Abstract

Purpose:

Recent studies have suggested the presence of short-T2* signals in the liver, which may confound chemical shift-encoded (CSE) fat quantification when using short echo times (TEs). The purpose of this study was to characterize the liver signal at short echo times and to determine its impact on liver fat quantification.

Methods:

An ultrashort echo time (UTE) CSE-MRI technique and a multi-component reconstruction were developed to characterize short-T2* liver signals. Subsequently, liver fat fraction was quantified using a short-TE (first TE=0.7ms) and UTE CSE-MRI acquisitions, and compared with a standard CSE-MRI (first TE =1.2ms).

Results:

Short-T2* signals were consistently observed in the liver of all healthy volunteers imaged at both 1.5T and 3.0T. At 3.0T, short-T2* signal fractions of 9.6±1.5%, 7.0±1.7% and 7.4±1.7% with T2* of 0.23±0.05ms, 0.20±0.05ms and 0.10±0.02ms were measured in healthy volunteers, patients with liver cirrhotic disease and patients with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis), respectively. For PDFF estimation, 1.7% (P<0.01) and 3.4% (P<0.01) biases were observed in subjects imaged using short-TE CSE-MRI and using UTE CSE-MRI at 1.5T, respectively. The biases were eliminated to 0.4% and −0.7%, respectively, by excluding short echoes less than 1 ms. A 3.2% bias (P<0.01) was observed in subjects imaged using UTE CSE-MRI at 3.0T, which was eliminated to 0.1% by excluding short echoes less than 1 ms.

Conclusions:

A liver short-T2* signal component was consistently observed and was shown to confound liver fat quantification when short echo times were used with CSE-MRI.

Keywords: liver MRI, short T2*, ultrashort TE, chemical shift-encoded, quantitative imaging

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of diffuse liver disease, afflicting an estimated 100 million people in the US alone1, and an estimated 1 billion people world-wide2. Abnormal intracellular accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes, steatosis, is the hallmark and the earliest histological feature of NAFLD. In some patients, steatosis can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), fibrosis, and even cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma3. Thus, accurate quantification of liver fat content is of great interest for early detection and treatment monitoring of NAFLD. MR-based chemical shift encoded (CSE-MRI) techniques enable non-invasive measurement of the proton density fat fraction (PDFF), an established non-invasive biomarker of tissue triglyceride concentration4.

CSE-MRI methods have recently emerged as an accurate and reproducible approach for quantification of PDFF in the liver5–7. The liver signal in gradient-echo images is generally modeled as arising from protons in mobile water and mobile triglycerides. Using prior knowledge of the frequency shifts in the signal model, water and fat can be separated and the signal fraction of each component can be quantified. CSE-MRI methods enable rapid three-dimensional (3D) fat fraction mapping of the whole liver within a single breath-hold, and thus enable a quantitative evaluation of the distribution of liver fat. Advanced CSE-MRI methods correct for multiple confounding factors in the quantification of PDFF, including T1 bias, noise bias, spectral complexity of fat, T2* decay, noise related bias8–10, and phase errors resulting from eddy currents and concomitant gradients11–12.

The majority of multi-echo CSE-MRI acquisition methods are based on Cartesian k-space sampling patterns and are typically utilized with first echo times exceeding 1 ms. There has, however, been increased interest in acquisitions with shorter first echo time achieved using standard Cartesian CSE-MRI acquisitions with lower spatial resolution13 or using non-Cartesian ultra-short TE (UTE) acquisitions14–16. These techniques may enable improved signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and precision of PDFF estimation, as well as reduce artifacts by using motion-robust radial acquisitions.

However, it is unknown whether the liver signal models typically used with standard CSE acquisitions remain valid for acquisitions with short echo times. Indeed, a recent study using Cartesian CSE-MRI at 1.5T demonstrated that the measured liver signal at echo times less than 1 ms was elevated relative to the expected liver signal, resulting in confounded estimates of PDFF using the short-TE CSE-MRI acquisition13. The presence of short-T2* signal components in the liver that are only detectable at short echo times would lead to the elevated signal and the confounded estimation of PDFF in short-TE CSE. Liver signals at short echo times have been measured using UTE imaging17, however, the quantitative MR properties of the signal components have not been characterized. Therefore, characterization of short T2* signal components in the liver is necessary in order to determine their confounding effects on liver PDFF quantification.

In addition, short T2* signal components have been reported to provide potential biomarkers of disease in vivo18–21. In tissues such as skeletal muscles and heart, short T2* signal components have been suggested to correlate with collagen fibers in diseased models18–19. Therefore, characterization of short T2* signal components in the liver for disease detection and staging is also of great interest.

The purpose of this study is to characterize the short T2* signal components of the liver signal, to determine its impact on liver fat quantification and to improve the accuracy of signal modeling in the liver at short echo times at both 1.5T and 3.0T.

Theory

Liver signal model for PDFF quantification

Multiple gradient-echo CSE-MRI is commonly used for confounder-corrected PDFF and T2* quantification in the liver22. The magnitude of the signal S(TEn), without considering signal noise, is generally considered as arising from water and fat, expressed as

| (1) |

where is the nth echo time, W is the signal amplitude of water, F is the sum of the signal amplitudes of P fat peaks with amplitude αp and chemical shift frequencies Δfp, T2* is the relaxation rate of water and fat.

Post-processing these multi-echo signals with correcting confounding factors enables measurement of PDFF , which is defined as

| (2) |

i.e., the ratio of unconfounded proton signal from mobile triglycerides to the unconfounded proton signal from mobile triglycerides and mobile water.

Multi-component liver signal model

At short echo times, short T2* signals in the liver (ST2) are detectable. Signal components with multiple exponentially decaying rates, with different off-resonance frequencies relative to water, or with different T1 relaxation rates may exist, as shown in previous studies in other tissues18–21. To simplify the model in this preliminary study, we hypothesized that ST2 is: 1) mono-exponential signal decay; 2) on resonance with water. T1 relaxation is also not considered. The liver signal S(TEn) is then modified to a multi-component signal model, described as,

| (3) |

where and T2,ζ* are the signal amplitudes and the relaxation rate of ST2, separately.

Estimation of the Signal Fraction and T2* of ST2

In this study, we seek to characterize the MRI properties of ST2, including T2,ζ* and the ST2 fraction, which is defined as,

| (4) |

i.e., the signal fraction of ST2 to all observable signals in the liver. The unknown parameters in the proposed multi-component liver signal model can be estimated by least-squares fitting the magnitude signals,

| (5) |

where is the vector of unknown parameters in Equation 4.

Methods

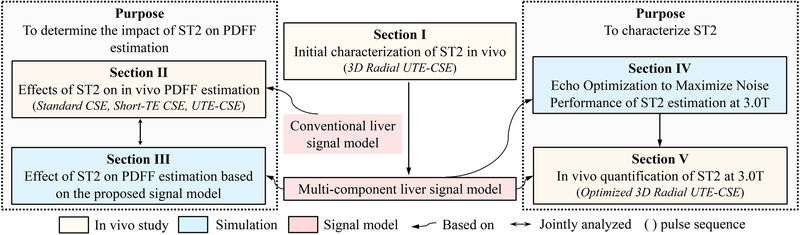

Five sub-studies were performed to characterize ST2 and assess its impact on PDFF, as summarized in the flow diagram in Figure 1. In order to initially characterize ST2, the liver signals at short echo times using a proposed UTE-CSE MRI acquisition were obtained in healthy volunteers at 1.5T and 3.0T (Section I). The feasibility of the proposed multi-component liver signal model and the approximate MRI properties of ST2 were inspected using the in vivo liver signals. In order to assess the effects of ST2 on the accuracy of PDFF estimation at short echo times, we performed in vivo CSE acquisitions for PDFF estimation at 1.5T and 3.0T (Section II). In order to further validate the impact of ST2 on PDFF estimation, a simulation was performed at 1.5T and 3.0T based on the proposed signal model (Sections III) and jointly analyzed with in vivo results in Section II. In order to provide preliminary quantification of the ST2 signals, we optimized echo times used in the proposed UTE-CSE using simulations (Section IV) and performed in vivo validation studies at 3.0T (Section V).

Figure 1.

The flow diagram of the five experiments in this work, including three sets of in vivo studies (yellow boxes) and two sets of simulations (blue boxes) under the two purposes of this work. A multi-component liver signal model (red box), which was based on the observed in vivo results in Section I, was proposed and used as the signal model in Sections III, IV and V. The conventional liver signal model was used in Sections II. MRI pulse sequence used in each of the three in vivo studies were listed in the parentheses.

All in vivo studies were HIPAA compliant and were approved by the local Institutional Review Board (IRB). Healthy subjects and patients were recruited and imaging was performed after obtaining informed written consent. Exclusion criteria included subjects with iron overload, subjects injected with gadolinium-based contrast agent within the past two weeks, or subjects ever injected with ferumoxytol-based contrast agent, in order to avoid any potential confounding effects on measurements of ST2. MR images were obtained on clinical 1.5T MRI systems (Signa HDxt and Optima MR450w, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) and a clinical 3.0T MRI system (Discovery MR 750, GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI).

Given that the PDFF estimation using CSE-MRI is sensitive to phase errors especially at short echo times23, the magnitude of signals was used in estimation of in vivo PDFF and quantification of ST2 signals. However, using the complex signals has gained increased attention due to better noise performance. Therefore, we also analyzed the PDFF estimation in simulations (Sections III) with the liver complex signal model given in the Supporting Information.

I. Initial characterization of ST2 in vivo

In order to perform initial characterization of ST2, healthy subjects were recruited and imaged at 1.5T and 3.0T using 3D radial UTE-CSE15–16 with a multi-echo acquisition. Raw data were acquired during end expiration using a previously described adaptive respiratory compensation method, with a 50% acceptance window16. A minimum phase Shinnar-Le Roux radiofrequency pulse16 with a duration of 112 μs and bandwidth of 50 kHz was used for selective excitation. A single echo was acquired after each radiofrequency excitation for each TR, using real time randomization of the echo times to reduce the effects of eddy currents21. The same radial k-space trajectory was sampled at multiple echo times in a randomized order to minimize motion related artifacts16. 10,000 radial projections were sampled for each echo. Other imaging parameters are listed in Table 1. In addition, a MnCl2-doped water phantom with a known PDFF of 0% was imaged at 1.5T and 3.0T, using the same in vivo UTE-CSE acquisitions, to assess the signal fluctuation in UTE acquisitions21.

Table 1.

Imaging parameters of CSE acquisitions and study cohorts of the three in vivo studies.

| Cohorts | # TE |

TE (ms) |

TR (ms) |

FA (°) |

ACQ resolution(mm3) | Scan Time |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Section I Initial characterization of ST2 in vivo |

Healthy (N=6 at 1.5T, N=6 at 3.0T) |

1.5T & 3.0T | ||||||

| Radial UTE-CSE | 11 | 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0 | 8.7 | 4 | 1.2×1.2×1.2 | ~30 mins (FB) | ||

| Section II Effect of ST2 on in vivo PDFF estimation |

1.5T | |||||||

| Healthy (N=14⨉) Steatosis (N=5) |

Standard CSE | 6 | TEinit/ΔTE = 1.2/2.0 | 14.5 | 5 | 1.6×2.3×8 or 2.1×2.8×8 | 21 s (BH) | |

| Short-TE CSE | 6 | TEinit/ΔTE = 0.7/1.3 | 8.6 | 5 | 1.3×1.9×8 or 3.7×2.7×10 | 19 s (BH) | ||

| Healthy (N=6⨉) | Radial UTE-CSE | 11 | 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0 | 8.7 | 4 | 1.2×1.2×1.2 | ~30 mins (FB) | |

| Healthy (N=6⨉) Steatosis (N=5) Cirrhosis (N=5) |

3.0T | |||||||

| Standard CSE | 6 | TEinit/ΔTE = 1.2/1.0 | 8.0 | 3 | 1.6×2.2×8 | 18 s (BH) | ||

| Short-TE CSE | 8 | TEinit/ΔTE = 0.6/1.0 | 8.0 | 3 | 2.8×2.5×8 | 17 s (BH) | ||

| 11 | 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, 0.25, 1.0,2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0 | 9.6 | 4 | 1.6×1.6×1.6 | ~35 mins (FB) | |||

| Radial UTE-CSE | or | |||||||

| 11 | 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8,1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0 | 8.7 | 4 | 1.6×1.6×1.6 | ~30 mins (FB) | |||

| Section V In vivo quantification of ST2 at 3.0T |

Healthy (N=6⨉) Steatosis (N=5+) Cirrhosis (N=5⧺) |

3.0T | ||||||

| Optimized UTE-CSE | 11 | 0.10, 0.15, 0.20, 0.25, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0 | 9.6 | 4 | 1.6×1.6×1.6 | ~35 mins (FB) |

Data from the same 6 healthy subjects imaged at 1.5T in Section I;

Data from the same 5 patients with steatosis imaged at 3.0T in Section II;

Data form the same 5 patients with cirrhosis in Section II; UTE: ultrashort TE; CSE: chemical shift-encoded; FA: flip angle; ACQ: acquisition; BW: bandwidth; FB: free-breathing; BH: breath-held

UTE-CSE images were reconstructed offline using an adaptive coil combination technique24. The liver signals were measured in a ~3.5 cm2 circular region-of-interest (ROI) in the right lobe of the liver placed to avoid large blood vessels and bile ducts. The magnitude signal was averaged first and then fit to the proposed multi-component liver signal model (Equation 7) to estimate the ST2 fraction and T2,ζ*.

II. Effect of ST2 on in vivo PDFF estimation

In order to assess the effect of ST2 on the accuracy of PDFF estimation at short echo times, healthy subjects and patients with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis) were recruited and imaged at 1.5T and 3.0T using three CSE-MRI acquisitions with different echo time combinations. Two single-breath-hold 3D CSE-MRI Cartesian acquisitions with relatively long echo times (Standard CSE) and with a short initial echo time (Short-TE CSE), and a free-breathing radial UTE-CSE acquisition were obtained. The acquisition trajectory and respiratory gating were the same as in the UTE-CSE in Section I. Imaging parameters of the three CSE-MRI acquisitions are listed in Table 1. A single-voxel multi-TE stimulated echo acquisition mode (STEAM) MR spectroscopy25 (MRS) acquisition was also obtained as the reference for a T2-corrected T1-independent PDFF estimate. Imaging parameters of STEAM-MRS included: prescribed within the right lobe of the liver to avoid large vessels or bile ducts and the dome of the liver, five echoes with TEinit/ΔTE = 10/5 ms, 3500 ms TR, 20×20×20 mm3 or 24×24×24 mm3 voxel size, 1 average, ±2.5 kHz spectral width, 2048 readout points, and 5 ms mixing time.

PDFF was calculated twice in each CSE acquisition using a CSE reconstruction6, either with all echoes or excluding short echoes (<1 ms). PDFF was quantified by measuring the average PDFF in the ROI co-localized with the MRS voxel. Measurements of PDFF made with CSE-MRI and MRS were compared using Bland-Altman analysis. In addition, PDFF was also estimated in the UTE-CSE acquisition of the MnCl2-doped water phantom in Section I to assess bias on PDFF estimation due to signal fluctuations in UTE acquisitions21.

III. Effect of ST2 on PDFF estimation based on the proposed signal model

The effects of ST2 on PDFF estimation depend on the signal fraction of ST2, the relaxation time T2,ζ*, the chemical shift frequency of the fat at different field strengths, and also the choice of echo times. We performed simulation to jointly analyze the bias on PDFF introduced by the presence of ST2 at 1.5T and 3.0T, along with the in vivo study in Section II. We estimated PDFF and compared with the true PDFF, using signals including ST2 (Equations 3 and 4). The simulation parameters include: six-peak fat spectrum27 with frequency shift = [0.6, −0.5, −1.95, −2.6, −3.4, −3.8] ppm and relative amplitude = [4.7, 3.9, 0.6, 12, 70, 8.8]%, T2* = 25 ms for both water and fat, PDFF = [0%, 10%], T2,ζ* = 0.01~1.00 ms, ST2 fraction = 10% retrospectively used based on the preliminary in vivo estimation in Section I, and no noise. Echo times of three combinations from in vivo acquisitions in Section II were used: 1) Standard CSE: six echoes, TEinit/ΔTE = 1.2/2.0 ms; 2) Short-TE CSE: six echoes, TEinit/ΔTE = 0.7/1.3 ms; 3) UTE-CSE: eleven echoes, TE = [0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0] ms. The signal at each echo was generated using Equations 3 and 4. PDFF was then estimated using Equations 1 and 2 and compared with the true PDFF.

IV. Echo Time Optimization to Maximize Noise Performance of ST2 estimation at 3.0T

Optimization of echo times has been shown to improve the noise performance of quantitative estimates in CSE-MRI techniques26. In this work, echo times were optimized to reduce minimize the maximum bias and the maximum root-mean-square error (RMSE) of the estimated ST2 fraction and R2,ζ* (R2,ζ*=1/ T2,ζ*) over the combinations within a range of ST2 fraction and T2,ζ*. A Monte-Carlo simulation with 1000 trials was used with parameters including: T2,ζ* = 0.20–0.33 ms, ST2 fraction = [5.0, 10.0, 15.0]%, PDFF = [0, 10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 40.0]%, T2* = 50 ms. The ranges of T2,ζ* and the ST2 fraction were retrospectively chosen based on our preliminary in vivo estimation at 3.0T described in Section I above. A SNR of 200 was used, which was similar to the SNR measured using the ROI-based approach (i.e., signal average first and then fit) with the in vivo data as stated in Section I. An upper bound of 1.25 ms and a lower bound of 0.07 ms were applied on T2,ζ* estimation to stabilize the estimation process.

Eleven echo images were acquired to restrict acquisition time within 40 minutes. The potential choices of echo time combinations were narrowed down in this work with the following constraints: 1) eleven echoes were divided into two groups, one with short echo times (<1 ms) for capturing ST2 signals, one with relative long echo times (≥1 ms) for quantifying water and fat, 2) echo spacing was kept the same in individual echo time groups, 3) the first echo time in short echo time group was fixed to be the minimum echo time achievable with the pulse sequence (TE0 = 100 us), 4) the first echo time in the long echo time group was fixed to be 1 ms, which is a standard first echo time used for liver CSE imaging at 3.0T. The four terms lead to an echo time combination,

| (6) |

where ΔTEs (0.02 ms ≤ ΔTEs ≤ 0.23 ms) and ΔTEl (0.5 ms ≤ ΔTEl ≤ 1.5 ms) are the echo spacing in short and long echo time groups, respectively, N (3 ≤ N ≤ 7) is the number of short echo times.

V. In vivo quantification of ST2 at 3.0T

In order to investigate whether ST2 might correlate with the presence of liver disease, especially collagen fibers as has been found in diseased models of other tissues18–19, we preliminarily quantified the signal fraction and T2* of ST2 and compared the quantification between healthy and cirrhotic livers. Three cohorts consisting of healthy subjects, patients with liver cirrhosis, and patients with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis) were recruited and imaged at 3.0T using a 3D UTE-CSE acquisition with the optimized echo times in simulation (Section V). The acquisition trajectory and respiratory gating were the same as in the UTE-CSE in Section I. Imaging parameters are listed in Table 1. The liver signals were measured and the ST2 fraction and T2,ζ* were estimated in the same way as that in Section I. The average values of the ST2 fraction and T2,ζ* in three cohorts were compared. The P value was calculated by using a two-tailed Mann-Whitney U test, and P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

I. Initial characterization of ST2 in vivo

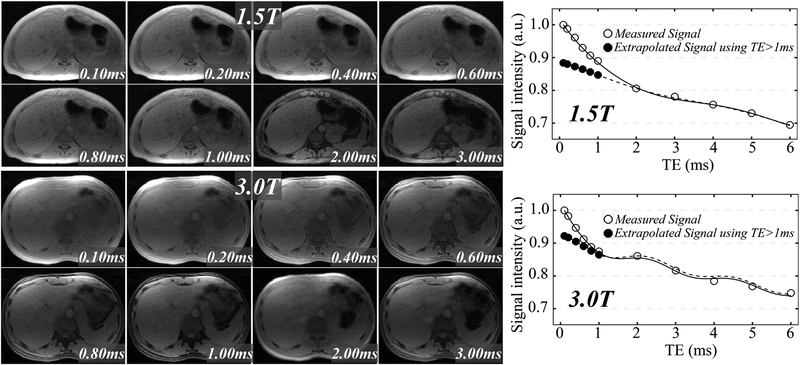

Six healthy subjects were recruited and imaged at 1.5T and 3.0T. Figure 2 shows the UTE-CSE images and plots of the liver signal intensity of two different healthy subjects at 1.5T (top) and 3.0T (bottom). No obvious motion artifacts are shown in the UTE multi-echo images. The measured liver signals at echo times less than 1 ms (hollow circles) are elevated and show faster decay rate than the signals at echo times larger than 1 ms, compared with the extrapolated signals of water and fat from Equation 2 using echo times larger than 1 ms (solid circles). In the MnCl2-doped water phantom, the measured signals at short echo times less than 1ms are not elevated in the UTE-CSE acquisition (Supporting Information Figure S1), demonstrating that the elevated liver signal at short echoes originate from the tissue itself and not from acquisition artifacts.

Figure 2.

The liver signal of two different healthy volunteers at multiple echo times in UTE-CSE imaging (upper left: 1.5T, lower left: 3.0T) shows dramatically faster decaying rate at echo times less than 1ms than the decaying rate of water and fat signals echo times larger than 1ms at both 1.5T (upper right) and 3.0T (lower right), suggesting the presence of an unknown liver signal component with a short T2* value. A ST2 fraction of 17.3%, a T2, ζ* of 0.87 ms, a fat fraction of 0.8% and a T2* of 39.0 ms were estimated in the subject at 1.5T based on the proposed liver signal model (Equation 2). A ST2 fraction of 10.5%, a T2, ζ* of 0.53 ms, a fat fraction of 1.9% and a T2* of 33.0 ms were estimated in the subject at 3.0T based on Equation 2.

In the six volunteers as shown in Table 2, a ST2 fraction of 9.6±1.8% with a T2, ζ* of 0.21±0.08 ms were observed at 3.0T, and a ST2 fraction of 14.2±1.1% with a T2, ζ* of 0.80±0.24 ms were observed at 1.5T. The ST2 fraction of subjects estimated at 1.5T are all higher than that estimated at 3.0T with P<0.01. T2,ζ* at 1.5T are all longer than that at 3.0T with P<0.01.

Table 2.

Subjects information and the estimation of the ST2 signals at 1.5T and 3.0T.

| Subject ID | Gender | Age (year) |

Cirrhosis Stage |

ST2 Fraction 3.0T Optimized TE+ (%) | T2, ζ* 3.0T+ (ms) |

ST2 Fraction 3.0T⨉ (%) |

T2, ζ* 3.0T⨉ (ms) |

ST2 Fraction 1.5T⨉ (%) | T2, ζ* 1.5T⨉ (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP1 | F | 55 | A | 5.8 | 0.25 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CP2 | M | 57 | B | 4.9 | 0.13 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CP3 | M | 60 | A | 9.3 | 0.16 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CP4 | F | 70 | B | 7.7 | 0.24 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| CP5 | F | 51 | B | 7.4 | 0.23 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| mean±std | 7.0±1.7 | 0.20±0.05 | |||||||

| FP1 | F | 59 | N/A | 5.5 | 0.08 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| FP2 | M | 58 | N/A | 9.1 | 0.10 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| FP3 | F | 29 | N/A | 6.3 | 0.10 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| FP4 | M | 57 | N/A | 8.6 | 0.13 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| mean±std | 7.4±1.7 | 0.10±0.02 | |||||||

| H1 | F | 23 | N/A | 10.7 | 0.25 | 11.0 | 0.29 | 14.0 | 0.99 |

| H2 | M | 39 | N/A | 7.3 | 0.14 | 7.6 | 0.11 | 13.8 | 0.48 |

| H3 | M | 33 | N/A | 9.2 | 0.23 | 7.0 | 0.16 | 15.2 | 0.65 |

| H4 | F | 26 | N/A | 10.7 | 0.28 | 11.1 | 0.32 | 15.9 | 1.14 |

| H5 | M | 31 | N/A | 11.2 | 0.22 | 10.3 | 0.18 | 13.2 | 0.67 |

| H6 | F | 26 | N/A | 8.6 | 0.23 | 10.9 | 0.23 | 13.3 | 0.84 |

| mean±std | 9.6±1.5 | 0.23±0.05 | 9.6±1.8 | 0.21±0.08 | 14.2±1.1 | 0.80±0.24 |

Data in Section I;

Data in Section V; CP, patient with diagnosed cirrhotic liver disease; FP, patient with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis); F, female; M, male; H, healthy volunteer; N/A, not available; std, standard deviation

II. Effect of ST2 on in vivo PDFF estimation

Fourteen healthy subjects and five patients with suspected hepatic steatosis were recruited and imaged at 1.5T, and six healthy subjects, five patients with suspected liver cirrhosis and five patients with hepatic steatosis were recruited and imaged at 3.0T. Portions of the data at 1.5T have been previously reported13. At 1.5T, six healthy subjects out of the fourteen healthy subjects were imaged with 3D radial UTE-CSE.

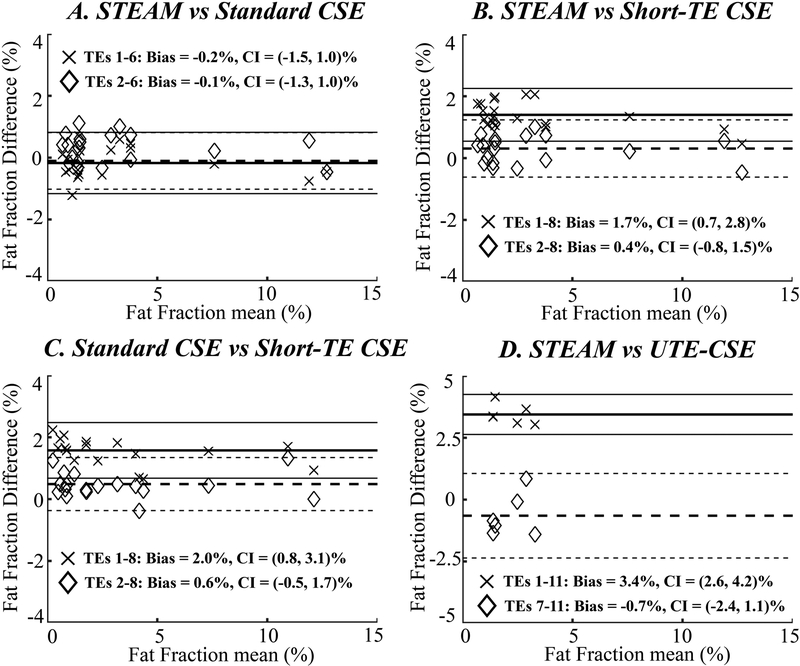

The plots of the liver signal intensity of a healthy subject acquired in standard CSE and short-TE CSE acquisitions at 1.5T are shown in Supporting Information Figure S2. Figures 3 and 4 depict the Bland-Altman analysis of fat quantification using CSE-MRI compared to MRS at 1.5T and 3.0T, respectively.

Figure 3.

At 1.5T, Bland-Altman analysis on PDFF estimation shows a positive bias of the estimated PDFF using all echoes in both short-TE CSE (“×” in B and C) and UTE-CSE (“×” in D) and can be eliminated by discarding the short echoes (diamond in B and D). The fat estimation is accurate using standard CSE using all six echoes or when the first echo is discarded (A).

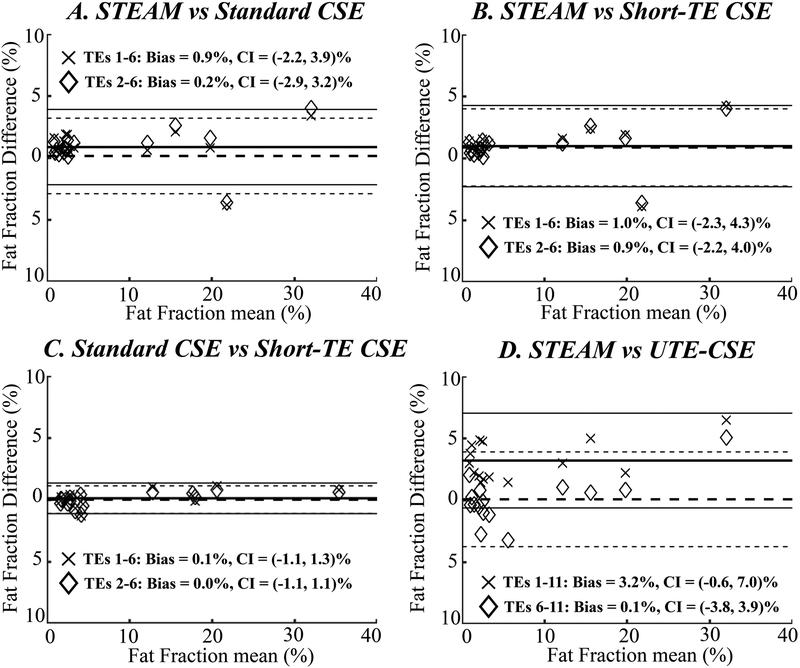

Figure 4.

At 3.0T, Bland-Altman analysis on PDFF estimation shows a positive bias of the estimated PDFF using all echoes in UTE-CSE (“×” in D) and can be eliminated by discarding the short echoes (diamond in D), while the accuracy of the estimated PDFF in short-TE CSE is not improved by discarding the short echoes (B and C). In standard CSE (A), a small bias is observed and reduced in standard CSE using all six echoes and when the first echo is discarded, respectively.

At 1.5T, PDFF estimation is accurate using all six echoes or when the first echo is discarded in standard CSE (Figure 3A). A 1.7% positive bias of the estimated PDFF (P<0.01) is observed when all echoes are used in short-TE CSE (“×” in Figures 3B and 3C). This bias can be reduced by discarding the first echo in short-TE CSE (diamond in Figures 3B and 3C). In addition, a 3.4% positive bias of the estimated PDFF (P<0.01) is observed in UTE-CSE using all echoes (“×” in Figure 3D) and the bias can be reduced by discarding the short echoes (diamond in Figure 3D).

At 3.0T, however, the PDFF estimation in short-TE CSE is not significantly different when all echoes are used or when the first echo is discarded (Figures 4B and 4C). A bias of 0.9%, respect to PDFF estimated in STEAM-MRS, is observed and reduced to 0.2% in standard CSE using all six echoes and when the first echo is discarded, respectively (Figure 4A). In UTE-CSE, a 3.2% positive bias of the estimated PDFF (P<0.01) is also observed using all echoes (“×” in Figure 4D) and the bias can be reduced by discarding the short echoes (diamond in Figure 4D).

In the MnCl2-doped water phantom, the estimated PDFF is 0.01% at 1.5T and −0.06% at 3.0T using all echoes, and 0.05% at 1.5T and 0.33% at 3.0T discarding the short echoes in UTE-CSE (Supporting Information Figure S3). It demonstrates that the bias of the estimated in vivo PDFF using all echoes in UTE-CSE is due to factors other than eddy currents, and originates from short echo time signals from the tissue itself.

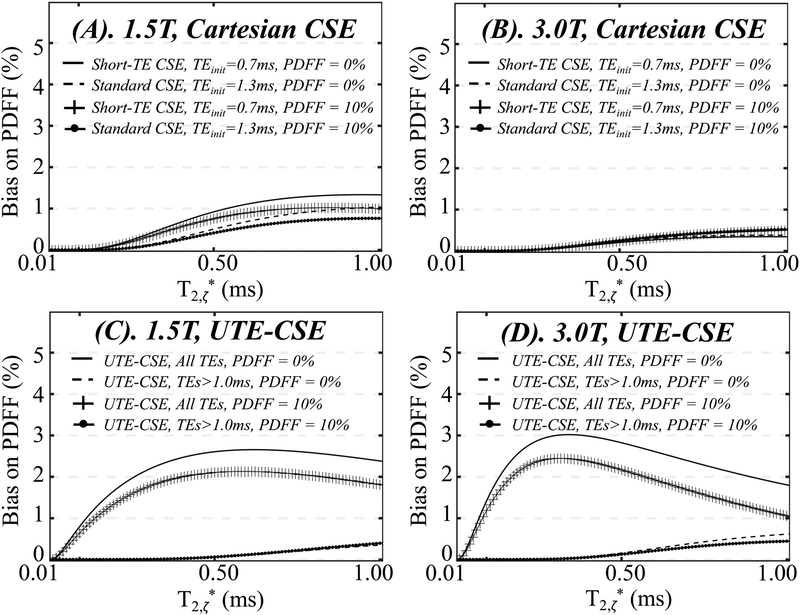

III. Effect of ST2 on PDFF estimation based on the proposed signal model

Figure 5 shows the simulation results of the bias on PDFF with a true PDFF of 0% (solid lines and dashed lines) or 10% (lines with cross and solid circles) at 1.5T (Figure 5A, 5C) and 3.0T (Figure 5B, 5D) in the presence of ST2 with a fraction of 10%. Using standard CSE and short-TE CSE (Figure 5A, 5B), the bias in PDFF estimates increases as T2,ζ* increases at both 1.5T and 3.0T, i.e., when the ST2 signals decay slower, leading to more residual signals at longer echo times used for water and fat estimation. At 1.5T, the bias is eliminated when estimating PDFF using long echo times, i.e., standard CSE (dashed lines and lines with solid circles), compared to the estimations using short echo times, i.e., short-TE CSE (solid lines and lines with cross). At 3.0T, however, the bias in standard CSE and short-TE CSE is smaller than that at 1.5T for a given T2,ζ*. Moreover, the bias in standard CSE (dashed lines and lines with solid circles) is not substantially reduced compared to the short-TE CSE (solid lines and lines with cross).

Figure 5.

In simulation, the bias on PDFF estimation due to the presence of ST2 with a signal fraction of 10% is apparent in Short-TE CSE at 1.5T (A) and UTE-CSE at both 1.5T and 3.0T (C and D). The bias is reduced in estimations using only long echo times, i.e, Standard CSE at 1.5T (A) or UTE-CSE with echo times larger than 1ms at both field strengths (C and D). The bias is not obvious in Short-TE CSE or Standard CSE at 3.0T (B).

In UTE-CSE (Figure 5C and 5D), the bias on PDFF is observed using all echo times (solid lines and lines with cross) and can be substantially reduced in the estimations using echo times longer than 1 ms (dashed lines and lines with solid circles). The effects of ST2 on PDFF estimation based on the complex signal model is shown in Supporting Information Figure S4.

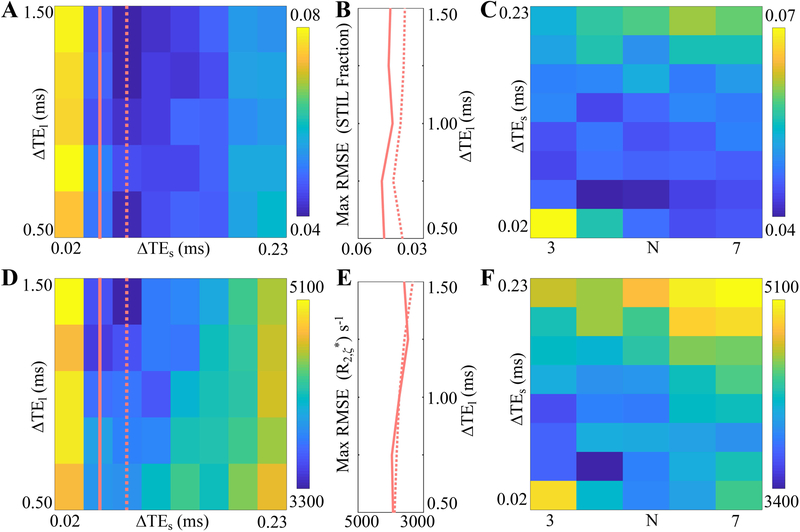

IV. Echo Time Optimization to Maximize Noise Performance of ST2 estimation at 3.0T

Figure 6 shows the maximum RMSE of the ST2 fraction (A, B, C) and R2,ζ* (D, E, F) in the Monte-Carlo simulation. Figures 6A and 6D show the maximum RMSE with varying echo spacing ΔTEs and ΔTEl at number of short echo times N equal to 4. Figures 6C and 6F shows the maximum RMSE with varying echo spacing ΔTEs and numbers of short echo times N at echo spacing of long echo times ΔTEl equal to 1.0 ms.

Figure 6.

At 3.0T, Monte-Carlo simulation at a SNR of 200 shows that the maximum RMSE of the ST2 fraction (A, B, C) and R2, ζ* (D, E, F, unit: s−1) is reduced at echo spacings ΔTEs=0.05 ms and ΔTEl=1.0 ms, and number of short echo times N=4. The maximum RMSE increases when ΔTEs>0.08 ms or ΔTEs<0.05 ms, and decreases when ΔTEs>0.75 ms at number of short echo times N equal to 4 (A, D). The influence of ΔTEl on the maximum RMSE is small when ΔTEl is in the range of 1.0 ms to 1.5 ms at ΔTEs=0.05 ms (solid line) and 0.08 ms (dashed line), as shown in (B) and (E), the profiles of the second and third columns in (A) and (D). A ΔTEl of 1 ms is used to thus reduce the acquisition time, and the maximum RMSE at ΔTEl =1 ms (C, F) is minimized at ΔTEs =0.05 ms and N=4.

In Figures 6A and 6D, maximum RMSE is large when ΔTEs is either shorter than 0.02 ms or longer than 0.2 ms, and increase as ΔTEs increases from 0.08 ms to 0.23 ms. Maximum RMSE decreases as ΔTEl increases in the range of 0.5 ms to 1.5 ms. Figures 6B and 6E delineate the second and third columns in Figures 6A and 6D, describing RMSE at ΔTEs=0.05 ms (solid line) and 0.08 ms (dashed line). The influence of ΔTEl on the maximum RMSE is small when ΔTEl is in the range of 1.0 ms to 1.5 ms. A ΔTEl of 1.0 ms is thus used to shorten TR, so as to reduce the acquisition time. In Figures 6C and 6F, maximum RMSE is shown to increase when N increases from 4 to 7. The lowest maximum RMSE is obtained at a N of 4 and a ΔTEs of 0.05 ms.

According to the RMSE results, the optimized echo times are four ultrashort echo times starting with the 100 us and having an echo spacing of 0.05 ms, and seven relatively long echo times starting with 1.0 ms and having an echo spacing of 1.0 ms. Moreover, the maximum bias at different echo time combinations follows a similar trend as the maximum RMSE. Consequently, the optimized echo times also favor minimizing the maximum bias of the ST2 fraction and T2,ζ*. The actual echo times were rounded up to the closest feasible time for UTE MRI, i.e., TE = [0.10, 0.15, 0.20, 0.25, 1.00, 2.00, 3.00, 4.00, 5.00, 6.00, 7.00] ms.

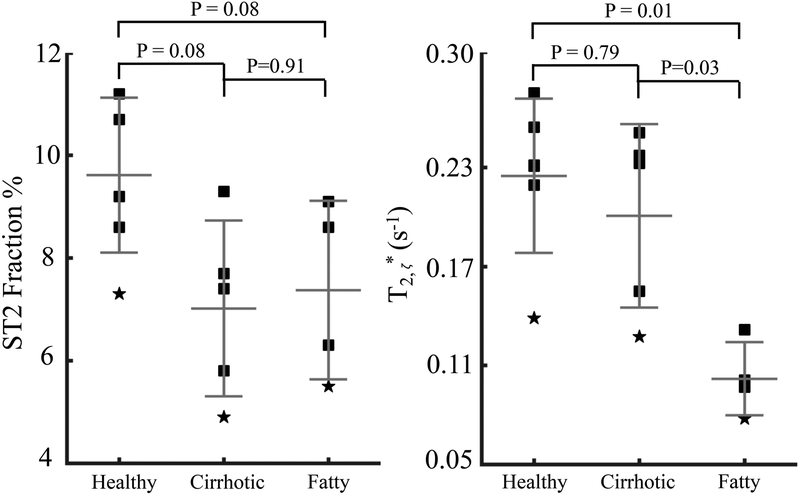

V. In vivo quantification of ST2 at 3.0T

The six healthy subjects imaged with radial UTE-CSE, the five patients with liver cirrhosis and five patients with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis) imaged at 3.0T in Section II were also imaged using the optimized UTE-CSE at 3.0T. The UTE-CSE data of one patient with hepatic steatosis were excluded because of excessive motion-related artifacts.

The plot of the liver signal intensity of a healthy subject is shown in Supporting Information Figure S5. The estimated ST2 fractions of all subjects are above 4.9% as shown in Table 2, demonstrating the consistent existence of the ST2 in the liver in different human cohorts. The ST2 fraction in the five patients with liver cirrhosis and the four patients with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis) are 7.0±1.7% and 7.4±1.7%, respectively, compared to 9.6±1.5% in healthy subjects, although the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.08) as shown in Figure 7. T2,ζ* of 0.20±0.05 ms in patients with liver cirrhosis is not significantly different from that of 0.23±0.05 ms in healthy volunteers (P=0.79), while T2,ζ* of 0.10±0.02 ms in patients with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis) is significantly lower than that in healthy volunteers (P=0.01) and in patients with liver cirrhosis (P=0.03).

Figure 7.

At 3.0T, the ST2 fraction (left) and T2, ζ* (right) of six healthy volunteers, five patients with liver cirrhosis and four patients with hepatic steatosis (but no cirrhosis) estimated in the proposed optimized UTE-CSE acquisitions.

Discussion

In this work, we have demonstrated the consistent presence of ST2 in the liver of healthy subjects, patients with liver cirrhosis and patients with hepatic steatosis by using a proposed UTE-CSE acquisition. In addition, we have demonstrated the presence of the ST2 signals leads to bias on liver fat quantification using CSE-MRI acquisition with short echo times.

The ST2 signal fraction that is preliminarily quantified at 3.0T is not significantly different between healthy subjects and patients with liver cirrhosis, suggesting that the origin of the ST2 signal may not be related to collagen tissue content, as patients with cirrhosis are expected to have a four- to sevenfold increase in collagen content28. In healthy volunteers who were imaged at both 3.0T and 1.5T, a longer T2,ζ* was estimated at 1.5T compared to the estimation at 3.0T in the same subject. Although higher SNR may be achieved at 3.0T, the shorter T2,ζ* may limit SNR benefit at 3.0T and affect the accuracy of the ST2 quantification, potentially leading to the discrepancy of the ST2 fractions estimated in the same subject at two field strengths.

The elevated in vivo liver signals at short echo times relative to the expected liver signal and the presence of bias in PDFF demonstrated that ST2 signals impact reproducibility of CSE fat quantification if unaccounted for. The confounding effects of the ST2 signals on liver fat quantification in Cartesian CSE using short echo times at 3.0T is not apparent in vivo, compared to the effects at 1.5T. The faster decay of in vivo ST2 signals at 3.0T, indicated by the shorter T2,ζ*, may result in reduced bias on PDFF compared to that with a longer T2,ζ* at 1.5T, as shown in simulations. Furthermore, the water and fat signals at the short initial echo time (0.6~0.7 ms) are closer to in-phase at 1.5T compared to that at 3.0T due to the difference of water-fat chemical shift frequencies. Therefore, the same amount of signal elevation due to ST2 potentially results in a larger error on PDFF estimation at 1.5T, as shown in simulation.

In addition to PDFF estimation, R2* (1/T2*) can be obtained from CSE-MRI acquisitions as a biomarker for liver iron overload29–30. UTE-based R2* mapping has been proposed for quantifying liver iron overload but has not considered the effect of ST2 on R2* estimation31–32. It is possible that the presence of ST2 signals may confound R2* quantification if not included in the liver signal model at short echo times. Further analysis of this effect is required in future studies.

This study has several limitations. First, patients with a broader range of PDFF need to be studied at 1.5T to evaluate the bias of PDFF estimation using short echo times less than 1 ms. In addition, echo time optimization for the ST2 quantification and the ST2 quantification of patients with liver cirrhosis were performed only at 3.0T in this study. The relatively long T2,ζ* at 1.5T, compared to the study at 3.0T in this work, may potentially benefit the ST2 quantification at 1.5T. Optimization of the echo times in UTE-CSE and patient studies at 1.5T are needed in the future. Further, we note that an ROI-based (i.e., signal average first and then fit) magnitude fitting was used in this work in order to estimate the fast decaying signals of ST2 with high SNR and also to avoid the effects of phase errors in the complex data. A homogenous distribution of ST2 in the liver was assumed, although the validity of this assumption is unknown. In future studies, the high spatial resolution used with 3D UTE-CSE in this study may not be necessary and could be reduced to increase SNR and shorten scan time.

In addition, since the T1 value of ST2 is unknown, it is possible that the images may be slightly T1-weighted such that the signal fraction of ST2 may contain T1 bias and may not represent a true proton density fraction. Therefore, the signal fraction may be affected by acquisition parameters that impact T1 weighting, specifically TR and flip angle. The potential T1 bias may also lead to the discrepancy of the ST2 fractions estimated in the same subject at two field strengths since T1 is field strength dependent.

Exact quantification of short T2* signal component is challenging and may be biased by UTE-CSE MRI technique. For example, the radiofrequency pulse duration is known to confound short T2 excitation, due to appreciable relaxation during the excitation33. In this work, we utilized a short duration, high bandwidth pulse to minimize potential excitation errors. However, a higher level of accuracy may be achievable in future studies using a Bloch equation-modeled method33. As a further limitation, systematic bias in UTE-CSE MRI can arise from eddy currents and receiver switching fidelity. These effects were evaluated in phantoms but may be sensitive to tissue relaxation properties and patient setup.

Further, the signal model of ST2 proposed in this work is empirical, i.e., based on our preliminary in vivo observations and also from previous studies in other tissues that model the short T2* signal as a mono-exponential, on-resonance signal decay. However, the accuracy of this signal model requires further validation. Ex-vivo human liver or small animal NMR experiments may be performed in the future to identify the exact ST2 signal component and improve the signal modeling of the liver. Moreover, echo times used in the ST2 quantification were optimized in simulation following several constrains based on the assumed signal model as well as the preliminarily quantified ST2 fraction and T2*. The first echo time in the long echo time group, where the ST2 signals were assumed to have decayed away, could be further optimized in the future based on the ST2 quantification of the larger population in this study.

Conclusions

We have described and provided preliminarily quantification of the signal fraction and T2* of a liver short T2* signal component in different human cohorts, and have demonstrated the consistent presence of this signal in vivo. Importantly, quantification of liver PDFF is confounded by ST2 when short echo times are used in CSE-MRI. Future studies are needed to further characterize the MRI properties of ST2, to identify its origin, and to develop strategies that mitigate its impact on liver PDFF quantification using CSE-MRI.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support of the NIH (R01-DK088925, R01-DK100651, R01-DK083380, R01-DK117354, R01-HL136965, K24-DK102595 and U01-HD087216), as well as GE Healthcare who provides research support to University of Wisconsin-Madison. The authors also gratefully acknowledge David T. Harris, Ph.D. who provided assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA 2015; 313:2263–2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loomba R, Sanyal AJ. The global NAFLD epidemic. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013; 10:686–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Preiss D, Sattar N. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an overview of prevalence, diagnosis, pathogenesis and treatment considerations. Clin Sci (Lond) 2008; 115:141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reeder SB, Hu HH, Sirlin CB. Proton density fat-fraction: A standardized mr-based biomarker of tissue fat concentration. J Magn Reson Imaging 2012; 36:1011–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kühn JP, Hernando D, Mensel B, Krüger PC, Ittermann T, Mayerle J, Hosten N, Reeder SB. Quantitative chemical shift-encoded MRI is an accurate method to quantify hepatic steatosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014; 39:1494–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeder SB, Cruite I, Hamilton G, Sirlin CB. Quantitative assessment of liver fat with magnetic resonance imaging and spectroscopy. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 34:729–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yokoo T, Serai SD, Pirasteh A, Bashir MR, Hamilton G, Hernando D, Hu HH, Hetterich H, Kühn JP, Kukuk GM, Loomba R. Linearity, bias, and precision of hepatic proton density fat fraction measurements by using MR imaging: a meta-analysis.Radiology 2017; 286:486–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu CY, McKenzie CA, Yu H, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. Fat quantification with IDEAL gradient echo imaging: correction of bias from T1 and noise. Magn Reson Med 2007; 58:354–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hines CD, Frydrychowicz A, Hamilton G, Tudorascu DL, Vigen KK, Yu H, McKenzie CA, Sirlin CB, Brittain JH, Reeder SB. T1 independent, T2* corrected chemical shift based fat-water separation with multi-peak fat spectral modeling is an accurate and precise measure of hepatic steatosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 33:873–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hernando D, Sharma SD, Kramer H, Reeder SB. On the confounding effect of temperature on chemical shift-encoded fat quantification. Magn Reson Med 2014; 72:464–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colgan TJ, Hernando D, Sharma SD, Reeder SB. The effects of concomitant gradients on chemical shift encoded MRI. Magn Reson Med 2016; 78:730–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruschke S, Eggers H, Kooijman H, et al. Correction of phase errors in quantitative water-fat imaging using a monopolar time-interleaved multi-echo gradient echo sequence. Magn Reson Med 2017; 78:984–996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernando D, Motosugi U, Reeder SB. Bias in liver fat quantification using chemical shift-encoded techniques with short echo times In: Proceedings of the 23rd Annual Meeting of the ISMRM, Toronto, Canada: 2015:337. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Armstrong T, Dregely I, Stemmer A, et al. Free-breathing liver fat quantification using a multiecho 3D stack-of-radial technique. Magn Reson Med. 2018; 79:370–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bauman G, Johnson KM, Bell LC, Velikina JV, Samsonov AA, Nagle SK, Fain SB. Three-dimensional pulmonary perfusion MRI with radial ultrashort echo time and spatial-temporal constrained reconstruction. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73:555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson KM, Fain SB, Schiebler ML, Nagle S. Optimized 3D ultrashort echo time pulmonary MRI. Magn Reson Med 2013; 70:1241–1250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chappell KE, Patel N, Gatehouse PD, Main J, Puri BK, Taylor‐Robinson SD, Bydder GM. Magnetic resonance imaging of the liver with ultrashort TE (UTE) pulse sequences. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2003; 18(6):709–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.CA Araujo E, Azzabou N, Vignaud A, Guillot G, Carlier PG. Quantitative ultrashort TE imaging of the short-T2 components in skeletal muscle using an extended echo-subtraction method. Magn Reson Med 2017; 78:997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Jong S, Zwanenburg JJ, Visser F, van der Nagel R, van Rijen HV, Vos MA, de Bakker JM, Luijten PR. Direct detection of myocardial fibrosis by MRI. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2011; 51:974–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du J, Ma G, Li S, Carl M, Szeverenyi NM, VandenBerg S, Corey-Bloom J, Bydder GM. Ultrashort echo time (UTE) magnetic resonance imaging of the short T2 components in white matter of the brain using a clinical 3T scanner. Neuroimage 2014; 87:32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boucneau T, Cao P, Tang S, Han M, Xu D, Henry RG, Larson PE. In vivo characterization of brain ultrashort-T2 components. Magn Reson Med 2018; 80:726–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernando D, Kramer JH, Reeder SB. Multipeak fat-corrected complex R2* relaxometry: Theory, optimization, and clinical validation. Magn Reson Med 2013; 70:1319–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hernando D, Hines CD, Yu H, Reeder SB. Addressing phase errors in fat-water imaging using a mixed magnitude/complex fitting method. Magn Reson Med 2012; 67:638–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh DO, Gmitro AF, Marcellin MW. Adaptive reconstruction of phased array MR imagery. Magn Reson Med 2000;43(5):682–690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hamilton G, Middleton MS, Hooker JC, Haufe WM, Forbang NI, Allison MA, Loomba R, Sirlin CB. In vivo breath-hold 1H MRS simultaneous estimation of liver proton density fat fraction, and T1 and T2 of water and fat, with a multi-TR, multi-TE sequence. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016; 42(6):1538–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pineda AR, Reeder SB, Wen Z, Pelc NJ. Cramér-Rao bounds for three-point decomposition of water and fat. Magn Reson Med 2005; 54:625–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamilton G, Yokoo T, Bydder M, Cruite I, Schroeder ME, Sirlin CB, Middleton MS. In vivo characterization of the liver fat 1H MR spectrum. NMR Biomed 2011; 24:784–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rojkind M, Giambrone M, Biempica L. Collagen types in normal and cirrhotic liver. Gastroenterology. 1979; 76(4):710–719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hernando D, Kramer JH, Reeder SB. Multipeak fat‐corrected complex R2* relaxometry: theory, optimization, and clinical validation. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(5):1319–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wood JC, Zhang P, Rienhoff H, Abi-Saab W, Neufeld E. R2 and R2* are equally effective in evaluating chronic response to iron chelation. Am J Hematol 2014;89:505–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doyle EK, Toy K, Valdez B, Chia JM, Coates T, Wood JC. Ultra‐short echo time images quantify high liver iron. Magn Reson Med 2018;79(3):1579–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krafft AJ, Loeffler RB, Song R, Tipirneni‐Sajja A, McCarville MB, Robson MD, Hankins JS, Hillenbrand CM. Quantitative ultrashort echo time imaging for assessment of massive iron overload at 1.5 and 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med 2017;78(5):1839–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson EM, Pauly KB, Pauly JM. In: Proceedings of the 25rd Annual Meeting of the ISMRM, Honolulu, USA: 2017:774 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.