Abstract

BACKGROUND

Food antigens have been shown to participate in the etiopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but their clinical value in IBD is still unclear.

AIM

To analyze the levels of specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) and E (IgE) antibodies against food antigens in IBD patients and to determine their clinical value in the pathogenesis of IBD.

METHODS

We performed a retrospective study based on patients who visited the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between August 2016 and January 2018. A total of 137 IBD patients, including 40 patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and 97 patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), and 50 healthy controls (HCs), were recruited. Serum food-specific IgG antibodies were detected by semi-quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and serum food-specific IgE antibodies were measured by Western blot. The value of food-specific IgG antibodies was compared among different groups, and potent factors related to these antibodies were explored by binary logistic regression.

RESULTS

Food-specific IgG antibodies were detected in 57.5% of UC patients, in 90.72% of CD patients and in 42% of HCs. A significantly high prevalence and titer of food-specific IgG antibodies were observed in CD patients compared to UC patients and HCs. The number of IgG-positive foods was greater in CD and UC patients than in HCs (CD vs HCs, P = 0.000; UC vs HCs, P = 0.029). The top five food antigens that caused positive specific IgG antibodies in CD patients were tomato (80.68%), corn (69.32%), egg (63.64%), rice (61.36%), and soybean (46.59%). The foods that caused positive specific IgG antibodies in UC patients were egg (60.87%), corn (47.83%), tomato (47.83%), rice (26.09%), and soybean (21.74%). Significantly higher levels of total food-specific IgG were detected in IBD patients treated with anti-TNFα therapy compared to patients receiving steroids and immunosuppressants (anti-TNFα vs steroids, P = 0.000; anti-TNFα vs immunosuppressants, P = 0.000; anti-TNFα vs steroids + immunosuppressants, P = 0.003). A decrease in food-specific IgG levels was detected in IBD patients after receiving anti-TNFα therapy (P = 0.007). Patients who smoked and CD patients were prone to developing serum food-specific IgG antibodies [Smoke: OR (95%CI): 17.6 (1.91-162.26), P = 0.011; CD patients: OR (95%CI): 12.48 (3.45-45.09), P = 0.000]. There was no difference in the prevalence of food-specific IgE antibodies among CD patients (57.1%), UC patients (65.2%) and HCs (60%) (P = 0.831).

CONCLUSION

CD patients have a higher prevalence of food-specific IgG antibodies than UC patients and HCs. IBD patients are prone to rice, corn, tomato and soybean intolerance. Smoking may be a risk factor in the occurrence of food-specific IgG antibodies. Food-specific IgG antibodies may be a potential method in the diagnosis and management of food intolerance in IBD.

Keywords: Inflammatory bowel disease, Food-specific immunoglobulin G, Food intolerance

Core tip: Food antigens have been indicated to participate in the etiopathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. However, their value is disputable, as some studies found that food immunoglobulin G (IgG) and E (IgE) antibodies can be expressed in healthy individuals. This study analyzed the levels of specific IgG and IgE antibodies against food antigens in inflammatory bowel disease patients and found that Crohn’s disease patients not only have higher prevalence of food-specific IgG, but also intolerance against rice, corn, tomato and soybean.

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, which includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Increasing evidence indicates that IBD results from an abnormal mucosal immune system triggered by environmental factors[1,2].

Various environmental factors such as environmental pollution, smoking, stress and foods[3-6] are thought to induce or aggravate IBD. Of these factors, diet is considered to contribute to the course of IBD[7]. A multicenter case-control study in Japan found that sweets, fats, including monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids, soil, fish and shellfish were positively associated with IBD risk[8]. Another study showed that increased consumption of alcohol or red meat was associated with an increased probability of relapse in UC patients[9]. Two large prospective cohort studies in Japan and Europe verified that high consumption of n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids may aggravate IBD by altering the fatty acid composition of the cell membrane and immunomodulating leukotrienes and prostaglandins[10,11]. Studies have shown that food intolerance may be involved in this process[12]. Some food antigens are thought to be involved in the formation and development of human chronic intestinal inflammatory diseases in genetically susceptible patients[13,14].

Food allergy and food intolerance are two types of adverse reactions to food. Food allergy is typically mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies, which produce an immediate and sometimes life-threatening response, the most well-known being type 1 food allergy to peanuts or shellfish. The immune system mounts an attack against normally harmless food ingredients. In contrast, food intolerance is mediated by immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies, and the underlying mechanism may be the stimulation of neutrophils or other cells in the innate immune system, creating a complex clinical course. Food intolerance significantly contributes to IBD patients’ symptoms. The advantages of removing certain foods from the daily diet have been a focus in recent studies[15-17]. It is thought that classic food intolerance is caused by food allergies based on IgE-mediated antibody responses; however, immediate allergic reactions are rare in IBD[18,19]. Therefore, a delayed immune response mediated by IgG antibodies following exposure to a particular antigen may account for adverse food reactions in IBD[20]. However, this mechanism is debatable, as some studies found that food IgG antibodies can be expressed in healthy individuals[21-26]. The purpose of this study was to analyze the levels of IgG and IgE antibodies against food antigens in IBD patients and determine their clinical value in IBD pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

We performed a retrospective study using blood samples obtained from patients who visited the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between August 2016 and January 2018. According to the consensus on the diagnosis of IBD drawn up by European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization[27,28], each patient met the diagnostic criteria for CD or UC. We excluded patients who had been diagnosed with ischemic bowel disease, radiation enteritis, cardio-cerebral vascular diseases, infectious diseases, cancer or received surgery within 3 months. Healthy controls (HCs) were chosen from our Physical Examination Center to represent the general population. Finally, a total of 137 IBD patients, including 40 patients with UC and 97 patients with CD, and 50 HCs were enrolled in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. The Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University approved the study and the consent procedure.

Serum IgG/IgE assay

Serum IgG antibodies to 14 unique food antigens (chicken, beef, codfish, egg, crab, shrimp, milk, pork, rice, corn, mushroom, wheat, soybean and tomato) were assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Biomerica Inc., Irvine, CA, United States). The IgG concentration was classified into the following four grades: negative (Grade 0, less than 50 U/mL), mild sensitivity (Grade +1, 50-100 U/mL), moderate sensitivity (Grade +2, 100-200 U/mL) and high sensitivity (Grade +3, > 200 U/mL). IgE-specific antibodies to food allergens (chicken egg white, cow’s milk, peanut, beef, mutton, shrimp, crab, marine fish including gadus, lobster, scallop, and freshwater fish including trout, weever, carp) were examined by western blotting according to the manufacturer’s instructions (EUROIMMUN Medizinische Labordiagnostika AG, Germany). An IgE concentration less than 0.35 kU/L was considered negative. Levels of 0.35-3.5 kU/L, 3.5-17.5 kU/L and > 17.5 kU/L were classified as mild specific antibody concentration, moderate specific antibody concentration with obvious clinical symptoms, and high specific antibody concentration, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 21.0). Enumeration data were analyzed by the Chi-squared test. Continuous numerical variables were expressed as the mean ± SD. Comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t test or ANOVA test, as appropriate. Correlations among variables were analyzed by binary logistic regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 50 HCs, 40 UC patients and 97 CD patients are summarized in Table 1. The average age in the UC, CD and HC groups was similar, the mean disease course in the UC and CD group was similar. The percentage of rectum, left-sided and entire colon type in UC patients was 25%, 17.5%, and 57.5%, respectively; 76.29% of CD patients had ileal or ileal-colon lesions, and 30.93% of CD patients had undergone IBD-related surgery. In total, 61.86% of CD patients and 75% of UC patients were in the active stage. In addition, 61.86% of CD patients and 30% of UC patients received treatment with steroids, immuno-suppressive agents, or anti-TNFα; and 18.56% of CD patients received enteral nutrition.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of all subjects, n (%)

| Clinicopathological features | UC, n = 40 | CD, n = 97 | HCs, n = 50 |

| Male | 26 (65) | 69 (71.13) | 30 (60) |

| Female | 14 (35) | 28 (28.87) | 20 (40) |

| Age in yr, mean ± SD | 34.22 ± 12.50 | 33.51 ± 11.77 | 36.2 ± 10.73 |

| Duration of disease in yr, mean, 95%CI | 3.69 (2.12-4.86) | 2.80 (2.01-3.54) | / |

| Disease activity | |||

| Remission | 10 (25) | 37 (38.14) | / |

| Mild | 6 (15) | 36 (37.11) | / |

| Moderate | 17 (42.5) | 23 (23.71) | / |

| Severe | 7 (17.5) | 1 (1.04) | / |

| Age at diagnosis in yr | |||

| A1, ≤ 16 | / | 6 (6.19) | / |

| A2, 17-40 | / | 67 (69.07) | / |

| A3, > 40 | / | 24 (24.74) | / |

| Disease location | |||

| L1, terminal ileum | / | 41 (42.27) | / |

| L2, colon | / | 17 (17.53) | / |

| L3, ileocolon | / | 33 (34.02) | / |

| L1+L4 | / | 3 (3.09) | / |

| L3+L4 | / | 3 (3.09) | / |

| E1, rectum | 10 (25) | / | |

| E2, left-sided colon | 7 (17.5) | / | |

| E3, entire colon | 23 (57.5) | / | |

| Disease behaviour | |||

| B1, non-stricturing, non-penetrating | 58 (59.79) | / | |

| B2, stricturing | 32 (32.98) | / | |

| B3, penetrating | 6 (6.19) | / | |

| B2 + B3 | 1 (1.04) | / | |

| CDAI, mean ± SD | 153.96 ± 80.22 | ||

| Mayo, mean ± SD | 6.52 ± 3.24 | ||

| Smoker | 10 (25) | 8 (8.25) | / |

| Perianal diseases | 1 (2.5) | 5 (5.15) | / |

| Medications | |||

| 5-ASA | 32 (80) | 31 (31.96) | / |

| Sulfasalazine | 2 (5) | / | / |

| Steroids | 10 (25) | 9 (9.28) | / |

| Immunosuppressive agents | 2 (5) | 19 (19.59) | / |

| Anti-TNF | / | 32 (32.99) | / |

| Enteral nutrition | / | 18 (18.56) | |

| No meds | 4 (10) | / | / |

| Surgery, IBD-related | 2 (5) | 30 (30.93) | / |

E1, E2, E3: Disease location of UC using the Montreal Classification; A1, A2, A3: Age at diagnosis; L1, L2, L3: Disease location; B1, B2, B3, B2 + B3: Disease behavior of CD using the Montreal Classification; UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; HCs: Healthy controls; CDAI: Crohn’s Disease Activity Index; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

Proportion of serum food-specific IgG in UC and CD patients

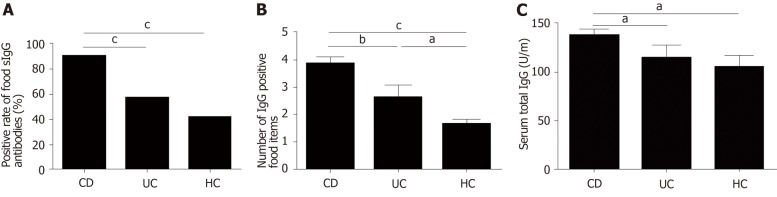

The positive rate of food-specific IgG in UC patients, CD patients and HCs was 57.5%, 90.72% and 42%, respectively. CD patients showed higher positive rate of food-specific IgG than HCs (P = 0.000). However, there was no significant difference between UC patients and HCs (P = 0.144) (Figure 1A). The number of IgG-positive food items was higher in UC and CD patients than in HCs (UC vs HCs, P = 0.029; CD vs HCs, P = 0.000; CD vs UC, P = 0.006) (Figure 1B). CD patients showed positive IgG against an average of 3.8 foods [range 1-8; 95% confidence interval (CI): 3.41-4.20], while UC patients and HCs showed positive IgG against an average of 2.56 foods (range 1-8; 95%CI: 1.73-3.39) and 1.57 foods (range 1-3; 95%CI 1.26–1.87), respectively. The average levels of total serum IgG in CD patients, UC patients and HCs were 138.6 ± 75.65, 115.6 ± 80.11, and 105.9 ± 52.3 U/mL, respectively. The average levels of total serum IgG in CD patients were significantly different from those in UC patients and HCs (CD vs UC, P = 0.03; CD vs HCs, P = 0.017), while there was no significant difference between UC patients and HCs (P = 0.554) (Figure 1C). The seropositive rate of moderate and high sensitivity was 39.13% in UC patients, 84.09% in CD patients and 71.43% in HCs, and the CD group had higher sensitivity to specific food allergens than the UC group (P = 0.000).

Figure 1.

High sensitivity to food antigens in inflammatory bowel disease patients. A: Positive rate of food-specific IgG antibodies in CD patients, UC patients and HCs. Statistics: Chi-squared test; B: The number of IgG-positive food items in CD patients, UC patients and HCs; C: Comparison of the total serum IgG levels in CD patients, UC patients and HCs. Statistics: ANOVA), aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; HCs: Healthy controls; ANOVA: One-way analysis of variance.

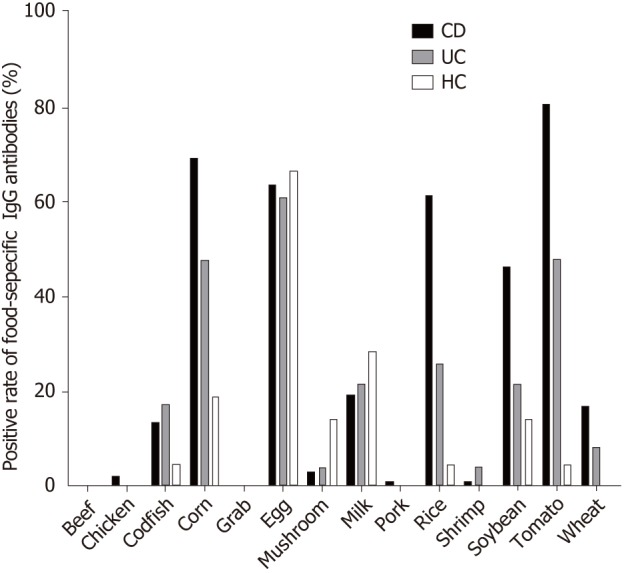

Distribution spectrum of food-specific IgG to 14 unique food allergens in UC and CD patients

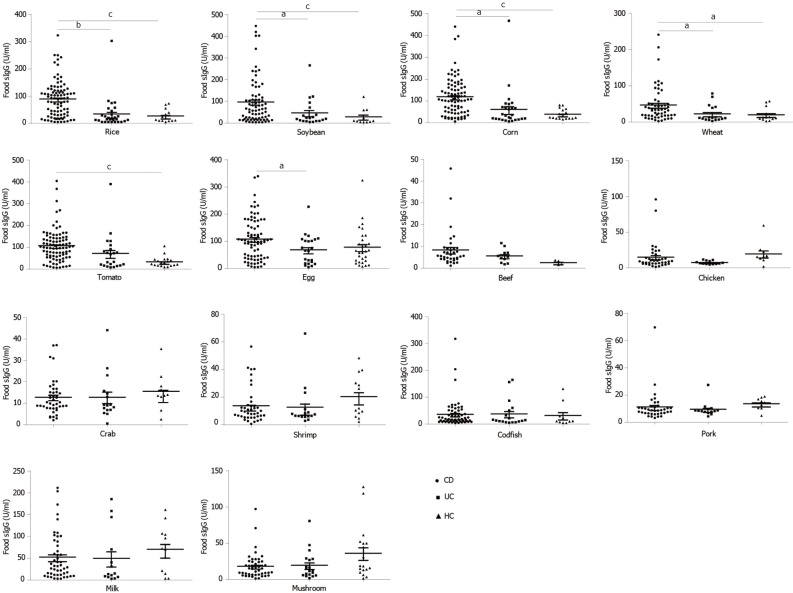

In CD patients, the top nine food allergens causing positive serum IgG were tomato (80.68%), corn (69.32%), egg (63.64%) rice (61.36%), soybean (46.59%), milk (19.32%), wheat (17.65%), codfish (13.64%), and mushroom (3.4%). In UC patients, the nine main food allergens causing positive serum IgG were egg (60.87%), corn (47.83%), tomato (47.83%), rice (26.09%), soybean (21.74%), milk (21.34%), codfish (17.39%), wheat (8.7%) and mushroom (4.35%). The food-specific IgG detected in HCs was due to egg (66.7%), milk (28.6%), corn (19%), soybean (14.3%), mushroom (14.3%), rice (4.8%), and tomato (4.8%) (Figure 2), similar to the findings in a previous report[29]. In the present study, CD patients were more sensitive to tomato, corn, rice, soybean, wheat and codfish, while UC patients were more sensitive to tomato, corn and rice (Table 2). CD patients had significantly higher levels of food-specific IgG than UC patients and HCs against rice (CD vs HCs, P = 0.000; CD vs UC, P = 0.01), soybean (CD vs HCs, P = 0.001; CD vs UC, P = 0.015), corn (CD vs HCs, P = 0.000; CD vs UC, P = 0.013), wheat (CD vs HCs, P = 0.012; CD vs UC, P = 0.016), tomato (CD vs HCs, P = 0.001; CD vs UC, P = 0.201), and egg (CD vs HCs, P = 0.054; CD vs UC, P = 0.021). No significant differences were observed for beef (P = 0.148), chicken (P = 0.429), crab (P = 0.385), shrimp (P = 0.164), codfish (P = 0.812), pork (P = 0.496), milk (P = 0.452) or mushroom (P = 0.122) specific IgG compared with HCs. No significant differences in food-specific IgG to 14 dietary antigens were observed between UC patients and HCs (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Distribution of positive IgG to food allergens in CD patients, UC patients and HCs. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; HCs: Healthy controls.

Table 2.

Percentage of positive food-specific IgG antibodies against 14 food items in ulcerative colitis patients, Crohn’s disease patients, and healthy controls

| CD | UC | HCs | |

| Beef | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chicken | 2.27 | 0 | 0 |

| Codfish | 13.64a | 17.39 | 4.8 |

| Corn | 69.32c | 47.83a | 19 |

| Crab | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Egg | 63.64 | 60.87 | 66.7 |

| Mushroom | 3.4 | 4.35 | 14.3 |

| Milk | 19.32 | 21.34 | 28.6 |

| Pork | 1.14 | 0 | 0 |

| Rice | 61.36c | 26.09a | 4.8 |

| Shrimp | 1.14 | 4.21 | 0 |

| Soybean | 46.59c | 21.74 | 14.3 |

| Tomato | 80.68c | 47.83c | 4.8 |

| Wheat | 17.05b | 8.7 | 0 |

Statistics: Chi-squared test

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; HCs: Healthy controls.

Figure 3.

The levels of food-specific IgG against 14 common daily foods in CD patients, UC patients and HCs. Statistics: ANOVA, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; HCs: Healthy controls; ANOVA: One-way analysis of variance.

Relationship between food-specific IgG and disease location

The disease location of CD and UC patients was divided into subgroups according to the Montreal classification. The positive rates of food-specific IgG among subgroups of UC or CD patients were not significantly different.

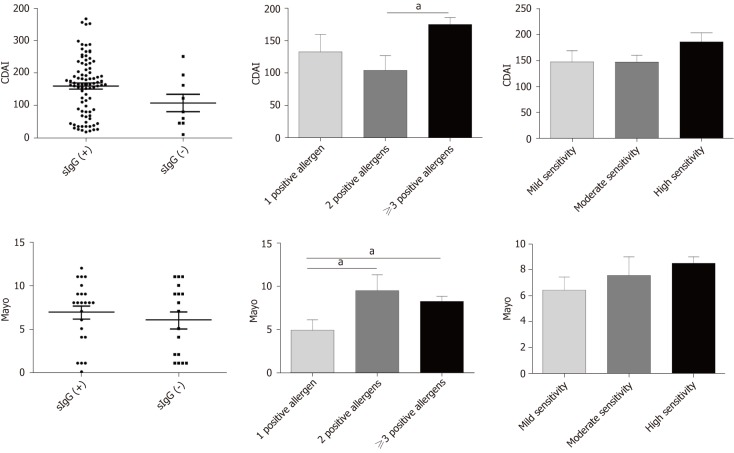

Association between food-specific IgG and disease activity

The Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) was used to evaluate CD patients’ disease activity, and the Mayo score was used to assess UC patients’ disease activity. Both CD and UC patients were divided into positive and negative food-specific IgG subgroups, with no marked statistical difference (CDAI: Food-specific IgG+ vs food-specific IgG-, P = 0.27; Mayo: food-specific IgG+ vs food-specific IgG-, P = 0.58). It was found that the group with more than three positive allergens had a higher CDAI score compared with the group with two positive allergens (P = 0.033). The Mayo score in the group with multiple positive allergens was higher than that in the group with a single positive allergen (2 positive vs 1 positive, P = 0.024; ≥ 3 positive vs 1 positive, P = 0.046). We also divided CD and UC patients into three subgroups according to the degree of seropositivity. There were no significant differences among the three subgroups (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Association between food-specific IgG antibodies and disease activity. Data are shown as mean ± SD by ANOVA, aP < 0.05. ; ANOVA: One-way analysis of variance.

Relationship between food-specific IgG and clinical characteristics

The food-specific IgG-positive group had higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as leukocyte count, platelet count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) compared with the food-specific IgG-negative group, although there was no significant difference between the groups (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of laboratory results between positive and negative food-specific IgG subgroups in inflammatory bowel disease patients

| Laboratory results |

sIgG (+) |

sIgG (-) |

P-value |

| n = 111 | n = 26 | ||

| WBC, × 109/L | 6.56 ± 2.57 | 6.26 ± 2.17 | 0.62 |

| Hb, g/L | 121.59 ± 23.72 | 123.71 ± 29.27 | 0.77 |

| HCT | 38.45 ± 6.38 | 37.36 ± 6.14 | 0.83 |

| PLT, × 109/L | 280.75 ± 110.31 | 233.65 ± 86.34 | 0.13 |

| CRP, mg/L | 17.27 ± 6.64 | 11.17 ± 4.84 | 0.13 |

| ESR, mm/H | 21.49 ± 19.88 | 20.12 ± 19.40 | 0.64 |

| ALB, g/L | 37.08 ± 5.24 | 40.21 ± 5.23 | 0.16 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD: Student’s t test. No statistical significance (P > 0.05). WBC: White blood cell; Hb: Hemoglobin; PLT: Platelet; CRP: C-Reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate; HCT: Hematocrit; ALB: Albumin.

The association between demographic and other factors with food-specific IgG is shown in Table 4. Subjects who smoked were prone to developing serum food-related IgG antibodies [OR (95%CI): 17.6 (1.91-162.26); P = 0.011]. CD patients were more predisposed to food intolerance than UC patients [OR (95%CI): 12.48 (3.45-45.09); P = 0.000] (Table 4).

Table 4.

Correlation between food-specific IgG and clinical parameters

| Parameter | Odds ratio | 95%CI | P-value |

| Disease type, UC/CD | 12.48 | 3.45-45.09 | 0.000c |

| Gender, male/female | 2.07 | 0.62-6.88 | 0.237 |

| Age, < 40 yr/≥ 40 yr | 0.44 | 0.14-1.41 | 0.167 |

| Smoker | 17.6 | 1.91-162.26 | 0.011a |

UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; 95%CI: 95% Confidence interval. Statistics: Binary logistic regression,

P < 0.05,

P < 0.001. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease

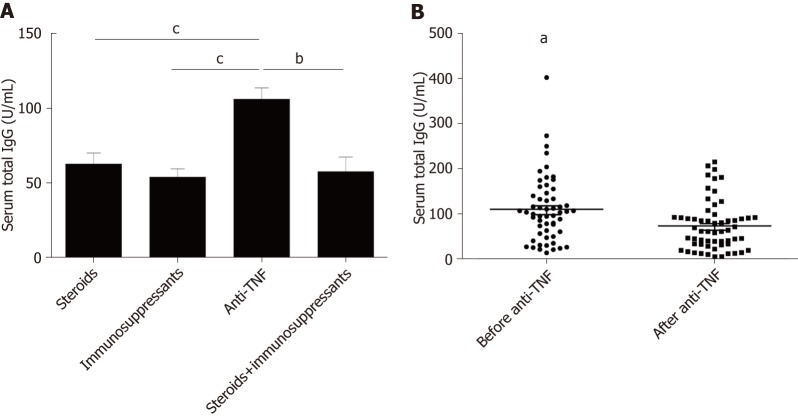

Anti-TNFα was an effective biological agent in IBD patients. Higher total food IgG levels were found in patients treated with anti-TNFα compared to patients treated with steroids or immunosuppressants (anti-TNFα vs steroids, P = 0.013; anti-TNFα vs immunosuppressants, P = 0.000) (Figure 5A). However, we found a decrease in food-specific IgG levels in IBD patients after introducing anti-TNFα (before anti-TNFα vs after anti-TNFα, P = 0.009) (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Serum food-specific IgG concentrations in patients treated with different medications and comparison of food-specific IgGs for inflammatory bowel disease patients before and after Infliximab treatment. A: Serum food-specific IgG concentrations in patients treated with different medications. Statistics: ANOVA; B: Comparison of Food-specific IgGs for inflammatory bowel disease patients before and after Infliximab treatment. Statistics: paired-samples t test, aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01, cP < 0.001. ANOVA: One-way analysis of variance.

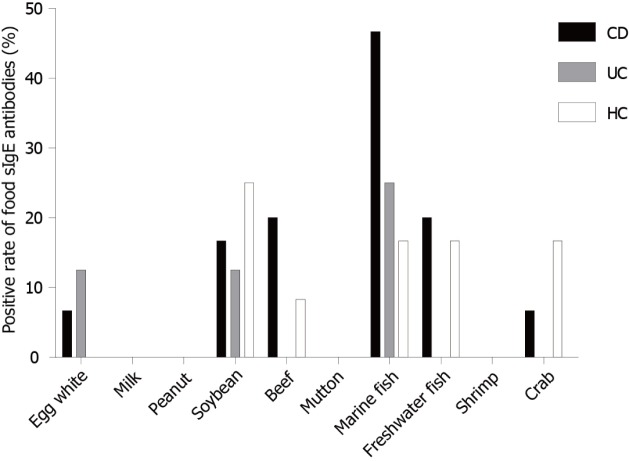

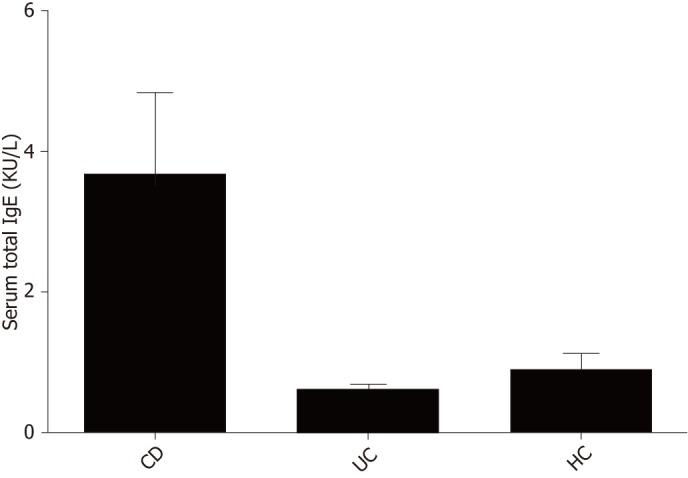

Prevalence of serum specific IgE to antigens

It was shown that 65.2% of CD patients, 57.1% of UC patients and 60% of HCs had specific IgE antibodies; and 62.5%, 12.5%, and 25% of UC patients and 26.67%, 30%, and 43.33% of CD patients were sensitive to one, two, or three or more allergens, respectively. These values were 25%, 33.33%, and 41.67% in HCs. The seropositive rate of moderate and high sensitivity was 50% in UC patients, 56.67% in CD patients and 71.43% in HCs. The differences among the three groups in the occurrence of IgE positivity were not statistically significant (P = 0.831). The average levels of total serum IgE in subjects with CD, UC and HCs were 3.68 ± 6.62, 0.61 ± 0.17, and 0.90 ± 0.68 kU/L, respectively. There was no significant difference among CD patients, UC patients and HCs (CD vs HCs, P = 0.202; UC vs HCs, P = 0.933; CD vs UC, P = 0.316) (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Comparison of total serum IgE levels between CD patients, UC patients and HCs. Statistics: ANOVA. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; HCs: Healthy controls; ANOVA: One-way analysis of variance.

Proportion of serum food-specific IgE antibodies

In this study, 16.67% of HCs had food-specific IgE against marine fish in contrast to 46.67% of CD patients and 25% of UC patients. In addition, 20% of CD patients had IgE to beef in contrast to only 8.33% of HCs. This was even more pronounced in terms of IgE antibodies to egg white, with 6.67% of CD patients and 12.5% of UC patients showing IgE antibodies, while HCs showed no egg white IgE antibodies (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Distribution of positive IgE to food allergens in CD patients, UC patients and HCs. UC: Ulcerative colitis; CD: Crohn’s disease; HCs: Healthy controls.

DISCUSSION

Immune tolerance to exogenous antigens, including commensal bacteria and food proteins is a pivotal regulation mechanism for maintaining intestinal homeostasis. A breakdown in immune tolerance to exogenous antigens is considered to play a role in the initiation and development of chronic inflammation in IBD[30]. Some IBD patients have shown an improvement in symptoms following exclusion diets[31-33]. Previous studies have investigated the potential role of serum IgG/IgE in food intolerance/allergy[34,35], and a thorough study of exclusion diet according to food IgG/IgE tests has been conducted[36,37]. However, the reliability and clinical practicability of food-specific IgG/IgE detection remain controversial, although it is a potential method for the diagnosis of food intolerance/allergy.

In the present study, CD patients had high levels of serum food-specific IgG antibodies compared to UC patients and HCs. Most (90.72%) of the CD patients had higher levels of IgG antibodies, similar to previous findings[17]. Both CD and UC patients also had more IgG-positive food items and higher sensitivity. Similar results were reported by Cai et al[17], who found that IBD patients were sensitive to multiple food antigens. Food allergy was once thought to play a part in the progression of IBD[38]. However, food-specific IgE was not found in CD patients in the studies by Huber et al[39] and Bartůnková et al[40]. In the present study, 57.1% of UC patients, 65.2% of CD patients, and 60% of HCs had detectable specific IgE to different food antigens, but these values were not statistically significant.

A study showed that the common food allergens that caused positive IgG in CD patients were egg (73.3%), rice (56.7%), corn (56.7%), tomato (46.7%) and soybean (43.3%). In addition, the frequent food allergens in UC patients were egg (81.0%), rice (14.3%), corn (14.3%), tomato (9.5%) and milk (9.5%). The corresponding food allergens in HCs were egg (69.3%), milk (14.8%), and crab (14.8%)[17]. In the present study, the most common food-specific IgG antibodies detected in CD patients were against tomato in 80.68% of patients, followed by corn in 69.32%, egg in 63.64%, rice in 61.36%, soybean in 46.59%, milk in 19.32%, wheat in 17.65%, and codfish in 13.64% of patients. The most common food-specific IgG antibodies detected in UC patients were egg (60.87%), corn (47.83%), tomato (47.83%), rice (26.09%), soybean (21.74%), milk (21.34%), codfish (17.39%), and wheat (8.7%). The most common food-specific IgG antibodies detected in HCs were egg (66.7%), milk (28.6%), and corn (19%). Collectively, these data suggest that both IBD patients and HCs showed a high level of egg-specific IgG antibodies, while IBD patients may be prone to rice, corn, tomato and soybean intolerance. Foods such as rice, wheat, corn, soybean, and tomato are traditional products and some of the most commonly used ingredients in China. As such, most Chinese people are frequently exposed to these intestinal antigens. No marked changes were observed in beef, shrimp, crab, chicken, pork, or mushroom specific IgG between CD patients and HCs. This may be because CD patients subconsciously avoid triggering foods (e.g., beef, shrimp, crab, chicken, pork, and mushroom) to alleviate the antibody response.

Food-specific IgG antibodies are often discovered in IBD patients whose small intestine is affected, which might be related to lactose malabsorption[17,41]. A survey showed that IgG-positive IBD patients had higher mean levels of ESR and high sensitivity-CRP and had severe disease activity[26]. In our study, there was no significant difference in the CDAI and Mayo score between the positive and negative IgG antibody subgroups. The multiple positive allergens group had a higher CDAI/Mayo score compared with the single positive allergen group. In addition, the food-specific IgG-positive group had higher levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as ESR and CRP, leukocyte count, and platelet count compared to the food-specific IgG-negative group, although no significant differences were observed.

In some studies, it was reported that food intolerance was more common in females than in males[42-45]. In this study, females were 2.07-fold more likely than males to develop food intolerance, but this difference was not statistically significant. Some studies have demonstrated that female hormones exert a pro-inflammatory effect, while testosterone inhibits the pro-inflammatory process, such as histamine release and mast cell degranulation[46]. Some investigations have reported that the elderly population may be more likely to develop food allergies than younger individuals[47]. However, other studies have revealed that the younger age group had higher levels of food-specific IgG compared with older people[45,48], which is similar to the results in the present study. Maturation of intestinal mucosa with increasing age may influence food intolerance resulting in differential immune responses at different ages. This study also demonstrated that CD patients were more predisposed to food intolerance than UC patients. Smoking was found to be a risk factor for food intolerance in IBD patients. The etiology and pathogenesis of smoking in IBD is not yet entirely clear due to the complex chemical composition of tobacco. Potential mechanisms worth considering include gene expression changes relevant to immune responses and the citrullination of various proteins, which then influence the three-dimensional structure of proteins in such a way that the altered proteins subsequently act as antigens[49].

Anti-TNFα, a biological agent, has been confirmed to be effective in the treatment of IBD patients. Our study showed higher levels of total food-specific IgG in IBD patients receiving anti-TNFα therapy compared to patients receiving treatment with steroids or immunosuppressants. A decrease in total food-specific IgG levels in IBD patients was observed after the introduction of anti-TNFα therapy. Anti-TNFα treatment can result in long-term remission and mucosal healing. Intestinal barrier repair and prolonged inflammation suppression may improve intestinal barrier dysfunction, which prevents food antigens from entering the circulation leading to the production of food-specific IgG[45].

The present study has several limitations. Firstly, we only tested common food-specific IgG antibodies and did not measure food-specific IgG to nuts, fruits or food ingredients. Secondly, we did not conduct a follow-up study to determine whether excluding IgG-positive foods had an effect on IBD patients. Thirdly, children were not included in our study. Finally, our sample size was small; therefore, larger cohort studies should be conducted to confirm our results and to reveal the possible underlying mechanism.

In conclusion, the level of food-specific IgG is higher in CD patients than in UC patients and HCs. IBD patients may be prone to rice, corn, tomato and soybean intolerance. Although the mechanism of food intolerance in IBD is still unclear, we believe that food-specific IgG antibodies may provide a clinical benefit for IBD patients via diet restriction. The role of food-specific IgG in food intolerance should be investigated in future studies.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Some food antigens have been considered to be involved in the processes of formation and development of human chronic intestinal inflammatory diseases. Food allergy and food intolerance are two types of adverse reactions to food. Food allergy is typically mediated by IgE antibodies. In contrast, food intolerance is mediated by IgG antibodies. However, this mechanism is disputable, as some studies found that food IgG and IgE antibodies can be expressed in healthy individuals. The purpose of this study was to analyze the levels of immunoglobulin G (IgG) and E (IgE) antibodies against food antigens in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients and explore their clinical value in IBD pathogenesis.

Research background

IBD is a chronic relapsing inflammatory disease of the gastrointestinal tract, which includes ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD). Increasing evidence indicates that IBD results from an abnormal mucosal immune system triggered by environmental factors. Of these factors, food antigens have been considered to involve in the processes of formation and development of IBD. Food allergy and food intolerance are two types of adverse reaction to food. Food allergy is typically mediated by IgE antibodies. In contrast, food intolerance is mediated by IgG antibodies. However, this mechanism is disputable, as some studies found that food IgG and IgE antibodies can be expressed in healthy individuals.

Research motivation

Food antigens have been suggested to participate in the etiopathogenesis of IBD. The advantages from removing certain foods from daily diet was focused on in recent studies. A number of IBD patients suffer from food intolerances, and they show an improvement of well-being by avoiding specific nutritive components. Previous studies have either researched on the potential involvement of various IgG/IgE subclasses in food intolerance/allergy. Although testing for the presence of food-specific IgG/IgEs has been regarded as a potential tool for the diagnosis of food intolerance/allergy, the accuracy and clinical utility of such testing remain unknown.

Research objectives

The purpose of this study was to analyze the levels of IgG and IgE antibodies against food antigens in IBD patients and explore the clinical value in the pathogenesis of IBD.

Research methods

A total of 137 IBD patients, including 40 patients with UC and 97 patients with CD, and 50 healthy controls (HCs) were enrolled in this study. Blood samples were obtained from patients who visited the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between August 2016 and January 2018. Serum IgG antibodies to 14 unique food antigens were assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. IgE-specific antibodies to food allergens were examined by Western blot.

Research results

CD patients had a higher prevalence of food-specific IgG compared to UC patients. CD patients were more sensitive to tomato, corn, rice, soybean, wheat and codfish, while UC patients were more sensitive to tomato, corn and rice. Significantly higher levels of total food-specific IgG were detected in IBD patients treated with anti-TNFα therapy compared to patients receiving steroids or immunosuppressants. A decrease in food-specific IgG levels was detected in IBD patients after receiving anti-TNFα therapy. Smokers and CD patients were prone to developing serum food-specific IgG antibodies.

Research conclusions

The prevalence of food-specific IgG is higher in CD patients than in UC patients and HCs. IBD patients may be prone to rice, corn, tomato and soybean intolerance.

Research perspectives

Food-specific IgG antibodies may provide a clinical benefit for IBD patients via diet restriction. In the future, the role of food-specific IgG in food intolerance should be further investigated.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

An abstract of this study was invited as an E-poster in APDW 2018 and was published as an abstract only in the Journal of Digestive Disease, 2018.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: This study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Informed consent statement: All study participants provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: April 12, 2019

First decision: May 16, 2019

Article in press: July 3, 2019

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Nenna R, Carroccio A, Jamali R, Rodrigo L S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Hai-Yang Wang, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Sir Run Run Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211100, Jiangsu Province, China; Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Yi Li, Department of Gastroenterology, The Affiliated Sir Run Run Hospital, Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 211100, Jiangsu Province, China.

Jia-Jia Li, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Chun-Hua Jiao, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xiao-Jing Zhao, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xue-Ting Li, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Mei-Jiao Lu, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Xia-Qiong Mao, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China.

Hong-Jie Zhang, Department of Gastroenterology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing 210029, Jiangsu Province, China. hjzhang06@163.com.

References

- 1.Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Unravelling the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2007;448:427–434. doi: 10.1038/nature06005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou GX, Liu ZJ. Potential roles of neutrophils in regulating intestinal mucosal inflammation of inflammatory bowel disease. J Dig Dis. 2017;18:495–503. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regueiro M, Kip KE, Cheung O, Hegazi RA, Plevy S. Cigarette smoking and age at diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:42–47. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kane SV, Flicker M, Katz-Nelson F. Tobacco use is associated with accelerated clinical recurrence of Crohn's disease after surgically induced remission. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Picco MF, Bayless TM. Tobacco consumption and disease duration are associated with fistulizing and stricturing behaviors in the first 8 years of Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:363–368. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafner S, Timmer A, Herfarth H, Rogler G, Schölmerich J, Schäffler A, Ehrenstein B, Jilg W, Ott C, Strauch UG, Obermeier F. The role of domestic hygiene in inflammatory bowel diseases: hepatitis A and worm infestations. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:561–566. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3282f495dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hou JK, Abraham B, El-Serag H. Dietary intake and risk of developing inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:563–573. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakamoto N, Kono S, Wakai K, Fukuda Y, Satomi M, Shimoyama T, Inaba Y, Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Okamoto K, Kobashi G, Washio M, Yokoyama T, Date C, Tanaka H Epidemiology Group of the Research Committee on Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Japan. Dietary risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter case-control study in Japan. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:154–163. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200502000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Pearce MS, Phillips E, Gregory W, Barton JR, Welfare MR. Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2004;53:1479–1484. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IBD in EPIC Study Investigators. Tjonneland A, Overvad K, Bergmann MM, Nagel G, Linseisen J, Hallmans G, Palmqvist R, Sjodin H, Hagglund G, Berglund G, Lindgren S, Grip O, Palli D, Day NE, Khaw KT, Bingham S, Riboli E, Kennedy H, Hart A. Linoleic acid, a dietary n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid, and the aetiology of ulcerative colitis: a nested case-control study within a European prospective cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:1606–1611. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.169078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uchiyama K, Nakamura M, Odahara S, Koido S, Katahira K, Shiraishi H, Ohkusa T, Fujise K, Tajiri H. N-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid diet therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1696–1707. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Phillips E, Gregory W, Barton JR, Welfare MR. Dietary beliefs of people with ulcerative colitis and their effect on relapse and nutrient intake. Clin Nutr. 2004;23:161–170. doi: 10.1016/S0261-5614(03)00132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magee EA, Edmond LM, Tasker SM, Kong SC, Curno R, Cummings JH. Associations between diet and disease activity in ulcerative colitis patients using a novel method of data analysis. Nutr J. 2005;4:7. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-4-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maresca M, Fantini J. Some food-associated mycotoxins as potential risk factors in humans predisposed to chronic intestinal inflammatory diseases. Toxicon. 2010;56:282–294. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferguson LR, Shelling AN, Browning BL, Huebner C, Petermann I. Genes, diet and inflammatory bowel disease. Mutat Res. 2007;622:70–83. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bentz S, Hausmann M, Piberger H, Kellermeier S, Paul S, Held L, Falk W, Obermeier F, Fried M, Schölmerich J, Rogler G. Clinical relevance of IgG antibodies against food antigens in Crohn's disease: a double-blind cross-over diet intervention study. Digestion. 2010;81:252–264. doi: 10.1159/000264649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cai C, Shen J, Zhao D, Qiao Y, Xu A, Jin S, Ran Z, Zheng Q. Serological investigation of food specific immunoglobulin G antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. PLoS One. 2014;9:e112154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cuomo R, Andreozzi P, Zito FP, Passananti V, De Carlo G, Sarnelli G. Irritable bowel syndrome and food interaction. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8837–8845. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mekkel G, Barta Z, Ress Z, Gyimesi E, Sipka S, Zeher M. [Increased IgE-type antibody response to food allergens in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel diseases] Orv Hetil. 2005;146:797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Crowe SE, Perdue MH. Gastrointestinal food hypersensitivity: basic mechanisms of pathophysiology. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1075–1095. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90047-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnes RM, Johnson PM, Harvey MM, Blears J, Finn R. Human serum antibodies reactive with dietary proteins. IgG subclass distribution. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1988;87:184–188. doi: 10.1159/000234670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lessof MH, Kemeny DM, Price JF. IgG antibodies to food in health and disease. Allergy Proc. 1991;12:305–307. doi: 10.2500/108854191778879061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Husby S, Mestecky J, Moldoveanu Z, Holland S, Elson CO. Oral tolerance in humans. T cell but not B cell tolerance after antigen feeding. J Immunol. 1994;152:4663–4670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haddad ZH, Vetter M, Friedmann J, Sainz C, Brunner E. Detection and kinetics of antigen-specific IgE and IgG immune complexes in food allergy. Ann Allergy. 1983;51:255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Husby S, Oxelius VA, Teisner B, Jensenius JC, Svehag SE. Humoral immunity to dietary antigens in healthy adults. Occurrence, isotype and IgG subclass distribution of serum antibodies to protein antigens. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1985;77:416–422. doi: 10.1159/000233819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antico A, Pagani M, Vescovi PP, Bonadonna P, Senna G. Food-specific IgG4 lack diagnostic value in adult patients with chronic urticaria and other suspected allergy skin symptoms. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;155:52–56. doi: 10.1159/000318736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Cullen GJ, Daperno M, Kucharzik T, Rieder F, Almer S, Armuzzi A, Harbord M, Langhorst J, Sans M, Chowers Y, Fiorino G, Juillerat P, Mantzaris GJ, Rizzello F, Vavricka S, Gionchetti P ECCO. 3rd European Evidence-based Consensus on the Diagnosis and Management of Crohn's Disease 2016: Part 1: Diagnosis and Medical Management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:3–25. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Magro F, Gionchetti P, Eliakim R, Ardizzone S, Armuzzi A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Burisch J, Gecse KB, Hart AL, Hindryckx P, Langner C, Limdi JK, Pellino G, Zagórowicz E, Raine T, Harbord M, Rieder F. European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation [ECCO]. Third European Evidence-based Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Ulcerative Colitis. Part 1: Definitions, Diagnosis, Extra-intestinal Manifestations, Pregnancy, Cancer Surveillance, Surgery, and Ileo-anal Pouch Disorders. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:649–670. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sai XY, Zheng YS, Zhao JM, Hao W. [A cross sectional survey on the prevalence of food intolerance and its determinants in Beijing, China] Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi. 2011;32:302–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Geremia A, Biancheri P, Allan P, Corazza GR, Di Sabatino A. Innate and adaptive immunity in inflammatory bowel disease. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rajendran N, Kumar D. Role of diet in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1442–1448. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i12.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cashman KD, Shanahan F. Is nutrition an aetiological factor for inflammatory bowel disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:607–613. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200306000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pearson M, Teahon K, Levi AJ, Bjarnason I. Food intolerance and Crohn's disease. Gut. 1993;34:783–787. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.6.783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zar S, Benson MJ, Kumar D. Food-specific serum IgG4 and IgE titers to common food antigens in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1550–1557. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Antico A, Pagani M, Vescovi PP, Bonadonna P, Senna G. Food-specific IgG4 lack diagnostic value in adult patients with chronic urticaria and other suspected allergy skin symptoms. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2011;155:52–56. doi: 10.1159/000318736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Atkinson W, Sheldon TA, Shaath N, Whorwell PJ. Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2004;53:1459–1464. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.037697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alpay K, Ertas M, Orhan EK, Ustay DK, Lieners C, Baykan B. Diet restriction in migraine, based on IgG against foods: a clinical double-blind, randomised, cross-over trial. Cephalalgia. 2010;30:829–837. doi: 10.1177/0333102410361404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peña AS, Crusius JB. Food allergy, coeliac disease and chronic inflammatory bowel disease in man. Vet Q. 1998;20 Suppl 3:S49–S52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huber A, Genser D, Spitzauer S, Scheiner O, Jensen-Jarolim E. IgE/anti-IgE immune complexes in sera from patients with Crohn's disease do not contain food-specific IgE. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1998;115:67–72. doi: 10.1159/000023832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bartůnková J, Kolárová I, Sedivá A, Hölzelová E. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies, and specific IgE to food allergens in children with inflammatory bowel diseases. Clin Immunol. 2002;102:162–168. doi: 10.1006/clim.2001.5145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mishkin B, Yalovsky M, Mishkin S. Increased prevalence of lactose malabsorption in Crohn's disease patients at low risk for lactose malabsorption based on ethnic origin. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:1148–1153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young E, Stoneham MD, Petruckevitch A, Barton J, Rona R. A population study of food intolerance. Lancet. 1994;343:1127–1130. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90234-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schäfer T, Böhler E, Ruhdorfer S, Weigl L, Wessner D, Heinrich J, Filipiak B, Wichmann HE, Ring J. Epidemiology of food allergy/food intolerance in adults: associations with other manifestations of atopy. Allergy. 2001;56:1172–1179. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2001.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zuberbier T, Edenharter G, Worm M, Ehlers I, Reimann S, Hantke T, Roehr CC, Bergmann KE, Niggemann B. Prevalence of adverse reactions to food in Germany - a population study. Allergy. 2004;59:338–345. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng Q, Dong SY, Wu LX, Li H, Sun ZJ, Li JB, Jiang HX, Chen ZH, Wang QB, Chen WW. Variable food-specific IgG antibody levels in healthy and symptomatic Chinese adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harish Babu BN, Mahesh PA, Venkatesh YP. A cross-sectional study on the prevalence of food allergy to eggplant (Solanum melongena L.) reveals female predominance. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1795–1802. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.03076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Harduar-Morano L, Simon MR, Watkins S, Blackmore C. A population-based epidemiologic study of emergency department visits for anaphylaxis in Florida. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:594–600.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.04.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shakoor Z, AlFaifi A, AlAmro B, AlTawil LN, AlOhaly RY. Prevalence of IgG-mediated food intolerance among patients with allergic symptoms. Ann Saudi Med. 2016;36:386–390. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2016.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yadav P, Ellinghaus D, Rémy G, Freitag-Wolf S, Cesaro A, Degenhardt F, Boucher G, Delacre M International IBD Genetics Consortium, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Pichavant M, Rioux JD, Gosset P, Franke A, Schumm LP, Krawczak M, Chamaillard M, Dempfle A, Andersen V. Genetic Factors Interact With Tobacco Smoke to Modify Risk for Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Humans and Mice. Gastroenterology. 2017;153:550–565. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]