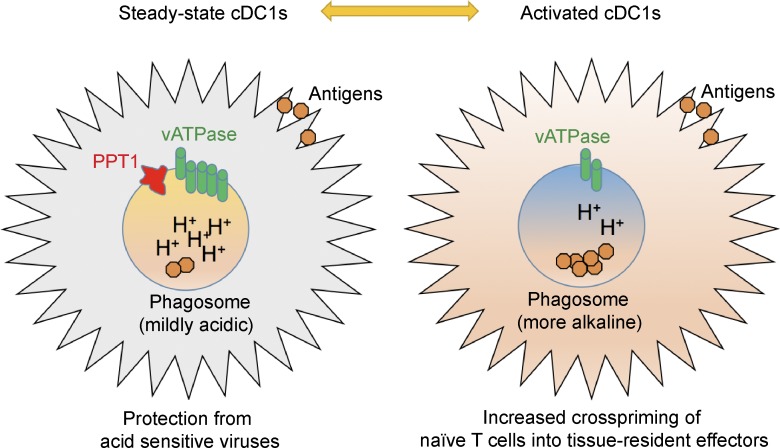

Crosspriming of CD8+ T cells by dendritic cells is crucial for host response against cancer and intracellular microbial infections. Ou et al. demonstrates that palmitoyl-protein thioesterase PPT1 is a phagosomal pH rheostat enabling both viral resistance and efficient crosspriming in cDC1s.

Abstract

Conventional type 1 dendritic cells (cDC1s) are inherently resistant to many viruses but, paradoxically, possess fewer acidic phagosomes that enable antigen retention and cross-presentation. We report that palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1), which catabolizes lipid-modified proteins in neurons, is highly expressed in cDC1s. PPT1-deficient DCs are more susceptible to vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection, and mice with PPT1 deficiency in cDC1s show impaired response to VSV. Conversely, PPT1-deficient cDC1s enhance the priming of naive CD8+ T cells into tissue-resident KLRG1+ effectors and memory T cells, resulting in rapid clearance of tumors and Listeria monocytogenes. Mechanistically, PPT1 protects steady state DCs from viruses by promoting antigen degradation and endosomal acidification via V-ATPase recruitment. After DC activation, immediate down-regulation of PPT1 is likely to facilitate efficient cross-presentation, production of costimulatory molecules and inflammatory cytokines. Thus, PPT1 acts as a molecular rheostat that allows cDC1s to crossprime efficiently without compromising viral resistance. These results suggest potential therapeutics to enhance cDC1-dependent crosspriming.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Antigen cross-presentation is an important pathway to prime CD8+ T cells in infections, cancer, and other immune-mediated pathologies (Ackerman and Cresswell, 2004; Rock and Shen, 2005). Conventional type 1 dendritic cells (cDC1s; CD8α+/CD103α+/XCR1+/DNGR-1+/BATF3-dependent DCs) are the major cross-presenting DC subset in vivo (den Haan et al., 2000; Jung et al., 2002; Hildner et al., 2008; Sancho et al., 2009; Poulin et al., 2012; Yamazaki et al., 2013; Guilliams et al., 2014; Breton et al., 2016). cDC1 development is dependent on several key transcriptional factors, such as BATF3, IRF8, ZBTB46, ID2, and ETV6 (Aliberti et al., 2003; Hacker et al., 2003; Hildner et al., 2008; Meredith et al., 2012a,b; Sichien et al., 2016; Lau et al., 2018). In addition to cDC1s, DCs derived under inflammatory conditions from hematopoietic progenitors or monocytes, and activated plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs), are also capable of cross-presentation (Helft et al., 2015; Oberkampf et al., 2018). In general, cross-presentation of exogenous antigens can occur via two major pathways. In the vacuolar pathway, antigens are directly loaded onto MHC I molecules in phagosomes. In the cytosolic pathway, antigens are exported into the cytosol and then loaded into ER or phagosomes (Joffre et al., 2012).

In cancer, cross-presentation of tumor-associated antigens is particularly crucial for an effective antitumor CD8+ T cell response (Hildner et al., 2008; Fuertes et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2016; Salmon et al., 2016; Spranger et al., 2017). In intracellular bacterial infections such as Listeria monocytogenes (LM), CD8+ T cell responses are thought to be initiated primarily by the cross-presentation of phagocytosed infected apoptotic cells (Jung et al., 2002). For certain viruses that do not directly infect DCs, crossprimed CD8+ T cells are essential to clear these infections (Sigal et al., 1999; Nair-Gupta and Blander, 2013). For intracellular pathogens that infect DCs, CD8+ T cells could also be primed by direct MHC class I presentation in infected DCs. However, it is detrimental for DCs to be infected, as intracellular infections lead to cellular damage or death, as well as manipulation of immune responses (Schwartz et al., 1996; Bowie and Unterholzner, 2008; Edelson et al., 2011). Accordingly, cDC1s had been reported to be resistant to a broad range of enveloped viruses, including HIV and the influenza virus, but their mechanism of viral resistance remains unclear (Helft et al., 2012; Silvin et al., 2017).

In comparison to macrophages, DCs maintain a higher pH in phagosomes and a lower level of lysosomal proteases (Delamarre et al., 2005). Such limited antigen degradation in DCs actually correlates with more efficient cross-presentation (Accapezzato et al., 2005; Delamarre et al., 2005). DC phagosomal pH could be regulated by NADPH oxidase 2 (NOX2), which consumes the protons generated by vacuolar H+ adenosine triphosphatase (V-ATPase; Savina et al., 2006). In turn, NOX2 recruitment to phagosomes may be mediated by several molecules such as RAB27A, VAMP-8, RAC2, and Siglec-G (Jancic et al., 2007; Savina et al., 2009; Matheoud et al., 2013; Ding et al., 2016). Additionally, phagosomal recruitment of the ER-Golgi intermediate compartment by SEC22B may raise the pH by regulating proteasomes and lipid bodies (Bougnères et al., 2009; Cebrian et al., 2011). However, acidic phagosomes are instrumental for phagocytes to deactivate and degrade endocytosed pathogens, as many proteolytic enzymes are fully functional at a lower pH (Watts, 1997). Many viruses, including the influenza virus, rabies virus, and herpes simplex virus, are sensitive to mildly acidic pH (Stegmann et al., 1987; Roche and Gaudin, 2002; Komala Sari et al., 2013). It is unclear how cDC1s manage this apparent trade-off between efficient cross-presentation and better self-protection from viruses.

To address this question, we examined the role of palmitoyl-protein thioesterase 1 (PPT1), an enzyme that cleaves thioester-linked palmitate from S-acylated proteins in lysosomes (Camp and Hofmann, 1993). PPT1 deficiency results in infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis in humans and similar symptoms in mice (Gupta et al., 2001). Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis is a lysosome storage disorder (LSD) characterized by gradual neurodegeneration in the central nervous system, leading to blindness, seizures, and early death (Vesa et al., 1995). PPT1 has been previously shown to regulate synaptic vesicle recycling at nerve terminals (Kim et al., 2008). Here we demonstrated that PPT1 maintains acidic phagosomes, whereas PPT1 down-regulation after DC activation facilitates antigen retention and phagosomal acidification. Thus PPT1-deficient DCs were susceptible to viral infections but had enhanced crosspriming of naive CD8+ T cells into tissue-resident effector and memory cells. Our results reveal a mechanistic linkage of viral resistance and efficient cross-presentation and suggest potential therapeutic approaches to treat tumors and intracellular microbial infections.

Results

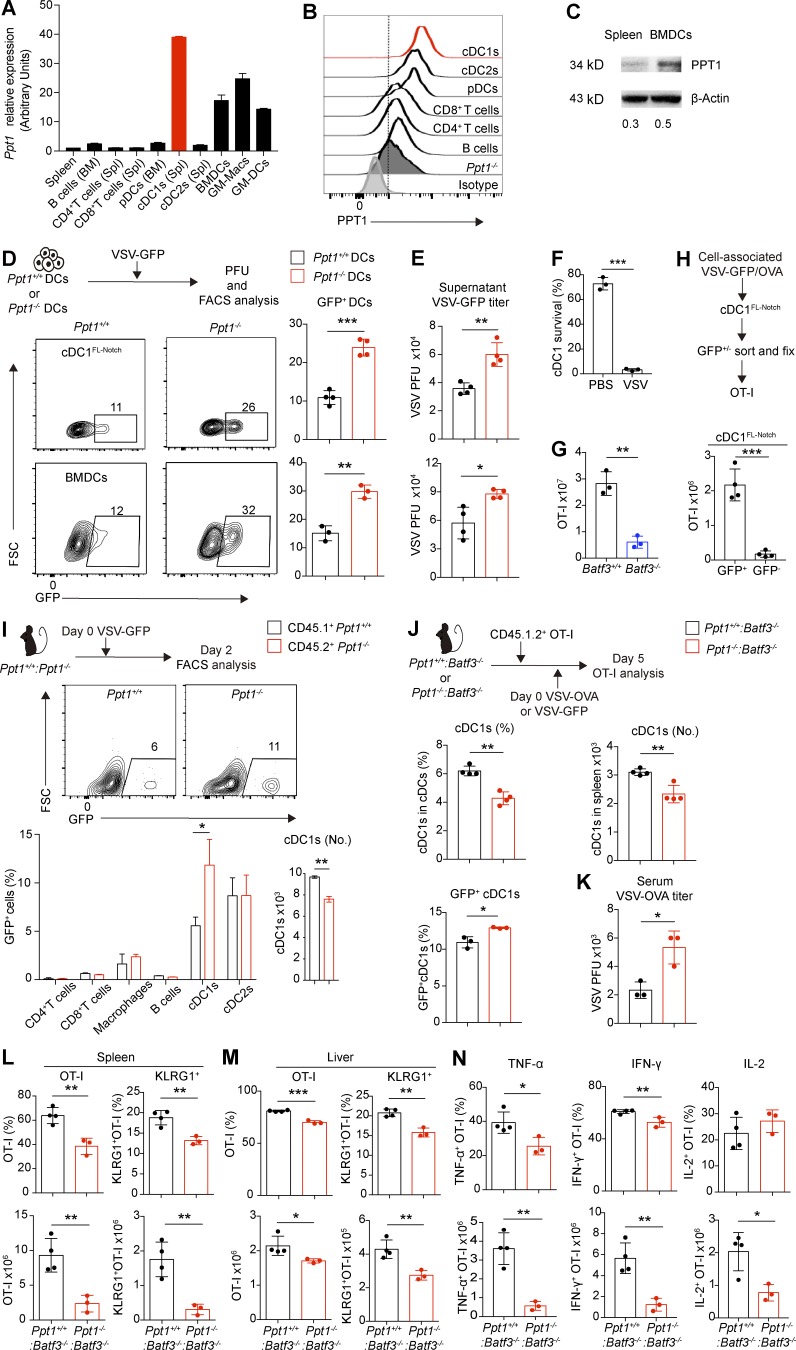

PPT1 is highly expressed in cross-presenting DCs but dispensable for their development

We first examined the specific expression of Ppt1 mRNA by quantitative PCR (qPCR) in murine C57BL/6J WT immune cell types (Fig. 1 A). We found that Ppt1 transcript is highly enriched in cDC1s. This result was also consistent with the cDC1-specific expression of Ppt1 transcript in the publicly available Immunological Genome Project (IMMGEN) gene microarray and RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) databases (Fig. S1, A and B; Heng et al., 2008). We also examined CD11b+ MHCII+ CD11c+ DCs derived from bone marrow cells in vitro with GM-CSF/IL-4 (thereafter referred as BMDCs). Ppt1 mRNA was expressed at a relatively high level in WT BMDCs and their GM-DC and GM-macrophage subpopulations (Fig. 1 A; Helft et al., 2015). We confirmed the PPT1 protein expression in WT cDC1s by intracellular staining, and in WT BMDCs by Western blotting (Fig. 1, B and C). Thus, PPT1 is highly expressed on cross-presenting DCs such as cDC1s and BMDCs.

Figure 1.

PPT1 protects DCs and host from VSV virus infection. (A) Ppt1 mRNA expression. Indicated WT immune populations were FACS sorted, and Ppt1 transcript was measured by qPCR. Data are combined results of three independent experiments (n = relative values from three independent runs). (B) PPT1 protein expression in cDC1s. Indicated splenic WT immune populations were measured by intracellular FACS staining with anti-PPT1 antibodies. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (sample from three pooled mice). (C) PPT1 protein expression in BMDCs. Indicated WT immune populations were measured by Western blotting with anti-PPT1 antibodies. β-Actin was used as loading control. Gray area ratio of PPT1 over β-actin is shown below. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (sample from three pooled mice). (D) DC susceptibility to VSV-GFP infection in vitro. Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch (top) or BMDCs (bottom) from chimeras were infected with VSV-GFP for 24 h and then analyzed by FACS. Representative FACS plots (left) and percentages (right) are shown. Data are representative one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (E) Viral titer (PFU) of supernatant from VSV-GFP–infected cDC1FL-Notch (top) or BMDCs (bottom). Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (F) Cytopathic effect of VSV on infected cDC1s. FACS sorted WT cDC1s were incubated with VSV-GFP for 12 h, and cell survival was measured by forward scatter (FSC)/side scatter live gating. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 technical replicates). (G) OT-I response in Batf3−/− mice. WT and Batf3−/− mice were injected with CD45.1+ OT-I T cells and then infected with VSV-OVA. Splenic total OT-I cell numbers at day 6 are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (H) Crosspriming by VSV-infected DCs. WT cDC1FL-Notch were fed with cell-associated VSV-GFP/OVA and then FACS sorted based on GFP fluorescence. cDC1FL-Notch were then fixed and incubated with OT-I cells for 3 d. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 technical replicates). (I) cDC1 susceptibility to VSV-GFP infection in vivo. Ppt1+/+:Ppt1−/− chimeras were infected with VSV-GFP. Spleen were analyzed at day 2. Representative FACS plot of cDC1s (top), GFP+ percentages (left), and cDC1 cell number (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (J) cDC1 susceptibility to VSV-GFP infection in vivo. Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were injected with CD45.1.2+ OT-I T cells and the next day infected with VSV-GFP or VSV-OVA. cDC1 percentage (left) and cell numbers (center) and GFP+ cDC1s (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3–4 mice per group). (K) Serum viral titer (PFU) during VSV-OVA infection. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (L) Splenic OT-I effector response. OT-I (I, left, gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ CD45.1.2+) and KLRG1+ OT-I cells (I, right), percentages (I, top), and cell numbers (I, bottom) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3–4 mice per group). (M) Liver OT-I effector response. Percentages (top) and cell numbers (bottom) of OT-I (left) and KLRG1+ (right) OT-I cells are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3–4 mice per group). (N) Cytokine production by splenic OT-I cells. Splenic cells were stimulated with SIINFEKL and analyzed by intracellular FACS staining. Percentages (top) and cell numbers (bottom) of OT-I cells that produced TNF-α (left), IFN-γ (center), and IL-2 (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3–4 mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated by two-way Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

PPT1 germline knockout mice (Ppt1−/− mice) suffer from severe neuropathology and death (commencing at ∼6 mo of age; Gupta et al., 2001). Thus, to avoid the adverse effects of the neuropathology on the immune system, we generated traditional chimeras in which lethally irradiated CD45.1+ hosts were reconstituted from Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− bone marrow cells (hereafter referred to as Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− chimeras; Fig. S1 D). In addition, we generated two types of mixed bone marrow chimeras. First, we reconstituted lethally irradiated CD45.1.2+ hosts with CD45.2+ Ppt1−/− bone marrow cells, mixed with equal numbers of WT CD45.1+ bone marrow cells (hereafter referred to as Ppt1+/+:Ppt1−/− chimeras; Fig. S1 E). Second, we reconstituted lethally irradiated CD45.1+ hosts with Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− bone marrow cells, mixed with cDC1-deficient Batf3−/− bone marrow cells. Thus, we generated mice carrying a specific deletion of PPT1 in cDC1s (hereafter referred to as Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras; Fig. S1 F). We observed no defects in cDC1 percentages or cell numbers in spleen or lymph nodes in Ppt1−/− mice or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. S2, A–E). Since Ppt1−/− mice engage in hyperaggressive behavior at an early age, we did not use their bone marrow cells directly for BMDCs (Gupta et al., 2001). Instead, we generated BMDCs only from Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− chimeras. BMDCs from Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− chimeras (hereafter referred to as Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras) were also generated at the same percentages and cell numbers (Fig. S2, F and G). All other major immune cell types appeared to be normal (Fig. S2, H and I). In addition, we cultured Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− chimera bone marrow cells with Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (FLT3L) and OP9 stromal cells expressing the Notch ligand Delta-like 1 (OP9-DL1; Kirkling et al., 2018). These cDC1-like (DEC205+ CD24+ CD8α+ CD11b− MHCII+ CD11c+) cells (hereafter referred as cDC1FL-Notch) were also generated normally from PPT1-deficient cells (Fig. S2 J). Thus, we conclude that PPT1 is dispensable for the development of DCs.

PPT1 protects DCs and host from vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection

The highly cytopathic and pantropic VSV induces a strong cytotoxic T cell response that is primed largely by cDC1s (Lichty et al., 2004; Alexandre et al., 2016). After infecting Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras with VSV expressing recombinant GFP (VSV-GFP) in vitro, we found that there were more than twofold more VSV-GFP+ Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 1 D). This difference could be due to either increased antigen uptake or an increased viral load in Ppt1−/− DCs. To see if PPT1 regulates phagocytosis, we fed Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras with fluorescent plastic beads and measured the number of beads engulfed by DCs. We observed no differences in bead phagocytosis between Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. S3 A). We also performed an in vivo antigen phagocytosis assay with FITC antigen spread on the skin of Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− mice and observed the intake of FITC by DCs in the skin-draining lymph nodes (Tussiwand et al., 2015). Similar to our in vitro assay, we saw no difference in FITC retention in vivo in either migratory or resident cDC1s in Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− mice (Fig. S3, B and C). Next, we specifically examined active virions contained in DCs by performing a plaque-forming assay using the supernatant of infected BMDCs. We found more infectious VSV virions in the Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs supernatant than that of Ppt1+/+ DCs from chimeras (Fig. 1 E). Our results show that PPT1-deficient DCs were more susceptible to VSV infection in vitro.

To determine if VSV is cytopathic to cDC1s, we infected WT cDC1s in vitro with VSV-GFP. We confirmed that VSV is indeed capable of lysing cDC1s efficiently (Fig. 1 F). Since Batf3−/− mice lack cDC1s, they had a significantly diminished antiviral OT-I response (Fig. 1 G). To make sure that VSV-infected DCs are primarily responsible for the cross-presentation of cell-associated antigens, we pulsed WT cDC1FL-Notch with cell-associated VSV-GFP/OVA, then sorted and fixed GFP+/− DCs. After incubating DCs with OT-I cells, we found that GFP+ cDC1FL-Notch induced a >10-fold stronger OT-I response than GFP− cDC1FL-Notch (Fig. 1 H). These data suggest that VSV-GFP+ DCs presented more cell-associated antigens and might be primarily responsible for T cell priming.

We then infected Ppt1+/+:Ppt1−/− chimeras with VSV-GFP and found that Ppt1−/− cDC1s had more than twofold increased VSV-GFP+ staining and a reduction in total cell numbers compared with Ppt1+/+ cDC1s, while the infection rate of other lineages (cDC2s, T and B cells, and macrophages) were unaffected by PPT1 deficiency (Fig. 1 I). We also infected Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras with VSV-GFP in vivo. Consistently, there were fewer surviving cDC1s are found in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 1 J). Among the surviving cDC1s, more GFP+ cDC1s were present in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 1 J). The VSV viral titer was more than twofold higher in the serum of VSV-infected Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with that of Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 1 K). Next, we examined the antigen-specific CD8+ T cell response in VSV-expressing recombinant ovalbumin (VSV-OVA)–infected Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras. We observed more than fourfold fewer OVA-specific TCR transgenic OT-I cells in the spleen (Fig. 1 L). We further examined the distribution of effector memory subsets, since killer cell lectin-like receptor family G, member 1–positive (KLRG1+) IL-7Rα− effector CD8+ T cells are driven by inflammatory signals provided by DCs (Joshi et al., 2007). There were more than threefold fewer KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effector OT-I cells in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 1 L). We also observed a similar reduction of OT-I cells and KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effector in the liver (Fig. 1 M). IFN-γ– and TNF-α–producing OT-I CD8+ T cells decreased by at least fourfold in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 1 N). Thus, we found that Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras had diminished CD8+ T cell response to VSV infection compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras, likely due to increased infection rates and reduced survival of PPT1-deficient cDC1s.

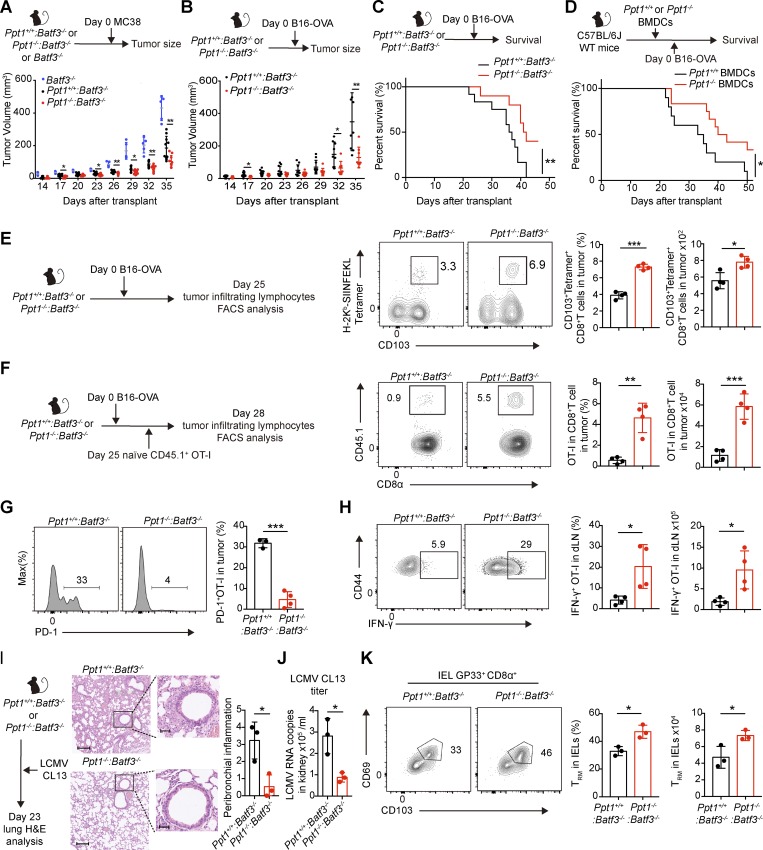

PPT1-deficient cDC1s enhance antitumor immune response

Unlike VSV, cancerous cells pose no immediate existential threat to cDC1s. cDC1s not only crossprime tumor-specific CD8+ T cells, but also enhance checkpoint-blockade efficacy (Salmon et al., 2016). We used two tumor transplantation models, MC38 colorectal and B16F10 melanoma cancer, to examine the effect of PPT1 deficiency in cDC1s during the antitumor immune response. After transplanting Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− and Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras with MC38 or B16F10 stably transfected with recombinant OVA (B16-OVA), we observed more than two-fold smaller MC38 and B16-OVA tumors in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras than those of Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras at day 35 (Fig. 2, A and B). Consistent with previous reports, Batf3−/− mice, which lack crosspriming cDC1s, had >2 fold larger MC38 tumors than Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras at day 35 (Hildner et al., 2008; Fig. 2 A). The lower B16-OVA tumor burden in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras resulted in a higher survival rate compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 2 C). Next, we adoptively transferred equal numbers of Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras into WT mice transplanted with B16-OVA, and mice that received Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras had a higher survival rate than mice that received Ppt1+/+ BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 2 D). Thus, we conclude that PPT1 deficiency in cDC1s inhibits tumor growth.

Figure 2.

PPT1-deficient cDC1s enhance antitumor immune response. (A) MC38 tumor growth curve. Batf3−/− mice, Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/−, or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were transplanted with MC38. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (Batf3−/−, n = 5 mice; Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/−, n = 10 mice). (B) B16-OVA tumor growth curve. Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were transplanted with B16-OVA. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/−, n = 12 mice; Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/−, n = 9 mice). (C) B16-OVA survival curve of chimeras. Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were transplanted with B16-OVA. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/−, n = 12 mice; Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/−, n = 9 mice). (D) B16-OVA survival curve of WT mice receiving BMDCs from chimeras. WT mice received Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras, and then were transplanted with B16-OVA. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (Ppt1+/+, n = 10 mice; Ppt1−/−, n = 12 mice). (E) Tumor-infiltrating antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were transplanted with B16-OVA, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ B220− cells) from solid tumors were analyzed at day 25 by FACS. Percentages (left) and cell numbers (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (F) Tumor-infiltrating OT-I cells. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (gated on live CD8α+CD44+ cells) were analyzed by FACS in solid tumors from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras with B16-OVA xenograft. Percentages (left) and cell numbers (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (G) PD-1 expression on tumor-infiltrating OT-I cells. OT-I cells (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ CD45.1.2+ cells) were analyzed in solid tumors from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras with B16-OVA xenograft. Histogram (left) and MFI (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (H) IFN-γ production of OT-I cells in tumor-draining lymph node (dLN). Tumor-draining lymph node cells (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ cells) from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras with B16-OVA xenograft were stimulated with SIINFEKL. Representative FACS plot (left), percentages (center), and cell numbers (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (I) Representative H&E lung section (left) and semiqualitative score of peribronchial inflammation (right). Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were infected with LMCV CL 13 and analyzed at day 23. Bars, 200 µm (left) or 50 µm (right). Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (J) Viral load in kidney. LCMV CL 13 viral mRNA in kidney tissue extracts were measured by qPCR. Data are combined results of three independent experiments (n = relative values from three independent runs). (K) Intraepithelial antigen-specific resident memory T cells. Intraepithelial lymphocytes (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ GP33+ B220− cells) were analyzed by FACS. Representative FACS plot (left), percentages (center), and cell numbers (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated by two-way Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). IEL, intraepithelial lymphocyte.

We then examined the endogenous antigen-specific tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells in the solid tumors of the chimeras. We found approximately twofold more CD103+ SIINFEKL-H2-Kb tetramer+ CD8+ T cells residing in the tumors at day 25 (Fig. 2 E). Next, we sought to examine the trafficking pattern of cross-primed CD8+ T cells by injecting naive OT-I CD8+ T cells into mice bearing the B16-OVA xenograft. After 3 d, we observed more than fivefold more intratumor CD44+ OT-I cells in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 2 F). Tumor-infiltrating OT-I effectors from Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras expressed more than sixfold less PD-1 compared with those in Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 2 G). We also observed a more than fourfold increase in IFN-γ production by OT-I cells from tumor-draining lymph nodes in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 2 H). These results suggest that tumor-resident effector and memory CD8+ T cell responses are enhanced in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras.

Exhausted T cells and formation of tissue-resident memory (TRM) cells in lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus clone 13 (LCMV CL13) infections are well characterized and are proposed to be similar to the antitumor T cell response (Wherry and Kurachi, 2015; Amsen et al., 2018). While capable of infecting DCs, LCMV CL13 is noncytopathic and suppresses DC immune functions (Ng et al., 2011). After infecting the chimeras with LCMV CL13, we saw less lung tissue damage and infiltrated lymphocytes in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 2 I). Accordingly, we observed an approximately threefold lower viral titer in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras measured by LCMV-mRNA–specific qPCR in the kidney (Fig. 2 J). There were also more intraepithelial CD69+ CD103+ LCMV H2-Db GP33 tetramer+ CD8+ T cells in the Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 2 K). These results suggest that antiviral resident memory CD8+ T cell responses are enhanced in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras.

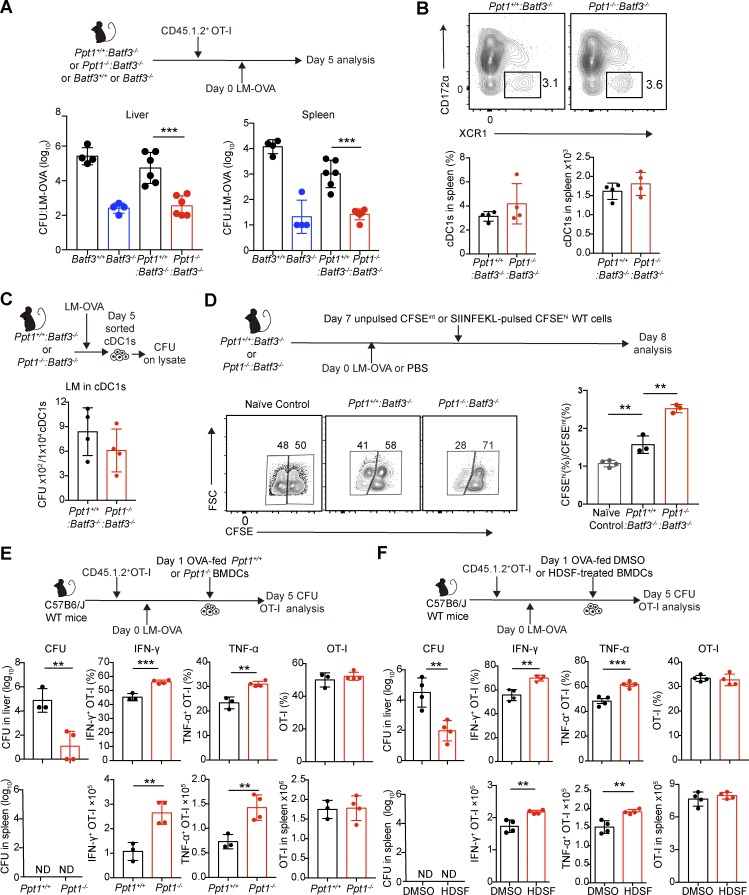

PPT1-deficient cDC1s convey host with resistance to LM

Intracellular bacteria LM do not kill DCs directly, but specifically use live cDC1s as an efficient vehicle to disseminate (Edelson et al., 2011). At the same time, LM clearance is heavily dependent on CD8+ T cells cross-primed by cDC1s (Jung et al., 2002; Alexandre et al., 2016). After infecting the chimeras with LM expressing recombinant OVA (LM-OVA), we observed a massive decrease in LM bacterial burden, as measured by CFUs, in the liver (>450-fold) and spleen (>40-fold) of Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 3 A). The bacterial load in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras was comparable to that of Batf3−/− mice, which are largely resistant to LM due to the lack of cDC1s (Fig. 3 A; Edelson et al., 2011). To eliminate the possibility that PPT1 might affect the survival of LM-infected cDC1s, we examined splenic cDC1s during LM-OVA infection in vivo. We observed no difference in cDC1 percentages or cell numbers between infected Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras at day 5 (Fig. 3 B). We also measured LM CFU from lysates of sorted Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1s from infected Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− and Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras. We found that PPT1-deficient cDC1s were infected at the same rate as PPT1-sufficient cDC1s (Fig. 3 C). Here we demonstrate that mice with PPT1 deficiency in cDC1s are resistant to LM infection.

Figure 3.

PPT1-deficient cDC1s convey host with resistance to LM. (A) Bacterial load (CFU) of liver (left) and spleen (right) are shown. Batf3+/+ or Batf3−/− mice or Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were injected with CD45.1.2+ OT-I T cells and the next day infected with LM-OVA. Mice were analyzed at day 5. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (Batf3+/+, n = 4 mice; Batf3−/−, n = 4 mice; Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/−, n = 6 mice). (B) Survival of splenic cDC1s. Representative FACS plot (left, gated on live MHCII+ CD11c+ CD172α− XCR1+), percentages (center), and cell numbers (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (C) Bacterial burden in cDC1s. cDC1s (gated on live MHCII+ CD11c+ CD172α− XCR1+ cells) from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were FACS sorted at day 5, and their lysates were used for CFU plating. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (D) Cytotoxicity of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in vivo. LM-OVA–infected chimeras were injected with SIINFEKL-pulsed/CFSE-labeled WT cells. Representative FACS plot (left) and CFSEhi/CFSEint ratio (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (E and F) Bacterial load (CFU) and cytokine production by OT-I cells in WT mice receiving BMDCs. LM-OVA–infected WT mice received either Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras (E) or DMSO or HDSF-treated WT BMDCs (F). Liver and spleen samples were plated for CFU, and splenic OT-I cells (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ CD45.1.2+ cells) were stimulated with SIINFEKL and analyzed by intracellular staining. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated by two-way Student’s t test (**, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001). FSC, forward scatter.

Next, we assessed whether the LM resistance in PPT1-deficient chimeras was dependent on CD8+ T cells primed by DCs. To determine whether CD8+ T cells primed by PPT1-deficient cDC1s were more cytotoxic, we used an in vivo killing assay using high expression of carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSEhi; empty control) or CFSEint (loaded with SIINFEKL) WT splenocytes (Iborra et al., 2012). We found that more SIINFEKL-pulsed target cells were lysed by effector CD8+ T cells from Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 3 D). To exclude the possibility that NK1.1+ cells played a role in the killing assay, we found that NK1.1+ DX5+ cell numbers appeared to be normal and that they produced similar amounts of IFN-γ in infected chimeras (Fig. S4, A and B). The production of IL-12p40 also remained unchanged in the serum of LM-OVA infected Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. S4 C). Next, we adoptively transferred equal numbers of Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras into LM-OVA-infected WT mice, and we observed a >1,000-fold lower bacterial load in liver of WT mice that received Ppt1−/− BMDCs than mice with Ppt1+/+ BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 3 E). IFN-γ and TNF-α production by OT-I cells were also increased by >2-fold in mice that received Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 3 E). Hexadecylsulfonylfluoride (HDSF) is a small molecule inhibitor of PPT1 enzymatic activity (Das et al., 2000). Since direct injection of HDSF into mice is lethal, we used an adoptive transfer system in which BMDCs were treated with HDSF ex vivo (Fig. S4 D). Similarly, we found >300-fold reduction of liver bacterial burden in the infected WT mice that received HDSF-treated BMDCs, compared with the mice that received DMSO-treated BMDCs (Fig. 3 F). IFN-γ and TNF-α production by OT-I cells were also increased in mice that received HDSF-treated BMDCs (Fig. 3 F). Thus, we conclude that the rapid clearance of LM in PPT1-deficient mice is due to enhanced CD8+ T cell priming by PPT1-deficent DCs.

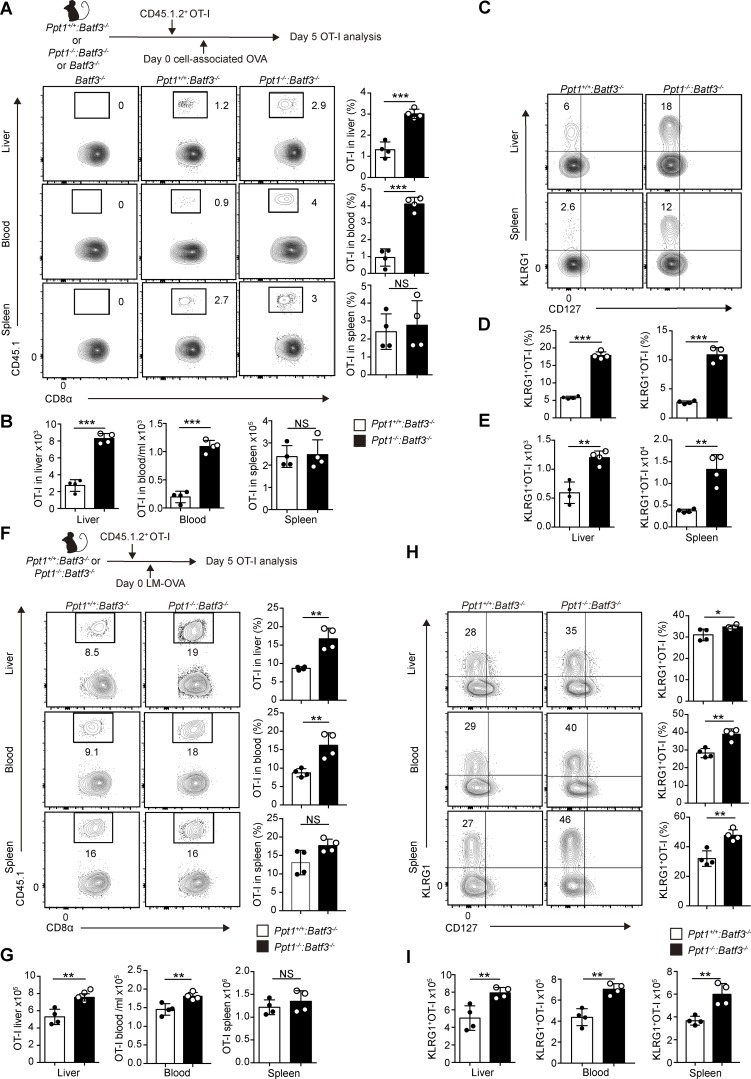

PPT1-deficient cDC1s preferentially crossprime naive CD8+ T cells into KLRG1+ effectors at nonlymphoid tissue

Having observed enhanced crosspriming by PPT1-deficient cDC1s to tumors and LM, we sought to directly test the crosspriming abilities of cDC1s in vivo. Hence, we intravenously injected CFSE-labeled OT-I cells and cell-associated OVA into Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras (Moore et al., 1988; den Haan et al., 2000). We observed more than threefold more OT-I cells (in both percentages and cell numbers) in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras in the liver and blood (Fig. 4, A and B). In comparison, there was no difference in splenic OT-I cell percentages or numbers (Fig. 4, A and B). We further examined the distribution of the KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effector subset, since they are more cytotoxic and tend to localize in nonlymphoid tissue (Joshi et al., 2007). We found that KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effector CD8+ T cells formed more readily in the liver and spleen (more than fourfold based on percentages, more than threefold based on cell numbers) of Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 4, C–E).

Figure 4.

PPT1-deficient cDC1s preferentially crossprime naive CD8+ T cells into KLRG1+ effectors at nonlymphoid tissue. (A and B) Tissue distribution of crossprimed OT-I cells. CD8+ T cells (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+) were analyzed from indicated organs from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras. Representative FACS plots (A, left) of liver (top), blood (center), and spleen (bottom); percentages (A, right); and cell numbers (B) are shown. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (C–E) Distribution of crossprimed OT-I effector subsets. OT-I cells (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ CD45.1.2+ cells) were analyzed from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras in indicated organs. Representative FACS plot (C) of liver (top) and spleen (bottom), percentages (D), and cell numbers (E) are shown. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (F and G) Tissue distribution of OT-I cells during infection. Representative FACS plots (F, left) of liver (top), blood (center), and spleen (bottom); percentages (F, right); and cell numbers (G) are shown. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (H and I) Distribution of OT-I effector subsets during infection. OT-I (gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ CD45.1.2+ cells) effector subsets from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were analyzed in the indicated organs. Representative FACS plots (H, left) of liver (top), blood (center), and spleen (bottom); percentages (H, right); and cell numbers (I) are shown. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated by two-way Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

During LM infection, cross-presentation of phagocytosed infected apoptotic cells by cDC1s initiates the CD8+ T cell response (Jung et al., 2002). We observed a similar pattern of CD8+ T cell trafficking and subset formation in LM-OVA–infected Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras. A greater number of expanded OT-I cells was observed in the liver and blood, but not the spleen, in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 4, F and G). We also found more KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effector CD8+ T cells in liver, blood, and spleen (Fig. 4, H and I). At later time points, there was no difference in the total number of KLRG1− IL-7Rα+ or KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effector CD8+ T cells in blood in LM-OVA–infected chimeras (Fig. S5, A–C). We observed no difference in central memory or effector memory subsets in blood, liver, and spleen OT-I cells at day 7 (Fig. S5, D–F). Collectively, our data suggest that PPT1-deficient cDC1s preferentially cross-prime naive CD8+ T cells into KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effectors at nonlymphoid tissue.

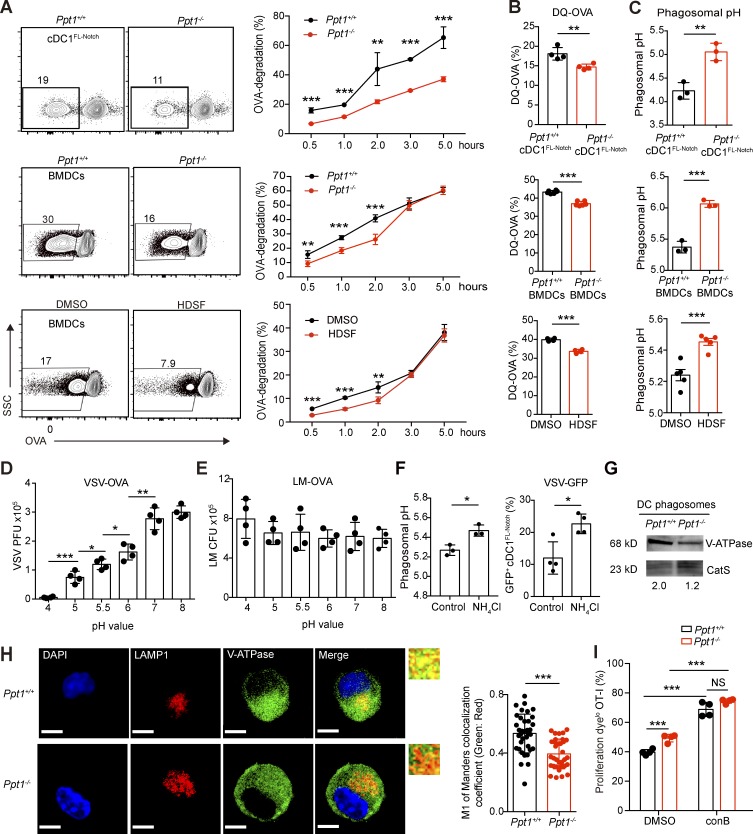

PPT1 promotes antigen degradation and phagosomal acidification in DCs

To explain the opposing phenotypes caused by PPT1 deficiency in cDC1s, we examined the role of PPT1 in the antigen presentation pathway of DCs. To determine whether PPT1 regulates antigen degradation in DCs, we performed a phagosomal protein degradation assay with OVA-associated beads using Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs from chimeras. We found approximately twofold less degraded OVA protein in phagosomes of Ppt1−/− than Ppt1+/+ cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs from chimeras during the time course (Fig. 5 A). Additionally, we fed DQ-OVA, which produces fluorescence upon hydrolysis by proteases, to the Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs from chimeras, and we detected reduced DQ signals in Ppt1−/− than Ppt1+/+ cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 5 B). Then, we treated WT BMDCs with DMSO or HDSF and measured antigen degradation using OVA-associated beads or DQ-OVA. Consistently, we found that HDSF-treated WT BMDCs degraded approximately twofold less OVA and released less DQ fluorescence than DMSO-treated BMDCs (Fig. 5, A and B). Therefore, we conclude that PPT1 promotes antigen degradation in DCs.

Figure 5.

PPT1 promotes antigen degradation and phagosomal acidification in DCs. (A) Antigen degradation in DC phagosomes. DCs were fed OVA-associated beads for indicated times. After lysis, the supernatants containing the latex beads were collected and stained with anti-OVA antibodies. Representative FACS plots at 1 h (left) of cDC1FL-Notch (top), BMDCs (center), DMSO- or HDSF-treated BMDCs (bottom), and time course (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 5 mice per group). (B) DQ-OVA release in DC phagosomes. BMDCs were fed DQ-OVA for 1 h. MFI of DQ-OVA in Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch (top), BMDCs (center), and DMSO- or HDSF-treated BMDCs (bottom) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (cDC1FL-Notch, n = 4 mice; BMDCs, n = 6 mice; DMSO or HDSF, n = 4 mice). (C) DC phagosomal pH. DCs were fed AF488 OVA and pHrodo-OVA for 1 h, and the pH value was calculated according to a pH standard curve based on flow cytometry data. cDC1FL-Notch (top), BMDCs (center), and DMSO- or HDSF-treated BMDCs (bottom) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (cDC1FL-Notch, n = 4 mice; BMDCs, n = 6 mice; DMSO or HDSF, n = 4 mice). (D and E) Effect of acidic pH on pathogen’s infectivity. VSV-OVA (D) or LM-OVA (E) were treated with the indicated pH buffers for 30 min, quenched at pH 7.4, and then evaluated for PFU or CFU. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 technical replicates). (F) Effect of endosomal alkalization on VSV infection rate of cDC1s. NH4Cl was used to increase endosomal pH on WT cDC1FL-Notch (left), and VSV-GFP+ cells with ddH2O (control) or NH4Cl treatment are shown (right). Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 technical replicates). (G) V-ATPase V1a protein expression in purified DC phagosomes. V-ATPase level was measured by Western blotting from purified BMDC phagosomes. CatS is used as loading control. Gray area ratio of vATPase over CatS is shown below. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (sample from three pooled mice). (H) V-ATPase V1a distribution on LAMP1+ endosomes. Confocal microscopy was performed using Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras with the indicated antibodies, and representative images (I) and the colocalization coefficient of LAMP1 and V-ATPase (right) are shown. Bars, 5 µm (all panels). Data are representative of one of six independent experiments (n = 35 cell images counted randomly per group). (I) Inhibition of crosspriming by V-ATPase inhibitor conB. DMSO or ConB was added along with OVA-associated beads to Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs. The percentages of Cell Proliferation Dyelo CD44+ OT-I cells are shown. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated by two-way Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Since antigen uptake differentially impacts antigen presentation by DCs, we already determined that PPT1 does not affect the phagocytosis ability of DCs (Fig. S3; Kamphorst et al., 2010). Then, we examined whether the slower antigen degradation in PPT1-deficent DCs is due to a more acidic endosomal pH. We measured the phagosomal pH of Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs from chimeras with pH-sensitive fluorescent pHrodo-OVA beads along with pH-insensitive AF488 beads. We found that the phagosomal pH was approximately 1 log higher in Ppt1−/− than Ppt1+/+ cDC1FL-Notch and BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 5 C). We also found that HDSF-treated WT BMDCs had almost half a log higher phagosomal pH than DMSO-treated BMDCs (Fig. 5 C). These results suggest that PPT1 promotes phagosomal acidification in DCs.

Phagocytes use acidic phagosomes to deactivate and degrade engulfed infectious agents (Watts, 1997). To assess whether VSV loses infectivity under acidic treatment, we treated VSV-OVA virions with different acidic pH conditions for as little as 30 min and found that VSV-OVA lost infectivity as the pH decreased (Fig. 5 D). In contrast to VSV, treatment of LM-OVA with different acidic pH conditions did not affect its infectivity (Fig. 5 E). We triggered endosomal alkalization in WT cDC1FL-Notch with low concentrations of NH4Cl and found that this treatment is sufficient to trigger an increase in VSV-GFP infection (Fig. 5 F; Jancic et al., 2007). Our data suggest that PPT1-mediated acidic phagosomes protect DCs from VSV infection.

The classic pH regulator V-ATPase, which consumes ATP to pump protons from the cytosol, had been shown to be crucial for maintaining the DC phagosomal pH (Cebrian et al., 2011). To further dissect the relationship between V-ATPase and PPT1, we purified DC phagosomes and found PPT1-deficient DC phagosomes had lower levels of V-ATPase subunit V1a (Fig. 5 G). We also used confocal microscopy to observe the localization of V-ATPase subunit V1a in Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras, and we found that V-ATPase colocalized less with LAMP1+ vesicles in Ppt1−/− DCs than in Ppt1+/+ DCs (Fig. 5 H). We then performed an in vitro cross-presentation assay with OVA-associated beads, along with Concanamycin B (conB), an inhibitor of V-ATPase (Jancic et al., 2007). The difference in OT-I proliferation between Ppt1+/+ and Ppt1−/− BMDCs disappeared after conB treatment (Fig. 5 I). Thus, we demonstrate that PPT1 lowers endosomal pH by recruiting V-ATPase to DC phagosomes.

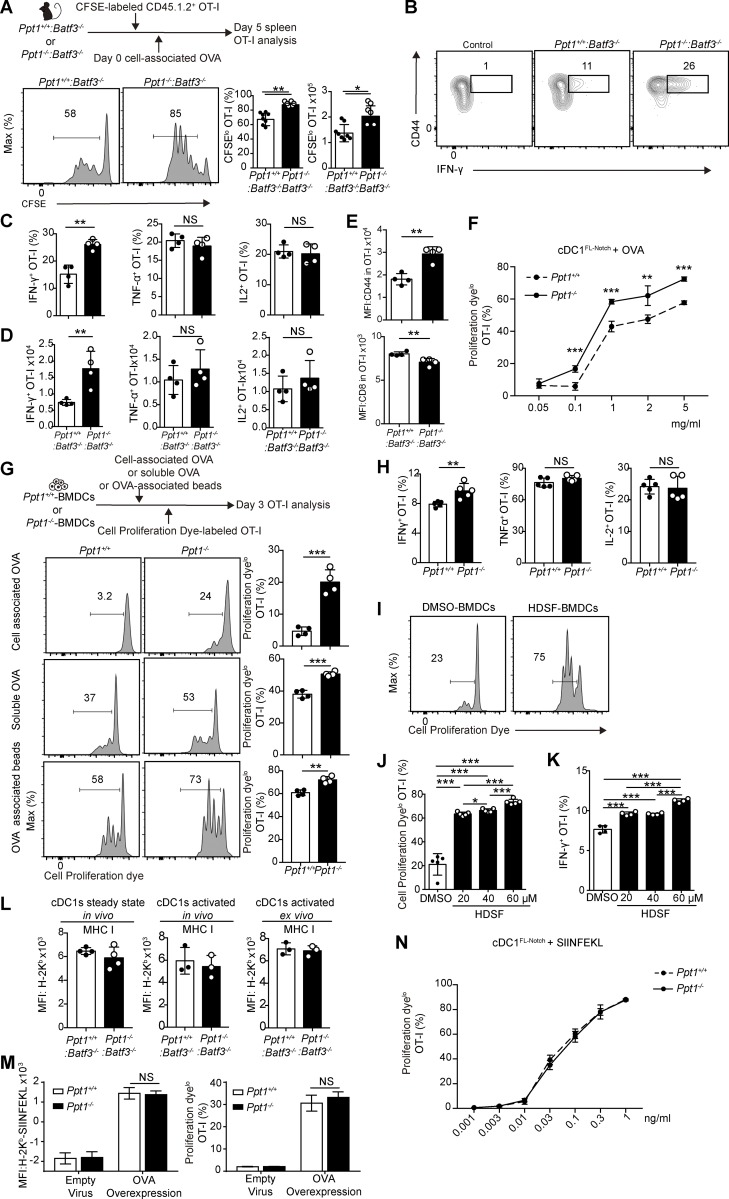

PPT1 suppresses antigen cross-presentation in vivo and in vitro

Higher cross-presentation capacity is associated with slower antigen degradation and higher phagosomal pH (Accapezzato et al., 2005; Delamarre et al., 2005). When we performed the in vivo cross-presentation assay with cell-associated OVA, we found that splenic OT-I cells from Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras expanded much faster compared with those from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 6 A). We also observed approximately twofold increased production of IFN-γ by splenic OT-I CD8+ T cells in terms of percentages and cell numbers in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras compared with Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 6, B–D). In contrast, TNF-α and IL-2 production by OT-I cells remained unchanged (Fig. 6, C and D). We noticed a greater activation of the crossprimed CD8+ T cells, as CD44 was up-regulated and CD8α was down-regulated in OT-I cells from Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras that those from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras (Fig. 6 E). Our data suggest that PPT1 in cDC1s suppresses the proliferation and IFN-γ production of crossprimed CD8+ T cells in vivo.

Figure 6.

PPT1 suppresses antigen cross-presentation in vivo and in vitro. (A) Splenic OT-I proliferation measured by CFSE. Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were injected with CFSE-labeled CD45.1.2+ OT-I T cells and then injected with cell-associated OVA the next day. Mice were analyzed 5 d later. Representative FACS plot (left, gated on live CD8α+ CD44+ CD45.1.2+), CFSElo percentages (center), and cell numbers (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (B–D) Cytokine production of splenic OT-I cells. Representative FACS plots (B, gated on live CD8α+ CD45.1.2+ cells) are shown. Percentages (C, IFN-γ, left; TNF-α, center; and IL-2, right) and cell numbers (D) are shown. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (E) Expression of activation markers on splenic OT-I cells. MFI of CD44 (top) and CD8α (bottom) are shown. Data are representative of one of five independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (F) Crosspriming by cDC1FL-Notch. Ppt1+/+, or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch from chimeras were fed with indicated OVA concentrations, and OT-I proliferation was measured by Proliferation dye. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (G) Crosspriming by BMDCs. Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras were fed the indicated exogenous antigens. Representative FACS plot (left, gated on live CD8α+ CD45.1+) of Tap1−/− cell–associated OVA (top), soluble OVA (center), or OVA-associated beads (bottom). Percentages of Cell Proliferation Dyelo CD44+ OT-I cells (right) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (H) Cytokine production of crossprimed OT-I cells. Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras were fed with Tap1−/− cell–associated OVA. Percentages of cytokine-producing OT-I cells (IFN-γ, left; TNF-α, center; and IL-2, right) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (I and J) OT-I proliferation measured by Cell Proliferation Dye. DMSO or HSDF-treated WT BMDCs were fed with Tap1−/− cell–associated OVA. Representative FACS plot (I) and Cell Proliferation Dyelo OT-I cell percentages (J) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). (K) IFN-γ production by OT-I cells. DMSO- or HSDF-treated WT BMDCs were fed with Tap1−/− cell–associated OVA, and OT-I cells were stimulated with SIINFEKL. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 5 mice per group). (L) MHC class I expression on cDC1s. H2-Kb expression was measured by FACS on naive splenic cDC1s (left), during LM-OVA infection (center), and LPS-activated (right) cDC1s from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice). (M) Effect of PPT1 on endogenous MHC class I presentation. WT BMDCs were transduced with empty or OVA-expressing retroviruses and then incubated with OT-I cells. MFI of H-2Kb-SIINFEKL (25.D1.16, left) and OT-I proliferation (right) are shown (n = 3 technical replicates). Data are representative of one of two independent experiments. (N) Direct MHC I antigen presentation by cDC1FL-Notch. Ppt1+/+, or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch from chimeras were pulsed with indicated concentrations of SIINFEKL and then incubated with CFSE-labeled CD45.1.2+ OT-I cells. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated by two-way Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

Next, we performed in vitro cross-presentation assays with exogenous antigens and measured the proliferation of OT-I cells by Cell Proliferation Dye. Consistent with our in vivo data, we found that PPT1-deficient cDC1FL-Notch crossprimed more OT-I cells when pulsed with various concentrations of OVA (Fig. 6 F). Similar to cDC1FL-Notch, we observed increased OT-I proliferation by cell-associated OVA, soluble OVA, and OVA-associated beads in Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 6 G). OT-I cells crossprimed by Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras produced higher levels of IFN-γ than Ppt1+/+ BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 6 H). We also found that treating WT BMDCs in vitro with HDSF greatly enhanced the crosspriming ability of BMDCs, with more rapid proliferation and increased IFN-γ production in OT-I cells (Fig. 6, I–K). Here we find that PPT1 in DCs suppresses proliferation and IFN-γ production of crossprimed CD8+ T cells in vitro.

To determine if PPT1 regulates the endogenous MHC I presentation pathway, we measured and observed no difference in MHC class I (H2-Kb) expression between Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1s in steady state, after in vivo LM-OVA infection or ex vivo LPS activation (Fig. 6 L). Furthermore, we transduced Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras with an OVA-overexpressing retrovirus, and detected no difference in endogenous presented MHC class I antigen (measured by anti-H-2Kb-SIINFEKL complex antibody 25.D1.16) and OT-I proliferation (Fig. 6 M). Lastly, to exclude the possibility that if PPT1-deficient DCs could prime CD8+ T cells independently of cross-presented antigens, we pulsed Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1FL-Notch with various concentration of SIINFEKL and found that there was no difference in OT-I proliferation (Fig. 6 N). Here we conclude that PPT1 is dispensable for the endogenous MHC I presentation pathway in DCs.

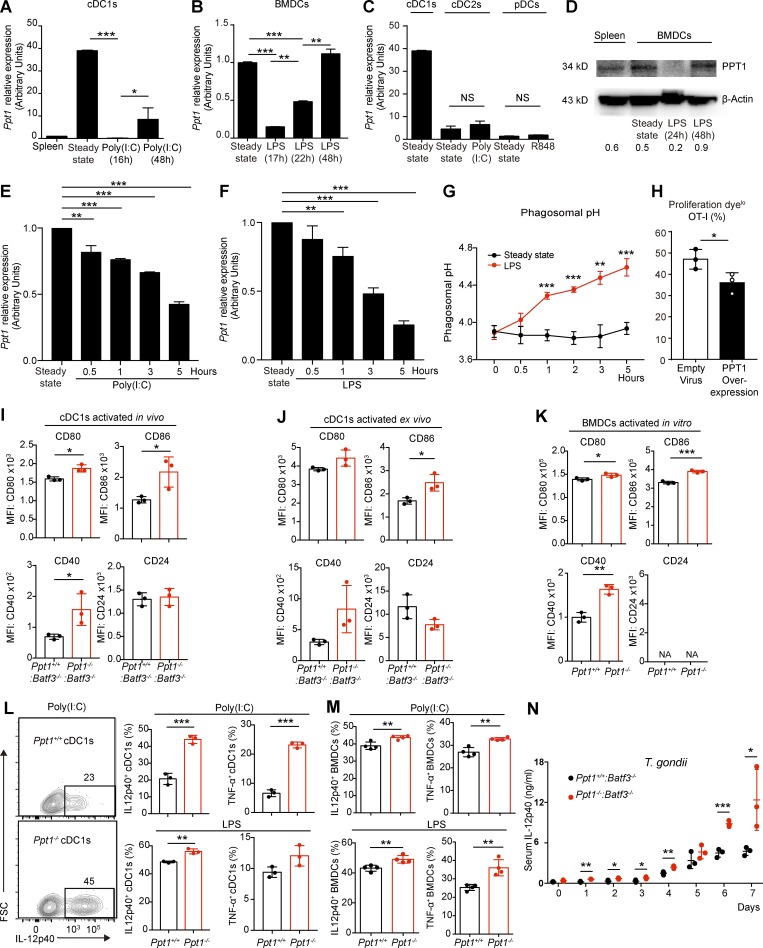

Rapid down-regulation of PPT1 in activated cDC1s facilitates efficient crosspriming

DC cross-presentation capacity is usually increased after activation by TLRs Alloatti et al., 2015). To elucidate the regulation of PPT1 during DC activation, we examined the expression of Ppt1 mRNA transcripts in activated DCs by qPCR. We observed that Ppt1 mRNA was significantly down-regulated in polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly(I:C))–treated cDC1s (>100-fold) and LPS-treated BMDCs (>20-fold) following in vitro stimulation for 16 h (Fig. 7, A and B). When we reanalyzed a previously published RNA-seq that profiled immune cells during murine cytomegalovirus infection in vivo, we also found that PPT1 mRNA was down-regulated in cDC1s (Fig. S1 C; Manh et al., 2013). After this acute down-regulation, we then observed an up-regulation of Ppt1 mRNA in cDC1s and BMDCs 48 h after stimulation (Fig. 7, A and B). In contrast, cDC2s and pDCs had relatively low transcript amounts of Ppt1 before and after activation (Fig. 7 C). Next, we confirmed the PPT1 protein expression pattern in LPS-activated BMDCs by Western blotting (Fig. 7 D). Here, we find that PPT1 expression is quite dynamic in cross-presenting DCs: high expression at steady state, low expression after TLR activation, and recovery at a later time point.

Figure 7.

Rapid down-regulation of PPT1 in activated cDC1s facilitates efficient crosspriming. (A) Ppt1 mRNA expression in activated cDC1s. FACS sorted WT cDC1s were stimulated with poly(I:C), and Ppt1 transcript was measured by qPCR. Data are combined results of three independent experiments (n = relative values from three independent runs). (B) Ppt1 mRNA expression in activated BMDCs. WT BMDCs were stimulated with LPS, and Ppt1 transcript was measured by qPCR. Data are combined results of three independent experiments (n = relative values from three independent runs). (C) Ppt1 mRNA expression in other activated DCs. Indicated FACS-sorted WT populations were stimulated, and Ppt1 transcript was measured by qPCR. Data are combined results of three independent experiments (n = relative values from three independent runs). (D) PPT1 protein expression in activated BMDCs. WT BMDCs were stimulated with LPS, and PPT1 expression was measured by Western blotting. β-Actin was used as loading control. Gray area ratio of PPT1 over β-actin is shown below. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (sample from three pooled mice). (E and F) PPT1 down-regulation after DC activation. WT BMDCs were stimulated with poly(I:C) (E) or LPS (F), and Ppt1 transcript was measured at indicated time points by qPCR. Data are combined results of three independent experiments (n = relative values from three independent runs). (G) Phagosomal alkalization after DC activation. WT BMDCs were stimulated with LPS, and then fed with AF488-OVA and pHrodo-OVA. Phagosomal pH was then calculated at indicated time points accordingly. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (H) Crosspriming by DCs with PPT1 overexpression. WT BMDCs were transduced with empty or PPT1-overexpressing retroviruses, then fed with OVA and OT-I cells. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 technical replicates). (I) Costimulatory signals by activated cDC1s in vivo. Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were infected with LM-OVA, and then splenic cDC1s (gated on live CD11chi MHC II+ XCR1+ CD172α−) were analyzed at day 5. MFI of CD80, CD86, CD40, and CD24 are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (J) Costimulatory signals by activated cDC1s ex vivo. Splenic cDC1s (gated on live CD11chi MHC II+ XCR1+ CD172α−) were sorted from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras and then activated in vitro with LPS for 18 h. MFI of CD80, CD86, CD40, and CD24 are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (K) Costimulatory signals by activated BMDCs in vitro. Surface molecule expression was analyzed on Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras activated with LPS for 18 h. MFI of CD80, CD86, CD40, and CD24 are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (L) Cytokine production by activated cDC1s. FACS-sorted cDC1s from Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were activated with poly(I:C) or LPS for 18 h, then analyzed by FACS intracellular staining. Representative FACS plot of poly(I:C)-stimulated cDC1s (IL-12p40, left), percentages of IL-12p40, and TNF-α production with poly(I:C; right, top) or LPS (right, bottom) are shown. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (M) Cytokine production by activated BMDCs. Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras were activated with poly(I:C) or LPS for 18 h, then analyzed by intracellular IL-12p40 and TNF-α FACS staining. Data are representative of one of three independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). (N) Serum IL-12p40 level during T. gondii infection. Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras were infected with T. gondii, and serum IL-12p40 was measured by ELISA on indicated days. Data are representative of one of two independent experiments (n = 3 mice per group). All data are shown as mean ± SD, and P values were calculated by two-way Student’s t test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001).

To dissect the kinetic relationship between PPT1 down-regulation and efficient cross-presentation, we further examined the expression of PPT1 mRNA by qPCR at 0.5, 1, 3, and 5 h after activation by poly(I:C) or LPS in WT BMDCs, and we found a gradual decrease of PPT1 mRNA expression starting 0.5∼1 h after activation (Fig. 7, E and F). We also found a corresponding increase in phagosomal pH in WT BMDCs 0.5∼1 h after LPS activation (Fig. 7 G). Thus, we found that PPT1 down-regulation and endosomal acidification happen concurrently, as early as 0.5∼1 h after activation. Furthermore, we fed OVA to BMDCs transduced with PPT1-overexpressing retroviruses, then found that CD8+ T cell crosspriming is decreased compared with BMDCs transduced with empty viruses (Fig. 7 H). Our results show that down-regulation of PPT1 may be responsible for enhanced cross-presentation in activated DCs.

Since the stimulatory signals provided by DCs influence effector and memory T cell differentiation, we hypothesized that the artificial deletion of PPT1 might control T cell priming signals (Kaech and Cui, 2012). We detected increased expression of CD86, CD80, and CD40 in PPT1-deficient cDC1s from in vivo LM-OVA infection (Fig. 7 I). PPT1-deficient cDC1s activated by LPS ex vivo produced increased expression of CD86 compared with PPT1-sufficient cDC1s (Fig. 7 J). Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras activated by LPS in vitro expressed increased levels of CD80, CD86, and CD40 compared with Ppt1+/+ BMDCs (Fig. 7 K). However, we did not observe any difference in CD24 expression in Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− cDC1s during in vivo LM-OVA infection or ex vivo LPS activation (Fig. 7, J and K). Our data suggest that deletion of PPT1 in activated DCs facilitates expression of costimulatory molecules.

The production of cytokines, such as IL-12, has been proposed to facilitate cDC1 crosspriming of naive cells into memory T cell subsets (Mashayekhi et al., 2011; Sosinowski et al., 2013; Kim et al., 2014). Accordingly, we found that activated Ppt1−/− cDC1s produced more IL-12p40 and TNF-α than Ppt1+/+ cDC1s upon poly(I:C) or LPS activation (Fig. 7 L). We also found increased production of IL-12p40 and TNF-α by Ppt1−/− BMDCs from chimeras (Fig. 7 M). Since cDC1-derived IL-12 is crucial for host protection against Toxoplasma gondii, we infected the chimeras with T. gondii and measured the amount of IL-12p40 in the serum by ELISA (Mashayekhi et al., 2011). We observed a consistently higher serum level of IL-12p40 in Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras than in Ppt1+/+:Batf3−/− chimeras throughout the time course (Fig. 7 N). Here we conclude that the deletion of PPT1 in activated DCs leads to increased production of inflammatory cytokines. Collectively, our results suggest that the down-regulation of PPT1 in activated DCs is likely to facilitate naive T cell priming by increased cross-presentation and production of costimulatory and inflammatory cytokines.

Discussion

We demonstrated that PPT1 deficiency in cDC1s is detrimental to the host in cytopathic viral infections but beneficial when encountering tumors and intracellular bacteria. We hypothesize that high levels of PPT1 in steady-state cDC1s maintain protective acidic phagosomes to deactivate viruses, whereas low levels of PPT1 in activated cDC1s are likely to facilitate T cell crosspriming with increased stimulatory signals. Despite PPT1 being down-regulated after activation, we still observed that complete loss of PPT1 in activated cDC1s increases the expression of costimulatory B7 molecules and inflammatory cytokines such as IL-12. Thus, PPT1-deficient cDC1s lacked this “on–off switch” and remained in a constant state of enhanced cross-presentation.

Our data suggest that PPT1 in DCs promotes phagosome acidification for increased viral resistance. First, we showed that PPT1-deficient DCs had more alkaline phagosomes. This could be due to reduced recruitment of V-ATPases, which directly lowers pH by pumping in protons. Our results are consistent with a recent study showing that PPT1 regulates lysosomal pH and V-ATPase recruitment in neurons (Bagh et al., 2017). Second, we demonstrated that VSV infectivity was lowered by a brief duration of mild acidic treatment. Similarly, preexposure of herpes simplex virus to mildly acidic pH inactivates viral infectivity in an irreversible manner (Weed et al., 2017). Correspondingly, we found that endosomal alkalization in DCs also increased their VSV infection rate. Third, we found that PPT1-deficient DCs were more easily infected by VSV in vitro and in vivo, and PPT1-deficient DCs released more virions into the surroundings. Thus, the impaired response to VSV by PPT1-deficient cDC1s may be due to a failure to deactivate phagocytosed virions in DC phagosomes. Of note, the weakened anti-VSV T cell response in PPT1-deficient mice might be partially rescued by increased crosspriming by PPT1-deficient cDC1s. In comparison, LCMV CL13 is noncytopathic, and increased LCMV infection of PPT1-deficient DCs may not affect cDC1 survival as much as VSV. The negative impact of increased LCMV infection may then be easily countered by the enhanced cDC1 priming of tissue-resident T cells. To confirm that the viral resistance conferred by PPT1 is mediated by acidic phagosomes, more cytopathic and noncytopathic viruses should be examined.

The upstream regulation of PPT1 in DCs remains to be fully elucidated. Many groups have observed that DCs could switch to different “modes” of cross-presentation capability (Joffre et al., 2012). DCs usually enhance cross-presentation upon activation by TLRs or cytokines such as IFN-I, but then decrease it after returning to the steady state (Fuertes et al., 2011; Mantegazza et al., 2014; Alloatti et al., 2015; Samie and Cresswell, 2015). Since we found that PPT1 inhibits cross-presentation, DCs are likely to down-regulate PPT1 quickly after TLR ligation to facilitate efficient cross-presentation. Thus, further experiments are needed to dissect the regulation of PPT1 by TLR and cytokine signaling pathways. Additionally, the transcription factors TFEB and WDFY4 also act as key antigen cross-presentation switches in DCs (Samie and Cresswell, 2015; Theisen et al., 2018). Further studies are needed to determine whether TFEB or WDFY4 controls PPT1 transcription.

Although PPT1 is known to depalmitoylate lysosomal proteins, its direct substrates or target proteins in DCs are completely unknown. First, since we found that PPT1 suppresses antigen retention and cross-presentation, the downstream targets of PPT1’s enzymatic activity could be key proteins involved in antigen cross-presentation. Many Rab GTPase proteins, such as Rab27a, Rab32, Rab34, and Rab43, are involved in antigen presentation (Jancic et al., 2007; Alloatti et al., 2015; Kretzer et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016). Hence, we speculate that PPT1 might directly depalmitoylate Rab GTPases to regulate antigen presentation in DCs. In addition, phagosomal proteins directly regulating endosomal pH, such as V-ATPase or NOX2, could also be direct targets of PPT1. In neurons, V-ATPase has been shown to require palmitoylation for interaction with adaptor protein-2 and -3, respectively, for trafficking to the lysosomal membrane (Bagh et al., 2017). Second, since we found that PPT1 controls DC viral resistance, PPT1 might directly depalmitoylate viral antigens and thus suppress viral propagation. Many viral envelope proteins, including those of VSV and the influenza virus, require palmitoylation for entry, budding, and assembly (Veit, 2012). However, depalmitoylation of viral proteins could still be achieved by cytosolic acyl protein thioesterase 1, which exerts exactly the same enzymatic function as PPT1 (Salaun et al., 2010). Quantitative proteomics or specific biochemical studies, such as S-acylated proteins resin-assisted capture assay, should be conducted to confirm the possible palmitate acetylation sites in key proteins involved in cross-presentation and viral infection (Forrester et al., 2011).

Upon priming by DCs, naive CD8+ T cells differentiate into short-lived effector and long-lived memory subsets (Kaech and Cui, 2012). In peripheral tissue, TRM (CD69+ CD103+) cells constitute a phenotypically separate lineage that is crucial for barrier immunity as well as the antitumor response (Sheridan and Lefrançois, 2011; Mackay et al., 2013; Milner et al., 2017; Amsen et al., 2018). KLRG1, along with IL-7Rα (CD127), have been used extensively as markers to identify effector CD8+ T cells with differential effector functions, migratory properties, long-term survival and multilineage memory potential (Joshi et al., 2007). Although KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− cells are thought to possess lower memory potential than KLRG1+ IL-7Rα+ or KLRG1− IL-7Rα+ cells, these memory precursor subsets possess considerable heterogeneity and plasticity (Kaech and Wherry, 2007). A recent study indicated that KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− cells are able to differentiate into all memory subsets (including TRM) and are highly effective in mounting antiviral and antitumor responses (Herndler-Brandstetter et al., 2018). Accordingly, we found that PPT1-deficient cDC1s produced more IL-12, primed more KLRG1+ effectors in nonlymphoid tissue, and formed more tissue-resident effector and memory cells. Thus, the enhanced T cell response in PPT1-deficient mice could be due to a combination of more cytotoxic KLRG1+ effectors in nonlymphoid tissue and their subsequent conversion into TRM cells. Our study supports the theory that the KLRG1+ IL-7Rα− effector subset could differentiate into TRM cells.

cDC1s had been shown to crossprime naive CD8+ T cells into differential memory subsets during secondary infections with LM and several viruses (Alexandre et al., 2016). Recent studies showed that cDC1s were required in the optimal priming of naive CD8+ T cells into CD8+ TRM cell subsets during vaccinia virus and influenza infections (Iborra et al., 2012, 2016). Although several stimulatory signals such as IL-12 had been implicated in the cross-priming of TRM cells, cDC1-specific factors that regulate this process remain poorly understood (Iborra et al., 2016). Here we demonstrated that PPT1 directs the crosspriming of naive CD8+ T cells into tissue-resident effectors and memory T cells in tumors, bacterial infections, and chronic viral infections. Our results further support and clarify the molecular mechanism that enables cDC1 to crossprime naive CD8+ T cells into CD8+ TRM cell subsets.

Our study joins a growing number of publications suggesting that the immune system may play a direct role in LSDs (Boustany, 2013). Certain LSD-associated mutations, such as lysosomal cysteine cathepsins, have been associated with macrophage dysfunction in response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Berg et al., 2016). Our results suggest that there could be CD8+ T cell–mediated pathologies in PPT1-deficient mice or infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis patients. On the other hand, targeting PPT1 could be a promising therapy to treat intracellular microbial infections such as M. tuberculosis, as well as cancer. Recently, a drug screen of lysosomal inhibitors identified PPT1 as an effective anticancer therapeutic target (Rebecca et al., 2017). Our results imply that the antitumor effect of PPT1 inhibitors could be attributed largely to PPT1’s role in cDC1s. In addition, small-molecule PPT1 inhibitors are capable of breaching the blood–brain barrier and, therefore, may cause considerable damage to the central nervous system. Both neurological and immunological systems should be evaluated for any potential therapies targeting PPT1.

Finally, we obtained consistent results in cross-presenting cDC1s and BMDCs (both GM-CSF and FLT3L-derived) in vitro and in vivo, suggesting that PPT1 belongs to an antigen presentation pathway conserved in divergent cross-presenting DC types. Our results suggest that the dynamic expression of PPT1 in cross-presenting DCs serves dual functions of viral resistance and efficient CD8+ T cell crosspriming. The modulation of PPT1 by therapeutics represents a flexible tool to manipulate the immune response in diverse pathological conditions.

Materials and methods

Mice

C57BL/6J, BALB/cJ (BALB/c), B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1+), B6.129S2-Tap1tm1Arp/J (Tap1−/−), C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J (OT-I), B6.129S6-Ppt1tm1Hof/SopJ, (Ppt1−/−), and B6.129S(C)-Batf3tm1Kmm/J (Batf3−/−) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. B6.129S6-Ppt1tm1Hof/SopJ (Ppt1−/−) mice were backcrossed for ≥10 generations with C57BL/6J. Mice designated as WT or CD45.1+ were derived from in-house breeding of C57BL/6 or B6.SJL-PtprcaPepcb/BoyJ strains. Age- and sex-matched mice 6–12 wk of age were used. All mice were bred and maintained in specific pathogen–free conditions at GemPharmatech Co., Ltd., and BSL3 facilities at Sun Yat-sen University, according to the institutional guidelines and protocols approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China.

Generation of chimeras

For Ppt1−/− chimeras, CD45.1+ mice were lethally irradiated with 950 rad and then injected i.v. with 1 × 106 bone marrow cells harvested from Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− littermates. The mice were fed antibiotics for 2 wk and then rested for at least an additional 4 wk to allow reconstitution of immune cells. For Ppt1+/+:Ppt1−/− chimeras, CD45.1.2+ mice were lethally irradiated with 950 rad and then injected i.v. with 1 × 106 bone marrow cells harvested from age- and sex-matched WT CD45.1+ and CD45.2+Ppt1−/− mice at the ratio of 1:1. For Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/−:Batf3−/− chimeras, CD45.1+ mice were lethally irradiated with 950 rad and then injected i.v. with 1 × 106 bone marrow cells harvested from Ppt1+/+ or Ppt1−/− littermates, and 1×106 bone marrow cells were harvested from age- and sex-matched Batf3−/− mice. The mice were fed antibiotics for 2 wk and rested for at least an additional 4 wk to allow the reconstitution of immune cells.

Immune cell isolation

To harvest immune cells from lymphoid tissue, organs were minced, ground up, and passed through a 70-µm nylon mesh. Erythrocytes were removed using ammonium-chloride-potassium lysis buffer (150 mM ammonium chloride, 10 mM potassium bicarbonate, and 0.1 mM EDTA). The cells were counted using Beckman Coulter CytoFlex. Before sorting, DCs were enriched with CD11c microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). For peripheral tissues, organs were digested in collagenase D (Roche) and DNase I (Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C with stirring in PBS. Liver immune cells were separated using a Percoll gradient (Sigma-Aldrich). For isolation of intraepithelial lymphocytes, the small intestine was removed, Peyer’s patches were excised, and the intestine was cut longitudinally and then laterally into 0.5–1-cm2 pieces. Tissues were incubated with 0.154 mg/ml dithioerythritol in 10% HBSS/Hepes bicarbonate buffer for 30 min at 37°C, and then with 100 U/ml type I collagenase in RPMI 1640, 5% FBS, 2 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM CaCl2 for 30 min at 37°C with stirring at 250 rpm. After enzymatic treatment, tissues were further dissociated over a 70-µm nylon cell strainer. For isolation of lymphocytes, single-cell suspensions were separated using a 44/67% Percoll (Sigma-Aldrich) density gradient.

Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed on Beckman Coulter CytoFlex and analyzed using FlowJo software (TreeStar). Mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) was calculated by genomic mean in FlowJo. Cell-sorting experiments were conducted on a BD Aria II. Staining was performed at 4°C in the presence of Fc block (Clone 2.4G2; BD) and FACS buffer (PBS, 0.5% BSA, 2 mM EDTA, and 0.1% sodium azide). In the case of intracellular cytokine staining, brefeldin A (eBioscience) was added with peptide (10 nM SIINFEKL for OT-I cells) or TLR ligands (for BMDCs) for 4–8 h before staining with the intracellular staining kit (eBioscience). The following antibodies were all purchased from eBioscience unless otherwise indicated: anti-CD8α (53-6.7), IL-2 (JES6-5H4), CD69 (H1.2F3), TNF-α (MP6-XT22), CD45.1 (A20), CD44 (IM7), CD80 (16-10A1), IFN-α (RMMA-1), CD11C (N418), Clec9A (42D2), IFN-γ (XMG1.2), MHC II (M5-114.15.2), CD24 (M1-69), CD86 (GL1), PD-L1 (NIH5), CD127 (A7R34), XCR1 (ZET; BioLegend), CD103 (2E7), KLRG1 (2F1), IL-12p40 (C17.8), PD-1(J43), CD40 (IC40), SIINFEKL-peptide bound to H2-Kb (25.D1.16), LCMV gp33-H-2Db (gp33-41; MBL), and H-2Kb (AF6-88.5.5.3). MFI were calculated by genomic mean.

BMDCs

As previously described (Helft et al., 2015), in short, 10 × 106 bone marrow cells per well were cultured in tissue culture–treated 6-well plates in 4 ml of RP10 (RPMI 1640 supplemented with glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin, and 2-mercaptoethanol; all from Invitrogen), 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum(Source BioSciences), and GM-CSF (20 ng/ml; Peprotech). Half of the medium was removed at day 2, and new medium supplemented with GM-CSF (40 ng/ml) and warmed at 37°C was added. The culture medium was entirely discarded at day 3 and replaced with fresh warmed medium containing GM-CSF (20 ng/ml). For BMDC activation, 10 µg/ml poly(I:C) (HMW; Invitrogen) or 5 µg/ml LPS (Escherichia coli 026:B6; eBioscience) was used at the indicated time points. BMDCs were gated as live+ CD11b+ MHCII+ CD11c+ cells.

DCFL-Notch culture

As previously described (Kirkling et al., 2018), single-cell suspensions of primary murine BM cells were suspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS, 1% l-glutamine, 1% sodium pyruvate, 1% MEM with nonessential amino acids, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 55 µM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% supernatant from cultured B16-FLT3L cell line (DC medium). Cells were plated at 2 × 106 cells per well in 2 ml of DC medium in 24-well plates and cultured at 37°C in a humidified incubator at 5% CO2. On day 3 of differentiation, half of the volume of cells in DC medium from each well was transferred to a single well containing a monolayer of mitomycin-treated OP9-DL1 cells in 24-well plates. Cell cultures were analyzed on day 7. cDC1FL-Notch were gated as live+ DEC205+ CD24+ CD8α+ CD11b− MHCII+ CD11c+ cells.

Retroviral transduction of BMDCs

Phoenix packaging cells (#CRL-3214; ATCC) were transfected with 20 µg of the plasmid pCL-Eco (#25099; Addgene) and 16 µg of pMXs-PPT1, pMXs-OVA (cloned from Addgene #25099), or empty vector pMXs with 90 µl transfecting reagent polyethylenimine (23966-1; Polysciences) at 1 mg/ml in a 10-cm culture dish. After 48 h, the supernatant containing retrovirus was harvested and filtered. For BMDC retroviral transduction, on days 1 and 2, 2 ml retroviral supernatant was added, and cells were spin-infected (2,500 rpm) for 90 min at room temperature. On day 3, fresh medium was added to the cells, and they were cultured for two more days. All retroviral transduction rate was >70% as measured by GFP with FACS.

In vivo antigen cross-presentation assays with cell-associated OVA

As previously described (Moore et al., 1988), in short, BALB/c or Tap1−/− splenocytes were loaded with OVA by osmotic shock. Cells were incubated in hypertonic medium (0.5 M sucrose, 10% polyethylene glycol, and 10 mM Hepes in RPMI 1640, pH 7.2) containing 10 mg/ml OVA for 10 min at 37°C, and then prewarmed hypotonic medium (40% H2O and 60% RPMI 1640) was added for an additional 2 min at 37°C. After washing and irradiation (1,350 rad), OVA-loaded cells were injected into mice that had been injected i.v. 24 h earlier with CFSE-dyed OT-I cells.

In vitro antigen cross-presentation assays

As previously described (Alloatti et al., 2015), in short, BMDCs were pulsed overnight with OVA protein (5 mg/ml) or OVA conjugated to 3-µm latex beads (Polyscience): Tap1−/− cell-associated OVA (BMDC:cell-associated OVA = 1:5). The cells were cocultured with OVA-specific OT-I T cells stained with CFSE or cell proliferation dye for 10 min at 37°C at a 1:2 ratio in 24-well plates. After 3 d, OT-I T cell proliferation was analyzed by flow cytometry.

In vivo and in vitro infection models

In vivo

As previously described (Yang et al., 2011), in short, at day 0, 1 × 105 OT-I cells were injected i.v. into mice. For LM-OVA infection, LM-OVA was grown in Tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium to an OD600 of ∼0.25, diluted in PBS, and injected i.v. (8 × 103 CFU) in a volume of 0.2 ml per mouse. After 5 d, the mice were analyzed. Splenic cDC1s were FACS sorted and plated in TSB solid medium overnight at 37°C. For VSV-OVA infection, 1 × 106 PFU were diluted in PBS and injected i.v. For the VSV-PFU plaque-forming assay, Vero cells were plated in 6-well plates. Next, 100 µl of the samples were added to the Vero cell monolayers. After incubating the plates for 60–90 min in a humidified 37°C 5% CO2 incubator with occasional rocking every 20–30 min, the agarose overlay was prepared by combining equal volumes of 2× MEM and 1% agarose solution in water. To each monolayer, 3 ml agarose overlay was added. Plates were incubated for 2 d at 37°C with 5% CO2. They were then stained with 1 ml of a 1:10,000 dilution of neutral red (from a 1% aqueous solution) made up in 1:1 2× MEM and 1% agarose and incubated overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. For the LM-CFU colony-forming assay, 100-µl samples were added to TSB solid medium and incubated overnight at 37°C. For LCMV CL13 infection, 1 × 106 PFU were diluted in PBS and injected i.p. into mice. Lung peribronchial inflammation scoring was as previously described (Myou et al., 2003): 0, normal; 1, few cells; 2, a ring of inflammatory cells one cell layer deep; 3, a ring of inflammatory cells two to three cells deep; 4, a ring of inflammatory cells four cells deep. For parasitic infections, T. gondii (RH strain) tachyzoites were grown in human foreskin fibroblast culture. 200 freshly egressed tachyzoites were filtered, counted, and injected i.v. into mice.

In vitro

For VSV-GFP infection, BMDCs and cDC1FL-Notch were cultured as described above. Virus (multiplicity of infection: 16) only or with NH4Cl (3 mM; Sigma-Aldrich) was added into culture medium. After 24-h incubation, cells were analyzed. For VSV-GFP and VSV-OVA mixed infection, 293T cells were infected by VSV-GFP and VSV-OVA, harvested, washed three times in cold 1× PBS to remove cell lysate, and cocultured with cDC1FL-Notch for 24 h. Then GFP+ cDC1FL-Notch and GFP− cDC1FL-Notch were sorted and fixed with 0.008% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde for 10 min at 4°C and washed twice with 0.2 M glycine and once again with 1× PBS. Resuspended cells were then cocultured with OT-I separately. OT-I proliferation was analyzed on day 3. For the LM/VSV infectivity pH assay, VSV-OVA or LM-OVA were treated with 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) medium (including 5 mM NaCl, 115 mM KCl, 12 mM MgSO4, 25 mM MES, 10 µM nigericin, 10 µM monensin, and 1% Trixon X-100), which was adjusted to the indicated pH for 30 min at 37°C. The samples were then neutralized to pH 7.4 for 10 min, and the CFU or PFU were measured.

In vivo cytotoxicity assay

As previously described (Iborra et al., 2012), in short, splenocytes were split into two populations that were labeled as a high or intermediate concentrations of CFSE and then washed. CFSEhi cells were pulsed with 10 µM CFSE, and CFSEint cells were pulsed with 0.125 µM CFSE along with 10 nM OVA peptide SIINFEKL. Pulsed CFSEhi cells and CFSE int cells were then mixed equally and injected i.p. into syngeneic mice. After 24 h, the peritoneal lavage was obtained and analyzed by flow cytometry to measure in vivo killing.

Tumor mouse models

The B16-F10 cell line was purchased from ATCC (CRL-6475). B16-OVA was generated in-house from ATCC stock stably transfected with plasmid containing OVA. MC38 cell line was purchased from Kerafast (ENH204). Authentication was provided by ATCC or Kerafast. The cell lines were confirmed to be negative for mycoplasma contamination by PCR. B16-OVA and MC38 were cultured at 37°C in RPMI with 10% FCS. 5 × 105 tumor cells were injected s.c. with 100 µl in each flank. Tumor size was determined on the indicated days by the following formula: length × width × width × 0.5.

FITC uptake assay

As previously described (Tussiwand et al., 2015), in short, after shaving the hair on the abdomen, mice were treated with 40 µl of 1% hapten FITC (Sigma-Aldrich) that had been diluted in 1:1 dibutyl phthalate/acetone as antigen. 24 h later, the cells of skin-draining lymph nodes were stained for flow cytometric analysis.

BMDC adoptive transfer

For LM BMDC treatment, at day 0, 1 × 105 OT-I were injected into the mice. The mice were infected with 8,000 CFU LM-OVA on day 1. The next day, 2 × 105 DMSO- or HDSF-treated BMDCs cocultured with OVA were transferred i.v. into the mice. For the tumor BMDC treatment model, soluble OVA were added to BMDCs at day 5. The next day, 2 × 106 BMDCs were injected to mice i.v. After 9 d, 1 × 106 B16-OVA cells were injected into mice s.c. Tumor size was determined on the indicated days by the following formula: length × width × width × 0.5.

Phagosomal protein degradation assay

As previously described (Samie and Cresswell, 2015), in short, BMDCs were incubated at 37°C for 25 min with latex beads (Polyscience) that had been conjugated to OVA and washed once with cold 2% BSA in PBS. After removing the uningested beads by centrifugation, the cells were incubated for the indicated durations, disrupted in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], and 200× protease inhibitor cocktail) and centrifuged at 900 rpm for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatants containing the latex beads were collected and stained with anti-OVA antibody. The OVA protein remaining on the surface of the beads was then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Phagosomal pH assay