Abstract

Objective. To develop and assess the usefulness of a structured onboarding process and tool at a school of pharmacy to improve the overall onboarding experience for new faculty members.

Methods. An assessment of a previously existing, informal onboarding process was conducted from January 1 to February 28, 2017. A structured onboarding tool was developed based on interviews with nine recently hired faculty members regarding their experiences with this legacy, unstructured onboarding process. Nine faculty members who onboarded while the legacy onboarding process was in place and six faculty members who onboarded after the new, onboarding tool was in place were included in the study. The experience of the pre-tool cohort was compared to that of the post-tool cohort.

Results. More positive responses in the post-tool cohort were obtained compared to the pre-tool cohort in regard to timeline, expectations, and mentorship. More negative responses for the post-tool group were observed for communication. Overall utility of the onboarding tool changed from 56% (pre-tool group) to 80% (post-tool group). Free text feedback included recommendations to rearrange tasks throughout the onboarding process; clarifying mentor responsibilities and expectations; and providing an overview of the checklist to new faculty members on day 1.

Conclusion. Overall, a structured onboarding process tool improved the onboarding experience for new faculty members. Given the lack of literature regarding a structured onboarding process in the academic setting, further refinement and analysis of the onboarding tool is needed.

Keywords: faculty, onboarding, orientation, faculty retention

INTRODUCTION

How new employees are assimilated into an organization can determine their short-term and long-term success, yet only 32% of companies provide a formal onboarding experience for new employees.1 A successful onboarding experience provides opportunities to better acclimate to a new environment, perform key job tasks more quickly, learn about the organization’s mission and values, learn how to access resources, and determine how he or she may contribute to institutional growth and success. The onboarding process can set any new employee up for early success and increase task efficiency, two key factors that contribute to employee satisfaction and overall job performance.2 An unsuccessful onboarding experience in academia, specifically, can lead to faculty members not fitting in well with the organization’s culture, having unrealistic expectations, lacking an understanding of organizational goals, and being unable to build relationships.3

The majority of new employees are able to perform most of their required tasks at a functional level within three months of starting a new position.1 The first 90 days of working for a new employer have been identified as a critical time period for new team members to gain efficiency, confidence, and develop a commitment to the organization.2,4 Employees who participate in an onboarding program are 69% more likely to be retained after three years compared to those who do not.4 Some of the most successful onboarding programs begin assimilation prior to an employee’s first day.1 In academia, pre-employment onboarding processes are ideal for faculty positions given the often lengthy time period between a faculty member’s hire date and start date. A properly designed and structured onboarding system leads to increased job satisfaction and decreased employee turnover.1

There is minimal literature regarding a structured onboarding process for faculty members. However, the onboarding of new faculty members has been referred to as “a critical strategic event…that involves a significant investment of time, attention, effort, and money.”3 Given the resources, relationships, and training necessary for new faculty members to be successful in the academic setting, it is important for institutions to explore ways to improve faculty onboarding. The purpose of this project was to determine how a structured onboarding process at a school of pharmacy could be used to improve the overall onboarding experience for new faculty members.

METHODS

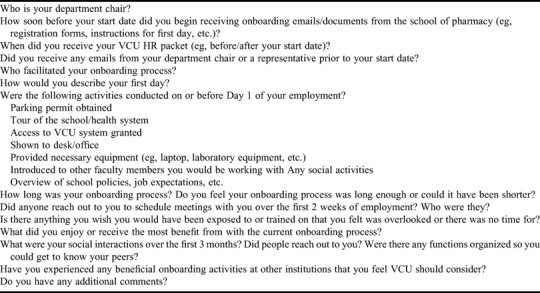

An assessment of the previously existing, informal onboarding process was performed at the Virginia Commonwealth University School of Pharmacy in Richmond, Virginia. From January 1, 2017, to February 28, 2017, nine faculty members hired within the previous two years were interviewed to identify what orientation activities occurred during their informal onboarding process. Faculty members interviewed were from the Departments of Medicinal Chemistry, Pharmaceutics, and Pharmacotherapy and Outcomes Sciences. Key administrative personnel were also interviewed to determine what steps were taken when a new employee was onboarded. Each interview was designed to identify components of the legacy onboarding process that had proved to be helpful as well as those that had been unhelpful or absent from the program. Questions asked during the interviews are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questions Asked of Recently Hired Faculty Members Prior to Implementation of an Onboarding Tool in a School of Pharmacy

A thorough literature search was performed to identify any onboarding standards of practice in the academic setting. PubMed, Ovid, Google Scholar, and ERIC databases were searched using a combination of key words including onboarding, cost, faculty, orientation, academic, academia, new, hire, and value. A single article was found regarding academic onboarding of medical school faculty members.3

Following review of the legacy, unstructured onboarding process and the literature search, meetings were conducted with departmental administrators, information technology personnel, and human resource professionals in order to identify the necessary components of the onboarding process and resources needed for new faculty employees. In these meetings, a pharmacy school faculty or staff member was selected to serve as a contact for each component of the onboarding process identified based on their expertise and ability to provide support for the new hire. In addition, establishing a contact provided accountability to the process and ensured faculty members were onboarded in a timely manner. This information, along with the feedback from faculty interviews, was then used to construct the new onboarding tool.

The new onboarding tool consisted of a list of tasks to be completed by the employee, along with a list of correlating resources (ie, website and policy links) and contact information for administrative personnel (tool is available upon request from authors). Each task was given a completion date. The onboarding tool was distributed to new faculty hires immediately following contract completion and prior to their start date. The target date for completion of each task outlined in the tool was set for 60 days after the new hire’s first day on campus. The onboarding tool was designed to be maintained by the new faculty member. Following completion of the onboarding tool, an administrative version was created and given to key supervisory and administrative personnel to ensure transparency and accountability throughout the onboarding process.

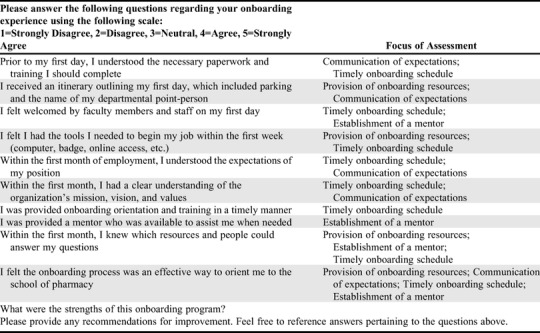

A survey was created to assess the new, structured onboarding process; determine aspects that needed further improvement; and provide data for comparison with the legacy onboarding process. The survey instrument consisted of 10 questions that were rated using a five-point Likert scale along with a free text box for additional feedback. The questions were formulated based on four areas of need identified during faculty and administrator interviews: consistent communication of expectations; a timely onboarding schedule; provision of onboarding resources; and the establishment of a mentor relationship (Table 2). Survey responses were then grouped into three categories, agree/strongly agree, neutral, and disagree/strongly disagree.

Table 2.

Onboarding Assessment Survey Administered to New Faculty Members in a School of Pharmacy

The survey instrument was distributed to nine faculty members who were hired within the previous two years under the older, legacy onboarding process and five faculty members who were hired between June and August 2017, after introduction of the new, structured process that used the onboarding tool. Survey respondents who participated in the previously existing onboarding process were identified as the “pre-tool group” while those who participated in the new, structured onboarding process were identified as the “post-tool group.” The new faculty members had received the new onboarding tool following the signing of their contract, and received the onboarding survey 60 days after their first day on campus. All responses were de-identified prior to collection. No statistical tests were used to compare the differences between the groups. This study was submitted to the VCU Institutional Review Board for exemption and approved.

RESULTS

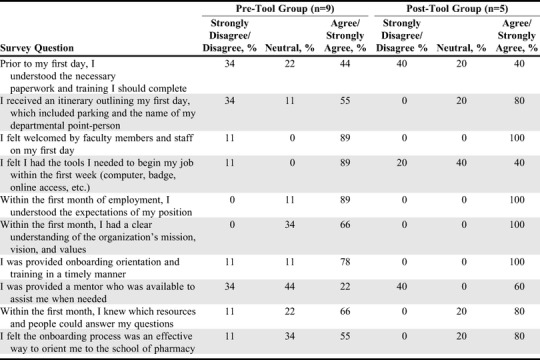

Members of the pre-tool group consisted of six assistant professors and three associate professors. Six members were employed in the Department of Pharmacotherapy and Outcomes Sciences. Each of the three remaining members were employed in the Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Department of Pharmaceutics, and the Dean’s Office, respectively. The post-tool group consisted of three assistant professors and one associate professor within the Department of Pharmacotherapy and Outcomes Sciences, and one associate professor within the Department of Pharmaceutics. One new faculty hire was a VCU Health-System employee and the others were hired externally. All pre- and post-tool group members successfully completed their onboarding surveys. Survey results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Survey Responses of New Faculty Members Hired Before and After Implementation of a Structured Onboarding Process and Tool

Survey results from the pre-tool group demonstrated opportunities for improvement in the four previously mentioned categories of communication, timeline, expectations, and mentorship. Fifty-six percent of faculty members in the pre-tool cohort were not provided with a list of onboarding activities prior to their first day of work; 44% were provided with an itinerary that included an outline of their first day, parking directions, and identification of a point person. As expected, only 22% of pre-tool respondents were assigned a mentor that was available throughout the onboarding process. Results for the pre-tool group showed positive responses with regards to morale and job preparedness, with 89% of respondents in the pre-tool cohort stating they were adequately supplied with the tools needed to begin their jobs within the first week, felt welcomed by existing staff members, and understood their job expectations within the first month.

One hundred percent of respondents in the post-tool cohort agreed that the new onboarding system was timely, adequately outlined their expectations and organizational goals, and was led by welcoming team members. However, some found the onboarding process prior to the first day of work to be suboptimal. While 80% of new employees received a detailed itinerary, 60% ultimately did not understand the necessary training and paperwork required prior to day 1. Less employees in the post-tool group felt they were adequately supplied with the necessary tools to perform job functions compared to the pre-tool group. Sixty percent of the post-tool cohort reported that they were assigned a mentor who was available to them throughout the onboarding process.

DISCUSSION

Assessment of the legacy, unstructured onboarding process and the new structured onboarding tool demonstrated improvements in the new onboarding process as well as opportunities for further improvement. Overall, the use of an onboarding tool resulted in a higher agreement rate in the post-tool group on eight of the 10 survey questions. In addition, an increase from 56% (pre-tool group) to 80% (post-tool group) with regards to the overall utility of an onboarding process was recognized. Faculty members who used the new onboarding tool gave more positive responses to questions in the following categories: timely onboarding schedule, communication of expectations, and establishment of a mentor relationship. However, opportunity for improvement of the new onboarding tool was identified in the area of communication of expectations in that a majority of the responses for the survey item “overall communication prior to hire day 1” were negative. One possible cause identified for the poor communication with the new hires was that the college had incorrect contact information, particularly for those faculty members whose previous work e-mails had been deactivated and those who were transitioning to new roles within the organization. Receipt of the onboarding tool was therefore delayed for these employees and affected the overall guidance they received and their understanding of expectations. Based on this feedback, future employees will have their information verified if no response is received by the school’s human resources department following the initial welcome email but prior to day 1.

The onboarding tool was designed to guide new members through the first 60 days of work. The onboarding tool outlined instructions and tasks to be completed within specific timeframes, ie, prior to day 1, days 1-3, within the first week, within the first 30 days, and after 60 days of employment. There was positive feedback regarding the overall timeline for completion of the components of the new onboarding tool, and more positive responses for the timeliness of the training and orientation component of the onboarding process compared to that of the legacy process. Feedback from respondents included a request for items to be moved to later timeframes to improve process fluidity and to introduce other, more important information at an earlier date. Some felt that providing an overview of the checklist to new faculty members on day 1 would be beneficial. These changes were made and implemented for future onboarding faculty members.

One shortcoming demonstrated by the survey results was that the post-tool cohort did not consistently receive the necessary tools or equipment to begin their job within the first week. The post-tool cohort reported more positive responses regarding the welcoming nature of existing faculty members and felt more comfortable asking for help and clarification in this environment. Additionally, the provision of contact persons within each section of the onboarding tool aided in outlining the resources available to new faculty members and resulted in positive feedback from most faculty members in the post-tool cohort.

During interviews, faculty members in the pre-tool cohort suggested that the provision of mentors would provide new faculty members with a useful resource throughout the onboarding process. Therefore, department administrators assigned a mentor to each new faculty member. Mentors typically were chairs and senior faculty members within the new faculty member’s department. Each mentor met with their mentee at least once within the first 30 days that the new hire was on campus to provide recommendations and answer questions.

The survey responses of the post-tool cohort regarding the presence and utility of mentorship were more positive compared to those of the pre-tool cohort. However, survey comments from the post-tool cohort discouraged the future use of department chairs as mentors, requesting instead that they be assigned to a faculty member more equal in rank to them or at least below the department chair level. In addition, the post-tool cohort emphasized the importance of having communication with their mentor prior to the first day of work. Clarification regarding the duties of a mentor and when they should be utilized was required for two new faculty members. Based on the survey feedback, communication related to mentorship will be clarified for future employees. The feedback received regarding the onboarding tool was used to guide revisions for future use.

The limitations of this study included having a small sample size and a relatively short period to observe new onboarding faculty members. Because of the low turnover in faculty members at our institution only a few new hires joined the faculty during the study period. Additionally, one surveyed faculty member transitioned from an adjunct faculty member position with the university’s affiliated health system to an associate professor position at the school. Thus, prior knowledge of the pharmacy school’s environment and operations may have influenced this faculty member’s responses. Given the lack of literature regarding a structured onboarding process in the academic setting, further refinement and analysis of the onboarding tool is needed.

CONCLUSION

A structured process and tool for managing the onboarding process appeared to improve the experience for new faculty members. The onboarding tools clarified faculty members’ expectations, increased communication between new faculty members and the department, and provided mentorship to new faculty members. A comparison of survey responses from the pre-tool cohort with those from the post-tool cohort suggested that the revisions to the onboarding process improved most onboarding components. However, further optimization and analysis of the onboarding tool is needed and will occur in order to create an ideal onboarding process.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberdeen Group. Welcome to the 21st Century, Onboarding! http://edhecnewgentalent.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/21th-century-onboarding.pdf. Accessed August 4, 2017.

- 2.Weinstock Donna. Hiring new staff? Aim for success by onboarding. J Medical Practice Mgmt. 2015;31:96–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross WE, Huang KH, Jones GH. Executive onboarding: ensuring the success of the newly hired department chair. Acad Med. 2014;89:728–733. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch K, Buckner-Hayden G. Reducing the new employee learning curve to improve productivity. J Health Risk Manag. 2010;29:22–28. doi: 10.1002/jhrm.20020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]