Abstract

Background

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE), a fulminant encephalopathy, is often found in childhood. It is still uncertain whether adult patients with ANE display clinical features different from patients with typical pediatric onset. Furthermore, alterations in neuroinflammatory factors in patients with ANE have not been well-characterized. Here, we present an adult patient with ANE, and review all reported adult ANE cases in the literature.

Methods

Serum levels of five cytokines were checked in an adult patient with ANE and compared with gender/age-matched controls. Literature search was performed with PubMed, using the term as “acute necrotizing encephalopathy” with the filter of adult 19 + years.

Results

A total of 13 adult patients were reviewed. Compared with pediatric patients, adult ANE patients had similar clinical symptoms, biochemical data, and neuroimage findings, whereas adult ANE were more female-biased (female:male, 9:4) with a worse prognosis. Elevated cytokine levels in the serum and/or CSF is found in both adult-onset and pediatric-onset ANE. We found significantly elevated serum levels of IL-6 (17.17 pg/mL; healthy control: 1.43 ± 1.22 pg/mL) and VCAM-1 (3033.92 ng/mL; healthy control: 589.71 ± 133.13 ng/mL), and decreased serum TGF-β1 level (14.78 ng/mL, healthy controls: 25.81 ± 6.97 ng/mL) in our patient.

Conclusions

Our findings clearly delineate the clinical features and further indicate the potential change in cytokine levels in adult patients with ANE, advancing our understanding of this rare disease.

Keywords: Acute necrotizing encephalopathy, Adult, Cytokine, VCAM-1

At a glance of commentary

Scientific background on the subject

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE), a fulminant encephalopathy presenting with symmetrical lesions in the thalami, putamina, cerebral and cerebellar white matter, and brain stem tegmentum, is often found in childhood. It is still uncertain whether adult patients with ANE display clinical features different from patients with typical pediatric onset.

What this study adds to the field

We present an adult patient with ANE, and found high levels of IL-6 and VCAM-1 in the serum of our patient. By studying all reported adult ANE cases in the literature, we further found that adult ANE patients were more female-biased with a worse prognosis compared with classical pediatric ANE patients.

Acute necrotizing encephalopathy (ANE) is a fulminant encephalopathy characterized by multifocal symmetrical lesions in the thalami and other locations such as cerebral white matter, cerebellar medulla, and brainstem tegmentum [1], [2]. More than 90% of patients had fever and upper airway infection prior to the onset of encephalopathy [1]. Almost all the patients develop seizures and disturbance of consciousness accompanied with decerebrate or decorticate posture [2]. The pathogenesis of ANE could be immune-mediated. It has been reported that cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-15, play a role in ANE [3], [4], [5].

ANE often affects children younger than 5 years old in the Far East, mostly in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea [1], [2], [6]. Adult cases were seldom reported. It is still uncertain whether adult patients with ANE display clinical features different from patients with typical pediatric onset. Furthermore, alterations in neuroinflammatory factors in patients with ANE have not been well-characterized. Here, we present an adult case in which we examined five common microglia/macrophage-mediated cytokines to reveal potential biomarkers in adult ANE. To clearly delineate the clinical features of adult ANE, we examined reported cases of adult ANE and compared the clinical presentations of our patients with those reported in the literature. Our findings may improve our understanding of this immune-mediated encephalopathy.

Material and methods

Report a case

We presented an adult female case of ANE. We diagnosed ANE according to the diagnostic criteria suggested by Mizuguchi M [3]. The criteria are summarized below:

-

1.

Rapid conscious change and convulsions following a febrile viral infection.

-

2.

Elevation of protein without pleocytosis in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).

-

3.

CT or MRI showing symmetric lesions in bilateral thalami; Other locations such as cerebral periventricular white matter, internal capsule, putamen, upper brain stem tegmentum and cerebellar medulla are also common; Except above locations, no other intracranial lesions.

-

4.

Elevation of serum aminotransferases but not ammonia.

-

5.

Exclusion of resembling diseases.

Cytokine, anti-glycolipid and paraneoplastic antibody analysis

Microglial activation plays an important role in neuroinflammatory diseases [7]. Therefore, we used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) Kits to check the serum levels of five common microglia/macrophage-mediated cytokines, including IL-6 (R&D), matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 (R&D), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF, R&D), tumor growth factor (TGF)-β1 (R&D) and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1 (R&D) [8]. All serum samples were collected before treatment with high-dose steroid. Serum of gender and age-matched controls were recruited from 18 female healthy volunteers (mean age: 37.56 ± 11.51 years). Anti-ganglioside (anti-GD1a, anti-GD1b, anti-GM1, anti-GM2, anti-GM3, anti-GQ1b and anti-GT1b) and paraneoplastic anti-neuronal antigen (anti-TITIN, anti-SOX1, anti-RECOVERIN, anti-Hu, anti-Yo, anti-Ri, anti-Ma2, anti-CV2 and anti-AMPHIPHYSIN) autoantibodies will be tested by immunoblot strip kit (Euroimmun) according to the manufacturer's instruction.

Literature search and review

Literature search was performed with PubMed. We searched the term as “acute necrotizing encephalopathy” with the filter of adult 19 + years. The literature were reviewed from 1979, which is when ANE was first reported [9], until November 2015. We enrolled case reports or case series that had individual information about clinical manifestations, laboratory data, brain images, and outcomes of adult patients with ANE. Twelve adult patients with ANE were identified in the literature [10], [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21]. In total, 13 patients, including this patient, are reviewed and discussed [Table 1].

Table 1.

Clinical information of adult-onset ANE in 13 patients.

| Age/Sex | Clinical symptoms & signs | Laboratory findings |

Characteristic finding of images |

Treatment | Outcome | Reference | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | CSF | CT (Low-density lesions) | MRI (Hyperintensity lesions on T2 FLAIR or T2-weighted) | ||||||

| 1 | 30/F | fever, flu-like symptoms, CD, convulsive seizure, decerebrate posture, LR (−/−), DTR ↓, BS (+/+) | Leukopenia, CRP↑, ALT/AST ↑ IL-6 ↑, VCAM-1 ↑ |

No pleocytosis, protein ↑, IgG index ↑ |

Bil. Th | Bil. Th, CWM, CM, BT; microbleeds on SWI | Anti-viral, Antimicrobials, PT, PP | Expired | our case |

| 2 | 80/M | fever, flu-like symptoms, CD, convulsive seizure, corneal reflex (−/−), VOR (−) | DIC, acute liver failure, Cr ↑ Inf B (+) IL-6 ↑ |

NA | Bil. Th | NA | Anti-viral, PT, IVIG |

Expired | [11] |

| 3 | 23/F | fever, flu-like symptoms, CD, decerebrate posture, LR (−), cornea reflex (−), DTR ↑ | Thrombocytopenia, ALT/AST ↑ | protein ↑ | NA | Bil. Th, brainstem, and cerebellum; Bil. Th hemorrhage on gradient sequence | Antimicrobials | Expired | [17] |

| 4 | 39/F | diarrhea, CD, decorticate rigidity, LR (−), BS(+) | LDH ↑, ALT/AST ↑ | No pleocytosis, protein ↑ | Bil. Th, basal ganglia, CWM, and brainstem | Bil. Th, basal ganglia, CWM, and brainstem | NA | Persistent vegetative state | [19] |

| 5 | 40/M | fever, diarrhea, flu-like symptoms, CD | LDH ↑, CRP↑, ALT/AST↑, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, Inf A-H1N1 (+) in nasopharyngeal swabs |

No pleocytosis, protein ↑ | Bil. Th, brainstem | Bil. Th and brainstem; microbleeds on gradient echo | Anti-viral, Antimicrobials | Little improvement | [20] |

| 6 | 27/F | flu-like symptoms, CD, LR (−), corneal reflex (−) | Inf A RT-PCR (+) | No pleocytosis, protein ↑ | diffuse cerebral white matter edema | Bil Th, CWM, CM, brainstem; microbleeds on gradient echo | Anti-viral | Expired | [13] |

| 7 | 76/F | fever, CD, corneal reflex (−/−), VOR (−), DTR ↓ | LDH ↑, CPK ↑, ALT/AST ↑ IL-6 ↑, IL-10 ↑ |

Lymphocytic pleocytosis, protein ↑, IL-6 ↑ | NA | Bil. Th, globus pallidus, caudate head, BT | PT, IVIG | Little improvement | [18] |

| 8 | 22/M | fever, CD | ALT ↑, Cr ↑ Inf A IgA (+) |

No pleocytosis, protein ↑ | NA | Bil. Th | Anti-viral, antimicrobials | Complete recovery | [9] |

| 9 | 24/F | fever, vomiting, diarrhea, CD, pathologic reflex (+) | thrombocytopenia, lactate ↑, ALT/AST ↑, Cr ↑, coagulopathy |

No pleocytosis protein ↑ | Bil. Th | Bil. Th, CWM, CM | Anti-viral | Mild cognitive disability | [12] |

| 10 | 27/M | fever, flu-like symptoms, CD, convulsive seizure, decerebrate rigidity, DTR ↑ | Inf A-H3N2 (+) | Neutrophilic pleocytosis, protein ↑ IL-1β ↑, IL-6 ↑ |

Bil. Th | Bil. Th, brainstem, and CWM | Anti-viral, PT | Wheelchair-bound | [10] |

| 11 | 20/F | fever, CD, right limbs convulsion, decerebrate posture, pupil dilation, LR (−), DTR ↓, BS (+/−) | ALT ↑ | NA | NA | Bil. Th, BT | Anti-viral, steroid, IVIG |

Left hemiparesis, personality change | [14] |

| 12 | 46/F | fever, CD, convulsion, DTR ↑, pathologic reflex (+) |

LDH ↑, γ-globulin↑ hypoalbuminemia | No pleocytosis protein ↑ | Bil. Th | Bil. Th | PT | Cognitive disability | [16] |

| 13 | 67/F | dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, nystagmus, painful paresthesia, CD, arms rigidly extended | abnormal liver function | Xanthochromic, protein ↑ | Bil. Th, brainstem, cerebellum | NA | NA | Expired | [15] |

Abbreviations: F: female; M: male; CD: disturbance of consciousness; LR: pupillary light reflex; DTR: deep tendon reflex; BS: Babinski sign; VOR: vestibulo-ocular reflex; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulation; CRP: C-reactive protein; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; CPK: creatine phosphokinase; Cr: creatinine; Bil.: bilateral; Th: thalami; BT: brainstem tegmentum; CWM: cerebral white matter; CM: cerebellar medulla; NA: not available; T1(+): T1-weighted image post gadolinium enhancement; DWI: Diffusion-weighted images; SWI: Susceptibility weighted images; Anti-viral: Anti-viral agent; PT: steroid pulse therapy; PP: plasmapheresis; IVIG: Intravenous immunoglobulin.

Results

Report a case

A 30-year-old female patient was admitted with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-related nasal cavity extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma. She began to develop a spiking fever (up to 40 °C), cough, sore throat, and rhinorrhea following a 3rd round of chemotherapy with a CHOP regimen (Cyclophosphamide 100 mg + Doxorubicin 60 mg + Vincristine 2 mg + Prednisone 1 mg/kg/day). Shortly afterwards, she experienced episodic generalized tonic-convulsive seizures followed by loss of consciousness within 24 h. Physical examination showed reduced consciousness, increased sweating, decerebrate posture, absence of pupillary light reflexes, decreased deep tendon reflex, and bilateral Babinski signs. Hemogram and biochemical studies showed leukopenia (3000/μL), and elevated C-reactive protein (CRP, 71.28 mg/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, 106 U/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT, 43 U/L), and procalcitonin (48.64 ng/mL). The blood levels of glucose, ammonia, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, renal function, electrolytes, and thyroid function were within normal limits. Blood autoimmune markers, anti-glycolipids, and paraneoplastic anti-neuronal antibodies were all negative. CSF analysis showed high protein levels (133.5 mg/dL) and IgG index (1.18) without the presence of leukocytes. Her blood EBV genome copy number increased from 331 copies/mL to 779 copies/mL over the course of two months. IgG and IgM to EBV-viral-capsid antigen and IgG to EBV-early antigen were absent in the CSF. Infectious studies for herpes simplex virus, human immunodeficiency virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, cytomegalovirus, and influenza virus A and B were negative. The repeated CSF cytology (2 sessions) were negative for malignancies.

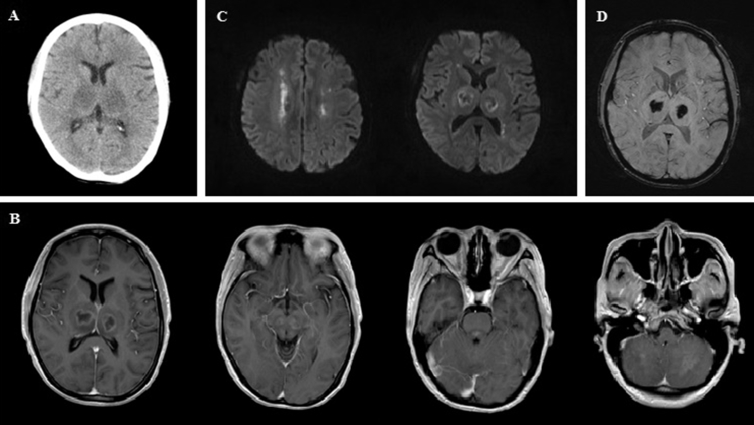

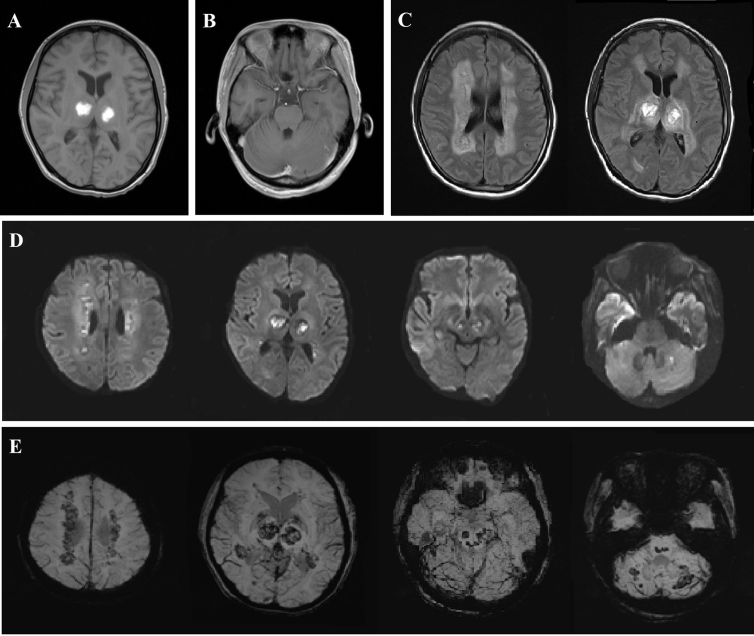

Initial brain computed topography (CT) in the emergency department showed bilateral low-density thalamic lesions [Fig. 1A]. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), performed 12 h after disease onset, found bilateral thalamic lesions with hypointensities and ring-like contrast enhancement on T1-weighted (T1W) images [Fig. 1B]. In addition, similar contrast-enhanced lesions were also noted in the midbrain, pontine tegmentum, and cerebellum [Fig. 1B]. Water restrictions were detected in the bilateral periventricular white matter and thalami in diffusion-weighted images (DWIs, [Fig. 1C]). Susceptibility weighted images (SWIs) showed bleeding in both thalami [Fig. 1D]. Follow-up brain MRI on day 11 of disease onset revealed bilateral thalamic hyperintensity on T1W images that suggested subacute hemorrhages in the necrotic region [Fig. 2A]. Compared with the 1st MRI, contrast-enhanced lesions over the brainstem tegmentum and cerebellum were no longer apparent [Fig. 2B]. T2-weighted (T2W) images with a fluid attenuation inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence and DWI showed prominent hyperintensities over the periventricular white matter, thalami, midbrain, pontine tegmentum, and subcortical white matter of the cerebellum bilaterally [Fig. 2C–D]. These lesions were identified as microbleeds on the SWIs [Fig. 2E].

Fig. 1.

The initial brain CT (A) and brain MRI performed 12 h after disease onset (B, C, D). (A) CT revealed low-density lesions over the bilateral thalami. (B) MRI found bilateral thalamic hypointensities with ring enhancement and hyperintensities in the midbrain, pontine tegmentum, and cerebellum on T1-weighted images with gadolinium enhancement. (C) Water restrictions were detected on bilateral periventricular white matter and thalamus in diffusion-weighted images. (D) Significant bleeding over the bilateral thalami on susceptibility weighted images.

Fig. 2.

Brain MRI on day 11 of disease onset. (A) Bilateral thalamic hyperintensity on T1-weighted images suggest subacute hemorrhagic change in the central necrotic region. (B) Previous gadolinium enhanced lesions over the brainstem tegmentum and cerebellum are no longer apparent. (C) and (D) T2 FLAIR series and diffusion-weighted images showed progressive hyperintensities over the periventricular white matter, thalami, midbrain, pontine tegmentum, and subcortical white matter of the cerebellum bilaterally. (E) These lesions were identified as microbleeds on susceptibility-weighted images.

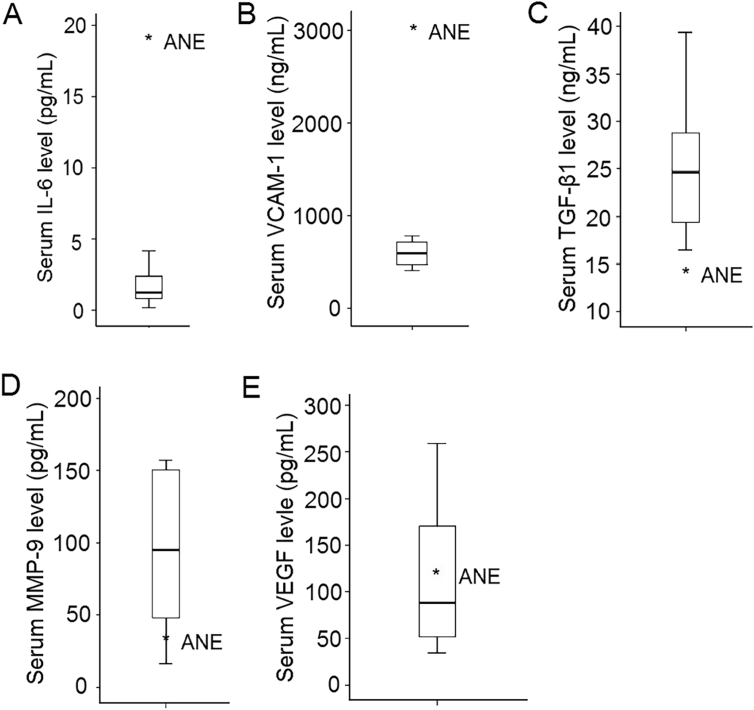

Levels of cytokines checked one day after disease onset were shown in [Fig. 3]. As shown in [Fig. 3A–B], serum levels of IL-6 (17.17 pg/mL; healthy controls: 1.43 ± 1.22 pg/mL) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) (3033.92 ng/mL; healthy controls: 589.71 ± 133.13 ng/mL) in this patient were elevated compared with sex- and age-matched controls. Serum level of TGF-β1 (14.78 ng/mL, healthy controls: 25.81 ± 6.97 ng/mL) was lower than that of control group [Fig. 3C]. Serum levels of MMP-9 (40.31 pg/mL; healthy controls: 90.61 ± 54.39 pg/mL) and VEGF (126.36 pg/mL; healthy controls: 113.58 ± 74.52 pg/mL) were similar to the control group [Fig. 3D–E].

Fig. 3.

Serum levels of five common microglia-mediated cytokines. Higher serum levels of IL-6 (A) and VCAM-1 (B) were seen in this adult case of ANE compared with control group. Serum level of TGF-β1 (C) was lower, whereas MMP-9 (D), and VEGF (E) were similar to that of the control group.

Empiric antimicrobial treatment, including vancomycin, cefepime, and metronidazole, as well as acyclovir, were given immediately at admission. Because she had neutropenia, we did not prescribe steroid until 2 weeks later. Methylprednisolone pulse therapy (1 g/day) was started on day 15 of admission for a total course of 5 days. Since there was little improvement in consciousness and clinical condition, two courses of plasmapheresis with five fractions in each were given from day 20–30 and day 37–46. Oral prednisolone (1 mg/kg/day) was initiated on day 20, and was gradually tapered down until stopping treatment on day 46 because of sepsis. The patient died 3 months later because of septic shock.

Literature review and integration

Demographic presentation

As shown in [Table 1], in thirteen ANE cases (nine females and four males), the median age of onset was 30 years. Eleven cases were patients of Asian origin, and most of whom were Japanese (eight cases).

Clinical manifestations

All these thirteen patients had disturbance of consciousness and ten of them (77%) had fever. Seven cases (54%) got influenza virus infections or developed flu-like symptoms before change in consciousness. Influenza A and B virus infections were confirmed in four (31%) and one (8%) patient, respectively. Three (23%) cases had symptoms of gastrointestinal tract infection. Cranial nerves palsy were noted in 7 patients (54%), while decerebrate or decorticate postures were noted in 5 patients (38%). Pathological changes of deep tendon reflexes and Babinski's sign were observed in 5 patients (38%).

Laboratory features

Elevated liver enzymes, such as AST, ALT, or lactate dehydrogenase, were reported in 11 of the 13 cases (85%). Thrombocytopenia and/or coagulopathy were also noted in four patients (31%). All 11 patients who received a lumbar puncture demonstrated high protein levels in the CSF. Only two patients (22%) had pleocytosis [11], [19].

Cytokine levels in the serum and/or CSF were checked in four cases [11], [12], [19]. All cases showed elevation of IL-6 in the serum or CSF. In addition, elevated serum levels of IL-10 [19] and VCAM-1 (our case), and elevated CSF levels of IL-1β [11], were observed.

Brain MRIs performed in 11 cases showed the characteristic findings of lesions bilaterally in the thalami (100%), brainstem and/or brainstem tegmentum (62%), cerebral white matter (39%), and cerebellum and/or cerebellar medulla (31%). T2W/FLAIR images and DWIs revealed hyperintensities all over these lesions. Bleeding was detected on SWI or gradient echo (31%).

The results of biopsies in two patients showed symmetric, edematous, and necrotizing lesions over the basal ganglia (including the thalami) and cerebral white matter [12], as well as the midbrain [16]. Edematous lesions were also seen in the cerebral deep white matter, cerebellar dentate nuclei, and dorsolateral tegmentum of the brainstem [16]. Perivascular necrosis with hemorrhages was noted [12], [16]. Notably, lymphocytic or neutrophilic infiltrates were absent [12].

Treatment and outcome

Anti-viral agents (62%), antimicrobials (31%), high dose steroid (38%), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) (23%), steroid (8%), and plasmapheresis (8%) were used in the treatment of patients with adult ANE. Five patients (39%) died, and three patients (23%) had little or no clinical improvement. Among the five patients with improvement, only one patient completely recovered following treatment. Neurological sequelae persisted in the other four surviving patients. In 11 patients that literature had mentioned about treatment, 6 of them received immune therapy such as high dose steroid, IVIG, or plasmapheresis. Patients with immune therapy (2 patients died, 1 patient had little improvement, and 3 patient had neurological sequelae) displayed similar outcome to those who did not (2 patients died, 1 patient had little improvement, 1 patient had persisted neurological sequelae, and 1 patient had total recovery).

Discussion

We presented an adult case of ANE, a 31-year-old female, whose clinical features, laboratory data, and neuroimages fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of ANE suggested by Mizuguchi M [3]. Other differential diagnoses, such as lymphoma with central nervous system (CNS) involvement, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), and viral encephalitis were not likely. Central nervous system involvement of lymphoma developed in weeks to months [21], [22], [23], but the clinical deterioration of this case was full blown within days. Although elevated serum levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines have been reported in patients with NK/T cell lymphoma [24], repeated cranial CT and MRI further excluded the recurrence of NK/T cell lymphoma. Moreover, negative results of repeated CSF cytology excluded the potential leptomeningeal involvement of lymphoma. However, CHOP treatment may increase the release of IL-6 and contribute to the development of ANE [25]. MRIs of brain in ADEM demonstrate asymmetrical cortical and subcortical lesions [26], [27], whereas the neuroimaging studies of this patient showed symmetrical thalamic and subcortical lesions characteristic of ANE. Cerebrospinal fluid surveys of viral encephalitis including EBV, herpes simplex virus, Japanese encephalitis virus, and cytomegalovirus, were negative. Although we did not get the consent to obtain brain tissues for pathological confirmation, the diagnosis of ANE is still well-established.

In the literature review, we demonstrated that adult patients with ANE and pediatric ANE had similar clinical presentations, laboratory data, and imaging findings. Both groups of the patients commonly present with antecedent viral infection, fever, disturbance of consciousness, decerebrate or decorticate posture, cranial nerve involvement, and pathologic reflexes. Influenza A infection is the most common infection detected in patients with ANE [2]. Biochemical tests usually reveal elevated liver enzymes, while thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy are occasionally observed in hemograms. High protein levels without pleocytosis are typically observed in the CSF. Bilateral thalamic lesions in CT or MRI exist in all patients with ANE. Other regions, including the brainstem, cerebellum, and cerebral white matter, are also involved [2].

However, adult patients with ANE had distinct sex distribution and prognosis from pediatric ones. Pediatric ANE affects boys and girls equally [22], whereas ANE in adults appears to be more prevalent in females than in males (female/male = 2.25). In children, the mortality rate of ANE is approximately 25%, while 60% (33% of all patients) of survivors recover without significant neurological sequelae [2]. In adults, the mortality rate of ANE is approximately 40% and most survivors have significant neurological sequelae. Although the number of adult cases was too small to interpret the data powerfully, we saw the trend that ANE in adult patients struck females more than males and had worse prognosis.

Poor prognosis in adult patients has also been observed in other CNS inflammatory diseases. In acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), complete motor recovery was frequently seen in pediatric patients compared with adults [23]. The median time to reach an Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score of 4 was approximately 10 years longer in pediatric than in adult patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) [26]. Neuromyelitis optica (NMO) in children typically has a monophasic course and many have complete neurological recovery [27], [28], whereas adult NMO frequently occurs as a polyphasic illness that is either fulminant and fatal, or associated with varying degrees of recovery [29]. These features suggest distinct immunological responses and neural repair potentials between pediatric and adult CNS inflammatory diseases.

Our cytokine assays further indicate the potential role of IL-6 and VCAM-1 in the pathogenesis of ANE in adults. Elevation of IL-6 has been previously reported in the serum and CSF of adult [11], [12], [19] and pediatric patients with ANE [3], [4], [30], [31], as well as in other inflammatory and autoimmune diseases such as MS, systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic sclerosis [32]. IL-6 plays a role in the differentiation of B, Th2, and Th17 cells [32], [33]. Overexpression of IL-6 in mouse astrocytes leads to extensive breakdown of the blood–brain barrier and neuroinflammation [34]. Further studies to assess the level of IL-6 in CSF and brain will provide more supports to the role of IL-6 in ANE.

VCAM-1, one of the adhesion molecules, mediates endothelial function by activation and adhesion of leukocytes [35]. High serum levels of VCAM-1, for the first time, were found in our patient with ANE. Compared with the levels in patients with MS and other non-inflammatory neurological diseases, the CSF levels of VCAM-1 are elevated in patients with NMO [36]. In the rat brain, VCAM-1 co-localizes with the apoptotic marker active caspase-3, indicating the association of VCAM-1 with neuronal apoptosis [37]. VCAM-1 is upregulated by many cytokines such as IL-1β and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [35], [38]. It has been shown that the levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were also elevated in the serum of pediatric patients with ANE [3], [5]. Further studies to assess the levels of IL-1β and TNF-α in blood and CSF will elucidate the regulation of VCAM-1 in adult ANE. In experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) murine model, selective knockout of TGF-β1 in B cells exhibits increased neuroinflammation and demyelination [39]. Administration of TGF-β1 prevented the occurrence of relapses in EAE mice [40]. The finding of low serum TGF-β1 level in our patient further suggests a possible role for TGF-β in the regulation and treatment of ANE.

Conclusions

This adult patient with ANE showed high serum levels of IL-6 and VCAM-1, and low serum TGF-β1 level. Although these findings are similar to those in pediatric ANE, these cytokine deregulations still provide important information on precision medicine targeting relevant pathways in adult ANE. More systemic surveys of cytokine profiles will be important to elucidate the differences between adult and pediatric ANE. Our literature study demonstrates that adult and pediatric ANE share the similar clinical symptoms, biochemical data, and CT/MRI findings, whereas adult ANE tends to have female preponderance and relatively poor prognosis compared to pediatric ANE. These findings advance our understanding of this rare neuroinflammatory disease in adult patients.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed under a protocol approved by the institutional review boards of Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgement

This study was sponsored by Chang Gung Medical Foundation (CMRPG 3C1631-33). The funders had no role design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chang Gung University.

References

- 1.Mizuguchi M., Abe J., Mikkaichi K., Noma S., Yoshida K., Yamanaka T. Acute necrotising encephalopathy of childhood: a new syndrome presenting with multifocal, symmetric brain lesions. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:555–561. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.5.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizuguchi M. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood: a novel form of acute encephalopathy prevalent in Japan and Taiwan. Brain Dev. 1997;19:81–92. doi: 10.1016/s0387-7604(96)00063-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akiyoshi K., Hamada Y., Yamada H., Kojo M., Izumi T. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy associated with hemophagocytic syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34:315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kubo T., Sato K., Kobayashi D., Motegi A., Kobayashi O., Takeshita S. A case of HHV-6 associated acute necrotizing encephalopathy with increase of CD56bright NKcells. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38:1122–1125. doi: 10.1080/00365540600740520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kansagra S.M., Gallentine W.B. Cytokine storm of acute necrotizing encephalopathy. Pediatr Neurol. 2011;45:400–402. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim J.H., Kim I.O., Lim M.K., Park M.S., Choi C.G., Kim H.W. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in Korean infants and children: imaging findings and diverse clinical outcome. Korean J Radiol. 2004;5:171–177. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2004.5.3.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee Y.B., Nagai A., Kim S.U. Cytokines, chemokines, and cytokine receptors in human microglia. J Neurosci Res. 2002;69:94–103. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang K.H., Wu Y.R., Chen Y.C., Chen C.M. Plasma inflammatory biomarkers for Huntington's disease patients and mouse model. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;44:121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mizuta R., Izumi H., Takeuchi S. A case of Reye's syndrome with elevation of influenza A CF antibody. Shonika Rinsho. 1979;32:2144–2149. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasano A., Natoli G.F., Cianfoni A., Ferraro D., Loria G., Bentivoglio A.R. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy: a relapsing case in a European adult. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:227–228. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.127670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iijima H., Wakasugi K., Ayabe M., Shoji H., Abe T. A case of adult influenza A virus-associated encephalitis: magnetic resonance imaging findings. J Neuroimaging. 2002;12:273–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishii N., Mochizuki H., Moriguchi-Goto S., Shintaku M., Asada Y., Taniguchi A. An autopsy case of elderly-onset acute necrotizing encephalopathy secondary to influenza. J Neurol Sci. 2015;354:129–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2015.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato H., Hasegawa H., Iijima M., Uchigata M., Terada T., Okada Y. Brain magnetic resonance imaging of an adult case of acute necrotizing encephalopathy. J Neurol. 2007;254:1135–1137. doi: 10.1007/s00415-006-0476-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y.J., Smith D.S., Rao V.A., Siegel R.D., Kosek J., Glaser C.A. Fatal H1N1-related acute necrotizing encephalopathy in an adult. Case Rep Crit Care. 2011;2011:562516. doi: 10.1155/2011/562516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyata E. An adult case of acute necrotizing encephalopathy. No Shinkei. 2002;54:354–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizuguchi M., Tomonaga M., Fukusato T., Asano M. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy with widespread edematous lesions of symmetrical distribution. Acta Neuropathol. 1989;78:108–111. doi: 10.1007/BF00687411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakamura Y., Miura K., Yamada I., Ino H., Mizobata T. A novel adult case of acute necrotizing encephalopathy of childhood with bilateral symmetric thalamic lesions. Rinsho Shinkeigaku. 2000;40:827–831. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narra R., Mandapalli A., Kamaraju S.K. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy in an adult. J Clin Imag Sci. 2015;5:20. doi: 10.4103/2156-7514.156117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saji N., Yamamoto N., Yoda J., Tadano M., Yamasaki H., Shimizu H. Adult case of acute encephalopathy associated with bilateral thalamic lesions and peripheral neuropathy. No Shinkei. 2006;58:1009–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirai T., Fujii H., Ono M., Watanabe R., Shirota Y., Saito S. A novel autoantibody against ephrin type B receptor 2 in acute necrotizing encephalopathy. J Neuroinflammation. 2013;10:128. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-10-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ventura E., Summa A., Ormitti F., Picetti E., Crisi G. Influenza a H1N1 related acute necrotizing encephalopathy: radiological findings in adulthood. NeuroRadiol J. 2012;25:397–401. doi: 10.1177/197140091202500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mizuguchi M. Acute encephalopathy with necrosis of bilateral tha- lami: clinical aspects. Neuropathology. 1993;13:327–331. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ketelslegers I.A., Visser I.E., Neuteboom R.F., Boon M., Catsman-Berrevoets C.E., Hintzen R.Q. Disease course and outcome of acute disseminated encephalomyelitis is more severe in adults than in children. Mult Scler. 2011;17:441–448. doi: 10.1177/1352458510390068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cai Q., Huang H.Q., Bai B., Yan G., Li J., Lin S. The serum spectrum of cytokines in patients with NK/T-Cell lymphoma and its cilincial significance in survival. Blood. 2013;122:1759. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheung Y.T., Ng T., Shwe M., Ho H.K., Foo K.M., Cham M.T. Association of proinflammatory cytokines and chemotherapy-associated cognitive impairment in breast cancer patients: a multi-centered, prospective, cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1446–1451. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simone I.L., Carrara D., Tortorella C., Liguori M., Lepore V., Pellegrini F. Course and prognosis in early-onset MS: comparison with adult-onset forms. Neurology. 2002;59:1922–1928. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000036907.37650.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chia W.C., Wang J.N., Lai M.C. Neuromyelitis optica: a case report. Pediatr Neonatol. 2010;51:347–352. doi: 10.1016/S1875-9572(10)60067-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jeffery A.R., Buncic J.R. Pediatric Devic's neuromyelitis optica. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1996;33:223–229. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19960901-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wingerchuk D.M., Weinshenker B.G. Neuromyelitis optica: clinical predictors of a relapsing course and survival. Neurology. 2003;60:848–853. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000049912.02954.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ichiyama T., Endo S., Kaneko M., Isumi H., Matsubara T., Furukawa S. Serum cytokine concentrations of influenza-associated acute necrotizing encephalopathy. Pediatr Int. 2003;45:734–736. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200x.2003.01822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ito Y., Ichiyama T., Kimura H., Shibata M., Ishiwada N., Kuroki H. Detection of influenza virus RNA by reverse transcription-PCR and proinflammatory cytokines in influenza-virus-associated encephalopathy. J Med Virol. 1999;58:420–425. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9071(199908)58:4<420::aid-jmv16>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yao X., Huang J., Zhong H., Shen N., Faggioni R., Fung M. Targeting interleukin-6 in inflammatory autoimmune diseases and cancers. Pharmacol Ther. 2014;141:125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jego G., Palucka A.K., Blanck J.P., Chalouni C., Pascual V., Banchereau J. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells induce plasma cell differentiation through type I interferon and interleukin 6. Immunity. 2003;19:225–234. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brett F.M., Mizisin A.P., Powell H.C., Campbell I.L. Evolution of neuropathologic abnormalities associated with blood-brain barrier breakdown in transgenic mice expressing interleukin-6 in astrocytes. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:766–775. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199511000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burne M.J., Elghandour A., Haq M., Saba S.R., Norman J., Condon T. IL-1 and TNF independent pathways mediate ICAM-1/VCAM-1 up-regulation in ischemia reperfusion injury. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;70:192–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uzawa A., Mori M., Masuda S., Kuwabara S. Markedly elevated soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1, soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 levels, and blood-brain barrier breakdown in neuromyelitis optica. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:913–917. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang D., Yuan D., Shen J., Yan Y., Gong C., Gu J. Up-regulation of VCAM1 relates to neuronal apoptosis after intracerebral hemorrhage in adult rats. Neurochem Res. 2015;40:1042–1052. doi: 10.1007/s11064-015-1561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zonneveld R., Martinelli R., Shapiro N.I., Kuijpers T.W., Plotz F.B., Carman C.V. Soluble adhesion molecules as markers for sepsis and the potential pathophysiological discrepancy in neonates, children and adults. Crit Care. 2014;18:204. doi: 10.1186/cc13733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bjarnadottir K., Benkhoucha M., Merkler D., Weber M.S., Payne N.L., Bernard C.C. B cell-derived transforming growth factor-beta1 expression limits the induction phase of autoimmune neuroinflammation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:34594. doi: 10.1038/srep34594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuruvilla A.P., Shah R., Hochwald G.M., Liggitt H.D., Palladino M.A., Thorbecke G.J. Protective effect of transforming growth factor beta 1 on experimental autoimmune diseases in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:2918–2921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.7.2918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]