Abstract

Object:

There remains uncertainty regarding the appropriate level of care and need for repeating neuroimaging among children with mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) complicated by intracranial injury (ICI). To identify knowledge gaps and highlight avenues for future investigation, this study’s objective was to investigate physician practice patterns and decision making processes for these patients.

Methods:

We surveyed residents, fellows, and attending physicians from the following pediatric specialties: emergency medicine; general surgery; neurosurgery; and critical care. Participants came from 10 institutions in the United States and an email list maintained by the Canadian Neurosurgical Society. The survey asked respondents to indicate management preferences for and experiences with children with mTBI complicated by ICI, focusing on an exemplar clinical vignette of a 7-year-old female, Glasgow Coma Scale score 15, with a 5-mm subdural hematoma without midline shift after a fall down stairs.

Results:

The response rate was 52% (n=536). Overall, 326 (61%) respondents indicated they would recommend ICU admission for the child in the vignette. However, only 62 (12%) agreed/strongly agreed that this child was at high risk of neurological decline. Half of respondents (45%; n=243) indicated they would order a planned follow-up CT (29%; n=155) or MRI scan (19%; n=102), though only 64 (12%) agreed/strongly agreed that repeat neuroimaging would influence their management. Common factors that increased the likelihood of ICU admission included presence of a focal neurological deficit (95%; n=508 endorsed), midline shift (90%; n=480) or an epidural hematoma (88%; n=471). However, 42% (n=225) indicated they would admit all children with mTBI and ICI to the ICU. Notably, 27% (n=143) of respondents indicated they had seen one or more children with mTBI and intracranial hemorrhage experience a rapid neurological decline when admitted to a general ward in the last year, and 13% (n=71) had witnessed this outcome at least twice in the past year.

Conclusions:

Many physicians endorse ICU admission and repeat neuroimaging for pediatric mTBI with ICI, despite uncertainty regarding the clinical utility of those decisions. These results, combined with evidence that existing practice may provide insufficient monitoring to some high-risk children, emphasize the need for validated decision tools to aid the management of these patients.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, health services research, clinical decision making, survey research, intracranial injury

Introduction:

Head trauma is a leading public health issue affecting children, causing approximately 600,000 emergency department (ED) visits and up to 60,000 hospitalizations each year in the United States.6,34 Healthcare encounters for traumatic brain injury (TBI) are increasing; the rate of ED visits for TBI increased more than eight times faster than the rate of overall ED visits between 2006–2010.10,35 Generally characterized with a presenting Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score of 13–15,9 mild TBI (mTBI) accounts for more than 90% of new TBI diagnoses and represents an increasingly important sub-type of TBI management.10,30,35

Substantial research has been dedicated to identifying which children with mTBI should undergo acute head computed tomography (CT) imaging. With the goal of reducing the substantial variations in head CT utilization,33,37,41 three independent decisions tools were developed and validated in multicenter studies; these tools have significantly improved evidence-based guidance regarding mTBI imaging decisions.4,13,32,38

Comparatively less attention has been focused on the post-CT acute management of children with mTBI, including key questions such as the appropriate level-of-care and role of repeat neuroimaging. These questions have particular salience in the management of children with mTBI complicated by intracranial injury (ICI), where available evidence suggests that admission practices vary across specialties and that level-of-care decisions often fail to correlate with patients’ evidence-based risk.18,42 While there are emerging evidence-based tools to help guide level-of-care decisions,18 it remains unclear what considerations currently influence physician decision making in this population. Likewise, there remains ongoing debate and uncertainty regarding the role of and indications for repeat neuroimaging in the management of these patients.16,21,23,39

Survey studies offer an efficient means of describing current practice, identifying knowledge gaps, and highlighting areas requiring further investigation.7,31 With these motivations, we conducted a survey to characterize current practice patterns and identify influences on physician decision making in the post-neuroimaging acute care of children with mTBI complicated by ICI.

Methods:

Study Participants

This study was approved with exempt status by the Washington University in St. Louis Institutional Review Board (IRB) and was also approved by the IRB at each participating institution that deemed such oversight necessary.

Study participants came from ten institutions in the United States and from an email registry maintained by the Canadian Neurosurgical Society (see the online Appendix for a list of participating institutions).These centers were identified in part by solicitation at a meeting of the Pediatric Neurocritical Care Research Group. Study participants included attending and fellow physicians from the following pediatric disciplines involved in the care of mTBI: emergency medicine; general surgery; neurosurgery; and critical care. Senior (PGY-4 and above) general surgery and neurosurgery residents were also surveyed.

Survey Development

Following standard survey methods,29 we used literature review and input from a team of experts in clinical TBI practice and survey methodologies to develop a 50-item questionnaire to survey physicians about their attitudes and practices in the post-neuroimaging management of pediatric mTBI. Subsequently, we engaged in incremental evaluation and refinement of this preliminary tool, given the importance of pretesting in improving questionnaire quality.11 First, detailed cognitive interviews were conducted with eight clinical experts in pediatric mTBI who were not part of the research team.24,25 During these interviews, clinicians completed and provided feedback on the survey, including explaining what they thought the questions meant and how they arrived at their responses. Participants were paid $50.

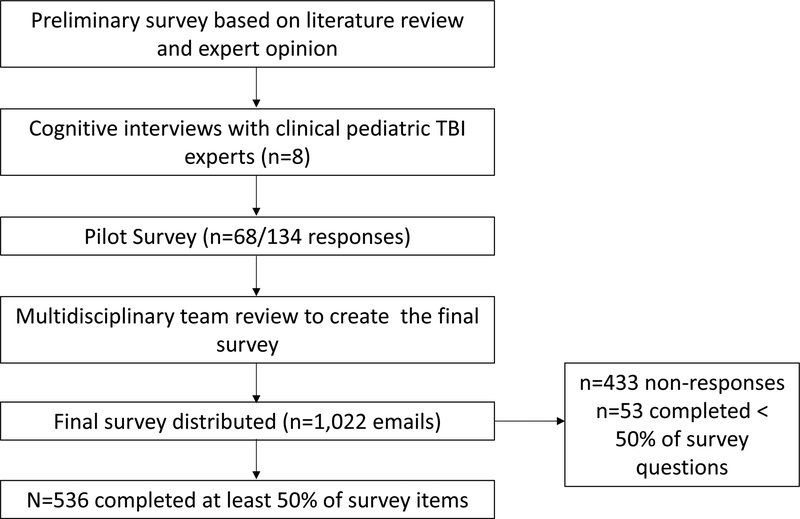

After revising the survey based on these interviews, a pilot study of the same specialties listed above was conducted at Washington University School of Medicine. Respondents were entered to win one of four $50 prizes. Out of 134 surveys emailed, 68 were returned. Pilot data were examined to gauge response rates and to identify questions with minimal variability in responses (e.g. nearly all respondents agreed/strongly agreed), which were often dropped. Based on multidisciplinary review of the pilot data, a final survey was developed. The survey development is detailed in Figure 1.

Figure 1:

Schematic depiction of the survey development process

Measures

The survey was divided into seven sections and took about 10 minutes to complete. Each of the first three sections focused on one of three clinical vignettes based in the ED. Respondents were asked to characterize the child’s injury and offer their professional opinions related to the appropriate acute management (e.g. next level-of-care and need for repeat neuroimaging). Multiple choice or 5-point Likert scaled response options ranging from “Strongly Disagree” (1 point) to “Strongly Agree” (5 points) were used. For this report, we focused on the vignette involving a 7-year-old girl, GCS 15, with a 5-mm subdural hematoma without midline shift after a fall down the stairs. This vignette was designed to illustrate a patient that available decision aids suggest is at low risk of neurological decline and therefore may not necessarily require ICU admission or planned repeat neuroimaging.1,8,17,18 The full vignette is provided in the Appendix. The two other vignettes involved children without ICI and will be described in a forthcoming manuscript focused on that patient population.

The fourth section (Influences on Decision Making) asked respondents to select the clinical and radiological factors that influenced their decisions about the appropriate level-of-care for children with mTBI. In addition, respondents used a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from “Never” [1] to “Always” [5]) to rate the frequency that other factors, e.g. one’s “gestalt impression” and standard institutional practice, influenced their decision-making. The fifth section (Recent Experiences with TBI patients) asked respondents about their experiences observing mTBI (GCS 13–15) patients undergoing unexpected neurological decline or radiologic progression during the last year. The sixth section (Shared Decision Making [SDM]) used a previously developed guide to ask respondents how frequently various factors (e.g. medicolegal concerns) served as barriers to utilizing SDM in the post-neuroimaging management of pediatric mTBI patients.28 The results from this section will be reported with the upcoming manuscript on the management of children without ICI. The final section (Demographics) included questions asking about respondents’ characteristics and practice settings.

Survey Administration

Site principal investigators at each institution collected and shared email addresses of potential eligible participants with the Data Coordination site at Washington University in St. Louis. The voluntary survey was then administered via unique emails sent using the Qualtrics server (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) from 8/3/2016 to 1/30/2017. Surveys were completed anonymously. After the initial distribution, four follow-up emails were sent approximately one week apart to potential participants. Participants were offered $10 compensation.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed surveys that had at least 50% of the survey items completed, and treated the remaining surveys as non-responses.2 Descriptive statistics were reported for all items. The primary outcome was the level-of-care recommended for the child with mTBI complicated by ICI in the vignette. The secondary outcome was the decision to order planned repeat neuroimaging for this child before hospital discharge. This outcome was defined as those who “Agreed” or “Strongly Agreed” with ordering a repeat CT or MRI scan for the child.

After conducting univariate logistic regression analyses, variables with p-values < 0.2 for each outcome were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model using backwards selection, and variables with p < 0.05 were retained. Complete case analysis was used given the small amount of missing data. For respondent specialty, missing data were grouped in the “Other” category. Respondents “not sure” if their institution was a Level 1 trauma center were grouped in the “No” category.

For increased statistical power, we treated items with Likert-scaled responses as continuous numerical variables and reported the mean and standard deviation for each item. In cases where the linearity of continuous predictors with the outcome was questionable, we ensured that the final model did not change with these variables re-categorized into 3 groups: Strongly Disagree/Disagree; Neutral; Agree/Strongly Agree (data not shown). Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results:

Out of 1,022 email surveys distributed, 536 respondents completed at least 50% of the survey items, yielding a 52% response rate. Emergency medicine constituted the largest group of respondents (38%), followed by critical care (25%), neurosurgery (21%), and general surgery (13%). Most respondents (63%) were attendings, male (52%), and worked at free-standing children’s hospitals (76%). Only 5% of respondents practiced in Canada. Demographic information is shown in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographic characteristics of survey respondents. P-values refer to the univariate logistic regression predicting the level-of-care decision (floor vs. ICU) for the child in the clinical vignette.

| All (%)* n=536 |

Admit Floor (%)* n=208 |

Admit ICU (%)* n=326 |

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specialty | ||||

| Emergency Medicine | 205 (38.3) | 109 (52.4) | 96 (29.5) | Ref |

| Critical Care | 132 (24.6) | 41 (19.7) | 91 (27.9) | < 0.01 |

| General Surgery | 68 (12.7) | 19 (9.1) | 49 (15.0) | < 0.01 |

| Neurosurgery | 112 (20.9) | 30 (14.4) | 80 (24.5) | < 0.01 |

| Other | 19 (3.5) | 9 (4.3) | 10 (3.1) | 0.63 |

| Training Level | ||||

| Resident | 91 (17.4) | 19 (9.3) | 72 (22.7) | Ref |

| Fellow | 101 (19.3) | 41 (20.1) | 60 (18.9) | < 0.01 |

| Attending | 331 (63.3) | 144 (70.6) | 185 (58.4) | < 0.01 |

| Age | ||||

| < 40 | 304 (58.1) | 118 (57.8) | 186 (58.7) | Ref |

| 40–49 | 135 (25.8) | 59 (28.9) | 75 (23.7) | 0.31 |

| ≥ 50 | 84 (16.1) | 27 (13.2) | 56 (17.7) | 0.30 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 247 (47.7) | 107 (52.7) | 140 (44.7) | 0.08 |

| Male | 271 (52.3) | 96 (47.3) | 173 (55.3) | Ref |

| Number of children with mTBI cared for per year | ||||

| 0–20 | 135 (25.9) | 41 (20.2) | 94 (29.7) | < 0.01 |

| 20–39 | 155 (29.7) | 57 (28.1) | 96 (30.3) | 0.12 |

| ≥ 40 | 232 (44.4) | 105 (51.7) | 127 (40.1) | Ref |

| Level 1 Trauma Center** | ||||

| Yes | 494 (94.3) | 193 (94.6) | 299 (94.0) | Ref |

| No | 30 (5.7) | 11 (5.4) | 19 (6.0) | 0.78 |

| Academic Medical Center*** | ||||

| Yes | 499 (95.2) | 197 (96.6) | 300 (94.3) | Ref |

| No | 25 (4.8) | 7 (3.4) | 18 (5.7) | 0.25 |

| Independent Children’s Hospital | ||||

| Yes | 400 (76.3) | 169 (82.8) | 230 (72.3) | Ref |

| No | 124 (23.7) | 35 (17.2) | 88 (27.7) | < 0.01 |

| Hospital Location | ||||

| Urban | 487 (93.1) | 186 (91.2) | 299 (94.3) | Ref |

| Non-Urban | 36 (6.9) | 18 (8.8) | 18 (5.7) | 0.17 |

| Hospital Region | ||||

| Canada | 27 (5.3) | 13 (6.4) | 13 (4.2) | Ref |

| Northeast | 55 (10.7) | 22 (10.8) | 33 (10.7) | 0.40 |

| South | 204 (39.7) | 74 (36.5) | 129 (41.8) | 0.18 |

| Midwest | 31 (6.0) | 10 (4.9) | 21 (6.8) | 0.18 |

| West | 197 (38.3) | 84 (41.4) | 113 (36.6) | 0.48 |

Percentage values reflect each level’s proportion of the total number of respondents within a given column (floor vs. ICU). Discrepancies in column totals reflect a small amount of missing data for ICU admission (n=2), Training Level (n=13), Age (n=13), Gender (n=18), Number mTBI Children Cared for (n=14), Level 1 Trauma Center (n=12), Academic Medical Center (n=12), Independent Children’s Hospital (n=12), Hospital Location (n=13), and Hospital Region (n=22).

Not sure Counted as “Not Level 1”

“Not Sure” counted as no

Respondents varied their responses regarding the appropriate terminology to characterize the injury in the vignette, which involved a 7-year-old girl with a GCS 15 head injury and a “5-mm subdural hematoma without midline shift or signs of herniation.” Most respondents (59%) endorsed the term “GCS 13–15 head injury with ICI,” while the remainder were split among the terms mild (13%), complicated mild (26%), moderate (28%), and severe (3%) TBI.

Responses to the vignette are listed in Table 2. Overall, 326 (61%) respondents indicated they would recommend ICU admission for the child in the vignette, though only 62 (12%) agreed/strongly agreed that this child was at high risk of neurological decline, with about one-third of respondents (36%; n=191) being neutral. The majority (77%, n=412) agreed/strongly agreed with involving family in their level-of-care decision. Slightly fewer than half of respondents (45%; n=243) indicated they would order a planned follow-up CT (29%; n=155) or MRI (19%; n=102) before hospital discharge, though only 64 (12%) agreed/strongly agreed that repeat neuroimaging would likely influence their clinical management. Planned repeat neuroimaging was most frequent among neurosurgeons (68%) and other unlisted specialties (68%), and less frequent among critical care physicians (49%), general surgeons (43%), and emergency physicians (29%).

Table 2:

Respondent opinions and management preferences regarding the clinical vignette involving a 7-year-old girl, Glasgow Coma Scale score 15, with a 5-mm subdural hematoma after a fall down the stairs. Responses either involved selecting all appropriate choices or a Likert-scale ranging from Strongly Disagree (1 point) to Strongly Agree (5 points).

| All* | Admit Floor* | Admit ICU* | P-Value** | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriate Consults, n (%) | NA | |||

| Critical Care | 124 (23.1) | 5 (2.4) | 119 (36.5) | |

| General Surgery | 327 (61.0) | 100 (48.1) | 227 (69.6) | |

| Neurosurgery | 532 (99.3) | 205 (98.6) | 325 (99.7) | |

| Pediatrics | 15 (2.8) | 8 (3.9) | 7 (2.2) | |

| Other | 2 (0.37) | 1 (0.48) | 1 (0.31) | |

| No consult indicated | 1 (0.19) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.31) | |

| How would you characterize the injury, n, (%) | NA | |||

| Mild TBI | 69 (12.9) | 30 (14.4) | 39 (12.0) | |

| Complicated mild TBI | 138 (25.8) | 59 (28.4) | 79 (24.4) | |

| GCS 13–15 head injury with intracranial injury | 317 (59.4) | 127 (61.1) | 189 (58.3) | |

| Moderate TBI | 150 (28.1) | 56 (26.9) | 93 (28.7) | |

| Severe TBI | 17 (3.2) | 1 (0.48) | 16 (4.0) | |

| Important to involve family in my decision regarding the appropriate level of care, mean (Stdev) | 3.98 (1.03) | 4.11 (0.94) | 3.90 (1.08) | 0.02 |

| This child is likely to undergo neurological decline, mean (Stdev) | 2.56 (0.80) | 2.31 (0.69) | 2.71 (0.83) | < 0.01 |

| I am confident in my assessment of the risk of neurological decline, mean (Stdev) | 3.85 (0.70) | 3.82 (0.71) | 3.88 (0.69) | 0.33 |

| Before discharge I would order a repeat CT scan, | 2.59 (1.23) | 2.27 (1.04) | 2.79 (1.30) | < 0.01 |

| Before discharge I would order a follow-up MRI scan, mean (Stdev) | 2.41 (1.10) | 2.17 (0.97) | 2.56 (1.16) | < 0.01 |

| Before discharge I would order repeat CT and/or MRI (Strongly Agree/Agree), n (%) | 243 (45.4) | 55 (26.4) | 187 (57.5) | < 0.01 |

| Repeat neuroimaging is likely to influence my clinical management, mean (stdev) | 2.36 (0.89) | 2.14 (0.75) | 2.49 (0.94) | < 0.01 |

| Within 2 weeks of discharge, this child should have a follow-up appointment with, n (%) | NA | |||

| A neurosurgeon | 478 (89.2) | 185 (88.9) | 291 (89.3) | |

| A trauma surgeon | 22 (4.1) | 6 (2.9) | 16 (4.9) | |

| Her primary care physician | 364 (67.9) | 136 (65.4) | 228 (69.9) | |

| A neurologist | 52 (9.7) | 9 (4.3) | 43 (13.2) | |

| Other | 43 (8.0) | 10 (4.8) | 33 (10.1) |

Discrepancies in column totals reflect the small amount of missing data for injury characterization (n=2), need for repeat CT (n=3), need for follow-up MRI (n=4), and influence of repeat neuroimaging (n=1).

P-values refer to the univariate logistic regression predicting the level-of-care decision (floor vs. ICU) for the child in the clinical vignette. “NA” indicates not applicable, meaning the variable was not tested as a potentially clinically informative predictor.

Beyond this specific vignette, the clinical and radiologic factors that generally influenced respondents’ decisions to admit children with mTBI complicated by ICI to the ICU are listed in Table 3. The most common factors influencing admission decisions included presence of a focal neurological deficit (95%), midline shift on CT (90%) and presence of an epidural hematoma (88%), with subdural hematoma (54%) and post-traumatic seizure (53%) being other common responses. Notably, 42% of respondents indicated they would admit all children with ICI to the ICU, regardless of the specific clinical or radiologic findings. Among other influences on decision-making, understanding of the medical literature (74% always/often utilized) and gestalt impression (69% always/often utilized) had the greatest impact (Appendix Table 1).

Table 3:

Clinical and radiologic influences indicating the need for ICU observation for children with GCS 13–15 head injuries and intracranial injury. Respondents were asked to select as many options as they agreed with (yes/no option). There were 3 missing responses.

| N (%) Agreeing | |

|---|---|

| I would admit all children with GCS head injuries and ICI to the ICU | 225 (42.1) |

| Post-traumatic seizure | 282 (52.9) |

| Severe mechanism of injury | 325 (61.0) |

| Midline shift (< 5 mm) | 480 (90.1) |

| Depressed skull fracture (depressed at least the width of the skull) | 322 (60.4) |

| Epidural hematoma (no midline shift) | 471 (88.4) |

| Subdural hematoma (no midline shift) | 289 (54.2) |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage (no midline shift or ventriculomegaly) | 235 (44.1) |

| Cerebral contusion (no midline shift) | 223 (41.8) |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage (no midline shift or ventriculomegaly) | 336 (63.0) |

| GCS score 14 | 98 (18.4) |

| GCS score 13 | 300 (56.3) |

| Presence of a focal neurological deficit | 508 (95.3) |

| Patient age < 2 years | 331 (62.1) |

| Other | 34 (6.4) |

When asked about their experiences with TBI patients in the past 12 months, 27% indicated they had seen one or more “clinically stable children with GCS 13–15 closed head injury and intracranial hemorrhage, experience a rapid neurological decline when admitted to a general ward” in the last year, and 13% had witnessed this outcome at least twice in the past year (Appendix Table 2). In addition, 35% indicated they had recently seen clinically stable children with GCS 13–15 closed head injury and intracranial hemorrhage require neurosurgical intervention for an enlarging hematoma seen on repeat imaging, in the absence of any neurological decline.

Variables Associated with Level-of-care Decisions

In univariate analysis, we found a number of factors associated with the level-of-care decision in the vignette. These included demographic factors (e.g. specialty, training level); feelings about the importance of involving family; beliefs about the child’s likely clinical course and the role of repeat neuroimaging; importance placed on understanding of the medical literature, gestalt impression, and malpractice liability; and recent experiences with TBI patients (Tables 1–2; Appendix Tables 1–2).

The multivariable model is shown in Table 4. In this analysis, critical care physicians (OR=2.2) general surgeons (OR=2.7), and neurosurgeons (OR=1.9) were at least twice as likely as emergency medicine physicians to recommend ICU admission. Physicians not working at a freestanding children’s hospitals were also twice as likely to recommend ICU admission (OR=1.8). In addition, providers who believed that the child was at risk of neurological decline (OR=1.6), those who relied on their “gestalt impression” (OR=1.4), and those who would obtain a repeat CT (OR=1.3) or MRI (OR=1.3) were more likely to recommend ICU admission.

Table 4:

Results of the multivariable analysis predicting the level-of-care recommended for the child in the clinical vignette. Odds ratios greater than 1 indicate increased likelihood of recommending ICU admission.

| Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | |

| Emergency Medicine | Ref |

| Critical Care | 2.2 (1.3 – 3.6) |

| General Surgery | 2.7 (1.4 – 5.0) |

| Neurosurgery | 1.9 (1.1 – 3.3) |

| Other | 0.32 (0.07 – 1.5) |

| Working at a freestanding Children’s hospital | |

| Yes | Ref |

| No | 1.8 (1.1 – 3.0) |

| Perceived likeliness of neurological decline | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) |

| Agreement with ordering a repeat CT scan | 1.3 (1.1 – 1.5) |

| Agreement with ordering a follow-up MRI scan | 1.3 (1.1 – 1.6) |

| Use of gestalt impression in decision making | 1.4 (1.1 – 1.8) |

Variables Associated with Repeat Neuroimaging Decisions

In univariate analysis, we found a number of factors significantly associated with the decision to order repeat neuroimaging in the vignette. These included demographic factors (e.g. provider specialty and age), beliefs about the child’s clinical course, and recent experiences with TBI patients. The complete univariate results are shown in Appendix Table 3.

The multivariable model of factors associated with planned repeat neuroimaging is shown in Table 5. In this analysis, physicians who favored ICU admission, those who believed repeat imaging was likely to influence their management, and respondents from neurosurgery and “other” unlisted specialties were more likely to order repeat imaging. Physicians from freestanding Children’s hospitals were less likely to order repeat imaging. Repeat imaging behavior also varied with age and training level, with repeat neuroimaging being more common among respondents older than 50 versus younger than 40 years and less frequent among attendings compared to residents.

Table 5:

Results of the multivariable analysis identifying factors associated with repeat neuroimaging decisions for the child in the clinical vignette. Odds ratios greater than 1 indicate increased likelihood of recommending repeat neuroimaging.

| Odds ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

|---|---|

| Would admit the child in Vignette #2 to the ICU | 2.9 (1.8–4.6) |

| Agreement that repeat neuroimaging is likely to change clinical management | 4.3 (3.1–6.1) |

| Specialty | |

| Emergency Medicine | Ref |

| Critical Care | 1.8 (1.02 –3.2) |

| General Surgery | 1.4 (0.70 – 3.0) |

| Neurosurgery | 3.4 (1.7 – 6.8) |

| Other | 8.2 (1.5 – 44.8) |

| Training Level | |

| Resident | Ref |

| Fellow | 1.3 (0.57 – 2.9) |

| Attending | 0.42 (0.18 – 0.97) |

| Age | |

| < 40 | Ref |

| 40 – 49 | 1.7 (0.85 – 3.4) |

| ≥ 50 | 4.6 (2.2 – 9.8) |

| Working at a freestanding Children’s hospital | |

| Yes | Ref |

| No | 1.8 (1.0 – 3.1) |

Discussion:

Although evidence-based indications for head CT imaging in pediatric mTBI have been established, there is a paucity of literature providing evidence for the routine post-neuroimaging management of these patients, including key topics such as the appropriate level-of-care and need for repeat neuroimaging.1,8,18,21,22 Understanding clinicians’ underlying cognitive processes is an essential component of evaluating management decisions and designing clinical decision-aids to support evidence-based practices.15,27 Nonetheless, there are limited data describing provider practices and preferences in this domain. This multicenter, multidisciplinary survey sought to fill that void. We found that most physicians would admit a neurologically intact child with a small subdural hematoma to the ICU and nearly half would order routine repeat neuroimaging, despite low concern regarding this child’s risk of neurological decline and low expectations regarding the utility of a follow-up scan. These practices varied across specialty and practice settings and appeared influenced by a number of provider beliefs, motivating and informing future studies of the appropriate level of care and need for repeat neuroimaging in this population.

Among children with mTBI and ICI that do not require upfront surgical intervention, one of the key decisions facing providers relates to the level-of-care required. In the vignette presented, we described a neurologically intact child with mTBI complicated by a small subdural hematoma, the most common type of ICI encountered in this population.18 To our knowledge, all studies of this population characterize the child in this vignette as low risk of neurological decline and recommend against ICU admission;1,8,17,18 yet 61% of respondents recommended ICU admission and 42% indicated they would recommend ICU admission for all children with ICI, though only 12% thought this child was at high risk high for neurological decline. These results highlight the wide variations and potentially avoidable resource utilization associated with current practices.

Beyond promoting potentially unnecessary ICU admissions, the variations in current practice may also place some patients at risk of significant harm. Supporting this notion, more than 25% of survey respondents reported that they had seen children with mTBI complicated by ICI experience neurological decline on a general ward in the last year. This result builds on existing evidence suggesting that current practice based on clinical gestalt not only sends many low risk children to the ICU, it also provides insufficient attention to the minority of patients truly at increased risk of neurological decline.18 These findings emphasize the need for rigorously validated decision tools to support evidence-based level-of-care decisions.

The secondary outcome in this study focused on the need for routine repeat neuroimaging following mTBI complicated by ICI, a source of ongoing debate and investigation. Although several studies have suggested that repeat neuroimaging may be low yield,3,12,39 other studies have reported high rates of radiologic progression.16 Given that nearly half of respondents supported ordering repeat neuroimaging but only 12% thought it was likely to change clinical management, higher level multicenter evidence is needed to guide this important decision. These studies should evaluate not only rates of radiologic progression but also the frequency with which such information influences clinical management. Such data, combined with consideration of the impact of ionizing radiation, may inform the development of evidence-based recommendations regarding the role of routine repeat CT or MRI imaging.5

Successful uptake of level-of-care and repeat neuroimaging decision aids will depend on rigorous dissemination and implementation strategies,19 which may be informed by the self-reported variations related to practice setting and provider beliefs revealed in this study. For example, the increased tendency toward ICU admission among those not at freestanding Children’s hospitals highlights the role of institutional resources and experience which should be considered in designing broadly generalizable implementation efforts. Likewise, we found that neurosurgeons were significantly more likely than other specialties to order planned repeat neuroimaging for the child in the vignette. Given the key role that neurosurgeons have in this decision making process, future implementation studies should focus on studying the acceptability and usability of imaging decision aids in this population.

This study has several strengths, including rigorous survey development methods, a large sample size, and a multidisciplinary and multicenter respondent base. Nonetheless, it also has limitations. First, our response rate (52%), while good, was still below the standard of 60% set by some authorities.26 However, survey response rates have decreased in recent years,40 and the association between a lower response rate and nonresponse bias is unclear.14,20 Second, to shorten the survey’s completion time, we included only one exemplar case of a patient with ICI. While this limited the breadth of situations tested, it allowed for more detailed assessment of provider attitudes and influences on decision making. Third, the survey respondents were concentrated at academic tertiary or quarternary institutions and also at freestanding children’s hospitals. Consequently, the results may not generalize to community settings or to children treated within a predominately adult institution, which may have different practices and availability of subspecialty care. Finally, this survey focused on physicians and did not investigate the perspectives of midlevel providers who are assuming a growing role in delivering emergency pediatric care.36

Conclusions:

This multicenter multidisciplinary survey indicated that there is wide variation in physician decisions related to the level of care and need for repeat neuroimaging for children with mTBI and ICI. The practices reported are associated with potentially avoidable resource utilization as well as possible patient harm. These observations, along with providers’ uncertainty regarding the clinical utility of their recommendations, highlight the need for continued efforts to advance evidence-based decision aids. Once developed and validated, such evidence-based approaches may form the foundation for consensus guidelines to direct the safe, resource-efficient management of these patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment:

We thank Drs. Nathan Kuppermann and James Holmes for their insightful comments related to this study. We thank Dr. Jacob Baranoski for his help with the survey administration.

Funding Source: This work was supported by a grant from the Washington University School of Medicine Faculty Practice Plan (FPP-1501) to Drs. Limbrick, Greenberg, and Brownson. Research reported in this publication was also supported by the Washington University Institute of Clinical and Translational Sciences grant UL1TR002345 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), as well as funding from the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation to Dr. Pineda.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors report no conflict of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper

References:

- 1.Ament JD, Greenan KN, Tertulien P, Galante JM, Nishijima DK, Zwienenberg M: Medical necessity of routine admission of children with mild traumatic brain injury to the intensive care unit. J Neurosurg Pediatr 19:668–674, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Association for Public Opinion Research: Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys, in, ed 9th edition, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aziz H, Rhee P, Pandit V, Ibrahim-Zada I, Kulvatunyou N, Wynne J, et al. : Mild and moderate pediatric traumatic brain injury: replace routine repeat head computed tomography with neurologic examination. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 75:550–554, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Babl FE, Borland ML, Phillips N, Kochar A, Dalton S, McCaskill M, et al. : Accuracy of PECARN, CATCH, and CHALICE head injury decision rules in children: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 389:2393–2402, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berdahl C, Schuur JD, Fisher NL, Burstin H, Pines JM: Policy Measures and Reimbursement for Emergency Medical Imaging in the Era of Payment Reform: Proceedings From a Panel Discussion of the 2015 Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference. Acad Emerg Med 22:1393–1399, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bowman SM, Bird TM, Aitken ME, Tilford JM: Trends in hospitalizations associated with pediatric traumatic brain injuries. Pediatrics 122:988–993, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bulsara KR, Gunel M, Amin-Hanjani S, Chen PR, Connolly ES, Friedlander RM: Results of a national cerebrovascular neurosurgery survey on the management of cerebral vasospasm/delayed cerebral ischemia. J Neurointerv Surg 7:408–411, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burns EC, Burns BS, Newgard CD, Laurie A, Rongwei F, Graif T, et al. : Pediatric Minor Traumatic Brain Injury with Intracranial Hemorrhage: Identifying Low Risk Patients Who May Not Benefit From ICU Admission. Pediatric Emergency Care In Press, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Injury Prevention & Control: Traumatic Brain Injury & Concussion, in, 2016

- 10.Chen C, Shi J, Stanley RM, Sribnick EA, Groner JI, Xiang H: U.S. Trends of ED Visits for Pediatric Traumatic Brain Injuries: Implications for Clinical Trials. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collins D: Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res 12:229–238, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dawson ECM CP; Frim D; Koogler T: Is repeat head computed tomography necessary in children admitted with mild head injury and normal neurological exam? Pediatr Neurosurg 48:221–224, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dunning J, Daly JP, Lomas JP, Lecky F, Batchelor J, Mackway-Jones K: Derivation of the children’s head injury algorithm for the prediction of important clinical events decision rule for head injury in children. Arch Dis Child 91:885–891, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL: Prevalence of Childhood Exposure to Violence, Crime, and Abuse: Results From the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatr 169:746–754, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finnerty NM, Rodriguez RM, Carpenter CR, Sun BC, Theyyunni N, Ohle R, et al. : Clinical Decision Rules for Diagnostic Imaging in the Emergency Department: A Research Agenda. Acad Emerg Med 22:1406–1416, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Givner AG J; O’Connor D; Kassarjian A; Lamorte WW; Moulton S: Reimaging in pediatric neurotrauma: factors associated with progression of intracranial injury. J Pediatr Surg 37:381–385, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg JK, Stoev IT, Park TS, Smyth MD, Leonard JR, Leonard JC, et al. : Management of children with mild traumatic brain injury and intracranial hemorrhage. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 76:1089–1095, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenberg JK, Yan Y, Carpenter CR, Lumba-Brown A, Keller MS, Pineda JA, et al. : Development and Internal Validation of a Clinical Risk Score for Treating Children With Mild Head Trauma and Intracranial Injury. JAMA Pediatr 171:342–349, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grol R, Grimshaw J: From best evidence to best practice: effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet 362:1225–1230, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groves RM: Nonresponse Rates and Nonresponse Bias in Household Surveys. The Public Opinion Quarterly 70:646–675, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hill EP, Stiles PJ, Reyes J, Nold RJ, Helmer SD, Haan JM: Repeat head imaging in blunt pediatric trauma patients: Is it necessary? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 82:896–900, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holmes JF, Borgialli DA, Nadel FM, Quayle KS, Schambam N, Cooper A, et al. : Do children with blunt head trauma and normal cranial computed tomography scan results require hospitalization for neurologic observation? Ann Emerg Med 58:315–322, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howe J, Fitzpatrick CM, Lakam DR, Gleisner A, Vane DW: Routine repeat brain computed tomography in all children with mild traumatic brain injury may result in unnecessary radiation exposure. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 76:292–295; discussion 295–296, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jobe JB, Mingay DJ: Cognitive laboratory approach to designing questionnaires for surveys of the elderly. Public Health Rep 105:518–524, 1990 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jobe JB, Mingay DJ: Cognitive research improves questionnaires. Am J Public Health 79:1053–1055, 1989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson TP, Wislar JS: Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. Jama 307:1805–1806, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanzaria HK, Booker-Vaughns J, Itakura K, Yadav K, Kane BG, Gayer C, et al. : Dissemination and Implementation of Shared Decision Making Into Clinical Practice: A Research Agenda. Acad Emerg Med 23:1368–1379, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kanzaria HK, Brook RH, Probst MA, Harris D, Berry SH, Hoffman JR: Emergency physician perceptions of shared decision-making. Acad Emerg Med 22:399–405, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelley K, Clark B, Brown V, Sitzia J: Good practice in the conduct and reporting of survey research. Int J Qual Health Care 15:261–266, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, Vavilala MS, Wang J, Temkin N, Jaffe KM, et al. : Incidence and descriptive epidemiologic features of traumatic brain injury in King County, Washington. Pediatrics 128:946–954, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraemer MR, Sandoval-Garcia C, Bragg T, Iskandar BJ: Shunt-dependent hydrocephalus: management style among members of the American Society of Pediatric Neurosurgeons. J Neurosurg Pediatr 20:216–224, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, Hoyle JD Jr., Atabaki SM, Holubkov R, et al. : Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study. Lancet 374:1160–1170, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannix R, Meehan WP, Monuteaux MC, Bachur RG: Computed tomography for minor head injury: variation and trends in major United States pediatric emergency departments. J Pediatr 160:136–139 e131, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mannix R, O’Brien MJ, Meehan WP, 3rd: The epidemiology of outpatient visits for minor head injury: 2005 to 2009. Neurosurgery 73:129–134; discussion 134, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marin JR, Weaver MD, Yealy DM, Mannix RC: Trends in visits for traumatic brain injury to emergency departments in the United States. Jama 311:1917–1919, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McDonnell WM, Carpenter P, Jacobsen K, Kadish HA: Relative productivity of nurse practitioner and resident physician care models in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care 31:101–106, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natale JE, Joseph JG, Rogers AJ, Mahajan P, Cooper A, Wisner DH, et al. : Cranial computed tomography use among children with minor blunt head trauma: association with race/ethnicity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 166:732–737, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osmond MH, Klassen TP, Wells GA, Correll R, Jarvis A, Joubert G, et al. : CATCH: a clinical decision rule for the use of computed tomography in children with minor head injury. CMAJ 182:341–348, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Patel SK, Gozal YM, Krueger BM, Bayley JC, Moody S, Andaluz N, et al. : Routine surveillance imaging following mild traumatic brain injury with intracranial hemorrhage may not be necessary. J Pediatr Surg, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pew Research Center: Assessing the Representativeness of Public Opinion Surveys, in Pew Research Center (ed). Washington, DC, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stanley RM, Hoyle JD Jr, Dayan PS, Atabaki S, Lee L Lillis K, et al. : Emergency department practice variation in computed tomography use for children with minor blunt head trauma. J Pediatr 165:1201–1206.e1202, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vance CW, Lee MO, Holmes JF, Sokolove PE, Palchak MJ, Morris BA, et al. : Variation in specialists’ reported hospitalization practices of children sustaining blunt head trauma. West J Emerg Med 14:29–36, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.