Abstract

Find out how one hospital introduced a mindfulness-based stress reduction program to increase work satisfaction and decrease burnout.

Figure.

No caption available.

The health of our nurses is perhaps the most important consideration for delivering excellent patient care. Achieving optimal outcomes for the patient and family requires nurses to function at the highest level of health, both physically and psychologically. The American Nurses Association's Health Risk Appraisal report found that 82% of nurses believe they're at a significant level of risk for illness due to workplace stress.1 Employers can help create a healthy workplace and promote interventions that add to nurses' personal health. These efforts also help retain nurses in the profession.

Nursing practice in hospital settings is changing due to higher patient acuity, which places more demands on nurses. Certain areas, such as the ED and critical care, also add stress due to the nature of the work. The turnover of new graduate nurses in their first year of work is reported to be as high as 17%, and slightly over 3% of new graduate nurses reported leaving because of work-related stress.2 Addressing the issues surrounding the clinical work of nurses is crucial for overall recruitment and retention. Most nurses can effectively manage the demands of the hospital setting; however, they may develop job burnout and potentially leave the profession. Nurses may end their shift feeling dissatisfied after a limited amount of time to be present with patients. The time allocated to nursing care is often consumed with tasks, and finding quality time with patients may be difficult.

Managing clinical work stress then becomes critical not only for patient care, but also for nurses' health and long-term tenure. A possible solution to nurses' work stress, retention, and personal health may rest in learning to manage clinical work through the development of mindfulness—awareness of the present moment—as taught in mindfulness meditation programs, such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR).

MBSR is a program of class instruction and practice in mindfulness techniques, meditation, and Hatha yoga designed to promote physical and psychological well-being.3 Professionally trained personnel lead the MBSR program for 2.5 hours weekly over the course of 8 weeks, plus a full-day retreat. Participants practice the techniques learned in class daily. The program teaches participants to be open and nonjudgmental while intentionally being present with others and the environment. Through MBSR training, participants learn how to accept their lived experience, including moments of pain.

Research studies examining MBSR have found many benefits, including a decrease in stress and burnout.4-8 Mindfulness training has been associated with statistically significant increased relaxed states and decreased heart rate.9 Stress reduction and increased relaxed states may improve nurses' decision-making through enhanced situational awareness. The MBSR program is associated with statistically significant increases in mindfulness and elements of self-compassion.10 Mindfulness training significantly improves self-compassion in healthcare professionals.11 A qualitative, phenomenologic research study on mindfulness found an increased capacity for “being with” patients and developing deeper connections.12

This article examines the effects of MBSR on job-relevant factors, including mindfulness, self-compassion, empathy, serenity, work satisfaction, incidental overtime, and job burnout.

Study purpose and methods

A quasi-experimental, longitudinal, pretest and posttest, correlational study was conducted in 2009 with a convenience sample of RNs working at a 619-bed tertiary care hospital in the upper midwestern US.

The specific aims of this study were to determine:

the effects of MBSR on mindfulness, self-compassion, empathy, serenity, and work satisfaction in RNs. (Hypothesis 1: Mindfulness, self-compassion, empathy, serenity, and work satisfaction will be greater after the MBSR intervention relative to baseline.)

the correlation between the variables of mindfulness and self-compassion, empathy, and serenity in RNs. (Hypothesis 2: Mindfulness will be positively associated with self-compassion, empathy, and serenity.)

the effects of MBSR on shift incidental overtime in RNs. (Hypothesis 3: Incidental overtime will decrease from baseline after the MBSR intervention.)

the presence of job burnout after MBSR relative to baseline in RNs. (Hypothesis 4: Job burnout will decrease following the MBSR intervention.)

Sample and setting

An attempt was made to heavily recruit clinical nurses from all patient care units. The target sample for this study was 50 RNs; 83 RNs were recruited to account for potential dropouts. A final sample of 61 nurses completed the MBSR program.

To qualify for the study, nurses were required to be adult (age 21 or older), English-speaking RNs employed by the hospital who had no self-disclosed currently diagnosed psychiatric illness and who were interested in enrolling in the intervention, able to read the course materials and attend weekly classes, and willing to complete an informed-consent process and study data collection forms. Individuals were excluded if they previously participated in the MBSR program, were regularly practicing mindfulness meditation, expressed uncertainty about attending regularly, or intended to relocate in the next 6 months.

An a priori power analysis was completed before enrollment. Sample size was calculated on the basis that a sample of 50 participants would have 80% power to detect a P <.05.

Instruments

Demographic information was collected by a self-administered survey. Six self-administered data collection instruments were used to obtain information from the nurses: the Brief Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory, Self-Compassion Scale, Brief Serenity Scale, Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Index of Work Satisfaction, and Maslach Burnout Inventory. All instruments are psychometrically sound with strong Cronbach's alpha.13-21 Incidental overtime was obtained from the hospital's payroll department by patient care unit, not individual nurse, and defined as less than 2.5 hours after a shift.

Procedures

After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval, the principal investigator used flyers, emails, staff meetings, council meetings, and one-to-one discussions to recruit nurses to participate in one of four simultaneously managed intervention groups consisting of the MBSR program taught by the same instructor on different days and times of the week. Nurses chose the class time to participate. Data collection occurred via self-report surveys administered to the nurses at multiple points across the study: 3 months before the intervention for overtime, immediately before the intervention for all data points, at 8 weeks, and 3 months after the intervention for overtime. To control for random effects and increase consistency across the groups, all groups were assessed within the same time frame. Measurements were administered to participants by the principal investigator.

The program used for this study was based on Kabat-Zinn's MBSR program.3 The instructor was a licensed family therapist and founder of a mindfulness practice center. Class length was modified to 2 hours per class instead of the original program's 2.5-hour classes. A 7-hour retreat was offered to participants between weeks 6 and 7.

Data analysis

After the data were analyzed for normality, descriptive statistics were used to summarize the nurse demographic data. Results were analyzed using paired t-tests (within group analysis) for matched results from 53 nurses to measure the pre- and posteffects of the MBSR intervention on the study outcomes. Within-group analysis was conducted at 8 weeks using P <.05. The correlation between mindfulness and the study outcomes was examined using multiple regression analysis. The pre- and posteffects of MBSR on incidental overtime by patient care unit and job burnout were trended using regression analysis; standard error of beta was used for the pre- and postmeasure of incidental overtime.

Results

The demographic characteristics included the beginning sample of nurses, as well as the completion sample of 61 nurses. Similar demographics were found in both the beginning and ending samples. Of those who completed the study, 95% were female, which is representative of this hospital's nurse population. Of those dropped from the study, a majority worked part time and on the day shift. In addition, most dropouts had less than 5 years of nursing experience.

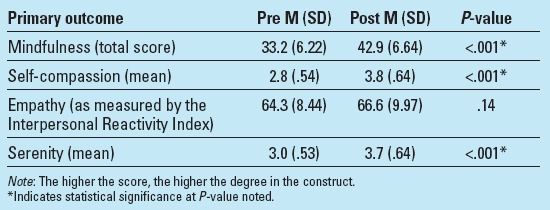

The study's primary aim was to determine the effects of the MBSR program on mindfulness, self-compassion, empathy, and serenity. During posttest administration, eight nurses weren't matched to their pretest numerical code, leaving 53 nurses who could be compared with their pretest scores. Paired t-tests were computed on the mean and standard deviation (SD) from baseline to posttest after the MBSR intervention. The within-group analysis (paired t-tests) showed a positive, statistically significant difference in mindfulness, self-compassion, and serenity after the MBSR intervention. Empathy, as measured on the Interpersonal Reactivity Index, didn't show a statistically significant difference after the MBSR intervention. The hypothesis that mindfulness, self-compassion, and serenity would be greater after the MBSR intervention relative to baseline was supported. The hypothesis that empathy would be greater after the MBSR intervention relative to baseline wasn't supported. (See Table 1.)

Table 1:

Within-group analysis of mindfulness, self-compassion, empathy, and serenity before and after MBSR

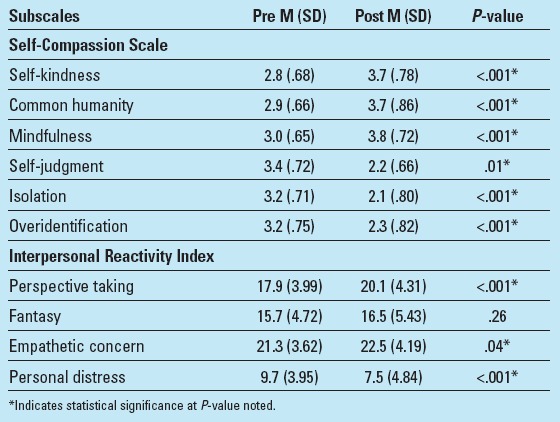

The Self-Compassion Scale and Interpersonal Reactivity Index subscales were compared before and after the MBSR intervention. (See Table 2.) All the Self-Compassion Scale subscales were statistically significantly improved after the MBSR intervention as compared with the baseline. The Interpersonal Reactivity Index subscales of perspective taking, empathetic concern, and personal distress were statistically significantly improved after the MBSR intervention; the fantasy subscale wasn't statistically significantly greater after the MBSR intervention as compared with the baseline.

Table 2:

Pre- to posteffects for Self-Compassion Scale and Interpersonal Reactivity Index subscales

The primary aim also tested the effect of MBSR on work satisfaction. Using a paired comparison technique, nurses ranked the importance of each Index of Work Satisfaction subscale: interaction (4.69), autonomy (3.7), task (3.0), pay (3.0), organizational policies (2.9), and professional status (2.7). An Index of Work Satisfaction score was computed for the group of nurses before and after the MBSR intervention. There were no statistically significant differences in the total Index of Work Satisfaction scores from baseline. The hypothesis that work satisfaction would be greater after the MBSR intervention relative to baseline wasn't supported.

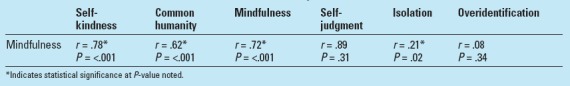

The second aim of this study was to determine the correlation between the dependent variable of mindfulness and the independent variables of self-compassion, empathy, and serenity. A positive, statistically significant correlation was evident between mindfulness and self-compassion (r = .79, P <.001), and mindfulness and serenity (r = .78, P <.001). The relationship was weak and insignificant between mindfulness and empathy. The hypothesis that mindfulness would be positively associated with self-compassion and serenity was supported. However, the hypothesis that mindfulness would be positively associated with empathy wasn't supported by the data. Further analysis revealed a positive, statistically significant correlation between mindfulness and the Self-Compassion Scale subscales of self-kindness, common humanity, mindfulness, and isolation; however, not for the subscales of overidentification and self-judgment. (See Table 3.)

Table 3:

Correlation of mindfulness with Self-Compassion Scale subscales

One exploratory aim was to determine the effects of the MBSR intervention on the job performance measure of shift incidental overtime. Incidental overtime was trended from before the start of the study to 3 months after the MBSR intervention. A downward trend in incidental overtime was seen on all nursing units. However, this decline in incidental overtime wasn't statistically significant.

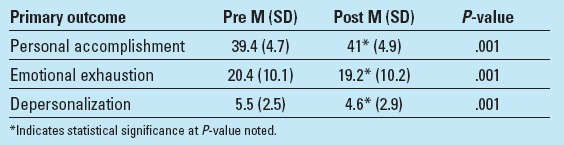

The second exploratory aim of this study was to evaluate a change in job burnout using the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Improvements in each of the subscales were statistically significant after the MBSR intervention. (See Table 4.) The hypothesis that burnout would decrease after the MBSR intervention was supported.

Table 4:

Pre- to posteffects for Maslach Burnout Inventory subscales

Discussion

The findings from this study demonstrated a reduction in job burnout and improvement in specific psychological factors—mindfulness, self-compassion, and serenity—through the use of a mindfulness-based program and its practices. Mindfulness may be an effective method to improve several psychosocial aspects of health and nurses' well-being, which can help retain nurses at the bedside. Often, nurses encounter negative experiences while caring for patients and families or interacting with other healthcare team members. Having a technique such as mindfulness to help foster self-compassion and serenity may be helpful in these situations. To establish healthier work environments, mindfulness may help nurses put situations in perspective and promote positive reactions to stress.

Although this study found several statistically significant results consistent with the hypotheses, there are several features that may be interpreted as limitations. The study didn't use a randomized controlled sample and had no comparison group. The study sample is limited to one geographic area. All assessment measures were self-reported and open to response bias. The attrition rate may have influenced the results of the study. Potential selection bias occurred in the sample; nurses may have chosen to participate due to stress or just to learn.

The strengths of this study include adding to the field for use of mindfulness in nursing, a low attrition rate, access to study subjects, and efficiency of recruitment and analysis.

Translation into nursing practice

The potential for nurses to learn how to use mindfulness has promise in today's clinical settings. Nurses are leaving the bedside and often feel unfulfilled and stressed. The tendency for a person experiencing a stressful or traumatic situation is to become immersed in the feelings and thoughts of stress that can lead to anger, sorrow, discomfort, tension, and illness. Nursing leadership can advocate for mindfulness programs to help their staff members redirect negative thinking and reframe difficult situations. The use of mindfulness techniques such as breathing exercises on a regular basis and in difficult situations helps a person be aware of negativity and place it in the proper perspective. The more the individual practices, the more he or she can separate from negativity and gain insight into the situation.

Nurses talk about a heaviness associated with dealing with difficult people and situations. If we lighten this burden through mindfulness, we can achieve better outcomes and work satisfaction. The practice of mindfulness can help nurses achieve a more satisfactory outcome the next time a similar negative situation occurs. The nurse learns that stress is optional, and situations can be managed more effectively. Nurse leaders can also benefit from mindfulness practice, including increased focus, awareness, and knowing.

Because mindfulness needs to be performed regularly, having a group of nurses in the same workplace take a course together promotes camaraderie and support when difficult situations occur. Imagine working alongside a fellow nurse and helping him or her identify the difficult situation, the potential for a negative reaction, and the possibility to see beyond it!

The tools to manage stress

Nursing is a high-stress profession that may be taking a toll on our nurses. Mindfulness-based programs can help nurses develop skills to manage clinical stress and improve their health; increase overall attention, empathy, and presence with patients and families; and experience work satisfaction, serenity, decreased incidental overtime, and reduced job burnout.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Nurses Association. Executive summary: American Nurses Association health risk appraisal. 2016. www.nursingworld.org/~495c56/globalassets/practiceandpolicy/healthy-nurse-healthy-nation/ana-healthriskappraisalsummary_2013-2016.pdf.

- 2.Spector N, Blegen MA, Silvestre J, et al. Transition to practice study in hospital settings. J Nurs Reg. 2015;5(4):24–38. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living. New York, NY: Delacorte Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bazarko D, Cate RA, Azocar F, Kreitzer MJ. The impact of an innovative mindfulness-based stress reduction program on the health and well-being of nurses employed in a corporate setting. J Workplace Behav Health. 2013;28(2):107–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duchemin AM, Steinberg BA, Marks DR, Vanover K, Klatt M. A small randomized pilot study of a workplace mindfulness-based intervention for surgical intensive care unit personnel: effects on salivary a-amylase levels. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(4):393–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gauthier T, Meyer RM, Grefe D, Gold JI. An on-the-job mindfulness-based intervention for pediatric ICU nurses: a pilot. J Pediatr Nurs. 2015;30(2):402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hevezi JA. Evaluation of a meditation intervention to reduce the effects of stressors associated with compassion fatigue among nurses. J Holist Nurs. 2016;34(4):343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song Y, Lindquist R. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression, anxiety, stress and mindfulness in Korean nursing students. Nurse Educ Today. 2015;35(1):86–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amutio A, Martínez-Taboada C, Hermosilla D, Delgado LC. Enhancing relaxation states and positive emotions in physicians through a mindfulness training program: a one-year study. Psychol Health Med. 2015;20(6):720–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bergen-Cico D, Possemato K, Cheon S. Examining the efficacy of a brief mindfulness-based stress reduction (brief MBSR) program on psychological health. J Am Coll Health. 2013;61(6):348–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raab K, Sogge K, Parker N, Flament MF. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and self-compassion among mental healthcare professionals: a pilot study. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2015;18(6):503–512. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker S. Working in the present moment: the impact of mindfulness on trainee psychotherapists' experience of relational depth. Couns Psychother Res. 2016;16(1):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walach H, Buchheld N, Buttenmiller V, Kleinknecht N, Schmidt S. Measuring mindfulness—the Freiburg Mindfulness Inventory (FMI). Pers Individual Differences. 2006;40:1543–1555. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Neff K. Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self Identity. 2003;2:85–101. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neff KD, Rude SS, Kirkpatrick KL. An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. J Res Personality. 2007;41(4):908–916. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neff KD. The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. http://self-compassion.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/ScaleMindfulness.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kreitzer MJ, Gross CR, Waleekhachonloet OA, Reilly-Spong M, Byrd M. The brief serenity scale: a psychometric analysis of a measure of spirituality and well-being. J Holist Nurs. 2009;27(1):7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Personality Soc Psych. 1983;44(1):113–126. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beven JP, O'Brien-Malone A, Hall G. Using the interpersonal reactivity index to assess empathy in violent offenders. Int J Forensic Psych. 2004;1(2):33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stamps PL. Nurse and Work Satisfaction: An Index for Measurement. Chicago, IL: Health Administration Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Occup Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113. [Google Scholar]