Abstract

Members from Cohort 13 of the Academic Leadership Fellows Program (ALFP) 2016-2017 were challenged to present a debate on the topic: “In Turbulent Times, Pharmacy Education Leaders Must Take Aggressive Action to Prevent Further Declines in Enrollment” at the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy INfluence 2017 meeting in Rio Grande, Puerto Rico. This paper is the result of thoughtful insights emerging from this debate. We present a discussion of the question of whether pharmacy education leaders must take aggressive action or strategic approaches to prevent further declines in enrollment. There are many thoughts regarding current declines in enrollment. Some educators contend that a more aggressive approach is needed while others argue that, while aggressive actions might lead to short-term gains, a more viable approach involves strategic actions targeting the underlying causes for decreasing enrollment. This paper explores themes of enrollment challenges, current and future workforce needs, and financial issues for both pharmacy programs and students. In summation, both aggressive actions and a strategic, sustainable approach are urgently needed to address declining enrollment.

Keywords: debate, declining enrollment, recruitment, pharmacist provider, strategic planning

INTRODUCTION

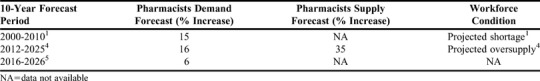

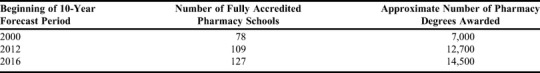

In 2000, The Pharmacist Workforce Study published by the US Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) highlighted a nationwide shortage of pharmacists, with a projected increase of approximately 15% (28,500) in the number of active pharmacists over the 2000-2010 decade (Table 1).1 At that time, there were 78 schools of pharmacy producing roughly 7,000 graduates annually (Table 2).2 In response to the forecasted pharmacist manpower shortage, coupled with the expanding role of pharmacists on the health care team, existing schools increased enrollment and new schools offered pharmacy degree programs.

Table 1.

Pharmacist Workforce Forecasts Relative to the Number of US Pharmacy Schools and Graduates

Table 2.

Number of US Pharmacy Schools and Graduates at the Beginning of the 10-Year Forecast Periods

In 2008, an updated workforce study was issued by the National Center for Health Workforce Analysis (NCHWA) at the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) that predicted continued demand for pharmacists, with a shortfall of nearly 38,000 pharmacists by 2030.3 However in 2012, the NCHW released a revised pharmacist workforce projection (calculated using the Health Workforce Simulation Model) that predicted a 35% increase in supply versus a 16% increase in demand over the period of 2012-2025 (Table 1). These projections took into account the impact of the Affordable Care Act. The brief report predicted an excess pharmacist workforce supply by 2025.4 The report also acknowledged the model’s inability to account for future demand factors, such as changes in reimbursement, potential elimination of the Medicare Part D coverage gap, and increased integration of clinical pharmacists within medical teams and other advanced clinical roles.

A different landscape has emerged since these predictions of pharmacy workforce needs. In 2016, there were 127 fully accredited schools of pharmacy producing over 14,500 pharmacy graduates per year (Table 2). According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, the pharmacist employment growth rate is expected to be 6% from 2016 to 2026 (Table 1), in contrast to the projected 16% growth for health diagnosing/treating practitioners.5 Over this same time period, the growth rate for physicians and surgeons is expected to be 15%; physician assistants, 37%; midwives and nurse practitioners, 31%; and physical therapists, 25%.5,6 Thus, students exploring career options in a health-related profession may look to the aforementioned health care career paths that have a stronger employment outlook than pharmacy.

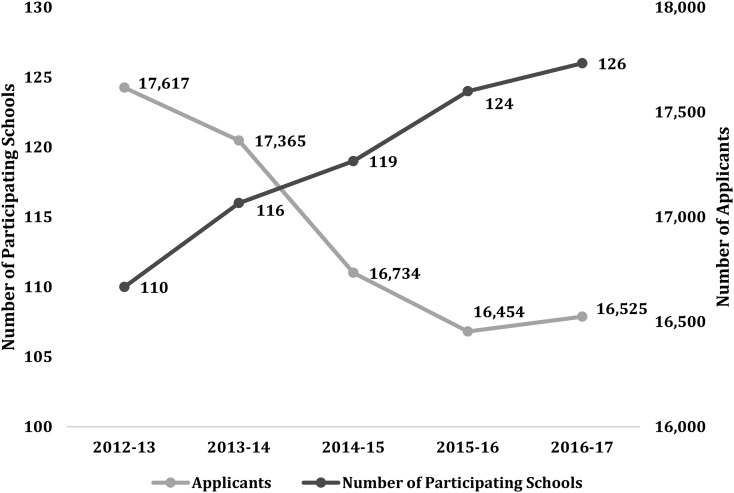

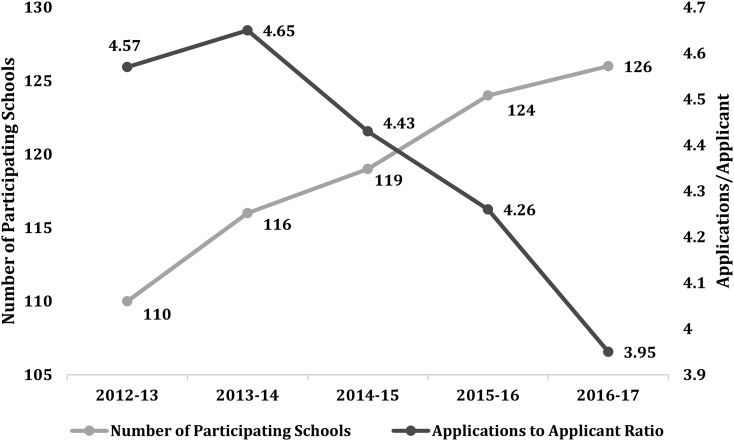

To further complicate matters, applications to pharmacy schools are decreasing (Figures 1 and 2). In the 2008-2009 academic year, 72 schools used the Pharmacy College Admission Service (PharmCAS), and the total number of applicants was approximately 16,250. From 2009-2014, the number of schools participating in PharmCAS increased by 60%, while total applications remained steady at about 17,400 annually.7 During the 2016-2017 academic year, 126 schools used PharmCAS, with approximately 16,500 applicants (Figure 1).8 Similarly, the number of applicants decreased from 226 per school for the 2008-2009 academic year to just 131 per school in 2017, representing a 42% decline (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Data from AACP PharmCAS Comparing the Number of Applicants to Pharmacy Schools to the Number of Pharmacy Shools Participating in PharmCAS.

Figure 2.

Data from AACP PharmCAS Comparing the Number of Pharmacy School Applications per Applicant to the Number of Pharmacy Schools Participating in PharmCAS.

Institutions of higher education have varying levels of dependency on tuition as a revenue stream. The challenge for pharmacy education leaders is maintaining enrollment or identifying other revenue streams for their program to remain financially viable. With a shrinking applicant pool, expanding enrollment, and a weakening employment outlook for graduates, schools are facing a vital question: should pharmacy education leaders take aggressive action in order to prevent further declines in enrollment? If so, what action(s) should be implemented, and how can this be accomplished while still recruiting and retaining high-quality students? If not, how do pharmacy schools sustain financial viability in the face of decreasing enrollment? This paper attempts to explore ideas for strategic action that may be implemented to bring stability to both pharmacy programs and the profession.

METHODS

The debate topic, “In Turbulent Times, Pharmacy Education Leaders Must Take Aggressive Action to Prevent Further Declines in Enrollment,” was assigned to fellows participating in the 2016-2017 Academic Leadership Fellows Program (ALFP). In September 2016, two teams of six members were randomly assigned to debate either the pro or con argument to this statement, regardless of their personal agreement with the assigned position. A literature search was conducted using the following keywords: pharmacy education, health workforce, PharmD enrollment, higher education enrollment, pharmacy job market, and pharmacy graduates. Resources used were PubMed, newspapers, professional blogs, various workforce websites, web-based search engines, and pharmacy education and professional organization websites. In addition, references from selected articles were used to help identify additional publications and resources. Using this information, pro and con arguments were developed and refined over several months through team meetings via telephone conference calls. Final arguments were presented in a debate format at the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy (AACP) INfluence interim meeting held in Rio Grande, Puerto Rico, February 2017.

POINT: PHARMACY EDUCATION LEADERS MUST TAKE AGGRESSIVE ACTION TO PREVENT FURTHER DECLINES IN ENROLLMENT

Pharmacy education leaders are confronted with the challenge of maintaining specific enrollment targets in order to remain financially viable while also maintaining quality in instruction and admission standards. Allowing present enrollment levels to decrease substantially will lead to an anemic educational enterprise that impacts the quality of instruction and the academic preparation of pharmacy graduates. Talented students are the lifeblood of the pharmacy education enterprise and a future investment in the profession of pharmacy. We must act aggressively to support a thriving and flourishing pharmacy profession as pharmacists are medication experts and essential members of the health care team.

Aggressive action is required to meet the practice paradigm shift.

The pharmacy profession is experiencing a paradigm shift that empowers pharmacists with the authority and autonomy to manage medication therapy with accountability for patient outcomes. Pharmacists are uniquely positioned to provide both the clinical expertise and administrative leadership necessary to assure high quality medication therapy management through the delivery of pharmaceutical care. However, this level of care can only be accomplished through collaboration with other health care providers, patients, and caregivers. By practicing in a health care system that has an established interdisciplinary process, patients’ drug therapy management can be coordinated through a team approach to achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes.

Momentum is building to expand pharmacists’ roles in clinical decision making as an integral part of the health care team. Aggressive action is needed to recruit, admit, educate and graduate change agents for the profession. It is important for pharmacy schools to educate students to be pharmacist providers of patient-centered services and train them to facilitate needed conversations to produce behavioral change in clinical practice.

In 2013, pharmacy education and leaders of professional health care organization from Washington State sought and received an informal opinion from the State Attorney General that recognized pharmacists as providers of primary care services, which legally entitled them to payment for their clinical services. This action notified the Washington State Office of the Insurance Commissioner and all commercial payers that pharmacists are health care providers entitled to compensation for services within the scope of their practice. In 2015, the Washington State Governor codified this opinion by signing State Senate Bill 5557 (Health Carriers – Services Provided by a Pharmacist), requiring all commercial plans within the state to contract with pharmacists as network medical providers, using the full spectrum of medical billing codes for payment. The impact of this law was to prevent insurance companies from denying payment to pharmacists for provider care services. The law went into effect in the inpatient setting in 2016 and outpatient settings in January 2017.9

Washington State’s landmark provider status legislation represents a new business model for the profession of pharmacy. Pharmacy services are moving from being perceived as a cost center to becoming a revenue generator in the health care arena. At the end of 2016, over 33,000 medical claims for pharmacist provider services were paid in Washington State, averaging over $100 per claim.10 This new business model posits pharmacists as the primary managers of patients’ medication therapy and effectively creates a new job market for pharmacists while incentivizing a shift in practice expectations for pharmacy graduates. Increasingly, clinics, community pharmacies, and health systems in Washington are seeking to hire pharmacist providers who are responsible for collaborative drug therapy management rather than filling prescriptions. In fact, multiple health systems in the Seattle area (ie, Virginia Mason, Swedish, and Evergreen) moved pharmacists into provider roles in over 44 medical clinics in 2017 resulting in multiple openings for pharmacist positions.11 For this new model, pharmacist providers are paid not by the pharmacy department (the cost center) but by the medical group (the revenue center). In addition, several independent and chain community pharmacies are beginning to provide expanded clinical care services, which creates new non-dispensing-based revenue streams.11 These innovative services include treatment of minor ailments and conditions with prescription medications, point of care testing, and chronic disease state management.

Just as the concept of pharmacists as immunizers grew slowly at first, the role for pharmacists as providers of primary care services is expanding quickly and gaining momentum. Given the push for provider status and the scope of practice expansion in states like Washington, demand for pharmacists (forecasted at 6%5) may increase to match that of other health care providers (physician assistants at 37%,13 nurse practitioners at 31%,14 and physical therapists at 25%6). As pharmacist provider status becomes a legislative reality in other states and at the federal level, business incentives will shift to support compensation for the value of pharmacist-provided direct patient care services. This movement will create new and expanded employment opportunities for pharmacist providers in dramatic ways. For pharmacy education, the expansion of pharmacy services means aggressive action is needed to grow the pool of applicants so that the best and brightest students are recruited to ensure future employment demand for pharmacist providers.

Pharmacy as a profession must improve its reputation and increase positive awareness within the community.

The number of applications to pharmacy schools was lower in 2015-2016 compared to that in previous years and compared to the number of applications to other health care professions schools.12-16 While there are varied reasons for this decline, one factor may be the public’s misperception of or indifference to the roles that pharmacists play within the health care team. With minimal exposure to pharmacists in the past, potential pharmacy student candidates may overlook pharmacy as a career choice.

According to a Gallup poll, “Honesty/Ethics in Professions,” pharmacists are consistently rated highly as honest and ethical.17-20 While it is accurate to state that pharmacists have ranked second only to nurses over the past decade,18 a critical analysis of the 10-year historical data19 (2007-2016) provides further insight. The mean public approval rating of very high or high is 70% while the rating of average hovers around 26%. This means that one in four people view the pharmacy profession as average in terms of honesty and ethics, indicating that there is room for improving the public perception of pharmacists.

Media and the public play a critical role in the perception of pharmacy. Stereotypical portrayals of pharmacists by traditional and social media may contribute to the misunderstanding of the pharmacist’s role. Negative pharmacist portrayals by the motion picture and television broadcast industries may make for engaging entertainment, but unintentionally create a negative image of pharmacy as a career choice.21 A recent review of pharmacists depicted in US film and television media from 1970 to 2013 found that pharmacists were portrayed negatively 63% of the time.21 Negative advertisements inappropriately involving the pharmacy profession may also be harmful to the pharmacist’s image as well. For example, in 2005-2006, the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League (NARAL) published an advertisement casting aspersions on pharmacists regarding birth control legislation.22 The tagline, “Who invited the pharmacist?” in large print against an image of two sets of bare feet and one set of shoes under a blanket, was designed to elicit a strong emotional reaction. In small type, the advertisement answers the question: “Nobody. Yet in 2005, 15 states considered legislation that would allow pharmacists or pharmacies to deny women access to their birth control.”22 Irrespective of a person’s position on birth control, vilifying the pharmacist in such a manner helped to create a harmful bias in the minds of some college-ready students, other health care providers, and the public at large.

In response, the Academy is actively involved in promoting a positive image of pharmacists. The AACP Strategic Plan 2016-2019, Priority No. 2 “Creating a New Portrait of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Careers,” delineates actions involved in creating a new portrayal of pharmacists and pharmacy careers to recognize pharmacists as highly accessible and trusted health care providers in both traditional and new settings.23 Pharmacy education leaders have the opportunity and ability to aid in this strategic plan. Action is needed at the national, state, and local level to recruit prospective students and increase the awareness and perception of the pharmacy profession. According to the results of a 2017 Gallup poll, friends, family, and community leaders are the most common informal sources of advice when college-aged students make decisions about a college major.24 Holding outreach events at local high schools, community colleges, and universities; developing partnerships with feeder schools; establishing a professional presence at local events; and encouraging recruitment by preceptor pharmacists are all viable recruitment strategies.

Finally, pharmacists and pharmacy educators critically evaluating and changing their views and perceptions of the profession are important. Pharmacy education and professional organization leaders must reach out to practicing pharmacists to learn how to best represent the profession, increase personal professional satisfaction to minimize burnout,25 and educate pharmacists regarding the changing status of the practice. Pharmacists who find personal satisfaction in their career choice can be excellent role models for prospective and current pharmacy students. All practicing pharmacists and pharmacy educators can find ways in their local communities to enhance the awareness and reputation of their profession. Also, grassroots efforts can help in promoting the pharmacy profession and the important role of the pharmacist to the public and potential applicants, as well as within the profession.

Enriching the applicant pool aids in creating demand in areas of quality and quantity.

Because higher education is dependent on student enrollment and tuition revenue, recruitment and retention should be a core component to maintaining enrollment. In response to recent decreases in the pharmacy applicant pool, the AACP strategic plan outlines Priority 1: Enriching the Applicant Pipeline.23,26 This plan specifies goals and objectives related to pipeline expansion, applicant pool, and diversity. Adams and Law discuss the strategic priority and initiatives with suggestions to aid in the realization of this strategic priority. 26

An appreciation for student selection of a major or career is informative. Several factors influence a student’s choice of a college major, including the students’ personalities, interests, abilities, and activities. Experiences in college including enjoyment of courses, exploratory interest activities, parental expectations, earnings expectations, and perceived satisfaction in the work environment also impact major selection.27,28 Students who select pharmacy as a major typically enjoy science, aspire to improve patient wellbeing, and seek career satisfaction including earnings, security, and prestige.29-31 In addition, student interaction with pharmacist role models strongly factor into their choice of a career.32

An estimated 15% to 50% of college students are undecided about a major or are in exploratory programs, and a large percentage of students will change their major.33-35 Because health sciences and technologies was the most popular general field of choice by students taking the American College Test (ACT),34 the pool of incoming undecided majors may be a rich source of pharmacy applicants. Programs involving active participation with pharmacist role models tend to aid in recruitment of students to the pharmacy profession. Partnering with liberal arts and science colleges to tap into this pool might be fruitful. Furthermore, there is a trend for community colleges to develop “guided academic pathways” mapped to groups or clusters of related careers known as “meta-majors.”36 Partnering with institutions with health science “meta-major” pathways may result in an additional source of pharmacy applicants.

The issue of student financial need is another consideration for recruitment, retention, and attrition. Student and family concerns about the “sticker price” of pharmacy education and student debt may influence student applications and decisions regarding which institution to attend. Recent data from AACP reveals that approximately 86% of pharmacy student graduates incurred debt to finance their education, with a student-reported median debt of $130,000 for public institutions and $200,000 for private institutions.37

No specific data exist for pharmacy student attrition rate arising from unmet financial needs, either for the pre-professional or professional years. The AACP Office of Institutional Research and Effectiveness obtains data from annual surveys, where the attrition rate for the professional years is reported publicly as an aggregate of “academic dismissals, student withdrawals and delayed graduations,” though the information in each distinct category is not reported publicly.38 From 2012-2016, an aggregate attrition range of 10.2%-12.0% was observed for the professional program. Since first calculated, the range of estimated attrition has been 1.5%-15.6%.39

One mechanism to minimize student attrition because of financial stress is to offer students need-based scholarships. These types of scholarships could serve to retain less affluent students, resulting in increased institutional retention and improved graduation metrics.40 Analyses performed by the University of Kentucky revealed that significant numbers of low- to moderate-income undergraduates were leaving the university because of financial aid gaps of $5,000-$7,000.41 Anecdotal evidence suggests that international students may be at risk of dropping out of programs because of unanticipated financial concerns.42 Similarly, tuition discounting can aid in meeting enrollment goals, which facilitates attracting increased numbers of students and high quality students. The caveat is that steep discounting can put institutions at risk of reduced revenue.41,43,44 If a discounting strategy is employed, institutions need to increase enrollment to strike a balance of increased net tuition revenue (tuition revenue less financial aid) in the face of decreased net tuition per student.41

Another area of focus in the academy is holistic admissions. The AACP has hosted admission workshops on holistic review, where an applicant’s combined abilities and potential is given balanced consideration and includes the student’s background, challenges overcome, extracurricular activities, experiences, and academic abilities. Admission interviews, either traditional structured interviews or multiple mini-interviews, provide an opportunity to better understand an applicant’s abilities and potential for growth in areas of leadership, initiative, resilience, self-efficacy, empathy, integrity, critical thinking, adaptability, and other non-cognitive attributes.32,45,46 Declining enrollments present an opportunity to develop and assess innovative admissions processes and corresponding student success in areas of knowledge, skills, abilities, behaviors and attitudes essential for graduating pharmacy students.

Diversity recruitment is another critical focus of higher education in general and of pharmacy and other health professions in particular.31,47,48 Recruitment of bilingual and multilingual students is important, particularly in practice areas where languages other than English are spoken. Because strong counseling communication skills are essential to the practice of pharmacy, admissions evaluation of a bilingual candidate might involve an oral English proficiency assessment administered by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages.49,50 Candidates meeting minimum proficiency levels may require additional guidance and instruction to improve English language proficiency, intelligibility, and accent reduction to ensure the students’ success in pharmacy school.

Pharmacy education leaders need to take aggressive action to maintain enrollments. This action will require changes in both the recruitment and admissions processes. In addition, curricular modifications will need to be made for pharmacist provider status to gain traction. Such changes will require strategic, adaptive leadership approaches to navigate dynamically changing times.

COUNTERPOINT: STRATEGIC ACTION IS PREFERRED TO AGGRESSIVE ACTION IN ADDRESSING ACADEMIC PHARMACY STUDENT ENROLLMENT

The new millennium signaled not only a period of hope but change for the profession of pharmacy. As of 2000, the PharmD degree became the sole professional degree, bringing with this change the expectation for an expansion of pharmacist roles in direct patient care. In 2001, the Academy began a period of unprecedented growth that was driven by a shortage of pharmacists and a favorable employment market for pharmacy graduates. As a result, the pharmacy degree became a highly valued tuition-based university profit center. While the increased rate of academic growth has continued, the demand for pharmacists has not kept up. This trend not only puts the Academy at risk, but also our profession, communities, and patients.

The pharmacy market is not immune to the economic laws of supply and demand.

The profession is currently in a precarious situation where the supply of pharmacists is greater than the employment market demands. In addition, the number of pharmacy school applications have plateaued at a low point (Figures 1 and 2) and employment demand is declining, as reported by the Pharmacist Demand Indicator (PDI). The PDI is a data source that provides up-to-date survey results on pharmacist staffing levels.51

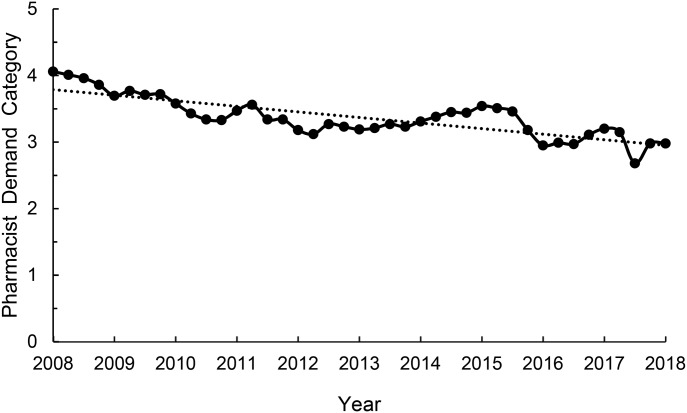

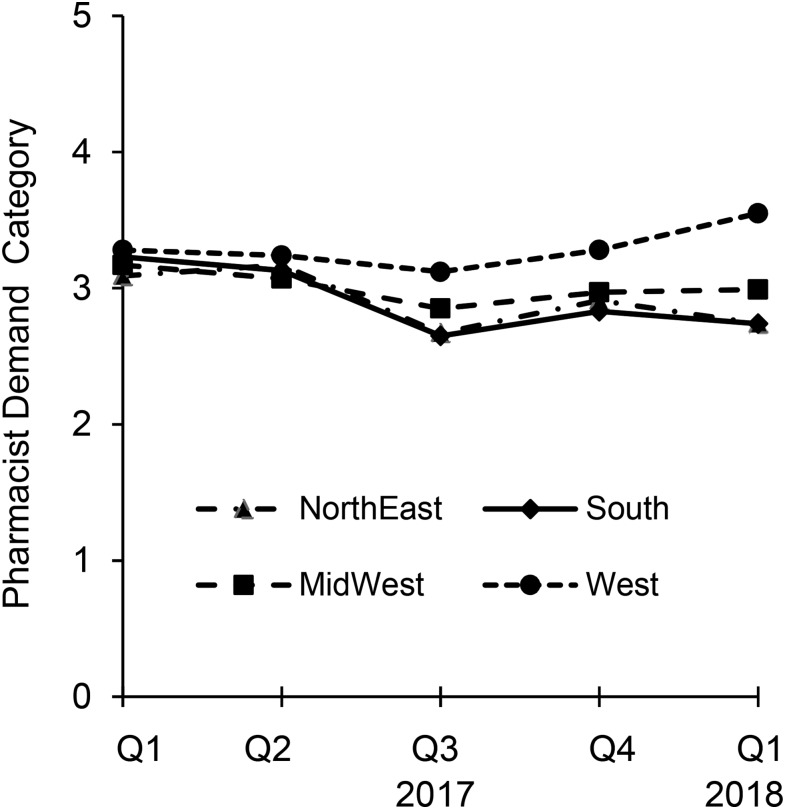

The national PDI decreased by 27% over the past 10 years (Figure 3).52 However, from March 2017 through March 2018, the average demand for pharmacists was in balance with supply.52 While regional differences exist, there is actually a trend for a higher demand for pharmacists in the West and Midwest (Figure 4). The March 2018 PDI for generalist/staff pharmacists indicated that 17 states had a balanced pharmacy workforce. Furthermore, 16 states had a moderate demand for pharmacists. Only the remaining 17 states had a surplus of pharmacists. Notably, no state had a high demand for pharmacists.55

Figure 3.

National 10-year Trend in the Pharmacist Demand Category from 2008 through March (Q1) 2018. Dotted line represents a linear regression trendline. Demand categories: 5=high demand, difficult to fill open positions; 4=moderate demand, some difficulty filling open positions; 3=demand in balance with supply; 2=demand is less than the pharmacist supply available; 1=demand is much less than the pharmacist supply available. Redrawn with copyright permission from Pharmacy Workforce Center (PWC). https://pharmacymanpower.com/about.php

Figure 4.

Regional Generalist/Staff Pharmacist Trends for the Pharmacist Demand Category from 2017 through March (Q1) 2018. Demand categories: 5=high demand, difficult to fill open positions; 4=moderate demand, some difficulty filling open positions; 3=demand in balance with supply; 2=demand is less than the pharmacist supply available; 1=demand is much less than the pharmacist supply available. Redrawn with copyright permission from Pharmacy Workforce Center (PWC). https://pharmacymanpower.com/about.php

Various studies have called attention to warning signs of a tightening pharmacist employment market.53-56 These data identify that there is a greater supply of pharmacists than available positions in a number of states. Prospective students concerned about employment stability and compensation may be attracted to higher demand careers. Thus, the focus of the academy should be recalibrated towards advocating for increased opportunities for graduates as opposed to maintaining enrollment, which might produce graduates who are left with meager employment opportunities.

While workforce data are available, there are no comprehensive or coordinated efforts regarding pharmacy workforce planning.51 In 2010, the American Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ASHP) and American Pharmacist Association (APhA) presented a joint discussion paper examining pharmacy education expansion and the quality of pharmacy graduates. One of the key recommendations presented was the need for a stakeholders’ conference on workforce planning, establishment of a workforce needs assessment, and response to those needs.57 In 2012, student delegates of the American Pharmacists Association-Academy of Student Pharmacists (APhA-ASP) approved a resolution entitled, “Creation, Expansion, or Reductions of Schools and Colleges of Pharmacy Relative to Pharmacist Demand” This resolution urged pharmacy educators to evaluate pharmacist demand before enacting on the creation, expansion, or reduction of pharmacy programs.57 However, there were no robust responses to these recommendations partly because pharmacy education is not exempt from the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, which specifically prohibits restraint of competition. Currently, free market economic forces govern pharmacist supply and demand.

The expansion of pharmacy programs and enrollment will lead to prolonged negative effects on the profession.

With a rapid increase in class size over the past decade coupled with a decrease in applications, programs are competing for a limited pool of the best students. During the 1960’s and 1970’s, there was a dramatic increase in the number of law schools. During the Great Recession (December 2007 – June 2009), a downward spiral began which resulted in a decrease in the quantity and quality of applicants and dwindling employment opportunities for graduates. These conditions subsequently led to high unemployment rates for attorneys.58 More than 10 years later, this situation has not improved. Several law schools have closed, merged, or are at risk of closing.59 The experience of law education should serve as a bellwether, indicating that an unchecked pharmacy school enrollment coupled with a dampening of pharmacy employment opportunities would result in a pharmacist supply that would outpace employment demand. This situation could lead to a more serious decline in pharmacy applications and enrollment, similar to that experienced by law schools.

There are lessons to be learned from the approaches taken by law schools in response to decreasing student enrollments. In order to stem the tide of falling enrollment, law schools offered significant rebates and scholarships to entice students to enroll in their programs. The New York Times reported that nearly 80% of schools offered such rebates, which eventually fueled a bidding war between schools and brought in some students who were not passionate about the practice of law.60-63 Such tuition discounting across all institutions eventually led to enrolling students who had lower Law School Admissions Test scores and lower undergraduate grades, thus raising concerns about whether these students would be able to pass the mandatory state bar licensing examinations.64 The tuition discounting practice also contributed to a negative revenue cycle, leading to the closure of several schools.59,65,66 In the end, the approach that had been adopted to address falling enrollment eventually exacerbated the underlying problem and led to the closure of several schools. In an effort to address this problem, law schools have smaller class sizes and implemented a curriculum shift by offering undergraduate and graduate legal studies for those students who do not need a law degree (eg, certificates and bachelor of science and master of science degrees in contract, employment, and health law).67

High pharmacy education costs and increasing student debt forecasts long-term adverse effects to pharmacy education and the profession.

Fifty-seven percent of Americans believe that higher education does not provide a good value for the money that is spent to obtain a degree.68 Taylor and colleagues found that financial concerns were the primary obstacle to high school graduates pursuing a college education, especially since 60% of undergraduate students borrowed money to pay for educational costs.68,69 The New England Journal of Medicine reported that students in health professions programs graduate with significant ratios of debt to average annual income. Of the nine professions examined, pharmacy ranked third in ratio of debt to average annual income, behind veterinary medicine and optometry.70 The authors of the study raised the specter of a pharmacy education bubble, and concluded that the high cost of health professions education is not sustainable if student debt continues to accrue at such alarming rates.

Emerging student indebtedness concerns are valid given the cost of a pharmacy degree. A 2014 analysis found that the cost of pharmacy education had increased by 54% over the preceding eight years.71 Cain and colleagues reported that the rate of increase for average pharmacy student debt surpassed the rate of salary increase (23% vs 6%) from 2008-2012, which decreased effective salary.71 Since Cain’s 2014 report, the Graduating Pharmacy Student Survey, reported an average pharmacy student debt of $144,718 in 2014 and an average debt of $163,494 in 2017, which was a 13% increase over three years (2014-2017).37,72 These data identify a genuine concern that increased pharmacy student debt may negatively impact the number of students applying to pharmacy programs and the economic well-being of the next generation of pharmacist graduates is at stake.

Strategic and sustainable planning is needed urgently.

While there is a push to maintain or increase pharmacy enrollment, quantifying this enrollment need requires consideration of many factors including health care reform, growth in prescription rates affected by the aging population, and the overall health of the economy.73,74 There are no comprehensive projection models that include all of these aforementioned factors, along with the cost of pharmacy education, student indebtedness, and the latest supply data to estimate the balance of workforce levels. Consider too, that Knapp and Schommer pointed out that pharmacy administrators, educators, and other stakeholders need to use data projections and trends to identify actions to lead the profession forward during uncertain times.75

Multiple actions are needed to expand the pharmacist role in an integrated health care system. For example, continual improvements to pharmacy training will be needed, especially the development of interprofessional and team-based education to help students learn and practice team-based care. There are community pharmacy business models that could help pharmacists expand their roles within the health care system. These new emerging models in community pharmacies use technologies like barcode scanning, e-prescribing, and robotics. In addition, expanded technician roles, specialty care services, and new patient care models are other examples of services and models that would allow the pharmacists’ roles to be enhanced in patient care. In addition, health profession and pharmacy practice acts should be updated to reflect new roles for health professionals and team-based care. Payment should be aligned to not only support new pharmacist services, but also to provide sufficient payment for those services and evidence of cost-effectiveness for the payers of those services. Additional discussions should take place regarding bundling pharmacists’ services. Pharmacists’ skills for coordinating medications throughout the whole episode of care could improve the quality of care and reduce health care costs. Finally, efforts should be made to educate health consumers’ regarding pharmacists and their role in health care.79

Equally important is the consideration of strategic approaches to create a thoughtful plan that allows pharmacy education and profession to thrive during these challenging times. Changes that are focused only on enrollment can cause serious and sustained long-term effects that will continue to degrade academic and programmatic quality. While taking aggressive action to prevent further declines in enrollment may support immediate financial needs, such approaches will eventually come at the cost of competent graduates who need to be prepared to become successful licensed practitioners.

Strategic and sustainable decisions are required in such turbulent times to protect pharmacy institutions, the academy, the profession, and most importantly, the community. Holford presents an analysis of the different business models employed by various schools, which shows that most schools rely on enrollment with associated tuition as a revenue source, ie, the value-added education model. This model works best during times of high-quality student supply and strong application demand.76

Pharmacy educational institutions need to consider ways to optimize resources and increase revenue streams. One approach involves shifting the focus towards optimizing resources for more efficient delivery of pharmacy education. For example, Chisholm-Burns suggested reforming the delivery of pharmacy education by sharing resources among pharmacy schools and health care systems, using content experts to offer “master lectures” or online content on a regional or national basis, which would reduce content development expenditures (but not necessarily reduce content delivery expenditures).77 Shared faculty appointments with health care systems or organizations would aid in reducing personnel expenditures. Another approach focuses on exploiting other revenue streams to overcome the decreases in tuition revenue resulting from lower enrollments (ie, add another business model to the enterprise).76 This might be accomplished through commercial endeavors with the pharmaceutical industry, managed care organizations, and traditional and non-traditional research funding (ie, the solution shop research business model).76 Another potential revenue stream is reimbursement of clinical faculty services provided to the health care practice site. Qualifying for these reimbursements may be dependent on provider status, but a model similar to that used in medical practice groups could be implemented. The viability and applicability of these approaches depend on the educational and research microenvironment of the school and macroenvironments of the regional health care system and pharmaceutical industry.

Importantly, multiple stakeholders must collaborate and work together to create a strategic plan for managing declining enrollment in pharmacy schools. Stakeholders would include experts in workforce planning, professional organizations, state and national pharmacy boards, the academy, professionals from the community, health care systems and institutions, industry, administrators from academic and health care settings, faculty, students, and patients. As an example, workforce planning could provide guidance for strategic planning.78,79 Willie and colleagues offer a framework for health professions workforce planning at a national health care level.79 In 2013, the United Kingdom undertook strategic workforce planning specific to pharmacy. The resulting recommendations included reconfiguring the programmatic structure to include two educational paths, one leading to “a general science (non-professional) qualification” and another leading to licensure.78 A recommendation to actively regulate and cap pharmacy enrollment was not implemented.78

Pharmacy programs should not undertake aggressive actions to address decreasing enrollment that may lead to short-term gains but ultimately to long-term failures. Instead, schools should adopt a long-term strategic and sustainable plan that is in line with both the scope of the profession and the demands of the community. The only responsible solution to enrollment decline that secures the pharmacy profession for future generations is a proactive, strategic approach that safeguards the quality of pharmacy professionals and their role in addressing the needs of patients and communities.

CONCLUSION

Although the original ALFP debate at the 2017 AACP INfluence meeting was structured to contrast an aggressive vs strategic approach to the enrollment crisis, the identified points of this paper are more representative of an analysis of the challenges involved in managing pharmacy school enrollment, maintaining the financial viability of the pharmacy educational enterprise, and determining future directions for the profession. Many ideas addressing pharmacist capacity as discussed by Knapp and Schommer are still relevant today.75 Deliberate recognition and action on some discussion points has already commenced (refer to the AACP’s strategic plan).23 Pharmacy schools may identify one or more discussion points in this paper that are most relevant to their operation as governed by their institutional mission and values, as well as local and regional environmental factors.

Pharmacy educators are responsible for producing student pharmacists who are prepared for contemporary pharmacy practice as well as evolving opportunities within the profession. Pharmacy schools produce practitioners who can function effectively as a member of an interprofessional health care team, a direct patient care provider, and most importantly, a transformative agent of innovation and change within the profession. These challenges also present opportunities to apply adaptive leadership approaches, which involve thoughtful, strategic planning and action.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are most grateful to Charles T. Taylor, PharmD, and Joseph R. Ofosu, PharmD, for their mentorship and guidance throughout the yearlong Academic Leadership Fellowships Program and debate preparations, and to Jonathan Wolfson, author of The Great Debate (www.greatedebate.net), for his guidance and coaching on the fine points of debate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Report to Congress: the pharmacist workforce: a study of the supply and demand for pharmacists. Rockville, MD: Bureau of Health Professions, Health Resources and Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services; 2000.

- 2.Walton SM, Mott DA, Knapp KK, Fisher G. Association between increased number of US pharmacy graduates and pharmacist counts by state 2000-2009. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;75(4) doi: 10.5688/ajpe75476. Article 76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The adequacy of pharmacist supply: 2004 to 2030. 2008. https://web.archive.org/web/20161020133640/ttp://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/pharmsupply20042030.pdf . Accessed December 30, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health workforce projections: pharmacists. 2012. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bhw/nchwa/projections/pharmacists.pdf

- 5.Occupational outlook handbook: pharmacists. 2017. http://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/pharmacists.htm . Accessed November 15, 2017.

- 6.Occupational outlook handbook. 2017. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/ . Accessed November 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.PharmCAS end of year report 2014-2015. Pharmacy College Application Service. 2015.

- 8. Adams JL. Update on AACP application services and recruitment. Paper presented at: AACP Annual Meeting; July 17, 2017; Nashville, Tennesee.

- 9.Medical provider for pharmacy professionals - step by step. Washington Pharmacy. 2016;59(4) [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rietz S, Rochon J, Woolf R. Washington state pharmacist billing for care services: successful collaboration among provider associations, health systems, and health plans. American Society of Health-System Pharmacist Midyear Clinical Meeting December 2016; Las Vegas, NV.

- 11.Danielson J. Washington area: 2018. Personal observations of an informal survey of the Seattle. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor JN, Taylor DA, Nguyen NT. The pharmacy student population: applications received 2014-15, degrees conferred 2014-15, fall 2015 enrollments. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(6):S3. doi: 10.5688/ajpe806S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Total enrollment by U.S. medical school and sex, 2013-2014 through 2017-2018. In: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2017.

- 14.Amid calls for a more highly educated RN workforce, new AACN data confirm enrollment surge in schools of nursing. 2015. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20150309006264/en/Calls-Highly-Educated-RN-Workforce-New-AACN . Accessed December 18, 2017.

- 15.Auerbach AI, Buerhau PI, Staiger DO. How fast will the registered nurse workforce grow through 2030? Projections in nine regions of the country. Nursing Outlook. 2017;65(1):116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. 2016-2017 survey of advanced dental education. http://www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/data-center/dental-education. Accessed December 18, 2017.

- 17.Norman J. Americans rate healthcare providers high on honesty, ethics. Gallup News. 2016 (December). http://news.gallup.com/poll/200057/americans-rate-healthcare-providers-high-honesty-ethics.aspx. Accessed November 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones J, Saad L. Gallup poll social series: lifestyle. 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Honesty/Ethics in professions: gallup historical trends. In: Gallup News; 2017.

- 20.Marotta R. Pharmacists Remain Among Most Trusted Professions. Pharmacy Times. December 21, 2016; http://www.pharmacytimes.com/news/pharmacists-remain-among-most-trusted-professions. Accessed November 30, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanicak A, Mohorn PL, Monterroyo P, Furgiuele G, Waddington L, Bookstaver PB. Public perception of pharmacists: film and television portrayals from 1970 to 2013. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2015;55:578–586. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2015.15028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.NARAL. Ad campaign: "Who invited the pharmacist? 2005. http://archive.altweeklies.com/files/NARAL/055-101PharmAd_10x6.pdf . Accessed November 15, 2017.

- 23.Strategic plan 2016–2019: mission driven priorities. https://www.aacp.org/sites/default/files/2017-11/strategicplan-Sept17.pdf . Accessed November 30, 2017.

- 24.Auter Z. College Students Look to Social Network for Advice on Major. 2017. http://news.gallup.com/poll/219854/college-students-look-social-network-advice-major.aspx Accessed May 17, 2018.

- 25.Parker-Pope T. How to be happy. New York Times. 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/guides/well/how-to-be-happy . Accessed November 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams JL, Law A. Strategic plan priority 1: enriching the applicant pipeline. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(1):S1. doi: 10.5688/ajpe811S1. http://www.ajpe.org/doi/abs/10.5688/ajpe811S1 . Accessed November 30, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pittaoulis M. Getting through school: a study of how students select their college majors and plan for the future. [doctoral dissertation]. Temple University; 2012.

- 28.Wiswall M, Zafar B. Determinants of college major choice: identification using an information experiment. The Review of Economic Studies. 2015;82(2):791–824. https://academic.oup.com/restud/article/82/2/791/1585624 . Accessed November 30, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hanna L-A, Askin F, Hall M. First year pharmacy students’ views on their chosen professional career. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(9) doi: 10.5688/ajpe809150. Article 150. http://www.ajpe.org/doi/full/10.5688/ajpe809150. Accessed December 18, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keshishian F. Factors influencing pharmacy students' choice of major and its relationship to anticipatory socialization. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(4) doi: 10.5688/aj740475. Article 75. http://www.ajpe.org/doi/full/10.5688/aj740475. Accessed December 18, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keshishian F, Brocavich JM, Boone RT, Pal S. Motivating factors influencing college students’ choice of academic major. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(3) doi: 10.5688/aj740346. Article 46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Anderson C. Recruiting the right students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe81342. Article 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon VN. The undecided college student: an academic and career advising challenge. 3rd ed. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher, LTD; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 34.The condition of college and career readiness, national report. ACT, Inc; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Venit E, Litzenberger A, Cuttler G, Studewell J, Koppenheffer M, Shams P. How late is too late? Myths and facts about the consequences of switching college majors. EAB Student Success Collaborative; 2016.

- 36.Mangan K. Can ‘guided pathways’ keep students from being overwhelmed by choice? Chron of High Educ. April 25, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Graduating student survey: 2017 national summary report. Alexandria, VA: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; 2017.

- 38. Profile of pharmacy students 2016, introduction. Alexandria, VA: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; November 30, 2017.

- 39. Fall 2003 profile of pharmacy students, introduction Alexandria, VA: American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy; 2003.

- 40.Seltzer R. Diminishing returns for tuition discounting. Inside Higher Ed. 2017:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seltzer R. Kentucky’s need-based aid gamble. Inside Higher Ed. 2017:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Boje K Personal observations. 2017.

- 43.Douglas-Gabriel D. This trend could destablize some small private colleges if it continues. The Washington Post. May 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Selingo JJ. Higher education’s macy’s problem. The Washington Post. May 18, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cox WC, McLaughlin JE, Singer D, Lewis M, Dinkins MM. Development and assessment of the multiple mini-interview in a school of pharmacy admissions model. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(4) doi: 10.5688/ajpe79453. Article 53. . Accessed November 30, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heldenbrand SD, Flowers SK, Bordelon BJ, et al. Multiple mini-interview performance predicts academic difficulty in the pharmd curriculum. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;80(2) doi: 10.5688/ajpe80227. . Accessed November 30, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wall AL, Adams JL, Aljets A, et al. Correction to: "White Paper on Pharmacy Admissions: Developing a Diverse Work Force to Meet the Health-Care Needs of an Increasingly Diverse Society. Am J Pharm Educ. 2016;8(3) doi: 10.5688/ajpe80354. Article 54. http://www.ajpe.org/doi/10.5688/ajpe80354. Accessed November 30, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wall A, Aljets A, Ellis S, et al. White Paper on Pharmacy Admissions: Developing a Diverse Work Force to Meet the Health-Care Needs of an Increasingly Diverse Society. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(7) doi: 10.5688/ajpe797S7. Article S7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.ACTFL proficiency guidelines. 2012. https://www.actfl.org/publications/guidelines-and-manuals/actfl-proficiency-guidelines-2012 Accessed November 30, 2017.

- 50. Oral proficiency assessments (Including OPI & OPIC). https://www.actfl.org/professional-development/assessments-the-actfl-testing-office/oral-proficiency-assessments-including-opi-opic. November 30, 2017.

- 51.About: pharmacist demand indicator (PDI) https://pharmacymanpower.com/about.php . Accessed May 20, 2018, 2017.

- 52.Pharmacist demand indicator: time based trends. https://pharmacymanpower.com/trends.php . Accessed May 20, 2018.

- 53.Brown D. From shortage to surplus: the hazards of uncontrolled academic growth. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10) doi: 10.5688/aj7410185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brown DL. A looming joblessness crisis for new pharmacy graduates and the implications it holds for the academy. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(5):90. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77590. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3687123/ . Accessed December 15, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hulisz D, Brown DL. The future of pharmacy jobs -- will it be feast or famine? Medscape Pharmacists. 2014. (April 15). https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/823365. Accessed November 30, 2017.

- 56.Lowery M. Signs of a weakening pharmacist job market. Drug Topics. June 10, 2016. http://drugtopics.modernmedicine.com/drug-topics/news/signs-weakening-pharmacist-job-market. Accessed November 30, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mount Prospect, IL: National Association of Boards of Pharmacy; 2010. APhA and ASHP release white paper exploring concerns about expansion of pharmacy education. [press release] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Koba M. Courtroom drama: too many lawyers, too few jobs. March 21, 2013; www.cnbc.com/id/100569350. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 59.Russell-Kraft S. Whittier law school closing: the first of many? Bloomberg Big Law Business. April 21, 2017; https://biglawbusiness.com/whittier-law-school-closing-the-first-of-many/. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 60.Scheiber N. An expensive law degree, and no place to use it. New York Times. 2016 https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/19/business/dealbook/an-expensive-law-degree-and-no-place-to-use-it.html . Accessed December 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olson E. Cincinnati law dean is put on leave after proposing ways to cut budget. The New York Times. March 30, 2017; https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/30/business/dealbook/cincinnati-law-school-dean-budget-cuts.html. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 62.Segal D. Law students lose the grant game as schools win. The New York Times. April 30, 2011; http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/01/business/law-school-grants.html. Accessed December 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Olson E. Law school is buyers’ market, with top students in demand. The New York Times. December 1, 2014; https://dealbook.nytimes.com/2014/12/01/law-school-becomes-buyers-market-as-competition-for-best-students-increases. Accessed December 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward SF. LSAT scores at high-risk schools getting worse, according to analysis by law school reform group. ABA Journal. February 2, 2017; http://www.abajournal.com/news/article/lsat_scores_at_high_risk_schools_getting_worse_says_paper_in_favor_of_tight. Accessed December 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Olson E. For-Profit charlotte school of law closes. The New York Times. August 15, 2017; https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/15/business/dealbook/for-profit-charlotte-school-of-law-closes.html. Accessed December 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Olson E. Whittier law school says it will shut down. The New York Times. April 19, 2017; https://www.nytimes.com/2017/04/19/business/dealbook/whittier-law-school-to-close.html. Accessed. December 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Baker L. Lawyers are back: Law schools retrench. Oregon Business. 2017 https://www.oregonbusiness.com/article/professional-services/item/17724-lawyers-are-back-the-future-law-schools-retrench. Accessed May 20, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Taylor P, Parker K, Fry R, et al. Is college worth it? College presidents, public assess value, quality and mission of higher education. May 16, 2011; http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2011/05/higher-ed-report.pdf. Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 69.Selingo JJ. The value equation. Measuring and communicating the return on investment of a college degree. 2015. http://results.chronicle.com/LP=1006 . Accessed December 15, 2017.

- 70.Asch DA, Nicholson S, Vujicic M. Are we in a medical education bubble market? N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1973–1975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1310778. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1310778 . Accessed December 15, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cain J, Campbell T, Congdon HB, et al. Pharmacy student debt and return on investment of a pharmacy education. Am J Pharm Educ. 2014;78(1) doi: 10.5688/ajpe7815. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3930253/ . Accessed December 15, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.American Association of College of Pharmacy graduating student survey. 2014. national summary report. Alexandria, VA: American Association of College of Pharmacy;2014.

- 73.Knapp KK, Cultice JM. New pharmacist supply projections: lower separation rates and increased graduates boost supply estimates. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2007;47(4):463–470. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2007.07003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Knapp KK, Shah BM, Barnett MJ. The pharmacist aggregate demand index to explain changing pharmacist demand over a ten-year period. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(10) doi: 10.5688/aj7410189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Knapp K, Schommer JC. Finding a path through times of change. Am J Pharm Educ. 2013;77(5) doi: 10.5688/ajpe77591. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3687124/ . Accessed December 15, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holdford DA. Understanding business models in pharmacy schools. Am J Pharm Educ. 2017;81(5):82. doi: 10.5688/ajpe81582. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5508081/ . Accessed December 15, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chisholm-Burns MA. A crisis is a really terrible thing to waste. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74(2) doi: 10.5688/aj740219. http://www.ajpe.org/doi/full/10.5688/aj740219 . Accessed December 15, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Covvey JR, Cohron PP, Mullen AB. Examining pharmacy workforce issues in the United States and the United Kingdom. Am J Pharm Educ. 2015;79(2) doi: 10.5688/ajpe79217. Article 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Willis G, Cave S, Kunc M. Strategic workforce planning in healthcare: a multi-methodology approach. Euro J of Operational Res. 2018;267(1):250–263. [Google Scholar]