Abstract

Synthetically derived peptide-based biomaterials are in many instances capable of mimicking the structure and function of their full-length endogenous counterparts. Combine this with the fact that short mimetic peptides are easier to produce when compared to full length proteins, show enhanced processability and ease of modification, and have the ability to be prepared under well-defined and controlled conditions; it becomes obvious why there has been a recent push to develop regenerative biomaterials from these molecules. There is increasing evidence that the incorporation of peptides within regenerative scaffolds can result in the generation of structural recognition motifs that can enhance cell attachment or induce cell signaling pathways, improving cell infiltration or promote a variety of other modulatory biochemical responses. By highlighting the current approaches in the design and application of short mimetic peptides, we hope to demonstrate their potential in soft-tissue healing while at the same time drawing attention to the advances made to date and the problems which need to be overcome to advance these materials to the clinic for applications in heart, skin, and cornea repair.

Keywords: peptides, biomaterials, tissue engineering, functional materials, synthetic polymers

Introduction

Bioinspired materials for tissue repair have been amongst the most exhaustively explored fields in biomaterials research, yet mimicry of native extra cellular matrix (ECM), remains one of the most challenging tasks in tissue engineering. Further, while remarkable progress in recombinant protein expression has been made, there remains a gap as these processes are still relatively expensive particularly for heteromeric proteins; thus limiting scientists to the use animal origin (e.g., extracted from tissues) proteins including collagen and elastin for engineering translatable biomaterials. This limitation has severely halted clinical translation of functional biomaterials to the clinic. It is well-known that proteins take on an important role in almost all biological processes. While they have well-defined roles in the structural integrity of cells, organs, and tissues; their roles in other processes such as cell motility, signal transduction, immunological response, and enzymatic reactions are much more dynamic (Ouzounis et al., 2003). As such, many of the important findings regarding wound healing and tissue repair have come through the study of protein-protein and protein-ligand interactions. One such finding is that molecules which present binding sites for proteins, typically associated with either disease or wound healing, are excellent targets for the development of therapeutic solutions (Webber et al., 2010b). Given recent advancements in both chemical peptide synthesis and the recombinant production of full length proteins and peptides, generating and studying the interactions of mimetic molecules has been greatly simplified. Whether it is the production of exact copies of full-length or fragments of proteins, the incorporation of non-coded amino acids, or modification of the peptide backbone to enhance its proteolytic stability or the inclusion of tethers for further functionalization; one can generally find a suitable method to produce the desired molecule. For these reasons peptides, which are the small building blocks of proteins, have rapidly emerged as a cost-effective alternative for developing functional materials for tissue repair.

While the design options are almost limitless, these mimics usually interact with their target through the presentation of a specific amino acid sequence, a functional structure, or a combination of both. In this review, we will focus on peptides structures prepared using solid-phase peptide synthesis (SPPS), which for most systems nowadays takes place in cyclically automated synthetic equipment where each amino acid of the peptide structure is sequentially incorporated. Readers interested in learning more on peptide synthesis using transgenic organisms are encouraged to seek out reviews on this specific topic (Structural Genomics et al., 2008).

SPPS was conceptualized in 1959 and first reported on in the early 1960's by the Nobel awardee Robert Bruce Merrifield, its popularity and mainstream adoption grew in the 1970's and 1980's as technological advances in peptide chemistry made the process more robust (Merrifield, 1963). The concept of extending a peptide chain through the α-Nitrogen of an amino acid (a.a.) by coupling it with the carboxyl terminal of the next sequential a.a. whose other functional groups are protected, truly revolutionized the way peptides chains were produced. These protecting groups serve to prevent both oxidations and unspecific reactions of the a.a. side chains (Isidro-Llobet et al., 2009). Decades of intense synthetic research have yielded a number of versatile protecting groups such as the archetypical Fluorenylmethyloxycarbonyl (Fmoc) group. Single a.a.'s bearing Fmoc group are readily available on the market (Sigma-Aldrich, 2019). Technological improvement in SPPS, such as the use of microwave reactors and advanced temperature control systems, has allowed for the synthesis of peptides containing hundreds of a.a.'s in improved yield and reaction time in comparison to room temperature and convectional heating methods (Bacsa et al., 2006; Loffredo et al., 2009; Pedersen et al., 2012; Thapa et al., 2014). These technological advances have also contributed to the expedited synthesis of so-called difficult peptide sequences. Difficult peptide sequences refer to peptide sequences that agglomerate forming insoluble products during synthesis or after removal of the protective groups, a process that results in reduced yields or deactivation of the peptide preventing further modifications (Tickler and Wade, 2007). In most instance these problems arise due to introduction of functionalities capable a participating in non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and dipole-dipole interactions (Paradis-Bas et al., 2016). Thus, when designing peptides for SPPS, both the individual a.a. and the resulting coupling products (on the resin) should be screened for the potential formation of self-assembled structures, side reactions, and tendency to fold onto the resin. The following parameters have been demonstrated to aid in the synthesis of difficult peptide sequences: (i) high temperatures (e.g., 95°C for microwave-assisted synthesis), (ii) presence of salt or detergents for improving solubility, (iii) protecting groups at the amide group to avoid potential hydrogen-bond interactions, (iv) incorporation of amino acids with unreactive side chains to prevent undesired interactions, and (v) glycosylation or pegylation to improve peptide solubility.

Bioactive Peptide Sequence Mimics

Structural mimics developed using peptide sequences are in fact epitopes of bioactive sites, where in many instances the recognition site of the mimic is defined by both the amino acid sequence and three-dimensional conformation. In the following sections, we will discuss a number of bioactive short peptide sequences that have been identified, synthesized, and/or incorporated into structures to impart some type of biological response which could be exploited in tissue engineering or the development of regenerative biomaterials. The peptide sequences which will be discussed correspond to a representative set of examples, which we believe fall into one of the following three categories which we deemed most important in the development of functional biomaterials for the regeneration of heart, skin, and corneal tissue, namely, (i) pro-angiogenic sequences, (ii) anti-inflammatory, and (iii) pro-adherence sequences. Table 1 contains some representative peptide sequences that have been identified and used in the fabrication of functional materials. Scheme 1 depicts a representative summary for the concepts revised in this review. While we have limited this review to our expertise in soft tissue targets such as the heart, skin, and cornea, it is important to mention that peptide based materials have also found applications in the regeneration of hard-tissues such as bone and teeth, and that further information regarding these applications and recent advancements can be found in more specialized reviews (Pountos et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017).

Table 1.

Representative peptide sequences of potential interest in the development of functional biomaterials for tissue engineering.

| Peptide Sequence | Reference(s) | Main findings | Limitations | Portion of protein extracted | Receptors involved | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECM PROTEINS | ||||||

| Collagen | GFOGER | Knight et al., 2000; Wojtowicz et al., 2010 | Authors demonstrate the utility of coating grafts and improvement in bone growth with the peptide | Used an original sequence that included a GGYGG sequence that does not demonstrate utility in the self-assemble process and was added originally for radiolabeling (Reyes and Garcia, 2003) | Residues 502–507 of the αl(I)-CB3 fragment of type I collagen | α2β1 integrin receptor |

| DGEA | Mehta et al., 2015 | DGEA induced osteogenesis only when encapsulated with cells in a 3D network. The peptide does not provide any advantages when used in 2D cell culture | The authors do not provide details regarding the nature of peptide attachment to the polymer or whether it formed dimers through the carboxylic acids of the peptides | Residues 435–438 of the αl(I)-CB3 fragment of type I collagen | α2β1 integrin receptor | |

| FPGERGVEGPGP | Gelain et al., 2006; Bradshaw et al., 2014 | Authors demonstrated the ability of the peptide to induce migration of fibroblast in hydrogels | The peptide itself does not induce cell proliferation | – | – | |

| Laminin | IKVAV | Tashiro et al., 1989; Yamada et al., 2002 | Authors demonstrate that the peptide promotes cell attachment | The peptide sequence does not produce the same response as laminin | From the α-helix A chain segment of fragment E8 starts at amino acid position 1886 | – |

| YIGSR | Graf et al., 1987b; Yoshida et al., 1999; Boateng et al., 2005 | They demonstrated the ability of the peptide to attach cardiomyocytes onto a silica treated surface | The peptide sequence does not produce the same response as laminin | β1 chain amino acid residues 929–933 on the of Laminin-1 | – | |

| PDGSR | Kleinman et al., 1989; Huettner et al., 2018 | They demonstrated an improvement in the adhesion of tumoral cells in the presence of the peptide | They compared the peptide with a cyclic YIGSR peptide, but did not provide information if the cyclic PDGSR could be improved too | β1 chain amino acid residues 902–906 on the of Laminin-1 | – | |

| LRE | Hunter et al., 1991 | They assessed the active protein recognition of the peptide for neurite outgrowth and its correlation with salts in the solution | No direct assessment of antibody interaction to identify the specific receptor involved in the interaction | The A-subunit of laminin and synaptic basal lamina | – | |

| IKLLI | Tashiro et al., 1999 | They demonstrated attachment of cells is similar to that seen with IKVAV peptide. Also demonstrate that conformation of the peptide in a secondary structure affects adhesion | They did not use other highly charged positive peptides to compare the affinity of the heparin | α1 chain of laminin, between amino acids residues 2080–2095 | Integrin receptor α3β1 and a cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan | |

| Fibronectin | RGDS | (Ruoslahti, 1988; D'souza et al., 1991; Leahy et al., 1996) | One of the most used sequences for cell attachment | It is not the only site involved in cell attachment and recognition, other molecules could be also key, as an example proteoglycans. | Domain 10, from amino acid sequence 1493 to 1496 | More than 10 RGD dependent receptors, as an example: α3β1, α5β1, αvβ1, etc… |

| KQAGDV | Hautanen et al., 1989; Calvete et al., 1992 | They provide well-documented information of attachment sectors of the peptide to the receptor | The authors did not show inhibition studies with the peptides under study | γ chain in the fibronectin protein | αIIbβ3, αVβ3 | |

| REDV | Hubbell et al., 1991; Massia and Hubbell, 1992 | Demonstrate similarities between this peptide and RGD peptide, also selectivity for vessel forming endothelial cells | – | Within the spliced type III connecting segment (III CS) domain of human plasma fibronectin | α4β1 | |

| PHSRN | Feng and Mrksich, 2004 | Demonstrate that this fragment is also recognized by integrin receptor, competitive with RGD, but with less strength than RGD | – | Within the 9th type III domain | α5β1 | |

| REMODELING ENZYMES | ||||||

| Collagenase | GPQGIWGQ GPQGYIAGQ GPQGYILGQ | Nagase and Fields, 1996; Lutolf et al., 2003; Patterson and Hubbell, 2010 | Substrates containing the sequence are cleaved under the conditions tested and can induce release of specific molecules after proteolytic effects | The sequence is not specific for one type of enzyme | Sequence presented in position 775 of αI fibril of the collagen | GPQG↓ (↓ = Enzyme proteolytic effect) |

| Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) | CPENYFFWGGGG | Salinas and Anseth, 2008 | Demonstrate that biomaterials performance depends on the presence and dynamic concentration of the receptor in the hydrogel | In hydrogels, the enzyme degradation rate is fast for surface and slow for deeper cues | Cleaved by MMP-13 | CPEN↓ |

| APGL | West and Hubbell, 1999 | The sequence is selective for collagenase, but not for plasmin. | The authors do not provide proof the sequence could be cleaved through cell culture | Cleaved by collagenase | APG↓ | |

| LGPA | Patel et al., 2005 | The sequence is attached to a photo responsive material, that can control hydrogel formation with light and degradation by the peptide sequence. | The sequence by itself does not induce cell attachment and survival in the long term | Collagenase-sensitive degradable sequence | – | |

| GTAGLIGQ | Jun et al., 2005; Kim et al., 2009 | The sequence is used to release other drugs, in this case cis-platin | The sequence is attached with an RGD sequence. This could affect enzymatic degradation rates (not evaluated without the RGD sequence) | MMP-2 specific cleavage | GTAG↓ | |

| Plasmin | YKNRD | Pratt et al., 2004; Raeber et al., 2005 | The sequence induces bone regeneration and cell attachment. Selective to plasmin | – | Plasmin sensitive sequence that is enhanced at the carboxylic side of the lysine amino acid | YK↓ |

| ELAPLRAP FPLRMRDW EGTKKGHK KKGHKLHL HPVGLLAR | Patterson and Hubbell, 2011; Singh et al., 2012 | Depending on the sequence selected, the hydrogel degradation rate can be tuned with respect to its sensibility toward plasmin | Sequences have shared activity with other MMPs | – | ELAP↓ FPLR↓ EGTKKGHK↓ KKGHK↓ HPVG↓ | |

| TARGET PROTEIN/RECEPTOR | ||||||

| Vascular endothelial growth factor | KLTWQELYQLKYKGI | Diana et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012 | Demonstrated ability to promote angiogenesis | VEGF mimetic peptide agonist from amino acid sequence 87 to 100 | VEGF receptor 1-D2 | |

| LRK2LGKA | Webber et al., 2010a | Cationic amino acids are used to bind heparin binding factors to a self-assembling sequence | The attachment of the heparin binding is ionic and is not compared with covalent bonding, which could increase long term release of the factors | – | – | |

| Glycosaminoglycans | PNDRRR | Gilmore et al., 2013 | Heparin binding through the sequence RRR (or KKK) is used for increasing angiogenic properties | The attachment of heparin is ionic, thus reducing the long-term stability of the aminoglycan | – | – |

| SUPRAMOLECULAR STRUCTURE | ||||||

| Vesicle/Micelle | G4D2 G6D2 G8D2 G10D2 |

Santoso et al., 2002 | Length of the peptide glycine chain, dictated the formation of nanovesicles or nanotubes | Lack of homogeneous structures | – | – |

| V6K2 L6K2 A6K V6H V6K H2V6 KV6 |

Von Maltzahn et al., 2003 | The peptides have the ability to self-assemble in different macro-structures. One of the main advantages, is that they dissemble above their pI | Lack of homogeneous structures | – | – | |

| Fiber | (PKG)4(POG)4(DOG)4 | O'leary et al., 2011 | Stable formation of a hydrogel that has similar characteristics to collagen | Lack of D periodicity | – | – |

| PRG)4(POG)4(EOG)4 | Rele et al., 2007 | Stable formation of a hydrogel that has similar characteristics to collagen | Lack of strength when compared to collagen bundles | – | – | |

| (RADA)4 (RARADADA)2 (FKFE)2 (KLDL)3 | Sieminski et al., 2008 | Fibers are formed by β-sheet interactions. RADA incorporation leads to better attachment of cells | Ability to control fiber dimensions could improve comparison of the system | – | – | |

| MULTI-DOMAIN PEPTIDES | ||||||

| Double function peptide | E2(SL)6E2-G-RGDS | Bakota et al., 2011 | Left sequence used for self-assembly as a β-sheet [E2(SL)6E2]. Right sequence to be sensed as fibronectin receptor [RGDS] |

– | – | – |

| C12H25O-YGAAKKAAKAAKKAAKAA | Chu-Kung et al., 2004 | Left sequence: lipid portion to interact with lipidic membranes [C12H25O]. Right sequence: cationic sequence to facilitate interaction with bacteria wall as an anti-microbial peptide [YGAAKKAAKAAKKAAKAA] | Lipid attachment could result in toxicity toward eukaryotic cells | – | – | |

| Quadruple function peptide | KS(LS)2-LRG-(SL)3KG- KLTWQELYQLKYKGI | Kumar et al., 2015 | Left sequence [KS(LS)2] used for self-assembly as a β-sheet Center left sequence (LRG) MMP-2 substrate. Center Right sequence [(SL)3KG]: used for self-assembly as a β-sheet Right sequence [KLTWQELYQLKYKGI] is a vascular endothelial growth factor |

– | – | – |

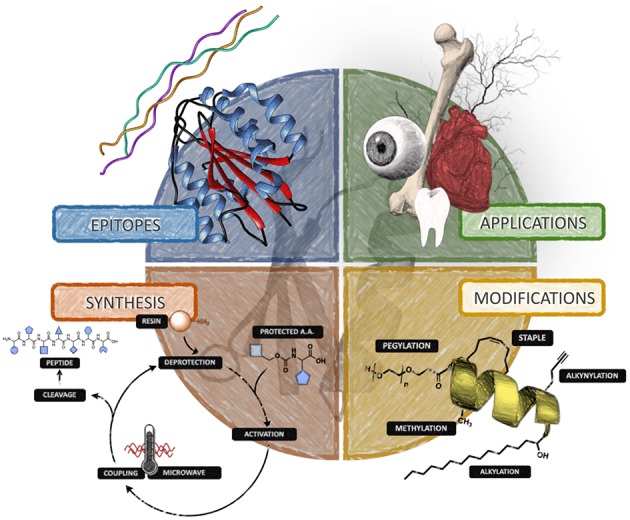

Scheme 1.

Diagram summarizing the main concepts revised in this review for the use of peptide-based materials in tissue and organ repair.

Pro-Angiogenic Sequences

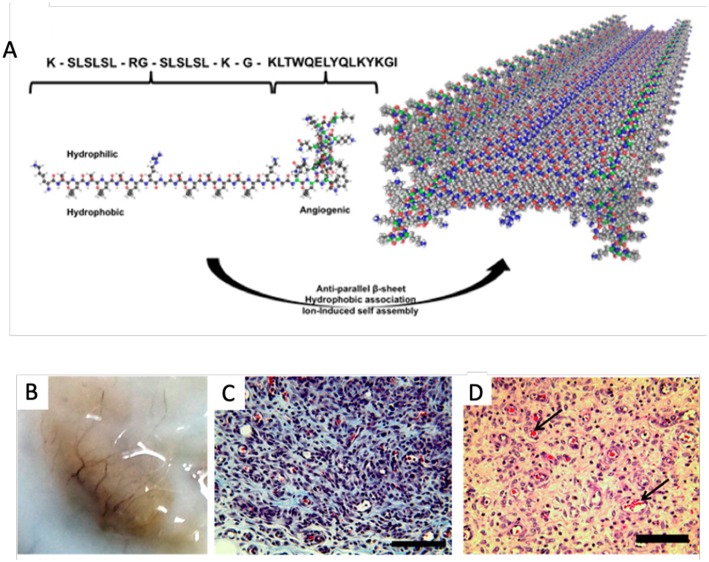

Angiogenesis is a process which involves the proliferation and migration of endothelial cells as well as the concurrent remodeling of the extracellular matrix, which drives the development of new blood vessels from exiting vasculature (Potente et al., 2011). The principal regulator of angiogenesis in both physiological and diseased state is vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). VEGF and its many isoforms induce physiological responses through interaction with three well-described tyrosine kinase receptors (Simons et al., 2016). To date the most promising pro-angiogenic peptides are VEGF mimics. Of the available VEGF-mimics the most well-characterized is peptide QK, which was designed to imitate the binding of VEGF to its receptor through a N-terminal α-helix mimic comprised of the amino acid sequence, KLTWQELYQLKYKGI (Andrea et al., 2005). The angiogenic properties of peptide QK have been demonstrated both in vitro and in vivo, with evident endothelial cell activation and increases in VEGF related cellular functions such as chemotaxis, invasion, sprouting of new capillaries, and enhanced organization (Andrea et al., 2005; Finetti et al., 2012). A self-assembling β-sheet peptide hydrogel encompassing the QK sequence has also shown to promote cell infiltration and vascularization when injected subcutaneously in a rat model as shown in Figure 1 (Kumar et al., 2015).

Figure 1.

Self-assembling angiogenic peptide hydrogel. (A) Schematic illustrating the structure of the the multi-domain peptide comprising the VEGF mimic QK sequence and its assembly into a β-sheet. (B) Visible macroscale vessels apparent within the explant materal 7 days post injection. (C) Massons's Trichrome and (D) HandE staining showing infiltration of scaffolds and presence of blood vessels with red blood cells [arrows] at 1 week post injection; scale bar 100 μm. Adapted with permission from Kumar et al. (2015). Copyright 2015 American Chemical Society.

It may also be interesting to explore the ability of these VEGF mimics to bind heparin as there is much literature regarding the propensity of different isoforms of VEGF to bind heparin and the necessity of this binding to promote endothelial cell growth and proliferation (Ferrara et al., 2003). Furthermore the incorporation of VEGF within oxygen generating or hypoxia inducing hydrogels or matrices could potentially influence hypoxia inducible factors which are important in the expression and function of VEGF (Krock et al., 2011).

Other peptides which have shown promise in regulating angiogenesis are targets of growth factor receptors which typically work in conjunction with VEGF. For example, fibroblast growth factor as well as neural cell adhesion molecules (NCAMs), which have been shown to bind to fibroblast growth factor receptors can also promote angiogenesis (Elfenbein et al., 2007). Peptide mimics of both FGF2 and NCAM have been prepared synthetically and while they may act in either a canonical or non-canonical fashion, there is strong evidence that they influence angiogenesis (Elfenbein et al., 2007; Rubert Pérez et al., 2017). There are also a number of angiopoietin-1 mimics which have shown promise in regulating angiogenesis via interaction with a tyrosine kinase receptor (Tie2) which is found primarily on vascular endothelial cells and hematopoietic cells (Cho et al., 2004; Miklas et al., 2013). Other peptides one may want to incorporate within materials destined for vascularized tissue are those capable of mimicking transforming growth factors (TGFα and TGFβ) (Ferrari et al., 2009), tumor necrosis factor (TNFα) (Sainson et al., 2008), Angiogenin (Hu et al., 1997), Interleukin 8 (IL8) (Li et al., 2008), or hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) (Xin et al., 2001) as these mitogens and chemokines have been demonstrated to promote angiogenesis through control of endothelial cell growth and/or interaction with VEGF mediated pathways. Considering the effect these factors can have on the expression and efficacy of VEGF and that they are typically targets of surface bound receptors, their incorporation into soft materials may need to be done in such a way that their interaction with the target receptor is not hindered, which may limit covalent attachment within the matrix.

Anti-inflammatory Sequences

In the design of scaffolds and biomaterials for tissue engineering and regeneration, the host immune system is one of the largest barriers to overcome. However, this does not mean that immune response is to be completely avoided; in fact in order to maximize the therapeutic efficacy of implants it is necessary for them to modulate the resulting immune response. Furthermore, inflammation promotes angiogenesis and the formation of new blood vessels can lead to further inflammation. For this reason it is important to understand that inflammation is a complex process which eventually brings homeostasis to the effected tissue through the promotion of cell infiltration, proliferation, and subsequent polarization. While there are many players involved in immune response, macrophages are considered amongst the most important and as such the current section will focus on the ways peptide mimetics can or could be used in their regulation. Macrophages are dynamic cells whose phenotype is subject to polarization from the extracellular environment as well as active signaling molecules (Taraballi et al., 2018). Classically, when discussing the phenotype of macrophages, there is said to be two distinct subsets (i) M1 (pro-inflammatory) and (ii) M2 (anti-inflammatory/pro healing). However, this is a highly simplified view considering the polarization toward either phenotype is actually more of a continuum with the difference between M1 and M2 not being discrete (Martinez and Gordon, 2014). Through the design of short peptides that interact with immunogenic receptors of M2 macrophages like TGF-bR, IL-4R, IL-6R, IL-10R, and MCSFR it is possible to modulate the immunological response associated with tissue damage and repair as well as the introduction of foreign materials (Taraballi et al., 2018). Upon acting on the expression of both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines such IL 6 and TNF-α as well as the production of reactive oxygen species one could develop materials which can reduce inflammation, recruit cells via chemotaxis, and ultimately improve wound healing (Boersema et al., 2016). While most inflammation related to foreign material response can be eliminated or reduced through the use of recombinant or autologous proteins or protein/peptide mimics, it may be possible to include small peptide mimetics to activate and polarize macrophages toward a type 2 phenotype. However, due to the complexity of the activation process it is difficult to pin down a sequence or multiple sequences which could bring about the desired response; and for this reason there are not many sequences known to modulate immune response in ways which are beneficial to tissue regeneration and the design of regenerative biomaterials. There are also a number of sequences defined as being anti-bacterial and as such anti-inflammatory (Rotem and Mor, 2009). One class of peptides which have shown promise in modulating immune responses are innate defense regulator (IDR) peptides (Niyonsaba et al., 2013). These cationic antimicrobial peptides are synthetic cationic analogs of naturally occurring host defense peptides or proteins (HDP). They are relatively short peptides (10–50 a.a.), with no specific consensus sequence. While they have some ability to directly kill microbes, they are also capable of modulating immune and inflammatory responses. For example, they are capable of influencing chemotaxis, stimulating the production of chemokines, directing macrophage polarization, and modulating the expression of neutrophil adhesion and activation markers (Niyonsaba et al., 2013). IDR-1018, is a peptide of this class consisting of 12 a.a. (VRLIVAVRIWRR-NH2) and has been shown to enhance the anti-inflammatory response while maintaining key pro-inflammatory processes important in fighting off infection, an ability made possible by the fact that this peptide drives macrophage polarization toward an intermediate M1-M2 state (Pena et al., 2013). Other members of this class of peptide include IDR-HH2 and IDR-1002, both of which have similar immunomodulatory abilities. Antimicrobial peptides LL-37 and SET-M33 have also been shown to mediate inflammation through the reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines, enzymes, and transduction factors (Kahlenberg and Kaplan, 2013; Brunetti et al., 2016).

One of the ways in which macrophage activation controls the immune response is through the expression/production of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). MMPs are a family of proteolytic enzymes which themselves are capable of modulating immune responses through the regulation of cytokines and chemokines. There are a handful of different types of MMPs all of which are capable of degrading extracellular matrix proteins and activating bioactive molecules via proteolytic cleavage or other modifications. Through the inclusion of MMP binding and cleavage sequences within the peptides that comprise a material it is possible to increase its local concentration while enhancing the proteolytic degradation of the material which can allow for its replacement with endogenous matrix and the release of small peptide fragments which can in turn modulate other cellular responses. An example, of an MMP epitope found in Type I collagen is the amino acid sequence GPQGIAG (Turk et al., 2001). The presence of such a sequence in collagen-PEG conjugates has been shown to enhance proteolytic degradation by both MMP-1 and MMP-2 (Turk et al., 2001; Patterson and Hubbell, 2010).

Pro-Adherence Sequences

One of the key requirements of regenerative biomaterials is that they support the in-growth, attachment, and proliferation of endogenous cells. One way to ensure that cells attach to a material is to modify the material in such a way to incorporate a peptide that displays a specific binding sequence. One of the most ubiquitous and simple binding sequences are the RGD and RGDS motifs, which are prominent in adhesion proteins like fibronectin and fibrinogen but also structural proteins such as collagen and laminin (Yamada, 1991). They act as an anchoring site for a number of different α and β integrin binding receptors. The RGDS sequence has also been shown to inhibit platelet aggregation and as such displays some anti-thrombolytic activity (Samanen et al., 1991). As a polar opposite to RGD, KGD sequences have been found to disrupt cell attachment by inhibiting integrin binding (Scarborough et al., 1991). Another pro-adherence sequence derived from the adhesion protein fibronectin is PHSRN. PHSRN like RGD is an integrin cell adhesion motif, however it differs from many of the other linear cell attachment sequences in that the spatial organization of this sequence must mimic that found in fibronectin for it to be beneficial (Mardilovich et al., 2006). Also coming from fibronectin are the REDV, LDV, and KQAGDV integrin binding motifs, which have been shown to help in the anchoring of human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) as wells as promote smooth muscle cell adhesion (Hubbell et al., 1991; Mould et al., 1991; Shin et al., 2003). Laminin derived sequences such as IKVAV and YIGSR are also important as integrin binding ligands. While YIGSR also displays some anti-cancer properties, both YIGSR and IKVAV sequences have been shown to stimulate neurite growth and have found use in the design of several therapeutic materials (Graf et al., 1987a; Tashiro et al., 1989). Structural proteins such as collagen also display some cell adhesion sequences, with the most well-described ones being derived from collagen type I and IV. As is the case with the previously mentioned pro-adherence sequences, the short DGEA, GFOGER (where O is hydroxyproline), and GFPGER sequences play a key role in integrin recognition and as such have been incorporated in a number of tissue repair strategies (Staatz et al., 1991; Knight et al., 2000).

Also important to mention is that some peptide sequences can self-assemble due to intra or inter molecular interactions to form supramolecular structures driven by Van-Der-Waals, electrostatic, hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic, and π-π stacking (see Table 1). Different kinds of self-assembly structures can be generated from the peptides depending on their structure at the nanometer scale. Peptides can assemble as (i) α-coil, (ii) β-sheet, (iii) β-hairpins, and (iv) poly-proline helix. Depending on the supramolecular structure of the peptide assembly a variety of configurations can be achieved, which include vesicles, rods, or fibers. In addition, advancements in peptide synthesis have allowed for the fabrication of peptides bearing more than one property in their sequences. Thus, for example, in Table 2, some peptide sequences contain a self-assembly portion and a second portion which acts as a bio-recognition sequences for receptors, or a lipid-like portion for vesicle formation (see Table 1).

Table 2.

Peptide-containing biomaterials as therapeutic agents for tissue and organ repair of cornea, skin, and heart tissues.

| Peptide sequence | Tissue/Organ | Functional effect | Specific cell receptor | Delivery System | In vitro or In vivo test | Main findings | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CG(PKG)4(POG)4(DOG)4, with O being hydroxyproline | Cornea | Corneal implant promoting cell and nerve regeneration | – | Self-assembly | Collagenase Cell proliferation In vivo biocompatibility by subcutaneous implantation Corneal implantation (pigs) In vitro toxicology, biocompatibility, metabolic activity, live/dead, DSC | Corneal implant was compatible for transplantation showing cell and nerve regeneration | Islam et al., 2016 Jangamreddy et al., 2018 |

| YIGSR | Promotes epithelial cell growth and neurite extension | Epithelial cells | Hydrogel | In vitro characterization (cell layers and thickness, nerve density, IR spectroscopy), immunohistochemistry, regeneration, corneal touch sensitivity | Overall corneal regeneration including nerve regeneration | Li et al., 2003 | |

| Q11 (Ac- QQKFQFQFEQQ-Am) | Skin | Wound healing in strong immune response | dermal | Wound closure, type of cell recruitment in mice with strong immune response | Immunogenic peptides do not delay healing, even in mice with heightened immune response | Vigneswaran et al., 2016 | |

| KGF–ELP | Chronic wound healing | KGF receptor | Fibrin hydrogel vehicle | Characterization (DLS, TEM), cell proliferation, full thickness wound healing | Enhanced granulation and reepithelialization | Koria et al., 2011 | |

| Pexiganan Acetate GIGKFLKKAKKFGKAFVKILKK | Antibacterial properties | Disturbs membrane permeability | Topical | MIC against gram-negative and positive bacteria, anaerobes, in vivo antibacterial activity, short term tolerability tests | Indication: infected diabetic foot ulcers, similar efficacy to ofloxacin | Lamb and Wiseman, 1998 | |

| HBPA (palmitoyl–AAAAGGGLRKKLGKA) | Increased angiogenesis | VEGF and FGF-2 | Gel administered subcutaneously | Subcutaneous implantation, histological and morphological analysis of wound site, skinfold chamber model, in vivo microscopy, microcirculatory analysis | Increased angiogenesis, including de novo angiogenesis | Ghanaati et al., 2009 | |

| RADA16-I, [COCH3]-RADARADARADARADA-[CONH2] with EGF | Improved would healing | Keratinocytes and fibroblasts | Topical | In vitro human skin equivalent wound healing model, proliferation assay, apoptosis assay, Histological analysis | Epithelialization and wound healing are accelerated with EGF and RADA-16, as opposed to RADA-16 alone | Schneider et al., 2008 | |

| RADA16-GG-RGDS and RADA16-GG-FPGERGVEGPGP | Improved cell migration | Keratinocytes and fibroblasts | Hydrogel | In vivo analysis, including SEM of cells with SAP, cell proliferation, cell migration | Improved cellular migration | Bradshaw et al., 2014 | |

| (RADA)4 | Heart | Self-assembling | Nanofiber | Rat MI model | Improved Angiogenesis | Dubois et al., 2008 | |

| (RADA)4-LRKKLGKA | Self-assembling heparin-binding sequence | Nanofiber with VEGF | Rat MI model | Improved Angiogenesis Improved Left ventricle contraction Decrease Fibrosis and Left ventricle remodeling | Guo et al., 2012 | ||

| (RARADADA)2 | Self-assembling | IFG-1 bound nanofiber with CMs | Rat MI model | Improved Cell survival Improved Left ventricle contraction Decrease cardiac remodeling | Davis et al., 2006 | ||

| Self-assembling | Dissolved in solution with MNCs | Porcine MI model | Improved Angiogenesis, Cell survival, and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced ventricular remodeling | Lin et al., 2010, 2015 | |||

| Self-assembling | Nanofiber with VEGF | Rat MI model Porcine MI model | Improved Angiogenesis Left ventricle contraction. Reduced ventricular remodeling | Lin et al., 2012 | |||

| Self-assembling | PDGF bound nanofiber | Rat MI model | Improved Angiogenesis, Cell survival and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced ventricular remodeling | Hsieh et al., 2006a,b | |||

| Self-assembling | Dissolved in solution with ADSCs | Rat MI model | Improved Angiogenesis, Cell survival and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced ventricular remodeling | Kim et al., 2017 | |||

| Self-assembling | SDF-1 bound nanofiber | Rat MI model | Increases EPC recruitment, Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction | Segers et al., 2007 | |||

| Self-assembling heparin-binding sequence | Nanofiber with MSCs | Rat MI model | Increases cell survival, Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction | Cui et al., 2010 | |||

| (RARADADA)2-CDDYYYGFGCNKFCRPR(Notch ligand Jagged-1) | Self-assembling Cell adhesion sequence | Hydrogel with CACs | Rat MI model | Increases cell survival and Left ventricle contraction. Decreases ventricular remodeling | Boopathy et al., 2014 | ||

| AAAAGGGEIKVAV(peptide amphiphile)-YIGSR AAAAGGGEIKVAV(peptide amphiphile)-KKKKK | Self-assembling EC adhesive ligand NO producing donor | Nanofiber | N/A | Increases EPC viability and differentiation | Andukuri et al., 2013 | ||

| Heparin-AAAAGGGEIKVAV(peptide amphiphile) | Self-assembling | VEGF/bFGF bound nanofiber | Mouse MI model | Increases Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction | Webber et al., 2010a | ||

| VVAGEGDKS | Glycosaminoglycan mimetic | Nanofiber | Rat MI model | Increases Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction | Rufaihah et al., 2017 | ||

| AcSDKP(Thymosinβ4) | Angiogenic | Collagen-chitosan hydrogel | Rat MI model | Increases Angiogenesis and cell survival. Reduces ventricular remodeling | Chiu et al., 2012 | ||

| KAFDITYVRLKF-AcSDKP(Thymosinβ4) | Proangiogenic Anti-inflammatory | Collagen hydrogel | Mouse subcutaneous implant | Increases Angiogenesis. Reduces Inflammation | Zachman et al., 2013 | ||

| RGD | Cell adhesion sequence | Alginate microsphere with MSCs | Rat MI model | Improved Angiogenesis, Cell survival, and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced ventricular remodeling | Yu et al., 2010 | ||

| RGD | Cell adhesion sequence | Alginate scaffold | Rat MI model | Improved Angiogenesis and Left ventricle function | Yu et al., 2009 | ||

| RGDfK | Cell adhesion sequence | Alginate scaffold with MSCs | Rat MI model | Improved Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction | Sondermeijer et al., 2017 | ||

| RGDS-AAAAGGGEIKVAV(peptide amphiphile) | Cell adhesion sequence Self-assembling | Subcutaneous injection with MNCs | Mouse | Improved Cell survival | Webber et al., 2010c | ||

| RGDSP-(RADA)4 | Cell adhesion sequence Self-assembling | Dissolved in solution with MCSCs | Rat MI model | Improved Cell survival and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced fibrosis | Guo et al., 2010 | ||

| GGGGRGDY | Cell adhesion sequence | Alginate scaffold | N/A | Improved NRVM contractility and viability | Shachar et al., 2011 | ||

| GRGDS | Cell adhesion sequence | Collagen hydrogel | N/A | Improved NRVM contractility and viability | Schussler et al., 2009 | ||

| QHREDGS | Cell adhesion sequence | Collagen-chitosan scaffold | N/A | Improved EC survival and tube formation | Miklas et al., 2013 | ||

| Cell adhesion sequence | Collagen-chitosan scaffold | N/A | Improved NRVM survival | Reis et al., 2012 | |||

| Cell adhesion sequence | Azidobenzoic acid-chitosan scaffold | N/A | Improved NRVM survival | Rask et al., 2010 | |||

| Cell adhesion sequence | Collagen-chitosan hydrogel | Rat MI model | Improved Cell survival and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced ventricular remodeling | Reis et al., 2015 | |||

| WKYMVm | Formyl peptide receptor 2 agonist | Dissolved in solution | Mouse MI model | Improved Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced fibrosis | Heo et al., 2017 | ||

| KPVSLSYRCPCRFFESHPPLKWIQEYLEKALN | SDF-1a analog | Dissolved in solution | Mouse MI model | Improved Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction | Hiesinger et al., 2011 | ||

| YPHIDSLGHWRR | 78kDa Glucose-regulated protein receptor's ligand | Chitosan hydrogel | Rat MI model | Improved, Cell survival, Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced ventricular remodeling | Shu et al., 2015 | ||

| MHSPGAD | Stem cell recruitment | Collagen hydrogel | Mouse MI model | Improved Angiogenesis and Left ventricle contraction. Reduced fibrosis and ventricular remodeling | Zhang et al., 2019 |

Applications of Peptides in Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials

The modification of materials through bioengineering techniques has given rise to a promising route for the generation of synthetic and hybrid materials which not only display biological function and compatibility, but are also capable of controlling cellular microenvironment. The field of tissue engineering is continuously evolving and improving, changing the way scientists and engineers treat damaged tissues (Chen and Liu, 2016). One of the most important aspects of tissue engineering is the design of materials that are biocompatible and capable of interacting with cells and the host environment to promote healing (Girotti et al., 2004; Chen and Liu, 2016). To this end, a number of matrices have been developed for applications that range from tissue replacement and repair to drug delivery (Girotti et al., 2004; Chow et al., 2011; Chen and Liu, 2016). Peptides are increasingly being incorporated or self-assembled into matrices to enhance cell signaling and the bioactivity, improve drug delivery, and provide antibacterial properties amongst many other applications (Girotti et al., 2004; Chow et al., 2011; Miotto et al., 2015). In this section, we will briefly review some representative examples of peptide-based approaches for regenerative therapies in heart, skin, and cornea (Girotti et al., 2004; Chattopadhyay and Raines, 2014; Rodríguez-Cabello et al., 2018). In selecting literature, we have limited our search to articles that contain in vivo assessments for the materials, see Table 2.

Peptides Sequences in Cornea and Skin Therapeutics

Collagen- and elastin-like peptides are commonly used peptides in skin and cornea tissue repair (Chattopadhyay and Raines, 2014; Rodríguez-Cabello et al., 2018). Collagen is the most abundant protein in the extracellular matrix and commonly used in biomaterials (Chattopadhyay and Raines, 2014; Tanrikulu et al., 2016). Full-length human collagen is complicated to synthesize, as it requires significant post-transcriptional modifications and it is not soluble in most buffers, making it difficult to study (Koide, 2005; Tanrikulu et al., 2016). However, short collagen-mimetic peptide sequences are being used to mimic full-length collagen, by incorporating important peptide sequences at a fraction of the length (Tanrikulu et al., 2016). These collagen mimetic sequences typically require a glycine residue present in every third position and contain many proline and hydroxyproline repeats (Chattopadhyay and Raines, 2014; Tanrikulu et al., 2016). These sequences form left-handed polyProline II helix chains, which then self-assemble in groups of three to produce a right-handed superhelix (Fields, 2010; Chattopadhyay and Raines, 2014; Tanrikulu et al., 2016). The peptide sequence (PKG)4(POG)4(DOG)4 has also been designed to self-assemble as a collagen mimetic peptide (O'leary et al., 2011). The N-terminus of this self-assembling peptide was then modified to contain a glycine spacer and terminal cysteine (CG-linker). The addition of a terminal cysteine allowed for the attachment of the peptide to an 8-arm PEG polymer via maleimide chemistry. The application of this new collagen mimetic peptide-hybrid polymer as solid implant resulted in transparent and well-shaped corneas with the deposition of new collagen and the infiltration of stromal cells after 12 months of implantation in porcine model (Islam et al., 2016). An improvement in the formulation was achieved through the addition of the molecule 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC), which has been shown to reduce inflammation and improve hydrogel bio-compatibility (Jangamreddy et al., 2018). In terms of recovery after 12 months, the same epithelium, stromal and nerve recovery was found between the improved formulation and a cornea model graft made from Type III Recombinant Human Collagen.

The laminin adhesion pentapeptide motif, YIGSR, has also been grafted onto biosynthetic corneas comprised of hydrated collagen and N-isopropylacrylamide copolymers, and tested in Yucatan micropigs (Li et al., 2003). The materials were 5.5 mm in diameter and 200 μm think and implanted via lamellar keratoplasty. After 6 weeks, the implants were able to demonstrate successful regeneration of the host corneal epithelium, stroma, and nerves. In contrast, no nerve regeneration was observed in control eyes which received allografts, during the experimental period (Li et al., 2003).

Peptides have also been functionalized in ways which allow them to be tethered to nanoparticles to generate biomimetic platforms, alter physical properties and cellular interactions, or allow for their incorporation into fibrils or hydrogels for various application (Chattopadhyay and Raines, 2014; Chen and Liu, 2016; Rodríguez-Cabello et al., 2018).

Elastin-like peptides (ELPs) have shown to be extremely useful in tissue engineering, due to their elastic properties, which help them mimic the physical properties of a number of different tissues and organs (Rodríguez-Cabello et al., 2018). While the abundance of elastin in the human body is low (2–4% of dry weight of skin) it plays an important part in the mechanical strength and support of skin and has also been demonstrated to be involved in cell signaling (Rodríguez-Cabello et al., 2018). ELPs are typically derived from the pentapeptide sequence of elastin (VPGXG), where X can be any amino acid (Urry et al., 1981; Urry, 1988; Girotti et al., 2004; Rodríguez-Cabello et al., 2018). This sequence maintains its elastomeric properties when it is crosslinked (Urry et al., 1981; Girotti et al., 2004). It has been suggested that the human body cannot discern ELPs from endogenous elastin and ELP matrices show similar mechanical properties as endogenous elastin, which allows the body to use the scaffold to rebuild the natural ECM (Girotti et al., 2004).

Peptides such as Q11 and RADA-16, have also been incorporated into biomaterials and used in tissue engineering (Vigneswaran et al., 2016). RADA-16 with EGF has shown to improve cell mobility in the skin, which can result in improved wound healing, especially in non-healing wounds (Schneider et al., 2008; Bradshaw et al., 2014). Lastly, wound healing antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have also been used in applications of non-healing infected wounds, such as diabetic foot ulcers. These peptides prevent infection, reduce inflammatory response, and promote cell proliferation and migration (Mangoni et al., 2016; Gomes et al., 2017). AMPs have a wide range of amino acid sequences, however they are generally composed of an amphipathic structure, which contains a high prevalence of basic residues (Mangoni et al., 2016). In human skin, AMPs are synthesized and stored by keratinocytes in the granular layer (Mangoni et al., 2016).

Applications in the Heart

Myocardial infarction (MI) is a leading cause of death globally, and can ultimately lead to heart failure (World Health Organization, 2017). In order to be effective peptide-based therapeutics need to be resistant to local proteases and retained long enough to exert the desired effect in the myocardium. The employed self-assembling peptides are typically comprised of alternating hydrophilic and hydrophobic amino acids (Zhang, 2003), which on exposure to physiological osmolality and pH, rapidly assemble into nanofibrous structures that can be injected into the myocardium to form 3D microenvironments (Zhang et al., 1993; Davis et al., 2005). Such therapy has shown promise in the treatment of infarcted myocardium. The RADA class of ionic self-complementary peptide is one of the first generations of self-assembling peptide and the most intensively studied for applications in MI, as it is commercially available (Dubois et al., 2008). When delivered with platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), the self-assembling nanofibers fabricated from the RADA sequence decreased infarct size and improved cardiac function in a rat MI model (Hsieh et al., 2006a,b). Despite cardiac-specific overexpression of several members of the PDGF family and the fact that it has been reported to induce fibroblast overgrowth and cardiac fibrosis (Ponten et al., 2005), this study demonstrated that PDGF conjugated to the self-assembling nanofibers actually reduced cardiac fibrosis, suggesting a well-controlled release of PDGF. When combined with VEGF, the RADA-derived nanofibrous hydrogels were also shown to improve angiogenesis and cardiac performance in rat and porcine MI models (Lin et al., 2012). The RADA sequence has also been used in combination with cell therapies. For example, injection of a RADA derived hydrogel into a porcine MI model with bone marrow mononuclear cells (MNCs) increased cell retention about 8-fold and improve the cardiac function at 1 month post-MI (Lin et al., 2010, 2015). Similarly, human adipose-derived stromal cells (ADSCs) with fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-immobilized within a RADA hydrogel were injected into a rat MI heart, and demonstrated to promote angiogenesis and improve cardiac contraction (Kim et al., 2017). Likewise, tethering of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) to self-assembling peptides increased survival of transplanted neonatal rat cardiomyocytes in a rat MI model (Davis et al., 2006). Cell mediated therapies are also enhanced by well-controlled release of some types of chemokines. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) was combined to RADA nanofibers, and was demonstrated to improve cardiac function via recruitment of endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) (Segers et al., 2007). Of note, is the fact that the SDF-1 has also been attached to a 6-amino acid sequence susceptible to MMP-2 cleavage to achieve “smart release” of the chemokine at the site of infarction, albeit showing no additional effect in vivo (Segers et al., 2007).

Self-assembled peptide amphiphiles have emerged as versatile biomaterials (Beniash et al., 2005). The amphiphilicity of the peptides allows for self-assembly in aqueous media, eliminating the necessity of organic solvents and as such broadens their applicability. To improve cell retention, a peptide amphiphile scaffold was combined with RGDS, and delivered with MNCs subcutaneously (Webber et al., 2010c). The incorporation of RGDS improved retention and proliferation of the cells in vivo, along with enhancing endothelial marker expression in vitro. Likewise, heparin-binding peptide amphiphile (HBPA) was developed and assessed as a biomaterial for MI therapies, which was designed to mimic natural heparin-binding proteins and enable binding to a variety of proteins, increasing cellular recognition of these factors (Rajangam et al., 2006). When combined with VEGF or FGF, HBPA demonstrated improved angiogenesis and heart contractility in mouse (Webber et al., 2010a). Heparin is known to preserve growth factors in their active form by protecting them from proteolysis, and enhancing the affinity to their respective receptors, enabling consistent release of growth factors (Zhou et al., 2004); however, the use of heparin could trigger immune reactions due to its animal origin. To overcome this limitation, synthetic glycosaminoglycan (GAG) mimetic peptide nanofiber scaffolds were developed and assessed in vivo (Rufaihah et al., 2017). The GAG scaffolds induced neovascularization in the infarcted myocardium, along with increased VEGF expression and recruitment of vascular cells, which lead to significant improvements in cardiac performance.

Given the “hostile” environment within the infarcted heart, another approach has been to deliver soluble peptides within polymeric scaffolds to mimic extracellular matrix degradation products, which can act in a cytokine fashion (Zachman et al., 2013). The pro-angiogenic laminin-derived C16 and the anti-inflammatory thymosin β4-derived Ac-SDKP loaded in collagen hydrogels of scaffolds has shown to up-regulate the angiogenic response in subcutaneous implantation, while down-regulating inflammation, thus holding promise as a strategy for addressing ischemia and inflammation post-MI. Thymosin β4 has also been successfully incorporated into collagen-chitosan hydrogels for release in the heart post-MI, resulting in superior vascular growth and myocardial repair compared to unmodified hydrogels (Chiu et al., 2012).

Modification for Combination Therapies With Cells

Some large extracellular matrix (ECM) molecules, such as collagen and fibronectin, have multiple peptide sequences that are recognized by cells and induce multiple regenerative responses. To tackle the issue of poor retention and survival of reparative cellular components for MI, mimics of the nanotopographical cues of native ECM have been used to improve integration, proliferation and differentiation. The RGD sequence has been identified as the major cell-binding domain in fibronectin (Ruoslahti and Pierschbacher, 1987), and is able to act as ligands for the integrins αvβ5, αvβ3, and α5β1, which are expressed by cardiomyocytes (Ross Robert and Borg Thomas, 2001; Brancaccio et al., 2006). Functionalization of materials with the RGD motif may exert advantageous properties to the regenerating myocardium via better adhesion and cell integration. RGD incorporation into collagen and alginate scaffolds has been shown to improve cardiomyocyte contractility and viability (Schussler et al., 2009; Shachar et al., 2011). An RGD-alginate system was also able to improve vascular endothelial cell adhesion and proliferation, and increase blood vessel formation in vivo (Yu et al., 2009). When applied as microspheres encapsulating mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs); the RGD-alginate combination improved cell retention at the site of injection, in addition to enhanced arteriole formation in a rat MI model (Yu et al., 2010). Similarly, alginate scaffolds modified with a cyclic RGDfK-peptide, which is protease resistant and displays high affinity to cellular integrins, improved survival of transplanted MSCs and promoted angiogenesis in a rat MI model (Sondermeijer et al., 2017). RGDSP is also an adhesion sequence, which promotes cell adhesion and stimulates integrins relevant to early cardiac development (Kraehenbuehl et al., 2008). When combined with self-assembling peptide RADA16, the RGDSP scaffolds elicited protective effects for marrow-derived cardiac stem cells, which were isolated from MSCs and identified as c-kit, Nkx2.5, and GATA4 positive populations, and improved the cardiac function of post-MI rats via enhanced cardiac differentiation (Guo et al., 2010). RGDSP showed fibrous structure with nanometer diameters when assembled with RADA16, providing 3-dimensional scaffolds and presumably being beneficial to the microenvironment for the growth of transplanted cells. The YIGSR sequence (laminin-derived) is another example of ECM-derived peptide that has been investigated as functional additive to enhance cell therapies (Boateng et al., 2005). In one study, YIGSR was immobilized into a self-assembled peptide amphiphile in combination with a nitric oxide donor polylysine sequence (KKKKK) (Andukuri et al., 2013). The combination of these peptides was superior in capturing EPCs and inducing their differentiation into endothelial cells. QHREDGS is also a type of ECM-derived peptide, based on the fibrinogen-like domain of angiopoietin-1 (Rask et al., 2010; Miklas et al., 2013). Due to the homologous nature of the integrin ligands, QHREDGS sequence reportedly has a dual protective effect for both cardiomyocytes and endothelial cells in vitro (Reis et al., 2012). In rat MI model, QHREDGS incorporated within a collagen-chitosan hydrogel was demonstrated to improve cardiac function along with cardiac cell recruitment via β1-integrin (Reis et al., 2015). Although this data is promising in terms of cell recruitment to the site of treatment, the provoked downstream signaling may not be the same as that of native matrix possibly due to the other components contained within ECM proteins or structural differences. In an in vitro study, myocytes cultured with RGD and YIGSR peptides showed lower expression of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), a part of mechano-transduction pathways, even though the adhesion of the cells was comparable to the native proteins, fibronectin and laminin, and the β1-integrin expression levels were unchanged (Boateng et al., 2005).

Other peptide ligands which are fundamental to specific cell types have also been investigated. For instance, due to the fact that Notch signaling has been shown to promote cardiac progenitor cell (CPC) mediated cardiac repair (Boni et al., 2008), RADA self-assembling peptides have been functionalized with a peptide mimic of the Notch1 ligand Jagged1 and demonstrated to have therapeutic benefit when transplanted with CPCs by improving acute retention and ameliorating the cardiac remodeling in a rat MI model (Boopathy et al., 2014). Development of biomaterials which are capable of modulating signaling pathways critical for endogenous cell types such as NOTCH1 is of great importance as these cells are endogenously present in niches of defined composition and exert reparative effects depending on environmental cues following injury, aging or disease (Sanada et al., 2014). Circulating angiogenic cells (CACs) are another promising candidate of cell therapy for MI, playing essential roles in angiogenesis and myocardial regeneration. Formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2), belonging to the G protein-coupled receptor family, has been suggested to stimulate and promote chemotaxis of monocytic cell lines, neutrophils, and B lymphocytes (Gavins, 2010). WKYMVm, a synthetic hexapeptide with strong affinity to FRP2 was injected to post-MI mice, and demonstrated to enhance the mobilization of CACs from the bone marrow, this resulted in myocardial protection from apoptosis with increased vascular density and preservation of cardiac function (Heo et al., 2017). Likewise, stromal cell–derived factor-1 (SDF-1) is one of the key regulators of hematopoietic stem cells, and shown to effect proliferation and mobilization of EPCs, one of the major population of CACs, to induce vasculogenesis and to be significantly upregulated in myocardial ischemia (Pillarisetti and Gupta, 2001). However, exogenous SDF is quickly degraded by multiple proteases (Sierra et al., 2004). To overcome this limitation, a polypeptide analog was engineered and demonstrated enhanced physiological ability to induce EPC migration and improved ventricular performance compared with native SDF (Hiesinger et al., 2011). In another study, RoY, a 12 amino-acid synthetic peptide specifically binding to the 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein (GRP78) receptor, which is largely expressed on vascular endothelial cells under hypoxia, was conjugated to a thermosensitive chitosan chloride hydrogel. The material induced angiogenic activity and attenuated myocardial injury in a rat MI model (Shu et al., 2015). Histone deacetylase 7 (HDAC7)-derived- phosphorylated 7-amino-acid peptide has also been successfully incorporated into collagen hydrogels for release in the heart post-MI, resulting in superior vascular growth and myocardial repair via enhanced stem cell antigen-1 (Sca-1) positive stem cell recruitment and differentiation (Zhang et al., 2019). Although peptide-based strategies allow for control over cell adhesion, signal localization and cytokine release, the peptides are often highly ubiquitous and not specific to particular cell types or signaling pathways. Further investigations are required before these therapeutic materials are ready for clinical application.

Conclusions and Outlook

As the field looks to develop clinically translatable biomimetic materials for tissue regeneration, it is evident that peptide-based biomaterials have the ability to give rise to therapies which will not only provide improved quality of life, but also solve current problems associated with the xenogeneic nature of animal derived materials and the high cost of recombinantly prepared proteins. Due to recent advancements in SPPS and a better understanding of the structure-function relationship of peptides and proteins in complex biological settings, it is becoming more feasible to design targeted biomaterials capable of eliciting a desired response or enhanced biocompatibility. These short mimetic peptides are also typically more processable than their full length analogs and as such simpler to modify with a variety of different functionalities which could impart beneficial properties such as enhanced solubility, simple one step tethering to polymeric backbones, or stimuli responsiveness (pH, light, temperature, etc.). Given the complexity of the wound healing process, as we learn more about the factors determining tissue regeneration, it is likely that we will begin to see an increase in the development of combinatorial approaches and the design of materials consisting of numerous different structural and sequence based peptide mimics. While such complex materials are currently difficult to design, as predictive models improve and large bioactive peptide databases become available this task will be greatly simplified.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the authors cited in this work.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was made possible by funding from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant No. RGPIN-2015-0632 to EA. EA would also like to thank the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) for a Project Grant No. 375854. CM thanks the University of Ottawa Cardiac Endowment Fund at the Heart Institute for a postdoctoral fellowship. CL was thankful for the Queen Elizabeth II Graduate Scholarship in Science and Technology.

References

- Andrea L. D., Iaccarino G., Fattorusso R., Sorriento D., Carannante C., Capasso D., et al. (2005). Targeting angiogenesis: structural characterization and biological properties of a de novo engineered VEGF mimicking peptide. PNAS 102, 14215–14220. 10.1073/pnas.0505047102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andukuri A., Sohn Y. D., Anakwenze C. P., Lim D. J., Brott B. C., Yoon Y. S., et al. (2013). Enhanced human endothelial progenitor cell adhesion and differentiation by a bioinspired multifunctional nanomatrix. Tissue Eng. Part C Met. 19, 375–385. 10.1089/ten.tec.2012.0312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacsa B., Desai B., Dibo G., Kappe C. O. (2006). Rapid solid-phase peptide synthesis using thermal and controlled microwave irradiation. J. Pept. Sci. 12, 633–638. 10.1002/psc.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakota E. L., Wang Y., Danesh F. R., Hartgerink J. D. (2011). Injectable multidomain peptide nanofiber hydrogel as a delivery agent for stem cell secretome. Biomacromolecules 12, 1651–1657. 10.1021/bm200035r [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beniash E., Hartgerink J. D., Storrie H., Stendahl J. C., Stupp S. I. (2005). Self-assembling peptide amphiphile nanofiber matrices for cell entrapment. Acta Biomater. 1, 387–397. 10.1016/j.actbio.2005.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boateng S. Y., Lateef S. S., Mosley W., Hartman T. J., Hanley L., Russell B. (2005). RGD and YIGSR synthetic peptides facilitate cellular adhesion identical to that of laminin and fibronectin but alter the physiology of neonatal cardiac myocytes. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288, C30–C38. 10.1152/ajpcell.00199.2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boersema G. S. A., Grotenhuis N., Bayon Y., Lange J. F., Bastiaansen-Jenniskens Y. M. (2016). The effect of biomaterials used for tissue regeneration purposes on polarization of macrophages. BioResearch 5, 6–14. 10.1089/biores.2015.0041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boni A., Urbanek K., Nascimbene A., Hosoda T., Zheng H., Delucchi F., et al. (2008). Notch1 regulates the fate of cardiac progenitor cells. PNAS 105, 15529–15534. 10.1073/pnas.0808357105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Boopathy A. V., Che P. L., Somasuntharam I., Fiore V. F., Cabigas E. B., Ban K., et al. (2014). The modulation of cardiac progenitor cell function by hydrogel-dependent Notch1 activation. Biomaterials 35, 8103–8112. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.05.082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw M., Ho D., Fear M. W., Gelain F., Wood F. M., Iyer K. S. (2014). Designer self-assembling hydrogel scaffolds can impact skin cell proliferation and migration. Sci. Rep. 4:6903. 10.1038/srep06903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaccio M., Hirsch E., Notte A., Selvetella G., Lembo G., Tarone G. (2006). Integrin signalling: the tug-of-war in heart hypertrophy. Cardiovasc. Res. 70, 422–433. 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti J., Roscia G., Lampronti I., Gambari R., Quercini L., Falciani C., et al. (2016). Immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory activity in vitro and in vivo of a novel antimicrobial candidate. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 25742–25748. 10.1074/jbc.M116.750257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvete J. J., Schafer W., Mann K., Henschen A., Gonzalez-Rodriguez J. (1992). Localization of the cross-linking sites of RGD and KQAGDV peptides to the isolated fibrinogen receptor, the human platelet integrin glicoprotein IIb/IIIa. Influence of peptide length. Eur. J. Biochem. 206, 759–765. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16982.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattopadhyay S., Raines R. T. (2014). Review collagen-based biomaterials for wound healing. Biopolymers 101, 821–833. 10.1002/bip.22486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F.-M., Liu X. (2016). Advancing biomaterials of human origin for tissue engineering. Prog. Pol. Sci. 53, 86–168. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2015.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu L. L., Reis L. A., Momen A., Radisic M. (2012). Controlled release of thymosin beta4 from injected collagen-chitosan hydrogels promotes angiogenesis and prevents tissue loss after myocardial infarction. Regen. Med. 7, 523–533. 10.2217/rme.12.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho C.-H., Kammerer R. A., Lee H. J., Steinmetz M. O., Ryu Y. S., Lee S. H., et al. (2004). COMP-Ang1: a designed angiopoietin-1 variant with nonleaky angiogenic activity. PNAS 101, 5547–5552. 10.1073/pnas.0307574101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow L. W., Bitton R., Webber M. J., Carvajal D., Shull K. R., Sharma A. K., et al. (2011). A bioactive self-assembled membrane to promote angiogenesis. Biomaterials 32, 1574–1582. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu-Kung A. F., Bozzelli K. N., Lockwood N. A., Haseman J. R., Mayo K. H., Tirrell M. V. (2004). Promotion of peptide antimicrobial activity by fatty acid conjugation. Bioconjug. Chem. 15, 530–535. 10.1021/bc0341573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui X.-J., Xie H., Wang H.-J., Guo H.-D., Zhang J.-K., Wang C., et al. (2010). Transplantation of mesenchymal stem cells with self-assembling polypeptide scaffolds is conducive to treating myocardial infarction in rats. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 222, 281–289. 10.1620/tjem.222.281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. E., Hsieh P. C., Takahashi T., Song Q., Zhang S., Kamm R. D., et al. (2006). Local myocardial insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) delivery with biotinylated peptide nanofibers improves cell therapy for myocardial infarction. PNAS 103, 8155–8160. 10.1073/pnas.0602877103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M. E., Motion J. P., Narmoneva D. A., Takahashi T., Hakuno D., Kamm R. D., et al. (2005). Injectable self-assembling peptide nanofibers create intramyocardial microenvironments for endothelial cells. Circulation 111, 442–450. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000153847.47301.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana D., Basile A., De Rosa L., Di Stasi R., Auriemma S., Arra C., et al. (2011). beta-hairpin peptide that targets vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptors: design, NMR characterization, and biological activity. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41680–41691. 10.1074/jbc.M111.257402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'souza S. E., Ginsberg M. H., Plow E. F. (1991). Arginyl-glycyl-aspartic acid (RGD): a cell adhesion motif. Trends Biochem. Sci. 16, 246–250. 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90096-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois G., Segers V. F., Bellamy V., Sabbah L., Peyrard S., Bruneval P., et al. (2008). Self-assembling peptide nanofibers and skeletal myoblast transplantation in infarcted myocardium. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 87, 222–228. 10.1002/jbm.b.31099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfenbein A., Simons M., Murakami M. (2007). Non-canonical fibroblast growth factor signalling in angiogenesis. Cardiovasc. Res. 78, 223–231. 10.1093/cvr/cvm086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y., Mrksich M. (2004). The synergy peptide PHSRN and the adhesion peptide RGD mediate cell adhesion through a common mechanism. Biochemistry 43, 15811–15821. 10.1021/bi049174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N., Gerber H.-P., Lecouter J. (2003). The biology of VEGF and its receptors. Nat. Med. 9, 669–676. 10.1038/nm0603-669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari G., Cook B. D., Terushkin V., Pintucci G., Mignatti P. (2009). Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta1) induces angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated apoptosis. J. Cell. Physiol. 219, 449–458. 10.1002/jcp.21706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields G. B. (2010). Synthesis and biological applications of collagen-model triple-helical peptides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 8, 1237–1258. 10.1039/b920670a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finetti F., Basile A., Capasso D., Di Gaetano S., Di Stasi R., Pascale M., et al. (2012). Functional and pharmacological characterization of a VEGF mimetic peptide on reparative angiogenesis. Biochem. Pharm. 84, 303–311. 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavins F. N. (2010). Are formyl peptide receptors novel targets for therapeutic intervention in ischaemia–reperfusion injury? Trends Pharm. Sci. 31, 266–276. 10.1016/j.tips.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelain F., Bottai D., Vescovi A., Zhang S. (2006). Designer self-assembling peptide nanofiber scaffolds for adult mouse neural stem cell 3-dimensional cultures. PLoS ONE 1:e119. 10.1371/journal.pone.0000119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanaati S., Webber M. J., Unger R. E., Orth C., Hulvat J. F., Kiehna S. E., et al. (2009). Dynamic in vivo biocompatibility of angiogenic peptide amphiphile nanofibers. Biomaterials 30, 6202–6212. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.07.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore L., Rimmer S., Mcarthur S. L., Mittar S., Sun D., Macneil S. (2013). Arginine functionalization of hydrogels for heparin binding–a supramolecular approach to developing a pro-angiogenic biomaterial. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 110, 296–317. 10.1002/bit.24598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girotti A., Reguera J., Rodríguez-Cabello J. C., Arias F. J., Alonso M., Testera A. M. (2004). Design and bioproduction of a recombinant multi(bio)functional elastin-like protein polymer containing cell adhesion sequences for tissue engineering purposes. J. Mat. Sci. 15, 479–484. 10.1023/B:JMSM.0000021124.58688.7a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes A., Teixeira C., Ferraz R., Prudêncio C., Gomes P. (2017). Wound-healing peptides for treatment of chronic diabetic foot ulcers and other infected skin injuries. Molecules 22:1743. 10.3390/molecules22101743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf J., Iwamoto Y., Sasaki M., Martin G. R., Kleinman H. K., Robey F. A., et al. (1987a). Identification of an amino acid sequence in laminin mediating cell attachment, chemotaxis, and receptor binding. Cell 48, 989–996. 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90707-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graf J., Ogle R. C., Robey F. A., Sasaki M., Martin G. R., Yamada Y., et al. (1987b). A pentapeptide from the laminin B1 chain mediates cell adhesion and binds the 67,000 laminin receptor. Biochemistry 26, 6896–6900. 10.1021/bi00396a004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. D., Cui G. H., Wang H. J., Tan Y. Z. (2010). Transplantation of marrow-derived cardiac stem cells carried in designer self-assembling peptide nanofibers improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 399, 42–48. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.07.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H. D., Cui G. H., Yang J. J., Wang C., Zhu J., Zhang L. S., et al. (2012). Sustained delivery of VEGF from designer self-assembling peptides improves cardiac function after myocardial infarction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 424, 105–111. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hautanen A., Gailit J., Mann D. M., Ruoslahti E. (1989). Effects of modifications of the RGD sequence and its context on recognition by the fibronectin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 1437–1442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo S. C., Kwon Y. W., Jang I. H., Jeong G. O., Lee T. W., Yoon J. W., et al. (2017). Formyl peptide receptor 2 is involved in cardiac repair after myocardial infarction through mobilization of circulating angiogenic cells. Stem Cells 35, 654–665. 10.1002/stem.2535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesinger W., Perez-Aguilar J. M., Atluri P., Marotta N. A., Frederick J. R., Fitzpatrick J. R., III., Mccormick R. C., et al. (2011). Computational protein design to reengineer stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha generates an effective and translatable angiogenic polypeptide analog. Circulation 124, S18–S26. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.009431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh P. C., Davis M. E., Gannon J., Macgillivray C., Lee R. T. (2006a). Controlled delivery of PDGF-BB for myocardial protection using injectable self-assembling peptide nanofibers. J. Clin. Invest. 116, 237–248. 10.1172/JCI25878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh P. C., Macgillivray C., Gannon J., Cruz F. U., Lee R. T. (2006b). Local controlled intramyocardial delivery of platelet-derived growth factor improves postinfarction ventricular function without pulmonary toxicity. Circulation 114, 637–644. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.639831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G. F., Riordan J. F., Vallee B. L. (1997). A putative angiogenin receptor in angiogenin-responsive human endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 2204–2209. 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbell J. A., Massia S. P., Desai N. P., Drumheller P. D. (1991). Endothelial cell-selective materials for tissue engineering in the vascular graft via a new receptor. Nat. Biotechnol. 9, 568–572. 10.1038/nbt0691-568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huettner N., Dargaville T. R., Forget A. (2018). Discovering cell-adhesion peptides in tissue engineering: beyond RGD. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 372–383. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter D. D., Cashman N., Morris-Valero R., Bulock J. W., Adams S. P., Sanes J. R. (1991). An LRE (leucine-arginine-glutamate)-dependent mechanism for adhesion of neurons to S-laminin. J. Neurosci. 11, 3960–3971. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.11-12-03960.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidro-Llobet A., Alvarez M., Albericio F. (2009). Amino acid-protecting groups. Chem. Rev. 109, 2455–2504. 10.1021/cr800323s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Islam M. M., Ravichandran R., Olsen D., Ljunggren M. K., Fagerholm P., Lee C. J., et al. (2016). Self-assembled collagen-like-peptide implants as alternatives to human donor corneal transplantation. RSC Adv. 6, 55745–55749. 10.1039/C6RA08895C [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jangamreddy J. R., Haagdorens M. K. C., Mirazul Islam M., Lewis P., Samanta A., Fagerholm P., et al. (2018). Short peptide analogs as alternatives to collagen in pro-regenerative corneal implants. Acta Biomater. 69, 120–130. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun H. W., Yuwono V., Paramonov S. E., Hartgerink J. D. (2005). Enzyme-mediated degradation of peptide-amphiphile nanofiber networks. Adv. Mater. 17, 2612–2617. 10.1002/adma.200500855 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahlenberg J. M., Kaplan M. J. (2013). Little peptide, big effects: the role of LL-37 in inflammation and autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 191, 4895–4901. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. H., Park Y., Jung Y., Kim S. H., Kim S. H. (2017). Combinatorial therapy with three-dimensionally cultured adipose-derived stromal cells and self-assembling peptides to enhance angiogenesis and preserve cardiac function in infarcted hearts. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 11, 2816–2827. 10.1002/term.2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. K., Anderson J., Jun H. W., Repka M. A., Jo S. (2009). Self-assembling peptide amphiphile-based nanofiber gel for bioresponsive cisplatin delivery. Mol. Pharm. 6, 978–985. 10.1021/mp900009n [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman H. K., Graf J., Iwamoto Y., Sasaki M., Schasteen C. S., Yamada Y., et al. (1989). Identification of a second active site in laminin for promotion of cell adhesion and migration and inhibition of in vivo melanoma lung colonization. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 272, 39–45. 10.1016/0003-9861(89)90192-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight C. G., Morton L. F., Peachey A. R., Tuckwell D. S., Farndale R. W., Barnes M. J. (2000). The collagen-binding A-domains of integrins alpha(1)beta(1) and alpha(2)beta(1) recognize the same specific amino acid sequence, GFOGER, in native (triple-helical) collagens. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35–40. 10.1074/jbc.275.1.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koide T. (2005). Triple helical collagen-like peptides: engineering and applications in matrix biology. Connect. Tissue Res. 46, 131–141. 10.1080/03008200591008518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koria P., Yagi H., Kitagawa Y., Megeed Z., Nahmias Y., Sheridan R., et al. (2011). Self-assembling elastin-like peptides growth factor chimeric nanoparticles for the treatment of chronic wounds. PNAS 108, 1034–1039. 10.1073/pnas.1009881108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraehenbuehl T. P., Zammaretti P., Van Der Vlies A. J., Schoenmakers R. G., Lutolf M. P., Jaconi M. E., et al. (2008). Three-dimensional extracellular matrix-directed cardioprogenitor differentiation: systematic modulation of a synthetic cell-responsive PEG-hydrogel. Biomaterials 29, 2757–2766. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krock B. L., Skuli N., Simon M. C. (2011). Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis: good and evil. Genes Cancer 2, 1117–1133. 10.1177/1947601911423654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]