Abstract

Background

Insomnia symptoms are common, affecting almost 30% of the population of the population. Many use medications that may be ineffective and cause substantial harm. In complementary and alternative medicine, acupuncture is widely used to manage mental health problems. Acupuncture therapy emphasizes individualized treatment according to TCM pattern diagnosis. Although there are some systematic reviews that acupuncture has the benefit for insomnia, there is no systematic review on acupuncture using pattern identification. This review aimed for evaluating acupuncture efficacy using pattern-identification to treat insomnia.

Methods

We carried out a comprehensive review of randomized controlled trials (from 2000 to April 12, 2018), using PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, CNKI, and 3 Korean (OASIS, NDSL, RISS4U) databases, comparing acupuncture using pattern identification (only) with medication in primary insomnia. Response rate and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were the primary outcomes. Risk of bias and publication biases were evaluated, and meta-analyses were conducted.

Results

Nineteen RCTs were included (11 manual acupuncture (1079 patients), 8 electro-acupuncture (442 patients)) of low quality. Meta-analyses of all studies reveled that acupuncture improved total effectiveness rate (Risk Ratio [RR] = 1.23, 95% confidence intervals [CIs]: 1.12–1.35, p < 0.00001; I2 = 80%) and PSQI (MD = −1.92, 95% CI: −2.41–1.42, p < 0.00001; I2 = 30%) compared to medication. Results of overall risk of bias assessments were unclear or high.

Conclusions

Acupuncture using pattern identification led to significantly improved total effectiveness rate compared to medication. With regard to PSQI, as compared to the control group, acupuncture using pattern identification was similar to medication. However, this study has limitations of high risk of bias, not using a standardized pattern-diagnosis-treatment and not comparing with standarized acupuncture without pattern identification.

Keywords: Insomnia, Acupuncture, Pattern identification, Systematic review, Meta-Analysis, Randomized controlled trial

1. Introduction

According to the third edition of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD)1 “Insomnia disorder is defined as difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep; it is associated with daytime consequences but is not attributable to environmental circumstances or inadequate opportunity to sleep.” Epidemiological studies estimate that the prevalence of chronic insomnia, in developed nations, varies from 5% to 10%.2 Chronic insomnia is associated with marked impairments to function and quality of life.3

Pharmacotherapy is used mostly standard treatment approach for the management of chronic insomnia.4 Despite clear guidelines stating that hypnotic drugs should be restricted to short-term use,5 many individuals use medications that may not be effective and/or harmful.4 Benzodiazepines, widely used as hypnotic drugs, have various side effects, including drowsiness, lethargy, fatigue, excessive sedation, stupor, next-day “hangover effects,” disturbances to concentration and attention, dependence, symptom rebound (i.e., recurrence of the original sleep disorder) after discontinuation, as well as hypotonia and ataxia.6

According to the 2007 United States National Health Interview Survey, adults who suffered from insomnia received more than one CAM therapy per year is about 45%.7 People with insomnia search for alternative and non-drug treatments including acupuncture.8 Acupuncture is widely used for managing mental health problems. A review done by the Department of Veterans Affairs in 2014 showed overview of the evidence base of acupuncture for mental health such as depression, schizophrenia, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), addiction, and chronic fatigue syndrome.9

In actual clinical practice, traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) treatments for insomnia are personalized in accordance with TCM diagnostic patterns (as per traditional Chinese and Korean medicine theory). A unique characteristic of traditional Chinese and Korean medicine is the emphasis placed on individuality. A TCM pattern, in terms of TCM theory, is a diagnostic consequence based on pathological changes to disease state (i.e. individual signs and symptoms, including pulse form and tongue appearance).10 Pattern-identification (PI) leads the practitioner toward a treatment principle, to select relevant acupuncture points or herbal formulas. It differentiates biological diseases into patterns, and each pattern consists of symptoms relevant to their own individual medical protocol. Therefore, this forms the theory that different TCM treatments can be given for the same disease.

There are some previous systematic reviews on the efficacy of acupuncture for insomnia, and the authors concluded that acupuncture may be effective for primary insomnia.11, 12, 13, 14 But acupuncture therapy emphasizes individualized treatment, based on TCM pattern diagnosis. Although it is considered that pattern-based TCM treatment provides better effectiveness, studies concerning the benefits of TCM pattern differentiation are rare. To date, there are few systematic reviews or meta-analyses regarding acupuncture using PI for the treatment of insomnia.

One such review evaluated acupuncture for insomnia of Yin deficiency type. The limitations of the review, apart from considering only one pattern of deficiency, were a small number of included sutdy and heterogeneity of intervention.15 And three RCTs reported that the efficacy of pattern-based, individualized acupuncture was not better to usual acupuncture for chronic shoulder pain,16 chronic back pain,17 and hypertension.18 However, no such evidence has been reported for insomnia.

The individualized acupuncture therapy using PI was utilized in actual clinical setting of TCM & TKM. And many patients with chronic insomnia use medications that may not be effective and/or that may be harmful also seek complementary and alternatives and non-pharmacological intervention like acupuncture. Therefore, it is meaningful to compare the effect of acupuncture using PI with medication. This comparison is to reflect acupuncture treatment in real world and a result from this comparison may provide useful evidence to practitioners in clinical practice. We only included trials assessing manual & electro acupuncture therapy, based on pattern-identification.

2. Methods

We reported this review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.19

2.1. Electronic searches and search strategy

The electronic databases we searched are as follows: PubMed (Medline), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, China National Knowledge Infrastructure,and 3 Korean databases (OASIS, NDSL, RISS4U). The publication time-range was from January 1, 2000 to April 12, 2018. We searched terms related to acupuncture (including a Mesh search using "Sleep Initiation and Maintenance Disorders" OR "Sleep" OR "Sleep Wake Disorders" OR "Sleep Stages" OR "Sleep Deprivation" OR "Wakefulness" OR sleep* OR insomnia* OR wakeful* OR sleepless* OR dyssomn*) and insomnia(including a Mesh search using "Acupuncture" OR "Acupuncture Therapy" OR "Acupuncture, Ear" OR "Acupuncture Points" OR "Acupuncture Analgesia" OR “Electroacupuncture”). Supplement 1 reveals specific search terms for each database. There was no language restriction in the search strategy. After the literature search, we exclude the duplicated and irrelevant papers. The titles and abstracts of all articles were reviewed and irrelevant articles were excluded. Finally, the references of all eligible full-text articles were examined for relevant randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

2.2. Eligibility criteria and study selection

Two authors independently examined the titles and abstracts of the retrieved articles and selected all potentially relevant studies. Reviewer disagreements (about inclusion and exclusion) were resolved by discussion. Identified abstracts and citations were evaluated according to the following inclusion criteria.

2.2.1. Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials with parallel-group or cross-over designs were included. We excluded non-RCTs (mechanism studies, non-controlled studies, case reports, feasibility studies, reviews) and quasi-randomized trials.

2.2.2. Types of participants

Participants with a clinical diagnosis of primary insomnia were included. We excluded participants if there were no criteria for a diagnosis of primary insomnia. Participants were included if diagnosed by standard diagnostic criteria, including: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM),20 International Classification of Sleep Disorders (ICSD),21 International Classification of Diseases (ICD),22 or Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders (CCMD).23 We excluded participants with comorbid mental disorders (major depressive or anxiety disorders) or other sleep disorders, except primary insomnia, along with participants under 18 years of age. Participants with sub-health insomnia or stress induced insomnia were excluded.

2.2.3. Types of interventions

Trials that evaluated manual acupuncture and electroacupuncture using PI were included, without regard to the number of treatment times or length of the treatment period.

The acupuncture methods included in this study are as follows: stimulation of specific acupoints along the skin of the body using needles and needles with electrical currents, without simultaneous application of heat, pharmaco-acupuncture, or laser light. RCTs that used acupressure, laser acupuncture, auricular therapy, magnetic acupressure, or transcutaneous electrical acupoint-stimulation were excluded. We excluded special acupuncture therapies that used acupoints located in specific parts of the body, such as head-acupuncture or abdominal or umbilical inner acupoints. We also excluded a combined intervention such as acupuncture plus medication. We included RCTs that used acupuncture therapy only, and excluded RCTs that combined acupuncture with another therapy or treatment, including hypnotics, herbal medicine, vitamin supplementation, moxibustion, tuina, psychotherapy, psychoeducation, meditation, qi-gong, footbath, or another alternative complementary treatment.

Control interventions included medication, no treatment, sham acupuncture (i.e. needles placed on the skin without penetration or needles puncturing a non-acupuncture or non-specific point). Medication like non-benzodiazepine hypnotics and benzodiazepine receptor agonists, is routinely used to treat insomnia. RCTs that used herbal medicine, vitamin supplementation, moxibustion, tuina, psychotherapy, psychoeducation, meditation, qi-gong, footbath, or any alternative complementary treatment for comparison were excluded.

If data on the treatment effects of separate conditions was unavailable, the study was excluded.

2.2.4. Types of outcome measurements

The primary outcome was response rate and global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score. The following four grades are used to evaluate response rate: 1) basically cured (i.e. sleep time recovered to normal, and sleep time lasting more than 6 h, no awakening during sleep, and no fatigue during daytime); 2) markedly improved (i.e. significantly restored sleep time, sleep time lasting more than 3 h, and increased depth of sleep); 3) improved (i.e. restored sleep time, sleep time lasting within 3 h); 4) unimproved (i.e. no improvement at all or worsening of symptoms).24 response rate indicate the percentage of total number of participants categorized within the first three grades.

The PSQI, validated in both English and Chinese, is used to measure the quality and patterns of sleep. There are limited studies evaluating the minimal clinically important difference (MCID) for PSQI. Reports suggest a change from 1.54 to 3.00 points.25 However, due to a lack of universal acceptance of a MCID, in this review any statistically significant effect between the groups, at the end of the treatment period, was considered important.

2.3. Data collection

To retrieve, select, and perform data extraction were by two independent reviewers. Studies were coded for reliability by two raters, and results were compared to confirm accuracy. Rater differences were settled through discussion and agreement. Studies were coded for the following characteristics: study design, setting, diagnostic criteria, duration of insomnia, sample size, age and gender of participants, intervention, control, treatment duration, follow-up duration, outcomes, and adverse events. Incomplete data or queries were followed-up with the original authors via email.

2.4. Assessment of risk of bias

Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool.29 Risk of bias was evaluated against the following seven domains: 1) sequence generation, 2) allocation concealment, 3) blinding of participants, 4) blinding of personnel, 5) blinding of outcome assessors, 6) incomplete outcome data, and 7) selective reporting. Other biases were assessed according to baseline balance and source of funding. The risk of bias in each domain was evaluated, and categorized into three groups based on the Cochrane risk of bias assessment tool: 1) ‘low risk of bias’; 2) ‘high risk of bias’; 3) ‘unclear risk of bias’. Risk of bias was assessed by two independent researchers (SHK and JHJ). Disagreements were resolved by discussion and consultation with a third researcher (JHL).

Blinding of personnel was not possible, as acupuncture needs to be performed by a qualified professional. Lack of personnel blinding is associated with a high risk of bias; however, this should be interpreted with the knowledge that blinding is not feasible in acupuncture studies.

2.5. Summary measures and synthesis of results

The meta-analyses were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) software [Version 5.3. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014]. Risk ratios (RRs) were used for dichotomous outcomes and mean differences (MDs) were adopted for continuous outcomes.26 Heterogeneity was examined using the I2 test; Thresholds for the interpretation of the I2 statistic can be misleading, since the importance of inconsistency depends on several factors. We considered heterogeneity by a rough guide to interpretation is as follows30:

-

•

the I2 value: 0%–40%: might not be important;

-

•

the I2 value: 30%–60%: may represent moderate heterogeneity;

-

•

the I2 value: 50%–90%: may represent substantial heterogeneity;

-

•

the I2 value: 75%–100%: considerable heterogeneity.

Confidence intervals (CIs) were established at 95%. Probability (P) values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. If the necessary data were available, we conducted a subgroup analysis to explore the possible cause of the heterogeneity according to the type of acupuncture such as manual acupuncture or electro-acupuncture and smilar PI. We also assessed the publication bias by using a funnel plot according to type of acupuncture.

3. Results

3.1. Study inclusion

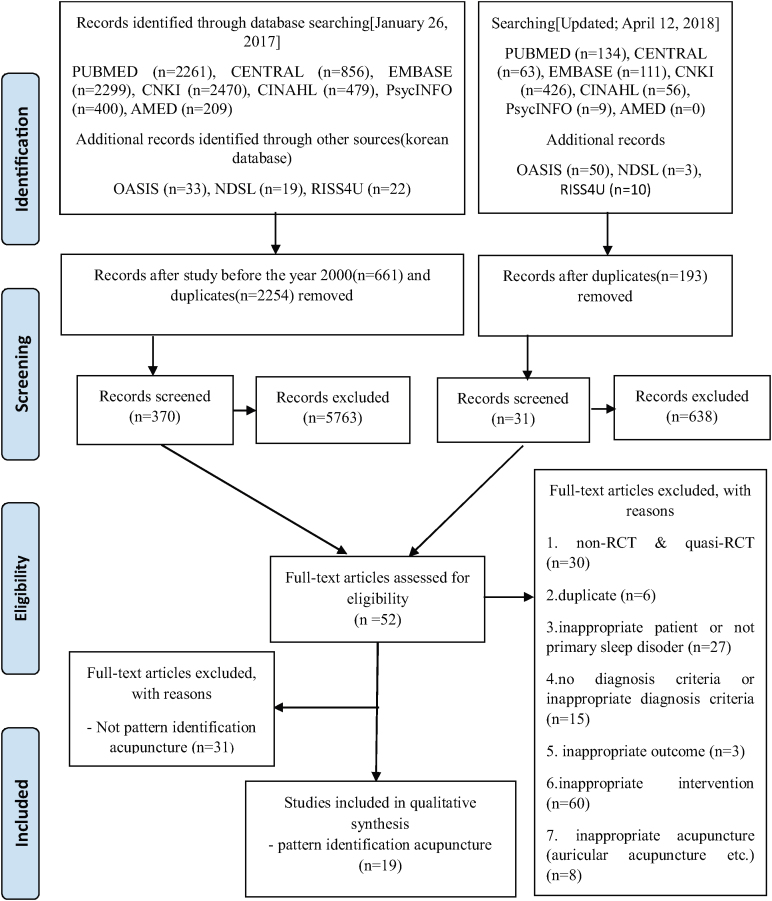

Total 9901 citations were identified (updated searching: n = 862). Studies that did not use PI acupuncture (31 studies) were excluded (Fig. 1). Finally, 19 RCTs (11 manual acupuncture(1079 patients),27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37 8 electro-acupuncture(442 patients38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45) that met the inclusion criteria.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA 2009 Flow Diagram of the study selection process. RCT: randomized controlled trial.

3.2. Study characteristics

The characteristics of included studies are summarized in Table 1. All included studies (19 articles) were conducted in Chinese. The number of patients involved the studies ranged from 25 to 192 in the treatment group and 25 to 190 in the control group. Diagnostic criteria included DSM (2 studies),28, 46 ICD (3 studies),33, 35, 43 ICSD (1 study),29 and CCMD (15 studies).,27, 30, 31, 32, 34, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 44, 45 Of the 19 included studies (13 manual acupuncture, 8 electro-acupuncture), estazolam (1 or 2 mg/day) used for comparision in 14 studies (1 or 2 mg/day),28, 30, 31, 33,35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 alprazolam (0.4 mg/day) in 3 studies (0.4 mg/day),27, 32, 40 clonazepam (2 mg/day) in 2,34, 41 diazepam (5 mg/day),29 and zopiclone (7.5 mg/day) in 1 study respectively. The number of treatment session was from 14 to 60, and the duration of treatment was from 16 days to 74 days.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Author (year) |

No. of participants AT/Med | Diagnostic criteria |

Type of AT | Medication (mg/day) |

Treatment sessions/duration (days) | Outcome measures |

Adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fu (2012)27 | 43/43 | CCMD-3 | MA | Alprazolam 0.4 | 30/30 | Response rate, SPIEGEL | NR |

| Wang (2014)32 | 38/38 | CCMD-3 | MA | Alprazolam 0.4 | 40/40 | Response rate | AT: none; Med: mouth, fatigue, dizziness, sleepiness* |

| Wei (2010)34 | 42/39 | CCMD-2-R | MA | Clonazepam 2 | 20/22 | Response rate | NR |

| Pan (2004)29,** | 192/190 | ICSD-2 |

MA | Diazepam 5 | 30/36-40 | Response rate | NR |

| Han (2017)37 | 68/68 | CCMD-3 | MA | Estazolam 2 | 24/28 | Response rate, PSQI | NR |

| Liu (2017)28 | 31/30 | DSM 5 |

MA | Estazolam 1 | 20/28 | PSQI, MSL of MSLT | NR |

| Su (2011)30 | 39/37 | CCMD-2-R | MA | Estazolam 4 | 28/28 | Response rate, PSQI | AT: needle sickness event (1); Med: headache (3), dizziness (2), nausea (1), sleepiness (2) |

| Wang (2008)31 | 50/28 | CCMD-2-R | MA | Estazolam 2 | 30/30 | Response rate | NR |

| Wang (2015)33 | 30/30 | ICD-10 | MA | Estazolam 1 | 24/28 | Response rate, PSQI, SDS, SAS | NR |

| Zhang (2013)33 | 35/35 | ICD-10 | MA | Estazolam 2 | 24/28 | Response rate | NR |

| Zhao (2013)36 | 40/40 | CCMD-3 | MA | Estazolam 1 | 14/16 | Response rate | NR |

| Bai (2011)38 | 30/30 | CCMD-3 | EA | Estazolam 1 | 30 / 30 | Response rate, PSQI | NR |

| Cheng (2015)39 | 38/37 | CCMD-3 | EA | Estazolam 1-2 | 24 / 28 | Response rate | NR |

| Liu (2010)40 | 30/30 | CCMD-3 | EA | Alprazolam 0.4 | 20 / 28 | Response rate | NR |

| Ma (2006)41 | 31/31 | CCMD-3 | EA | Clonazepam 2 | 21 / 30 | Response rate | NR |

| Wang (2013)40 | 25/25 | CCMD-2-R | EA | Estazolam 2 | 60 / 74 | Response rate, PSQI | NR |

| Xing (2010)43 | 25/25 | ICD-10 | EA | Estazolam 2 | 30 / 30 | PSQI | NR |

| Xu (2014)44 | 45/30 | CCMD-3 | EA | Estazolam 1 | 21 / 21 | Response rate, PSQI | NR |

| Zhu (2015)45 | 30/30 | CCMD-3 | EA | Estazolam 1 | 21 / 21 | Response rate, PSQI, HAMA | NR |

AT: acupuncture; CCMD-2-R, Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders Second Edition-Revision; CCMD-3, Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders Third Revision; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition; ICSD-2, American association of sleep medicine. international classification of sleep disorders-II); EA, Electro-acupuncture; ICD-10, International Classification of Disease Tenth Revision; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; MA, Manual acupuncture; Med: medication; MSLT, Multiple sleep latency test; MSL, Mean sleep latency; NR: not reported; SPIEGEL, Spiegel Sleep Questionnaire; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; SDS, Self Rating Depression Scale; SAS, Self Rating Anxiety Scale.

This study did not report the precise number of adverse events.

Only this study assessed 3 months follow-up.

Most studies used rate of symptom improvement as an outcome measure except 1 study,43 11 studies used the PSQI,28, 30, 33, 37,38, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46 1 used the Spiegel Sleep Questionnaire,27 1 used the multiple sleep latency and mean sleep latency tests,28 and 1 used the Self Rating Depression and Anxiety Scales,33 and 1 used Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale.45 Two study reported adverse effect.30, 31 Only one study reported the follow-up period.29

3.3. Pattern identificaton

Table 2 summarizes the common and specific acupoints relevant to the pattern identification methods used in the 19 RCTs. Three to seven kinds of pattern identification were used for each study and sixteen kinds of pattern identification in all studies were used. All pattern identification strategies were used, including Deficiency of heart and spleen (n = 19), Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi (n = 15), Disharmony between heart and kidney (n = 12), Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency (n = 11), Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat (n = 10), Depression of the liver generates fire (n = 10), Liver-fire disturbing heart (n = 3), Ascendant hyperactivity of liver-yang (n = 6), Incoordination between spleen and stomach (n = 6), Stagnation of qi due to depression of the liver (n = 4), Interior stagnation of blood vessel (n = 3), Stagnation of phlegm (n = 1), Liver depression and stagnation (n = 1), Liver depression invading stomach (n = 1), Liver depression invading heart (n = 1), Deficiency of kidney due to liver hyperactivity (n = 1). The most frequently used pattern-identification-diagnose were Deficiency of heart and spleen (n = 19). The most frequently used common acupoints were GV20 (Governor Vessel 20) (n = 15), EX-HN1 (the four extra acupuncture points Four Alert Spirit SISHENCONG) (n = 12), EX sleep (Ex-HN Peaceful Sleep ANMIAN ) (n = 9), HT7 (Heart 7 spirit gate Shenmen) (n = 9), and SP6 (Spleen 6 Sanyinjia) (n = 5). The acupoints used for each TCM pattern were also not standardized. A number of acupoints were used, ranging from 6-8 to 18-24. One study29 used not common acupuncture point but only specific acupuncture point for each pattern identification. There are three kinds of the chinese specific diagnostic criteria used for pattern identification in our included study.24, 47, 48 Only 8 studies29, 34, 35, 36, 37 reported the specific diagnostic criteria used. Only 3 study39, 40, 45 of 8 study used electro-acupuncture reported some acupoint with electric stimulation.

Table 2.

Each pattern identification and specific acupuncture point of the included studies.

| Author (year) | No. of total acupoint Common acupuncture point |

Specific acupuncture point for each pattern identification | The diagnostic criteria used for pattern identification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fu (2012)27 | 13-15 GV20, PC6, HT7, ST36, SP6, EX-Sleep |

Deficiency of both heart and spleen: BL15, BL20; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: KI6; Interior stagnation of blood vessel: BL17, SP10; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, BL19; Disharmony between heart and kidney: BL15, BL23; Stagnation of qi due to depression of the liver: BL18, LR3 | NR |

| Wang (2014)32 | 11-12 GV20, EX-HN1, HT7, PC6, EX-Sleep |

Deficiency of both heart and spleen: BL15, BL20, SP6; Disharmony between heart and kidney: KI2, KI3; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, BL19, GB40; Ascendant hyperactivity of liver-yang: KI4, LR3; Incoordination between spleen and stomach: CV12, ST36, ST40 | NR |

| Wei (2010)34 | 0-12 KI6, BL62 |

Depression of the liver generates fire: PC6, LR2, BL18; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat: HT7, PC6, SP4, ST40; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: KI3, BL15, BL23; Deficiency of both heart and spleen: BL15, BL20, ST36, SP6; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: PC7, BL18, BL19 HT6 | Guiding principles for clinical research on new drug of TCM |

| Pan (2004)29 | 6-8 None |

Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: GB20, HT7, KI7; Deficiency of both heart and spleen: GB20, HT7, SP6; Depression of the liver generates fire: GB20, HT7, LR3; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat: GB20, HT7, ST40, CV12; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: GB20, BL19, HT7, LI4 | Syndrome differentiation and treatment of Acupuncture and Moxibustion in clinical setting |

| Han (2017)37 | 8-9 GV20, EX-HN1 |

Stagnation of phlegm: ST40, CV12; Deficiency of both heart and spleen: SP6, ST36; Stagnation of qi due to depression of the liver: BL18, LR3; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: SP6, KD4; Disharmony between heart and kidney: KD6, HT5 |

Standard of TCM Diagnosis and Treatment Effect |

| Liu (2017)28 | 17 EX-HN1, EX-Sleep, HT7, SP6, KI6, BL62 |

Liver-fire disturbing heart: LR2, GB43; Phlegm-heat disturbing heart: ST40, PC8; Deficiency of both heart and spleen: BL15, BL20; Disharmony between heart and kidney: BL15, BL23; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, BL19 | NR |

| Su (2011)30 | 10-12 HT5, HT7 |

Deficiency of both heart and spleen: BL15, BL20, SP6, ST36; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, BL19, PC7; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: KI3, LR3, KI1 | NR |

| Wang (2008)31 | 12-13 GV20, EX-HN1, HT7, EX-Sleep, SP6 |

Disturbing upward of liver fire: LI4, LR2, LR3; Deficiency of both heart and spleen: BL15, BL20, ST36, SP9; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: PC7, KI3, LR3 | NR |

| Wang (2015)33 | 12-13 GV20, EX-HN1, EX-Sleep, BL17, BL18, LR3 |

Ascendant hyperactivity of liver-yang: KI3, LI11, SP6; Liver depression and stagnation: SP10, LI4; Depression of the liver generates fire: LR2, GB43; Liver depression invading stomach: BL21, ST34, ST36; Liver depression invading heart: BL15, PC6, HT7; Deficiency of kidney due to liver hyperactivity: BL23, KI3 |

NR |

| Zhang (2013)33 | 9-10 GV20, EX-HN1, PC6, HT7 |

Liver-fire disturbing heart: LR2, LR3, GB20; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat: LR3, ST40; Failure of stomach-qi: ST36, CV12, ST25; Internal stagnation of the blood: BL17, BL18, SP10; Deficiency of both heart and spleen: BL15, BL20, SP6; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, BL19; Disharmony between heart and kidney: KI3, BL15, BL17 | Standard of TCM Diagnosis and Treatment Effect |

| Zhao (2013)36 | 9-10 GV20, EX-HN1, HT7, PC6 |

Deficiency of heart and spleen: ST36, SP6; Disharmony between heart and kidney: KI2, KI3; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL17, ST36, EX-HN3; Ascendant hyperactivity of liver-yang: LI4, LR3; Incoordination between spleen and stomach: CV12, ST36, ST40 |

Guiding principles for clinical research on new drug of TCM |

| Bai (2011)38 | 16-20 UB62, KD6, UB59, BL61, KI8, KI2, UB1, |

Deficiency of heart and spleen: BL15, BL20; Disharmony between heart and kidney: BL15, BL23, KI3; Ascendant hyperactivity of liver-yang: LR2, LR3, BL18; Incoordination between spleen and stomach: CV12, ST36, ST40 | NR |

| Cheng (2015)39 | 10-16 GV20, GV24(*ES), EX-HN1(*ES), EX-Sleep |

Deficiency of heart and spleen: BL15, BL20, ST36, SP6; Ascendant hyperactivity of liver-yang: GB34; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat: HT7, ST44; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: KI3, HT7; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL19, PC7, GB40 | Standard of TCM Diagnosis and Treatment Effect |

| Liu (2010)40 | 10-12 GV20(*ES), EX-HN1(*ES), EX-HN5(*ES), EX-Sleep(*ES), |

Depression of the liver generates fire: LR1, LR2; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat: PC6, ST44; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: KI3, SP6, PC6; Deficiency of heart and spleen: ST36, PC6; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: PC6,, LR2 | Standard of TCM Diagnosis and Treatment Effect |

| Ma (2006)41 | 10-11 EX-HN1, GV24, GB13, HT7, GV20 |

Deficiency of heart and spleen : ST36, BL17; Disharmony between heart and kidney : KI3, PC7; Deficiency of heart-q and gallbladder-qi: PC6, KI6; Incoordination between spleen and stomach: CV12, ST36; Stagnation of qi due to depression of the liver: LR2, GB20 | NR |

| Wang (2013)40 | 18-24 GV20, GV24, GV14, GV11, CV4, CV7, CV12, CV17, HT6, SP6, EX-Sleep |

Ascendant hyperactivity of liver-yang: LR2, GB20; Stagnation of qi due to depression of the liver: LR3, LI4, LR14; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, LR14, BL19, GB13, GB40, GB34; Deficiency of heart and spleen: BL15, BL20, ST36; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: KI3, PC7; Disharmony between heart and kidney: BL15, BL23 | Standard of TCM Diagnosis and Treatment Effect[76] |

| Xing (2010)43 | 10-12 SP6, PC7, HT6 |

Deficiency of heart and spleen : BL15, BL20; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, BL19, GB40; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: BL15, BL23, KI3; Depression of the liver generates fire : BL18, LR1; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat : CV12, ST40 | NR |

| Xu (2014)44 | 10 EX-HN1, EX-HN5, EX-Sleep |

Deficiency of heart and spleen: BL15, BL20; Deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi: BL15, BL19, GB40; Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency: BL15, BL23, KI3; Depression of the liver generates fire: BL18, LR1; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat: CV12, ST40 | NR |

| Zhu (2015)45 | 21 GV20(ES*), EX-HN1(ES*), EX-HN5, GB20(ES*), HT6, SP6, KI6 |

Deficiency of heart and spleen: PC7, ST36; Disharmony between heart and kidney: PC7, KI3; Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat: PC7, ST40 | NR |

EA, Electro-acupuncture; *ES, Electric Stimulation; EX-Sleep(‘Anmian’[Extra, locates at the midpoint between Yiming (EX-HN 14) and Fengchi(GB 20)]), MA, Manual acupuncture;NR: not reported; TCM: traditional Chinese medicine.

Commonly used acupoints for each pattern were as follows: SP6, ST36, BL15, BL20 for deficiency of heart and spleen; BL15, BL19, GB40, GB20 for deficiency of heart-qi and gallbladder-qi and KI3, BL15, BL23 for disharmony between heart and kidney, BL15, BL23, BL20, SP6, KI3 for Hyperactivity of fire due to yin deficiency, ST40, ST44, PC6, PC7, PC8, LR3, SP9 for Interior disturbance of phlegm-heat, and LR1, LR2, LR3 were for Depression of the liver generates fire.

3.4. Risk of bias

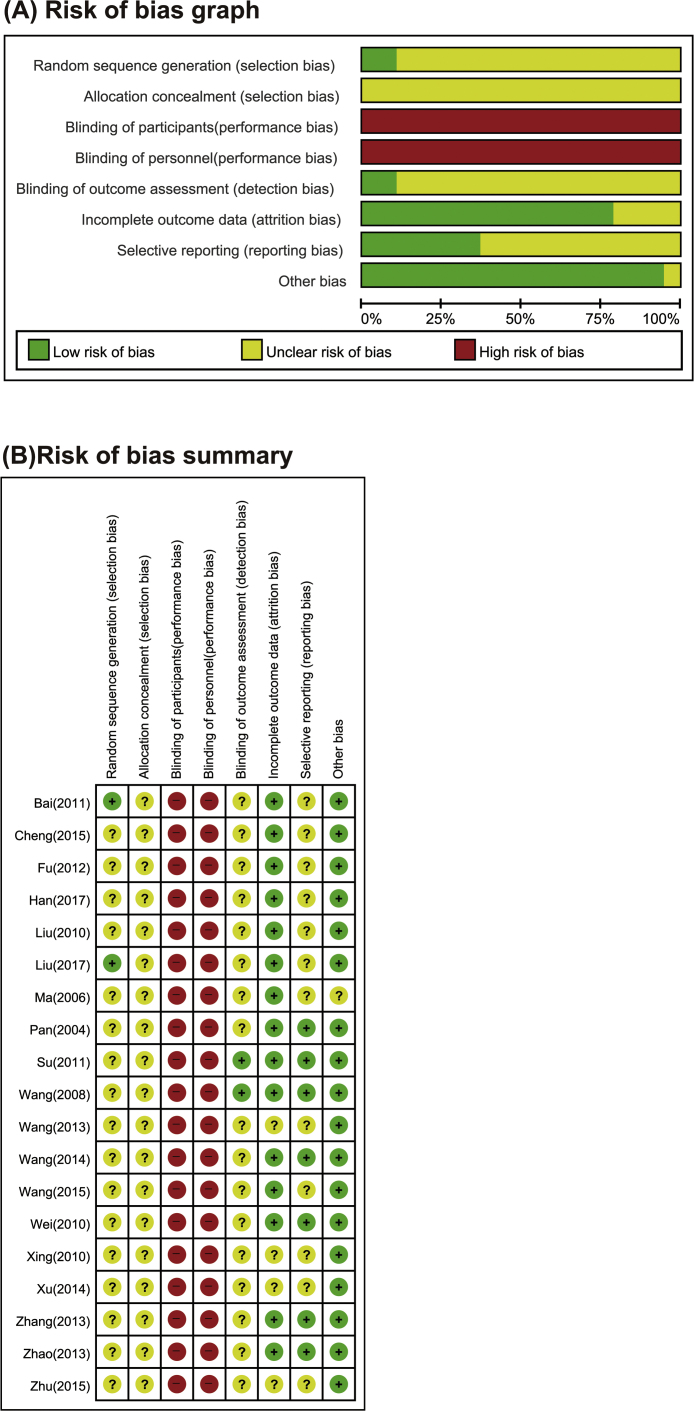

Risks of bias are presented in Fig. 2. The sequence generation was low in only two studies.28, 38 Most studies didn’t described enough information. Most of studies did not have enough description to support clear judgments on allocation concealment. Regarding the blinding of participants and personal, all the included studies were judged as having a high risk of bias because they did not use sham acupuncture as the control. The blinding of outcome assessors was described in only two studies at low risk of bias30, 31; the risk of bias in others were unclear, as there was no explanation we could assess the risk of bias. All studies were rated low risk for incomplete outcome data. The risk of bias in selective reporting was assessed unclear, as study protocols were not always available. Baseline balance had a low risk of bias in all studies.

Fig. 2.

Methodological quality graph. (A) Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. (B) Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.5. Outcomes

3.5.1. Response rate

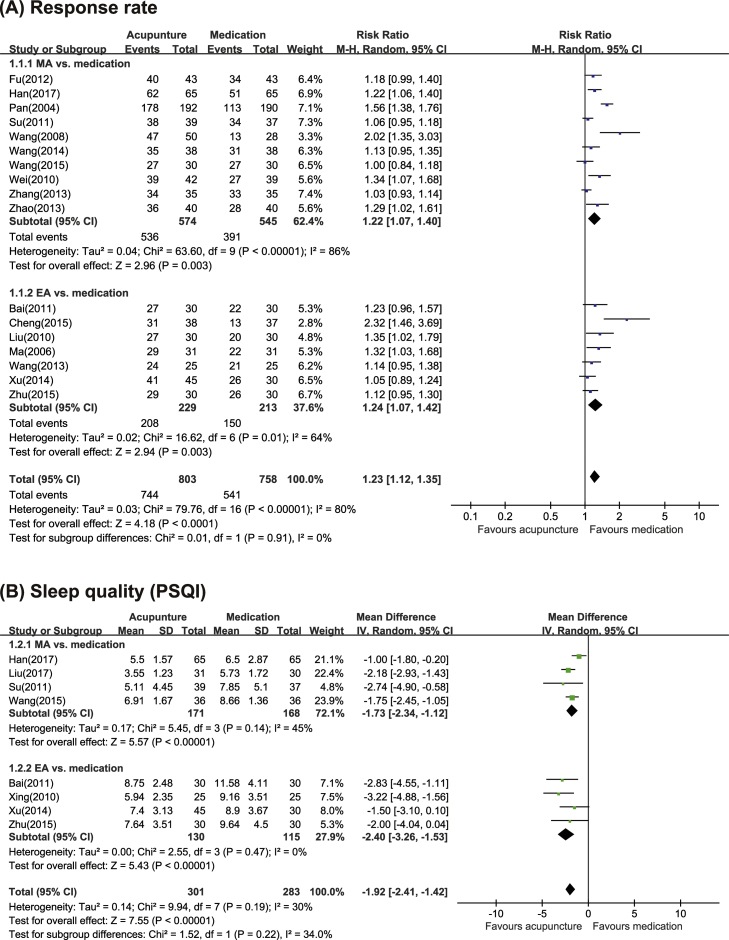

Meta-analysis of 19 included studies shows that acupuncture used PI is more likely to lead to significant improvements in response rate (RR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.12–1.35, p < 0.00001) with severe heterogeneity (I2 = 80%), compared to control medication. (Fig. 3) Sub-analysis according to the type of acupuncture (MA or EA) shows that both manual acupuncture and electro-acupuncture used PI have significant effects compared with medication. (MA: RR = 1.22, 95% CI: 1.07–1.40, p < 0.00001, I2 = 86%; EA: RR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.07–1.40, p < 0.00001, I2 = 64%) (Fig. 3)

Fig. 3.

Forest plots of (A) Response rate; (B) sleep quality (PSQI) for acupuncture vs. medications.

3.5.2. Sleep quality

Eight studies in acupuncture reported post-intervention sleep quality socre in PSQI. Meta-analysis shows that acupuncture used PI is more likely to lead to improvements in sleep quality (MD = −1.92, 95% CI: −2.41–1.42, p < 0.00001) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 30%), compared to medication (Fig. 4). Sub-analysis according to the type of acupuncture (MA or EA) shows that EA is more likely to lead to improvements in sleep quality. (MA: WMD = −1.73, 95% CI: −2.34–1.12, p < 0.00001, I2 = 45%; EA: MD = −2.40, 95% CI: −3.26–1.53, p < 0.00001, I2 = 0%) (Fig. 3)

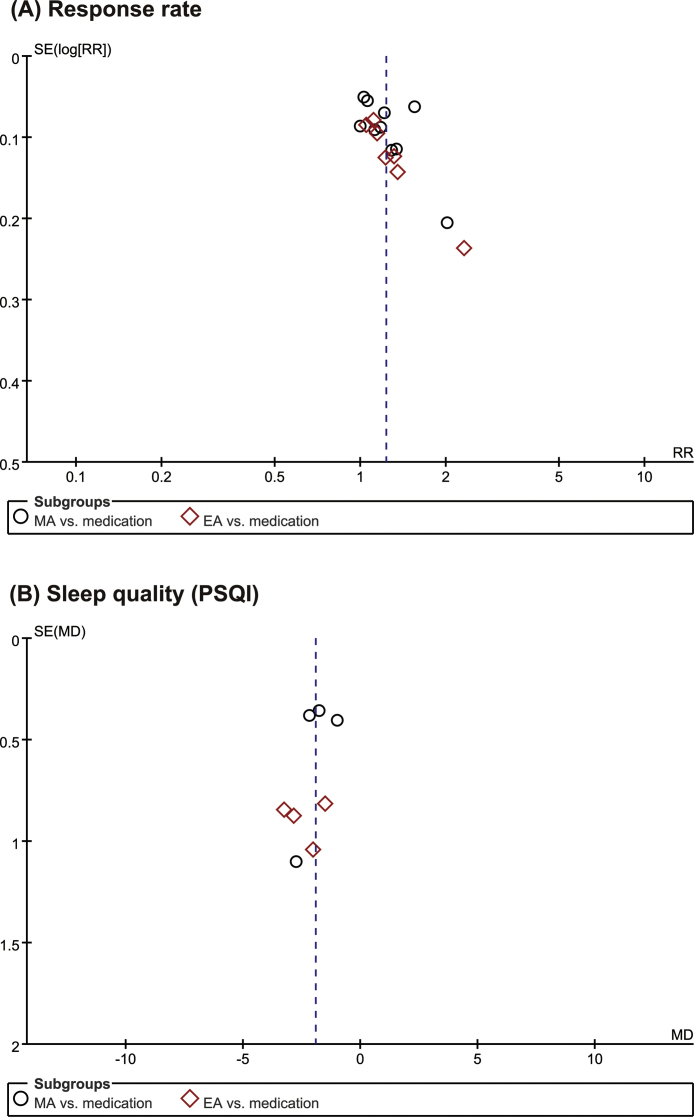

Fig. 4.

Funnel plot of (A) Response rate; (B) sleep quality (PSQI) for acupuncture vs. medications.

3.6. Publication bias

Meta-analysis of included 19 studies was comparing acupuncture with medication. There were high asymmetry means a large publication bias according to the funnel plot (Fig. 4).

3.7. Adverse effects

Only two studies reported adverse events. One study30 reported one needle-sickness-event in the treatment group, headaches (3 cases), dizziness (2 cases), nausea (1 case), and sleepiness (2 cases) in the medication group. The other one32 addressed occurrences of dry-mouth, fatigue, dizziness, and sleepiness in the only medication group, but did not report the precise number of adverse events.

4. Discussion

Our main results suggest that both of MA and EA used with PI may improve sleep duration, quality of subjective sleep, and daytime function of patients compared with medication. Acupuncture using PI is one type of individualized therapy and use in actual clinical setting. Our result may provide useful evidence to practitioners in clinical practice because this design may reflect acupuncture treatment in real world. But the question whether PI acupuncture is superior than non-PI acupuncture should be evaluated in the future studies. Compared with medication, acupuncture showed statistically significant effects and clinically meaningful (change over 3 points: higher than minimal clinically important difference (MCID)).25 However, overall risk of bias across the studies is high and the included studies were not compared with acupuncture without PI. Thus, it is difficult to derive definitive conclusions to the effectiveness of treatment with acupuncture using PI. Nevertheless, our result that acupuncture using PI had similar effects to medication is remarkable because many patients with chronic insomnia use medications seek acupuncture as a supplement or an alternative to their insomnia management and acupuncture using PI is widely used in actual clinical settings.

The overall risk of bias of included studies was high. Most studies only reported “randomization”, without describing the detailed methods of randomization or mentioning allocation concealment. Moreover, blinding was not carried out because sham-acupuncture was not used and control interventions were medication, potentially producing a high risk of bias.

A standardized pattern-diagnosis-criteria was not used and all studies also failed to provide information about number of patients in each PI. Additionally, each TCM pattern did not used standardization of the acupoints. We tried to analyze pattern diagnosis and treatment, which may cause the clinical heterogeneity but failed to do because of unfeasibility to resolve the clinical heterogeneity. In general, acupuncture studies have a high level of clinical heterogeneities including various types, definition, and lack of an unified acupuncture protocol, making the clinical trial very challenging. The PI is very subjective diagnosis, since it is based on only various signs and symptoms. Although there is a systematic review attempting to identify the commonly used TCM patterns,49 it is generally acceptable that standardizing pattern-diagnosis-treatment is not easy. In the future, nevertheless, we hope that further researches regarding a standardized pattern-diagnosis-criteria, acupuncture protocol, and the development of new clinical trial design should be accomplished by overcoming these heterogeneities.

The limitations of this review are as follows. Firstly, all studies included in our research aimed to compare the difference between acupuncture based PI and medication. Unlike the medication group, the acupuncture group was divided into several PIs. Therefore, it may not appropriate to make the direct comparison between the two groups. And we did not compare acupuncture using PI with standardized acupuncture without PI that is more appropriate control group. Therefore we wouldn't know which each PI is effective until now. In the future, well-designed RCTs that compare acupuncture using PI with standarized acupuncture are required. Secondly, we cannot excluded the possibility of publication bias considering that articles with negative results might not be published, effectiveness of those published should be scrutinized. Lastly, all studies included in our research were only those done in China. As previously reported,50 “the overall process of acupuncture involves touch, insertion and healing, consisting of multiple components, including somatosensory stimulation, treatment context and attention to needle-based procedures.” Social and cultural difference may have influnced the process of acupunture, therefore, global extrapolation of results (America, Europe and other regions) may not be possible.

In conclusion, our study showed that acupuncture using PI improve response rate and sleep quality compared with medication. However, the evidence is limited by high risks of bias across the included studies and clinical heterogeneity that not use a standardized pattern-diagnosis-criteria and acupoints. To investigate the effects of PI based treatment, specific pattern-diagnosis, diagnostic criteria and acupoints should be standardized across the studies. Finally, further research comparing acupuncture using PI to standardized acupuncture is needed.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Funding

This study was supported by the Traditional Korean Medicine R&D program funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI) [grant numbers HB16C0074].

Ethical statement

No ethical approval was required for this manuscript as this study did not involve human subjects or laboratory animals.

Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study will be made available on request.

Authors’ contributions

S.H. Kim, J.H. Jeong, J.H. Lim, and B.K. Kim conceived and designed the study concepts. S.H. Kim, J.H. Jeong, and J.H. Lim performed the literature search, data extraction, and risk of bias assessment. S.H. Kim and J.H. Jeong analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.H. Kim revised the manuscript. All authors agreed with the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2019.08.002.

Contributor Information

Sang-Ho Kim, Email: omed22@naver.com.

Jin-Hyung Jeong, Email: bada_jjh@naver.com.

Jung-Hwa Lim, Email: suede22@hanmail.net.

Bo-Kyung Kim, Email: npjolie@hanmail.net.

Supplementary material

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sateia M.J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014;146:1387–1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohayon M.M. Observation of the natural evolution of insomnia in the American General Population Cohort. Sleep Med Clin. 2009;4:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jsmc.2008.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spira A.P., Kaufmann C.N., Kasper J.D. Association between insomnia symptoms and functional status in U.S. Older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2014;69:S35–41. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbu116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sateia M.J., Buysse D.J., Krystal A.D., Neubauer D.N., Heald J.L. Clinical practice guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an american academy of sleep medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep. 2017;13:307–349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Institutes of Health National institutes of health state of the science conference statement on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults, June 13-15, 2005. Sleep. 2005;28:1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lader M., Tylee A., Donoghue J. Withdrawing benzodiazepines in primary care. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:19–34. doi: 10.2165/0023210-200923010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bertisch S.M., Wells R.E., Smith M.T., McCarthy E.P. Use of relaxation techniques and complementary and alternative medicine by American adults with insomnia symptoms: results from a national survey. J Clin Sleep. 2012;8:681–691. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frass M., Strassl R.P., Friehs H., Mullner M., Kundi M., Kaye A.D. Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: a systematic review. Ochsner J. 2012;12:45–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Susanne Hempel P., Taylor Stephanie L., Solloway Michelle R. Department of Veterans Affairs (US); USA: 2014. Evidence map of acupuncture. Evidence map of acupuncture. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pacific WROftW . 2007. WHO international standard terminologies on traditional medicine in the Western Pacific Region; p. 356. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yeung W., Chung K., Leung Y., Zhang S., Law A. Traditional needle acupuncture treatment for insomnia: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials (Structured abstract) Sleep Medicine [Internet] 2009;10:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.08.012. http://ac.els-cdn.com/S1389945708003651/1-s2.0-S1389945708003651-main.pdf?_tid=d378d16e-140d-11e7-b69e-00000aacb360&acdnat=1490743707_2d064edff085950f0d6a575f03bfb24d Available from: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.eproxy.pusan.ac.kr/o/cochrane/cldare/articles/DARE-12010001083/frame.html; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheuk D.K., Yeung W.F., Chung K.F., Wong V. Acupuncture for insomnia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005472.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shergis J.L., Ni X., Jackson M.L. A systematic review of acupuncture for sleep quality in people with insomnia. Complement Ther Med. 2016;26:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei X., Wei G., Chen X., Yue Z. Electro-acupuncture for primary insomnia and PSQI: a systematic review. J Clin Acupunct Moxibust. 2016;32:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fei W., Zhibin L., Ying Z. Curative effect of acupuncture therapy for insomnia of Yin deficiency type: a meta analysis. Mod J Integr Tradit Chin West Med. 2015;24:2174–2178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lathia A.T., Jung S.M., Chen L.X. Efficacy of acupuncture as a treatment for chronic shoulder pain. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:613–618. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cherkin D.C., Sherman K.J., Avins A.L. A randomized trial comparing acupuncture, simulated acupuncture, and usual care for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:858–866. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Macklin E.A., Wayne P.M., Kalish L.A. Stop Hypertension with the Acupuncture Research Program (SHARP): results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hypertension. 2006;48:838–845. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000241090.28070.4c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Association AP . American Psychiatric Association; Washington (DC): 1994. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV; p. 866. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medicine AAoS . 2nd ed. 2005. International classification of SleepDisorders: Diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, IL. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Organization WH . Tenth Revision; Geneva: 1992. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Psychiatry C.So. 3rd ed. Shandong Science Technology Press; Jinan: 2001. Chinese classification of mental disorders. (CCMD-3) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zheng X.Y., Zheng Y.Z., Zheng X. 2002. Guiding principles for clinical research on new drug of traditional Chinese Medicine: Beijing Ministry of Health of the People’ s Republic of China. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hughes C.M., McCullough C.A., Bradbury I. Acupuncture and refl exology for insomnia: a feasibility study. Acupunct Med. 2009;27:163–168. doi: 10.1136/aim.2009.000760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Higgins JPT GS . The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] [Google Scholar]

- 27.F.C. F. Case of insomnia treated with acupuncture. Guangming J Chin Med. 2012;27:320–321. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y., Feng H., Liu W.J. Regulation action and nerve electrophysiology mechanism of acupuncture on arousal state in patients of primary insomnia. Chin Acupunct Moxibust. 2017;37:19–23. doi: 10.13703/j.0255-2930.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan H., Li S.R., Shang X.Y., Xiang X.S. Clinical observation on insomnia treatment with acupuncture according to the differentiation of the disease. Sichuan J Tradit Chin Med. 2004;22:93–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su D., Zhao J., Jin H. The clinical efficacy of acupuncture at yuan-primary point and luo-connecting point of the heart meridian(HT) for the treatment of deficiency insomnia. J Clin Acupunt Moxibust. 2011;27:34–36. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X. 50 case of insomnia treated with acupuncture. J Clin Acupunt Moxibust. 2008;24:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J. 38 Case of insomnia treated with Heart-regulating and Mind-calming Acupunture. Shaanxi J Tradit Chin Med. 2014;35:1341–1342. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Z.Y., Liu X.G., Zhang W., Pi Y. Clinical observation of treating primary insomnia by Acupunture under the Theory of Liver Treatment. J Sichuan Tradit Chin Med. 2015;33:165–167. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei Y., Pang J. 42 Case of insomnia treated with regulating yin-yang heel meridian acupuncture. J External Therapy Tradit Chin Med. 2010;20:38–39. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang H.G., Li P.F. 35 Case of insomnia treated with ningxin anshen acupuncture. Shandong J Tradit Chin Med. 2013;32:185–186. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhao Z.L. Clinical observation on insomnia treatment by acupuncture therapy. Guangming J Chin Med. 2013;28:538–539. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Han Y., Zhang Z., Wang B. One hundred and thirty-three cases with insomnia treated by Needling Sishencong(EX-HN1) and Baihui(DU 20) Henan Tradit Chin Med. 2017;37:2194–2196. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bai W., Zhang Z. Clinical study of heel vessel acupuncture treating insomnia. Chin Arch Tradit Chin Med. 2011;29:413–414. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng M. Clinical observation on insomnia treated by acupuncture. J Pract Tradit Chin Med. 2015;31:1161–1162. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu D., Zhang T. Clinical observation on 60 Cases of insomnia treated by electro-acupuncture on head. Med J Chin People’s Health. 2010;22 1704+28. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ma D., Li G., Duan H. Clinical observation on 31 cases of insomnia treated by acupuncture. Guangming J Chin Med. 2006;21:25–26. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang W., Shi Y. Therapeutic observation on the treatment of insomnia with puncturing the governor and conception vessels. Shanghai J Acupunct Moxibust. 2013;32:277–279. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xing Y., Liu B., Yan C., Li J. Observations on the clinical efficacy of spoon needle electroacupuncture in treating insomnia. J Clin Acupunct Moxibust. 2010;26:9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu H., Liu Y. Clinical observation on insomnia treated by electroacupuncture used brain nerves method. J New Chin Med. 2014;46:173–174. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Y. Effect observation on treatment of primary insomnia by head of a pin electric stimulation. China Health Stan Manag. 2015:130–132. [Google Scholar]

- 46.P.F. L, X. L Clinical observation on insomnia treatment with acupuncture by dredging governor merdian for regulating mentality. J Clin Acupunt Moxibust. 2013;29:17–18. [Google Scholar]

- 47.China SAoTCMotPsRo . 1994. Standard of chinese traditional medicine diagnosis and treatment effect. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li S.Z., C.Q. L, W.L. L. People’s Health Publishing House; Beijing: 1995. Syndrome differentiation and treatment of Acupuncture and Moxibustion in clinical setting. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gadau M., Zhang S.P., Yip H.Y. Pattern differentiation of lateral elbow pain in traditional chinese medicine: A systematic review. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22:921–935. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kerr C.E., Shaw J.R., Conboy L.A., Kelley J.M., Jacobson E., Kaptchuk T.J. Placebo acupuncture as a form of ritual touch healing: A neurophenomenological model. Conscious Cogn. 2011;20:784–791. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study will be made available on request.