Abstract

Gelatinases are a class of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) that degrade the extracellular matrix (ECM) to regulate intercellular signaling and cell migration. Gelatinase activity is tightly regulated via proteolytic activation and through the expression of tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs). Gelatinase activity has been implicated in retinal pathophysiology in different animal models and human disease. However, the role of gelatinases in retinal regeneration remains uncertain. In this study we investigated the dynamic changes in gelatinase activity in response to excitotoxic damage and how this enzymatic activity influenced the formation of Müller glia progenitor cells (MGPCs) in the avian retina. This study used hydrogels containing a gelatinase-degradable fluorescent peptide to measure gelatinase activity in vitro and dye quenched gelatin to localize enzymatic activity in situ. These data were corroborated by using single cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq). Gelatinase mRNA, specifically MMP2, was detected in oligodendrocytes and non-astrocytic inner retinal glia. Total retinal gelatinase activity was reduced following NMDA-treatment, and sustained inhibition of MMP2 prior to damage or growth factor treatment increased the formation of proliferating MGPCs and c-fos signaling. We observed that microglia, Müller glia (MG), and Nonastrocytic Inner Retinal Glia were involved in regulating changes in gelatinase activity through TIMP2 and TIMP3. Collectively, these findings implicate MMP2 in reprogramming of Muller glia into MGPCs.

Keywords: Müller glia, microglia, gelatinase, MMP2, TIMP2, TIMP3, regeneration

Introduction

The retinal extracellular matrix (ECM) consists of glycoproteins and proteoglycans that are primary components of local cellular microenvironment within the retina. The ECM composition can have a significant impact on intercellular signaling. Signaling pathways that are important for proliferation, migration, and differentiation such as Wnt/β-catenin, sonic hedgehog, and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs) are influenced by ECM mutations of heparan sulfate in Drosophila development (Lin, 2004). The importance of the ECM in retinal function is implicated by collagen mutations manifesting as retinal malformation and dysfunction such as Knobloch’s syndrome (collagen XVIII), Alport syndrome (collagen IV), and Kniest dysplasia (collagen II) (Ihanamäki et al., 2004). The ECM is dynamically modified and replaced through tightly regulated extracellular enzymes known as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs).

MMPs are a family of zinc2+ dependent proteases responsible for the degradation of the extracellular matrix. MMPs can be subdivided into categories by preferred substrates and structures including collagenases, gelatinases, stromelysins, and MT (membrane tethered)-MMPs, and others (Iyer et al., 2012; Nagase et al., 2006). Regulation of MMP enzymatic activity is required for appropriate physiologic function. The kinetics of enzymatic activity of MMPs are regulated by phosphorylation, proteolysis, and expression of endogenous glycoprotein tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases (TIMPs) (Chakraborti et al., 2003; Nagase and Woessner, 1999). MMP2 and MMP-9 are secreted as pro-enzymes with fibronectin like repeats and a zinc-dependent catalytic domains that have substrate specificity for gelatin, fibronectin, and collagen IV & V (Nagase et al., 2006). MMPs have been studied during ocular development in frog (Xenopus laevis), zebrafish (Danio rerio), and chicken (Gallus domesticus) animal models (Fitch et al., 2005; Hehr et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2003). Abnormal MMP function has been implicated in retinal disease. For example, Sorby’s macular dystrophy, an autosomal dominant form of early macular degeneration in humans, can result from a mutation in TIMP3 (Christensen et al., 2017; Qi et al., 2002). Gelatinase activity has also been implicated in other ocular pathology such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, corneal neovascularization, and uveal melanoma metastasis (Logan et al., 2007; Mohammad and Kowluru, 2010; Sahay et al., 2017; Väisänen et al., 1999).

There may be important roles for gelatinases in neurogenesis and glial reprogramming in the formation of Müller glia-derived progenitor cells (MGPCs). Müller Glia (MG) serve as the primary macroglia of the retina providing neuronal support including potassium siphoning, neurotransmitter recycling, bicarbonate regulation, osmotic balance, structural support, and more (Bringmann et al., 2006; Reichenbach and Bringmann, 2013). Importantly, MG are capable of reprogramming into retinal progenitor cells and undergo neurogenesis to replace damaged neurons (Goldman, 2014). The capacity for neurogenesis, however, is species-specific. Damage to mouse retina fails to elicit significant glial reprogramming and neuronal regeneration, whereas damage to zebrafish retina results in wide-spread reprogramming of MG into progenitors that are capable of regenerating functional retinal tissue (Karl and Reh, 2010; Wan and Goldman, 2016). Chick MG have an intermediate capacity for reprogramming where MG form proliferating MGPCs with limited neurogenesis, serving as an ideal model for determining inhibiting and potentiating factors of retinal regeneration (Fischer, 2005; Fischer and Reh, 2001; Gallina et al., 2014).

MMPs have been implicated in the reprogramming of MG. For example, epidermal growth factor (EGF) is secreted as a propeptide that requires MMP proteolytic activation, and the proliferative effect of EGF is inhibited by pan-MMP inhibitor GM6001 and restored with active EGF (Wan et al., 2012). Similarly, MMP-9 has increased expression in zebrafish retina 24 hours after injury and increases expression of ASCL1a (Achaete-Scute Homologue-1), a transcription factor that is required for the formation of MGPCs (Kaur et al., 2018). In Xenopus regeneration models, inhibition of MMPs suppresses the proliferation of the RPE in the formation of neuroepithelial tissue (Naitoh et al., 2017). In the avian retina, the expression and function of gelatinases are poorly characterized and have not been studied in the context of retinal regeneration.

In this study, we characterize TIMP and MMP expression and gelatinase activity in the chick retina. Furthermore, we investigate changes in gelatinase expression and activity in response to excitotoxic retinal damage. Collectively, our findings indicate that glia produce MMP2, TIMP2, and TIMP3. Interestingly, gelatinase activity decreased after retinal damage. MG were found to increase the expression of TIMP2 after damage that was localized to rod bipolar cells. Intraocular injections of gelatinase inhibitors increased the formation of proliferating MGPCs in damaged and FGF2-treated retinas.

Materials and methods

Animals:

Animals used in this study were managed in accordance with the guidelines provided by the NIH and IACUC at the Ohio State University. All chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus; white leghorn strain) were obtained at P0 from Meyer Hatchery (Polk, Ohio). The chicks were housed in a stainless-steel brooder maintained at 25°C with a 12-hour light and dark cycle (8am-8pm). Chicks were fed water and Purina chick starter ad libitum.

Preparation of clodronate liposomes:

The production of clodronate liposomes was modified from previous descriptions (Van Rooijen, 1989; Zelinka et al., 2012). Briefly, 8 mg of L-α-Phosphatidyl-DL-glycerol sodium salt (Sigma P8318) was dissolved in chloroform. 50 mg of cholesterol dissolved in chloroform was added to the lipids and evaporated under nitrogen/vacuum with frequent shaking to create a thin lipid-film on a round bottom flask. 158 mg dichloro-methylene diphosphonate (clodronate; Sigma-Aldrich) in sterile PBS was added and mixed. To facilitate lipid rehydration, the vial was vortexed for 5 minutes. To normalize lipid vesicle size, the mixture was sonicated at 42,000 Hz for 6 minutes. The liposomes were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 minutes, aspirated, and resuspended in 150 µl PBS. While there is some loss of liposomes during the purification, the dosage has been tittered such that >99% of the microglia are ablated 2 days after administration.

Intraocular injections:

Intraocular injections of anesthetized chickens were conducted as previously described (Fischer et al., 1998, 2009). Briefly, prior to injection chicks were anesthetized via inhalation of 2.5% isoflurane and oxygen. The right eye was treated with experimental compound and the contralateral left eye received vehicle control in each paradigm. Each injection was 20 µl with the addition of 0.05 mg/ml bovine serum albumen as a carrier for dilute recombinant protein injections. Information and concentrations of all compounds injected into the eyes of the chicks is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Injectable drugs. The following compounds were injected into the chick eye and include the manufacturer, catalog number, and dosage.

| Drug | company | product number | dosage (1dose = 20μl) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine (Edu) | ThermoFischer | A10044 | 2μg/dose |

| FGF2 | R&D Systems | 234-FSE | 250ng/dose |

| SB-3CT | Cayman Chemical | 292605–14-2 | 120μM/dose |

| MMP2i-II | Cayman Chemical | 869577–51-5 | 120μM/dose |

| MMP9i-I | Cayman Chemical | 206549–55-5 | 120μM/dose |

| recombinant TIMP2 | Abcam | ab125639 | 250ng/dose |

ScRNA-seq

Chick retinas were dissected, the pigmented epithelium was carefully removed, and dissociation performed in a 0.25% papain solution of Hank’s balanced salt solution, pH = 7.4, for 30 minutes with frequent trituration. Dissociated cells were assessed for viability and density and diluted to 700 cell/µl with the goal establishing a single cell cDNA library of 10,000 cells per preparation. Cells and Chromium Single Cell 3’ V2 reagents (10X Genomics) were loaded onto chips for nanodroplet packaging in the 10x Chromium Controller. In accordance with 10x Genomics instructions, cDNA and library amplification was achieved by 12 and 10 cycles respectively. Sequencing was conducted on Illumina HiSeq2500 (Genomics Resource Core Facility, John’s Hopkins University) with 26 bp for Read 1 and 98 bp for Read 2. Fasta sequencing files were aligned, de-multiplexed, annotated to the ENSMBLE database, counted for expression levels, and gene-cell matrices were constructed. Using Cell Browser software (10x Genomics), t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) plots were generated from aggregates of multiple scRNA-seq libraries. Compiled in each tSNE plot are two biological replicates for saline injected retinas, 24 hrs, 48 hrs, and 72 hrs after NMDA damage. Identification of different types of retinal cells that were clustered together in tSNE plots was accomplished by probing for well-established cell-distinguishing genes. Seurat was used to construct violin/scatter plots (Butler et al., 2018) and Monocle was used to construct pseudo-time trajectories and scatter plotters for Müller glia and MGPCs (Qiu et al., 2017a, 2017b; Trapnell et al., 2014).

Fixation, sectioning and immunocytochemistry

Retinal samples were fixed, sectioned, and immunolabeled as previously described (Fischer et al., 2008; Gallina et al., 2014, 2015). All primary antibodies used in this study are described in Table 1. The following secondary antibodies are included in this study: donkey-anti-goat-Alexa488/568, goat-anti-rabbit-Alexa488/568 and goat-anti-mouse-Alexa488/568/647 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Secondary antibodies are diluted in pH 7.4 PBS plus 0.2% Triton-X and washed in pH 7.4 PBS. Secondaries did not produce non-specific labeling in the retina and tissue sections were devoid of autofluorescence.

Table 1.

Immunostaining Antibodies. The following were used in this study and include the manufacturer, product number, host, clonality, and dilution factor.

| antibody | company | product number | host | clonality | dilution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOX2 | R&D Systems | AF2018 | goat | polyclonal | 1:500 |

| Glutamine synthetase | BD Transduction Laboratories |

610517 | mouse | polyclonal | 1:1000 |

| serotonin | abcam | ab66047 | goat | polyclonal | 1:100 |

| PKC-alpha | BD Transduction Laboratories |

610108 | mouse | polyclonal | 1:50 |

| TIMP2 | abcam | rabbit | rabbit | polyclonal | 1:100 |

| AP2-alpha | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank |

AB_2313948 | mouse | monocolonal (3B5) | 1:1000 |

Tissue encapsulation and measurement of MMP activity

Each retina was cut into three replicates of 2 mm × 2 mm and weighed using an analytical balance. A hydrogel precursor solution was prepared as described previously with slight modification (Leight et al., 2013). Briefly, eight-arm 40-kDa poly (ethylene) glycol hydroxyl (JenKem Technologies) was functionalized with 5-norbornene-2-carboxylic acid (Sigma) to form poly (ethylene) glycol-norbornene (PEG-NB) (Fairbanks et al., 2009). The PEG-NB (20 mM) macromer was crosslinked with a bicysteine MMP-degradable peptide (KCGPQG↓IWGQCK, 10.75 mM peptide; GenScript) in the presence of the photoinitiator, lithium phenyl-2, 4, 6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP, 2 mM). CRGDS (GenScript), a cell adhesion peptide, was also included at a concentration of 1 mM. MMP activity was measured by incorporation of a MMP-degradable peptide (GGPQG↓IWGQKDde(PEG)2C, 0.25 mM) conjugated with a fluorophore (Fluorescein; Life Technologies) and quencher (Dabcyl; AnaSpec) pair. Ten microliters of the hydrogel precursor solution were pipetted into a 96-well, round-bottom, black plate (BrandTech). Tissue samples were immersed into the hydrogel solution and polymerized under 4 mW/cm2 UV light (365 nm) for 3 min. 150 µL of DMEM:F12 media (Life Technologies) supplemented with 1% (v/v) charcoal-stripped FBS (VWR), 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 1% L-glutamine were added to each well. Plates were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. 18 hours post-encapsulation, AlamarBlue (LifeTechnologies) reagent (1:10) was added to each well to measure tissue metabolic activity. Fluorescence measurements of the MMP-degradable peptide (494 nm excitation/521 nm emission) and AlamarBlue (560 nm excitation/590 nm emission) were made simultaneously in each well at 24 hours after encapsulation with a 3 × 3 well scan using a Molecular Devices SpectraMax M2 spectrophotometer. Readings of average fluorescence intensity were calculated for each well scan and the background reading (peptide-functionalized gels containing no tissue samples) was subtracted. All fluorescence intensity measurements were normalized to sample mass or metabolic activity and averaged between replicates.

In situ zymography staining

Retinal tissue was fixed for 48hrs at room temperature (RT) in zinc-based fixative consisting of 36.7mM ZnCl2 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 27.3mM ZnAc2 × 2H2O (MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA), and 0.63mM CaAc2 (Spectrum Chemical MFG Corp, New Brunswick, NJ) dissolved in 0.1M Tris-HCl (Sigma-Aldrich), pH 7.4. OCT embedded retinas were sectioned (20 µm), air dried at RT for at least one hour, and rinsed with deionized water to remove excess OCT. Sections were then incubated in a humidity chamber at 37°C for 1hr with either 200µM 1,10-Phenanthroline (Sigma-Aldrich) diluted in water (MMP inhibitor control), or at 4°C for 1hr (temperature control). After incubation, solutions were removed and 20µg/mL fluorescein conjugated dye quenched (DQ) gelatin from pig skin (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), ±200µM 1,10-Phenanthroline, was diluted in reaction buffer [10mM Tris-HCl, 30mM NaCl (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), 1mM CaCl2 (Fisher Scientific), and 0.04mM sodium azide (Fisher Scientific). Sections were then incubated at 37°C or 4°C for 2hr in a dark humidity chamber. Slides were rinsed in water then fixed with 4% neutral buffered formalin for 10min at RT and then rinsed with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, Gibco, Waltham, MA) twice, for 2min each. Nuclei were then stained with 1:1000 Hoechst 33342 (Life Technologies) in PBS for 30min at RT. Slides were mounted using ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

Photography, measurements, cell counts and statistics:

Microscopy images were captured with the Leica DM5000B microscope with epifluorescence and the Leica DC500 digital camera. Confocal images were obtained with a Leica SP8 in The Department of Neuroscience Imaging Facility at The Ohio State University. Representative images have enhanced color, brightness, and contrast for improved clarity using Adobe Photoshop. In proliferation assays, a fixed area of retina was captured and quantified for Sox2 and Edu colocalization. The region of the retina was selected and standardized between treatment and control groups to reduce variability and improve reproducibility.

For quantifying changes in context specific protein expression, densitometry measurements of fluorescent immunohistological stains were compared. Within each image, the retina was stratified into the photoreceptor layer (PRL), outer (photoreceptor) nuclear layer (ONL), outer plexiform layer (OPL), inner nuclear layer (INL), inner plexiform layer (IPL), ganglion cell layer (GCL), and the nerve fiber layer (NFL). Within each layer, a region of retina was selected and mean pixel intensity (0–255) was derived. This process was repeated 3 times within each selected image, and the whole process was repeated for each biological replicate. ImagePro 6.2, ImageJ, and Microsoft Excel were used for data and calculations respectively.

To calculate changes in spatial distribution, the image was subjected to a consistent threshold value to remove background. The average area of distribution beginning at the IPL bordering the INL was derived and plotted for each pixel throughout the layer for each retina. The relative distance of each pixel was derived from the confocal scalebar corresponding to the magnification and image resolution. All data was calculated using ImageJ.

For statistical evaluation of differences in treatments, a two-tailed paired T-test was applied for intra-individual variability where each biological sample also served as its own control. For two treatment groups comparing inter-individual variability, a standard two-tailed unpaired T-test was applied. For multivariate analysis, an ANOVA with the associated Tukey Test was used to evaluate any significant differences between multiple groups.

Results

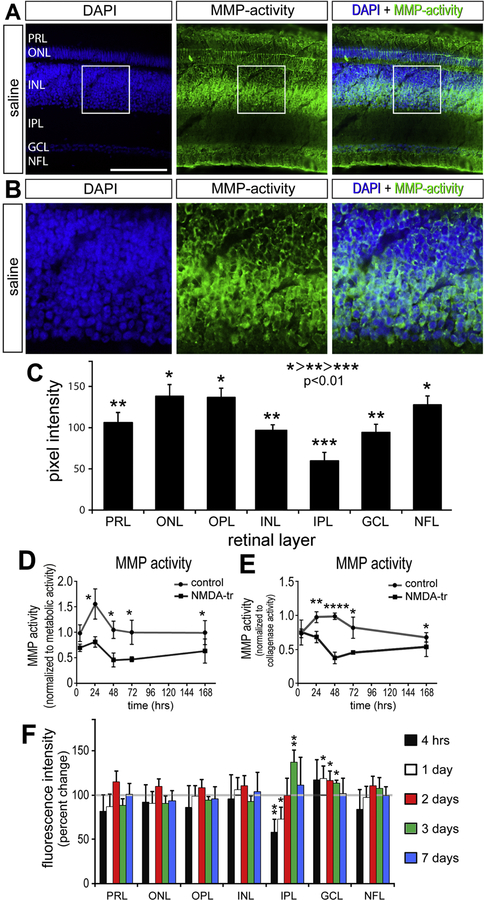

Gelatinase activity decreases in the NMDA damaged chick retina

MMPs have been characterized in both physiologic and pathologic models of retinal disease. MMPs are translated as pro-peptides subject to complex and dynamic regulation including trafficking, proteolytic activation, enzymatic inhibition, and degradation. We directly measured gelatinase activity in tissue sections of the retina using in situ zymography (Fig. 1). MMP activity was localized to specific layers of the retina using in situ zymography where DQ-gelatin was cleaved (Fig. 1A). For example, within the inner INL there was elevated gelatinase activity corresponding to the location of cell bodies of Müller glia and amacrine cells (Fig. 1B). Across multiple biological replicates, gelatinase activity was stratified into three relative levels of activity – high, medium, and low (Fig. 1C) – that were significantly different from each other (p <0.05). The highest gelatinase activity was found in the ONL, IPL, and NFL, followed by the PRL, INL, and GCL. The lowest level of MMP activity was found in the IPL.

Figure 1:

Gelatinase activity decreases in the retina after NMDA damage. Sections of normal, untreated retinas were incubated with DQ-gelatin which fluoresces when cleaved by MMP2/9 (A). Within the INL is a bistratified layer of MMP activity observed paracellularly when costained with DAPI (B). Fluorescent intensity was quantified via densitometry to compare relative gelatinase activity (C) (n = 20). For simplicity, intensity is ranked with *>**>*** where p < 0.01 (C). Gelatinase activity was measured at various time points after NMDA-treatment. Each retina was horizontally hemisected for in vitro and in situ MMP activity measurements. Retinal tissue is imbedded in a hydrogel containing MMP 2/9 sensitive fluorescent peptides and normalized to metabolic activity (D) or collagenase activity (E) for direct comparison with tissue from saline vehicle injected eyes (n = 4). The remaining retina is cryo-sectioned and incubated in DQ peptide for region specific MMP activity measurements (F). Scale bar = 50µm. Error bars ± 1 SE (F) or ± 1 SD (C, D, E), with significance of difference determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

We investigated how gelatinase activity may change in the retina following NMDA-induced damage. Retinal tissue was incubated in a fluorescein conjugated DQ-peptide hydrogel that measured changes in gelatinase enzymatic activity through spectrophotometry. Retinal tissue gelatinase activity was unchanged 4 hours after damage in vitro, but steadily decreased over the following 48 hours relative to that seen in saline-treated controls (Fig. 1D, E). Gelatinase activity began to increase after 48 hours but remained reduced at 7 days after damage when measured against saline injected retinas (Fig. 2D,E). This trend was consistent when data was standardized to total tissue metabolic activity or collagenase enzyme activity (total matrix degradation, positive control).

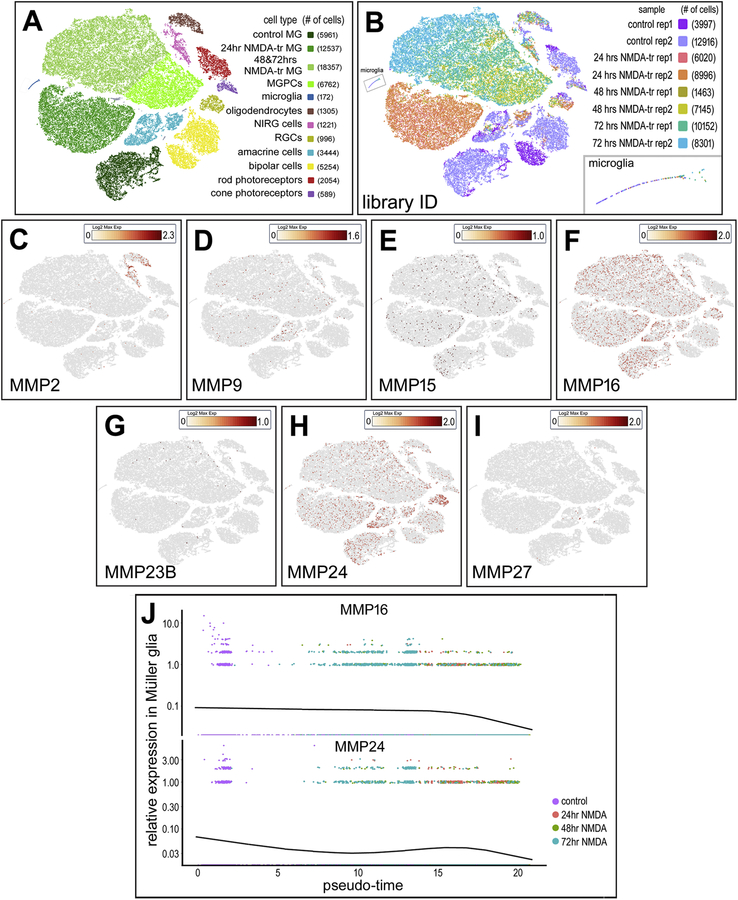

Figure 2.

Patterns of MMP and TIMP expression in the avian retina after NMDA damage. ScRNA-seq is used to identify gene expression in acutely dissociated retinal cells. Two replicates are taken from control retinas (rep-1 3997 cells, rep-2 12916 cells) and 24hrs (rep-1 6020 cells, rep-2 8996 cells), 48 hrs (rep-1 1463 cells, rep-2 7145 cells), and 72 hrs (rep-1 10152 cells, rep-2 8301 cells) after NMDA damage (A). tSNE plots reduce the dimensionality of the data and organizes unbiased clusters on global gene expression. Cluster identity is determined by hallmark gene expression. Microglia (172 cells), rods (2054 cells), cones (589 cells), oligodendrocytes (1305 cells), Non-astrocytic inner retinal glia (NIRG) (1221 cells), amacrine cells (3444 cells), bipolar cells (5254 cells), Müller glia (36588 cells), and Müller glia derived progenitors (6762 cells) are identified in these clusters (B). Müller glia were identified by collective expression of LHX2, SOX9, RLBP1, and SLC1A3. Oligodendrocytes were identified by FGFR2, TGFB3, OLIG2, SOX10. NIRGs are identified and differentiated from oligodendrocytes by NKX2.2, PTPRZ1, SIX6. In this scRNA library, heatmap panels are presented demonstrating MMP2 (C), MMP9 (D), MMP15 (E), MMP16 (F), MMP23B (G), MMP24 (H), and MMP27 (I) expression. Each dot is a cell where the color is a heat map with yellow = low expression, deep red = high expression, and grey = no expression. MMP16 and MMP24 expression is tracked across pseudotime in MG (J). Pseudotime represents the transition of MG to MGPCs after NMDA damage. The pseudotime trajectory was established for pseudotime states of different groups of variable genes, thereby establish a trajectory of resting Muller glia (high levels of mature glial markers, low levels of MGPC markers) to the left, and MGPCs (low levels of mature glial markers, high levels of MGPC markers) to the right.

In situ techniques were performed to determine layer-specific changes in gelatinase activity. Densitometry measurements of gelatinase activity across all layers of the retina were not sensitive enough to detect significant changes after NMDA damage (data not shown). To investigate further, measurements of gelatinase activity were performed for each retinal layer after NMDA damage. In the IPL at the 4 and 24 hours after damage, gelatinase activity was decreased, but later increased at 72 hours after damage (Fig. 2F). Conversely, gelatinase activity in the GCL was slightly elevated 24, 48, and 72 hours after damage (Fig. 2F). At the 7-day time point, gelatinase activity across all layers was not significantly different to that of the control undamaged retinas (Fig. 2F).

Single-cell RNA-seq: MMPs and TIMPs in normal and damaged retinas

To identify the different cell types that express gelatinases and other MMPs in the avian retina, we created scRNA-seq libraries of control and NMDA-damaged retinas (Fig. 2). Each library of undamaged and NMDA damaged retinas consisted of two biological replicates. For tSNE plot analysis, an aggregate library was generated consisting of control undamaged retinas and retinas collected 24, 48, and 72 hours following NMDA damage. Using well-established cell markers, tSNE-clustered cells were identified as different types of retinal cells (Fig. 2A,B). Different types of MMPs were detected in the different types of cells in the chick retina. Of note, MMP2 was identified in NIRG cells and oligodendrocytes, whereas MMP-9 was only detected at low levels in amacrine, NIRG cells, and Müller glia (Fig. 2C,D). Although reports have previously claimed that microglia are a source of gelatinases in the CNS in response to ischemia and inflammation (Könnecke and Bechmann, 2013), our scRNA-seq library indicates that microglia are not the primary source of MMP2 in the retina.

Other MMPs detected in the chick retina included membrane bound MMPs 15, 16, and 24 (MT2, MT3, MT5-MMP) in Müller glia and different neuronal cell types at lower levels (Fig. 2E–I). The expression of MMP16 and MMP24 was seen at detection threshold for the 10X V2 reagents and was only observed in a small proportion of MG in control, 24hr, 48hr, and 72hrs after damage. The proportion of MG positive for MMP16 and MMP24 did not change after damage (4.24% and 2.78% of MG for MMP16 and MMP24 respectively). While MMP24 was always observed at low levels, the proportion of positive cells was noticeably increased in amacrine and ganglion cells (6.16% and 17.17% respectively). Pseudotime analysis indicated that the relative levels of MMP16 and MMP24 expression were higher in resting and activated Müller glia, but decreased along the pseudotime trajectory toward MGPCs (Fig. 2J). Lastly, MMPs 7, 11, 13, and 28 showed no expression in any cell type.

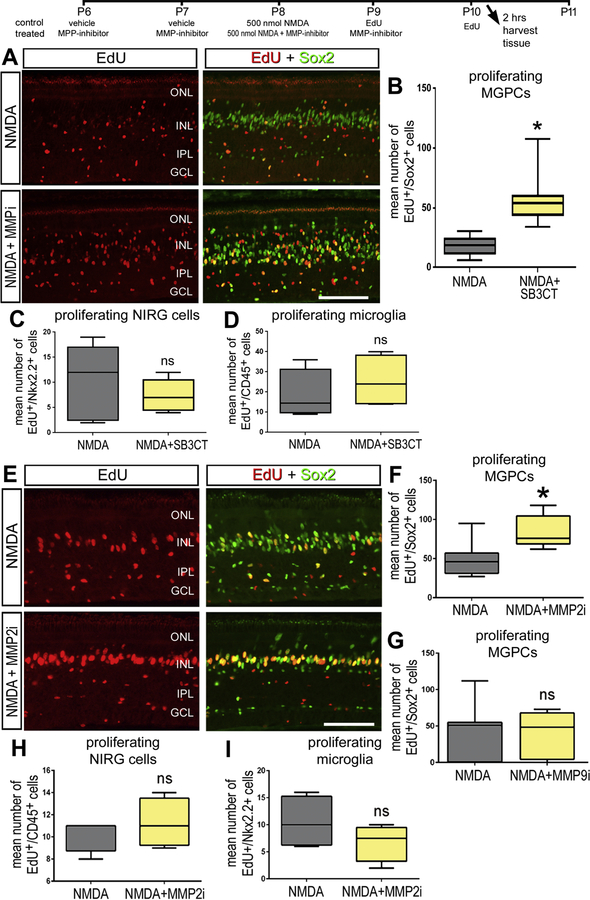

Inhibition of gelatinases enhances MGPC proliferation.

Since we observed transient decreases in gelatinase activity following NMDA damage, where MGPCs are known to form, we investigated whether gelatinase inhibitors affected the reprogramming of Müller glia in to proliferating MGPCs. Administration of gelatinase inhibitor SB-3CT at the time of damage did not influence the formation of MGPCs (data not shown). By comparison, administration of SB-3CT prior to damage significantly increased numbers of proliferating MGPCs (Fig. 3A,B). This proliferative effect was only seen in Müller glia, and not NIRG cells or microglia (Fig. 3C,D). Similarly, the MMP2-specific inhibitor MMP2i II applied before NMDA resulted in significant increases in numbers of proliferating MGPCs, whereas the proliferation of NIRG cells and microglia was unaffected (Fig. 3E,F,H,I). By contrast, the MMP-9 specific MMP-9i-I inhibitor had no significant effect upon the proliferation of cells in damaged retinas (Fig. 3G).

Figure 3.

Gelatinase inhibitors SB-3CT and MMP2i II increase Müller glia proliferation after NMDA damage. Avian retinas are injected intravitreally with a combination of NMDA and SB-3CT (A). Retinas with MMP inhibitor treatment are given inhibitor injections 2 days prior to NMDA damage and harvested 2 days after NMDA damage. Retinal sections are co-labeled with Edu (red) and Sox2 (green) and colocalize on Müller glia derived progenitors and quantified (B). Proliferation of NIRG (C) and microglia (D) are quantified by colocalization of Edu and NKX 2.2 and CD45 respectively. The experimental paradigm was replicated with MMP 2i II (E) and Müller glia, NIRG, and microglia proliferation was quantified by colocalization of Edu (red) and Sox2 (green, F), NKX2.2 (H), and CD45 (I) respectively. When injected with the MMP-9 specific inhibitor (MMP-9i), no proliferation changes were observed (G). Significance was determined by a Student’s T Test (n = 6) with *p < 0.05. Error bars are ± 1 SD. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer.

In the retina, damage can induce dramatic changes in extracellular matrix which may lead to an effect of NMDA only in the context of retinal cell death. With both SB-3CT and MMP2i-II, cell death was measured by terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) and ratio of ONL/INL thickness (Fig. S2). There was no influence on amacrine cell death compared to control.

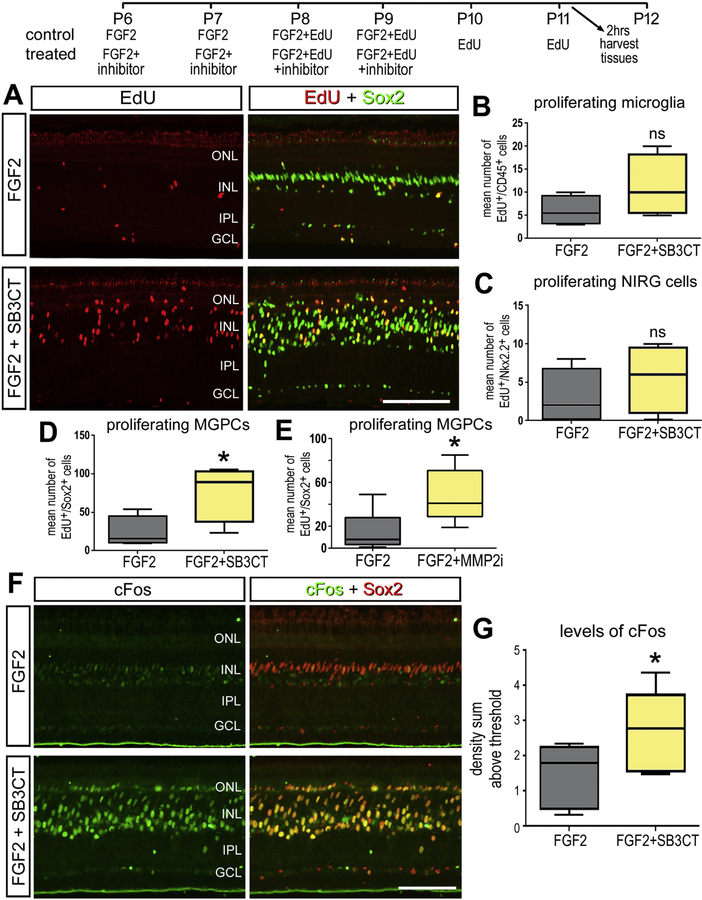

Provided that reducing gelatinase activity increased proliferation in response to NMDA damage, we sought to investigate how reducing gelatinase activity influences the formation of proliferating MGPCs in retinas treated with FGF2 in the absence of damage. The combination of insulin and FGF2 is known to induce a wave of MGPC formation, initiating at the far periphery of the retina (Fischer and Bongini, 2010; Fischer et al., 2002). Using a similar injection paradigm, both SB-3CT and MMP2i II inhibitors resulted in significant increases in numbers of proliferating MGPCs in FGF2-treated retinas (Fig. 4A,B,C). The proliferation of NIRG cells and microglia was not affected by the MMP inhibitors (Fig. 4D,E). In conjunction with the observation of increased proliferation, FGF2 treated retinas showed an increase response of cFos expression in Müller glia after the treatment of SB-3CT (Fig. 4F,G).

Figure 4.

Gelatinase inhibitors SB-3CT and MMP2i II increase Müller glia proliferation after FGF2 treatment. Avian retinas were injected intravitreally with a combination of FGF2 and SB-3CT or MMP2i II over 4 days (A). Retinal sections are labeled with Edu (red) and Sox2 (green) and colocalize on Müller glia derived progenitors. The number of progenitors in a fixed area of the retina are counted and quantified (B, C). Proliferation of microglia (D) and NIRG (E) are quantified by colocalization of Edu and NKX 2.2 and CD45 respectively. cFos signaling with FGF2 and SB-3CT treatment was measured by colocalization of cFos (green) and Sox2(red) in nuclei (E). The density intensity sum in Sox2+ nuclei is quantified (F). Significance was determined by a Student’s T Test (n = 6) with *p < 0.05. Error bars are ± 1 SD. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer.

TIMP expression in damaged retinas and the formation of MGPCs:

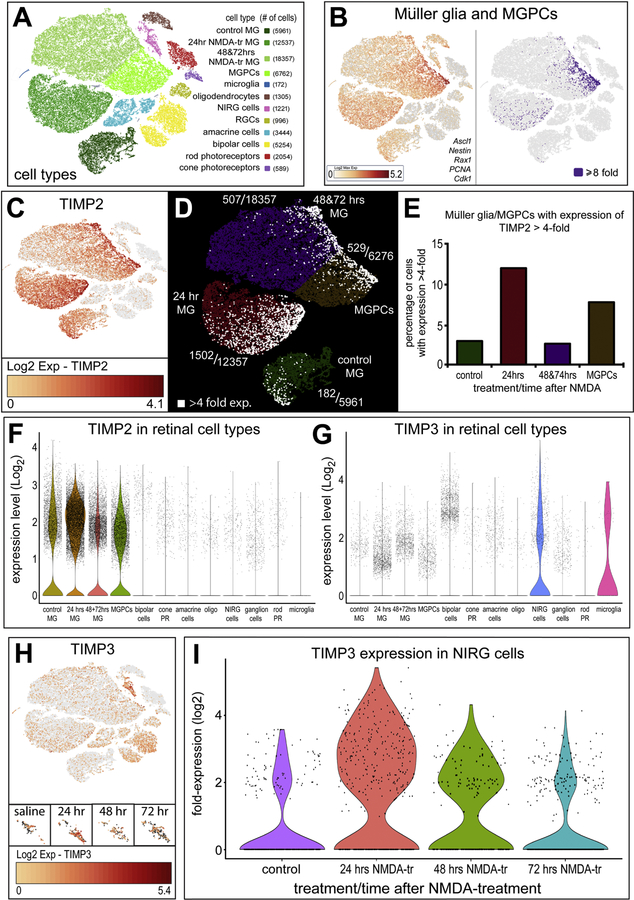

Observing the high expression of TIMP2 and TIMP3 mRNA in the retina, we investigated changes in mRNA expression following damage in both Müller glia and NIRG populations (Fig. 5). The scRNA-seq retinal library revealed distinct cell types from clustering in a tSNE plot (Fig. 5A). Müller glia to MGPCs were identified based on elevated expression of Ascl1, Nestin, Rax1, PCNA, and Cdk1 (Fig. 5,B). The aggregate tSNE plot included two biological replicates of undamaged, 24, 48, and 72 hours following NMDA damage. TIMP2 expression in each cell is displayed as a heat map with deep red indicating high expression on a log2 scale from 0 to 4.1 (Fig. 5C). Müller glia with expression levels above 4-fold are labeled white, showing an increased population of high expression TIMP2 in Müller glia 24 hrs after damage and in forming MGPCs (Fig. 5D,E,F,G). Similarly, TIMP3 expression increased in NIRG cells after damage, with the greatest population of NIRGS expressing TIMP3 24 hours after NMDA damage (Fig. 5H,I).

Figure 5.

Müller glia and NIRGs secrete TIMPs in response to NMDA damage. Sc-RNA was used to identify gene expression in acutely dissociated retinal cells. tSNE plots reduce the dimensionality of the data and organizes unbiased clusters on global gene expression. Cluster identity are identified by hallmark gene expression. Microglia (172 cells), rods (2054 cells), cones (589 cells), oligodendrocytes (1305 cells), Non-astrocytic inner retinal glia (NIRG) (1221 cells), amacrine cells (3444 cells), bipolar cells (5254 cells), Müller glia (36588 cells), and Müller glia derived progenitors (6762 cells) were identified in these clusters (A). Müller Glia were identified by collective expression of LHX2, SOX9, RLBP1, and Slc1a3. Progenitors were segregated to its own cluster by collective expression of Ascl1, Nestin, Rax1, PCNA, and Cdk1 (B). TIMP2 expression in Müller glia is represented on a heat map (C), with RNA levels ranging from 0 to ~17-fold over bassline reads per cell. Cells with transcriptional levels >4-fold are highlighted in each cluster (D) and the relative population of TIMP2 overexpression was quantified (E). TIMP3 expression is shown in the tSNE heat map (F), with expression ranging from 0 to ~42-fold over baselines reads per cell. Oligodendrocytes were identified by FGFR2, TGFB3, OLIG2, SOX10. NIRGs are identified and differentiated from oligodendrocytes by Nkx2.2, PTPRZ1, Six6. The NIRG clusters overlap significantly with control and treatment groups, and are separated to show relative TIMP3 expression at each time point. NIRG populations expressing >log2(x) expression are quantified (G).

TIMP2 localizes to inner retinal neurons and is altered after NMDA damage.

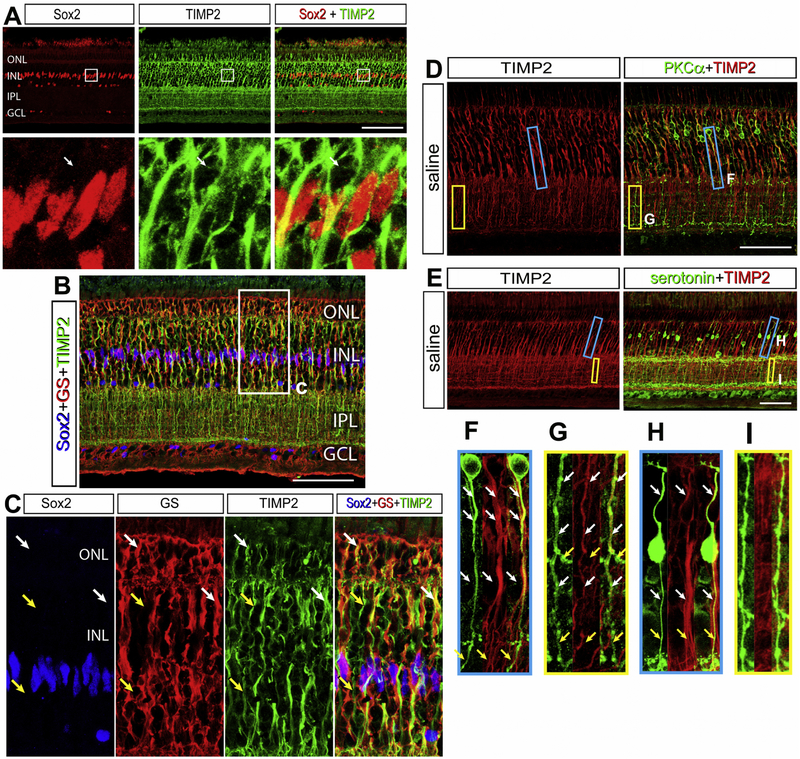

TIMP2 mRNA was high in Müller glia and the expression was increased after NMDA damage. Since TIMPs are secreted from cells, we used antibodies to investigate where these proteins might act (Cawston et al., 1983; Howard et al., 1991; Welgus et al., 1985). TIMP2 is a secreted protein and has been associated with cell surface proteins with local MMP inhibition (Butler et al., 1998; Emmert-Buck et al., 1995; Itoh et al., 1998). In undamaged chick retina, TIMP2-immunolabeling is localized to every layer of the retina except the PRL, GCL, and the NFL (Fig. 6A). While TIMP2 mRNA was detected predominantly in Müller glia, TIMP2 protein was localized predominantly to neuronal cells (Fig. 6A). Low levels of TIMP2-immunoreactivity were colocalized in regions of GS-positive Muller glia, most notably in the sclerad half of the INL and MG end feet projections into the ONL (Fig. 6B,C). With this exception, TIMP2 demonstrated the highest intensity on neuronal cells, and did not display MG process morphology or GS colocalization in the IPL.

Figure 6.

TIMP2 colocalizes to the cell surface of MG and PKCα bipolar cells. The retina was co-stained with Sox2 (red) and TIMP2(green) differentiating MG from other cell bodies in the INL (A). A portion of the retinal section is enlarged within the white box below the image. The white arrow indicates a TIMP2+ neuronal cell body with a Sox2− nucleus and TIMP2+ axonal projection. TIMP2 expression in MG is identified with immunolabelling colocalization of Sox2 (blue), glutamine synthetase (GS, red), and TIMP2 (green) (B). A portion of the retinal section is enlarged within the white box below the image, with white arrows identifying GS colocalization with TIMP2 and the yellow arrows labeling TIMP2 absent of MG markers (C). To determine the neuronal subtype colocalized with TIMP2 in the INL and IPL that are not MG, bipolar populations were labeled. Rod bipolar cells were identified with PKCα (D) and a subset of cone bipolar cells with serotonin (E). Regions of the INL (blue) and IPL (yellow) are selected to demonstrate TIMP2+ overlap for PKCα (F, G) and serotonin (H, I). Fasciculations of bipolar cell axons in the INL stain positive for TIMP2, where only PKCα processes are positive for TIMP2 in the IPL. White arrows indicate regions of TIMP2+ overlap, where yellow arrows show TIMP2− regions. Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer. Scale bar = 50µm.

Because bipolar cell projections travel in fasciculi through the INL, it is challenging to delineate bipolar cell subsets that colocalize with TIMP2. Bipolar cells that accumulated serotonin did not display TIMP2-immunoreactivity on projections in the INL or IPL (Fig. 6D,E). While there was TIMP2 overlap within a fasciculus, tracking individual neurite projections did not colocalize with TIMP2 (Fig. 6F,G,H,I). Into the IPL there was little to no overlap and serotonergic bipolar cells which terminated on a different ON layer than the TIMP2 positive bipolar cells. PKCα, a rod specific bipolar cell marker, was found to co-label for TIMP2 in both the INL and the IPL (Fig. 6F,G,H,I). These patterns were quantifiably consistent among many bipolar cell projections across the retina (SFig. 3).

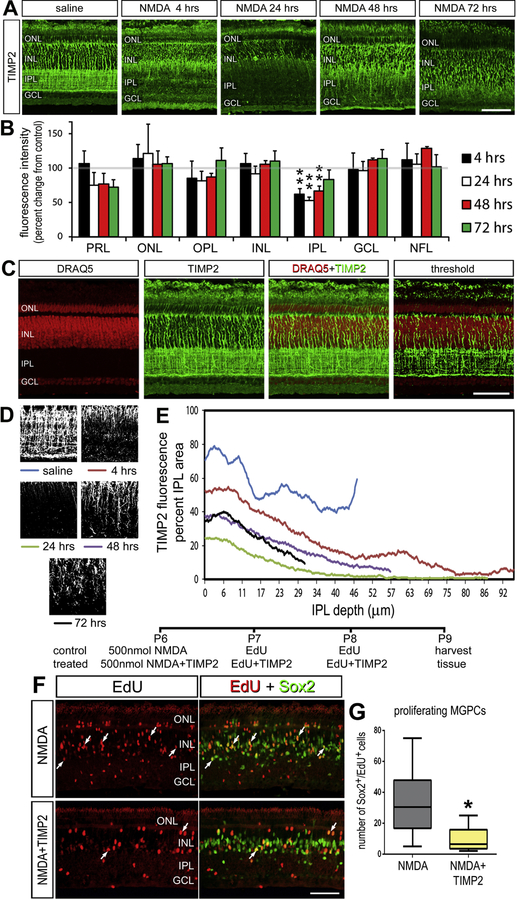

TIMP2 protein is cleared from the IPL early after NMDA damage

The pattern of TIMP2 localization was significantly altered in the IPL from 4 to 48 hours after NMDA damage (Fig. 7). 24 hours after damage, TIMP2 was at its minimal level and returned to control levels 72 hours after damage (Fig. 7A,B). To further analyze TIMP2 in the IPL, we characterized immunolabeling above threshold to identify TIMP2+ neurites (Fig. 7C,D). The TIMP2-immunoreactivity was greatest near the borders of the INL and the GCL in undamaged retinas (Fig. 7E). In damaged retinas, early changes included the expansion of IPL and the loss of the proximal GCL border TIMP2+ neurites. Edemic swelling of the of IPL following treatment of the retina with excitotoxins has been well characterized (Fischer et al., 1998). By 24 hours, TIMP2-immunoreactivity was limited to the INL/IPL border. TIMP2-immunoreactivity re-appeared in the IPL by 48 hours after damage but did not regain the distribution seen in control retinas by 72 hours.

Figure 7.

TIMP2 is redistributed in the IPL after damage and inhibits MGPC formation. Retinas injected with NMDA are sectioned hours to days after damage (A). Retinal sections are stained with TIMP2 with example images of each time point (n = 4). The intensity of staining was quantified by densitometry and represented as a relative change to saline injected retinas (B). The change in TIMP2 distribution in the IPL is further quantified from hours to days following NMDA damage using DRAQ5 (red) and TIMP2 (green) immunolabeling (C). To track changes specific to TIMP2+ processes in the IPL, a threshold filter removed any TIMP2 staining non-specific to neuronal processes. The average area of TIMP2+ IPL processes is quantified from the inner INL border to the outer GCL border. The average area occupied by TIMP2+ processes was calculated for each pixel (1 pixel = 0.29µm) in the IPL (D, E). Exogenous TIMP2 was injected intravitreally after NMDA damage to maintain elevated TIMP2 levels and measure changes in MGPC formation (F). The addition of TIMP2 inhibited the formation of MGPCs as measured by Sox2+ Edu+ nuclei (n = 12). Error bars are ± 1 SD. Scale bar = 50µm Abbreviations: ONL – outer nuclear layer, INL – inner nuclear layer, IPL – inner plexiform layer, GCL – ganglion cell layer.

The decrease in IPL TIMP2 correlates with the decrease in IPL gelatinase activity (Fig 2F), leading to the hypothesis that TIMP2 may be an enzymatic activator of MMP-2. Therefore, we predicted that exogenous addition of TIMP2 may dampen the regenerative response of MG following NMDA damage. Indeed, intravitreal TIMP2 statistically reduced the formation of MGPCs 3 days after NMDA damage, measured by the decrease in Sox2+ Edu+ per retinal field (Fig. 7 F,G).

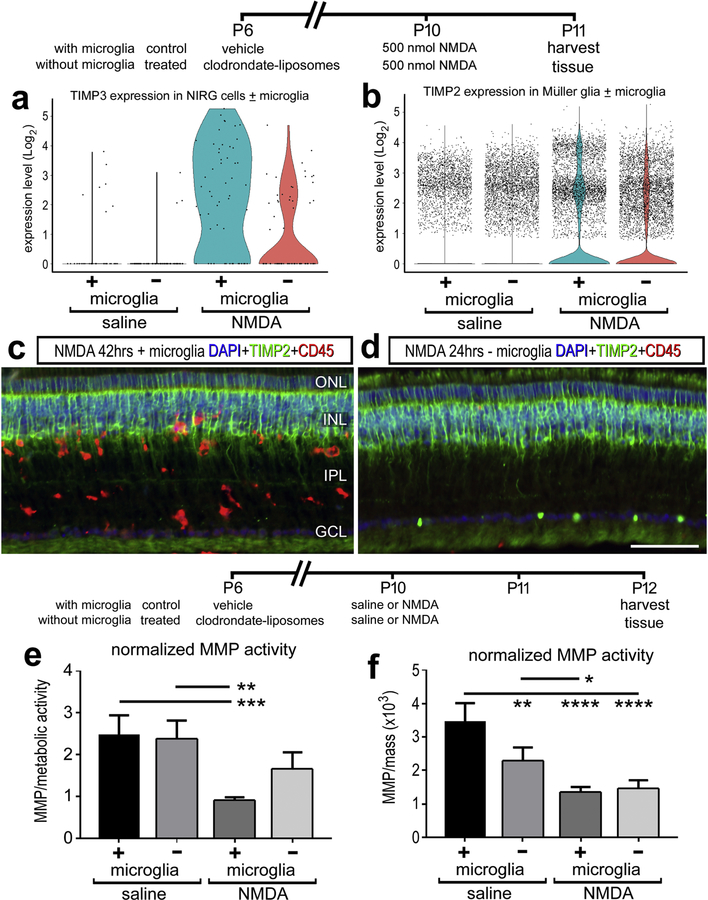

Microglia influence retinal TIMP2 and TIMP3 after NMDA damage

Microglia can influence the neuroinflammatory microenvironment of the retina and these glial cells are activated in response to NMDA damage. To determine whether microglia regulate gelatinase activity in retinal tissue, we compared retinal responses to NMDA damage after microglial ablation. The ablation of microglia was accomplished by delivery of clodronate liposomes, which results in >99% microglial death (Fischer et al., 2014). Single cell sequencing indicated an increase in TIMP3 with NIRG cells maximally at 24hrs after damage, and when this experiment is repeated without retinal microglia, the production of TIMP3 is dampened (Figure 8A). However, TIMP2 protein distribution or mRNA production by MG were not affected by the absence of microglia 24 hrs after damage (Fig 8C, D).

Figure 8.

Microglia inhibit gelatinase activity after NMDA damage and promote the mRNA production of TIMP3 from NIRG cells. Microglia were ablated with clodronate liposomes and observed 24hrs after NMDA damage. Single cell sequencing detected a decrease in TIMP3 in NIRG cells in damaged retinas lacking microglia (A). TIMP2 protein distribution changes or mRNA levels in MG were unaffected by the loss of retinal microglia (n = 3) (B, C, D). Changes in gelatinase activity was measured with retinal tissue in vitro quantifications. Activity was normalized to metabolic activity (E) and mass (F). (n = 4) for all experiments. The gelatinase activity of samples standardized for mass (B, F) were then normalized to the gelatinase activity a fixed concentration of collagenase. Error bars ± 1 SD, with significance of difference determined by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s post-test. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

The in vitro gelatinase enzymatic activity was also compared to NMDA-damaged retinas with or without microglia. When comparing the change in gelatinase activity, NMDA induced a reproducible decrease in gelatinase activity when microglia were present (Fig 8E, F). When microglia were ablated, NMDA did not induce a significant decrease the gelatinase activity (Fig 8E, F). When standardizing the activity to the mass of the retinal tissue, there was a significant decrease in gelatinase activity observed with microglial ablation alone (Fig 8F). When normalized to metabolic activity, the reduction in reactive microglia are presumed to cause an average decrease in metabolic activity, potentially overestimating the standardized value and masking the pro-gelatinase role of microglia in the undamaged retina.

Discussion

This study focused on characterizing gelatinase activity in retinal tissue in vitro and in situ, and the ability to modulate enzymatic activity to influence MGPC formation. Specifically, MMP2 was produced by oligodendrocytes and NIRG cells, a secretive process potentially regulated by microglia in the retina. Gelatinase activity decreased in the natural response to NMDA damage, and when MMP2 was inhibited through two different small molecule drugs, MGPC formation can be potentiated. In trying to understand the factors modulating gelatinase activity and its influence on MG reprogramming, we suggest that TIMP2 and TIMP3 dynamics are changing in response to NMDA damage to influence the reprogramming microenvironment and potentiate MGPC formation.

Retinal gelatinases and enzymatic activity

Gelatinase activity was characterized in the avian retina by detecting and quantifying active enzymatic activity. Due to the multivariate levels of regulation involved in balancing the enzyme kinetics in vivo, an analysis of MMP2 and MMP-9 enzymatic activity is the best measure to determine their role in physiologic homeostatic function. Cleavage of a fluorescein quenching peptide polymerized into a tissue stabilizing hydrogel can be used quantitatively to infer both temporal and spatial changes in MMP activity (Leight et al., 2013; Shin et al., 2018).

We report that retinal tissue expresses predominantly MMP2, not MMP-9, and that the origins of synthesis are in oligodendrocytes and NIRG cells. In the CNS, a commonly believed source of gelatinases are microglia, which have been demonstrated to secrete MMPs in other animals in the context of neuroinflammation and injury (Nuttall et al., 2007; Rosenberg, 2002; Yamada et al., 1995). Our scRNA-seq analysis of microglia does not show gelatinase transcription with or without damage. While the absence of detectable transcripts may be a biproduct of limited microglia extraction, or below detection thresholds as a low copy transcript, our data suggests that microglia play a role in maintaining gelatinase levels as enzyme activity decreases after damage. Hence, retinal microglia may play an indirect role through paracrine signaling to other glia or secreting other non-gelatinase factors.

Each layer in the retina was found to have a varying degree of gelatinase activity, and the stratified pattern suggests complex gelatinase regulation. Interestingly, the INL had an intermediate gelatinase activity that was detected on a gradient, with lower gelatinase activity in the outer INL (sclerad surface) and a higher level in the inner INL (vitread surface). The highest activity was seen paracellularly surrounding DAPI nuclei, suggesting that cell surface proteases modulate their localized activity. MMP2 can be bound and localized to the cell surface by integrin αvβ3 (found on MG, data not shown), and further activated by membrane type (MT) MMPs (Brooks et al., 1996; Emmert-Buck et al., 1995; Llano et al., 1999; Zhao et al., 2004). For example, our scRNA-seq data indicate MMP24 expression in amacrine cells, which may explain why the vitread half of the INL has more gelatinase activity than the sclerad half of the INL. After damage, pseudotime plots indicate there was a declining trend of cell surface MMPs 16 and 24 as MG made the transition into progenitor cells. While this did not appear to affect the total INL gelatinase activity, this may affect the ECM microenvironment of MGPCs and subsequent autocrine and paracrine signaling.

The pattern of gelatinase activity likely represents an aggregate of multiple sources of gelatinases found in proximity of the tissue such as the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE). In chick MMP2 expression has previously been detected in the RPE and in the photoreceptor layer (Takeyama et al., 2010). Although our scRNA-seq data do not support the notion that photoreceptors contribute gelatinases, secretion by the RPE, or perhaps Müller glia, would explain the origins of high enzymatic activity within the PRL, OPL, and ONL. Gelatinases near the vitread surface of the retina may originate from resident macrophages and monocytes present in the vitreous chamber of the eye. These cell types have been demonstrated to express gelatinases, with supporting evidence of MMP secretion by HB11 avian macrophage cell line, and zymography confirming the presence of MMP2 in the avian vitreous humor (Takeyama et al., 2010; Webster and Crowe, 2006; Zhou et al., 2014). It is no surprise then that the NFL has elevated levels of gelatinase activity with potential sources of MMP2 originating from oligodendrocytes and vitreous humor macrophages.

Reduction of gelatinase activity in response to NMDA damage

In vitro experiments of extracted retinas indicated that there is a consistent and reproducible decrease in gelatinase activity after NMDA damage. This decrease in activity was sustained for several days after the initial insult, but returned to normal levels after seven days. This result was consistent with metabolic and mass normalization methods, reducing the possibility that differences were a result of damage-induced metabolic changes. These results were contrary to initial expectations due to the correlation of elevated MMP2 during ECM remodeling and damage repair (Fawcett and Asher, 1999). We conducted follow-up experiments to understand the origins of this effect, and determine whether the effect may be related to a regenerative ECM microenvironment.

By using in situ gelatinase activity assays, we initially quantified no change in total activity across retinas treated with saline or NMDA. However, measurements of gelatinase activity within retinal layers revealed changes. Increases of gelatinase activity within the IPL correlated with decreases in TIMP2 distribution after NMDA damage. The scRNA-seq data indicate an increase in expression of TIMP2 from Müller glia, suggesting that Müller glia may underlie reduced in gelatinase activity in the IPL by providing inhibitor, TIMP2.

Alternatively, microglia in damaged retinas may mediate decreases in gelatinase activity. Microglia are commonly the mediator of neuroinflammation, and gelatinases such as MMP2 can activate pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β (Könnecke and Bechmann, 2013). Furthermore, microglia and inflammatory cytokines have been implicated as important mediators of neurogenesis in development as well as regeneration in the retina (Aguzzi et al., 2013; Fischer et al., 2014; Sato, 2015). Therefore, we compared changes in gelatinase activity in microglia ablated retinas before and after NMDA damage. When comparing gelatinase activity after microglial ablation in the absence of NMDA damage, there is a notable decrease in enzyme activity. This suggests that microglia are playing a role in regulating gelatinases in the retina under homeostatic conditions, and that ablation reduces their global retinal activity. It should be noted that the standardization method impacted this analysis, as changes in gelatinase activity was not observed when microglia was ablated and standardized to metabolic activity. We interpret this difference to be due to microglial cell death reducing the average metabolic activity, which overestimates the gelatinase activity for a retinal tissue segment.

Then, we looked at the role of microglia influence on gelatinase activity with NMDA damage. Without affecting microglia, NMDA damage causes a significant decrease in gelatinase activity. When repeating the damage paradigm after microglia have been ablated, NMDA damage does not replicate this inhibitory effect on gelatinase activity. This implies that microglia are in part, directly or indirectly, involved in the down regulation of gelatinase activity after damage. Potential direct mechanisms include the secretion of MMPs, their proteolytic activators, or their associated inhibitors. Alternatively, an indirect mechanism to influence gelatinase activity would be the secretion of cytokines binding to cytokine receptors found on glia or neurons to induce gelatinases or their modulators. The scRNA seq suggested that microglia play a role in upregulating the production of TIMP3 in NIRGs after NMDA damage.

In the context of retinal damage and regeneration, findings indicate that an initiating inflammatory signal is required to initiate the process of reprogramming MG into MGPCs in zebrafish (Nelson et al., 2013) and chick models (Fischer et al., 2014). By contrast, sustained pro-inflammatory signaling may suppress the reprogramming of Müller glia and favor a gliotic, activated phenotype (Sifuentes et al., 2016; Widera et al., 2008). Tight coordination of these inflammatory signals may prove crucial for initial reprogramming and maintaining regeneration competency in the retina.

MMP2 enzymatic flux influence on MG reprogramming

When measuring global gelatinase activity with in vitro techniques of retinal tissue, there is a sustained decrease for several days after NMDA damage. This decrease appears to start several hours after NMDA damage and remains depressed for days. After 72 hrs the activity returns to normal and the GCL layer appears to increase in gelatinase activity according to in situ comparisons—further implicating oligodendrocytes as an origin of MMP2 secretion. When the gelatinase reduction is facilitated with different MMP2 inhibitors, we observe an increase in Edu+ MGPCs. This result suggests that reducing gelatinase activity supports a regenerative microenvironment for de-differentiation into MGPCs.

In zebrafish, increasing MMP activity has been shown to increase proliferation in response to damage. Pan-MMP inhibitor GM6001 reduced proliferation, which was overcome by the administration of epidermal growth factor (EGF), suggesting that the EGF/EGFR pathway was dependent of MMP activity for reprogramming (Wan et al., 2012). The expression of MMP-9 increased the expression of transcription factor ASCL1a (Achaete-scute homolog 1) as determined through ASCLA1a luciferase assays and morpholino treatments (Kaur et al., 2018). These results indicate that MMP2 and MMP-9 may have different biological functions, or that the role of gelatinases in regeneration is variable among species.

In mammals, many paradigms of damage are associated with corresponding microglia activation and MMP secretion (Rosenberg, 2002). In these model species, there is limited regenerative responses to damage, and the predominant response is to generate a glial scar (Fawcett and Asher, 1999). Within the CNS, there is an upregulation of scarring factors from glia such as tenascin, brevican, neurocan, NG2, TGFβ, and others (Fawcett and Asher, 1999; Penn et al., 2012). TGFβ is secreted into the ECM as a tripartite complex that permits the cytokine to remain latent and inactive until matrix degradation frees the protein for binding to the TGFβ receptor (Horiguchi et al., 2012). Previously, our lab and others have demonstrated that intraocular injection of TGFβ reduce MGPC proliferation through Smad 2/3 signaling (Close et al., 2006; Todd et al., 2017). Given the complex relationship of TGFβ with the ECM, the potential of this signaling cascade to be modulated by gelatinase activity present. Thus, we hypothesize that TGFβ may be one of the factors affected by reduced gelatinase activity to promote a regenerative response.

Dynamic changes of TIMP2 localization with NMDA damage

TIMP2 is a glycoprotein that is an endogenous inhibitor of MMPs, with increased specificity toward MMP2 (Nagase et al., 2006). Provided that MMP2 is the predominant gelatinase in the retina, and its activity decreases in response to NMDA damage, TIMP2 is a logical target to mediate this response. However, the relationship between MMP2 and TIMP2 is complicated by its noncanonical functions. TIMP2 can complex with MMP14 on the cell surface and activate pro-MMP2 (Emmert-Buck et al., 1995; Zucker et al., 1998). Some research suggests that TIMP2-MMP2 complex is the most efficient means of MMP2 activation in vivo (Wang et al., 2000). Furthermore, TIMP2 has been implicated in cytoplasmic functions independent of its effect on MMP2. In PC12 cells, increased TIMP2 increased p21cip, decreased expression of cyclin B and D, and promoted neuronal differentiation through a cAMP/Rap1/ERK (Pérez-Martínez and Jaworski, 2005).

Our data suggests that TIMP2 is expressed predominantly by MG, but protein localization is found at higher concentration on the processes of bipolar cells. With NMDA damage, there is a dramatic decrease in TIMP2 only hours later in the IPL. Drastic changes in TIMP2 IPL localization imposed the question whether these changes were due to cell death, or dynamic trafficking and degradation of TIMP2. Previous data characterizing NMDA excitotoxicity on avian retina suggest that only a small fraction of bipolar cells die (Fischer et al., 1998). With this data in mind, our current hypothesis is that TIMP2 is being trafficked and localized differently in response to damage. However, PKCα did not remain a reliable marker of bipolar cell processes several days after damage, hence we cannot confidently conclude whether there was also robust remodeling of bipolar cell processes that coincide with TIMP2 changes.

In response, MG appear to upregulate TIMP2 expression and results in the partial restoration of the physiologic staining after 72 hours. The concurrent decrease in TIMP2 and decrease in MMP2 activity in the IPL occur during similar timeframes, leading to the hypothesis that TIMP2 may be playing a more significant role in MMP2 activation than inhibition in this context. Exogenous addition of TIMP2 after NMDA damage inhibits gelatinase activity, demonstrating behavior opposite of MMP2 inhibitors. Cell surface MMPs were detected on bipolar cells in the single cell sequencing data, suggesting the possibility that TIMP2 is complexed on the cell surface that serves as a cofactor in the proteolytic activation of gelatinases. The relatively low activity of gelatinases in the IPL may be due to other inhibitors, such as TIMP3 produced by NIRG cells also present in the IPL. Further investigation on the potential role of TIMP2 production by MG and localization on rod bipolar cells are required to understand the mechanism of gelatinase regulation after NMDA damage due to the diverse functions of TIMP2.

Conclusions

Gelatinases are known to play important roles regulating the ECM, including the development and physiologic function of retinal tissue. By using a combination of in situ zymography and in vitro tissue encapsulation techniques we quantified gelatinase activity after NMDA damage during MG reprogramming in the avian retina. Global retinal gelatinase activity significantly decreased after damage during the early reprogramming phase of MG with in vitro experiments. In situ experiments indicated significant decreases in IPL gelatinase activity which correlated with changes in TIMP2 and TIMP3 expression. Microglia were found to regulate MMP activity after damage, such as an mediating an increase in TIMP3 mRNA in NIRG cells. Inhibition of gelatinase activity in retinas prior to an insult or growth factor treatment enhanced the formation of proliferating MGPCs. Inhibitors with specificity for MMP2, but not MMP-9, suppressed the formation of MGPCs. These findings are consistent with scRNA-seq transcriptomic data indicating that glial MMP2 is the primary gelatinase of the retina. These results emphasize the importance of gelatinase-mediated remodeling of ECM in cellular reprogramming, and may implicate different ECM-dependent growth factors that can impact MG and their regenerative potential.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

MMP2 is the primary gelatinase in the avian retina.

Retinal damage decreased gelatinase activity during Müller glia reprogramming

Inhibition of MMP2 enhanced the formation of progenitor cells after damage

TIMP2 is synthesized by Müller glia and colocalizes with rod bipolar cells

Microglia mediate the decrease in gelatinase activity after damage

Acknowledgements:

Research was supported by the following grants: RO1 EY022030-6 to AJF, UO1EY027267-02 to SB and AJF from the National Eye Institute.

This work was supported by RO1 EY022030-06 (AJF) and UO1 EY027267-02 (SB, AJF).

Abbreviations:

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- MMP

matrix-metalloproteinase

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of matrix-metalloproteinase

- MG

Müller glia

- MGPC

Müller glia derived progenitor cell

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- scRNA-seq

single cell RNA sequencing

- tSNE

t-stochastic neighbor embedding

- Edu

5-ethynyl 2’-deoxyuridine

- NFL

nerve fiber layer

- GCL

ganglion cell layer

- IPL

inner plexiform layer

- INL

inner nuclear layer

- OPL

outer plexiform layer

- ONL

outer nuclear layer

- PRL

photoreceptor layer

- RPE

retinal pigmented epithelium

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declarations of interest: none

References:

- Aguzzi A, Barres BA, and Bennett ML (2013). Microglia: Scapegoat, Saboteur, or Something Else? Science 339, 156–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann A, Pannicke T, Grosche J, Francke M, Wiedemann P, Skatchkov SN, Osborne NN, and Reichenbach A (2006). Müller cells in the healthy and diseased retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res 25, 397–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks PC, Strömblad S, Sanders LC, von Schalscha TL, Aimes RT, Stetler-Stevenson WG, Quigley JP, and Cheresh DA (1996). Localization of Matrix Metalloproteinase MMP-2 to the Surface of Invasive Cells by Interaction with Integrin αvβ3. Cell 85, 683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler A, Hoffman P, Smibert P, Papalexi E, and Satija R (2018). Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler GS, Butler MJ, Atkinson SJ, Will H, Tamura T, Westrum S.S. van, Crabbe T, Clements J, d’Ortho M-P, and Murphy G (1998). The TIMP2 Membrane Type 1 Metalloproteinase “Receptor” Regulates the Concentration and Efficient Activation of Progelatinase A A KINETIC STUDY. J. Biol. Chem 273, 871–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cawston TE, Murphy G, Mercer E, Galloway WA, Hazleman BL, and Reynolds JJ (1983). The interaction of purified rabbit bone collagenase with purified rabbit bone metalloproteinase inhibitor. Biochem. J 211, 313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti S, Mandal M, Das S, Mandal A, and Chakraborti T (2003). Regulation of matrix metalloproteinases: an overview. Mol. Cell. Biochem 253, 269–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen DRG, Brown FE, Cree AJ, Ratnayaka JA, and Lotery AJ (2017). Sorsby fundus dystrophy – A review of pathology and disease mechanisms. Exp. Eye Res 165, 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Close JL, Liu J, Gumuscu B, and Reh TA (2006). Epidermal growth factor receptor expression regulates proliferation in the postnatal rat retina. Glia 54, 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert-Buck MR, Emonard H, Corcoran ML, Krutzsch HC, Foidart J-M, and Stetler-Stevenson WG (1995). Cell surface binding of TIMP-2 and pro-MMP-2/TIMP-2 complex. FEBS Lett 364, 28–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairbanks BD, Schwartz MP, Halevi AE, Nuttelman CR, Bowman CN, and Anseth KS (2009). A Versatile Synthetic Extracellular Matrix Mimic via Thiol-Norbornene Photopolymerization. Adv. Mater. Deerfield Beach Fla 21, 5005–5010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JW, and Asher RA (1999). The glial scar and central nervous system repair. Brain Res. Bull 49, 377–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ (2005). Neural regeneration in the chick retina. Prog. Retin. Eye Res 24, 161–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, and Bongini R (2010). Turning Müller Glia into Neural Progenitors in the Retina. Mol. Neurobiol 42, 199–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, and Reh TA (2001). Müller glia are a potential source of neural regeneration in the postnatal chicken retina. Nat. Neurosci 4, 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Seltner RLP, Poon J, and Stell WK (1998). Immunocytochemical characterization of quisqualic acid- and N-methyl-D-aspartate-induced excitotoxicity in the retina of chicks. J. Comp. Neurol 393, 1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, McGuire CR, Dierks BD, and Reh TA (2002). Insulin and Fibroblast Growth Factor 2 Activate a Neurogenic Program in Müller Glia of the Chicken Retina. J. Neurosci 22, 9387–9398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Foster S, Scott MA, and Sherwood P (2008). The transient expression of LIM-domain transcription factors is coincident with the delayed maturation of photoreceptors in the chicken retina. J. Comp. Neurol 506, 584–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Scott MA, Ritchey ER, and Sherwood P (2009). Mitogen-activated protein kinase-signaling regulates the ability of Müller glia to proliferate and protect retinal neurons against excitotoxicity. Glia 57, 1538–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer AJ, Zelinka C, Gallina D, Scott MA, and Todd L (2014). Reactive microglia and macrophage facilitate the formation of Müller glia-derived retinal progenitors. Glia 62, 1608–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch JM, Kidder JM, and Linsenmayer TF (2005). Cellular invasion of the chicken corneal stroma during development: Regulation by multiple matrix metalloproteases and the lens. Dev. Dyn 232, 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallina D, Todd L, and Fischer AJ (2014). A comparative analysis of Müller glia-mediated regeneration in the vertebrate retina. Exp. Eye Res 123, 121–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallina D, Zelinka CP, Cebulla C, and Fischer AJ (2015). Activation of glucocorticoid receptors in Müller glia is protective to retinal neurons and suppresses microglial reactivity. Exp. Neurol 273, 114–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman D (2014). Müller glial cell reprogramming and retina regeneration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 15, 431–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehr CL, Hocking JC, and McFarlane S (2005). Matrix metalloproteinases are required for retinal ganglion cell axon guidance at select decision points. Development 132, 3371–3379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiguchi M, Ota M, and Rifkin DB (2012). Matrix control of transforming growth factor-β function. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 152, 321–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard EW, Bullen EC, and Banda MJ (1991). Preferential inhibition of 72- and 92-kDa gelatinases by tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2. J. Biol. Chem 266, 13070–13075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihanamäki T, Pelliniemi LJ, and Vuorio E (2004). Collagens and collagen-related matrix components in the human and mouse eye. Prog. Retin. Eye Res 23, 403–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh Y, Ito A, Iwata K, Tanzawa K, Mori Y, and Nagase H (1998). Plasma Membrane-bound Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinases (TIMP)-2 Specifically Inhibits Matrix Metalloproteinase 2 (Gelatinase A) Activated on the Cell Surface. J. Biol. Chem 273, 24360–24367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer RP, Patterson NL, Fields GB, and Lindsey ML (2012). The history of matrix metalloproteinases: milestones, myths, and misperceptions. Am. J. Physiol. - Heart Circ. Physiol 303, H919–H930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karl MO, and Reh TA (2010). Regenerative medicine for retinal diseases: activating the endogenous repair mechanisms. Trends Mol. Med 16, 193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Gupta S, Chaudhary M, Khursheed MA, Mitra S, Kurup AJ, and Ramachandran R (2018). let-7 MicroRNA-Mediated Regulation of Shh Signaling and the Gene Regulatory Network Is Essential for Retina Regeneration. Cell Rep 23, 1409–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Könnecke H, and Bechmann I (2013). The Role of Microglia and Matrix Metalloproteinases Involvement in Neuroinflammation and Gliomas [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Leight JL, Alge DL, Maier AJ, and Anseth KS (2013). Direct measurement of matrix metalloproteinase activity in 3D cellular microenvironments using a fluorogenic peptide substrate. Biomaterials 34, 7344–7352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X (2004). Functions of heparan sulfate proteoglycans in cell signaling during development. Development 131, 6009–6021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llano E, Pendás AM, Freije JP, Nakano A, Knäuper V, Murphy G, and López-Otin C (1999). Identification and Characterization of Human MT5-MMP, a New Membrane-bound Activator of Progelatinase A Overexpressed in Brain Tumors. Cancer Res 59, 2570–2576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan P, Marshall J-CA, Fernandes BF, Bakalian S, Martins C, and Burnier MN, J. (2007). MMP-2 and MMP-9 Secretion by Human Uveal Melanoma Cell Lines in Response to Different Growth Factors and Chemokines. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 48, 4766–4766.17898303 [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad G, and Kowluru RA (2010). Matrix Metalloproteinase-2 in the Development of Diabetic Retinopathy and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Lab. Investig. J. Tech. Methods Pathol 90, 1365–1372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, and Woessner JF (1999). Matrix Metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem 274, 21491–21494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Visse R, and Murphy G (2006). Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc. Res 69, 562–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naitoh H, Suganuma Y, Ueda Y, Sato T, Hiramuki Y, Fujisawa-Sehara A, Taketani S, and Araki M (2017). Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase triggers transdifferentiation of retinal pigmented epithelial cells in Xenopus laevis: A Link between inflammatory response and regeneration. Dev. Neurobiol 77, 1086–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson CM, Ackerman KM, O’Hayer P, Bailey TJ, Gorsuch RA, and Hyde DR (2013). Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha Is Produced by Dying Retinal Neurons and Is Required for Müller Glia Proliferation during Zebrafish Retinal Regeneration. J. Neurosci 33, 6524–6539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuttall RK, Silva C, Hader W, Bar-Or A, Patel KD, Edwards DR, and Yong VW (2007). Metalloproteinases are enriched in microglia compared with leukocytes and they regulate cytokine levels in activated microglia. Glia 55, 516–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn JW, Grobbelaar AO, and Rolfe KJ (2012). The role of the TGF-β family in wound healing, burns and scarring: a review. Int. J. Burns Trauma 2, 18–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Martínez L, and Jaworski DM (2005). Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-2 promotes neuronal differentiation by acting as an anti-mitogenic signal. J. Neurosci. Off. J. Soc. Neurosci 25, 4917–4929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi JH, Ebrahem Q, Yeow K, Edwards DR, Fox PL, and Anand-Apte B (2002). Expression of Sorsby’s Fundus Dystrophy Mutations in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells Reduces Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibition and May Promote Angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem 277, 13394–13400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Mao Q, Tang Y, Wang L, Chawla R, Pliner HA, and Trapnell C (2017a). Reversed graph embedding resolves complex single-cell trajectories. Nat. Methods 14, 979–982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu X, Hill A, Packer J, Lin D, Ma Y-A, and Trapnell C (2017b). Single-cell mRNA quantification and differential analysis with Census. Nat. Methods 14, 309–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenbach A, and Bringmann A (2013). New functions of Müller cells. Glia 63, 651–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg GA (2002). Matrix metalloproteinases in neuroinflammation. Glia 39, 279–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahay P, Rao A, Padhy D, Sarangi S, Das G, Reddy MM, and Modak R (2017). Functional Activity of Matrix Metalloproteinases 2 and 9 in Tears of Patients With Glaucoma. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 58, BIO106–BIO113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K (2015). Effects of Microglia on Neurogenesis. Glia 63, 1394–1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DS, Tokuda EY, Leight JL, Miksch CE, Brown TE, and Anseth KS (2018). Synthesis of Microgel Sensors for Spatial and Temporal Monitoring of Protease Activity. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng 4, 378–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sifuentes CJ, Kim J-W, Swaroop A, and Raymond PA (2016). Rapid, Dynamic Activation of Müller Glial Stem Cell Responses in Zebrafish. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci 57, 5148–5160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeyama M, Yoneda M, Takeuchi M, Isogai Z, Ohno-Jinno A, Kataoka T, Li H, Sugita I, Iwaki M, and Zako M (2010). Increase in matrix metalloproteinase-2 level in the chicken retina after laser photocoagulation. Lasers Surg. Med 42, 433–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todd L, Palazzo I, Squires N, Mendonca N, and Fischer AJ (2017). BMP- and TGFβ-signaling regulate the formation of Müller glia-derived progenitor cells in the avian retina. Glia 65, 1640–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Cacchiarelli D, Grimsby J, Pokharel P, Li S, Morse M, Lennon NJ, Livak KJ, Mikkelsen TS, and Rinn JL (2014). The dynamics and regulators of cell fate decisions are revealed by pseudotemporal ordering of single cells. Nat. Biotechnol 32, 381–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Väisänen A, Kallioinen M, Dickhoff K. von, Laatikainen L, Höyhtyä M, and Turpeenniemi-Hujanen T (1999). Matrix metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) immunoreactive protein—a new prognostic marker in uveal melanoma? J. Pathol 188, 56–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rooijen N (1989). The liposome-mediated macrophage ‘suicide’ technique. J. Immunol. Methods 124, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J, and Goldman D (2016). Retina regeneration in zebrafish. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev 40, 41–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J, Ramachandran R, and Goldman D (2012). HB-EGF Is Necessary and Sufficient for Müller Glia Dedifferentiation and Retina Regeneration. Dev. Cell 22, 334–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Juttermann R, and Soloway PD (2000). TIMP-2 Is Required for Efficient Activation of proMMP-2 in Vivo. J. Biol. Chem 275, 26411–26415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster NL, and Crowe SM (2006). Matrix metalloproteinases, their production by monocytes and macrophages and their potential role in HIV-related diseases. J. Leukoc. Biol 80, 1052–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welgus HG, Jeffrey JJ, Eisen AZ, Roswit WT, and Stricklin GP (1985). Human skin fibroblast collagenase: interaction with substrate and inhibitor. Coll. Relat. Res 5, 167–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widera D, Kaus A, Kaltschmidt C, and Kaltschmidt B (2008). Neural stem cells, inflammation and NF-κB: basic principle of maintenance and repair or origin of brain tumours? J. Cell. Mol. Med 12, 459–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Yoshiyama Y, Sato H, Seiki M, Shinagawa A, and Takahashi M (1995). White matter microglia produce membrane-type matrix metalloprotease, an activator of gelatinase A, in human brain tissues. Acta Neuropathol. (Berl.) 90, 421–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelinka CP, Scott MA, Volkov L, and Fischer AJ (2012). The Reactivity, Distribution and Abundance of Non-Astrocytic Inner Retinal Glial (NIRG) Cells Are Regulated by Microglia, Acute Damage, and IGF1. PLOS ONE 7, e44477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Bai S, Zhang X, Nagase H, and Sarras MP (2003). The expression of gelatinase A (MMP-2) is required for normal development of zebrafish embryos. Dev. Genes Evol 213, 456–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Bernardo MM, Osenkowski P, Sohail A, Pei D, Nagase H, Kashiwagi M, Soloway PD, DeClerck YA, and Fridman R (2004). Differential Inhibition of Membrane Type 3 (MT3)-Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) and MT1-MMP by Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase (TIMP)-2 and TIMP-3 Regulates Pro-MMP-2 Activation. J. Biol. Chem 279, 8592–8601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou ZY, Packialakshmi B, Makkar SK, Dridi S, and Rath NC (2014). Effect of butyrate on immune response of a chicken macrophage cell line. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol 162, 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker S, Drews M, Conner C, Foda HD, DeClerck YA, Langley KE, Bahou WF, Docherty AJP, and Cao J (1998). Tissue Inhibitor of Metalloproteinase-2 (TIMP-2) Binds to the Catalytic Domain of the Cell Surface Receptor, Membrane Type 1-Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 (MT1-MMP). J. Biol. Chem 273, 1216–1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.