Abstract

Objective. To assess the effectiveness of a required reflective writing assignment to document students’ exposure to and experience with interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) during introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs).

Methods. Pharmacy students completed the assignment during their community or institutional pharmacy IPPE and electronically submitted their written reflections. Twelve codes were created to indicate opportunities, barriers, and patient-centered care identified in the community pharmacy reflections. Fourteen codes were created to indicate interprofessional communication, roles, patient-centered care, and teamwork identified in the institutional pharmacy reflections. The reflections were then qualitatively analyzed to identify and code themes related to IPCP.

Results. Two hundred twenty-eight reflections were submitted. Exposure to an observed IPCP was described in 51% of the community pharmacy reflections and in 100% of the institutional pharmacy reflections. Identified opportunities to improve IPCP in community pharmacy were extended pharmacy services, expanded networking and relationships, making more phone calls to other health professionals, and greater use of technology. The identified barriers to IPCP in community pharmacy were difficulty accessing patient health data, lack of direct access to prescribers, hierarchy, pharmacy workload, and lack of timely communication. The identified themes that impacted IPCP in institutional settings included dysfunctional communication, technology use, mutual respect, role overlap, teamwork, nonphysician leadership, and personal relationships.

Conclusion. Implementing a reflective assignment during IPPEs was an effective way to document student exposure to and experience in IPCP in two types of pharmacy practice settings and helped to meet pharmacy accreditation standards of having IPE included in early experiential education settings.

Keywords: Interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP), introductory pharmacy practice experience (IPPE), community, institutional, experiential education

INTRODUCTION

Interprofessional education (IPE) and interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP) occur when two or more students from different professions learn about, from, and with each other to enable collaboration and improve health outcomes.1 The Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) outcomes and the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE) standards have incorporated IPE into their guiding documents for Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) degree programs.2,3 The ACPE Standard 11 encourages curricular introduction, reinforcement, and practice during introductory and advanced experiential education rotations with interprofessional teams to understand team dynamics and achieve the CAPE outcome of interprofessional collaborator.2,3 In addition, the Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) developed core competencies for students in all health professions’ education to aid in breaking down the silos that exist in our current training models.4 The increased focus on realigning IPE with clinical practice redesign5 will help bridge the gap that can exist between education and practice and ultimately achieve the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Triple Aim, which is improved patient experience of care, improved population outcomes, and reduced cost.5,6

To date, educational literature promoting IPE has focused on classroom and simulation-based activities in pre-clinical training.7-9 However, since the release of the 2011 IPEC Core Competencies, there has been a shift to intentionally position IPE within the “clinical training” years of health professions’ education. Students should be exposed to IPCP in early clinical experiences to see interprofessional communication and teamwork modeled, and as they advance in their practice experiences, they should be given opportunities to practice and demonstrate those skills. Additionally, they need to be able to recognize the opportunities and barriers to IPCP that they will encounter as they enter their pharmacy career. To achieve this early exposure to IPCP in the pharmacy curriculum, students should be provided with intentional opportunities for practice-based IPE during their introductory pharmacy practice experiences (IPPEs).3 We define exposure in this context as both the passive observation of IPCP and experience in being an active participant in IPCP. The ACPE Standard 12 requires that IPPEs expose students to exemplary contemporary US practice models, including IPCP, with a balance of time in community and health system settings.3 To our knowledge, limited literature exists regarding the incorporation of IPE into IPPEs,10 and no literature exists regarding the evaluation of pharmacy students’ exposure to or experience with IPCP during IPPEs.

Pharmacy settings differ significantly in terms of structure, location, and patient population, and are not equivalent in terms of the IPCP learning opportunities they provide when facilitating IPPEs or APPEs. Thus, the educational approaches used in each setting must be customized to bridge these differences. One tool to use to facilitate this complex task is student reflections. Reflective writing about practice experiences is valued across health professions education as these skills can be used to develop lifelong-learning strategies.11 With respect to pharmacy, reflection improves students’ critical-thinking skills and reflective writing allows students to document achievement of multiple ability-based outcomes.12,13 The ACPE Standard 4 encourages students to examine, reflect, and self-assess their knowledge, skills, attitudes, and values for personal and professional growth in order to develop personal learning plans and maintenance of student portfolios.3 With this framework established, a reflective assignment was developed for the IPPE coursework in the pharmacy school curriculum. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate pharmacy students’ exposure to IPCP and experience of IPCP during community and institutional IPPEs using a reflective assignment.

METHODS

The University of Kansas (KU) offers a four-year PharmD degree to approximately 140 to 160 students per class. The students are divided between two campuses, with the majority of students (120 to 140) located on the main campus in Lawrence and the remaining students (20) located on the Wichita campus. The university has the only school of pharmacy in the state of Kansas. Both campuses provide opportunities for students to collaborate with students from multiple health care professions in a variety of pharmacy practice settings across the state.

Students within the KU School of Pharmacy are systematically introduced to the concepts of interprofessional collaboration through the required Foundations in Interprofessional Collaboration (FIPC) course, which is grounded in the TeamSTEPPS framework developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. During the first semester, students are introduced to the benefits of IPE and IPCP for patient care in a one-hour seminar. During semesters two, three, and five, students participate in an interprofessional, campus-wide, half-day event that exposes students to hands on activities to expand their understanding of the TeamSTEPPS domains: team structure, communication, leadership, situation monitoring, and mutual support. Further details of this coursework have been previously reported in the literature.14

All pharmacy students at KU are required to complete a one-month IPPE during the summer or winter break following their first and second years. First-year students complete their IPPE in a community setting (typically chain or independent pharmacies), while second-year students complete their IPPE in an institutional setting (typically hospitals or long-term care facilities). During their IPPEs, students are immersed in the practice setting for 160 hours (typically 40 hours per week for four weeks) and are required to complete various assignments in a workbook in order to facilitate their exploration of the key concepts they need to learn in each pharmacy practice setting. Some examples of assignments in the community IPPE workbook include reviewing commonly dispensed drugs, conducting a medication history, and providing patient or staff education. For the institutional IPPE workbook, projects include interpreting inpatient orders, reviewing laboratory tests and medical abbreviations, and providing a presentation to a target audience.

For the 2016-2017 academic year, the experiential education office (EEO) added a reflective assignment to each IPPE workbook that required students to write a brief summary (approximately 500 words) of their exposure to and experience in IPCP with prescribers and/or non-prescribers during their IPPE. Specifically, the reflective assignment for the community pharmacy IPPE encouraged students to meet with their preceptor and discuss interprofessional collaboration and teamwork. Examples of specific questions were provided to the students to facilitate the conversation (Appendix 1). Upon completion of the IPPE, students electronically submitted the written reflection about their exposure to IPCP and the opportunities and barriers that impact community pharmacy collaboration with interprofessional teams. The reflective assignment for the institutional pharmacy IPPE provided more guidance to students as there were more perceived opportunities for IPCP in the institutional settings. Students were given an interprofessional “scavenger hunt” list from which they were required to choose and complete two experiences, but encouraged to complete more. The scavenger hunt was intended to shape the student’s IPE experience (Appendix 2). Upon completion of the IPPE, students electronically submitted a written reflection on their exposure to and experiences with IPCP. They were instructed to reflect on areas from the IPEC competencies, such as roles and responsibilities of team members, communication, and/or teamwork. The interprofessional reflective writing assignments were developed to serve a dual purpose. First, the assignment allowed experiential education faculty members to gauge students’ exposure to IPCP and learn about the current state of intentional IPE at the rotation sites used by KU. Second, the assignment was a practical curricular method of creating greater awareness of IPCP and building capacity for interprofessional experiences on IPPEs to meet accreditation standards. The student learning objectives for the community pharmacy IPPE reflective assignment were to recognize actual or potential IPCP, reflect on potential opportunities and/or barriers to IPCP, and identify potential solutions for enhancing IPCP in the respective practice setting. The objectives for the institutional pharmacy IPPE assignment were to recognize actual or potential IPCP and reflect on their experience with IPCP, including how roles and responsibilities of team members, communication, and teamwork influenced patient care. As students would be progressing from the community IPPE to the institutional IPPE, the assignments were intentionally developed to build upon the IPCP concepts introduced during the FIPC coursework and to further develop the student’s ability to recognize collaboration in practice.

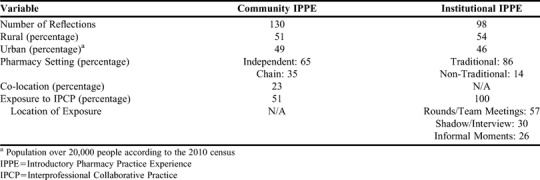

The reflections were electronically submitted to the EEO for review at a global level to assess whether the student would receive credit for the submission. The reflections were provided to the investigation team and de-identified by one investigator. Prior to reviewing, the investigators identified general site descriptors to apply to the reflections. Descriptors were developed in order to group the reflections into similar practice site categories. The first descriptor, which applied to both community and institutional reflections, focused on population size of the city where the practice site was located. Site locations were categorized as urban if the population was equal to or greater than 20,000 people, or rural if the population was less than 20,000 people according to the 2010 US Census of Kansas. For community IPPE reflections, additional descriptors identified the site as an independent or a chain community pharmacy. The chain pharmacy descriptor included both the traditionally identified national/regional chain pharmacies (eg, CVS, Walgreens, Walmart) and national/regional grocery store pharmacies (eg, HyVee, Cosentino’s, Dillons). Additionally, if a community pharmacy was located within the same building as another clinical service, typically a physician’s office, it was identified with a “co-location” descriptor. If students explicitly reported on a personal IPCP encounter, it was identified with a “real exposure” descriptor. Institutional IPPE reflections included additional descriptors of “traditional hospital setting” or “nontraditional hospital setting” (eg long-term care facility, skilled-nursing facility, rehabilitation facility, surgical center), as well as “type of IPCP” the student encountered (eg, rounds/team meeting, shadowing/interview, informal moments). All descriptors are summarized in Table 1. All de-identified reflections were uploaded to Dedoose software (SocioCultural Research Consultants, Manhattan Beach, CA) and descriptors were applied by student investigators.

Table 1.

Site Demographics for Community and Institutional Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences and Pharmacy Students’ Reported Exposure to Interprofessional Collaboration

Data were analyzed using a conventional content analysis approach. The coding system was created by two faculty members with IPE expertise. A sample of the data was used during the open-coding phase, and codes were created using inductive and deductive content analysis. Codes were refined and the coding system was finalized before full content analysis occurred. The senior investigator trained two student investigators in how to use the system. One student investigator analyzed the community pharmacy IPPE data, and the other analyzed the institutional pharmacy IPPE data. Inter-rater agreement was reached between the student investigators and senior investigator as a pooled Cohen kappa value of 0.65 was achieved. The two student investigators then applied the coding system to all data.

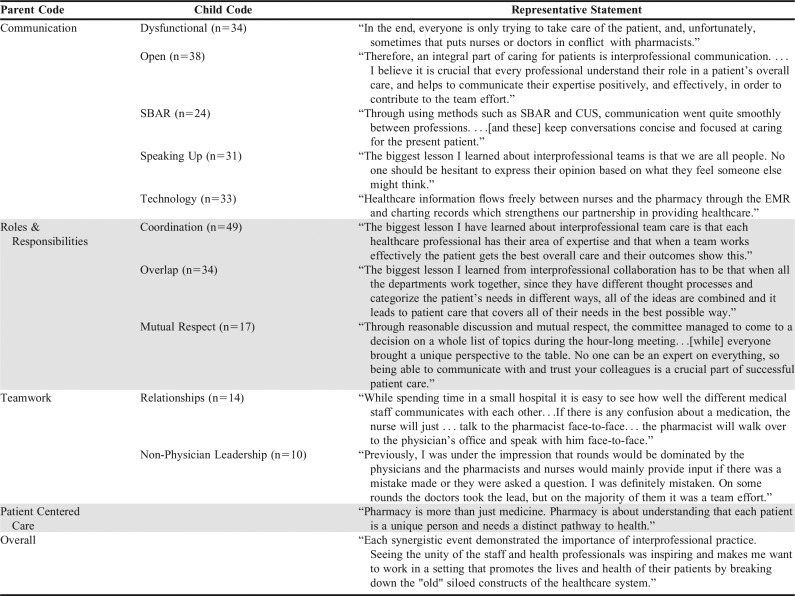

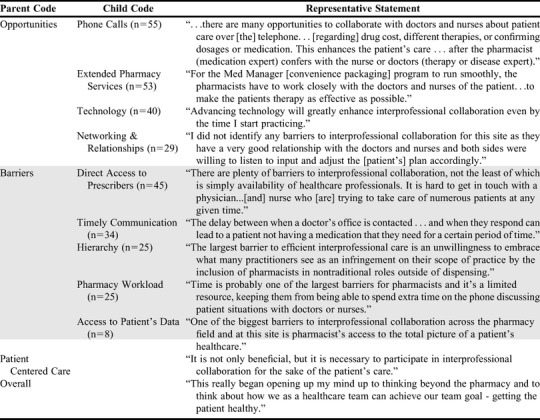

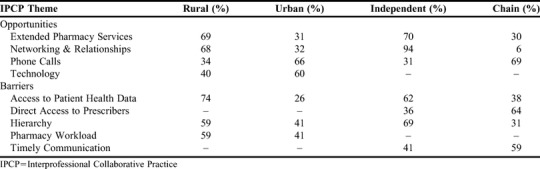

For the community pharmacy IPPE data, three parent codes were identified: patient-centered care, opportunities for IPCP, and barriers for IPCP. Additionally, there were nine child codes that fell under one of the three parent codes (Table 2). For the institutional pharmacy IPPE data, four parent codes were identified: interprofessional collaborative communication, roles and responsibilities, teamwork, and patient-centered care. Ten of the child codes identified fell under one of the four parent codes (Table 3). Analysis of the frequency of codes sorted by descriptors was completed for both community and institutional data sets, and each reflection was only coded once if it met the criteria. Codes that had a greater than 10% difference in frequency when sorted by descriptors were reported (Table 4). This study was approved by the University of Kansas Institutional Review Board.

Table 2.

Themes Identified in Reflections Submitted by Students Completing Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences in Community Settings

Table 3.

Themes Identified in Reflections by Students Completing Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences in Institutional Settings

Table 4.

Frequencies of Themes Identified by Students Completing Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences in Community Settings that Demonstrated more than a 10% Differences with Regards to Site Descriptors (Rural vs. Urban & Independent vs Chain)

RESULTS

Of the 277 pharmacy students assigned to complete IPPEs during the 2016-2017 academic year, 228 reflections were submitted. First-year students submitted 130 community IPPE reflections and second-year students submitted 98 institutional IPPE reflections, for response rates of 93% and 71%, respectively. The EEO continued to work with students who did not complete the assignment, but the late submissions were not received prior to data analysis. Those assignments not included in the analysis underwent review by the EEO for completeness. If a student did not submit a reflection, the EEO continued to monitor their progress through IPPE and APPE coursework.

The pharmacies that served as community IPPE sites were primarily rural (51%) and independent (65%), and the pharmacies that served as institutional IPPE sites were primarily rural (54%) and traditional (86%). Approximately half of the students explicitly reported exposure to IPCP during their community IPPE, while all students reported exposure to IPCP during their institutional IPPE. The institutional IPCP exposures documented in the reflections were further defined by type of exposure: occurring during rounds or team meetings (57%), shadowing or interviews (30%), or informal moments (26%). Many of the students had multiple types of IPCP exposure in this setting. Complete site and exposure to IPCP results are provided in Table 1.

The community IPPE reflections included 222 statements that described opportunities for IPCP and 135 statements that described barriers to IPCP. Additionally, the effect of IPCP on patient-centered care was noted in 98 statements. The community IPPE reflections most commonly identified extended pharmacy services, networking and relationships, phone calls, and technology as opportunities where IPCP could occur between community pharmacists and interprofessional health care teams. Direct access to prescribers, timely communication, pharmacy workload, hierarchy, and access to patient health data were frequently cited as barriers to IPCP for community pharmacists. Table 2 reports the frequency with which students identified these opportunities and barriers child themes. A secondary finding demonstrated notable differences in the opportunity and barrier themes dependent on the practice setting (chain vs independent) and also the location (urban vs rural) reported in Table 4.

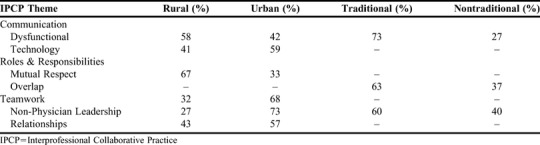

In the institutional IPPE, student reflections included statements reflective of IPCP in regard to communication (166), roles and responsibilities (108), teamwork (24), and patient-centered care (74). Students most commonly noted IPCP communication occurred when collaborators encouraged all team members to speak up, technology was used by team members, communication lines were perceived as open, and the SBAR15 (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) communication format was used by team members. The students’ reflections also described evidence of dysfunctional communication in the institutional setting. Students acknowledged the level of overlap between professional roles and the importance of coordination between professions when reflecting on team member roles. Additionally, students reflected on team members having mutual respect for one another’s roles. Students reflected on interprofessional teams and noted the importance of having positive personal and professional relationships that facilitated effective teamwork. Additionally, many students noted that teams led by nonphysicians enhanced teamwork. The frequency of the most commonly recognized themes for communication, roles and responsibilities, and teamwork are reported in Table 3. Furthermore, institutional IPPE reflections demonstrated notable differences between the roles and responsibilities, communication, and teamwork themes dependent on the practice setting (traditional vs nontraditional) and location (urban vs rural) as reported in Table 5.

Table 5.

Frequencies of Themes Identified by Students Completing Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experiences in Institutional Settings that Demonstrated more than a 10% Differences with Regard to Site Descriptors (Rural vs. Urban & Traditional vs. Non-Traditional)

Further review of the reflections yielded representative statements describing the students’ experiences and perceptions of IPCP across both community and institutional IPPE sites. Representative statements are included for the community and institutional IPPE reflections in Table 2 and 3, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Integrating a reflective assignment for first- and second-year pharmacy students that focused on interprofessional collaboration during IPPEs proved to be a beneficial component of the experiential and interprofessional curriculum at our institution. The assignment required students to reflect on when IPCP occurred and to comment on observations that either facilitated or hindered a pharmacist from engaging with other health care professionals during patient care. Through qualitative analysis of the reflections, we demonstrated that students can learn from real time, authentic interprofessional collaboration at clinical sites if their attention is specifically focused on these encounters through a structured reflective assignment. In addition, the reflections provided data for experiential education faculty members to use in identifying the IPE experiences or lack thereof available to students in community and institutional settings.

Our data revealed that pharmacy students' experience and exposure to IPCP in community pharmacy practice settings could be improved. There is a dearth of information regarding the inclusion of community pharmacists on the interprofessional health care team. Additionally, many clinicians and educators with experience in the field of pharmacy and IPE are aware that there are numerous perceived and real barriers for many pharmacists in this practice setting. The experiences noted in the students’ reflections suggest that more opportunities exist for IPCP in rural and independent community pharmacy settings. Community pharmacies in these settings were more likely to offer extended pharmacy services (eg, medication therapy management visits, group education classes, and consultants at long-term care facilities), and there were additional opportunities for developing relationships with other members of the interprofessional team. However, students noted that these rural and independent pharmacies had greater difficulty in gaining access to patients’ health data which is needed to provide extended pharmacy services, and this created a barrier to IPCP. Greater use of technology, particularly in the form of making more phone calls to interprofessional colleagues, appeared to be an important opportunity to explore to enhance IPCP in urban, chain pharmacies. In both settings, the pharmacy workload and having direct access to other interprofessional team members provided barriers to IPCP. Faculty members in experiential education could consider initiating conversations with practice sites that serve as community pharmacy experiential sites to raise awareness, provide professional development, or suggest that students on practice experiences could address the opportunities and barriers in order to advance the role of community pharmacists on interprofessional teams. Continued exploration of this topic is important as pharmacy students are exposed to community pharmacy through their experiential education and employment while in school, and the highest proportion of actively practicing pharmacists work in this setting.16

This difficulty in bridging the community pharmacy setting into IPCP raises another interesting consideration when looking more globally at how IPCP is traditionally defined and recognized. Pharmacy is not the only profession where the practice setting is usually removed from direct interaction with other professions. This type of asynchronous care presents a challenge for organically connecting these practices so that effective collaboration can occur and result in positive patient outcomes. The perspective of the interprofessional health care team needs to continue to evolve to ensure inclusion across the continuum of patient care to effectively accomplish the Triple Aim in all settings.

Our data confirmed that all pharmacy students are being exposed to IPCP in the institutional pharmacy practice setting, but there is room for continued improvement in the quality of IPCP exposure. This is particularly noted when comparing the students’ experience with regard to teamwork in the rural institutional setting. Nontraditional rural sites were less likely to have nonphysician leadership present; however, health professionals at rural sites were more likely to exhibit mutual respect as highlighted in the students’ reflections. Again, this provides an opportunity to engage interprofessional students on rotations to facilitate the development of teamwork in that practice setting and bridge the gap between education and practice.17 Students also noted that rural sites were highly represented in this sample, which was likely because the state of Kansas has a higher rural population than most other US states. This is an interesting finding in that most pharmacy educators expect practices in urban areas to adopt IPCP sooner than rural settings.

When reviewing the themes, two areas of interest that warrant further exploration include the negative role modeling seen by students in both community and institutional pharmacy practice settings and indicated by the hierarchy and dysfunctional communication themes identified in their reflective writings. Approximately 20% of students noted hierarchy and 25% noted timely communication as barriers to IPCP in their community IPPE experience, while dysfunctional communication was noted in approximately 30% of the institutional pharmacy reflections. In experiential education, the hidden curriculum and its influence on interprofessional learning in practice is critical to address. Evidence is emerging to support the need for more positive role modeling of interprofessional collaboration.18,19 Hierarchy, professional “turf” issues, and power dynamics are often cited as barriers to IPE and IPCP.20,21 Experiential education faculty members need to address these instances with IPPE students so it will not undermine the students’ attitudes about IPCP or, more importantly, their future collaborative behavior. This does emphasize the need for students to have further debriefing on their IPC experiences in order to work through how to approach similar environments in their future practice. Additionally, the school has a responsibility to ensure preceptors have increased support and development to facilitate this conversation with their students as well as advance IPCP. These findings can also strengthen the IPCP capacity of APPE learning environments.

This study adds to the limited literature on the qualitative evaluation of IPE exposure and experience of health professions learners early in their training in practice-based settings. Prior studies conducted in the United Kingdom and Norway employed similar methods in that they had early learners shadow either a group of medical students or a small interprofessional group and then share their observations during a focus group.22,23 These studies identified themes similar to those described in the current study. Our study presents the first evaluation of pharmacy students’ interprofessional exposure and experience with IPCP during IPPEs. Another contribution this study makes to the current literature is the practicality of the educational intervention we describe and its reproducibility by other pharmacy schools seeking to meet accreditation requirements. Furthermore, requiring individual reflections can allow for individual learner assessment in order to identify if a student has attained an established level of competence within the interprofessional team member domain of the Core Entrustable Professional Activities.24 Finally, the study uncovered emerging themes that may help to identify areas for future research, especially surrounding the factors that enhance IPCP at community and institutional pharmacies and the influence of the hidden curriculum through negative role modeling of hierarchy and dysfunctional communication patterns of interprofessional teams.

While this study has many strengths, it is not without limitations. The evaluation of the sites from students’ reflections may have been subject to reporting bias. By nature of the reflective assignment, the students self-reported their exposure to IPCP, which may have resulted in over- or underreporting of their actual exposure to IPCP. Additionally, while coder reliability was established, the nature of qualitative analysis demands a level of interpretation of the reflections in order to systematically qualify statements into broad categories. While this assignment was a strong starting point in encouraging students to be aware of IPCP in pharmacy settings, more robust debriefing of students and additional assignments assessing IPCP should be incorporated into IPPEs. Additionally, a process was not in place to remediate students who did not submit their IPPE reflection, so evaluations were not obtained for all IPPE sites.

As a result of this qualitative analysis, we are in the process of implementing changes related to IPE in IPPEs directed by our university. Targeted conversations and one-on-one development was provided to seven IPPE sites based on the students’ reflections on their experience related to hierarchy and dysfunctional communication. Additionally, the negative interprofessional role modeling will be included as a topic at future professional development conferences for preceptors. Formal post-experience debriefing sessions to discuss their IPCP experiences are now planned for students when they return to campus in the fall semester following their IPPEs. These sessions will allow students to explore both the positive and negative IPCP experiences in which they were involved. The IPE reflective assignment will continue as a requirement for both community and institutional IPPE workbooks and a formal remediation process will be developed for students who do not complete the assignment.

CONCLUSION

Incorporating a reflective assignment during IPPEs was an effective way to document student exposure to and experience in IPCP. The themes that emerged revealed that pharmacy students perceive the value of IPCP, but understand that challenges exist related to IPCP in community and institutional pharmacy practice settings. The reflections provided information for future preceptor and practice site development to enhance IPE in all practice settings, with a specific focus on enhancing IPCP exposure in community pharmacy IPPE settings. In order to fulfill curricular needs and meet national accreditation standards, schools of pharmacy should consider implementing a similar assignment to their IPPEs.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work could not have been completed without the collaboration and support of the University of Kansas School of Pharmacy Experiential Education Office.

Appendix 1. Prompt Provided to Students Completing a Reflective Assignment for an Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experience in a Community Setting

During your community rotation, you will be required to compose a reflection on your perspective of the opportunities to engage in interprofessional practice in the community pharmacy setting. Keep these reflection questions in mind:

Topic Discussion with Community Pharmacy Preceptor (highly recommended):

What are some examples of community pharmacies providing interprofessional care?

How does the patient benefit from interprofessional collaboration?

What is the value and role of the community pharmacist on the interprofessional healthcare team?

Guided Reflection Questions:

Identify potential opportunities specific to this site for interprofessional collaboration.

How can the community pharmacist enhance patient care by collaborating with other members of the interprofessional team?

What barriers to interprofessional collaboration can you identify in this specific setting?

What solutions can you think of to overcome these barriers? Short-term vs. Long-term?

Appendix 2. Prompt Provided to Students Completing a Reflective Assignment for an Introductory Pharmacy Practice Experience in an Institutional Setting

During your institutional rotation, you will be required to complete interprofessional tasks and compose a reflection on your experience and perspective of engaging in interprofessional practice in the institutional pharmacy setting.

Interprofessional Scavenger Hunt. Complete at least 2 of the listed IPE tasks:

Shadow or interview members of the interprofessional team at the institution where you are and learn more about their profession. Describe their roles and responsibilities pertaining to patient care.

Attend interprofessional rounds, huddle, or care team meeting. Reflect on how the team is communicating and working together in a patient-centered manner.

Interact meaningfully with another member of the interprofessional team regarding a mutual patient.

Identify a situation where you heard interprofessional team members (or you) use SBAR (Situation Background Assessment Request/Recommendation) or a missed opportunity to use SBAR where it would have been beneficial.

Identify a situation where you heard interprofessional team members (or you) advocating for the patient and speaking up.

Guided Reflection Questions:

What did you learn about the roles and responsibilities of other healthcare professionals on the interprofessional team?

How do you see this relating to the pharmacy role on the team?

What were some positive examples of interprofessional communication and what were some areas for improving interprofessional communication? Expand on how this will influence patient care.

What is your biggest lesson learned about interprofessional team-based care in the institutional pharmacy setting?

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva: WHO; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education 2013 Educational Outcomes. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(8):Article 162. doi: 10.5688/ajpe778162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education. Accreditation standards and guidelines for the professional programs in pharmacy leading to the doctor of pharmacy degree. 2011. https://www.acpe-accredit.org/pdf/FinalS2007Guidelines2.0.pdf. Accessed July 20, 2015.

- 4.Interprofessional Education Collaborative Expert Panel. Core competencies for interprofessional collaborative practice: report of an expert panel. Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox M, Naylor M. Transforming patient care: aligning interprofessional education with clinical practice redesign. Conference recommendations; Atlanta, GA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Affairs. 27:759-769. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Abu-Rish E, Kim S, Choe L, et al. Current trends in interprofessional education of health sciences students: a literature review. J Interprof Care. 2012; 2012;26:444–451. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2012.715604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loversridge J, Demb A. Faculty perceptions of key factors in interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2015;29:298–304. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2014.991912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine. Measuring the impact of interprofessional education (IPE) on collaborative practice and patient outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones KM, Blumenthal DK, Burke JM, et al. Interprofessional education in introductory pharmacy practice experiences at US colleges and schools of pharmacy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2012;76:80. doi: 10.5688/ajpe76580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009;14(4):595–621. doi: 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Austin Z, Gregory PA, Chiu S. Use of reflection-in-action and self-assessment to promote critical thinking among pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(3):Article 48. doi: 10.5688/aj720348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briceland LL, Hamilton RA. Electronic Reflective Student portfolios to demonstrate achievement of ability-based outcomes during advanced pharmacy practice experiences. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(5):Article 79. doi: 10.5688/aj740579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shrader S, Hodgkins R, Laverentz D, et al. Interprofessional Education and Practice Guide No. 7: Development, implementation, and evaluation of a large-scale required interprofessional education foundational programme. J Interprof Care. 2016;30(5):615–619. doi: 10.1080/13561820.2016.1189889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. SBAR communication technique. http://www.ihi.org/explore/SBARCommunicationTechnique/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed June 7, 2017.

- 16.Midwest Pharmacy Workforce Research Consortium. Executive summary of the final report of the 2014 national sample survey of the pharmacist workforce to determine contemporary demographic practice characteristics and quality of work-life. http://www.aacp.org/resources/research/pharmacyworkforcecenter/Documents/ExecutiveSummaryFromTheNationalPharmacistWorkforceStudy2014.pdf. Accessed on July 14, 2017.

- 17.Institute of Medicine. Measuring the impact of interprofessional education on collaborative practice and patient outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rotz M, Duenas G. “Collaborative-ready” students: exploring factors that influence collaboration during a longitudinal interprofessional education practice experience. J Interprof Care. 2016;30:238–241. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2015.1086731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pollard K. Non-formal learning and interprofessional collaboration in health and social care: the influence of the quality of staff interaction on student learning about collaborative behavior in practice placements. Learn Health Social Care. 2008;7:12–26. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker L, Egan-Lee E, Martimianakis M, Reeves S. Relationships of power: implications for interprofessional education. J Interprof Care. 2011;25:98–104. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.505350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fougner M, Horntvedt T. Students’ reflections on shadowing interprofessional teamwork: a Norwegian case study. J Interprof Care. 2011;25(1):33–38. doi: 10.3109/13561820.2010.490504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall P. Interprofessional teamwork: Professional cultures as barriers. J Interprof Care. 2005;(Suppl 1):188–196. doi: 10.1080/13561820500081745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dickinson C, Pearson P. Practice-based interprofessional education: looking into the black box. J Interprof Care. 2007;21(3):251–264. doi: 10.1080/13561820701243664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haines ST, Pittenger AL, Stolte SK, et al. Core entrustable professional activities for new pharmacy graduates. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(1):Article S2. doi: 10.5688/ajpe811S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]