Abstract

Background:

NSAID use is recommended to be avoided in kidney transplantation (KTX), with a paucity of studies assessing their safety within this population. This study aims to use a large cohort of Veterans Affairs (VA) KTX recipients to assess the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) with NSAID use.

Methods:

This is a ten-year longitudinal cohort study of adult kidney transplant recipients retrospectively followed in the VA system from 2001–10 that assessed for risk of AKI with NSAID prescriptions. NSAID prescriptions, patient characteristics and eGFRs were abstracted from the VA comprehensive electronic health record. NSAID exposure was assessed by duration, dosage and type. AKI events were defined by ≥50% decrease in eGFR. Risk was estimated using longitudinal multivariable generalized logistic regression model.

Results:

5,100 patients were included with a total of 29,980 years of follow up; 671 NSAID prescriptions in 273 (5.4%) patients (2.24 per 100 patient-years) with 472 (70%) high-dose were identified. High-dose NSAID prescriptions was associated with 2.83 (95% CI 1.55–5.19; p<0.001) higher odds of AKI events within a given year; low dose was not associated with AKI (OR 1.93 [0.95–6.02]; p=0.256). One 7-day NSAID course was associated with 5% higher odds of increasing AKI events, while chronic use (≥180 days) was associated with 3.25 (1.78–5.97; p<0.001) higher odds of AKI.

Conclusions:

Prescriptions for NSAIDs were uncommon in this cohort, but was associated with a significant increase in the risk of AKI, which was impacted by higher NSAID dose and longer NSAID durations.

1). Introduction

Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have the potential to impact outcomes in kidney transplant recipients through several mechanisms. Pharmacologically, NSAIDs inhibit the production of cyclooxygenase (COX), leading to prostaglandin inhibition, and reduced renal blood flow through vasoconstriction. NSAIDs may also lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalances and hypertension resulting in acute kidney injury (AKI) and impaired renal function.1–5 These nephrotoxic effects have also been observed in newer COX-2 selective agents due to expression of COX-2 within the renal parenchyma.6 Due to relatively low incidence rates, randomized trials rarely report renal dysfunction with NSAIDs, therefore observational trials provide most evidence of NSAIDs inducing acute renal dysfunction in both healthy and chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients.7,8

Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), which are the gold-standard immunosuppression for transplant patients and used in nearly all recipients and are known to cause both acute and chronic kidney injury. The acute nephrotoxicity due to the CNIs is through direct vasoconstriction of afferent arterioles in the kidneys, as well as an increase in vasoconstrictive factors and a reduction in vasodilators.9,10 The acute phase is thought to be reversible while chronic may be irreversible and is a major cause of concern in patients on immunosuppressive regimens containing CNIs. Thus, the combination of CNIs and NSAIDs have the strong potential of leading to significant adverse drug events due to this pharmacodynamic drug-drug interaction.11,12 Further, common comorbidities in transplant recipients, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hypertension, and peptic ulcer disease may predispose these patients to adverse events associated with NSAID prescriptions.13 Therefore, transplant clinicians, in general, recommend to avoid all NSAID prescriptions in kidney transplant recipients.

However, despite this universal recommendation, currently there is a lack of literature assessing the use of NSAIDs in kidney transplant recipients. There are no observational or randomized studies which assess clinical outcomes with use of these potentially nephrotoxic medications in the kidney transplant population. Thus, the aim of this study was to utilize a large, national comprehensive clinical dataset to assess the frequency and impact of NSAID prescriptions in contemporary kidney transplant recipients.

2). Materials and Methods:

2.1). Study Design and Patients:

This was a national retrospective longitudinal cohort study with the goal of assessing the outcomes associated with NSAID prescriptions in veteran kidney transplant patients. Patients were included in the study if they were identified as a kidney recipients transplanted between January 1, 2001 and December 31, 2007 with follow up through December 31, 2010 and received at least one prescription for an immunosuppressant (tacrolimus, cyclosporine, mycophenolate, azathioprine, sirolimus, or everolimus) during the study period. Non renal multi-organ transplant recipients (pancreas, liver, heart, lung, small intestine) and patients with less than one year of post transplant follow up were excluded from the study. Patients were stratified by NSAID prescriptions or non use during the study period. Prescriptions for combination products, intramuscular and oral NSAIDs were also included; outpatient prescriptions and those administered in the emergency department and or given in clinics were included. Topical NSAID products were excluded from the analysis. Baseline characteristics, prescription and laboratory data were extracted from the VA medical record system; Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) and Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture (VISTA). The VA healthcare system is a comprehensive healthcare model that patients often receive all healthcare through including primary care, emergency services and inpatient care, thus allowing for more complete record keeping in the patient’s medical record. Often, patients will receive all aspect of healthcare through the system including over the counter (OTC) medications prescribed by their physician due to zero cost co-pay that many veterans may have based on their service connected status. Thus, included in this analysis, are all NSAID products prescribed by VA providers, including those at OTC doses. This allows this present study to potentially capture a more comprehensive range of NSAID prescriptions, as compared to other national clinical datasets, since these may fail to capture a portion of NSAID prescriptions that is not typical prescribed by non-VA providers. Use of the VA healthcare system to quantify NSAID prescriptions in AKI has been previously described in the literature as well.14

2.2). Exposure Measures:

NSAID prescriptions was defined using a modified exposure measure based upon prior literature15,16 and incorporation of a proportion of days covered (PDC) to account for multiple exposures and to assess changes in NSAIDs dose and duration over time. Duration and dosage were stratified using the following methods:

Duration:

Patients were assigned a value from 0 to 1 based off their PDC, assessed in yearly increments and starting at the time of transplant. Thus, each patient would have up to 10 PDC measures (10 years of follow-up). A 7-day use would be captured as a PDC of 0.019 (7/365) while a 180-day course would equate to a PDC of 0.49 (180/365). PDC also accounted for nonconsecutive prescriptions, for example two 7-day prescriptions would account for PDC of 0.038 (14/365).

Dosage:

Total daily dosage (TDD) was defined based on the number of tablets supplied and instructions on NSAID prescription; patients were then categorized into two categories (High or Low) based upon TDD (see Table S1). High or Low categories were calculated for each year of follow up to assess for changes in exposure over time. The patient’s highest exposure level for each year was used if multiple NSAIDs were prescribed in the same time period.

Patients were also categorized by individual NSAID type and by NSAID class to assess for differences in outcomes across each category. Only aspirin products at dosages of ≥325 mg per day were included in the analysis as NSAIDs. Doses of aspirin below this were considered as solely antiplatelet therapies.

2.3). Outcomes Measures:

The primary endpoint of this study was to assess the impact of NSAID prescriptions on risk of developing AKI during the same calendar year the NSAID was prescribed. AKI was defined as a ≥ 50% acute decrease in estimated glomerular filtration rate (GFR) using the 4-variable MDRD equation.17 We chose to utilize the GFR rather than serum creatinine definition for AKI as it accounts for age, race and sex; we felt this to be a better assessment of AKI, as the ages of patients in this cohort did change over time. As this is an outpatient longitudinal analysis, we did not have access to urine output data and this was not included in our AKI definition. An acute decrease was defined as a change meeting threshold within 90-days of the previous serum creatinine measurement. The AKI events had to be at least 90-days apart to be defined as a new distinct event. Graft loss (censored for death), hospitalizations and all-cause mortality were also assessed and identified through electronic records and linking to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) registry. Reason for hospitalization was not able to be captured within the cohort data set. The secondary objective of the study was to define the frequency and duration of NSAID prescriptions in veteran kidney transplant patients. Measurements for this included frequency, dose, and duration of NSAID prescribed for each patient. NSAID prescriptions per 100 patient years was estimated for each individual NSAID within the study population.

2.4). Statistical Analysis

Standard descriptive and univariate statistics were utilized to describe the study population and NSAID utilization. This included proportions for categorical data, means±standard deviations (SD) for continuous normally distributed data and medians with interquartile ranges (IQR) for ordinal or non normal continuous data. These were compared using the chi square test, Student’s two-sided independent t-test and Mann Whitney U test, respectively. Descriptive statistics were used to calculate population baseline characteristics and frequency of NSAID prescriptions per 100 patient years. A multivariable longitudinal logistic regression model was used to estimate annualized risk comparing NSAID prescriptions to nonusers for the development of AKI using the generalized linear model (GLM) framework, accounting for the correlation of outcomes due to repeated patient measures. The model also accounts for the time varying nature of the NSAID prescriptions in a given patient and missingness that is not related with AKI. The model was adjusted for patient characteristics (age, race, sex, body mass index (BMI), PRA score, HLA mismatches), patient comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, coronary disease, peripheral vascular disease), donor/organ characteristics (age, living donor, extended criteria donors (ECD), donation after circulatory death (DCD), cold ischemia time (CIT)), delayed graft function, baseline medications (tacrolimus, mycophenolate, steroids). Graft loss and all-cause mortality were assessed using time to event analysis (Cox regression model) and Kaplan-Meier survival curves. All model assumptions for each model were tested using appropriate procedures. We also assessed for effect modification between salient covariates and NSAID prescriptions for the outcomes of graft loss and death using interaction terms, with none being significant (p>0,15). Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

3). Results:

In total, 5,100 patients were included in the cohort with 29,980 total years of follow up (275 (5.1%) were excluded due to lack of follow-up of at least one year). Median follow up was 5.7 years (IQR 4.1–7.6) per patient. Table 1 displays the baseline characteristics of the cohort. Patients who received NSAIDs were slightly younger and more likely to be African-American.

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of Cohort

| Baseline Characteristic | No NSAID Use (n=4,827) | NSAID Use (n=273) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Age (years±SD) | 58 ± 14 | 54 ±10 | <0.001 |

| Female | 2.3% | 2.2% | 0.879 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 61.9% | 48.0% | <0.001 |

| African-American | 29.3% | 41.8% | |

| Asian | 1.0% | 0.4% | |

| Hispanic | 6.8% | 8.4% | |

| Other | 1.0% | 1.5% | |

| Median BMI (kg/m2±SD) | 26.5 ± 10.6 | 26.7 ± 9.64 | 0.295 |

| History of Diabetes | 38.9% | 32.0% | 0.023 |

| History of Hypertension | 82.1% | 83.8% | 0.473 |

| History of CAD | 12.9% | 13.0% | 0.942 |

| History of PVD | 5.9% | 3.9% | 0.192 |

| History of CVA | 3.4% | 3.5% | 0.913 |

| Previous Transplant | 8.5% | 8.8% | 0.328 |

| Pre emptive Transplant | 21.8% | 14.3% | 0.003 |

| Median Current PRA (IQR) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.955 |

| PRA >20% | 5.3% | 9.3% | 0.007 |

| Median HLA Mismatches (IQR) | 4 (2, 5) | 4 (2, 5) | 0.693 |

| Median Cold Ischemic Time (IQR) | 14 (3, 21) | 14 (4, 22) | 0.136 |

| Mean Donor Age (years±SD) | 41 ± 14 | 37 ± 15 | <0.001 |

| Donor Female | 47.3% | 45.8% | 0.618 |

| Donor African-American | 13.4% | 21.2% | <0.001 |

| Living Donor | 34.2% | 34.8% | 0.835 |

| ECD | 14.6% | 10.3% | 0.482 |

| DCD | 4.7% | 3.3% | 0.288 |

| Cytolytic Induction | 35.4% | 35.9% | 0.873 |

| Tacrolimus | 72.7% | 70.0% | 0.325 |

| Mycophenolate | 87.2% | 85.7% | 0.489 |

| Steroids | 94.9% | 95.6% | 0.596 |

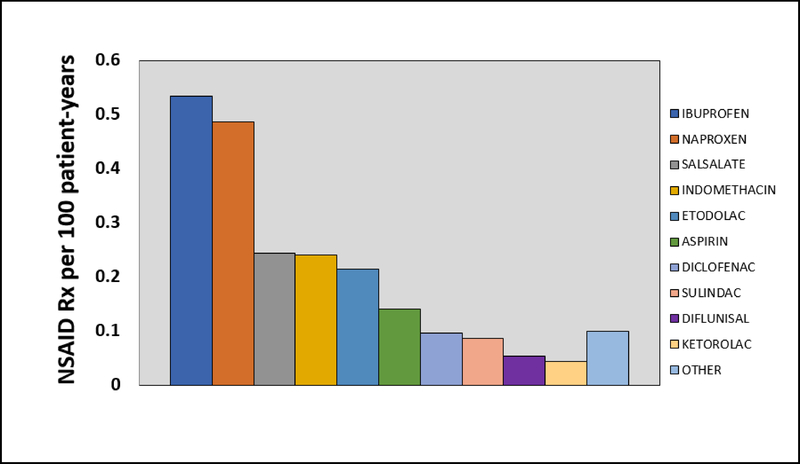

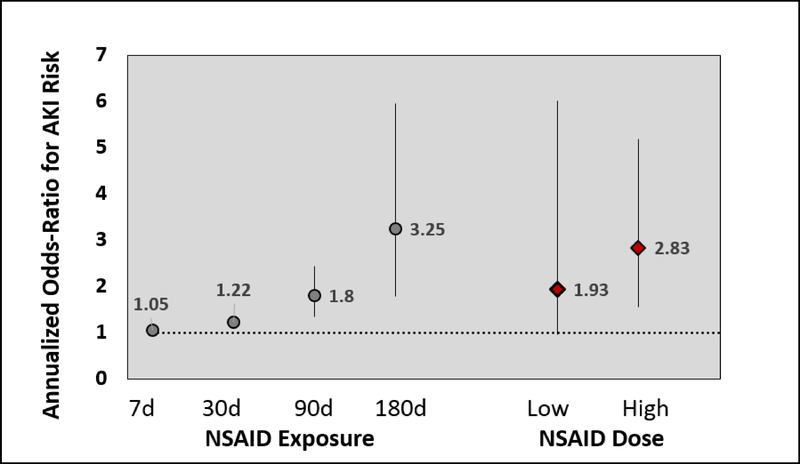

In total, 671 NSAID prescriptions were dispensed in 273 (5.4%) unique patients (2.24 per 100 patient-years), with 472 (70%) being categorized as high dose. Ibuprofen and naproxen were the most commonly prescribed NSAIDs. The median time from transplant to NSAID prescription was 4 years (IQR 2–5 years) with an average of 3.9±2.1 years. NSAID prescription frequency per 100 patient-years is displayed in Figure 1. High-dose NSAID prescriptions was associated with 2.83 (95% CI 1.55–5.19, p=0.0007) higher odds of increasing AKI events, while low-dose was not significantly associated with AKI events (odds ratio (OR) 1.93 [95% CI 0.95–6.02; p=0.2561, see Figure 2). Figure 2 also depicts how the increasing length of NSAID prescriptions was associated, in a duration-dependent manner, with higher odds of increasing AKI events, with 7 days (OR 1.05 [95% CI 1.02–1.08; p<0.001), 30 days (OR 1.22 [95% CI 1.10–1.35; p<0.001), 90 days (OR 1.80 [95% CI 1.33–2.44; p<0.001), and 180 days (OR 3.25 [95% CI 1.78–5.97; p<0.001) estimated to increase AKI risk, respectively. Risk of AKI events were similar across all NSAID types (OR 2.52 [95% CI 1.85–3.63; p<0.001), with the exception of sulindac (OR 1.2 [95% CI 0.17–8.65; p=0.856).

Figure 1:

“NSAID prescriptions per 100 patient-years” describes the number of NSAID prescriptions per 100 patient-years for individual NSAIDs included in the cohort. The y-axis displays the numerical value for prescriptions per 100 patient years and each series across the x-axis represents an individual NSAID defined in the legend to the right.

Figure 2:

“Annualized Odds Ratio for AKI Risk by NSAID Length of Exposure and Dosing” describes the annualized risk for acute kidney injury in the cohort stratified by exposure time and dose. The y-axis has the numerical annualized odds ratio for acute kidney injury risk, the horizontal dashed line represents an odds ratio of 1. The vertical lines are 95% confidence intervals. The NSAID exposure section of the x-axis displays time frames for which proportion of days covered was calculated and modeled to give specific odds ratios correlating to days of NSAID usage. The right side of the x-axis displays specific odds ratios relating to high and low dose. The low dose 95% confidence interval crosses 1.

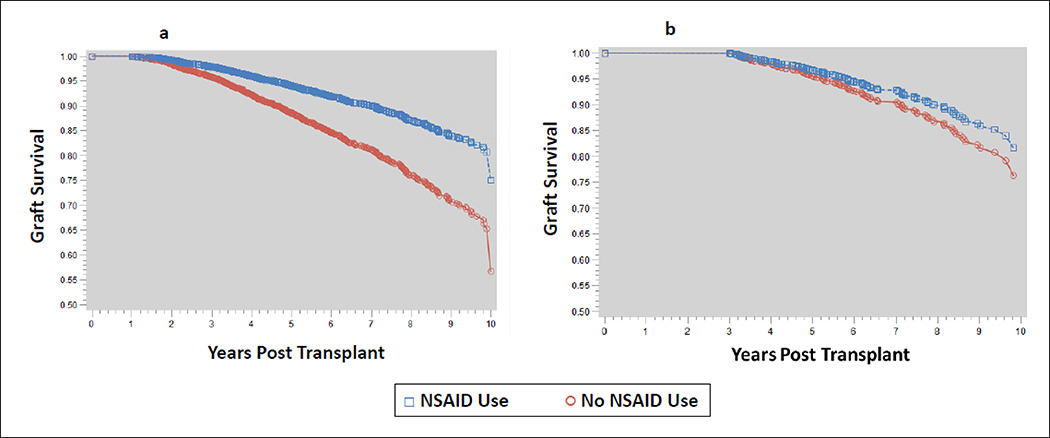

Post transplant clinical outcomes for the two cohorts are displayed in Table 2. Incidence of delayed graft function and acute rejection were similar between the two groups, but an increased incidence of hospitalizations were noted in the NSAID group (54.2% vs. 25.2%, p<0.001). Patients in the NSAID cohort had significantly improved graft survival rates compared to those who did not use NSAIDs. This may have been due to survival bias, as those with NSAID prescriptions received them later in transplant vintage (median of 4 years). As evidence of this, when a subset of patients was selected that had at least 3-years of graft survival, graft survival did not differ by NSAID prescriptions (Figure 3).

Table 2:

Summary of Clinical Outcomes of Patients in Cohort

| Outcomes | No NSAID prescriptions (n=4,827) | NSAID Use (n=273) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Delayed Graft Function | 16.7% | 18.3% | 0.498 |

| Acute Rejection | 15.7% | 15.4% | 0.881 |

| Hospitalization Incidence | 25.2% | 54.2% | <0.001 |

| Median Hospitalizations per 100 pt-years | 0 (0, 10) | 12 (0, 49) | <0.001 |

| Estimated Graft Survival |

<0.001 | ||

| 3-year | 95.7% | 97.7% | |

| 5-year | 88.5% | 94.0% | |

| 7-year | 81.3% | 90.0% | |

| Estimated Patient Survival |

0.070 | ||

| 3-year | 97.6% | 98.5% | |

| 5-year | 93.3% | 95.6% | |

| 7-year | 87.4% | 91.7% | |

Figure 3:

‘Graft Survival Model” describes the graft survival in the cohort. In both figures the y-axis displays the ratio of patients with graft survival and the x-axis displays years post transplantation. The blue squares in the figure represents patients with NSAID prescriptions, while the red circles represent patients who have not used NSAIDS in the cohort. Figure 3a is the full patient cohort, where Figure 3b is a censored population that only includes patients with graft survival ≥3 years to assess for bias in prescribing to stable patients further after transplantation.

4). Discussion:

The results of this longitudinal cohort study reveal a significant association between NSAID prescriptions and increased risk of AKI events post kidney transplantation in a cohort of adult veterans. Overall, use of prescription-based NSAID was low, but remained clinically significant in both patients receiving higher doses and longer durations of this therapy.

With 5% of the present study cohort receiving an NSAID prescription, although low, is expected given most providers were likely aware of post kidney transplant status in the contained VA health system. Even with the VA healthcare system’s enhanced ability to capture a larger portion of NSAID prescriptions than the general population, there are still likely more patients than potentially described in this cohort who take NSAIDs post transplant due to the prevalent OTC availability. The present study while low NSAID prescriptions was observed is difficult to compare to current literature which describes NSAID prescriptions in patients with reduced kidney function or CKD. One recent study that conducted a survey of just under 1,000 patients with chronic kidney disease (30% post kidney transplant) examined the use of NSAIDs. Specifically, in patients with CKD after kidney transplantation, 36% did not use NSAIDs and 64% reported at least occasional to daily use.18 The entire cohort revealed about 6.5% of patients used NSAIDs daily. This frequency is similar to a 2,000 patient cohort of US patients with CKD. Although the study did not specify whether any post transplant patients were included, it reported current use (defined as daily or nearly every day for the last 30 days) was approximately 5%, with around two-thirds of these patients reporting long term use (>1 year) at some point in the past.19 It is also important to note 3.5% of patients without CKD in this study reported current NSAID prescriptions. Another study, within the VA health system, examined NSAID prescriptions in over 70,000 patients with CKD, reported around 15% over use in this population, with decreasing use as GFR decreased.20 These studies highlight that there may be widespread and unrecognized long-term NSAID use in high-risk patient populations, such as CKD and kidney transplant recipients; it is important to note that our study only includes kidney transplant patients.

The overall incidence of AKI, regardless of NSAID prescriptions, is poorly defined, but has been demonstrated to impact clinical outcomes. In a study of over 28,000 Medicare kidney transplant recipients patients who experienced AKI, there was a significantly higher risk of transplant failure from any cause (HR 2.74), death with functioning transplant (2.36) and death-censored transplant loss (3.17), compared to those who did not have AKI.21 Interestingly, in our study, while there was an increased incidence of AKI and hospitalizations in patients taking NSAIDs, there was not a decrease in graft survival or all-cause mortality. This may potentially suggest that NSAID associated AKI may be less severe than other types of AKI that could be seen in the kidney transplant population. Estimated graft survival was significantly higher in the NSAID population, but when the cohort was sub-selected to include only those with at least three-years of graft survival, no differences were seen in patient outcomes by NSAID prescriptions. This likely demonstrates a survivor prescribing bias, in that those patients given NSAIDs by providers tended to receive them later post transplant, with advanced transplant vintage (median of 4 years between time of transplant and NSAID prescription). The lack of effect modification with all baseline and follow-up covariates in the model also leans towards this being driven primarily through prescriber bias. Clearly, further studies are warranted to assess the impact of NSAID prescriptions on patient and graft outcomes.

Individual NSAIDs and NSAID class may also be associated with variable degrees of renal toxicity based on pharmacological profiles, with those with longer half-lives (i.e. oxicams and ketorolac) potentially exhibiting a greater risk profile.1,22 While originally thought to have reduced renal effects due to its unique mechanism and decreased inhibition of renal prostaglandins,5,23,24 larger studies have yet to demonstrate a significant difference in sulindac versus other NSAIDs, currently reporting similar rates of events compared to other NSAIDs.25,26 In our study, risk of AKI was similar across all individual NSAIDs, with the exception of sulindac. While the number of patients receiving sulindac was relatively low, all other NSAIDs were individually associated with an increased risk of AKI with similarly low prescription numbers. Given the lack of literature assessing specifics of risk of AKI in individual NSAIDs, and the conflicting clinical results with patient’s taking sulindac, the potential renal sparing effects of sulindac warrants further research within the kidney transplant population.

Further examining the individual NSADs and associated risk of AKI, there have been mainly case studies describing AKI with both nonselective NSAIDs and newer COX-2 selective agents in this population. One case report describes an instance of acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) in a patient that was determined to be using ibuprofen over the counter for pain relief.27 Another case cautioned use of COX-2 selective inhibitors in renal transplant patients after a patient developed uremic symptoms and required hemodialysis after receiving several days of rofecoxib.28 A similar case of COX-2 inhibitor nephrotoxicity was seen in a patient receiving celecoxib with an elevation in serum creatinine and a renal biopsy negative for acute rejection.29 The patient’s creatinine returned to baseline upon discontinuation of celecoxib. These case studies highlight that COX selectivity may not reduce the safety risk profile of one class of NSAID over another, and this is further validated from our study, as similar risk was seen in patient’s receiving COX-2 selective agents when compared to non selective NSAIDs. Of note, due to the time frame of the analysis there are several COX-2 agents included in the analysis that are no longer available on the market.

The association of NSAIDs has been established in the general population, mostly through retrospective trials and meta-analyses. Literature estimates vary, but commonly reported OR for AKI risk ranges for NSAIDs as a class and among individual NSAIDs from 1.6–2.2.23 Specifically in a VA population, an adjusted OR of 1.82 for AKI was found in patients who were single users of NSAIDs compared to nonusers.14 The effect of NSAID dose has also previously been described in the general population, with studies demonstrating increased risk of AKI with increasing doses; although some correlations have been weak, likely due to low incidences of AKI.7,30,31 In our study, there was a clear dose effect seen, with higher dose NSAIDs being associated with elevated risk of AKI in a given year. However, although not statistically significant, low dose NSAID prescriptions was still associated with a 93% increased risk of AKI compared to no use. With increasing length of NSAID prescriptions there was an exponential increase in risk of AKI events. Even short-term use (7 days) was associated with a significant increase in risk, but chronic use (≥180 days) was associated with a three-fold increase in AKI risk. Utilization of PDC and a generalized model with annualized repeated measures strengthened the likelihood that AKI was truly associated with extended NSAID prescriptions.

One strength of this study is the use of creatinine values to identify patients with AKI rather than using only ICD coding. Utilization of the VA’s comprehensive EHR allows for more accurate and complete lab profiles in patients. This is also coupled with the ability to potentially capture a wider spectrum of medications prescribed to patient since the VA medical record captures all aspects of a patient’s care if they choose to utilize the system. Specifically, many patient’s may receive all medication within the VA system due to lower cost with service connected status even if they receive outside care from a transplant specialist. While strengthened by the comprehensive nature of the VA system, this also produces limitations for this study. Patients may primarily utilize the VA system but may also have labs checked at transplant centers, be seen in emergency department or be admitted at regional non-VA hospitals due to location and medical necessity. These lab values and prescriptions would be missed in this analysis; whereas they may be captured by insurance claims databases. The retrospective nature of the study also limits the ability of the study to infer true causation with NSAIDs and clinical outcomes. AKI was defined in 90-day increments due to limited numbers of lab measurements; thus at most, there were four AKI events per patient-year. The exposure methods that this study used may also potentially overestimate exposure from as needed prescriptions as the maximum possible daily dose and duration was used when patients potentially may have taken these medications less frequently. Finally, it should be noted that we could not accurately assess which patients had zero copays on their prescriptions and thus truly determine which were more likely to purchase over the counter NSAIDs.

In summary, the results of this analysis demonstrate that overall NSAID prescriptions in kidney transplantation is likely similar to the general population, but the incidence of AKI associated with these agents appears to be higher in kidney transplant recipients. Further research is needed to clarify the impact of type of NSAID, dose of NSAID and impact on long-term outcomes, particularly graft and patient survival.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K23DK099440. This work was supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234–2005-37011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government

Abbreviations:

- AKI

acute kidney injury

- BMI

body mass index

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- CIT

cold ischemia time

- CPRS

Computerized Patient Record System

- DCD

donation after circulatory death

- ECD

extended criteria donors

- NSAIDs

non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- OTC

over the counter

- OR

odds ratio

- PDC

proportion of days covered

- TDD

total daily dose

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- VA

Veterans Affairs

- VAMC

Veterans Affairs Medical Center

- VISTA

Veterans Information Systems and Technology Architecture

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information:

A table defining dose thresholds determining low versus high dose NSAID prescriptions for patients in the cohort is included in the supporting information as Table S1.

References:

- 1.Harirforoosh S,Jamali F. Renal adverse effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2009;8(6):669–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whelton A Nephrotoxicity of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs: Physiologic Foundations and Clinical Implications. Am J Med. 1999;106(5B):13S–24S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rahman S, Malcoun A. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs, Cyclooxygenase-2, and the Kidneys. Prim Care. 2014;41(4): 803–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curiel RV, Katz JD. Mitigating the Cardiovascular and Renal Effects of NSAIDs. Pain Med. 2013;14 Suppl 1:S23–S28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn M The Role of Arachidonic Acid Metabolites in Renal Homeostasis. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs Renal Function and Biochemical, Histological and ClinicaI Effects and Drug Interactions. Drugs. 1987;33 Suppl 1:56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perazella MA. COX-2 selective inhibitors: analysis of the renal effects. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2002;1(1):53–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pérez Gutthann S, García Rodríguez LA, Raiford DS, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of hospitalization for acute renal failure. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(21):2433–2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang X, Donnan PT, Bell S, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced acute kidney injury in the community dwelling general population and people with chronic kidney disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Naesens M, Kuypers DRJ, Sarwal M. Calcineurin Inhibitor Nephrotoxicity. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):481–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adu Jawdeh BG, Govil A. Acute Kidney Injury in Transplant Setting: Differential Diagnosis and Impact on Health and Health Care. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2017;24(4):228–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stahl RAK. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents in patients with a renal transplant. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(5):1119–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Yazbi AF, Eid AH, El-Mas MM. Cardiovascular and renal interactions between cyclosporine and NSAIDs: Underlying mechanisms and clinical relevance. Pharmacol Res. 2018;129:251–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ojo AO. Cardiovascular Complications After Renal Transplantation and Their Prevention. Transplantation. 2006; 82(5):603–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lafrance JP, Miller DR. Selective and non-selective non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the risk of acute kidney injury. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009;18(10):923–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.García Rodríguez LA, Tacconelli S, Patrignani P. Role of Dose Potency in the Prediction of Risk of Myocardial Infarction Associated with Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in the General Population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(20):1628–1636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schneider V, Lévesque LE, Zhang B, et al. Association of Selective and Conventional Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs with Acute Renal Failure: A Population-based, Nested Case-Control Analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;164(9):881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, et al. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: A new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(6):461–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heleniak Z, Cieplińska M, Szychliński T, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol. 2017;30(6): 781–786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plantinga L, Grubbs V, Sarkar U, et al. Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use Among Persons With Chronic Kidney Disease in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(5):423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel K, Diamantidis C, Zhan M, et al. Influence of creatinine versus glomerular filtration rate on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescriptions in chronic kidney disease. Am J Nephrol. 2012;36(1):19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehrotra A, Rose C, Pannu N, et al. Incidence and Consequences of Acute Kidney Injury in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):558–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingrasciotta Y, Sultana J, Giorgianni F, et al. Association of Individual Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs and Chronic Kidney Disease: A Population-Based Case Control Study. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bunning RD, Barth WF. Sulindac. A Potentially Renal-Sparing Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug. JAMA. 1982;248(21):2864–2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patrono C, Pierucci A. Renal Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Chronic Glomerular Disease. Am J Med. 1986;81(2B):71–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ungprasert P, Cheungpasitporn W, Crowson CS, et al. Individual non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of acute kidney injury: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Intern Med. 2015;26(4):285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Winkelmayer WC, Waikar SS, Mogun H, et al. Nonselective and Cyclooxygenase-2-Selective NSAIDs and Acute Kidney Injury. Am J Med. 2008;121(12):1092–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stoves J, Rosenberg K, Harnden P, et al. Acute interstitial nephritis due to over-the-counter ibuprofen in a renal transplant recipient. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13(1):227–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woywodt A, Schwarz A, Mengel M. Nephrotoxicity of Selective COX-2 Inhibitors. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(9):2133–2135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clifford TM, Pajouman M, Johnston TD. Celecoxib-Induced Nephrotoxicity in a Renal Transplant Recipient. Pharmacotherapy. 2005;25(5):773–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry D, Page J, Whyte I, et al. Consumption of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the development of functional renal impairment in elderly subjects. Results of a case-control study. Br J Clin Pharamcol. 1997;44(1):85–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Griffin MR, Yared A, Ray WA. Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs and Acute Renal Failure in Elderly Persons. Am J Epidemiol. 2000;151(5):488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.