Abstract

Background

Thioridazine is an antipsychotic that can still be used for schizophrenia although it is associated with the cardiac arrhythmia, torsades de pointe.

Objectives

To review the effects of thioridazine for people with schizophrenia.

Search methods

For this 2006 update, we searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (June 2006).

Selection criteria

We included all randomised clinical trials comparing thioridazine with other treatments for people with schizophrenia or other psychoses.

Data collection and analysis

We reliably selected, quality rated and extracted data from relevant studies. For dichotomous data, we estimated relative risks (RR), with the 95% confidence intervals (CI). Where possible, we calculated the number needed to treat/harm statistic (NNT/H) on an intention‐to‐treat basis.

Main results

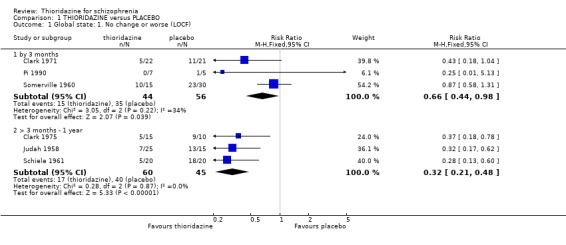

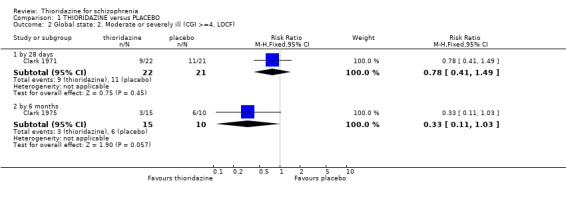

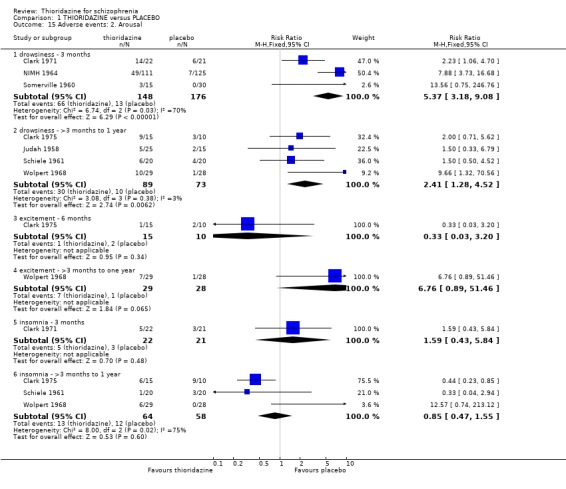

This review currently includes 42 RCTs with 3498 participants. When thioridazine was compared with placebo (total n=668, 14 RCTs) we found global state outcomes favoured thioridazine (n=105, 3 RCTs, RR 'no change or worse' by 6 months 0.33 CI 0.2 to 0.5, NNT of 2 CI 2 to 3). Thioridazine is sedating (n=324, 3 RCTs, RR 5.37 CI 3.2 to 9.1, NNH 4 CI 2 to 74). Generally, thioridazine did not cause more movement disorders than placebo.

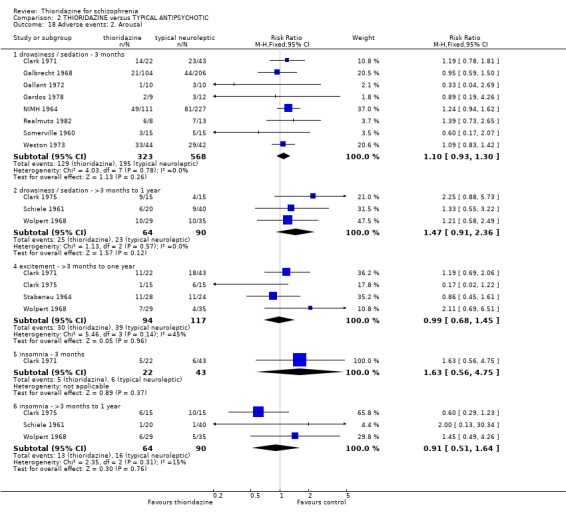

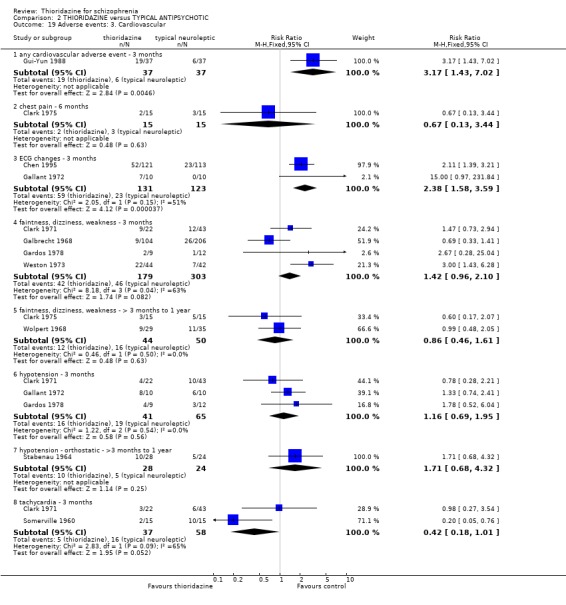

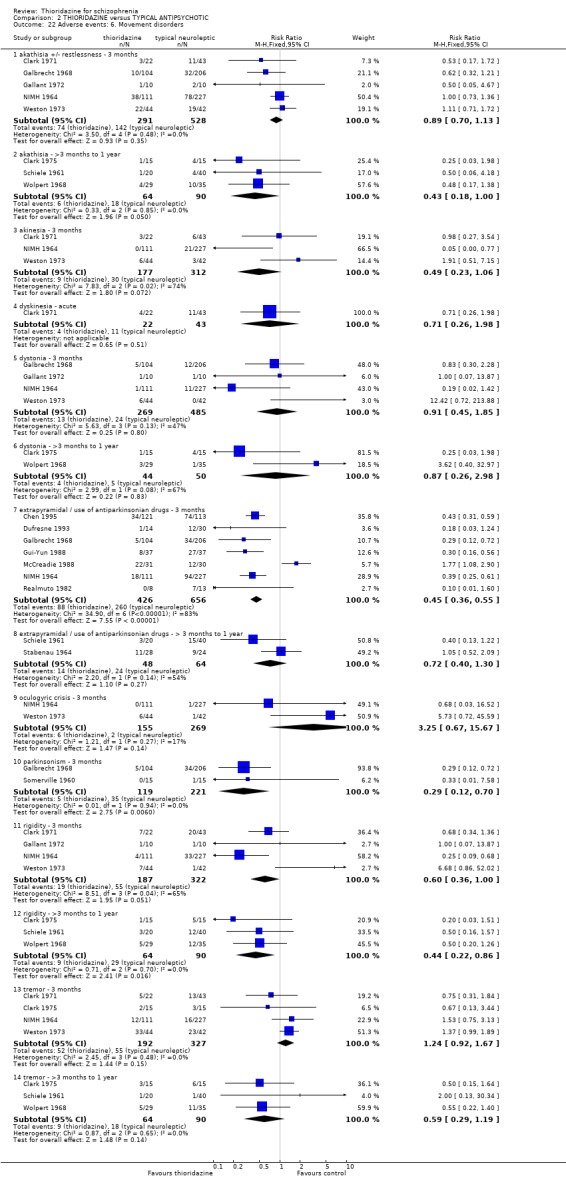

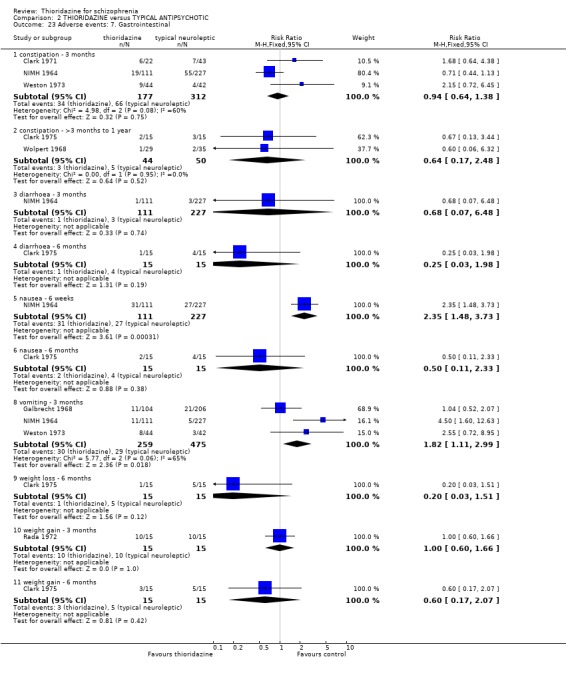

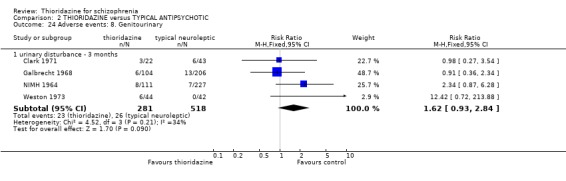

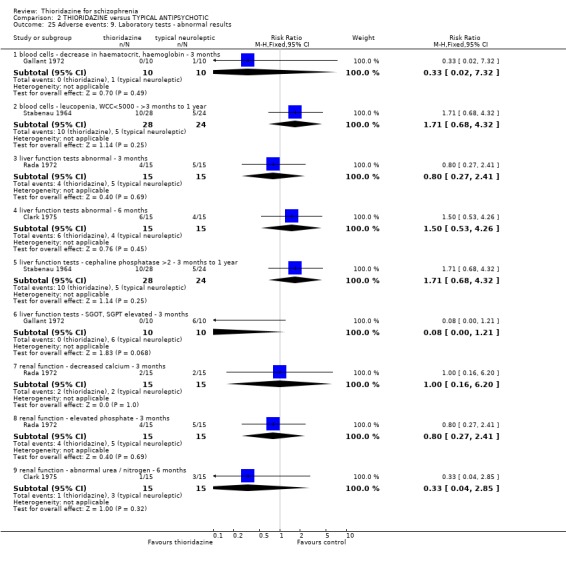

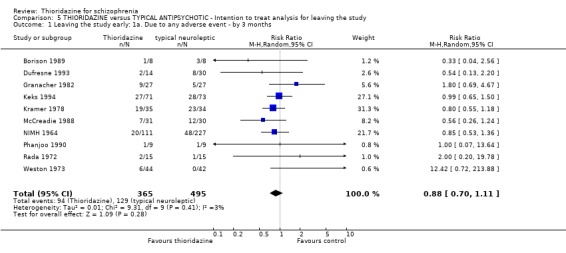

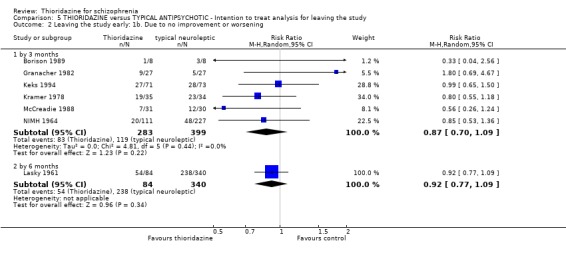

Twenty‐seven studies (total n=2598) compared thioridazine with typical antipsychotics. We found no significant difference in global state (n=743, 11 RCTs, RR no short‐term change or worse 0.98 CI 0.8 to 1.2) and medium‐term assessments (n=142, 3 RCTs, RR 0.99, CI 0.6 to 1.6). We found no significant differences in the number of people leaving the study early 'for any reason' (short‐term, n=1587, 19 RCTs, RR 1.07 CI 0.9 to 1.3). Extrapyramidal adverse events lower for those allocated to thioridazine (n=1082, 7 RCTs, RR use of antiparkinsonian drugs 0.45 CI 0.4 to 0.6). Thioridazine did seem associated with cardiac adverse effects (n=74, 1 RCT, RR 'any cardiovascular adverse event' 3.17 CI 1.4 to 7.0, NNH 3 CI 2 to 5). Electrocardiogram changes were significantly more frequent in the thioridazine group (n=254, 2 RCTs, RR 2.38, CI 1.6 to 3.6, NNH 4 CI 3 to 10).

Six RCTs (total n=344) randomised thioridazine against atypical antipsychotics. Global state rating did not reveal any short‐term difference between thioridazine and remoxipride and sulpiride (n=203, RR not improved or worse 1.00 CI 0.8 to 1.3). Limited data did not highlight differences in adverse event profiles.

Authors' conclusions

Although there are shortcomings, there appears to be enough consistency over different outcomes and periods to confirm that thioridazine is an antipsychotic of similar efficacy to other commonly used antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia. Its adverse events profile is similar to that of other drugs, but it may have a lower level of extrapyramidal problems and higher level of ECG changes. We would advocate the use of alternative drugs, but if its use in unavoidable, cardiac monitoring is justified.

Keywords: Humans; Antipsychotic Agents; Antipsychotic Agents/adverse effects; Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use; Arrhythmias, Cardiac; Arrhythmias, Cardiac/chemically induced; Outcome Assessment (Health Care); Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Schizophrenia; Schizophrenia/drug therapy; Thioridazine; Thioridazine/adverse effects; Thioridazine/therapeutic use; Treatment Outcome

Thioridazine for schizophrenia

About 1% of people will get schizophrenia and it often begins early in life. Schizophrenia is typically characterised by hallucinations (perceptions without a cause), delusions (fixed and false beliefs), disordered thinking, and emotional withdrawal. The outcomes vary, but antipsychotic drugs generally help; thioridazine is one such drug. It had been thought to be effective and less prone to cause the movement disorders that can happen particularly with the older generation antipsychotics. Largely thioridazine has been withdrawn due to its links with abnormal heart rhythm but is still used in special circumstances.

We reviewed the effects of thioridazine and found many trials suggesting that it seems to be as effective as other commonly used antipsychotics for people with schizophrenia, but also justification for guidelines encouraging heart monitoring for people prescribed this drug. Where possible, we would advocate choosing other drugs in place of thioridizine.

Background

Thioridazine (Melleril/Mellaril) is a piperidine phenothiazine similar to chlorpromazine that is taken by mouth and was developed and tested soon after chlorpromazine in the 1950s (Bain 1998). In an early, important study thioridazine was found to have similar efficacy to chlorpromazine for treating people with schizophrenia (NIMH 1964) at least in terms of the 'positive' symptoms (delusions, strongly held abnormal beliefs not explainable by the person's culture, and hallucinations, abnormal perceptions).

Thioridazine has often been considered the drug of choice in the elderly because of its lower level of extrapyramidal adverse events (such as tremor, muscle stiffness, and slow body movements) and sedation (BNF 1998). However, it may be more likely to cause cognitive adverse events in the elderly, such as delirium or worsening of memory (Moreau 1986). There is also a risk of cardiotoxicity especially in combination with a tricyclic antidepressant (BNF 1998, Heiman 1977, Lipscomb 1980) and it is also more likely to cause a fall in blood pressure than other drugs. On rare occasions, thioridazine has caused pigmentary retinopathy (leading to seeing the colour brown, blurring and loss of acuity) with doses above 1000 mg/day (Rennie 1993). A dose maximum of 800 mg/day was previously recommended (BNF 1998) together with eye examination during prolonged use. In 2000, the Committee on the Safety of Medicines advised that thioridazine's use should be restricted to second‐line treatment of schizophrenia because of rare but serious cardiotoxicity; in particular, QTc prolongation and potentially life threatening ventricular arrhythmias (MHRA). In 2005, Novartis voluntarily withdrew thioridazine from the market following safety concerns. Following this, the MHRA withdrew the UK license for thioridazine, but the drug may still be imported on an unlicensed basis under the generic name Thioridazine (Neuraxpharma).

Technical background (+/‐)‐10‐[2‐(1‐methyl‐2‐piperidyl)ethyl]‐2‐(methylthio) phenothiazine (hydrochloride) or thioridazine has a higher level of cholinergic receptor binding action than chlorpromazine which may account for its higher level of cognitive and cardiac adverse events. This is also probably the reason for its lower level of extrapyramidal adverse events. Its cardiac adverse event profile is also related to a prolongation of the QT interval of the ECG (Hollister 1995, Drolet 1999) and torsades de pointes which is a ventricular arrhythmia (Roden 1993). Because of this thioridazine has been associated with mortality in overdose (Annane 1996, Buckley 1995).

Thioridazine is claimed to have a higher degree of limbic selectivity (Borison 1983, King 1995, Seeman 1983). This means it may be more selective for binding receptors in the mesolimbic dopamine system at the base of the brain. A receptor is a protein that binds a chemical messenger (neurotransmitter) such as dopamine or acetylcholine. Drugs also bind to receptors when exerting their action. These limbic dopamine receptors may be more closely involved in the symptom development of schizophrenia. Like chlorpromazine it binds to dopamine receptors, responsible for its therapeutic effect, but is not selective for D2 receptors like haloperidol (Assie 1993, Bowers 1975, Sedvall 1995). It similarly binds to different receptors such as those for serotonin, noradrenaline and histamine neurotransmitters (King 1995). This may give it a broad range of effects including adverse events, for example, binding to histamine receptors causes sedation.

Thioridazine is usually considered a 'typical' antipsychotic, i.e. the older generation of antipsychotic first developed in the 1950s. However, because it is reputed to cause fewer extrapyramidal adverse events, some authorities have classified it as an 'atypical' i.e. akin to the newer generation of antipsychotics developed in the 1990's which are also thought to have a lower propensity to cause extrapyramidal adverse events (King 1995, Trevitt 1998)

Objectives

To review the effects of thioridazine for people with schizophrenia in comparison with antipsychotics, placebo, or no treatment.

A secondary objective was to examine the effects of thioridazine for elderly people with schizophrenia.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We sought all relevant randomised controlled trials. Where trials were described as 'double‐blind', but only implied that they were randomised, they were included in a sensitivity analysis. If we found no substantive difference within primary outcomes (see types of outcome measures) when these 'implied randomisation' studies were added, then we included these in the final analysis. If a substantive difference was found we only used trials that were clearly randomised and the results of the sensitivity analysis were described. We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by using alternate days of the week.

Types of participants

We included people with schizophrenia, however diagnosed. Those with 'serious/chronic mental illness' or 'psychotic illness' were also included. If possible, we excluded people with schizoaffective disorder, dementing illnesses, depression and primarily problems associated with substance misuse.

Types of interventions

1. Thioridazine: any dose 2. Placebo. 3. Any other antipsychotic agent, divided into the atypical (amisulpiride, clozapine, loxapine, molindone, olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, sertindole, zotepine) and the typical antipsychotics (chlorpromazine, haloperidol etc).

We excluded unlicensed compounds where they did not appear to be of established efficacy.

Types of outcome measures

As schizophrenia is often a life‐long illness and thioridazine is used as an ongoing treatment, we grouped outcomes according to time periods: short‐term (up to 12 weeks), medium‐term (13 weeks up to one year) and long‐term (more than one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Service utilisation outcomes 1.1 Hospital admission

2. Clinical response 2.1 Relapse

2.2 Clinically significant response in global state ‐ as defined by each of the studies

3. Extrapyramidal side effects 3.1 Incidence of use of antiparkinson drugs

4. Other adverse effects, general and specific 4.1 Cardiac effects

Secondary outcomes

1. Death: suicide or natural causes

2. Service utilisation outcomes 2.1 Days in hospital 2.2 Change in hospital status

3. Clinical response 3.1 Average score/change in global state 3.2 Clinically significant response in mental state ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.3 Average score/change in mental state 3.4 Clinically significant response on positive symptoms ‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.5 Average score/change in positive symptoms 3.6 Clinically significant response on negative symptoms‐ as defined by each of the studies 3.7 Average score/change in negative symptoms

4. Leaving the study early.

5. Behaviour 5.1 Clinically significant response in behaviour ‐ as defined by each of the studies 5.2 Average score/change in behaviour

6. Extrapyramidal side effects 6.1 Clinically significant extrapyramidal side effects ‐ as defined by each of the studies 6.2 Average score/change in extrapyramidal side effects

7. Other adverse effects, general and specific 7.1 Number of people dropping out due to adverse affects 7.2 Anticholinergic effects 7.3 Antihistamine effects 7.4 Prolactin related symptoms

8. Social functioning 8.1 Clinically significant response in social functioning ‐ as defined by each of the studies 8.2 Average score/change in social functioning

9. Economic outcomes

10. Quality of life/satisfaction with care for either recipients of care or carers 10.1 Significant change in quality of life/satisfaction ‐ as defined by each of the studies 10.2 Average score/change in quality of life/ satisfaction 10.3 Employment status

11. Cognitive functioning

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (June 2006) using the phrase:

[(thioridazin* or tioridazin* or thioridazide* or thioridacin* or sonapax* or mallorol* or malloryl* or meleril* or mellaril* or melleril* or melleret* or melleryl* in REFERENCES) Title, Abstract and Index term fields OR (thioridazin* in STUDY interventions field)]

This register is compiled by systematic searches of major databases, hand searches and conference proceedings (see Group Module).

2. Details of previous electronic searches 2.1. We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (January 2002) using the phrase:

(thioridazine‐phrase) or #42=571 or #42=50 or#42=227]

(#42 is the field in the Register where each intervention is coded. 571 is thioridazine and 50 and 227 are Melleril)

2.2. We searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Register (September 2002) using the phrase:

[((*Meleril* or *Mellaril* or *Melleril* or *Melleryl* or *Melleretten* or *Mallorol* or *Elperil* or *Flaracantyl* or *Mefurine* or *Orsanil* or *Ridazine* or *Sonapax* or *Stalleril* or *Tirodil* or *Visergil*) in title, abstract or index terms of REFERENCE) or (Thioridazine in interventions of STUDY)]

2.3. We searched Biological Abstracts (January 1982 to September 2002) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for randomised controlled trials and for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with:

[and (thioridazine‐phrase)]

2.4. We searched CINAHL (January 1982 to September 2002) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for randomised controlled trials and for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with:

[and (thioridazine‐phrase)]

2.5. We searched the Cochrane Library (Issue 3, 2002) using the phrase:

[(thioridazine‐phrase) or THIORIDAZINE/explode in MeSH]

2.6. We searched EMBASE (January 1980 to September 2002) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for randomised controlled trials and for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with:

[and ((thioridazine‐phrase) or explode THIORIDAZINE / all)]

2.7. We searched MEDLINE (January 1966 to September 2002) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for randomised controlled trials and for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with:

[and ((thioridazine‐phrase) or THIORIDAZINE / explode in MeSH)]

2.8. We searched PsycLIT (January 1974 to September 1999) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for randomised controlled trials and for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with:

[and ((thioridazine‐phrase) or THIORIDAZINE / explode in MeSH)]

2.9. We searched Sociofile (January 1974 to September 2002) using the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's phrase for randomised controlled trials and for schizophrenia (see Group search strategy) combined with:

[and (thioridazine‐phrase)]

Searching other resources

1. Reference searching We also inspected the references of all identified studies for more studies.

2. Personal contact We contacted the first author of each included study for information regarding unpublished trials.

3. Drug company We contacted the manufacturers of proprietary thioridazine (Novartis) for additional data.

Data collection and analysis

1. Study selection For the earlier version of the review (AS) inspected all citations from the search results. MF re‐inspected a random sample (10%) of reports in order to ensure selection reliability. Potentially relevant abstracts were identified and full papers ordered and reassessed for inclusion and methodological quality. Where disagreements arose we attempted resolution by discussion, or acquired further information from the authors of trials. If doubt remained we did not include the study and added it to the list of those awaiting assessment, pending further information. For the update (2006) we (MF and JR) inspected and selected all study citations identified by the search. Where disagreement arose, this was resolved by discussion, or where doubt remained, we acquired the full article for further inspection.

2. Assessment of methodological quality We assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2005) and the Jadad Scale (Jadad 1996). The former is based on the evidence of a strong relationship between allocation concealment and direction of effect (Schulz 1995). The categories are defined below:

A. Low risk of bias (adequate allocation concealment) B. Moderate risk of bias (some doubt about the results) C. High risk of bias (inadequate allocation concealment). For the purpose of the analysis in this review, trials were included if they met the Cochrane Handbook criteria A or B.

The Jadad Scale measures a wider range of factors that impact on the quality of a trial. The scale includes three items:

1. Was the study described as randomised? 2. Was the study described as double‐blind? 3. Was there a description of withdrawals and drop outs?

Each item receives one point if the answer is positive. In addition, a point can be deducted if either the randomisation or the blinding/masking procedures described are inadequate. For this review we used a cut‐off of two points on the Jadad scale to check the assessment made by the Handbook criteria. However, we did not use the Jadad Scale to exclude trials.

3. Data management 3.1 Data extraction Originally (AS) independently extracted data from the included trials and a random 10% sample was checked by (JR) for accuracy. We discussed any disagreements, documented decisions and, where necessary, we contacted authors of trials for clarification. When this was not possible, we did not enter data and added the studies to the list of those awaiting assessment. For the 2006 update we (MF and JR) independently extracted data and any disagreements were resolved through discussion, where this was not possible we contacted authors for further information.

4. Data synthesis Data types: Outcomes are assessed using continuous (for example, average changes on a behaviour scale), or dichotomous measures (for example, either 'no important changes' or 'important changes' in a person's behaviour). Categorical data (for example, one of three categories on a behaviour scale, such as 'little change', 'moderate change' or 'much change' are currently not supported by RevMan software so they were dichotomised where possible (see below).

4.1 Dichotomous data Where the original authors of the studies gave outcomes such as 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved' based on their clinical judgement, predetermined criteria or any scale this was recorded in RevMan. If data were from a rater not clearly stated to be independent then it was included if it did not change the results, otherwise it was presented separately with a label 'prone to bias'. Where possible, efforts were made to convert relevant categorical or continuous outcome measures to dichotomous data by identifying cut off points on rating scales and dividing subjects accordingly into groups. This was with the cut off points 'moderate or severe impairment' for end of study data or 'no better or worse' for change data wherever possible.

4.1.1 Summary statistic: for dichotomous outcomes we calculated the relative risk (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI) using a fixed effects model. If heterogeneity was found (see section 5) we used a random effects model. We also calculated the number needed to treat/harm statistic (NNT/H) when outcomes were statistically significant.

4.2 Continuous data 4.2.1 Normal data Continuous scale derived data if often not normally distributed. To avoid the pitfall of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data the following standards were applied to continuous endpoint data: (a) Standard deviations and means were reported in the paper or were obtainable from the authors; (b) The standard deviation (SD), when multiplied by 2 was less than the mean (as otherwise the mean was unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution) (Altman 1996). Data that did not meet the first or second standard were not analysed in RevMan software, but were entered into other data tables and reported as skewed data in the results section. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and endpoint and this rule can be applied to them. If a scale starts from a positive value (such as PANSS, which can have values from 30‐210) the calculation described above in (b) should be modified to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases skew is present if 2SD>(S‐Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score.

4.2.2 Endpoint versus change data: endpoint scale‐derived data are finite, ranging from one score to another. Change data (endpoint minus baseline) are more problematic and in the absence of individual patient data it is impossible to know if data are skewed, though this is likely. After consulting the ALLSTAT electronic statistics mailing list, we presented change data in MetaView in order to summarise available information. In doing this, it was assumed either that data were not skewed or that the analyses could cope with the unknown degree of skew. Where possible we presented endpoint data, and if both endpoint and change data were available for the same outcomes, then we reported only the former.

4.2.3 Summary statistic: for continuous outcomes we estimated a weighted mean difference (WMD) fixed effect model between groups. Again, if heterogeneity was found (see section 5) we used a random effects model.

4.3 Intention to treat data We excluded data from studies where more than 40% of participants in any group were lost to follow up (this does not include the outcome of 'leaving the study early'). In studies with less than 40% dropout rate, we considered people leaving the study early to have had the negative outcome, except for the event of death.

4.4 Scale derived data Unpublished scales are known to be subject to bias in trials of treatments for schizophrenia (Marshall 2000). Therefore we only included continuous data from rating scales if the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal.

In many included studies in this review it was unclear that scale based data were rated independently of treatment (see Included studies tables) so we presented the data with a label 'prone to bias'.

4.5 Cluster trials Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. Firstly, authors often fail to account for intra class correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992) whereby p values are spuriously low, confidence intervals unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997, Gulliford 1999).

Where clustering was not accounted for in primary studies, we presented the data in a table, with a (*) symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. In subsequent versions of this review we will seek to contact first authors of studies to obtain intra‐class correlation co‐efficients of their clustered data and to adjust for this using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering has been incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we will also present these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but will adjust them for the clustering effect.

We have sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the intraclass correlation co‐efficient (ICC) [Design effect = 1+(m‐1)*ICC] (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported it was assumed to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

5. Test for heterogeneity Firstly, we considered all the included studies within any comparison to judge clinical heterogeneity. Then we visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity. This was supplemented, primarily, by employing the I‐squared statistic. This provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance. Where the I‐squared estimate was equal to, or greater than 75%, this was interpreted as evidence of high levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2003). In such cases, we sought to remove outlying trial(s) and perform and report sensitivity analyses both with and without these outlying trials. Where no obvious outlying trial(s) could be identified we analysed and reported the result using a random effects model, which takes into account that the effects being estimated are not identical.

6. Assessing the presence of publication bias Data from all included trials were entered into a funnel graph (trial effect versus trial size or 'precision') in an attempt to investigate the likelihood of overt publication bias. Where only 3‐4 studies reported an outcome or there was little variety in sample size (or precision estimate) between studies ‐ funnel plot analysis was not appropriate. There is currently no consensus about the validity of formal statistical tests to investigate funnel plot asymmetry, one test, proposed by Egger 1997 has been subject to criticism (Stuck 1998). Further versions of this review will include such tests when their validity has been proven.

7. Sensitivity analyses 7.1 Outcomes for intention‐to‐treat analysis were compared with completer analysis. Where there were differences these were either reported or presented graphically. 7.2 Results for the elderly with schizophrenia were to be analysed separately and compared with the results for younger trial participants (cut‐off of age 65 where possible) however this was not possible (see below).

8. General Where possible, we entered data into RevMan so the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for thioridazine.

Results

Description of studies

1. Excluded studies We excluded 87 studies, details of which are in the 'Excluded studies' table. Most were excluded due to being non‐randomised studies. We excluded more than 20 studies because of irrelevant interventions. The remainder had to be excluded because we could find no usable data. For example, in several there were no outcomes reported, or in the crossover studies there were no data from the first pre‐crossover stage. We were unable to include the most recent study we found, Mahmoud 2004, as no reported data were available from the thioridazine arm when tit was compared with risperidone.

2. Awaiting assessment One Japanese study (Tanimukai 1973) is awaiting translation.

3. Ongoing studies We are not aware of any ongoing studies.

4. Included Studies During the 2006 update we found four 'new' studies to include (Carranza 1974, Ju 1997, Schiele 1961, Zhang 1999), and three further reports of trials already included in the review, one of which provided additional data (Liu 1994). A total of 42 studies are included.

4.1 Length of trials Study durations ranged from 28 days to 40 months. Most studies (n=30) were short‐term evaluations (up to 12 weeks), although ten were of intermediate duration (13 weeks to one year) and two were longer‐term trials (Grinspoon 1967 24 months, Rasmussen1976 40 months).

4.2 Participants A total of 3498 people have participated in the 42 trials, most of whom had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Judah 1958 reported participants had 'schizophrenia in 80% of the treated group and 73% of the control group'. Kramer 1978 included one person with schizoaffective disorder. Somerville 1960 randomised 56 people with schizophrenia or "paraphrenic psychosis" and four with bipolar disorder. These studies were included because the great majority of randomised patients had schizophrenia. Only 16 studies used predefined diagnostic criteria, Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM), International Classification of Diseases (ICD), NIMH criteria, Feighner's criteria, and Chinese Classification of Mental Diseases (CCMD). The remainder appeared to have made a clinical diagnosis. Many studies (n=25) involved people with chronic illnesses; four of these involved people with chronic illness but who were experiencing an acute exacerbation. The rest included acutely ill people and first episode patients; five specified a high level of symptomatology on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS). Ages ranged from seven to above 81 years. Only one study specifically focussed on older patients (Phanjoo 1990).

4.3 Setting Most studies were conducted in hospital settings. Only three trials were undertaken in an outpatient environment (Clark 1975, Nishikawa 1985, Rada 1972). Most trial centres were in North America or Europe, but five were from China (Chen 1995, Gui‐Yun 1988, Ju 1997, Liu 1994, Zhang 1999).

4.4 Study size The number of people in the included studies ranged from 10 to 512. Most studies had 60 or fewer participants.

4.5 Interventions The mean dose of thioridazine, based on 13 studies which reported it, was about 468 mg/day (SD 208 mg/day) and the range, taken from 39 studies, was 25 to 1600 mg/day.

Fourteen studies had a separate placebo arm; two used an 'active placebo' which was phenobarbital with atropine to reproduce the adverse effects of the antipsychotic drugs. Montgomery 1992 involved people allocated to placebo taking thioridazine for one week post‐randomisation. We included this study to increase generalisability of data (including it did not change the overall findings). Twenty‐seven studies compared thioridazine with oral typical neuroleptics such as fluphenazine or chlorpromazine. Three studies (Keks 1994, McCreadie 1988, Phanjoo 1990) compared thioridazine with the atypical remoxipride (which was withdrawn in 1994 following reports of aplastic anaemia), and another three, Carranza 1974, Liu 1994 and Ju 1997, compared thioridazine to the atypicals, sulpiride, and clozapine.

4.6 Outcomes 4.6.1 Missing outcomes No study reported on negative symptoms as an outcome, neither were there usable cognitive outcomes. No included study attempted to quantify levels of satisfaction or quality of life, or any direct economic evaluation of thioridazine.

4.6.2 Scales Most outcomes were reported as dichotomous (yes‐no/binary outcomes), and are presented as such. Scale derived data was obtained from five scales, details of these are given below. We have reported reasons for exclusion of data from other scales in the 'Included studies' table. Scales that provided usable data are reported below.

4.6.2.1 Global State 4.6.2.1.1 Clinical Global Impression ‐ CGI (Guy 1976) The CGI is a three‐item scale commonly used in studies on schizophrenia that enables clinicians to quantify severity of illness and overall clinical improvement. The items are: severity of illness; global improvement and efficacy index. A seven‐point scoring system is usually used with low scores indicating decreased severity and/or greater recovery. Clark 1971, Clark 1975, Liu 1994 reported usable data from this scale.

4.6.2.1.2 Global Assessment Scale ‐ GAS (Endicott 1976) Used to evaluate the overall functioning of a person during a specified time period in terms of psychological well‐being or sickness. The scale ranges from 1 (hypothetically sickest person) to 100 (hypothetically healthiest person) and is divided into 10 equal intervals. High score indicates good outcome. Montgomery 1992 reported usable data from this scale.

4.6.2.2 Mental state 4.6.2.2.1 Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale ‐ BPRS (Overall 1962) The BPRS is an 18‐item scale measuring positive symptoms, general psychopathology and affective symptoms. The original scale has sixteen items, but a revised eighteen‐item scale is commonly used. Scores can range from 0‐126. Each item is rated on a seven‐point scale varying from 'not present' to 'extremely severe', with high scores indicating more severe symptoms. Chen 1995 and Liu 1994 reported usable data from this scale.

4.6.2.3 Behaviour 4.6.2.3.1 Nurses Observational Scale of Inpatients Evaluation ‐ NOSIE (Honingfeld 1965). An 80‐item scale with items rated on a five‐point scale from zero (not present) to four (always present). Ratings are based on behaviour over the previous three days. The seven headings are social competence, social interest, personal neatness, cooperation, irritability, manifest psychosis and psychotic depression. The total score ranges from 0‐320 with high scores indicating a poor outcome. Mena 1966 reported usable data from this scale.

4.6.2.4 Adverse events 4.6.2.4.1 Treatment Emergent Symptoms Scale ‐ TESS (Guy 1976) This checklist assesses a variety of characteristics for each adverse event, including severity, relationship to the drug, temporal characteristics (timing after a dose, duration and pattern during the day), contributing factors, course, and action taken to counteract the effect. Symptoms can be listed a priori or can be recorded as observed by the investigator. The TESS records the presence or absence of a list of side effects. Chen 1995, Gui‐Yun 1988 and Ju 1997 reported usable data from this check list.

Risk of bias in included studies

1. Randomisation Only five studies described the method used to generate random allocation (Bergling 1975, Gardos 1978, Granacher 1982, Gui‐Yun 1988, Ju 1997). They all used tables of random numbers, except one, which used a coin toss. Six studies reported that allocation was undertaken independently (Bergling 1975, Somerville 1960, Stabenau 1964, Wolpert 1968, Herrera 1990, Miyakawa 1973). NIMH 1964 described a form of allocation concealment (sealed envelopes). For other studies readers were given little assurance that bias was minimised during the allocation procedure. Clark 1971 and Keks 1994 used block randomisation. Seventeen studies reported that the numbers allocated to each treatment group were identical, without reporting the use of block randomisation.

2. Blindness Thirty trials were double blind, seven trials did not report whether blinding was attempted, although some report using identical capsules. Three trials were single blind, and one trial was not blinded. Two studies (Mena 1966, Cohler 1966) tested the quality of blinding using a questionnaire.

3. Leaving the study early Thirty eighty of the 42 included studies report data for leaving the study early, and 16 of these described the reasons for this attrition. In the thioridazine versus placebo comparison 24% (n=492) of all participants left the study; in the thioridazine versus typical comparison 16% (n=1587), and; in the thioridazine versus atypical antipsychotics comparison, 26% (n=344).

4. Data reporting Only 12 studies reported that those rating outcome were independent of the treatment (see Included studies table). Largely, a person unlikely to be disinterested in the final result, rated scale outcomes. Most are therefore presented in this review with a warning 'prone to bias'. In any case, continuous scale data were often poorly reported. Frequently they lacked explicit statements regarding the denominator or variance, were only presented as significance tests or within graphs, or simply reported insufficient or no data at all. Liu 1994 reported that all participants in the thioridazine group experienced dry mouth and 60% experienced tachycardia and 45% dizziness, but we were unable to present this data as the frequency of these adverse effects were not reported in the control group. Twelve studies reported scale‐based categorical data that appeared to use the 'last outcome carried forward' (LOCF) approach for those who left the study. Sometimes this was stated in the text, but in other instances it was only apparent from the tables (see Included studies table). We have presented these data in this review. Where they substantially affected the results we reported these instances in the text. Clark 1975 and Nishikawa 1985 reported relapse as a reason for leaving the study early but did not make criteria for this explicit. We could not be sure that these studies reported all relapses in the study population. These sparse outcome data were presented both as 'Relapse, clinically diagnosed' and 'leaving the study'.

Effects of interventions

1. The search The original search (2000) yielded 809 citations, and after removal of duplicate records, 152 were obtained as full publications. A further 15 were acquired after hand searching references of the other papers, but none of the latter could be included. To date, contacting the relevant drug company (Novartis) has not led to further usable data being obtained as limited records of early unpublished research were found (see Acknowledgements). The 2002 update search identified 61 abstracts, 54 were obtained as full publications, and three further studies were included in the review. We found 93 citations during the 2006 update search, and were able to include four additional studies (Carranza 1974, Ju 1997, Schiele 1961, Zhang 1999), and three further reports of studies already included in the review (Gallant 1972, Liu 1994, Rada 1972). This review includes 42 randomised trials with a total of 3498 participants.

2. THIORIDAZINE versus PLACEBO Six hundred and sixty eight participants were randomised within 14 studies.

2.1 Global state 2.1.1 No change or worse Change in global state during short‐term assessment (three months or less) favoured thioridazine compared with placebo (n=100, 3 RCTs, RR 0.66 CI 0.4 to 1.0, NNT 5 CI 3 to 81). At six months, data continued to favour thioridazine (n=105, 3 RCTs, RR 0.32 CI 0.2 to 0.5) with NNT of 2 (CI 2 to 3).

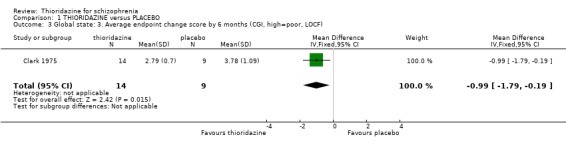

2.1.2 Clinical Global Impression Clinical Global Impression data dichotomised to 'moderately or severely ill' were not significantly different at 28 days or by six months. Clark 1975 used 'last observation carried forward' for about 30% of CGI endpoint data at six months, and we found results favoured thioridazine (n=23, WMD ‐0.99 CI ‐1.8 to ‐0.2) compared with placebo.

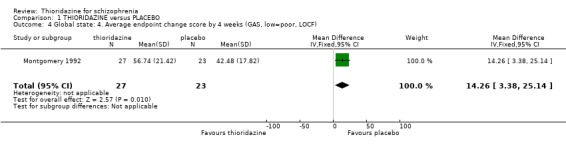

2.1.3 Global Assessment Scale Global Assessment Scale data from one four‐week study (Montgomery 1992) favoured thioridazine (n=50, WMD 14.26 CI 3.4 to 25.1).

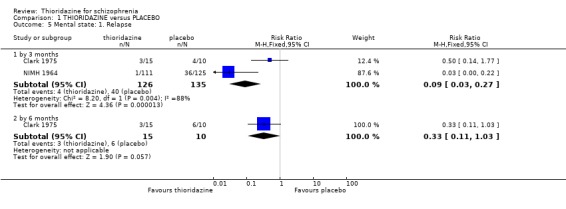

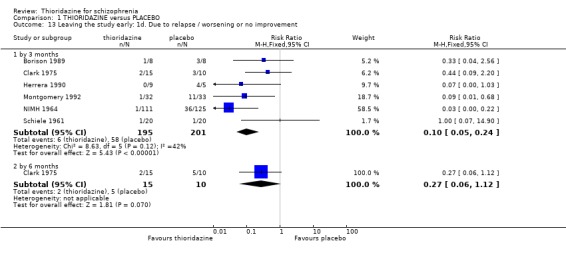

2.2 Mental state 2.2.1 Relapse The number of participants experiencing a (short‐term) relapse were significantly fewer in the thioridazine group compared with placebo (n=261, RR 0.09 CI 0.03 to 0.3) but data are heterogeneous (I2 =88%). Six‐month data found no difference (Clark 1975, n=25, RR 0.33 CI 0.1 to 1.0).

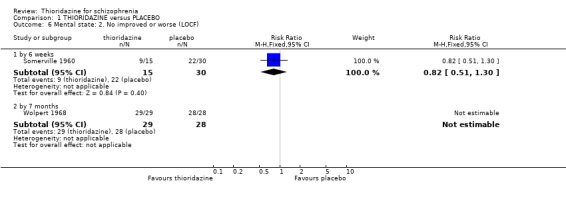

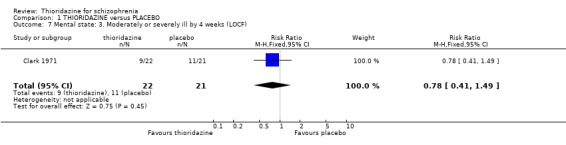

2.2 Not improved or worse For the outcome 'not improved or worse' no differences were found at six weeks (Somerville 1960) or seven months (Wolpert 1968). We found dichotomised data 'moderately or severely ill' (Clark 1971) were equivocal (n=43, RR 0.78 CI 0.4 to 1.5) at four‐week assessment. Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale data (Montgomery 1992) contained wide confidence intervals (skewed data) and are not reported.

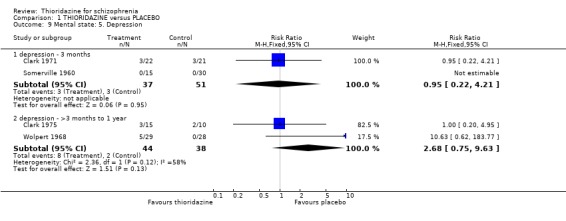

2.2.3 Depression We found no significant differences in rates of depression at short‐term (n=88, 2 RCTs, RR 0.95 CI 0.2 to 4.2) and medium‐term (n=82, 2 RCTs, RR 2.68 CI 0.8 to 9.6) assessment.

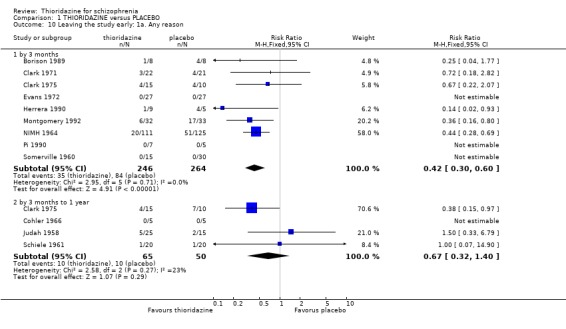

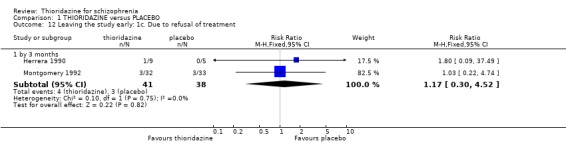

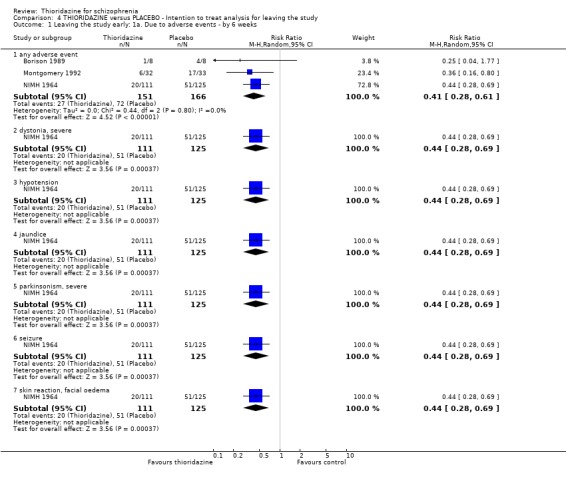

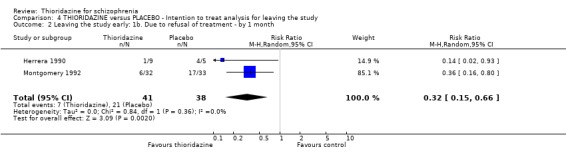

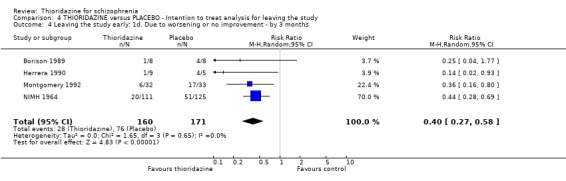

2.3 Leaving the study early We found attrition rates 'any reason' (three months or less) significantly favoured thioridazine (n=510, 9 RCTs, RR 0.42 CI 0.3 to 0.6, NNT 6 CI 5 to 9). Fourteen percent in the thioridazine group left early compared with 32% of people allocated to placebo. The four trials reporting data between three and 12 months (medium‐term) did not clearly favour thioridazine or placebo (n=115, RR 0.67 CI 0.3 to 1.4). Where reasons for leaving the study were reported, more significant differences emerged if negative outcomes were assumed for all those who left the study due to 'relapse or worsening/no improvement' (n=396, 6 RCTs, RR 0.10 CI 0.1 to 0.2, NNT 4 CI 4 to 5). However, where adverse effects were blamed as the reason for leaving, we found no indication that thioridazine promoted this. The same applies to leaving due to refusal of treatment.

2.4 Adverse events 2.4.1 Anticholinergic Very comprehensive lists of adverse effects were reported by several studies. Few differences between thioridazine and placebo were apparent. Limited data from trials suggests that thioridazine is not strongly anticholinergic (blurred vision at six months, n=65, RR 0.76 CI 0.2 to 3.4). The thioridazine group experienced significantly more occurrences of dry mouth in the short‐term (n=324. 3 RCTs, RR 6.75 CI 3.1 to 14.9, NNH 6 CI 3 to 15), but longer‐term data were equivocal (n=82, 2 RCTs, RR 1.62 CI 0.5 to 4.9). We found nasal congestion at short‐term assessment favoured the placebo group (n=279, 2 RCTs, RR 3.42 CI 1.4 to 8.3, NNH 11 CI 4 to 61), but again longer‐term data from one study (Clark 1975) were equivocal (n=30, RR 0.5 CI 0.1 to 4.9).

2.4.2 Arousal Significant data relating to arousal, specifically drowsiness, suggest that thioridazine is sedating both up to three months (n=324, 3 RCTs, RR 5.37 CI 3.2 to 9.1, NNH 4 CI 2 to 7), and from three months to one year (n=162, 4 RCTs RR 2.41 CI 1.3 to 4.5, NNH 6 CI 3 to 27). We found no significant differences for insomnia or excitement from small studies.

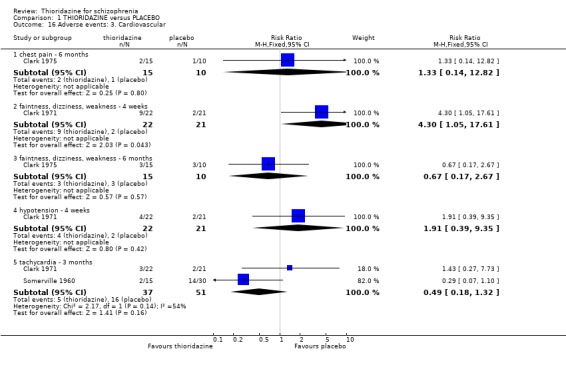

2.4.3 Cardiovascular When cardiovascular adverse effects were recorded we found one outcome (faintness, dizziness and weakness) did favour the placebo group (Clark 1971, n=43, RR 4.30 CI 1.1 to 17.6, NNH 4 CI 2 to 211). However, another small study (n=25) reporting the same outcome did not reveal any significant differences (Clark 1975, RR 0.67, CI 0.2 to 2.7). Other measures, chest pain, hypotension, and tachycardia were not found to be significantly more prevalent in the thioridazine group.

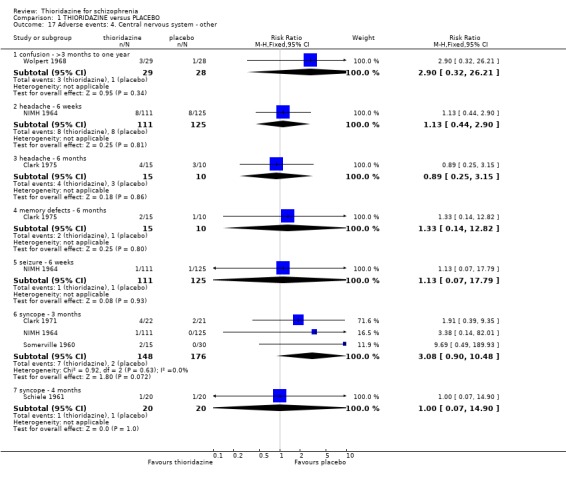

2.4.4 Central nervous system In the earlier version of this review we found data from the NIMH 1964 study were heavily influenced by the assumption of poor outcome for people who had left early, and suggested that placebo promoted headache, fainting and even seizures. We removed this ITT data set from the NIMH 1964 study (adverse events) and analysed without assuming that those lost to follow‐up had had a negative outcome, as those leaving the NIMH 1964 study left due to either treatment failure or administration problems. We found all data for confusion, headache, memory defects, seizures, and syncope were not significantly different between thioridazine and placebo.

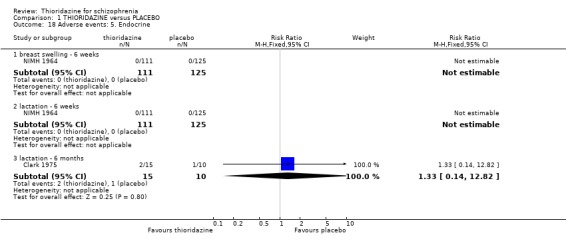

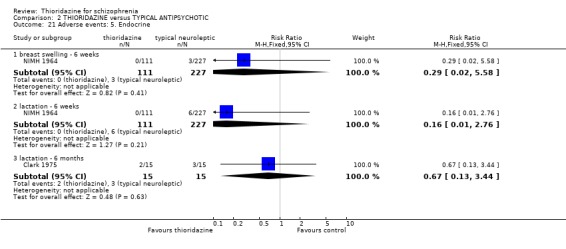

2.4.5 Endocrine Breast swelling and lactation were monitored over six weeks and we found no significant data to suggest that thioridazine promotes this compared with placebo (NIMH 1964). In the Clark 1975 study we again did not find any significant data to suggest that participants given thioridazine for six months had higher occurrences of lactation than the placebo group.

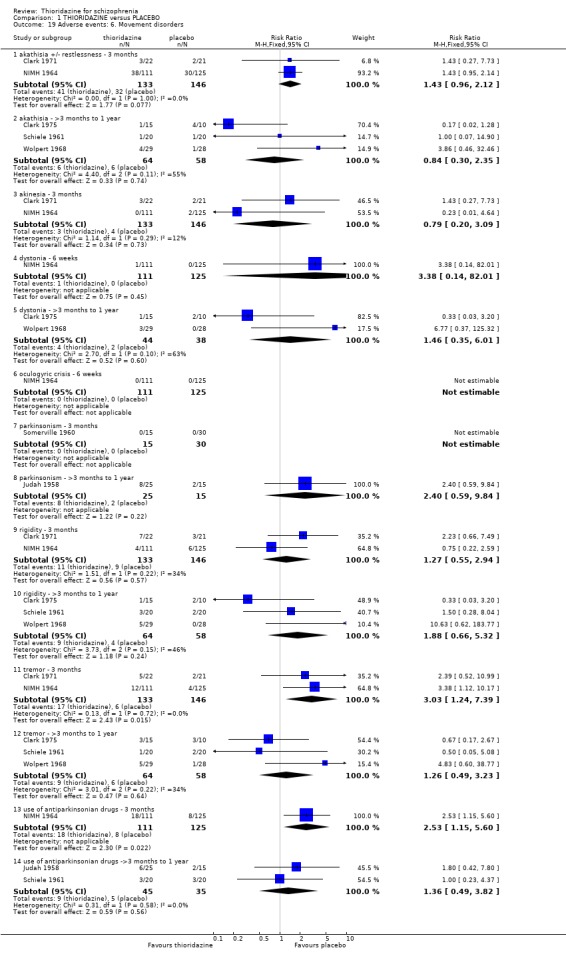

2.4.6 Movement disorders Thioridazine may cause more movement disorders than placebo but most data are equivocal (akathisia, akinesia, dystonia, oculogyric crisis, parkinsonism, rigidity). Only tremor (n=279, 2 RCTs, RR 3.03 CI 1.2 to 7.4, NNH 13 CI 4 to 102), and use of antiparkinsonian drugs (NIMH 1964, n=236, RR 2.53 CI 1.2 to 5.6, NNH 11 CI 4 to 79) were significantly higher in the thioridazine group at short‐term assessment. However, medium‐term follow up (three months to one year) for tremor and use of antiparkinsonian drugs did not reveal any significant difference between thioridazine and placebo.

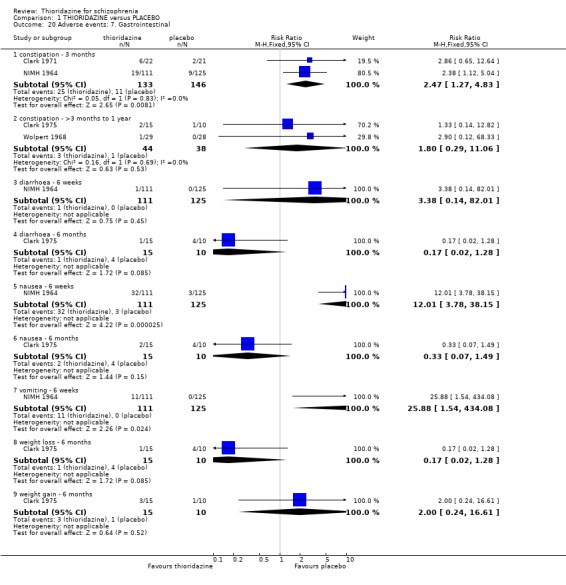

2.4.7 Gastrointestinal We found most outcomes were equivocal. Short‐term data suggests that thioridazine is constipating (n=279, 2 RCTs, RR 2.47 CI 1.3 to 4.8, NNH 10 CI 4 to 45), although medium‐term data (n=82, 2 RCTs, RR 1.80 CI 0.3 to 11.1) did not reveal any significant difference between thioridazine and placebo. Diarrhoea (short and medium‐term) data were equivocal. We found reports of nausea from the NIMH 1964 study to be significantly higher in the thioridazine group (NIMH 1964, n=236, RR 12.01 CI 3.8 to 38.2, NNH 4 CI 2 to 15). However, reports of nausea from (Clark 1975) were not significantly different. Reports of vomiting came from only one study (NIMH 1964) with significantly more participants experiencing vomiting in the thioridazine group (n=236, RR 25.88 CI 1.5 to 434.1, NNH 5 CI 2 to 186) compared with placebo. We found weight loss (n=25, RR 0.17 CI 0.02 to 1.3) and weight gain (n=25, RR 2.00 CI 0.2 to 16.6) were equivocal at six months assessment (Clark 1975).

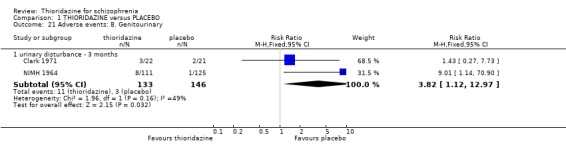

2.4.8 Genitourinary We found non‐specific reports of urinary disturbances, from two studies (Clark 1971, NIMH 1964) were significantly higher in the thioridazine group (n=279, RR 3.82, CI 1.1 to 13.0, NNH 18 CI 5 to 407) compared with placebo at short‐term assessment.

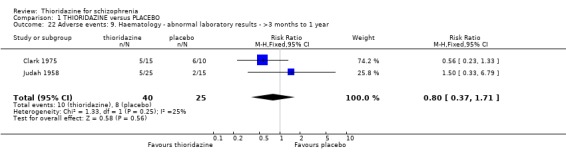

2.4.9 Haematology We found no significant differences (n=65, 2 RCTs, RR 0.80 CI 0.4 to 1.7) between thioridazine and placebo for the outcome of 'abnormal laboratory results' (short‐term assessment).

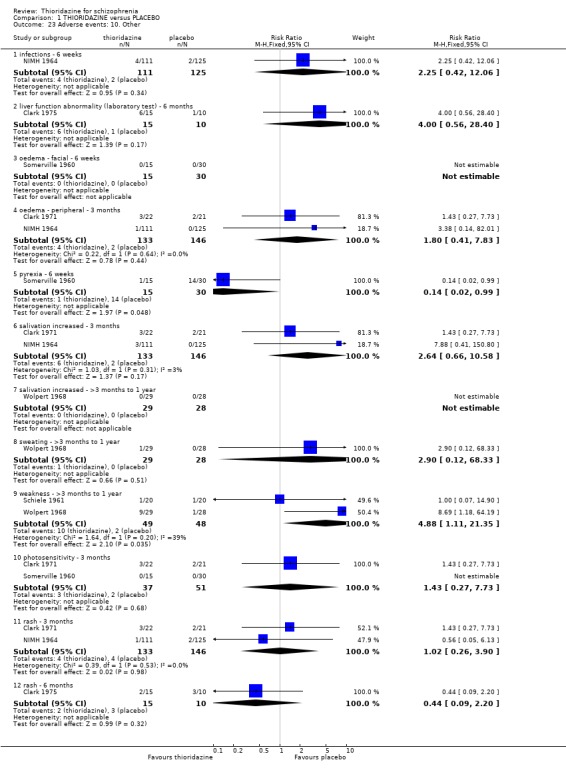

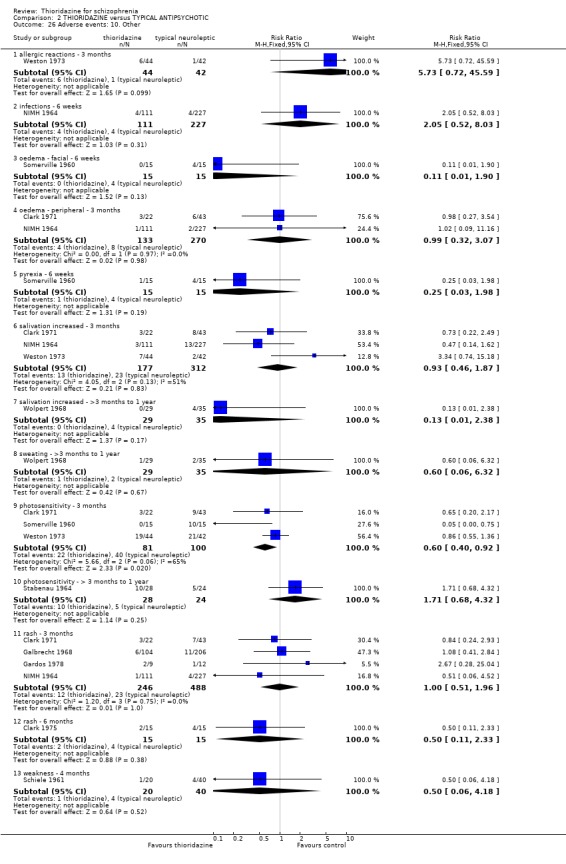

2.4.10 Other adverse effects We found most outcomes were not significantly different (infections, liver abnormalities, oedema, pyrexia, salivation, sweating, photosensitivity, rash) between thioridazine and placebo. Reports of weakness were significantly higher in the thioridazine group (medium‐term assessment) (n=97, 2 RCTs, RR 4.88 CI 1.1 to 21.4, NNH 7 CI 2 to 241).

3. THIORIDAZINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC A total of 2598 participants were randomised within 27 studies.

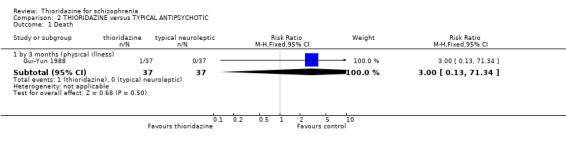

3.1 Death We found no significant differences in death with Gui‐Yun 1988 reporting one death from physical illness in the thioridazine group by three months.

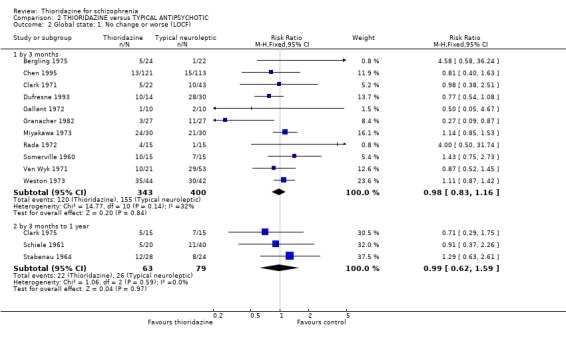

3.2 Global state 3.2.1 No change or worse (LOCF) No significant differences were found (short‐term) in the thioridazine group compared with typical antipsychotics for the number of participants reported as 'not improved or worse' (n=743, 11 RCTs, RR 0.98 CI 0.8 to 1.2). Medium‐term data from three trials (Clark 1975, Schiele 1961, Stabenau 1964) were also equivocal (n=142, RR 0.99, CI 0.6 to 1.6). Excluding studies that used LOCF did not change this.

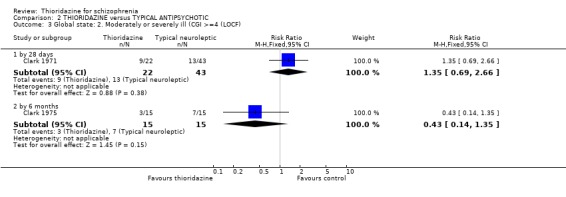

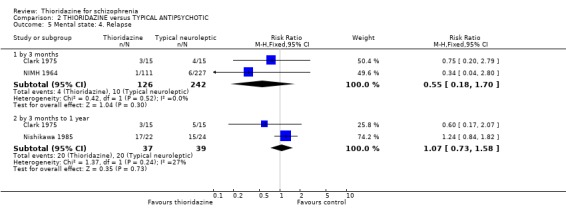

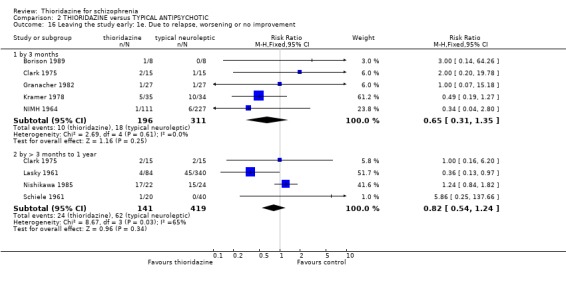

3.2.2 Clinical Global Impression (Moderately or severely ill ‐ LOCF) We found no significant difference during short and medium‐term assessments with CGI scale data dichotomised to 'moderately or severely ill. Clinical Global Impression average endpoint scores by six months (Clark 1975) were also equivocal (n=26, RR ‐0.21 CI ‐0.9 to 0.5). 3.3 Mental state 3.3.1 Relapse We found no significant differences in relapse rates between thioridazine and typical antipsychotics at short (n=368, 2 RCTs, RR 0.55 CI 0.2 to 1.7) and medium‐term (n=76, 2 RCTs RR 1.07 CI 0.7 to 1.6) assessments.

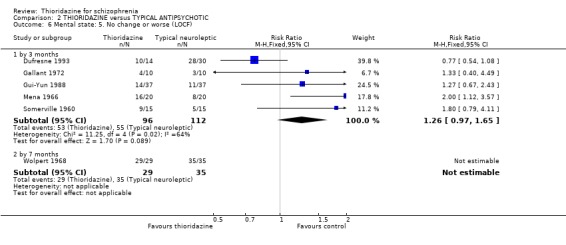

3.3.2 No change or worse (BPRS) Short‐term assessments (by three months) were not significantly different (n=208, 5 RCTs, RR 1.26 CI 1.0 to 1.7) between thioridazine and typical antipsychotic. Wolpert 1968 reported data at seven months and again we found no significant differences when BPRS derived data were dichotomised to 'no change or worse'.

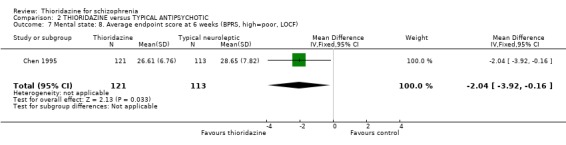

3.3.3 Average endpoint BPRS We found BPRS endpoint scores favoured thioridazine over chlorpromazine at six weeks (n=121, WMD ‐2.04 CI ‐3.9 to ‐0.2) (Chen 1995).

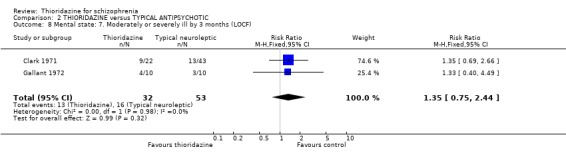

3.3.4 Moderately or severely ill (LOCF) We found no significant difference by three months assessment between thioridazine and typical antipsychotics (n=85, 2 RCTs, RR 1.35 CI 0.8 to 2.4).

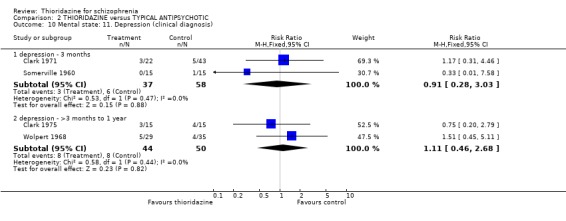

3.3.5 Depressed No significant differences were found in rates of depression between thioridazine and the other typical antipsychotics group at short (n=95, 2 RCTs, RR 0.91 CI 0.3 to 3.0) and medium‐term (n=94 2 RCTs, RR 1.11 CI 0.5 to 2.7) assessment.

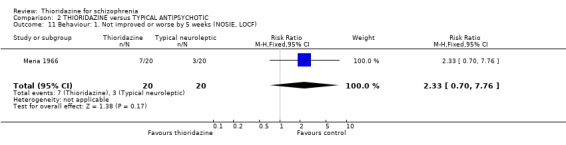

3.4 Behaviour (NOSIE) Just Mena 1966 reported usable data derived from a nurse‐rated scale. We found no significant difference for the outcome 'no better or worse' at five weeks (n=40, RR 2.33 CI 0.7 to 7.8).

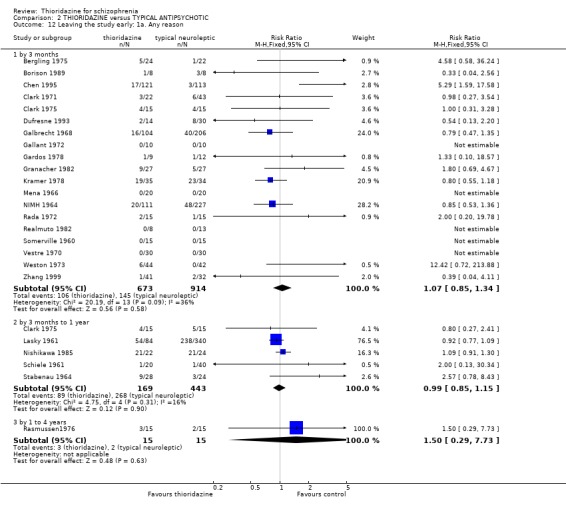

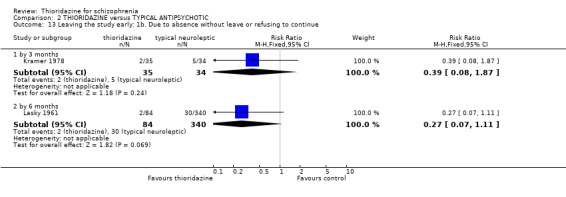

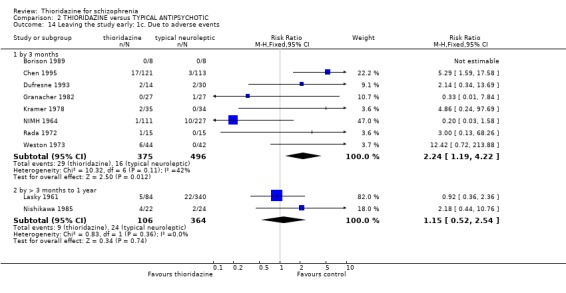

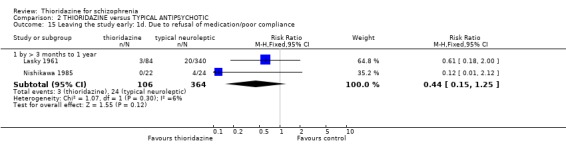

3.5 Leaving the study early The number of people who left the study early during short‐term assessment (up to three months) did not reveal any statistically significant differences between thioridazine and typical antipsychotics (n=1587, 19 RCTs, RR 1.07 CI 0.9 to 1.3). Sixteen percent of participants from each group left the study early. Five medium‐term studies (n=612) also suggested no significant difference. Attrition rates from Rasmussen 1976 (n=30) were also equivocal at three and a half years (RR 1.50 CI 0.3 to 7.7). Where reasons were cited for study attrition, due to absence or refusal to continue, no significant differences were found. The strongest data relate to attrition due to adverse effects. These favoured typical antipsychotic drugs over thioridazine (n=871, RR 2.24 CI 1.2 to 4.2, NNT 26 CI 10 to 164). Medium‐term data from two studies were equivocal. Leaving due to refusal of medication/poor compliance, or relapse/no change or worsening of heath did not reveal any significant difference.

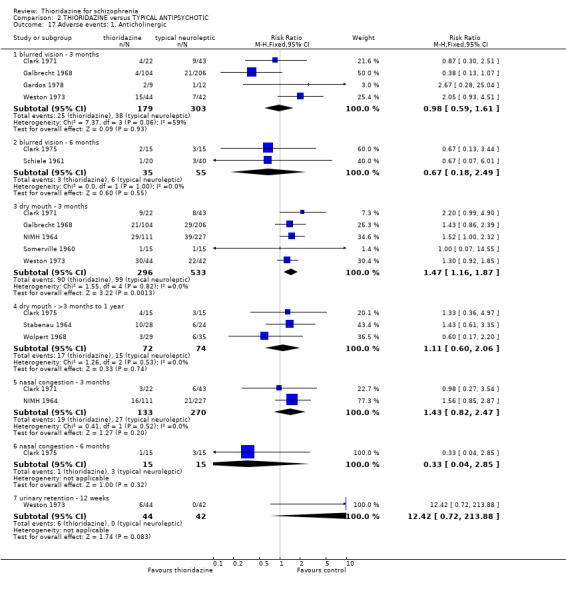

3.6 Adverse events 3.6.1 Anticholinergic There were no clear differences between thioridazine and other typical antipsychotics for the majority of anticholinergic adverse effects. Incidences of dry mouth were significantly higher in the thioridazine group (n=829, 5 RCTs, RR 1.47 CI 1.2 to 1.9, NNH 12 CI 7 to 34). However, medium‐term data (three months to one year) were equivocal (n=146, 3 RCTs RR 1.11 CI 0.6 to 2.1). Blurred vision, nasal congestion, and urinary retention were not significantly different between groups.

3.6.2 Arousal About half of those allocated thioridazine felt drowsy or sedated but these data are no different from typical antipsychotics (n=891, 8 RCTs, RR 1.10 CI 0.9 to 1.3). All other measures of arousal, excitement, and insomnia were not significantly different.

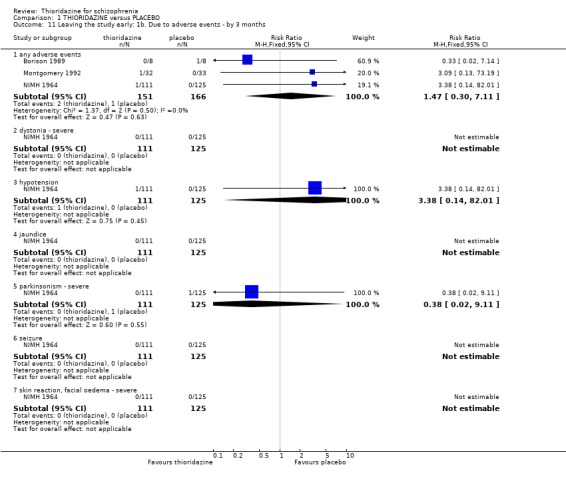

3.6.3 Cardiovascular We found data from Gui‐Yun 1988 favoured chlorpromazine for the outcome 'any cardiovascular adverse event' (n=74, RR 3.17 CI 1.4 to 7.0, NNH 3 CI 2 to 5) by three months. Results from two studies (Chen 1995, Gallant 1972) measuring changes in electrocardiogram (ECG) were significantly higher in the thioridazine group (n=254, RR 2.38, CI 1.6 to 3.6, NNH 4 CI 3 to 10). All other cardiovascular outcomes (chest pain, faintness/dizziness/weakness, hypotension, and tachycardia) did not reveal any significant differences.

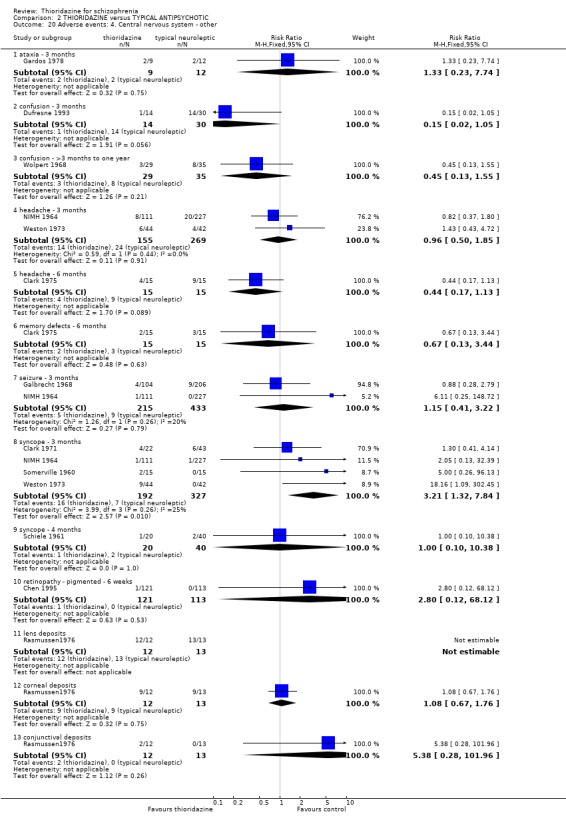

3.6.4 Central nervous system We found data from four studies favoured other typical antipsychotics for the outcome 'syncope' (n=519, 4 RCTs, RR 3.21 CI 1.3 to 7.8, NNH 22 CI 7 to 156). However, we found data reported at four months (Schiele 1961) were not significantly different (syncope, n=60, RR 1.00 CI 0.1 to 10.4). One participant in the thioridazine group developed pigmented retinopathy (Chen 1995, n=234, RR 2.80 CI 0.1 to 68.1). We found no difference in ocular deposits between chlorpromazine and thioridazine (Rasmussen 1976, n=30). All other outcomes, ataxia, confusion, concentration difficulties concentration difficulties, headache, memory defects, and seizure did not reveal any significant differences.

3.6.5 Endocrine We found no significant differences between thioridazine and other typical antipsychotics for the adverse effects of breast swelling, and lactation.

3.6.6 Movement disorders Extrapyramidal adverse events that required use of antiparkinsonian drugs were significantly lower in the thioridazine group (n=1082, 7 RCTs, RR 0.45 CI 0.4 to 0.6), but data are heterogeneous (I2 statistic 82%). Medium‐term data by Schiele 1961 and Stabenau 1964 did not reveal any significant difference for the same outcome. We found reports of parkinsonism were significantly higher in the other typical antipsychotic group (n=340, RR 0.29 CI 0.1 to 0.7, NNH 9 CI 8 to 22) during three months of assessment. Short‐term reports of rigidity were equivocal (n=509, 4 RCTs, RR 0.60 CI 0.4 to 1.0), but medium‐term data suggests rigidity occurs more frequently in the other typical antipsychotics (n=154, 3 RCTs, RR 0.44, C 0.2 to 0.9, NNH 6 CI 4 to 23). Akathisia data (short and medium‐term) were not significantly different. All other assessments (akinesia, dyskinesia, dystonia, oculogyric crisis, and tremor) did not reveal any significant differences.

3.6.7 Gastrointestinal We found data from NIMH 1964 favoured the typical antipsychotics for the outcome 'nausea' (n=338, RR 2.35 CI 1.5 to 3.7, NNH 7 CI 4 to 18) by six weeks. However, another study (Clark 1975) revealed no significant differences in rates of nausea by 6 months (n=30, RR 0.50 CI 0.1 to 2.3). Reports of vomiting from three studies (Galbrecht 1968, NIMH 1964, Weston 1973) favoured the typical antipsychotic group (short‐term) with significantly more participants in the thioridazine experiencing vomiting (n=734, RR 1.82 CI 1.1 to 3.0, NNH 20 CI 9 to 150). Only two studies reported on weight gain (Rada 1972, n=30, RR 1.00 CI 0.6 to 1.7 by 3 months, and Clark 1975, n=30, RR 0.6 CI 0.2 to 2.1 by 6 months) but no significant differences were apparent. All other outcomes constipation, diarrhoea and weight loss were not significantly different between thioridazine and typical antipsychotics. 3.6.8 Genitourinary Difficulty with urination did not reveal any significant difference between thioridazine and typical antipsychotics (n=799, 4 RCTs, RR 1.62 CI 0.9 to 2.8) by three months assessment.

3.6.9 Laboratory tests We found no significant differences in abnormal laboratory results between treatment groups for blood cell tests or liver and renal functioning.

3.6.10 Other adverse events Reports of photosensitivity were significantly higher in the typical antipsychotics (n=181, 3 RCTs, RR 0.60 CI 0.4 to 0.9, NNH 7 CI 5 to 32) during short‐term assessment, but data from Stabenau 1964 at ten months were not significantly different (n=52, RR 1.71 CI 0.7 to 4.3). We found reports of allergic reactions, infections, odema, pyrexia, salivation, sweating, rash, and weakness did not reveal any significant differences between thioridazine and other typical antipsychotics.

4. THIORIDAZINE versus ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTIC A total of 344 participants were randomised within six studies.

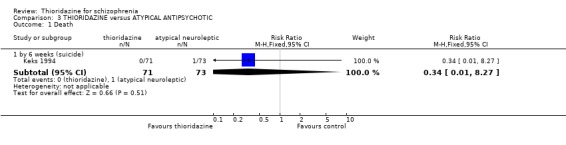

4.1 Death Keks 1994 reported one death (by suicide) in the remoxipride group by six weeks.

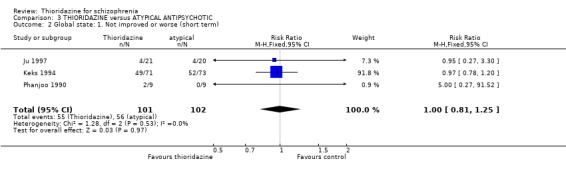

4.2 Global state 4.2.1 Not improved or worse We found three studies (Ju 1997, Keks 1994, Phanjoo 1990) reporting global state 'not improved or worse', and found no significant differences between thioridazine and the atypical antipsychotics, remoxipride and sulpiride (n=203, RR 1.00 CI 0.8 to 1.3) during short‐term assessment.

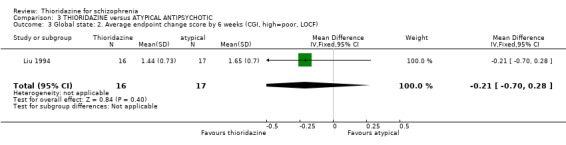

4.2.2 Clinical Global Impression We found CGI endpoint data at 6 weeks were not significantly different between thioridazine and clozapine (Liu 1994, n=33 RR ‐0.21 CI ‐0.7 to 0.3).

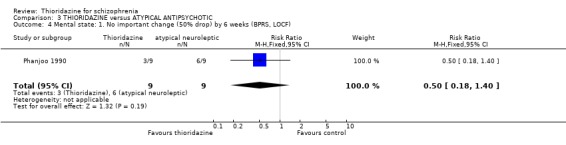

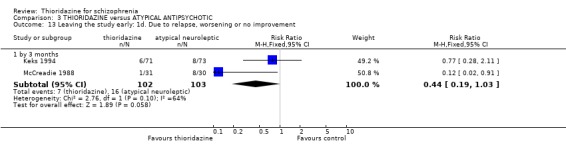

4.3 Mental state 4.3.1 No significant change (BPRS) Phanjoo 1990 reported on 'no important change' on the BPRS scale by six weeks, with 50% of participants dropping out of the study. We found no significant differences between groups (n=18, RR 0.50 CI 0.2 to 1.4).

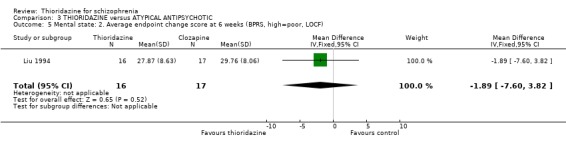

4.3.2 Average endpoint change scores We found no significant difference in BPRS endpoint scores (Liu 1994, n=33, WMD ‐1.89 CI ‐7.6 to 3.8) at 6‐week assessment between thioridazine and clozapine. Liu 1994 assessed participants using the SAPS and SANS scale but data were found to contain wide confidence intervals (skewed data) and are not reported here. Keks 1994, McCreadie 1988 both reported BPRS data but again these contained wide confidence intervals and are not reported.

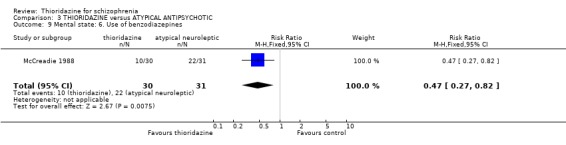

4.3.3 Use on benzodiazepines Only McCreadie 1988 reported on this outcome and we found the thioridazine group needed significantly fewer benzodiazepines compared with the remoxipride group (n=61, RR 0.47 CI 0.3 to 0.8, NNT 3 CI 2 to 8).

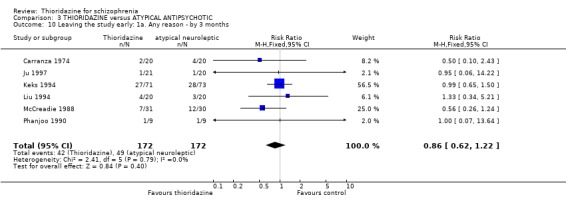

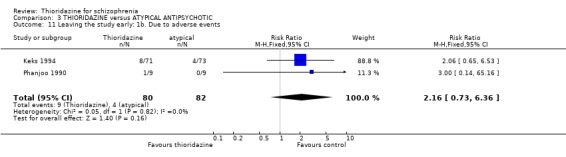

4.4 Leaving the study early We found the number of participants leaving the studies early were not significantly different between thioridazine and atypical antipsychotics (n=344, 6 RCTs, RR 0.86 CI 0.6 to 1.2) during short‐term assessment. We also found no significant differences for leaving the studies due to adverse events, refusal of medication/poor compliance, or relapse/worsening between groups.

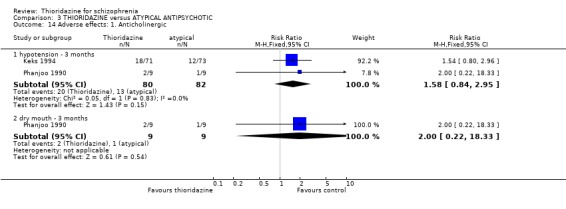

4.5 Adverse effects 4.5.1 Anticholinergic We found no significant differences between thioridazine and atypicals for the outcomes of hypotension (n=162, 2 RCTs RR 1.58 CI 0.8 to 3.0) and dry mouth (Phanjoo 1990, n=18, RR 2.0 CI 0.2 to 18.3) at short‐term assessment.

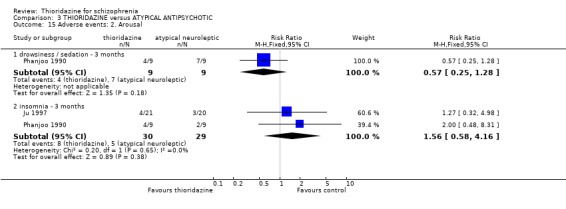

4.5.2 Arousal We found data reported by Phanjoo 1990 for the outcomes 'drowsiness/sedation' were equivocal and data by (Ju 1997, Phanjoo 1990) for 'insomnia' revealed no significant differences between thioridazine and atypical antipsychotics.

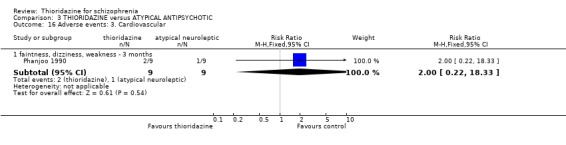

4.5.3 Cardiovascular For the outcome 'faintness, dizziness, weakness' no significant differences were apparent (Phanjoo 1990, n=18, RR 2.00, CI 0.2 to 18.3).

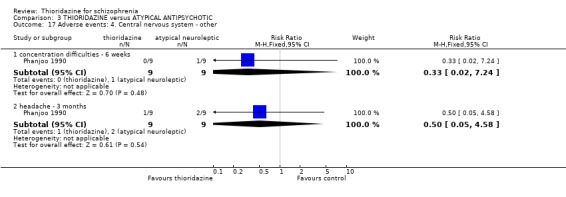

4.5.4 Central nervous system We found data reported by Phanjoo 1990 for the outcomes 'concentration difficulties' and 'headache' were not significantly different between thioridazine and remoxipride.

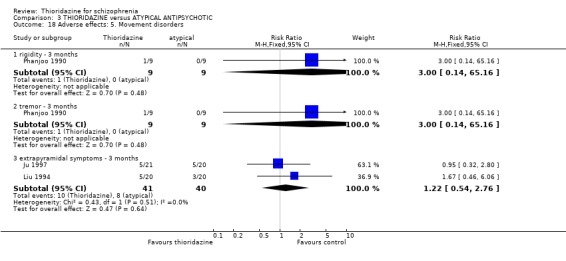

4.5.5 Movement disorders All data by Phanjoo 1990 (n=18) were equivocal for the outcomes 'rigidity' and 'tremor'. Extrapyramidal symptoms reported in two studies (Liu 1994, Ju 1997) were not significantly different between thioridazine and atypicals (n=81, RR 1.22 CI 0.5 to 2.8).

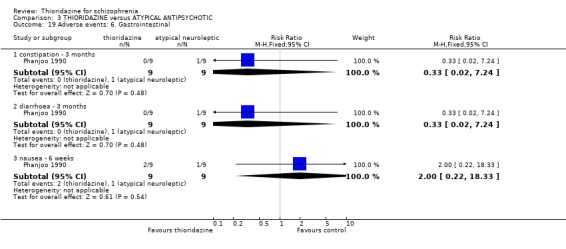

4.5.6 Gastrointestinal We found no significant differences for the adverse events, constipation, diarrhoea or nausea from the small study (n=18) by Phanjoo 1990.

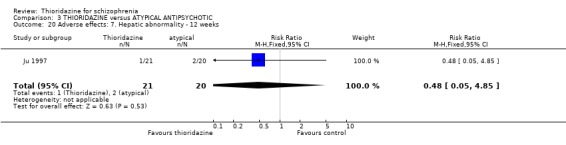

4.5.7 Hepatic abnormalities Ju 1997 reported the only data for this outcome and we found no significant difference between thioridazine and sulpiride (n=41, RR 0.48, CI 0.1 to 4.9).

5. Publication bias Funnel plots were planned to investigate the possibility of publication bias (see Methods). No overt asymmetry was detected but many of the outcomes had a small number of trials which limits the value of the plot. Such plots are not powerful investigative tools and are further weakened when there is little variation in study size (Egger 1997).

6. Sensitivity analysis 6.1 Intention to treat Sensitivity analysis in which those who left the study were not assumed to have a bad outcome did not substantially change most of the main outcomes. An exception was placebo‐controlled data on the breakdown of reasons for leaving the study. The a priori protocol for this review stated that if there was a difference in the results between completer analysis and 'intention to treat' analysis, then the latter would be preferred. The other exception was placebo‐controlled adverse event data for extrapyramidal, gastrointestinal, endocrine and miscellaneous other adverse events which favoured thioridazine over placebo. This was due to the differential drop‐out rate in the NIMH 1964 study. None of the NIMH 1964 placebo group were removed from the study due to complications of treatment (i.e. adverse events), but participants were removed mainly due to treatment failure (relapse), or administrative reasons. Therefore, outcome data from the NIMH 1964 study were presented in the results section using ITT only for relapse. Adverse events data were reported without using ITT assumptions. We feel this provides a more accurate appraisal of the data.

6.2 The elderly No sensitivity analyses were possible for the elderly, as had been planned, as only one small study (Phanjoo 1990) focused on an older age group.

6.3 Last observation carried forward A planned sensitivity analysis where data using 'last outcome carried forward' (LOCF) was removed (see Methodological quality of included studies) gave essentially the same outcomes as the main analyses with a few exceptions. These have already been noted and did not appear clinically or statistically significant. The LOCF data were therefore included in the main analysis and the overall stability of the findings on sensitivity testing appears high.

Discussion

1. Generalisability of findings Overall, we felt generalisability to be good as the 42 included studies involved people with schizophrenia who would be recognisable in everyday practice. In most of the studies the diagnosis was clinical and only a few used operational criteria. Both those with acute and chronic illness participated. Studies were, however, undertaken mostly in hospital settings. The daily doses of thioridazine largely reflected present practice, although seven studies did employ higher levels. Non‐Western cultures were represented by only five studies and therefore applicability to those in the developing world may be limited. People with both schizophrenia and substance misuse were frequently excluded which may reduce applicability of findings, as co‐existence of the two problems is common (Turner 1990).

Only one small study (Phanjoo 1990) included people in the older age group. For 18 people aged 67‐70 years, it compared thioridazine with remoxipride; the latter was withdrawn in 1994 following reports of aplastic anaemia. In addition, Judah 1958 reported a median age of 63 years for trial participants but did not give a range. Other trials did include older patients but did not present their data separately and, although attempts were made to contact authors, it was not possible to obtain individual patient data. Many studies excluded elderly people. Thioridazine has been considered a drug of choice in the elderly (see Background) and is thought to have been widely used in this group (King 1995); however, this clinical preference does not appear to be based on good quality, trial‐based evidence for elderly patients with schizophrenia.

2. THIORIDAZINE versus PLACEBO

2.1 Global state People given placebo were significantly more likely to have the negative outcome 'no change or worse' than the thioridazine group, with short‐term NNT of about five. This treatment effect became more apparent during medium‐term assessment with NNT lessening to about two. Clinical Global Impression scores 'moderate or severely ill' from two small studies did not reveal any significant differences; larger sample sizes are needed before we can have confidence in this result. Medium‐term (six months) endpoint CGI data significantly favoured thioridazine using the last observation carried forward method, but with assumptions being made for many of the (n=23) participants more robust data is needed to inform clinicians of its true efficacy. Global Assessment Scale data (Montgomery 1992) also significantly favoured thioridazine, again from limited numbers. Nevertheless, thioridazine does appear to confer an advantage over placebo when rated as 'no change or worse'.

2.2 Mental state For the comparison of thioridazine versus placebo, few data exist to support its effect on mental state. It is a sign of changing times that this drug could, for so long, be a widely used antipsychotic and favoured for elderly people, on the back of such limited trial data. The only statistically significant outcome was relapse. To prevent one person relapsing about four people need treating.

2.2 Leaving the study early Indirect data on global effect, or acceptability of the treatments may be seen in the attrition data. Significantly fewer people allocated to thioridazine left studies early (NNT 6). The reasons for this, hopefully but not necessarily, were that they were better, or at least encouraged by improvement. When specific reasons are cited for leaving early the data are not very helpful, although fewer people given thioridazine leave due to relapse. All studies suffered considerably fewer losses than more 'sophisticated' studies currently prevalent (Thornley 1998). This could be for a variety of reasons including selection of participants, drug regimens used, outcomes measured and general conduct of the studies. Whatever the reason, it would seem prudent for trialists to investigate these old studies in order to improve the wasteful loss of data in current randomised trials.

2.3 Adverse events Despite comprehensive lists of adverse effects, few differences between thioridazine and placebo were apparent. Trial data support the clinical impression that thioridazine is not strongly anticholinergic. Thioridazine appears to be sedating during short‐term (NNH 4) and medium‐term (NNH 6) assessment. No clear differences emerged for cardiovascular adverse effects with all but one outcome being non‐significant; the four‐week assessed outcome of significance, 'faintness, dizziness, weakness' became equivocal at the longer six months evaluation. All outcomes categorised as central nervous system adverse events were equivocal. We found no significant data to suggest that thioridazine causes breast swelling or lactation. Data relating to movement disorders do not fall into a clear pattern. Only tremor (NNH 13) and use of antiparkinsonian drugs (NNH 11) were higher in the thioridazine group, but the same outcomes were equivocal when assessed over a longer period of time. Similarly, data for gastrointestinal adverse effects did not reveal a clear pattern to indicate that thioridazine causes such problems, although constipation (NNH 10), and vomiting (NNH 5) may be increased by thioridazine, but without more robust data uncertainties remain. Genitourinary disturbances may also be an adverse effect of thioridazine (NNH 18), but we are unable to specify the type of disturbance, so such data are of limited use. We found no significant data on haematological abnormalities from two small studies. Other adverse events data were inconclusive. We found no data reporting on retinal changes. This is not entirely surprising, as trials, especially small, short‐term trials, are poor at detecting rare, important adverse effects. Also, most trials were not using the high doses associated with retinopathy (Rennie 1993).

3. THIORIDAZINE versus TYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS

3.1 Death There was just one death for a total of about 800 person‐years (crude mortality rate: one death per 423 person‐years). Gui‐Yun 1988 reported one death in the thioridazine group from an unspecified physical illness. The lifetime incidence of suicide for people suffering from schizophrenia is 10‐13% (Caldwell 1992). The use of high doses of antipsychotic drugs has been associated with sudden death (Jusic 1994). Seven studies did employ higher doses than in modern practice but no sudden or cardiac deaths were reported in the included studies. This was with about 566 person/years exposure to thioridazine. This might have been because of careful screening for physical illness, because the level of monitoring is high in clinical trials and because polypharmacy is prevented by the study protocol. Alternatively, this meta‐analysis may not have had sufficient power to detect what might be a rare event. Thioridazine has also been reported to be associated with sudden death at normal doses (Mehtonen 1991).

3.2 Global state Analyses of various measures of global state consistently failed to find clear differences between thioridazine and other typical antipsychotics such as the 'benchmark' drug chlorpromazine (Thornley 2003). This was also the case when studies using LOCF were excluded.

3.3 Mental state Generally thioridazine had a similar efficacy to other typical antipsychotic drugs for various measures of mental state, 'relapse', 'no change or worse', 'moderately or severely ill', 'depression'. Only BPRS endpoint scores measured at 6 weeks were significant in favour of thioridazine when compared with chlorpromazine, but with all other outcomes being equivocal, more data are needed to have confidence in this single finding.

3.4 Behaviour Only one study (Mena 1966) measures changes in behaviour using the NOSIE scale, but data were equivocal between thioridazine and mesoridazine.

3.5 Leaving the study early Sixteen percent left the thioridazine groups, and also 16% in the control group by three months, which is low for clinical trials of people with schizophrenia, but thioridazine did not confer any advantage over other typical antipsychotics. Medium and longer‐term evaluation also revealed no significant differences. Specific reasons for leaving the study early did not reveal any significant differences, except for 'due to adverse events' which favoured typical antipsychotics (NNT 26), however, two studies providing data up to one year indicated no significant differences.

3.6 Adverse events We found no difference, on intention to treat analysis, between the overall tolerability of thioridazine and other drugs as measured indirectly by leaving the study due to adverse events.

A great number of adverse effects were listed in the included studies but few showed clear differences between thioridazine and other typical antipsychotics. Thioridazine caused dry mouth (NNH 12) by three months assessment (n=829), but this outcome did not remain statistically significant in the three trials (n=148) collecting data for one year. We found no convincing data to suggest that thioridazine is any more or less anticholinergic that other typical antipsychotics. Although about half of all participants given thioridazine felt either drowsy or sedated, the control group also experienced similar levels of this adverse event. Cardiovascular adverse events were mostly non‐significant, but the outcome 'any cardiovascular adverse event' was higher in the thioridazine group (NNH 3), but this non‐descriptive event is not informative to clinicians. Electrocardiogram changes were more frequent in the thioridazine (NNH 4) group, confirming its recognised potential to affect heart rhythm (Psychotropics 2006), although we do not know whether these changes were torsades de pointe or other changes. Hypotension affected about 40% of those given thioridazine compared with about 30% of the other typical antipsychotics, and was not significantly different (n=106). Larger scale studies are required to determine if thioridazine causes hypotension more frequently and severely than other typical antipsychotics. Fainting occurred more often in the thioridazine group (NNH 22, n=519) during short‐term assessment, whereas data from Schiele 1961 were equivocal at four months, but is based on a sample of just 60 participants.

One case of pigmented retinopathy on thioridazine was reported (Chen 1995). This was with about 566 person/years exposure to thioridazine. This implies that it is a rare adverse event or that it may have been underreported. Pigmented retinopathy is associated with doses above 800 mg which were only permitted in seven of the reviewed studies. Also, many studies were short‐term and pigmented retinopathy is associated with prolonged use (see Background). Endocrine adverse effects were infrequent and non‐significant between thioridazine and other typical antipsychotics. Thioridazine is less likely to cause extrapyramidal adverse effects, but data are heterogeneous. This is largely a function of McCreadie 1988, but the reasons why this study introduces heterogeneity are unclear. If data from this study are excluded the effect is even more in favour of thioridazine. However, medium‐term extrapyramidal adverse events (up to one year) (Schiele 1961, Stabenau 1964) were not significantly different. Parkinsonism (NNH 9) and rigidity (NNH 6) affected the control group more than the thioridazine group, but larger trials are needed to add weight to limited data. Other measures (akinesia, dyskinesia, dystonia, oculogyric crisis, and tremor) did not reveal any great differences. Gastrointestinal adverse events were mostly equivocal. Nausea did occur more in the thioridazine group (NNH 7) at short‐term, but one small six month study did not substantiate this initial finding. Vomiting was also higher in the thioridazine group but more trial data are needed to have confidence that a real difference exists between thioridazine and other typicals. Reports of weight loss and gain were equivocal, but detecting differences from such small studies (n=30) was unlikely. Genitourinary and laboratory tests did not reveal any significant differences. Most other adverse events were equivocal, except for photosensitivity which affected the other typical group more (NNH 7), but this finding was not sustained during one year follow up (Stabenau 1964, n=52).

4. THIORIDAZINE versus ATYPICAL ANTIPSYCHOTICS

4.1 Death One control group death was due to suicide (Keks 1994) giving a lifetime rate of about 14% as would be expected for this group.

4.2 Global state Both global state assessment 'not improved or worse' and continuous CGI scale data did not reveal any significant differences between thioridazine and atypical antipsychotics at short‐terms assessments. Larger studies of longer duration are needed to determine if the atypical antipsychotics are more beneficial than thioridazine.

4.3 Mental state Data were limited and mostly equivocal for the assessment of mental state. Only 'use of benzodiazepines' resulted in a significant difference favouring thioridazine (NNT 3) in comparison with the withdrawn drug remoxipride.

4.4 Leaving the study early Study attrition for any reason and specific reasons were all non‐significant, and as a proxy measure for treatment acceptability thioridazine was no more or less acceptable than atypical antipsychotics.

4.5 Adverse events Adverse events data all came from small scale studies and most came from (Phanjoo 1990) (n=18). All adverse event categories, anticholinergic, arousal, cardiovascular, central nervous system, movement disorders, gastrointestinal adverse events, and hepatic abnormalities were equivocal. We were unlikely to find statistically significant data from such small data sets. Without adequate sample sizes detecting differences between thioridazine and typical antipsychotics is unlikely unless large treatment effects are present.

Authors' conclusions

1. For clinicians Although there are shortcomings and gaps in the data, there appears to be enough overall consistency over different outcomes and time scales to confirm that thioridazine is an antipsychotic of similar efficacy to other commonly used neuroleptics, such as chlorpromazine, for people with schizophrenia. The adverse event profile of thioridazine seemed similar to that of typical drugs overall, but it may have a lower overall level of extrapyramidal adverse events. Considering that this adverse effect is the only clinical feature that makes the atypicals (except clozapine) really different from the typicals, it is not surprising that thioridazine has been suggested as having an 'atypical' profile. Electrocardiogram changes were significantly higher in the thioridazine group, which fits with the guidelines of monitoring patients for cardiovascular abnormalities. Thioridazine has been widely used in the elderly (King 1995), but this clinical preference does not appear to be based on good quality, trial based evidence for elderly people with schizophrenia. This is of concern to clinicians as there are many reasons why the elderly might be vulnerable to thioridazine's adverse events. In view of the lack of evidence, possible benefits versus harm of prescribing thioridazine must be carefully looked at for these patients, and alternative treatments considered. Clinicians in the UK will not be faced with these clinical decisions after the voluntary withdrawal of thioridazine from the market by Novartis, and the MHRA decision to stop licensing the drug in the UK. Thioridazine may still be obtained under generic label, and clinicians in some countries, where these restrictions do not apply will need to consider the advantages and disadvantages of prescribing thioridazine carefully.

2. For people with schizophrenia Thioridazine is probably as effective as other commonly used antipsychotic treatments for schizophrenia and it may have a lower level of extrapyramidal adverse events. It may therefore be a matter of personal preference as to which treatment is best, although since the recent withdrawal of thioridazine in the UK, this consideration is unlikely to apply to most people with schizophrenia, especially those in Europe and North America. In the elderly, there is no strong evidence that it is an effective treatment or that it is preferable to other antipsychotics, and may present an unacceptable risk considering the concerns of cardiotoxicity. However, with the withdrawal of thioridazine people in the older age groups may wish to ask what other treatments are available, which are better supported by evidence.

3. For managers, funders, decision makers Following the recent withdrawal of thioridazine in 2005, managers may consider whether other antipsychotics are able to provide a low risk of extrapyramidal adverse events for elderly patients.

1. General The trials reviewed predated the CONSORT statement (Begg 1996). Had this been anticipated much more data would have been available to inform practice. Allocation concealment gives the assurance that selection bias is kept to the minimum and should be properly described. Only seven studies in this review reported independent allocation or allocation concealment. For the other studies readers were given little assurance that bias was minimised during the allocation procedure. Well reported and tested blinding could have encouraged confidence in the control of performance and detection bias. Twenty of the reviewed trials described precautions to make the investigation blind but only two studies (Mena 1966, Cohler 1966) tested the quality of blinding using a questionnaire. It is also important to know how many, and from which groups, people were withdrawn in order to evaluate exclusion bias. Raters should be independent of treatment. This was the case in only ten of the reviewed studies (see Included studies table). Continuous data were poorly reported in the reviewed studies. It would have been helpful if authors had presented data in a way which reflects associations between intervention and outcome, for example, relative risk, odds‐ratio, risk or mean differences, as well as raw numbers. Binary outcomes should be calculated in preference to continuous results, as they are easier to interpret. Trials should report service utilisation data as well as satisfaction with care and economic outcomes.