Abstract

Background

Evidence supports a role for NMDA receptors in learning and memory. These can be modulated by the antibiotic D‐cycloserine in such a way that the effect of the excitatory transmitter substance glutamate is enhanced. A study on healthy subjects pretreated with scopolamine to mimic Alzheimer's disease showed a positive effect of D‐cycloserine at low doses.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of D‐cycloserine in patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Search methods

The trials were identified from a search of the Specialized Register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group on 2 January 2004 using the terms: cycloserine, D‐cycloserine. The Register contains records from all major health care databases and is updated regularly.

Selection criteria

Randomized, double‐blinded and unconfounded trials comparing D‐cycloserine with a control treatment.

Data collection and analysis

Two larger and two smaller randomized controlled trials were identified. The Clinical Global Impression scale was used in all studies and was a primary outcome measure.

Main results

It was not possible to extract the results from the first phases of the two crossover studies and therefore the meta‐analyses are based on the two parallel group 6‐month studies. There was no indication of a positive effect favouring D‐cycloserine for the numbers showing improvement at 6 months as assessed by the Clinical Global Impression for any dose. The number of withdrawals for any reason before end of treatment at 6 months was significantly in favour of placebo (fewer withdrawals) compared with D‐cycloserine for dose levels of 30 mg/day (OR 2.94, 95% CI 1.52, 5.70) and 100 mg/day (OR 3.23, 95% CI 1.67, 6.25). There was no significant difference between treatment, (2, 10, 30, 100, or 200 mg/day) and placebo for the number of withdrawals due to adverse events by six months.

Authors' conclusions

The lack of a positive effect of D‐cycloserine on cognitive outcomes in controlled clinical trials with statistical power high enough to detect a clinically meaningful effect means that D‐cycloserine has no place in the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Keywords: Humans; Alzheimer Disease; Alzheimer Disease/drug therapy; Anti‐Infective Agents, Urinary; Anti‐Infective Agents, Urinary/adverse effects; Anti‐Infective Agents, Urinary/therapeutic use; Antibiotics, Antitubercular; Antibiotics, Antitubercular/adverse effects; Antibiotics, Antitubercular/therapeutic use; Cycloserine; Cycloserine/adverse effects; Cycloserine/therapeutic use; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

No evidence of the efficacy and safety of D‐cycloserine in the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease

D‐cycloserine is a broad‐spectrum antibiotic formerly used at high doses (500‐1000 mg/day) for the treatment of tuberculosis (TB). It has been suggested that D‐cycloserine might improve memory and other cognitive processes through its desired effects on N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) receptor function. It was not possible to extract the results from the first phases of two included crossover studies of D‐cycloserine for Alzheimer's disease and therefore the meta‐analyses are based on the included two parallel group 6‐month studies. The lack of a positive effect of D‐cycloserine on cognitive outcomes in controlled clinical trials with statistical power high enough to detect a clinically meaningful effect means that D‐cycloserine has no place in the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Background

Memory complaints are frequent in old age (Turvey 2000). Alzheimer's disease accounts for 50‐60% of all cases with dementia (Launer 1999). The cognitive malfunctioning in such cases relates to a reduction in cholinergic neurones of the brain and a subsequent decline in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine. The level of acetylcholine can be increased by cholinesterase inhibitors, and this class of drugs has been shown to improve memory and global functioning in patients with Alzheimer's disease (Birks 2006; Birks 2000). However, other neurone systems are also affected by this disease, for example there is evidence for a loss of glutamatergic neurones in the cerebral cortex and in the hippocampus (Procter 1989). Glutamate is an excitatory neurotransmitter for three different receptors, the N‐methyl‐D‐asparate (NMDA)‐receptor, the AMPA‐receptor, and the metabotropic receptor.

There is accumulating evidence that supports an important role for NMDA receptors in learning and memory (Bannerman 1995). Activation of these receptors has been reported to lead to long‐term potentiation (LTP) in the postsynaptic neurones when stimulated either by NMDA or by the natural agonist, glutamate. Since LTP has been suggested as a mechanism for memory formation, positive modulation of NMDA receptors may lead to memory and learning enhancement.

The activity of NMDA receptors can be modulated by activity of one of the receptors for the naturally occurring amino acid glycine, which appears to be co‐located in the brain with the NMDA receptor. These glycine receptors are also stimulated by the antibiotic D‐cycloserine in such a way that the effect of glutamate is enhanced (Chessell 1991). It has been suggested therefore that D‐cycloserine might improve memory and other cognitive processes. D‐cycloserine is a broad‐spectrum antibiotic formerly used at high doses (500‐1000 mg / day) for the treatment of tuberculosis (TB) and is a structural analogue of glycine and also of another amino‐acid, D‐alanine. D‐cycloserine has been shown to improve the performance of learning tasks in rats. Further support for its effect on memory was found by Jones 1991 who used healthy subjects pre‐treated with the anticholinergic drug scopolamine as a model for the memory impairment in Alzheimer's disease, and observed a positive effect on memory with low doses of D‐cycloserine. Adverse reactions to D‐cycloserine were frequent when the drug was used in the treatment of tuberculosis and restricted its use. They are dose‐related and involve the central nervous system (for example, somnolence, headache, tremor, dysarthria, vertigo, confusion, nervousness, irritability, psychotic states with suicidal tendencies, paranoid reactions, twitching, ankle clonus, hyper‐reflexia, paresis and tonic‐clonic or absence seizures). However, from animal and in vitro data it is likely that much smaller doses than those used for treating TB should achieve the desired effects on NMDA receptor function.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy and safety of D‐cycloserine in patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized, double‐blinded and unconfounded trials comparing D‐cycloserine with a control treatment.

Types of participants

Elderly people with probable or possible Alzheimer's disease diagnosed by validated research criteria, e.g. McKhann 1984, or by the clinical criteria established in the DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 1994) or ICD‐10 (WHO 1991) diagnostic classifications of disease.

Types of interventions

D‐cycloserine at any dose.

Types of outcome measures

Memory function as measured by psychometric tests e.g. the Mini‐Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein 1975) (primary outcome). Global assessment

Other cognitive functions, functioning regarding activities of daily living, institutionalisation, other types of service provision, carer strain and quality of life, and quality of life or psychological well‐being of patients (secondary outcomes).

Search methods for identification of studies

The trials were identified from a last updated search of the Specialized Register of the Cochrane Dementia and Cognitive Improvement Group on 2 January 2004 using the terms cycloserine and d‐cycloserine.

The Specialized Register at that time contained records from the following databases:

CENTRAL: July 2003 (issue 3);

MEDLINE: 1966 to 2003/09;

EMBASE: 1980 to 2003/08;

PsycINFO: 1887 to 2003/8;

CINAHL: 1982 to 2003/08;

SIGLE (Grey Literature in Europe): 1980 to 2002/12;

ISTP (Index to Scientific and Technical Proceedings): to May 2000;

INSIDE (BL database of Conference Proceedings and Journals): to June 2000;

Aslib Index to Theses (UK and Ireland theses): 1970 to March 2003;

Dissertation Abstract (USA): 1861 to March 2003;

ADEAR (Alzheimer's Disease Clinical Trials Database): to March 2003;

National Research Register: issue 1/2003;

Current Controlled trials (last searched April 2003) which includes:

Alzheimer Society GlaxoSmithKline HongKong Health Services Research Fund Medical Research Council (MRC) NHS R&D Health Technology Assessment Programme Schering Health Care Ltd South Australian Network for Research on Ageing US Dept of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Studies National Institutes of Health (NIH) ClinicalTrials.gov: last searched April 2003; LILACS:Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Literature: last searched April 2003.

The search strategies used to identify relevant records in MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycInfo and CINAHL can be found in the Group's module on The Cochrane Library.

Data collection and analysis

SELECTION OF TRIALS The initial selection of studies was performed independently and in parallel by two reviewers who screened the literature by reading the abstracts of references identified by the search. The two reviewers studied the full text of the references selected and independently made the final selection. Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion.

QUALITY ASSESSMENT OF STUDIES This was carried out as described in the Cochrane Reviewers' Handbook (Clarke 2003). Only trials with a low or moderate risk of bias (category A or B) were included. Data from studies where more than 50% of the subjects are drop‐outs would be discarded.

DATA COLLECTION Data for the meta‐analyses were based on reported summary statistics for each study.

For outcomes assessed as continuous variables, or as ordinal variables which can be approximated to continuous variables, the mean at endpoint and the mean change from baseline at final assessment was recorded for each treatment group, together with the standard deviations and numbers in each group. For binary outcomes, the numbers in each endpoint category were retrieved for each treatment group.

DATA ANALYSIS For continuous or ordinal variables, such as psychometric test scores, clinical global impression scales and quality‐of‐life scales, meta‐analyses are fairly straightforward in the situation where the included studies use the same outcome measures. The method of weighted mean difference can then be applied. When different scales are used in the studies, the method of standardised mean difference can be used.

If ordinal scale data appear to be approximately normally distributed, or if the analyses reported by the investigators suggest that parametric methods and a normal approximation are appropriate, then the outcome measures can be treated as continuous variables. The second approach, which may not exclude the first, is to concatenate the data into two categories which best represent the contrasting states of interest, and to treat the outcome measure as binary. For binary outcomes, the endpoint itself is of interest and the Peto method of the typical odds ratio will be used.

A test for heterogeneity of treatment effect between the trials was made using a chi‐square statistic. If no heterogeneity was indicated, a fixed effect parametric approach was applied.

The null hypothesis to be tested is that, for any of the above outcomes, D‐cycloserine has no effect compared with placebo.

Results

Description of studies

There were 4 included studies (EC6‐93‐06‐025, NC6‐90‐02‐009, Tsai 1998, Tsai 1999). Two of the studies were large, multi centre parallel group studies of six months duration (EC6‐93‐06‐025, NC6‐90‐02‐009). A computerised test system, the Cognitive Drug Research (CDR) (Wesnes 1992) was used to assess cognitive functioning. The Clinical Global Improvement scale (CGI) (Guy 1976) and the Clinician's interview Based Impression of Change (CIBIC) (Knopman 1994) provided global assessments. A wide range of fixed doses were used; one trial compared 10, 30 and 100 mg /day with placebo, the other 2, 10 and 200 mg/day. All doses were divided into two equal doses per day.

The other small studies were crossover trials, one with two phases of 4 weeks each and no washout between treatments (Tsai 1998), the other with 3 phases of 4 weeks each with one week washout between treatments (Tsai 1999). The two phase crossover trial compared 10 mg/day of D‐cycloserine with placebo. Evaluations included the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein 1975), the Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale (ADAS) for cognition (Rosen 1984), the Clinical Global Impression of Change (CGIC) (Guy 1976), and three assessments relating to activities of daily living, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) (Rosen 1984), Physical Self Maintenance scale (PSM) (Tsai 1998) and the Blessed Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS) (Tsai 1998). The three groups of the three phase trial tested 50 mg/day, 100 mg/day of D‐cycloserine and placebo. Evaluations included the cognitive subscore of the ADAS, the CGIC and the IADL.

The diagnosis of AD relied on accepted criteria such as DSM‐IV (APA 1994) and NINCDS‐ADRDA (McKhann 1984) for all trials.

Risk of bias in included studies

No trial described the method of randomization in detail.

Effects of interventions

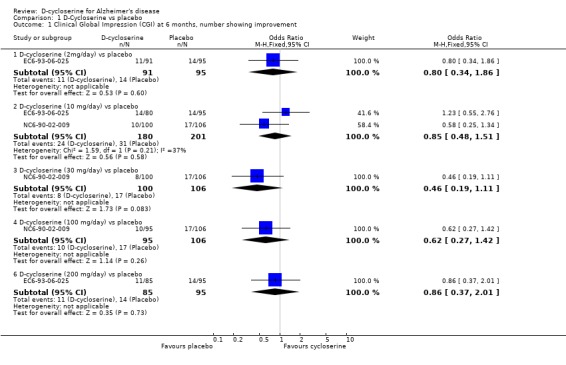

Only results from the parallel trials were pooled in meta‐analyses because it was not possible to extract results from the first phases of the crossover trials. The results for the cognitive tests were not reported in enough detail to allow them to be entered into meta‐analyses. Meta‐analyses of global assessment, numbers withdrawing before end of treatment, and numbers withdrawing before end of treatment due to adverse event were carried out. Analysis 01 01 displays the odds ratios with 95 % confidence intervals for numbers showing any improvement on the CGI, each dose level (2 mg ‐ 200 mg/day) analysed separately, at 6 months after start of treatment. There was no indication of an effect of D‐cycloserine compared with placebo.

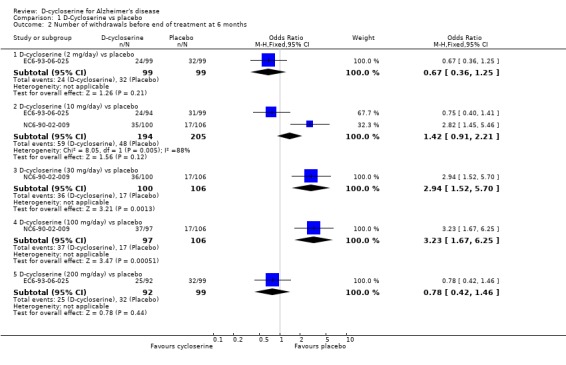

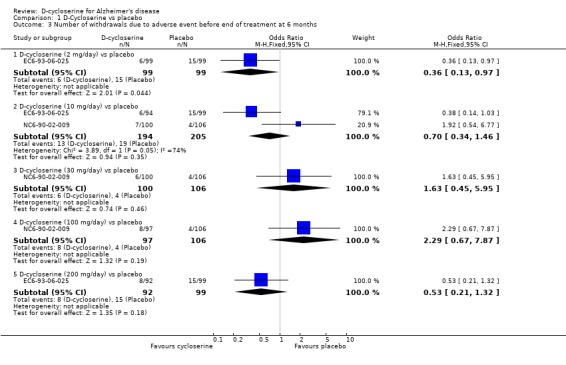

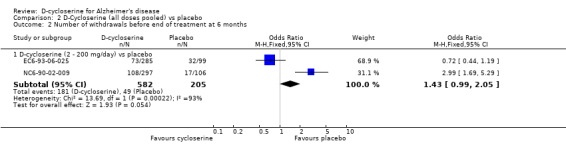

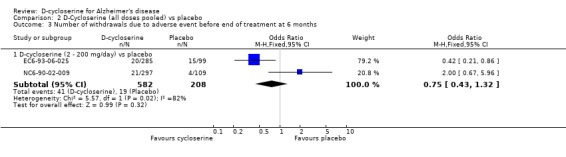

There was a significant effect in favour of placebo compared with D‐cycloserine (fewer dropouts from the placebo groups) at the 30 mg/day and 100 mg/day dose levels for withdrawals before the end of treatment at 6 months [OR 2.94, 95% CI 1.52, 5.70, P=0.001] [OR 3.23, 95% CI 1.67, 6.25, P=0.0005]. There was no evidence of a difference between placebo compared with D‐ cycloserine at any dose for withdrawals due to adverse events.

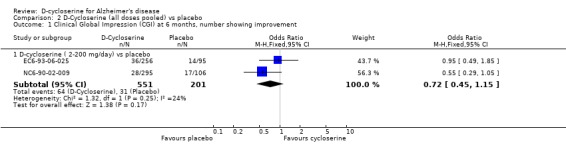

When all dose groups within a trial were pooled the meta‐analyses showed no evidence of differences between placebo compared with D‐cycloserine for CGI, adverse events or dropouts.

Discussion

The dose‐levels used in these studies varied markedly, probably because Jones 1991 observed an effect of lower, but not higher doses of D‐cycloserine in their scopolamine model for Alzheimer's disease. Therefore the trials appear to be pilot dose testing studies. The meta‐analysis was therefore carried out on the data from all doses tested. There was, however, no indication that D‐cycloserine has an effect on the Clinical Global Improvement Scale (CGI) (Guy 1976) at any dose level .Two of the RCT's had approximately 100 subjects in each dose level group. At a rate of improvement on the CGI by placebo of 15 %, which is near what was observed in these studies, this sample size would enable the detection of a rate difference of near 0.17 (alfa=0.05, power=80 %) at each dose level, corresponding to a number needed to treat of approximately 6. The results of the two larger studies in this overview thus show that D‐cycloserine is of no use in Alzheimer's disease. This conclusion contradicts the findings by Jones 1991 testing D‐cycloserine in a pharmacological model for Alzheimer's disease in healthy volunteers, which suggests that the model may not be adequate as an indicator of efficacy in AD patients.

Authors' conclusions

The lack of a positive effect of D‐cycloserine on cognitive outcomes in controlled clinical trials with statistical power high enough to detect a clinically meaningful effect shows that D‐cycloserine has no place in the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease.

Based on the available evidence further clinical studies on the effect of D‐cycloserine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease do not seem warranted.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Searle Inc, Illinois, USA for providing two unpublished reports on trials of D‐cycloserine in Alzheimer's disease.

Data and analyses

Comparison 1.

D‐Cycloserine vs placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clinical Global Impression (CGI) at 6 months, number showing improvement | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 D‐cycloserine (2mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 186 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.80 [0.34, 1.86] |

| 1.2 D‐cycloserine (10 mg/day) vs placebo | 2 | 381 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.85 [0.48, 1.51] |

| 1.3 D‐cycloserine (30 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 206 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.19, 1.11] |

| 1.4 D‐cycloserine (100 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 201 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.62 [0.27, 1.42] |

| 1.6 D‐cycloserine (200 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 180 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.37, 2.01] |

| 2 Number of withdrawals before end of treatment at 6 months | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 D‐cycloserine (2 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 198 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.67 [0.36, 1.25] |

| 2.2 D‐cycloserine (10 mg/day) vs placebo | 2 | 399 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.42 [0.91, 2.21] |

| 2.3 D‐cycloserine (30 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 206 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.94 [1.52, 5.70] |

| 2.4 D‐cycloserine (100 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 203 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.23 [1.67, 6.25] |

| 2.5 D‐cycloserine (200 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 191 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.78 [0.42, 1.46] |

| 3 Number of withdrawals due to adverse event before end of treatment at 6 months | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 D‐cycloserine (2 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 198 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.13, 0.97] |

| 3.2 D‐cycloserine (10 mg/day) vs placebo | 2 | 399 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.70 [0.34, 1.46] |

| 3.3 D‐cycloserine (30 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 206 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.63 [0.45, 5.95] |

| 3.4 D‐cycloserine (100 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 203 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.29 [0.67, 7.87] |

| 3.5 D‐cycloserine (200 mg/day) vs placebo | 1 | 191 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.53 [0.21, 1.32] |

Analysis 1.1.

Comparison 1 D‐Cycloserine vs placebo, Outcome 1 Clinical Global Impression (CGI) at 6 months, number showing improvement.

Analysis 1.2.

Comparison 1 D‐Cycloserine vs placebo, Outcome 2 Number of withdrawals before end of treatment at 6 months.

Analysis 1.3.

Comparison 1 D‐Cycloserine vs placebo, Outcome 3 Number of withdrawals due to adverse event before end of treatment at 6 months.

Comparison 2.

D‐Cycloserine (all doses pooled) vs placebo

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clinical Global Impression (CGI) at 6 months, number showing improvement | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 D‐cycloserine ( 2‐200 mg/day) vs placebo | 2 | 752 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.72 [0.45, 1.15] |

| 2 Number of withdrawals before end of treatment at 6 months | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 D‐cycloserine (2 ‐ 200 mg/day) vs placebo | 2 | 787 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.43 [0.99, 2.05] |

| 3 Number of withdrawals due to adverse event before end of treatment at 6 months | 2 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 D‐cycloserine (2 ‐ 200 mg/day) vs placebo | 2 | 790 | Odds Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.75 [0.43, 1.32] |

Analysis 2.1.

Comparison 2 D‐Cycloserine (all doses pooled) vs placebo, Outcome 1 Clinical Global Impression (CGI) at 6 months, number showing improvement.

Analysis 2.2.

Comparison 2 D‐Cycloserine (all doses pooled) vs placebo, Outcome 2 Number of withdrawals before end of treatment at 6 months.

Analysis 2.3.

Comparison 2 D‐Cycloserine (all doses pooled) vs placebo, Outcome 3 Number of withdrawals due to adverse event before end of treatment at 6 months.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 6 May 2008 | Review declared as stable | The lack of a positive effect of D‐cycloserine on cognitive outcomes in controlled clinical trials with statistical power high enough to detect a clinically meaningful effect means that D‐cycloserine has no place in the treatment of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Based on the available, evidence further clinical studies on the effect of D‐cycloserine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease do not seem warranted |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2001 Review first published: Issue 2, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 January 2004 | New search has been performed | February 2004: no new trials were found at the last update search in January 2004 |

| 17 January 2002 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | Randomized double‐blind parallel group placebo controlled duration: 6 months | |

| Participants | Country: 6 European countries + Israel 34 centres number of participants: 384 (40% male) average age: 71.8 year (range 49‐91) Inclusion criteria: 12<=MMSE <=24 3<= GDS <=5 17 item HAM‐D = < 17 mod Hachinski <=4 deficits in memory and one or more areas of cognition (orientation, language, praxis, attention, visual perception, problem solving, social function ) progressive worsening of memory diagnosis: mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease supported by CAT scan or MRI mean duration of disease 2.8 years Exclusion criteria: current or history of head trauma systemic disorder brain disorder or other neurological disorder with cognitive implications hypertension not controlled with diuretics history of epilepsy clinically significant abnormalities of thyroid function, folic acid or B12 cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, hepatic, gastrointestinal, infectious or haematological illness some concomitant medicines major depressive disorder no carer to assure compliance | |

| Interventions | 1. cycloserine 2 mg/day (1mg x 2) 2. cycloserine 10 mg/day (5mg x 2) 3. cycloserine 200 mg/day (100mg x 2) 4. placebo | |

| Outcomes | Cognitive Drug Research computerized test system (CDRCTS) CGI CIBIC | |

| Notes | A 7‐day placebo lead in phase preceded the 6 month treatment phase. | |

| Methods | Randomized double‐blind parallel group placebo controlled duration: 6 months | |

| Participants | Country: USA + Canada 29 centres number of participants: 410 (46% male) average age: 73.6 year (range 48‐91) diagnosis: mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease mean duration of disease 3.6 years mean MMSE 19.4 range 12‐27 Inclusion criteria: 12<=MMSE <=24 3<= GDS <=5 17 item HAM‐D =< 17 mod Hachinski <=4 deficits in memory and one or more areas of cognition (orientation, language, praxis, attention, visual perception, problem solving, social function ) progressive worsening of memory diagnosis: mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease supported by CAT scan or MRI mean duration of disease 3.6 years Exclusion criteria: current or history of head trauma systemic disorder brain disorder or other neurological disorder with cognitive implications hypertension not controlled with diuretics history of epilepsy clinically significant abnormalities of thyroid function, folic acid or B12 cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, hepatic, gastrointestinal, infectious or haematological illness some concomitant medicines major depressive disorder no carer to assure compliance | |

| Interventions | 1. cycloserine 10mg/day (5mg x 2) 2. cycloserine 30 mg/day (15mg x 2) 3. cycloserine 100 mg/day (50mg x 2) 4. placebo | |

| Outcomes | Cognitive Drug Research computerized test system (CDRCTS) CGI CIBIC | |

| Notes | ||

| Methods | Randomized double‐blind crossover placebo controlled 4 weeks + 4 weeks | |

| Participants | Country: USA number of participants: 10 (6 female 4 male) average age: 74.7 (8.5) years duration of symptoms 5.7(2.1) years MMSE 10‐25 diagnosis: NINCDS‐ADRDA for probable AD Hachinski <4 | |

| Interventions | 1. Cycloserine 15 mg/day 2. placebo | |

| Outcomes | MMSE ADAS IADL PSM Blessed ADL | |

| Notes | ||

| Methods | Randomized double‐blind crossover placebo controlled 4 weeks + 1 week washout + 4 weeks +1 week washout + 4 weeks) | |

| Participants | Country: USA number of participants: 17 (6 female 11 male) average age: 72.2 (7.3) year (range 58‐81) duration of symptoms 4.4(1.4) years (range 2‐6) mean MMSE 18.8 (5.3) mean ADAS‐Cog 23.5 (9.0) diagnosis: NINCDS‐ADRDA for probable AD DSM‐IV criteria for dementia of Alzheimer's type 12<= MMSE <= 26 Hachinski <4 Exclusion criteria: significant medical, psychiatric or neurological illness other than AD | |

| Interventions | 1. Cycloserine 50 mg/day 2. Cycloserine 100 mg/day 3. placebo | |

| Outcomes | ADAS‐Cog CGIC IADL | |

| Notes | ||

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Randolph 1994 | Only responders from the first phase of study were included, and the results are thus biased |

Contributions of authors

‐RWJ: all correspondence; updating review ‐ARO: drafting review versions; selection of data; extraction of data

‐CDCIG Contact editor: Jacqueline Birks

The Group deeply regrets the death of Knut Laake in May 2003. He was responsible for the original review. His contributions included drafting review versions; selection of trials; extraction of data and interpretation of data analyses.

Sources of support

Internal sources

No sources of support supplied

External sources

University of Oxford, UK.

Declarations of interest

None known

Stable (no update expected for reasons given in 'What's new')

References

References to studies included in this review

- Pauvlik JM. Searle clinical research report. A two year, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind controlled parallel group study of cycloserine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease with six months placebo control. Report No. EC6‐93‐06‐025, July 30, 1993. Skokie, IL: GD Searle, 19931993.

- Fakouhi TD, Jhee SS, Sramek JJ, Benes C, Schwartz P, Hantsburger G, Herting R, Swabb EA, Cutler NR. Evaluation of cycloserine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology 1995;8(4):226‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Mohr E, Knott V, Sampson M, Wesnes K, Herting R, Mendis T. Cognitive and quantified electroencephalographic correlates of cycloserine treatment in Alzheimer's disease. Clinical Neuropharmacology 1995;18(1):28‐38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Pauvlik JM. Searle clinical research report. A two year, multicenter, randomized, double‐blind controlled parallel group study of cycloserine in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease with six months placebo control. Report No. NC6‐93‐06‐009, September 29, 1993. Skokie, IL: GD Searle, 19931993. ; Schwartz BL, Hashtroudi S, Herting RL, Schwartz P, Deutsch SI. d‐Cycloserine enhances implicit memory in Alzheimer patients. Neurology 1996;46(2):420‐424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai GE, Falk WE, Gunther J. A preliminary study of D‐cycloserine treatment in Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 1998;10(2):224‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai GE, Falk WE, Gunther J, Coyle JT. Improved cognition in Alzheimer's disease with short‐term D‐cycloserine treatment.. American Journal of Psychiatry 1999;156(3):467‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

- Randolph C, Roberts JW, Tierney MC, Bravi D, Mouradian MM, Chase TN. D‐cycloserine treatment of Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 1994;8(3):198‐205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd Edition. Vol. III revised, Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Vol. IV, Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bannerman DM, Good MA, Butcher SP, Ramsay M, Morris RGM. Distinct components of spatial learning revealed by prior training and NMDA receptor blockade. Nature 1995;378(6553):182‐186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks J, Grimley Evans J, Iakovidou V, Tsolaki M. Rivastigmine for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2000, Issue 4. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001191] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birks J, Harvey RJ. Donepezil for dementia due to Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006, Issue 1. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001190.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chessell IP, Procter AW, Francis PT, Bowen DM. D‐cycloserine, a putative cognitive enhancer, facilitates activation of the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptor‐ionophore complex in Alzheimer brain.. Brain Research 1991;565(2):345‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M, Oxman AD, editors. Cochrane Reviewer's Handbook 4.2.0 [updated March 2003]. The Cochrane Library 2003, Issue 2. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Solstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini‐mental state": a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 1975;12:189‐98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Dept Health, Education and Welfare Publication (ADM) 76‐338 1976;2:218‐22. [Google Scholar]

- Jones RW, Wesnes KA, Kirby J. Effects of NMDA modulation in scopolamine dementia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1991;640:241‐4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, Knapp MJ, Gracon SI, Davis CS. The Clinician Interview‐Based Impression (CIBI): a clinician's global change rating scale in Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1994;44(12):2315‐21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Launer LJ, Andersen K, Dewey ME, Letenneur L, Ott A, Amaducci LA, et al. Rates and risk factors for dementia and Alzheimer's disease: Results from EURODEM pooled analyses. Neurology 1999;52(1):78‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: Report of the NINCDS‐ADRDA work group under the auspices of the Department of health and human services Task Force on Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1984;34:939‐44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Procter AW, Stirling JM, Stratmann GC, Cross AJ, Bowen DM. Loss of glycine‐dependent radioligand binding to the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate‐phencyclidine receptor complex in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neuroscience Letters 1989;101(1):62‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL. A new rating scale for Alzheimer's disease. American Journal of Psychiatry 1984;141:1356‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turvey CL, Schultz S, Arndt S, Wallace RB, Herzog R. Memory complaint in a community sample aged 70 and older. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 2000;48(11):1435‐41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wesnes K, Simpson P, White L, Pinker S. The cognitive drug research computerized assessment systems for elderly, AAMI and demented patients. Journal of Psychopharmacology 1992;6:108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organisation (WHO). ICD‐10. Tenth revision of the International Classification of Diseases. Chapter V (F): Mental and Behavioural disorders (including psychological development). Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Mental and behavioural disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines 1991. [Google Scholar]

References to other published versions of this review

- Jones R, Laake K, Oeksengaard AR. D‐cycloserine for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 2. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003153] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]