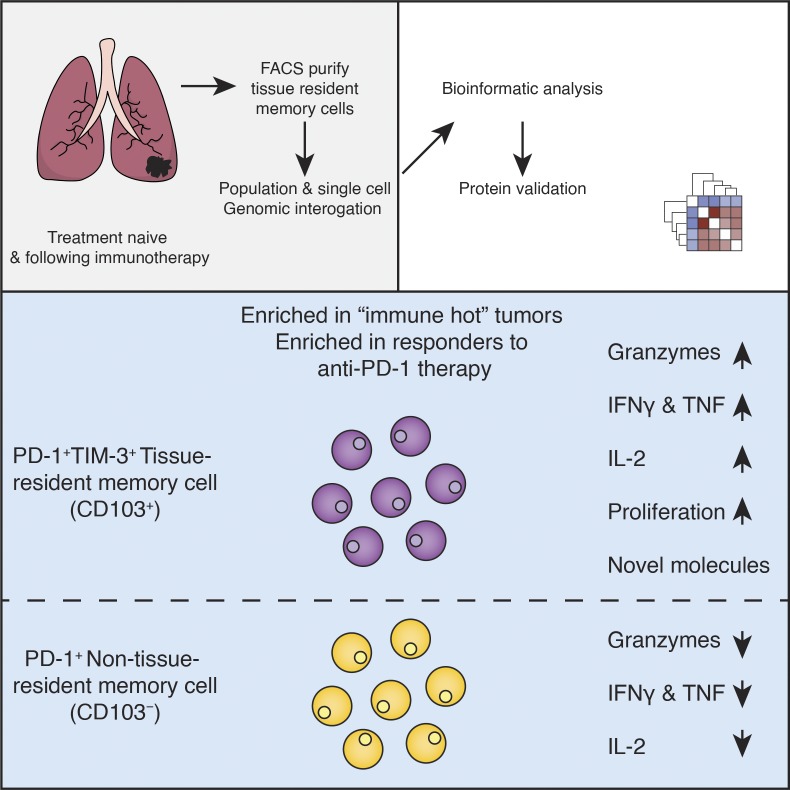

Clarke et al. interrogate human TRM cells from cancer and nonmalignant tissue. These analyses highlight that PD-1 expression in tumor-infiltrating TRM cells was positively correlated with features suggestive of active proliferation and superior functionality rather than dysfunction.

Abstract

High numbers of tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells are associated with better clinical outcomes in cancer patients. However, the molecular characteristics that drive their efficient immune response to tumors are poorly understood. Here, single-cell and bulk transcriptomic analysis of TRM and non-TRM cells present in tumor and normal lung tissue from patients with lung cancer revealed that PD-1–expressing TRM cells in tumors were clonally expanded and enriched for transcripts linked to cell proliferation and cytotoxicity when compared with PD-1–expressing non-TRM cells. This feature was more prominent in the TRM cell subset coexpressing PD-1 and TIM-3, and it was validated by functional assays ex vivo and also reflected in their chromatin accessibility profile. This PD-1+TIM-3+ TRM cell subset was enriched in responders to PD-1 inhibitors and in tumors with a greater magnitude of CTL responses. These data highlight that not all CTLs expressing PD-1 are dysfunctional; on the contrary, TRM cells with PD-1 expression were enriched for features suggestive of superior functionality.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

In lung cancer and many other solid tumors, patient survival is positively correlated with an effective adaptive antitumor immune response (Galon et al., 2006). This response is mediated primarily by CD8+ CTLs. Because CTLs in tumors are chronically activated, they can become “exhausted,” a hyporesponsive state that, in the setting of infection, prevents inflammatory damage to healthy tissue (Wherry, 2011). Exhaustion involves up-regulation of surface molecules such as PD-1 and TIM-3, alongside a gradual diminution of functional and proliferative potential (Pardoll, 2012). Anti-PD-1 therapies have revolutionized cancer treatment by inducing durable responses in some patients (Robert et al., 2015). Given the association of PD-1 with exhaustion and the description of CTLs expressing PD-1 in human cancers, exhausted CTLs are generally assumed to be the cells reactivated by anti-PD-1 therapy, though definitive evidence for this is lacking in humans (Simon and Labarriere, 2017).

Though anti-PD-1 therapies can eradicate tumors in some patients, they also lead to serious “off-target” immune-mediated adverse reactions (June et al., 2017), calling for research to identify features unique to tumor-reactive CTLs. One subset of CTLs that may harbor such distinctive properties are tissue-resident memory T (TRM) cells which mediate the response to antitumor vaccines (Nizard et al., 2017) and facilitate rejection of tumors in animal models (Malik et al., 2017). TRM cell responses have also recently been shown by our group (Ganesan et al., 2017) and others (Djenidi et al., 2015) to be associated with better survival in patients with solid tumors. The molecular features of TRM cell responses have been characterized in infection models and involve rapid clonal expansion and up-regulation of molecules aiding recruitment and activation of additional immune cells alongside the conventional effector functions of CTLs (Schenkel and Masopust, 2014). To date, the properties of TRM cells found in the background lung, compared with those in the tumor, are not fully elucidated. Furthermore, the properties of these cell subsets in the context of immunotherapy are still poorly understood. To address this question, we compared the transcriptome of TRM and non-TRM CTLs present in tumor and normal lung tissue samples from treatment-naive patients with lung cancer. Furthermore, we investigated the same tissue-resident populations in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) and during immunotherapy regimens.

Results

TRM cells in human lungs are transcriptionally distinct from previously characterized TRM cells

We analyzed the transcriptome of CTLs isolated from lung tumor and adjacent uninvolved lung tissue samples obtained from patients (n = 30) with treatment-naive lung cancer (Table S1) sorted according to CD103 expression to separate TRM cells from non-TRM cells, as previously described (Ganesan et al., 2017). Lung CD103+ and CD103− CTLs clustered separately and showed differential expression of nearly 700 transcripts, including several previously linked to TRM cell phenotypes; we validated CD49A and KLRG1 at the protein level, as described previously (Fig. 1 A; Fig. S1, A–C; and Table S2; Hombrink et al., 2016; Ganesan et al., 2017). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) showed that the pattern of expression of these transcripts correlated with a murine core tissue-residency signature in CTLs isolated from both lung and tumor samples (Fig. S2 D and Table S3; Milner et al., 2017). Together, these data confirm that CD103+ CTLs in human lungs and tumors are highly enriched for TRM cells; for simplicity, hereafter, we refer to CD103+ CTLs as TRM cells and CD103− CTLs as non-TRM cells.

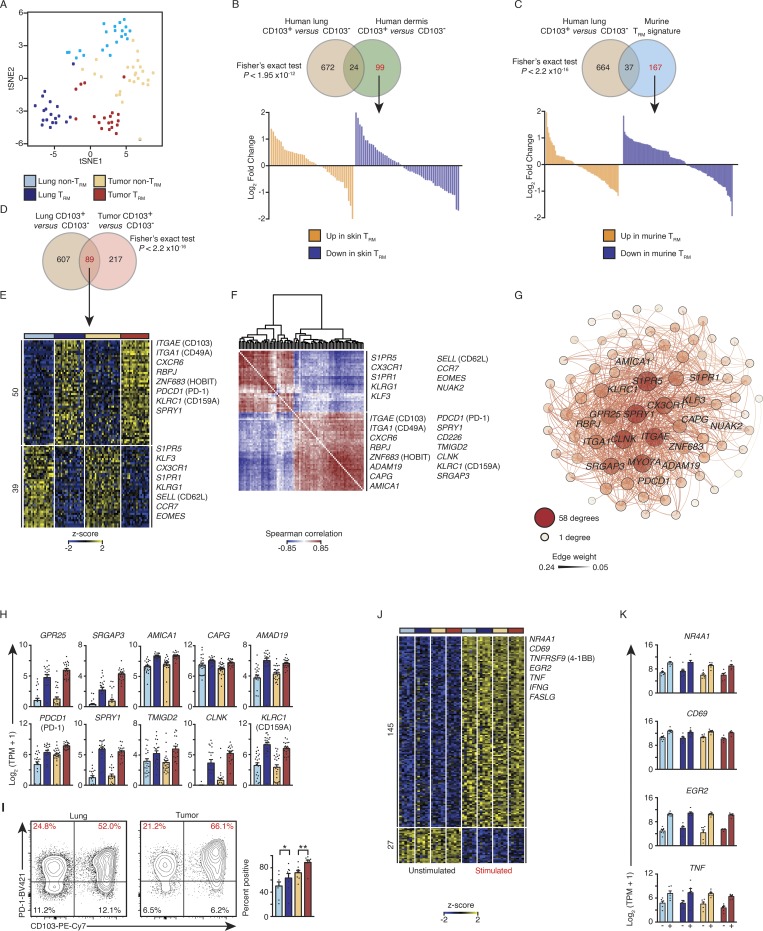

Figure 1.

PD-1 expression is a feature of lung and tumor TRM cells. (A) tSNE plot of tumor and lung CTL transcriptomes segregated by CD103 expression (lung non-TRM = 21, lung TRM = 20, tumor non-TRM = 25, and tumor TRM = 19). (B and C) Top: Venn diagrams showing overlap of transcripts differentially expressed in lung TRM versus other previously characterized TRM cells. Bottom: Waterfall plots represent the DESeq2 normalized fold change from the human lung comparison of genes not significantly (change twofold or less, with an adjusted P value of >0.05) differentially expressed between lung TRM (CD103+) and non-TRM (CD103−) CTLs (marked in red font in the Venn diagram). (D and E) Venn diagram (D) and heat map (E) of RNA-seq analysis of 89 common transcripts (one per row) expressed differentially by lung TRM versus lung non-TRM and tumor TRM versus tumor non-TRM (pairwise comparison; change in expression of twofold with an adjusted P value of ≤0.05 [DESeq2 analysis; Benjamini–Hochberg test]), presented as row-wise z-scores of TPM counts; each column represents an individual sample; known TRM or non-TRM transcripts are indicated. The color scheme and number of samples are identical to A. (F) Spearman coexpression analysis of the 89 differentially expressed genes as in D and E; values are clustered with complete linkage. (G) WGCNA visualized in Gephi, the nodes are colored and sized according to the number of edges (connections), and the edge thickness is proportional to the edge weight (strength of the correlation). (H) Expression values according to RNA-seq data of the indicated differentially expressed genes shared by lung and tumor TRM cells. Each symbol represents an individual sample, the bar represents the mean (colored as in A), and t-lines represents SEM. (I) Flow cytometry analysis of the expression of PD-1 versus that of CD103 on live and singlet-gated CD14−CD19−CD20−CD56−CD4−CD45+CD3+CD8+ cells obtained from lung cancer CTLs and matched paired lung CTLs. Right: Frequency of cell that express PD-1 in the indicated populations (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; n = 8; Wilcoxon rank-sum test); each symbol represents a sample, bars represent the mean, and t-lines represent SEM, colored as per A. (J) RNA-seq analysis of genes (row) commonly up- or down-regulated in the four cell types following 4 h of ex vivo stimulation; heat map as in E. (K) Bar graphs showing expression of transcripts in the indicated populations (n = 6 for all comparisons; as per J); left bar is ex vivo (−), and right bar is the expression profile following stimulation (+).

We next compared differentially expressed transcripts between lung TRM and non-TRM cells with those reported for other TRM cells. The comparison with gene signatures of human skin TRM cells (Cheuk et al., 2017) and that of murine TRM cells isolated from multiple organs (Milner et al., 2017) revealed limited, yet statistically significant overlap (≤5%; Fig. 1, B and C), which suggested that core tissue-residency features were well preserved. However, those differentially expressed transcripts that were not preserved across organs or species were not significantly enriched (Fig. S1 E). Thus, the transcriptional program, outside of a core tissue-residency program of human lung TRM cells, is distinct from that of human skin TRM cells and murine TRM cells present in several organs. Importantly, many of the features observed in human lung TRM cells have not been previously reported (Table S2; Hombrink et al., 2016).

PD-1 expression is a feature of lung and tumor TRM cells

We next asked if TRM cells in lung tumors share tissue-residency features (Materials and methods) with TRM cells in adjacent normal lung tissue. Nearly one third (89/306) of the TRM properties (i.e., transcripts differentially expressed between CD103+ and CD103− CTLs) in tumors were shared with those of normal lung TRM cells (Fig. 1, D and E; and Table S4). Coexpression analysis (Fig. 1 F) and weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA; Fig. 1 G; Materials and methods) of the 89 “shared tissue residency” transcripts revealed a number of novel genes whose expression was highly correlated with known tissue-residency genes (S1PR1, S1PR5, ITGA1 [CD49A], ZNF693 [HOBIT], and RBPJ; Mackay et al., 2013, 2016; Hombrink et al., 2016), suggesting that their products may also play important roles in the development, trafficking, or function of TRM cells (Fig. 1, D–G; and Table S4). Notable examples encoding products likely to be involved in TRM cell functionality, migration, or retention include GPR25 (Kim et al., 2013), SRGAP3 (Bacon et al., 2013), AMICA1 (Witherden et al., 2010), CAPG (Parikh et al., 2003), ADAM19 (Huang et al., 2005), and NUAK2 (Namiki et al., 2011; Fig. 1, F and G; and Fig. 1 H, upper panel).

Another important shared tissue-residency transcript was PDCD1, encoding PD-1 (Fig. 1 H, lower panel). We confirmed at the protein level that PD-1 is expressed at higher levels in both tumor and lung TRM cells compared with non-TRM cells (Fig. 1 I). Although PD-1 expression is considered typical of exhausted T cells, as well as activated cells (Pardoll, 2012), recent reports have suggested that high PD-1 expression is a tissue-residency feature of murine brain TRM cells independent of antigen stimulation (Prasad et al., 2017; Shwetank et al., 2017) and of murine TRM cells from multiple organ systems (Milner et al., 2017). In support of the conclusion that high expression of PD-1 reflects tissue residency rather than exhaustion, we found that when TRM and non-TRM cells isolated from both lung and tumor tissue were stimulated ex vivo (Materials and methods), they showed robust up-regulation of TCR-activation–induced genes (NR4A1, CD69, TNFRSF9 [4-1BB], and EGR2) and cytokines (TNF and IFNG; Fig. 1, J and K; and Tables S1 and S5). In addition to PDCD1, shared tissue-residency transcripts included several genes (SPRY1 [Collins et al., 2012], TMIGD2 [Janakiram et al., 2015], CLNK [Utting et al., 2004], and KLRC1 [Rapaport et al., 2015]) that encode products reported to play a regulatory role in other immune cell types (Fig. 1 H, lower panel). We speculate that the expression of these inhibitory molecules may restrain the functional activity of tumor TRM cells and may represent targets for future immunotherapies. Overall, our transcriptomic analysis of TRM cells has identified molecules that are potentially important for the function of TRM cells and thus serves as an important resource for investigating the biology of human TRM cells.

Tumor TRM cells display greater clonal expansion

To identify features unique to tumor TRM cells, we compared the transcriptome of TRM cells and non-TRM cells from both normal lung and tumors and detected 92 differentially expressed transcripts (Fig. 2 A and Table S4) specifically in this subset, hence termed “tumor TRM-enriched transcripts.” Reactome pathway analysis of these tumor TRM-enriched transcripts showed significant enrichment for transcripts encoding components of the canonical cell cycle, mitosis, and DNA replication machinery (Fig. 2 B and Table S4). The tumor TRM cell subset thus appears to be highly enriched for proliferating CTLs, presumably responding to tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), despite PD-1 expression. Unique molecular identifier (UMI)–based TCR sequencing assays (Materials and methods) revealed that TRM cells in tumors expressed a significantly more restricted TCR repertoire than non-TRM cells in tumors, as shown by significantly lower Shannon–Wiener and inverse Simpson diversity indices (Fig. 2 C and Table S6). Furthermore, the tumor TRM population contained a higher mean percentage of expanded clonotypes (73% versus 52%, in tumor TRM versus non-TRM populations; Fig. 2 D). The most expanded clonotype in each patient comprised, on average, 19% of all TRM cells with sequenced TCRs (three examples; Fig. 2 D, right, and Table S6), suggesting marked expansion of a single TAA-specific T cell clone in the tumor TRM population, in keeping with recent publications (Guo et al., 2018; Savas et al., 2018).

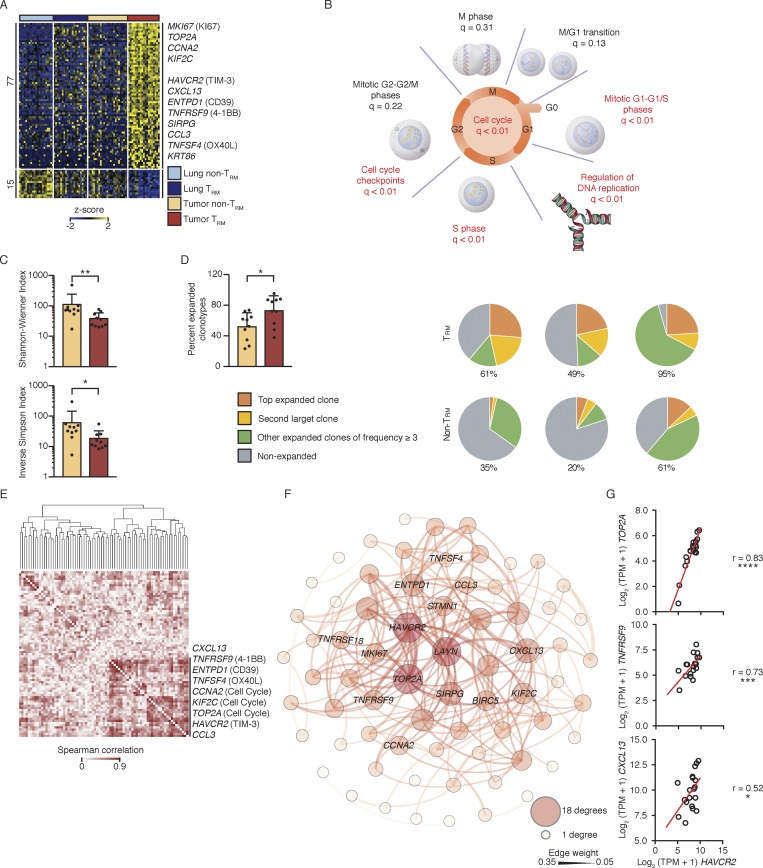

Figure 2.

Tumor TRM cells were clonally expanded. (A) RNA-seq analysis of transcripts (one per row) differentially expressed by tumor TRM relative to lung TRM, lung non-TRM, and tumor non-TRM (pairwise comparison; change in expression of twofold with an adjusted P value of ≤0.05 [DESeq2 analysis; Benjamini–Hochberg test]), presented as row-wise z-scores of TPM counts; each column represents an individual sample (lung non-TRM = 21, lung TRM = 20, tumor non-TRM = 25, and tumor TRM = 19). (B) Summary of overrepresentation analysis (using Reactome) of genes involved in the cell cycle that are differentially expressed by lung tumor TRM cells relative to the other lung CTLs; q values represent FDR. (C) Shannon–Wiener diversity and inverse Simpson indices obtained using V(D)J tools following TCR-seq analysis of β chains in tumor TRM and tumor non-TRM populations. Bars represent the mean, t-lines represent SEM, and symbols represent individual data points (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; n = 10 patients; Wilcoxon rank-sum test). (D) Left: Bar graphs show the percentage of total TCRβ chains that were expanded (≥3 clonotypes). Bars represent the mean, t-lines represent SEM, and dots represent individual data points (*, P ≤ 0.05; n = 10 patients). Right: Pie charts show the distribution of TCRβ clonotypes based on clonal frequency. (E) Spearman coexpression analysis of the 77 genes up-regulated (A) in tumor TRM cells; values are clustered with complete linkage. (F) WGCNA visualized in Gephi; the nodes are colored and sized according to the number of edges (connections), and the edge thickness is proportional to the edge weight (strength of correlation). (G) Correlation of the expression of HAVCR2 (TIM-3) transcripts and the indicated transcripts in the tumor TRM population; r indicates Spearman correlation value (*, P ≤ 0.05; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001; n = 19 patients).

Tumor TRM-enriched transcripts that were highly correlated with cell cycle genes may encode products with important functions, as they are likely to reflect the molecular features of TRM cells that are actively expanding in response to TAA (Table S4). HAVCR2, encoding the coinhibitory checkpoint molecule TIM-3, was most correlated and connected with cell cycle genes (Fig. 2, E–G). Thus, TIM-3 expression may be a feature of lung tumor TRM cells that is not linked to exhaustion but rather reflects a state of functionality, as the other transcripts that correlated with expression of TIM-3 and cell cycle genes encode molecules that likely confer additional functionality, such as CD39 (encoded by ENTPD1; Pallett et al., 2017), CXCL13 (Bindea et al., 2013), CCL3 (Castellino et al., 2006), TNFSF4 (OX-40 ligand; Croft et al., 2009), and a marker of antigen-specific engagement (4-1BB; Bacher et al., 2016; Fig. 2, E–G). Robust expression of this set of molecules was not observed in either human lung TRM cells or in the mouse TRM signatures (Hombrink et al., 2016; Mackay et al., 2016; Milner et al., 2017), indicating that the human tumor TRM population contains novel cell subsets.

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals previously uncharacterized TRM subsets

To determine whether tumor TRM-enriched transcripts are expressed in all or only a subset of the tumor TRM populations, we performed single-cell RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) assays in CD103+ and CD103− CTLs isolated from tumor and matched adjacent normal lung tissue from an additional 12 patients with early-stage lung cancer (Table S1). Analysis of the ∼12,000 single-cell transcriptomes revealed five clusters (Materials and methods) of TRM cells and four clusters of non-TRM cells with varying frequency per donor, highlighting the importance of studying multiple patient samples (Fig. 3, A and B; and Fig. S2, A–C). Among the five TRM clusters, clusters 1–3 (light purple, purple, and blue, respectively) contained a greater proportion of the tumor TRM population, while clusters 4 and 5 (green and red) contained more lung TRM cells (Fig. 3 C). Most strikingly, clusters 1–3 contained very few lung TRM cells (Fig. 3 C). We infer that the tumor TRM-enriched transcripts detected in our analysis of bulk populations (Fig. 2 A) were likely to be contributed by cells in these subsets.

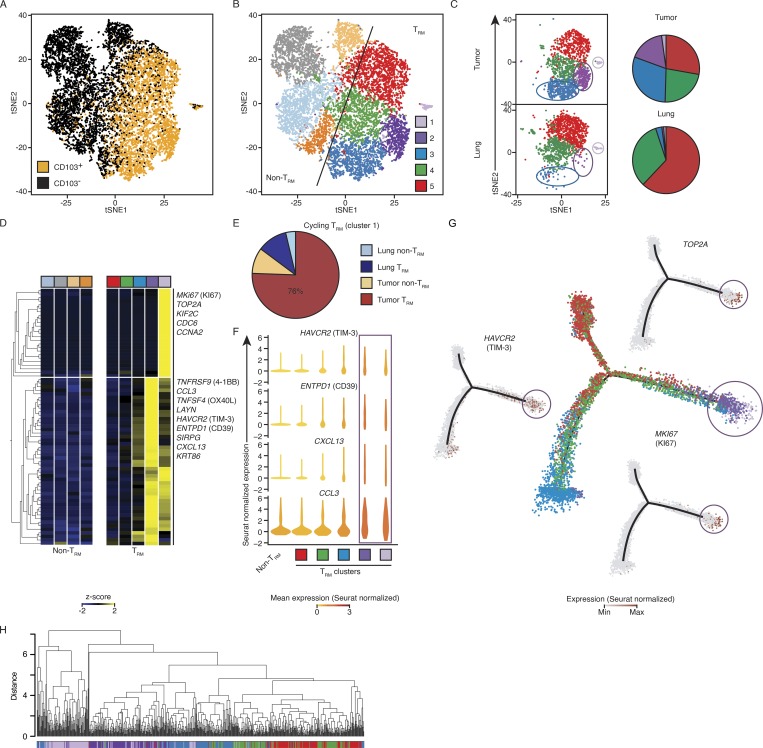

Figure 3.

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis reveals previously uncharacterized TRM subsets. (A) tSNE visualization of ∼12,000 live and singlet-gated CD14−CD19−CD20−CD4−CD56−CD45+CD3+CD8+ single-cell transcriptomes obtained from 12 tumors and 6 matched normal lung samples. Each symbol represents a cell; color indicates protein expression of CD103 detected by flow cytometry. (B) Seurat clustering of cells in A, identifying nine clusters. (C) Cells from tumor and lung were randomly down-sampled to equivalent numbers of cells. Left: Distribution of TRM-enriched clusters in tumor and lung. Right: Pie chart representing the relative proportions of cells in each TRM cluster. (D) Expression of transcripts previously identified as up-regulated in the bulk tumor TRM population (Fig. 2 A) by each cluster; each column represents the average expression in a particular cluster. (E) Breakdown of cell type and tissue localization of cells defined as being in cluster 1 (shown in light purple in B and D). (F) Violin plots of expression of example tumor TRM genes in each TRM-enriched cluster (square below indicates the cluster type) and non-TRM cells; shape represents the distribution of expression among cells and color represents the Seurat-normalized average expression counts. (G) Cell-state hierarchy maps generated by Monocle2 bioinformatic modeling of the TRM clusters. In the center plot, each dot represents a cell colored according to Seurat-assigned cluster. Surrounding panels show relative Seurat-normalized expression of the indicated genes. (H) Cluster analysis of the location in PCA space for cells. Each cluster was randomly down sampled to the equivalent size of the smallest cluster (n = 135 cells per cluster, 675 total). The correlation method was Spearman, and the dataset was clustered with average linkage.

In agreement with that conclusion, cells in cluster 1 (light purple) expressed high levels of the 25 cell cycle–related tumor TRM-enriched transcripts (Fig. 3 D; Macosko et al., 2015), indicating that the enrichment of cell cycle transcripts in the bulk tumor TRM population was contributed by this relatively small subset. Because these cells are actively proliferating, they likely represent TAA-specific cells. The majority of cells in this cycling cluster were from the tumor TRM population (Fig. 3 E). These cells, as well as those in the larger cluster 2 (purple), were highly enriched for other prominent tumor TRM-enriched transcripts like HAVCR2 (TIM-3), including those encoding products that could confer additional functionality, such as CD39 (Ganesan et al., 2017), CXCL13 (Bindea et al., 2013), and CCL3 (Castellino et al., 2006; Fig. 3 F), consistent with recent reports (Guo et al., 2018; Savas et al., 2018), but with a noteworthy caveat that transcript expression does not necessarily reflect functionality. This shared expression pattern suggests that the cycling cluster (cluster 1, light purple) may represent cells in cluster 2 that are entering the cell cycle. Confirming this idea, cell-state hierarchy maps of all TRM cells, constructed using Monocle2 (Trapnell et al., 2014; Materials and methods), revealed that cells in cluster 2 were most similar to the cycling TRM cells (cluster 1, Fig. 3 G). Additionally, when we performed hierarchical clustering (Materials and methods) of these cells, we noted that the proliferating cluster 1 clustered more with cells assigned to cluster 2, than the other TRM clusters (Fig. 3 H). This finding was corroborated when we calculated the average distance in principal component (PC) space (Materials and methods) between each cell in cluster 1 to the other TRM clusters (Fig. S2 D).

T cells expressing TCF7, encoding the transcription factor TCF-1, are linked to “stemness” and have been shown to sustain T cell expansion and responses following anti-PD-1 therapy during chronic infections and in tumor models in mice (Im et al., 2016; Utzschneider et al., 2016). Applying unbiased differential expression analysis (Model-based Analysis of Single-cell Transcriptomics; MAST), we found that among the tumor-infiltrating CTLs TCF7 expression was enriched in the CCR7 (CD197)- and SELL (CD62L)-expressing non-TRM subset, likely to reflect central memory cells (Figs. 3 B and S2 E; light orange), with no significant enrichment observed in any of the TRM clusters (1 and 2) linked to cell proliferation (Fig. S2 E and Table S7) compared with other TRM clusters. This finding is consistent with recent reports which showed that in mouse tumor models Tcf7+ tumor-infiltrating T cells were enriched for central memory, but not TRM, cell features (Siddiqui et al., 2019), and in patients with melanoma, TCF7+ tumor-infiltrating T cells were mainly bystander cytotoxic T cells, whereas tumor-reactive cells were TCF7low/negative (Li et al., 2019). Overall, our single-cell transcriptome uncovered additional phenotypically distinct subsets of lung and tumor TRM cells that have not previously been described and are likely to play an important role in antitumor immune responses.

TIM-3+IL7R− TRM cell subset was enriched for transcripts linked to cytotoxicity

To dissect the molecular properties unique to tumor-infiltrating TRM cells in each of the four larger TRM clusters (clusters 2–5), we performed multiple pairwise single-cell differential gene expression analyses (Materials and methods). Over 250 differentially expressed genes showed higher expression in any one of the four clusters (Fig. 4 A and Table S7), indicating that cells in different clusters had divergent gene expression programs. For example, cells in cluster 3 were highly enriched for transcripts encoding heat shock proteins (e.g., HSPA1A, HSPA1B, and HSP90AA1), whereas cells in cluster 5, comprising TRM cells from both normal lung and tumor tissue, expressed high levels of IL7R, which encodes the IL-7 receptor, a marker of memory precursor cells (Patil et al., 2018), and transcripts such as GPR183 (Emgård et al., 2018), MYADM (Aranda et al., 2011), VIM (Nieminen et al., 2006), and ANKRD28 (Tachibana et al., 2009), which encode proteins involved in cell migration and tissue homing (Fig. 4, A and B).

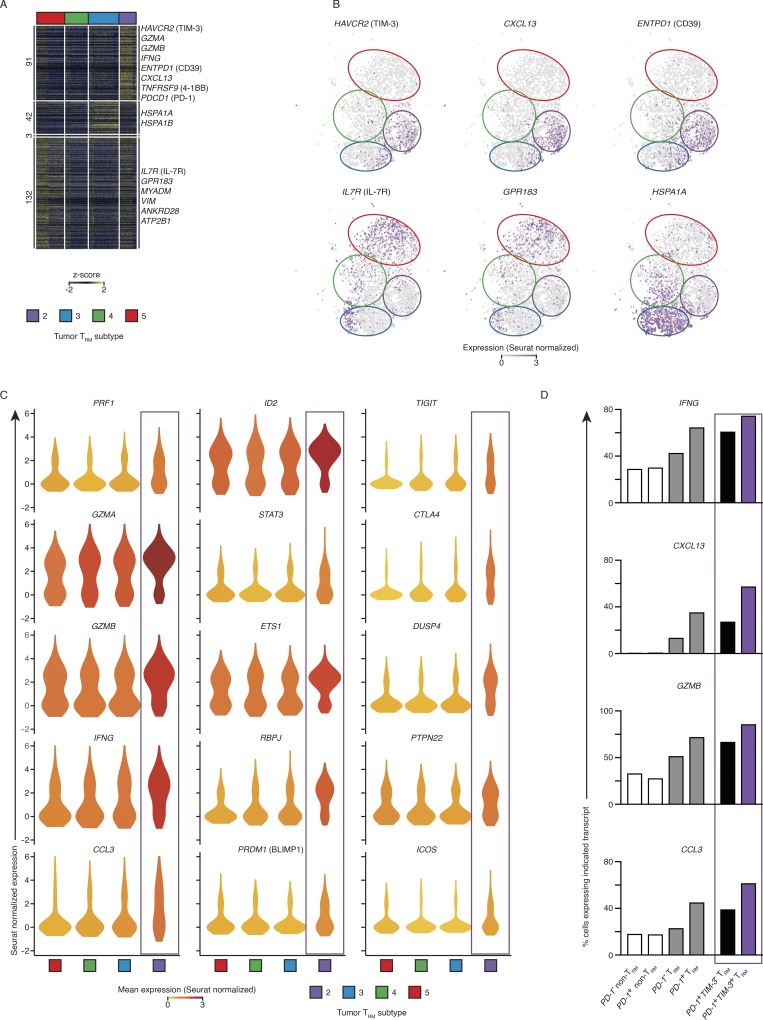

Figure 4.

The TIM-3+IL7R− TRM subset was enriched for transcripts linked to cytotoxicity. (A) Single-cell RNA-seq analysis of transcripts (one per row) uniquely differentially expressed by each tumor TRM subset in pairwise analysis compared with other clusters (adjusted P value of ≤0.01; MAST analysis), presented as row-wise z-scores of Seurat-normalized count; each column represents an individual cell. Horizontal breaks separate genes enriched in each of the four tumor TRM subsets. (B) Seurat-normalized expression of indicated transcripts identified as differentially enriched in each cluster (as per A), overlaid across the tSNE plot, with expression levels represented by the color scale. (C) Violin plot of expression of functionally important genes identified as significantly enriched in a tumor TRM subset; shape represents the distribution of expression among cells and color represents the Seurat-normalized average expression (cluster identification as per A). (D) Percentage of cells expressing the indicated transcripts in each population, where positive expression was defined as >1 Seurat-normalized count; “TRM” corresponds to tumor-infiltrating CTLs isolated from clusters 2, 3, 4, and 5, and “non-TRM” corresponds to to the remaining cells not assigned into the proliferating TRM cluster 1.

Because of their close relationship with cycling TRM cells (Fig. 3, D, G, and H), we focused our analysis on the TRM cells in cluster 2. The 91 transcripts enriched in cluster 2 compared with the other TRM cell clusters (Fig. 4 A) included several that encoded products linked to cytotoxic activity such as PRF1, GZMB, GZMA, and CTSW (Patil et al., 2018), RAB27A (Stinchcombe et al., 2001), ITGAE (Franciszkiewicz et al., 2013), and CRTAM (Patil et al., 2018; Figs. 4 C and S3 A), as well as transcripts encoding effector cytokines and chemokines such as IFN-γ, CCL3, CXCL13, IL-17A, and IL-26. Cluster 2 also expressed high levels of transcripts encoding transcription factors known to promote the survival of memory or effector CTLs (ID2 [Yang et al., 2011], STAT3 [Cui et al., 2011], ZEB2 [Dominguez et al., 2015], and ETS-1 (Muthusamy et al., 1995) or those that are involved in establishing and maintaining tissue residency (RBPJ, a key player in Notch signaling [Hombrink et al., 2016], and BLIMP1 [Mackay et al., 2016], encoded by PRDM1; Figs. 4 A and S3 A). TRM cells in cluster 2 also strongly expressed ENTPD1 (Fig. 4, A and B), which encodes CD39, an ectonucleotidase that cleaves ATP, which may protect this TRM cell subset from ATP-induced cell death in the ATP-rich tumor microenvironment (Pallett et al., 2017) and has recently been shown to be enriched for tumor neoantigen-specific CTLs (Duhen et al., 2018; Simoni et al., 2018). This expression pattern likely confers highly effective and sustained antitumor immune function; in combination with earlier results, we conclude that this TIM-3+IL7R− TRM subset likely represents TAA-specific cells that were enriched for transcripts linked to cytotoxicity.

Intriguingly, TRM cells in cluster 2 (TIM-3+IL7R− subset) expressed the highest levels of PDCD1 transcripts (Fig. 4 A) and were enriched for transcripts encoding other molecules linked to inhibitory functions such as TIM-3, TIGIT (Chan et al., 2014), and CTLA4 (Pardoll, 2012), and inhibitors of TCR-induced signaling and activation, like CBLB, SLAP, DUSP4, PTPN22, and NR3C1 (glucocorticoid receptor; Fig. 4, A–C; and Fig. S3 A; Huang et al., 2012; Xiao et al., 2015; Engler et al., 2017). Nonetheless, these TRM cells expressed high transcript levels for cytotoxicity molecules (perforin, granzyme A, and granzyme B) and several costimulatory molecules such as 4-1BB, ICOS, and GITR (TNFRSF18; Figs. 4 C and S3 A; Pardoll, 2012). This coexpression program appeared to be specific to the tumor TRM compartment, given it was also reflected in a SAVER (single-cell analysis via expression recovery)-imputed (Huang et al., 2018) coexpression profile being identified specifically in the TRM subsets, but not the non-TRM subsets (Fig. S3 B). In addition, direct comparison (Materials and methods) of the transcriptome of all PDCD1-expressing TRM cells versus the non-TRM cells present in tumors confirmed that PDCD1+ TRM cells displayed significantly higher expression of transcripts linked to effector function (IFNG, CXCL13, GZMB, and CCL3) when compared with PDCD1+ non-TRM cells and CTLs not expressing PDCD1 (Fig. 4 D and Table S7). More specifically PDCD1+ TRM cells that also coexpressed TIM-3 (cells in cluster 2) showed the highest expression levels of effector molecules compared with other subsets (Fig. 4 D). Overall, these findings agree with the bulk RNA-seq analysis, indicating that in TRM cells, expression of particular inhibitory molecules, such as PD-1 and TIM-3, does not reflect exhaustion.

PD-1– and TIM-3–expressing tumor-infiltrating TRM cells are not exhausted

To further address whether PDCD1-expressing TRM cells in cluster 2 (TIM-3+IL7R− TRM cells) were exhausted or functionally active, we performed single-cell RNA-seq in tumor-infiltrating TRM and non-TRM cells using the more sensitive Smart-seq2 assay (Table S1). This also enabled paired transcriptomic and TCR clonotype analysis (Picelli et al., 2014; Patil et al., 2018). We reconstructed the TCRβ chains (Materials and methods) in 80.5% of single cells, the TCRα chain in 76.6% of cells, and both chains in 66.6% of cells (Table S8). As expected, clonally expanded tumor-infiltrating TRM cells, which are likely to be reactive to TAA, were significantly enriched for genes specific to TIM-3+IL7R− TRM cells (Fig. 5 A and Table S7). Among tumor-infiltrating CTLs, a greater proportion of TIM-3–expressing (Materials and methods) TRM cells were clonally expanded compared with other TRM and non-TRM cells (Fig. 5 B). Furthermore, TIM-3–expressing TRM cells were significantly enriched for key effector cytokines and cytotoxicity transcripts (Table S9), despite expressing significantly higher levels of PDCD1 (Fig. 5 C).

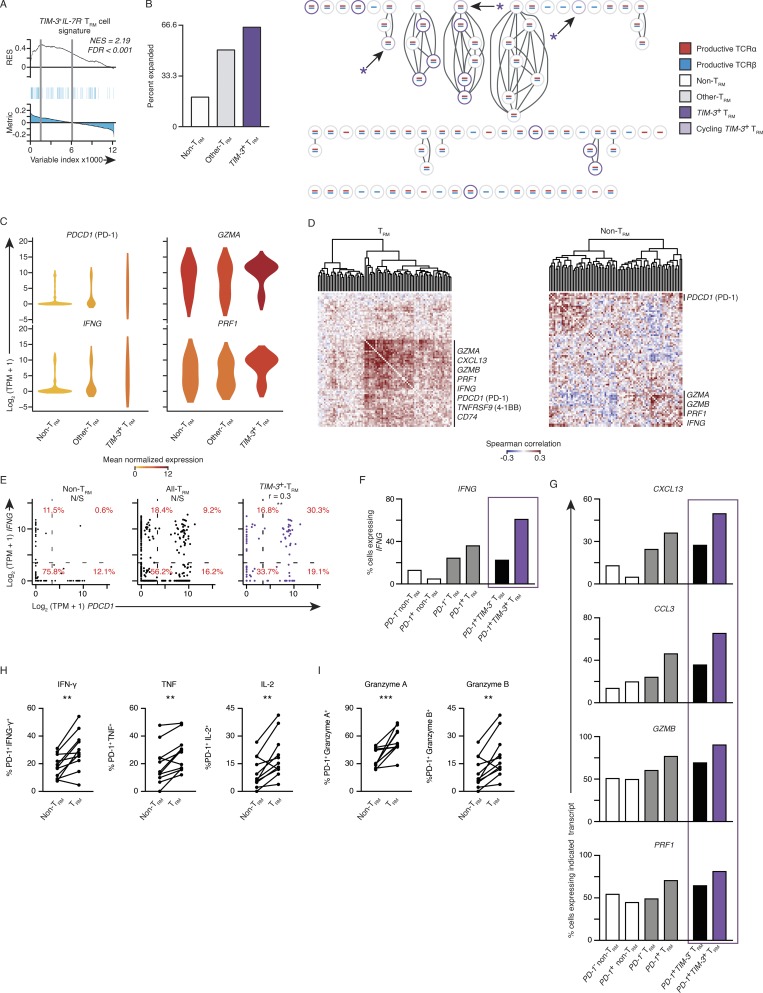

Figure 5.

PD-1– and TIM-3–expressing tumor-infiltrating TRM cells are not exhausted. (A) GSEA of the TIM-3+IL7R− TRM subset signature in the transcriptome of clonally expanded tumor TRM versus that of nonexpanded TRM cells. Top: Running enrichment score (RES) for the gene set, from most enriched at the left to most underrepresented at the right. Middle: Positions of gene set members (blue vertical lines) in the ranked list of genes. Bottom: Value of the ranking metric. Values above the plot represent the normalized enrichment score (NES) and FDR-corrected significance. (B) Left: Percentage of cells that were clonally expanded in TIM-3+ (HAVCR2 ≥10 TPM counts) TRM cells, remaining TRM cells, and non-TRM cells; clonal expansion was determined for cells from four and two patients for TRM and non-TRM, respectively. Right: Section of a clonotype network graph of cells from a representative patient. TIM-3+ (HAVCR2 ≥10 TPM counts) TRM cells are marked with a purple circle; cells with >10 TPM counts expression of either MKI67 or TOP2A were considered cycling and denoted with an asterisk. (C) Violin plot of expression of indicated transcripts; shape represents the distribution of expression among cells and color represents average expression, calculated from the TPM counts (color coded as per B). (D) Spearman coexpression analysis of genes whose expression is enriched in the TIM-3+IL7R− TRM cluster (Fig. 4 A) in tumor TRM and non-TRM populations, respectively; matrix is clustered according to complete linkage. (E) Correlation of PDCD1 and IFNG expression in non-TRM cells, all TRM cells, and then in TIM-3+ TRM; each dot represents a cell. Percentages indicate the percentage of cells inside each of the graph sections (r indicates Spearman correlation value; **, P ≤ 0.01; N/S, no significance). (F) Percentage of cells expressing IFNG in each indicated population segregated on PD-1+ (PDCD1 ≥ 10 TPM counts). The final two bars are the TRM population, as segregated by having expression of HAVCR2 (TIM-3) ≥ 10 TPM counts. (G) Percentage of cells expressing the indicated transcript as identified above the plot in each population (as per F). (H) Flow cytometry analysis of the percentage of PD-1+ TRM and PD-1+ non-TRM cells that express effector cytokines (as indicated above the graph) following 4 h of ex vivo stimulation. Gated on live and singlet-gated CD14−CD20−CD4−CD45+CD3+CD8+ cells obtained from lung cancer TILs, discriminated on CD103 expression (**, P ≤ 0.01; n = 11; Wilcoxon rank-sum test); each symbol represents a sample. Surface molecules (e.g., PD-1) were stained before stimulation. (I) Analysis of granzyme A and granzyme B directly ex vivo, gated and analyzed as per H (***, P ≤ 0.001; Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

The higher sensitivity of the SMART-seq2 assay compared with the high-throughput 10X Genomics platform also allowed coexpression analysis due to lower dropout rates (Patil et al., 2018). Coexpression analysis showed that expression of PDCD1 and HAVCR2 (TIM-3) correlated with that of activation markers (TNFRSF9 and CD74), IFNG, and cytotoxicity-related transcripts more strongly in TRM cells than in non-TRM cells (Fig. 5 D). Specifically, IFNG and PDCD1 expression levels were better correlated in TIM-3–expressing TRM cells compared with all TRM cells and non-TRM cells (Fig. 5 D and Table S10), and the proportion of cells strongly coexpressing these transcripts was notably higher (30.3% versus 9.2% versus 0.6%; Fig. 5 E). Furthermore, in concordance with our high-throughput single-cell RNA-seq assays, this higher-resolution analysis verified that IFNG, alongside additional effector molecule–associated transcripts (CXCL13, CCL3, GZMB, and PRF1), were particularly enriched in TIM-3+ TRM cells versus TIM-3– TRM cells and both PDCD1+ and PDCD1− non-TRM cells (Fig. 4 D; and Fig. 5, F and G). Overall, these results strongly support that PD-1– and TIM-3–expressing tumor-infiltrating TRM cells were not exhausted but instead were enriched for transcripts (IFNG, PRF1, and GZMB) encoding for molecules linked to effector functions.

In keeping with our transcriptomic assays, when stimulated ex vivo, the percentage of tumor-infiltrating TRM cells that coexpressed PD-1 (stained before stimulation) and effector cytokines was significantly higher when compared with non-TRM CTLs (Fig. 5 H; gating previously reported; Ganesan et al., 2017). Analysis directly ex vivo demonstrated there was also greater coexpression of the PD-1 and cytotoxic-associated proteins granzyme A and granzyme B in TRM cells, when compared with non-TRM CTLs in the tumor (Fig. 5 I). These data verify that PD-1 expression in the TRM subset of tumor-infiltrating CTLs does not necessarily reflect dysfunctional properties.

Surface TIM-3+IL-7R− status uniquely characterizes a set of tumor TRM cells

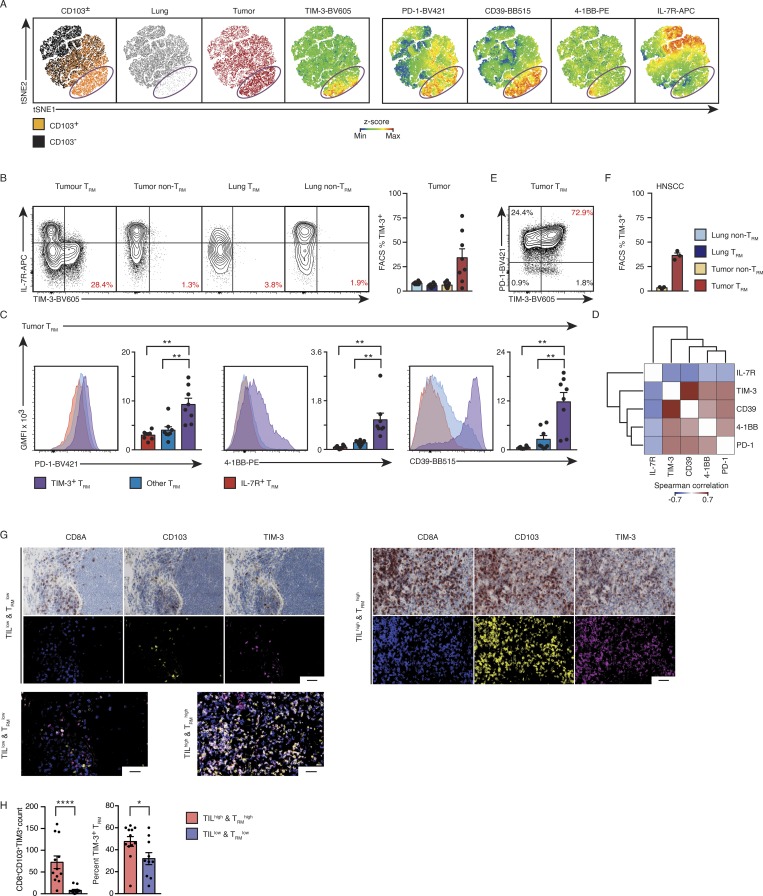

We next evaluated the protein expression of selected molecules to better discern the tumor-infiltrating TRM subsets. Multiparameter protein analysis of CTLs (Materials and methods) present in tumors and adjacent normal lung revealed a subset of TRM (CD103+) cells localized distinctly when the data were visualized in two-dimensional space (Fig. 6 A). This subset consisted of tumor TRM cells only from tumor tissue (purple circle, Fig. 6 A), and uniquely expressed high levels of TIM-3 and lacked IL-7R, indicating that this cluster is the same as the TIM-3–expressing tumor TRM cluster (cluster 2) identified by single-cell RNA analysis (Fig. 6 B). Consistent with the single-cell transcriptome analysis, the TIM-3–expressing TRM cluster was unique to the TRM cells isolated from the tumor and expressed higher levels of CD39, PD-1, and 4-1BB (Fig. 6, A and C). PD-1 and TIM-3 expression levels were also positively correlated with expression of 4-1BB, which is expressed following TCR engagement by antigen (Bacher et al., 2016; Fig. 6, D and E), indicating that these cells are highly enriched for TAA-specific cells. TIM-3–expressing CTLs were also detected among tumor-infiltrating TRM cells isolated from both treatment-naive lung cancer and HNSCC samples (Fig. 6 F), but not among non-TRM cells in these treatment naive tumors or TRM cells in lung. Multicolor immunohistochemistry (IHC) was used to confirm the presence of TIM-3–expressing TRM cells in lung tumor samples, which also showed enrichment of this subset in TILhiTRMhi “immune hot” tumors (Fig. 6, G and H; and Table S11). These findings confirmed, at the protein level, the restriction of the TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM subset to tumors from two cancer types.

Figure 6.

Surface TIM-3+IL-7R− status uniquely characterizes a set of tumor TRM cells. (A) tSNE visualization of flow cytometry data from 3,000 randomly selected live and singlet-gated CD14−CD19−CD20−CD56−CD4−CD45+CD3+CD8+ cells isolated from eight paired tumor and lung samples; each cell is represented by a dot colored as TRM or non-TRM (left), tumor or lung (second and third from left), and according to z-score expression value of the protein indicated above the plot (remaining panels). (B) Left: Contour plots show the expression of TIM-3 versus IL-7R in the cell type and tissue indicated above the plot; percentage of tumor CTLs (gated as above) in the indicated populations that express TIM-3 is shown. Right: Quantification of TIM-3+ in cells isolated from each tissue location; each symbol represents an individual sample. The small line indicates SEM, and bars represent the mean and are colored as indicated (*, P ≤ 0.05; n = 8, 3). (C) Geometric mean fluorescent intensity (GMFI) of CD39, PD-1, and 4-1BB for each lung tumor-TRM subset; bars represent the mean, t-lines represent SEM, and each symbol represents data from individual samples (**, P ≤ 0.01; n = 8; Wilcoxon rank-sum test); representative histograms are shown at left. (D) Coexpression analysis of flow cytometry data (C), as per Spearman correlation. (E) Contour plot highlighting the expression of PD-1 versus TIM-3 in CD14−CD19−CD20−CD56−CD4−CD45+CD3+CD8+CD103+ cells in a representative donor. (F) Analysis of three HNSCC samples, as per B. (G) Left: Representative multiplexed immunohistochemistry of CD8A, CD103, and TIM-3 in tumor specimens from a patient with TILlow/TRMlow tumor status; the representative false color image (middle) and the overlaid image (bottom) are shown. Right: As the left plots for a patient with TILhigh/TRMhigh tumor status (scale bar, 50 µm). (H) Left: Quantification of the number of CD8A+CD103+TIM-3+ cells per region in biopsies defined as having a TILhigh/TRMhigh status versus TILlow/TRMlow status. Right: Percentage of CD8A+CD103+ CTLs expressing TIM-3 in each clinical subtype. Bars represent the mean, t-lines represent SEM, and symbols represent individual data points (*, P ≤ 0.05; ****, P ≤ 0.0001; n = 21; Mann–Whitney U test).

Single-cell transcriptome analysis of CTLs from anti-PD-1 responders

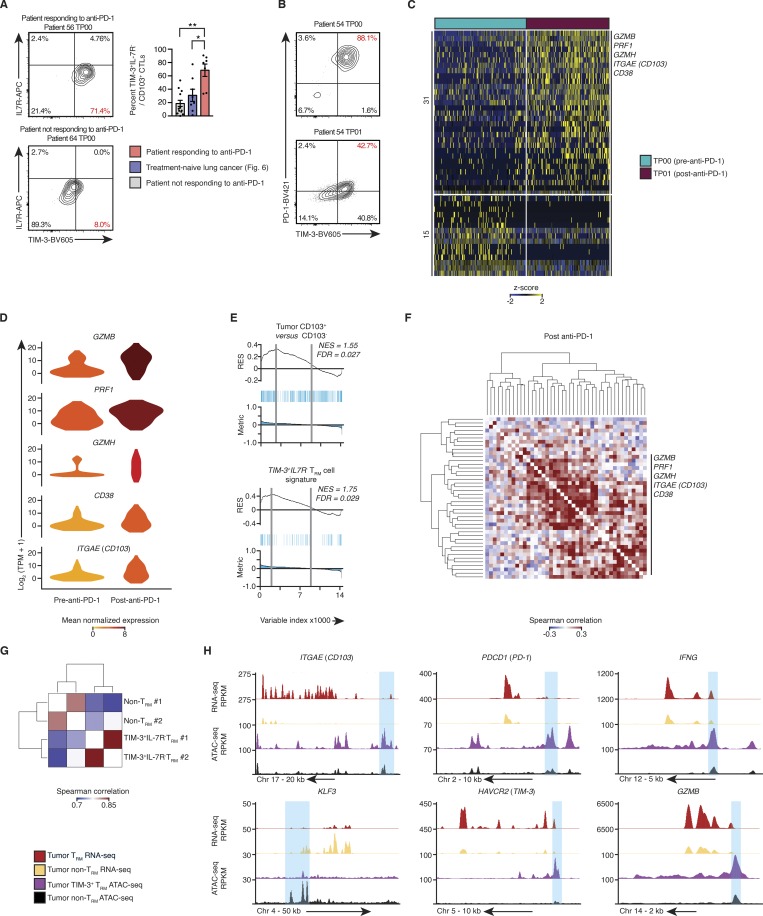

We next analyzed tumor-infiltrating T cells from 19 biopsies (Table S1) with known divergent responses to anti-PD-1 therapy. Flow cytometry analysis of tumor TRM cells isolated from responding patients before, during, and after treatment, showed increased proportion of TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM cells compared with the tumor TRM cells from our cohort of treatment-naive lung cancer patients and those not responding to anti-PD-1 (median, ∼70% versus ∼24% and ∼19%, respectively; Figs. 7 A and S4 A). This population also expressed high levels of PD-1 in samples before anti-PD-1 therapy that decreased after treatment, which is likely reflective of the clinical antibody blocking flow cytometric analysis (Huang et al., 2017; Fig. 7 B). Given this population had high expression of PD-1 (Figs. 6, A–E; and Fig. 7 B), we concluded that these TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM cells are likely to be one of the key immune cell types that respond to anti-PD-1 therapy.

Figure 7.

Single-cell transcriptome analysis of CTLs from anti-PD-1 responders. (A) Left: Contour plots show the expression of TIM-3 and IL-7R in CD14−CD19−CD20−CD4−CD45+CD3+CD8+CD103+ cells isolated from patients receiving anti-PD-1 treatment at the time point (TP) indicated above the plot; number in red indicates the percentage of tumor TRM cells (CD8+CD103+) with TIM-3+IL-7R− surface phenotype. Right: Quantification of the percentage of tumor-infiltrating TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM cells, isolated from the anti-PD-1 responding, nonresponding, and treatment-naive patients. Bars represent the mean, t-lines represents SEM, and symbols represent individual data points (*, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; n = 7, 8, and 12 biopsies for responders, treatment-naive patients, and nonresponders, respectively; Mann–Whitney U test). (B) Contour plots demonstrate the expression of TIM-3 and PD-1 in the TRM cells isolated from preimmunotherapy biopsies (gated as per Fig. 7 A). (C) Single-cell RNA-seq analysis of transcripts (one per row) differentially expressed between CTLs pre– and post–anti-PD-1 (MAST analysis), with an adjusted P value of ≤0.05), presented as row-wise z-scores of TPM counts; each column represents a single cell (n = 127 and 151 cells, respectively). (D) Violin plot of expression of indicated transcripts differentially expressed between tumor-infiltrating CTLs isolated from pre– and post–anti-PD-1 treatment samples (as per C); shape represents the distribution of expression among cells, and color represents average expression, calculated from the TPM counts. (E) GSEA of the bulk tumor CD103+ versus CD103− transcriptional signature (Fig. 2 A) and TIM-3+IL7R− TRM cell signature (Fig. 4 A) in tumor-infiltrating CTLs isolated from pre– and post–anti-PD-1 treatment samples. Top: RES for the gene set, from most enriched at the left to most underrepresented at the right. Middle: Positions of gene set members (blue vertical lines) in the ranked list of genes. Bottom: Value of the ranking metric. Values above the plot represent the NES and FDR-corrected significance. (F) Spearman coexpression analysis of transcripts enriched in tumor-infiltrating CTLs from post–anti-PD-1 treatment samples (C); matrix is clustered according to complete linkage. (G) Correlation analysis of all peaks identified in the OMNI-ATAC-seq libraries, pooled from nine donors across two experiments; cells were sorted on CD14−CD19−CD20−CD4−CD45+CD3+CD8+CD103+TIM-3+IL-7R− and CD14−CD19−CD20−CD4−CD45+CD3+CD8+CD103−. The matrix is clustered according to complete linkage. (H) University of California Santa Cruz genome browser tracks for key TRM-associated gene loci as indicated above the tracks. RNA-seq tracks are merged from all purified bulk RNA-seq data, presented as reads per kilobase million (RPKM; as per Fig. 1 A; tumor non-TRM = 25, tumor TRM = 19; OMNI-ATAC-seq as per Fig. 7 G).

To comprehensively evaluate the molecular features and clonality of the CTLs (Fig. S4, A–C; and Materials and methods) responding to anti-PD-1 therapy, we performed paired single-cell transcriptomic and TCR analysis of CTLs isolated from biopsies both before and after therapy from two donors. This enabled us to maximize the usage of the material in these small, clinically difficult to obtain biopsies. Differential expression analysis of all CD8+ tumor-infiltrating CTLs revealed a significant enrichment of markers linked to cytotoxic function (PRF1, GZMB, and GZMH) and activation (CD38) in posttreatment samples when compared with pretreatment samples (Fig. 7, C and D; and Tables S1 and S12). Notably, we found increased expression of ITGAE, a marker of TRM cells, in CTLs from posttreatment samples (Fig. 7, C and D). GSEA also showed that tumor-infiltrating T cells from posttreatment samples were enriched for TRM features as well as those linked to the TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM subset (Fig. 7 E and Tables S4 and S7). Unbiased coexpression analysis of transcripts from posttreatment CTLs demonstrated that transcripts linked to cytotoxicity (GZMH) and activation (CD38) clustered together with the TRM marker gene (ITGAE; Fig. 7 F and Table S12). Furthermore, we found several expanded TCR clones that were present before and after therapy (Fig. S4, D and E), which indicated that TIM-3–expressing TRM cells (> 87% of the TRM cells in pretreatment samples) with these clonotypes persisted in vivo for several weeks during treatment and largely maintained TIM-3 expression in posttreatment samples (>79% of the TRM cells; Fig. S4 C). By restricting our analysis to these expanded clones, we found that the expression of GZMB, PRF1, GZMH, and CD38 (Fig. S4 F) was increased in CTLs from posttreatment samples, which suggested that tumor-infiltrating CTLs with the same specificity displayed enhanced cytotoxic properties following anti-PD-1 treatment and that TRM cells likely contributed to this feature.

To provide a further line of evidence for the functional potential of TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM cells and further characterize their epigenetic profile, we performed an assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing (OMNI-ATAC-seq; Corces et al., 2017) on purified populations of tumor-infiltrating TIM3+IL7R− TRM and non-TRM subsets pooled from lung cancer patients (n = 9; Table S1 and Fig. 6 B). These subsets clustered separately, highlighting the distinct chromatin accessibility profiles of these populations (Fig. 7 G). In keeping with our transcriptomic analyses (Fig. 1 E), we identified greater chromatin accessibility within 5 kb of the transcriptional start site of the CD103 (ITGAE) and KLF3 loci in the TRM and non-TRM compartment, respectively. Furthermore, consistent with single-cell transcriptional data, the TIM3+IL7R− TRM cells when compared with non-TRM cells showed increased chromatin accessibility of genes encoding effector molecules such as granzyme B and IFN-γ, despite showing increased accessibility at the PDCD1 (PD-1) and TIM-3 (HAVCR2) loci (Fig. 7 H). Taken together, these epigenetic and transcriptomic data, combined with protein validation, highlight the potential functionality of TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM cells, which positively correlate with expression of PD-1 specifically in this subset.

Discussion

Our bulk and single-cell transcriptomic analysis showed that the molecular program of tumor-infiltrating TRM cells is substantially distinct from that observed in the human background lung tissue or murine models. The most striking discovery was the identification of a TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM subset present exclusively in tumors. This subset expressed high levels of PD-1 and other molecules previously thought to reflect exhaustion. Surprisingly, however, they proliferated in the tumor milieu, were capable of robust up-regulation of TCR activation–induced genes, and exhibited a transcriptional program indicative of superior effector, survival, and tissue-residency properties. Functionality may not be truly reflected by transcript expression levels; hence, to support the conclusion that PD-1 expression does not reflect exhaustion in TRM cells, we showed that the expression of the key effector cytokines, IL-2, TNF, and IFN-γ and the cytotoxicity molecules granzyme A and granzyme B was increased in PD-1–expressing TRM cells when compared with non-TRM cells. When compared with recent reports on transcriptomic analysis of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (Guo et al., 2018; Savas et al., 2018), our in-depth study of TRM cells in tumor and lungs clarifies the impact of PD-1 expression in different CTL subsets in the tumor and challenges the current dogma of PD-1 expression representing dysfunctional T cells in human tumors. While this protein-validated transcriptomic assessment was also corroborated by the results of a chromatin accessibility profile, an important caveat is that functional validation was performed using PMA and ionomycin stimulation, which does not fully reflect physiological TCR activation.

We defined a core set of genes commonly expressed in both lung and tumor TRM cells, including a number of novel genes whose expression was highly correlated with known TRM genes. Any of these genes may also be critically important for the development, trafficking, or function of lung or lung tumor-infiltrating TRM cells. Some notable examples known or likely to have such functions are GPR25, whose closest homologue, GPR15 (Kim et al., 2013), enables homing of T cell subsets to and retention in the colon; AMICA1 (Witherden et al., 2010), encoding JAML (junctional adhesion molecule-like), which contributes to the proliferation and cytokine release of skin-resident γδT cells; and SRGAP3, whose product functions in neuronal migration (Bacon et al., 2013). Thus, our study provides a valuable resource for defining molecules that are likely to be important for the development and function of human lung and tumor TRM cells.

PDCD1 was a prominent hit in the “shared lung tissue residency” gene list, and its expression was confirmed at the protein level in both lung and tumor TRM cells. The fact that PD-1 was expressed by the majority of the TRM cells isolated from uninvolved lung tissue of subjects with no active infection suggests that PD-1 might be constitutively expressed by these cells, as has been recently described for brain TRM cells (Shwetank et al., 2017). Given that TIM-3+IL7R− expressing tumor-infiltrating TRM cells also express substantial levels of PD-1, we speculate that they may be the major cellular targets of anti-PD-1 therapy. We speculate that differences in the magnitude of this population of TRMs could thus be an explanation for the variation in the clinical response to PD-1 inhibitors. We speculate further that the constitutive expression of PD-1 by the majority of TRM cells in the lung tissue and presumably other organs (skin and pituitary gland) raises the possibility that anti-PD-1 therapy may nonspecifically activate potentially non–TAA-reactive TRM cells to cause adverse immune reactions such as pneumonitis, dermatitis, and hypophysitis (June et al., 2017). Comprehensive analysis of the TRM phenotype and TCR repertoire of CTLs present in tumor and organs affected by adverse reactions may substantiate these hypotheses. A recent study that compared PD-1high versus other tumor-localized CTL populations demonstrated that the presence of PD-1high cells was predictive of response to anti-PD-1 therapy (Thommen et al., 2018). However, the authors did not segregate PD-1high cells based on expression of TRM-associated molecules; hence, this population of cells will have a mixture of PD-1+ non-TRM cells and PD-1+ TRM cells. Our findings have highlighted the profound differences in the properties of PD-1–expressing TRM cells and non-TRM cells. Hence, by studying a mixed population without delineating the contribution from PD-1–expressing TRM cells, their study lacked the resolution to highlight the contribution of a specific TRM subsets with transcriptomic features associated with increased functional properties and potential responsiveness to anti-PD-1 therapy.

Our findings also raise the question of which molecular players are essential for the generation and maintenance of this TIM-3+IL-R7− subset of TRM cells. Our analysis identified a number of potential transcription factors (e.g., STAT3, ID2, ZEB2, and ETS-1) and other molecules (e.g., PTPN22, DUSP4, LAYN, KRT86, and CD39) that are uniquely expressed in this subset and could thus be key players in their development or function, further underscoring the utility of the resource generated here.

The results herein also provide a rationale for assessing tumor TRM subsets in both early- and late-phase studies of novel immunotherapies and cancer vaccines to provide early proof of efficacy as well as potential response biomarkers. The TIM-3+IL-7R− TRM subset can be readily isolated from tumor samples using the surface markers we identified and potentially expanded in vitro to screen and test for TRM-targeted T cell therapies. In summary, our studies have provided rich molecular insights into the potential roles of human tumor–infiltrating TRM subsets and thus should pave the way for developing novel approaches to improve TRM immune responses in cancer.

Materials and methods

Ethics and sample processing

The Southampton and South West Hampshire Research Ethics Committee approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (Ganesan et al., 2017). Newly diagnosed, untreated patients with respiratory malignancies or HNSCC were prospectively recruited once referred (Chee et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2017). Freshly resected tumor tissue and, where available, matched adjacent nontumor tissue was obtained from lung cancer patients following surgical resection. HNSCC tumors were macroscopically dissected and slowly frozen in 90% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 10% DMSO (Sigma) for storage, until samples could be prepared. Pre– and post–anti-PD-1 therapy samples were frozen as per HNSCC samples.

Flow cytometry of fresh material

Samples were processed as described previously (Wood et al., 2016; Ganesan et al., 2017). For sorting of fresh CTLs for population transcriptomic analysis, cells were first incubated at 4°C with Fc receptor (FcR) block (Miltenyi Biotec) for 10 min and then stained with a mixture of the following antibodies: anti-CD45-FITC (HI30; BioLegend), anti-CD4-PE (OKT4; BD Biosciences), anti-CD3-APC-Cy7 (SK7; BioLegend), anti-CD8A-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK1; BioLegend), and anti-CD103-APC (Ber-ACT8; BioLegend) for 30 min at 4°C. Live/dead discrimination was by DAPI staining (Wood et al., 2016; Ganesan et al., 2017). CTLs were sorted based on CD103 expression using a BD FACSAria-II (BD Biosciences) into ice-cold TRIzol LS reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Flow cytometry of cryopreserved material

For single-cell transcriptomic, stimulation assays, and phenotypic characterization, tumor and lung samples were first dispersed (as above) and cryopreserved in freezing media (50% complete RPMI (Fisher Scientific), 40% human decomplemented AB serum, 10% DMSO (both Sigma). Cryopreserved samples were thawed, washed twice with prewarmed (37°C) and room temperature MACS buffer, and prepared for staining as above. The second wash included an underlayer of FBS to help collect debris. The material was stained with a combination of anti-CD45-Alexa Fluor 700 (HI30; BioLegend), anti-CD3-APC-Cy7 (SK7; BioLegend), anti-CD8A-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK1; BioLegend), and anti-CD103-Pe-Cy7 (Ber-ACT8; BioLegend). Cells were counterstained where described with anti-CD19/20 (HIB19/2H7; BioLegend), anti-CD14 (HCD14; BioLegend), anti-CD56 (HCD56; BioLegend), and anti-CD4 (OKT4; BioLegend) for flow cytometric analysis and sorting. Live and dead cells were discriminated using propidium iodide (PI). Cells were stimulated for transcriptomic analysis when noted, with PMA and ionomycin, as previously described (Ganesan et al., 2017). For 10X single-cell transcriptomic analysis (10X Genomics), 1,500 cells each of CD103+ and CD103− CTLs from tumor and lung samples were sorted and mixed into 50% ice-cold PBS, 50% FBS (Sigma) on a BD Aria-II or Fusion cell sorter. From the 12 patients used for 10X genomics, matched lung tissue was used from 6 of these patients. For assessments of the bulk transcriptome following stimulation, CTLs were collected by sorting 200 cells into 8 µl lysis buffer (Triton X-100 [0.1%] containing RNase inhibitor [1 U/µl and deoxyribonucleotide triphosphate mix (2.5 mM) on an Aria-II (BD)]); for Smart-seq2–based single-cell analysis, CTLs were sorted as above, using single-cell purity, into 4 µl lysis buffer on a BD Aria-II, as described previously (Picelli et al., 2014; Engel et al., 2016; Patil et al., 2018).

For tumor TRM phenotyping in treatment-naive patients, samples were analyzed on a FACS-Fusion (BD) following staining with anti-CD45-Alexa Fluor 700 (HI30; BioLegend), anti-CD3-APC-Cy7 (SK7; BioLegend), anti-CD8A-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK1; BioLegend), anti-CD103-Pe-Cy7 (Ber-ACT8; BioLegend), anti-CD127-APC (eBioRDR5; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-CD39-BB515 (TU66; BD), anti-4-1BB-PE (4B4-1; BioLegend), anti-PD-1-BV421 (EH12.1; BD), and anti-TIM-3-BV605 (F38-2E2; BioLegend). Cells were counterstained where described with anti-CD19/20-PE-Dazzle (HIB19/2H7; BioLegend), anti-CD14-PE-Dazzle (HCD14; BioLegend), anti-CD56-BV570 (HCD56; BioLegend), and anti-CD4-BV510 (OKT4; BioLegend). Dead cells were discriminated using PI. Phenotypic characterization of lung TRM cells was completed using the antibodies above with anti-CD49A-PE (SR84; BD) and anti-KLRG1-APC (2F1/KLRG1; BioLegend) on an LSRII (BD) using a gating strategy previously described (Ganesan et al., 2017).

For paired analyses of patients before and after anti-PD-1 treatment, we collected tissue from patients with metastatic melanoma (patients 53–54; Tables S1 and S12) before the first dose and after 6 wk of immunotherapy. Patient 53 received ipilimumab at 3 mg/kg and nivolumab 1 mg/kg at three weekly intervals. Patient 54 was treated with pembrolizumab at 2 mg/kg, given once every 3 wk. Both patients achieved a complete remission. Biopsy specimens were cryopreserved in 90% FBS, 10% DMSO until data acquisition. Phenotypic characterization of TRM cell samples before and after immunotherapy was completed by thawing the material and dispersing the biopsies using mechanical and enzymatic digestion, as described previously (Wood et al., 2016; Ganesan et al., 2017). Cells were stained as above and sorted into 2 µl lysis buffer on a BD Aria-II as described above (Picelli et al., 2014; Engel et al., 2016; Patil et al., 2018). Live, singlet, CD14−CD19−CD20−CD45+CD3+ or CD14−CD19−CD20−CD45+CD3+CD8+ cells (depending upon the amount of the material available) were then index sorted on a BD Aria-II using the reagents described above. The data were then concatenated in FlowJo (v10.4.1) and, if required, CD8+CD4−CD103+ CTLs were then further isolated in silico based on protein and/or gene expression data and the analysis completed as described in the RNA-seq section below. Flow cytometry analysis of the remaining donors were completed as above using anti-CD45-Alexa-R700 (HI30; BD), anti-CD3-PE-Dazzle (SK7; BioLegend), anti-CD20-APC-Cy7 (2H7; BioLegend), anti-CD14-APC-Cy7 (HCD14; BioLegend), anti-CD8A-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK1; BioLegend), anti-CD103-Pe-Cy7 (Ber-ACT8; BioLegend), anti-CD127-APC (eBioRDR5; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-PD-1-BV421 (EH12.1; BD), and anti-TIM-3-BV605 (F38-2E2; BioLegend), and live/dead discrimination was completed with fixable/live dead (Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780; Thermo Fisher Scientific). The cytometric analysis was completed on a Fusion cell sorter (BD). Samples that had <100 CTLs were removed from further analysis.

Flow cytometry–based intracellular protein validation was completed by thawing and washing samples as described above. The samples were incubated for 10 min at 4°C with FcR block as above and then stained using a combination of anti-CD45-Alexa-R700 (HI30; BD), anti-CD3-PE-Dazzle (SK7; BioLegend), anti-CD20-APC-Cy7 (2H7; BioLegend), anti-CD14-APC-Cy7 (HCD14; BioLegend), anti-CD4-BV510 (OKT4; BioLegend), anti-CD8A-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK1; BioLegend), anti-CD103-Pe-Cy7 (Ber-ACT8; BioLegend), anti-CD127-APC (eBioRDR5; Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-PD-1-BV421 (EH12.1; BD), and live/dead discrimination was completed with fixable/live dead (Fixable Viability Dye eFluor 780; Thermo Fisher Scientific). TIM-3 staining following ex vivo stimulation and fixation was affected, thus limiting our ability to study the intracellular cytokine profile of TIM-3+ cells directly. The sample was then washed and material for ex vivo quantification was immediately fixed (Fixation and Permeabilization Solution; BD) for 20 min at room temperature. The sample was then washed in permeabilization wash (Intracellular Staining Permeabilization Wash Buffer; BioLegend). The sample then received additional FcR blocking reagent and was stained with anti-granzyme B–PE (REA226; Miltenyi Biotec) and anti-Granzyme A–Alexa Fluor 647 (CB9; BioLegend) for 30 min at 4°C. Following this, the material was washed in Permeabilization Wash Buffer. For samples analyzed for ex vivo cytokine production, fixable/live dead was added after 3 h of the stimulation to account for any changes in cell viability during stimulation. For PMA/ionomycin analysis, the cell suspension was stimulated in for 4 h at 37°C in an incubator, at 5% CO2, in 200 µl complete RPMI with Cell Activation Cocktail (with Brefeldin A; BioLegend) as per the manufacturer’s recommendation. Following the addition of further FcR blocking reagent, cytokine staining was completed with anti-IL-2-PE (MQ1-17H12; BioLegend), anti-IFN-γ-BV785 (4S.B3; BioLegend), and anti-TNF-APC (MAb11; BioLegend). Data acquisition was completed on a Fortessa (BD), using a gating strategy previously described (Ganesan et al., 2017) and data were analyzed as above. One sample with <100 total CTLs quantified was removed.

All FACS data were analyzed in FlowJo (v10.4.1), and geometric-mean florescence intensity and population percentage data were exported and visualized in GraphPad Prism (v7.0a; Treestar). For t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (tSNE) and coexpression analysis of flow cytometry data, each sample was down-sampled to exactly 3,000 randomly selected live and singlet-gated, CD14−CD19−CD20−CD4−CD56−CD45+CD3+CD8+ CTLs using the gating strategy described above, and 24,000 cells each from the lung and tumor samples were merged to yield 48,000 total cells. A tSNE plot was constructed using 1,000 permutations and default settings in FlowJo (v10.4.1), z-score expression was mean centered. Flow cytometry data were exported from FlowJo (using the channel values) and these data were imported into R for coexpression analysis (described below).

Bulk RNA-seq and TCR sequencing (TCR-seq)

Total RNA was purified using a miRNAeasy kit (Qiagen) from CD103+ and CD103− CTLs and quantified as described previously (Engel et al., 2016; Ganesan et al., 2017). For assessment of the stimulated transcriptome, RNA from ∼100 sorted cells was used. Total RNA was amplified according to the Smart-seq2 protocol (Picelli et al., 2014). cDNA was purified using AMPure XP beads (0.9:1 ratio; Beckman Coulter). From this step, 1 ng cDNA was used to prepare a standard Nextera XT sequencing library (Nextera XT DNA sample preparation and index kits; Illumina; Ganesan et al., 2017). Samples were sequenced using an Illumina HiSeq2500 to obtain 50-bp single-end reads. For quality control, steps were included to determine total RNA quality and quantity, the optimal number of PCR preamplification cycles, and cDNA fragment size. Samples that failed quality control or had a low number of starting cells were eliminated from further sequencing and analysis. TCR-seq was performed as previously described (Patil et al., 2018) using Tru-seq single indexes (Illumina). Sequencing data were mapped and analyzed using MIGEC (molecular identifier groups–based error correction; Shugay et al., 2014) software (v1.2.7) with default settings, followed by V(D)J tools (v1.1.7) with default settings. Mapping quality control (QC) metrics are included in Tables S1 and S6.

10X single-cell RNA-seq

Samples were processed using 10X v2 chemistry as per the manufacturer’s recommendations; 11 and 12 cycles were used for cDNA amplification and library preparation, respectively (Patil et al., 2018). To minimize experimental batch effects, cells were sorted from groups of six donors each day, and cells were pooled for 10X sequencing library preparation. Barcoded RNA was collected and processed following the manufacturer recommendations, as described previously. Libraries were sequenced on a HiSeq2500 and HiSeq4000 (Illumina) to obtain 100- and 32-bp paired-end reads using the following read length: read 1, 26 cycles; read 2, 98 cycles; and i7 index, 8 cycles (Table S1). Samples were pooled together, and DNA samples from whole blood were extracted using a high-salt method (Miller et al., 1988) and quantified using the Qubit 2.0 (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Genotyping was completed through the Infinium Multi-Ethnic Global-8 Kit (Illumina) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Raw data from the genotyping analysis were exported using the Genotyping module and Plug-in PLINK Input Report Plug-in (v2.1.4) from GenomeStudio v2.0.4 (Illumina). Data quality was assessed using the snpQC package (Gondro et al., 2014) with R, and low-quality single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were detected; SNPs failing in >5% of the samples and SNPs with Illumina’s gene call scores <0.2 in >10% of the samples were flagged. Each subject’s sex was matched with the genotype data, and flagged SNPs were removed for downstream analysis using PLINK (v1.90b3w; Purcell et al., 2007). Genetic multiplexing of barcoded single-cell RNA-seq was completed using Demuxlet (Kang et al., 2018) and matched with the Seurat output. Cells with ambiguous or doublet identification were removed from analysis of cluster and/or donor proportions.

Bulk RNA-seq analysis

Bulk RNA-seq data were mapped against the hg19 reference using TopHat (Trapnell et al., 2009; v2.0.9 (--library-type fr-unstranded --no-coverage-search) with FastQC (v0.11.2), Bowtie (v2.1.0.0; Langmead et al., 2009), and Samtools v0.1.19.0; Li and Durbin, 2009), and we employed htseq-count -m union -s no -t exon -i gene_name (part of the HTSeq framework, version v0.7.1; Anders et al., 2015). Trimmomatic (v0.36) was used to remove adapters (Bolger et al., 2014). Values throughout are displayed as log2 TPM (transcripts per million) counts; a value of 1 was added before log transformation. To identify genes expressed differentially by various cell types, we performed negative binomial tests for paired comparisons by using the Bioconductor package DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014; v1.14.1), disabling the default options for independent filtering and Cooks cutoff. We considered genes to be expressed differentially by any comparison when the DESeq2 analysis resulted in a Benjamini–Hochberg–adjusted P value of ≤0.05 and a fold change ≥ 2. Union gene signatures were calculated using the online tool jVenn (Bardou et al., 2014), of which genes must have common directionality. GSEA, correlations, and heat maps were generated as previously described (Engel et al., 2016; Ganesan et al., 2017; Patil et al., 2018). Genes used in the GSEA are shown (Table S3). For the preservation of complementary signatures, read count data from Cheuk et al. (2017) were downloaded from Gene Expression Omnibus accession no. GSE83637, and differential expression analysis was completed as above. For the murine composite signature (Milner et al., 2017), orthologues between human and murine signatures were compared using Ensembl to facilitate converting from the murine to human signature; genes that had opposing expression changes were not considered conserved (Table S3). Reactome pathways were generated using the online tool (https://reactome.org/) for tumor TRM-specific genes; a pathway was considered significantly different if the false discovery rate (FDR; q) value was ≤0.05; Table S4). Visualizations were generated in ggplot2 using custom scripts, while expression values were calculated using GraphPad Prism7 (v7.0a). For tSNE analysis, the data frame was filtered to genes with mean ≥1 TPM counts expression in at least one condition and visualizations created using the top 2,000 most variable genes, as calculated in DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014; v1.16.1); this allowed for unbiased visualization of the log2 (TPM counts + 1) data using package Rtsne (v0.13). Coexpression networks were generated in gplots (v3.0.1) using the heatmap2 function, while weighted correlation analysis was completed using WGCNA (Langfelder and Horvath, 2008; v1.61) from the log2 (TPM counts + 1) data matrix and the function TOMsimilarityfromExpr (Beta = 5) and exportNetworkToCytoscape, weighted = true, threshold = 0.05. Highlighted genes were ordered as per the order in the correlation plot. Networks were generated in Gephi (v0.92; Mellone et al., 2016; Ottensmeier et al., 2016) using Fruchterman Reingold and Noverlap functions. The size and color were scaled according to the Average Degree as calculated in Gephi, while the edge width was scaled according to the WGCNA edge weight value. The statistical analysis of the overlap between gene sets was calculated in R (v3.5.0) using the fisher.test function (Stats v3.5.0) using the number of total quantified genes used for DESeq2, as the total value (20,231), with alternative=“greater”.

Single-cell RNA-seq analysis

Raw 10X data (Table S1) were processed as previously described (Patil et al., 2018), merging multiple sequencing runs using cellranger count function in cell ranger and then merging multiple cell types with cell ranger aggr (v2.0.2). The merged data were transferred to the R statistical environment for analysis using the package Seurat (v2.2.1; Macosko et al., 2015; Patil et al., 2018). Only cells expressing >200 genes and genes expressed in ≥3 cells were included in the analysis. The data were then log-normalized and scaled per cell and variable genes were detected. Transcriptomic data from each cell was then further normalized by the number of UMI-detected and mitochondrial genes. A PC analysis (PCA) was then run on variable genes, and the first eight PCs were selected for further analyses based on the standard deviation of PCs, as determined by an “elbow plot” in Seurat. Cells were clustered using the FindClusters function in Seurat with default settings, resolution = 0.6 and eight PCs. Differential expression between clusters was determined by converting the data to counts per million and analyzing cluster-specific differences using MAST (q ≤ 0.01, v1.2.1; Finak et al., 2015; Patil et al., 2018; Soneson and Robinson, 2018). A gene was considered significantly different only if the gene was commonly positively enriched in every comparison for a singular cluster (Engel et al., 2016; Patil et al., 2018). Further visualizations of exported normalized data were generated using the Seurat package and custom R scripts. Cell-state hierarchy maps were generated using Monocle (v2.6.1; Trapnell et al., 2014) and default settings with expressionFamily = negbinomial.size(), lowerDetectionLimit = 1 and mean_expression ≥ 0.1, including the most variable genes identified in Seurat for consistency. Average expression across a cell cluster was calculated using the AverageExpression function, and down-sampling was achieved using the SubsetData function (both in Seurat). Distance between clusters was calculated by calculating a particular cells location in PCA space (PC 1:3) using the function GetCellembeddings (in Seurat), and the values for each cell were then scaled per column (Scale function, core R) where described; finally, a distance matrix was calculated (dist function, core R, method = Euclidean). This matrix was filtered to the cells assigned to cluster 1, and the mean distance of each cell in cluster 1 to all cells in each of the remaining TRM clusters (2, 3, 4, and 5) was calculated. The clustering analysis was completed using the hclust function in R (Stats, R v3.5.0) with average linkage and generated from the Spearman correlation analysis of each cell’s location in PCA space (as above). SAVER coexpression analysis (Huang et al., 2018) was completed on the raw-UMI counts of the TRM cells (clusters 1–5) and the non-TRM cells (remaining cells) using the function saver (v1.1.1) with pred.genes.only = TRUE, estimates.only = FALSE on transcripts assigned as uniquely enriched in cluster 2, removing genes not expressed in any cells in the non-TRM compartment. Correlation values were isolated using the cor.genes function in SAVER and coexpression plots generated as described above.

Smart-seq2 single-cell analysis (Table S1) was completed as previously described using TraCeR (v0.5.1; Stubbington et al., 2016; Patil et al., 2018) and custom scripts to identify αβ chains, showing only cells were both TCR chains were detected and to remove cells with low QC values as previously described (Patil et al., 2018). Here, we removed cells with <200,000 reads, and <30% of sequenced bases were assigned to untranslated regions and coding regions of mRNA. Samples were mapped as described previously (Patil et al., 2018), and the data were log transformed and displayed as normalized TPM counts; a value of 1 was added before log transformation. Visualizations were completed in ggplot2, Prism (v7.0a) and custom scripts in TraCer. A cell was considered expanded when both the most highly expressed α and β TCR chain sequences matched other cells with the same stringent criteria. Cells were considered not expanded when neither α nor β TCR productive chain sequences matched those of any other cells. A cell was considered PD-1+ or TIM-3+ when the expression of PDCD1 or HAVCR2 was >10 TPM counts, while a cell was considered cycling if expression of cell cycle genes TOP2A and/or MKI67 was >10 TPM counts. Differential expression profiling was completed using MAST (Finak et al., 2015; q ≤ 0.05), as previously described (Patil et al., 2018).

Matched flow cytometry data were analyzed using FlowJo (v10.4.1), values and gates were exported into ggplot and “in-silico gates” were applied using custom scripts in R. Given ∼85% of the CD103+ cells were TIM-3+ from our flow cytometry data, cells were broadly classified into TRM or non-TRM based on an individual cell’s protein expression (FACS gating) for patient 53. Where there was no available cell-specific associated protein data (patient 54), CD3+ T cells were classified based on the lack of expression of CD4 and FOXP3 to enable removal of CD4+ cells. Next, we stratified the single-cell transcriptomes into TRM or non-TRM cells when expression of TRM-associated genes, ITGAE (CD103), RBPJ, and/or ZNF683 (HOBIT) was >10 TPM counts; the classification of each single-cell library is summarized in Table S12. Differential gene expression analysis was completed as above.

Multiplex immunohistochemistry

Patients included in this cohort had a known diagnosis of lung cancer. 23 patients were selected in total, categorizing the donors using criteria previously reported (Ganesan et al., 2017). A multiplexed IHC method was used for repeated staining of a single paraffin-embedded tissue slide. Deparaffinization, rehydration, antigen retrieval, and IHC staining were performed using a Dako PT Link Autostainer. Antigen retrieval was performed using the EnVision FLEX Target Retrieval Solution, High pH (Agilent Dako) for all antibodies. The slide was first stained with a standard primary antibody followed by an appropriate biotin-linked secondary antibody and HRP-conjugated streptavidin to amplify the signal. Peroxidase-labeled compounds were revealed using 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole, an aqueous substrate that results in red staining, or 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) that results in brown staining and counterstained using hematoxylin (blue).

The slides were stained initially with Cytokeratin (prediluted, Clone AE1/AE3; Agilent Dako) and then sequentially with anti-CD8α (prediluted Kit IR62361-2; clone C8/144B; Agilent Dako), anti-CD103 (1:500; EPR4166(2); Abcam), and anti-TIM-3 (1:50; D5D5R; Cell Signaling Technology). The slides were scanned at high resolution using a Zeiss Axio Scan.Z1 with a 20× air immersion objective. Between each staining iteration, antigen retrieval was performed along with removal of the labile 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole staining and denaturation of the preceding antibodies using a set of organic solvent–based destaining buffers as follows: 50% ethanol for 2 min, 100% ethanol for 2 min, 100% xylene for 2 min, 100% ethanol for 2 min, and 50% ethanol for 2 min. This process did not affect DAB staining. The process was repeated for each of the antibodies.

Bright-field images were separated into color channels in imaging processing software ImageJ FIJI (ImageJ Windows 64-bit final version; Schindelin et al., 2012). For the TILhighTRMhigh and TILlowTRMlow tumors, the number of CD8+CD103+TIM3+ cells were quantified manually. Two samples with ≤3 CD8+CD103+ CTLs quantified were removed to prevent calculating percentages of single events, resulting in a final number of 21 samples. These images were processed and combined to create pseudocolor multiplexed images. The raw counts for each protein, individually and together, are presented in Table S11 as the number of cells per 0.15 mm2.

OMNI-ATAC-seq

CTLs were FACS sorted from cryopreserved lung cancer samples as described above using the following antibody cocktail: anti-CD45-Alexa Fluor 700 (HI30; BioLegend), anti-CD3-APC-Cy7 (SK7; BioLegend), anti-CD8A-PerCP-Cy5.5 (SK1; BioLegend), anti-CD103-Pe-Cy7 (Ber-ACT8; BioLegend), anti-CD127-APC (eBioRDR5; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and anti-TIM-3-BV605 (F38-2E2; BioLegend). Cells were counter stained with anti-CD19/20-PE-Dazzle (HIB19/2H7; BioLegend), anti-CD14-PE-Dazzle (HCD14; BioLegend), and anti-CD4-BV510 (OKT4; BioLegend). Dead cells were discriminated using PI. Samples were sorted into low-retention 1.5-ml Eppendorfs containing 250 µl FBS and 250 µl PBS. Three to six donors were pooled together to guarantee sufficient cell numbers. For each pool of cells, two or three technical replicates of 15,000–25,000 CTLs were generated for each library.

OMNI-ATAC-seq was performed as described in Corces et al. (2017), with minor modifications. Isolated nuclei were incubated with tagmentation mix (2× TD buffer, 2.5 µl transposase enzyme from Nextera kit; Illumina) at 37°C for 30 min in a thermomixer, shaking at 1,000 RPM (Corces et al., 2017). Following tagmentation, the product was eluted in 0.1X Tris-EDTA buffer using DNA Clean and Concentrator-5 kit (Zymo). The purified product was preamplified for five cycles using Kappa 2X enzyme along with Nextera indexes (Illumina), and based on quantitative PCR amplification, an additional seven cycles of amplification were performed for 20,000 cells. The PCR-amplified product was purified using DNA Clean and Concentrator-5 kit (Zymo), and size selection was done using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter). Finally, concentration and quality of libraries were determined by picogreen and bioAnalyzer assays. Equimolar libraries were sequenced as above or on a NovaSeq 6000 for sequencing.