Abstract

Purpose

The internet is integral to young people, providing round-the-clock access to information and support. Young people with cancer report searching for online information and support. What they search for and why varies across their timeline and is mainly driven by negative emotion. We sought to understand how health care professionals (HCPs) perceived online information and support for young people with cancer.

Population and methods

Semi-structured interviews with eight HCPs across the UK informed the development of a survey, completed by 38 HCPs. Framework analysis was used to identify key themes and the survey was analyzed descriptively.

Results

Seven themes emerged as integral to HCP’s perceptions of online information and support, these included: views about young people’s use of online resources; how needs change along the cancer timeline; different platforms where HCPs refer young people to online; whether young people’s online needs are currently met; recognition of the emotional relationship between young people and the internet; barriers and concerns when referring young people to online resources; and strategies used in practice.

Conclusion

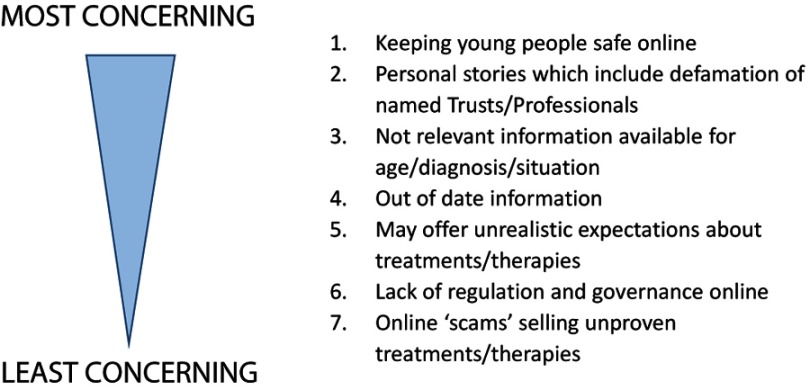

Professionals play an important role in signposting young people to online resources, where they are confident about the accuracy and delivery of information. The biggest perceived barrier to facilitating online access was the cost to the NHS, and most concerning factor for HCPs was keeping young people safe online. There is a need to develop online resources specific for young people on psychosocial topics beyond treatment to support young people and HCPs through this period.

Keywords: communication, internet, teenager, young adult, adolescent, unmet needs, support, information, online

Introduction

Teenage and young adulthood is a complex developmental stage, which is known to be severely disrupted by a cancer diagnosis.1,2 Key to assisting young people to manage the challenges imposed through a cancer diagnosis is provision of accurate and timely information. Health care professionals (HCPs) are an essential conduit in this process and communication has been identified as a core skill and mediator for good quality of life and psychosocial wellbeing.3 Further to this when information is not communicated effectively, this can add to young people’s distress.4 The teenage and young adult workforce is gaining recognition as requiring unique skills compared to HCPs who deliver care to children or older adults.3,5,6 Professionals caring for young people are required to communicate information on young people’s issues, such as sexuality and relationships with family, peers, and partners, in addition to cancer-related information.7 The ability to discuss sensitive issues has been identified as a core skill, with communication being recognized as one of the top areas of competence for caring for a young person with cancer.6

To date, work undertaken to explore young people’s information and communication needs focuses mainly on what information young people need, with less emphasis on how this is delivered.8–11 Currently, 90% of young people aged 16–24 years in the United Kingdom (UK) own a smartphone12 so there is the assumption that this is a medium well suited to the delivery of information to young people. However, it has been reported that the primary activity for young people using their smartphone is for social networking, and not information seeking.13

We previously reported young people’s experiences of using online resources following a cancer diagnosis and showed that online use varied across the cancer timeline: searching for factual cancer information shortly after diagnosis, followed by a lull during treatment where young people used the internet for entertainment and to keep in touch with peers. Toward the end of treatment online information seeking increased as young people reintegrated into their lives. Searching was generally driven by negative emotions, and professional attitudes toward online information often influenced young people seeking information online and how they felt about it.14

Previous studies have reported that HCPs were reluctant to direct patients to internet resources; however, more recent studies are showing a more positive attitude from HCPs about the information in the internet. This may reflect an increase in the quality of information that is being posted.15 However, the accuracy of online information continues to be barrier to HCPs directing patients to the internet for information.15–20 Having established how young people utilize the internet when they have been diagnosed with cancer,14 we sought to understand how far current digital/online needs were currently being met by existing online platforms and resources, from the perspective of HCPs who care for them.

Materials and methods

This was a multi-center, mixed methods study employing semi-structured interviews and a quantitative survey, involving HCPs from across the UK.

Study participants

HCPs involved in the care of young people with cancer were invited to take part in a telephone interview or survey, including a range of HCPs representative of the multi-disciplinary team.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Health Research Authority and London Brent National Health Service Research Ethics Committee (16/LO/1661).

Data collection

Interviews

Key HCP stakeholders involved in the care of young people with cancer were invited to take part in a semi-structured telephone interview on their views of young people accessing online information and support. Professionals were recruited from different geographical locations across the country, reflecting different models of care and access to services for young people. Additionally, HCPs were purposefully identified by the research team to ensure a broad range of professionals’ groups were represented. They were sent an information sheet with study details and asked to contact the research team to arrange an interview if they were willing to take part. Participants were emailed a consent form, which they signed and returned to the team via email. At the beginning of the interview, consent was confirmed verbally, opportunity for questions given, and they were informed the interview could be stopped at any point.

A semi-structured interview schedule was developed based on the findings of the young person’s study14 and explored key themes as well as topics specific to professionals. An example of the interview guide is seen in Box 1. In particular, we examined if they referred young people to any particular online platforms, how they felt about signposting to online resources, and the sort of reassurances they required before recommending online sources of information and support to young people. These data informed the survey to be distributed to a wider group of HCPs.

Box 1.

Interview topic guide

| Introduction | Thank you for agreeing to share your views with us. Before we start, I would like to remind you that there are no right or wrong answers, you can stop at any time and what you share with us today will be kept confidential and anonymous. Do you have any questions before we start? |

| Professionals views on online digital information needs | What are your thoughts on the digital information needs of young people following a cancer diagnosis? Does this change throughout their cancer journey? |

| Professionals practice and beliefs | Do you currently refer young people to any particular online platforms? If yes, where do you refer them to? Why? How comfortable do you feel in doing this? What are the most helpful, sites, format? Any difficulties you think young people encounter looking for online information? Which sites do you think young people use the most? Purpose of use (e.g., to seek support for oneself vs provide support for others)? What are the key facilitators for professionals to refer a young person to online support/information platforms? What are the key barriers for professionals to refer a young person to online support/information platforms? What are the advantages of online information/support for young people? What are the disadvantages of online information/support for young people? |

| Optimising online information for young people with cancer | What are the main changes you would make for online information to be more accessible for young people? Prompts: Cover each part of the cancer trajectory

|

| Wrap up | Thank you for sharing your views with us. Is there anything you would like to add? |

Survey

The survey was developed to address and build on key themes from the interviews with professionals. Six experts experienced in questionnaire development and/or working with young people with cancer reviewed the first draft of the survey: two doctors, two nurses, and two youth support co-coordinators. To establish content validity, the six reviewers were provided with structured guidance to direct feedback, as well as the opportunity for free text comment. Following this review process, the survey was amended and re-circulated to the reviewers to confirm readiness for use.

The survey was distributed online through the Teenage Cancer Trust funded professional email list, the TYAC membership email list (Teenage and Young Adults with Cancer, the professional organization representing TYA HCPs in the UK), professional forums and Twitter. Participants could complete the survey as a word document and return by email or a link to an online version. Return of the survey/completion was taken as consent. Survey returns were increased through targeted tweets to professional organizations.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed and anonymized. Key themes were identified which informed the development of a framework for analysis. Framework analysis was used to explore the data in more depth through a series of structured steps: becoming familiar with the transcripts, indexing the transcripts according to the framework, charting data from the transcripts, and finally, charts were reviewed and interpreted by the team.21 Survey data were analyzed descriptively in Microsoft Excel. The survey results were mapped alongside the qualitative findings; and are presented to substantiate the themes that arose from the interviews.

Results

A total of 46 HCPs participated in the study (Table 1). Eight professionals from the multi-disciplinary team took part in the semi-structured interviews, including nurses, doctors, and youth support coordinators. All interviewees had over 3 years of experience working with young people with cancer. Thirty-eight professionals participated in the online survey (Table 1).

Table 1.

Health care professional participant characteristics

| Interviews (n=8) n (%) |

Survey (n=38) n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Role | ||

| Medical Doctor | 2 (25) | 2 (5) |

| Nurse | 4 (50) | 11 (29) |

| Youth Support Coordinator | 2 (25) | 3 (8) |

| Social Worker | 0 | 13 (34) |

| Other | 0 | 9 (24) |

| Place of work | ||

| Principal Treatment Centre (PTC) | 8 (100) | 20 (53) |

| Designated Hospital (DH) | 0 | 2 (5) |

| Across both PTC and DH | 0 | 10 (26) |

| Other | 0 | 6 (16) |

| Length of time working with young people with cancer | ||

| Less than 1 year | 0 | 5 (13) |

| Between 1 and 3 years | 0 | 6 (16) |

| More than 3 years | 8 (100) | 27 (71) |

| Total | 8 | 38 |

Seven themes emerged from the interviews and were supported by survey results:

Views about young people’s use of online resources

How young people’s online needs change along their cancer timeline

Where professionals refer young people to online

Are young people’s online needs currently being met?

Recognition of the emotional relationship between young people and the internet

Barriers and facilitators for professionals when referring young people to online resources

Strategies used in practice

Views about young people’s use of online resources

Professionals were accepting and generally positive toward the increasing use of online information and resources in health care. Online resources were described as a valuable tool to assist young people in finding information and support. Professionals recognized that young people live in a “digital world”:

I think with information they would go straight to website or digital sources. Just because it’s the way they’re living their lives.

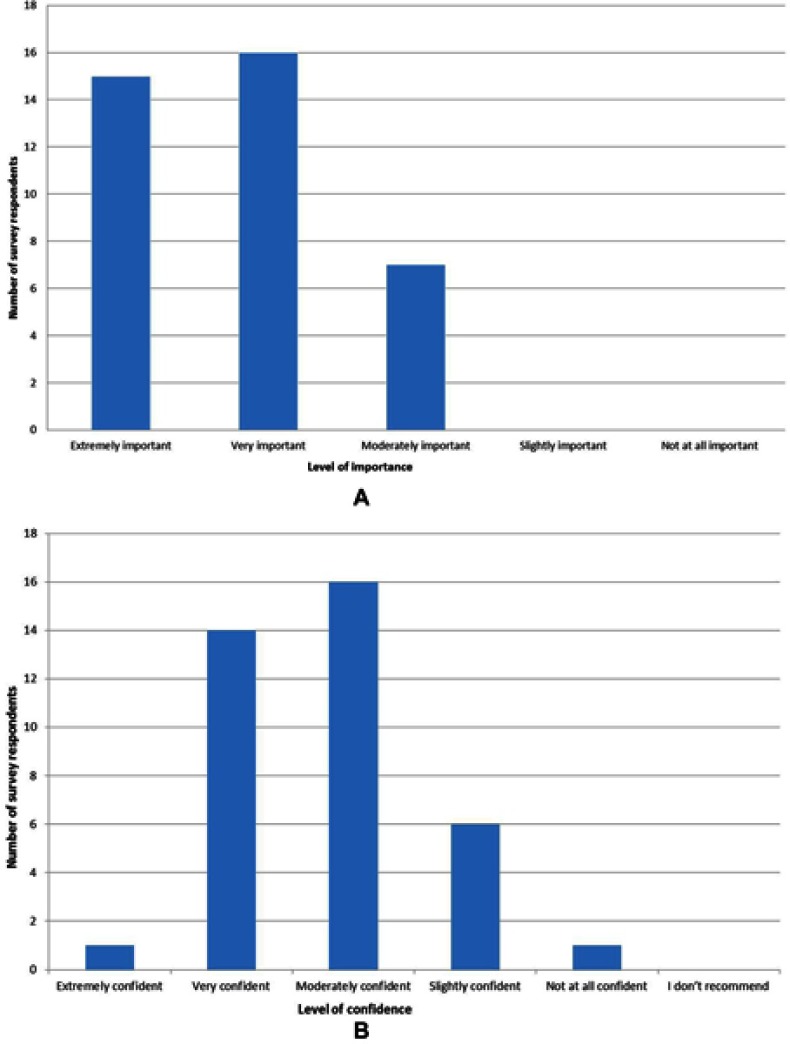

It was noted that in England digitalization of health services was part of the NHS Five Year Forward agenda22 and should be embraced as opposed to shied away from. Professionals recognized the need to become comfortable with using and understanding online resources in order to successfully guide and support patients and their families online, they also felt it was part of their role to facilitate safe use and access to online resources. This was supported by survey respondents which showed it was important for the treatment team to facilitate young people’s access to health information online (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

(A) How important do you think it is for the treatment team to facilitate young people to access health information online? (B) How confident do you feel recommending online resources for young people with cancer?

Professionals discussed the need to have an awareness and understanding of the online world that young people used and accessed. It was accepted that most young people engaged well with information and resources that were online, potentially more readily than information in other formats such as leaflets. Professionals felt that resources should be geared and designed to meet the needs of young people, rather than “young people trying to fit in with what we’ve got”. They also recognized they had an element of power/control over some young people in terms of what they looked at online as some young people were very much guided by HCPs looking after them as to whether to look online or avoid it.

However, it was also highlighted not all young people were immersed in digital technology. Professionals emphasized that young people had different information and support needs, and varying levels of engagement with the internet, therefore the emphasis on online information needed to be tailored to the needs of the individual patient or family:

For some people they may have consulted ‘Dr Google’ in the build-up to their diagnosis, so they may be less scared to look afterwards, whereas other people would avoid it … I don’t know if there’s a hard and fast rule as to who uses it for what.

Professionals reported a lack of knowledge about the online resources that were available for young people. This was reflected in their confidence to recommend online information and resources to young people. All survey respondents recommended young people to online resources in some way; however, some were more confident to do this than others: most HCPs (n=30; 79%) reported feeling very/moderately confident when recommending young people to online resources (Figure 1B).

While professionals recognized the importance of online information and support in the care of young people, they advocated a need for face-to-face information exchange and written information. Professionals advocated signposting young people to online resources as an adjunct to the information provided in face-to-face conversations, and were clear that online information could not replace face-to-face interactions:

Online will never detract from face to face conversations, it should be there to supplement it. And we will never get it right for everybody.

How young people’s online needs change along their cancer timeline

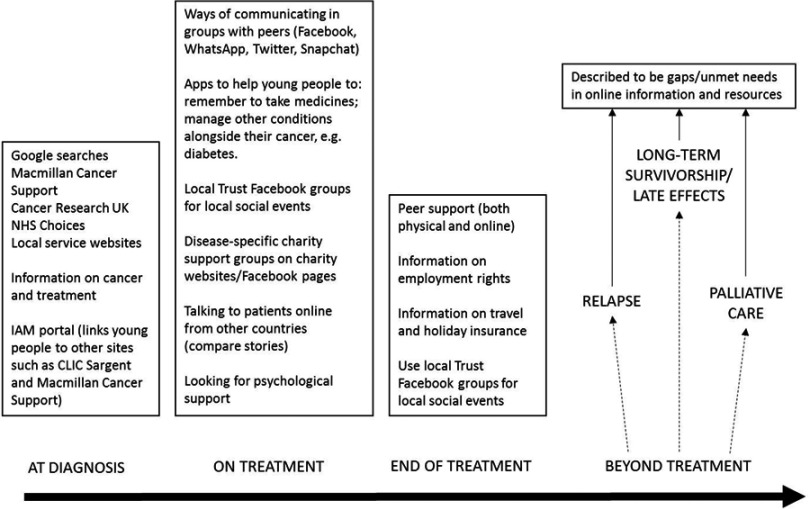

Professionals reported variation in young people’s online information and support needs at distinct stages of their cancer diagnosis and treatment timeline. They felt that young people’s needs were contextual and based on individual circumstances, particularly at the latter part of their cancer timeline when they were approaching the end of treatment and moving back into what was sometimes referred to as “normal” life. Four key periods of time emerged where unique needs were described: at diagnosis; during treatment; end of treatment; and beyond treatment. Professionals discussed some of the online needs they knew, or believed young people had along this timeline and what information or support young people were or might be looking for (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Professional’s perceptions of what young people access online at different points in their cancer timeline.

At diagnosis

Professionals described a “flurry” of searching online for information immediately after diagnosis. This was usually for factual information about their cancer and treatment:

When they’re diagnosed, they want to know every bit of detail … disease-specific information … statistics, survival rates, things they should be doing to help themselves get better.

However, it was recognized that the need to search for information online at this stage was individual to the young person; “some do, some don’t.” Professionals recognized some young people were not able to process any more information at diagnosis, and therefore did not want to seek information online:

They just need to know what they need to know to get through the next day.

During treatment

During treatment, it was recognized that many young people’s main source of information was their treatment team and felt that often they were satisfied with the information they were provided with. Professionals described this stage as a “lull” in young people’s online information-seeking behavior; however, during treatment young people used the internet to seek support from peers. The importance of connecting with friends and family during treatment to get peer support was acknowledged, and this peer support was often found through online social media platforms:

In the middle of treatment they might be feeling a bit isolated, so they might look to do chat rooms and things like that.

Professionals observed the need for peer support grew and evolved over the course of cancer treatment, with an increasing desire to hear from other young people and share experiences as they began to experience the physical effects of their treatment, as well as the social effects and isolation that came with cancer treatment.

End of treatment

As young people approached the end of treatment, HCPs perceived their use of the internet to increase, as often they were starting to think, “What does that mean for me now?” It was reported that the information young people were searching for online was more holistic and individually driven, often around topics such as continuing education, work, travel, or financial issues. Furthermore, it was recognized that young people searched for peer support “further down the line” in their cancer timeline. The peer support at the end of treatment was more focused around sharing experience, and understanding the experience of others. There was a recognition that much of the young person-friendly information and support online was geared toward cancer treatment and survival, as opposed to what happened at the end of treatment.

Beyond treatment

Beyond treatment was identified by professionals as a period where there was a gap in online information and resources available to young people. In particular, the lack of online resources to support young people who were receiving palliative care:

Late effects/aftercare - there’s stuff out there now, but it’s trying to make it young-adult friendly … in the context of a lot of the online stuff it’s about survival. ‘I’ve got a cancer which I’m never going to survive, but I might live for five years … where do I get my information in that context?’ So I think they’re the kind of things which there are some significant gaps in.

Where professionals refer young people to online

Professionals often referred young people to online resources to supplement the information that they provided. The websites and online resources which HCPs referred young people to included national charities (Macmillan Cancer Support, Cancer Research UK), disease-specific websites (e.g., Sarcoma UK, Bone Cancer Research Trust), apps, social media, and local hospital websites. The key reasons HCPs chose some websites or applications to refer young people were:

Young people and their families had reported finding it useful

Robust and evidence-based information

Clear, navigable format to the site

Appropriate information and reading standards

Peer-reviewed and trusted

Professionals’ knowledge and awareness of what online resources existed for young people was described as both a facilitator and a barrier to referring young people to online resources. Knowledge and awareness of online resources was investigated further in the survey. Professionals were asked to rate their awareness and knowledge of existing resources for cancer-specific, and holistic (e.g., mental health, finances, body image) information and support for young people. Differences were shown between the knowledge and awareness of HCPs around these two types of information and support. The majority of professionals (n=29; 78%) had very good/moderate awareness and knowledge of online information and resources that were cancer-specific, i.e. , related to disease and treatment. Similarly, professionals (n=29; 78%) had very good/moderate awareness of what currently existed online for young people’s holistic information and support needs. However, their knowledge of what was available did not correspond with whether they felt that the internet met young people’s information and support needs.

Are young people’s online needs currently being met?

The survey explored professional’s views on how much existing online resources and information met young people’s needs at each stage of the timeline. Professionals referred to additional phases of the timeline such as relapse and palliative care. Table 2 shows the results from the survey of the topics where respondents felt that existing online resources met the needs of young people with cancer, and their parents/caregivers. Factual information about a young person’s cancer and treatment “during treatment” was deemed the online information that most met the needs of young people (n=27; 71%) . In comparison, fewer HCPs considered current online factual information about cancer and treatment to meet the needs of young people in relapse (n=9; 24%), long-term survivorship (n=9; 24%), and palliative care (n=4; 11%).

Table 2.

Areas that met young people’s information needs according to their cancer timeline

| During treatment n (%) |

End of treatment n (%) |

Relapse n (%) |

Long-term survivor n (%) |

Palliative care n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factual information about cancer and treatment | 27 (71) | 12 (32) | 9 (24) | 9 (24) | 4 (11) |

| Psychological information and support | 12 (32) | 7 (18) | 4 (11) | 4 (11) | 5 (13) |

| Finance, insurance, education, and employment | 17 (45) | 13 (34) | 7 (18) | 5 (13) | 6 (16) |

| Sex, fertility, relationships, and body image | 16 (42) | 11 (29) | 4 (11) | 9 (24) | 2 (5) |

| Parent/caregiver information needs | 18 (47) | 5 (13) | 4 (11) | 3 (8) | 4 (11) |

Only 32% (n=12) of participants felt existing online resources met the psychological information and support needs of young people during treatment. For later stages of the timeline from the “end of treatment and beyond”, less than a fifth of professionals felt there were existing resources that meet the psychological needs of young people. Particularly for young people experiencing relapse, 11% (n=4) felt that online resources for psychological support were inadequate (Table 2).

Similar to other categories of information, more HCPs (n=17; 46%) considered existing resources on finances, insurance, education, and employment to meet the needs of young people during treatment. Fewer felt that young people’s needs were met at the end and beyond treatment, in terms of information about finances, education, and insurance (Table 2). Less than half of survey respondents felt that information on sex, fertility, relationships, and body image met the needs of young people during treatment (n=16; 43%). Professionals considered this type of information to better meet the needs of young people during treatment, and less across other stages of the cancer timeline; particularly for those receiving palliative care (n=2; 5%).

In addition to the needs of young people the online information and support needs of parents/caregivers emerged in the interviews:

I think there’s very little evidence out there of what parents need. I think there’s evidence about parents of paediatric patients, I think there’s evidence for parents of childhood survivors but I think for TYAs it’s tricky … I think they do need something … you have to think about blended families as well …

Further exploration in the survey indicated that online information best met the needs of parents/carers at the point of diagnosis or during treatment but beyond treatment, less than 20% of the respondents felt online information and support met the needs of parents/caregivers (Table 2).

Recognition of the emotional relationship between young people and the internet

Professionals organically described the emotional responses young people were likely to feel when engaging with online resources. Professionals described some of the emotions driving online searching such as “panic” and “curiosity”, in particular immediately after diagnosis:

That panic stage of looking for all the information they could possibly get.

Professionals highlighted their practice and provision of advice and support should be sensitive to these negative emotions:

We have to mindful that when they’re first diagnosed, or when they’re in the clutches of desperation and there’s no more treatment left, they start looking for alternatives.

It was also recognized that young people had emotional responses to looking at information online. Professionals understood that some of the information, facts, and figures or “horror” stories that young people could find online may be scary. However, they also described positive emotional outcomes, such as “reassurance” and “comfort”, and that peer support provided by social networking platforms could be helpful:

The Facebook page … like a bit of a comfort blanket for them …

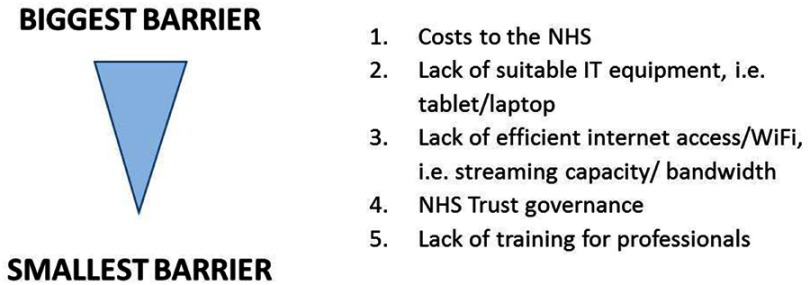

Barriers and facilitators for professionals when referring young people to online resources

Professionals discussed facilitators, which encouraged and enabled them to direct young people toward online sources of information or support (Table 3) and conversely barriers to them feeling comfortable or enabled to do this (Table 4). The survey asked HCPs to rank barriers as to what they perceived to be the biggest to the smallest barrier. These were the tangible, practical barriers that emerged in the interviews. The cost to the NHS was perceived to be the biggest barrier to young people accessing the internet in the NHS. A lack of suitable IT equipment, lack of efficient internet access, NHS Trust governance and lack of training for professionals were all perceived as equitable in how much of a barrier they were to young people accessing the internet in the NHS (Figure 3).

Table 3.

Facilitators for professionals referring young people to online resources

| Theme | Details |

|---|---|

| The online resource |

|

| Professional’s knowledge, awareness and role |

|

| Resources |

|

| Recommendations/endorsement/brand |

|

| Competency of the young person |

|

Table 4.

Barriers for professionals referring young people to online resources

| Theme | Details |

|---|---|

| Professional’s awareness and knowledge |

|

| Nature of the online environment |

|

| Regulations and governance |

Individual Trust regulations for use of the internet Uncertainty about how some of the charity’s online communities are regulated and governed |

| Vulnerability of young people |

|

Figure 3.

Professionals’ perceived barriers to internet access for young people in the NHS.

In the interviews, HCPs discussed their own concerns surrounding managing young people’s access and engagement with online information and resources. This emerged as something separate to the challenges that young people faced and the disadvantages that came with the internet as a source of information and support. Seven barriers, which were the most concerning for professionals were identified from interviews and ranked by survey respondents from what they felt were most concerning, to least concerning (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Concerns professionals have about recommending online resources to young people.

Strategies used in practice

Professionals employed a range of strategies to assist them in managing their anxieties around young people’s online activity describing strategies to assist them with referring young people to online resources and that enabled them to feel confident and comfortable in doing this. Furthermore, they employed strategies to protect young people online and assist colleagues in doing this.

Use of caveats

Professionals frequently mentioned using caveats when discussing online resources with young people, and they forewarned young people of the pitfalls of searching for information on the internet:

I tend to say at the beginning, ‘the internet is amazing but it’s sometimes a very dangerous thing … what you may find is information that’s not relevant to you or your diagnosis’.

They also used caveats with trusted websites, to illustrate that not all online information would be relevant to them. If young people accessed social media sites, such as hospital Facebook groups, HCPs reiterated to young people that these were not intended for medical use, and to refer to their treatment team when they required medical information.

Sharing resources

Professionals advocated sharing useful and recommended online resources between colleagues and other members of the multi-disciplinary team. Some had a “filtering system” to assist them to identify sources of reliable and focused cancer information for young people, e.g., having support workers who identified new websites that would be useful and flagged them to the rest of the team. Twenty-nine (73%) participants in the survey responded that they were extremely or highly likely to use a library of approved resources.

Information exchange with the young person

Professionals did not promote websites or resources to young people per se; rather they guided young people toward specific sites they felt would be useful and were also trustworthy and credible. They were cautious about directing young people to look at blogs and forums, either on charity websites or personal/private blogs because the content was not always appropriate or trustworthy. They evidenced these concerns with specific examples where young people had become upset, worried, frightened, or confused by a piece of information or experience found in a blog or forum. Professionals managed this through reviewing the source with the young person so they could alleviate fears and anxieties, or answer questions and issues that may have been worrying or confusing the young person:

I think you can get lost in the Internet and sucked into stuff through, I don’t know, blogs or people’s experiences or people trying to sell things or prey on vulnerable people … information can look very credible on the internet and it might not be … I think we’re always quite conscious about, ‘If you find somebody spouting a cure that’s definitely something to print off and bring in’

Due to the fast-pace and rapidly changing nature of the internet, professionals mentioned the challenges of having out of date web links. To combat this, they gave young people the names of the key charities/sources of support and information for young people to find the website themselves.

Professionals pre-empting by searching themselves

Professionals’ described conducting google searches to see what young people would have found as their “top hit”, especially in the case of an unusual diagnosis. They described how this helped to manage a young person’s information needs and anxieties, and allowed them to pre-empt questions that the young person may ask.

Education and training

Professionals recognized a need for increased understanding of what young people looked for online and why, to assist them in conversations they had with young people about using the internet for information and support. When asked whether professionals had received any training on advising young people with cancer about accessing online resources, the majority, 87% (n=32) of respondents had not received any training. Training for HCPs on advising young people with cancer about accessing online resources could be a facilitator if it was provided and survey data indicated that HCPs would be likely to undertake training if it was offered. If there was official training available, 35 (95%) felt that they would be extremely/very/moderately likely to attend it.

Discussion

We set out to examine how far young people’s online needs were being met by existing online platforms and resources from the perspective of professionals caring for them. There was consensus among HCPs that the internet is a valuable resource for young people who are living with and beyond cancer, and felt it was part of their role to facilitate young people to access online resources safely. It was recognized that resources should be geared and designed to meet the needs of young people.

Similar to young people’s views,14 HCPs were generally satisfied by the factual information about cancer and treatment available online for young people who were at diagnosis or on treatment. In contrast to previous studies with adult cancer patients that indicated a reluctance to recommend online information,15,20,23,24 we found HCPs directed young people to websites from the point of diagnosis, especially those with a reported reputation for being accurate, such as Macmillan Cancer Support, Cancer Research UK, and NHS Choices. Professionals described variation in online use throughout the cancer timeline similar to previous reported young people’s views,14 and felt existing online information and resources for young people beyond treatment, who were relapsed, in long-term follow-up and receiving palliative care were lacking. The lack of information for young people at the end of life is recognized as being an unmet need, whether this is delivered face-to-face or online.25 Information on fertility, relationships, body image, and psychological information and support were also felt to be lacking which was comparable to reports from young people.14 Professionals also described, similar to young people,14 that negative emotions drove searching for information or support online, and they needed to be aware of those young people who may be searching for answers online, at a time when they may be feeling particularly upset or anxious.

One of the benefits of delivering information through the internet is sharing information about sensitive issues, where the patient (or HCP) may not feel comfortable in discussing this.24 Similar to young people,14 HCPs felt that the internet should not be seen as a replacement, but to supplement and enhance face-to-face consultations.

Keeping young people safe online was a big concern for HCPs, and there was anxiety over their inability to control what young people looked at online, or who they may interact with. This has been reported previously,24 especially concern over the availability of videos online and the impact it could have on patients viewing procedures they were scheduled to have. Other concerns professionals have previously reported was difficulty patients could have in understanding online information, information giving young people unrealistic expectations about treatment or request treatment that was not suitable.17,24 Likewise, HCPs in our study were concerned that young people could access irrelevant information for their age/diagnosis/situation and the presence of out of date information.

Finally, HCPs in the current study indicated an interest in receiving education and training on guiding young people when they were accessing online resources. The fact that a lack of training was perceived as a barrier, and the enthusiasm of survey respondents to engage in official training should it be offered, indicated training should be offered for HCPs who support young people. This is something that has not been explored in much detail in previous studies. Perocchia et al,26 reported the evaluation of an initiative by the National Cancer Institute Cancer Information Service. They launched the Digital Divide Project, of which one aspect was to support health care providers to be more knowledgeable about cancer resources on the Internet. There was limited evidence to support professionals referring patients to online resources (project ran in early 2000s), but there was evidence that patients who used online resources had better communication and decision-making with their health care teams. Those attending structured workshops reported an increase in confidence in recommending online resources and this was more so for professionals in community settings compared to specialist cancer settings. This suggests education could be beneficial in supporting HCPs in using online resources more effectively.

The current study had a number of limitations: we aimed to include 15 HCPs to interview, however recruited and interviewed eight. While they provided rich and detailed description of online resource use, they were all from specialist teenage and young adult cancer units. As discussed earlier, those working with young people are reported as having unique skills specific to this population, especially with regard to communication so the practices reported may be unlike HCPs working with children and older adults. To try and determine whether there was a difference, we administered an online survey with a view to recruit 100 professionals and 38 responded. It should be noted that the low response from non-specialist units precludes any meaningful comparative analysis. However, despite these limitations, our results make an important contribution to understanding the barriers and facilitators for HCPs recommending online resources to young people with cancer.

Conclusion

We have identified transitions in the cancer timeline that can cause anxiety and uncertainty and stimulate additional online searching by young people cancer. To navigate these, young people need information specific to these transitions particularly when treatment ends. Professionals play an important role in signposting young people to those online resources where they are confident about the accuracy and delivery of information. There is a pressing need to develop online resources specific for young people on psychosocial topics beyond treatment to support young people and HCPs through this period.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank all of the professionals who participated in this study.

This paper presents independent research funded by Teenage Cancer Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of Teenage Cancer Trust. LF, JC, and SM are funded by Teenage Cancer Trust. RMT and SL are funded by the NIHR, AM is funded by Sarcoma UK. None of the funding bodies have been involved with study concept, design or decision to submit the manuscript. This manuscript has not been published or submitted elsewhere but it has been presented in part at the 3rd Global AYA Cancer Congress in Sydney Australia in December 2018. The presentation is not publicly available.

Research and practice implications

Professionals discussed different approaches and recommendations in terms of what they thought young people would want and required from online resources to help them through their cancer treatment and beyond. These key recommendations are outlined in Table 5.

Table 5.

Recommendation for guiding young people to online resources

| Theme | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Consideration of age | Variation in ways information are presented suited to changes according to development |

| Specificity | Videos of young people explaining their experiences |

| Functionality | Easy to navigate web pages Accessible to people with visual and hearing impairments Ability to be translated into multiple languages |

| Apps | Use of digital applications (apps) that can be used on mobile and tablet devices |

| Content | Use of videos, especially made by young people Information to be evidence-based Charity websites need to down play the fund raising aspect |

| User-friendly | Easy to navigate Developed with young people so visually appealing to them Information presented in “bite-size chunks” |

| Forums/chatrooms | The provision of a safe chatroom or forum to support young people treated in places where there are no other young people Forums with “question and answer” with a health care professional |

| Appealing | Use of multiple types of media is appealing to young people, such as videos, vlogs, blogs, case studies, and key facts. |

| Accessible | Resources available on a range of platforms ie app or website |

| Directory | A directory of approved and recommended websites |

| Individualized | Presenting information in a variety of formats so young people can chose the format that suits them, e.g., videos or written information. |

| Expert | Websites/Apps designed by experts in digital technology targeted at young people |

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Dieluweit U, Debatin K, Grabow D, et al. Social outcomes of long-term survivors of adolescent cancer. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1277–1284. doi: 10.1002/pon.1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wicks L, Mitchell A. The adolescent cancer experience: loss of control and benefit finding. Eur J Cancer Care. 2010;19:778–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2009.01139.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gibson F, Fern L, Whelan J, et al. A scoping exercise of favourable characteristics of professionals working in teenage and young adult cancer care: ‘thinking outside of the box’. Eur J Cancer Care. 2012;21:330–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2011.01322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taylor RM, Pearce S, Gibson F, Fern L, Whelan J. Developing a conceptual model of teenage and young adult experiences of cancer through meta-synthesis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50:832–846. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Royal College of Nursing. Competencies: Caring for Teenagers and Young Adults with Cancer: A Competence and Career Framework for Nursing. London: Teenage Cancer Trust; 2014. https://www.teenagecancertrust.org/sites/default/files/Nursing-framework.pdf. Accessed September9, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor RM, Feltbower RG, Aslam N, Raine R, Whelan JS, Gibson F. Modified international e-Delphi survey to define healthcare professional competencies for working with teenagers and young adults with cancer. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011361. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fern L, Taylor RM, Whelan J, et al. ‘The art of age appropriate care’: using participatory research to describe young people’s experience of cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2013;36:E27–E38. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318288d3ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Essig S, Steiner C, Kuehni CE, Weber H, Kiss A. Improving communication in adolescent cancer care: a multiperspective study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1423–1430. doi: 10.1002/pbc.26012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siembida EJ, Bellizzi KM. The doctor-patient relationship in the adolescent cancer setting: a developmentally focused literature review. J Adolesc Young Adul. 2015;4:108–117. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2015.0011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thompson K, Dyson G, Holland L, Joubert L. An exploratory study of oncology specialists’ understanding of the preferences of young people living with cancer. Soc Work Health Care. 2013;52:166–190. doi: 10.1080/00981389.2012.737898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsangaris E, Johnson J, Taylor R, et al. Identifying the supportive care needs of adolescent and young adult survivors of cancer: a qualitative analysis and systematic literature review. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:947–959. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2053-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ofcom. The Communications Market Report. London: Ofcom; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Office for National Statistics. Internet Access Households and Individuals. London: ONS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lea S, Martins A, Morgan S, Cargill J, Taylor R, Fern L. Online information and support needs of young people with cancer: a participatory action research study. Adolesc Health Med Ther. 2018;9:121–135. doi: 10.2147/AHMT [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emond Y, de Groot J, Wetzels W, van Osch L. Internet guidance in oncology practice: determinants of health professionals’ Internet referral behavior. Psychooncology. 2013;22:74–82. doi: 10.1002/pon.2056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Druce I, Williams C, Baggoo C, Keely E, Malcolm J. A comparison of patient and healthcare professional views when assessing quality of information on pituitary adenoma available on the internet. Endocr Pract. 2017;23:1217–1222. doi: 10.4158/EP171892.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Davies E, Yeoh K. Internet chemotherapy information: impact on patients and health professionals. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:651–657. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Antheunis ML, Tates K, Nieboer TE. Patients’ and health professionals’ use of social media in health care: motives, barriers and expectations. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;92:426–431. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rupert DJ, Moultrie RR, Read JG, et al. Perceived healthcare provider reactions to patient and caregiver use of online health communities. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2014.05.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Newnham GM, Burns WI, Snyder RD, et al. Attitudes of oncology health professionals to information from the Internet and other media. Med J Aust. 2005;183:197–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritchie J, Lewis J. Qualitative Research Practice: a Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers. London: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 22.NHS England. Five Year Forward View. London: DH; 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf. Accessed February13, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen X, Siu LL. Impact of the media and the internet on oncology: survey of cancer patients and oncologists in Canada. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4291–4297. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.23.4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haase KR, Thomas R, Gifford W, et al. Perspectives of healthcare professionals on patient Internet use during the cancer experience. Eur J Cancer Care.2019;28(1):e12953. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ngwenya N, Kenten C, Jones L, et al. Experiences and preferences for end-of-life care for young adults with cancer and their informal carers: a narrative synthesis. J Adolesc Young Adul. 2017;6:200–212. doi: 10.1089/jayao.2016.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perocchia RS, Rapkin B, Hodorowski JK, et al. Raising awareness of on-line cancer information: helping providers empower patients. J Health Commun. 2005;10:157–172. doi: 10.1080/10810730500265575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]