Abstract

Background:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) as a public health concern is increasingly circulating by causative agents of Leishmania tropica and L. major in Iran. As regard to recent treatment failure and controlling problems, the accurate elucidation of heterogeneity traits and taxonomic status of Leishmania spp. should be broadly addressed by policymakers. This study was designed to determine the genetic variability and molecular characterization of L. major and L. tropica from Iranian CL patients.

Methods:

One hundred positive Giemsa-stained slides were taken from clinical isolates of CL at Pol-e-Dokhtar County, Southwest Iran, from May 2014 to Sep 2016. DNAs were directly extracted and amplified by targeting ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) gene following microscopic observation. To identify Leishmania spp. amplicons were digested by restriction enzyme HaeIII subsequent PCR-RFLP technique. To reconfirm, the isolates were directly sequenced to conduct diversity indices and phylogenetic analysis.

Results:

Based upon the RFLP patterns, 84 and 16 isolates were explicitly identified to L. tropica and L. major respectively. No co-infection was found in clinical isolates. The high genetic diversity of L. tropica (Haplotype diversity 0.9) was characterized compared to L. major isolates (Hd 0.476). The intra-species diversity for L. tropica and L. major isolates corresponded to 3%–3.9% and 0%–0.4%, respectively.

Conclusion:

Findings indicate the L. tropica isolates with remarkable heterogeneity than L. major are predominantly circulating at Pol-e-Dokhtar County. Occurrence of high genetic variability of L. tropica may be noticed in probable treatment failure and/or emerging of new haplotypes; however, more studies are warranted from various geographic regions of Southwest Iran, using large sample size.

Keywords: Cutaneous leishmaniasis, Genetic diversity, PCR-RFLP, Leishmania tropica, Leishmania major, Iran

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a group of neglected vector-borne disease which presents by various clinical appearances and heterogeneity traits (1, 2). CL is dispersed in 20 out of 31 Iranian provinces with overall prevalence of 1.8% to 37.9% and estimated annual incidence of 26630 cases (2–4). In order of clinical-epidemiology importance, two well-known etioparasitological agents, Leishmania major, and L. tropica are principal causative agents of CL in Iran (3, 5). The genetic diversity of the genus Leishmania is discussed as one of the most controversial issues among the endemic areas. The genetic heterogeneity of Leishmania parasite may lead to emergence of diverse phenotypic aspects, emergent sub-species/strains, and formation of novel haplotypes, and subsequently rapid generation of drug-resistance alleles (6–9). Currently, L. major and L. tropica are unambiguously circulating in Lorestan province, where it is addressed as a neglected focus of leishmaniasis in Southwest Iran (10).

To evaluate genetic diversity examination of Leishmania spp. several nuclear and mitochondrial DNA genes have tested, including Cytochrome b (kDNA maxicircle), microsatellites, gp63, 18S-rRNA, mini-exon, HSP-70 and ribosomal internal transcribed spacer regions (ITS-rDNA) (3, 11–17). The ITS-rDNA region can utilize to understand evolutionary hypotheses of Leishmania as a result of low intracellular polymorphism and to be conserved regions (18).

As regard to recent drug resistance and controlling problems, the precise elucidation of single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) and taxonomic status of Leishmania spp. by more sensitive strategies could be generally noticed by regional policymakers. The aim of this study was to determine molecular characterization and genetic variability of L. major and L. tropica from Pol-e-Dokhtar County, Southwest Iran.

Methods

Study area

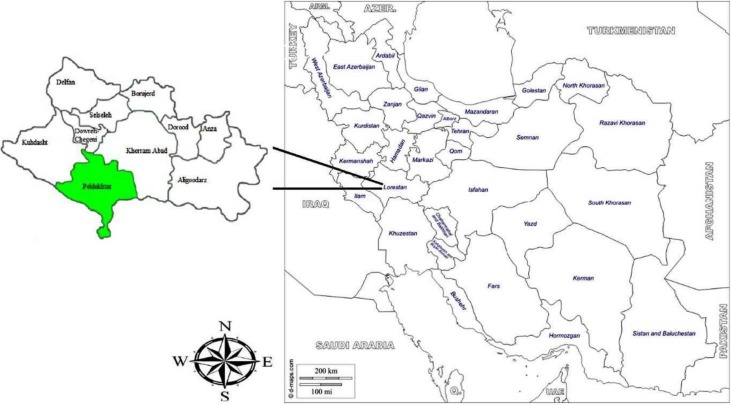

Pol-e-Dokhtar County is located in the South of the Lorestan Province (Fig. 1). This county occupied 3615 square km, and according to the Statistical Center of Iran (SCI), the population size is 75,327. Pol-e-Dokhtar city has an altitude of 673 meters above sea level. The annual average temperature of the city is 11.9°C.

Fig. 1:

Map of the Lorestan Province and Pol-e-Dokhtar County presenting study locations in Southwest Iran

Sampling and microscopic examination

The lesions of suspected patients to CL were sampled from Pol-e-Dokhtar Health Center, from May 2014 to Sep 2016. Overall, 100 microscopically confirmed slides were collected. The samples were smeared on microscopic slides, dried, and stained by Giemsa. Leishmania infections were identified under light microscope with high magnification (×1000). Demographic and clinical data of each patient including age, sex, locality, the number of lesions, and location of lesion were recorded using a questionnaire.

Extraction of Total Genomic DNA, PCR amplification and restriction fragment length polymorphism for ITS1-rDNA

DNA of Leishmania was directly extracted from positive slides based upon the Phenol-chloroform protocol (6). All Giemsa-stained slides were washed with ethanol and covered with 250μL lysis buffer (50mM NaCl, 50 mMTris, 10mM EDTA, pH 7.4, 1% v/v Triton x-100 and 100 μg of proteinase k per ml). To accomplish, cell lysis samples were then incubated at 56°C for 3 h or overnight. The obtained DNA was re-suspended in 30 μL double-distilled water and stored at −20 °C until molecular doings.

The single round PCR was performed to identify the Leishmania infection by targeting ribosomal internal transcribed spacer 1 (ITS1) using previously designed specific primers, LITSR (5′-CTGGATCATTTTCCGATG-3′) as Forward primer and L5.8S (5′TGATACCACTTATCGCACTT-3′) as reverse primer (19). The following program was used to carry out PCR: initial denaturing cycle at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 47 °C for 30 sec, 72 °C for 1 min and finally 1 cycle of 72°C for 5 min. PCR products were run on 1.5%gel agarose stained with ethidium bromide and observed under UV light.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) was performed on PCR products to determine the parasite species. Endonuclease reaction of ITS1-rDNA gene was done in a volume of 30μL containing 2μL of BsuRI (HaeIII) with cut site GG↓CC, 10μL of PCR products, 2μL of 10× buffer, and 16μL of distilled water for 15 min at 37°C. Finally, the digested fragments were revealed using 3% gel agarose and UV light.

Sequencing and phylogenetic analyses

To re-confirm the RFLP findings, amplicons were randomly purified and sequenced by targeting ITS1-rDNA gene using ABI 3130X automatic sequencer at the Bioneer Company, South Korea. Contigs (overlapped sequences) were aligned (http://multalin.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin) and edited at consensus positions using Sequencher Tmv.4.1.4 Software (Gene Codes Corporation). The percent identity and divergence (pairwise distances) among sequenced isolates were drawn using the MegAlign program from Laser Gene Bio Computing Software Package (DNASTAR, Madison, WI). To demonstrate the taxonomic status of identified isolates, the phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA 5.05 software based on Maximum Likelihood algorithm and kimura two-parameter model. The accuracy of phylogenetic tree was evaluated by 1000 bootstrap re-sampling. The Trypanosoma brucei (Accession number: JN673390) and Leishmania mexicana (Accession number: AF466383) were considered as out-group branches. The diversity indices (haplotypes diversity [Hd] and nucleotide diversity [π]) was calculated by DnaSP software version 5.10 (20).

Results

The demographic and clinical data of CL cases based on sex, age group, and location of lesion are given in Table 1. The vast majority infection was identified in 20–29 yr olds (25%) than other groups and in males (70%). The most lesions located at hand (53%) and foot (26%) (Table 1). The ITS1-rDNA gene (target 361bp) was successfully amplified by single round PCR for all Leishmania isolates.

Table 1:

Frequency of CL cases based on sex, age group and location of lesion in Poldokhtar County, Iran in 2014 to 2016

| Variable | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 70 |

| Female | 30 | |

| Age group (according to years) | <9 | 13 |

| 0–19 | 21 | |

| 20–29 | 25 | |

| 30–39 | 14 | |

| 40–49 | 15 | |

| 50≤ | 12 | |

| Location of lesion | Hand | 53 |

| Foot | 26 | |

| Face | 13 | |

| Hand and foot | 2 | |

| Hand and face | 5 | |

| Hand, foot and face | 1 |

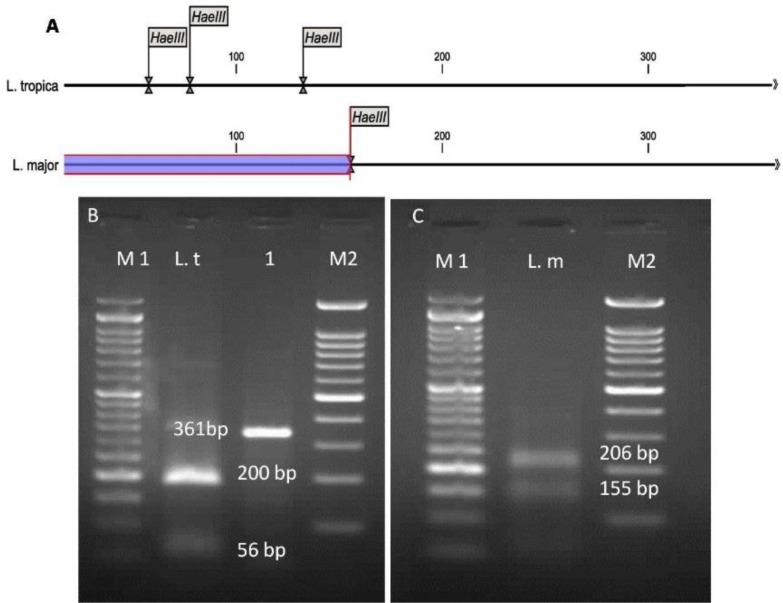

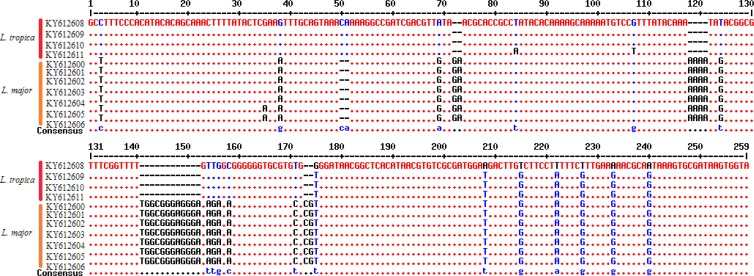

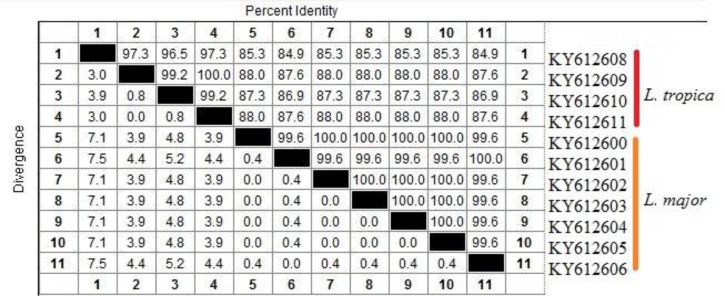

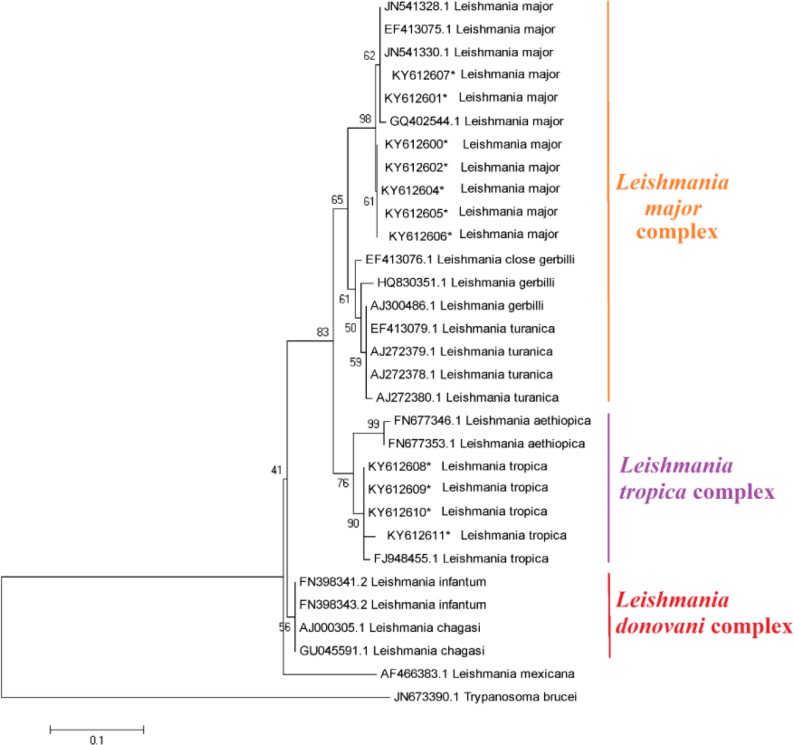

The in-silico prediction of BsuR1 restriction enzyme for ITS1-rDNA gene of L .major and L. tropica is shown in Fig. 2A. Based upon the RFLP digested patterns, 84 and 16 isolates were identified to L. tropica (fragments 57bp, 56bp and 200bp) and L. major (fragments 155bp and 206bp) isolates, respectively (Fig. 2 B–C). No co-infection was found in identified isolates. The high genetic diversity of L. tropica (Hd 0.9) was characterized compared to L. major (Hd 0.476). L. tropica sequences (0.02176) had more nucleotide diversity than L. major isolates (0.00183) (Table 2). The multiple sequence alignment of ITS1-rDNA gene for L .major and L. tropica is shown in Fig. 3. The intra-species diversity and identity for L. tropica isolates were 3–3.9% and 96–97.3% while, for L. major isolates corresponded to 0%–0.4% and 99.6%, respectively (Fig. 4). The topology of constructed phylogenetic tree disclosed that the L. major (Accession nos: KY612600-KY612607) and L. tropica (Accession nos: KY612608-KY612611) were grouped with bootstrap value of higher than 60% in their specific complex (Fig. 5). The Trypanosoma brucei and Leishmania mexicana were considered as out-group branches.

Fig. 2:

A: In-silico prediction of HaeIII restriction enzyme for ITS1-rDNA gene in the L. major and L. tropica. The digested fragments due to PCR-RFLP process in Pol-e Dokhtar County based on ITS1-rDNA gene. B: M1: 50bp ladder marker, L. t: L. tropica (fragments 57bp, 56bp, and 200bp), Lane 1: The amplified Leishmania spp. in infected patients (361 bp), M2: 100 bp ladder marker. C: L. m: L. major (fragments 155 bp and 206 bp)

Table 2:

Diversity and neutrality indices of Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica based on nucleotide sequences of internal transcribed spacer 1–rDNA gene in Pol-e-Dokhtar County, Lorestan Province, Iran N: number of isolates; Hn: number of haplotypes; Hd: haplotype diversity; Nd: nucleotide diversity.

| Parasite | N | Hn | Hd± SD | Nd (π) ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. major | 10 | 2 | 0.476±0.171 | 0.00183±0.00157 |

| L. tropica | 10 | 4 | 0.900±0.02592 | 0.02176±0.00088 |

Fig. 3:

The multiple sequence alignment of ITS1-rDNA gene for L .major and L. tropica

Fig. 4:

The intra/inter species identity/diversity between L .major and L. tropica identified in this study

Fig. 5:

Maximum Likelihood bootstrap tree indicating the relationships of the haplotypes of ITS1-rDNA gene for L .major and L. tropica. Only bootstrap values of higher than 60% are indicated on each branch. The Trypanosoma brucei (Accession number: JN673390) and Leishmania mexicana (Accession number: AF466383) were considered as out-group branches. In this study, the registered sequences marked by asterisk (*)

Discussion

In this investigation, different levels of genetic diversity of L. tropica and L. major isolates were identified in clinical isolates of CL patients from Southwest Iran, inferred by ITS1-rDNA nucleus gene.

L. tropica (n=86%) was firmly determined by RFLP and phylogenetic analyses as the principal species responsible for CL in the Pol-e-Dokhtar County, where here was not an eligible information concerning taxonomic status and heterogeneity traits of parasite causing CL (10). Pol-e-Dokhtar County is known as a neglected hyperendemic focus of leishmanisis, which neighbored with Khuzestan and Ilam provinces. Current finding shows that the most CL infections were occurred in males with age group 20–29 yr old. This may be males frequently work in the field places and females cover their body and apply Hijab because of religion (3).

In this study, nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer region as a universal DNA barcode marker was used to identify probable haplotypes and evolutionary relationship of L. tropica and L. major because of its conserve features and be multi-copy (18).

In the current findings, the L. tropica isolates demonstrated a greater genetic diversity (Hd: 0.9 and nucleotide diversity; 0.02176) than L. major (hd: 0.476 and nucleotide diversity: 0.00183). This may be described by the genomic characters of ITS-rDNA. GC content of L. tropica is generally lower than L. major (59.7%), therefore the stability of triple hydrogen bonds of the GC pair and stacking interaction is faced with a slippage (21, 22). Furthermore, this heterogeneity may elucidate by several facts; First: presence of turnover mechanisms; unequal crossing over/transposition and slippage in the sequence length of parasite(23). Second: lack of any bottleneck effects.

One of the limitations of current investigation is that the study area was highly confined and the isolates are relatively small to be inferred for more extensive larger-scale genetic diversities, However; we cannot explicitly estimate the heterogeneity levels of L. tropica and L. major in the region. On the one hand, the employing evolutionary mitogenome markers (e.g. Cytochrome b or Cyt c oxidase subunit I) can identify the new haplotypes than nuclear genes (e.g., ITS1-rDNA).

Up to now, the genetic diversity of Leishmania spp. have been reported by several regional researchers by targeting nucleus (ITS-rDNA) and/or mitochondrial (kDNA and Cyt b) markers from various endemic foci of Iran.

The sequence alignment of kDNA gene demonstrated a high genetic diversity of L. major from different rural and urban areas of Fars Province (Southern Iran) (24).

However, by targeting ITS-rDNA gene a high genetic polymorphism of L. major (7.3%) than L. tropica isolates (3.6%) had shown in various locations of Iran (25), whilst we contrary found more variations in L. tropica to be compared to L. major isolates.

A high genetic diversity of L. tropica compared to L. major isolates by targeting both ITS-rDNA and Cyt b genes had shown from Southwestern Iran (Khuzestan Province) (3).

In addition, by using kDNA, CL causing strains of L. major in southern Iran have a significant genetic variation (26).

Tashakori et al. have demonstrated the genetic heterogeneity of Iranian isolates of L. major using single-strand conformation polymorphism and sequence analysis of the ribosomal ITS (27).

In another study, genetically high polymorphism of L. major isolates from CL patients was demonstrated in Central Iran (Isfahan Province) (28).

The considerable genetic diversity of L. major in RNA polymerase II largest subunit (RPOIILS) and lack of the genetic diversity in mitochondrial DNA polymerase beta (DPOLB) were reported in Central Iran (Isfahan Province) (29).The genetic diversity in L. major strains was determined belong to different endemic areas of Iran using kDNA, there was considerable diversity between strains of different regions and even between isolates that belong to the same area (30).

This study revealed that both of main causative agents of CL are present in Pol-e-Dokhtar County. In accordance with previous studies, L. tropicawas found predominant species in the study area (10, 31). L. tropicaand L. major were the main causative agents of CL in Pol-e-Dokhtar County with the occurrence of 82.2 and 35.3% respectively (10, 31).

In this study, the most affected part of the body was belonged to hand, foot, and face, respectively. This finding is in accordance with the study conducted in the same area (31).

Conclusion

The L. tropica isolates with remarkable heterogeneity than L. major are predominantly circulating at Pol-e-Dokhtar County. Occurrence of high genetic variability of L. tropica may be noticed in probable treatment failure and/or emerging of new haplotypes; however, more studies are warranted from various geographic regions of Southwest Iran, using large sample size.

Ethical considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their deep thanks to all Lab Staffs of the Parasitology, and Cellular and Molecular Biology Research Center of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences. No financial support was received for this study.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Desjeux P. (2001). The increase in risk factors for leishmaniasis worldwide. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 95:239–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvar J, Vélez ID, Bern C, et al. (2012). Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One, 7:e35671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spotin A, Rouhani S, Parvizi P. (2014). The associations of Leishmania major and Leishmania tropica aspects by focusing their morphological and molecular features on clinical appearances in Khuzestan province, Iran. BioMed Res Int, 2014: 913510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Badirzadeh A, Mohebali M, Asadgol Z, et al. (2017). The burden of leishmaniasis in Iran: findings from the global burden of disease from 1990 to 2010. Asian Pac J Trop Dis, 7:513–518. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bordbar A, Parvizi P. (2014). High density of Leishmania major and rarity of other mammals’ Leishmania in zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis foci, Iran. Trop Med Int Health, 19:355–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spotin A, Rouhani S, Ghaemmaghami P, et al. (2015). Different morphologies of Leishmania major amastigotes with no molecular diversity in a neglected endemic area of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Iran Biomed J, 19:149–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharbatkhori M, Spotin A, Taherkhani H, et al. (2014). Molecular variation in Leishmania parasites from sandflies species of a zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in northeast of Iran. J Vector Borne Dis, 51:16–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rouhani S, Mirzaei A, Spotin A, Parvizi P. (2014). Novel identification of Leishmania major in Hemiechinus auritus and molecular detection of this parasite in Meriones libycus from an important foci of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. J Infect Public Health, 7:210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spotin A, Parvizi P. (2016). Comparative study of viscerotropic pathogenicity of Leishmania major amastigotes and promastigotes based on identification of mitochondrial and nucleus sequences. Parasitol Res, 115:1221–1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kheirandish F, Sharafi AC, Kazemi B, et al. (2013). First molecular identification of Leishmania species in a new endemic area of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Lorestan, Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med, 6:713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cupolillo E, Brahim LR, Toaldo CB, et al. (2003). Genetic polymorphism and molecular epidemiology of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis from different hosts and geographic areas in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol, 41:3126–3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yatawara L, Le TH, Wickramasinghe S, Agatsuma T. (2008). Maxicircle (mitochondrial) genome sequence (partial) of Leishmania major: gene content, arrangement and composition compared with Leishmania tarentolae. Gene, 424:80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parvizi P, Ready P. (2008). Nested PCRs and sequencing of nuclear ITS-rDNA fragments detect three Leishmania species of gerbils in sandflies from Iranian foci of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis. Trop Med Int Health, 13:1159–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montalvo A, Fraga J, Monzote L, et al. (2010). Heat-shock protein 70 PCR-RFLP: a universal simple tool for Leishmania species discrimination in the New and Old World. Parasitology, 137:1159–1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rastaghi Are, Spotin A, Khataminezhad Mr, et al. (2017). Evaluative Assay of Nuclear and Mitochondrial Genes to Diagnose Leishmania Species in Clinical Specimens. Iran J Public Health, 46:1422–1429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seyyedtabaei Sj, Rostami A, Haghighi A, et al. (2017). Detection of Potentially Diagnostic Leishmania Antigens with Western Blot Analysis of Sera from Patients with Cutaneous and Visceral Leishmaniases. Iran J Parasitol, 12:206–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moshrefi M, Spotin A, Kafil HS, et al. (2017). Tumor suppressor p53 induces apoptosis of host lymphocytes experimentally infected by Leishmania major, by activation of Bax and caspase-3: a possible survival mechanism for the parasite. Parasitol Res, 116:2159–2166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillis DM, Moritz C, Porter CA, Baker RJ. (1991). Evidence for biased gene conversion in concerted evolution of ribosomal DNA. Science, 251:308–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schönian G, Nasereddin A, Dinse N, et al. (2003). PCR diagnosis and characterization of Leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis, 47:349–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rozas J, Sánchez-DelBarrio JC, Messeguer X, Rozas R. (2003). DnaSP, DNA polymorphism analyses by the coalescent and other methods. Bioinformatics, 19:2496–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ivens AC, Peacock CS, Worthey EA, et al. (2005). The genome of the kinetoplastid parasite, Leishmania major. Science, 309:436–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schönian G, Schnur L, El Fari M, et al. (2001). Genetic heterogeneity in the species Leishmania tropica revealed by different PCR-based methods. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg, 95:217–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Herwerden L, Gasser RB, Blair D. (2000). ITS-1 ribosomal DNA sequence variants are maintained in different species and strains of Echinococcus. Int J Parasitol, 30:157–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oryan A, Shirian S, Tabandeh M-R, et al. (2013). Genetic diversity of Leishmania major strains isolated from different clinical forms of cutaneous leishmaniasis in southern Iran based on minicircle kDNA. Infect Genet Evol, 19:226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajjaran H, Mohebali M, Mamishi S, et al. (2013). Molecular identification and polymorphism determination of cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis agents isolated from human and animal hosts in Iran. BioMed Res Int, 2013: 789326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shirian S, Oryan A, Hatam GR, et al. (2016). Correlation of genetic heterogeneity with cytopathological and epidemiological findings of Leishmania major isolated from cutaneous leishmaniasis in Southern Iran. Acta Cytol, 60:97–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tashakori M, Kuhls K, Al-Jawabreh A, et al. (2006). Leishmania major: genetic heterogeneity of Iranian isolates by single-strand conformation polymorphism and sequence analysis of ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer. Acta Trop, 98:52–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dabirzade M, Sadeghi HMM, Hejazi H, Baghaii M. (2012). Genetic polymorphism within the Leishmania major in two hyper endemic areas in Iran. Arch Iran Med,15(3):151–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eslami G, Salehi R, Khosravi S, Doudi M. (2012). Genetic analysis of clinical isolates of Leishmania major from Isfahan, Iran. J Vector Borne Dis, 49:168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahmoudzadeh Niknam H, Ajdary S, Riazi-Rad F, et al. (2012). Molecular epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis and heterogeneity of Leishmania major strains in Iran. Trop Med Int Health, 17:1335–1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kheirandish F, Sharafi AC, Kazemi B, et al. (2013). Identification of Leishmania species using PCR assay on giemsa-stained slides prepared from cutaneous leishmaniasis patients. Iran J Parasitol, 8:382–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]