Abstract

Background

Respirator fit testing is a method to assess if the respirator provides an adequate face seal for the worker.

Methods

Workers from four Norwegian smelters were invited to participate in the study, and 701 respirator fit tests were performed on 127 workers. Fourteen respirator models were included: one FFABE1P3 and 11 FFP3 respirator models produced in one size and two silicone half masks with P3 filters available in three sizes. The workers performed a quantitative fit test according to Health and Safety Executive 282/28 with 5–6 different respirator models, and they rated the respirators based on comfort. Predictors of overall fit factors were explored.

Results

The pass rate for all fit tests was 62%, 56% for women, and 63% for men. The silicone respirators had the highest percentage of passed tests (92–100%). The pass rate for the FFP3 models varied from 19–89%, whereas the FFABE1P3 respirator had a pass rate of 36%. Five workers did not pass with any respirators, and 14 passed with all the respirators tested. Only 63% passed the test with the respirator they normally used. The mean comfort score on the scale from 1 to 5 was 3.2. The respirator model was the strongest predictor of the overall fit factor. The other predictors (age, sex, and comfort score) did not improve the fit of the model.

Conclusion

There were large differences in how well the different respirator models fitted the Norwegian smelter workers. The results can be useful when choosing which respirators to include in respirator fit testing programs in similar populations.

Keywords: Fit factor, Predictors of fit, Respiratory protective equipment, Quantitative respirator fit test, Smelting industry

1. Introduction

The smelting industry has been, and still is, an important area of employment in Norway. In 2016, Norway was the world's third largest producer of ferrosilicon and the second largest producer of silicon and silicon carbide [1]. In the production process, dust, fumes, and gases are released into the work environment, and depending on the type of production, they may contain potentially harmful components such as quartz, cristobalite, amorphous silica, heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and ultrafine particles [2], [3], [4], [5]. Earlier studies have shown an accelerated decreased lung function and increased risk of respiratory diseases among workers in the Norwegian smelting industry [6], [7], [8], [9], [10]. Although the exposure levels in Norwegian smelters have declined owing to technical and organizational measures, they are still too high in some areas, thereby requiring mandatory use of respirators. It is important to ensure that the respirators used are suitable and provide the workers with the protection they expect. Respirator fit testing is a method of ensuring that the respirator fits the face of the worker, that is, that the respirator provides an adequate face seal. There are several fit test methods available, and respirator fit testing using a specialized condensation particle counter Portacount Pro (TSI inc, Shoreview, MN, USA) is commonly used. This instrument measures the ratio of ambient aerosols outside and inside the respirator, while the wearer performs exercises according to a defined protocol. The various protocols have different criteria for passing the test and slightly different exercises. The Health and Safety Executive (HSE) protocol in the UK specifies that to pass the test, the respirator needs to achieve a fit factor (FF) of 100 or more for a half-face respirator in each exercise, whereas the Occupational Safety and Health Administration in the USA states that to pass the test, only the overall FF needs to be ≥ 100 [11], [12]. A FF of 100 means that the concentration of particles inside the respirator is less than 1/100 of the concentration outside the respirator. In some countries, such as the UK and USA, it is compulsory for workers who are required to use tight-fitting respirators to perform a fit test [11], [12]. In most parts of Europe, including Norway, fit testing is not compulsory and is seldom performed. However, in the Norwegian regulation for personal protective equipment, several requirements are mentioned, for example, that the employer shall ensure that the personal protective equipment fits or can be fitted to the employee [13]. In the Norwegian smelting industry, only a few plants had performed respirator fit testing on their employees before the present study. The respirators used by the workers in the smelting industry were predominantly various models of FFP3 respirators that were all produced by international companies.

Several studies have been published on respirator fit testing, but most of the published studies on respirator fit testing have been performed on volunteers or health-care workers using N95 respirators [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. It is important to ensure that the respirators fit the worker population that is dependent on using them to be protected from airborne exposure. To our knowledge, no studies have been published on respirator fit testing of FFP3 respirators and half masks on workers in the smelting industry. The objectives of this study was therefore to assess if the respirator models that were used by the Norwegian smelting industry fit the workers, to assess how well different respirator models fit the workers, and to evaluate predictors of the overall FF. The study is part of the DeMaskUs project that aims to improve the working environment in the Norwegian ferroalloy, silicon, and silicon carbide plants by studying how airborne dust is formed, how it affects human cells, and how workers can protect themselves from airborne dust in the working environment.

2. Materials and methods

Full-time employees and apprentices at four different plants (Plant 1–4) were invited to participate in the study. One plant was located in southern Norway, two in mid-Norway, and one in northern Norway. The plants were one ferrosilicon producer, one silicon carbide producer, and two silicon producers. The two silicon producers belonged to the same company; the two other plants belonged to two different companies. The participation was voluntary. To be included, the workers had to perform at least five fit tests and refrain from smoking one hour before the test and male workers had to be freshly shaved (≤12 hours since shaving). Gender and age were noted for each worker, in addition to information on which respirator he/she normally used. The workers had not earlier participated in respirator fit testing.

Fourteen cup-shaped half-mask respirator models with P3 filters from seven different producers were included in the study. Ten of the respirator models (Respirator A–G, I, J, and L) were included based on a survey among the participating smelters that asked which respirators their employees used. Additional four respirator models (Respirator H, K, M, and N) were included. Two of the respirator models were silicone masks with replaceable filters. The others were filtering facepiece respirators. For specifications of the respirators, see Table 1. The workers performed the fit test with five or six different respirators and were offered to perform the test with the respirators they normally used if those were not included among the test respirators for that plant. If the respirators were available in several sizes, the workers were offered to don all three sizes before choosing the size to perform the test with.

Table 1.

Description of the different half-mask respirator models used in the study

| Respirator | Manufacturer | Model | Respirator and filter type | Size∗ | Adjustable nose clip | Adjustable headbands | Exhalation valve | Plant† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3M | 8835 | FF‡ P3§ R‖ | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1, 2, and 3 |

| B | 3M | 9332+ | FF‡ P3§ NR¶ | 1 | Yes | No | Yes | 1, 2, and 3 |

| C | Zekler | 1303V | FF‡ P3§ NR¶ | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1 and 2 |

| D | 3M | 9936 | FF‡ P3§ R‖ | 1 | Yes | No | Yes | 1 |

| E | 3M | 8833 | FF‡ P3§ R‖ | 1 | Yes | No | Yes | 1, 2, and 3 |

| F | 3M | 4277 | FF‡ ABE1#P3§ R§ | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 1 and 4 |

| G | 3M | 7500 | Half mask∗∗ P3§ | 3 | No | Yes | Yes | 1, 2, and 4 |

| H | Sundström | SR100 | Half mask∗∗ P3§ | 3 | No | Yes | Yes | 1 and 2 |

| I | Moldex | 3405 | FF‡ P3§ R‖ | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 2, 3, and 4 |

| J | 3M | 8835+ | FF‡ P3§ R‖ | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| K | Alpha | S–3V | FF‡ P3§ NR¶ | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 3 and 4 |

| L | MSA | Affinity 1131 | FF‡ P3§ NR¶ | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 3 and 4 |

| M | UVEX | Silv-air 2312 | FF‡ P3§ NR¶ | 1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | 4 |

| N | UVEX | ECO 7313 | FF‡ P3§ R‖ | 1 | No | Yes | Yes | 3 |

FF, fit factor; NR, nonreusable; R, reusable.

How many different sizes the respirator was available in.

The plants that the respirator was tested in.

Filtering facepiece respirator, that is, the respirator entirely or substantially constructed of filtering material.

Particle Filter Class 3 according to EN149:2001.

Reusable.

Nonreusable (single shift use only).

Gas Filter Class A1B1E1.

Half mask made of silicone with changeable filters.

The quantitative fit test was performed according to HSE 282/28 with the Portacount Pro model 8038 (TSI inc) [11]. The pass criterion for half masks was as specified in HSE 282/28, that is, a total FF ≥ 100 and an FF ≥ 100 for each of the seven exercises (normal breathing, deep breathing, turning the head side to side, moving the head up and down, talking, bending over, and normal breathing) [11]. The main fit test operator had attended fit test operator training in quantitative fit testing using the TSI Portacount given by Respiratory Protective Assessment Ltd. (Bristol, England). The main fit test operator trained the other operators.

Four different Portacounts Pro model 8038 were used in fit testing. The Portacounts were calibrated annually, and functionality tests were performed daily before fit testing. The fit testing was performed at room temperature in meeting rooms at the plants. Normally, two Portacounts were used at the same time, with one operator for each Portacount performing the fit test on one worker each. The particle generator 8026 (TSI inc), which produces NaCl aerosols, and candles were used to create sufficient particle concentration in the room if needed. The reason for performing the fit test and how the fit test is performed was first explained to the worker, and he/she filled out a short form including information about gender, age, and which respirator was normally used. The order the respirators were fit tested was constantly changed to avoid the same respirator always being the first or last to be tested on a person. The fit test instructors explained how to don the current respirator correctly. The workers then performed the fit test while walking on a treadmill wearing a helmet and protective glasses in addition to the respirator. These are mandatory protective equipment at the plants that could affect the fit of the respirator. Without knowing the result of the test, the worker was asked to give the respirator a comfort score on a scale from 1 to 5, where 5 was the top score, based on how comfortable it was to wear. The worker was also asked if he/she had any comments about the respirator. During the fit test, the ambient and mask particle concentration was noted for each exercise. Each worker performed five or six fit tests in a row with different respirator models.

2.1. Statistical analysis

Using cumulative probability plots, the overall FF data were found to be best described by log-normal distribution and were loge transformed before statistical analysis. To evaluate predictors of the overall FF, linear mixed effect models were constructed using mixed models. The mixed effect models were constructed using the overall FF as the dependent variable. The worker was treated as a random effect, and the respirator model, age, sex, and the comfort score were treated as fixed effects. The model was adjusted with the mean ambient particle level. The restricted maximum likelihood algorithm was used to estimate variance components owing to the unbalanced nature of the data. Univariate models were first performed after which multivariate models were built stepwise starting with the variable with the lowest p-value in the univariate models. The Akaike information criterion was used to select the optimal combination of predictors in the multivariate model.

IBM SPSS statistics version 24.0 for Windows (IBM Corp., New York, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

3. Results

A total of 127 workers participated in the study, 112 male and 15 female workers, and they performed 701 fit tests. The arithmetic mean (AM) age was 37 years, and the range was 18–65 years for all workers and for male workers. For female workers, the AM age was 35 years, with the range of 20–53 years.

The pass rate for the 701 tests that were performed was 62%, see Table 2. The female workers had a pass rate of 56%, whereas the male workers had a pass rate of 63%. Respirators G and H had the highest pass rate of 92% and 100 %, respectively, and the highest overall FFs. These were the only silicone respirators with changeable filters included in the study and the only respirators that were available in different sizes. The pass rate among the FFP3 respirators varied from 19% (Respirator C) to 80% (Respirator A). Both of these respirators had an adjustable headband and adjustable nose clip, see Table 1, which indicates that the presence of these features does not ensure a good fit. Some of the fit test protocols have a pass criterion based only on the total FF and not on the individual FF for the different exercises. A total of 78% of the fit test performed had a total FF≥100 and would have passed if the total FF alone was to be taken into account. Respirator F had by far the largest difference in the percentage of passed tests (36%) compared with the percentage of tests with the total FF ≥ 100 (84%). The mean difference for all respirators was 16 percentage points. The silicone respirators had the smallest difference with no difference for Respirator H, that has a 100% pass rate, and a difference of 4 percentage points for Respirator G. For the respirators that did not pass the test, 31% failed on all exercises, whereas 27% only failed on one exercise. The AM of the number of passed exercises for respirators that did not pass the test was 3.1. The exercise that failed most often was talking (26%), followed by moving the head up and down (23%) and bending over (22%). The rest of the exercises had a fail rate between 19–20%.

Table 2.

Summary of the test results from the fit tests for the different respirator models

| Respirator | Number of tests | Used as the main respirator (%) | FF ≥ 100∗ (%) | Passed† (%) | Comfort score‡ (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 83 | 24 | 89 | 80 | 3.6 (1.1) |

| B | 98 | 50 | 70 | 45 | 3.3 (1.3) |

| C | 76 | 0 | 36 | 19 | 2.5 (1.3) |

| D | 24 | 0 | 96 | 87 | 3.3 (1.1) |

| E | 73 | 16 | 88 | 77 | 3.3 (1.0) |

| F | 25 | 3.9 | 84 | 36 | 3.3 (1.1) |

| G | 78 | 0 | 96 | 92 | 3.3 (1.2) |

| H | 27 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 4.2 (0.80) |

| I | 47 | 0.7 | 53 | 30 | 2.6 (1.1) |

| J | 21 | 1.4 | 90 | 62 | 3.3 (1.2) |

| K | 49 | 0 | 84 | 76 | 3.4 (1.0) |

| L | 50 | 0 | 90 | 72 | 3.6 (1.0) |

| M | 21 | 0 | 71 | 48 | 3.1 (0.99) |

| N | 29 | 0 | 69 | 52 | 2.0 (0.89) |

| Total | 701 | 96 | 78 | 62 | 3.2 (1.2) |

FF, fit factor; SD, standard deviation.

Percentage of workers with an overall fit factor (FF) ≥100.

The criterion to pass the test was an FF ≥ 100 on all the individual exercises.

The comfort score was from 1 to 5.

A total of 96% of the workers passed the test with at least one of the respirators. On average, the workers passed the test with 62% of the respirators tested. Fourteen workers passed the test with all the respirators tested. Five workers did not pass the test with any of the respirators tested; however, four of them achieved a total FF ≥ 100 for at least one of the respirators. Four of the five workers did not perform the test with the silicone respirators (Respirators G and H), but only with FFP3 respirators. A total of 109 persons performed the test with the respirator they normally used. Of these, 63% passed the test with that respirator and 37 % failed. Respirator B was the one that was mostly used, and 61 persons had this as the respirator they normally used, but only 49% of these passed the test. Respirator A was used by 21 persons; of whom, 86% passed the test. Respirator E was used by 19 persons; of whom, 84% passed the test. The other respirator models were used by five persons or less.

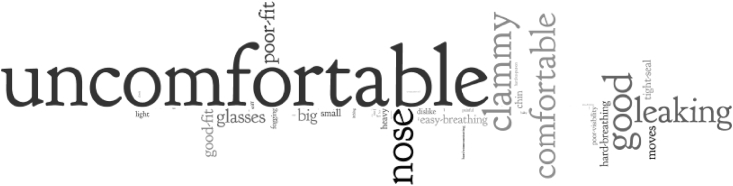

The workers were asked to score the respirators on a scale from 1 to 5 based on how comfortable they were. The mean score for all respirators was 3.2 (Table 2). However, the range in scores was from 1 to 5 for all respirators except H, M, and N. Respirator H did not get the lowest score [1], and Respirators M and N did not receive the highest score [5]. The highest mean score of 4.2 was given to Respirator H, which was also the respirator achieving the highest pass rate. Respirator N got the lowest mean score of 2.0, followed by Respirator C with a score of 2.5. The mean score on the respirator they normally used was 3.9, that is, higher than the average, but the range was 1–5. The most common comment about the respirator was that it was uncomfortable to wear, see Fig. 1. The facial area that was often said to be problematic was the nose, either that it leaked here or that it was uncomfortable and/or painful on the nose. Other common comments were that it felt clammy, did not fit well, and felt like it was leaking. Fortunately, some of the comments were positive such that it was comfortable to wear and felt good.

Fig. 1.

Word cloud of the comments given by the workers using the respirators when giving the comfort scores. The area taken by each word is proportional to the number of respondents giving that word as a comment. The words included in the word cloud are in alphabetical order: allergic, best, big, breaks, bulky, chin, clammy, comfortable, dislike, easy breathing, elastics, face, fogging, glasses, good, good fit, good visibility, hard breathing, hard communicating, hard talking, hard to put on, hearing protection, heavy, heavy breathing, helmet, hot, itching, leaking, light, moves, neck, nose, not good, ok, painful, poor elastic, poor fit, poor visibility, small, soft, stiff, tight seal, unaccustomed, and uncomfortable.

3.1. Mixed effects

The respirator model was the main predictor of the overall FF, explaining 50% of the variance. The other predictors (age, gender, and the comfort score) explained less than 9% of the variance in the univariate models. Adding other predictors to the model that included the type of respirator did not improve the fit of the model. The final model is presented in Table 3. Respirators G and H had by far the highest geometric mean ratios of the overall FF, followed by Respirator A. The lowest geometric mean ratios were for Respirators C, I, and N.

Table 3.

Estimates of the overall fit factors for the different respirators from the mixed effect regression models

| Parameter∗ | GMR† |

|---|---|

| Respirator A | 9.71 |

| Respirator B | 1.05 |

| Respirator C | 0.43 |

| Respirator D | 5.09 |

| Respirator E | 4.59 |

| Respirator F | 1.59 |

| Respirator G | 44.7 |

| Respirator H | 28.1 |

| Respirator I | 0.85 |

| Respirator J | 2.40 |

| Respirator K | 5.94 |

| Respirator L | 2.65 |

| Respirator M | 1.58 |

| Respirator N | 1.00 |

| Background level‡ | 127 |

The background level is given as the overall fit factor, and the parameter effects, as geometric mean ratios (GMRs)∗. The model was adjusted for the ambient particle level.

Example calculation: total fit factor for Respirator A: background level * Respirator A GMR = 127 * 9.71 = 1233.

The exponential function of the regression coefficient (exp(β)).

The covariates that were found to give the best fit of the model.

The fit factor estimate for covariates that did not show up as predictors in the models.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the fit of different models of half-mask respirators on workers in the Norwegian smelting industry using a quantitative respirator fit test. Each worker performed the fit test with at least five different respirators. Altogether, 701 fit tests were performed on 112 male and 15 female workers in the Norwegian smelting industry, including 14 different respirator models.

There are a large number of respirator models available on the market. It was important for us to include respirators that were in use at the Norwegian smelters, and therefore, the 10 respirator models that the Norwegian smelters reported using were included. This is the reason why several respirator models from one manufacturer were included. To add respirators from various manufacturers, four respirator models that were not already in use in the smelters were also included. From prior experience with respirator fit testing on female workers, it was known that it is often difficult to find respirators that fit them. Respirator K was therefore included as it was specified that it was specially made for small faces. Respirator N was also included as it was a new concept with a frame with replaceable filters that we found interesting to test.

The fit test passing rate differed a great deal between the different respirator models, with four models having a pass rate of 80% or more and two having a pass rate of 30% or less although all of the them were certified according to the European Standard EN 143:2000 [20]. A varying pass rate between respirator models has also been shown in several other studies [15], [16], [17], [19], [21], [22], [23], [24], [25]. When it comes to respirators, it is clear that one model or one size does not fit all. The two silicone respirators models that performed best during the fit test and had by far the highest FFs of all the respirators included were available in three sizes, whereas FFABE1P3 and FFP3 respirators were produced in one size only. One of the FFP3 respirator models, Respirator K, the manufacturer specified that it was made for small faces. It had a high pass rate of 76%, being the 5th highest pass rate of the respirators, indicating that although the manufacturer specified that it was made for small faces, it fits other face sizes as well. The percentage of passed tests for the different respirators can be useful information when planning which respirators to include in respirator fit testing campaigns on a similar worker population. Lee et al. [21] screened different respirator models on a selection of 40 health-care workers and only included the two models that performed best in the screening for further fit testing. This approach resulted in a pass rate of 99.6% for the 1850 health-care workers tested with the two retained models. Minimizing the number of different respirator models that are necessary to include in the fit testing program is time efficient. In addition, with fewer models to choose from, it is more easy for the workers to remember which respirator they passed the test with, minimizing worker confusion about which respirator to wear. Shaffer and Janssen [25] conducted a literature study and concluded that although there does not appear to be a single best-fitting filtering facepiece respirator, studies demonstrate that fit testing programs can be designed to successfully fit nearly all workers with existing products. Five of the smelter workers did not pass the fit test with any of the five or six respirators with which they performed the test, although four of them had a total FF ≥ 100. However, they were fit tested with a random selection of respirators. Had the test only included the top respirators in the present study, they would probably have had a better chance of finding one with which to pass the test. Owing to time constraints, it was not possible to offer these workers a further fit test within the present study; however, the participating plants offered them further fit testing later.

Most of the workers in this study performed the fit test with the respirator they normally used. Of these, 63% passed the test and 82% had a total FF ≥ 100. This is a higher pass rate than that reported in a recent study on workers in diagnostic laboratories in South Africa using different N95 and FFP2 respirator models, where only 22% had a total FF ≥ 100 with the respirator normally used [18]. Some of the difference in the pass rate is probably due to the different populations in the two studies. A total of 88% of the smelter workers in the present study were men. Ethnicity was not registered among the smelter workers; however, the workers were mainly of Caucasian origin. The two percent of the South African laboratory workers who were male Caucasians had the highest pass rate (35%); the lowest pass rate was for women of Asian origin (4%). It is important to have in mind when performing fit tests that facial dimensions vary according to gender and ethnicity, and the results of this study cannot necessarily be compared with other populations comprising other genders and ethnic compositions [18], [19]. It is worrying that only 63% of the workers passed the test with the respirator they normally used. Using a respirator that does not fit properly will lead to exposure through contaminated air getting into the respirator through leaks between the face and the respirator. It can also give a false sense of protection if the workers are not aware that the respirator has a poor fit. The results support the necessity of a respirator fit test to ensure that workers use a respirator that fits their face.

The workers were asked to rate the respirators based on comfort on a scale from 1 to 5. The respirator with the highest pass rate received the highest mean comfort score (Respirator H). Lee et al. [21] also found that the respirator with the highest pass rate achieved the highest comfort score and that comfort rates varied in proportions to fit test pass rates. In a questionnaire survey in a general hospital in Canada, health-care workers were asked to rate the item The N95 respirator is comfortable (Likert scale 0–5). The mean response was 3.2 with a standard deviation of 1.2, comparable with the score in the present study [26]. The mean comfort score for the respirator the smelter workers normally used was higher than the mean comfort score for all respirators tested (3.9 versus 3.2). This indicated that the workers were more inclined to use a respirator that felt comfortable or possibly that the respirator they were familiar with felt more comfortable than a respirator put on for the first time and which they were not used to adjusting. The range of the comfort score for the respirator they normally used was 1–5, which implied that the choice of the respirator was not only a result of picking the most comfortable respirator. Possibly, the range of respirator models to choose from was limited; in some cases, only one model was easily available at the plants. Respirator B was the most commonly used. The workers reported that they used Respirator B as it was easily available, very handy as it could be stored in the helmet when not in use, and comfortable to wear. This was the only respirator model that was foldable and individually packed in plastic. At several plants, this respirator was the most easily available as it was the only respirator model located in boxes that were placed in several places at the plant. Hence, distribution logistics and convenience seemed to be of importance in regard to how the users evaluated the respirator.

Comfort is important for respirator users as they are more prone to wear a respirator that feels comfortable and to wear it over longer periods. In a recent questionnaire survey among the Norwegian smelter workers, only 30% reported that they always used a respirator when they were in exposed areas, and an important reason for not wearing the respirator was that it was uncomfortable to wear [27]. The respirator that received the lowest comfort score (Respirator N, comfort score: 2.0) had a fabric headband and a reusable plastic frame to which the filter that constituted the respirator was attached, allowing the filter to be changed while keeping the reusable plastic frame. The main reason for the low comfort score on this respirator was that the plastic frame felt tight and was not flexible, especially over the nose. Respirator C was also given a low comfort score (2.5), and many of the workers complained that the material used for the face seal was itchy. Itchiness was not reported for any of the other respirator models that were tested. Most of the respirator models were scored across the full range of the scale from 1 to 5, emphasizing that the feel of comfort is subjective and based on the individual experience. Nevertheless, respirator producers are encouraged to consider these findings and eliminate materials that might itch and feel uncomfortable, for example.

Several methods are used to perform fit tests, both qualitative, where the taste, smell, or irritating effect of a substance is used to evaluate the fit of the respirator, or quantitative tests, where either particles are counted or pressure fall is measured. The qualitative methods rely on the wearer's subjective response to a challenge agent. The subjective response might vary from person to person, and there is also a chance of cheating. A recent study comparing qualitative and quantitative fit test methods on N95 respirator models concluded that quantitative methods should be used as they were more capable of detecting failures [17]. It was decided to use a quantitative method with particle counting as the method is not subject to individual differences and is easy to perform, and it is an acknowledged method.

The criterion to pass the test in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration protocol is a total FF ≥ 100, whereas the HSE 282/28 has a stricter passing criterion, specifying that each exercise needs to obtain a FF ≥ 100 [11], [12]. There are also slight differences in the exercises performed during the fit test. The choice of pass criteria influences the pass rate, and in the present study, the pass rate was 62% according to the HSE protocol but would have been 78% if only the total FF was to be taken into account. This is quite a large difference in the pass rate, and using the criterion of a FF ≥ 100 on all exercises instead of only the total FF adds an extra safety factor.

4.1. Predictors of fit

The predictors of fit were explored, and the strongest predictor was the respirator model. The other predictors, age, gender, and the comfort score, explained only a small proportion of the variance. No facial measurements were included in the present study. Face size and nose bridge width was found to be the strongest predictors of fit for laboratory workers in addition to the respirator model; however, facial dimensions only explained 16.3% (women only) and 8.9% (both sexes) of the passing and failing of fit tests [18]. Other studies have found a correlation with other facial measurements and the passing of some respirator models.

Facial hair and stubs have been reported to negatively influence the fit of respirators [28], [29]. To avoid the presence of stubs and facial hair influencing the fit of the respirator in the present study, only workers who were cleanly shaved were included. The workers were informed why it is important to be cleanly shaved when using tight-fitting respirators. Workers who choose to have a beard owing to personal, cultural, or religious reasons are recommended to use loose-fitting respiratory protecting equipment with compressed or filtered air supply.

Because the respirator fit testing was performed in meeting rooms at the plants and not in an exposure chamber with full control over the ambient particle concentration, the ambient particle concentration varied. However, it was always within the specifications for the instrument. The FF is the particle concentration inside the respirator divided by the ambient particle concentration. The ambient particle level can therefore, in theory, influence the FF. To account for this, the model was adjusted by including the ambient particle level. However, adding the ambient particle concentration to the model only increased the explained variance from 49% to 50% and resulted in only minor changes in the model output (results not shown). This indicated that the varying ambient particle concentrations in the office environment did not affect the main results. The overall FF was significantly higher for Respirators G and H compared with FFP3 respirators. This is reasonable as these were the respirators with the highest pass rate. However, the FF ranking of the respirators were different from the pass rate ranking, indicating that some respirator models form a really tight seal when they fit the person, whereas others only form an adequate seal for passing the test, but particles still leak into the respirator.

4.2. Conclusion

There was a large difference in how well different respirator models fitted the workers in the Norwegian smelter industry. Some respirator models fitted a large proportion of the workers, whereas others fitted only a few individuals. The silicone respirators that came in different sizes fitted more workers than FFP3 respirators. The current results can be useful when choosing which respirator models to include in a respirator fit program on similar worker populations. The respirator model was the strongest predictor of fit and explained 50% of the variance. Before the study, one-third of the Norwegian smelter workers in this study used respirators that did not have an adequate fit. Hence, they were provided with a false sense of security regarding the protection they got from the respirator. After performing fit testing with 5–6 different respirator models, 96% of the workers found a respirator that passed the fit test. It is hoped that by only including the best-performing respirator models in the fit test program, the number of workers passing the fit test after performing it with 5–6 respirators would be higher.

Acknowledgments

The authors highly appreciated the cooperation with Elkem Solar, Elkem Thamshavn, Washington Mills AS, and Finnfjord AS. This project could not have been accomplished without the positive attitude and the valuable and necessary contribution from the workers performing the fit testing. The authors would also like to thank Erlend Hassel, Liv Bjerke Rodal, Lena Brødreskift, and Siri Fenstad Ragde for assistance during the fit testing. The study was funded by the Norwegian Research Council, the Norwegian Ferroalloy Producers Research Association, Washington Mills AS, and Saint-Gobain through the project DeMaskUs (grant no: 245216).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2019.06.004.

Conflict of interest

The study was partially financed by the participating plants.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.U.S. Geological Survey . U.S. Geological Survey; 2017. Mineral commodity summaries 2017. 202p. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Føreland S., Bye E., Bakke B., Eduard W. Exposure to fibres, crystalline silica, silicon carbide and sulphur dioxide in the Norwegian silicon carbide industry. Ann Occup Hyg. 2008;52(5):317–336. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/men029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kero I.T., Jorgensen R.B. Comparison of three real-time measurement methods for airborne ultrafine particles in the silicon alloy industry. Int J Environ Res PublicHealth. 2016;13(9) doi: 10.3390/ijerph13090871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnsen H.L., Hetland S.M., Saltyte Benth J., Kongerud J., Soyseth V. Quantitative and qualitative assessment of exposure among employees in Norwegian smelters. Ann Occup Hyg. 2008;52(7):623–633. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/men046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kero I., Grådahl S., Trannell G. Airborne emissions from Si/FeSi production. JOM. 2017;69(2):365–380. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnsen H.L., Soyseth V., Hetland S.M., Benth J.S., Kongerud J. Production of silicon alloys is associated with respiratory symptoms among employees in Norwegian smelters. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81(4):451–459. doi: 10.1007/s00420-007-0237-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soyseth V., Johnsen H.L., Kongerud J. Respiratory hazards of metal smelting. Curr OpinPulm Med. 2013;19(2):158–162. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835ceeae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnsen H.L., Bugge M.D., Føreland S., Kjuus H., Kongerud J., Søyseth V. Dust exposure is associated with increased lung function loss among workers in the Norwegian silicon carbide industry. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70(11):803–809. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2012-101068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bugge M.D., Føreland S., Kjærheim K., Eduard W., Martinsen J.I., Kjuus H. Mortality from non-malignant respiratory diseases among workers in the Norwegian silicon carbide industry: associations with dust exposure. Occup Environ Med. 2011 doi: 10.1136/oem.2010.062836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bugge M.D., Kjærheim K., Føreland S., Eduard W., Kjuus H. Lung cancer incidence among Norwegian silicon carbide industry workers: associations with particulate exposure factors. Occup Environ Med. 2012 doi: 10.1136/oemed-2011-100623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.HSE . 2012. OC 282/28Fit testing of respiratory protective equipment facepieces. [Google Scholar]

- 12.OSHA . 2011. 29 CFR 1910.134 - respiratory protection. Washington DC. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Regulations concerning organisation, management and employee participation. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee S.A., Grinshpun S.A., Reponen T. Respiratory performance offered by N95 respirators and surgical masks: human subject evaluation with NaCl aerosol representing bacterial and viral particle size range. Ann Occup Hyg. 2008;52(3):177–185. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/men005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reponen T., Lee S.A., Grinshpun S.A., Johnson E., McKay R. Effect of fit testing on the protection offered by n95 filtering facepiece respirators against fine particles in a laboratory setting. Ann Occup Hyg. 2011;55(3):264–271. doi: 10.1093/annhyg/meq085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffey C.C., Lawrence R.B., Campbell D.L., Zhuang Z., Calvert C.A., Jensen P.A. Fitting characteristics of eighteen N95 filtering-facepiece respirators. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1(4):262–271. doi: 10.1080/15459620490433799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hon C.Y., Danyluk Q., Bryce E., Janssen B., Neudorf M., Yassi A. Comparison of qualitative and quantitative fit-testing results for three commonly used respirators in the healthcare sector. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2017;14(3):175–179. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2016.1237030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manganyi J., Wilson K.S., Rees D. Quantitative respirator fit, face sizes, and determinants of fit in South African diagnostic laboratory respirator users. Ann Work Expo Health. 2017;61(9):1154–1162. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxx077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu Y., Jiang L., Zhuang Z., Liu Y., Wang X., Liu J. Fitting characteristics of N95 filtering-facepiece respirators used widely in China. PLoS One. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EN 143:2000. Respiratory protective devices - particle filters - requirements, testing, marking - 2000. (Corrigendum AC:2002 and AC:2005 incorporated) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee K., Slavcev A., Nicas M. Respiratory protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis: quantitative fit test outcomes for five type N95 filtering-facepiece respirators. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2004;1(1):22–28. doi: 10.1080/15459620490250026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawrence R.B., Duling M.G., Calvert C.A., Coffey C.C. Comparison of performance of three different types of respiratory protection devices. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2006;3(9):465–474. doi: 10.1080/15459620600829211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S.A., Hwang D.C., Li H.Y., Tsai C.F., Chen C.W., Chen J.K. Particle size-selective assessment of protection of European standard FFP respirators and surgical masks against particles-tested with human subjects. J Healthc Eng. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/8572493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhuang Z., Coffey C.C., Ann R.B. The effect of subject characteristics and respirator features on respirator fit. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2005;2(12):641–649. doi: 10.1080/15459620500391668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shaffer R.E., Janssen L.L. Selecting models for a respiratory protection program: what can we learn from the scientific literature? Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bryce E., Forrester L., Scharf S., Eshghpour M. What do healthcare workers think? A survey of facial protection equipment user preferences. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68(3):241–247. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hegseth M.N., Robertsen Ø., Aminoff A., Vangberg H.C.B., Føreland S., editors. INFACON XV: international ferro-alloys congress. 2018. Reasons for not using respiratory protective equipment and suggested measures to optimize use in the Norwegian silicon carbide, ferro-alloy and silicon-alloy industry. [Cape Town, South Africa] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Floyd E.L., Henry J.B., Johnson D.L. Influence of facial hair length, coarseness, and areal density on seal leakage of a tight-fitting half-face respirator. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2018;15(4):334–340. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2017.1416388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frost S., Harding A.H. 2015. The effect of wearer stubble on the protection given by Filtering Facepieces Class 3 (FFPA) and Half Masks. Contract No.: RR1052. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.