Abstract

In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) patients, contraction of the muscles of the tongue is needed to protect the upper airway from collapse. During wakefulness, norepinephrine directly excites motoneurons that innervate the tongue and other upper airway muscles but its excitatory effects decline during sleep, thus contributing to OSA. In addition to motoneurons, NE may regulate activity in premotor pathways but little is known about these upstream effects. To start filling this void, we injected a retrograde tracer (beta-subunit of cholera toxin-CTb; 5–10 nl, 1%) into the hypoglossal (XII) motor nucleus in 7 rats. We then used dual immunohistochemistry and brightfield microscopy to count dopamine beta-hydroxylase (DBH)-positive axon terminals closely apposed to CTb cells located in five anatomically distinct XII premotor regions. In different premotor groups, we found on the average 2.2–4.3 closely apposed DBH terminals per cell, with ~60% more terminals on XII premotor neurons located in the ventrolateral pontine parabrachial region and ventral medullary gigantocellular region than on XII premotor cells of the rostral or caudal intermediate medullary reticular regions. This difference suggests stronger control by norepinephrine of the interneurons that mediate complex behavioral effects than of those mediating reflexes or respiratory drive to XII motoneurons.

Keywords: motor control, pons, reticular formation, sleep apnea, swallowing, tongue

1. Introduction

The muscles of the upper airway have vital roles in alimentation, vocalization and breathing. Although these functions are primarily executed during wakefulness, in individuals suffering from the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSA), upper airway muscle activity is needed to maintain the upper airway open for adequate ventilation during sleep. To cope with their adverse anatomical predisposition, OSA patients develop an adaptive increase of their basal upper airway muscle tone but this adaptation is not fully effective during sleep, leading to upper airway obstructions that repeatedly disrupt sleep and cause episodic hypoxemia [Dempsey et al., 2010; White & Younes, 2012]. Such recurrent nocturnal disruptions of sleep and breathing have multiple adverse cardiovascular, metabolic, cognitive and affective consequences [Javaheri et al., 2017; Seicean et al., 2008; Shahar et al., 2001; Young et al., 2008]. OSA is a major health problem affecting 9–38% of adults, with the prevalence increasing with age and obesity [Senaratna et al., 2017].

Sleep-related apneas and hypopneas occur as a result of state-dependent changes in the neural control of the muscles that line up the walls of the upper airway, including the muscles of the tongue innervated by hypoglossal (XII) motoneurons [Kubin, 2016; McGinley et al., 2008; White and Younes, 2012]. There is currently a consensus that state-dependent changes in the release of only a handful of modulators play a key role in sleep-related obstructions of the upper airway. Two of these transmitters, norepinephrine (NE) and serotonin, mediate a direct, wakefulness-related activation of motoneurons that is progressively withdrawn during transitions into non-rapid eye movement (REM) and then REM stages of sleep [Chan et al., 2006; Fenik et al., 2005; Kubin, 2014; Kubin et al., 1994]. Additionally, acetylcholine, may actively suppress motoneuronal activity preferentially during REM sleep [Grace et al., 2013]. In studies in rodents that explored the effects of sleep on XII motoneuronal activity, NE released onto motoneurons has been identified as a particularly powerful wake-related activator (see Horner et al., 2014; Kubin, 2016 for reviews).

Neuroanatomical studies have delineated the major sources of brainstem afferents to the XII motor nucleus. Some premotor pathways have well-established sleep/wake-dependent activity patterns; among those are the premotor neurons that synthesize NE, serotonin and acetylcholine [Aldes et al., 1992; Funk et al., 2011; Li et al., 1993b; Manaker & Tischler, 1993; Rukhadze & Kubin, 2007a,b]. Other groups of premotor neurons control execution of specific movements of the tongue and often use amino acids, such as glutamate, gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) or glycine, as their transmitters [Boissard et al., 2002; Li et al., 1997; Ono et al., 1998a; Travers et al., 2005; Yokota et al., 2011]. While the state-dependent effects of NE, serotonin and acetylcholine on motoneurons have been well-characterized, these modulators target not only motor nuclei but are also released at many other brain locations. Therefore, amino acid-releasing premotor neurons with axonal projections to the XII nucleus, referred thereafter as XII PMNs, are probably also targeted by NE and other state-dependent modulators. However, such a putative state-dependent modulation occurring at premotor levels has received little attention and has not been investigated in a quantitative manner. To begin filling this void, we assessed the relative density of NE presynaptic terminals closely apposed to cells belonging to anatomically and functionally different groups of pontomedullary XII PMNs.

We focused on 5 previously described non-aminergic, non-cholinergic subsets of XII PMNs. Included in our study were XII premotor cells of the caudal and rostral intermediate regions of the medullary reticular formation (cIRt and rIRt, respectively); premotor neurons located in the ventromedial medullary region at the junction of the gigantocelluar ventral and lateral paragigantocellular reticular nuclei (collectively referred to here as the ventral gigantocellular region - GCv); premotor neurons of the pontine peritrigeminal region (PeriV); and premotor neurons of the pontine parabrachial and the adjacent Kolliker-Fuse regions (jointly referred to as ParaB) [Borke et al., 1983; Dobbins & Feldman, 1995; Fay & Norgren, 1997; Takada et al., 1984; Travers & Norgren, 1983; Travers & Rinaman, 2002; Yokota et al., 2011].

The groups of XII PMNs that we distinguished on anatomical grounds have different roles in the premotor control of tongue functions. For example, the cIRt cells are a major source of central inspiratory drive to XII motoneurons [Ono et al., 1994; Woch et al., 2000] and some may also mediate stereotypic activation of the tongue during swallowing [Travers & Jackson, 1992]. In contrast, the rIRt cells are especially important for mediation of reflex effects from airway mechanoreceptors [Chamberlin et al., 2007] and may coordinate licking [DiNardo & Travers, 1997]. The medullary GCv premotor neurons may contribute to shaping of the phasic activation of XII motoneurons during various oromotor behaviors in wakefulness and some are also activated during REM sleep [Weber et al., 2015] when tongue muscles exhibit intense twitching activity [Lu & Kubin, 2009]. Some GCv premotor cells are GABAergic, and thus inhibitory [Boissard et al., 2002; Stanek et al., 2014; Weber et al., 2015]. The pontine PeriV neurons aggregate along the perimeter of the trigeminal motor nucleus (Mo5) and send axons not only to the XII nucleus but also to the Mo5 and facial motor nuclei [Li et al., 1993a; Manaker et al., 1992a; Stanek et al., 2014]. As such, they are probably involved in coordination of activity in different orofacial muscles during various stereotyped oromotor behaviors (drinking, chewing, swallowing). The ParaB premotor neurons may have several different roles; some are glutamatergic and contribute to inspiratory activation of XII motoneurons similarly to the cIRt neurons [Chamberlin, 2004; Kuna & Remmers, 1999; Yokota et al., 2015]. Other ParaB XII PMNs send divergent axons to multiple orofacial motor nuclei, and thus may contribute to coordination of orofacial movements [Chamberlin & Saper, 1998; Hayakawa et al., 1999]. Additionally, these PMNs may transmit supraspinal effects [Diaz-Casares et al., 2012; Kaur et al., 2013; Martelli et al., 2013; Takeuchi et al., 1980; Yasui et al., 1985], and contribute to respiratory plasticity [Dutschmann & Dick, 2012].

The aims of our study were, first, to determine whether NE terminals form close contacts with cells belonging to anatomically different groups of XII PMNs, and second, to quantitatively assess the relative density of these terminals in different premotor groups. As such, ours is the first step towards uncovering the anatomical basis for potential contribution of NE to different premotor pathways that impinge on XII motoneurons. An abstract of this work has been published [Boyle et al., 2017].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Seven adult Long-Evans male and female rats used in this study were generated in-house by mating males purchased from Rat Resource & Research Center at the University of Missouri (Columbia, MO) and females from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). They were housed in our animal facility under a 12 h light (7:00–19:00)/12 h dark cycle and with standard rodent chow and water available ad lib. They were weaned on day 20–21 after birth and, once they were at least 90 day-old, they underwent a survival surgery during which a retrograde tracer was microinjected into the XII nucleus, followed by a one-week post-injection survival period. On day 7 after injection, the rats were deeply anesthetized and perfused. All experimental procedures followed the National Institutes of Health (USA) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023) and were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pennsylvania (protocol 803882).

2.2. Retrograde tracer injections

Injections of cholera toxin beta sub-unit (CTb; List Biological Laboratories, Campbell, CA) were used to retrogradely label premotor cells with axonal projections to the XII motor nucleus, as described previously [Rukhadze & Kubin, 2007a]. Rats were initially anesthetized with isoflurane (3–4%) followed by i.m. injection of ketamine (60 mg/kg) and xylazine (8 mg/kg) and then placed in a stereotaxic head holder. A midline incision was made in the skin, muscles and atlanto-occipital membrane overlying the caudal medulla, and a glass micropipette filled with the tracer was inserted. Based on the surface landmarks, the pipette was positioned at optimal coordinates to reach the center of the caudal half of the XII motor nucleus on one side, and 5–10 nl of 1% CTb was pressure-injected over 3–5 min period while the injected volume was monitored by observing the movement of the meniscus through a calibrated monocular microscope. After the injection, the incision site was rinsed with sterile saline, the muscles and skin were sutured in layers, and an antibiotic ointment was applied. Once normal eating, drinking and motor activity were resumed, the animal was returned to its housing facility.

2.3. Perfusions and histological procedures

One week after tracer injections, the animals were anesthetized with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg, i.p.), the thorax was opened and a transcardial perfusion was performed, first with 200–300 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then with 300–400 ml of fixative (4% paraformaldehyde). The brainstem was removed and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS for at least 3 days prior to being sectioned on a cryostat in the coronal plane. Five series of 30 μm thick sections were collected.

The sections were first washed with PBS and sodium borohydride, pre-incubated in 5% horse serum for 30 min and then incubate overnight at 4°C in anti-dopamine beta hydroxylase (DBH; a marker for noradrenergic and adrenergic neurons) antibody made in mouse (MAB 308, 1:2000; Millipore-Sigma, Burlington, MA) in PBS containing 0.2% triton and 5% horse serum. Subsequently, sections were washed and incubated for 2 h in biotinylated anti-mouse IgG antibody made in horse (BA2001, 1:250; Vector, Burlingame, CA). Biotin-marked sites were tagged with avidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) complex (ABC kit; Vector) and HRP was then visualized with diaminobenzidine (DAB) in the presence of Ni-ammonium sulfate and hydrogen peroxide (Rukhadze & Kubin, 2007a). Sections were then again pre-incubated in horse serum for 30 min followed by an overnight incubation in CTb antibody made in goat (#703, 1:20,000; List Biological Laboratories) in PBS with 0.2% triton and 5% horse serum followed by washes and incubation for 2 h in biotinylated anti-goat IgG antibody made in horse (BA9500, 1:200; Vector). In this reaction, biotin was visualized using the ABC kit but with Ni-ammonium sulfate omitted to obtain a brown staining of retrogradely labeled cell bodies of XII PMNs. At the end of labeling, brain sections were serially mounted, dehydrated and coverslipped.

2.4. DBH terminal counting and statistical analysis

In the first step of analysis, we reviewed each set of double-labeled pontomedullary sections under low magnification (10x objective) and selected 20 retrogradely labeled XII PMNs from each of the premotor regions of interest on the side ipsilateral to the tracer injection site. Cells located on the injected side were selected because prior data indicate that pontomedullary projections to the XII nucleus are bilateral with a moderate ipsilateral predominance [Manaker et al., 1992b; Stanek et al., 2014]. The cells selected for analysis were required to have the entire cell body, including the cell nucleus, and at least one primary dendrite contained within the same section and not overlap with an adjacent labeled XII PMN. The 20 XII PMNs selected from each rat as representative of each premotor group were located in one brain section for each of the two IRt regions and in one or two sections separated by 150 μm for the remaining three regions of interest. The areas containing the selected cells were photographed and each cell was uniquely numbered from 1 to 20. The five premotor regions from which XII PMNs were selected were located within the following antero-posterior levels from bregma according to a rat brain atlas [Paxinos & Watson, 2007]: −14.3 mm to −14.1 mm for cIRt; −12.7 mm to −12.2 mm for rIRt and GCv; −9.7 mm to −9.4 mm for PeriV; and −9.1 mm to −8.8 mm for ParaB. Excluded from our analysis were the pontomedullary XII premotor cell groups with sleep-wake state-dependent pattern of activity, such as NE, serotonergic and cholinergic [Aldes et al., 1992; Jacobs & Azmitia, 1992; Manaker & Tischler, 1993; Rukhadze & Kubin, 2007a,b; Rukhadze et al., 2008], those located in the immediate vicinity of the XII nucleus (in the nucleus of Roller and in the cIRt part adjacent to the XII nucleus) because residual diffusion of the tracer from the injection site made reliable recognition of genuine retrograde labeling difficult [DiNardo & Travers, 1997; Sumino & Nakamura, 1974]. Also excluded were XII premotor cells in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) [Norgren, 1978; Fay & Norgren, 1997], and in the principal trigeminal sensory nucleus [Aldes & Boone, 1985] because our retrograde labeling from the caudal XII nucleus did not consistently yield retrograde labeling in these locations (cf. Dobbins & Feldman, 1995).

Following the premotor cell selection step, each numbered cell was examined at high magnification using a 100x water-immersion objective for the presence of black-stained axonal swellings representing DBH-labeled terminals closely apposed to the cell body or proximal dendrites. Close apposition were accepted as such when no space separating the terminal and the membrane of the labeled premotor cells could be discerned despite best efforts to find such a separation. We used an upright microscope (Leica DMLB, Wetzlar, Germany) and digital camera (ProgRes CFscan; Jenoptik, Jena, Germany) to observe and photograph all images of interest.

One person (CEB) counted close appositions between DBH-labeled terminal boutons and all XII PMNs selected for analysis, and two other persons (AB and LK) independently conducted secondary recounting of closely apposed NE terminal in 3 of the 7 animals. Since the three compared cell-by-cell sets of counts differed only randomly and the means per animal and region revealed no statistically significant differences among the observers, the data derived from the primary counting was subjected to complete analysis and is described in this report. With 7 rats included in the study and 20 cells examined in each region of each animal, our findings are based on 140 cells selected from each of the 5 analyzed pontomedullary regions. The mean apposition counts per cell established for each premotor region in each animal represented the primary numeric outcome that was subjected to statistical analysis using one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the animals treated as a separate subjects and the premotor groups entered into the analysis as 5 different levels of the “group” factor. In the subsequent post hoc comparisons of terminal counts among the different premotor groups we used the Holm-Sidak correction for multiple comparisons (SigmaPlot v.12.5, Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA). With all data distributions meeting the Shapiro-Wilk normality test, the variability of the means is characterized by the standard errors (SE) throughout this report unless noted otherwise (Fig. 6).

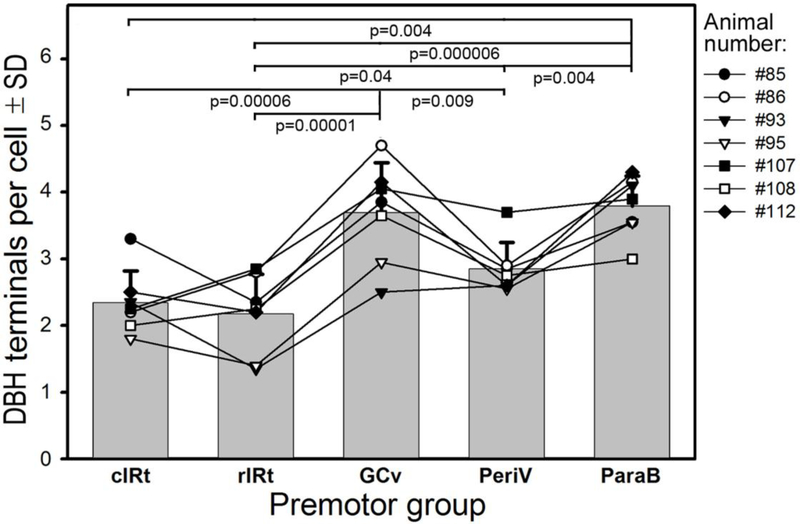

Figure 6:

Average numbers of closely apposed DBH-stained boutons on XII PMNs belonging to different premotor groups. Bars show the mean and standard deviation values for the 7 rats of the present study. The superimposed lines represent individual means obtained from 20 retrogradely labeled XII PMNs selected from each premotor group in individual rats; data from the same animal are marked by the same symbol and are connected by lines. The overall order of closely apposed terminal counts was: cIRt ≈ rIRt < PeriV < GCv ≈ ParaB, and the means for individual rats well approximated this order. Pairwise comparisons among the premotor groups conducted with correction for multiple comparisons revealed many highly significant differences.

3. Results

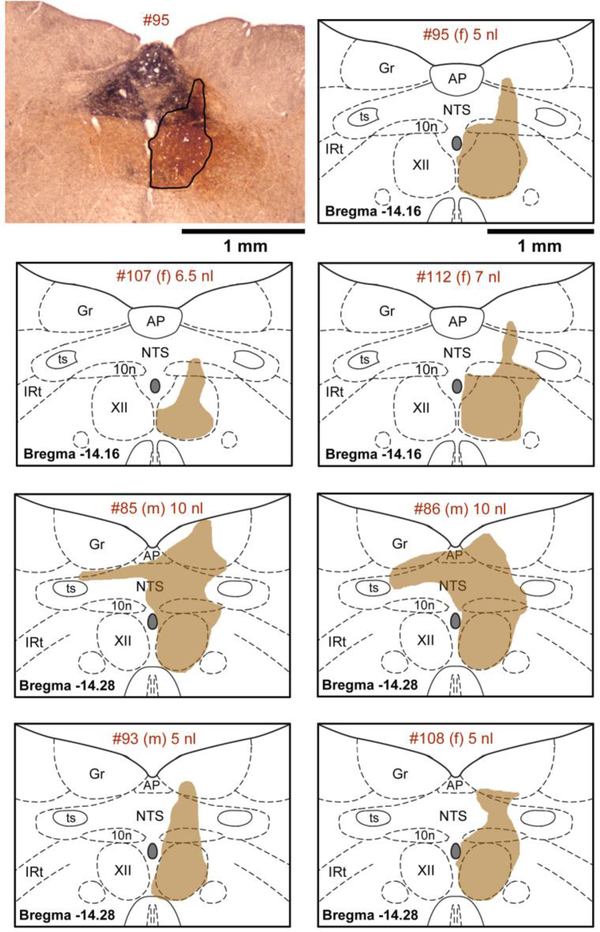

XII PMNs were clearly labeled with CTb injected unilaterally into the XII nucleus, as described in our earlier similar study [Rukhadze & Kubin, 2007a]. In all 7 rats, the centers of the tracer injection sites were found near the center of the XII nucleus, with very limited tracer spread ventral and lateral to the XII nucleus and into the XII nucleus of the opposite side (Fig. 1). In all animals, there was a degree of tracer spill dorsal to the XII nucleus that was related to a “leak” of CTb upward along the track of the injection pipette. The magnitude of this effect ranged from minimal in Rat #107 to involving considerable portions of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and NTS (Rats #85 and #86) (Fig. 1). This variability was, at least in part, related to the volume of the injection that ranged in individual cases from 5 to 10 nl (Fig. 1) but it ultimately did not translate into any systematic relationship to the counts of NE terminals closely apposed to retrogradely labeled neurons found in different animals (see Fig. 6 for the means for each animal and premotor region superimposed onto the average data across all animals). Similarly, there was no obvious relationship between the terminal apposition counts and the sex of the animals (4 female and 3 male rats, as indicated in Figs. 1 and 6).

Figure 1:

Location of the tracer injection sites. The upper left panel shows a microphotograph of staining (outlined) following unilateral tracer injection into the center of the right Xii nucleus (5 nl of 1 % beta subunit of cholera toxin - CTb). The tracer covers the entire XII nucleus on one side with limited diffusion ventral and lateral to the nucleus and a moderate spill into the dorsal nucleus of the vagus (10n) and nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS). The dense black dopamine beta hydroxylase (DBH) staining marks the characteristic aggregation of noradrenergic and adrenergic cells and fibers dorsal to the XII nucleus. The top panel on the right shows CTb spread in the same rat (#95) redrawn and superimposed onto the closest standard medullary cross-sections derived from a rat brain atlas [Paxinos & Watson, 2007]. The six panels below the top row show in the same format CTb distribution in the remaining 6 rats of this study. The identifying number for each rat, its sex (female (f) or male (m)) and the volume of tracer injected are specified at the top of each panel. Abbreviations: AP – area postrema; Gr – gracile nucleus; IRt – intermediate medullary reticular region; ts – solitary tract.

In the preliminary counting of DBH terminals closely apposed to XII PMNs, we distinguished between close appositions located on the cell bodies versus those on the proximal dendrites of the target cell. However, the somatic and dendritic counts did not exhibit distinct patterns among the different premotor groups. Also, among the 20 premotor cells selected for analysis within each premotor region, there were usually a few in which no close appositions were identified. There was, however, no correlation between the proportions of cells in which we found no closely apposed terminals and the premotor group. The absence of such correlation excluded the possibility that the mean terminal counts per cell were reflective of the different proportions of cells with no closely apposed terminals in different premotor groups. Based on these initial analyses, the somatic and dendritic counts were combined, and all PMNs with no closely apposed terminals were included as containing 0 (zero) terminals. Accordingly, reported below are the total mean terminal counts per cell first calculated for all premotor cells selected for analysis within each premotor group in each animal and then averaged within each premotor group across all animals.

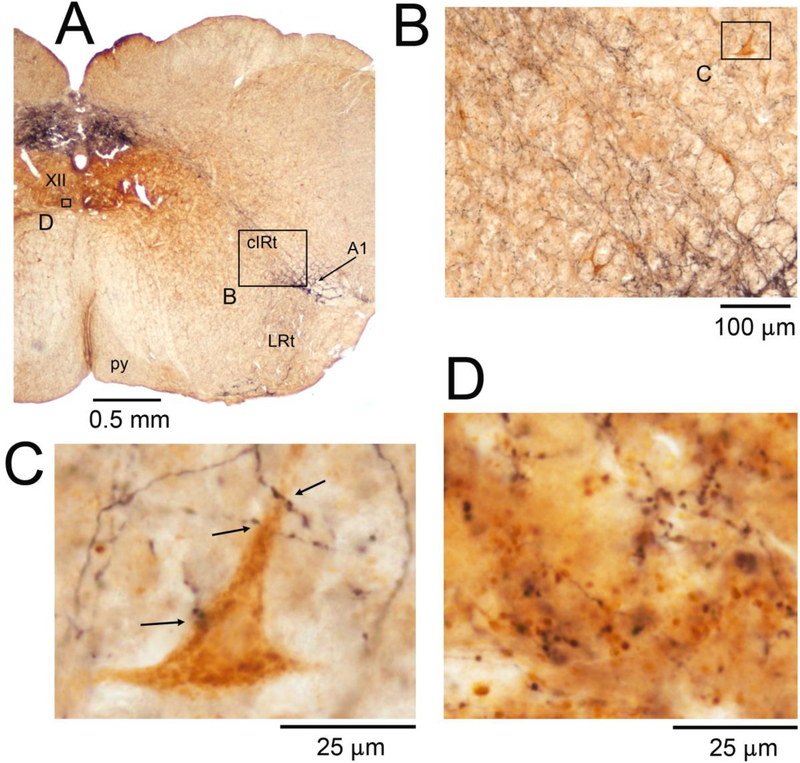

The retrogradely labeled XII PMNs representing the 5 different premotor cell groups were distributed with patterns that have been extensively characterized in earlier retrograde tracing studies (see Introduction). Figure 2 shows an example of retrogradely labeled XII PMNs located in the medullary cIRt region and the associated DBH-labeled terminals. It is of note that the gross density of DBH-labeled axonal swellings was considerably lower in the cIRT region than in the ventromedial region of the XII nucleus proper where DBH terminal density is very prominent (cf., panels C and D in Fig. 2; see also Rukhadze et al., 2010). Across all 7 animals, the mean number of DBH-labeled terminals closely apposed to cIRt PMNs was 2.3 ±0.2 per cell (Fig. 6).

Figure 2:

DBH terminals on and near retrogradely labeled cIRt XII PMNs and, for comparison, DBH terminals in the ventromedial region of the XII motor nucleus. A: low magnification image of the brain section containing the cIRt region. Arrow points to a cluster of DBH-stained cells representing NE neurons of the A1 group. Other abbreviations for local anatomical landmarks: LRt – lateral reticular nucleus, py – pyramidal tract. Boxes mark the locations of the enlarged details shown in panels B-D. B: the cIRt region ipsilateral to the tracer injection site shown at an intermediate magnification suitable for visualization of labeled XII PMNs (brown). C: one of the labeled XII PMNs of panel B illustrated at the high magnification used to identify DBH-stained terminals closely apposed to the cell bodies and proximal dendrites of retrogradely labeled XII PMNs; arrows show the sites identified as putative points of close appositions. D: DBH terminals in the ventromedial region of the XII nucleus. DBH fibers and terminals are shown in black; the brown background represents residual diffusion of the retrograde tracer into the side opposite to the injection (see the small box in the left XII nucleus in A). Comparison of panels C and D, both shown at the same magnification, illustrates that DBH terminal density is much higher in the ventromedial XII nucleus than in the cIRt region.

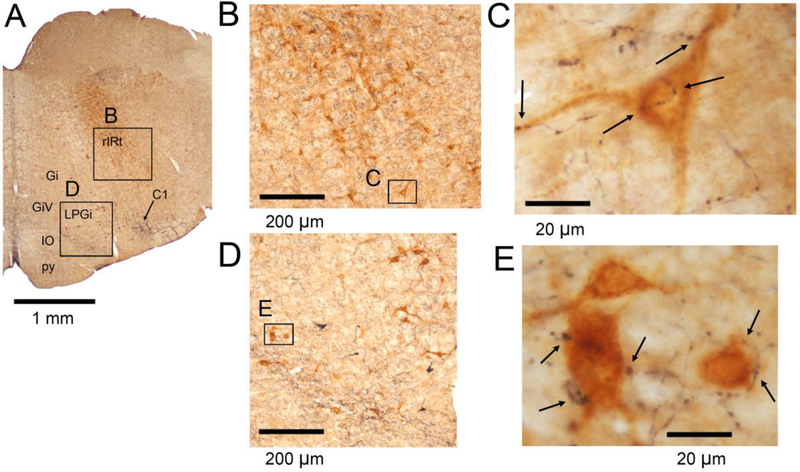

Figure 3 shows low- and high-magnification examples of XII PMNs located in the rIRt (panels B and C), and GCv (panels D and E), regions. The average number of closely apposed teminals found on rIRt PMNs was 2.2 ±0.2 per cell, hence similar to cIRt. The density of DBH terminals associated with GCv PMNs was notably higher, 3.7 ±0.3 per cell (p=0.0000l vs. rIRt by pairwise comparison with Holm-Sidak correction) (Fig. 6).

Figure 3:

DBH terminals in the rIRt and GCvXII premotor regions. A: low magnification image of the brain section from which the specific examples were derived. Arrow points to a cluster of DBH-stained cells which at this level mainly represent adrenergic neurons of the C1 group. Other abbreviations for local anatomical landmarks: Gi – gigantocellular reticular nucleus, GiV – ventral gigantocellular reticular nucleus, IO – inferior olive, LPGi – lateral paragigantocellular nucleus, py – pyramidal tract. B and C: rIRt XII PMNs (brown) shown at increasing magnifications. The image in C was obtained at the magnification used to identify DBH-stained terminals closely apposed to cell bodies and proximal dendrites of identified XII PMNs; arrows point to such a putative synaptic contacts. D and E: GCv XII PMNs shown at increasing magnifications using the same format as in B and C.

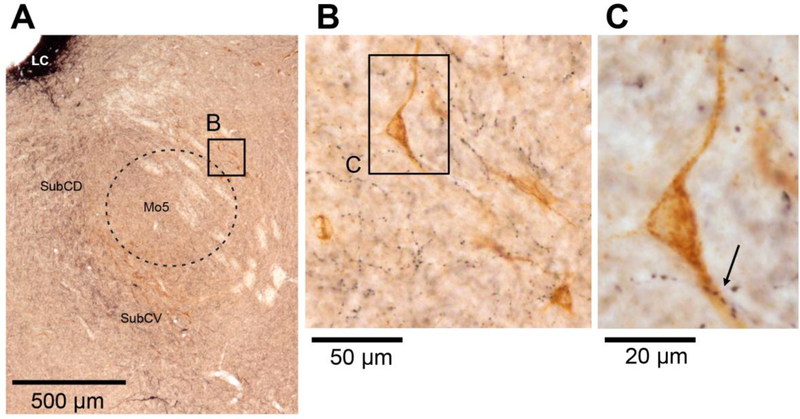

The PeriV XII PMNs characteristically surround the Mo5 nucleus (Fig. 4A – dashed line). The mean number of DBH terminals closely apposed to these XII PMNs was 2.9 ±0.15 per cell (Fig. 6). In Fig. 4B, one can note that the overall density of DBH terminal boutons located in the close vicinity of the labeled PeriV PMNs is similar or lower than that within the body of the Mo5, a part of which is included in the lower left corner of Fig. 4B. This is similar to the relatively lower DBH terminal density in the cIRt region when compared to the XII motor nucleus (cf. Figs. 2C and D).

Figure 4:

DBH terminals on PeriV XII PMNs. A: PeriV XII PMNs are characteristically distributed along the perimeter of the trigeminal motor nucleus (Mo5 – dashed line). The black-stained area in the upper left corner represents the locus coeruleus (LC). Other abbreviations for local anatomical landmarks: SubCD – dorsal part of the subcoeruleus region, SubCV – ventral part of the subcoeruleus region. B and C: selected PeriV XII PMNs (brown) shown at progressively higher magnification. The relatively dense black-stained axonal swellings seen in the lower left portion of panel B represent DBH-stained fibers and terminals located within the Mo5 proper. Arrow in C shows a site of multiple close appositions between a dendrite of a retrogradely labeled PeriV XII premotor neuron and DBH-stained boutons.

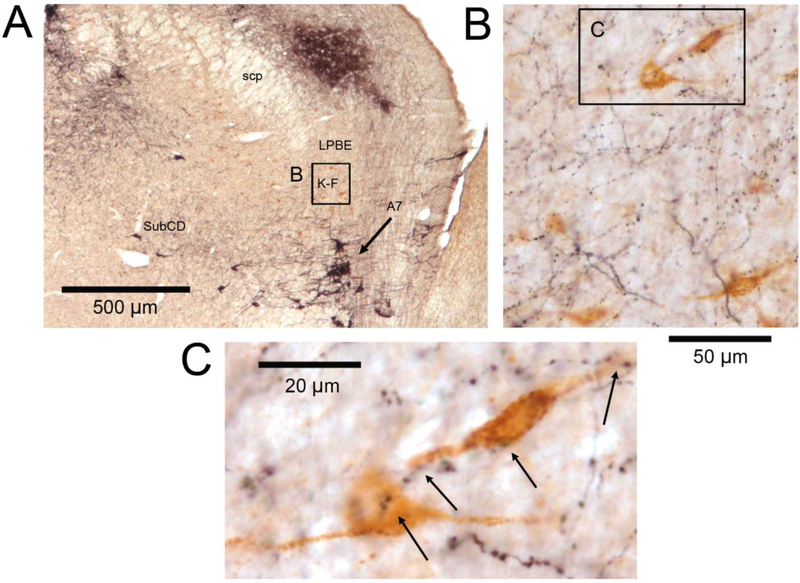

The ParaB XII PMNs are the most rostral XII premotor group included in our study. At this pontine level, one also finds prominent groups of NE cells and their dendrites (Fig. 5A). While these elements dominate the image at gross examination, one can also note the characteristic en passant appearance of local DBH-stained terminal boutons (Fig. 5C). The mean number of DBH terminals closely apposed to ParaB PMNs was 3.8 ±0.2 per cell (Fig. 6).

Figure 5:

DBH terminals on ParaB XII PMNs. A: low-magnification image of the section through the dorsolateral pons. DBH-staining (black) marks a plexus of fibers in the dorsolateral parabrachial region and a dense cluster of cells belonging to the pontine A7 group (arrow). Visible are also scattered DBH-positive cells of the dorsal subcoeruleus region (SubCD). Other abbreviations for local anatomical landmarks: K-F – Kölliker-Fuse nucleus, LPBE – external portion of the lateral parabrachial region, scp – superior cerebellar peduncle. The box marked B and the corresponding panel B contain numerous XII PMNs retrogradely labeled with CTb (brown). C: enlarged image of a pair of XII PMNs of the K-F nucleus enclosed in the box in B. Arrows point to DBH-stained axonal swellings closely apposed to cell bodies and proximal dendrites of these two XII PMNs.

Overall, XII PMNs belonging to different premotor groups had different numbers of DBH terminals closely apposing their cell bodies and/or proximal dendrites (Fig. 6). Based on the analysis of the mean numbers of close appositions in different premotor regions conducted using one-way repeated measures ANOVA, there was a highly significant effect of the premotor group (F6, 34=19.4; p=3•10−7), whereas the effects of the subject (animal) was not significant. The latter is important to note as it indicates that the variable extent of tracer diffusion from the injection sites in different animals (cf. Fig. 1) did not affect the outcomes from the analysis. Figure 6 presents the average data for all 5 XII premotor groups and lists all significant differences identified following correction for multiple comparisons. The mean counts obtained from individual animals (line graphs in Fig. 6) closely followed the mean pattern of closely apposed terminal densities obtained for all 7 rats of this study (bars). The ParaB and GCv premotor groups had the highest counts of NE terminal contacts, 3.8 ±0.2 and 3.7 ±0.3 per cell, respectively. In contrast, rIRt and cIRt had the lowest counts, 2.2 ±0.2 and 2.3 ±0.2 per cell.

4. Discussion

We uncovered significant differences in the numbers of DBH-stained terminals closely apposed to XII PMNs among 5 anatomically and functionally different XII premotor groups. ParaB and GCv PMNs had about 60% higher numbers of such terminals than XII PMNs of the medullary rostral and caudal IRt regions, whereas terminal counts on PeriV PMNs were intermediate between the other groups. This leads us to conclude that the strength of the control exerted by NE varies among different premotor pathways that converge on XII motoneurons.

4.1. Differential NE innervation of XII PMNs

We quantified DBH terminals closely apposing retrogradely labeled XII PMNs. For the lower brainstem, DBH-labeling mainly marks NE-containing terminals based on the distribution patterns of adrenergic, NE and dopaminergic fibers (cf., Kalia et al., 1985). The numbers of closely apposed terminals that we counted per cell may appear to be small but, as discussed in the next section, these numbers likely underestimate NE input to XII PMNs. What is important is that the anatomical density of these terminals, however underestimated, varied systematically and significantly among the different premotor groups. The magnitude of the difference was over 60% (3.8 vs. 2.2 terminals per cell) which may be large enough to translate into different strengths of NE effects exerted on different groups of XII PMNs.

Our quantification of closely apposed NE terminals on XII PMNs allows us to compare these counts to our prior quantification of NE terminals closely apposed to XII motoneurons [Rukhadze et al., 2010]. The comparison is valid because both studies used the same methodology. Thus, while our present counts for XII PMNs ranged from 2.2 to 3.8 per cell, the median count of NE terminals closely apposed to XII motoneurons located in the ventromedial quadrant of the XII nucleus was 18 per motoneuron (25–75% interquartile range: 12–25). This difference in favor of XII motoneurons is consistent with visually compared density of DBH terminal boutons in the XII nucleus to the pontomedullary regions containing XII PMNs (cf. Figs. 2C and D). Such a large difference in NE terminal density in favor of the XII nucleus suggests that the strength of NE effects exerted directly on XII motoneurons is much higher than that exerted on XII PMNs.

The anatomical criteria that we used in the present study to categorize different groups of XII PMNs represent only the first level of classification. There is now considerable evidence that the PMNs representing the 5 premotor group that we distinguished can be further subdivided based on the neurochemistry of their prevailing neurotransmitters. So, within the IRt premotor pool, most cells are glutamatergic but about 20% are cholinergic or GABAergic [Li et al., 1997; Travers et al., 2005; Volgin et al., 2008]. Furthermore, the pool of cIRt neurons with axonal projections to the XII nucleus is relatively enriched with those expressing mRNA for type M2 muscarinic cholinergic receptors (when compared to IRt neurons that do not send axons to the XII nucleus [Volgin et al., 2008]) and with those expressing the DBX1 transcription factor [Revill et al., 2015]. Compared to IRt neurons, less is known about neurochemical diversity of GCv, ParaB and PeriV XII PMNs; a major proportion of those in GCv may be GABAergic [Boissard et al., 2002; Weber et al., 2015], and those located in ParaB may comprise several neurochemical subtypes [Diaz-Casares et al., 2012; Geerling et al., 2017; Li et al., 1997]. It is not clear how these different neurochemical markers correlate with the functions of distinct subtypes of XII PMNs. Further elucidation of this issue would be one of the goals for future research.

In addition to the neurotransmitter diversity within and between different groups of XII PMNs, these premotor groups most likely receive neurochemically and functionally different afferent inputs. Although the anatomic origins of the afferent pathways to some of the XII premotor regions included in our study have been described (e.g., Fort et al., 1994; Vanderhorst & Ulfhake, 2006]), specific studies exploring afferents to identified XII PMNs present in these locations have not been conducted. Thus, important intricacies concerned with the neurochemistry and functions of XII premotor pathways remain to be resolved.

At present, our quantification of NE terminals closely apposed to XII PMNs suggests that NE has a particularly strong effect on ParaB and GCv PMNs and relatively lesser effect on IRt XII PMNs. There are, however, additional important factors that determine the relative influence of each premotor group on motoneurons. Those include: (i) the density of axonal ramifications of premotor terminals within the XII motor nucleus; (ii) somatic or dendritic location of their synaptic contacts on motoneurons; (iii) amount of transmitter released at each synapse per action potential; and (iv) the level of activity generated in different premotor pathways. All these factors would need to be determined to arrive to a comprehensive measure of the influence of each premotor group on XII motoneurons.

4.2. Limitations of our study

Translation of our anatomical findings into their functional relevance is limited by several features of the NE system that were beyond the scope of our present study. First, our quantification was limited to closely apposed NE terminals. However, NE is released both at the sites of putative synaptic contacts and into the extracellular space at a distance from its synaptic targets. In the latter case, NE acts through what is called “volume transmission” [Agnati et al., 1995]. We focused on terminals closely apposed to the cell bodies and proximal dendrites, as retrograde labeling of distal dendrites is less sharp than that of the cell bodies and proximal dendrites and because many labeled dendrites, or portions thereof, would be located in tissue sections other than the ones containing the examined cell bodies. Despite our underestimation of the total numbers of NE terminals that may influence activity of individual XII PMNs, the significant differences in the counts of closely apposed terminals among the premotor groups that we uncovered provide a valid, albeit only a relative, comparison of NE innervation among these groups. By the same token, it may seem that our sample of 20 cells per premotor region and animal was a small fraction of the total numbers of retrogradely labeled cells (in rats, there are hundreds of PMNs in each group [Dobbins & Feldman, 1995; Fay & Norgren, 1997; Stanek et al., 2014; Travers & Norgren, 1983; Travers & Rinaman, 2002; Volgin et al., 2008]). However, the consistency of our findings for different premotor groups across all rats (Fig. 6) indicates that the sample size that we selected was satisfactorily representative of each group.

Second, to fully understand how NE and its state-dependent release may affects XII PMNs one needs to know the type of NE receptors expressed in different types of XII PMNs. NE may have both excitatory and inhibitory effects, and they can be mediated by three major subtypes of adrenergic receptors (α1, α2 and β), with each subtype having additional molecular variants [Docherty, 1998]. To date, one in vitro pharmacological study in slices from juvenile rats revealed that medullary reticular XII PMNs may have both excitatory and inhibitory adrenergic receptors [Nasse & Travers, 2014], and in vivo iontophoretic studies of respiratory-modulated IRt neurons also supported dual excitatory-inhibitory adrenergic effects [Champagnat et al., 1979]. With NE release being state-dependent, excitability of XII PMNs can be either increased or decreased by NE in a state-dependent manner depending on the prevailing set of their adrenergic receptors. However, in the absence of specific information about the receptor subtypes in different groups of XII PMNs, one can only speculate as to which receptors might predominate based on the known effects of behavioral states on XII PMNs of different types.

We did not consider which groups of NE cells innervate different groups of XII PMNs. While the majority of NE in the brain originate from the locus coeruleus, NE cells of the subcoeruleus, A5 and A7 noradrenergic regions have the highest levels of projections to the XII motor nucleus whereas the projections from the locus coeruleus to the XII motoneurons are negligible [Rukhadze & Kubin, 2007a]. Further research is needed to determine if XII PMNs follow this same pattern of NE innervation.

It is also of note that we have not examined XII PMNs located in the immediate vicinity of the XII nucleus due to potential confounding effects of brown staining caused by diffusion of tracer residues from the injection site. Some of the XII PMNs located immediately ventrolateral to the XII nucleus may be involved in swallowing and oral rejection behaviors [DiNardo & Travers 1997; Ono et al., 1998a,b]. NE innervation of these cells and its role will require a separate study.

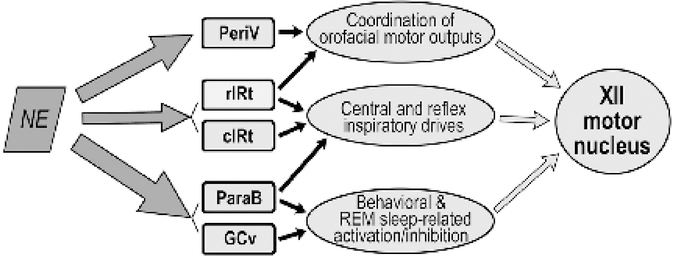

4.3. Functional implications

The differential strength of the control exerted by NE could result in complex effects on different groups of XII PMNs because these groups differ not only anatomically but also have different roles in oromotor control. Figure 7 puts our anatomical findings in the context of the hypothesized prevailing functions of different groups of XII PMNs, as determined by multiple functional studies of XII PMNs. We know that some of GCv premotor neurons are GABAergic and activated during both REM sleep and active oromotor behaviors [Boissard et al., 2002; Li et al., 1997; Weber et al., 2015]. Therefore, one may hypothesize that NE tonically inhibits these XII PMNs during wakefulness which would ensure that they are active only when they receive strong phasic excitatory inputs (e.g., to shape the pattern of specific oromotor behaviors). ParaB and PeriV XII PMNs also send projections to the Mo5 and facial motor nuclei and thus may coordinate functions of different orofacial muscles during chewing and swallowing [Travers & Rinaman, 2002]. Such a coordinated oromotor activity is suppressed during sleep, which suggests that excitability of these PMNs is facilitated by NE during wakefulness and this effects is reduced or abolished during sleep.

Figure 7:

Scheme of NE innervation of different groups of XII PMNs in relation to their prevailing functions in the control of XII motoneurons. Thickness of the arrows on the left side is proportional to the relative density of DBH-stained presynaptic boutons found in our study to be closely apposed to XII PMNs (cf. Fig. 6). We suggest that NE plays a particularly prominent role in the regulation of excitability in those XII PMNs that mediate behavioral effects related to sleep-wake states and various forebrain-originating commands during wakefulness (GCv and ParaB). In contrast, NE-dependent modulation of the premotor pathways that mediate central and reflex inspiratory drives is modest (rIRt and cIRt).

There is considerable evidence that many cIRt premotor neurons are excitatory (presumably glutamatergic) and mediate inspiratory drive to XII motoneurons [Ono et al., 1994; Woch et al., 2000]. In this regard, it is of note that inspiratory-modulated cells located in cIRt are little affected by changes is sleep-wake states [Orem et al., 2005; Woch et al., 2000]. Given that NE release drops precipitously during sleep, such a behavior of inspiratory modulated cIRt neurons is consistent with their activity being only under a weak control by NE. Our present data support this interpretation.

In our considerations, we have emphasized the sleep-wake state-dependent pattern of effects exerted by NE because there is a consistent decline of all NE cell activity during sleep [Aston-Jones & Bloom, 1981; Reiner, 1986; Rukhadze et al., 2008; Kubin, 2014]. However, the levels of NE cell activity and NE release also vary considerably within the state of wakefulness. For example, NE activation accompanies the states of increased attention elicited by novel and/or emotionally relevant stimuli [Aston-Jones et al., 1996]. Such a transient activation may serve to enhance the specific motor responses appropriate for given environmental conditions [Stafford & Jacobs, 1990]. This mode of NE action applies to both reflex responses and complex behaviors integrated in the forebrain. Of the XII premotor cell groups that we investigated, ParaB premotor neurons may be especially important because some of them mediate supraspinal commands [Diaz-Casares et al., 2012; Kaur et al., 2013; Martelli et al., 2013; Takeuchi et al., 1980; Yasui et al., 1985] and they have the highest numbers of closely apposed NE terminals of all XII premotor groups that we investigated.

5. Conclusions

We found that all major groups of XII PMNs have a potential to be modulated by NE whose release is state-dependent, high during wakefulness and absent during REM sleep. We also found that NE terminal density varies among the different XII premotor groups. Additional information about the prevailing types of adrenergic receptors on different categories of XII PMNs is needed to further evaluate the nature of NE effects. Nevertheless, the information gained from our study sets the framework for future experiments that will aim to unravel the neural control of orofacial motoneurons exerted by NE at the premotor levels. Such a knowledge may identify new targets for pharmacological treatments of motor disorders affecting oromotor behaviors, including those that cause sleep-disordered breathing.

Highlights.

Norepinephrine (NE) is a major wake-related excitatory modulator of motoneurons

NE also controls premotor pathways with as yet unknown patterns

We counted NE terminals closely apposed to hypoglossal premotor neurons

NE terminal counts differed among anatomically distinct premotor groups

NE differentially innervates premotor neurons related to different tongue functions

Acknowledgments

CEB thanks Ms. Kate Benincasa-Herr for introduction into immunohistochemistry and microscopic analysis. The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant HL-047600. The sponsor had no influence on the execution of the study or preparation of this report.

Abbreviations

- CTb

beta subunit of cholera toxin

- c/rIRt

caudal/rostral intermediate medullary reticular (region)

- DBH

dopamine beta-hydroxylase

- GCv

gigantocellular medullary reticular (region), ventral part

- K-F

Kölliker-Fuse

- Mo5

trigeminal motor nucleus

- NE

norepinephrine or noradrenergic

- NTS

nucleus of the solitary tract

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

- ParaB

parabrachial (used to designate the pontine ParaB and K-F regions combined)

- PeriV

peritrigeminal (region)

- REM

rapid eye movement

- XII

hypoglossal

- XII PMNs

hypoglossal premotor neurons

Footnotes

Declaration of conflict of interest: none.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Agnati LF, Zoli M, Stromberg I, & Fuxe K (1995). Intercellular communication in the brain: wiring versus volume transmission. Neuroscience 69, 711–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldes LD & Boone TB (1985). Organization of projections from the principal sensory trigeminal nucleus to the hypoglossal nucleus in the rat: an experimental light and electron microscopic study with axonal tracer techniques. Exp Brain Res 59, 16–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldes LD, Chapman ME, Chronister RB, & Haycock JW (1992). Sources of noradrenergic afferents to the hypoglossal nucleus in the rat. Brain Res Bull 29, 931–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G & Bloom FE (1981). Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J Neurosci 1, 876–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G, Rajkowski J, Kubiak P, Valentino RJ, & Shipley MT (1996). Role of the locus coeruleus in emotional activation. Progr Brain Res 107, 379–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissard R, Gervasoni D, Schmidt MH, Barbagli B, Fort P, & Luppi PH (2002). The rat pontomedullary network responsible for paradoxical sleep onset and maintenance: a combined microinjection and functional neuroanatomical study. Eur J Neurosci 16, 1959–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borke RC, Nau ME, & Ringler RL Jr (1983). Brain stem afferents of hypoglossal neurons in the rat. Brain Res 269, 47–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle C, Parkar A, & Kubin L. (2017). Noradrenergic termination patterns on pontomedullary hypoglossal premotor neurons Neuroscience Meeting Planner. Washington, DC: Soc. for Neurosci., Program; #240.15. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL (2004). Functional organization of the parabrachial complex and intertrigeminal region in the control of breathing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 143, 115–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL, Eikermann M, Fassbender P, White DP, & Malhotra A (2007). Genioglossus premotoneurons and the negative pressure reflex in rats. J Physiol (Lond) 579, 515–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin NL & Saper CB (1998). A brainstem network mediating apneic reflexes in the rat. J Neurosci 18, 6048–6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagnat J, Denavit-Saubié M, Henry JL, & Leviel V (1979). Catecholaminergic depressant effects on bulbar respiratory mechanisms. Brain Res 160, 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E, Steenland HW, Liu H, & Horner RL (2006). Endogenous excitatory drive modulating respiratory muscle activity across sleep-wake states. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 174, 1264–1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, & O’Donnell CP (2010). Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev 9o, 47–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Casares A, Lopez-Gonzalez MV, Peinado-Aragones CA, Gonzalez-Baron S, & Dawid-Milner MS (2012). Parabrachial complex glutamate receptors modulate the cardiorespiratory response evoked from hypothalamic defense area. Auton Neurosci 169, 124–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNardo LA & Travers JB (1997). Distribution of fos-like immunoreactivity in the medullary reticular formation of the rat after gustatory elicited ingestion and rejection behaviors. J Neurosci 17, 3826–3839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins EG & Feldman JL (1995). Differential innervation of protruder and retractor muscles of the tongue in rat. J Comp Neurol 357, 376–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty JR (1998). Subtypes of functional α1-and α2-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol 361, 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutschmann M & Dick TE (2012). Pontine mechanisms of respiratory control. Compr Physiol 2, 2443–2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fay RA & Norgren R (1997). Identification of rat brainstem multisynaptic connections to the oral motor nuclei using pseudorabies virus III. Lingual muscle motor systems. Brain Res Rev 25, 291–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenik VB, Davies RO, & Kubin L (2005). REM sleep-like atonia of hypoglossal (XII) motoneurons is caused by loss of noradrenergic and serotonergic inputs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172, 1322–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fort P, Luppi P-H, & Jouvet M (1994). Afferents to the nucleus reticularis parvicellularis of the cat medulla oblongata: a tract-tracing study with cholera toxin b subunit. J Comp Neurol 342, 603–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Funk GD, Zwicker JD, Selvaratnam R, & Robinson DM (2011). Noradrenergic modulation of hypoglossal motoneuron excitability: developmental and putative state-dependent mechanisms. Arch Ital Biol 149, 426–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerling JC, Yokota S, Rukhadze I, Roe D, & Chamberlin NL (2017). Kolliker-Fuse GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons project to distinct targets. J Comp Neurol 525, 1844–1860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grace KP, Hughes SW, & Horner RL (2013). Identification of the mechanism mediating genioglossus muscle suppression in REM sleep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 187, 311–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayakawa T, Zheng JQ, & Seki M (1999). Direct parabrachial nuclear projections to the pharyngeal motooneurons in the rat: an anterograde and retrograde double-labeling study. Brain Res 816, 364–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner RL, Hughes SW, & Malhotra A (2014). State-dependent and reflex drives to the upper airway: basic physiology with clinical implications. J Appl Physiol 116, 325–336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BL & Azmitia EC (1992). Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev 72, 165–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javaheri S, Barbe F, Campos-Rodriguez F, Dempsey JA, Khayat R, Javaheri S, Malhotra A, Martinez-Garcia MA, Mehra R, Pack AI, Polotsky VY, Redline S, & Somers VK (2017). Sleep apnea: types, mechanisms, and clinical cardiovascular consequences. J Amer Coll Cardiol 69, 841–858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalia M, Fuxe K, & Goldstein M (1985). Rat medulla oblongata. III. Adrenergic (C1 and C2) neurons, nerve fibers and presumptive terminal processes. J Comp Neurol 233, 333–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur S, Pedersen NP, Yokota S, Hur EE, Fuller PM, Lazarus M, Chamberlin NL, & Saper CB (2013). Glutamatergic signaling from the parabrachial nucleus plays a critical role in hypercapnic arousal. J Neurosci 33, 7627–7640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin L (2014). Sleep-wake control of the upper airway by noradrenergic neurons, with and without intermittent hypoxia. In The Central Nervous System Control of Respiration, eds. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holstege G, Beers CM, & Subramanian HH, Progr Brain Res 209: 255–274. (doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63274-6.00013-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin L (2016). Neural control of the upper airway: respiratory and state-dependent mechanisms. Compr Physiol 6, 1801–1850. (doi: 10.1002/cphy.c160002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin L, Reignier C, Tojima H, Taguchi O, Pack AI, & Davies RO (1994). Changes in serotonin level in the hypoglossal nucleus region during carbachol-induced atonia. Brain Res 645, 291–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuna ST & Remmers JE (1999). Premotor input to hypoglossal motoneurons from Kölliker-Fuse neurons in decerebrate cats. Respir Physiol 117, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li YQ, Takada M, & Mizuno N (1993a). Premotor neurons projecting simultaneously to two orofacial motor nuclei by sending their branched axons. A study with a fluorescent retrograde double-labeling technique in the rat. Neurosci Lett 152, 29–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-Q, Takada M, Kaneko T, & Mizuno M (1997). Distribution of GABAergic and glycinergic premotor neurons projecting to facial and hypoglossal nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol 378, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-Q, Takada M, & Mizuno N (1993b). The sites of origin of serotoninergic afferent fibers in the trigeminal motor, facial, and hypoglossal nuclei in the rat. Neurosci Res 17, 307–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu JW & Kubin L (2009). Electromyographic activity at the base and tip of the tongue across sleep-wake states in rats. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 167, 307–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manaker S & Tischler LJ (1993). Origin of serotonergic afferents to the hypoglossal nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 334, 466–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manaker S, Tischler LJ, Bigler TL, & Morrison AR (1992a). Neurons of the motor trigeminal nucleus project to the hypoglossal nucleus in the rat. Exp Brain Res 90, 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manaker S, Tischler LJ, & Morrison AR (1992b). Raphespinal and reticulospinal axon collaterals to the hypoglossal nucleus in the rat. J Comp Neurol 322, 68–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martelli D, Stanic D, & Dutschmann M (2013). The emerging role of the parabrachial complex in the generation of wakefulness drive and its implication for respiratory control. Respir Physiol Neurobiol 188, 318–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley BM, Schwartz AR, Schneider H, Kirkness JP, Smith PL, & Patil SP (2008). Upper airway neuromuscular compensation during sleep is defective in obstructive sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol 105, 197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasse JS & Travers JB (2014). Adrenoreceptor modulation of oromotor pathways in the rat medulla. J Neurophysiol 112, 580–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norgren R (1978). Projections from the nucleus of the solitary tract in the rat. Neuroscience 3, 207–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T, Ishiwata Y, Inaba N, Kuroda T, & Nakamura Y (1994). Hypoglossal premotor neurons with rhythmical inspiratory-related activity in the cat: localization and projection to the phrenic nucleus. Exp Brain Res 98, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T, Ishiwata Y, Inaba N, Kuroda T, & Nakamura Y (1998a). Modulation of the inspiratory-related activity of hypoglossal premotor neurons during ingestion and rejection in the decerebrate cat. J Neurophysiol 80, 48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T, Ishiwata Y, Kuroda T, & Nakamura Y (1998b). Swallowing-related perihypoglossal neurons projecting to hypoglossal motoneurons in the cat. J Dent Res 77, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orem JM, Lovering AT, & Vidruk EH (2005). Excitation of medullary respiratory neurons in REM sleep. Sleep 28, 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G & Watson C (2007). The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates, 6th Ed. Elsevier-Academic Press, Amsterdam. [Google Scholar]

- Reiner PB (1986). Correlational analysis of central noradrenergic neuronal activity and sympathetic tone in behaving cats. Brain Res 378, 86–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revill AL, Vann NC, Akins VT, Kottick A, Gray PA, Del Negro CA, & Funk GD (2015). Dbx1 precursor cells are a source of inspiratory XII premotoneurons. eLife 4, e12301. (doi: 10.7554/eLife.12301.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukhadze I, Fenik VB, Benincasa KE, Price A, & Kubin L (2010). Chronic intermittent hypoxia alters density of aminergic terminals and receptors in the hypoglossal motor nucleus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 182, 1321–1329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukhadze I, Fenik VB, Branconi JL, & Kubin L (2008). Fos expression in pontomedullary catecholaminergic cells following REM sleep-like episodes elicited by pontine carbachol in urethane-anesthetized rats. Neuroscience 152, 208–222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukhadze I & Kubin L (2007a). Differential pontomedullary catecholaminergic projections to hypoglossal motor nucleus and viscerosensory nucleus of the solitary tract. J Chem Neuroanat 33: 23–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rukhadze I & Kubin L (2007b). Mesopontine cholinergic projections to the hypoglossal motor nucleus. Neurosci Lett 413, 121–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seicean S, Kirchner HL, Gottlieb DJ, Punjabi NM, Resnick H, Sanders M, Budhiraja R, Singer M, & Redline S (2008). Sleep-disordered breathing and impaired glucose metabolism in normal-weight and overweight/obese individuals: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Diab Care 31, 1001–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaratna CV, Perret JL, Lodge CJ, Lowe AJ, Campbell BE, Matheson MC, Hamilton GS, & Dharmage SC (2017). Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev 34, 70–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahar E, Whitney CW, Redline S, Lee ET, Newman AB, Nieto FJ, O’Connor GT, Boland LL, Schwartz JE, & Samet JM (2001). Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiovascular disease: cross-sectional results of the Sleep Heart Health Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 163, 19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford IL & Jacobs BL (1990). Noradrenergic modulation of the masseteric reflex in behaving cats. II. Physiological studies. J Neurosci 10, 99–107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanek E, Cheng S, Takatoh J, Han BX, & Wang F (2014). Monosynaptic premotor circuit tracing reveals neural substrates for oro-motor coordination. eLife 3, e02511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumino R & Nakamura Y (1974). Synaptic potentials of hypoglossal motoneurons and a common inhibitory interneuron in the trigemino-hypoglossal reflex. Brain Res 73, 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada M, Itoh K, Yasui Y, Mitani A, Nomura S, & Mizuno N (1984). Distribution of premotor neurons for the hypoglossal nucleus in the cat. Neurosci Lett 52, 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y, Uemura M, Matsuda K, Matsushima R, & Mizuno N (1980). Parabrachial nucleus neurons projecting to the lower brain stem and the spinal cord. A study in the cat by the Fink-Heimer and the horseradish peroxidase methods. Exp Neurol 70, 403–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB & Jackson LM (1992). Hypoglossal neural activity during licking and swallowing in the awake rat. J Neurophysiol 67, 1171–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB & Norgren R (1983). Afferent projections to the oral motor nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol 220, 280–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB & Rinaman L (2002). Identification of lingual motor control circuits using two strains of pseudorabies virus. Neuroscience 115, 1139–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Travers JB, Yoo JE, Chandran R, Herman K, & Travers SP (2005). Neurotransmitter phenotypes of intermediate zone reticular formation projections to the motor trigeminal and hypoglossal nuclei in the rat. J Comp Neurol 488, 28–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VanderHorst VGJM & Ulfhake B (2006). The organization of the brainstem and spinal cord of the mouse: relationships between monoaminergic, cholinergic, and spinal projection systems. J Chem Neuroanat 31, 2–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volgin DV, Rukhadze I, & Kubin L (2008). Hypoglossal premotor neurons of the intermediate medullary reticular region express cholinergic markers. J Appl Physiol 105, 1576–1584. (doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90670.2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber F, Chung S, Beier KT, Xu M, Luo L, & Dan Y (2015). Control of REM sleep by ventral medulla GABAergic neurons. Nature 526, 435–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White DP & Younes MK (2012). Obstructive sleep apnea. Compr Physiol 2, 2541–2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woch G, Ogawa H, Davies RO, & Kubin L (2000). Behavior of hypoglossal inspiratory premotor neurons during the carbachol-induced, REM sleep-like suppression of upper airway motoneurons. Exp Brain Res 130, 508–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui Y, Itoh K, Takada M, Mitani A, Kaneko T, & Mizuno N (1985). Direct cortical projections to the parabrachial nucleus in the cat. J Comp Neurol 234, 77–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota S, Kaur S, Vanderhorst VG, Saper CB, & Chamberlin NL (2015). Respiratory-related outputs of glutamatergic, hypercapnia-responsive parabrachial neurons in mice. J Comp Neurol 523, 907–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokota S, Niu JG, Tsumori T, Oka T, & Yasui Y (2011). Glutamatergic Kolliker-Fuse nucleus neurons innervate hypoglossal motoneurons whose axons form the medial (protruder) branch of the hypoglossal nerve in the rat. Brain Res 1404, 10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T, Finn L, Peppard PE, Szklo-Coxe M, Austin D, Nieto FJ, Stubbs R, & Hla KM (2008). Sleep disordered breathing and mortality: eighteen-year follow-up of the Wisconsin sleep cohort. Sleep 31, 1071–1078. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]