Abstract

We report the fabrication of polyaniline nanofiber (PANI)-modified screen-printed electrode (PANI/SPE) incorporated in a poly-dimethylsiloxane (PDMS) microfluidic channel for the detection of circulating tumor cells. We employed this device to detect melanoma skin cancer cells through specific immunogenic binding of cell surface biomarker melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R) to anti-MC1R antibody. The antibody-functionalized PANI/SPE was used in batch-continuous flow-through fashion. An aqueous cell suspension of ferri/ferrocyanide at a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min was passed over the immunosensor, which allowed for continuous electrochemical measurements. The sensor performed exceptionally well affording an ultralow limit of quantification of 1 melanoma cell/mL, both in buffer and when mixed with peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and the response was log-linear over the range of 10 to 9000 melanoma cells/10 mL.

Keywords: Melanoma cells, Electrochemical immunosensor, Microfluidics, Polyaniline nanofibers

1. Introduction

Advances in methods to identify and enumerate circulating tumor cells (CTC) and isolate and characterize tumor-derived vesicles and macromolecules in the peripheral blood of cancer patients have made ‘liquid biopsy’ a promising tool in the management of cancers including melanoma (De Souza et al., 2017; Huang and Hoon, 2016; Klinac et al., 2014; Scatena, 2015). The presence and abundance of tumor markers in the blood has been correlated with advanced cancer stage (Carrillo et al., 2006; De Giorgi et al., 2010; Freeman et al., 2012; Koyanagi et al., 2005; Mellado et al., 1996), decreased disease-free survival (Hoshimoto et al., 2012; Mellado et al., 2002, 1999) and decreased overall survival (Khoja et al., 2015, 2013; Rao et al., 2011a). The presence of CTC in the peripheral blood is now a well-accepted surrogate marker of metastatic cancer (Balch et al., 2009). Only a small number of CTC are found in the blood and thus pose a challenge for their detection and isolation (Pantel et al., 2008).

The CellSearch system is the first and only FDA-approved method currently in use for CTC detection (CELLSEARCH®CTC). This method involves immunomagnetic enrichment based on selecting cells expressing epithelial cell markers, epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM), mesenchymal stem cell protein (MSCP), melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM) followed by staining for CTC markers cytokeratin, MSCP and nuclear dye for visualization by fluorescent microscopy epithelial origin (Khoja et al., 2015; Rao et al., 2011b; Wang et al., 2016). The system has a sensitivity of 1 CTC/7.5 mL of blood. This method excludes CD45+ cells, which are of dendritic/macrophage lineage and also represent melanoma–macrophage hybrids reported to exist in the peripheral blood (Clawson et al., 2012). The lack of selectivity and time-consuming experimental protocols are some of the major drawbacks of CellSearch (Andree et al., 2016).

Isolation of melanoma CTC is technically challenging. Aya-Bonilla et al. isolated melanoma CTC using a slanted spiral microfluidic device and reported good recovery rates of spiked melanoma cells from white blood cells (Aya-Bonilla et al., 2017). Luo et al. described a microfluidic method to isolate CTC from BRAF/Pten−/− mouse melanoma model. RNA-Seq of the isolated CTC showed a signature for melanoma invasiveness (Aya-Bonilla et al., 2017). However, the relatively low purity of human CTC captured using this assay precluded the molecular analysis performed in the mouse model.

We have developed and optimized an immuno-electrochemical method to detect melanoma cells targeting melanocortin 1 receptor (MC1R), a melanocyte and melanoma-specific cell surface protein (Seenivasan et al., 2015b). Using this marker, we have achieved a detection sensitivity of 5 spiked melanoma cells per 5 mL (Prathap et al., 2018). This method has several advantages including the capacity to be multiplexed for detection of multiple cell surface markers and adaptability to be integrated into a microfluidic platform for selective isolation of CTC for investigation of heterogeneity, phenotypic and molecular characterization.

Integration of microfluidics with analytical detection methods is anticipated to enhance analytical performance, reduce the amount of test sample needed, lower the detection time, offer device portability and automation (Seenivasan et al., 2018, 2017). Many analytical procedures integrated with microfluidics for the detection and quantification of various targets have been reported (Kashefi-Kheyrabadi et al., 2018; Mitxelena-Iribarren et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2018). Miniaturized microfluidic biosensors have progressed to provide portable point-of-care diagnostics by integrating lab-on-a-chip technology and electrochemical analysis (Seenivasan et al., 2018, 2017). Electrochemical strategies have thoroughly been taken into consideration due to their very easy miniaturization of detection elements, assimilation ability and expense efficiency (Lu et al., 2016; Prathap and Gunasekaran, 2018a; Seenivasan et al., 2015a; J. Yang et al., 2016).

Herein, we report integrating a microfluidic system with an electrochemical immunosensor to detect circulating melanoma cells. Antibodies (Ab) that specifically bind to the cell surface antigen MC1R were covalently attached to polyaniline nanofibers (PANI)-modified working electrode surface on a screen-printed electrode (SPE). The results show that our sensor (MC1R-Ab-PANI/SPE) is capable of selectively detecting circulating melanoma cells with an ultralow limit of quantification (LOQ), the lowest analyte concentration necessary to produce a characteristic signal at least 10-folds higher than the background noise, of 10 cells/10 mL, and the sensor response was log-linear over a range of 10–9,000 cells/10 mL. The sensor performed equally well with melanoma cells in buffer and in the presence of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis of PANI nanofibers:

PANI nanofibers were synthesized via interfacial polymerization (Huang and Kaner, 2004) In a typical procedure, aniline (50 μL) is dissolved in 5 mL of chloroform (CHCl3) solvent as the organic phase, and 50 mmol ammonium persulphate dissolved in 2.5 mL hydrochloric acid (1 mol L−1) as the aqueous phase. These two solutions are transferred to a glass vial, creating an interface between the organic and aqueous phases, and kept at room temperature (20°C) to induce complete polymerization to occur over 20 h. Then the sample is washed repeatedly with distilled water and ethanol. When the final sample is dried at 80°C in an oven, PANI is obtained as a dark green product.

2.2. Electrode fabrication

The working electrode surface of a three-electrode SPE (3-mm diameter carbon working electrode, carbon counter electrode, and silver/silver chloride reference electrode) was modified by drop-casting 2 μL of a catalyst ink and air drying. The catalyst ink was prepared by mixing 5.0 mg of prepared PANI with 100 μL Nafion (5.0 wt%) and 0.9 mL water, then sonicating the mixture for one hour to obtain a well-dispersed suspension. For anti-MC1R Ab functionalization, the PANI/SPE was activated with 0.5 M carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) for 3 h at room temperature, which helps to increase Ab loading (Seenivasan et al., 2015; Sakamoto et al., 2017). Then, 1 μL (200 ng) aliquot of Ab (200 μg/mL) was placed over the SPE and incubated overnight at 4°C. To block nonspecific binding sites, the electrode was incubated with a solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.5%) for 15 min and washed three times with phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH=7.2) (Johansen et al., 1983).

2.3. Microfluidic device fabrication

Microfluidic device molds were fabricated via soft lithography. The masks were designed using Adobe Illustrator and printed on a transparency using a high-resolution printing service (Fineline Imaging, CO). The layers were spun with SU-8 100 (Y13273 1000L 1GL, MICRO CHEM, Newton, MA) on a silicon wafer (CC-1385, WRS, San Jose, CA). After the photoresist was soft baked on a hot plate, a ultraviolet (UV) light source was used to transfer the device pattern from the printed mask to the photoresist. A post-exposure hard-baking step was executed. This process was repeated for additional layers for the top and bottom parts of the device. Upon completing all the layers, the molds were developed for 45 min in SU-8 developer solution (PGMEA, 537543, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), washed with iso-propyl alcohol and deionized (DI) water after development. Poly-dimethylsiloxane (PDMS) (Sylgard 184 silicon elastomer base, 3097366–1004, Dow Corning, Salzburg, MI) was prepared at a ratio of 1:10 curing agent (Sylgar 184 silicone elastomer curing agent, 3097358–1004, Dow Corning, Salzburg, MI) and degassed in a vacuum for 30 min. A thick layer of PDMS (about 8 mm) was poured over the SU-8 silicon mold on a hot plate and baked at 80°C for 4 h.

The top and bottom PDMS parts were carefully removed from the molds and placed in a 70 % ethanol bath for 30 min. The bottom layer contained a cut-off that measures 15-mm × 12.7-mm × 0.55-mm (L×W×H) to perfectly fit the SPE and prevent leakage. The height of the cut-off is important because it sets the top of the SPE flat with the rest of the layer to minimize flow disruption on the 21.5-mm × 6.75-mm × 0.75-mm (L×W×H) channel in the top layer. The channel was designed to align with the detection region on the SPE. Inlet and outlet ports were created at the channel ends using a 4-mm biopsy punch (Fig. 1). Next, to permanently bond the two PDMS layers together and prevent leakage, the layers were oxygen-plasma cleaned (PE-50, Plasma Etch, Carson City, NV). To permanently combine the two PDMS layers, the parts were cleaned with oxygen plasma for 30 s and held together under a 4-kg mass for 24 h with the bottom layer cut-off facing up and the top layer channel opening facing down. Finally, the device was sterilized in a UV light chamber for 20 min.

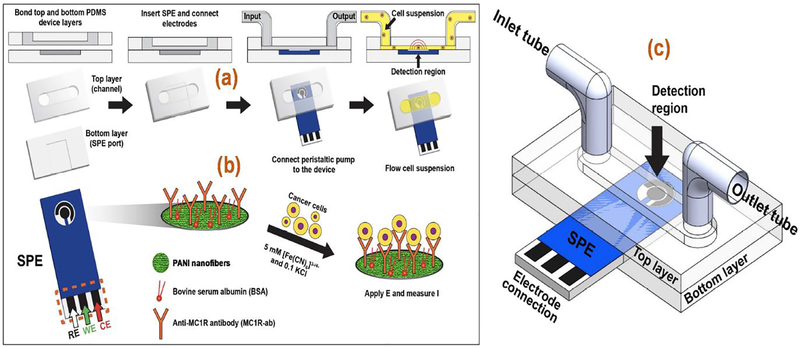

Fig. 1.

(a) Microfluidic device components and assembly sequence. (b) Scheme for MC1RAb-PANI/SPE electrochemical immunoassay for melanoma cell detection. (c) The assembled microfluidic device.

A port was located on the side of the device to insert the functionalized SPE such that the sample flow occurred over it (Fig. 1a). To prevent fluid leakage, vacuum grease was carefully applied between the chip and the PDMS layer. Electrochemical experiments were performed using CHI-660D electrochemical workstation (CHI Instruments Inc., USA). A peristaltic pump was used to flow a 10 mL cell suspension through the device channel into the inlet port of the device (Fig. 1b) and was recirculated through the cell suspension container. The assembled microfluidic setup is shown in Fig. 1c (see Fig. S1 in SI for a photograph of the entire experimental set up)

2.4. Cell lines and cell culture

Human melanoma (SK-MEL-2) and non-melanoma (human embryonic kidney HEK-293) cell lines (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were used. The cells were cultured in DMEM, 10 % FBS, 1 % penicillin-streptomycin antibiotics in a humid incubator at 37°C with 5 % CO2 and regularly tested for mycoplasma. Cells were dislodged from the culture dish using 0.25 % Trypsin–EDTA (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The number of total and viable cells were determined by using a Countess™ II Automated Cell Counter. The cell suspension was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 4 min at room temperature and the cell pellet (2.5×105 cells/mL) was suspended in sterile PBS (pH=7.2) for further analysis. PBMCs from healthy volunteers were obtained, suspended in PBS, centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 4 min, and gently washed twice with PBS. PBMCs were counted and suspended at either 2.5×105 cells/mL or 1×106 cells/mL.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Characterization of polyaniline nanofibers

The PANI nanofibers were prepared by interfacial polymerization as previously described (Prathap et al., 2018b). The X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique was used to determine the sample purity (Fig. S2a in SI). In the XRD, the appearance of the peak located at 2θ=6.4° is an indication of a greater organization of the polymer chains (Dhand et al., 2010; X. Yang et al., 2016). The XRD peaks at 19.2° and 25.5° represent periodicities parallel (100) and perpendicular (110) planes of emeraldine salt (Jin et al., 2010). Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) and high-resolution transmission electron microscope (HRTEM) micrographs (Fig. S2b in SI) show continuous interconnected nanofibers of diameter ~95 nm (Prathap et al., 2018b). XPS was performed to further probe the molecular framework. The signals from wide-scan XPS spectra of PANI (Fig. S2c in SI) at 284.9, 399.5 and 531.1 eV could be credited to C1s, N1s and O1s, respectively (Prathap et al., 2018b). A monolayer-multilayer adsorption hysteresis loop we obtained (Fig. S2d in SI) suggests Type IV isotherm and mesoporosity. The calculated specific surface area and average pore diameter determined by Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis are 160 m2. g−1 and 7.25 nm, respectively; and the calculated total pore volume is 0.22 cm3.g−1 (Prathap et al., 2018b).

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) allows characterization of electrodes for their interfacial electrical properties, i.e., charge transfer resistance (RCT) and double layer capacitance (Cdl). Hence, we subjected MC1R-Ab-PANI/SPE to EIS measurements (Fig. S3 in SI). The RCT value is a function of insulating effect at the electrode/electrolyte interface. When the bare SPE was coated with PANI, its RCT decreased substantially from 18.75 kΩ to 273 Ω owing to the ability of PANI to enhance the electron transfer (Table S1). Subsequently, when the PANI/SPE was activated with the 0.5 M carbonyldiimidazole (CDI) for 3 h, the RCT value increased to 870.1 Ω (Table S1), suggesting that CDI impedes charge transfer to some extent.

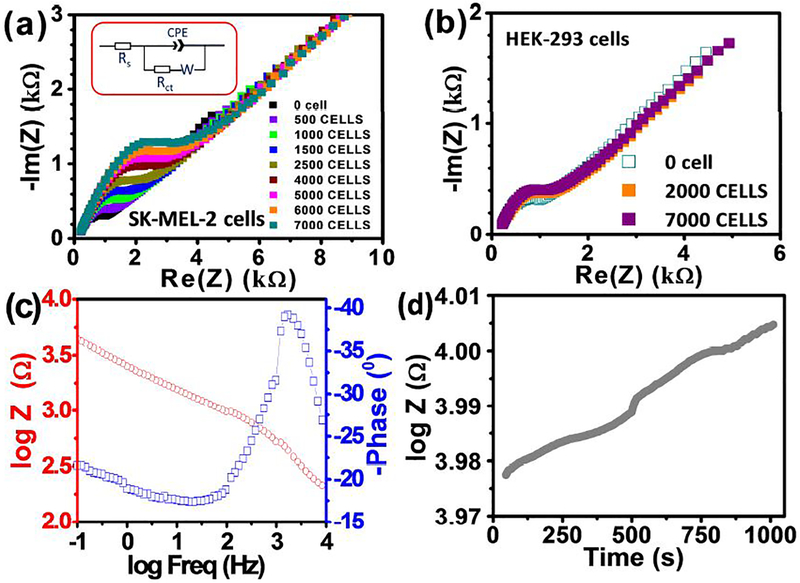

We also used EIS to test the specificity of immunobinding of the prepared electrode using SK-MEL-2 and HEK-293 cells (Fig. 2a and b). A DC bias potential of ~0.192 V in frequency (ω) range of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz and AC amplitude of 5 mV was applied. Impedance (Z) is a function of ω, which can be described as a real (ZRe) and an imaginary (−ZIm) parts per Eq. (1):

| Eq. (1) |

Fig. 2.

Nyquist plot for the MC1R-Ab-PANI/SPE electrode recorded in the frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 10 kHz at a standard potential of +0.15 V, using a sinusoidal potential perturbation of 5 mV amplitude in 0.1 M KCl solution containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−, with different concentrations of (a) SK-MEL-2 cells and (b) HEK-293 cells. (c) Bode plot for the electrode recorded in the frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 10 kHz at a standard potential of +0.154 V, using a sinusoidal potential perturbation of 5 mV amplitude in 0.1 M KCl solution containing 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4−. (d) Single frequency impedance profiling results of 1000 SK-MEL-2 cells.

The obtained spectra were fitted using Randles equivalent circuit (Fig. 2a inset). The diameter of the Nyquist plot (Fig. 2a) increased with the increasing number of SK-MEL-2 cells in the test sample due to the formation of antigen-antibody complex, which serves as a kinetic barrier for charge transfer, and hence the increase in Rct (Table S1) (Venkatanarayanan et al., 2013). Considering that Rct is the biggest variant among the circuit elements, it is taken as the appropriate sensing parameter.

A constant phase element (CPE) in the Randles circuit is to account for the topological imperfections on the electrode surface (Fig. 2a Inset). The impedance of CPE is given as:

| Eq. (2) |

Where, Yo is a proportionality constant, ω is the angular frequency, j is the imaginary number (j =√−1), and n (−1 ≤ n ≤ 1) is the exponent of ω, which controls the extent of deviation from the Randles model. For a resistor, n=0 and for a capacitor n=1; however, n=0.5 corresponds to Warburg impedance (Zw), which is associated with the domain of mass transport control arising from the diffusion of ions to and from the electrode/solution interface. As listed in Table S2, the n values for our system are close to 1. This may be explained based on increasing coverage of the electrode surface with the adhered layer of SK-MEL-2 cells that reduces its direct exposure to the electrolyte.

The obvious and continuous decrease in Yo (i.e., ZCPE, when n=1) with increasing immunoreaction (i.e., increasing cell load) indicate the corresponding decrease in the capacitive behavior with decrease in Zw (Qiu et al., 2008).

The value of n (in Eqn. 2) for our MC1R-Ab-PANI/SPE is <1 (Table S2 in SI), indicating a Cdl at electrode/electrolyte interface. The existence of CPE in electrical equivalent circuit is correlated with surface in homogeneity, roughness or fractional geometry, electrode porosity and the corresponding current/potential distributions associated with the electrode geometry (Singal et al., 2014b). The EIS spectra with high Z0 value of 21.1 μF cm−2 (Table S2) shows that the positive charges generated on the MC1R-Ab-PANI/SPE film is a dominant factor, for the quick electrode interfacial charge transfer exchange with the negatively charged probe ions (Singal et al., 2014b).

EIS measurements revealed that the sensor responds to the presence of a wide range of target SK-MEL-2 cell loads, but rather insignificantly to 2000 HEK-293 cells (Fig. 2b). To investigate the frequency-dependent impedance, Bode plot (Fig. 2c) with the logarithm of absolute impedance |Z| and phase angle, was plotted against the logarithm of excitation frequency. Maximum changes in impedance was recorded in the low frequency region 25.6 Hz (Fig. 2c). Electrochemical single frequency impedance (SFI) profiling was done with 1000 SK-MEL-2 cells to verify the specificity of the antibody-antigen interaction (Karimullah et al., 2013). The working frequency was selected by consulting the Bode plot, as it consists of vital frequency information (Fig. 2d). For SFI experiments, the potentiostat was fixed at a frequency of 25.6 Hz. The SFI information helps explain the variation of frequency-dependent impedance (Z) and phase angle (Φ) represented by the formula Z’=ZeIφ (Fig. 2d) (Aydın et al., 2017). The binding between the antibody and the melanoma cells triggers a change in impedance of the circuit. Significant changes in impedance (ΔZ = 608 Ω in 1000 s) were due to the binding of the SK-MEL-2 cells to the anti-MC1R Ab (Fig. 2d) (Shen et al., 2007).

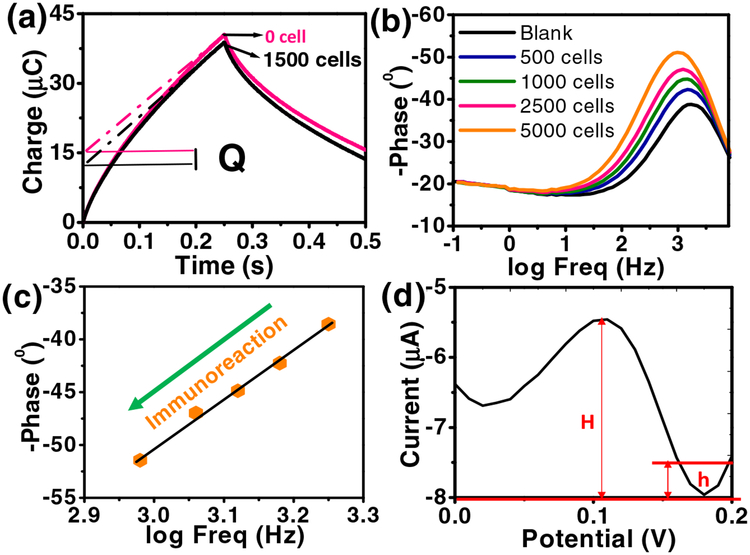

Fig. 3a shows typical chronocoulometric curves in the absence and presence of 1500 SK-MEL-2 cells and a corresponding increment of the redox charge (ΔQ). The linear part of the plot was extrapolated back to time zero to obtain the intercept value of the charge (Q), which shows highly sensitive binding affinity towards the target SK-MEL-2 cells. The Nyquist plot of the sensor after circulating samples with different SK-MEL-2 cell loads is shown in Fig. 3b,c. The impedance depends on the frequency of the potential perturbation. At higher frequencies Zw is small since diffusing reactants do not have to move very far; while at low frequencies Zw increases since the reactants must diffuse farther. The phase angle approaches a lower frequency on increasing the immunoreaction with SK-MEL-2 cells, exposing an excellent biocompatibility of the electrode (Fig. 3b,c) (Aydın et al., 2017). Further, Fig. 3c shows a linear relationship between the changes in phase angle and logarithmic value of frequency with increase in the number of SK-MEL-2 cells (from 0 to 5000 cells). The maximum shift in phase angle (−51.1° to −38.8°) occurs when the antigen binds to the specific sites on the antibody (Singal et al., 2014a). Fig. 3c shows a major decrease in lowest phase angle with relative to increasing SK-MEL-2 cells concentration on immunoreaction revealing an increasing RCT. This increase in RCT due to immunoreaction with the lowest phase angle moving towards the lower frequency shows a good biocompatibility of our electrode.

Fig. 3.

(a) Plot of charge (Q) versus time curves in the absence and presence of 1500 SK-MEL-2 cells in 5 mM [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− and 0.1 M KCl solution (10 mL). The dotted lines represent linear fit to determine the intercept at t = 0. ΔQ is the charge difference in the absence and presence of 1500 SK-MEL-2 cells. (b) Bode plot and (c) plot of logarithm frequency vs. phase angle. (d) DPV curve for SK-MEL-2 cells (10 cells/10 mL) at MC1R-Ab-PANI/SPE.

Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) data were obtained, using a sample with 10 SK-MEL-2 cells. The data from three successive measurements were used to determine the LOQ as 1 cell/mL (Fig. 3d) (Armbruster and Pry, 2008).

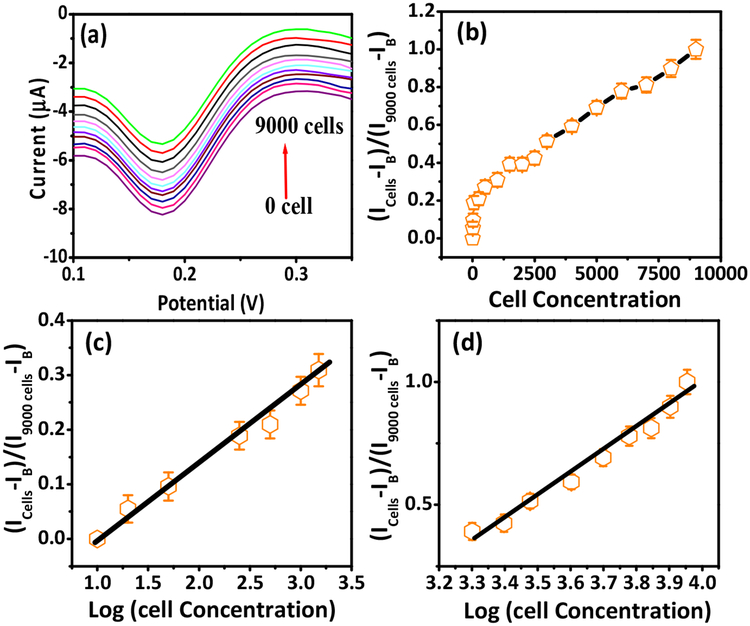

The peak currents from DPV scans obtained over 0 to 9000 cells/1o mL (Fig. 4a) were used to calculate the cathodic ratio of signal intensity as (Icells-IB)/(I9000 cells-IB) in the presence and absence of SK-MEL-2 cells (Fig. 4b), where IB and Icells were the DPV peak currents in the absence and presence of SK-MEL-2 cells and I9000 cells is the maximum peak current after the sensor was saturated by 9000 cells/10 mL. This non-linear plot is represented as two log-linear relationships over the cell loads of 10–1000 cells/10 mL (Fig. 4c) and 2000–9000 cells/10 mL (Fig. 4d). The appearance of the two linear ranges suggests an adsorption process. For lower concentrations, the adsorption process does not alter the kinetics of the electrode surface; whereas, for higher concentrations, the peak current intensity decreased due to saturation of the electrode surface by the electroactive species. Moreover, it should be noticed that the peak potentials recorded in lower concentrations shifted towards less negative potential compared to higher concentrations (Bard and Faulkner, 2001; Brycht et al., 2017). Data obtained without flow were also similarly linear (Fig. S4 in SI). The detection sensitivity and LOQ of our immunosensor is much better than those formerly reported (Table S3 in SI). The improved sensitivity we obtained is attributed to the small geometry of microfluidics device and large surface-to-volume ratio of mesoporous PANI.

Fig. 4.

(a) DPV curves with different SK-MEL-2 cell loads from 0 to 9000 cells/10 mL at MC1R-Ab-PANI/SPE (200 ng Ab loading). (b) Peak current ratio versus SK-MEL-2 cell concentration. Calibration curves of peak current ratio vs logarithm of SK-MEL-2 cell load: (c) 10 to 1000/10 mL and (d) 2000 to 9000/10 mL.

The repeatability of the immunosensor, tested using 14 electrodes prepared in the same conditions with 10 cells/10 mL, did not exceed 6.9%. The reproducibility was investigated by fabricating different electrodes (for calibration five electrodes were used) to detect SK-MEL-2 cells independently. All sensor responses were similar, and the relative standard deviation (RSD) obtained was 6.5%. These results indicate that our sensor has an acceptable fabrication reproducibility.

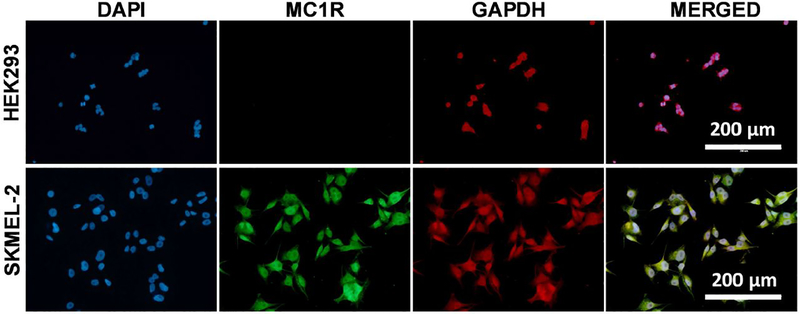

Additionally, we evaluated the physical binding specificity of the fabricated electrodes to SK-MEL-2 and HEK-293 cells. We first verified the expression of MC1R in SK-MEL-2 and HEK-293 cells and used glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), a housekeeping protein, as control (Fig. 5). As expected, HEK-293 cells expressed GAPDH but not MC1R (Fig. 5, top), while SK-MEL-2 cells expressed both (Fig. 5, bottom).

Fig. 5.

Immunofluorescence staining of HEK293 and SK-MEL-2 cells with MC1R and GAPDH. (Top) HEK-293 cells show DAPI staining and GAPDH expression but do not exhibit MC1R expression. (Bottom) SK-MEL-2 cells show DAPI staining and expression of both MC1R and GAPDH.

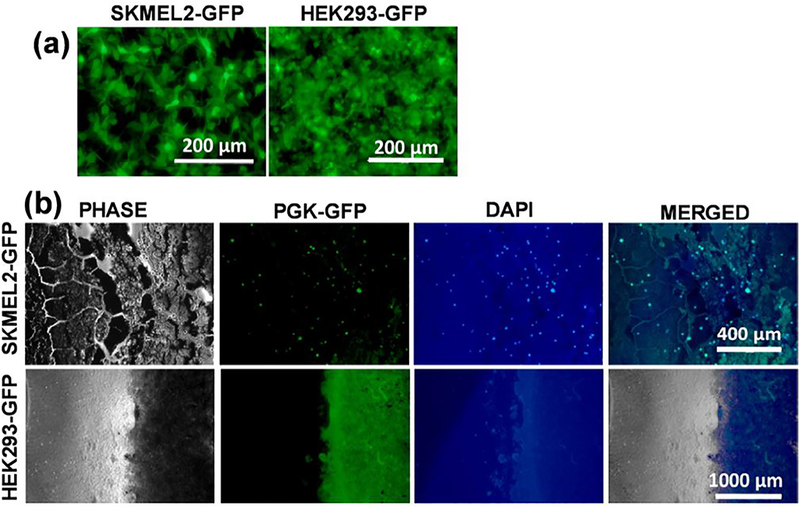

Next, we performed an electrode-binding assay with green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged cells. SK-MEL-2 and HEK-293 cells were tagged by transducing with a GFP reporter lentivirus (Fig. 6a). They were incubated with the electrode for 1 h, washed three times, fixed and then ProLong Gold Antifade with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) was added. Electrodes with GFP-tagged cells and stained with DAPI were visualized using fluorescent microscopy. Results showed that SK-MEL-2 but not HEK-293 cells bind to the electrode (Fig. 6b). Taken together, these data demonstrate that the fabricated electrodes are highly specific in binding SK-MEL-2 melanoma cells.

Fig. 6.

Electrode binding assay with GFP-Tagged Cells. (a) SK-MEL-2 (left) and HEK293 (right) cells expressing PGK-GFP reporter. (b) Binding assay of SKMEL2-GFP tagged cells on PANI-MC1R electrode (Top). Binding assay of HEK-293-GFP tagged cells on PANI-MC1R electrode (Bottom).

To further expand the electrode functional characterization, we applied electrochemical method for the quantitative detection of SK-MEL-2 cells with human PBMCs, the context in which CTC need to be detected. The experiment was performed with monoclonal anti-MC1R antibodies as described previously using different concentrations of SK-MEL-2 cells. The DPV results show (Fig. S5a in SI), the surface of the cell captured by the sensor is smooth and clean. The key obstacle for electrochemical biosensors operating in complex samples such as blood is fouling of electrode via deposition of proteins or cells. As seen from Fig. S5a in SI, while reduction peak did not shift toward a more negative potential (versus Ag/AgCl), the amplitude of peak showed a decrease in current for PBMC addition, and was able to detect 1000 SK-MEL-2 cells (Fig. S5b,c in SI). The intricacy of PBMC as well as the ensuing nonspecific bindings resulted in a greater background signal than what was observed when detecting SK-MEL-2 cells in buffer. While the factors for decreased dynamic range in blood samples need to be examined, it is feasible that fewer binding sites are available in complex media such as with PBMC. Overall, despite the changes in electrochemical properties and dynamic range, we conclude that electrodes fabricated are functional and sensitive in PBMCs samples. The electrochemical signal was relatively stable with signal suppression not exceeding 20% in a three-hour experiment.

4. Conclusions

An electrochemical immunosensor was developed for specific detection of circulating melanoma cancer cells in a flow-through microfluidic device platform. The PANI-modified SPE sensor was highly sensitivity with an ultralow LOQ of 10 cells/10 mL with excellent repeatability, and wide log-linear range from 10 cells to 9000 cells/10 mL. These performance characteristics, both in buffer and with PBMC, make our microfluidic sensing platform an excellent candidate device with potential for early diagnosis of cancer.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

A microfluidics-based immunoelectrochemical sensor was developed

An ultralow limit of quantification of 1 cell/mL was achieved

The sensor performance was verified via cell culture experiments

The sensor response is stable, repeatable, and linear over a wide range

This system is potentially useful for rapid detection of circulating tumor cells

Acknowledgements

Financial support received partly by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number P30 AR066524, Skin Diseases Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Wisconsin Carbone Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA014520 is gratefully acknowledged. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not always represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Bard Allen J. and Faulkner Larry R., Electrochemical Methods: Fundamentals and Applications, New York: Wiley, 2001, 2nd ed., 2002. Russian Journal of Electrochemistry 38, 1364–1365. 10.1023/A:1021637209564 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andree KC, van Dalum G, Terstappen LWMM, 2016. Challenges in circulating tumor cell detection by the CellSearch system. Mol Oncol 10, 395–407. 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armbruster DA, Pry T, 2008. Limit of Blank, Limit of Detection and Limit of Quantitation. Clin Biochem Rev 29, S49–S52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aya-Bonilla CA, Marsavela G, Freeman JB, Lomma C, Frank MH, Khattak MA, Meniawy TM, Millward M, Warkiani ME, Gray ES, Ziman M, 2017. Isolation and detection of circulating tumour cells from metastatic melanoma patients using a slanted spiral microfluidic device. Oncotarget 8, 67355–67368. 10.18632/oncotarget.18641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydın EB, Aydın M, Sezgintürk MK, 2017. A highly sensitive immunosensor based on ITO thin films covered by a new semi-conductive conjugated polymer for the determination of TNFα in human saliva and serum samples. Biosens Bioelectron 97, 169–176. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.05.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydın EB, Sezgintürk MK, 2017. A sensitive and disposable electrochemical immunosensor for detection of SOX2, a biomarker of cancer. Talanta 172, 162–170. 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.05.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong S-J, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, Buzaid AC, Cochran AJ, Coit DG, Ding S, Eggermont AM, Flaherty KT, Gimotty PA, Kirkwood JM, McMasters KM, Mihm MC, Morton DL, Ross MI, Sober AJ, Sondak VK, 2009. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J. Clin. Oncol 27, 6199–6206. 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard AJ, Faulkner LR 2001. Electrochemical Methods: Fundamental and Applications Wiley & Sons, New York, NY [Google Scholar]

- Brycht M, Nosal-Wiercińska A, Sipa K, Rudnicki K, Skrzypek S, 2017. Electrochemical determination of closantel in the commercial formulation by square-wave adsorptive stripping voltammetry. Monatsh Chem 148, 463–472. 10.1007/s00706-016-1862-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo E, Prados J, Marchal JA, Boulaiz H, Martínez A, Rodríguez-Serrano F, Caba O, Serrano S, Aránega A, 2006. Prognostic value of RT-PCR tyrosinase detection in peripheral blood of melanoma patients. Dis. Markers 22, 175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clawson GA, Kimchi E, Patrick SD, Xin P, Harouaka R, Zheng S, Berg A, Schell T, Staveley-O’Carroll KF, Neves RI, Mosca PJ, Thiboutot D, 2012. Circulating Tumor Cells in Melanoma Patients. PLOS ONE 7, e41052 10.1371/journal.pone.0041052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Giorgi V, Pinzani P, Salvianti F, Panelos J, Paglierani M, Janowska A, Grazzini M, Wechsler J, Orlando C, Santucci M, Lotti T, Pazzagli M, Massi D, 2010. Application of a Filtrationand Isolation-by-Size Technique for the Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Cutaneous Melanoma. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 130, 2440–2447. 10.1038/jid.2010.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Souza LM, Robertson BM, Robertson GP, 2017. Future of circulating tumor cells in the melanoma clinical and research laboratory settings. Cancer Lett 392, 60–70. 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhand C, Das M, Sumana G, Kumar Srivastava A, Kumar Pandey M, Gi Kim C, Datta M, Dhar Malhotra B, 2010. Preparation, characterization and application of polyaniline nanospheres to biosensing. Nanoscale 2, 747–754. 10.1039/B9NR00346K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JB, Gray ES, Millward M, Pearce R, Ziman M, 2012. Evaluation of a multi-marker immunomagnetic enrichment assay for the quantification of circulating melanoma cells. Journal of Translational Medicine 10, 192 10.1186/1479-5876-10-192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshimoto S, Shingai T, Morton DL, Kuo C, Faries MB, Chong K, Elashoff D, Wang H-J, Elashoff RM, Hoon DSB, 2012. Association between circulating tumor cells and prognosis in patients with stage III melanoma with sentinel lymph node metastasis in a phase III international multicenter trial. J. Clin. Oncol 30, 3819–3826. 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.0887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Kaner RB, 2004. Nanofiber Formation in the Chemical Polymerization of Aniline: A Mechanistic Study. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 43, 5817–5821. 10.1002/anie.200460616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SK, Hoon DSB, 2016. Liquid biopsy utility for the surveillance of cutaneous malignant melanoma patients. Mol Oncol 10, 450–463. 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Nagaiah TC, Xia W, Spliethoff B, Wang S, Bron M, Schuhmann W, Muhler M, 2010. Metal-free and electrocatalytically active nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes synthesized by coating with polyaniline. Nanoscale 2, 981–987. 10.1039/B9NR00405J [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen L, Nustad K, Ørstavik TB, Ugelstad J, Berge A, Ellingsen T, 1983. Excess antibody immunoassay for rat glandular kallikrein. Monosized polymer particles as the preferred solid phase material. Journal of Immunological Methods 59, 255–264. 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90038-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimullah AS, Cumming DRS, Riehle M, Gadegaard N, 2013. Development of a conducting polymer cell impedance sensor. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 176, 667–674. 10.1016/j.snb.2012.09.075 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kashefi-Kheyrabadi L, Kim J, Gwak H, Hyun K-A, Bae NH, Lee SJ, Jung H-I, 2018. A microfluidic electrochemical aptasensor for enrichment and detection of bisphenol A. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 117, 457–463. 10.1016/j.bios.2018.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoja L, Lorigan P, Dive C, Keilholz U, Fusi A, 2015. Circulating tumour cells as tumour biomarkers in melanoma: detection methods and clinical relevance. Ann. Oncol 26, 33–39. 10.1093/annonc/mdu207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoja L, Lorigan P, Zhou C, Lancashire M, Booth J, Cummings J, Califano R, Clack G, Hughes A, Dive C, 2013. Biomarker utility of circulating tumor cells in metastatic cutaneous melanoma. J. Invest. Dermatol 133, 1582–1590. 10.1038/jid.2012.468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinac D, Gray ES, Freeman JB, Reid A, Bowyer S, Millward M, Ziman M, 2014. Monitoring changes in circulating tumour cells as a prognostic indicator of overall survival and treatment response in patients with metastatic melanoma. BMC Cancer 14, 423 10.1186/1471-2407-14-423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyanagi K, Kuo C, Nakagawa T, Mori T, Ueno H, Lorico AR, Wang H-J, Hseuh E, O’Day SJ, Hoon DSB, 2005. Multimarker Quantitative Real-Time PCR Detection of Circulating Melanoma Cells in Peripheral Blood: Relation to Disease Stage in Melanoma Patients. Clinical Chemistry 51, 981–988. 10.1373/clinchem.2004.045096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Seenivasan R, Wang Y-C, Yu J-H, Gunasekaran S, 2016. An Electrochemical Immunosensor for Rapid and Sensitive Detection of Mycotoxins Fumonisin B1 and Deoxynivalenol. Electrochimica Acta 213, 89–97. 10.1016/j.electacta.2016.07.096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mellado B, Colomer D, Castel T, Muñoz M, Carballo E, Galán M, Mascaró JM, Vives-Corrons JL, Grau JJ, Estapé J, 1996. Detection of circulating neoplastic cells by reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction in malignant melanoma: association with clinical stage and prognosis. J. Clin. Oncol 14, 2091–2097. 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.7.2091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellado B, Del Carmen Vela M, Colomer D, Gutierrez L, Castel T, Quintó L, Fontanillas M, Reguart N, Domingo-Domènech JM, Montagut C, Estapé J, Gascón P, 2002. Tyrosinase mRNA in blood of patients with melanoma treated with adjuvant interferon. J. Clin. Oncol 20, 4032–4039. 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mellado B, Gutierrez L, Castel T, Colomer D, Fontanillas M, Castro J, Estapé J, 1999. Prognostic significance of the detection of circulating malignant cells by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction in long-term clinically disease-free melanoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res 5, 1843–1848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitxelena-Iribarren O, Zabalo J, Arana S, Mujika M, 2019. Improved microfluidic platform for simultaneous multiple drug screening towards personalized treatment. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 123, 237–243. 10.1016/j.bios.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantel K, Brakenhoff RH, Brandt B, 2008. Detection, clinical relevance and specific biological properties of disseminating tumour cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 329–340. 10.1038/nrc2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prathap MUA, Gunasekaran S, 2018a. Rapid and Scalable Synthesis of Zeolitic Imidazole Framework (ZIF-8) and its Use for the Detection of Trace Levels of Nitroaromatic Explosives. Advanced Sustainable Systems 2 10.1002/adsu.201800053 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prathap MUA, Rodríguez CI, Sadak O, Guan J, Setaluri V, Gunasekaran S, 2018b. Ultrasensitive electrochemical immunoassay for melanoma cells using mesoporous polyaniline. Chem. Commun 54, 710–714. 10.1039/C7CC09248B [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiu Y, Liao R, Zhang X, 2008. Real-Time Monitoring Primary Cardiomyocyte Adhesion Based on Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy and Electrical Cell−Substrate Impedance Sensing. Anal. Chem 80, 990–996. 10.1021/ac701745c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C, Bui T, Connelly M, Doyle G, Karydis I, Middleton MR, Clack G, Malone M, Coumans F. a. W., Terstappen LWMM, 2011a. Circulating melanoma cells and survival in metastatic melanoma. Int. J. Oncol 38, 755–760. 10.3892/ijo.2011.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao C, Bui T, Connelly M, Doyle G, Karydis I, Middleton MR, Clack G, Malone M, Coumans F. a. W., Terstappen LWMM, 2011b. Circulating melanoma cells and survival in metastatic melanoma. Int. J. Oncol 38, 755–760. 10.3892/ijo.2011.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto S, Nagamitsu R, Yusakul G, Miyamoto T, Tanaka H, Morimoto S, 2017. Ultrasensitive immunoassay for monocrotaline using monoclonal antibody produced by N, N’-carbonyldiimidazole mediated hapten-carrier protein conjugates. Talanta 168, 67–72. 10.1016/j.talanta.2017.03.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatena R (Ed.), 2015. Advances in Cancer Biomarkers: From biochemistry to clinic for a critical revision, Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology Springer; Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Seenivasan R, Chang W-J, Gunasekaran S, 2015a. Highly Sensitive Detection and Removal of Lead Ions in Water Using Cysteine-Functionalized Graphene Oxide/Polypyrrole Nanocomposite Film Electrode. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 15935–15943. 10.1021/acsami.5b03904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seenivasan R, Maddodi N, Setaluri V, Gunasekaran S, 2015b. An electrochemical immunosensing method for detecting melanoma cells. Biosens Bioelectron 68, 508–515. 10.1016/j.bios.2015.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seenivasan R, Singh CK, Warrick JW, Ahmad N, Gunasekaran S, 2017. Microfluidic-integrated patterned ITO immunosensor for rapid detection of prostate-specific membrane antigen biomarker in prostate cancer. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 95, 160–167. 10.1016/j.bios.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seenivasan R, Warrick JW, Rodriguez CI, Mattison W, Beebe DJ, Setaluri V, Gunasekaran S, 2018. Integrating electrochemical immunosensing and cell adhesion technologies for cancer cell detection and enumeration. Electrochimica Acta 286, 205–211. 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L, Chen Z, Li Y, Jing P, Xie S, He S, He P, Shao Y, 2007. A chronocoulometric aptamer sensor for adenosine monophosphate. Chem. Commun 0, 2169–2171. 10.1039/B618909A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava A, Gupta VB, 2011. Methods for the determination of limit of detection and limit of quantitation of the analytical methods. Chronicles of Young Scientists 2, 21 10.4103/2229-5186.79345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singal S, Biradar AM, Mulchandani A, Rajesh, 2014a. Ultrasensitive Electrochemical Immunosensor Based on Pt Nanoparticle–Graphene Composite. Appl Biochem Biotechnol 174, 971–983. 10.1007/s12010-014-0933-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singal S, Srivastava AK, Biradar AM, Mulchandani A, Rajesh, 2014b. Pt nanoparticles-chemical vapor deposited graphene composite based immunosensor for the detection of human cardiac troponin I. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 205, 363–370. 10.1016/j.snb.2014.08.088 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatanarayanan A, Keyes TE, Forster RJ, 2013. Label-Free Impedance Detection of Cancer Cells. Anal. Chem 85, 2216–2222. 10.1021/ac302943q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Balasubramanian P, Chen AP, Kummar S, Evrard YA, Kinders RJ, 2016. Promise and limits of the CellSearch platform for evaluating pharmacodynamics in circulating tumor cells. Semin. Oncol 43, 464–475. 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Huang X, Guo J, Ma X, 2018. Automatic smartphone-based microfluidic biosensor system at the point of care. Biosensors and Bioelectronics 110, 78–88. 10.1016/j.bios.2018.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Kwak TJ, Zhang X, McClain R, Chang W-J, Gunasekaran S, 2016. Digital pH Test Strips for In-Field pH Monitoring Using Iridium Oxide-Reduced Graphene Oxide Hybrid Thin Films. ACS Sens 1, 1235–1243. 10.1021/acssensors.6b00385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Liu Y, Lei H, Li B, 2016. An organic–inorganic broadband photodetector based on a single polyaniline nanowire doped with quantum dots. Nanoscale 8, 15529–15537. 10.1039/C6NR04030F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.