Abstract

Within the last two decades, there have been multiple reports of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated smooth muscle tumors in immunocompromised patients. This includes HIV-infected patients, post-transplant patients, and patients with congenital defects of their immune systems. Here we report the case of a 24-year-old African American female with congenital HIV presenting with progressive lower extremity weakness, constipation, aching pain in her shoulders, and subcostal anesthesia. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a large circumferential lesion extending from T1-T3 and a smaller left paraspinal lesion at C6-C7. The T1-T3 mass was excised via a right-sided costotransversectomy with laminectomy and fusion from T1-T3. Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was started postoperatively, and adjuvant radiotherapy was initiated but patient was lost to follow-up. Surgical pathology demonstrated a smooth muscle tumor diffuse nuclear positivity for EBV-encoded small RNA 1 by in situ hybridization. Although eight studies have reported HIV patients with EBV-associated smooth muscle tumors of the spine, to the author’s knowledge, this is the first review comprised solely of patients with spinal involvement with the addition of our patient case.

Keywords: Epstein-Barr virus, Smooth muscle tumor, Spine, HIV, Rare, Case report

1. Introduction

Within the last two decades, there have been multiple reports of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated smooth muscle tumors (SMTs) in immunocompromised patients. This includes HIV-infected patients, post-transplant patients, and patients with congenital immunological defects. In HIV-positive cases, patients are most commonly young adults with congenitally-acquired HIV infections and present with tumors in any of a variety of locations. Most commonly, these lesions are observed in the genitourinary or gastrointestinal tracts; however previous reports have documented spinous pathology [1]. Due to the rarity of EBV-associated SMTs, there is no established standard of care or tumor grading system. Hererin, we present a rare case of an HIV-infected patient with a primary EBV-associated SMT of the spinal column treated with surgical resection.

2. Case report

A 24-year-old African American female with a history of congenital HIV infection (off antiretroviral therapy for > 5 years) presented to the emergency room after one month of progressive lower extremity weakness, constipation, aching pain in bilateral shoulders, and numbness below T8 dermatome.

An MRI demonstrated a T1-T3 circumferential lesion extending through the T2-T3 right neural foramina and compressing the spinal cord (Fig. 1). A small lesion was also observed in the left paraspinal soft tissues extending through the left C6-C7 neural foramen, however, it demonstrated no evidence of neural element compression. The patient underwent a T1-T3 laminectomy for decompression and tumor excision, which was followed by stabilization with T1–3 pedicle screw fixation for stabilization (Fig. 2). She was subsequently admitted to the AIDS inpatient unit, where she started on elvitegravir-cobicistat-emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide for her HIV infection (Absolute CD4 count, 2 cells/ mm3; HIV RNA level, 292,000 copies/mL; no evidence of drug resistance). The patient also initiated adjuvant radiotherapy for the residual tumor, but was lost to follow-up before the course could be completed.

Fig. 1.

Preoperative imaging demonstrating a right paraspinal soft tissue mass extending into the neural foramina from T1-T3, leading to extradural spinal cord compression and leftward shift. A. Sagittal T2-weighted MRI. B. Axial T1-post contrast MRI at the T2 vertebral body level.

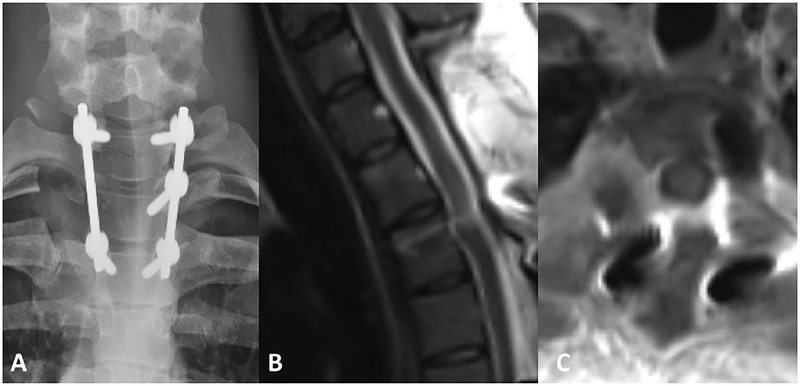

Fig. 2.

Post-operative imaging demonstrating spinal cord decompression and posterior instrumentation from T1-T3 via a right-sided costotransversectomy approach. A. AP radiograph B. Sagittal T2-weighted MRI C. Axial T1 post-contrast MRI at the level of the T2 vertebral body.

A tumor specimen obtained during the surgery was sent for pathological analysis. The specimen was found to stain positive for desmin, smooth muscle actin (weak), collagen IV, p16, p53 (scattered), and S-100 protein (focal), and negative for SOX-10 and CD34. Although her quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for plasma EBV DNA was negative (limit of detection 50 EBV genome copes), in situ hybridization for EBV-encoded small RNA 1 (EBER1) was diffusely positive in the tumor. A Ki-67 immunostain demonstrated focally increased proliferation index. A mitotic count yielded low mitotic activity. Histopathological slides are seen in Figs. 3 and 4.

Fig. 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides of EBV-associated smooth muscle tumor. Dilated vessels (A, 40×) and patchy regions of collagenous stroma (B, 40×) were noted, mimicking a solitary fibrous tumor. The neoplastic cells were spindled with elongated, blunt-ended nuclei, inconspicuous nucleoli, and moderate amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. The tumor demonstrated short, sweeping fascicles (D, 100×) with interspersed thick and thin collagen strands (“shredded carrot collagen”) (E, 200×) and variable regions of cellularity. In the more cellular regions (C, 40×), there was mild to moderate nuclear pleomorphism and an increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio (F,400×). Mitotic figures were rare (<1 per 10 HPF) throughout, and tumor necrosis was notably absent.

Fig. 4.

EBV-associated smooth muscle tumor immunophenotypic profile (100×). A) Smooth muscle actin (weakly positive), B) desmin (patchy positivity), C) collagen IV (positive), D) S-100 protein (patchy positivity), E) SOX-10 (negative), F) p16 (positive), and G) p53 (scattered positivity). A Ki-67 immunostain (H) demonstrated focally increased proliferation index (5%–10%) and in situ hybridization for EBV (EBV-encoded RNA 1) was diffusely positive (I). STAT-6 and CD34 immunostains were negative (not shown).

3. Discussion

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-associated smooth muscle tumors (SMTs) have been reported throughout the last four decades in immunodeficient patients [1,2]. The first reported case of an SMT in the presence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was described in 1990 by Chadwick et al. who observed leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas in the lungs and gastrointestinal (GI) tracts of three HIV-infected children [3]. Five years later, Lee et al. reported similar tumors composed of smooth muscle in the lungs, livers, and GI tract of three children who were being immunosuppressed after organ transplants [4]. After in situ hybridization, they found clonal EBV DNA in all tumor specimens, leading to the first association of EBV with SMTs in immunosuppressed patients [4]. These studies suggested a link between SMTs and EBV in patients with inhibited immune systems [4,5]. A subsequent study by Dekate and Chetty found that the EBV-associated SMTs occur most often in HIV-positive patients, similar to our current patient, followed by immunosuppressed post-transplant patients, and lastly, patients with congenital immunodeficiencies other than HIV [1].

Although there is a clear association between EBV and these tumors, the pathogenesis has yet to be fully explained [1]. EBV is separated into two strains that thrive in different atmospheres. Type 1 infects immunocompetent individuals and has been found in both Hodgkin and Burkitt lymphomas. Type 2 EBV, by contrast, is known to infect immunodeficient hosts using the CD21 receptor found on B cells, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of smooth muscle tumors such as the one reported here [1,6]. Evidence for this comes from Jenson et al., who analyzed the smooth muscle cells from EBV-associated SMTs in an AIDS patient and discovered that the majority of tumor cells expressed CD21 [7]. By contrast, SMTs observed in post-transplant immunosuppressed patients do not appear to express CD21, suggesting that the mechanism of EBV infection may differ based on the etiology of a patient’s immunodeficiency [4,8–10].

EBV-associated SMTs have often been labeled as either leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas (LMS). In a study of 64 patients with EBV-associated SMT, Purgina et al. found that 71% of patients had pathology consistent with “malignant” LMS [8]. On average, these patients had CD4 counts that were 34% higher and presented 14.2 months later, compared to the patients with leiomyoma-type histology [8]. Despite these differences, the classification of EBV-SMT as either leiomyosarcoma or leiomyoma is inconsistent across the literature reports, as no universally-accepted guidelines have been established for the diagnosis of these lesions [9–12]. Furthermore, reports exist documenting leiomyoma-type EBV-associated SMTs that demonstrate tumor dissemination and survival times that are more consistent with malignant leiomyosarcoma. This suggests that tumor pathology may not be predictive of patient outcome and may not have a role in guiding treatment [6]. Because of this lack of association between histology and prognosis, we elected not to classify this patient’s tumor as either leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma.

In the majority of affected HIV patients, EBV-associated SMT presents as a multifocal pathology, with lesions being observed in numerous locations, including tissues with low smooth muscle content, such as the central nervous system (CNS) [6,13–21]. In non-HIV cases, the majority of SMTs have been found in genitourinary and gastrointestinal tracts. However, a report by Suankratay et al. suggested that extra-GI, extra-GU lesions may be more common in this population [18]. They observed extra-GI, extra-GU lesions in all nine patients, with tumor locations including epidural CNS sites, vocal cords, adrenal glands, abdominal wall, iris, liver, lung, orbit, and the thigh [18]. This multifocal presentation in HIV-positive patients is suggestive of metastasis, however, a recent report by Deyrup et al. suggests that this is not the case [6]. In their paper, the authors analyzed the lesions from 19 patients with multifocal disease. They found that in each case, the tumors from these patients were clonally distinct, suggesting that the multifocal disease results from multiple primary tumors instead of a metastatic process [6]. Therefore, the second tumor found in the C5 level paraspinal muscles of our patient was assumed to be a second primary EBV-associated SMT instead of a metastasis. However, this mass was not biopsied to confirm this.

As mentioned previously, HIV-related EBV-associated SMTs have a relative predilection for CNS involvement, as in our patient [6,8,13–19]. A review of the literature yielded eight studies documenting patients with spinal cord involvement totaling 11 patients, who are summarized in Table 1 [6,13–19]. The majority of patients were young adults (mean age 34) with chronic HIV infections, with a mean time between HIV diagnosis and EBV-associated SMT diagnosis of 48 months. The majority of patients presented with neurologic deficits, most commonly extremity weakness (70%), sensory loss (40%), and pain (50%) [13,16–18].

Table 1.

Previous clinical data of HIV-infected patients with EBV-SMT with spinal involvement.

| Ref. # | Age/ Sex | Interval between HIV and EBV-SMT (months) | CD4 count (cells/L) | Plasma HIV RNA level (copies/ mL) | Present. Sx | EBV-SMT locations | Spinal level(s) | HAART | Leimyoma or leiomyo-sarcoma | Tx | Outcome / Follow-up time (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 9/M | 108 | 0 | NA | Progress. BLL weakness, sensory loss at T4 | Dura of the spinal cord | C7 and T3–4 | NA | Leiomyoma | SR | NA |

| 2 | 35/M | 24 | 20 | 86,220 | Abdom. pain, LUL pain | Dura of brain and spinal cord, liver | T2, L3 | AZT, 3TC, DRV, RTV | Leiomyoma | Partial SR | Stable (41) |

| 3 | 37/M | NA | NA | NA | Back pain, BLL weakness | Dura of the spinal cord and paraspinal muscles | T6 | NA | NA | SR | Stable (4) |

| 4 | 35/M | NA | 16 | NA | RUL weakness | Dura of the spinal cord | C6 | NA | LMS | SR | Death from disease (1) |

| 5 | 35/F | 96 | NA | NA | BLL weakness, BLL sensory loss | Dura of the spinal cord | T3–4 | NA | LMS | SR, RT | NA |

| 6 | 43/F | 24 | 26 | NA | Back pain | Dura of brain and spinal cord | T3–6 | d4T, 3TC, NVP | LMS | SR, RT | Death of disease (4) |

| 34/F | 1 | 160 | NA | Back pain, BLL weakness | Dura of spinal cord, adrenal gland, abdominal wall | T3–5, T9–11, L1–2 | D4T, 3TC, NVP, EFV | LMS | SR, RT | Stable (24) | |

| 49/F | 12 | 26 | 79,350 | BUL weakness, BLL weakness, Sensory loss below T4 | Dura of brain and spinal cord, vocal cord, orbit, adrenal glands | Cl-6, T2 | d4T, 3TC, NVP | LMS | SR, RT | Stable (10) | |

| 31/F | 3 | 3 | NA | Sensory loss at left T10, spastic paresis | Dura of brain and spinal cord | T7–8, T10–12, L4 | NA | LMS | SR, RT | Stable (5) | |

| 7 | 26/M | NA | NA | NA | Headache and neck pain | Dura of brain and spinal cord | C2–3 | NA | Leiomyoma | SR | NA |

| 8 | 38/M | 114 | NA | NA | NA | Spinal cord, gallbladder, lung, liver | NA | NA | LMS | NA | Death of disease (9) |

LMS = leiomyosarcoma; NA = Not available; SR = surgical resection; RT = radiotherapy; AZT = zidovudine; ddl = didanosine; d4T = stavudine; 3TC = lamivudine; NVP = nevirapine; EFV = efavirenz; SQV = sawunavir; IDV = indinavir; NFV = nelfinavir; RTV = ritonavir; LPV = lopinavir; DRV = darunavir; Sx = symptoms; BLL = bilateral lower limb; BUL = bilateral upper limb; RUL = right upper limb; LUL = left upper limb.

Baseline HIV-disease status was available for 6 patients. Of these, the mean CD4 count was 50, significantly higher than that observed in our patient’s CD4 count of 2. Only two patients reported plasma HIV levels with an average viral load of 82,875 copies/mL. Although all patients had confirmed HIV infections, only four cases included HAART regimens in their reports.

Tumors affected all spinal levels, with cervical spine involvement in four cases, thoracic involvement in eight cases, and lumbar lesions in three cases. In the majority of patients (91%), disease was multifocal, however an isolated lesion was reported in one case. The primary pathology of eight patients was listed as leiomyosarcoma, while three were labeled as leiomyomas. All patients underwent surgical resection of their tumors, and five of the 11 (45%) received adjuvant radiotherapy [6,13–19].

Follow-up data was available for 8 of the 11 patients. Among this group, survival varied greatly, extending between 1 and 41 months. Five patients remained stable throughout a mean follow-up of 17 months. In the remaining three, one patient developed cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis and died four months after diagnosis [18], one developed fatal Staphylococcus aureus septicemia four weeks after surgery [16], and one was assumed to have died from an undiagnosed opportunistic infection as was reported to occur due to “death of disease” [6].

3.1. Differential diagnosis

The current differential diagnosis for a spindle cell neoplasm in an HIV-positive patient includes Kaposi sarcoma (KS), mycobacterial spindle cell pseudotumor (MSCP), and schwannoma [8]. KS can be separated from EBV-associated SMTs histologically, as it is CD31 and CD34 positive, but does not express desmin or smooth muscle-specific antigens (SMA) [1,8]. KS cells also react to the antibody directed against the Kaposi sarcoma human virus, human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8), which is not seen in EBV-associated SMTs [8]. Schwannomas can similarly be distinguished from EBV-associated SMT by histology. The former stain strongly positive for S-100 protein, which shows only minor, focal expression in EBV-associated SMT [6]. In our case, diagnosis also relied upon in situ hybridization, as preoperative radiographic findings were consistent with schwannoma, but in situ hybridization for EBV DNA was positive, consistent with EBV-associated SMT [1]. Lastly, EBV-associated SMTs are distinguished from MSCPs by staining for acid-fast bacilli, which are characteristic of MSCPs, but are absent from the spindle cells of EBV-associated SMTs [1].

Also included in the differential for EBV-associated SMT are gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) and follicular dendritic cell (FDC) sarcomas [1]. Like KS, GIST cells can be differentiated from EBV-associated SMTs by testing positively for CD34. FDC sarcomas have been found to stain positive for CD21, CD23, and CD35. While EBV-associated SMTs also stain positive for CD21, they have been shown to stain negatively for CD23 and CD35 [1].

3.2. Outcome risk factors

Definitive criteria for determining malignancy in smooth muscle tumors arising outside the gynecologic, genitourinary, and gastrointestinal tracts have yet to be established [12]. In one study, retrospective analyses of EBV-associated SMTs occurring at all sites showed that survival was not affected by completeness of resection, number of tumor nodules, tumor size (> or < 5 cm), or sarcoma-like histological features (mitotic rate (≥ 10 mitoses per 10 HPF), cellular polymorphism, or presence of necrosis) [22]. Etiology of immunodeficiency was found to be a more relevant indicator as these patients with HIV had the poorest overall survival, presumably related to higher risk of developing fatal opportunistic infections, compared to post-transplant patients and patients with congenital immunodeficiency syndromes (e.g. leukocyte defect-associated severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)) [22]. Interestingly, the EBV-associated SMTs from HIV patients tended to have higher a mitotic rate (median 5 mitoses/10 HPF) than post-transplant patients (median 1 mitosis/10 HPF; p < 0.001), but mitotic rate alone was not found to be predictive of prognosis in HIV patients. In agreement with the study by Hussein et al. [22], Suankratay and colleagues noted that EBV-associated SMTs with increased mitotic counts (>4 mitoses/10 HPF) in three of nine patients with AIDS did not correlate with more aggressive behavior than those with lower mitotic counts [18]. A literature review by Purgina et al. similarly concluded that mitotic rate does not seem to distinguish cases with malignant outcome [8].

3.3. Treatment/Management

The treatment of EBV-associated SMTs is not well-established, especially in HIV-positive patients, for whom the greatest survival risk is opportunistic infection [22]. Currently, surgical resection and HAART are staples of treatment, while the use of adjuvant radiotherapy or chemotherapy is controversial [8]. Although a few have observed that small increases in CD4 counts were associated with stable tumor sizes [23,24], the main indication for HAART usage is prophylaxis against opportunistic infections, which are the greatest cause of mortality in HIV-positive patients with EBV-associated SMT [1]. Chemotherapy has not been shown to be effective in treating EBV-associated SMTs, and could lead to worse outcomes in the already immunocompromised patients [11,25]. In the case of patients who are too ill to undergo surgery, observation is felt to be the most appropriate management of EBV-associated SMTs [7,23].

4. Conclusion

Although EBV-associated SMTs are rare, the variable aggressiveness of these tumors warrant inclusion into the differential diagnosis of AIDS patients, especially in patients with smooth muscle tumors in uncommon locations like the spine. While treatment guidelines have yet to be established in when tumors involve the spinal column, patients should undergo surgical resection when possible to relieve acute neurologic symptoms and HAART to minimize risk of opportunistic infections. Furthermore, future patients with these rare tumors should be reported with the aim of eventually creating an evidence-based treatment plan for patients.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Dekate J, Chetty R. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated Smooth Muscle Tumor. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med 2016;140(7):718–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Pritzker KP, Huang SN, Marshall KG. Malignant tumours following immunosuppressive therapy. Can. Med. Assoc. J 1970;103(13):1362–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chadwick EG, Connor EJ, Hanson IC, et al. Tumors of smooth-muscle origin in HIV-infected children. JAMA 1990;263(23):3182–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Lee ES, Locker J, Nalesnik M, et al. The association of Epstein-Barr virus with smooth-muscle tumors occurring after organ transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med 1995;332(1):19–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].McClain KL, Leach CT, Jenson HB, et al. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with leiomyosarcomas in young people with AIDS. N. Engl. J. Med 1995;332(1):12–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Deyrup AT, Lee VK, Hill CE, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumors are distinctive mesenchymal tumors reflecting multiple infection events: a clinicopathologic and molecular analysis of 29 tumors from 19 patients. Am. J. Surg. Pathol 2006;30(1):75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jenson HB, Montalvo EA, McClain KL, et al. Characterization of natural Epstein-Barr virus infection and replication in smooth muscle cells from a leiomyosarcoma. J. Med. Virol 1999;57(1):36–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Purgina B, Rao UN, Miettinen M, Pantanowitz L. AIDS-Related EBV-Associated Smooth Muscle Tumors: a Review of 64 Published Cases. Patholog Res. Int 2011;2011:561548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Rougemont AL, Alfieri C, Fabre M, et al. Atypical Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) latent protein expression in EBV-associated smooth muscle tumours occurring in paediatric transplant recipients. Histopathology 2008;53(3):363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Moody CA, Scott RS, Amirghahari N, et al. Modulation of the cell growth regulator mTOR by Epstein-Barr virus-encoded LMP2A. J. Virol 2005;79(9):5499–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ong KW, Teo M, Lee V, et al. Expression of EBV latent antigens, mammalian target of rapamycin, and tumor suppression genes in EBV-positive smooth muscle tumors: clinical and therapeutic implications. Clin. Cancer Res 2009;15(17):5350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Miettinen M Smooth muscle tumors of soft tissue and non-uterine viscera: biology and prognosis. Mod. Pathol 2014;27(Suppl. 1):S17–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Choi S, Levy ML, Krieger MD, McComb JG. Spinal extradural leiomyoma in a pediatric patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: case report. Neurosurgery 1997;40(5):1080–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gallien S, Zuber B, Polivka M, et al. Multifocal Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumor in adults with AIDS: case report and review of the literature. Oncology 2008;74(3–4):167–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lohan R, Bathla G, Gupta S, Hegde AN. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-related smooth muscle tumors of central nervous system – a report of two cases and review of literature. Clin. Imaging 2013;37(3):564–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Morgello S, Kotsianti A, Gumprecht JP, Moore F. Epstein-Barr virus-associated dural leiomyosarcoma in a man infected with human immunodeficiency virus Case report. J. Neurosurg 1997;86(5):883–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Ritter AM, Amaker BH, Graham RS, Broaddus WC, Ward JD. Central nervous system leiomyosarcoma in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome Report of two cases. J. Neurosurg 2000;92(4):688–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Suankratay C, Shuangshoti S, Mutirangura A, et al. Epstein-Barr virus infection-associated smooth-muscle tumors in patients with AIDS. Clin. Infect. Dis 2005;40(10):1521–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Karpinski NC, Yaghmai R, Barba D, Hansen LA. Case of the month: March 1999–A 26 year old HIV positive male with dura based masses. Brain Pathol 1999;9(3):609–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kumar S, Santi M, Vezina G, Rosser T, Chandra RS, Keating R. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumor of the basal ganglia in an HIV+ child: case report and review of the literature. Pediatr. Dev. Pathol 2004;7(2):198–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Boudjemaa S, Boman F, Guigonis V, Boccon-Gibod L. Brain involvement in multicentric Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumours in a child after kidney transplantation. Virchows Arch. 2004;444(4):387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hussein K, Rath B, Ludewig B, Kreipe H, Jonigk D. Clinico-pathological characteristics of different types of immunodeficiency-associated smooth muscle tumours. Eur. J. Cancer 2014;50(14):2417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wong KH, Chan KC, Lee SS, et al. Epstein-Barr virus-associated smooth muscle tumor in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect 2007;40(2):173–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Molle ZL, Bornemann P, Desai N, Clarin E, Anderson V, Rabinowitz SS. Endoscopic features of intestinal smooth muscle tumor in a child with AIDS. Dig. Dis. Sci 1999;44(5):910–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Gupta S, Havens PL, Southern JF, Firat SY, Jogal SS. Epstein-Barr virus-associated intracranial leiomyosarcoma in an HIV-positive adolescent. J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol 2010;32(4):e144–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]