Abstract

Crustose coralline algae (CCA) are calcifying red macroalgae that reef build in their own right and perform essential ecosystem functions on coral reefs worldwide. Despite their importance, limited genetic information exists for this algal group. De novo transcriptomes were compiled for four species of common tropical CCA using RNA-seq. Sequencing generated between 66 and 87 million raw reads. Transcriptomes were assembled, redundant contigs removed, and remaining contigs were annotated using Trinotate. Protein orthology analysis was conducted between CCA species and two noncalcifying red algae species from NCBI that have published genomes and transcriptomes, and 978 orthologous protein groups were found to be uniquely shared amongst CCA. Functional enrichment analysis of these ‘CCA-specific’ proteins showed a higher than expected number of sequences from categories relating to regulation of biological and cellular processes, such as actin related proteins, heat shock proteins, and adhesion proteins. Some proteins found within these enriched categories, i.e. actin and GH18, have been implicated in calcification in other taxa, and are thus candidates for involvement in CCA calcification. This study provides the first comprehensive investigation of gene content in these species, offering insights not only into the evolution of coralline algae but also of the Rhodophyta more broadly.

Subject terms: Transcriptomics, Ecology

Introduction

Crustose coralline algae (CCA) are calcifying red algae that form crusts on marine substrates worldwide, from polar regions to the tropics, and from intertidal zones to deep below the photic zone1,2. CCA are particularly abundant in tropical reefs, occupying much of the hard substrates within coral reef ecosystems3. Tropical CCA are key players in contributing to the global carbon cycle4 and provide various ecosystem functions, such as contributing to the structural complexity of coral reefs by building and cementing the carbonate framework5, and inducing the metamorphosis and settlement of coral larvae6,7 and other economically and ecologically important invertebrates8. Furthermore, CCA assist coral reefs to withstand and recover from disturbances9, and can therefore mitigate some of the negative impacts from the loss of reef structural complexity brought on by anthropogenic and naturogenic disruptions.

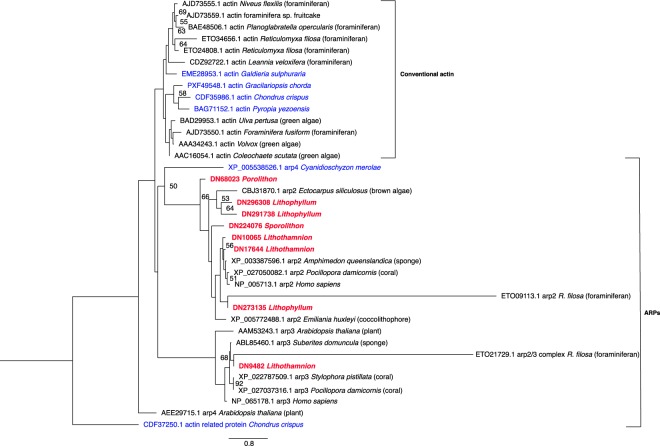

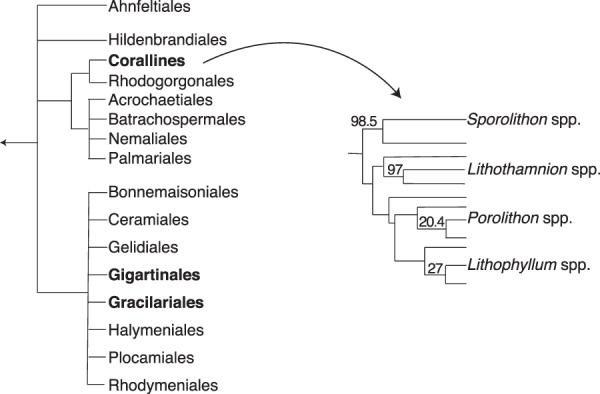

Coralline algae evolved from a red algal ancestor in the Early Cretaceous and began to diversify during the Early Miocene10 (Fig. 1). Coralline algae are unique amongst other red algae species due to the type of calcium carbonate used in this group11, and their ability to calcify within cell walls12. Coralline algae produce high magnesium calcite crystals generally oriented radially perpendicular to the cell wall as well as crystals oriented parallel to the wall in the interfilament region12,13, and their calcification process is considered to be an “organic matrix-mediated process12”. In contrast, the calcification process of other calcifying algae species, such as Halimeda spp., is considered to be “biologically induced”, occurring primarily outside the cell12. Calcification in coralline algae can be considered, to some extent, to be cellularly regulated, and is somewhat similar to the calcification process of coccolithophores which is thought to be an extreme example of “organic matrix-mediated” calcification or “biologically controlled” calcification12,14. Studies have also found the calcification process in coralline algae and coccolithophores to be linked to unusual polysaccharides15. The production and maintenance of these calcified skeletons is what allows CCA to play such a crucial role across tropical coral reefs and sets them apart from other calcifying algal species16. Coralline algae have been found to also upregulate the pH of their calcifying fluid/medium during calcification17. Due to the uniqueness of calcification in coralline algae, and their importance in general, there is a need for molecular mechanistic studies on coralline algae4. The use of molecular studies could lead to an understanding of the independent evolution of calcification in coralline algae, as well as an understanding of how these calcified organisms persisted and diversified during times of previously high pCO2 and temperature18.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree for the phylum Rhodophyta. Inset depicts the relationship of CCA species from different orders within the Corallines group. Phylogenetic tree for Rhodophyta based on Freshwater et al.79, Pueschel 199480, Ragan et al.81, Saunders and Bailey 199782. Tree for CCA is adapted from Aguirre et al.10 & Rösler et al.21. Node labels on inset tree of CCA species depict evolutionary time in millions of years.

An appreciation of the importance of CCA and the services they provide, and their sensitivity to climate change impacts, has led to a number of studies into their biology19, calcification17,20, phylogeny18,21, and physiology22,23. However limited molecular information (genomes, transcriptomes, gene expression profiles, or proteomes) exists for these species. This knowledge gap greatly limits our ability to fully understand whole organism function and the responses of this group of red algae to pressing environmental issues, such as changes in their environment brought on by human-induced change (e.g. ocean acidification and warming or declining water quality). The sequencing of genomes and/or transcriptomes provides essential information for the elucidation of the mechanisms that underpin physiological and biological traits and responses. Although sequencing has become more readily accessible24,25, genomes and annotated transcriptomes for many environmentally and economically important species are unavailable. ‘Omics’ studies are lacking in algae in general26, with minimal genomic information available in algae when compared to land plants27 or other phyla. Only 51 whole genomes are available for green algae, 3 for brown algae, and 9 for red algae, compared to the 672 for chordates, the 400 for arthropods, and the 345 for vascular plants (Table 1). A similar trend is seen for transcriptomes (Table 1). For coralline algae no complete genomes or transcriptomes have been published, however, mitochondrial28–30 and plastid genomes31 have been sequenced for some species. Therefore, there is a major knowledge gap in our understanding of the molecular landscape of coralline algae.

Table 1.

Number of published whole genomes and assembled transcriptomes for different taxa.

| Whole Genomes | Assembled Transcriptomes | |

|---|---|---|

| Chordates | 672 | 642 |

| Arthropods | 400 | 1442 |

| Vascular plants | 345 | 877 |

| Green Algae | 51 | 20 |

| Brown Algae | 3 | 42 |

| Red Algae | 9 | 36 |

| Coralline Algae | 0 | 0 |

Data taken from NCBI, as of February 2019. Transcriptome data taken from NCBI’s Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly Sequence Database and is most likely an overestimate as duplication of species is not taken into account.

In the present study, we generated transcriptomes for four species of tropical CCA: Porolithon cf. onkodes, Sporolithon cf. durum, Lithothamnion cf. proliferum, and Lithophyllum cf. insipidum, hereinafter referred to as Porolithon, Sporolithon, Lithothamnion, and Lithophyllum, respectively. These species were collected in the Great Barrier Reef, Australia, and were selected because they are common and abundant in tropical reefs and belong to different evolutionary lineages in the coralline algae (sensu lato). To ensure inclusion of stress-response genes within our transcriptomes we included samples taken after exposing the CCA to combined and independent increased temperature and decreased pH treatments. Orthology inferences were conducted to identify putative orthologous genes between these CCA species and other red algae for which genomic or transcriptomic data was available. A number of orthogroups appear unique to CCA, and inference of the likely functions of these genes provides insight into the evolution of these important reef-builders. This study provides a valuable framework for understanding the molecular biology of CCA and insight into genes potentially involved in important processes in CCA, such as calcification. Additionally, we hope this study will facilitate future research into the molecular responses and vulnerability of CCA to future environmental change.

Results and Discussion

De novo transcriptome assembly

The current study presents novel transcriptome assemblies for four species of crustose coralline algae (CCA): Sporolithon, Lithothamnion, Porolithon, and Lithophyllum. RNA-seq libraries for each species were generated from pooled RNA extracted from one individual reproductive adult from each of the different treatment conditions (n = 6) (refer to Methods & Supplementary Methods 1). Sequencing of these libraries produced between 66–87 million paired-end reads per species (n = 4). Variability was found across species when comparing assembly statistics (Table 2). Lithothamnion contained the fewest raw reads, which equated into the fewest assembled transcripts. Lithophyllum had a similar number of raw reads to Lithothamnion but had significantly more assembled transcripts. Sporolithon and Porolithon were most similar in their number of raw reads and assembled transcripts in comparison to the other two species. Clustering of redundant transcripts using CD-Hit reduced contig numbers by 16–27% (Table 2). Mean contig length was not significantly different between species, but was variable, ranging from 498–694 base pairs (bp), and N50 values ranged between 602–1147 bp (Table 2). These assembly statistics are comparable to those of transcriptomes from other red algal species such as Pyropia seriata32, Porphyra umbilicalis33, and Porphyra purpurea33, except the assembly of Lithophyllum which had a much lower N50 value indicating a more fragmented assembly. Read representation within each assembly, assessed by mapping raw reads for each species against their respective de novo transcriptomes (RMBT%), was high (94% or above). Variability in number of assembled transcripts and their resulting summary statistics may be due to collection of individual crusts at different reproductive stages for each species. Lithophyllum is reproductive year-round, and the samples taken likely possessed numerous gametangial and/or tetrasporangial conceptacles. Sporolithon and Porolithon were just coming into their reproductive time of year and likely had fewer reproductive structures, whereas Lithothamnion probably had the fewest number of reproductive structures as it has been found to be primarily reproductive in summer months (pers. obs.).

Table 2.

Summary statistics for Sporolithon, Porolithon, Lithothamnion, and Lithophyllum de novo transcriptome assemblies.

| Sporolithon | Porolithon | Lithothamnion | Lithophyllum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw reads | 81,176,680 | 87,281,439 | 66,119,011 | 64,651,990 |

| Contigs, with Jaccard Clip | 231,324 | 163,784 | 54,557 | 306,668 |

| Contigs after CDHIT clustering | 185,481 | 118,126 | 45,633 | 233,751 |

| Mean length (bp) | 589.1 | 584.72 | 693.59 | 498 |

| N50 (bp) | 862 | 788 | 1,147 | 602 |

| RMBT% | 95.22% | 97.25% | 98.68% | 94.07% |

| GC% | 42.42% | 44.53% | 49.02% | 46.92% |

N50 statistic denotes the length of contigs which cover 50% of the transcriptome. RMBT% is the percentage of reads that mapped back to the transcriptome. GC% represents the percentage or content of guanine-cytosine within the transcriptome.

Quality assessment of transcriptomes

The quality of each transcriptome was assessed using the Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Ortholog (BUSCO) assessment tool34. CCA de novo transcriptomes were compared against whole genome protein data from the noncalcified red algal species, Chondrus crispus and Gracilariopsis chorda, from the orders Gigartinales and Gracilariales, respectively (Fig. 1). BUSCO analysis of the four CCA transcriptomes showed that, out of the 303 near-universal single-copy eukaryote orthologs, between 87% and 93% complete sequences and 4% to 7% fragmented or partial sequences were detected (Table 3). Additionally, only between 3% and 7% of near-universal genes were classified as missing in the CCA transcriptomes, indicating high quality and good coverage. BUSCO analysis run on the reference genome proteins of the two noncalcifying red algae species returned similar measures of completeness, however, as expected for a curated genomic dataset, had a higher percentage of complete single-copy orthologs (73.90% to 88.80%), and a lower percent of duplication (2.60% to 3%). A higher percentage of missing BUSCOs was found in C. crispus (15.60%) when compared to the four CCA species, whereas, G. chorda had a similar percentage missing as Lithophyllum (Table 3). Three BUSCOs, EOG09370A22 (encoding a glycosyl transferase), EOG09370KWF (encoding a Per1-like gene), and EOG09370VTP (encoding a GPI mannosyltransferase) were found to be missing across all red algal species compared here, including the four CCA species. The absence of these genes from the transcriptomes of the 4 CCA species and the genomes of the 2 noncalcified red algal species may indicate that these genes were lost in the evolution of Rhodophyta. Additionally, there was one BUSCO, EOG09370JW6, missing across all CCA species, but present in the other noncalcifying red algae species. This gene, encoding for an elongator complex protein 4 (ELP4), is highly conserved in eukaryotes. It is part of a multi-subunit complex that interacts with elongating RNA polymerase II and is believed to facilitate transcription35, additionally, ELP4 plays a role in transfer RNA (tRNA) modification36. The elongator complex has also been tied to development and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses in plants35. In another study examining the elongator function in Arabidopsis thaliana, it was suggested that the elongator complex could influence mechanisms that produce carbon assimilates and the importation of sucrose37. The absence of the gene in all CCA transcriptomes generated here may indicate that it has been lost from the Corallines lineage entirely. Although many physiological states were sampled when collecting data for CCA it is possible that some genes may be missing from these assembled transcriptomes. Determination of the complete gene complement of these species, and confirmation of proposed gene losses, will require whole genome sequencing approaches.

Table 3.

BUSCO results from the de novo transcriptomes of four species of CCA compared to the whole genome data of two species of noncalcifying red algal species, C. crispus and G. chorda.

| BUSCO statistic | Coralline | Non-coralline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sporolithon | Porolithon | Lithothamnion | Lithophyllum | C. crispus | G. chorda | |

| Complete BUSCOs | 278 (92%) | 265 (88%) | 264 (87%) | 281 (93%) | 234 (77%) | 278 (91 %) |

| Complete - single-copy BUSCOs | 99 (33%) | 185 (61%) | 222 (73%) | 110 (36%) | 226 (75%) | 269 (88%) |

| Complete - duplicated BUSCOs | 179 (59%) | 80 (26%) | 42 (14%) | 171 (56%) | 8 (3%) | 9 (3%) |

| Fragmented BUSCOs | 15 (5%) | 17 (6%) | 22 (7%) | 11 (4%) | 25 (8%) | 10 (3%) |

| Missing BUSCOs | 10 (3%) | 21 (7%) | 17 (6%) | 11 (4%) | 44 (15%) | 15 (4%) |

Orthofinder analysis

Orthofinder was used to perform protein orthology analysis across red algae species using predicted proteins from the CCA transcriptomes generated here as well as those from the publicly available genomes of C. crispus and G. chorda. Given the high number of duplicated transcripts identified within transcriptomes via the BUSCO analysis, identification of orthologous sequences was conducted using translations of the single longest isoform of each Trinity gene from respective CCA transcriptomes. This resulted in a dataset that was less redundant, but also less complete (5% to 11% missing BUSCOs from this dataset compared with 3% to 7% previously).

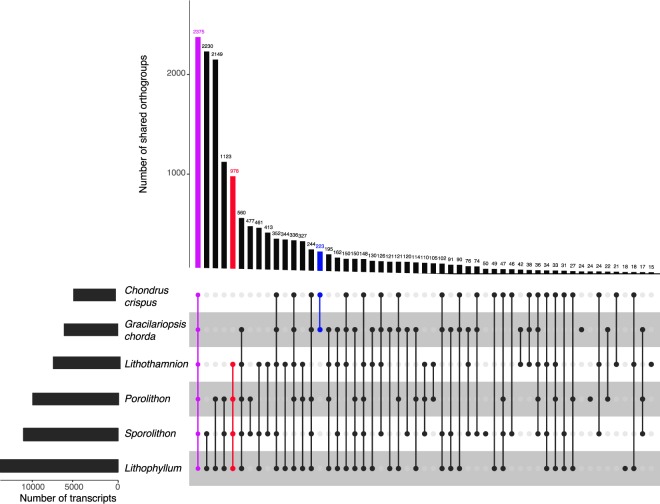

2,375 orthogroups (genes derived from a common ancestral gene) were shared across all red algal species examined in this study (Fig. 2). 978 orthogroups were found to be CCA-specific, whereas only 223 were found to be shared between the other red algal species, C. crispus and G. chorda, to the exclusion of CCA. The low number of unique orthogroups found between these two species of fleshy macroalgae may relate to their phylogenetic relationship (these two species are from different, distantly related orders, whereas the CCA species are from closely related orders), or may reflect the use of protein sequences derived from transcriptomes vs proteins predicted from whole genome data. Lithophyllum had the most orthogroups in common with other species of CCA, this is probably due to the larger number of transcripts in the Lithophyllum dataset, whereas Lithothamnion had the fewest transcripts and therefore had fewer orthogroups common with the other species (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Plot visualising shared and unique orthologous protein groups across four species of crustose coralline algae, Lithophyllum, Sporolithon, Porolithon, and Lithothamnion, and two species of noncalcified red algae, G. chorda and C. crispus. Plot at the top shows the number of orthogroups found in the species indicated in the schematic below. Shared orthogroups across all red algae species are highlighted in purple, across only CCA species in red, and across only the noncalcifying red algal species in blue. Orthologous proteins were identified with Orthofinder and plotted using the R package, UpsetR75. Any relationships with <15 orthogroups were omitted.

Enrichment analysis

Enriched CCA-specific genes

The genes found within the CCA-specific orthogroups are likely novel to the CCA lineage or represent expansions and diversification of ancestral algal gene families, and potentially reflect unique aspects of CCA biology with respect to noncalcified red algae. To evaluate these further an analysis was conducted to detect enrichment of putative functional categories within these CCA-specific orthogroups. Gene Ontology (GO) category enrichment was assessed against the whole transcriptome annotation, obtained from Trinotate v 3.1.138. Overrepresentation of ‘biological process’ GO categories within the CCA-specific orthogroups was assessed via the Cytoscape39 plugin BiNGO40 using the complete transcriptome annotation for each CCA species as reference. Orthogroups that were found to be significantly (p < 0.01) overrepresented were further examined by extracting sequences from these families and submitting them to BLASTP (NCBI), using an e-value cutoff of 1e−3, to identify conserved domains and to indicate possible protein function (hypothesised via homology). GO categories such as the ‘regulation of transport’, ‘adhesion’, ‘supramolecular fibre organisation’, ‘regulation of actin cytoskeleton organisation’, and ‘regulation of cellular component organisation’ were found to be enriched in CCA-specific orthogroups (Table 4). A number of these categories were related (e.g., several involve actin) and are the result of enriched genes having multiple functional annotations. Only genes that had significant BLAST hits to other proteins were investigated further, as many of the genes within these categories appeared to be unique to CCA. It is notable that no categories related to biomineralisation or calcification were found to be enriched; this may reflect a different mode of biomineralisation of CCA to that of other, better studied organisms (e.g., polysaccharide mediated mineralisation as opposed to the protein-based matrix mediated mineralisation of vertebrates, molluscs and echinoderms). Although many of the genes that fell within these functionally enriched categories produced no significant hits in BLAST searches against NCBI’s nr database (and likely represent CCA-specific genes, or, possibly, contamination), a number appear to be members of larger gene families. Phylogenetic analysis was performed on these genes to provide further insight into their evolution and potential function.

Table 4.

GO categories enriched across all CCA-specific orthogroups. Values represent adjusted p value (<0.01).

| GO Term | Category Description | Sporolithon | Porolithon | Lithothamnion | Lithophyllum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GO:0032271 | Regulation of protein polymerisation | 2.08E-04 | 1.16E-04 | 5.07E-07 | 1.59E-04 |

| GO:0030833 | Regulation of actin filament polymerisation | 1.13E-03 | 7.65E-03 | 6.85E-07 | 1.06E-04 |

| GO:0030036 | Actin cytoskeleton organisation | 4.76E-04 | 1.33E-06 | 1.42E-06 | 7.13E-06 |

| GO:0097435 | Supramolecular fibre organisation | 4.76E-04 | 1.14E-04 | 1.66E-06 | 8.87E-06 |

| GO:0032956 | Regulation of actin cytoskeleton organisation | 6.05E-03 | 1.33E-06 | 1.06E-04 | 1.92E-04 |

| GO:0043254 | Regulation of protein complex assembly | 4.45E-03 | 1.04E-04 | 3.29E-06 | 9.11E-03 |

| GO:0051493 | Regulation of cytoskeleton organisation | 4.76E-04 | 2.71E-05 | 6.82E-06 | 3.39E-04 |

| GO:0051128 | Regulation of cellular component organisation | 9.94E-05 | 2.96E-04 | 6.82E-06 | 3.25E-03 |

| GO:0007010 | Cytoskeleton organisation | 1.52E-04 | 1.70E-14 | 9.90E-06 | 6.59E-24 |

| GO:0051049 | Regulation of transport | 2.08E-04 | 2.37E-03 | 5.18E-06 | 2.18E-09 |

| GO:0007155 | Adhesion | 9.09E-03 | 1.11E-05 | 2.94E-05 | 1.51E-15 |

| GO:0030029 | Actin filament-based process | 1.13E-03 | 1.81E-04 | 1.99E-06 | 1.02E-05 |

‘Regulation of transport’ related genes

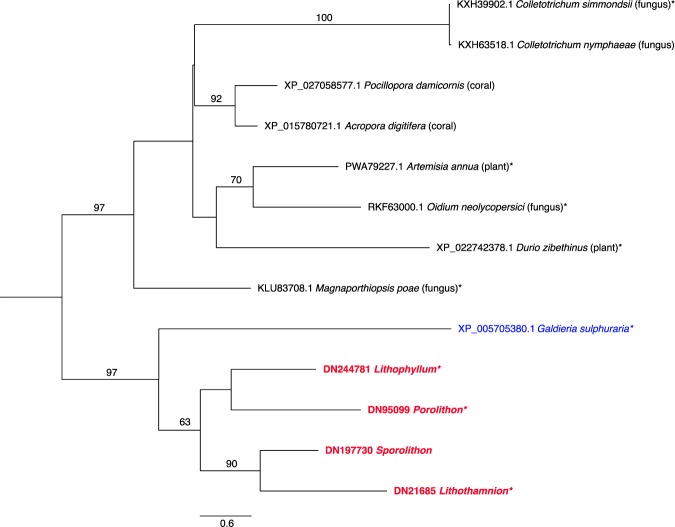

There were multiple orthogroups within the ‘regulation of transport’ category that were found to be overrepresented across the coralline species. One of these orthogroups contained sequences that contained a zinc finger domain, a domain previously undescribed in corallines. Zinc finger-like proteins have been found in other red algae species, such as the extremophilic unicellular species Galdieria sulphuraria (BioProject: PRJNA13023)41, Cyanidioschyzon merolae (BioProject: PRJNA28057)42, and C. crispus43. A phylogenetic tree was constructed for zinc finger type proteins, revealing that the CCA protein is most similar to a CCHC-type zinc finger domain protein found in G. sulphuraria and that proteins of this type are likely ancestral for red algae, but may have been lost in a number of lineages such as C. crispus and G. chorda (Fig. 3). Zinc-finger domains bind DNA, RNA, protein and/or lipid substrates, with the CCHC-type primarily acting in RNA or single-stranded DNA binding44. Three of the four CCA zinc-finger proteins possessed a CCHC zinc finger domain, indicating that these proteins may bind to RNA or single-stranded DNA substrates in Porolithon, Lithothamnion, and Lithophyllum. The zinc finger domain of the Sporolithon sequence, however, appears to have diverged from a typical CCHC, indicating a different function of this protein in Sporolithon. CCHC domain-containing zinc fingers do not form a monophyletic clade in the tree, indicating that this domain (and presumably its binding capability) can be readily lost (or gained) (Fig. 3).

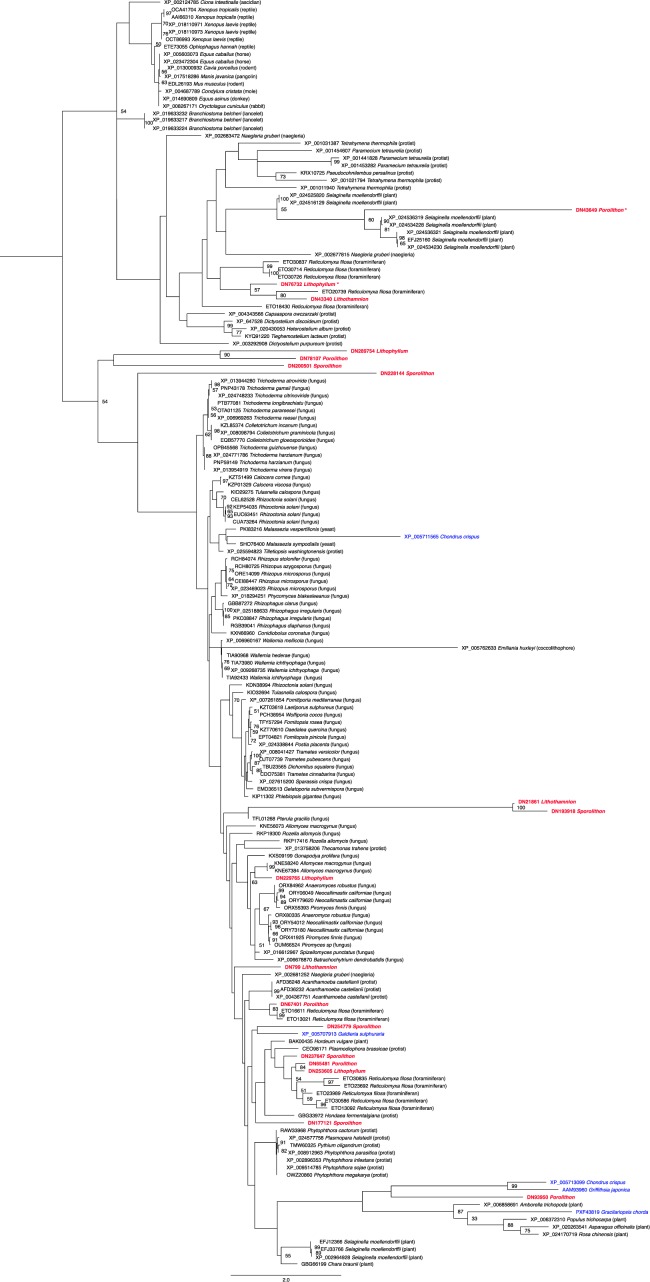

Figure 3.

Best scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of zinc finger domain sequences. Midpoint rooted tree, with bootstrap values <50 removed. Scale bar indicates the branch length for 0.6 amino acid (aa) substitutions. *Denotes full sequences that contain the CCHC-type zinc-finger like conserved domain. CCA names are shown in bolded red and other noncalcifying red algae species are in blue.

Another orthogroup relating to the regulation of transport was found to be overrepresented in CCA when compared to the other two noncalcified species. These genes were primarily from the protein kinase family, specifically, the family of protein kinases that phosphorylate serine/threonine, however, two incomplete sequences possessed conserved unconventional myosin tail domains (marked with * in Fig. 4) but still returned top hits with protein kinase sequences from BLASTP analysis. These sequences were further investigated using the Pfam database45, and it was found that there are other proteins that have this domain that are not myosins and that possess the domain arrangement of unconventional myosin tails and protein kinases, specifically serine/threonine protein kinases (STKs). Therefore, it is likely that if these two sequences were full, they would have the conserved STK domain. This gene family appears to have undergone expansions in the CCA lineage, with between 3–6 genes present in each species (Fig. 4). The phylogenetic tree displays the relationship of CCA STKs to those of other eukaryotic species, including algae, plants, and protists. The length of the branches for some of the CCA sequences suggests that these genes are evolving rapidly in CCA, and may also explain why the CCA sequences do not always clade together or with other red algae species. However, support values within this tree are generally low, making reconstruction of evolutionary history difficult. CCA STK-related genes maintained the conserved domains (200–450) that are characteristic of STKs46. STKs in plants are described to act as a “central processor unit”, accepting information from receptors that sense environmental conditions and other external factors, and then act to convert those signals into appropriate responses or outputs, such as changes in metabolism, cell growth and division, and gene expression47. The number of genes within the STK family could suggest an important role for phosphorylating serine/threonine or phosphoserine/threonine signalling in CCA. An analogous situation occurs in the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, where the high number (28) of putative tyrosine kinases relates to the importance of phosphotyrosine signalling in this taxon48. STKs have only been described in two other multicellular red algal species, with G. chorda only having one protein identified as an STK. However, the widespread red algal species C. crispus has a large number of possible STKs in its genome, suggesting this protein family could be important for species that live in variable environments, allowing them to have a more advanced system in responding and reacting to external factors and environmental conditions.

Figure 4.

Best scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of serine/threonine protein kinase-like sequences. Midpoint rooted tree, with bootstrap values <50 removed. Scale bar indicates the branch length for 2.0 aa substitutions. CCA names are shown in bolded red and other noncalcifying red algae species are in blue. Incomplete sequences that were found within the enriched category but did not have serine/threonine protein kinase-like conserved regions are marked with a*.

Six genes across the four species were found to form a supported clade exhibiting similarity to glycosyl hydrolase family 18-like (GH18) proteins (Fig. 5). The GH18 gene family is previously undescribed in corallines and is generally undescribed in red algae species, although similar proteins from other red algal species contain GH18 conserved regions (PXF42839.1 G. chorda, CDF36488.1 C. crispus). In initial phylogenetic analyses the CCA sequences formed a well-supported clade that was not sister to other red algal GH18 proteins (data not shown). Although these noncalcifying red algae (fleshy, temperate species) are phylogenetically and physiologically distant from the CCA investigated here, meaning that, due to functional divergence, their sequences may not always form monophyletic clades, noncalcifying red algal GH18 sequences were used as queries in BLAST searches against the transcriptomes of the four species of CCA to determine if additional GH18 sequences were present. Two additional GH18 sequences were identified from Sporolithon with e-values of 0.0 and were added to the analysis (denoted with •, Fig. 5). These two sequences grouped with the other red algal sequences with high support, whereas the six CCA GH18 sequences identified in the enrichment analysis formed a separate clade. It therefore appears that GH18 sequences have duplicated within the CCA lineage, with the duplicates perhaps evolving different functions. Proteins within the GH18 family have been proposed to play a role in polysaccharide processing49 and can be active chitinases50. Chitin has been described among the polysaccharides of a coralline alga species, Clathromorphum compactum, which is an arctic and subarctic species51. These chitin containing polysaccharides might be important molecules in the calcification process of this species, with the chitin providing additional strength and protection to the calcified skeleton of C. compactum, therefore making it more resilient to the negative effects of ocean acidification, or the decrease in ocean pH51. GH18 proteins have also been linked to the biomineralization process in the pearl oyster, Pinctada fucata52, raising the possibility that enriched GH18 like proteins in CCA may similarly play a role in their biomineralization process. It is noteworthy that novel glycosyl hydrolases may be present in CCA whereas, from BUSCO results, highly conserved glycosyl transferases are missing across CCA and other red algal species compared here. This indicates that polysaccharide metabolism may be highly modified within the Rhodophyta.

Figure 5.

Best scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of GH18 like sequences. The clade containing homologous chitinase related proteins from the bacterium Serratia marcescens was used as the outgroup. Bootstrap values <50 removed. Scale bar indicates the branch length for 0.9 aa substitutions. CCA names are shown in bolded red and other noncalcifying red algae species are in blue. •Denotes additional CCA GH18 sequences that were not found within the ‘enriched’ category.

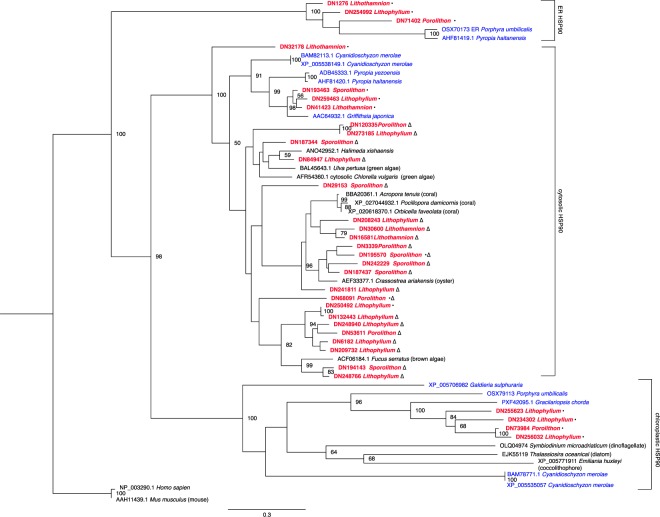

‘Supramolecular fibre organisation’ related genes

The category ‘supramolecular fibre organisation’ was found to be overrepresented in the CCA-specific orthogroups. When investigated further, sequences within this category were found to be actin-related proteins (ARPs) or heat shock proteins (HSPs). A tree was constructed with conventional actin genes (obtained from NCBI) and different families of ARPs from different species (Fig. 6), using ARP 1, 2, 3, and 4 sequences from the evolutionary analysis of the actin family in Goodson & Hawse, 200253. Albeit with low support, it was found that most ‘CCA-specific’ proteins from this family were most closely related to ARP2, however, one protein from Lithothamnion was placed within the ARP3 clade. ARPs are found in other red algae species; however, few ARP2 sequences have been found, and no ARP3. Conventional actin in Florideophyceae has been reported to have undergone a duplication event, which is possibly linked to the complexity of thallus organisation and modes of reproduction for this class of algae54. Corallines belong to the class Florideophyceae, however no conventional actins were found within their transcriptomes. It is possible that the duplication of ARPs within this lineage created functional redundancy, leading to the loss of conventional actins in CCA, alternatively, conventional actins may be present in CCA genomes but not expressed in the stages sampled here.

Figure 6.

Best scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of actin related protein sequences. Tree was rooted at actin related protein (ARP) from C. crispus (CDF37250.1). Bootstrap values < 50 removed. Scale bar indicates the branch length for 0.8 aa substitutions. Brackets group proteins that are conventional actin sequences or ARPs. CCA names are shown in bolded red and other noncalcifying red algae species are in blue.

Actins are known to play a role in biomineralisation in some unicellular calcifiers. For example, in the calcifying coccolithophore Coccolithus braarudii it was found that disruption of the actin network inhibits elements of secretion and biomineralization55. More recently, Tyszka, et al. (2019) found that F-actin (filamentous actin) is involved in the formation of the calcified chamber/shell of the foraminifera species Amphistegina lessonii, ultimately controlling mineralisation56. Therefore, it is possible that the expansion of ARP genes found in CCA is associated with the evolution of calcification in this lineage. CCA ARPs do not group with those of calcifying foraminifera in the phylogenetic tree, however given that CCA calcification evolved independently from that of coccolithophores and foraminiferans it is not expected that orthologous actin genes would necessarily be involved in the calcification process of these taxa.

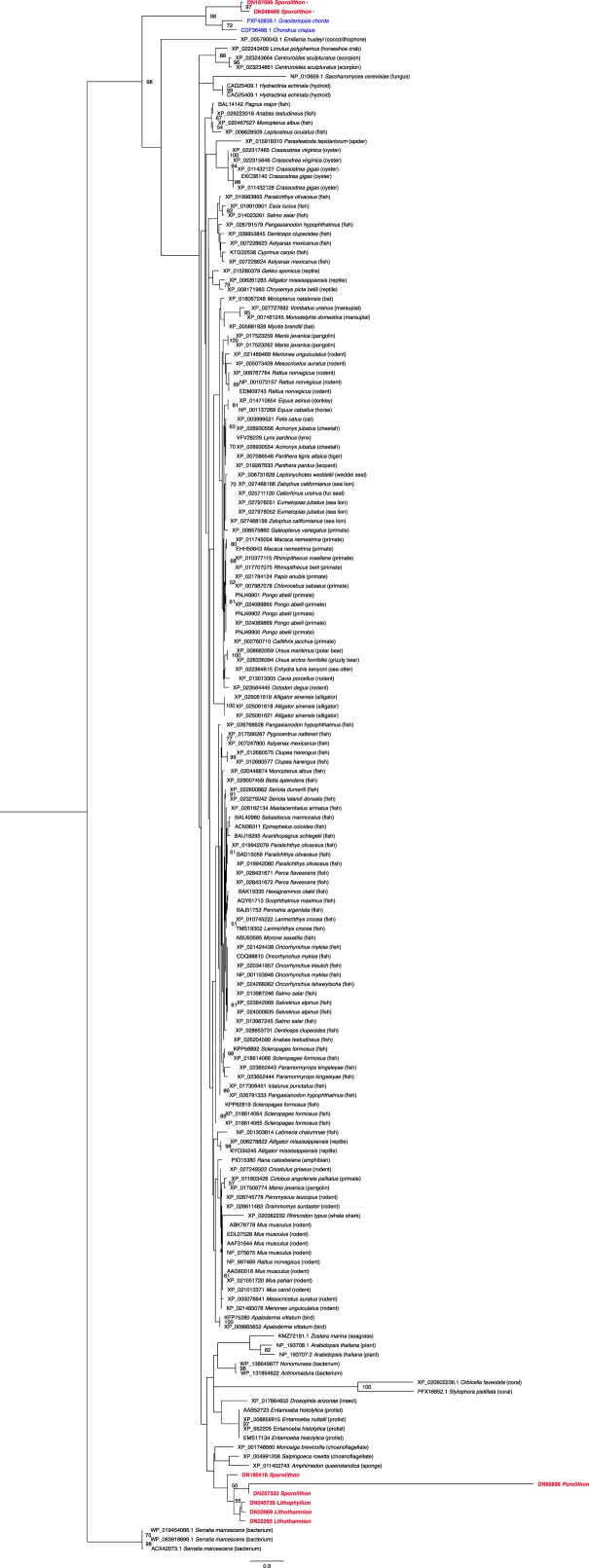

Heat shock protein 90 (HSP90) was also found within the overrepresented category ‘supramolecular fibre organisation’. Phylogenetic analysis reveals that the CCA HSP90 gene family appears to have undergone significant gene duplication events in comparison to other red algae (Fig. 7), and that some duplications likely occurred after the divergence of the four CCA lineages (for example, in Lithothamnion and Sporolithon, the two earliest-diverging coralline lineages investigated). HSP90 family members have gone through multiple duplication events throughout their evolution and subsequent losses, and can be found throughout different components of a cell57. In initial phylogenetic analyses all CCA HSP90 sequences fell within a well-supported clade of cytosolic HSP90 sequences, whereas noncalcified red algae also possessed chloroplastic and endoplasmic reticulum HSP90 genes (data not shown). To determine whether additional HSP90 sequences were present in CCA transcriptomes, the chloroplast HSP90-5 sequence from G. chorda (PXF42095.1) was used as a query in a BLAST search against the transcriptomes from the four species of CCA. With an e-value cutoff of 1e−80, 3–12 additional HSP90 genes per CCA species were identified, including three from Lithophyllum and one from Porolithon that grouped with chloroplastic HSP90s, and two from Lithophyllum and one from Porolithon that grouped with endoplasmic reticulum HSP90s in the phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 7). Only 2 sequences were found both within the enriched category of ‘supramolecular fibre organisation’ sequences, and by protein BLAST on the CCA transcriptomes. Overall, there has been extensive duplication of cytosolic HSP90 genes in the CCA species investigated here, most of which likely occurred prior to the diversification of these lineages. These duplications could be linked to the evolutionary history of these algae, having persisted during times of previous elevated temperature21. It is also possible that some of the duplications, particularly more recent ones, could be associated with adaptation to particular habitat types (i.e. reef flats or intertidal zones).

Figure 7.

Best scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of heat shock protein 90 sequences. Clade containing Mus musculus and Homo sapiens endoplasmic reticulum (ER) HSP90 was used as the outgroup. Bootstrap values <50 removed. Scale bar indicates the branch length for 0.3 aa substitutions. CCA names are shown in bolded red and other noncalcifying red algae species are in blue. •Denotes HSP90 genes found in CCA that were highly similar to G. chorda (PXF42095) chloroplastic HSP90 sequence from BLASTP transcriptome analysis. ∆denotes HSP90 sequences that were within the enriched category of ‘supramolecular fibre organisation’. •∆Denotes sequences that were returned from both analyses.

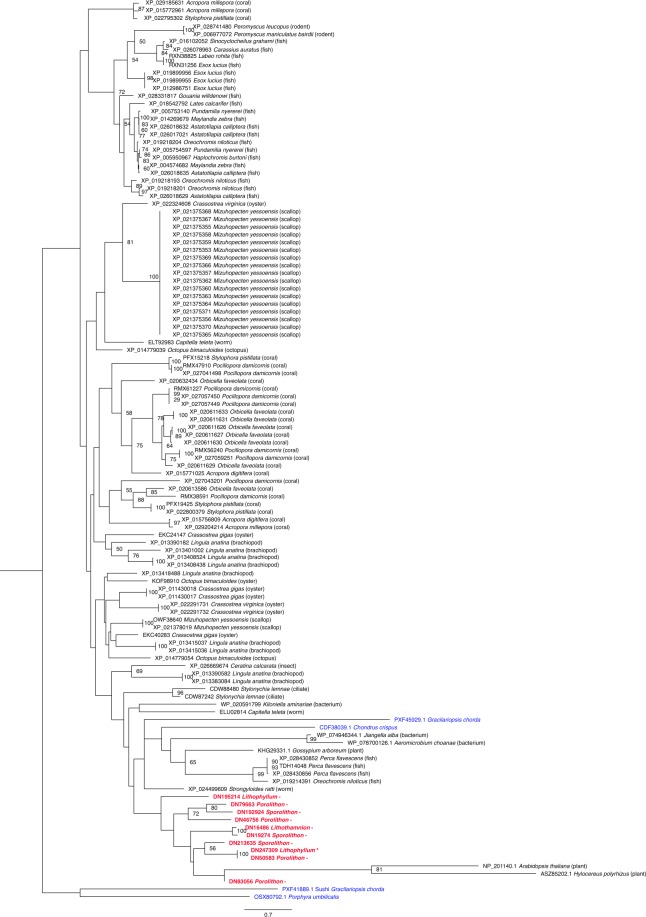

‘Adhesion’ related genes

The ‘adhesion’ GO term was enriched across CCA-specific orthogroups, potentially relating to their habit as encrusting organisms where cell-cell adhesion and extracellular matrix are essential for maintenance of the structural and functional integrity of the crust. The majority of the proteins within this category returned only hypothetical protein matches or no matches within the Pfam45 database, indicating these genes are likely to be unique to CCA. However, across the CCA species, 10 genes contained conserved regions similar to von Willebrand factor type A (VWA) domains found in other eukaryotes (Fig. 8). Intracellular VWA domain proteins common to all eukaryotes are involved in fundamental cellular functions (e.g. transcription ribosomal transport, DNA repair, and protein degradation)58. VWA domain proteins in plants and fungi are intracellular, whereas an expansion event in other eukaryotes resulted in large numbers of extracellular VWA domain proteins58. The functions of these extracellular VWA domain proteins include cell adhesion and protein-protein interactions, however in molluscs extracellular VWA proteins have been implicated in the formation of calcium carbonate shells52,59. VWA domain proteins from CCA appear to form their own, well supported clade away from other intracellular sequences used in this tree (Fig. 8). Most CCA sequences were found to be partial or incomplete, however, one CCA sequence was found to be full-length and is predicted to be secreted, through signal peptide analysis (denoted with * in Fig. 8). Although the majority of CCA sequences were found to be incomplete, the sequences grouped together with the predicted extracellular CCA sequence, therefore it is likely that these enriched sequences are all extracellular (Fig. 8). Therefore, it is possible, that extracellular VWA domain proteins in CCA may have evolved independently in corallines and play a similar role to that of extracellular VWA proteins in other marine calcifiers.

Figure 8.

Best scoring maximum likelihood phylogenetic analysis of von Willebrand A domain sequences. The clade containing the sushi domain sequence of G. chorda was used as the outgroup. Bootstrap values <50 removed. Scale bar indicates the branch length for 0.7 aa substitutions. *Denotes full protein sequences that are likely to be secreted, and therefore extracellular. —Denotes incomplete or partial sequences. All other sequences in the tree are predicted to be intracellular and/or not secreted. CCA names are shown in bolded red and other noncalcifying red algae species are in blue.

Conclusions

The ability for coralline algae to deposit high Mg calcite in their cell walls is unique within red algae, as are the intricate calcium carbonate skeletons that allow them to play crucial roles across tropical coral reefs worldwide. From the investigation into the transcriptomes generated in this study, we provide insight into what sets CCA apart from other red algal species, that is, the large number of genes relating to regulation of transport, supramolecular fibre organisation, adhesion, and potentially calcification (e.g. actin related genes and GH18). Our study also offers insights not only into the evolution of coralline algae but more broadly of the red algae (e.g. by confirming the loss of genes in the group). The role of CCA on tropical reefs is integral to reef survival, yet prior to this study, there was limited molecular information for corallines and no complete molecular information for any species of CCA. CCA may be crucial when it comes to the longevity of coral reefs in the face of future environmental change due to their ability to cement and support the carbonate framework of reefs, and for the settlement of important coral reef larvae. This study provides a foundation for future studies of gene expression and function in CCA.

Methods

Algae collection

Fragments of CCA ranging in size from 4 cm2 to 6 cm2 were collected from sites within the lagoon of Lizard Island (Great Barrier Reef, Australia) on SCUBA using a hammer and chisel. Care was taken when collecting to minimise any impact on the reef, and collection was spread out across reefs. Species from low light environments, Sporolithon cf. durum and Lithothamnion cf. proliferum, were collected at around 7 m depth from reefs between Bird Islet and Lizard Head. Porolithon cf. onkodes and Lithophyllum cf. insipidum were collected from the reef crest, >3 m depth, between South Island and Palfrey Island. A total of 18 individuals from each species were collected over three days, avoiding collection of highly visibly epiphytised fragments. All fragments were thoroughly cleaned, by using a scrubbing brush and razor underneath a microscope, of epiphytes directly after collection and twice more before sampling for molecular analysis.

To ensure the most comprehensive transcriptomes possible and the utility of this dataset for future investigation of CCA response to environmental change, samples were either taken directly after collection from the field, after maintenance for 2.5 weeks under altered pH and temperature conditions, or after maintenance for 3 weeks under common-garden conditions (see Supplementary Methods 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Treatments were conducted at Lizard Island Research Station (LIRS) on Lizard Island from September 2017 to October 2017. The experiment ran for 2.5 weeks, from September to October 2017. All four species of CCA were used within the treatments.

Molecular sampling

Prior to sampling, each fragment of algae was thoroughly rinsed with filtered seawater and blotted with a kimwipe to remove bacterial film60, and then scraped using new, sterile razors into a pre-labelled 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube containing 1 mL of RNAlater. Care was taken to only remove the top, pigmented, living layer of the CCA, avoiding epiphytes, endolithic algae (which do not penetrate the pigmented layer of the algae and rather sit within the unpigmented CaCO3 skeleton), and to eliminate cross contamination between species and treatments. Tubes containing CCA material in RNAlater were then kept at −20 °C at LIRS until being transported on ice to a −20 °C freezer at Griffith University where they were stored until further analysis. CCA host an array of epibionts, and although care was taken in sampling, it is possible that there was some residual contamination.

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted from CCA samples using a modified TRIzol® RNA extraction protocol from Invitrogen. CCA samples were removed from RNAlater and then homogenised in Trizol (1 mL) at room temperature for 6 mins at 30 Hz using a QIAgen TissueLyser. After the initial 3 mins of homogenisation, samples were removed, placed on ice for 5 mins, and then homogenised for the remaining 3 mins. Further processing followed the manufacturer’s protocol, using bromochloropropane for phase separation, and high-salt solution for precipitation. RNA pellets were resuspended in DNase/RNase-free distilled water (20 µl). Total RNA quantity was determined spectrophotometrically using Invitrogen Qubit® Broad Range RNA kit. RNA yield ranged from 5.36 ng RNA/µl to 800 ng RNA/µl. Presence of contaminating DNA was checked randomly in samples using an Invitrogen Qubit® DNA High Sensitivity kit and returned readings “too low for detection”.

Library construction and sequencing

RNA samples from all conditions (treatments, field, common garden) were pooled for each species (n = 4) prior to sequencing library construction. When pooling samples, similar quantities from each sample was added to the pool (i.e. samples that resulted in high yields were diluted down to match lower yielding samples). Total RNA quantity of pooled samples was checked using the Qubit® to ensure a value of at least 20 RNA/µl; final concentrations for Sporolithon, Porolithon, Lithothamnion, and Lithophyllum were 25.4 RNA/µl, 38.6 RNA/µl, 24.4 RNA/µl, and 35.6 RNA/µl, respectively. Quality of pooled RNA was tested using the 4200 TapeStation System. Once RNA was checked, pooled RNA samples (60 µl) were then precipitated and sent to Macrogen, Inc (Seoul, South Korea) for cDNA library preparation using a TruSeq Stranded mRNA LT Sample Prep Kit. The kit used to prepare libraries uses oligo-dT beads to capture RNA species containing polyadenylated tails, therefore minimal bacterial sequences should be present in the resulting transcriptomes. Individually barcoded libraries were sequenced using 100 bp paired-end reads on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 to generate between 87 M and 66 M raw reads per library, with GC content ranging from 45–48%.

Transcriptome assembly and optimisation

All bioinformatic analyses were performed on Griffith University’s High Performance Computer Cluster “Gowonda”. Quality control was performed on the raw sequence data using FastQC (v 0.11.3, Babraham Bioinformatics). Raw sequences were aligned to assembled transcripts using bowtie61 (v 2–2.0.2) and assembled with Trinity62 (v 2.4.0) using the default parameters and enabling trimmomatic63, to quality trim reads, jaccard clip (which is used for compact genomes), and without normalisation of the reads. To remove redundant transcripts, highly similar sequences were clustered using CD-Hit64 (v 4.6.6) using a nucleotide identity threshold of 0.95. To assess assembly completeness, BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs)34 (v 3.6.1) and the eukaryota_odb9 dataset were used to compare transcriptomes against highly conserved eukaryote orthologs selected from OrthoDB65 (v 9.1). Results from BUSCO were compared against whole genome data from the noncalcifying red algae Chondrus crispus (PRJNA193762)43 and Gracilariopsis chorda (PRJNA361418)66.

Annotation of the transcriptomes was conducted using Trinotate v 3.1.138, which performed sequence homology searching against the SwissProt database67 by BLAST68, Pfam database45 by hmmscan69, and association with Gene Ontology (GO) terms70.

Gene ontology and enrichment analysis

All four transcriptomes contained a large number of redundant transcripts. To reduce this, Transdecoder was first used to identify the single best copy of each transcript, as determined by Transdecoder (http://transdecoder.github.io) using the -single_best_orf command. The dataset containing the single best copy of each transcript was then further filtered to obtain the single longest isoform per Trinity gene. Orthofinder71 (v 2.2.3) was then used with this dataset to identify orthologous genes/proteins across CCA species and the whole genome protein data from two other noncalcifying red algae species C. crispus and G. chorda. Unique and shared orthogroups were identified using the micropan72 (v 1.2), dplyr73 (v 0.8.0.1), and tibble74 (v 2.1.1) packages within RStudio (v 1.1.456) and visualised using the R package UpSetR75.

Enrichment analysis of CCA-specific orthogroups identified from the orthology analysis was conducted using the Cytoscape39 (v 3.7.1) plugin BiNGO40. This was carried out using a hypergeometric statistical test on GO categories from ‘biological processes’, set with a p value of 0.01. The annotation files for each species of CCA were used, and only groups that were found to be enriched across all CCA species were investigated further.

Phylogenetic analysis

Proteins within enriched categories were analysed via BLASTP68 and homology searching within the HMM database69. For sequences returning eukaryotic BLAST hits with significant e-values (1e−3) on NCBI’s nonredundant database, once conserved protein regions and associated potential functions were identified, related genes from other species were downloaded from NCBI, focusing predominately on top BLAST hits and supplemented with other algal or plant groups. In some instances (phylogenetic analysis of GH18 and HSP90) sequences from other red algae that maintained similar conserved regions were blasted against the transcriptomes of the four species of CCA and sequences that had e-values close to 0.0 were also used in the phylogenetic trees. Sequences were aligned in AliView76 (v 1.23) and phylogenetic analysis was performed using RAxML77 (v 8.2.11) with automatic model selection and 100 nonparametric bootstrap replicates. Protein trees were visualised using FigTree78 (v 1.4.4).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Australian Research Council grant DP160103071 award to G.D.-P. The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Griffith University eResearch Services Team and the use of the High Performance Computing Cluster “Gowonda” to complete this research. We thank Dr. Alexandra Ordoñez-Alvarez and Dr. Luis Gómez-Lemos for their help with collections and fieldwork and the Lizard Island Research Station for hosting us during this experiment.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived of the study and wrote and reviewed the manuscript. T.M.P. performed and analysed experimental work. T.M.P. processed all samples, and T.M.P. and C.M. performed bioinformatic analyses.

Data Availability

Raw data has been deposited in NCBI under BioProject PRJNA518156. The Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly Fasta files have been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers GHIN00000000, GHIO00000000, GHIP00000000, and GHIV00000000 for Sporolithon cf. durum, Porolithon cf. onkodes, Lithothamnion cf. proliferum, and Lithophyllum cf. insipidum, respectively.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-48283-1.

References

- 1.Littler MM, Littler DS, Blair SM, Norris JN. Deepest known plant life discovered on an uncharted seamount. Science. 1985;227:57–59. doi: 10.1126/science.227.4682.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steneck RS. The ecology of coralline algal crusts convergent patterns and adaptative strategies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1986;17:273–303. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.17.110186.001421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dean AJ, Steneck RS, Tager D, Pandolfi JM. Distribution, abundance and diversity of crustose coralline algae on the Great Barrier Reef. Coral Reefs. 2015;34:581–594. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1263-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCoy SJ, Kamenos NA. Coralline algae (Rhodophyta) in a changing world: integrating ecological, physiological, and geochemical responses to global change. Journal of Phycology. 2015;51:6–24. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adey WH. Coral reefs: algal structured and mediated ecosystems in shallow, turbulent, alkaline waters. Journal of Phycology. 1998;34:393–406. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.1998.340393.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harrington L, Fabricius K, De’Ath G, Negri AJE. Recognition and selection of settlement substrata determine post‐settlement survival in corals. Ecology. 2004;85:3428–3437. doi: 10.1890/04-0298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ritson-Williams R, Arnold SN, Fogarty ND, Steneck RS, Vermeij MJA. New perspectives on ecological mechanisms affecting coral recruitment on reefs. Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences. 2009;38:437–457. doi: 10.5479/si.01960768.38.437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daume S, Brand-Gardner S, Woelkerling WJ. Settlement of abalone larvae (Haliotis laevigata Donovan) in response to non-geniculate coralline red algae (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 1999;234:125–143. doi: 10.1016/S0022-0981(98)00143-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doropoulos C, Ward S, Diaz-Pulido G, Hoegh-Guldberg O, Mumby PJ. Ocean acidification reduces coral recruitment by disrupting intimate larval-algal settlement interactions. Ecology Letters. 2012;15:338–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguirre J, Perfectti F, Braga JC. Integrating phylogeny, molecular clocks, and the fossil record in the evolution of coralline algae (Corallinales and Sporolithales, Rhodophyta) Paleobiology. 2010;36:519–533. doi: 10.1666/09041.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nash MC, et al. First discovery of dolomite and magnesite in living coralline algae and its geobiological implications. Biogeosciences. 2011;8:3331–3340. doi: 10.5194/bg-8-3331-2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borowitzka MA, Larkum AWD. Calcification in algae: mechanisms and the role of metabolism. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 1987;6:1–45. doi: 10.1080/07352688709382246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adey, W. H., Halfar, J. & Williams, B. The coralline genus Clathromorphum Foslie emend. Adey: biological, physiological, and ecological factors controlling carbonate production in an arctic-subarctic climate archive. Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences, 1–41, 10.5479/si.1943667X.40.1 (2013).

- 14.Brownlee, C. & Taylor, A. Calcification in coccolithophores: a cellular perspective in Coccolithophores (eds Thierstein, H. R. & Young, J. R.) 31–49 (Springer, 2004).

- 15.Bilan MI, Usov AI. Polysaccharides of calcareous algae and their effect on the calcification process. Russian Journal of Bioorganic Chemistry. 2001;27:2–16. doi: 10.1023/a:1009584516443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Littler MM, Littler DS. Models of tropical reef biogenesis: the contribution of algae. Progress in phycological research. 1984;3:323–364. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cornwall CE, Comeau S, McCulloch MT. Coralline algae elevate pH at the site of calcification under ocean acidification. Global Change Biology. 2017;23:4245–4256. doi: 10.1111/gcb.13673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aguirre J, Riding R, Braga JC. Diversity of coralline red algae: origination and extinction patterns from the Early Cretaceous to the Pleistocene. Paleobiology. 2000;26:651–667. doi: 10.1666/0094-8373(2000)026<0651:DOCRAO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diaz-Pulido G, Anthony KR, Kline DI, Dove S, Hoegh-Guldberg O. Interactions between ocean acidification and warming on the mortality and dissolution of coralline algae. Journal of Phycology. 2012;48:32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2011.01084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin S, Gattuso J-P. Response of Mediterranean coralline algae to ocean acidification and elevated temperature. Global Change Biology. 2009;15:2089–2100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.01874.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosler A, Perfectti F, Pena V, Aguirre J, Braga JC. Timing of the evolutionary history of Corallinaceae (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) Journal of Phycology. 2017;53:567–576. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noisette F, Egilsdottir H, Davoult D, Martin S. Physiological responses of three temperate coralline algae from contrasting habitats to near-future ocean acidification. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 2013;448:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ordoñez A, Wangpraseurt D, Lyndby NH, Kühl M, Diaz-Pulido G. Elevated CO2 leads to enhanced photosynthesis but decreased growth in early life stages of reef building coralline algae. Frontiers in Marine Science. 2018;5:495. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stillman JH, Armstrong E. Genomics are transforming our understanding of responses to climate change. BioScience. 2015;65:237–246. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biu219. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mardis ER. The impact of next-generation sequencing technology on genetics. Trends in Genetics. 2008;24:133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jamers A, Blust R, De Coen W. Omics in algae: paving the way for a systems biological understanding of algal stress phenomena? Aquatic Toxicology. 2009;92:114–121. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang G, et al. The oyster genome reveals stress adaptation and complexity of shell formation. Nature. 2012;490:49–54. doi: 10.1038/nature11413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim KM, Yang EC, Kim JH, Nelson WA, Yoon HS. Complete mitochondrial genome of a rhodolith, Sporolithon durum (Sporolithales, Rhodophyta) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26:155–156. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.819500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williamson C, Yesson C, Briscoe AG, Brodie J. Complete mitochondrial genome of the geniculate calcified red alga, Corallina officinalis (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) Mitochondrial DNA Part B. 2016;1:326–327. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2016.1172048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gabrielson PW, Hughey JR, Diaz-Pulido G. Genomics reveals abundant speciation in the coral reef building alga Porolithon onkodes (Corallinales, Rhodophyta) Journal of Phycology. 2018;54:429–434. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee JM, et al. Mitochondrial and Plastid Genomes from Coralline Red Algae Provide Insights into the Incongruent Evolutionary Histories of Organelles. Genome Biology and Evolution. 2018;10:2961–2972. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evy222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Im S, et al. De novo assembly of transcriptome from the gametophyte of the marine red algae Pyropia seriata and identification of abiotic stress response genes. Journal of Applied Phycology. 2015;27:1343–1353. doi: 10.1007/s10811-014-0406-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chan CX, et al. Porphyra (Bangiophyceae) transcriptomes provide insights into red algal development and metabolism. Journal of Phycology. 2012;48:1328–1342. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2012.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Defraia C, Mou Z. The role of the Elongator complex in plants. Plant Signal Behavior. 2011;6:19–22. doi: 10.4161/psb.6.1.14040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Glatt S, Séraphin B, Müller CWJT. Elongator: transcriptional or translational regulator? Transcription. 2012;3:273–276. doi: 10.4161/trns.21525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Falcone A, Nelissen H, Fleury D, Van Lijsebettens M, Bitonti MB. Cytological investigations of the Arabidopsis thaliana elo1 mutant give new insights into leaf lateral growth and elongator function. Annals of Botany. 2007;100:261–270. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bryant DM, et al. A tissue-mapped axolotl de novo transcriptome enables identification of limb regeneration factors. Cell Reports. 2017;18:762–776. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon P, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome research. 2003;13:2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heymans K, Kuiper M, Maere S. BiNGO: a Cytoscape plugin to assess overrepresentation of Gene Ontology categories in Biological Networks. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3448–3449. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schönknecht G, et al. Gene transfer from bacteria and archaea facilitated evolution of an extremophilic eukaryote. Science. 2013;339:1207–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1231707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nozaki H, et al. A 100%-complete sequence reveals unusually simple genomic features in the hot-spring red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae. BMC Biology. 2007;5:28. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-5-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collén J, et al. Genome structure and metabolic features in the red seaweed Chondrus crispus shed light on evolution of the Archaeplastida. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:5247–5252. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221259110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clay NK, Nelson T. The recessive epigenetic swellmap mutation affects the expression of two step II splicing factors required for the transcription of the cell proliferation gene Struwwelpeter and for the timing of cell cycle arrest in the Arabidopsis leaf. Plant Cell. 2005;17:1994–2008. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.032771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Finn RD, et al. The Pfam protein families database: towards a more sustainable future. Nucleic Acids Research. 2015;44:D279–D285. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Snyders S, Kohorn BD. TAKs, thylakoid membrane protein kinases associated with energy transduction. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274:9137–9140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hardie DG. Plant protein serine/threonine kinases: classification and functions. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1999;50:97–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wheeler GL, Miranda-Saavedra D, Barton GJ. Genome analysis of the unicellular green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii indicates an ancient evolutionary origin for key pattern recognition and cell-signaling protein families. Genetics. 2008;179:193–197. doi: 10.1534/genetics.107.085936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sawhney N, Crooks C, Chow V, Preston JF, St John FJ. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of carbohydrate utilization by Paenibacillus sp. JDR-2: systems for bioprocessing plant polysaccharides. BMC genomics. 2016;17:131–131. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-2436-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Funkhouser JD, Aronson NN. Chitinase family GH18: evolutionary insights from the genomic history of a diverse protein family. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2007;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rahman MA, Halfar J. First evidence of chitin in calcified coralline algae: new insights into the calcification process of Clathromorphum compactum. Scientific Reports. 2014;4:6162. doi: 10.1038/srep06162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu W, Huang X, Lin J, He M. Seawater acidification and elevated temperature affect gene expression patterns of the pearl oyster Pinctada fucata. Plos One. 2012;7:e33679. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goodson HV, Hawse WF. Molecular evolution of the actin family. Journal of Cell Science. 2002;115:2619–2622. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.13.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoef-Emden K, et al. Actin phylogeny and intron distribution in Bangiophyte red algae(Rhodoplantae) Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2005;61:360–371. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-0366-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Durak GM, Brownlee C, Wheeler GL. The role of the cytoskeleton in biomineralisation in haptophyte algae. Scientific Reports. 2017;7:15409. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-15562-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tyszka J, et al. Form and function of F-actin during biomineralization revealed from live experiments on foraminifera. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019;116:201810394. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1810394116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen B, Zhong D, Monteiro A. Comparative genomics and evolution of the HSP90 family of genes across all kingdoms of organisms. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:156. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whittaker CA, Hynes RO. Distribution and evolution of von Willebrand/Integrin A domains: widely dispersed domains with roles in cell adhesion and elsewhere. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 2002;13:3369–3387. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e02-05-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Johnson KM, Hofmann GE. Transcriptomic response of the Antarctic pteropod Limacina helicina antarctica to ocean acidification. BMC Genomics. 2017;18:812. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-4161-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gómez-Lemos LA, Doropoulos C, Bayraktarov E, Diaz-Pulido G. Coralline algal metabolites induce settlement and mediate the inductive effect of epiphytic microbes on coral larvae. Scientific Reports. 2018;8:17557–17557. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-35206-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haas Brian J, Papanicolaou Alexie, Yassour Moran, Grabherr Manfred, Blood Philip D, Bowden Joshua, Couger Matthew Brian, Eccles David, Li Bo, Lieber Matthias, MacManes Matthew D, Ott Michael, Orvis Joshua, Pochet Nathalie, Strozzi Francesco, Weeks Nathan, Westerman Rick, William Thomas, Dewey Colin N, Henschel Robert, LeDuc Richard D, Friedman Nir, Regev Aviv. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-seq using the Trinity platform for reference generation and analysis. Nature Protocols. 2013;8(8):1494–1512. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fu L, Niu B, Zhu Z, Wu S, Li W. CD-HIT: accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:3150–3152. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zdobnov EM, et al. OrthoDB v9.1: cataloging evolutionary and functional annotations for animal, fungal, plant, archaeal, bacterial and viral orthologs. Nucleic Acids Research. 2017;45:D744–D749. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee J, et al. Analysis of the draft genome of the red seaweed Gracilariopsis chorda provides insights into genome size evolution in Rhodophyta. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2018;35:1869–1886. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msy081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Apweiler R, et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32:D158–D169. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finn RD, Clements J, Eddy SR. HMMER web server: interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Research. 2011;39:W29–W37. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ashburner M, et al. Gene ontology: tool for the unification of biology. Nature Genetics. 2000;25:25. doi: 10.1038/75556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biology. 2015;16:157. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.micropan: Microbial pan-genome analysis v. 1.2 (2018).

- 73.dplyr: A Frammar of Data Manipulation v. 0.8.0.1 (2019).

- 74.tibble: Simple data frames v. 2.1.1 (2019).

- 75.Conway JR, Lex A, Gehlenborg N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2938–2940. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Larsson A. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:3276–3278. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–2690. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.FigTree (University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, 2006).

- 79.Freshwater DW, Fredericq S, Butler BS, Hommersand MH, Chase MW. A gene phylogeny of the red algae (Rhodophyta) based on plastid rbcL. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91:7281–7285. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pueschel CM, Cole KM. Rhodophycean pit plugs: An ultrastructural survey with taxonomic implications. American Journal of Botany. 1982;69:703–720. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1982.tb13310.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ragan MA, et al. A molecular phylogeny of the marine red algae (Rhodophyta) based on the nuclear small-subunit rRNA gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994;91:7276. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saunders GW, Bailey JC. Phylogenesis of pit-plug-associated features in the Rhodophyta: inferences from molecular systematic data. Canadian Journal of Botany. 1997;75:1436–1447. doi: 10.1139/b97-858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Raw data has been deposited in NCBI under BioProject PRJNA518156. The Transcriptome Shotgun Assembly Fasta files have been deposited at DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank under the accession numbers GHIN00000000, GHIO00000000, GHIP00000000, and GHIV00000000 for Sporolithon cf. durum, Porolithon cf. onkodes, Lithothamnion cf. proliferum, and Lithophyllum cf. insipidum, respectively.