Abstract

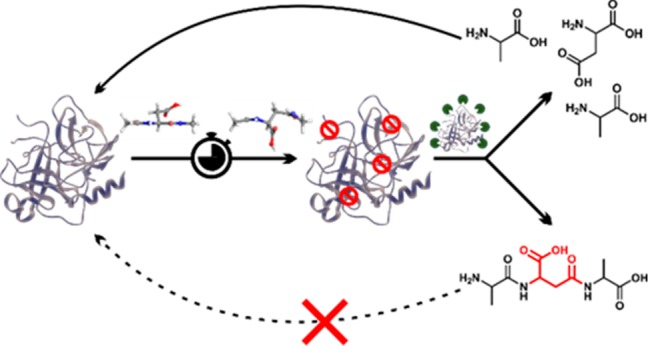

Proteinaceous aggregation is a well-known observable in Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but failure and storage of lysosomal bodies within neurons is equally ubiquitous and actually precedes bulk accumulation of extracellular amyloid plaque. In fact, AD shares many similarities with certain lysosomal storage disorders though establishing a biochemical connection has proven difficult. Herein, we demonstrate that isomerization and epimerization, which are spontaneous chemical modifications that occur in long-lived proteins, prevent digestion by the proteases in the lysosome (namely, the cathepsins). For example, isomerization of aspartic acid into l-isoAsp prevents digestion of the N-terminal portion of Aβ by cathepsin L, one of the most aggressive lysosomal proteases. Similar results were obtained after examination of various target peptides with a full series of cathepsins, including endo-, amino-, and carboxy-peptidases. In all cases peptide fragments too long for transporter recognition or release from the lysosome persisted after treatment, providing a mechanism for eventual lysosomal storage and bridging the gap between AD and lysosomal storage disorders. Additional experiments with microglial cells confirmed that isomerization disrupts proteolysis in active lysosomes. These results are easily rationalized in terms of protease active sites, which are engineered to precisely orient the peptide backbone and cannot accommodate the backbone shift caused by isoaspartic acid or side chain dislocation resulting from epimerization. Although Aβ is known to be isomerized and epimerized in plaques present in AD brains, we further establish that the rates of modification for aspartic acid in positions 1 and 7 are fast and could accrue prior to plaque formation. Spontaneous chemistry can therefore provide modified substrates capable of inducing gradual lysosomal failure, which may play an important role in the cascade of events leading to the disrupted proteostasis, amyloid formation, and tauopathies associated with AD.

Short abstract

Spontaneous chemical modifications to long-lived proteins, isomerization and epimerization, prevent degradation in the lysosome and may account for related pathology observed in Alzheimer’s disease.

Introduction

The active balancing of protein synthesis and degradation, or proteostasis, is an ongoing and critical process in most cells.1 Proteins must be created, carry out their requisite function, and then be recycled once they are no longer needed or have become nonfunctional. Several pathways are available for protein degradation, including the proteasome, macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy.2,3 The autophagy-related pathways deliver proteins to lysosomes, which are acidic organelles containing a host of hydrolases, including many proteases.4 Cargo taken into cells via endocytosis is also typically delivered to lysosomes for degradation. Regardless of the pathway, after cargo fuses with a lysosome, endopeptidases cleave proteins at internal sites, shortening proteins to peptides, which are then further digested from both termini by exopeptidases. After protein digestion has been completed, transporter proteins in the lysosomal membrane release (primarily) individual amino acids back into the cytosol for new protein synthesis or energy production.5 Lysosomes are crucial for maintaining cellular homeostasis, but they are also uniquely susceptible to problems when substrates cannot be hydrolyzed. For example, genetic modifications reducing the efficacy of a lysosomal hydrolase are the most common cause of lysosomal storage disorders. These devastating diseases involve “storage” of failed lysosomal bodies within cells, which eventually leads to cell death and is particularly problematic for postmitotic cells such as neurons.6 Symptoms in lysosomal storage disorders usually emerge in infancy or childhood, are often associated with neurodegeneration, and are typically fatal.7

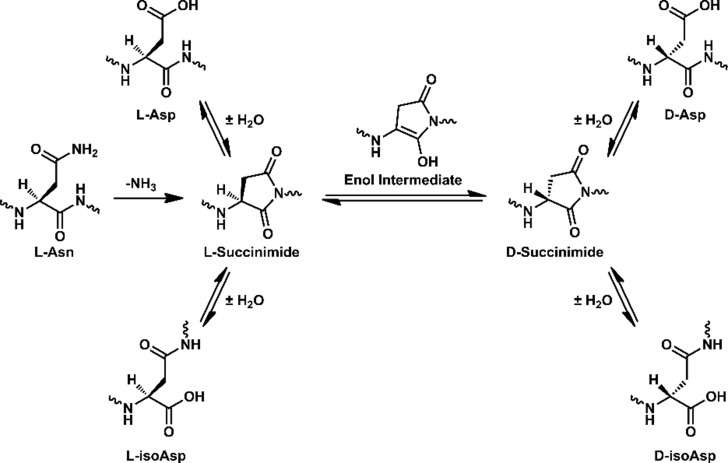

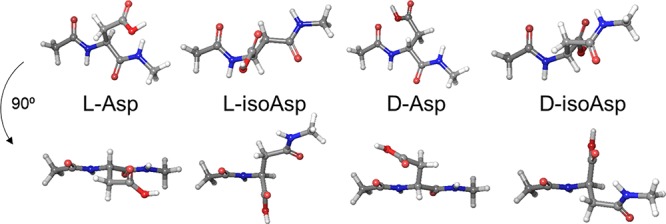

Long-lived proteins8 are a primary target of the lysosome because they become modified and lose efficacy over time. A well-known example of this occurs with mitophagy,3 wherein old mitochondria are recycled in their entirety. Contributing factors that lead to long-lived protein deterioration include a variety of spontaneous chemical modifications, i.e., modifications not under enzymatic control.8 Some of these modifications are very subtle and difficult to detect, including isomerization and epimerization.9 Isomerization occurs primarily at aspartic acid, when the side chain inserts into and elongates the peptide backbone (Scheme 1).10 Identical products are also created during deamidation of asparagine, which further results in chemical transformation from one amino acid to another.11 Epimerization occurs when an amino acid side chain inverts chirality from the l- to d- configuration. Peptide isomerization and epimerization do not have readily identifiable bioanalytical signatures, but both modulate structure in a subtle, yet significant, way (see Figure 1). Studies on the eye lens have shown that epimerization and isomerization are among the most abundant modifications observed in extremely long-lived proteins.12−14 However, knockout experiments in mice have also revealed the importance of these modifications over much shorter time scales. For example, removal of the repair enzyme for l-isoAsp, protein-isoaspartyl methyl transferase (PIMT),15 leads to lethal accumulation of isomerized protein in just 4–6 weeks.16,17 This reveals that isomerization of aspartic acid is sufficiently dangerous that an enzyme has evolved to repair it.

Scheme 1. Pathways for Isomerization of Aspartic Acid and Deamidation of Asparagine.

Figure 1.

Model structures of the aspartic acid isomers, where the isostructure conformation closest to native backbone orientation is shown. Two views are illustrated for each isomer.

The importance of peptide isomers is further revealed in the uses nature has found for them. For example, single amino acid sites are intentionally epimerized in many venoms and in signaling neuropeptides in crustaceans.18,19 The corresponding l-only peptides are not biologically active, confirming the importance of the chiral modifications. In addition, it is thought that epimerization is beneficial for these peptides because it allows them to escape, or prolong the time required for, proteolysis.20 In fact, it is well-known that sites of epimerization and isomerization are both generally resistant to protease action, but the ramifications of such chemistry in the context of lysosome function have not been previously examined. Despite this absence, numerous studies have established the importance of protein degradation in lysosomes. For example, knockout mice lacking cathepsin D grow normally for ∼2 weeks but then die before the end of 4 weeks.21 Examination of the neurons from these mice revealed an abundance of failed lysosomal bodies, similar to those observed in lysosomal storage disorders. Other research has shown that knockout mice lacking cathepsins B and L die within 2–4 weeks of birth. Again, accumulation of failed lysosomal bodies was observed in neurons of these mice.22 Although cathepsins can also be found outside the lysosome,23 these results confirm a significant, and likely fatal, impact on the lysosomal system when critical cathepsins are absent.

Amyloid aggregates or proteins that are otherwise insoluble are also targeted to lysosomes for degradation.24 Amyloid aggregation has also captured the majority of attention as the potential cause of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but significant evidence also supports lysosomal storage as an underlying cause. For example, AD shares many pathological similarities with lysosomal storage disorders, including prolific storage of failed lysosomal bodies, accumulation of senile plaques, and formation of neurofibrillary tangles.25,26 In fact, scanning-electron microscopy images of lysosomal storage (in neurons) are virtually indistinguishable between the two diseases. The lysosomal storage observed in AD precedes formation of amyloid deposits,27 hinting that lysosomal malfunction may occur upstream of the events leading to extracellular amyloid aggregation. The parallels between the two diseases have also been offset by differences. For example, lysosomal storage disorders typically afflict youth and can progress rapidly, while AD typically occurs late in life over a longer time scale. Therefore, a mechanism accounting for the commonalities and differences between the diseases has been difficult to identify, but an intriguing possibility does exist.

The primary constituents of senile plaques, Aβ and Tau, are both long-lived proteins that are subject to isomerization and epimerization.8 In fact, Aβ is significantly epimerized and isomerized in the brains of people with AD.28 If isomerization and epimerization prevent lysosomal protein digestion, then a common link between lysosomal storage disorders and AD would be established. In fact, AD would essentially represent a different type of lysosomal storage disorder, one that operates in reverse of the classical disease. Rather than failure of a modified enzyme or modified transporter to clear waste molecules, failure to digest or transport modified waste molecules would be operative and eventually lead to lysosomal storage. Close examination of another complex age-related disease, macular degeneration, reveals that there is precedence for substrate-induced lysosomal storage.29

Results and Discussion

Defining Limitations of Cathepsin Digestion

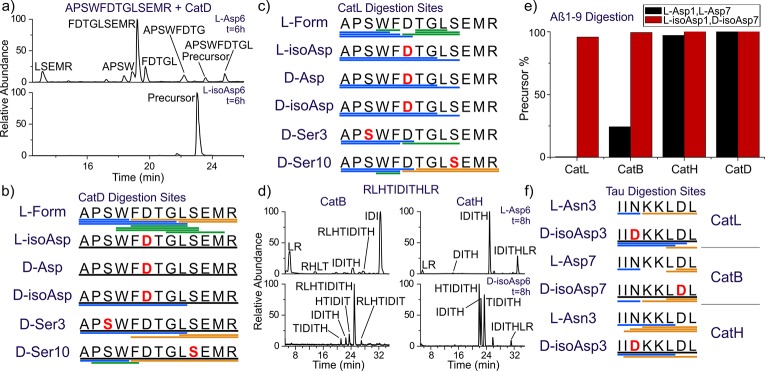

A series of isolated digestions of synthetic peptides both in canonical form and with isomerized or epimerized (iso/epi) sites were performed, and the results are summarized in Figure 2. Experiments were conducted with cathepsins D, L, B, and H. This collection includes all of the most abundant cathepsins and all modes of function, i.e., endo-, carboxy-, and aminopeptidases.30,31 The peptide APSWFDTGLSEMR (αB57–69), derived from αB-crystallin, was used as the initial test substrate. It contains both Ser and Asp residues known to be modified in the eye lens.32 Furthermore, Ser59, Asp62, and Ser66 are each separated by other residues, allowing for semi-independent examination. Furthermore, the canonical sequence is a good substrate for proteolysis. Digestion of the native form with cathepsin D in acetate buffer at pH 4.5 yields the results shown in the upper part of Figure 2a. The LC-MS derived ion chromatogram reveals many peptide fragments and almost complete consumption of the precursor. Clearly, the canonical all-l version of APSWFDTGLSEMR is easily digested. Substitution of l-Asp with l-isoAsp yields the lower chromatogram, where after 6 h, the precursor remains basically untouched. A single modification therefore prevents cathepsin D from digesting an entire 13 residue sequence, shutting down peptide hydrolysis at seven different sites. To more easily visualize the results in a condensed fashion, peptide fragments resulting from proteolysis are represented by color-coded lines below the peptide sequence as shown in Figure 2b (full chromatograms are also provided in the Supporting Information). The data from Figure 2a correspond to the top two rows of the results shown in Figure 2b. Data for the other Asp isomers and both Ser epimers are shown in the remaining slots of Figure 2b. All three non-native forms of aspartic acid essentially prevent digestion by cathepsin D. Furthermore, epimerization of the less bulky serine side chain also modulates cathepsin D action, preventing cleavage at one or more preferred sites even when the epimerized serine is located six residues away. Significant residual precursor is detected for all modifications, suggesting decreased affinity for the iso/epi modified peptides in general. Results for analogous experiments conducted in acetate buffer at pH 5.5 with cathepsin L are shown in Figure 2c. The canonical peptide is digested into many peptide fragments, including small di- and tripeptides. Cathepsin L is one of the most aggressive lysosomal proteases and is able to cleave more sites in the iso/epi modified peptides relative to cathepsin D. Furthermore, precursor survival is not observed with cathepsin L. However, the sites where digestion occurs are all shifted well away from iso/epi modified residues in every instance, and the number of peptide fragments observed is still reduced relative to the canonical form. The results from cathepsin L and D reveal that digestion by endopeptidase action is significantly hampered by iso/epi modifications across wide regions of sequence.

Figure 2.

(a) LC chromatogram for digestion of APSWFDTGLSEMR by cathepsin D. Summary of digestion by (b) cathepsin D and (c) cathepsin L. Each bar represents a fragment detected in the LC-MS chromatogram, color-coded by N-terminal (blue), C-terminal (gold), and internal (green). Undigested precursor >50% relative intensity is represented by a black line. (d) LC chromatograms for digestion of RLHTIDITHLR by exopeptidases cathepsins B and H for the native isomer (upper traces) and d-isoAsp isomer (lower traces). (e) Summary of digestion of Aβ1–9 (l-Asp1, l-Asp7) vs (l-isoAsp1, d-isoAsp7) by major cathepsins. Only the canonical isomer is digested. (f) Summary of digestion of 594IINKKLDL601 from Tau using the same color scheme.

The lysosomal task of reducing proteins and peptides into individual amino acids is never completed by endopeptidases, making examination of exopeptidases important. We used a palindromic peptide (RLHTIDITHLR) to systematically explore the limits of exopeptidase activity, and the results for experiments with cathepsins H and B are shown in Figure 2d. For cathepsin B, the canonical sequence is rapidly degraded (CatB upper trace). None of the precursor remains, and only a few fragments are detectable. This is consistent with thorough digestion, producing amino acids or peptides too small to be retained on the column. In contrast, placement of an isomerized residue in the central position, d-isoAsp, halts digestion considerably (CatB lower trace). The most abundant product corresponds to a single cleavage, removal of the C-terminal LR dipeptide. When acting as an exopeptidase, cathepsin B preferentially removes dipeptides.30 Note, endopeptidase activity leads to the bond cleavages observed on the N-terminal side of the peptide. Similar results are obtained for cathepsin H, which behaves as an aminopeptidase, removing a single N-terminal amino acid at a time.30 The native peptide precursor is completely depleted (CatH upper trace), but a few larger peptide fragments remain relative to digestion by cathepsin B. This may relate to reduced affinity or slower progress due to removal of a single amino acid at a time. In any case, the isomerized peptide is digested noticeably less under identical conditions (CatH lower trace). Interestingly, cathepsin H is able to penetrate within one amino acid of the iso/epi residue compared with two for cathepsin B. This can be rationalized because cathepsin H does not need to accommodate two amino acids in the catalytic site. Some endopeptidase activity is also observed for cathepsin H. Similar results were obtained in experiments examining l-Ser versus d-Ser in the central position (see Figure S14). Taken together, these results illustrate significant disruption of proteolysis by iso/epi modifications for both the major endo- and exopeptidases in the lysosome.

The results for additional peptide targets relevant to AD are shown in Figure 2e,f (Aβ1–9 and Tau 594IINKKLDL601). The two aspartic acids near the N-terminus of Aβ, Asp1, and Asp7 are highly isomerized in amyloid plaques28 and represent an interesting target where multiple proximal iso/epi modifications can be found. Isomerization of Aβ is known to inhibit serum protease action, suggesting that cathepsins may likewise be stymied.33 Experiments conducted on canonical Aβ1–9 and a double isomer (l-isoAsp1, d-isoAsp7) are summarized in Figure 2e, where the fraction of remaining precursor from each peptide is shown for each cathepsin. Cathepsin B and L easily deplete the precursor for the canonical peptide but are unable to significantly reduce the amount of precursor for the double isomer. Interestingly, cathepsin D cleaves few sites34 in Aβ and is unable to cleave any portion of Aβ1–9 even in canonical form. Similarly, cathepsin H exhibits low affinity for the N-terminal residues in Aβ1–9 and digests the canonical peptide only marginally while leaving the isomerized form intact. The N-terminal portion of Aβ is therefore generally resistant to lysosomal protease action and home to multiple sites of modification that can further frustrate proteolysis, making the prospects for Aβ to contribute to lysosomal failure strong. Experiments on an aged sample of Aβ1–42 yielded similar results (Figure S13). The highly isomerized N-terminal region was not digested by Cathepsin L while digestion of the C-terminal portion not proximal to any isomerization was cleaved in comparable fashion for both native and aged Aβ1–42.

Tau-mediated pathology is also strongly associated with AD, making it an important target to consider.35 Asn596 in Tau is known to deamidate,36 which will yield conversion to Asp and iso/epi modifications according to the pathway illustrated in Scheme 1. As a long-lived protein, Tau could also isomerize at Asp600. Isomerization at both sites is explored for the peptide fragment 594IINKKLDL601 in Figure 2f for cathepsins B, L, and H. The canonical peptide is rapidly consumed for all three cathepsins, but introduction of d-isoAsp at either position significantly perturbs the locations of proteolytic cleavage sites and leads to observation of abundant undigested precursor in all cases. These results reveal that inhibited proteolysis in the vicinity of iso/epi modified residues is likely a general feature for any peptide sequence, and long-lived proteins known to be modified in the brain will be difficult for the lysosome to break down into amino acids.

Isomer Digestion in Living Cells

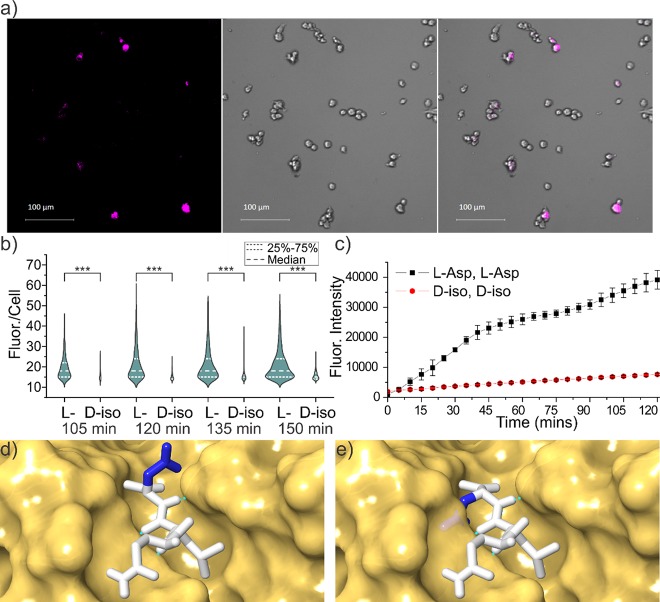

To explore additional lysosomal proteases, experiments were conducted with fully active lysosomes in SIM-A9 mouse microglial cells, as shown in Figure 3. For the peptide target, the N-terminal portion of Aβ was selected, and microglial cells were used because they are active participants in the clearance of Aβ within the brain.37 Chimeric peptides (R8-EedanDAEFRHDKdabG, where the Glu and Lys have been modified with edans and dabcyl, respectively) consisting of a cell-penetrating portion combined with an Aβ probe sequence were synthesized. Polyarginine was used for cell penetration, which is known to deliver cargo to the lysosome.38 The probe portion of the peptide remains dark when intact as the edans fluorescence is efficiently quenched by dabcyl. Upon cleavage of the probe sequence, the quencher can separate, and edans will emit broadly around 490 nm. Results for Aβ1–7 (l-Asp1, l-Asp7) as the probe are shown in Figure 3a, revealing that fluorescence is observed after 150 min as expected. In comparison, the d-isoAsp1/d-isoAsp7 probe yields lower intensity fluorescence in terms of quartile range, median, and number (including exceptionally bright cells), as shown in Figure 3b. Statistical comparison of the results with the Mann–Whitney U test reveals that differences in digestion are significant for all time points. Higher resolution images confirmed that the fluorescence was punctate and overlapping with organelles stained by lysotracker, consistent with delivery to the endosomal/lysosomal system (Figures S8 and S9). Taken together, these results suggest that there is not an unknown protease in the lysosome engineered to digest iso/epi sites.

Figure 3.

(a) Sample images of SIM-A9 mouse microglial cells after 150 min incubation with cleavable peptide target with all l-residues, fluorescence from 481 to 499 nm (left), bright-field (middle), and overlay (right). (b) Violin plot showing quantitative comparison of fluorescence intensity per cell from Aβ1–7 cleavage for canonical and the d-isoAsp1/d-isoAsp7 isomers as a function of incubation time. *** p < 0.001. (c) Fluorescence intensity as a function of time for incubation of same peptide with cathepsin L only. (d) Active site of cathepsin L with native peptide substrate bound and (e) mutated epimer with d-Asp side chain highlighting inherent steric clash if backbone orientation is maintained. Structures derived from PDB ID 3K24 with hydrogen bonds indicated by green dashed lines.

Interestingly, the microglial results can be largely recapitulated by examination of the same chimeric peptide incubated with only cathepsin L, as shown in Figure 3c and Figure S1. Both the rates and magnitude of the differential closely match the results obtained in living cells. These findings are consistent with previous observations that cathepsin L is one of the most important lysosomal proteases and can account for ∼40% of all protein digestion in the lysosome.30 The accurate reproduction confirms the validity of the LC-MS approach that yielded the results shown Figure 2. Furthermore, the effects of iso/epi modifications are more accurately determined under controlled incubation where canonical peptides without additional modifications can be tested. For example, Aβ1–7 (d-isoAsp, d-isoAsp) itself is almost completely resistant to degradation, yet proteolysis with cathepsin L is increased by a factor of ∼7 after decoration with hydrophobic chromophores needed for examination in cells (Figure S2). This suggests that the difference between digestions shown in Figure 3b is significantly underestimated relative to the true inhibiting power of the d-isoAsp modifications.

The results in Figures 2 and 3a,b can easily be rationalized by a molecular level inspection of the interaction between a protease and substrate peptide. In Figure 3d, the X-ray crystal structure for binding of a peptide substrate to cathepsin L is shown.39 The protease active site consists of a channel where several hydrogen bonds orient the peptide backbone of the substrate. Intimate contact and alignment of the substrate backbone is required to bring the cleavage site into proximity with the catalytic actors. Favorable or unfavorable interactions with side chains protruding above the groove determine the sequence selectivity, but introduction of a d-amino acid with the peptide backbone remaining properly oriented would result in the side chain projecting directly into the wall of the binding groove (Figure 3e). Similarly, isoAsp modifications disrupt both the backbone hydrogen bond partner spacing and relative orientation (Figure 1), making for an even less tractable situation. These structural alterations make it impossible for iso/epi modified residues to fit properly into the catalytic binding site. Given the similarities inherent in the function and substrate for every protease, comparable complications are likely to exist for all proteases intended to cleave peptides composed solely of canonical l-residues. Perhaps it is not surprising that poor proteolysis is observed for iso/epi modified peptides even in glial cells where a full complement of lysosomal proteases is available.

Time Frame for Aspartic Acid Isomerization

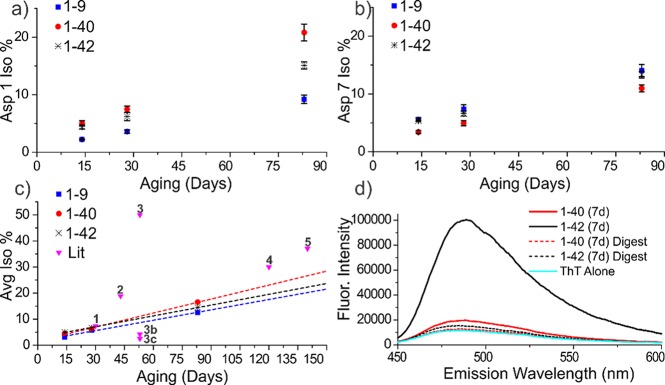

Given that Aβ plays an important role in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and is highly isomerized in amyloid plaques,28,40 we set out to determine the incubation times needed to yield such extensive modifications. Following incubation of Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42, and Aβ1–9 in tris buffer at 37 °C, the degree of isomerization was measured, and the results are shown as a function of time in Figure 4a,b. To quantitate the isomerization of Asp1 and Asp7 independently, aged Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 were first digested with chymotrypsin, yielding 1DAEF4 and 5RHDSGY10 peptides, which were subsequently analyzed by LC-MS (see Figures S5 and S6). Isomerization occurs rapidly at both aspartic acids for both full length peptides, yielding roughly 14% combined isomerization within 30 days. This rate is comparable to previous examination41 of Aβ1–16 and to isomerization of Asp151 in αA-crystallin (when determined for the peptide fragment 146IQTGLDATHAER157).42 It is also consistent with other isomerization rates cited in the literature as shown in Figure 4c,10,43−45 where the only significantly faster rates involve Asp–Gly sequences. Detailed study of deamidation, which forms an identical succinimide ring intermediate preceding isomerization, revealed the fastest rates for analogous Asn–Gly sites.46

Figure 4.

Isomerization % as a function of time for (a) Asp1 and (b) Asp7. (c) Average isomerization rate for Asp1 and Asp7 relative to rates from the literature. (d) ThT assay after 7 days confirming that any fibrils are largely digested during analysis. Data points: 1,43 2,42 3,44 3b,c (estimated rate of the VYPDGA peptide from the literature point 3 modified to correspond to VYPDSA and VYPDAA based on known deamidation rates.47), 4,45 and 5.46

These experiments were conducted at μM concentrations, which is sufficient for the formation of amyloid fibrils. The presence of amyloid was examined by ThT assay after 7 days as shown in Figure 4d. The assay reveals that Aβ1–42 had already formed fibrils within 7 days, while Aβ1–40 was just entering fibril formation, consistent with previous reports.47 After digestion with chymotrypsin, the fluorescence diminishes substantially, suggesting that fibrils are broken up and should not significantly influence the analysis. Interestingly, amyloid formation appears to slightly increase the rate of isomerization for Asp1 but in general does not significantly influence the rates. This conclusion is further supported by the observation that the rates do not vary greatly from the results obtained for Aβ1–9, which does not form fibrils.41

Framework Connecting Lysosomal Failure and AD

Long-lived proteins are subject to many spontaneous chemical modifications, including subtle changes such as iso/epi modifications that may seem harmless and are easily overlooked. Nevertheless, heavy isotope pulse-chase experiments in mice have shown that long-lived proteins in the brain are more commonplace than previously realized and can persist for timespans exceeding one year.48 These long-lived proteins are part of the overall equation that must be balanced to maintain proteostasis and will therefore be targeted for degradation at some point. Our results reveal that isomerized and epimerized sites in long-lived proteins resist digestion by the primary cathepsins present in lysosomes. Both epimerization (Ser and Asp) and isomerization (Asp) effectively prevent proteolysis at the site of modification and nearby residues for both endo- and exopeptidases. Long-lived proteins targeted to the lysosome are therefore expected to produce residual peptide fragments that are too long to be recognized by the transporters responsible for releasing digested amino acids back to the cytosol. Additionally, the residual peptides will contain an unnatural amino acid that would be expected to further frustrate transporter recognition. Accumulation of these byproducts within the lysosomal machinery is therefore possible. In fact, interference with lysosomal function has already been documented in similar circumstances with pyroglutamate modified Aβ, where the influence on proteolysis is significantly less pronounced.49

We have demonstrated that iso/epi modifications significantly inhibit lysosomal digestion in glial cells, but prior work has additionally shown that such modifications are toxic. Makarov and co-workers have examined isomerization of the N-terminal portion of Aβ in relation to the idea that such modifications enhance amyloid formation in the presence of zinc ions. They found that isomerized Aβ1–42 was more toxic than the canonical form when incubated with several different cell lines (NSC-hTERT, SK-N-SH, and SH-SY5Y).50 Furthermore, cell death by apoptosis rather than necrosis was more prevalent in the case of isomerized Aβ, indicating an alternate and more specific mechanistic pathway. Importantly, related experiments have demonstrated that Aβ localizes into the lysosome when incubated with SH-SY5Y cells,51 suggesting that the toxicity could be reasonably attributed to lysosomal pathology instead. Toxic effects have also been found in animal studies.52 Perhaps most strikingly, injection of isomerized Aβ1–16 leads to significantly increased amyloid plaque accumulation in 5XFAD transgenic mice whereas canonical Aβ1–16 does not.53 Importantly, Aβ1–16 does not contain the amyloid forming portion of the peptide.54 Although these data could be interpreted to support to the zinc-mediated amyloid aggregation hypothesis, our findings suggest that disruption of the lysosomal system could also explain the results. Introduction of isomerized Aβ1–16 could lead to lysosomal failure, followed by disrupted proteostasis and the observed increase in amyloid plaque formation.

We have established that isomerization of Aβ is relatively fast. The residence time of Aβ in the human brain is difficult to determine due to the multiple destinations and pathways that can be taken, but studies have shown that the fraction of Aβ escaping into cerebrospinal fluid persists beyond 30 h in a healthy individual.55 Similar studies have shown that clearance rates for Aβ are mismatched relative to production in AD individuals,56 which suggests that some fraction evades degradation and may persist for longer times. The rates in Figure 4 allow for a small degree of isomerization (∼0.2%) even within a 30 h time frame. Furthermore, any fraction of Aβ residing in the brain for a week or more would be expected to isomerize significantly. The N-terminal region of Aβ is disordered in amyloid structures determined by NMR,55,57 which may allow free access to the required succinimide intermediate while providing some catalytic interactions that favor isomerization. Aβ is therefore a likely source of isomerized residues in the brain, but a few reports have shown that Tau can also be isomerized due to deamidation at positions 596 and 698, or isomerization of Asp at positions 510 and 704.58,59 The size and largely unstructured nature of Tau60 make it almost certain that other sites of isomerization also exist. There is ample evidence that the proteins most strongly associated with AD pathology are subject to iso/epi modifications that could lead to lysosomal failure.

Conclusion

Iso/epi modifications are clearly generated on a relatively short time scale and prevent cathepsin digestion of nearby peptide bonds. Although other proteolytic pathways exist within cells that may also encounter difficulties with iso/epi modifications, lysosomes are uniquely vulnerable because undigested byproducts cannot escape the lysosomal membrane and can eventually cause failure and storage of the entire organelle. When this sequence of events is triggered in lysosomal storage disorders, the consequences are dramatic and often fatal. Malfunction of the lysosome is also strongly associated with the pathology of AD, as are misfolding and aggregation of both Aβ and Tau. Lysosomal failure caused by the iso/epi modifications documented to exist in both Aβ and Tau offers a direct connection between these observations and a potential new pathway to explore for the underlying cause and treatment of AD.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for funding from the NIH (R01GM107099 to R.R.J., and R01NS091616, R21NS106949, and R25GM119975 to B.D.F.). Min Xue is kindly thanked for allowing us to use his fluorescent plate reader. Hill Harman, Gal Bitan, Pablo Martinez, and Joe Loo are acknowledged for helpful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00369.

Materials and methods, spontaneous deamidation and isomerization pathway, additional digestion rate data, and LCMS data (PDF)

Author Contributions

§ T.R.L. and D.L.R. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Kaushik S.; Cuervo A. M. Proteostasis and Aging. Nat. Med. 2015, 21 (12), 1406–1415. 10.1038/nm.4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N. Autophagy: Process and Function. Genes Dev. 2007, 21 (22), 2861–2873. 10.1101/gad.1599207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic I. Proteasomal and Autophagic Degradation Systems. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86 (1), 193–224. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-061516-044908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzio J. P.; Hackmann Y.; Dieckmann N. M. G.; Griffiths G. M. The Biogenesis of Lysosomes and Lysosome-Related Organelles. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6 (9), a016840–a016840. 10.1101/cshperspect.a016840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissa B.; Beedle A.; Govindarajan R. Lysosomal Solute Carrier Transporters Gain Momentum in Research. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2016, 100 (5), 431–436. 10.1002/cpt.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselyov K.; Jennings J. J. Jr.; Rbaibi Y.; Chu C. T. Autophagy, Mitochondria and Cell Death in Lysosomal Storage Diseases. Autophagy 2007, 3 (3), 259–262. 10.4161/auto.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt F. M.; Boland B.; van der Spoel A. C. Lysosomal Storage Disorders: The Cellular Impact of Lysosomal Dysfunction. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 199 (5), 723–734. 10.1083/jcb.201208152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truscott R. J. W.; Schey K. L.; Friedrich M. G. Old Proteins in Man: A Field in Its Infancy. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41 (8), 654–664. 10.1016/j.tibs.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson E. T. Strategies for Analysis of Isomeric Peptides. J. Sep. Sci. 2018, 41 (1), 385–397. 10.1002/jssc.201700852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger T.; Clarke S. Deamidation, Isomerization, and Racemization at Asparaginyl and Aspartyl Residues in Peptides - Succinimide-Linked Reactions That Contribute to Protein-Degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 1987, 262 (2), 785–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reissner K. J.; Aswad D. W. Deamidation and Isoaspartate Formation in Proteins: Unwanted Alterations or Surreptitious Signals?. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2003, 60 (7), 1281–1295. 10.1007/s00018-003-2287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooi M. Y. S.; Truscott R. J. W. Racemisation and Human Cataract. d-Ser, d-Asp/Asn and d-Thr Are Higher in the Lifelong Proteins of Cataract Lenses than in Age-Matched Normal Lenses. Age (Omaha). 2011, 33 (2), 131–141. 10.1007/s11357-010-9171-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon Y. A.; Sabbah G. M.; Julian R. R. Identification of Sequence Similarities among Isomerization Hotspots in Crystallin Proteins. J. Proteome Res. 2017, 16 (4), 1797–1805. 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii N.; Takata T.; Fujii N.; Aki K. Isomerization of Aspartyl Residues in Crystallins and Its Influence upon Cataract. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Gen. Subj. 2016, 1860 (1), 183–191. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. X.; Doyle H. A.; Mamula M. J.; Aswad D. W. Protein Repair in the Brain, Proteomic Analysis of Endogenous Substrates for Protein L-Isoaspartyl Methyltransferase in Mouse Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281 (44), 33802–33813. 10.1074/jbc.M606958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto A.; Takagi H.; Kitamura D.; Tatsuoka H.; Nakano H.; Kawano H.; Kuroyanagi H.; Yahagi Y.; Kobayashi S.; Koizumi K.; et al. Deficiency in Protein L-Isoaspartyl Methyltransferase Results in a Fatal Progressive Epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 1998, 18 (6), 2063–2074. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-06-02063.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E.; Lowenson J. D.; MacLaren D. C.; Clarke S.; Young S. G. Deficiency of a Protein-Repair Enzyme Results in the Accumulation of Altered Proteins, Retardation of Growth, and Fatal Seizures in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1997, 94 (12), 6132–6137. 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreil G. D-AMINO ACIDS IN ANIMAL PEPTIDES. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997, 66 (1), 337–345. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia C.; Lietz C. B.; Yu Q.; Li L. Site-Specific Characterization of D -Amino Acid Containing Peptide Epimers by Ion Mobility Spectrometry. Anal. Chem. 2014, 86 (6), 2972–2981. 10.1021/ac4033824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checco J. W.; Zhang G.; Yuan W.; Yu K.; Yin S.; Roberts-Galbraith R. H.; Yau P. M.; Romanova E. V.; Jing J.; Sweedler J. V. Molecular and Physiological Characterization of a Receptor for D -Amino Acid-Containing Neuropeptides. ACS Chem. Biol. 2018, 13 (5), 1343–1352. 10.1021/acschembio.8b00167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike M. Cathepsin D Deficiency Induces Lysosomal Storage with Ceroid Lipofuscin in Mouse CNS Neurons. Neurosci. Res. 2000, 38 (18), S29. 10.1016/S0168-0102(00)81020-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felbor U.; Kessler B.; Mothes W.; Goebel H. H.; Ploegh H. L.; Bronson R. T.; Olsen B. R. Neuronal Loss and Brain Atrophy in Mice Lacking Cathepsins B and L. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99 (12), 7883–7888. 10.1073/pnas.112632299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papassotiropoulos A.; Bagli M.; Kurz A.; Kornhuber J.; Förstl H.; Maier W.; Pauls J.; Lautenschlager N.; Heun R. A Genetic Variation of Cathepsin D Is a Major Risk Factor for Alzheimer’s Disease. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 47 (3), 399–403. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A.; Kwon Y. T. Degradation of Misfolded Proteins in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Therapeutic Targets and Strategies. Exp. Mol. Med. 2015, 47 (3), e147–e147. 10.1038/emm.2014.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D. M.; Nixon R. A.. Autophagy Failure in Alzheimer’s Disease and Lysosomal Storage Disorders : A Common Pathway To Neurodegeneration? In Autophagy of the Nervous System; World Scientific, 2018; pp 237–257. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R. A.; Yang D. S. Autophagy Failure in Alzheimer’s Disease-Locating the Primary Defect. Neurobiol. Dis. 2011, 43 (1), 38–45. 10.1016/j.nbd.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon R. A. Amyloid Precursor Protein and Endosomal–lysosomal Dysfunction in Alzheimer’s Disease: Inseparable Partners in a Multifactorial Disease. FASEB J. 2017, 31 (7), 2729–2743. 10.1096/fj.201700359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roher A. E.; Lowenson J. D.; Clarke S.; Wolkow C.; Wang R.; Cotter R. J.; Reardon I. M.; Zurcherneely H. A.; Heinrikson R. L.; Ball M. J.; et al. Structural Alterations in the Peptide Backbone of Beta-amyloid Core Protein May Account for its Deposition and Stability in Alzheimer’s-disease. J. Biol. Chem. 1993, 268 (5), 3072–3083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Zhou J.; Fishkin N.; Rittmann B. E.; Sparrow J. R. Enzymatic Degradation of A2E, a Retinal Pigment Epithelial Lipofuscin Bisretinoid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133 (4), 849–857. 10.1021/ja107195u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohley P.; Seglen P. O. Proteases and Proteolysis in the Lysosome. Experientia 1992, 48 (2), 151–157. 10.1007/BF01923508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller S.; Dennemärker J.; Reinheckel T. Specific Functions of Lysosomal Proteases in Endocytic and Autophagic Pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta, Proteins Proteomics 2012, 1824 (1), 34–43. 10.1016/j.bbapap.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon Y. A.; Collier M. P.; Riggs D. L.; Degiacomi M. T.; Benesch J. L. P.; Julian R. R. Structural and Functional Consequences of Age-Related Isomerization in α-Crystallins. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294 (19), 7546–7555. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.007052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szendrei G. I.; Prammer K. V.; Vasko M.; Lee V. M.-Y.; Otvos L. The Effects of Aspartic Acid-Bond Isomerization on in Vitro Properties of the Amyloid β-Peptide as Modeled with N-Terminal Decapeptide Fragments. Int. J. Pept. Protein Res. 1996, 47 (4), 289–296. 10.1111/j.1399-3011.1996.tb01358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDermott J. R.; Gibson A. M. Degradation of Alzheimer’s Beta-Amyloid Protein by Human Cathepsin D. NeuroReport 1996, 7 (13), 2163–2166. 10.1097/00001756-199609020-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballatore C.; Lee V. M. Y.; Trojanowski J. Q. Tau-Mediated Neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8 (9), 663–672. 10.1038/nrn2194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M.; Morishima-Kawashima M.; Takio K.; Suzuki M.; Titani K.; Ihara Y. Protein Sequence and Mass Spectrometric Analyses of Tau in the Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267 (24), 17047–17054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solé-Domènech S.; Rojas A. V.; Maisuradze G. G.; Scheraga H. A.; Lobel P.; Maxfield F. R. Lysosomal Enzyme Tripeptidyl Peptidase 1 Destabilizes Fibrillar Aβ by Multiple Endoproteolytic Cleavages within the β-Sheet Domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018, 115, 1493–1498. 10.1073/pnas.1719808115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs S. M.; Raines R. T. Pathway for Polyarginine Entry into Mammalian Cells. Biochemistry 2004, 43 (9), 2438–2444. 10.1021/bi035933x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams-Cioaba M. A.; Krupa J. C.; Xu C.; Mort J. S.; Min J. Structural Basis for the Recognition and Cleavage of Histone H3 by Cathepsin L. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2 (1), 197. 10.1038/ncomms1204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T.; Matsuoka Y.; Shirasawa T. Biological Significance of Isoaspartate and Its Repair System. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28 (9), 1590–1596. 10.1248/bpb.28.1590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zirah S.; Kozin S. A.; Mazur A. K.; Blond A.; Cheminant M.; Ségalas-Milazzo I.; Debey P.; Rebuffat S. Structural Changes of Region 1–16 of the Alzheimer Disease Amyloid β-Peptide upon Zinc Binding and in Vitro Aging. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281 (4), 2151–2161. 10.1074/jbc.M504454200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon Y. A.; Sabbah G. M.; Julian R. R. Differences in α-Crystallin Isomerization Reveal the Activity of Protein Isoaspartyl Methyltransferase (PIMT) in the Nucleus and Cortex of Human Lenses. Exp. Eye Res. 2018, 171, 131–141. 10.1016/j.exer.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao G.; Bondarenko P. V. Identification and Quantification of Degradations in the Asp–Asp Motifs of a Recombinant Monoclonal Antibody. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2008, 47 (1), 23–30. 10.1016/j.jpba.2007.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehder D. S.; Chelius D.; McAuley A.; Dillon T. M.; Xiao G.; Crouse-Zeineddini J.; Vardanyan L.; Perico N.; Mukku V.; Brems D. N.; et al. Isomerization of a Single Aspartyl Residue of Anti-Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Immunoglobulin γ2 Antibody Highlights the Role Avidity Plays in Antibody Activity. Biochemistry 2008, 47 (8), 2518–2530. 10.1021/bi7018223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadakane Y.; Yamazaki T.; Nakagomi K.; Akizawa T.; Fujii N.; Tanimura T.; Kaneda M.; Hatanaka Y. Quantification of the Isomerization of Asp Residue in Recombinant Human ΑA-Crystallin by Reversed-Phase HPLC. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2003, 30 (6), 1825–1833. 10.1016/S0731-7085(02)00525-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson N. E.; Robinson A. B. Molecular Clocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98 (3), 944–949. 10.1073/pnas.98.3.944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fezoui Y.; Teplow D. B. Kinetic Studies of Amyloid β-Protein Fibril Assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277 (40), 36948–36954. 10.1074/jbc.M204168200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama B. H.; Savas J. N.; Park S. K.; Harris M. S.; Ingolia N. T.; Yates J. R.; Hetzer M. W. Identification of Long-Lived Proteins Reveals Exceptional Stability of Essential Cellular Structures. Cell 2013, 154 (5), 971–982. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Kimpe L.; van Haastert E. S.; Kaminari A.; Zwart R.; Rutjes H.; Hoozemans J. J. M.; Scheper W. Intracellular Accumulation of Aggregated Pyroglutamate Amyloid Beta: Convergence of Aging and Aβ Pathology at the Lysosome. Age (Omaha). 2013, 35 (3), 673–687. 10.1007/s11357-012-9403-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozin S. A.; Mitkevich V. A.; Makarov A. A. Amyloid-β Containing Isoaspartate 7 as Potential Biomarker and Drug Target in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mendeleev Commun. 2016, 26 (4), 269–275. 10.1016/j.mencom.2016.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu X.; Crick S. L.; Bu G.; Frieden C.; Pappu R. V.; Lee J.-M. Amyloid Seeds Formed by Cellular Uptake, Concentration, and Aggregation of the Amyloid-Beta Peptide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106 (48), 20324–20329. 10.1073/pnas.0911281106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozin S. A.; Cheglakov I. B.; Ovsepyan A. A.; Telegin G. B.; Tsvetkov P. O.; Lisitsa A. V.; Makarov A. A. Peripherally Applied Synthetic Peptide IsoAsp7-Aβ(1–42) Triggers Cerebral β-Amyloidosis. Neurotoxic. Res. 2013, 24 (3), 370–376. 10.1007/s12640-013-9399-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikova A. A.; Cheglakov I. B.; Kukharsky M. S.; Ovchinnikov R. K.; Kozin S. A.; Makarov A. A. Intracerebral Injection of Metal-Binding Domain of Aβ Comprising the Isomerized Asp7 Increases the Amyloid Burden in Transgenic Mice. Neurotoxic. Res. 2016, 29 (4), 551–557. 10.1007/s12640-016-9603-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petkova A. T.; Ishii Y.; Balbach J. J.; Antzutkin O. N.; Leapman R. D.; Delaglio F.; Tycko R. A Structural Model for Alzheimer’s -Amyloid Fibrils Based on Experimental Constraints from Solid State NMR. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99 (26), 16742–16747. 10.1073/pnas.262663499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawuenyega K. G.; Kasten T.; Sigurdson W.; Bateman R. J. Amyloid-beta Isoform Metabolism Quantitation by Stable Isotope-Labeled Kinetics. Anal. Biochem. 2013, 440, 56–62. 10.1016/j.ab.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mawuenyega K. G.; Sigurdson W.; Ovod V.; Munsell L.; Kasten T.; Morris J. C.; Yarasheski K. E.; Bateman R. J. Decreased Clearance of CNS -Amyloid in Alzheimer’s Disease. Science 2010, 330, 1774–1774. 10.1126/science.1197623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhrs T.; Ritter C.; Adrian M.; Riek-Loher D.; Bohrmann B.; Dobeli H.; Schubert D.; Riek R. 3D Structure of Alzheimer’s Amyloid- (1–42) Fibrils. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005, 102 (48), 17342–17347. 10.1073/pnas.0506723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dan A.; Takahashi M.; Masuda-Suzukake M.; Kametani F.; Nonaka T.; Kondo H.; Akiyama H.; Arai T.; Mann D. M.; Saito Y.; et al. Extensive Deamidation at Asparagine Residue 279 Accounts for Weak Immunoreactivity of Tau with RD4 Antibody in Alzheimer’s Disease Brain. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2013, 1 (1), 54. 10.1186/2051-5960-1-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe A.; Takio K.; Ihara Y. Deamidation and Isoaspartate Formation in Smeared Tau in Paired Helical Filaments. Unusual Properties of the Microtubule-Binding Domain of Tau. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274 (11), 7368–7378. 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompa P. Intrinsically Unstructured Proteins. BioEssays 2003, 25 (9), 847–855. 10.1002/bies.10324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.