Abstract

Objective:

Women with congenital heart disease (CHD) are at increased risk of pregnancy complications and need information on safe, effective contraceptive methods to avoid unintended pregnancy. This systematic review examines evidence regarding safety of contraceptive use among women with CHD.

Methods:

The PubMed database was searched for any peer-reviewed articles published through April 2018 that included safety outcomes associated with reversible contraceptive methods among women with CHD.

Results:

Five articles met inclusion criteria: three studies comparing contraceptive users to nonusers and two noncomparative studies. Sample sizes ranged from 65 to 505 women with CHD. Two studies found a higher percent of thromboembolic complications among women with Fontan palliation or transposition of the great arteries using oral contraceptives. One study, among women with Fontan palliation, found no increased risk of thromboembolic complications between contraceptive users (not separated by type) and nonusers. Two studies found no endocarditis among intrauterine device users.

Conclusions:

There is a paucity of data regarding the safety of contraceptive methods among women with CHD. Limited evidence suggests an increased incidence of thromboembolic complications with use of oral contraceptives. Further studies are needed to evaluate contraceptive safety and quantify risk in this growing population. There is also limited data regarding the safety of contraceptive methods among women with CHD. Further information is needed to assist practitioners counseling women with CHD on safety of contraceptive methods.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, contraception, systematic review

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The population of women of child bearing age (18–44 years) in the United States living with congenital heart disease (CHD) was estimated at 340 000 in 2010 and continues to grow.1 Survival of individuals with CHD in all age groups has improved dramatically with advances in medical and surgical treatment. With enhanced survival, there is an increasing need to consider reproductive health concerns for women with CHD. Pregnancy among women with CHD confers an increased risk of maternal and infant morbidity and mortality.2 The incidence of unintended pregnancy in women with CHD is as high as 54%, compared to 45% in the general population, and a large proportion of women with CHD report using less effective methods (eg, barrier, withdrawal, and fertility awareness-based) which are associated with failure rates of ≥18 per 100 women per year, or no contraception.3–5 Therefore, it is important that women with CHD receive appropriate counseling regarding the safety and failure rates of contraception methods and the risks of unintended pregnancy.

Women with CHD are at elevated risk of certain adverse events relative to the general population and some contraceptive methods could further increase that risk to an unacceptable level or interact with disease progression. Potential risks associated with contraceptive use vary, depending on the type of contraceptive method and the severity of the CHD. For women with CHD, theoretical safety concerns with use of some hormonal contraceptive methods (particularly combined hormonal contraceptives, which contain estrogen plus progestin) include increased risk of arterial and venous thrombosis, fluid retention, and interactions with cardiovascular medications.6–10 Theoretical concerns with use of intrauterine devices (lUDs) include arrhythmia, vagal response, and infection leading to endocarditis, more likely at the time of insertion.11–13 However, little direct information exists on the safety of contraceptive methods for women with CHD. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review to assess whether, among women with CHD, adverse outcomes differed between women who used and did not use contraception, by type of method.

2 |. METHODS

This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.14

2.1 |. Literature search

The authors searched the PubMed database for all relevant peer-reviewed articles in any language published from database inception through April 2018. The search strategy included terms for CHD, including patent foramen ovale (PFO), lUDs, and hormonal contraceptives (Appendix 1). A search of scientific conference abstracts or unpublished literature was not performed.

2.2 |. Study selection

The key question of interest was whether, among women with CHD, adverse outcomes differed between women who used and did not use contraception. Articles examining the association between contraception safety and women with acquired cardiac disease, including ischemic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, or peri-partum cardiomyopathy, were excluded when the article did not report outcomes separately among women with CHD.15,16 Articles which only examined women with valvular heart disease were also excluded.

Articles were included in which women were using the following reversible contraceptive methods: copper lUDs, levonorgestrel IUDs, progestin-only implants, progestin-only injectables (including depot medroxyprogesterone acetate [DMPA] and norethisterone enanthate), progestin-only pills, combined oral contraceptives, combined hormonal patch, or combined vaginal ring. Articles reporting outcomes among women with CHD who underwent sterilization were excluded, as the potential risks of sterilization are often related to surgery and anesthesia rather than the contraceptive method. Barrier and other methods (eg, fertility awareness-based methods) were not included as their safety is not expected to be affected by CHD. Outcomes of interest included potential complications related to hormonal exposure (eg, thromboembolism or fluid retention) or IUD insertion (eg, infection, arrhythmia, or vagal responses).

To answer the key study question, study designs of interest included comparative studies (eg, randomized controlled trials, cohort, or case-control studies) examining adverse events among women with CHD using and not using contraception. However, noncomparative studies that reported adverse outcomes in the population of interest were also included, given the limited number of comparative studies published on contraceptive safety in women in CHD. Studies evaluating contraceptive use and risk of subsequent pregnancy with a fetus with CHD were excluded, as were review articles and case reports. Articles in languages other than English were translated if, on initial review, the article seemed to meet inclusion criteria. Titles and abstracts were reviewed independently by two coauthors (GA and SLF) to assess whether the articles met the inclusion criteria. Full articles were then reviewed by all authors to confirm inclusion. At each step, the authors discussed any disagreements and came to a decision on the article’s inclusion.

2.3 |. Study quality assessment and data synthesis

lnformation from each article was abstracted independently by two coauthors (GA and SLF) and confirmed by the third author (NT). The quality of each study was assessed using the United States Prevention Services Task Force (USPSTF) grading system.17 Based on the USPSTF criteria, authors graded each study’s research design (“I” for properly randomized controlled trials, “11–1” for controlled trials without randomization, “II-2” for cohort or case-control studies, and “II-3” for multiple time series with or without intervention) and its internal validity (“good,” “fair,” or “poor”). Several factors were considered which might impact study quality and potential biases, such as whether the study had clear descriptions of types of CHD and contraceptive methods and whether outcomes were self-reported or confirmed by physician or medical record review. Summary measures were not calculated due to heterogeneity in disease, contraceptive methods, and outcomes reported.

3 |. RESULTS

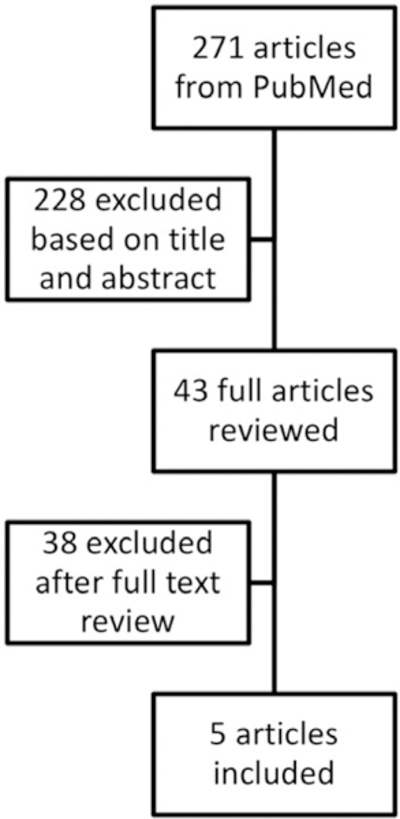

The search strategy identified 271 articles (Figure 1). After reviewing titles and abstracts, 43 full-length articles were reviewed and 5 met the inclusion criteria (Table 1).4,18–21 We excluded 38 articles because they did not include the population of interest, were review articles, or did not address the question of interest. We found no additional articles after reviewing references and review articles. There were three cohort studies,4,19,20 with data available to compare contraceptive users to nonusers, and two noncomparative studies18,21 reporting complications among contraceptive users without a comparison group of nonusers. The studies included women using a variety of reversible contraceptive methods.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart for inclusion of articles in systematic review

TABLE 1.

Studies addressing safety of contraceptive use among women with congenital heart disease

| Author, year published, country |

Study design, data collected |

Study population | Contraceptive method | Outcomes assessed and method of assessment |

Results | Strengths | Limitations | Quality | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miner,20 2017 | Retrospective cohort (for purpose of this review) | 505 women with CHD: 31 with Fontan physiology; 38 with | COC (N = 300) | Thrombotic history and oxygen saturation | Large number of women with CHD | All women receiving care at adult CHD specialty center | II–2, poor | ||||

| North America | 2011–2014 | D-transposition of the great arteries with atrial switch repair; 27 with ≥1 mechanical valves | POP (N = 108) | Self-reported surveys with medical record review | Using contraception | Total | Thromboembolic complication | ||||

| Outcomes not reported among women using other methods | N(%) | ||||||||||

| Self-report and medical record review | All women | Examined adverse events by type of CHD | |||||||||

| OC | 365 | 4% | Large majority white and highly educated | ||||||||

| CHD great complexity | 9% | ||||||||||

| CHD less complexity | 1% | 98% response rate | |||||||||

| Fontan | 31 | Differences in characteristics between groups not reported | |||||||||

| OC ever use | 39% | Outcomes verified by medical record review | |||||||||

| OC use at time of event | 18 | 5 (28%) (all in COC users) | |||||||||

| Never-users | 17% | Contraceptive use self-reported | |||||||||

| Transposition great arteries | 38 | Small number of OC users by CHD type | |||||||||

| OC | 31 | 4 (13%) (POP, COC and unknown) | |||||||||

| Never-users | 0 (0%) | Timing of OC use unclear | |||||||||

| Mechanical valves | 27 | Statistical testing to compare OC users to non-OC users not performed | |||||||||

| OC | 20 | 0 (0%) | |||||||||

| *P = .003 for great complexity vs less complexity | |||||||||||

| Pundi,4 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 138 women with Fontan palliation and available contraceptive information | CHC, barrier, or sterilization (12%) (N = 17 using COCs) | Thromoembolic complications (DVT, PE, or stroke) |

Using contraception |

Total |

Thromboembolic complication |

Large number of women with CHD | Follow-up time not reported | II-2, poor | |

| N | |||||||||||

| Yes | 77 | 6 (8%) | |||||||||

| No | 61 | 7 (11%) | |||||||||

| United States | 1973–2012 | Follow-up: not reported | POP (1%) | Endocarditis | P = .46 for use vs nonuse | Contraceptive information obtained from medical records | Low response rate (48%) | ||||

| DMPA (8%) | Self-reported on mailed questionnaires | PE in 1/17 women using COCs | Exact number of women using different methods not reported | ||||||||

| IUD (type not specified) (7%) | No reports of endocarditis with IUD use | IUD type not specified | |||||||||

| Contraceptive information from medical records | Outcomes self-reported | ||||||||||

| Complications not reported by contraceptive type | |||||||||||

| Tanislav,19 2011 | Retrospective cohort | 65 women with cryptogenic stroke or TIA and patent foramen ovale | OC (not defined) (N = 9) | Silent PE on ventilation scintigraphy scan | Percent PE among OC users and nonusers (calculated for purpose of this review): | PE diagnosis made by two experts blinded to clinical data | Only patients with stroke or TIA included, results not generalizable | II-2, poor | |||

| Germany | Years of data collection not reported | Length of follow-up not reported | OC use | Total | PE | No PE | OC use obtained from medical records | Small number of women using OCs | |||

| N(%) | N(%) | Type and timing of OC use not reported | |||||||||

| Yes | 9 | 6 (67%) | 3 (33%) | ||||||||

| No | 56 | 19 (34%) | 37 (66%) | No statistical comparison of users vs nonuser | |||||||

| Pijuan-Domènech,18 2013 | Noncomparative with retrospective and prospective components | 237 women with CHD: 219 biventricular CHD and 18 univentricular heart | 79 women who previously used CHCs | Any cardiovascular or gynecologic complications | Retrospective: 3 undefined neurological events during previous CHC use (3.8% of CHC users) | Large number of women with CHD | Neurological events not described | 11–3, poor | |||

| Spain | 2007–2010 | Follow-up: mean 385 days | 107 women who started POPs (desogestrel) and were followed prospectively | Confirmed by examination at 6 months, confirmation beyond 6 months not specified | Prospective: No cardiac or thrombolytic events with POCs | Contraceptives during study period provided by clinic | Timing of CHC use and events not reported | ||||

| At end of follow-up: | Long follow-up | No comparison group of nonusers | |||||||||

| POP (N = 63) | Pattern of POC use not reported | ||||||||||

| Rabajoli,211992 | Retrospective noncomparative | 108 women with CHD: 53 with cyanotic heart disease, 23 left-right shunt, 32 withoutflow tract obstruction | OC (not defined in all but one) (N = 13) | Cardiovascular or thromboem-boliccomplications | Pulmonary hypertension confirmed by cardiac catheteriza-tion in one COC user with atrial septal defect | Contraceptive use and outcomes obtained from medical records | Types of OCs and IUDs not reported | 11–3, poor | |||

| Italy | 1980–1990 | Follow-up: 10 years | IUD (type not specified) (N = 18) (all received antibiotics with insertion) | Infection | No hypertension or thromboembolic disease | Long follow-up | Small numbers of women using contraceptive | ||||

| Medical record review | Local infection in one IUD user | ||||||||||

| No endocarditis in IUD users | Timing of contraceptive use relative to outcomes not specified | ||||||||||

| No comparison group of nonusers | |||||||||||

| Infection criteria not defined | |||||||||||

Abbreviations: CHC, combined hormonal contraceptive; CHD, congenital heart disease; COC, combined oral contraceptive; DM PA, depot medroxyprogesterone acetate; DVT, deep venous thrombosis; IUD, intrauterine device; OC, oral contraceptive; PE, pulmonary embolism; POC, progestin-only contraceptive; POP, progestin-only pill; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

A retrospective cohort study, conducted from 2011 to 2014, reported on 505 women with a variety of types of CHD attending 9 adult CHD clinics in North America.20 Overall, 4% of women experienced a thromboembolic event while using oral contraceptives, with a higher percentage among women with complex CHD (9%) than among women with less complex CHD (1%, P value for comparison .003). Among 31 women with Fontan physiology, 39% of women who had ever used oral contraceptives and 28% of current oral contraceptive users experienced a thromboembolic event (all in women using combined oral contraceptives), while 17% of never-users experienced an event. Among 38 women with D-transposition of the great arteries, 13% of current users (combined and progestin-only pills) experienced a thromboembolic event, compared with no women in the never-user group.

A retrospective cohort study conducted in the United States using data from 1973 to 2012 reported on 138 women with Fontan palliation and available contraceptive information.4 Among these women, 12% (17) were using combined hormonal contraceptives, barrier methods, or sterilization (not further differentiated), 8% (11) were using DMPA, 7% (10) were using lUDs (type not specified), and 1% (2) were using progestin-only pills.

Reported thromboembolic complications were similar between women using any type of contraception compared to women using no contraception (8% vs 11%, P = .46). Of these events, pulmonary emboli (PE) occurred in 17 women using combined oral contraceptives; however, the authors did not report which contraceptive methods were used by the remaining women who experienced thromboembolism. There were no reports of complications, including endocarditis, among women using lUDs. Authors did not report year of contraceptive use or timing relative to thromboembolism occurrence.

A retrospective cohort study conducted in Germany (years of data collection not reported, published 2011) reported on 65 women with a PFO (diagnosed by echocardiography) and history of cryptogenic stroke.19 The women were evaluated for silent PE using ventilation perfusion scintigraphy. Nine of the 65 women reported taking oral contraceptives (type not reported). Silent PE was found in 6 of 9 oral contraceptive users (67%) and 19 of 56 nonusers (34%); these percentages were not reported by the authors but were hand-calculated from published data for the purpose of this review and direct statistical comparison was not reported.

A noncomparative study was conducted in Spain from 2007 to 2010 of 237 women with CHD (92% biventricular CHD, 66% New York Heart Association Heart functional class I) referred for preconception counseling at a CHD clinic.18 This study had a retrospective and prospective component. The retrospective component included data abstracted from medical records. Of 79 women who reported previous use of combined hormonal contraceptives (combined oral contraceptives and patch), 3 (3.8%) reported a thromboembolic event while using the combined hormonal contraceptive. Among 145 women who inquired about contraception in the CHD clinic, 107 began desogestrel progestin-only pills. At approximately 1 year of follow-up, 63 were continuing to use progestin-only pills, 16 were using implants or progestin lUDs, and the remainder were using barrier or no methods. No cardiac or thrombotic events were reported among the 107 women initially started on the desogestrel progestin-only pill.

A retrospective noncomparative study conducted in Italy from 1980 to 1990 reported on 108 women with CHD (53 with cyanotic disease of which 8 had Eisenmenger syndrome, 23 with left-right shunt, and the remainder with outflow tract obstruction).21 Over half had undergone cardiac surgery, 70% of which were considered “radical corrective surgeries,” which was not further defined. Review of medical records during a 10-year period identified 13 women using oral contraceptives (type reported for 1 woman only) and 18 women using lUDs (type not reported). One woman with atrial septal defect developed pulmonary hypertension (confirmed with cardiac catheterization) while using combined oral contraceptives. No women using oral contraceptives developed hypertension or thromboembolic disease. One woman with unspecified CHD developed a local infection (not further defined) while using an IUD. No endocarditis occurred in lUD users.

4 |. DISCUSSION

4.1 |. Summary

Five studies, two from North America and three from Europe, provide limited information on complications among women with CHD using contraception. Two of three comparative studies found a higher percent of thromboembolic complications among women with Fontan palliation or transposition of the great arteries using oral contraceptives than among women not using oral contraceptives; however, statistical testing was not reported for these comparisons.19,20 One of these studies found a higher percent of thromboembolic conditions in women with more severe CHD compared with mild CHD.20 In contrast, one study of women with Fontan palliation found no increased risk of thromboembolic complications among women using contraception (not separated) compared with nonusers.4 Two studies found no endocarditis among IUD users.4,21

This body of evidence is extremely limited. All studies were rated as poor quality. Studies had small numbers of women with CHD or using contraception. Two studies did not have a comparison group of nonusers18,21 and two others did not report statistical comparisons between users and nonusers.19,20 Two studies did not report outcomes by specific type of contraception, but rather grouped all methods together.4,19 In three studies, the temporal sequence of contraceptive use and the adverse event was unclear.18–20

4.2 |. Potential risks

Given the lack of high-quality direct evidence regarding safety of contraceptives among women with CHD, it is important to consider whether there are any theoretical health concerns with use of contraception, beyond that of the general population. Contraceptive use could further increase risks of certain adverse events in women with CHD to an unacceptable level or could interact with CHD disease process or treatment to introduce new risks. Concerns will vary by type of CHD and contraceptive method, but may include an increased risk of thrombosis, endocarditis after IUD insertion, heart failure, and arrhythmias, beyond that of the general population of contraceptive users, as well as cardiac-related drug interactions.

Women with certain cardiac conditions are at elevated risk for venous and arterial thrombosis, including women with pulmonary artery hypertension, Fontan repair, atrial fibrillation, mechanical heart valves, and significant ventricular dysfunction.6,22 It is well established that combined oral contraceptive use by women in the general population increases the risk of venous and arterial thrombosis compared with nonuse, by approximately threefold for venous thromboembolism (VTE), twofold for ischemic stroke, and 1.6-fold for myocardial infarction (MI).7,23 The risk of arterial thrombosis is also increased among women with hypertension who use combined oral contraceptives.24 These effects are largely due to impacts of estrogen on the clotting system but may also be impacted by different progestin types.25 Studies have generally not demonstrated an elevated risk of venous or arterial thrombosis with use of progestin-only contraceptives by women in the general population compared with nonuse.26 A few studies have found an elevated risk of VTE with DMPA; however, there is no evidence examining these associations among women with thrombosis risk factors.26 It is unknown whether estrogen affects the mechanisms that lead to thrombosis among women with CHD, but combined hormonal contraceptives might further increase the risk of thrombosis in these women.

Certain CHD are associated with endocarditis, including CHD repaired with prosthetic cardiac valves and prior history of infective endocarditis.12 Theoretically, initiation of an IUD in these individuals could lead to disseminated infection and endocarditis through bacterial seeding and spread. However, the incidence of pelvic infection among women initiating IUDs is very low and antibiotic prophylaxis does not impact risk of pelvic inflammatory disease.13,27 Additionally, antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended prior to genitourinary procedures, given no evidence of an association between genitourinary procedures and endocarditis.28

Heart failure secondary to ventricular dysfunction can be a serious sequela of CHD. Fluid retention, if exacerbated by hormonal contraceptives, could initiate or worsen heart failure. However, studies have shown mixed results on blood pressure and fluid effects in women exposed to contraceptive or noncontraceptive doses of hormones.29–32 Overall, effects on fluid balance related to hormonal contraceptives are likely of minimal clinical significance.

Some women with CHD are at risk for arrhythmias, including women with Fontan palliation, atrial dilation or cardiac dysfunction.11 While there is no evidence demonstrating an increased incidence of adverse events with IUD insertion in women with CHD, some studies have reported arrhythmia in healthy women during and following IUD insertion or while using hormonal contraceptives. However, these instances are likely uncommon and the clinical significance is unknown. A small percentage of women experience vasovagal responses during IUD insertion. Estimates report less than 2% incidence of syncope and a range of 2%−30% incidence of bradycardia, with higher incidences found during insertion of older large and rigid IUDs.33,34 These symptoms may be worsened in the setting of pulmonary artery hypertension or Fontan palliation.6,35

Women with CHD may use teratogenic medications, such as certain antihypertensives, underscoring the need for effective contraception. However, some cardiac medications, such as bosentan and warfarin, may interact with hormonal contraceptives, thereby potentially decreasing effectiveness of either drug. Bosentan used in the treatment of pulmonary artery hypertension induces CYP3A4 activity and could decrease concentrations of contraceptive hormones8,9; however, impact on contraceptive effectiveness is unknown. Warfarin may interact with hormonal contraceptives, leading to either decreased or increased warfarin requirements, although this information is limited to pharmacokinetic studies, case reports and case series and clinical implications are unclear.10,36

When considering the risk/benefit ratio for contraception use in women with CHD, it is important to factor the risk of pregnancy. Potential complications of contraception may be outweighed by the significant morbidity and mortality faced by women with certain CHD who become pregnant, such as those with pulmonary artery hypertension.37 Highly effective contraception, such as lUDs, implants, or sterilization, are associated with pregnancy rates of less than 1 per 100 users and may be preferable for women with these diseases who wish to avoid pregnancy. However, surgical risk should be considered in women who desire sterilization. In addition, some women with CHD may benefit from noncontraceptive uses of some methods of contraception, such as reduced bleeding among women with abnormal uterine bleeding using anticoagulants.38

4.3 |. Published recommendations

The safety of different contraceptives likely varies widely among women with CHD, given the range of severity of CHD. Despite this heterogeneity, the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association,11 the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,12 the European Society of Cardiology39 and expert groups from Canada6 and the United Kingdom37 have published recommendations for use of contraception among women with CHD based on expert opinion. One published recommendation suggests that women with simple CHD lesions are likely at no increased risk compared with the general population.6 However, all recommend that women with CHD at high risk for thrombosis avoid combined hormonal contraceptives.6,11,12,37 Some recommend avoidance or caution and careful monitoring of IUD insertion in women for whom a vagal response would be poorly tolerated.6,12,37 Two also recommend caution with use of progestin-only contraceptives among patients with heart failure due to concern for fluid retention.6,11 Two acknowledge uncertainty regarding risk of endocarditis with IUD insertion and recommend individualized management.11,12 The US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use includes recommendations for safe use of contraception among women with certain comorbid or analogous medical conditions (eg, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, peri-partum cardiomyopathy, and deep venous thrombosis/pulmonary embolism), which might be considered when counseling women with CHD.40

4.4 |. Conclusions

In conclusion, this review identified limited Level II-2 to II-3 poor-quality evidence on contraceptive safety in women with CHD. Several published guidelines and expert reviews provide information on theoretical risks of contraceptive methods in women with specific types of CHD. Collaboration and communication between a woman’s cardiologist and contraceptive provider may be helpful in providing comprehensive counseling about potential risks and benefits of all contraceptive methods compared to risk of unintended pregnancy. Future studies evaluating contraceptive safety among women with CHD would help quantify the risks, beyond that of the general population.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Kathryn Curtis, PhD, for her valuable input on the manuscript.

Funding information N/A; All work was done as part of employment with the US federal government.

APPENDIX 1

Search strategy for congenital heart disease or patent foramen ovale and reversible contraceptives

((((((((((((((“Contraceptives, Oral, Combined”[Mesh] OR “Contraceptives, Oral”[Mesh] OR “Contraceptives, Oral, hormonal”[Mesh] OR “Contraceptives, Oral, Combined”[Pharmacological Action]) OR (contracept* AND (oral OR pill OR tablet)) OR ((combined hormonal) OR (combined oral) AND contracept*) OR (contracept* AND (ring OR patch)) OR “ortho evra” OR NuvaRing) OR (progestin* OR progestins[MeSH] OR Progesterone[MeSH] OR progesterone OR progestogen* OR progestagen* OR “Levonorgestrel”[Mesh] OR Levonorgestrel OR “Norgestrel”[Mesh] OR norgestrel OR etonogestrel AND contracept*) OR dmpa OR “depo medroxyprogesterone” OR “depo provera” OR “net en” OR “norethisterone enanthate” OR “norethindrone enanthate” OR (contracept* AND (inject* OR implant)) OR ((levonorgestrel OR etonogestrel) AND implant) OR implanon OR nex- planon OR jadelle OR norplant OR uniplant OR sino-implant OR (levonorgestrel-releasing two-rod implant) OR (“Intrauterine Devices, Medicated”[Mesh] OR ((intrauterine OR intra-uterine) AND (device OR system OR contracept*)) OR IUD OR IUCD OR IUS OR mirena OR Skyla OR paragard OR “Copper T380” OR CuT380 OR “Copper T380a” OR “Cu T380a”))) AND Humans[Mesh])) AND ((((((((((((“heart defects, congenital”[MeSH Terms] OR (“heart”[All Fields] AND “defects”[All Fields] AND “congenital”[All Fields]) OR “congenital heart defects”[All Fields] OR (“heart”[All Fields] AND “defects”[All Fields] AND “congenital”[All Fields]) OR “heart defects, congenital”[All Fields]))) OR ((“congenital”[All Fields] AND “heart”[All Fields] AND “disease”[All Fields]) OR “congenital heart disease”[All Fields]))) OR ((“pediatric”[All Fields] AND “cardiology”[All Fields]) OR “pediatric cardiology”[All Fields])))) AND Humans[Mesh])) OR ((((“heart septal defects, atrial”[MeSH Terms] OR (“heart” AND “septal” AND “defects” AND “atrial”) OR “atrial heart septal defects” OR (“atrial” AND “septal” AND “defect”) OR “atrial septal defect”)) AND (“foramen ovale, patent”[MeSH Terms] OR (“foramen” AND “ovale” AND “patent”) OR “patent foramen ovale” OR (“patent” AND “foramen” AND “ovale”)))))) AND Humans[Mesh]))).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

DISCLAIMER

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gilboa SM, Devine OJ, Kucik JE, et al. Congenital heart defects in the United States: estimating the magnitude of the affected population in 2010. Circulation. 2016;134:101–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drenthen W, Pieper PG, Roos-Hesselink JW, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease: a literature review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:2303–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindley KJ, Madden T, Cahill AG, Ludbrook PA, Billadello JJ. Contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy in women with congenital heart disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:363–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pundi KN, Pundi K, Johnson JN, et al. Contraception practices and pregnancy outcome in patients after Fontan operation. Congenit Heart Dis. 2015;11:63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:843–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silversides CK, Sermer M, Siu SC. Choosing the best contraceptive method for the adult with congenital heart disease. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2009;11:298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peragallo Urrutia R, Coeytaux RR, McBroom AJ, et al. Risk of acute thromboembolic events with oral contraceptive use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:380–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srinivas NR. Clinical drug-drug interactions of bosentan, a potent endothelial receptor antagonist, with various drugs: physiological role of enzymes and transporters. Gen Physiol Biophys. 2016;35:243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Giersbergen PL, Halabi A, Dingemanse J. Pharmacokinetic interaction between bosentan and the oral contraceptives norethisterone and ethinyl estradiol. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2006;44:113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zingone MM, Guirguis AB, Airee A, Cobb D. Probable drug interaction between warfarin and hormonal contraceptives. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:2096–2102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warnes CA, Williams RG, Bashore TM, et al. ACC/AHA 2008 guidelines for the management of adults with congenital heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines on the management of adults with congenital heart disease). Circulation. 2008;118:e714–e833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Contraceptive Choices for Women with Cardiac Disease. 2014. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceu-guidance-contraceptive-choices-for-women-with-cardiac/. Accessed March 6, 2018.

- 13.Farley TM, Rosenberg MJ, Rowe PJ, Chen JH, Meirik O. Intrauterine devices and pelvic inflammatory disease: an international perspective. Lancet. 1992;339:785–788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avila WS, Grinberg M, Melo NR, Aristodemo Pinotti J, Pileggi F. Contraceptive use in women with heart disease. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1996;66:205–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suri V, Aggarwal N, Kaur R, Chaudhary N, Ray P, Grover A. Safety of intrauterine contraceptive device (copper T 200 B) in women with cardiac disease. Contraception. 2008;78:315–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris RP, Helfand M, Woolf SH, et al. Current methods of the US Preventive Services Task Force: a review of the process. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20:21–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pijuan-Domenech A, Baro-Marine F, Rojas-Torrijos M, et al. Usefulness of progesterone-only components for contraception in patients with congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:590–593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanislav C, Puille M, Pabst W, et al. High frequency of silent pulmonary embolism in patients with cryptogenic stroke and patent foramen ovale. Stroke 2011;42:822–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miner PD, Canobbio MM, Pearson DD, et al. Contraceptive practices of women with complex congenital heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2017;119:911–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rabajoli F, Aruta E, Presbitero P, Todros T. Risks of contraception and pregnancy in patients with congenital cardiopathies. Retrospective study on 108 patients. G Ital Cardiol. 1992;22:1133–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindley KJ, Conner SN, Cahill AG, Madden T. Contraception and pregnancy planning in women with congenital heart disease. Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2015;17:50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roach RE, Helmerhorst FM, Lijfering WM, Stijnen T, Algra A, Dekkers OM. Combined oral contraceptives: the risk of myocardial infarction and ischemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;CD011054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curtis KM, Mohllajee AP, Martins SL, Peterson HB. Combined oral contraceptive use among women with hypertension: a systematic review. Contraception. 2006;73:179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tchaikovski SN, Rosing J. Mechanisms of estrogen-induced venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2010;126:5–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tepper NK, Whiteman MK, Marchbanks PA, James AH, Curtis KM. Progestin-only contraception and thromboembolism: a systematic review. Contraception. 2016;94:678–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grimes DA, Schulz KF. Antibiotic prophylaxis for intrauterine contraceptive device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001:CD001327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116:1736–1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stachenfeld NS. Sex hormone effects on body fluid regulation. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2008;36:152–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Nadai MN, Nobre F, Ferriani RA, Vieira CS. Effects of two contraceptives containing drospirenone on blood pressure in normotensive women: a randomized-controlled trial. Blood Press Monit. 2015;20:310–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kharbanda EO, Parker ED, Sinaiko AR, et al. Initiation of oral contraceptives and changes in blood pressure and body mass index in healthy adolescents. J Pediatr. 2014;165:1029–1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roos-Hesselink JW, Cornette J, Sliwa K, Pieper PG, Veldtman GR, Johnson MR. Contraception and cardiovascular disease. Eur Heart J. 2015;36:1728–1734, 34a-34b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall AM, Kutler BA. Intrauterine contraception in nulliparous women: a prospective survey. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2016;42:36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Farmer M, Webb A. Intrauterine device insertion-related complications: can they be predicted? J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2003;29:227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olsson KM, Jais X. Birth control and pregnancy management in pulmonary hypertension. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;34:681–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Culwell KR, Curtis KM. Use of contraceptive methods by women with current venous thrombosis on anticoagulant therapy: a systematic review. Contraception. 2009;80:337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thorne S, Nelson-Piercy C, MacGregor A, et al. Pregnancy and contraception in heart disease and pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Fam Plann Reprod Health Care. 2006;32:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Maas AH, Euler M, Bongers MY, et al. Practice points in gynecardiology: abnormal uterine bleeding in premenopausal women taking oral anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy. Maturitas. 2015;82:355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baumgartner H, Bonhoeffer P, De Groot NM, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J. 2010;31:2915–2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]