Abstract

Background

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a Gram-negative bacterium widely distributed in marine environments and a well-recognized invertebrate pathogen frequently isolated from seafood. V. parahaemolyticus may also spread into humans, via contaminated, raw, or undercooked seafood, causing gastroenteritis and diarrhea.

Methods

A Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)-based detection system was used to detect pathogenic levels of this microorganism (105 CFU/ml) with Molecular Mirroring using iron nanoparticles coated with target-specific biomarkers capable of binding to DNA of the target microorganism. The NMR system generates a signal (in milliseconds) by measuring NMR spin–spin relaxation time T2, which correlates with the amount of microorganism DNA.

Results

Compared with conventional microbiology techniques such as real-time PCR (qPCR), the NMR biosensor showed similar limits of detection (LOD) at different concentrations (105–108 CFU/ml) using two DNA extraction methods. In addition, the NMR biosensor system can detect a wide range of microorganism DNAs in different matrices within a short period of time.

Conclusion

NMR biosensor represents a potential tool for diagnostic and quality control to ensure microbial pathogens such as V. parahaemolyticus are not the cause of infection. The “hybrid” technology (NMR and nanoparticle application) opens a new platform for detecting other microbial pathogens that have impacted human health, animal health and food safety.

Keywords: Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Food safety, Aquaculture, Biosensors

At a glance of commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is the leading cause of gastrointestinal illness following consumption of raw or undercooked seafood. This bacterium is also a significant biohazard for the aquaculture industry, causing early mortality syndrome in shrimp. Rapid detection of V. parahaemolyticus and other pathogens is crucial to ensuring food safety and public health.

What this study adds to the field

Conventional microbial detection techniques are costly, time-consuming and require specialized equipment. This research demonstrates a nuclear magnetic resonance method for rapid, sensitive and highly specific detection of V. parahaemolyticus in shrimp tissue, allowing rapid response to public health concerns compared to conventional detection techniques.

Microbial infections in animals raised as food sources remain a major challenge in public health and food safety. Overt and latent microbial infections of animal species in aquafarms and animal farms represent a biohazard for human health [1] and cause interruption in food production with substantial economic loss [2]. The FDA has established several detection methods that every food-related factory and industry must follow [3], [4]. However, these detection methods are expensive and time-consuming. A rapid, specific and affordable analytical system to detect microbial pathogens before and after food processing is desired to protect public health and ensure food safety [5].

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is a Gram-negative bacterium widely distributed in marine environments and a well-recognized invertebrate pathogen frequently isolated from seafood [6], [7], [8], [9]. V. parahaemolyticus may also spread into humans, via contaminated, raw, or undercooked seafood, causing gastroenteritis and diarrhea [10], [11], [12]. This bacterium has recently become a biohazard for the aquaculture industry being the origin of an emerging disease named early mortality syndrome (EMS, also known as acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease, AHPND) [13], [14].

A recently identified 70 kb plasmid (pVA-1) in EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus strains which contains the binary toxin PirAB [15], responsible for EMS in shrimp was selected for this study. Molecular diagnostic methods using these genes as targets for PCR amplification and quantification are used [16], [17], [18]. Bioassays to detect microbial pathogens in various matrices (water, animal tissue, blood, saliva, etc.) using its core Molecular Mirroring (M2) NMR technology are developed. In brief, the M2 technology is a novel and patented approach that uses iron nanoparticles coated with target-specific biomarkers capable of binding to DNA of the target microorganism [U.S. Patent No. 9,442,110 B2]. Custom-designed primers that bind specific genomic regions such as toxin or virulence factor genes present in the target microorganism are used for DNA amplification. After mixing and incubating DNA with nanoparticles, a DNA-nanoparticle complex is formed which is detected by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) using the NMR biosensor. The NMR biosensor generates a signal (in milliseconds) by measuring NMR spin–spin relaxation time T2, which is correlated with the amount of microorganism DNA.

The goal of the present study is to demonstrate a detection system based on the combination of NMR and molecular biology, for EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus detection in shrimp tissues in comparison with a current diagnostic method, real-time PCR (qPCR).

Materials and methods

All experiments were carried out at Aquaculture Pathology Laboratory, University of Arizona. Shrimp were kept in a 90-L tank filled with artificial seawater at a salinity of 25 ppt and equipped with a submerged biological filter [19]; water temperature was maintained at 28 °C. A total of 15 specific-pathogen free (SPF) Penaeus vannamei (mean weight: 8 g) were stocked in the tanks and fed twice daily using a commercial diet (Rangen Aquaculture feeds).

The EMS-pathogenic strain of V. parahaemolyticus 13-028/A3 was cultured in TSB+ (Tryptic soy broth plus 2% NaCl) at 28–29 °C with gentle (100 rpm) shaking [14]. The pathogenicity of EMS-strain was determined by laboratory infections through immersions or per os feeding, followed by histological examinations as previously described [14], and also confirmed by PCR targeting toxin primers [18].

For the specificity test, one non-pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strain (13-028/A2) from Vietnam and two Vibrio harveyi strains (15-235/C and 14-388/19) from USA and Ecuador were used. Bacterial identifications were conducted using 16S rRNA sequencing [20] and species-specific PCR [21], [22], [23].

As an internal control, the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum (ATCC8014) was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) and cultured in De Man, Rogosa, and Sharpe (MRS) broth at 30 °C for 24 h.

Bacteria spiking in shrimp tissues and DNA extraction are described as the following: Shrimp hepatopancreas was collected, homogenized with 2.5% saline solution (at 100 mg/ml) and spiked with the EMS-pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strain at two different concentrations (105 CFU/ml, 108 CFU/ml) and L. plantarum (105 CFU/ml) as a control.

Two different DNA extraction methods were performed in triplicate.

A. Universal Sample Prep (USP) protocol was developed by this team: 500 μl of lysis buffer and 20 μl of proteinase K (1 mg/ml) were added to approximately 150 μl of the sample, mixed, heated at 95 °C for 5 min and frozen at −80 °C for 15 min. Then, samples were heated at 95 °C for 1 min and centrifuged at maximum speed for 5 min. The supernatant of each sample was collected and mixed with a solution containing 300 μl of molecular grade water, 354 μl of ammonium acetate (2.5 M) and 400 μl of chloroform. After 5 min of centrifugation at maximum speed the upper phase was collected and precipitated with isopropanol for 1 min at room temperature. After that, the tubes were centrifuged for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was washed with 1 ml of 75% ethanol solution. After repeating the centrifugation step and discarding the supernatant, the pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of 0.1× Tris–EDTA (TE) buffer.

B. Maxwell® protocol was obtained from commercial supplier: DNA extraction was performed using a Maxwell-16® Cell LEV DNA purification kit (Promega), following manufacturer instructions.

To conduct a specificity test, the shrimp tissue was collected, homogenized with saline solution (2.5%) and spiked with the internal control (L. plantarum) at 105 CFU/ml. Each homogenate was then spiked with one of three Vibrio strains at 108 CFU/ml: Non-pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus (13-028/A2), V. harveyi (15-235/C), or V. harveyi (14-388/19). DNA was extracted using the USP protocol.

Next, bioassays were performed as the following: Seven SPF experimental shrimp were transferred to each tea jar (3-L) filled with seawater at a salinity of 25 ppt and stocked with aeration. The EMS pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strain 13-028 A/3 was inoculated to TSB+ (Tryptic soy broth plus 2% NaCl2), grown overnight to 1 × 109 CFU/ml and mixed with shrimp feed at a 1:1 ratio for 10 min. For infection, six experimental shrimp were fed with bacteria-mixed shrimp feed at 10% body weight and the negative control shrimp was fed with normal feed. On the next day, the hepatopancreas was collected from the shrimp and DNA was extracted by USP method.

Biotinylated primers for PCR amplification were purchased from IDT, specific for the EMS pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus (M1693: 5′-TG CGG CAA AAG ATG ATT ACA-3′, M1694: 5′-AT GCA CAT CAG AAT CGG TGA-3) and L. plantarum (M1699: 5′-TGG CTG ACA CCA CAA AAT GT-3′, M1700: 5′-GGC GCT AAG CTG TAA TCG AC-3′). PCR master mix for target amplification contained 0.3 μM of each biotinylated primer, 2 mM of MgCl2, 200 μM of dNTPs, 5 μl of polymerase buffer, 5 μl of template and 2 U of polymerase in a total of 25 μl. PCR settings were 40 s at 98 °C, 38 cycles of 6 s at 98 °C and 5 s at 60 °C, and a 4 °C final step in a Bioer thermal cycler.

Nanoparticle addition and NMR detection were then conducted. A mixture of 3.5 μl of 20 ng/μl 200 nm streptavidin-coated iron beads (Ademtech), 24 μl of 1× PBS (phosphate-buffer saline) and 6 μl of the PCR product was measured in the NMR system (baseline T2 signal). Tubes were incubated at room temperature for 10 min, vortexed and measured again in the NMR system (final T2 signal). The resulting ΔT2 was obtained by subtracting the baseline signal from each final T2 measurement and was used for the plots and statistics. All measurements (baseline and final) were performed in duplicate. The NMR system used in this study is described in the United States Patent Application Publications [U.S. Patent No. 9,442,110 B2].

For quantification of EMS plasmid, a qPCR assay was performed as previously described [16]. Extracted DNA was added to a qPCR mixture containing 0.3 μM of each primer and 0.1 μM TaqMan probe to a final volume of 10 μL. The qPCR profile consisted of 20 s at 95 °C followed by 40 cycles of 3 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C. Amplification detection and data analysis for qPCR assays were performed with a StepOnePlus PCR system (Life Technologies).

All experiments were performed in triplicate. Statistical analyses of the average, standard error and t-Test analysis were calculated by Microsoft Office Excel 2007.

Results

USP vs automated DNA extraction method

In order to demonstrate that USP method works as well as other DNA extraction methods, USP DNA extraction method was compared with the automated Maxwell® system.

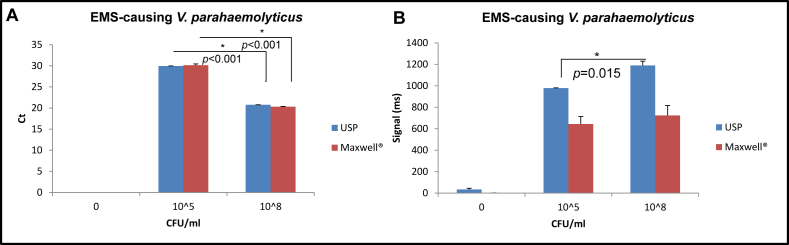

After DNA extractions following the two different methods, EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus were detected either by qPCR (Fig. 1A) or by performing a standard PCR followed by incubation with nanoparticles and detection with the NMR system (Fig. 1B). The NMR biosensor system was able to detect EMS pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus following the two different DNA extraction methods. The NMR system generated a higher signal (1189 ms) at higher bacterial concentration (108 CFU/ml) and a lower signal (978 ms) at lower target bacterium dose (105 CFU/ml) when USP was used for DNA extraction compared with the Maxwell® method. Furthermore, the signals detected were significantly different between the two bacterium concentrations (p = 0.015). Data suggests that the DNA extraction method per USP was as successful as the automated Maxwell® system, one of the DNA extraction methods commercially available.

Fig. 1.

Detection of V. parahaemolyticus pathogenic strain at different doses (105, 108 CFU/ml) from DNA extracted with two different protocols (USP, Maxwell®) by cycle threshold (Ct) from qPCR (A) and by NMR (B) measured in milliseconds (ms). X-axis shows the concentration of spiked bacteria in homogenized shrimp hepatopancreas.

Fig. 1A shows the cycle threshold (Ct) at which EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus was detected after qPCR reaction. In that case, Ct values were the same using both DNA extraction methods, and they were significantly different (p < 0.001) based on the microorganism concentration with Ct = 29.94 for 105 CFU/ml and Ct = 20.76 for 108 CFU/ml when using USP method and Ct = 30.15 for 105 CFU/ml and Ct = 20.31 for 108 CFU/ml when using the alternative method. The same DNA extracts were used for the two different detection methods (NMR system and qPCR).

Because V. parahaemolyticus pathogenicity has been established in shrimp with the LD50 dose of 1 × 105 CFU/shrimp [24], these results also show that the NMR biosensor was able to detect and distinguish pathogenic levels of the target microorganism from higher concentrations. Based on these results, further experiments using USP were performed.

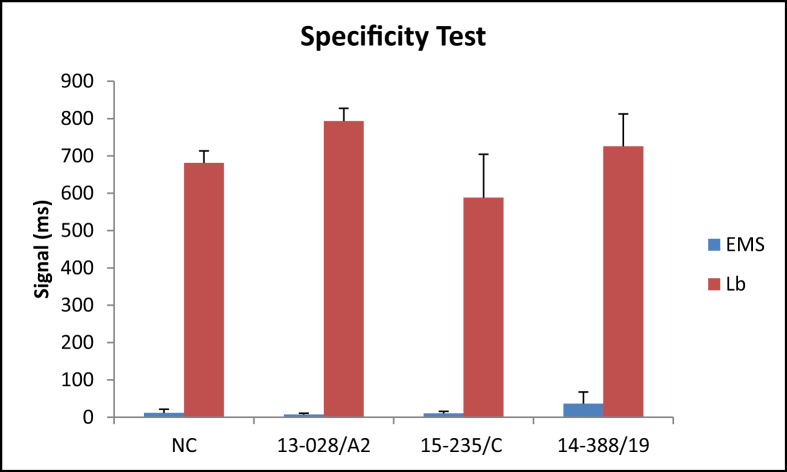

Specificity test

Next step in this study was to corroborate the specificity of the EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus detection assay in shrimp tissues using the NMR biosensor. After DNA extraction, PCR amplification, and incubation with nanoparticles, the NMR biosensor was able to detect the internal control in all the samples. There was no detection of non EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus or V. harveyi strains (Fig. 2). Results were confirmed by qPCR analysis, where all samples were negatives (data not shown). From these results, we concluded that the NMR assay is specific for pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strains responsible for EMS in shrimp.

Fig. 2.

Specificity of the assay was tested against a non-pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strain (13-028/A2) and 2 strains of V. harveyi (15-235/C, 14-388/19). The negative control corresponds to the hepatopancreas spiked with the internal control only. Abbreviations used: EMS: early mortality syndrome; Lb: Lactobacillus as control.

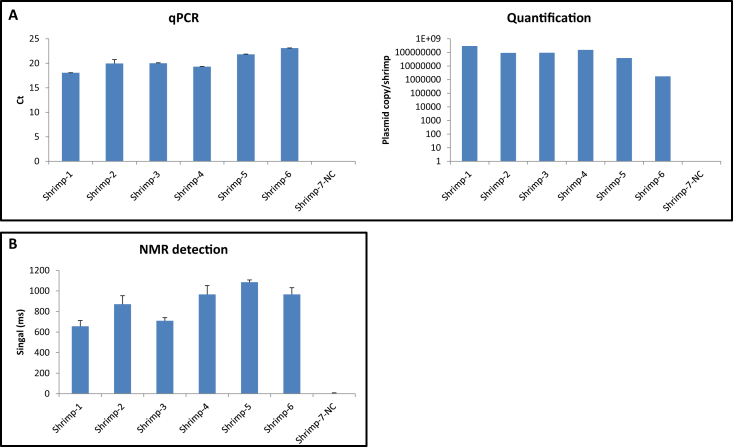

Detection of EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus in laboratory-infected shrimp and healthy shrimp were analyzed using the NMR biosensor and qPCR systems. Fig. 3 shows how both analytical systems were able to detect the presence of the virulence plasmid in all the samples tested with the exception of the negative control. The presence of the pathogen was quantified by qPCR detecting a range of 1.7 × 107–2.9 × 108 plasmid copies per shrimp (Fig. 3A). The NMR biosensor showed NMR signals for positive specimens ranged between 656–1085 ms. These results indicate that the NMR biosensor and qPCR are able to detect infected specimens.

Fig. 3.

Infected specimen detection carried out by qPCR (A) and NMR biosensor system (B); plasmid quantification was obtained from the dose response curve of the positive control by qPCR.

Sensitivity test

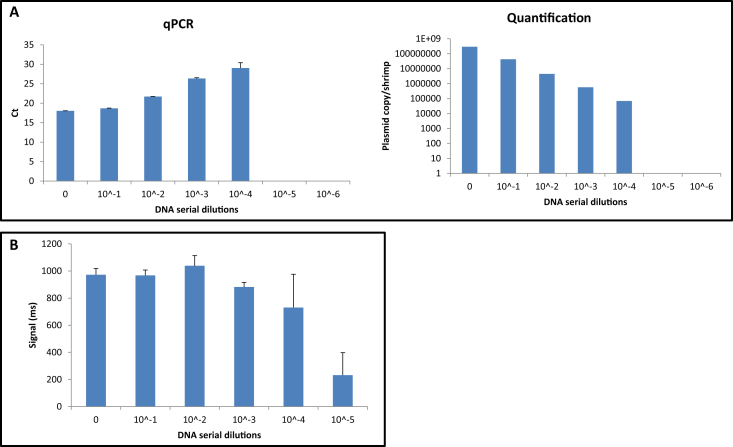

In order to determine the sensitivity of both detection systems (the NMR biosensor and qPCR), DNA from one of the infected specimens was selected to establish the limit of detection (LOD). DNA serial dilutions from 10 to 106 were made and all dilutions were processed with NMR biosensor and qPCR. For both systems, 104 log dilution was the LOD (Fig. 4), obtaining a 730 ms signal and Ct = 29.0 (6.89 × 104 plasmid copies/shrimp) with the NMR detection system and qPCR system, respectively.

Fig. 4.

A sensitivity test was performed to determine LOD of each system in the detection of EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus (A) qPCR; (B) NMR biosensor.

These results demonstrate that the NMR biosensor is as sensitive as qPCR, the gold standard that is currently used in pathology laboratories for EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus diagnosis [17].

Discussion

The results of the study are significant because a detection of >104 CFU during EMS outbreaks would imply potential intraspecies and interspecies spread of the pathogenic bacteria [25], [26]. The capability to test for cross-reactivity within the Vibrio genus may also be clinically relevant. Because this method provides reliable identification of Vibrio genus and potential pathogenic Vibrio species in the food safety area, it can be applied to early clinical diagnosis, thereby preventing humans against Vibrio infection.

As demonstrated from a series of experiments on bioassay, specificity and sensitivity of the methodology using combined NMR, molecular biology and nanoparticle application, the NMR biosensor is capable of detecting microbial pathogens with high degree of sensitivity and specificity. In addition, this biosensor system can detect a wide range of microorganism DNAs in different matrices within a short period of time, compared with conventional microbiology techniques that require at least 24 h or with conventional PCR that requires electrophoresis of agarose gels preparation in order to obtain qualitative results [27], [28]. The time factor of rapidly detecting microbial pathogen in specimens for food production and consumption is crucial to ensure food safety [29]. Other novel molecular biology techniques including qPCR have been applied to microbial detection [16]; however, they are relatively expensive and require specialized equipment and personnel for performance in the field [30], [31]. We have demonstrated in this study that the NMR biosensor offers an NMR-DNA based pathogen detection system [U.S. Patent No. 9,442,110 B2], for the detection of pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus, a shrimp pathogen responsible for elevated rates of shrimp deaths and economic losses for aquaculture industry. In addition, the NMR biosensor provides high sensitivity and specificity with similar LOD when compared with commercially available detection methodology.

Conclusion

The NMR biosensor, through the combination of molecular biology and NMR technology, represents a novel, rapid, sensitive and highly specific methodology for the detection of pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus in shrimp tissue. The NMR biosensor works specifically for EMS-causing V. parahaemolyticus detection using DNA from two different extraction methods and shows high sensitivity being able to generate different signals based on threshold concentration.

In conclusion, the NMR biosensor represents a potential tool for rapid yet sensitive diagnostic as well as quality control to ensure microbial pathogens such as V. parahaemolyticus are not the cause of infection. In addition, such detection system opens a new window to be used as a platform for detection of other microbial pathogens that have impacted human health, food and also animal health.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Cabello F.C., Godfrey H.P., Buschmann A.H., Dölz H.J. Aquaculture as yet another environmental gateway to the development and globalisation of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:e127–e133. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00100-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Godfray H.C., Beddington J.R., Crute I.R., Haddad L., Lawrence D., Muir J.F. Food security: the challenge of feeding 9 billion people. Science. 2010;327:812–818. doi: 10.1126/science.1185383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.FDA technical bulletin number 5. Macroanalytical procedures manual online 1984, https://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/LaboratoryMethods/ucm2006953.htm Electronic Version/; 1998 [Accessed 23 November 2017].

- 4.Maturin L, Peeler JT. Bacteriological analytical manual online. BAM: aerobic plate count, 8th ed. https://www.fda.gov/Food/FoodScienceResearch/LaboratoryMethods/ucm063346.htm/; 2001 [Accessed 23 November 2017].

- 5.Williams T.C., Froelich B., Oliver J.D. A new culture-based method for the improved identification of Vibrio vulnificus from environmental samples, reducing the need for molecular confirmation. J Microbiol Methods. 2013;93:277–283. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2013.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takahashi H., Iwade Y., Konuma H., Hara-Kudo Y. Development of a quantitative real-time PCR method for estimation of the total number of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in contaminated shellfish and seawater. J Food Prot. 2005;68:1083–1088. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.5.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson C.N., Bowers J.C., Griffitt K.J., Molina V., Clostio R.W., Pei S. Ecology of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in the coastal and estuarine waters of Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, and Washington (United States) Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;78:7249–7257. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01296-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tall A., Teillon A., Boisset C., Delesmont R., Touron-Bodilis A., Hervio-Heath D. Real-time PCR optimization to identify environmental Vibrio spp. strains. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:361–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang R., Zhong Y., Gu X., Yuan Y., Saeed A.F., Wang S. The pathogenesis, detection, and prevention of Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:144. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin J.B., De Paola A., Bopp C.A., Martinek K.A., Napolilli N.P., Allison C.G. Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus gastroenteritis associated with Alaskan oysters. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1463–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.González-Escalona N., Cachicas V., Acevedo C., Rioseco M.L., Vergara J.A., Cabello F. Vibrio parahaemolyticus diarrhea, Chile, 1998 and 2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:129–131. doi: 10.3201/eid1101.040762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker-Austin C., Stockley L., Rangdale R., Martinez-Urtaza J. Environmental occurrence and clinical impact of Vibrio vulnificus and Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a European perspective. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2010;2:7–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lightner D.V., Redman R.M., Pantoja C.R., Noble B.L., Tran L. Early mortality syndrome affects shrimp in Asia. Glob Aquac Advocate. 2012:40–47. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tran L., Nunan L., Redman R.M., Mohney L.L., Pantoja C.R., Fitzsimmons K K. Determination of the infectious nature of the agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis syndrome affecting penaeid shrimp. Dis Aquat Organ. 2013;105:45–55. doi: 10.3354/dao02621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee C., Chen I., Yang Y., Ko T., Huang Y., Huang J. The opportunistic marine pathogen Vibrio parahaemolyticus becomes virulent by acquiring a plasmid that expresses a deadly toxin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:10798–10803. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503129112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Han J.E., Tang K.F.J., Lightner D.V. Genotyping of virulence plasmid from Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolates causing acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease in shrimp. Dis Aquat Organ. 2015;115:245–251. doi: 10.3354/dao02906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Han J.E., Tang K.F.J., Pantoja C.R., White B.L., Lightner D.V. QPCR assay for detecting and quantifying a virulence plasmid in acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) due to pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Aquaculture. 2015;442:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han J.E., Tang K.F.J., Tran L.H., Lightner D.V. Photorhabdus insect-related (Pir) toxin-like genes in a plasmid of Vibrio parahaemolyticus, the causative agent of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) of shrimp. Dis Aquat Organ. 2015;113:33–40. doi: 10.3354/dao02830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White B.L., Schofield P.J., Poulos B.T., Lightner D.V. A laboratory challenge method for estimating Taura syndrome virus resistance in selected lines of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei. J World Aquac Soc. 2002;33:341–348. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weisburg W.G., Barns S.M., Pelletier D.A., Lane D.J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bej A.K., Patterson D.P., Brasher C.W., Vickery M.C.L., Jones D.D., Kaysner C.A. Detection of total and hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tl, tdh and trh. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;36:215–225. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.KimYB, Okuda J., Matsumoto C., Takahashi N., Hashimoto S., Nishibuchi M. Identification of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains at the species level by PCR targeted to the toxR gene. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1173–1177. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1173-1177.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fukui Y., Sawabe T. Improved one-step colony PCR detection of Vibrio harveyi. Microbes Environ. 2007;22:1–10. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.23.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sudheesh P.S., Xu H. Pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in tiger prawn Penaeus monodon Fabricius: possible role of extracellular proteases. Aquaculture. 2001;196:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Phiwsaiya K., Charoensapsri W., Taengphu S., Dong H.T., Sangsuriya P., Nguyen G.T.T. A natural Vibrio parahaemolyticus ΔpirAVppirBVp+ mutant kills shrimp but produces neither PirVp toxins nor acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease lesions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83 doi: 10.1128/AEM.00680-17. e00680-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khimmakthong U., Sukkarun P. The spread of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in tissues of the Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei analyzed by PCR and histopathology. Microb Pathog. 2017;113:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Persing D.H. Diagnostic molecular microbiology current challenges and future directions. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;16:159–163. doi: 10.1016/0732-8893(93)90015-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang P., Hash S., Park K., Wong C., Doraisamy L., Petterson J. Application of nuclear magnetic resonance to detect toxigenic Clostridium difficile from stool specimens: a proof of concept. J Mol Diagn. 2017;19:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2016.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foodborne Disease Burden Epidemiology Reference Group. WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases, 2007–2015 http://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/foodborne_disease/fergreport/en/; 2015 [Accessed 23 November 2017].

- 30.Kim H.J., Ryu J.O., Lee S.Y., Kim E.S., Kim H.Y. Multiplex PCR for detection of the Vibrio genus and five pathogenic Vibrio species with primer sets designed using comparative genomics. BMC Microbiol. 2015;15:239. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0577-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nunan L., Lightner D., Pantoja C., Gomez-Jimenez S. Detection of acute hepatopancreatic necrosis disease (AHPND) in Mexico. Dis Aquat Organ. 2014;111:81–86. doi: 10.3354/dao02776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]