Abstract

Background:

The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of HBsAg in Health Care Workers (HCWs) in Eastern Mediterranean Region Office (EMRO) and Middle Eastern countries from 2000 to 2016.

Methods:

In a meta-analysis study, the databases of PubMed, ISI, Ovid, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Persian databases were searched for relevant articles on the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries. Homogeneity was assessed based on Cochran's Q-test results.

Results:

A total of 43 articles (110,179 people) were included. The pooled prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs of EMRO and Middle East countries was found 2.77% (95%CI: 2.64-2.83). The specific prevalence of HBsAg was 2.84% (95% CI: 2.6-3.11) in EMRO and 2.22% (95%CI: 2.13-2.31) in Middle Eastern countries. The highest and lowest prevalence rates of HBsAg among HCWs for countries with more than one study were 6.85% (95% CI: 5.74%–8.16%) in Sudan and 1.00% (95% CI: 0.94%–1.07%) in Turkey, respectively. The trends of HBsAg prevalence among HCWs decreased from 2000 to 2016.

Conclusions:

Based on the World Health Organization classification of HBV prevalence, intermediate HBsAg prevalence rates were detected in HCWs of EMRO and Middle East countries during 2000–2016.

Keywords: Eastern Mediterranean, health care workers, hepatitis B, meta-analysis, Middle East, prevalence

Introduction

The prevalence of personnel's exposure to Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) is related to the prevalence and endemicity of the disease in general population, as 90% of such infections occur in Asia and Africa.[1,2,3,4] Of the 35 million healthcare workers (HCWs) in the world, 3 million are annually exposed to blood-borne pathogens, including 2 million to HBV, 0.9 million to hepatitis C, and 170000 to HIV.[5]

Due to the availability of HBV vaccine, the incidence of the disease and HBV-related mortality has reduced. In 1982, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that all HCWs be vaccinated against HBV. Although acute and chronic cases of HBV infection are rare in vaccinated HCWs, those who fail to respond positively to the vaccine continue to be susceptible to infection.[6,7,8] According to CDC, vaccination of HCWs has reduced the incidence of new HBV cases in the United States by five-fold from 2,08,000 in 1980 to 38,000 in 2010.[9]

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the prevalence of HBV in the Eastern Mediterranean Regional Office (EMRO) 4.3 million, indicating its high prevalence in this region.[10] WHO categorizes the prevalence of HBV as low (<2%), medium (2% to 8%), and high (>8%).[11] The prevalence of HBV in EMRO and many Middle Eastern countries in different age groups has been reported low-medium, and high in some cases.[12,13] Many studies have investigated the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and the Middle East, and have found a different pattern for the prevalence of this disease. In a study conducted in Sudan, the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs was reported 16%.[14] The spread of HBV in HCWs in these regions is such that the prevalence of HBsAg has been reported 4.7% in Pakistan,[15] 1% in Morocco,[16] and 0.2% in Iran.[17] Understanding the prevalence of some infections such as HBsAg may provide useful information for health policymakers to consider the best preventive measures for HCWs in different societies.

Available review studies on HBsAg prevalence in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries have focused on blood donors, pregnant women and children.[18,19,20] In addition, single studies conducted so far on the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries have shown different prevalence rates in different areas. As there is no comprehensive study on the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs of EMRO and Middle Eastern countries in different years, especially after the initiation of the vaccination program in 1992 in these regions[21], a meta-analysis and review study therefore appears beneficial. Hence, the present study was conducted to determine the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries from 2000 to 2016.

Methods

Sources of data

In the present study, a search was conducted in titles and/or abstracts of articles published from January 1st 2000 to December 31st 2016, in the following databases: Pubmed, ISI, Science Direct, Ovid, Scopus, and Google Scholar. At this stage, the number of articles found in each database, and then the final numbers of articles were recorded. The year 2000 was used because it was some years after the beginning of vaccination program in 1992 that the efficiency of Hepatitis B vaccine may be more likely observed. The search was conducted using different combinations of words sought by researchers and also Mesh words as follows: “epidemiology,” “prevalence,” “HBV,” “hepatitis b virus,” “HBsAg,” and “Healthcare workers,” along with the names of the E and M countries, including: Afghanistan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Djibouti, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Oman, Pakistan, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

Moreover, using the above keywords in English and Farsi, Iranian databases including Scientific Information Database, Iran Medex, Magiran, and Medlib, Pakistan's comprehensive database (PakMediNet), and WHO EMRO journal and Hepatitis Monthly journal were also used for the search. Sensitivity of search was assessed through review of repeated articles. If the full text of an article was not found, it was requested from the corresponding author through an email, and if no response was received from the corresponding author, the abstract of the article was used. Articles lacking the desired information were excluded.

Selection of articles

Full texts of English or Farsi articles were included if they were cross-sectional and contained specific information about the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries. Studies conducted on the general population were also included if they contained HCWs as a subgroup. Exclusion criteria affected the following studies: 1) All studies except for cross-sectional studies; 2) Not reporting the prevalence of HBsAg clearly and reporting the general prevalence of HBV (given the present study objective, which was an assessment of only HBsAg prevalence in HCWs); 3) reporting vague data and results. Author's name or journal had no effect on the choice of articles. The prevalence of HBsAg in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries is reported separately for member countries in Table 1.

Table 1.

The description of studies in EMRO and Middle East countries that met our eligibility criteria

| Countries | Authors’ names | Pub. year | Samples size | HBsAg Positive (No) | HBsAg Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iran (E & M) | Asefzade, M | 2004 | 270 | 3 | 1.1 |

| Azarhoosh, R | 2006 | 300 | 3 | 1 | |

| Bayani, M | 2014 | 527 | 4 | 0.75 | |

| Binesh, F | 2015 | 431 | 1 | 0.23 | |

| Salmanzadeh, SH | 2016 | 188 | 4 | 2.1 | |

| Kamangar, E | 2003 | 285 | 3 | 1.05 | |

| Salari, M | 2006 | 406 | 5 | 1.23 | |

| Amini-Ranjbar, S | 2008 | 83 | 8 | 9.6 | |

| Ghorbani, Gh | 2010 | 112 | 3 | 2.6 | |

| Alavian, S.M | 2008 | 83 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sharifi, M | 2008 | 77 | 0 | 0 | |

| Baba Mahmoodi, F | 2000 | 183 | 3 | 1.6 | |

| Khosravani, A | 2012 | 222 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mokhayeri, H | 2016 | 462 | 7 | 1.52 | |

| Torkzaban, P | 2009 | 123 | 4 | 3.5 | |

| Yarmohammadi, M | 2010 | 191 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ranjbar, M | 2001 | 130 | 1 | 0.77 | |

| Iraq (E & M) | Al-Mashhadani, J. I | 2009 | 1656 | 89 | 5.37 |

| Hussein, N. R | 2015 | 192 | 1 | 0.52 | |

| Hamied, L | 2010 | 375 | 25 | 6.66 | |

| Libya (E & M) | Elzouki, A. N | 2014 | 601 | 11 | 1.83 |

| Ziglam, H | 2013 | 2705 | 31 | 1.1 | |

| Morocco (E) | Djeriri, K | 2008 | 276 | 3 | 1 |

| Souly, K | 2016 | 601 | 19 | 3.16 | |

| Pakistan (E) | Abdul Qayyum, F | 2012 | 1891 | 27 | 1.4 |

| Aziz, S | 2002 | 250 | 6 | 2.4 | |

| Memon, M. S | 2007 | 380 | 18 | 4.7 | |

| Saqib, Sh | 2016 | 500 | 3 | 0.6 | |

| Palestine (E & M) | Astal, Z | 2004 | 399 | 11 | 2.75 |

| Sudan (E) | Elduma, A. H | 2011 | 245 | 12 | 4.9 |

| Elmukashfi, T. A | 2012 | 843 | 51 | 6.04 | |

| Elmukashfi, T. A | 2016 | 385 | 62 | 16.1 | |

| Nail, A | 2008 | 211 | 5 | 2.4 | |

| Saudi Arabia (E & M) | Alqahtani, J. M | 2014 | 300 | 1 | 0.33 |

| Turkey (M) | Fatma, E. T | 2015 | 91185 | 2462 | 2.7 |

| Ozsoy, M. F | 2003 | 702 | 21 | 3 | |

| Bosnak, V. K | 2013 | 199 | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Guven, R | 2006 | 571 | 2 | 0.35 | |

| Erden, S | 2003 | 109 | 7 | 6.4 | |

| Irmak, Z | 2010 | 147 | 1 | 0.68 | |

| Kosgeroglu, N | 2004 | 595 | 16 | 2.68 | |

| Tozun, N | 2015 | 245 | 3 | 1.23 | |

| Yemen (E & M) | Shidrawi, R | 2004 | 543 | 54 | 9.9 |

| Pooled Estimate* | - | - | 110179 | 2991 | 2.77 (2.64-2.83)≤ |

*Pooled estimate by random-effects Meta analyses≤95% confidence interval (in brackets); (E: EMRO countries; M: Middle East countries; E & M: All countries from two regions)

Data extraction

The quality of articles was assessed by 2 authors. The first author (M.B) conducted the process of data extraction to find eligible studies. The second author (S.M.A) (not involved in the search process) carefully assessed the quality of articles. Next, the present study authors held a meeting to discuss relevant questions before critical assessment of articles. Blinding and assigning tasks were carried out during the selection of articles. Following the final assessment, selected articles and required data, namely first author's name, publication year, country's name, sample size, the percentage of participating men, and prevalence of HBsAg, and Standard Error (SE) were recorded and entered into Excel. SE was found using Cochran test. Duplicated findings were removed using EndNote X6 software (Thomas Reuters, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Statistical analysis

Homogeneity was assessed based on Cochran's Q-test results. However, since this test may fail to exactly identify true homogeneity, it was complemented with Higgins and Thompson's I2. “metaprop” command was then used to apply a random effects model based on the significance of the Cochran's test and a large I2 value. By using metaprop, no studies with 0% or 100% proportions were excluded from the meta-analysis. Furthermore, study specific and pooled confidence intervals always were within admissible values and avoid confidence intervals exceeding the 0 to 1 range.[22] Data aggregation and production of the pooled estimates were performed using the above-mentioned methods. Forest plots with descriptions of the findings were then developed to describe the results and calculate the point estimations and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Publication bias was assessed through the funnel plot. Funnel plot asymmetry was further tested using Begg and Egger's methods. Stata 11.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX, USA) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

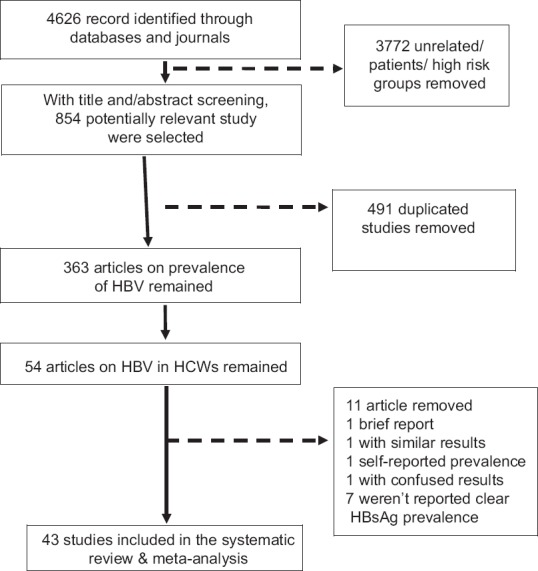

Initially, using titles and/or abstracts, a total of 4626 articles were found, of which, 854 articles potentially related to the study objectives were selected. Next, 491 repeated articles were excluded and 363 articles relating to the prevalence of HBV in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries remained. Taking into account the study objectives, 54 articles that reported the prevalence of HBV in HCWs were chosen. Given the importance of quality of articles, 11 articles that lacked inclusion criteria were excluded. A short report article,[23] one article for reporting the results in 2 separate journals,[24] and another for using self-reporting style for the prevalence of HBsAg[25] were also excluded. In one of the excluded articles, the prevalence was reported 3.3%, found by dividing number of HBsAg positive (3 people) into total number of personnel (110 people), whereas the prevalence should have been reported 2.72%, therefore it was excluded due to vague results.[26] A further 7 articles were excluded for failing to report HBsAg in HCWs clearly, and citing the prevalence of HBV.[27,28,29,30,31,32,33] Eventually, 43 articles that clearly reported the prevalence of HBsAg remained for analysis [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Follow diagram of systematic review and meta-analysis of HBsAg prevalence in health care workers of EMRO and Middle East regions

Features of articles

A total of 43 articles were found from member countries of EMRO and Middle East that reported the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs, and included a sample of 110179 people. Of these articles, 17 had been conducted in Iran,[17,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] 3 in Iraq,[50,51,52] 2 in Libya,[53,54] 2 in Morocco,[16,55] 4 in Pakistan,[15,56,57,58] 1 in Palestine,[59] 1 in Saudi Arabia,[60] 4 in Sudan,[14,61,62,63] 8 in Turkey,[64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71] and 1 in Yemen.[72]

General prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries

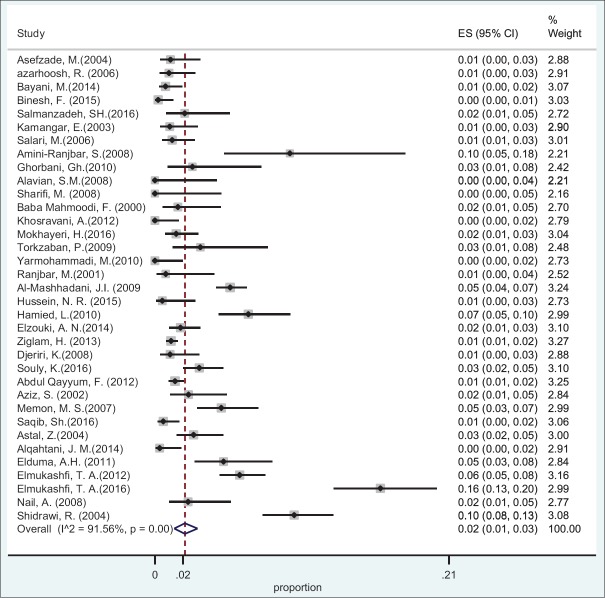

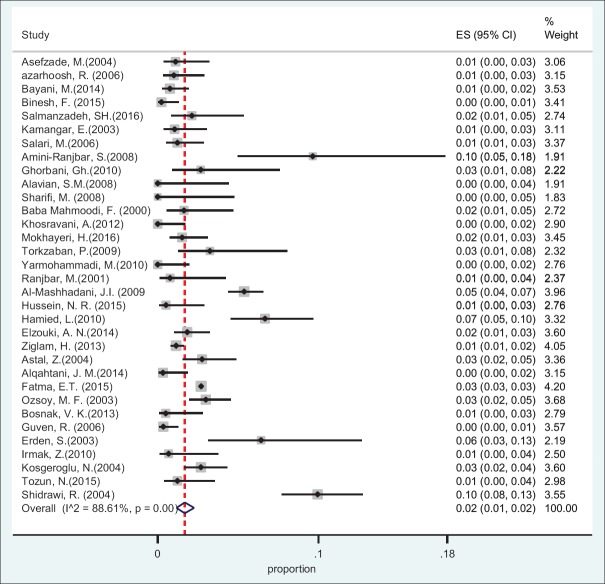

Based on the data obtained from 10 countries and using random effect model, the pooled prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs was found 2.77% (95%CI: 2.64-2.83) [Table 1]. The specific prevalence of this index was found 2.84% (95%CI: 2.6-3.11) in Eastern Mediterranean countries and 2.22% (95%CI: 2.13-2.31) in Middle Eastern countries [Figures 2 and 3].

Figure 2.

Forest plot of HBsAg prevalence in health care workers from Eastern Mediterranean countries

Figure 3.

Forest plot of HBsAg prevalence in health care workers from Middle East countries

Total HBsAg prevalence in children of Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern by country

The prevalence of HBsAg among HCWs of EMRO/Middle East countries in detailed is presented in Table 1. In addition, the combined prevalence of HBsAg in countries with at least 2 papers found in searches is available in Table 2.

Table 2.

The combined prevalence of HBsAg in countries with at least 2 available papers

| Countries | Prevalence | Confidence Intervals |

|---|---|---|

| Iran | 1.38 | 1.06-1.79 |

| Iraq | 4.37 | 3.59-5.3 |

| Libya | 1.27 | 0.94-1.71 |

| Morocco | 2.5 | 1.66-3.76 |

| Pakistan | 2.07 | 1.62-2.64 |

| Sudan | 6.85 | 5.74-8.16 |

| Turkey | 1 | 0.94-1.07 |

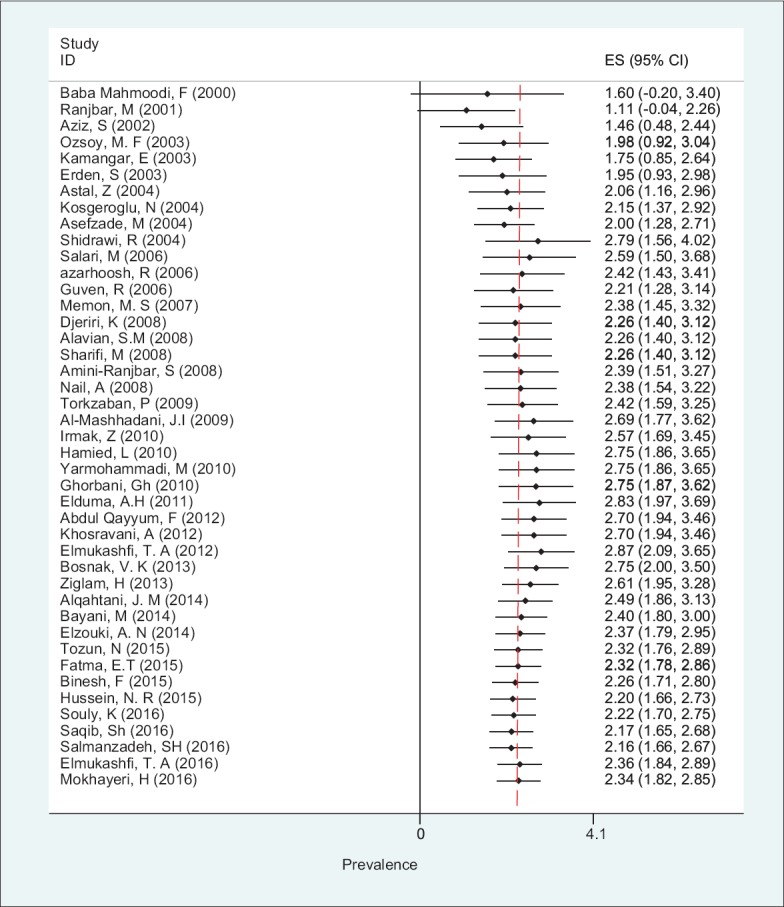

Cumulative HBsAg prevalence in children of Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries

Using random effect model, cumulative method indicates that the trends of HBsAg prevalence among HCWs decreased from 2000 to 2016 [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Forest plot of cumulative HBsAg prevalence in health care workers from Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East countries

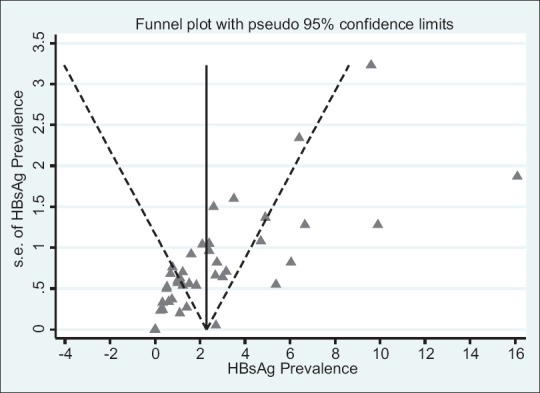

Risk of publication bias in included studies

To show publication bias, funnel plots and Egger's statistical tests were used. They indicate the lack of publication bias in this study (P = 0.3) [Figure 5].

Figure 5.

Funnel plots for the analysis of HBsAg prevalence in health care workers from EMRO and Middle East countries

Discussion

The present study was conducted to determine the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries between 2000 and 2016. According to the results obtained, the combined prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in the above regions was 2.77%. This showed descending trend in the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries from 2000 to 2016.

According to WHO report, mean frequency of occupational injuries in HCWs varies from one area to another (for instance, injuries caused by sharp objects vary from 0.2% to 4.7% per worker per year).[73] The annual HCWs exposure to HBV is 6%, which includes 66000 HCWs worldwide.[74] The present study only investigated the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWS, and studies that reported the general prevalence of hepatitis B without including HBsAg index were excluded. Thus, the prevalence obtained in the present study is expected to be less than the general prevalence of hepatitis B in HCWs. It seems that the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWS in EMRO and Middles Eastern countries is greater than that found in children (2.73%) and blood donors in these regions.[18,19] Moreover, the frequency pattern of hepatitis B varies across other Asian countries. The prevalence of HBV in 2 separate studies conducted in India was reported 3.2% and 0.4%,[75,76] and 2.4% in South Korea.[77] In African countries, 3 studies conducted in Nigeria reported the prevalence of this infection 1.1%, 4.35% and 13%,[78,79,80] and 2.9% in Rwanda,[81] 8.1% in Uganda,[82] and 6.32% in Cameroon,[83] and the prevalence of HBV in HCWs in these studies can be said to be higher compared to that reported in the present study. Studies conducted in European countries have reported a different range of prevalence of hepatitis B in HCWs, but generally the prevalence in Europe is less than that reported in the present study; for example, 1.2% in Poland,[84] 0.5% in Greece,[85] and 1.47% in Bosnia,[86] yet, 8.1% in Albania.[87] The difference in the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs can also be seen in other parts of the world. Two studies conducted in Brazil reported the prevalence of HBV 0.8% and 0.35%, which is much lower than in the present study.[88,89]

The present study showed a descending trend in the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries from 2000 to 2016. Before WHO guidelines for vaccination of children in 1992, 6 (27%) out of 22 EMRO countries implemented the program of three doses of hepatitis B vaccine for children, then, 17 (77%) countries in 2000, and all EMRO member countries in 2013 implemented children vaccination program. Clearly, with increasing vaccination cover of general population in the regional countries, vaccination cover for other risk groups will also increase and infection rate will be reduced.[90] Given their occupational conditions and their exposure to sharp objects, hepatitis B vaccination of HCWs is strongly recommended, but this does not apply to everywhere. According to a study conducted by Pruss-Ustun et al. (2005), reginal estimate of hepatitis B vaccination cover in HCWs in early 2000's varies from 18% to 77%.[91] Hepatitis B vaccination cover of HCWs in reported studies conducted in the last 10 years was 84% in Iran,[92] 74% in Pakistan,[30] 63.3% in Saudi Arabia,[93] 78.1% in Libya,[54] and 72% in Turkey,[70] indicating somewhat improved vaccination cover in these countries. Generally, with the increasing vaccination cover in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries in risk groups like HCWs, a descending trend of HBV infection can be anticipated.

In the present study, one of the limitations was a low number of studies found in relation to the number of countries in this region. This problem was alleviated by including studies that were conducted on the general population and reported the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs. In the present study, attempts were made to include the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in published articles, and student and university theses were not included. Lack of data for some countries may decrease the generalizability of findings for EMRO/Middle East regions. It is needed to search local databases for countries without any findings in future studies. It seems that there several factors that may change the pattern of HBsAg prevalence in different regions such as education and income. High (Yemen and Sudan) or low (Saudi Arabia or Turkey) prevalence of HBsAg may refers to equity in access to health care in some EMRO/Middle East countries. For example, one study showed that the status of Hepatitis B vaccination wasn't acceptable between a group of HCWs in Sudan and only less than one third of them had received all doses of vaccine,[94] while the other study in Saudi Arabia revealed that more than 70% of HCWs received HBV vaccine.[95]

Another limitation related to the absence of separate reports of prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs by age and gender, and therefore the prevalence in age and gender groups could not be reported in the present study. The strength of the present study was in its high search sensitivity for finding relevant articles, where all related keywords were used in the search.

Conclusions

According to the WHO classification, the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in EMRO and Middle Eastern countries (2.77%) between 2000 and 2016 was at a moderate level. Among the articles found, the lowest prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs was in Saudi Arabia, and the highest in Yemen. However, given the absence of more studies on the prevalence of HBsAg in HCWs in these countries, further related studies in these and other EMRO and Middle Eastern countries that had no related studies should be conducted. Data collected showed a descending trend in the prevalence of HBV in HCWs between 2000 and 2016. Improving vaccination cover of HCWs and completing their vaccination history is recommended for further reduction in this infection index.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Clinical Research Development Unit of Imam Khomeini Hospital in Kermanshah, and to all the individuals who helped us in performing this study.

References

- 1.Lesmana LA, Leung NWY, Mahachai V, Phiet PH, Suh DJ, Yao G, et al. Hepatitis B: Overview of the burden of disease in the Asia-Pacific region. Liver Int. 2006;26:3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 2.André F. Hepatitis B epidemiology in Asia, the middle East and Africa. Vaccine. 2000;18:S20–2. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barth RE, Huijgen Q, Taljaard J, Hoepelman AI. Hepatitis B/C and HIV in sub-Saharan Africa: An association between highly prevalent infectious diseases. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e1024–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Rshoud F, Coomarasamy A. Patient with Hepatitis B or C. Gynecologic and Obstetric Surgery: Challenges and Management Options. 2016:61–3. doi: 10.1002/9781118298565.ch21. [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Health Care Worker Safety 2016 [cited 2016 16.12.2016] Available from: http://www.who.int/injection_safety/toolbox/en/AM_HCW_Safety_EN.pdf .

- 6.Schillie S, Murphy T, Sawyer M, Ly K, Hughes E, Jiles R, et al. CDC guidance for evaluating health-care personnel for hepatitis B virus protection and for administering postexposure management. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shefer A, Atkinson W, Friedman C, Kuhar DT, Mootrey G, Bialek SR, et al. Immunization of health-care personnel: Recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices (ACIP) MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;60:1–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Workers” IoHc Workers'' IoHc. Recommendation of advisory committee on immunization practice (ACIP) and the hospital infection control practice advisory committee (HICPAC). MMWR, Recommendation and Report 26; 12/26/97 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Historical reported cases and estimates [17.12.2016] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/Statistics/IncidenceArchive.htm .

- 10.McMahon BJ. The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2009;49:S45–55. doi: 10.1002/hep.22898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuhail S, El Khodary R, Ahmed F. Evaluation of the routine hepatitis B immunization programme in Palestine, 1996. East Mediterr Health J. 2000;6:864–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alavian SM, Fallahian F, Lankarani KB. The changing epidemiology of viral hepatitis B in Iran. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2007;16:403–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ott J, Stevens G, Groeger J, Wiersma S. Global epidemiology of hepatitis B virus infection: New estimates of age-specific HBsAg seroprevalence and endemicity. Vaccine. 2012;30:2212–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elmukashfi TA, Balla SA, Bashir AA, Abdalla AA, Elgasim MAA, Swareldahab Z. Conditional probabilities of HBV markers among health care workers in public hospitals in White Nile State, Sudan; 2013. Global J Health Sci. 2017;9:10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Memon MS, Ansari S, Nizamani R, Khathri N, Mirza MA, Jafri W. Hepatitis B vaccination status in health care workers of two university hospitals. J Liaquat Uni Med Health Sci. 2007;6:48–51. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Djeriri K, Laurichesse H, Merle JL, Charof R, Abouyoub A, Fontana L, et al. Hepatitis B in Moroccan health care workers. Occup Med. 2008;58:419–24. doi: 10.1093/occmed/kqn071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Binesh F, Mehrparvar AH, Atefi A. Seroprevalence of HBV and immunity status of health care workers in a referral community hospital in central Iran. World Appl Sci J. 2015;33:263–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Babanejad M, Izadi N, Najafi F, Alavian SM. The HBsAg prevalence among blood donors from Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepat Mon. 2016;16:e35664. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.35664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Babanejad M, Izadi N, Rai A, Sohrabzadeh S, Alavian SM, Zangeneh A. Prevalence of HBsAg amongst healthy children in Eastern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2016;16:e35664. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malekifar P, Babanejad M, Izadi N, Alavian S M. The frequency of HBsAg in pregnant women from eastern mediterranean and middle eastern countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis? Hepat Mon. 2018;18:e58830. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.35664. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.58830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.World Health Organization. The Growing Threats of Hepatitis B and C in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: A Call for Action. World Health Organization; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nyaga VN, Arbyn M, Aerts M. Metaprop: A Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Arch Public Health. 2014;72:39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bahmani MK, Khosravi A, Mobasser A, Ghezelsofla E. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and vaccination compliance among health care workers in Fars Province, Iran. Iran J Clin Infect Dis. 2010;5:45–50. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elmukashfi TA, Ibrahim OA, Elkhidir IM, Bashir AA, Elkarim MAA. Socio-demographic characteristics of health care workers and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection in public teaching hospitals in Khartoum State, Sudan. Global J Health Sci. 2012;4:37–41. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n4p37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asif M, Raza W, Gorar ZA. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage in medical students at a medical college of Mirpurkhas. JPMA. 2011;61:680–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salehi AA, Sharifi M, Norooznejad M, Vazirian S. Seroepidemiology of HIV, HBV and HCV infections in laboratory staff (Kermanshah, 2002) J Kermanshah Univ Med Sci. 2004;7:49–54. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saffar M, Jooyan A, Mahdavi M, Khalilian A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A, B, and C and hepatitis B vaccination status among health care workers in Sari-Iran, 2003. J Mazand Univ Med Sci. 2005;15:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.AL-Janabi A, AL-Masoudy AA. Serosurvey of HIV, HCV and HBV in clinical laboratory workers of Karbala (Iraq) health care units. GJMS. 2009;4:108–11. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Daw MA, Siala IM, Warfalli MM, Muftah MI. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus markers among hospital health care workers: Analysis of certain potential risk factors. Saudi Med J. 2000;21:1157–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Attaullah S, Khan S, Naseemullah, Ayaz S, Khan SN, Ali I, et al. Prevalence of HBV and HBV vaccination coverage in health care workers of tertiary hospitals of Peshawar, Pakistan. Virol J. 2011;8:275. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hussain S, Patrick NA, Shams R. Hepatitis B and C prevalence and prevention awareness among health care workers in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Pathol. 2010;8:16–21. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adeel MY. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and Hepatitis C in health care workers in Abbottabad. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2008;20:27–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoaei P, Najafi S, Lotfi N, Vakili B, Ataei B, Yaran M, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus infection and hepatitis B surface antibody status among laboratory health care workers in Isfahan, Iran. AJTS. 2015;9:138–40. doi: 10.4103/0973-6247.162701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asefzadeh M, Sharifi M, Oliaei A. Prevalence of HBsAg carriers and AntiHBsAg in health care workers of Boali-sina teaching hospital in Qazvin. J Qazvin Univ Med Sci. 2004;32:41–6. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Azarhoush R, Borghei N, Vakili M, Latifi K. Serologic immunity of Gorgan medical personnels against hepatitis B (2003) J Gorgan Univ Med Sci. 2006;8:39–44. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayani M, Siadati S, Hajiahmadi M, Khani A, Naemi N. Hepatitis B infection: Prevalence and response to vaccination among health care workers in Babol, Northern Iran. Iran J Pathol. 2014;9:189–94. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamangar E, Atapour M, Sanei-Moghadam E, Zohour A, NayebAghaie SM. Prevalence of serologic markers of Hepatitis B and C and risk factors among dentists and physicians in Kerman, Iran. J Kerman Univ Med Sci. 2003;10:240–5. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salari M, Alavian S, Tadrisi D, Karimi A, Sadeghian H, Asadzandi M. Safety of hepatitis B immunization in health care workers. Kowsar Med J. 2006;11:343–52. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salmanzadeh S, Rahimi Z, Vaeghi Z, Meripoor M, Maniavi F. Investigation the prevalence and risk factors associated with viral hepatitis B and C among workers employed in state hospitals in Ahvaz, Iran. IJPRAS. 2016;5:380–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Amini-Ranjbar S, Motlagh M. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage among Iranian medical students and nursing staff. Am J Appl Sci. 2008;5:747–9. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ghorbani GA. Prevalence of occupational blood transmitted viral infection in health care workers after needle stick and sharp injury. Kowsar Med J. 2010;14:223–8. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alavian SM, Mansouri S, Abouzari M, Assari S, Bonab MS, Miri SM. Long-term efficacy of hepatitis B vaccination in healthcare workers of oil company hospital, Tehran, Iran (1989–2005) Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:131–4. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f1cc28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sharifi M, Borhan MK, Salmani MR, Mostajeri A, Alipour Heidari M. Correlation between anti-HBs antibody level with education status and duration of practice among dentists in Qazvin city. JIDA. 2008;19:43–9. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Baba Mahmoodi F. Evaluation of hepatitis B antibody (HBS) levels in nursing staff of Gaemshahr Razi hospital and it's variation with duration of immunity post HB vaccination. JMUMS. 2000;10:48–53. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khosravani A, Sarkari B, Negahban H, Sharifi A, Toori MA, Eilami O. Hepatitis B Infection among high risk population: A seroepidemiological survey in Southwest of Iran. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:378. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-12-378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mokhayeri H, Nazer MR, Nabavi M, Zavareh FA, Tarrahi MJ, Kayedi Z, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C in clinical staffs (Doctor and Nurse) of the hospitals in Khorramabad City, Western Iran. Health Sci. 2016;5:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Torkzaban P, Abdolsamadi H, Vaziri P. Efficacy rate of hepatitis B vaccination in vaccinated dentists in Hamadan. J Res Dent Sci. 2009;6:62–6. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yarmohammadi M. Investigating the serologic status and epidemiological aspects of health care workers' exposure to HBV and HCV viruses. Knowledge and Health. 2010;5:37–42. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ranjbar M, Keramat F, Keshavarz F. The immunogenicity of Hepatitis B vaccine in personnel of Sina hospital of Hamadan, Iran, 2001. Iran J Infect Dis Trop Med. 2002;7:55–8. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Al-Mashhadani JI, Al-Hadithi TS, Al-Diwan J, Omer A. Sociodemographic characteristics and risk factors of hepatitis B and C among Iraqi health care workers. J Fac Med Baghdad. 2009;51:308–11. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hussein NR. Prevalence of HBV, HCV and HIV and Anti-HBs antibodies positivity in healthcare workers in departments of surgery in Duhok city, Kurdistan region, Iraq. Int J Pure Appl Sci Technol. 2015;26:70–5. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hamied L, Abdullah RM, Abdullah AM. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infection in Iraq. The N Iraqi J Med. 2010;6:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elzouki AN, Elgamay SM, Zorgani A, Elahmer O. Hepatitis B and C status among health care workers in the five main hospitals in eastern Libya. J Infect Public Health. 2014;7:534–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2014.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ziglam H, El-Hattab M, Shingheer N, Zorgani A, Elahmer O. Hepatitis B vaccination status among healthcare workers in a tertiary care hospital in Tripoli, Libya. J Infect Public Health. 2013;6:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Souly K, El Kadi MA, Elkamouni Y, Biougnach H, Kreit S, Zouhdi M. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus in health care personnel in Ibn Sina hospital, Rabat, Morocco. Open J Med Microbiol. 2016;6:17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abdul Qayyum F, Mahmood K, Rashid Siraj M. Prevalence of blood borne diseases (hepatitis B & C) and strategy to protect health care workers. PJMHS. 2012;6:640–3. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aziz S, Memon A, Tily HI, Rasheed K, Jehangir K, Quraishy MS. Prevalence of HIV, hepatitis B & C amongst health workers of civil hospital Karachi. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2002;52:92–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Saqib S, Khan MZ, Gardyzi SIHS, Qazi J. Prevalence and epidemiology of blood borne pathogens in health care workers of Rawalpindi/Islamabad. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66:170–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Astal Z, Dhair M. Serologic evaluation for hepatitis B and C among healthcare workers in Southern Gaza Strip (Palestine) J Islam Univ Gaza. 2004;12:153–64. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alqahtani JM, Abu-Eshy SA, Mahfouz AA, El-Mekki AA, Asaad AM. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections among health students and health care workers in the Najran region, southwestern Saudi Arabia: The need for national guidelines for health students. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:577. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elmukashfi TA, Elkhidir IM, Ibrahim OA, Bashir AA, Elkarim MAA. Hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in public teaching hospitals in Khartoum State, Sudan. Saf Sci. 2012;50:1215–7. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v4n6p51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elduma A, Saeed N. Hepatitis B virus infection among staff in three hospitals in Khartoum, Sudan, 2006–07. East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17:474–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nail A, Eltiganni S, Imam A. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C among health care workers in Omdurman, Sudan. Sudan Journal of Medical Sciences. 2008;3:201–6. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fatma ET, Mehmet Ö, Metin D, Mahmut B. Seroprevalence of hepatitis A, hepatitis B and hepatitis C in primary health care centers of Konya, Turkey? J Clin Virol. 2015;70:S106. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv. 2015.07.245. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ozsoy M, Oncul O, Cavuslu S, Erdemoglu A, Emekdas G, Pahsa A. Seroprevalences of hepatitis B and C among health care workers in Turkey. J Viral Hepat. 2003;10:150–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bosnak VK, Karaoglan I, Namiduru M, Sahin A. Seroprevalences of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV of the healthcare workers in the Gaziantep university Sahinbey research and training hospital. Viral Hepat Dergisis. 2013;19:11–4. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Güven R, Özcebe H, Çakir B. Hepatitis B prevalence among workers in Turkey at low risk for hepatitis B exposure. East Mediterr Health J. 2006;12:749–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Erden S, Buyukozturk S, Calangu S, Yilmaz G, Palanduz S, Badur S. A study of serological markers of hepatitis B and C viruses in Istanbul, Turkey. Med Princ Pract. 2003;12:184–8. doi: 10.1159/000070757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Irmak Z, Ekinci B, Akgul A. Hepatitis B and C seropositivity among nursing students at a Turkish university. Int Nurs Rev. 2010;57:365–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2010.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kosgeroglu N, Ayranci U, Vardareli E, Dincer S. Occupational exposure to hepatitis infection among Turkish nurses: Frequency of needle exposure, sharps injuries and vaccination. Epidemiol Infect. 2004;132:27–33. doi: 10.1017/s0950268803001407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tozun N, Ozdogan O, Cakaloglu Y, Idilman R, Karasu Z, Akarca U, et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections and risk factors in Turkey: A fieldwork TURHEP study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:1020–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2015.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shidrawi R, Ali Al-Huraibi M, Ahmad Al-Haimi M, Dayton R, Murray-Lyon IM. Seroprevalence of markers of viral hepatitis in Yemeni healthcare workers. J Med Virol. 2004;73:562–5. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.EPINET. Needle-stick prevention devices. Health Devices. 1999;28:381–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hutin Y, Hauri A, Chiarello L, Catlin M, Stilwell B, Ghebrehiwet T, et al. Best infection control practices for intradermal, subcutaneous, and intramuscular needle injections. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:491–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kumar S, Begum R, Umar U, Kumari P. Hepatitis B seropositivity and vaccination coverage among health care workers in a tertiary care hospital in Moradabad, UP, India. Int J Sci Study. 2014;1:4. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singhal V, Bora D, Singh S. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in healthcare workers of a tertiary care centre in India and their vaccination status. J Vaccines Vaccin. 2011;2:2. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shin BM, Yoo HM, Lee AS, Park SK. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus among health care workers in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:58–62. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ola S, Odaibo G, Olaleye O, Ayoola E. Hepatitis B and E viral infections among Nigerian healthcare workers. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2012;41:387–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alese OO, Alese MO, Ohunakin A, Oluyide PO. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen and occupational risk factors among health care workers in Ekiti state, Nigeria. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:LC16–8. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/15936.7329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ajayi AO, Komolafe AO, Ajumobi K. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B surface antigenemia among health care workers in a Nigerian tertiary health institution. Niger J Clin Pract. 2007;10:287–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kateera F, Walker TD, Mutesa L, Mutabazi V, Musabeyesu E, Mukabatsinda C, et al. Hepatitis B and C seroprevalence among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Rwanda. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;109:203–8. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trv004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ziraba AK, Bwogi J, Namale A, Wainaina CW, Mayanja-Kizza H. Sero-prevalence and risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection among health care workers in a tertiary hospital in Uganda. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:191. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fritzsche C, Becker F, Hemmer C, Riebold D, Klammt S, Hufert F, et al. Hepatitis B and C: Neglected diseases among health care workers in Cameroon. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2013;107:158–64. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trs087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rybacki M, Piekarska A, Wiszniewska M, Walusiak-Skorupa J. Hepatitis B and C infection: Is it a problem in Polish healthcare workers? Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2013;26:430–9. doi: 10.2478/s13382-013-0088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Topka D, Theodosopoulos L, Elefsiniotis I, Saroglou G, Brokalaki H. Prevalence of hepatitis B in haemodialysis nursing staff in Athens. J Ren Care. 2012;38:76–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cabaravdic M, Delic M, Obaran E, Sahman S. Prevalence of hepatitis-B surface antigen (HBs-Ag) and anti-HCV antibody among health care workers of Canton Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Mater Sociomed. 2010;22:124. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kondili LA, Ulqinaku D, Hajdini M, Basho M, Chionne P, Madonna E, et al. Hepatitis B virus infection in health care workers in Albania: A Country still Highly Endemic for HBV Infection. Infection. 2007;35:94. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6076-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ciorlia LAS, Zanetta DMT. Hepatitis B in healthcare workers: Prevalence, vaccination and relation to occupational factors. Braz J Infect Dis. 2005;9:384–9. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702005000500005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lins L, Gomes L, Pimentel R, Falcão A, Freire S, Paraná R. Prevalence of hepatitis A, B and C and use of infection control procedures by dental health care workers in Salvador, bahia, Brazil. Gazeta Méd Bahia. 2009;79(Suppl 2):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Allison RD, Teleb N, Al Awaidy S, Ashmony H, Alexander JP, Patel MK. Hepatitis B control among children in the Eastern Mediterranean region of the World Health Organization. Vaccine. 2016;34:2403–9. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Prüss-Üstün A, Rapiti E, Hutin Y. Estimation of the global burden of disease attributable to contaminated sharps injuries among health-care workers. Am J Ind Med. 2005;48:482–90. doi: 10.1002/ajim.20230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hashemi SH, Mamani M, Torabian S. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage and sharp injuries among healthcare workers in Hamadan, Iran. Avicenna J Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014:1. doi: 10.17795/ajcmi-9949. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hegazy AA, Albar HM, Albar NH. Hepatitis B vaccination coverage and knowledge among healthcare workers at a tertiary hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. JAMPS. 2016;11:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gadour MO, Abdullah AM. Knowledge of HBV risks and hepatitis B vaccination status among health care workers at Khartoum and Omdurman teaching hospitals of Khartoum state in Sudan. Sudan J Med Sci. 2011;6:63–8. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Panhotra B, Saxena AK, Al-Hamrani HA, Al-Mulhim A. Compliance to hepatitis B vaccination and subsequent development of seroprotection among health care workers of a tertiary care center of Saudi Arabia. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33:144–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]