Abstract

Social evaluative threat is a potent activator of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis in typically developing (TD) populations. Studies have shown that children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) show a blunted cortisol response to this type of stressor; yet, a previous study in adults with ASD reported a more prototypical stress response. The current study compared 24 adolescents and 17 adults with ASD to investigate a possible developmental lag in autism resulting in a more adaptive stress response to social evaluation with development. Participants were exposed to the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), and salivary cortisol was collected before and after stress induction. Multilevel modeling revealed that relative to adolescents, young adults with ASD evidenced a significant increase in cortisol in response to anticipatory stress, and 23.5% were classified as anticipatory responders. Adolescents, however, had a significant change in slope in response to the TSST, with 37.5% classified as reactive responders. In both groups, the majority of participants did not have a robust stress response to the TSST as would be expected in TD participants. Findings suggest significant differences in the cortisol trajectory; adults with ASD were more likely to show an anticipatory response to being socially evaluated, which was maintained throughout the stressor, whereas the adolescents had a more reactive response pattern with no anticipatory response. Further research is needed to determine if such patterns are adaptive or deleterious, and to determine underlying factors that may contribute to distinct stress profiles and to the overall diminished stress responses.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder, adolescence, adults, cortisol, HPA axis, stress

Lay Summary

Many individuals have increased stress when being socially evaluated. The current study shows that adults with ASD have increased stress in anticipation of a task in which individuals are required to give a speech to unfamiliar raters, while adolescents with ASD tend to show a stress response only during the task itself. Further research is necessary to understand whether developmental influences on stress response in ASD have significant impacts on other areas of functioning often affected by stress.

Introduction

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis is involved in the regulation of several biological processes that include the physiological response to stress, which results in the release of cortisol from the adrenal cortices. Activation of the HPA axis occurs in response to significant physiological and perceived psychological stress. Regarding the latter, humans must determine the extent to which a given situation threatens their well-being via cognitive appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman, 1984). In humans, four primary psychological determinants have been shown to promote a stress response and include novelty, unpredictability, social evaluation, and a sense of low control (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004, Mason, 1968). The degree of responsivity can be affected by factors such as context (e.g., social) and development (e.g., age, puberty) (e.g. (Gunnar et al., 2009)).

A potent activator of this primary stress system is social evaluation in which the prospect of being negatively evaluated by others triggers strong physiological and affective responses (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004). Under such circumstances, there is an inherent motivation to be perceived favorably by others. While self-preservation is adaptive, individuals who exhibit a pattern of heightened sensitivity to social evaluation may have health risks, such as cardiovascular disease (e.g. (Lovallo and Gerin, 2003)). In addition to the response to social evaluation, the mere anticipation of social evaluation may be considered a stressor (e.g. (Engert et al., 2013)). It has been shown that early anticipatory stress as opposed to reactive stress as measured by cortisol during public speaking is associated with a variety of factors such as alexithymia (de Timary et al., 2008) and PTSD (e.g. (Bremner et al., 2003)). The most established lab-based stress induction protocol examining social evaluative threat is the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) (Kirschbaum et al., 1993). The TSST is a well-validated measure of psychosocial stress shown to robustly activate the HPA axis when compared to many other laboratory stressors (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004, Kudielka et al., 2007).

In contrast to typically developing (TD) individuals, many with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) do not show robust HPA axis activation in response to the TSST (e.g. (Corbett et al., 2012, Edmiston et al., 2017, Levine et al., 2012)). An autism diagnosis is characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and communication (APA, 2013). These difficulties- particularly in social cognition- may result in differential experiences of social evaluative threat in individuals with ASD. This difference in perception of evaluative threat may correspond with these atypical HPA axis reactivity patterns, which are often characteristic of individuals with ASD (e.g. (Taylor and Corbett, 2014)).

The majority of the characterization of diurnal fluctuations and reactivity of the HPA axis in ASD has been conducted on children (e.g. (Corbett and Schupp, 2014, Tomarken et al., 2015)), with few on adolescents (Edmiston et al., 2017 ) or adults (Nir et al., 1995, Tani et al., 2005). Research in children has generally shown a heightened cortisol response to benign social interactions compared to TD children who do not exhibit stress during play encounters (e.g. (Corbett et al., 2010, Lopata et al., 2008, Schupp et al., 2013)). In contrast, relative to TD children, children with ASD tend to show a blunted cortisol response to the TSST (Corbett et al., 2012, Jansen et al., 2000, Lanni et al., 2012, Levine et al., 2012).

Characterization of HPA axis functioning is limited in adolescents and adults with ASD. Recently, adolescents approximately 13–17 years old with ASD and TD were exposed to the TSST, with results showing a similar profile to children with ASD. Specifically, TD adolescents showed increased salivary cortisol in response to social evaluation, whereas the adolescents with ASD had a significantly blunted cortisol response (Edmiston et al., 2017). Previous studies of adults, however, have found few differences between ASD and TD individuals, including a more prototypical heightened response to social judgment in a small sample of young adults around 19–23 years of age with ASD (Jansen et al., 2006). Additionally, there were no reported differences in cortisol response to other social stressors in more recent studies of young to middle-aged (18–55 years) adults with ASD compared to TD individuals (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2017, Smeekens et al., 2015). Resting state cortisol does not appear to differ between ASD and TD adults (Smeekens et al., 2015, Tani et al., 2005), and limited analysis of diurnal rhythm of the HPA axis in a small sample of adolescents and adults ages 11–30 years with ASD or TD suggest no differences in diurnal activity between diagnostic groups (Goldman et al., 2017).

With previous studies showing a blunted cortisol response to social evaluation in adolescents with ASD (Edmiston et al., 2017) but a typical response in adults with ASD (Jansen et al., 2006), there may be a developmental effect such that by adulthood, individuals with ASD begin to show a more typical stress response (Edmiston et al., 2017). The potential impact of such developmental differences in the physiological response to stress should be considered (Lupien et al., 2009). Abnormal physiological reactivity to social stress in ASD, including blunted HPA axis reactivity or hypocortisolism, could have significant negative health consequences, as low levels of cortisol have been correlated with other stress-related pathologies, such as chronic fatigue, chronic pain, and others, across development (e.g. (Heim et al., 2000)).

While the preexisting literature provides some limited evidence for developmental differences in the functioning of the HPA axis in ASD, no study to date has directly compared physiological responses to social evaluative threat in adolescents versus adults with ASD. Given the deleterious role that stress may play in psychological, physical, and social well-being, the current study was undertaken. The response to social evaluative threat was of particular interest, to determine if differences exist in adaptive stress response to the TSST in adults compared to adolescents with ASD. It was hypothesized that adults with ASD would show different patterns of response than adolescents with ASD, as evidenced by significantly higher cortisol in response to the social evaluative stressor.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants included 24 adolescents with ASD between 13–17 years of age (mean age = 14.80) compared to 17 adults with ASD between 18–22 years of age (mean age = 19.62), drawn from two larger studies. Families were recruited from the community through research registries, other autism-related studies, ASD diagnostic clinics, and local autism/disability organizations. In regards to gender, there were zero and four females in the adolescent and adult samples, respectively. All participants had an intelligence quotient (IQ) score of 70 or higher.. Due to the high rate of medication use in the adolescent and adult population, we did not select medication-naïve participants. However, none of the participants were currently taking medications known to interfere with the HPA axis stress response (Granger et al., 2009), such as antipsychotics or steroid medications. Additionally, those on stimulants abstained from usage prior to and on the day of the protocol. Specifically, 24 participants were on at least one medication, including SSRIs/SNRIs (n=14), stimulants (n=11), alpha-adrenergic receptor agonists (n=6), anti-epileptics (n=3) and anti-cholinergics (n=2). Some participants were on more than one medication type. Demographic information for each age group is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and Baseline Data

| Variable | ASD Adolescent | ASD Adult | t | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Age | 14.80 | 1.36 | 19.62 | 0.52 | −15.79 | 0.0001 |

| ADOS Total Score | 12.25 | 4.25 | 13.12 | 4.14 | −0.65 | 0.52 |

| IQ | 107.71 | 22.03 | 97.00 | 14.32 | 1.76 | 0.09 |

| SRS Total | 74.88 | 11.02 | 71.12 | 15.15 | 0.92 | 0.36 |

| AFT Cortisol | 0.47 | 0.26 | 0.52 | 0.16 | −0.57 | 0.57 |

ASD, autism spectrum disorder; M, mean; SD, standard deviation; ADOS, autism diagnostic observation schedule; IQ, intelligence quotient; SRS, social responsiveness scale; AFT, afternoon. Cortisol values reflect log-transformed values in nmol/L.

Diagnostic Criteria

The diagnosis of ASD was based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (APA, 2013) and established by: (1) a previous diagnosis by a psychologist, psychiatrist, or behavioral pediatrician with autism expertise; (2) current clinical judgment and (3) corroborated by the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) (Lord et al., 2000), administered by research-reliable personnel. Total ADOS scores were used to test for group differences in autism symptoms. Intelligence quotient (IQ) scores were measured by the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI) (Wechsler, 1999) for the adolescents and the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales (Roid, 2003) for the adult participants. Distinct lab procedures and funding across the two groups determined the intelligence measure used.

It is important to note that co-occurring psychiatric conditions are highly prevalent among adults with ASD and accordingly they were common in the adult sample. Based on parental report of current diagnoses, 10 out of the 17 adult participants were reported to have at least one co-occurring condition, with 4 adults reportedly diagnosed with major depression, 5 with anxiety disorder, 1 with obsessive-compulsive disorder, 1 with post-traumatic stress disorder, and 7 with ADD/ADHD. Despite the higher rate of internalizing disorder diagnoses, internalizing symptoms did not significantly differ between groups, (Achenbach Child/Adult Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 2001, Achenbach, 2003) Internalizing t-scores = 61.87 for adolescents and 59.65 for adults, t (38) = .683, p=.50.

The Social Responsiveness Scale- Second Edition (SRS-2) (Constantino and Gruber, 2012) was administered as an indicator of the adolescent/adults’ autism severity. The SRS-2 is a 65-item questionnaire, which asks caregivers (in this case, parents) to report on severity of autistic traits in individuals with ASD. Items are rated on a Likert scale from zero to three, and scores are totaled across five domains: Social Awareness, Social Motivation, Social Cognition, Social Communication, and Restrictive and Repetitive Behaviors. Total t-scores were used, with higher scores indicating greater autism severity.

The research was carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). The Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board approved the study. In compliance with the Vanderbilt Institutional Review Board determinations, informed written consent/assent was obtained from all study participants and care providers prior to inclusion in the study. Participation required two research visits to the University. The diagnostic and cognitive measures were administered during visit 1. The participants and family members were trained on the salivary collection methods (see below). On visit 2, participants were exposed to the TSST, Though broader study protocols differed between the adolescent and adult sample, the same study personnel implemented identical TSST procedures for both the adolescent and adult participants.

Procedures

Trier Social Stress Test

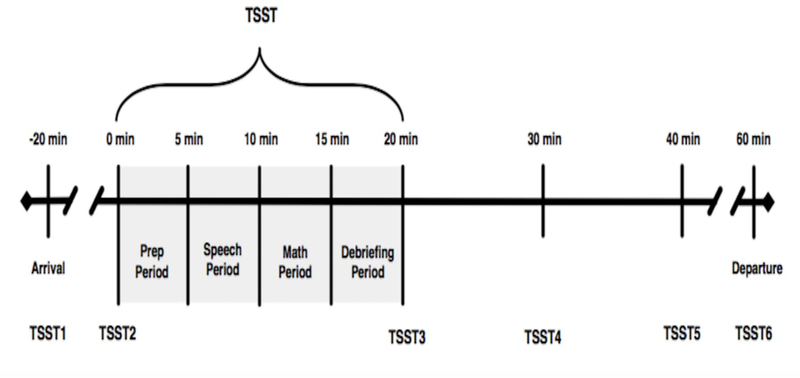

The Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) (Kirschbaum et al., 1993) is a well-validated, experimentally induced psychosocial stressor known to reliably activate the HPA axis in TD populations (Kudielka et al., 2004). The TSST combines several elements shown to activate the HPA axis including social evaluative threat, unpredictability, and uncontrollability to produce moderate stress in a majority of children, adolescents, and adults (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004, Kirschbaum et al., 1993). The TSST is a 20-min task divided into four subcomponents including: 1) Intro/Preparation, 2) Present Speech, 3) Serial Subtraction, and 4) Debriefing. The task also includes the collection of six salivary samples (see Figure 1). The protocol involves a scenario in which the participant must prepare a speech to convince a panel of judges (neutral, unresponsive judges lacking supportive affect) that he/she is the best candidate for a job, followed by a serial subtraction task. The TSST results in a profound increase of salivary cortisol in 70–80% of participants (Kirschbaum et al., 1993, Kudielka et al., 2004).

Figure 1, TSST Timeline.

Schematic of TSST and salivary cortisol sampling procedure.

Salivary Cortisol Collection

Salivary cortisol can be measured reliably and non-invasively utilizing small amounts of saliva, making it an ideal measure in studies of children and youth (Kirschbaum and Hellhammer, 2000). Samples were collected according to previously described detailed methods (Corbett and Schupp, 2014). As a separate part of the study, participants were instructed on home sampling techniques, providing four samples (immediate waking, 30-min post-waking, afternoon, and evening) across three days. The current study used the afternoon sample (AFT; between 1 pm and 4 pm) to compare baseline afternoon samples with initial cortisol samples upon arrival at the lab (all TSSTs were conducted in the afternoon). Additionally, participants provided six samples on the day of the TSST, including at 20-min. pre-TSST, immediately prior to the TSST, immediately after the TSST, as well as 10-, 20- and 40-min. post-TSST, reflecting stress response before (TSST1 and TSST2), during (TSST3 and TSST4), and after (TSST5 and TSST6) the stressor (see Figure 1 for timing of sample collection). Importantly, there is a 20-minute lag time in detecting a stress response. Participants were instructed not to eat or drink anything other than water one hour before arrival at the lab for the first sample. Samples were collected via passive drool into a test tube, and participants provided at least one mL of saliva for each sample.

Cortisol Assay

Prior to assay, samples were stored at −20°C. For the adolescent study, the salivary cortisol assay was performed using a Coat- A-Count® radioimmunoassay (RIA) kit (Siemens Medical Solutions Diagnostics, Los Angeles, CA) modified to accommodate lower levels of cortisol in human saliva relative to plasma. Saliva samples were thawed and centrifuged at 3460 rpm for 15 min to separate the aqueous component from mucins and other suspended particles. All samples were duplicated. The coated tube from the kit was substituted with a glass tube into which 100ml of saliva, 100ml of cortisol antibody (courtesy of Wendell Nicholson, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN), and 100ml of 125I-cortisol were mixed. After incubation at 4°C for 24h, 100ml of normal rat serum in 0.1% PO4/ EDTA buffer (1:50) and precipitating reagent (PR81) were added. The mixture was centrifuged at 3460 rpm for 30 min, decanted, and counted. Serial dilution of samples indicated a linearity of 0.99. Interassay coefficient of variation was 1.62%.

For the adult study, the saliva samples were stored at −20°C or below until shipped with dry ice overnight for assay. On the day of assay, samples were thawed, centrifuged to remove mucins, and tested in duplicate for cortisol using a commercially available enzyme immunoassay without modification to the manufacturer’s protocol (Salimetrics LLC, Carlsbad, CA). The test volume was 25 μL, range of sensitivity from .007 to 3.0 ug/dL, and on average, inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were less than 15 and 10% respectively. Prior to data analysis, all cortisol assay values were converted to nmol/L.

Statistical Analysis

First, independent sample t-tests were conducted to test for differences between the adolescent and young adult groups in demographic and diagnostic variables. Diurnal afternoon cortisol values (i.e., AFT) were averaged across the three sampling days and compared using independent sample t-tests to confirm there were no baseline differences between adolescents and young adults. Due to cortisol samples being positively skewed, all cortisol values were log transformed prior to analysis. Based on the Levene’s Test of Equality of Error Variance, there were no significant differences in variance between the groups for the TSST samples (all p > 0.05).

We ran multilevel models using the Hierarchical Linear Modeling software (Raudenbush and Bryk, 2002) to test for group differences in patterns of cortisol response over time. Given the typical pattern of cortisol change across the TSST, we modeled discontinuous individual change with three time epochs (Singer and Willett, 2003): 1) linear slope from TSST1 to TSST2, representing anticipatory stress; 2) change in linear slope from TSST2 to TSST4, representing stress in response to the TSST; and 3) change in linear slope from TSST4 to TSST6, representing recovery from the TSST. To generate an average estimate of each slope across the entire sample, we first estimated an “unconditional” model that included the within-person time variables. Then, a second multi-level model was estimated that included the between-subjects variable of age group, with groups centered on zero (adolescent = −0.5, young adult = 0.5). Including age group into the model allowed us to determine whether any of the slope estimates (slope representing anticipatory stress, change in slope in response to the TSST, further change in slope during recovery from the TSST) significantly differed by age group. As there were no variables other than age that differed between groups (see Table 1), we did not add any additional between-person covariates in the models.

Results

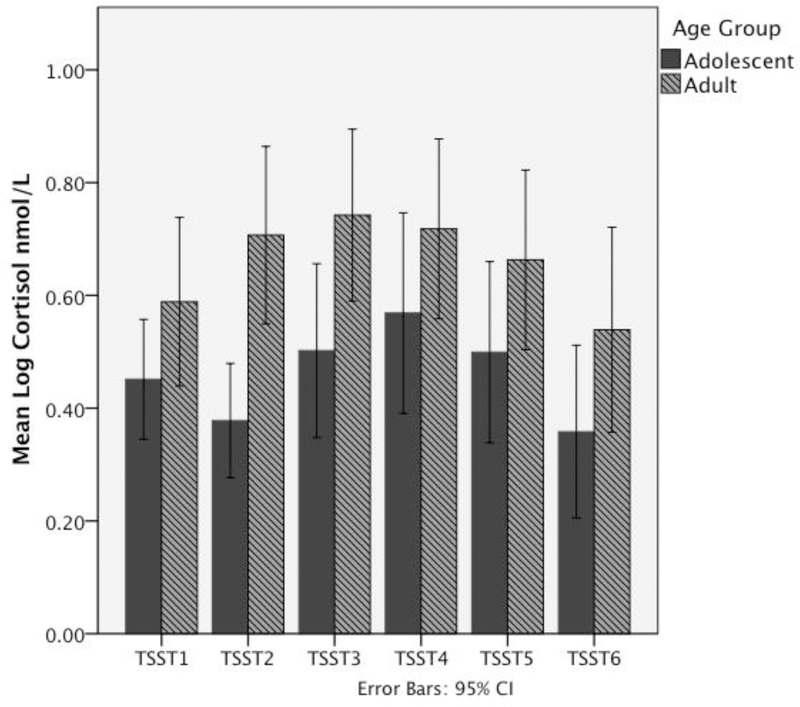

Group differences in demographic and baseline data are presented in Table 1. There were expected differences between the groups based on age. There were no significant differences in total IQ, total autism symptoms based on the ADOS (Lord et al., 2000), or social symptoms of the SRS (Constantino and Gruber, 2012). Additionally, there were no group differences in afternoon cortisol (collected at home during diurnal saliva collection, at approximately the same time as the arrival sample). Lack of significant group differences in AFT cortisol is consistent with prior research in the lab showing comparable basal levels (Corbett et al., 2014); it suggests that there were likely not systematic differences in the values produced from the assays used in the adolescent versus adult samples. Average cortisol values at each sampling time point are shown in Figure 2; repeated measures ANOVA examining overall differences in cortisol as well as differences at each time point are presented in supplemental material.

Figure 2, Average cortisol levels during TSST.

Salivary cortisol levels (in nmol/L) during the TSST in adolescents and adults with ASD. Graph shows higher cortisol levels in the adult group, especially at TSST2. All values are log-transformed.

Results from Multilevel Models

Unconditional model

Results of the unconditional growth model, examining average change for the combined adolescent and young adult sample for the three slopes (anticipatory stress, response to TSST, recovery) are presented in Table 2. On average, across the samples, there was no statistically significant change in cortisol from TSST1 to TSST2 (anticipatory stress), B = .04, and no average change in slope in response to the TSST (TSST2 to TSST4), B = .02. There was an average change in slope of cortisol across the adolescent and adult samples during recovery (TSST4 to TSST6), B = −.17, resulting in an average decline from TSST4 to TSST6 of .11 nmol/L per time point (.04 + .02 − .17). Thus, when averaging across the adolescent and young adult sample, there appears to be little cortisol response to either anticipatory stress or to the TSST, but a decline in cortisol during the recovery period.

Table 2.

Estimates from Multilevel Models of Change in Cortisol across the TSST – Unconditional and Conditioned on Age Group

| Variable | Model Estimates |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unconditional Model | Conditioned on Age Group | |||

| Coefficient | SE | Coefficient | SE | |

| Initial status intercept (random) | 0.48** | 0.04 | 0.50** | 0.04 |

| Age group | - - - - - - - - - - | - - - - - - | 0.18* | 0.09 |

| Anticipatory stress slope (random) | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| Age group | - - - - - - - - - - | - - - - - - | 0.15* | 0.06 |

| Response to TSST slope (random) | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Age group | - - - - - - - - - - | - - - - - - | −0.24** | 0.07 |

| Recovery from TSST slope (random) | −0.17** | 0.03 | −0.16** | 0.03 |

| Age group | - - - - - - - - - - | - - - - - - | 0.11 | 0.06 |

p < .05

p < .01

Note. Slope estimates are additive. Thus, the average slope for response to TSST can be calculated by adding the anticipatory stress slope with the response to TSST slope (0.05 + 0.00 = 0.05). The average slope for recovery from TSST can be calculated by adding the three slopes (0.05 + 0.00 − 0.16 = −0.11).

Adding Age Group

Results of the multi-level model adding the between-persons factor of age group are presented in Table 2. Age group significantly predicted initial cortisol levels (TSST1); adolescents with ASD had initial cortisol levels (at TSST1) that averaged .18 nmol/L less than those of young adults. Age group also predicted change in cortisol due to anticipatory stress and change in slope in response to the TSST, but not change in slope of cortisol during recovery.

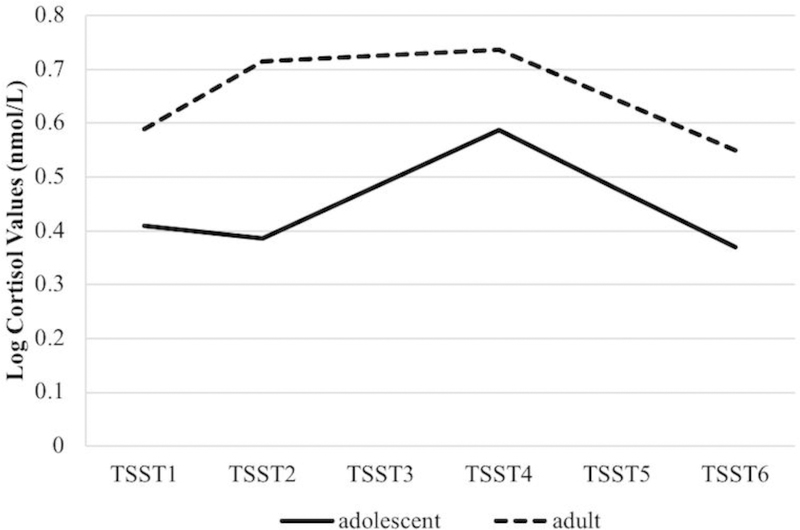

Growth curve models, conditioned on age group, are plotted in Figure 3. Cortisol values of the adolescent sample did not change in response to anticipatory stress (TSST1 to TSST2), B = −.02, SE = .04, p = .53, but there was a significant change in slope in response to the TSST, B = .12, SE = .05, p = .01; logged cortisol values increased by .10 (−.02 + .12) nmol/L per time point during the TSST (TSST2 to TSST4). There was another significant change in slope cortisol during the recovery period for the adolescent group, B = −.21, SE = .05, p < .01, with logged cortisol values decreasing by .11 (−.02 + .12 − .21) nmol/L per time point during this period (TSST4 to TSST6). Thus, adolescents with ASD experienced a rise in cortisol in response to the TSST, with a decline in cortisol during the recovery period. There was no evidence of anticipatory stress.

Figure 3, Plot of estimated trajectories of cortisol during the TSST paradigm by age group.

Trajectory plot shows increased cortisol in anticipation of TSST in adults with ASD, and increased cortisol during, but not in anticipation of, TSST in adolescents with ASD. All values are log transformed and in units of nmol/L.

Relative to adolescents, young adults with ASD evidenced different patterns of cortisol change during the TSST (see Figure 3). Their logged cortisol values significantly increased in response to anticipatory stress, B = .13, SE = .05, p = .01, and that increase was attenuated during the stress response to the TSST, B = −.12, SE = .05, p = .03; slope of logged cortisol changed from .13 nmol/L per time point during the anticipatory stress period, to .01 nmol/L per time point (.13 − .12) during the TSST. There was another significant change in slope during the recovery period for this group, B = −.10, SE = .03, p < .01, with logged cortisol values declining by .09 (.13 − .12 − .10) nmol/L per time point during this period. Thus, young adults with ASD experienced a rise in cortisol in anticipation of the TSST, no additional rise during the TSST, and a decline in cortisol during the recovery period.

Autism severity has been shown to relate to HPA axis response (e.g. (Hoshino et al., 1984). Though measures of autism symtoms did not differ between groups, we reran the multi-level model and included ADOS total score as a predictor of intercept and each slope (in addition to age group). The only significant relation between autism symptoms and cortisol response pertained to the recovery phase, B = 0.013, SE = 0.005, t = 2.32, p < .05; adolescents and adults with more autism symptoms had a longer return to basal, pre-stress levels of cortisol.

Follow-up Analyses: Anticipatory Responders versus Reactive Responders

Although many of the adolescents and adults had cortisol rises during the TSST (either in anticipatory stress or in response to the TSST), the afore-described analyses do not test whether the rise is sufficient to be considered a physiological “response.” To understand the proportion of adolescents and adults with ASD who have a response to the TSST, we used a well-accepted benchmark for TSST “responders” of 2.5 nmol/L (Van Cauter and Refetoff, 1985, Schoomer et al., 2003). We examined three types of response: any response during the TSST (highest cortisol value – TSST1), response to anticipatory stress (TSST2 – TSST1) and response to TSST (highest of TSST3/4 – TSST2). Consistent with the multi-level models, we observed similar rates of responders, but different types of responses. Specifically, 37.5% of adolescents and 41.2% of adults were TSST responders, as indicated by a rise in cortisol at any post-TSST1 time point of 2.5 nmol/L or more, χ2(1)=.06, p=.81. Adults were more likely than adolescents to be anticipatory responders (ARs), with 23.5% of adults and no adolescents showing this response, χ2(1)=6.26, p=.01. Adolescents were marginally more likely than adults to be reactive responders (RRs) to the TSST itself, with 37.5% of adolescents and 11.8% of adults responding, χ2(1)=.3.36, p=.07.

Discussion

The current study aimed to examine differences in the trajectory and temporal dynamics of social stress in adults with ASD compared to adolescents with ASD. It was predicted that adults with ASD would show significantly higher cortisol response to a social evaluative stressor, the TSST. The findings partially confirmed this hypothesis: though adolescents and adults had similar rates of responding to the TSST, the patterns and timing of response were different between groups. For the young adult group, as graphically shown in Figures 2 and 3, cortisol values significantly increased in anticipation of the stressor, and this significant elevation was maintained throughout the stressor until gradually declining during the recovery period. While there were no differences in baseline values between the groups from afternoon home comparisons at arrival, the adults with ASD showed elevations in cortisol in anticipation of being socially evaluated.

While stress reactivity is often the primary focus of studies using the TSST, anticipatory stress can be dissociated from the response phase. For example, alexithymia, a general deficit in processing and distinguishing feeling states in self and others, has been associated with significant elevation in cortisol in anticipation of the TSST, but not in response to the stressor (de Timary et al., 2008). Across a series of studies employing frequent, serial salivary collection in TD individuals, Engert and colleagues were able to identify a subgroup of anticipatory responders who showed an increase in cortisol early in the task before the acute stressor could trigger HPA axis reactivity (Engert et al., 2013). Moreover, healthy individuals who showed higher cortisol in anticipation of the TSST, also showed more reactive stress responses (Engert et al., 2013). This pattern of higher anticipatory cortisol and maintained stress reactivity was observed in the adults with ASD in the current study. Similarly, in a sample of healthy adult participants exposed to the TSST, Juster and colleagues (Juster et al., 2012) showed that self-reported anticipatory stress predicted increased stress reactivity as measured by cortisol. In other words, the priming effect of anticipation may influence cognitive states and physiological arousal (Juster et al., 2012), such that greater anticipation of stress may further modulate the effects of stress response in adults with ASD. Thus, enhanced anticipatory cortisol response may be an index of increased subjective stress sensitivity and enhanced responsivity.

These findings may have clinical and developmental implications for adults with ASD. If it is the case that adults with ASD experience more anticipatory stress to social evaluative situations over time, it would behoove care providers to be aware of possible increased arousal and to provide education and support as appropriate. For example, it is adaptive for most TD individuals to experience discomfort when being judged by others; therefore, normalizing such anticipatory stress through shared knowledge and experience may be helpful. For some individuals, it may be necessary to teach stress reduction training and coping strategies if increased arousal interferes with daily functioning (e.g., job interviewing). Indeed, a recent study showed that practice with android robot-mediated job interview sessions resulted in lower levels of salivary cortisol and improved self-confidence compared to a control condition (Kumazaki et al., 2017).

Dysregulation of the HPA axis can have far-reaching implications for psychological and metabolic health; therefore, discerning the acute stress response patterns is important and informative. Recently, three primary physiological response patterns using cortisol were studied in a large sample of 798 18-year old participants. Of the total participant sample, 26.2% were characterized as anticipatory responders (AR), 56.6% as reactive responders (RR), and 17.2% were non-responders (NR), and these patterns appear to vary with health and disease (Herbison et al., 2016). In the current study, adults with ASD were more likely than adolescents to be anticipatory responders (AR), such that 23.5% of adults showed a response, whereas none of the adolescents showed an AR response pattern. At this time, it is unclear what factors may be driving this anticipatory rise in the adult group. Since there were no significant group differences in the afternoon diurnal sample, there does not appear to be differences in tonic functioning of the HPA axis. However, the study does not allow us to determine if other stress-sensitive parameters (e.g., sex, chronic stress) or plausible experience-dependent developmental factors (e.g., cognitive appraisal, insight) may contribute to the observed differences. While it is beyond the scope of the current study aims, investigating factors that may contribute to the different patterns in the ASD groups in addition to age may be informative and help determine if such cortisol profiles are adaptive or deleterious.

In contrast to the adults with ASD, cortisol values of the adolescent group did not change in anticipation of the stressor; however, there was a significant increase in cortisol in response to the stressor. Thus, the reactive slope for adolescents was much steeper. Adolescents with ASD were marginally more likely than adults to be reactive responders (RR), such that 37.5% of adolescents showed a sharp rise in cortisol in response to the TSST, whereas only 11.8% of adults exhibited an RR response. While a larger number of adolescents compared to the adult group showed a response to the TSST, a significant majority in both groups did not evidence a stress response. Therefore, the results are consistent with previous findings showing that compared to TD youth, adolescents with ASD show a more blunted cortisol stress response to the TSST (Edmiston et al., 2017). Since an estimated 80% of people exhibit a robust response to social threat (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004), the reduced reactivity to the TSST appears maladaptive. Indeed, it has been shown that non-responsive patterns have been linked to early adverse life stress (Elzinga et al., 2008) and panic disorder (Petrowski et al., 2010). While such conditions do not have a direct association with ASD, the diminished cortisol response profile warrants further study to determine underlying factors that contribute to it.

The different cortisol trajectories in the ASD samples may be attributed to developmental differences and experience. Alternatively, the explanation may rest directly within the disorder itself, a condition marked by primary impairment in social awareness and motivation (APA, 2013). While social evaluative threat has been shown to be a potent activator of the HPA axis (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004), it rests on the premise of an inherent social drive to want to perform well and not be negatively evaluated by others. The social motivation theory of ASD has characterized ASD as a disorder of diminished social interest (Chevallier et al., 2012), which may dampen the extent to which some individuals with ASD respond to the conditions of the TSST. It is also plausible that the reduced social cognitive abilities, such as poor recognition of facial information and expression (e.g. (Dawson et al., 2002)), may result in many of the adolescents with ASD not perceiving the rater’s lack of positive affect and thereby the task is not deemed threatening (Edmiston et al., 2017). In the first explanation, there is a limited need to be perceived favorably by others, and in the second, there is a lack of awareness that social judgment by others is occurring.

In a follow-up analysis, it was shown that adolescents and adults with more autism symptoms had a longer return to pre-stress levels. While there were no associations with anticipatory or reactivity to the stressor, a longer trajectory following the stressor suggests diminished physiological recovery and perhaps poorer adaptation to stressful situations.

Based on the preexisting literature showing developmental differences in regards to the functioning of the HPA axis in ASD, especially in response to the TSST (Corbett et al., 2012, Edmiston et al., 2017, Lanni et al., 2012, Levine et al., 2012), and the deleterious role stress may play in psychological, physical and social well-being, the current study was undertaken. Strengths of the study include consistent diagnostic, assessment, protocol, and stress induction procedures and personnel for both age groups during the course of the same two-year period. Moreover, symptom profile and cognitive level of functioning for the groups were comparable. Nevertheless, the study has five primary limitations, including the enrollment of a relatively small sample. Secondly, even though the labs are both well established, samples were assayed at two different labs. Because there were no baseline differences in the home samples, the findings showing differences between the groups appear to be in response to the stressor rather than simply differences in methodology. Further, the major analytic technique used in this manuscript (multi-level modeling) tests for differences in within-person change, which is more robust to between-group differences that could result from the assays. Thirdly, beyond autism symptoms, we did not assess other potential modulatory factors across both groups, which may have been highly informative. Fourth, the study would have benefitted from the inclusion of an age-and gender-matched neurotypical group of developing adolescents and adults for comparsion to examine potential modulatory factors. Finally, the assessment of perceived stress collected via self-report was not obtained and could have provided some insight into the subjective experience of the participants during social evaluative threat and relationship to physiological stress.

Future Directions

The current study only included adolescents and adults with ASD; future research should also include a direct comparison to age-matched groups with typical development. The inclusion of equal numbers of female participants is warranted to elucidate the well-established gender differences in TD samples (e.g. (Reschke-Hernandez et al., 2017)) and in those with ASD (Edmiston et al., 2017, Sharpley et al., 2016). Even though stable associations between physiological and psychological measures have been challenging (e.g. (Cohen et al., 2000)) and often reflect dissociations between these indices, it may be worth investigating potential associations between anticipatory and stress reactivity cortisol compared to subjective psychological measures in persons with ASD. The neuroendocrine cascade is influenced by a complex array of independent factors, such as age, sex (e.g. (Bale and Epperson, 2015)) and cognitive appraisal (e.g. (Kudielka et al., 2007)); therefore, studying such factors may shed light on our understanding of ASD. Examination of these and other factors such as specific domains of autism symptoms or IQ may help to differentiate responders from non-responders. Finally, while considerable research has been conducted on the diurnal regulation of cortisol in children with ASD (e.g. (Tomarken et al., 2015)), future research should investigate the diurnal rhythm of salivary cortisol and its developmental trajectory in regards to children, adolescents and young adults with and without ASD.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current study makes a unique contribution to the literature by emphasizing developmental differences in adults versus adolescents with ASD. Specifically, adults with ASD showed notable anticipatory and sustained reactive stress in response to social evaluative threat, whereas the adolescent group had a more reactive response pattern. In both groups, however, the majority of individuals evidenced a blunted cortisol response profile. Further research is needed to determine if such patterns are adaptive or deleterious, and to determine underlying factors that may contribute to the distinct and diminished stress profiles.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements and Funding

The authors thank the Vanderbilt Hormone Assay and Analytical Core (supported by DK059637 and DK020593) for completion of the cortisol assays.

This study was funded by NIMH R01 MH085717 awarded to BAC and NIMH K01 MH092598 awarded to JLT, with core support from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (U54 HD083211, PI: Neul) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (CTSA UL1 TR000445). None of the funding sources was involved in the study design, collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- ACHENBACH TM 2001. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles, Burlington, VT, University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- ACHENBACH TM 2003. Manual for the ASEBA Adult Forms & Profiles, Burlington, VT, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- APA 2013. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), Washinton, D.C., American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- BALE TL & EPPERSON CN 2015. Sex differences and stress across the lifespan. Nat Neurosci, 18, 1413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BISHOP-FITZPATRICK L, MINSHEW NJ, MAZEFSKY CA & EACK SM 2017. Perception of Life as Stressful, Not Biological Response to Stress, is Associated with Greater Social Disability in Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BREMNER JD, VYTHILINGAM M, VERMETTEN E, ADIL J, KHAN S, NAZEER A, AFZAL N, MCGLASHAN T, ELZINGA B, ANDERSON GM, HENINGER G, SOUTHWICK SM & CHARNEY DS 2003. Cortisol response to a cognitive stress challenge in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) related to childhood abuse. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 28, 733–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEVALLIER C, KOHLS G, TROIANI V, BRODKIN ES & SCHULTZ RT 2012. The social motivation theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci, 16, 231–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN S, HAMRICK N, RODDRIGUEZ MS, FELDMAN PJ, RABIN BS & MANUCK SB 2000. The stability of and intercorrelations among cardiovascular, immune, endocrine, and psychological reactivity. Annals of Psychosomatic Medicine, 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONSTANTINO JN & GRUBER CP 2012. The Social Responsiveness Scale Manual, Second Edition (SRS-2), Los Angeles, CA, Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- CORBETT BA & SCHUPP CW 2014. The Cortisol Awakening Response (CAR) in Male Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Horm Behav. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORBETT BA, SCHUPP CW & LANNI KE 2012. Comparing biobehavioral profiles across two social stress paradigms in children with and without autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism, 3, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORBETT BA, SCHUPP CW, SIMON D, RYAN N & MENDOZA S 2010. Elevated cortisol during play is associated with age and social engagement in children with autism. Mol Autism, 1, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORBETT BA, SWAIN DM, NEWSOM C, WANG L, SONG Y & EDGERTON D 2014. Biobehavioral profiles of arousal and social motivation in autism spectrum disorders. J Child Psychol Psychiatry, 55, 924–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAWSON G, CARVER L, MELTZOFF AN, PANAGIOTIDES H, MCPARTLAND J & WEBB SJ 2002. Neural correlates of face and object recognition in young children with autism spectrum disorder, developmental delay, and typical development. Child Dev, 73, 700–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE TIMARY P, ROY E, LUMINET O, FILLEE C & MIKOLAJCZAK M 2008. Relationship between alexithymia, alexithymia factors and salivary cortisol in men exposed to a social stress test. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33, 1160–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DICKERSON SS & KEMENY ME 2004. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull, 130, 355–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EDMISTON EK, BLAIN SD & CORBETT BA 2017. Salivary cortisol and behavioral response to social evaluative threat in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Res, 10, 346–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ELZINGA BM, ROELOFS K, TOLLENAAR MS, BAKVIS P, VAN PELT J & SPINHOVEN P 2008. Diminished cortisol responses to psychosocial stress associated with lifetime adverse events - A study among healthy young subjects. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33, 227–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ENGERT V, EFANOV SI, DUCHESNE A, VOGEL S, CORBO V & PRUESSNER JC 2013. Differentiating anticipatory from reactive cortisol responses to psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38, 1328–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOLDMAN SE, ALDER ML, BURGESS HJ, CORBETT BA, HUNDLEY R, WOFFORD D, FAWKES DB, WANG L, LAUDENSLAGER ML & MALOW BA 2017. Characterizing Sleep in Adolescents and Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANGER DA, HIBEL LC, FORTUNATO CK & KAPELEWSKI CH 2009. Medication effects on salivary cortisol: tactics and strategy to minimize impact in behavioral and developmental science. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34, 1437–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GUNNAR MR, WEWERKA S, FRENN K, LONG JD & GRIGGS C 2009. Developmental changes in hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal activity over the transition to adolescence: normative changes and associations with puberty. Dev Psychopathol, 21, 69–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HEIM C, EHLERT U & HELLHAMMER DH 2000. The potential role of hypocortisolism in the pathophysiology of stress-related bodily disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 25, 1–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HERBISON CE, HENLEY D, MARSH J, ATKINSON H, NEWNHAM JP, MATTHEWS SG, LYE SJ & PENNELL CE 2016. Characterization and novel analyses of acute stress response patterns in a population-based cohort of young adults: influence of gender, smoking, and BMI. Stress, 19, 139–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOSHINO Y, OHNO Y, MURATA S, YOKOYAMA F, KANEKO M & KUMASHIRO H 1984. Dexamethasone suppression test in autistic children. Folia Psychiatr Neurol Jpn, 38, 445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSEN LM, GISPEN-DE WIED CC, VAN DER GAAG RJ, TEN HOVE F, WILLEMSEN-SWINKELS SW, HARTEVELD E & VAN ENGELAND H 2000. Unresponsiveness to psychosocial stress in a subgroup of autistic-like children, multiple complex developmental disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 25, 753–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSEN LM, GISPEN-DE WIED CC, WIEGANT VM, WESTENBERG HG, LAHUIS BE & VAN ENGELAND H 2006. Autonomic and neuroendocrine responses to a psychosocial stressor in adults with autistic spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord, 36, 891–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JUSTER RP, PERNA A, MARIN MF, SINDI S & LUPIEN SJ 2012. Timing is everything: Anticipatory stress dynamics among cortisol and blood pressure reactivity and recovery in healthy adults. Stress-the International Journal on the Biology of Stress, 15, 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIRSCHBAUM C & HELLHAMMER DH 2000. Salivary cortisol In: FINK G. (ed.) Encyclopedia of Stress San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- KIRSCHBAUM C, PIRKE KM & HELLHAMMER DH 1993. The ‘Trier Social Stress Test’--a tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28, 76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUDIELKA BM, BUSKE-KIRSCHBAUM A, HELLHAMMER DH & KIRSCHBAUM C 2004. HPA axis responses to laboratory psychosocial stress in healthy elderly adults, younger adults, and children: impact of age and gender. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 29, 83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUDIELKA BM, HEILHAMMER DH & KIRSCHBAUM C 2007. Ten years of reserch with the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST) - Revisited In: HARMON-JONES EAPW,P (ed.) Social neuroscience: integrating biological and psychological explanations of social behavior. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- KUMAZAKI H, WARREN Z, CORBETT BA, YOSHIKAWA Y, MATSUMOTO Y, HIGASHIDA H, YUHI T, IKEDA T, ISHIGURO H & KIKUCHI M 2017. Android Robot-Mediated Mock Job Interview Sessions for Young Adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Pilot Study. Front Psychiatry, 8, 169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LANNI KE, SCHUPP CW, SIMON D & CORBETT BA 2012. Verbal ability, social stress, and anxiety in children with Autistic Disorder. Autism, 16, 123–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LAZARUS R & FOLKMAN S 1984. Stress, appraisal, and coping, New York, Springer Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- LEVINE TP, SHEINKOPF SJ, PESCOSOLIDO M, RODINO A, ELIA G & LESTER B 2012. Physiologic Arousal to Social Stress in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders: A Pilot Study. Res Autism Spectr Disord, 6, 177–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOPATA C, VOLKER MA, PUTNAM SK, THOMEER ML & NIDA RE 2008. Effect of social familiarity on salivary cortisol and self-reports of social anxiety and stress in children with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord, 38, 1866–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LORD C, RISI S, LAMBRECHT L, COOK EH JR., LEVENTHAL BL, DILAVORE PC, PICKLES A & RUTTER M 2000. The autism diagnostic observation schedule-generic: a standard measure of social and communication deficits associated with the spectrum of autism. J Autism Dev Disord, 30, 205–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOVALLO WR & GERIN W 2003. Psychophysiological reactivity: mechanisms and pathways to cardiovascular disease. Psychosom Med, 65, 36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LUPIEN SJ, MCEWEN BS, GUNNAR MR & HEIM C 2009. Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci, 10, 434–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MASON JW 1968. A review of psychoendocrine research on the pituitary-adrenal cortical system. Psychosom Med, 30, Suppl:576–607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIR I, MEIR D, ZILBER N, KNOBLER H, HADJEZ J & LERNER Y 1995. Brief report: circadian melatonin, thyroid-stimulating hormone, prolactin, and cortisol levels in serum of young adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord, 25, 641–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETROWSKI K, HEROLD U, JORASCHKY P, WITTCHEN HU & KIRSCHBAUM C 2010. A striking pattern of cortisol non-responsiveness to psychosocial stress in patients with panic disorder with concurrent normal cortisol awakening responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35, 414–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAUDENBUSH SW & BRYK AS 2002. Hierarchical linear models : applications and data analysis methods Thousand Oaks, CA, Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- RESCHKE-HERNANDEZ AE, OKERSTROM KL, BOWLES EDWARDS A & TRANEL D 2017. Sex and stress: Men and women show different cortisol responses to psychological stress induced by the Trier social stress test and the Iowa singing social stress test. J Neurosci Res, 95, 106–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROID GH 2003. Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scale 5, Itasca, Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- SCHOOMER NC, HELLHAMMER DH & KIRSCHBAUM C 2003. Dissociation between reactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary system to repeated psychosocial stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHUPP CW, SIMON D & CORBETT BA 2013. Cortisol Responsivity Differences in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders During Free and Cooperative Play. J Autism Dev Disord. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHARPLEY CF, BITSIKA V, ANDRONICOS NM & AGNEW LL 2016. Further evidence of HPA-axis dysregulation and its correlation with depression in Autism Spectrum Disorders: Data from girls. Physiol Behav, 167, 110–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SINGER JD & WILLETT JB 2003. Applied longitudinal data analysis : Modeling change and event occurrence, New York, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- SMEEKENS I, DIDDEN R & VERHOEVEN EW 2015. Exploring the relationship of autonomic and endocrine activity with social functioning in adults with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord, 45, 495–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TANI P, LINDBERG N, MATTO V, APPELBERG B, NIEMINEN-VON WENDT T, VON WENDT L & PORKKA-HEISKANEN T 2005. Higher plasma ACTH levels in adults with Asperger syndrome. J Psychosom Res, 58, 533–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAYLOR JL & CORBETT BA 2014. A review of rhythm and responsiveness of cortisol in individuals with autism spectrum disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 49C, 207–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOMARKEN AJ, HAN GT & CORBETT BA 2015. Temporal patterns, heterogeneity, and stability of diurnal cortisol rhythms in children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 62, 217–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN CAUTER E & REFETOFF S 1985. Evidence for two subtypes of Cushing’s diseae based on the analysis of episodic cortisol secretion. New England Journal of Medicine, 312, 1343–1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WECHSLER D 1999. Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence, San Antonio, TX, Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.