluted to an OD600 of 1. Ten-fold serial dilutions were spotted on LB plates containing arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol) in the absence or presence of chromate (0.4 mM), as indicated. Then, the plates were incubated for 24 or 72 h at 28°C. Plates are representative of at least three experiments. (B) S. oneidensis cells harboring either the pBAD33 vector or the pdndBCDE plasmid were grown at 28°C. After a 2-h arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol) induction, cells were spread on plates, and filters containing the indicated concentration of chromate were dropped on top. Then, the plates were incubated for 24 or 48 h at 28°C. Plates are representative of at least three experiments.

Conclusion.

In conclusion, the novel S. decolorationis LDS1 strain is an intriguing organism, since it is adapted to higher temperatures than most of the other members of this genus. Moreover, it keeps its enzymatic capacity in a large range of elevated temperatures and, under these conditions, its metabolism seems unperturbed. Indeed, its ability to degrade the three families of dyes tested in this study is conserved even at high temperatures. We can hypothesize that S. decolorationis LDS1 probably degrades other pollutants. Its capacity to tolerate high concentrations of chromate in the culture medium indicates that S. decolorationis LDS1 has developed strategies to cope with chromate toxicity. Indeed, from the results obtained here, it appears that during exponential growth, the strain resists the toxic effect of chromate until the stationary phase is reached, which occurs at high cell concentration, when the reduction of chromate occurs. The features of S. decolorationis LDS1—that it grows efficiently from 24 to 40°C and it reduces both toxic dyes and chromate—likely make it an efficient tool for bioremediation of many pollutants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation and genome sequencing.

S. decolorationis LDS1 strain was isolated from a sample of the uppermost 3 cm of muddy sediment of a brackish pond from the Anse Coco Beach in La Digue Island (Seychelles Republic, 4°21′56.309″S, 55°51′4.367″E). The sample was conserved in a sterile plastic tube kept at room temperature during the expedition. The sediments were suspended for 24 h in 15 ml of a 1:4 dilution of LB (1.25 g yeast extract, 1.25 g NaCl, and 2.5 g tryptone per liter [pH 7.2]) in the presence of 40 mM TMAO and 0.5 M NaCl in closed plastic tubes and at room temperature (around 20°C). To avoid alkalinization of the medium due to trimethylamine production, 50 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) pH 7.2 was added. The upper part of the culture, mudless due to the sedimentation, was submitted to repeated enrichments under similar medium and growth conditions. Among the different colony morphotypes of isolates on agar plates, a red-brownish colony was selected for characterization and conserved at −80°C in LB medium with 20% (vol/vol) glycerol.

After DNA purification, the genome sequencing of S. decolorationis LDS1 was carried out at the Molecular Research LP (MR DNA) Laboratory (USA). The library was prepared with a Nextera DNA sample preparation kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s user guide and sequenced with the HiSeq 2500 system (Illumina) as previously described (26).

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The S. oneidensis strain used in this study corresponds to the rifampin-resistant strain MR-1-R (45) and was grown routinely at 28°C in LB medium under agitation. When necessary, chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml) was added. The S. decolorationis LDS1 strain was grown routinely at 28°C in the same medium.

When required, media were solidified by adding 17 g · liter−1 agar. When necessary, TMAO (40 mM) and FeCl3 (1 mM) were added to the medium as alternative electron acceptors. When mentioned, in the presence of TMAO, MOPS (pH 7.2; 25 mM) was added to buffer the growth medium and avoid alkalization by trimethylamine production.

Strains containing either the pBAD33 vector or pdndBCDE plasmid were grown overnight at 28°C in LB medium amended with chloramphenicol (25 μg/ml). S. decolorationis LDS1 was grown under the same conditions except no chloramphenicol was added. They were then diluted to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.1 in fresh LB medium and incubated at 28°C. At an OD600 of 0.7, arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol) was added for 2 h to induce dndBCDE expression. Cells were then diluted to an OD600 of 1, and 2-μl drops of 10-fold serial dilutions were spotted on LB agar plates that contained arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol) but no chloramphenicol, in either the presence or absence of chromate (0.4 mM). The plates were incubated at 28°C.

Physiological characterization.

The growth temperature and salinity ranges were assessed in a Tecan Spark 10M microplate reader in 24-well transparent plates under agitation with a humidity cassette to avoid dehydration. For salinity range determination, growth was carried out at 28°C. During the exponential phase, the exponential growth rates were calculated. Growth at 4°C was tested on agar plates; no growth was detected after 2 months.

Phenotypic characteristics were determined with API 20NE test strips (bioMérieux), incubated at 28 or 40°C. TMAO reduction was assessed by the measure of pH during growth in unbuffered LB medium in the presence of TMAO and spectroscopically at 30°C on crude extracts of the strain grown at 28 or 40°C as described in Lemaire et al. (29). Iron reduction was evaluated by black precipitate formation during growth in the presence of FeCl3.

Dye decolorization.

Decolorization assays were performed in static aerated plastic tubes incubated at 28 or 40°C. Sterile LB medium was amended with 0.001% (wt/vol) crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.005% (wt/vol) Congo red (Sigma-Aldrich), or 0.005% (wt/vol) Remazol brilliant blue (Sigma-Aldrich). These media were either inoculated with S. decolorationis LDS1 preculture in order to reach an OD600 of 0.2 or not inoculated (negative control), and incubation was carried out over ten days. For the inoculated media, cells were removed by centrifugation, and the remaining medium was transferred to a 24-well transparent plate for imaging.

Chromate resistance and reduction.

Chromate solutions were made by dilution of potassium chromate (K2CrO4; Sigma-Aldrich) in deionized water.

For the chromate resistance assay on agar plate, 150 μl of bacterial culture at an OD600 of 0.001 was spread out on an LB agar plate. A sterile cotton patch containing 50 μl of potassium chromate 1 M solution was placed at the center of the plate. Diffusion of the solution in the agar forms a chromate gradient. Lengths of the bacteriostatic halo around the patch for each strain were compared after incubation at 28°C for 12 h.

For the chromate resistance assay on agar plates, recombinant S. oneidensis MR-1 cells were first grown at 28°C until the late exponential phase and then induced for 2 h in the presence of arabinose (0.2%, wt/vol). Bacterial culture (400 μl) diluted to an OD600 of 0.01 was spread out. After a 2 h of incubation, three sterile cotton patches containing 25 μl of potassium chromate (5, 10, and 20 mM) were placed on the plates. Diffusion of the solution in the agar forms a chromate gradient. Lengths of the bacteriostatic halo around the patch for the two strains were compared after 24- and 48-h incubations at 28°C.

Chromate resistance in liquid culture was assayed in LB medium in the presence of 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, or 4 mM potassium chromate. OD600 was measured in a Tecan Spark 10M microplate reader in 24-well transparent plates under agitation at 28 or 40°C and with a humidity cassette to avoid dehydration.

Chromate concentration was measured by the 1,5-diphenyl carbazide (DPC; Sigma-Aldrich) method, slightly modified (24, 46). Briefly, hexavalent chromate was detected in culture supernatant by the colorimetric reaction of a solution of 0.025% (vol/vol) DPC and 0.5% (vol/vol) H3PO4 in deionized water. After a 5- to 10-minute reaction, optical density at 540 nm was measured. Chromate concentration was calculated by comparison to a standard range.

Phylogenetic tree construction.

A classical phylogeny pipeline was used from the phylogeny tool Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7 (MEGA7) (47). The sequences were aligned with MUSCLE (48). The evolutionary history was inferred from the neighbor-joining method (49). The tree with the highest log likelihood (−4,930.1497) is shown (200 replicates). The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary distances were computed using the maximum composite likelihood method (50) and are in numbers of base substitutions per site. The analysis involved 33 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There was a total of 1,128 positions in the final data set.

Homologous genes.

BLAST version 2.6.0 (51) was used to determine if genes from genome A are homologous to genes from genome B. Two genes were considered homologous if the E value hit was lower than or equal to 1e−5. The BLAST results and an R script show the genes present in one, two, or all three Shewanella genomes.

pdndBCDE construction.

To construct the pdndBCDE plasmid, the dnd operon from S. decolorationis LDS1 chromosome with its Shine-Dalgarno sequence was PCR amplified with forward and reverse primers containing the XmaI and SphI restriction sites, respectively. After digestion with XmaI and SphI, the DNA fragment was inserted into the pBAD33 vector, which was digested with the same restriction enzymes. The resulting plasmid was checked by DNA sequencing using several internal primers and then introduced into MR-1-R by conjugation.

Data availability.

The results obtained from this whole-genome shotgun project (SHEWANELLA_DECOLORATIONIS_SESSELENSIS) have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under GenBank accession number CP037898.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Olivier Genest, Michel Fons, and the whole BIP03 team for interesting discussions and Thierry Nivol for the sediment sampling. We are grateful to Scot E. Dowd (Molecular Research LP [MR DNA] Laboratory) for sequencing and assembly of our genome. We acknowledge LABGeM (CEA/IG/Genoscope and CNRS UMR8030) and the France Génomique National infrastructure (funded as part of the Investissement d’avenir program managed by the Agence Nationale pour la Recherche, contract ANR-10-INBS-09) for allowing access to the MicroScope platform.

This work was supported by the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and Aix-Marseille Université (AMU). O.N.L. was supported by a MESR fellowship, AMU and CNRS. We thank the Aix-Marseille Université for supporting S.L. with a visiting professor position (FIR EC 2018). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hau HH, Gralnick JA. 2007. Ecology and biotechnology of the genus Shewanella. Annu Rev Microbiol 61:237–258. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nealson KH, Scott J. 2006. Ecophysiology of the genus Shewanella, p 1133–1151. In The prokaryotes. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fredrickson JK, Romine MF, Beliaev AS, Auchtung JM, Driscoll ME, Gardner TS, Nealson KH, Osterman AL, Pinchuk G, Reed JL, Rodionov DA, Rodrigues JLM, Saffarini DA, Serres MH, Spormann AM, Zhulin IB, Tiedje JM. 2008. Towards environmental systems biology of Shewanella. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:592–603. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao P, Tian H, Li G, Sun H, Ma T. 2015. Microbial diversity and abundance in the Xinjiang Luliang long-term water-flooding petroleum reservoir. MicrobiologyOpen 4:332. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saltikov CW, Cifuentes A, Venkateswaran K, Newman DK. 2003. The ars detoxification system is advantageous but not required for As(V) respiration by the genetically tractable Shewanella species strain ANA-3. Appl Environ Microbiol 69:2800–2809. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.5.2800-2809.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sibanda T, Selvarajan R, Tekere M. 2017. Synthetic extreme environments: overlooked sources of potential biotechnologically relevant microorganisms. Microb Biotechnol 10:570–585. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.12602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suganthi SH, Murshid S, Sriram S, Ramani K. 2018. Enhanced biodegradation of hydrocarbons in petroleum tank bottom oil sludge and characterization of biocatalysts and biosurfactants. J Environ Manage 220:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun W, Xiao E, Krumins V, Dong Y, Xiao T, Ning Z, Chen H, Xiao Q. 2016. Characterization of the microbial community composition and the distribution of Fe-metabolizing bacteria in a creek contaminated by acid mine drainage. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100:8523–8535. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7653-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao J-S, Manno D, Leggiadro C, O’Neil D, Hawari J. 2006. Shewanella halifaxensis sp. nov., a novel obligately respiratory and denitrifying psychrophile. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 56:205–212. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63829-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orellana R, Macaya C, Bravo G, Dorochesi F, Cumsille A, Valencia R, Rojas C, Seeger M. 2018. Living at the frontiers of life: extremophiles in Chile and their potential for bioremediation. Front Microbiol 9:2309. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sekar R, DiChristina TJ. 2017. Degradation of the recalcitrant oil spill components anthracene and pyrene by a microbially driven Fenton reaction. FEMS Microbiol Lett 364. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kakizaki E, Kozawa S, Tashiro N, Sakai M, Yukawa N. 2009. Detection of bacterioplankton in immersed cadavers using selective agar plates. Leg Med Tokyo Jpn 11(Suppl 1):S350–353. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Venkateswaran K, Moser DP, Dollhopf ME, Lies DP, Saffarini DA, MacGregor BJ, Ringelberg DB, White DC, Nishijima M, Sano H, Burghardt J, Stackebrandt E, Nealson KH. 1999. Polyphasic taxonomy of the genus Shewanella and description of Shewanella oneidensis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol 49:705–724. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-2-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Honoré FA, Méjean V, Genest O. 2017. Hsp90 is essential under heat stress in the bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. Cell Rep 19:680–687. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouillet S, Genest O, Jourlin-Castelli C, Fons M, Méjean V, Iobbi-Nivol C. 2016. The general stress response σS is regulated by a partner switch in the Gram-negative bacterium Shewanella oneidensis. J Biol Chem 291:26151–26163. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.751933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouillet S, Genest O, Méjean V, Iobbi-Nivol C. 2017. Protection of the general stress response σS factor by the CrsR regulator allows a rapid and efficient adaptation of Shewanella oneidensis. J Biol Chem 292:14921–14928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M117.781443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu Y, Gao W, Wang Y, Wu L, Liu X, Yan T, Alm E, Arkin A, Thompson DK, Fields MW, Zhou J. 2005. Transcriptome analysis of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 in response to elevated salt conditions. J Bacteriol 187:2501–2507. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.7.2501-2507.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brown SD, Thompson MR, Verberkmoes NC, Chourey K, Shah M, Zhou J, Hettich RL, Thompson DK. 2006. Molecular dynamics of the Shewanella oneidensis response to chromate stress. Mol Cell Proteomics 5:1054–1071. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500394-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Viamajala S, Peyton BM, Apel WA, Petersen JN. 2002. Chromate/nitrite interactions in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1: evidence for multiple hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] reduction mechanisms dependent on physiological growth conditions. Biotechnol Bioeng 78:770–778. doi: 10.1002/bit.10261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barnhart J. 1997. Chromium chemistry and implications for environmental fate and toxicity. J Soil Contam 6:561–568. doi: 10.1080/15320389709383589. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meng Y, Zhao Z, Burgos WD, Li Y, Zhang B, Wang Y, Liu W, Sun L, Lin L, Luan F. 2018. Iron(III) minerals and anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) synergistically enhance bioreduction of hexavalent chromium by Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. Sci Total Environ 640–641:591–598. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myers CR, Carstens BP, Antholine WE, Myers JM. 2000. Chromium (VI) reductase activity is associated with the cytoplasmic membrane of anaerobically grown Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J Appl Microbiol 88:98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Viamajala S, Peyton BM, Apel WA, Petersen JN. 2002. Chromate reduction in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 is an inducible process associated with anaerobic growth. Biotechnol Prog 18:290–295. doi: 10.1021/bp0202968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baaziz H, Gambari C, Boyeldieu A, Ali Chaouche A, Alatou R, Méjean V, Jourlin-Castelli C, Fons M. 2017. ChrASO, the chromate efflux pump of Shewanella oneidensis, improves chromate survival and reduction. PLoS One 12:e0188516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong C, Han M, Yu S, Yang P, Li H, Ning K. 2018. Pan-genome analyses of 24 Shewanella strains re-emphasize the diversification of their functions yet evolutionary dynamics of metal-reducing pathway. Biotechnol Biofuels 11:193. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1201-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baaziz H, Lemaire ON, Jourlin-Castelli C, Iobbi-Nivol C, Méjean V, Alatou R, Fons M. 2018. Draft genome sequence of Shewanella algidipiscicola H1, a highly chromate-resistant strain isolated from Mediterranean marine sediments. Microbiol Resour Announc 7:e00905-18. doi: 10.1128/MRA.00905-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu M, Guo J, Cen Y, Zhong X, Cao W, Sun G. 2005. Shewanella decolorationis sp. nov., a dye-decolorizing bacterium isolated from activated sludge of a waste-water treatment plant. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 55:363–368. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dos Santos JP, Iobbi-Nivol C, Couillault C, Giordano G, Méjean V. 1998. Molecular analysis of the trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) reductase respiratory system from a Shewanella species. J Mol Biol 284:421–433. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.2155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lemaire ON, Honoré FA, Jourlin-Castelli C, Méjean V, Fons M, Iobbi-Nivol C. 2016. Efficient respiration on TMAO requires TorD and TorE auxiliary proteins in Shewanella oneidensis. Res Microbiol 167:630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemaire ON, Infossi P, Ali Chaouche A, Espinosa L, Leimkühler S, Giudici-Orticoni M-T, Méjean V, Iobbi-Nivol C. 2018. Small membranous proteins of the TorE/NapE family, crutches for cognate respiratory systems in. Sci Rep 8:13576. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31851-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yancey PH, Gerringer ME, Drazen JC, Rowden AA, Jamieson A. 2014. Marine fish may be biochemically constrained from inhabiting the deepest ocean depths. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4461–4465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322003111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Banerjee R, Mukhopadhyay S. 2012. Niche specific amino acid features within the core genes of the genus Shewanella. Bioinformation 8:938–942. doi: 10.6026/97320630008938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato C, Nogi Y. 2001. Correlation between phylogenetic structure and function: examples from deep-sea Shewanella. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 35:223–230. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen C-H, Chang C-F, Ho C-H, Tsai T-L, Liu S-M. 2008. Biodegradation of crystal violet by a Shewanella sp. NTOU1. Chemosphere 72:1712–1720. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eckstein F. 2007. Phosphorothioation of DNA in bacteria. Nat Chem Biol 3:689–690. doi: 10.1038/nchembio1107-689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Chen S, Xu T, Taghizadeh K, Wishnok JS, Zhou X, You D, Deng Z, Dedon PC. 2007. Phosphorothioation of DNA in bacteria by dnd genes. Nat Chem Biol 3:709–710. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang L, Chen S, Vergin KL, Giovannoni SJ, Chan SW, DeMott MS, Taghizadeh K, Cordero OX, Cutler M, Timberlake S, Alm EJ, Polz MF, Pinhassi J, Deng Z, Dedon PC. 2011. DNA phosphorothioation is widespread and quantized in bacterial genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108:2963–2968. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017261108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao B, Chen C, DeMott MS, Cheng Q, Clark TA, Xiong X, Zheng X, Butty V, Levine SS, Yuan G, Boitano M, Luong K, Song Y, Zhou X, Deng Z, Turner SW, Korlach J, You D, Wang L, Chen S, Dedon PC. 2014. Genomic mapping of phosphorothioates reveals partial modification of short consensus sequences. Nat Commun 5:3951. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tong T, Chen S, Wang L, Tang Y, Ryu JY, Jiang S, Wu X, Chen C, Luo J, Deng Z, Li Z, Lee SY, Chen S. 2018. Occurrence, evolution, and functions of DNA phosphorothioate epigenetics in bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 115:E2988–E2996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1721916115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bordi C, Ansaldi M, Gon S, Jourlin-Castelli C, Iobbi-Nivol C, Méjean V. 2004. Genes regulated by TorR, the trimethylamine oxide response regulator of Shewanella oneidensis. J Bacteriol 186:4502–4509. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4502-4509.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barchinger SE, Pirbadian S, Sambles C, Baker CS, Leung KM, Burroughs NJ, El-Naggar MY, Golbeck JH. 2016. Regulation of gene expression in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 during electron acceptor limitation and bacterial nanowire formation. Appl Environ Microbiol 82:5428–5443. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01615-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu T, Liang J, Chen S, Wang L, He X, You D, Wang Z, Li A, Xu Z, Zhou X, Deng Z. 2009. DNA phosphorothioation in Streptomyces lividans: mutational analysis of the dnd locus. BMC Microbiol 9:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu T, Yao F, Zhou X, Deng Z, You D. 2010. A novel host-specific restriction system associated with DNA backbone S-modification in Salmonella. Nucleic Acids Res 38:7133–7141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y, Xu G, Liang J, He Y, Xiong L, Li H, Bartlett D, Deng Z, Wang Z, Xiao X. 2017. DNA backbone sulfur-modification expands microbial growth range under multiple stresses by its anti-oxidation function. Sci Rep 7:3516. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-02445-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bordi C, Théraulaz L, Méjean V, Jourlin-Castelli C. 2003. Anticipating an alkaline stress through the Tor phosphorelay system in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 48:211–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, Wei H, Guo S, Wang E. 2008. Selective, peroxidase substrate based “signal-on” colorimetric assay for the detection of chromium (VI). Anal Chim Acta 630:181–185. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. 2016. MEGA7: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol 33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Saitou N, Nei M. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol 4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamura K, Nei M, Kumar S. 2004. Prospects for inferring very large phylogenies by using the neighbor-joining method. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101:11030–11035. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404206101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Camacho C, Coulouris G, Avagyan V, Ma N, Papadopoulos J, Bealer K, Madden TL. 2009. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang M-Q, Sun L. 2016. Shewanella inventionis sp. nov., isolated from deep-sea sediment. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 66:4947–4953. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The results obtained from this whole-genome shotgun project (SHEWANELLA_DECOLORATIONIS_SESSELENSIS) have been deposited at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under GenBank accession number CP037898.