The crystal structure of aminoglycoside 7′′-phosphotransferase-Ia from Streptomyces hygroscopicus in complex with hygromycin B has been determined at 2.4 Å resolution.

Keywords: aminoglycoside antibiotics, enzyme-mediated resistance, kinases, SAD phasing, selenomethionine, hygromycin B, Streptomyces hygroscopicus

Abstract

Hygromycin B (HygB) is one of the aminoglycoside antibiotics, and it is widely used as a reagent in molecular-biology experiments. Two kinases are known to inactivate HygB through phosphorylation: aminoglycoside 7′′-phosphotransferase-Ia [APH(7′′)-Ia] from Streptomyces hygroscopicus and aminoglycoside 4-phosphotransferase-Ia [APH(4)-Ia] from Escherichia coli. They phosphorylate the hydroxyl groups at positions 7′′ and 4 of the HygB molecule, respectively. Previously, the crystal structure of APH(4)-Ia was reported as a ternary complex with HygB and 5′-adenylyl-β,γ-imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP). To investigate the differences in the substrate-recognition mechanism between APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, the crystal structure of APH(7′′)-Ia complexed with HygB is reported. The overall structure of APH(7′′)-Ia is similar to those of other aminoglycoside phosphotransferases, including APH(4)-Ia, and consists of an N-terminal lobe (N-lobe) and a C-terminal lobe (C-lobe). The latter also comprises a core and a helical domain. Accordingly, the APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia structures fit globally when the structures are superposed at three catalytically important conserved residues, His, Asp and Asn, in the Brenner motif, which is conserved in aminoglycoside phosphotransferases as well as in eukaryotic protein kinases. On the other hand, the phosphorylated hydroxyl groups of HygB in both structures come close to the Asp residue, and the HygB molecules in each structure lie in opposite directions. These molecules were held by the helical domain in the C-lobe, which exhibited structural differences between the two kinases. Furthermore, based on the crystal structures of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, some mutated residues in their thermostable mutants reported previously were located at the same positions in the two enzymes.

1. Introduction

Aminoglycoside antibiotics target 16S rRNA (Woodcock et al., 1991 ▸; Fourmy et al., 1996 ▸), resulting in the mistranslation of mRNA and the blocking of tRNA translocation (Borovinskaya et al., 2008 ▸; Wilson, 2014 ▸). Aminoglycoside antibiotics have been used with cell-wall-active agents such as penicillin antibiotics to provide a synergistic effect (Murray, 1990 ▸). However, bacteria evolve to acquire drug resistance by the methylation of 16S rRNA (Wachino & Arakawa, 2012 ▸) or the modification of antibiotics. Aminoglycoside antibiotics are modified by acetyltransferases (AACs), adenyltransferases (ANTs) and phosphotransferases (APHs) (Ramirez & Tolmasky, 2010 ▸). These aminoglycosidase-modifying enzymes (AMEs) cause dysfunction of antibiotics by preventing their binding to 16S rRNA in the ribosome, resulting in the survival of pathogenic bacteria. Furthermore, some AMEs have been found to be bifunctional enzymes. For example, AAC(6′)-Ie/APH(2′′)-Ia exhibits both acetyltransferase and phosphotransferase activities using different domains (Ferretti et al., 1986 ▸; Boehr et al., 2004 ▸).

Aminoglycoside phosphotransferases (APHs) catalyze the transfer of a phosphate group from ATP to the specific position of a hydroxyl group in antibiotic molecules. APH(2′′) and APH(3′) target kanamycin, APH(4)-Ia and APH(7′′)-Ia target hygromyin B (HygB), APH(6) targets streptomycin and APH(9)-Ia targets spectinomycin (Ramirez & Tolmasky, 2010 ▸). Some APHs can use either GTP alone or both ATP/GTP as the phosphate-group donor, such as APH(2′′)-Ia and APH(2′′)-IVa, respectively (Toth et al., 2009 ▸). The APH family, represented by serine/threonine and tyrosine protein kinases in eukaryotes, contains Brenner’s motif (HxDxxxxN; Brenner, 1978 ▸) as a conserved catalytic motif. The Asp residue in the motif transfers the phosphate group (Madhusudan et al., 1994 ▸; Cole et al., 1995 ▸; Hon et al., 1997 ▸; Iino et al., 2013 ▸). To investigate their substrate-recognition mechanisms and to exploit drug design, crystal structures of APHs have been determined. The overall structures of APHs are similar to those of eukaryotic protein kinases (ePKs; Hon et al., 1997 ▸), which are mainly composed of two lobes: an N-lobe for ATP binding and a C-lobe for substrate binding. Accordingly, several ePK inhibitors inhibit APHs in vitro (Daigle et al., 1997 ▸; Fong et al., 2011 ▸).

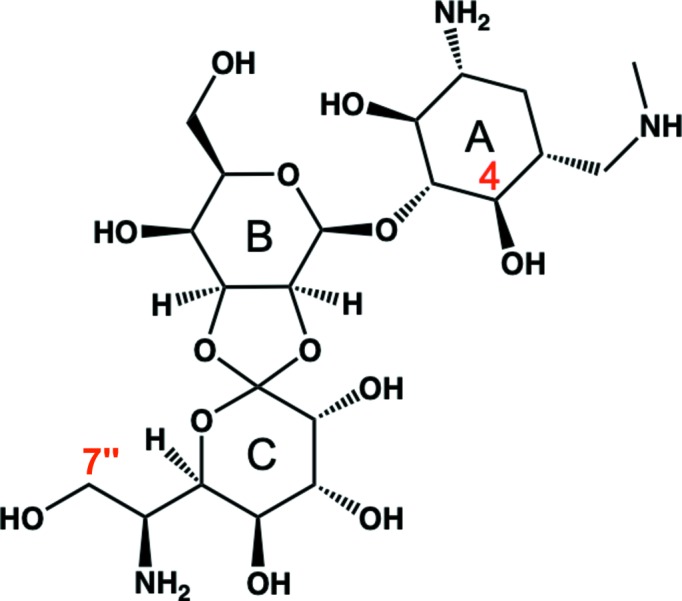

Among those phosphotransferases, APH(4)-Ia and APH(7′′)-Ia target the same substrate, hygromycin B (HygB; Rao et al., 1983 ▸; Pardo et al., 1985 ▸), which is one of the aminoglycoside antibiotics synthesized by Streptomyces hygroscopicus (Pittenger et al., 1953 ▸). HygB consists of three rings, a hyosamine ring, a d-talose ring and a destomic acid ring (Fig. 1 ▸), and it is active against both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. It is not currently used for clinical purposes, but it is widely used as a tool in the cloning of genes for both prokaryotes and eukaryotes in molecular-biology experiments (Addgene; http://www.addgene.org). To elucidate the inactivation mechanism of HygB, the crystal structure of APH(4)-Ia from Escherichia coli in a ternary complex with HygB and 5′-adenylyl-β,γ-imidodiphosphate (AMP-PNP) has been reported (Stogios et al., 2011 ▸; Iino et al., 2013 ▸). In this structure, the hydroxyl O atom at position 4 in the hyosamine ring was located between Asp198 in Brenner’s motif and the γ-phosphate of AMP-PNP. Since APH(4)-Ia and APH(7′′)-Ia show low homology in amino-acid sequence, we determined the crystal structure of APH(7′′)-Ia to elucidate the mechanism of phosphorylation of HygB at a different position to APH(4)-Ia. Furthermore, a thermostable mutant of APH(7′′)-Ia has been obtained which exhibited a 13°C higher optimum temperature than that of the wild type (Sugimoto et al., 2013 ▸). Therefore, the crystal structure is also attractive to elucidate the thermostabilization mechanism of the mutant enzyme.

Figure 1.

Structure of hygromycin B. The hyosamine, d-talose and destomic acid rings are denoted A, B and C, respectively. The hydroxyl groups at positions 4 and 7′′ (labelled in red) are phosphorylated by APH(4)-Ia and APH(7′′)-Ia, respectively.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cloning, expression and purification of APH(7′′)-Ia

The gene encoding APH(7′′)-Ia (EC 2.7.1.119) from S. hygroscopicus had been cloned into pET-21a(+) vector (Novagen) with a C-terminal 6×His tag as reported previously (Sugimoto et al., 2013 ▸). The expression plasmid for APH(7′′)-Ia was transformed into the E. coli B834(DE3) strain to introduce selenomethionine (SeMet) into the enzyme.

E. coli cells harboring the expression plasmid were cultured in LeMaster medium containing 50 µg ml−1 ampicillin and 34 µg ml−1 chloramphenicol at 37°C. Thiamine hydrochloride was used as a vitamin solution. Antifoam (Sigma–Aldrich) and 200 µM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) were added for induction of the target protein when the OD600 reached 0.6–0.8. After 16 h of culture, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4648g for 15 min at 4°C.

The cells were resuspended in buffer [20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 20 mM imidazole, 200 mM NaCl, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] and homogenized by ultrasonication. The supernatant was separated by centrifugation at 69 673g for 40 min followed by purification using a nickel agarose column (Qiagen). The elution fraction was dialyzed with a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 10% glycerol. An anion-exchange Mono Q column (GE Healthcare) was used for gradient elution with a buffer consisting of 50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 10% glycerol, 500 mM KCl. The purified protein was concentrated to 25 mg ml−1 by ultrafiltration at 4°C at 4000g.

2.2. Crystallization

Crystallizations were performed by the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method at 20°C. Protein solution consisting of 2.5 mM MgCl2 (Wako), 10 mM hygromycin B (Wako) and 5 mM AMP-PNP (Sigma–Aldrich) and reservoir solution were mixed in a 1:1 ratio. After optimization of the reservoir conditions, crystals grew to dimensions of 0.3 × 0.3 × 0.2 mm in a week using a reservoir solution consisting of 0.1 M 2-(cyclohexylamino)ethanesulfonic acid (CHES) pH 8.8, 1.38–1.40 M sodium citrate tribasic. Dithiothreitol or β-mercaptoethanol were not added to the reservoir solution to avoid the oxidation of Se atoms as they prevented the formation of crystals. We also prepared crystals of native APH(7′′)-Ia protein and tried to collect diffraction data; however, only data sets with lower resolution than that of the SeMet-derivative crystals were obtained.

2.3. Data collection and structure determination

Crystals were flash-cooled in liquid N2 in nylon loops without cryoprotectant solution. The diffraction data were collected on beamline BL-17A equipped with a PILATUS3 S6M detector at the Photon Factory (PF). Since the crystals diffracted poorly and produced weak anomalous diffraction, we repeated the data-set collection. A single crystal was used to solve the phase and for model refinement. To increase the resolution, the data were collected with a large redundancy. Indexing, integration, scaling and merging were carried out using the XDS package (Kabsch, 2010 ▸). The Se-SAD phasing and automated initial model building of APH(7′′)-Ia were performed using CRANK2 (Skubák & Pannu, 2013 ▸) in the CCP4 suite (Winn et al., 2011 ▸). Iterative refinement and model building were carried out using PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸) and Coot (Emsley et al., 2010 ▸), respectively. In a Ramachandran plot produced by RAMPAGE (Lovell et al., 2003 ▸) in the CCP4 suite for the final model, 97.1%, 2.9% and 0% of the residues were in the preferred, allowed and outlier regions, respectively. Data-collection and refinement statistics are presented in Table 1 ▸.

Table 1. Data-collection and refinement statistics for APH(7′′)-Ia.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Beamline | BL-17A, PF |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97934 |

| Space group | P23 |

| Unit-cell parameters (Å) | a = b = c = 151.6 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 50.0–2.4 (2.46–2.40) |

| Completeness (%) | 100 (100) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 31.2 (1.1) |

| Multiplicity | 62.7 (64.6) |

| R merge † (%) | 13.2 (459.5) |

| No. of unique reflections | 88021 (6572) |

| CC1/2 (%) | 100 (49.5) |

| Significant anomalous correlation‡ (%) | 47 [15 at 2.98 Å] |

| Mean anomalous difference§ | 1.475 [3.39 Å] |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution range (Å) | 47.9–2.4 (2.45–2.40) |

| No. of reflections | 45592 |

| R/R free ¶ (%) | 22.5/25.1 |

| R.m.s.d. from ideality | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.725 |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 5137 |

| Solvent | 21 |

| Ligand (hygromycin B) | 72 |

| Ligand (CHES) | 26 |

| Ligand (citrate) | 26 |

| Average B factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 103.3 |

| Solvent | 68.2 |

| Ligand (hygromycin B) | 114.2 |

| Ligand (CHES) | 134.6 |

| Ligand (citrate) | 66.2 |

| Ramachandran plot†† (%) | |

| Favored | 97.1 |

| Allowed | 2.9 |

| Outliers | 0 |

R

merge =

, where I

i(hkl) is the ith measurement of reflection hkl.

, where I

i(hkl) is the ith measurement of reflection hkl.

Percentage of correlation between intensities from random half data sets calculated by XSCALE. Correlation significant at the 0.1% level was limited to 2.98 Å resolution and the corresponding value is presented.

Mean anomalous difference as reported as SigAno in XSCALE. Since SHELXD used anomalous data at 3.36 Å resolution, the value for the closest resolution shell in XSCALE is presented in brackets.

A subset of the data (5%) was excluded from refinement and was used to calculate R free.

The Ramachandran plot was calculated by RAMPAGE in the CCP4 suite.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Overall structure

To gain an understanding of the phosphorylation mechanism of the hydroxyl group at position 7′′ of hygromycin B (HygB) compared with position 4, the crystal structure of APH(7′′)-Ia was solved for the first time. A selenomethionine-substituted crystal was obtained as molecular-replacement trials failed despite the similarity of the overall structures of APHs; this was probably because of the differing conformation of the C-lobes, as described in Section 3.3. The crystal of APH(7′′)-Ia belonged to space group P23 and the crystal structure was determined at 2.4 Å resolution. SHELXD in CRANK2 used the anomalous reflections above 3.36 Å resolution, found all six Se sites except for the methionines at the N-termini and automatically built 660 residues in six chains including 30 unknown residues (UNK) out of the 664 residues in the asymmetric unit. The values of FOM were 0.304 and 0.568 prior to and after density modification, respectively. The final model comprised two molecules in the asymmetric unit [Fig. 2 ▸(a)] and comprised residues 3–327 in chain A and 4–327 in chain B out of 332 residues, according to the resolved electron density. The overall structure of APH(7′′)-Ia was similar to known APH structures, including the reported binary (Stogios et al., 2011 ▸) and ternary (Iino et al., 2013 ▸) complexes of APH(4)-Ia, as well as those of ePKs. APH(7′′)-Ia is composed of an N-lobe consisting of a five-stranded antiparallel β-sheet, which is sandwiched by two α-helices, and a C-lobe consisting of ten α-helices with five β-strands, which comprise two sets of antiparallel β-sheets. The C-lobe consists of a core domain, which includes Brenner’s motif, and a helical domain [Fig. 2 ▸(a)]. Chains A and B of the APH(7′′)-Ia crystal structure in the asymmetric unit were superposed using LSQKAB (Kabsch, 1976 ▸) in the CCP4 suite; the root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d.) value was 1.75 Å for the Cα atoms of residues 4–327. Differences were mainly observed in the N-lobe, which is known to be a nucleotide-binding lobe. When chains A and B were compared by the superposition of either residues 13–124 (the N-lobe) or 125–326 (the C-lobe) on Cα atoms, the r.m.s.d. values for the regions were 2.34 and 0.29 Å [Fig. 2 ▸(b)], respectively. This structural difference between the two chains may be caused by the crystal packing.

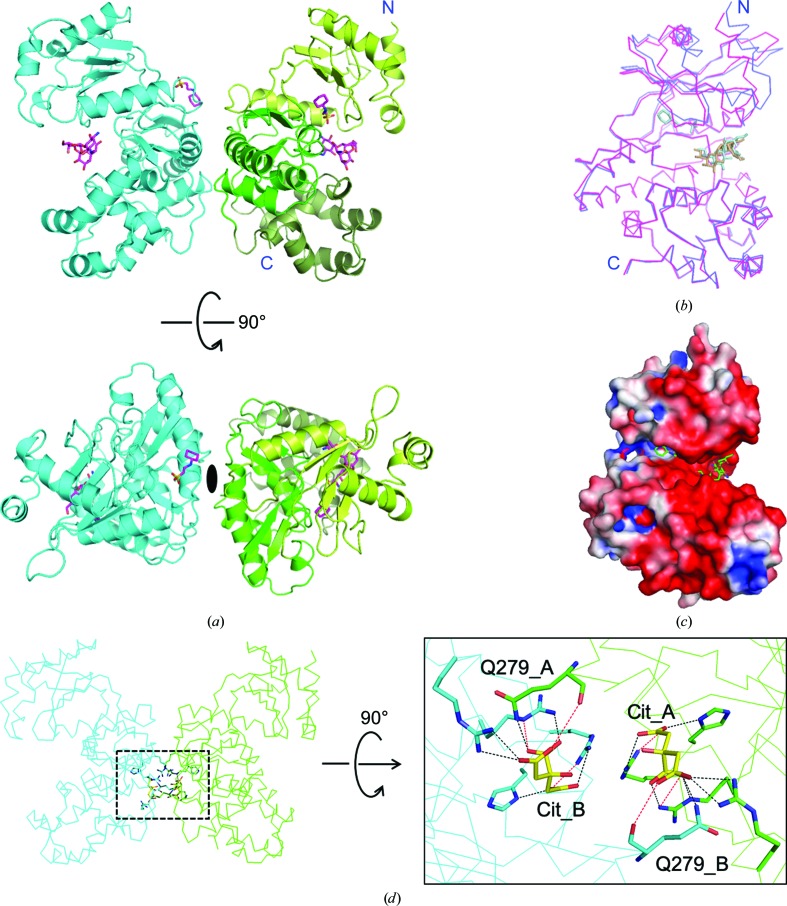

Figure 2.

Overall structure of APH(7′′)-Ia. (a) The crystal structure of APH(7′′)-Ia in the asymmetric unit is shown as a cartoon model. One chain is colored cyan and the other is colored light green, green and dark green corresponding to the N-lobe and the core and helical domains in the C-lobe, respectively. HygB and CHES are shown as stick models. The bottom view shows dyad symmetry between the two chains. (b) Chains A and B were superposed by LSQKAB on Cα atoms in the C-lobe (residues 125–327). Chains A and B are colored magenta and blue, respectively. N and C denote the N- and C-termini, respectively, and HygB and CHES are also shown as stick models. (c) The electrostatic surface potential was calculated by APBS (Baker et al., 2001 ▸) in PyMOL (Jurrus et al., 2018 ▸) and mapped onto the subunit surface. (d) The interactions between the two chains are through the citrate ions. The dotted rectangle in the left panel was enlarged and rotated 90° in the right panel. Chains A and B are colored green and cyan, respectively. Citrate ions are denoted Cit and are colored yellow. The dotted lines in the right panel represent hydrogen bonds, where black and red lines indicate distances of below 3 Å and between 3 and 3.5 Å, respectively. All figures except for Figs. 1 ▸ and 5 ▸ were prepared by PyMOL (Schrödinger).

The electrostatic surface potential of APH(7′′)-Ia was calculated and observed to be same as in other APHs, in which the binding site of HygB in the core domain was negatively charged [Fig. 2 ▸(c)] (Stogios et al., 2011 ▸), which complements aminoglycosides with amines on the sugar rings (Nurizzo et al., 2003 ▸); however, APH(9)-Ia is an exception as it does not possess such a negatively charged area for antibiotic binding.

In the crystal structure that we obtained, two citrate ions originating from the crystallization buffer were observed between the chains in the asymmetric unit. As shown in Fig. 2 ▸(d), the Gln279 residues in each chain formed hydrogen bonds to the citrate ion in the other chain. Therefore, these ions contribute to the formation of a dimer of APH(7′′)-Ia in the asymmetric unit. On the other hand, in solution the ions may not be fixed in these positions; therefore, APH(7′′)-Ia is likely to exist as a monomer. PISA (Krissinel & Henrick, 2007 ▸) also produced the same result.

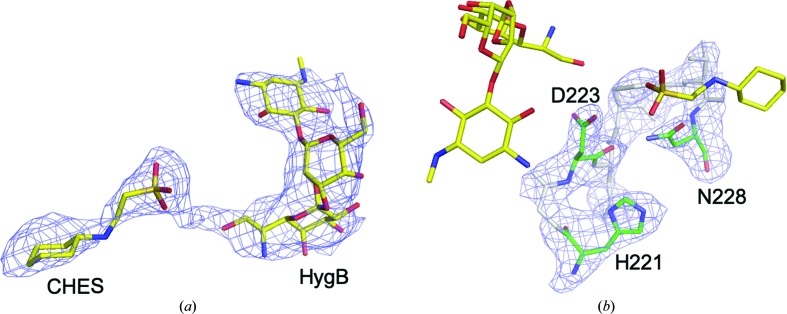

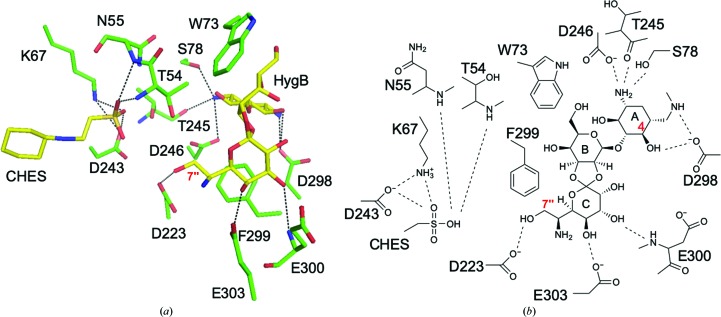

3.2. Active site of APH(7′′)-Ia complexed with hygromycin B

Electron density for HygB in chain A was fully observed, whereas that at the expected AMP-PNP binding site was partial for the nucleotide. After model refinement, the partial electron density was assumed to correspond to CHES originating from the crystallization buffer [Fig. 3 ▸(a)]. Electron density for CHES in chain B was not observed. The residues in Brenner’s motif were also clearly modeled based on the observed electron density [Fig. 3 ▸(b)]. The binding mode of HygB in chain A involved hydrogen bonds to Ser78, Asp223, Thr245, Asp246, Asp298, Glu300 and Glu303. Hygromycin B also made hydrophobic interactions between the destomic ring and Phe299 and between the hyosamine ring and Trp73 (Fig. 4 ▸). Among these residues, Asp223 is a catalytic residue in Brenner’s motif in APH(7′′)-Ia, and the distance between Asp223 OD2 and the 7′′ O atom of HygB, which is phosphorylated by APH(7′′)-Ia, was 3.1 Å. Lys67, which is one of the conserved residues in the N-lobe that interacts with a phosphate moiety of ATP in ePKs and APHs to enhance the binding affinity of ATP (Hon et al., 1997 ▸), showed distances of 3.2 and 3.3 Å between the NZ atom of Lys67 and the O atoms of the sulfate of CHES (Fig. 4 ▸). On the other hand, the distances between the O atom of the sulfate of CHES and Asp223 and the 7′′ O atom in HygB were 4.5 and 4.3 Å, respectively. Therefore, the binding mode of HygB obtained in this study most likely reflects the active mode of APH(7′′)-Ia. Although AMP-PNP and magnesium ions were included in the crystallization buffer, the bound molecule was assumed to be CHES, based on the shape of the electron density, and to originate from the buffer. In the complex structures of APH(3′)-IIIa (Burk et al., 2001 ▸), APH(9)-Ia (Fong et al., 2010 ▸) and ePKs (Narayana et al., 1997 ▸) with ADP/AMP-PNP, one or two magnesium ions are observed to interact with the phosphates in the nucleotides and they are required for the enzymatic reaction.

Figure 3.

Hygromycin B and CHES at the active site of APH(7′′)-Ia. (a) HygB and CHES are presented as stick models with an F o − F c OMIT map contoured at 2σ that was calculated excluding the two molecules. (b) The residues in Brenner’s motif (His221–Asn228) are presented as stick models colored green and gray with an F o − F c OMIT map contoured at 3σ that was calculated excluding the residues. The three catalytically important residues are colored green and labeled. HygB and CHES are depicted as stick models in yellow to represent their relative positions to the residues.

Figure 4.

Binding mode of HygB in the active site. (a) HygB and CHES are shown as stick models colored yellow. Dotted lines show hydrogen bonds with distances of less than 3.5 Å, and the hydroxyl O atom interacting with Asp223 is the site of phosphorylation by APH(7′′)-Ia. (b) Schematic representation of the binding mode of HygB and CHES as shown in (a).

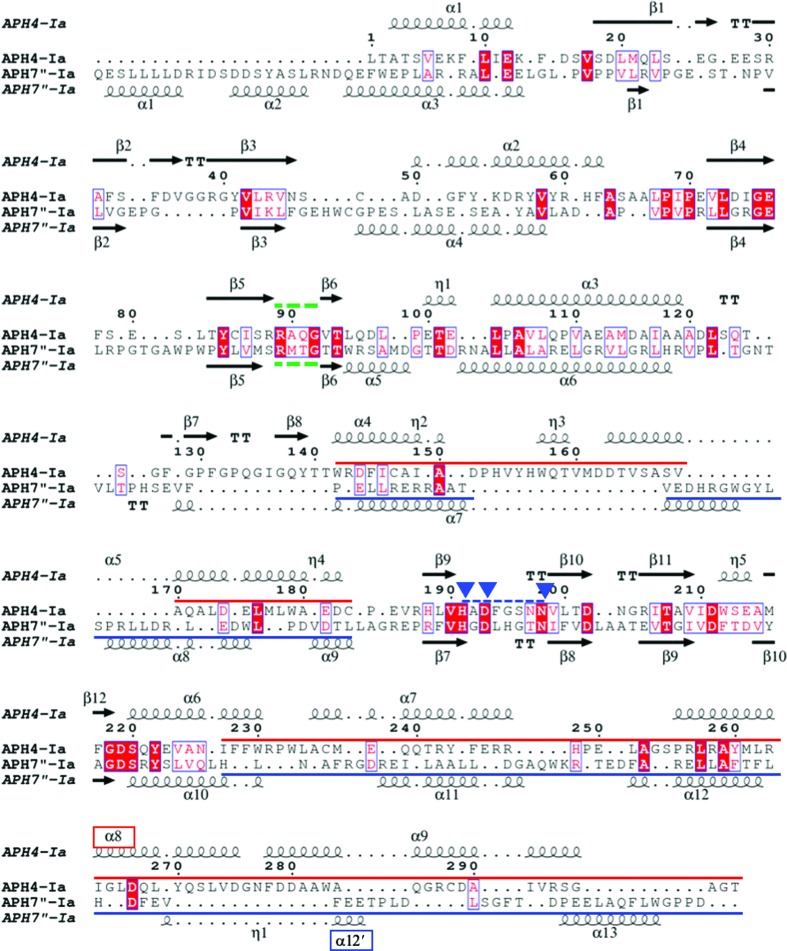

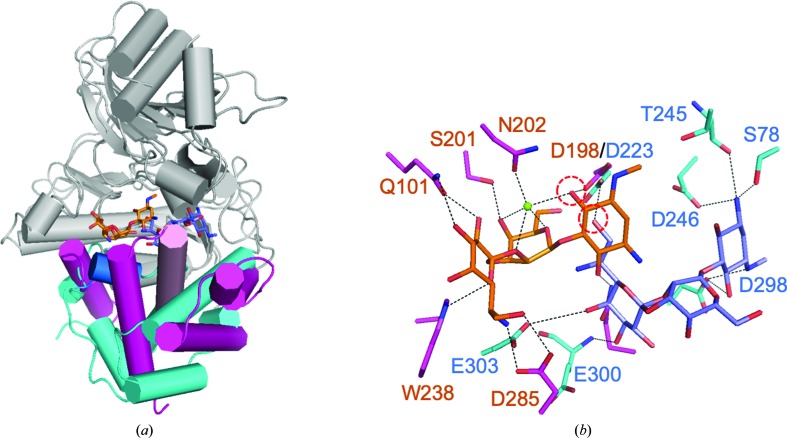

3.3. Comparison of the binding modes of HygB in APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia

Although the overall structures of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia were similar, the amino-acid sequences of the two enzymes showed low homology (Fig. 5 ▸). When the structures of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia (PDB entry 3w0s; Iino et al., 2013 ▸) were globally superposed by GESAMT in the CCP4 suite, the r.m.s.d. value was 3.30 Å for 251 residues among 325 and 303 residues in APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, respectively. Then, in order to compare the binding modes of HygB in APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia (PDB entry 3w0s), the two structures were superposed at the Cα atoms of three residues: His221 in APH(7′′)-Ia/His196 in APH(4)-Ia, Asp223/Asp198 and Asn221/Asn203 in Brenner’s motif. As shown in Fig. 6 ▸(a), the N-lobes fitted well, whereas large differences were observed in the C-lobes. The phosphorylated hydroxyl group was closer to the catalytic Asp residue, while the HygB molecules in each enzyme were placed in opposite directions. This difference seemed to reflect the conformational difference in the C-lobes between the two enzymes. When we manually tried to place the HygB molecule in APH(7′′)-Ia at the position corresponding to that in APH(4)-Ia, there was interference in α-helix 12′ (α12′) in APH(7′′)-Ia [Figs. 5 ▸ and 6 ▸(a)]. On the other hand, when it was attempted to manually place HygB in APH(4)-Ia at the position corresponding to that in APH(7′′)-Ia, α8 in APH(4)-Ia interfered. Therefore, structural differences in the C-lobes seemed to define the binding modes of HygB in the two enzymes.

Figure 5.

Sequence alignment between APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia. The sequence alignment was prepared based on a superposition of the crystal structures of APH(7′′)-Ia (chain A) and APH(4)-Ia (PDB entry 3w0s) by Chimera and the figure was prepared using ESPript (Robert & Gouet, 2014 ▸; http://espript.ibcp.fr). Green dotted lines show the residues at the border between the N- and C-lobes. The blue dotted line shows Brenner’s motif, and the three blue rectangles indicate the catalytically important residues. Blue and red lines show the regions of the helical domain in the C-lobe for APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, respectively, as colored in Fig. 6 ▸(a). α8 and α12′, which are marked in red and blue, are described in the text and in Fig. 6 ▸(a).

Figure 6.

Comparison of the binding mode of HygB in APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia. (a) The crystal structures of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia (PDB entry 3w0s) were superposed at the three catalytically important residues. Cyan and orange sticks in the middle of the proteins represent HygB in APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, respectively. The helical domains in the C-lobes are colored cyan and red in APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, respectively. The blue and pink helices present in the C-lobes represent α12′ in APH(7′′)-Ia and α8 in APH(4)-Ia, respectively. (b) HygB and its interacting partner residues are represented as stick models in blue and cyan for APH(7′′)-Ia and in orange and red for APH(4)-Ia. Red dotted circles show the hydroxyl groups phosphorylated by APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia. The small green sphere represents a magnesium ion.

Previously, enzyme kinetics have been reported for both APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia. The k cat values of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia for HygB are almost the same; on the other hand, the K m value of APH(7′′)-Ia is about ten times greater than that of APH(4)-Ia (Sugimoto et al., 2013 ▸; Nakamura et al., 2008 ▸). HygB interacted with six residues at the active site in both cases; however, HygB in APH(4)-Ia and APH(7′′)-Ia forms interactions with nine and five atoms, respectively [Fig. 6 ▸(b)]. Therefore, these differences may affect the kinetic parameters of the enzymes.

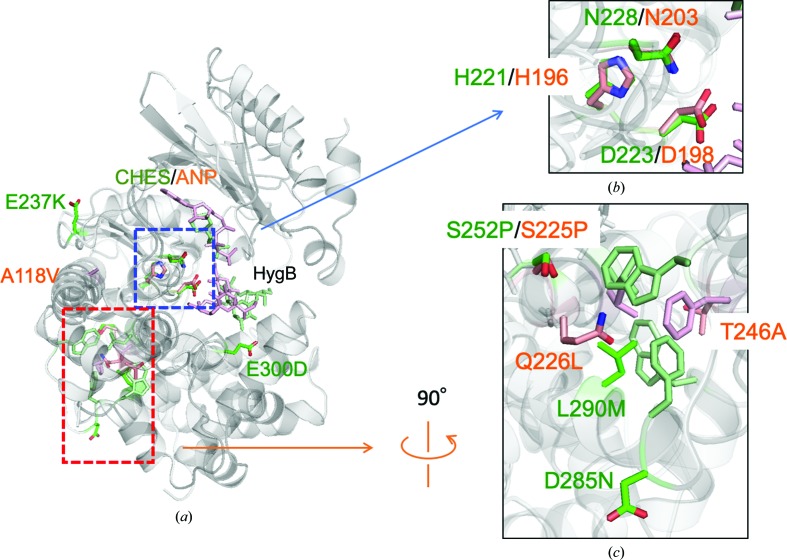

3.4. Thermostable mutants of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia

Thermostable mutants of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia have been reported previously, which exhibit optimum temperatures that are 13 and 5°C higher than those of the wild types (Sugimoto et al., 2013 ▸; Nakamura et al., 2008 ▸). They are denoted HYG10 and HPH5 as ten and five residues are mutated, respectively, in the enzymes, which were obtained by the directed-evolution method. In order to compare the mutation sites in the structures, the crystal structures of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia were superposed at the three residues in Brenner’s motif [Figs. 7 ▸(a) and 7 ▸(b)]. Several residues in both structures located in the core domain of the C-lobe seemed to increase the hydrophobic interactions in the domain. Interestingly, Ser252 in APH(7′′)-Ia and Ser225 in APH(4)-Ia were located at the same position on superposition, and the serine residues were substituted by prolines in both thermostable structures [Fig. 7 ▸(c)] and are located at the end of α-helices. Therefore, the strengthening of the hydrophobic core in the core domain seems to be effective in increasing the thermal stability of the enzymes.

Figure 7.

Thermostable mutants of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia. The crystal structures of APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia (PDB entry 3w0s) are superposed at the three residues in Brenner’s motif. (a) Superposed structures are shown as cartoon models. Residues colored green and orange represent APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, respectively. (b) Three residues, His, Asp and Asn, in Brenner’s motif were used to superpose the two enzymes. Residue numbers in green and orange correspond to APH(7′′)-Ia and APH(4)-Ia, respectively. (c) Part of the core domain in the orange rectangle in (a) is enlarged. The numbered residues are those that are mutated in the thermostable mutants. Nonlabeled residues are shown as components of the hydrophobic core for both the APH(7′′)-Ia (green) and APH(4)-Ia (orange) enzymes.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: aminoglycoside 7′′-phosphotransferase-Ia, 6iy9

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the Photon Factory for their assistance during data collection.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development grant JP18am0101071.

References

- Adams, P. D., Afonine, P. V., Bunkóczi, G., Chen, V. B., Davis, I. W., Echols, N., Headd, J. J., Hung, L.-W., Kapral, G. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Oeffner, R., Read, R. J., Richardson, D. C., Richardson, J. S., Terwilliger, T. C. & Zwart, P. H. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Baker, N. A., Sept, D., Joseph, S., Holst, M. J. & McCammon, J. A. (2001). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 98, 10037–10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boehr, D. D., Daigle, D. M. & Wright, G. D. (2004). Biochemistry, 43, 9846–9855. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Borovinskaya, M. A., Shoji, S., Fredrick, K. & Cate, J. H. D. (2008). RNA, 14, 1590–1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brenner, S. (1978). Nature (London), 329, 21.

- Burk, D. L., Hon, W. C., Leung, A. K.-W. & Berghuis, A. M. (2001). Biochemistry, 40, 8756–8764. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cole, P. A., Grace, M. R., Phillips, R. S., Burn, P. & Walsh, C. T. (1995). J. Biol. Chem. 270, 22105–22108. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Daigle, D. M., McKay, G. A. & Wright, G. D. (1997). J. Biol. Chem. 272, 24755–24758. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ferretti, J. J., Gilmore, K. S. & Courvalin, P. (1986). J. Bacteriol. 167, 631–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fong, D. H., Lemke, C. T., Hwang, J., Xiong, B. & Berghuis, A. M. (2010). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9545–9555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fong, D. H., Xiong, B., Hwang, J. & Berghuis, A. M. (2011). PLoS One, 6, e19589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Fourmy, D., Recht, M., Blanchard, S. C. & Puglisi, J. D. (1996). Science, 274, 1367–1371. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hon, W.-C., McKay, G. A., Thompson, P. R., Sweet, R. M., Yang, D. S. C., Wright, G. D. & Berghuis, A. M. (1997). Cell, 89, 887–895. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Iino, D., Takakura, Y., Fukano, K., Sasaki, Y., Hoshino, T., Ohsawa, K., Nakamura, A. & Yajima, S. (2013). J. Struct. Biol. 183, 76–85. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jurrus, E., Engel, D., Star, K., Monson, K., Brandi, J., Felberg, L. E., Brookes, D. H., Wilson, L., Chen, J., Liles, K., Chun, M., Li, P., Gohara, D. W., Dolinsky, T., Konecny, R., Koes, D. R., Nielsen, J. E., Head-Gordon, T., Geng, W., Krasny, R., Wei, G.-W., Holst, M. J., McCammon, J. A. & Baker, N. A. (2018). Protein Sci. 27, 112–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kabsch, W. (1976). Acta Cryst. A32, 922–923.

- Kabsch, W. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Krissinel, E. & Henrick, K. (2007). J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lovell, S. C., Davis, I. W., Arendall, W. B. III, de Bakker, P. I. W., Word, J. M., Prisant, M. G., Richardson, J. S. & Richardson, D. C. (2003). Proteins, 50, 437–450. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Madhusudan, Trafny, E. A., Xuong, N.-H., Adams, J. A., Ten Eyck, L. F., Taylor, S. S. & Sowadski, J. M. (1994). Protein Sci. 3, 176–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Murray, B. E. (1990). Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 3, 46–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, A., Takakura, Y., Sugimoto, N., Takaya, N., Shiraki, K. & Hoshino, T. (2008). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 72, 2467–2471. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Narayana, N., Cox, S., Nguyen-Huu, X., Ten Eyck, L. F. & Taylor, S. S. (1997). Structure, 5, 921–935. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nurizzo, D., Shewry, S. C., Perlin, M. H., Brown, S. A., Dholakia, J. N., Fuchs, R. L., Deva, T., Baker, E. N. & Smith, C. A. (2003). J. Mol. Biol. 327, 491–506. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pardo, J. M., Malpartida, F., Rico, M. & Jiménez, A. (1985). J. Gen. Microbiol. 131, 1289–1298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, R. C., Wolfe, R. N., Hoehn, M. M., Marks, P. N., Daily, W. A. & McGuire, J. M. (1953). Antibiot. Chemother. 3, 1268–1278. [PubMed]

- Ramirez, M. S. & Tolmasky, M. E. (2010). Drug Resist. Updat. 13, 151–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Rao, R. N., Allen, N. E., Hobbs, J. N. Jr, Alborn, W. E. Jr, Kirst, H. A. & Paschal, J. W. (1983). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 24, 689–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Robert, X. & Gouet, P. (2014). Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W320–W324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Skubák, P. & Pannu, N. S. (2013). Nature Commun. 4, 2777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stogios, P. J., Shakya, T., Evdokimova, E., Savchenko, A. & Wright, G. D. (2011). J. Biol. Chem. 286, 1966–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, N., Takakura, Y., Shiraki, K., Honda, S., Takaya, N., Hoshino, T. & Nakamura, A. (2013). Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 77, 2234–2241. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Toth, M., Chow, J. W., Mobashery, S. & Vakulenko, S. B. (2009). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 6690–6696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wachino, J. I. & Arakawa, Y. (2012). Drug Resist. Updat. 15, 133–148. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wilson, D. N. (2014). Nature Rev. Microbiol. 12, 35–48. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Winn, M. D., Ballard, C. C., Cowtan, K. D., Dodson, E. J., Emsley, P., Evans, P. R., Keegan, R. M., Krissinel, E. B., Leslie, A. G. W., McCoy, A., McNicholas, S. J., Murshudov, G. N., Pannu, N. S., Potterton, E. A., Powell, H. R., Read, R. J., Vagin, A. & Wilson, K. S. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 235–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Woodcock, J., Moazed, D., Cannon, M., Davies, J. & Noller, H. F. (1991). EMBO J. 10, 3099–3103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: aminoglycoside 7′′-phosphotransferase-Ia, 6iy9