Abstract

Background

Poly((R)-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-(R)-3-hydroxyhexanoate) [P(3HB-co-3HHx)] is a bacterial polyester with high biodegradability, even in marine environments. Ralstonia eutropha has been engineered for the biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-3HHx) from vegetable oils, but its production from structurally unrelated carbon sources remains unsatisfactory.

Results

Ralstonia eutropha strains capable of synthesizing P(3HB-co-3HHx) from not only fructose but also glucose and glycerol were constructed by integrating previously established engineering strategies. Further modifications were made at the acetoacetyl-CoA reduction step determining flux distribution responsible for the copolymer composition. When the major acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB1) was replaced by a low-activity paralog (PhaB2) or enzymes for reverse β-oxidation, copolyesters with high 3HHx composition were efficiently synthesized from glucose, possibly due to enhanced formation of butyryl-CoA from acetoacetyl-CoA via (S)-3HB-CoA. P(3HB-co-3HHx) composed of 7.0 mol% and 12.1 mol% 3HHx fractions, adequate for practical applications, were produced at cellular contents of 71.4 wt% and 75.3 wt%, respectively. The replacement by low-affinity mutants of PhaB1 had little impact on the PHA biosynthesis on glucose, but slightly affected those on fructose, suggesting altered metabolic regulation depending on the sugar-transport machinery. PhaB1 mostly acted in the conversion of acetoacetyl-CoA when the cells were grown on glycerol, as copolyester biosynthesis was severely impaired by the lack of phaB1.

Conclusions

The present results indicate the importance of flux distribution at the acetoacetyl-CoA node in R. eutropha for the biosynthesis of the PHA copolyesters with regulated composition from structurally unrelated compounds.

Background

Bio-based plastics and biodegradable plastics have attracted much attention as eco-friendly alternatives to petroleum-based plastics. In particular, biodegradable plastics have become increasingly important as recent studies have provided evidence of serious pollution in marine environments due to the debris of synthetic polymers, called microplastics [1, 2]. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are biopolyesters synthesized by a variety of bacteria and some archaea from renewable carbon resources [3, 4]. They are synthesized as an intracellular storage of carbon and energy, generally when cell growth is limited by the depletion of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus, or oxygen in the presence of excess carbon sources. It has been demonstrated that PHAs show high biodegradability in various environments, including marine ones [5–7].

Poly[(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate] [P(3HB)], a homopolyester of (R)-3-hydroxybutyrate, is the most abundant PHA in nature. In many P(3HB)-producing bacteria, two molecules of acetyl-CoA are converted to (R)-3-hydroxybutyryl (3HB)-CoA by β-ketothiolase (PhaA) and NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB) and then polymerized to P(3HB) by the function of PHA synthase (PhaC). Unfortunately, the range of application of P(3HB) has been limited due to its high crystallinity and brittleness. Substantial research has therefore been conducted on the microbial synthesis of PHA copolymers exhibiting better mechanical properties by adding precursor compounds into the cultivation medium, as well as metabolic engineering [4]. Poly((R)-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-(R)-3-hydroxyhexanoate) [P(3HB-co-3HHx)], a kind of short-chain-length/medium-chain-length-PHA copolymer, is one of the most practical PHAs because the copolyester composed of > 10 mol% of the C6 fraction shows more flexible properties with lower melting temperature and crystallinity than P(3HB) homopolymer [8]. This copolyester was initially identified as a PHA synthesized by Aeromonas caviae from vegetable oils and fatty acids [8, 9]. The biosynthesis genes in A. caviae are clustered as phaP-C-JAc encoding PHA granule-associated protein (phasin), PHA synthase with unique substrate specificity to 3HA-CoAs of C4 to C7, and short-chain-length-specific (R)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase (R-hydratase), respectively [10–12].

Ralstonia eutropha (Cupriavidus necator) strain H16 is known as an efficient producer of P(3HB) from fructose, gluconate, vegetable oils, and fatty acids. The P(3HB) biosynthesis genes are clustered on chromosome 1 as phaC-A-B1 [13]. PhaB1 is the major acetoacetyl-CoA reductase for the supply of (R)-3HB-CoA for polymerization, while the weakly expressed paralog PhaB3 partially supports P(3HB) synthesis in phaB1-deleted strains grown on fructose [14]. BktB, a β-ketothiolase paralog having broader substrate specificity than PhaA, is involved in the generation of C5 intermediates for the biosynthesis of poly((R)-3-hydroxybutyrate-co-(R)-3-hydroxyvalerate) copolymer with propionate supplementation [15]. Several studies have focused on the metabolic engineering of R. eutropha for the biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-3HHx) from vegetable oils [16–21]. Meanwhile, considering the inexpensiveness and availability of sugars and glycerol, P(3HB-co-3HHx) production from such structurally unrelated compounds is an important technology to be established. This is also an interesting challenge in metabolic engineering because no wild microbes capable of synthesizing P(3HB-co-3HHx) from sugars have been known so far. We have therefore focused on this issue and achieved the biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-22 mol% 3HHx) from fructose by an engineered strain of R. eutropha equipped with an artificial pathway [22, 23]. The key step in this pathway is the formation of butyryl-CoA from crotonyl-CoA by the combination of crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase (Ccr) [24] and ethylmalonyl-CoA decaroboxylase (Emd) [25], through which ethylmalonyl-CoA formed from crotonyl-CoA by reductive carboxylase activity of Ccr was converted back to butyryl-CoA by Emd. Butyryl-CoA was then condensed with acetyl-CoA to form 3-oxohexanoyl-CoA and further converted to (R)-3HHx-CoA, which was copolymerized with (R)-3HB-CoA by PhaCNSDG, a N149S/D171G mutant of PHA synthase from A. caviae [26]. One drawback of R. eutropha H16 is the rather narrow spectrum of utilizable carbon sources, as this strain is unable to utilize glucose, xylose, and arabinose and grows slowly on glycerol. The substrate utilization range of R. eutropha H16 has been expanded by genetic modification [27]. For examples, the strains capable of utilizing glucose [28–30], mannose [30], sucrose [31], as well as that with enhanced glycerol utilization [32] have been reported.

In the previous P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis from fructose by the artificial pathway in R. eutropha, we observed that the deletion of phaB1 was an important modification to achieve a high 3HHx fraction in the copolyester, but this was accompanied by a decrease of PHA production [23]. In this study, we modified the acetoacetyl-CoA reduction step in R. eutropha to establish enough flux for the formation of both (R)-3HB-CoA and (R)-3HHx-CoA from acetoacetyl-CoA, aiming at the efficient biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-3HHx) composed of ~ 10 mol% of the C6 unit, potentially suitable for practical applications, from structurally unrelated carbon sources.

Results

Integrated engineering of R. eutropha for P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis from glucose and glycerol

Ralstonia eutropha strain NSDG was previously constructed by replacing the original PHA synthase gene (phaC) on chromosome 1 with phaCNSDG encoding a mutant of PHA synthase derived from A. caviae [33]. It has been demonstrated that PhaCNSDG can synthesize P(3HB-co-3HHx) with higher levels of 3HHx than the wild-type enzyme [26]. A recombinant strain of R. eutropha capable of synthesizing the copolyester from glucose and glycerol was constructed based on the strain NSDG by the integration of three further engineering strategies. Glucose-assimilation ability was conferred by the disruption of nagR and mutation in nagE corresponding to substitution of Gly265 by Arg in the EIIC-EIIB component of the GlcNAc-specific phosphoenolpyruvate sugar phosphotransferase (PTS) system (Additional file 1: Fig. S1A) [28]. glpFK genes derived from E. coli were then inserted into chromosome 1 in order to enhance glycerol assimilation (Additional file 1: Fig. S1B) [32]. The resulting strain NSDG-GG highly accumulated P(3HB) homopolymer from glucose, fructose, and glycerol (81.2–83.1 wt% of the dry cell mass) as shown in entries 1, 14, and 27 in Figs. 2, 3 and 4, respectively. The detailed results of the cultivation experiments in this study are shown in Additional file 1: Tables S1–S3. The enhanced P(3HB) production from glucose by this strain has also been reported by Biglari et al. [34]. pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd is a previously constructed plasmid for the biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-3HHx) from fructose by R. eutropha [23], in which phaJ4a derived from R. eutropha encodes R-hydratase showing higher activity to 2-hexenoyl-CoA than crotonyl-CoA [C6 > C4] [18]. The introduction of this plasmid into the strain NSDG-GG enabled P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis from glucose and glycerol as well as from fructose with high cellular content (75.2–82.0 wt%), although the 3HHx fractions were 2.3 mol% or less (entries 2, 15, and 28). When the plasmid-borne phaJ4a was replaced by phaJAc derived from A. caviae [12], encoding the R-hydratase specific to short-chain-length-substrate [C6 < C4], the PHA production tended to decrease (66.2–76.1 wt%) with still low levels of 3HHx fraction (entries 8, 21, and 34).

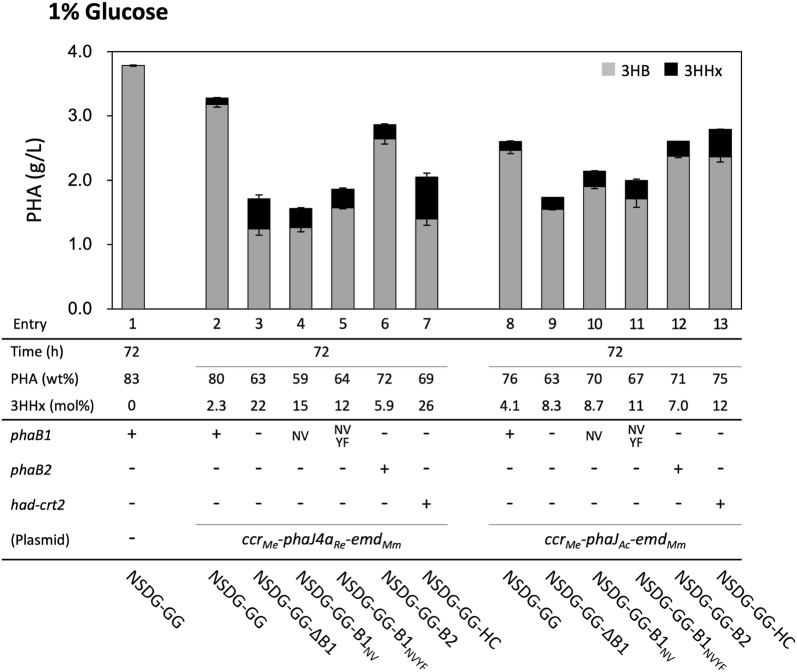

Fig. 2.

P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis by NSDG-GG-based engineered strains of R. eutropha from glucose. The amounts of 3HB and 3HHx units in PHA are shown in gray and black bars, respectively. The cells were cultivated in a 100 ml MB medium containing 1% (w/v) glucose for 72 h at 30 °C (n = 3)

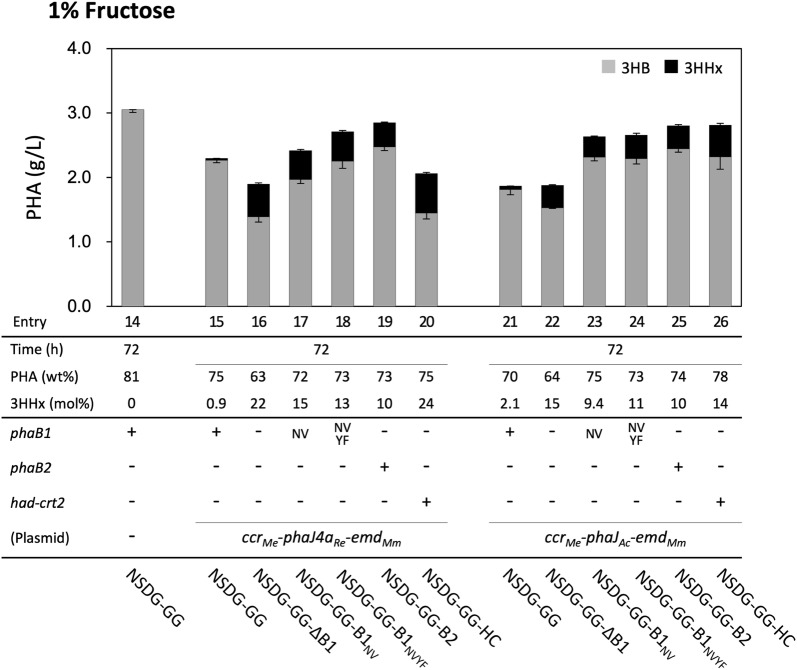

Fig. 3.

P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis by NSDG-GG-based engineered strains of R. eutropha from fructose. The amounts of 3HB and 3HHx units in PHA are shown in gray and black bars, respectively. The cells were cultivated in a 100 ml MB medium containing 1% (w/v) fructose for 72 h at 30 °C (n = 3)

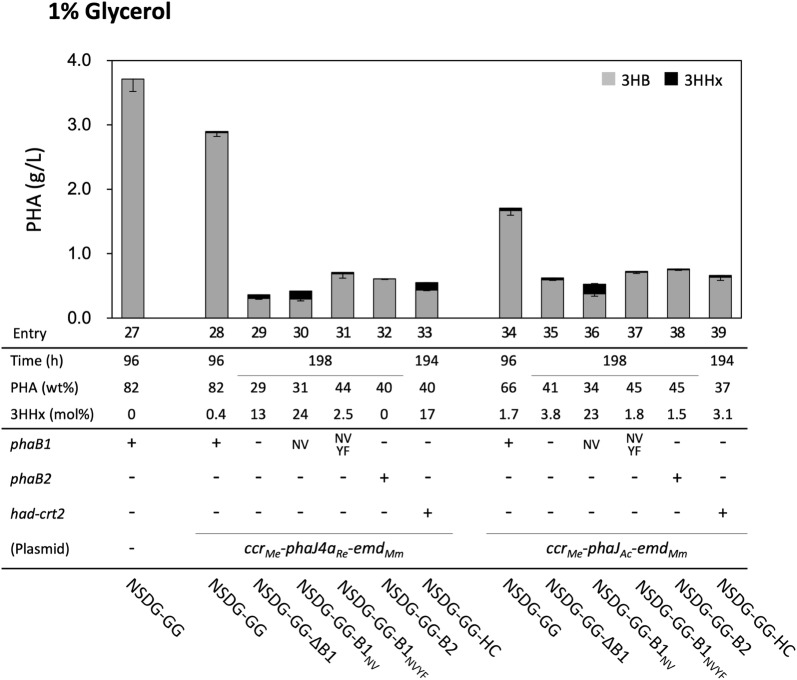

Fig. 4.

P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis by NSDG-GG-based engineered strains of R. eutropha from glycerol. The amounts of 3HB and 3HHx units in PHA are shown in gray and black bars, respectively. The cells were cultivated in a 100 ml MB medium containing 1% (w/v) glycerol for 96 h or 194 h–198 h at 30 °C (n = 3)

Deletion of phaB1 and the effects on PHA biosynthesis from glucose

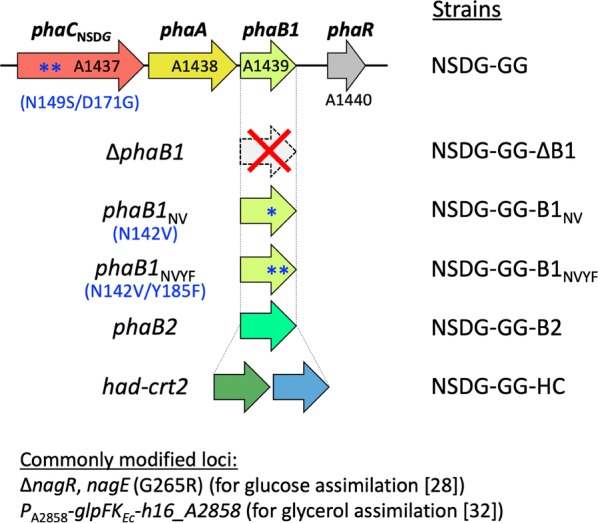

The phaB1-deleted strain NSDG-GG-∆B1 (Fig. 1) harboring pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd produced the copolyester composed of a much higher 3HHx fraction (22.0 mol%) with lower content (62.5 wt%) from glucose (entry 3 in Fig. 2) when compared with the corresponding phaB1+ strain (entry 2). Such effects of phaB1-deletion were also observed for the strains harboring PhaJAc (pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd) [entries 9 (∆phaB1) and 8 (phaB1+)], although the increase in 3HHx composition was less significant (up to 8.3 mol%) than that of the strain having PhaJ4a. These compositional changes caused by the phaB1 deletion, also seen in the previous study [23], were due to not only a relative increase in 3HHx units attributed to a decrease in 3HB units, but also a net increase in C6 units (Additional file 1: Table S1). It was likely that (R)-3HB-CoA formation from acetoacetyl-CoA was dominated by the function of PhaB1 showing high catalytic efficiency and being highly expressed [35, 36], while the formation of butyryl-CoA from acetoacetyl-CoA via (S)-3HB-CoA became significant when the competing (R)-specific reduction was mediated by only PhaB3 and consequently weakened in the absence of PhaB1. We then investigated the effects of introducing low-activity mutants or paralog of PhaB1, or enzymes for reverse β-oxidation, on the copolyester biosynthesis properties, as described below.

Fig. 1.

Schematic diagram of genotypes of R. eutropha NSDG-GG-based recombinant strains. phaCNSDG, a gene encoding N149S/D171G mutant of PHA synthase from A. caviae; phaA, β-ketothiolase gene; phaB1, a gene encoding major NADPH-acetoacetyl-CoA reductase; phaRRe, PHA-binding transcriptional repressor gene; phaB1NV and phaB1NVYF, genes encoding N142V and N142V/Y185F mutants of PhaB1; phaB2, a gene encoding minor NADPH-acetoacetyl-CoA reductase; had, NAD-(S)-3HB-CoA dehydrogenase gene, crt2, crotonase gene. The commonly modified loci in these strains are shown in Additional file 1: Fig. S1

Introduction of low affinity mutants of PhaB1 and the effects on PHA biosynthesis from glucose

We had attempted protein engineering of PhaB1 based on the crystal structure [37], and obtained mutants with low affinity toward acetoacetyl-CoA, as described in Additional Information. The kinetic parameters of PhaB1 and the mutants using N-His6-tagged recombinant proteins are shown in Table 1. We confirmed very high affinity of PhaB1 to acetoacetyl-CoA with a Km value of 2 μM, as previously reported [37, 38], and observed substrate inhibition at acetoacetyl-CoA concentrations higher than 12 μM. N142V and Y185F mutants of PhaB1 (designated as PhaB1NV and PhaB1YF) showed much larger Km values toward acetoacetyl-CoA, whereas Vmax values were not affected by the N142V mutation and retained at 78% by the Y185F mutation, when compared with those of the parent wild-type enzyme. The double mutations of N142V and Y185F markedly decreased catalytic efficiency, as Km and Vmax of the double mutant PhaB1NVYF to acetoacetyl-CoA increased 50-fold and decreased by one-third of those of PhaB1, respectively.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of PhaB paralogs and PhaB1 mutants from R. eutropha toward acetoacetyl-CoA

| Enzyme | Mutation(s) | Km [μM] | Vmax [U mg−1] | kcat [s−1] | kcat/Km [μM−1 s−1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhaB1 | 1.99 ± 0.23 | 162 ± 6 | 71.2 ± 2.7 | 35.8 ± 4.4 | |

| PhaB1NV | N142V | 58.5 ± 18.1 | 175 ± 31 | 76.7 ± 2.7 | 1.31 ± 0.47 |

| PhaB1YF | Y185F | 86.2 ± 20.6 | 127 ± 17 | 55.8 ± 7.6 | 0.65 ± 0.18 |

| PhaB1NVYF | N142V/Y185F | 109 ± 38 | 53.9 ± 8.3 | 23.7 ± 3.7 | 0.22 ± 0.08 |

| PhaB2 | 2.48 ± 0.63 | 10.5 ± 0.6 | 4.90 ± 0.28 | 2.00 ± 0.52 | |

| PhaB3 | 1.27 ± 0.53 | 88.9 ± 8.7 | 40.8 ± 4.0 | 32.7 ± 14.0 |

PhaB1NV (low-affinity) and PhaB1NVYF (low-affinity and low-activity) were here applied with the aim of achieving moderate weakening of the (R)-specific reduction step in the P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis pathway. The two mutant genes were individually introduced into the strain NSDG-GG-∆B1 downstream of phaA in the chromosome of NSDG-GG-∆B1 (original phaB1 locus) (Fig. 1), and the resulting strains NSDG-GG-B1NV and NSDG-GG-B1NVYF were used as hosts for pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd or pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd. When these strains were cultivated on glucose, however, unexpectedly the copolyester biosynthesis properties (entries 4, 5, and 11 in Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Table S1) were not greatly changed when compared with those of the phaB1-deleted strains (entries 3 and 9), except for NSDG-GG-B1NV/pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd (entry 10) that accumulated slightly more P(3HB-co-3HHx) than the phaB1-deleted strain.

Introduction of low-activity paralog PhaB2 and the effects on PHA biosynthesis from glucose

Although a previous study revealed the roles of the three PhaB paralogs in P(3HB) biosynthesis by R. eutropha [14], the catalytic properties of PhaB2 and PhaB3 had yet to be determined. Table 1 also shows the results of kinetic analysis of PhaB2 and PhaB3 using the N-terminal His6-tagged recombinant proteins. Both PhaB2 and PhaB3 showed very high affinity to acetoacetyl-CoA, with Km values of 2.5 μM and 1.3 μM, respectively, and substrate inhibition as well as PhaB1, while the Vmax values of PhaB2 and PhaB3 were one order of magnitude lower and about half, respectively, when compared with that of PhaB1.

As PhaB2 was supposed to be applicable as a low-activity reductase for the moderate weakening of the (R)-specific reduction of acetoacetyl-CoA, the strain NSDG-GG-B2 was constructed by inserting phaB2 downstream of phaA in the chromosome of NSDG-GG-∆B1 (Fig. 1). The strain transformed with pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd or pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd accumulated P(3HB-co-5.9–7.0 mol% 3HHx) with 71.4–72.3 wt% cellular content on glucose (entries 6 and 12 in Fig. 2), which demonstrated that the insertion of phaB2 into the pha operon increased PHA production when compared with the phaB1-deleted strains. The amounts of the 3HB and 3HHx units incorporated into the polyester were intermediate between those by NSDG-GG (phaB1+) and NADG-GG-∆B1 (phaB1–) strains (Additional file 1: Table S1). This was consistent with the altered flux distribution from acetoacetyl-CoA to (R)-3HB-CoA and (S)-3HB-CoA by PhaB2. No significant difference in the PHA production was observed between the strains harboring PhaJAc and PhaJ4a.

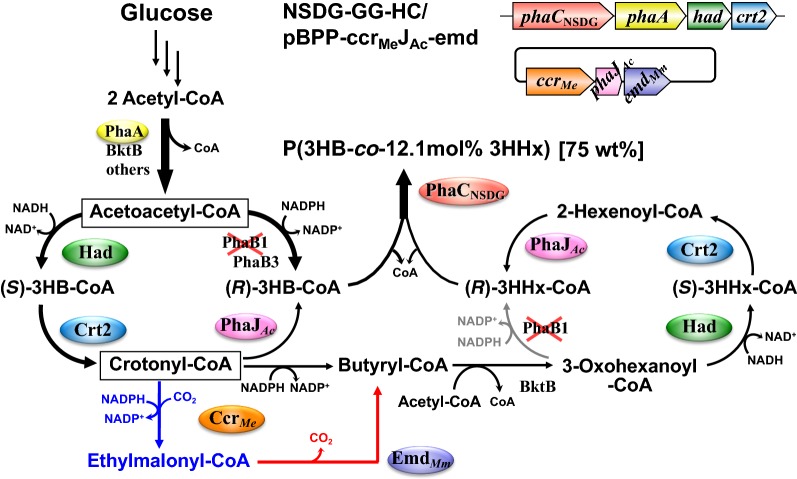

Enhancement of reverse β-oxidation and the effects on PHA biosynthesis from glucose

We recently identified two NAD(H)-dependent (S)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenases, PaaH1 (H16_A0282) and Had (H16_A0602), as well as (S)-specific enoyl-CoA hydratase (crotonase) Crt2 (H16_A3307) in the cell extract of R. eutropha [39]. Analysis of the enzymatic characteristics indicated that these enzymes showed rather broad specificities with high activities toward the C4–C8 substrates. We thus utilized Had and Crt2 for P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis, because these enzymes along with endogenous β-ketothiolases (PhaA, BktB, etc.) and CcrMe-EmdMm could potentially establish reverse β-oxidation converting three acetyl-CoA molecules to 2-hexenoyl-CoA via (S)-3HA-CoA intermediates. A tandem of had and crt2 was inserted downstream of phaA in NSDG-GG-∆B1 (Fig. 1), and the resulting strain NSDG-GG-HC was further transformed with the plasmids for the copolyester synthesis. The strains harboring pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd or pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd produced copolyesters with 3HHx compositions of 26.0 mol% and 12.1 mol% from glucose (entries 7 and 13 in Fig. 2), respectively, which were higher than those by the corresponding ∆phaB1 strains (entries 3 and 9). Although the increase of 3HHx composition with PhaJAc was smaller than that with PhaJ4a, the cellular content of P(3HB-co-3HHx) by the strain harboring phaJAc reached up to 75.3 wt%, which was comparable to that of the corresponding phaB1+ strain NSDG-GG/pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd (entry 8).

PHA biosynthesis by the engineered R. eutropha strains from fructose

Ralstonia eutropha strains NSDG-GG-∆B1 harboring either plasmid for P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis accumulated the copolyester from fructose with much higher 3HHx composition of 14.7–21.5 mol% (entries 16 and 22 in Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Table S2) than the parent phaB1+ strains (entries 15 and 21), as also seen on glucose. The insertion of phaB2 into the phaB1-deleted chromosome increased the copolyester content up to 73.0–74.1 wt%, of which the 3HHx composition (10.0–10.3 mol%) was intermediate between those by phaB1-deleted and phaB1+ strains (entries 19 and 25). The enhancement of reverse β-oxidation in the phaB1-deleted strain increased the 3HHx composition, as the strain harboring phaJAc efficiently produced P(3HB-co-13.8 mol% 3HHx) (entry 26). Although these properties were similar to those on glucose, a few different features were observed. One is that the reduction of the cellular PHA content caused by the phaB1 deletion on fructose was less than that on glucose. Interesting differences were observed in the effects of the low-activity mutants of PhaB1. Unlike on glucose, the insertion of phaB1NV or phaB1NVYF into the phaB1-deleted strain promoted incorporation of the 3HB unit, resulting in an increase of PHA content and a relatively slight decrease of the 3HHx composition on fructose (entries 17, 18, 23, and 24).

PHA biosynthesis by the engineered R. eutropha strains from glycerol

The strains NSDG-GG harboring the copolyester biosynthesis plasmid produced P(3HB-co-3HHx) from glycerol, although the 3HHx fractions showed faint levels of 0.4–1.7 mol% (entries 28 and 34 in Fig. 4 and Additional file 1: Table S3). In contrast to the cultivation on sugars, the phaB1 deletion severely impaired PHA biosynthesis from glycerol. When the strain NSDG-GG-∆B1/pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd was cultivated on glycerol, the optical density at 600 nm (OD600) increased very slowly and reached to maximum (~ 6) after prolonged cultivation for 196 h (data not shown). This OD600 value was about half of those on sugars after 72 h, and the cellular PHA content was only 29.4 wt% (entry 29). Although the 3HHx composition of 13.1 mol% was rather high, this was attributed to a marked decrease in 3HB units. We noticed that this slow increase in OD600 on glycerol was not due to slow cell growth, as the residual cell mass after 96 h cultivation on glycerol (0. 81 g/L) was not so markedly less than that on fructose after 72 h (1.10 g/L). Given that the optical density of PHA-producing cells was responsible for both cell concentration and intracellular accumulation of PHA, the slow increase in optical density after 96 h indicated a low rate of PHA synthesis on glycerol caused by the phaB1 deletion. Further engineered strains showed still poor PHA biosynthesis ability on glycerol despite the insertion of phaB1NV, phaB1NVYF, phaB2, or had-crt2 (entries 30–33). The impaired ability to biosynthesize PHA could not be restored even by PhaJAc having high activity to crotonyl-CoA (entries 35-39).

Discussion

The microbial production of P(3HB-co-3HHx) has usually utilized vegetable oils or fatty acids as carbon sources because the provision of (R)-3HHx-CoA monomer can be simply achieved by (R)-specific hydration of 2-enoyl-CoA intermediate in β-oxidation catalyzed by R-hydratase (PhaJ) [12]. The industrial production of P(3HB-co-3HHx) from palm oil by recombinant R. eutropha has been demonstrated by Kaneka Corp., Japan, since 2011. In addition to vegetable oils, the use of other inexpensive biomass feedstocks, such as sugars and glycerol, is expected to be another promising way of achieving low-cost production and consequent wide applications. From this perspective, we previously engineered R. eutropha for the expansion of utilizable carbon sources [28, 32] and for the generation and polymerization of (R)-3HHx-CoA from fructose through an artificial pathway [23]. These were here integrated into R. eutropha, which led to the construction of strains capable of synthesizing P(3HB-co-3HHx) from not only fructose but also glucose and glycerol. However, the yield and 3HHx composition of the copolyesters were insufficient, so further investigation focused on improving the strains to achieve efficient production of the copolyesters with a higher 3HHx fraction.

NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase (PhaB) is an (R)-3HB-CoA-providing enzyme in most P(3HB)-producing microorganisms, and R. eutropha possesses three paralogs of PhaB (PhaB1, PhaB2, PhaB). The roles of the multiple PhaBs in R. eutropha have been investigated and discussed based on the biosynthesis of P(3HB) homopolymer [14]. PhaB1 from R. eutropha has also been frequently applied in PHA biosynthesis by engineered E. coli strains. Nevertheless, the effects of modifications in the acetoacetyl-CoA reduction step on the biosynthesis of PHA copolymers have not been well considered. In the case of P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis from fructose by the previously engineered R. eutropha [23], deletion of phaB1 was an important modification for the incorporation of 3HHx unit into the polyester fraction, although this accompanied the reduction of PHA production. It was supposed that (R)-3HB-CoA provision in the phaB1-lacking strain, supported by the minor paralog PhaB3 (associated with only 2%–5% of total NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase activity in cell extracts of R. eutropha [14, 33]), was significantly weakened when compared with the parent phaB1+-strains. This tradeoff between production and composition of the copolyesters depending on the presence or absence of PhaB1 coincided with the formation of butyryl-CoA mainly via (S)-3HB-CoA, and suggested the importance of flux distribution at the acetoacetyl-CoA node for the copolyester biosynthesis through the artificial pathway. We assumed that moderate weakening of the (R)-specific reduction of acetoacetyl-CoA would establish metabolic flux distribution from acetoacetyl-CoA to (R)- and (S)-3HB-CoAs suitable for P(3HB-co-3HHx) synthesis. The R. eutropha strains were thus modified by introducing low-affinity mutants (PhaB1NV and PhaB1NVYF) and a low-activity paralog (PhaB2) of PhaB1 for moderate weakening of the (R)-specific reduction. On glucose, the use of PhaB2 instead of PhaB1 resulted in production of the copolyester with cellular content and 3HHx composition in-between those by the phaB1+ and ∆phaB1 strains, whereas the two kinds of low-affinity mutant of PhaB1 did not significantly affect PHA biosynthesis. These results demonstrated that the flux distribution from acetoacetyl-CoA toward C4- and C6-monomers can be regulated by specific activity levels of the reductase when the enzyme retains high affinity to acetoacetyl-CoA. As previous metabolomic analysis of R. eutropha showed a very low intracellular concentration of acetoacetyl-CoA [40], high substrate affinity of the reductase was required to change the metabolic fluxes. Another idea to overcome the tradeoff was the enhancement of reverse β-oxidation forming 2-enoyl-CoAs from 3-oxoacyl-CoAs via (S)-3HA-CoAs. The introduction of the second copies of had and crt2 into the pha operon in the ∆phaB1 strain increased the 3HHx composition of the polyester fraction without a serious negative impact on PHA production. The combination of the enhanced reverse β-oxidation and weakened (R)-specific reduction possibly increased butyryl-CoA formation from acetoacetyl-CoA and the following elongation to 3-oxohexanoyl-CoA, as well as the next reverse cycle to (R)-3HHx-CoA (Fig. 5). As seen on vegetable oils [18], the copolyester biosynthesis was also affected by the substrate specificity of R-hydratase. The use of short-chain-length-specific PhaJAc tended to increase the C4 units and decreas the C6 units when compared with medium-chain-length-specific PhaJ4a. This was because crotonyl-CoA was the second node for redistribution of the flux to the C4- and C6-monomers. When PhaJAc was functional, crotonyl-CoA was partially intercepted to form (R)-3HB-CoA and thus the decrease in the C4 units caused by the lack of PhaB1 was compensated to some extent (Fig. 5). Wang et al. reported on the biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-3HHx) from glucose by recombinant E. coli strains harboring trans-2-enoyl-CoA reductase from Treponema denticola in BktB-dependent condensation pathway (14.2 wt%, 4.0 mol% 3HHx) or reverse β-oxidation pathway using FadBA from E. coli (12.4 wt%, 10.2 mol% 3HHx) [41]. In this study, the practically useful P(3HB-co-12.1 mol% 3HHx) could be produced with cellular content of 75.3 wt% from glucose by the engineered R. eutropha strain NSDG-GG-HC/pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd.

Fig. 5.

Proposed pathway for P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis from glucose by R. eutropha NSDG-GG-HC/pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd. PhaA and BktB, β-ketothiolases; PhaB1 and PhaB3, NADPH-acetoacetyl-CoA reductases; Had, NAD-(S)-3HB-CoA dehydrogenase; Crt2, crotonase; PhaCNSDG, N149S/D171G mutant of PHA synthase from A. caviae; PhaJAc, short-chain-length-(R)-enoyl-CoA hydratase from A. caviae; CcrMe, crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase from Methylorubrum extorquens; EmdMm, ethylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase from Mus musculus

The modifications of the acetoacetyl-CoA reduction step had similar effects on P(3HB-co-3HHx) biosynthesis from fructose to those from glucose (Fig. 3 and Additional file 1: Table S2), although differences were observed when the PhaB1 mutants were introduced. On fructose, the recombinant strains having PhaB1NV or PhaB1NVYF accumulated more PHA with a larger 3HB fraction than the ∆phaB1 strain, which was not seen on glucose. This result strongly suggested actual functions of the PhaB1 mutants in (R)-3HB-CoA formation on fructose, despite the low affinity to acetoacetyl-CoA. This might be due to altered metabolic regulation depending on the sugar uptake machinery. In the R. eutropha H16-derived strains, fructose is incorporated and 6-phosphorylated by ATP-binding cassette transporter (FrcACB) [42] and fructokinase, respectively, while the uptake and 6-phosphorylation of glucose is mediated by mutated GlcNAc-specific PTS (NagFE) [28]. It is well known that glucose-specific PTS is associated with catabolite repression in E. coli. Likewise, the glucose-transportation by the mutant of NagFE in the R. eutropha strains may affect gene expression and consequent changes in metabolic regulation, such as a further decrease in intracellular pool of acetoacetyl-CoA, toward which catalytic functions of the low-affinity PhaB1 mutants were limited.

The engineered strain NSDG-GG could grow and accumulate P(3HB) well on glycerol, whereas the deletion of phaB1 severely impaired PHA biosynthesis from glycerol, unlike from sugars. It has been demonstrated that PhaB1 and PhaB3 contributed to P(3HB) biosynthesis on fructose, while only PhaB1 had a role on palm oil [14]. This was probably due to weak expression of phaB3 on palm oil as shown by microarray analysis [35]. The present results strongly suggested that phaB3 expression was tightly repressed on not only vegetable oils but also another non-sugar substrate, glycerol. We further observed that introduction of the genes of PhaB1 mutants, PhaB2, or Had-Crt2 into the ∆phaB1 strain only faintly restored the PHA biosynthesis. The highly efficient and highly expressed PhaB1 was essential to convert acetoacetyl-CoA to (R)-3HB-CoA under the conditions on glycerol. A further engineering strategy to enhance the C6 unit-formation pathway even with the functions of PhaB1 should be investigated to achieve the production of P(3HB-co-3HHx) from glycerol. Such strategy is also expected to be useful for more efficient production of PHA copolyesters and other compounds by phaB1+-strains from various structurally unrelated carbon sources.

Conclusions

We herein engineered Ralstonia eutropha for the biosynthesis of P(3HB-co-3HHx) from structurally unrelated glucose and glycerol by conferring glucose assimilation ability, enhancing glycerol assimilation ability, and installing an artificial pathway for biosynthesis of the copolyester. Further modifications at the acetoacetyl-CoA reduction step demonstrated the importance of flux distribution at the acetoacetyl-CoA node in R. eutropha for the biosynthesis of the PHA copolyesters with regulated composition from the structurally unrelated compounds. The moderate weakening of the (R)-specific reduction of acetoacetyl-CoA or enhancement of reverse β-oxidation allowed efficient biosynthesis of the copolyesters from glucose with high 3HHx composition, possibly due to enhanced formation of butyryl-CoA, a precursor of the C6-intermediates, from acetoacetyl-CoA via (S)-3HB-CoA. This study can provide important information for the engineering of R. eutropha for the production of PHAs as well as other acetyl-CoA-derived compounds.

Methods

Bacterial strains and plasmids

The strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. Escherichia coli strains DH5α and S17-1 [43], used as a host strain for general genetic engineering and transconjugation, respectively. R. eutropha strains were routinely cultivated at 30 °C in a nutrient-rich (NR) medium containing 1% (w/w) meat extract, 1% (w/v) polypeptone, 0.2% (w/w) yeast extract dissolved in tap water. Kanamycin (100 µg/mL for E. coli and 250 µg/mL for R. eutropha strains) or ampicillin (100 µg/mL for E. coli) was added into the medium when necessary.

Table 2.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Relevant marker | Source or references |

|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | F−, ϕ80lacZ∆M15, ∆(lacZYA-argF) U169, deoR, recA1, endA1, hsdR17(r−K m+K), phoA, supE44, λ−, thi-1, gyrA96, relA1 | Lab stock |

| BL21(DE3) | E. coli B, F−, dcm, ompT, hsdS(r−B m−B), gal, λ(DE3) | Novagen |

| S17-1 | thi pro hsdR recA chromosomal RP4; Tra+; Tmpr Str/Spcr | [43] |

| Ralstonia eutropha | ||

| H16 | Wild type | DSM 428 |

| NSDG | H16 derivative; ΔphaC::phaCNSDG | [33] |

| NSDG-GG | NSDG derivative; ΔnagR, nagE(G793C), PA2858-glpFKEc-h16_A2858 | This study |

| NSDG-GGΔB1 | NSDG-GG derivative; ΔphaB1 | This study |

| NSDG-GG-BNV | NSDG-GG∆B1 derivative; phaB1NV | This study |

| NSDG-GG-BNVYF | NSDG-GG∆B1 derivative; phaB1NVYF | This study |

| NSDG-GG-B2 | NSDG-GG∆B1 derivative; ∆phaB1::phaB2 | This study |

| NSDG-GG-HC | NSDG-GG∆B1 derivative; ∆phaB1::had-crt2 | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEE32 | pUC18 derivative; phaPCJAc | [10] |

| pBPP | pBBR ori (broad host range), mob, Kanr, PphaP1 | [44] |

| pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd | pBPP derivative; ccrMe, phaJ4a, emdMm | [23] |

| pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd | pBPP derivative; ccrMe, phaJAc, emdMm | This study |

| pColdII | ColE1 ori, Ampr, PcspA | Takara Bio |

| pColdII-phaB1 | pColdII derivative, phaB1 | This study |

| pColdII-phaB2 | pColdII derivative, phaB2 | This study |

| pET15b-phaB3 | pET15b derivative, phaB3 | This study |

| pColdII-phaB1NV | pColdII derivative, phaB1NV | This study |

| pColdII-phaB1NVYF | pColdII derivative, phaB1NVYF | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-AR | pK18mobsacB derivative; phaB1 del | [33] |

| pK18mobsacB-ABNVYFR | pK18mobsacB-AR derivative; phaB1NVYF ins | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-ABNVR | pK18mobsacB-AR derivative; phaB1NV ins | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-AB2R | pK18mobsacB-AR derivative; phaB2 ins | This study |

| pK18mobsacB-AHCR | pK18mobsacB-AR derivative; had-crt2 ins | This study |

The postfix del and ins indicate constructs for targeted gene deletion and insertion, respectively

Ac, Aeromonas caviae; Me, Methylorubrum extorquens; Mm, Mus musculus. phaCNSDG, a gene encoding N149S/D171G mutant of PHA synthase from A. caviae. phaB1NV and phaB1NVYF, genes encoding N142V and N142V/Y185F mutants of NADPH-acetoacetyl-CoA reductase PhaB1 from R. eutropha, respectively

Plasmid construction

DNA manipulations were carried out according to standard procedures, and PCR reactions were performed with KOD-Plus ver.2 DNA polymerase (Toyobo, Osaka). The sequences of oligonucleotide primers used in this study are shown in Additional file 1: Table S4.

pColdII-phaB1, pColdII-phaB2, and pET15b-phaB3 vectors for overproduction of N-His6-tagged PhaB1, PhaB2, and PhaB3 in E. coli, respectively, were constructed as described in Supporting Information. Site-directed mutagenesis of phaB1 was carried out by QuickChange protocol. A DNA fragment consisting of a tandem of had and crt2 was prepared by fusion PCR. Several plasmids were constructed by blunt-end ligation of a DNA fragment with a linear fragment of the backbone plasmid prepared by inverse PCR. pBPP-ccrMeJAc-emd was constructed by replacement of phaJ4a in pBPP-ccrMeJ4a-emd [23, 44] by phaJAc amplified with pEE32 [10] as a template. Plasmids for homologous recombination for insertion of the mutagenized genes of phaB1, phaB2, or had-crt2 into chromosome 1 of R. eutropha at the phaB1 locus were constructed from pK18mobsacB-AR previously made for deletion of phaB1 [33]. The target genes were individually inserted into pK18mobsacB-AR as located downstream of phaA with the same orientation.

Preparation of N-His6-tagged recombinant proteins and enzyme assay

Overexpression of phaB genes in E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring the expression plasmids with IPTG induction, and purification of the N-His6-tagged recombinant proteins using Ni-affinity chromatography were carried out as described in Supporting Information. NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl-CoA reductase activity was assayed in the mixture composed of 200 μM NADPH, 1 to 20 μM acetoacetyl-CoA (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), and enzyme solution with appropriate dilution in 200 μL of 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The consumption of NADPH accompanied by decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was monitored at 30 °C (ε340 = 6.22 × 103 M−1 cm−1).

Construction of recombinant strains of R. eutropha

Transformation of R. eutropha was carried out by transconjugation using E. coli S17-1 harboring a pK18mobsacB-based plasmid as a donor, and transformants generated by pop in-pop out recombination were isolated as described previously [20, 33]. R. eutropha strain NSDG-GG was constructed by sequential chromosomal modifications for glucose assimilation [28] and enhanced glycerol assimilation [32] into strain NSDG [33]. The strain NSDG-GG-∆B1 was constructed by deletion of phaB1 in NSDG-GG using pK18mobsacB-AR, and the other strains NSDG-GG-BNV, NSDG-GG-BNVYF, NSDG-GG-B2, and NSDG-GG-HC were obtained by insertion of phaB1NV, phaB1NVYF, phaB2, and had-crt2, respectively, into NSDG-GG-∆B1 at downstream of phaA using the corresponding plasmids.

PHA production

Ralstonia eutropha strains were cultivated at 30 °C in 100 mL of a nitrogen-limited mineral salts (MB) medium composed of 0.9 g of Na2HPO4•12H2O, 0.15 g of KH2PO4, 0.05 g of NH4Cl, 0.02 g of MgSO4•7 H2O, and 0.1 ml of trace-element solution [45] in 100 ml of deionized water. A filter-sterilized solution of glucose, fructose, or glycerol was added to the medium at a final concentration of 1.0% (w/v) as a sole carbon source. Kanamycin was added at the final concentration of 300 µg/mL. After the cultivation for 72 h with reciprocal shaking (115 strokes/min), the cells were harvested, washed once with cold deionized water, and then lyophilized. The cellular PHA content and composition were determined by gas chromatography (GC) after direct methanolysis of the dried cells in the presence of 15% sulfuric acid as described previously [45].

Supplementary information

Additional file 1. Additional figures and tables.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors’ contributions

MZ performed most experiments, data analyses, and wrote the manuscript. SK constructed and characterized mutant enzymes. IO and SN coordinated the study and contributed to the experimental design and data interpretation. TF designed the study and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25630373, and JST A-STEP (Adaptable and Seamless Technology Transfer Program through Target-driven R&D) Grant Number AS2915157U.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s12934-019-1197-7.

References

- 1.Jambeck JR, Geyer R, Wilcox C, Siegler TR, Perryman M, Andrady A, Narayan R, Law KL. Marine pollution Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science. 2015;347:768–771. doi: 10.1126/science.1260352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Waring RH, Harris RM, Mitchell SC. Plastic contamination of the food chain: a threat to human health? Maturitas. 2018;115:64–68. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kourmentza C, Placido J, Venetsaneas N, Burniol-Figols A, Varrone C, Gavala HN, Reis MAM. Recent advances and challenges towards sustainable polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) production. Bioengineering (Basel). 2017;4:E55. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering4020055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taguchi S, Iwata T, Abe H, Doi Y. Poly(hydroxyalkanoate)s. In: Matyjaszewski K, Möller M, editors. Polymer Science: a comprehensive reference. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 157–182. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasuya K, Takagi K, Ishiwatari S, Yoshida Y, Doi Y. Biodegradabilities of various aliphatic polyesters in natural waters. Polym Degrad Stab. 1998;59:327–332. doi: 10.1016/S0141-3910(97)00155-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsuji H, Suzuyoshi K. Environmental degradation of biodegradable polyesters 2. Poly(ε-caprolactone), poly [(R)-3-hydroxybutyrate], and poly(L-lactide) films in natural dynamic seawater. Polym Degrad Stab. 2002;75:357–365. doi: 10.1016/S0141-3910(01)00239-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narancic T, Verstichel S, Reddy Chaganti S, Morales-Gamez L, Kenny ST, De Wilde B, Babu Padamati R, O’Connor KE. Biodegradable plastic blends create new possibilities for end-of-life management of plastics but they are not a panacea for plastic pollution. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:10441–10452. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b02963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Doi Y, Kitamura S, Abe H. Microbial synthesis and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) Macromolecules. 1995;28:4822–4828. doi: 10.1021/ma00118a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimamura E, Kasuya K, Kobayashi G, Shiotani T, Shima Y, Doi Y. Physical-properties and biodegradability of microbial poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) Macromolecules. 1994;27:878–880. doi: 10.1021/ma00081a041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukui T, Doi Y. Cloning and analysis of the poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) biosynthesis genes of Aeromonas caviae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4821–4830. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.15.4821-4830.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fukui T, Kichise T, Iwata T, Doi Y. Characterization of 13 kDa granule-associated protein in Aeromonas caviae and biosynthesis of polyhydroxyalkanoates with altered molar composition by recombinant bacteria. Biomacromolecules. 2001;2:148–153. doi: 10.1021/bm0056052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukui T, Shiomi N, Doil Y. Expression and characterization of (R)-specific enoyl coenzyme A hydratase involved in polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis by Aeromonas caviae. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:667–673. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.3.667-673.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pohlmann A, Fricke WF, Reinecke F, Kusian B, Liesegang H, Cramm R, Eitinger T, Ewering C, Potter M, Schwartz E, Strittmatter A, Voss I, Gottschalk G, Steinbuchel A, Friedrich B, Bowien B. Genome sequence of the bioplastic-producing “Knallgas” bacterium Ralstonia eutropha H16. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1257–1262. doi: 10.1038/nbt1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Budde CF, Mahan AE, Lu J, Rha C, Sinskey AJ. Roles of multiple acetoacetyl coenzyme A reductases in polyhydroxybutyrate biosynthesis in Ralstonia eutropha H16. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5319–5328. doi: 10.1128/JB.00207-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slater S, Houmiel KL, Tran M, Mitsky TA, Taylor NB, Padgette SR, Gruys KJ. Multiple β-ketothiolases mediate poly(β-hydroxyalkanoate) copolymer synthesis in Ralstonia eutropha. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:1979–1987. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.1979-1987.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Budde CF, Riedel SL, Willis LB, Rha C, Sinskey AJ. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from plant oil by engineered Ralstonia eutropha strains. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2847–2854. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02429-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Insomphun C, Mifune J, Orita I, Numata K, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Modification of β-oxidation pathway in Ralstonia eutropha for production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from soybean oil. J Biosci Bioeng. 2014;117:184–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawashima Y, Cheng W, Mifune J, Orita I, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Characterization and functional analyses of R-specific enoyl coenzyme A hydratases in polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing Ralstonia eutropha. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2012;78:493–502. doi: 10.1128/AEM.06937-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Loo CY, Lee WH, Tsuge T, Doi Y, Sudesh K. Biosynthesis and characterization of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from palm oil products in a Wautersia eutropha mutant. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:1405–1410. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-0690-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mifune J, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Targeted engineering of Cupriavidus necator chromosome for biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from vegetable oil. Can J Chem. 2008;86:621–627. doi: 10.1139/v08-047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riedel SL, Bader J, Brigham CJ, Budde CF, Yusof ZA, Rha C, Sinskey AJ. Production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) by Ralstonia eutropha in high cell density palm oil fermentations. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:74–83. doi: 10.1002/bit.23283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukui T, Abe H, Doi Y. Engineering of Ralstonia eutropha for production of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from fructose and solid-state properties of the copolymer. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3:618–624. doi: 10.1021/bm0255084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Insomphun C, Xie H, Mifune J, Kawashima Y, Orita I, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Improved artificial pathway for biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) with high C6-monomer composition from fructose in Ralstonia eutropha. Metab Eng. 2015;27:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Erb TJ, Berg IA, Brecht V, Muller M, Fuchs G, Alber BE. Synthesis of C5-dicarboxylic acids from C2-units involving crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase: the ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10631–10636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702791104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linster CL, Noel G, Stroobant V, Vertommen D, Vincent MF, Bommer GT, Veiga-da-Cunha M, Van Schaftingen E. Ethylmalonyl-CoA decarboxylase, a new enzyme involved in metabolite proofreading. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:42992–43003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.281527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tsuge T, Watanabe S, Shimada D, Abe H, Doi Y, Taguchi S. Combination of N149S and D171G mutations in Aeromonas caviae polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase and impact on polyhydroxyalkanoate biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2007;277:217–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Volodina E, Raberg M, Steinbuchel A. Engineering the heterotrophic carbon sources utilization range of Ralstonia eutropha H16 for applications in biotechnology. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2016;36:978–991. doi: 10.3109/07388551.2015.1079698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Orita I, Iwazawa R, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Identification of mutation points in Cupriavidus necator NCIMB 11599 and genetic reconstitution of glucose-utilization ability in wild strain H16 for polyhydroxyalkanoate production. J Biosci Bioeng. 2011;113:63–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raberg M, Peplinski K, Heiss S, Ehrenreich A, Voigt B, Doring C, Bomeke M, Hecker M, Steinbuchel A. Proteomic and transcriptomic elucidation of the mutant Ralstonia eutropha G+1 with regard to glucose utilization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:2058–2070. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02015-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sichwart S, Hetzler S, Broker D, Steinbuchel A. Extension of the substrate utilization range of Ralstonia eutropha strain H16 by metabolic engineering to include mannose and glucose. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:1325–1334. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01977-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arikawa H, Matsumoto K, Fujiki T. Polyhydroxyalkanoate production from sucrose by Cupriavidus necator strains harboring csc genes from Escherichia coli W. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2017;101:7497–7507. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8470-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fukui T, Mukoyama M, Orita I, Nakamura S. Enhancement of glycerol utilization ability of Ralstonia eutropha H16 for production of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2014;98:7559–7568. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5831-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mifune J, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Engineering of pha operon on Cupriavidus necator chromosome for efficient biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from vegetable oil. Polym Degrad Stab. 2010;95:1305–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.02.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Biglari N, Ganjali Dashti M, Abdeshahian P, Orita I, Fukui T, Sudesh K. Enhancement of bioplastic polyhydroxybutyrate P(3HB) production from glucose by newly engineered strain Cupriavidus necator NSDG-GG using response surface methodology. 3 Biotech. 2018;8:330. doi: 10.1007/s13205-018-1351-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brigham CJ, Budde CF, Holder JW, Zeng Q, Mahan AE, Rha C, Sinskey AJ. Elucidation of β-oxidation pathways in Ralstonia eutropha H16 by examination of global gene expression. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:5454–5464. doi: 10.1128/JB.00493-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimizu R, Chou K, Orita I, Suzuki Y, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Detection of phase-dependent transcriptomic changes and Rubisco-mediated CO2 fixation into poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) under heterotrophic condition in Ralstonia eutropha H16 based on RNA-seq and gene deletion analyses. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:169. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matsumoto K, Tanaka Y, Watanabe T, Motohashi R, Ikeda K, Tobitani K, Yao M, Tanaka I, Taguchi S. Directed evolution and structural analysis of NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl coenzyme A (acetoacetyl-CoA) reductase from Ralstonia eutropha reveals two mutations responsible for enhanced kinetics. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:6134–6139. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01768-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haywood GW, Anderson AJ, Chu L, Dawes EA. The role of NADH-linked and NADPH-linked acetoacetyl-CoA reductases in the poly-3-hydroxybutyrate synthesizing organism Alcaligenes eutrophus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;52:259–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1988.tb02607.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Segawa M, Wen C, Orita I, Nakamura S, Fukui T. Two NADH-dependent (S)-3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenases from polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing Ralstonia eutropha. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019;127:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fukui T, Chou K, Harada K, Orita I, Nakayama Y, Bamba T, Nakamura S, Fukusaki E. Metabolite profiles of polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing Ralstonia eutropha H16. Metabolomics. 2014;10:190–202. doi: 10.1007/s11306-013-0567-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Q, Luan Y, Cheng X, Zhuang Q, Qi Q. Engineering of Escherichia coli for the biosynthesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyhexanoate) from glucose. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2015;99:2593–2602. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaddor C, Steinbuchel A. Effects of homologous phosphoenolpyruvate-carbohydrate phosphotransferase system proteins on carbohydrate uptake and poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) accumulation in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2011;77:3582–3590. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00218-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simon R, Priefer U, Pühler A. A broad host range mobilization system for in vivo genetic engineering transposon mutagenesis in gram negative bacteria. Bio/Technology. 1983;1:784–791. doi: 10.1038/nbt1183-784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fukui T, Ohsawa K, Mifune J, Orita I, Nakamura S. Evaluation of promoters for gene expression in polyhydroxyalkanoate-producing Cupriavidus necator H16. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:1527–1536. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3100-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kato M, Bao HJ, Kang CK, Fukui T, Doi Y. Production of a novel copolyester of 3-hydroxybutyric acid and medium-chain-length 3-hydroxyalkanaic acids by Pseudomonas sp. 61-3 from sugars. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996;45:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s002530050697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Additional figures and tables.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.