SUMMARY

The original discovery of enzymes that synthesize DNA using an RNA template appeared to contradict the central dogma of biology, in which information is transferred, in a unidirectional way, from DNA genes into RNA molecules. The paradigm-shifting discovery of RNA-dependent DNA polymerases, also called reverse transcriptases (RTs), reshaped existing views for how cells function; however, the scope of the impact RTs impose on biology had yet to be realized. In the decades of research since the early 1970s, the biomedical and biotechnological significance of retroviral RTs, as well as the evolutionarily related telomerase enzyme, has become exceedingly clear. One common theme that has emerged in the course of RT-related research is the central role of nucleic acid binding and dynamics during enzyme function. However, directly interrogating these dynamic properties is challenging because of the stochastic properties of biological macromolecules. In this review, we describe how the development of single-molecule biophysical techniques has opened new windows through which to observe the dynamic behavior of this remarkable class of enzymes. Specifically, we focus on how the powerful single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) method has been exploited to study the structure and function of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RT and telomerase ribonucleoprotein (RNP) enzymes. These exciting studies have refined our understanding of RT catalysis, have revealed unforeseen structural rearrangements between RTs and their nucleic acid substrates, and have helped to characterize the mode of action of RT-inhibiting drugs. We conclude with a discussion of how the ongoing development of single-molecule technologies will continue to empower researchers to probe RT mechanisms in new and exciting ways.

1. INTRODUCTION

Certain scientific discoveries have a way of broadly resonating with the basic research community. Such was the case with the initial discovery of viral reverse transcriptase (RT) enzymes in the 1970s by Baltimore and Temin (Baltimore 1970; Temin and Mizutani 1970). The capacity for an enzyme to synthesize DNA from an RNA template seemed to contradict the linearity of information flow put forth by Francis Crick in his famous lecture on the central dogma of biology (Crick 1970). Although Crick would personally contend that the existence of RT enzymes was in fact not at odds with his proposed model for information flow from nucleic acids to proteins, the discovery of these RNA-dependent DNA polymerases nevertheless altered the way in which scientists viewed the functional roles for RNA in biology and led to a Nobel Prize in Medicine just 5 years after the initial report was published on the discovery of RTs. A similar story can be told of the discovery of telomerase, the cellular RT that maintains telomeres in the majority of eukaryotic organisms. Telomeres are specialized chromatin structures that safeguard the genome from illicit recognition by DNA damage repair machinery (de Lange 2005). The mechanism of semiconservative DNA replication suggested that with each round of cell division there would be a gradual attrition of telomere length (Olovnikov 1971; Watson 1972; Allsopp et al. 1992). The formalization of this “end-replication problem” set into motion a search for an enzymatic activity that might maintain the ends of linear chromosomes. Greider and Blackburn discovered the telomerase enzyme in the mid-1980s (Greider and Blackburn 1987), for which they too were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Subsequent experiments showed that telomerase is a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex—part RNA, part protein. Interestingly, the catalytic telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) protein subunit shares many of the hallmark sequence motifs described previously for viral RT enzymes (Lingner et al. 1997; Nakamura and Cech 1998; Belfort et al. 2011). Once again, the discovery of an RT, this time one that carries its own RNA template as an integral enzyme subunit, motivated scientists to reevaluate existing views for functional roles of RNA in the modern world and, moreover, what implications these discoveries may have for the ancient RNA world and the origin of life.

2. IMPLICATIONS OF RT DISCOVERIES

The basic biology underlying the functions of each of these RTs is fascinating and continues to be the subject of intense research efforts. However, at the time of their initial discovery, few could have anticipated the far-reaching impacts of RTs on biotechnology and biomedical sciences. In the case of viral RTs, the AIDS epidemic, which broke out in the 1980s, made “retrovirus” a household word, and knowledge of the essential role of the RT enzyme in the viral life cycle contributed to the discovery of highly effective inhibitors of this class of enzymes, which to this day are a core component of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) treatments (Kohlstaedt et al. 1992; Spence et al. 1995; El Safadi et al. 2007). In the case of telomerase, the discovery that ∼90% of human cancer samples express abnormally high levels of telomerase placed the enzyme at the center of a massive research effort to better understand the role of telomerase in cancer progression, with the aim of producing novel diagnostic and therapeutic strategies (Kim et al. 1994). Although telomerase-based therapeutics have yet to realize their full potential, this research area remains a hotbed of biomedical inquiry.

With respect to biotechnology implications, the discovery of viral RTs has been particularly profound. Suddenly, through the use of robust RT enzymes, researchers were armed with a tool to convert all of the cellular information present in the more labile RNA form into a vastly more stable complementary DNA (cDNA) form. Once converted into cDNA, the entire RNA population of a cell, the transcriptome, could be sequenced and analyzed in ways that would be impossible without the RT enzyme. Thus, the case of the initial discovery of viral and cellular RTs serves as a quintessential example of how basic scientific inquiry can lead to paradigm shifts in biomedicine and biotechnology in ways that could not have been predicted at the outset.

3. ON THE EVOLUTION OF VIRAL RTS AND TELOMERASE

Phylogenetic analysis of RTs from retroviruses, telomerases, long-terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons, target-primed (TP) transposons, and group II introns permits one to group RT enzymes into evolutionarily related clusters (Curcio and Belfort 2007; Belfort et al. 2011; Gladyshev and Arkhipova 2011). However, the precise result of this type of analysis depends on how one roots the phylogenetic tree and therefore cannot provide conclusive information on the chronological progression of RT evolution. Nevertheless, two classes of models for the relationship between retroviral and telomerase RTs can be imagined: the RNA-first model and the protein-first model. In the RNA-first model, telomerase would have originated in an ancient RNA world from an ancestral catalytic RNA molecule. During the transition to DNA-based genomes, this ancient telomerase RNA (TR) molecule would have co-opted a protein RT enzyme (perhaps from a virus) to form a telomerase RNP complex similar to what we observe in modern cells. Support for this model comes from several observations. First, the discovery of catalytic RNAs makes possible an all RNA world, in which specialized RNAs performed many of the catalytic functions performed by proteins in the modern cell (Cech 1985). Second, although TRs from different organisms vary widely in both size and sequence, a conserved set of structural features has emerged (Theimer and Feigon 2006). Thus, RNA clearly plays functional roles beyond simply serving as a template for a protein RT, perhaps reflecting the possibility of an all RNA progenitor telomerase enzyme that later co-opted a protein RT subunit. The protein-first model provides an equally plausible theory for the evolution of RTs. In this model, an early protein RT would likely have evolved from an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP) that may have emerged during the transition from the RNA world to the modern RNP world that now exists. RdRPs are often used to root phylogenetic trees of protein RTs based on the assumption that such an enzyme would have provided an advantage to organisms needing to efficiently copy RNA genomes (Xiong and Eickbush 1990). From this point, the polymerase active site would have gradually adapted to use deoxyribonucleoside triphosphates as selective pressures began to drive organisms toward DNA-based genomes. In the case of telomerase evolution, the preexisting RT would have co-opted a cellular RNA as a stably associated enzyme component to facilitate the specialized telomerase catalytic cycle. Independent of which came first, protein RTs or an all RNA telomerase enzyme, it is nevertheless instructive to compare and contrast the properties of viral and telomerase RTs, both of which have recently been the subject of single-molecule analyses that have revealed remarkably dynamic nucleic acid-binding behaviors.

4. SINGLE-MOLECULE METHODS TO STUDY RT ENZYMES

The functional properties of biological systems emerge from highly dynamic and stochastic behaviors of individual molecules. Until relatively recently it was exceedingly difficult, if not impossible, to directly monitor the dynamic properties of a nucleic acid or protein molecule in real time. The challenge lies in the fact that macromolecular dynamics are typically obscured by the ensemble averaging intrinsic to most traditional biochemical and biophysical techniques which monitor the behavior of an asynchronous population of more than 1012 molecules in solution. Over the past several decades, the development of single-molecule tools has offered researchers an exciting new window into the complex behaviors of biological systems. These approaches have been used to study a wide range of systems, from protein synthesis by the ribosome to the folding dynamics of small catalytic RNAs (Zhuang et al. 2002; Tan et al. 2003; Wen et al. 2008; Perez and Gonzalez 2011). Among the most widely used single-molecule techniques are the force spectroscopy methods (i.e., optical trapping, magnetic tweezers, and atomic force microscopy) and the fluorescence-based approaches (i.e., fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and Förster resonance energy transfer, FRET). In the area of RT research, single-molecule FRET (smFRET) has been particularly powerful and will therefore be the focus of the present review. However, the interested reader is referred to any of a number of comprehensive technical reviews on single-molecule methods and their applications (Greenleaf et al. 2007; Deniz et al. 2008; Moffitt et al. 2008; Neuman and Nagy 2008; Roy et al. 2008; Tinoco and Gonzalez 2011).

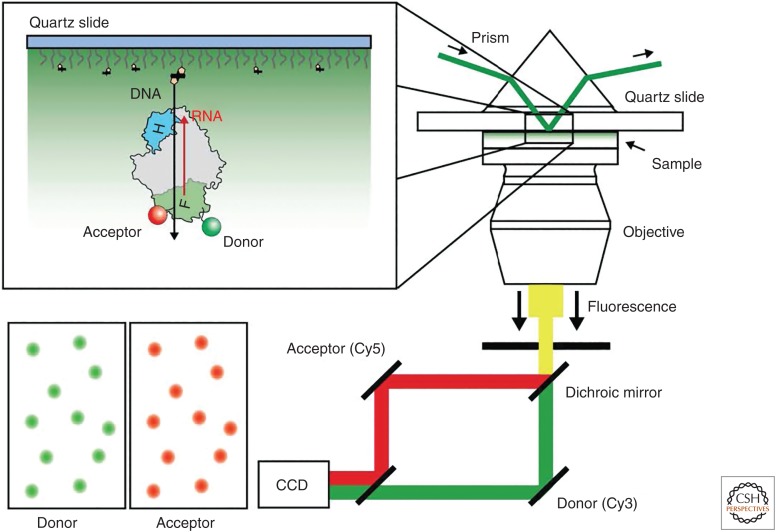

smFRET techniques, which detect the efficiency of non-radiative energy transfer between a directly excited donor dye and a nearby acceptor dye (Stryer and Haugland 1967), emerged early on as a method of choice for researchers interested in studying dynamic biological systems. FRET is typically measured as the background-corrected ratio of the acceptor dye intensity divided by the sum of the donor plus the acceptor dye intensities. In this way, FRET ratios approaching a value of zero reflect the dyes being far from each other, whereas FRET ratios approaching a value of one indicate the two dyes are in close proximity. The popularity of smFRET is in part due to the relative simplicity of the optical setups required to make the measurements, as well as the ability to rapidly collect statistically meaningful results by measuring the behaviors of hundreds to thousands of single molecules in parallel (Deniz et al. 1999; Best et al. 2007; Merchant et al. 2007; Schuler and Eaton 2008). Although there exists a variety of microscopy tools with which to measure FRET, total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy is among the most widely used techniques (Zhuang et al. 2000; Ha 2001; Axelrod 2003). A standard TIRF microscope used for a smFRET experiment is equipped with specific detection optics that split the image into the donor and acceptor spectral channels, as well as a very sensitive electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) camera, which readily improves signal-to-noise ratios to levels that permit detection of photons emitted by individual dye molecules (Fig. 1). The capacity of a TIRF microscope to measure FRET at the single-molecule level was first demonstrated in pioneering studies that focused on DNA and RNA molecules, which could be readily conjugated to FRET dyes in a site-specific manner (Ha et al. 1996, Weiss 1999). Since this time, smFRET has been used to study a large number of diverse biological systems, attributable in part to the emergence of dye-coupling techniques with which to site-specifically label proteins and nucleic acids (Murphy et al. 2004; Rasnik et al. 2004; Jager et al. 2005; Jager et al. 2006). In the following sections, we will describe selected examples in which single-molecule analysis has provided unique insight into the mechanistic properties of viral and TERTs, with a particular emphasis on the dynamic interaction between these fascinating enzymes and their nucleic acid substrates.

Figure 1.

Single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) microscope. smFRET measurements are often made using a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope. In the prism-type TIRF geometry, dye-labeled samples are immobilized onto a quartz microscope slide via biotin–streptavidin linkage. The appropriate excitation laser (532 nm shown here) is used to illuminate the sample at an angle, which causes total internal reflection of the incoming light because of the difference in the index of refraction of the quartz slide and the sample volume. In this way, the intensity of the evanescent field of light that propagates into the sample volume decays exponentially and dramatically enhances the single-to-noise ratio of the measurement. The emitted fluorescence of several hundred molecules in a single field of view is split using dichroic mirrors into separate acceptor and donor channels and captured by the electron-multiplying charge-coupled device (EMCCD) camera. Automated software routines are then used to analyze the raw movie data, and the FRET ratio can be calculated according to the simple expression FRET = IA/(ID + IA), in which IA and ID are the background-corrected intensities of the acceptor and donor dyes, respectively. The schematic depicts a human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase (HIV RT) enzyme immobilized onto a pegylated quartz slide using a biotinylated DNA substrate (black). HIV RT is shown in gray with the fingers and RNase H domains shown in green and blue, respectively. The RNA strand is shown in red. Biotinylated substrates are tethered to the slide surface using streptavidin (black rectangles). Biotin molecules are shown as yellow pentagons. An acceptor dye (red) is attached to the DNA and a donor dye (green) is attached to the enzyme.

5. HUMAN IMMUNODEFICIENCY VIRUS (HIV) RT

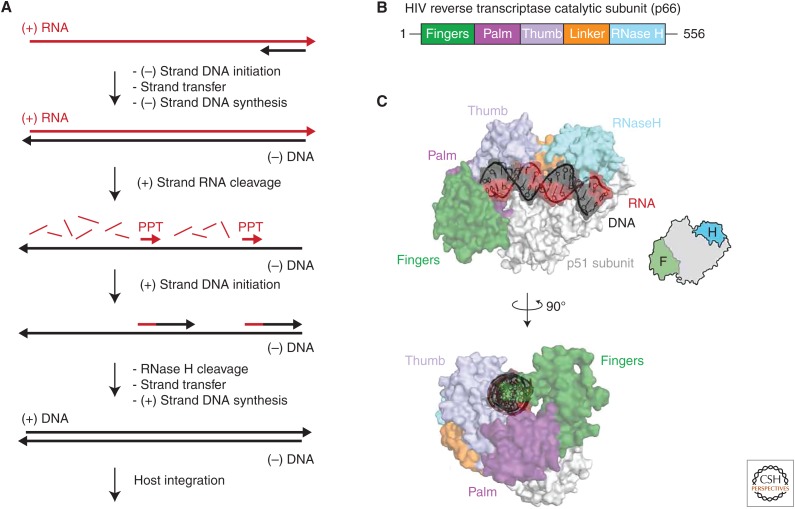

The type 1 HIV RT is a multifunction enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of the (+) strand viral RNA (vRNA) genome into a duplex DNA form that is competent for integration into the host genome (Fig. 2A) (Telesnitsky and Goff 1997). HIV RT is a heterodimeric protein complex that includes a small regulatory subunit (p51) and a large catalytic subunit (p66) that harbors two distinct enzyme active sites. The majority of the p66 polypeptide encodes a DNA polymerase domain comprised of the canonical fingers, palm, and thumb subdomains (Fig. 2B). In addition, p66 has a separate RNase H domain whose enzymatic activity is required to degrade the RNA within the RNA–DNA product intermediate before (+) strand DNA synthesis. During the viral life cycle, the single p66 subunit of HIV RT is responsible for both RNA-templated and DNA-templated DNA synthesis, as well as regulated RNA cleavage by the RNase H domain (Fig. 2A). Thus, during the various stages of proviral DNA synthesis, HIV RT interacts with a menagerie of nucleic acid substrates, including RNA, duplex DNA, and RNA–DNA hybrids. In addition, the specific structures engaged by the enzyme can also range from nicked duplexes, recessed ends, blunt ends, and 3′ or 5′ nucleic overhangs. Although biochemical and high-resolution structural studies continue to contribute to our understanding of the molecular recognition determinants between HIV RT and its nucleic acid substrates (Fig. 2C) (Sarafianos et al. 2009, Engelman and Cherepanov 2012), these static snapshots of the enzyme do not illuminate the mechanism for how HIV RT dynamically engages its substrates. To circumvent this limitation, researchers have recently used an elegant smFRET assay to directly monitor HIV RT-binding dynamics in real time (Abbondanzieri et al. 2008, Liu et al. 2008, Liu et al. 2010). In the following sections, we will describe several of these exciting findings, with a particular emphasis on how the use of single-molecule techniques revealed unforeseen properties of this fascinating and biomedically important enzyme.

Figure 2.

Human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase (HIV RT) catalysis and structure. (A) HIV RT catalysis. Following initiation of (−) strand DNA synthesis by the binding of host-cell transfer RNA to the viral HIV RT RNA (not shown), a short DNA primer (black) anneals to the 3′ end of the (+) strand RNA template (red). On completion of (−) strand DNA synthesis by the RT DNA polymerase domain, cleavage of the (+) strand RNA is performed by the RNase H domain to generate a template for (+) strand DNA synthesis. Two short polypurine-rich RNA tracts (PPT) left behind after RNase H cleavage then serve as primers to initiate DNA synthesis by the RT domain. A second round of RNase H cleavage removes the RNA primers on completion of (+) strand DNA synthesis, ultimately generating an integration-competent DNA copy of the viral genome. (B) Conserved domain organization of HIV RT p66 subunit. The conserved fingers, palm, and thumb domain are shown in green, purple, and violet, respectively. The HIV-specific linker and RNase H domain are shown in orange and light blue, respectively. (C) Structure of HIV RT. The domains of the p66 subunit are colored as described in panel B, with the p51 subunit shown in light gray and an ideal RNA/DNA helix shown in red and black as indicated. The HIV RT cartoon has the fingers and RNase H domains highlighted in green and blue, respectively.

6. CONFORMATIONAL DYNAMICS OF HIV RT ON NUCLEIC ACIDS

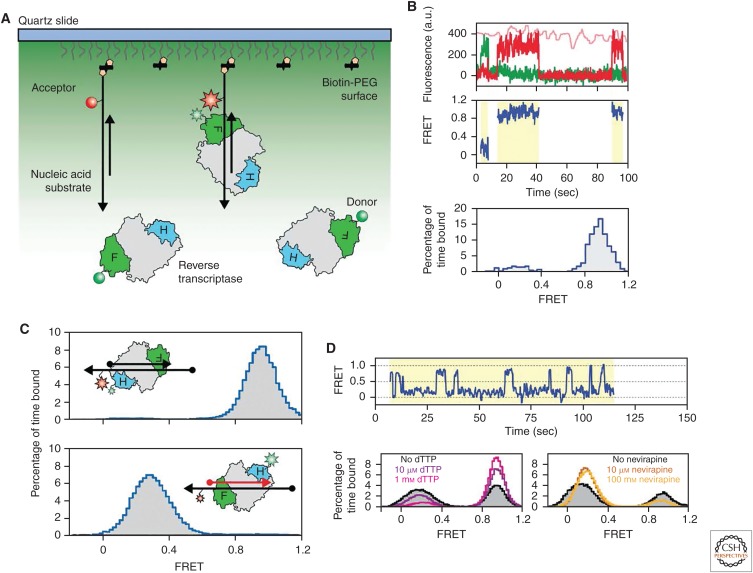

Given the diversity of nucleic acid-binding activities shown by HIV RT, and the a priori expectation for dynamic interconversion between distinct binding modes, the system was a natural candidate for single-molecule studies. Early work analyzed conformational heterogeneity of HIV RT in complex with a model RNA–DNA hybrid using a solution confocal microscope (Rothwell et al. 2003). Although informative, these initial experiments could not resolve time-dependent conformational changes within the RT–nucleic acid complexes. To address this challenge, Abbondanzieri et al. developed a powerful smFRET system with which to monitor real-time binding dynamics of HIV RT (Abbondanzieri et al. 2008). HIV RT enzymes were engineered to possess a single solvent-exposed cysteine residue located proximal to either the DNA polymerase active site or, conversely, the RNase H active site (Fig. 3A). By conjugating a FRET donor dye to one of these sites within HIV RT and placing an acceptor dye on the nucleic acid substrate, the investigators were able to unambiguously determine the binding orientation of the RT with respect to a variety of nucleic acid substrates (Fig. 3B). Initial experiments focused on understanding how the presence of an RNA, DNA, or chimeric primer bound to a DNA template-influenced RT binding (Fig. 3C). These experiments directly showed that HIV RT binds to RNA- and DNA-primed substrates with opposite binding orientations. If the primer is composed of DNA, the 3′ end of the primer is situated in the polymerase active site, poised to be extended by the RT. Conversely, if the primer was RNA, RT bound the RNA–DNA hybrid with the primer 3′ end proximal to the RNase H active site, in a DNA synthesis-incompetent state, and presumably poised for RNA cleavage. Taking the experiment a step further, the investigators next queried which part of the primer was being recognized by RT to direct the enzyme to bind in one orientation or the other. The finding was a surprise; the identity of the primer and, in turn, the binding orientation, was sensed on the primer 5′ end rather than the 3′ end. In other words, a chimeric primer that had nine DNA bases on the 5′ end followed by 10 RNA bases on the 3′ end bound to RT in a DNA synthesis-competent mode, a conclusion that was supported by accompanying biochemical experiments. These experiments provided the first demonstration of distinct substrate-dictated binding orientations of HIV RT, providing new insight into how RT efficiently mediates distinct forms of catalysis on different substrates.

Figure 3.

Conformational dynamics of human immunodeficiency virus reverse transcriptase (HIV RT). (A) Experimental setup for measuring dynamics of HIV RT binding to nucleic acid substrates. HIV RT is site-specifically labeled with a FRET donor dye (green circle). Biotinylated nucleic acid substrates (black) labeled with acceptor dye (red circle) are tethered to the slide surface, immersed in a solution containing FRET-labeled HIV RT, and imaged as described in Figure 1. (B) Individual HIV RT-binding events are detected by the onset of FRET between the donor and acceptor dyes (region of traces highlighted in yellow). Throughout the experiment, alternating excitation with a red laser that directly excites the acceptor dye is used to ensure the presence of an active acceptor dye (direct excitation of acceptor is shown as a light red trace). Data from multiple binding events taken in a particular experimental condition are compiled into a FRET histogram to reconstruct the distribution of FRET states sampled by HIV RT bound to the nucleic acid. (C) When the nucleic acid substrate is a DNA–DNA hybrid, HIV RT binds with the fingers domain proximal to the primer 3′ end, in the DNA polymerization-competent orientation, indicated as a high-FRET state when the donor dye is placed on the RNase H domain. In contrast, when the primer is comprised of RNA, the HIV RT binds in the opposite orientation, with the RNase H domain proximal to the RNA 3′ end, indicated by a low-FRET state. (D) HIV RT bound to a PPT RNA primer–DNA hybrid in the presence and absence of nucleotide or nonnucleoside RT inhibitors (NNRTI). The top panel shows a representative FRET trace with frequent interconversion between high- and low-FRET states indicating switching between the polymerase-competent and incompetent orientations when HIV RT is bound to the PPT RNA–DNA hybrid. The bottom left panel shows the FRET histogram for HIV RT bound to the PPT RNA–DNA hybrid in the presence of increasing concentrations of deoxythymidine triphosphate (dTTP) (purple and pink curves). Addition of the cognate dTTP biases the FRET distribution toward the higher FRET population, indicative of when the enzyme is in the polymerase-competent orientation. The bottom right panel shows the FRET histogram for HIV RT bound to the PPT RNA/DNA hybrid in the presence of increasing concentrations of the NNRTI, nevirapine (orange and yellow curves). Addition of nevirapine biases the FRET distribution toward the lower FRET population, indicative of when the enzyme is in the polymerase-incompetent orientation. (Adapted from Abbondanzieri et al. 2008, with permission, from Springer Nature ©2008.)

After HIV RT has catalyzed the formation of the RNA–DNA hybrid and subsequently used its RNase H activity to digest away the (+) strand RNA template, a specific polypurine tract (PPT) of the original RNA template remains behind to serve as a primer for (+) strand DNA synthesis (Rausch and Le Grice 2004). In contrast to generic RNA–DNA hybrids, the hybrid formed by the specialized PPT sequence is both refractory to RNase H cleavage and competent to serve as an efficient primer for the DNA polymerase activity. Using the smFRET approach, the investigators next tested a model PPT hybrid for binding by HIV RT. Unlike the other RNA primer substrates, which predominantly bound RT in the DNA synthesis-incompetent orientation, the PPT primer exhibited a mixture of both binding orientations (Fig. 3D). This result explains how this unique RNA–DNA hybrid is specifically recognized to prime (+) strand DNA synthesis. Surprisingly, the investigators also reported that HIV RT can dynamically interconvert between each binding orientation, without dissociating from the template. This result was very unexpected given the intricate network of protein–nucleic acid contacts revealed by high-resolution crystal structures. To probe the mechanism of RT “flipping” on its substrates, the investigators tested the effects of adding cognate or noncognate deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), as well as the clinically approved non-nucleoside RT inhibitor (NNRTI), nevirapine (Fig. 3D). Interestingly, the presence of the cognate dNTP altered the binding orientation equilibrium, biasing RT to bind in the DNA polymerization-competent conformation. On the other hand, the presence of the NNRTI, nevirapine, had the opposite effect and biased the binding of RT away from the DNA synthesis-competent orientation. The binding of a cognate dNTP or a NNRTI ligand is known to clamp down or open the polymerase fingers and thumb subdomains, respectively (Kohlstaedt et al. 1992; Spence et al. 1995; El Safadi et al. 2007). These structural impacts of ligand binding are consistent with the smFRET assay dynamic binding results. Thus, the use of smFRET to study the binding of HIV RT to diverse nucleic acid substrates not only revealed distinct binding orientations but also lead to the unexpected discovery of dynamic interconversion of RT between these states.

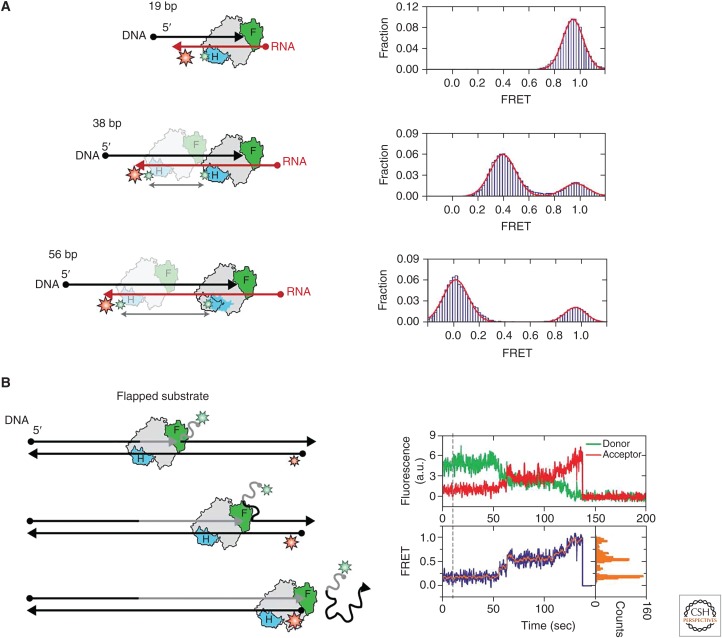

7. RT SLIDING, SUBSTRATE RECOGNITION, AND STRAND DISPLACEMENT SYNTHESIS

HIV RT must locate the 3′ end of the primer to promote DNA synthesis. This search process represents a considerable challenge during viral replication because RT is known to act distributively (Huber et al. 1989), synthesizing short segments of DNA while replicating the 9.2 kilobase viral genome. Thus, RT must repeatedly search and engage the 3′ end of the nascent DNA strand throughout the replication process. To investigate the mechanism of this search process, Liu et al. again used the smFRET technique to monitor RT-binding dynamics in real time (Liu et al. 2008). In this experiment, the investigators designed a set of model DNA primer-RNA template substrates of increasing length (Fig. 4A). When the DNA–RNA hybrid matched the RT footprint (∼19 base pairs [bp]), the RT bound in the DNA synthesis-competent orientation with the 3′ end of the DNA primer proximal to the polymerase active site. However, as the length of the hybrid was increased, RT showed a bimodal binding distribution consistent with the ability to engage each of the ends of the hybrid in a mutually exclusive manner. Moreover, analysis of smFRET time trajectories revealed dynamic “sliding” of the RT along the hybrid, with distinct pausing at preferred sites. To probe what type of structural changes were required to support RT sliding on DNA–RNA hybrids, the investigators again introduced either cognate dNTPs or the NNRTI, nevirapine. The presence of the cognate dNTP, which is known to clamp down the polymerase active site on the 3′ end of the DNA primer, stabilized RT in the DNA synthesis-competent binding mode. In contrast, the addition of nevirapine, which is known to loosen the grip of the polymerase active site for the hybrid, increased the frequency of back sliding along the DNA–RNA hybrid. In a separate experiment, a much longer duplex DNA substrate labeled at its terminus with a FRET acceptor dye was used. Because the DNA substrate was so large, the initial docking of a FRET donor-labeled HIV RT enzyme resulted in a zero FRET value. However, after a characteristic lag time the RT dynamically located the end of the DNA substrate. Strikingly, if the RT initially slid to the end of the DNA in a nonproductive-binding orientation for DNA synthesis, the enzyme dynamically flipped into the DNA synthesis-competent mode. These results provided a dramatic illustration of how a combination of DNA sliding and flipping can enhance the efficiency of the RT primer search process.

Figure 4.

Sliding and strand displacement synthesis by HIV RT. (A) HIV RT sliding on DNA–RNA substrates. HIV RT is shown in gray with the fingers and RNase H domains shown in green and blue, respectively. DNA is shown in black and RNA in red. An acceptor dye (red) is attached to the DNA and a donor dye (green) is attached to the enzyme. The top cartoon and panel indicate the enzyme orientation when HIV RT is bound to a short 19-bp hybrid, which corresponds to the size of the HIV RT footprint. The high FRET peak indicates that the enzyme is primed at the 3′ end of the DNA substrate in the polymerase-competent orientation. When the hybrid length is changed to 38 bp (middle cartoon and panel) two FRET populations are observed, including a high-FRET and medium-FRET peak. This bimodal FRET population is indicative of HIV RT engaging either end of the hybrid, but with a preference for the DNA 3′ end where it is bound in the polymerase-competent orientation. The bottom cartoon and panel depict HIV RT bound to a 56-bp DNA–RNA hybrid. The FRET panel on the right reveals a bimodal FRET distribution, with the major FRET peak close to 0, again demonstrating that the enzyme can bind at either end of the DNA–RNA hybrid but preferentially binds in the polymerase-competent state at the 3′ end of the DNA. (B) HIV RT strand displacement of flapped DNA. The flapped DNA is labeled with a donor dye (green) on the 5′ end and the template DNA strand is labeled with an acceptor dye (red) on the 5′ end. HIV RT binds to the flapped DNA substrate and catalyzes strand displacement to complete DNA synthesis (gray arrow), resulting in a gradual increase in FRET. A representative FRET trace is shown on the right with raw acceptor and donor intensities shown in the top panel, calculated FRET ratio shown in the bottom panel, and the corresponding FRET histogram of the dynamically sampled FRET states (orange). Peaks in the FRET histogram suggest that HIV RT preferentially pauses at specific stages of the strand displacement synthesis reaction. (Adapted from Liu et al. 2008, with permission, from AAAS.)

The single-stranded genomic vRNA transcript can fold into complex secondary structures. The propensity of RNA to fold into stable hairpins and other structures presents RT with yet another challenge during (−) strand DNA synthesis. As the RT progressively synthesizes the DNA product it must catalyze strand displacement of any structures that are encountered within the RNA template. This conundrum is magnified by the fact that RT frequently dissociates from its nucleic acid substrates, allowing the energetics of DNA and RNA nucleic acids to drive structural reorganization that can result in the production of “flapped” DNA substrates (Fig. 4B). Having characterized the ability of RT to slide on nucleic acid substrates, the investigators next asked whether this sliding activity may play a role in the productive binding and extension of flapped nucleic acids. In a series of elegant experiments, Liu et al. showed that the ability of RT to dynamically slide on its nucleic acid substrates facilitates rearrangement of the DNA–RNA hybrid structure to promote the DNA synthesis-competent state. Taken together, these studies further illuminated the complex and dynamic properties of RT binding to diverse nucleic acids, providing unique insights into how this multifaceted enzyme mediates various stages of the viral life cycle.

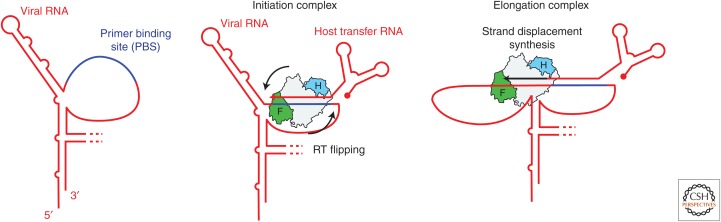

8. STRUCTURAL DYNAMICS OF THE HIV RT INITIATION COMPLEX

To initiate viral replication, HIV RT use a host cell–derived transfer RNA (tRNA) as a primer for the synthesis of (−) strand DNA (Marquet et al. 1995). This tRNA3Lys engages a specific region of the vRNA genomic transcript at a region termed the primer binding site (PBS). Once formed, the complex of tRNA–vRNA is bound by HIV RT to begin DNA synthesis. Once again using their smFRET approach, Liu et al. directly monitored HIV RT-binding dynamics on the physiologically important initiation complex (Liu et al. 2010). Interestingly, the investigators found that HIV RT binds the tRNA–vRNA substrate in predominantly the flipped orientation, wherein the RNase H domain is proximal to the primer 3′ end (Fig. 5). This result is consistent with their previously reported experiments that showed RT binding to random RNA–DNA hybrids supports the same DNA synthesis-incompetent mode (Abbondanzieri et al. 2008). Once bound to the initiation complex, RT faces the energetic challenge of strand displacement synthesis through a stable RNA hairpin structure within the vRNA template. Indeed, this structural roadblock is thought to underlie the observation that HIV RT shows substantial pausing at early stages of the initiation process before transitioning to a higher processivity elongation complex (Isel et al. 1996; Lanchy et al. 1998). To dissect the role of vRNA template structure during the initiation process, the investigators altered the native vRNA template hairpin to either destabilize or stabilize the structure. Strikingly, destabilization of the vRNA template hairpin permitted RT to preferentially bind in the DNA synthesis-competent mode, whereas mutations that enhanced the stability of the vRNA template hairpin had the opposite effect of promoting the flipped binding orientation. Thus, the structural properties of the vRNA template directly modulate the binding orientation of HIV RT and, in turn, the initiation efficiency. To further probe the role of hairpin structure in governing the initiation process, the investigators systematically tested the binding orientation of RT on tRNA–DNA chimeras corresponding to each successive step in the early initiation process. These experiments revealed that once RT adds six DNA bases to the tRNA primer, it can then efficiently bind in the DNA synthesis-competent orientation. Moreover, the HIV RT-binding orientation equilibrium measured on each substrate correlated with the DNA synthesis rate measured in ensemble biochemical experiments. Taken together, these observations lead to the hypothesis that six bases of HIV RT-catalyzed DNA synthesis should be sufficient to disrupt the native vRNA template hairpin structure. To test this notion, the investigators engineered a vRNA template RNA with FRET dyes incorporated at the base of the RNA hairpin structure. In this way, they showed that a tRNA–DNA chimera corresponding to six bases of DNA synthesis did in fact disrupt the vRNA template hairpin structure. Why might HIV have evolved to possess this metastable vRNA template hairpin that apparently reduces the efficiency of viral replication initiation? One possibility put forth by Liu et al. is that the vRNA template hairpin serves the function of slowing down viral replication so that other aspects of viral production, such as translation of envelope proteins, can keep pace. This model is consistent with reports that mutations that destabilize the vRNA template hairpin and increase the rate of initiation can have negative impacts on virion production (Beerens et al. 2001). Once again, the use of smFRET to directly monitor binding dynamics of HIV RT, as well as structural remodeling of its nucleic acid substrates, provided new insights into the mechanism of viral replication initiation.

Figure 5.

HIV RT initiation complex dynamics. HIV RT viral RNA is shown in red with the primer binding site (PBS) shown in blue (left). To form the initiation complex, a host transfer RNA anneals to the PBS and serves as a primer for HIV RT which binds to the hybrid and can dynamically interconvert between the polymerase-competent and incompetent orientations (middle). The presence of a stable RNA hairpin structure slows down the initiation process, in part by biasing the HIV RT-binding orientation toward the polymerase-incompetent state. After incorporation of six nascent deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs), the RNA secondary structure is destabilized, promoting rapid elongation of the product DNA by the HIV RT elongation complex (right).

9. TELOMERASE

The ends of linear chromosomes are capped by repetitive G-rich stretches of DNA that are the foundation for telomere structure (de Lange 2005, 2010). Because of incomplete DNA replication of chromosome termini caused by the end-replication problem, telomere DNA gradually shortens with each cell division (Olovnikov 1971; Watson 1972; Allsopp et al. 1992). Without a mechanism to counteract this shortening, telomeres become critically short and serve as a signal for the cell to undergo senescence or programmed cell death. This senescent state and eventual cell death is a necessary mechanism to prevent unrestricted cell division in somatic cells (Hayflick 1985). In contrast, cells that need to maintain higher levels of proliferative potential, such as stem cells and germ cells, express the specialized telomerase enzyme to maintain telomere length (Blackburn et al. 1989). The same principle holds true for most human cancer cell types, making telomerase an important biomedical drug target (Kim et al. 1994).

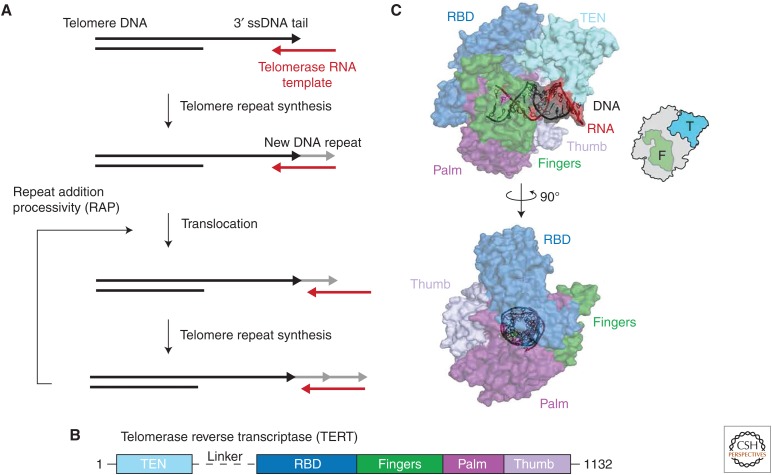

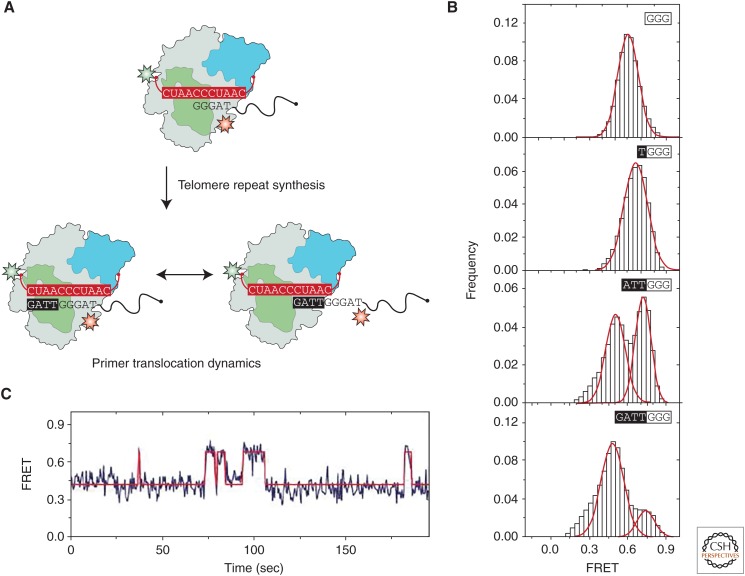

Telomerase is a RNP complex composed of a protein subunit, TERT, and an integral long noncoding RNA component, TR (Feng et al. 1995; Nakamura et al. 1997). TERT and TR constitute the telomerase catalytic core, whereas a number of additional species-specific proteins can also associate with the telomerase complex (de Lange 2005). TERTs are generally well conserved and share significant sequence homology with viral RT enzymes (Peng et al. 2001; Belfort et al. 2011). Telomerase is a canonical RT in the sense that it catalyzes a reverse transcription reaction to synthesize telomere DNA from its RNA template. However, telomerase also has additional specialized features that support its ability to synthesize multiple telomere DNA repeats during a single binding event (Greider 1991; Zhao et al. 2011). During catalysis, telomerase docks on to the 3′ single-stranded end of the telomere DNA tail, and reverse transcribes the integral template region within TR onto the end of the chromosome (Fig. 6A). Following the addition of a complete telomeric DNA repeat, telomerase must realign the nascent DNA with downstream template residues to prime a subsequent round of telomere repeat synthesis. The unique property of telomerase to recycle its internal RNA template and synthesize multiple telomere DNA repeats without dissociating from the telomere is termed repeat addition processivity (RAP). The inherently dynamic rearrangements associated with RAP have motivated the use of smFRET to study the telomerase mechanism.

Figure 6.

Telomerase catalysis and structural model. (A) The integral telomerase RNA (TR) template (red) anneals to the 3′ single-stranded (ss) tail of the telomere DNA (black). The RT domain of telomerase catalyzes a new telomere repeat (gray) followed by a translocation step to realign the nascent DNA repeat with the 3′ end of the RNA template. The reiterative process of telomere repeat synthesis followed by translocation is termed repeat addition processivity (RAP). (B) Conserved domain organization of telomerase reverse transcriptases (TERTs). The canonical fingers, palm, and thumb domain are shown in green, purple, and violet, respectively as represented for HIV RT in Figure 2. The telomerase-specific telomerase essential amino-terminal (TEN) domain and RNA-binding domain (RBD) are shown in light blue and dark blue, respectively. The telomerase linker region in between the TEN and RBD domains is indicated by a dotted line, which can be of varying length depending on the organism. (C) The structure shown is a homology model of human telomerase (Steczkiewicz et al. 2011) with the human TERT sequence threaded into the previously solved Tribolium castaneum structure of TERT bound to an ideal RNA–DNA hybrid (Mitchell et al. 2010) in complex with the Tetrahymena thermophila TEN domain (Jacobs et al. 2006). The domains of TERT are colored as described in B, with the ideal RNA–DNA helix shown in red and black as indicated. The telomerase cartoon has the fingers and TEN domains highlighted in green and blue, respectively.

The TERT protein is composed of four conserved domains: the telomerase essential amino-terminal (TEN) domain, the RNA-binding domain (RBD), the RT domain, and the carboxy-terminal extension (CTE) (Fig. 6B). The TEN domain is critical for maintaining RAP but is not required during the addition of a single telomere repeat (Zaug et al. 2008; Robart and Collins 2011). The RBD is responsible for establishing RNA–protein interactions between TERT and TR and is absolutely essential for telomerase activity (Lai et al. 2001; Huang et al. 2014; Jansson et al. 2015). The RT and CTE domains are homologous to the palm and thumb domains of canonical polymerases, respectively (Fig. 6C) (Wyatt et al. 2007; Gillis et al. 2008). The RNA component of telomerase is also composed of several conserved structural domains, although the sequence and length of TR varies widely between species (Theimer and Feigon 2006). Two regions of TR that appear to be generally conserved are the pseudoknot (PK)/template domain and the stem terminal element (STE) (Theimer et al. 2005), both of which are required to support wild-type (WT) levels of telomerase function in vitro and in vivo (Theimer et al. 2005; Richards et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2008; Cash et al. 2013; Huang et al. 2014). Although the functional role of the RNA template is self-evident, the contributions of the TR PK and STE remain the subject of continued investigation.

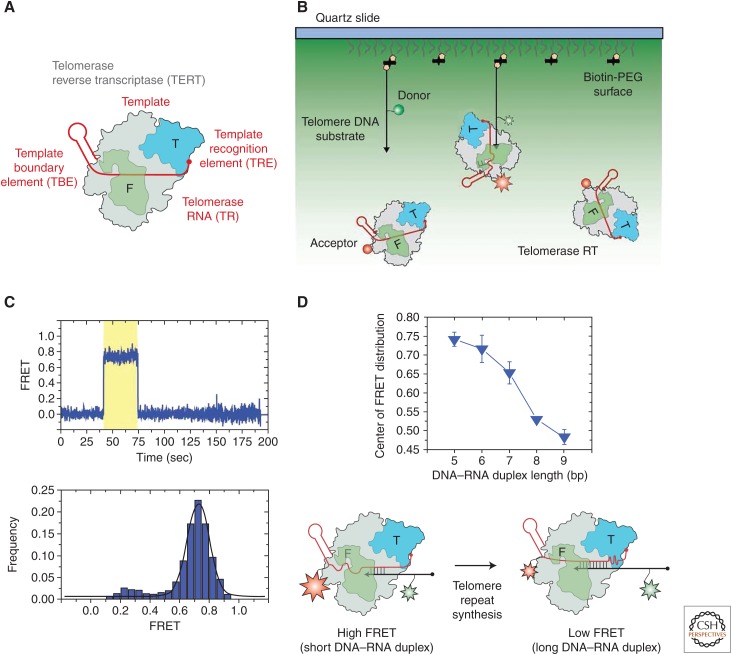

Single-molecule techniques are particularly well suited to help tease apart the dynamics that occur during telomerase catalysis and have the added benefit of requiring a relatively small amount of sample material, a feature that is particularly relevant in telomerase research given the challenges associated with producing large amounts of homogeneous enzyme for biochemical and biophysical experiments. As in the case of HIV RT research, smFRET has so far emerged as the method of choice for studying the assembly and structural dynamics of telomerase at the single-molecule level (Wu et al. 2010; Berman et al. 2011; Hengesbach et al. 2012; Parks and Stone 2014; Akiyama et al. 2015; Parks et al. 2017; Shastry et al. 2018). In the following sections, we highlight selected examples in which smFRET has been used to study the structure and function of Tetrahymena thermophila and human telomerase.

10. STRUCTURAL DYNAMICS OF TETRAHYMENA THERMOPHILA TELOMERASE

Telomerase was initially discovered in the ciliated protozoan Tetrahymena thermophila and has since been extensively biochemically characterized. (Greider and Blackburn 1987). In the course of this work, several regions within Tetrahymena TR were shown to be critical for RAP (Greider and Blackburn 1989, Gilley and Blackburn 1999; Lai et al. 2002; Richards et al. 2006), including the template recognition element (TRE) downstream from the template and the template boundary element (TBE) just upstream of the template (Fig. 7A). In a recent study, Berman and Akiyama et al. designed an incisive experiment to show compression and extension of the TRE and TBE regions at different stages of telomerase activity (Berman et al. 2011). The investigators labeled either the TRE or the TBE with an acceptor dye and measured FRET to a donor dye incorporated into the DNA primer. In this way, individual binding events of telomerase from solution to surface-immobilized DNA primers could be detected by FRET in real time (Figs. 7B and C). DNA primers corresponding to different repeat extension lengths were used to measure the FRET distribution during different stages of catalysis. The experimental results showed that when the TBE is labeled with the acceptor, FRET dramatically decreases as a function of DNA-primer length, indicating that this region is being extended during catalysis (Fig. 7D). Conversely, when the acceptor dye is on the TRE, FRET was found to slightly increase as a function of DNA-primer length, indicating that the single-stranded region between the template and the TRE is being compressed during the addition of a repeat. Together, these data suggested that there are both compression and extension of the single-stranded RNA regions surrounding the template during the synthesis of each telomere repeat, leading the investigators to propose “the accordion model” for telomerase function (Fig. 7D). In subsequent experiments, the investigators showed that RNA backbone connectivity is required between the template and both upstream and downstream single-stranded regions of TER, indicating that the compaction of the TRE and the expansion of the single-stranded region between the TBE and the template must be coupled during catalysis. In more recent work, a high-resolution crystal structure of Tetrahymena TERT–RBD bound to the TBE RNA fragment was reported (Jansson et al. 2015). This structure was consistent with the notion that accumulating tension in the flexible RNA regions flanking the template serves to enforce proper template boundary definition in Tetrahymena telomerase. An interesting open question is whether a similar mechanism for template boundary definition exists in other telomerase systems.

Figure 7.

Structural dynamics within telomerase RNA during catalysis. (A) Telomerase ribonucleoprotein (RNP) composition. TERT is depicted in gray with the TEN domain shown in blue and the fingers domain shown in green. A highly oversimplified depiction of telomerase RNA is shown in red with the template, template recognition element (TRE), and template boundary element (TBE) indicated. (B) Experimental setup to detect binding of individual telomerase complexes to surface-immobilized biotinylated telomere DNA substrates. Telomere DNA primers are immobilized to a pegylated quartz surface via a biotin–streptavidin linkage. Streptavidin is shown as black rectangles and biotin is depicted as yellow pentagons. The DNA (black) is labeled with a donor dye (green circle) and the telomerase RNA subunit (red) is labeled with an acceptor dye (red circle). (C) Individual TERT-binding events are detected by the onset of FRET between the donor and acceptor dyes (region of trace highlighted in yellow). A representative smFRET trace showing the dynamic association of a telomerase enzyme from solution with a surface-immobilized telomere DNA primer (top panel). Many individual binding events are collected and compiled into a FRET distribution characterizing a particular binding interaction (bottom panel). (D) Observed FRET value decreases as the DNA–RNA hybrid is elongated, indicative of the RNA in the template and TBE being extended (top panel). In the bottom panel, the RNA accordion model is shown, which describes the reciprocal compression and extension of the single-stranded regions of telomerase RNA flanking the template observed during the telomere repeat synthesis reaction. (Adapted, with permission, from Berman et al. 2011.)

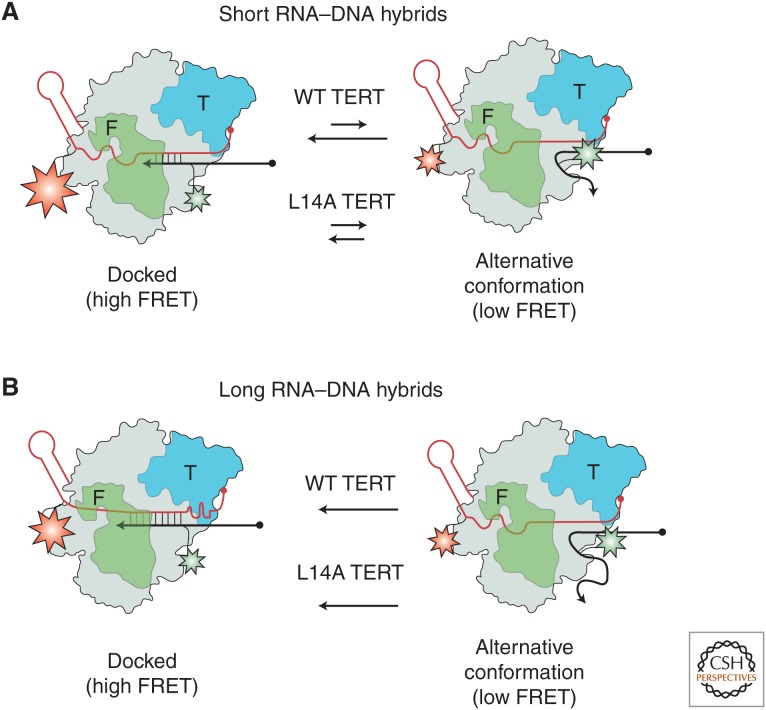

Another focus of intense research during the past few years has been on understanding how nucleic acid dynamics are coupled with and regulated by TERT interactions. Specifically, the telomerase TEN domain has been implicated in making both RNA and DNA interactions during catalysis and is absolutely essential for RAP (O’Connor et al. 2005; Jacobs et al. 2006; Zaug et al. 2008; Robart and Collins 2011). An interesting study by Akiyama et al. used smFRET to probe the role of the Tetrahymena TEN domain in stabilizing RNA–DNA hybrids in the telomerase active site (Akiyama et al. 2015). Using a similar experimental strategy to that described earlier, the binding of dye-labeled telomerase from solution to a surface-immobilized DNA primer was monitored by smFRET. The aim of the study was to investigate how the DNA primer–binding dynamics varied as a function of template RNA–DNA primer hybrid length (Fig. 8). When using a DNA primer sequence that could only form a 5-bp hybrid with the RNA template, the investigators observed a predominantly stable high-FRET state indicative of the primer being docked in the telomerase active site (Fig. 8A). However, the investigators also noted that on occasion, a transient excursion to a much lower FRET state was observed, which they named an “alternative conformation,” in which telomerase is stably bound to the DNA but the 3′ end of the primer is not in the “docked conformation.” As expected, when a DNA- primer sequence with a greater degree of complementarity to the RNA template was used (9 bp), only a single FRET state was observed corresponding to the docked conformation (Fig. 8B). These experiments with WT telomerase on DNA primers of varying lengths showed the power of smFRET to reveal internal structural dynamics of nucleic acids bound to the telomerase enzyme.

Figure 8.

The telomerase essential amino-terminal (TEN) domain stabilizes short RNA–DNA hybrids. (A) Single-molecule experiments with wild-type (WT) Tetrahymena telomerase revealed DNA-binding dynamics in the RT active site. TERT is depicted in gray with the TEN domain shown in blue and the fingers domain shown in green. TR (red) is labeled with an acceptor dye (red) and the DNA primer (black) is labeled with a donor dye (green). When telomerase was bound to a DNA primer that can form a 5-bp RNA–DNA hybrid in the active site, telomerase predominantly bound with the 3′ end of the DNA positioned in the RT active site (high FRET). In addition, the DNA occasionally sampled an alternative conformation (low FRET) in which the enzyme remains bound but the DNA is not in the active site. When the same experiment was performed using telomerase harboring a mutation in the TEN domain (L14A) that disrupts RAP, the DNA was found to sample the alternative state with significantly higher frequency. (B) When a telomere DNA primer capable of making a 9-bp RNA–DNA hybrid was used, both the WT and mutant telomerases showed stable binding of the 3′ end of the DNA in the RT active site. Taken together, these results suggested that the TEN domain is required to stabilize the binding of a short RNA–DNA hybrid in the RT active site at the start of each round of telomere DNA repeat synthesis.

Next, the investigators set out to investigate the impact of a previously reported separation of function mutation (L14A) in the TERT–TEN domain that was shown to significantly diminish RAP without impacting DNA binding (Zaug et al. 2008). When telomerase harboring the L14A TEN mutation bound to the DNA primer that formed a 5 bp hybrid, the investigators discovered a dramatic increase in the dynamics of the 3′ end of the DNA (Fig. 8A). In contrast, when the mutant TERT was bound to the primer capable of forming the longer 9-bp hybrid, the FRET distribution matched the WT behavior. Taken together, these results suggested that one function of the TEN domain is to stabilize short DNA–RNA hybrids in the telomerase active site, which represents an obligatory intermediate during each successive round of telomere repeat addition. To test this prediction, the investigators turned to ensemble DNA-primer extension assays and showed that WT telomerase was able to extend short DNA–RNA hybrids, whereas the L14A mutant telomerase was not. At the moment, it remains unclear whether the TEN domain stabilizes short DNA–RNA hybrids in the telomerase active site via direct interactions or if the effect is mediated through additional protein contacts. Interestingly, smFRET was recently used to study the binding dynamics of a yeast TEN domain to different nucleic acid substrates (Shastry et al. 2018). In this system, it was found that the yeast TEN domain binds preferentially to DNA–RNA hybrids, consistent with the model that emerged from the earlier Tetrahymena experiments (Akiyama et al. 2015). In the case of the human TEN domain, biochemical data also suggest a similar role in mediating DNA–RNA hybrid-binding dynamics (Moriarty et al. 2004; Wyatt et al. 2007; Wu and Collins 2014), but further biophysical investigation is required to dissect the precise contributions of the TEN domain to telomerase function in these diverse systems.

11. NUCLEIC ACID DYNAMICS DURING HUMAN TELOMERASE CATALYSIS

Although the Tetrahymena system has provided valuable insight into telomerase function, studies of human telomerase are understandably of greater biomedical relevance. However, because of the larger size of human telomerase, in particular the RNA component (451 nucleotides compared with 159 in Tetrahymena), human telomerase is more difficult to reconstitute into a functional enzyme in vitro. To circumvent this problem, a modified reconstitution protocol using only the two critical human telomerase RNA (hTR) domains required for catalysis, the PK/template and STE domains, was established (Chen and Greider 2003). This approach simplifies the assembly of human telomerase while still maintaining WT levels of telomerase activity, and also facilitates reconstitution of human telomerase with dye-labeled RNA, an advance that has led to several exciting studies focused on nucleic acid dynamics during human telomerase catalysis.

In one example, Parks and Stone used a series of strategically designed smFRET experiments to investigate DNA conformation and dynamics during the human telomerase catalytic cycle (Parks and Stone 2014). To study DNA dynamics, the investigators examined FRET distributions at different stages of telomerase catalysis using a stationary donor dye on the RNA and an acceptor dye on the human telomere primer (TTAGGG)3 (Fig. 9A,B). This specific primer sequence was shown previously to support exceedingly long-lived telomerase-binding interactions (Wallweber et al. 2003), permitting the investigators to surface-immobilize prebound “stalled” telomerase–DNA complexes. To measure DNA dynamics at different stages of telomere repeat synthesis, a mixture of specific dNTPs and dideoxynucleotide triphosphates (ddNTPs) were added to surface-immobilized telomerase enzymes. The combination of various dNTPs and ddNTPs allowed the enzyme to extend to the desired extension product and then stall because of incorporation of a chain-terminating ddNTP. When telomerase was immobilized in the absence of dNTPs, a unimodal and stable FRET population was observed (Fig. 9B). Strikingly, after the addition of TTA to the primer an unexpected bimodal FRET population was observed (Fig. 9B). This distribution consisted of the previously observed high-FRET peak, corresponding to the DNA primer bound in the active site, as well as a new lower FRET population. Finally, incorporation of the sequence TTAG completed the synthesis of a telomere DNA repeat, which further biased the FRET distribution toward the new lower FRET state (Fig. 9B).

Figure 9.

DNA dynamics during human telomerase catalysis. (A) Human telomerase was reconstituted and labeled with a donor dye upstream of the RNA template. Enzyme was prebound to a dye-labeled telomere DNA primer ending in the sequence -GGG, which binds with very high affinity. Enzyme–DNA complexes were then surface-immobilized and imaged in a TIRF microscope. TERT is shown in gray with the fingers and TEN domains shown in green and blue, respectively. The DNA primer (black) is labeled with an acceptor dye (red) and the RNA (red) is labeled with a donor dye (green). After addition of dNTPs and completion of a telomere repeat, the newly synthesized repeat adopts two distinct binding conformations, either annealed to the RNA template in the active site (left, high FRET) or realigned to the 5′ end of the template, poised for another round of telomere repeat addition (right, low FRET). (B) When complexes bound to the -GGG primer are imaged and data compiled into a FRET histogram, a single high-FRET population is observed (top panel). After addition of a single dideoxythymidine triphosphate (ddTTP) to the nascent telomere repeat, a single FRET peak is still observed (second panel from the top). In contrast, on addition of dTTP and dideoxyadenosine triphosphate (ddATP) to the growing DNA primer, a bimodal FRET distribution is observed, with a new lower FRET population emerging (second panel from the bottom). After addition of dTTP, deoxyadenosine triphosphate (dATP) and dideoxyguanosine triphosphate (ddGTP), a full repeat has been synthesized, and the major FRET population observed is the low-FRET peak corresponding to the telomere repositioned at the 3′ end of the template, primed for another round of telomere synthesis. (C) A representative FRET trace of a DNA primer that has been extended to complete a single repeat. The dynamic transitions observed in the trajectory represent the 3′ end of the DNA primer sampling different complementary registers of the TR template. The data were fit with a hidden Markov model (HMM) yielding idealized FRET trajectories that were used to analyze the kinetics of the DNA realignment process (red). (Adapted, with permission, from Parks and Stone 2014.)

A series of carefully designed control experiments lead the investigators to interpret the lower FRET population that arises at the end of the repeat synthesis reaction to represent the dynamic repositioning of the primer 3′ end to the 3′ side of the RNA template, thus priming for another round of repeat addition (Fig. 9A). This realignment substep is often drawn as a necessary intermediate during telomerase RAP; however, the single-molecule studies provided the first direct observation of a telomere DNA primer sampling different binding registers of the RNA template (Fig. 9C). Interestingly, kinetic analysis of individual FRET time traces revealed that the rate constant for realignment of the 3′ end of the nascent telomere DNA product was ∼100-fold faster than estimates for the rate constant governing the complete translocation process required for RAP (Latrick and Cech 2010). This result is interesting because many in the telomerase field anticipated that dissociation and realignment of the nascent DNA product would impose a large energetic barrier to RAP. However, the smFRET study suggested that some other step during translocation required for RAP, perhaps short DNA–RNA hybrid capture and or TERT protein conformational changes in the telomerase active site, are in fact rate limiting.

12. CONCLUSIONS AND PERSPECTIVES

In each of the cases described within this review, smFRET provided a new window into the complex binding properties between the RT and its nucleic acid substrates. Results from these studies show certain functional similarities between the viral and telomerase RTs, in that each must orchestrate distinct binding nucleic acid-binding modes depending on what stage of catalysis the enzyme is mediating. The data have been particularly illuminating in the case of HIV RT, in large part attributable to the extensive high-resolution structural data that exist. This point highlights the strong complementarity of single-molecule science with other structural and biochemical methods. As improved structural models for telomerase accumulate, we anticipate smFRET will continue to serve as a means to test specific models for how protein and RNA structural changes mediate telomerase function. Additionally, although both TERT and HIV RT have been well studied using smFRET, other related RTs such as the group II intron encoded protein (IEP) as well as the spliceosomal protein Prp8 are less well characterized in terms of their nucleic acid–handling properties. The recent discovery of the structures of several group II intron IEPs (Qu et al. 2016; Zhao and Pyle 2016) as well as key components of the spliceosome (Galej et al. 2013; Plaschka et al. 2017; Wilkinson et al. 2017) should provide the necessary framework required to design effective smFRET experiments to study these related RTs and their nucleic acid substrates. Indeed, as new and improved biophysical technologies emerge, researchers will become ever better prepared to probe deeper into the functional properties of RT enzymes, no doubt uncovering many unexpected discoveries along the way.

Footnotes

Editors: Thomas R. Cech, Joan A. Steitz, and John F. Atkins

Additional Perspectives on RNA Worlds available at www.cshperspectives.org

References

- Abbondanzieri EA, Bokinsky G, Rausch JW, Zhang JX, Le Grice SF, Zhuang X. 2008. Dynamic binding orientations direct activity of HIV reverse transcriptase. Nature 453: 184–189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama BM, Parks JW, Stone MD. 2015. The telomerase essential N-terminal domain promotes DNA synthesis by stabilizing short RNA-DNA hybrids. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 5537–5549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allsopp RC, Vaziri H, Patterson C, Goldstein S, Younglai EV, Futcher AB, Greider CW, Harley CB. 1992. Telomere length predicts replicative capacity of human fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci 89: 10114–10118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod D. 2003. Total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy in cell biology. Methods Enzymol 361: 1–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltimore D. 1970. RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of RNA tumour viruses. Nature 226: 1209–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerens N, Groot F, Berkhout B. 2001. Initiation of HIV-1 reverse transcription is regulated by a primer activation signal. J Biol Chem 276: 31247–31256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belfort M, Curcio MJ, Lue NF. 2011. Telomerase and retrotransposons: Reverse transcriptases that shaped genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 20304–20310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman AJ, Akiyama BM, Stone MD, Cech TR. 2011. The RNA accordion model for template positioning by telomerase RNA during telomeric DNA synthesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 18: 1371–1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Best RB, Merchant KA, Gopich IV, Schuler B, Bax A, Eaton WA. 2007. Effect of flexibility and cis residues in single-molecule FRET studies of polyproline. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 18964–18969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH, Greider CW, Henderson E, Lee MS, Shampay J, Shippen-Lentz D. 1989. Recognition and elongation of telomeres by telomerase. Genome 31: 553–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash DD, Cohen-Zontag O, Kim NK, Shefer K, Brown Y, Ulyanov NB, Tzfati Y, Feigon J. 2013. Pyrimidine motif triple helix in the Kluyveromyces lactis telomerase RNA pseudoknot is essential for function in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci 110: 10970–10975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech TR. 1985. Self-splicing RNA: Implications for evolution. Int Rev Cytol 93: 3–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JL, Greider CW. 2003. Template boundary definition in mammalian telomerase. Genes Dev 17: 2747–2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick F. 1970. Central dogma of molecular biology. Nature 227: 561–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio MJ, Belfort M. 2007. The beginning of the end: Links between ancient retroelements and modern telomerases. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 9107–9108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. 2005. Shelterin: The protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev 19: 2100–2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. 2010. How shelterin solves the telomere end-protection problem. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol 75: 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz AA, Dahan M, Grunwell JR, Ha T, Faulhaber AE, Chemla DS, Weiss S, Schultz PG. 1999. Single-pair fluorescence resonance energy transfer on freely diffusing molecules: Observation of Forster distance dependence and subpopulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 3670–3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deniz AA, Mukhopadhyay S, Lemke EA. 2008. Single-molecule biophysics: At the interface of biology, physics and chemistry. J R Soc Interface 5: 15–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Safadi Y, Vivet-Boudou V, Marquet R. 2007. HIV-1 reverse transcriptase inhibitors. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 75: 723–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelman A, Cherepanov P. 2012. The structural biology of HIV-1: Mechanistic and therapeutic insights. Nat Rev Microbiol 10: 279–290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J, Funk WD, Wang SS, Weinrich SL, Avilion AA, Chiu CP, Adams RR, Chang E, Allsopp RC, Yu J, et al. 1995. The RNA component of human telomerase. Science 269: 1236–1241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galej WP, Oubridge C, Newman AJ, Nagai K. 2013. Crystal structure of Prp8 reveals active site cavity of the spliceosome. Nature 493: 638–643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilley D, Blackburn EH. 1999. The telomerase RNA pseudoknot is critical for the stable assembly of a catalytically active ribonucleoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci 96: 6621–6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillis AJ, Schuller AP, Skordalakes E. 2008. Structure of the Tribolium castaneum telomerase catalytic subunit TERT. Nature 455: 633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladyshev EA, Arkhipova IR. 2011. A widespread class of reverse transcriptase-related cellular genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 20311–20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenleaf WJ, Woodside MT, Block SM. 2007. High-resolution, single-molecule measurements of biomolecular motion. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct 36: 171–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW. 1991. Telomerase is processive. Mol Cell Biol 11: 4572–4580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. 1987. The telomere terminal transferase of Tetrahymena is a ribonucleoprotein enzyme with two kinds of primer specificity. Cell 51: 887–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. 1989. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature 337: 331–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T. 2001. Single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Methods 25: 78–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha T, Enderle T, Ogletree DF, Chemla DS, Selvin PR, Weiss S. 1996. Probing the interaction between two single molecules: Fluorescence resonance energy transfer between a single donor and a single acceptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci 93: 6264–6268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L. 1985. The cell biology of aging. Clin Geriatr Med 1: 15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hengesbach M, Kim NK, Feigon J, Stone MD. 2012. Single-molecule FRET reveals the folding dynamics of the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot domain. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 51: 5876–5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Brown AF, Wu J, Xue J, Bley CJ, Rand DP, Wu L, Zhang R, Chen JJ, Lei M. 2014. Structural basis for protein-RNA recognition in telomerase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 507–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber HE, McCoy JM, Seehra JS, Richardson CC. 1989. Human immunodeficiency virus 1 reverse transcriptase. Template binding, processivity, strand displacement synthesis, and template switching. J Biol Chem 264: 4669–4678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isel C, Lanchy JM, Le Grice SF, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B, Marquet R. 1996. Specific initiation and switch to elongation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 reverse transcription require the post-transcriptional modifications of primer tRNA3Lys. EMBO J 15: 917–924. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs SA, Podell ER, Cech TR. 2006. Crystal structure of the essential N-terminal domain of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 13: 218–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager M, Michalet X, Weiss S. 2005. Protein–protein interactions as a tool for site-specific labeling of proteins. Protein Sci 14: 2059–2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager M, Nir E, Weiss S. 2006. Site-specific labeling of proteins for single-molecule FRET by combining chemical and enzymatic modification. Protein Sci 15: 640–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson LI, Akiyama BM, Ooms A, Lu C, Rubin SM, Stone MD. 2015. Structural basis of template-boundary definition in Tetrahymena telomerase. Nat Struct Mol Biol 22: 883–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NK, Zhang Q, Zhou J, Theimer CA, Peterson RD, Feigon J. 2008. Solution structure and dynamics of the wild-type pseudoknot of human telomerase RNA. J Mol Biol 384: 1249–1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, Harley CB, West MD, Ho PL, Coviello GM, Wright WE, Weinrich SL, Shay JW. 1994. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science 266: 2011–2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohlstaedt LA, Wang J, Friedman JM, Rice PA, Steitz TA. 1992. Crystal structure at 3.5 Å resolution of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase complexed with an inhibitor. Science 256: 1783–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CK, Mitchell JR, Collins K. 2001. RNA binding domain of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol Cell Biol 21: 990–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CK, Miller MC, Collins K. 2002. Template boundary definition in Tetrahymena telomerase. Genes Dev 16: 415–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanchy JM, Keith G, Le Grice SF, Ehresmann B, Ehresmann C, Marquet R. 1998. Contacts between reverse transcriptase and the primer strand govern the transition from initiation to elongation of HIV-1 reverse transcription. J Biol Chem 273: 24425–24432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latrick CM, Cech TR. 2010. POT1-TPP1 enhances telomerase processivity by slowing primer dissociation and aiding translocation. EMBO J 29: 924–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingner J, Hughes TR, Shevchenko A, Mann M, Lundblad V, Cech TR. 1997. Reverse transcriptase motifs in the catalytic subunit of telomerase. Science 276: 561–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Abbondanzieri EA, Rausch JW, Le Grice SF, Zhuang X. 2008. Slide into action: Dynamic shuttling of HIV reverse transcriptase on nucleic acid substrates. Science 322: 1092–1097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Harada BT, Miller JT, Le Grice SF, Zhuang X. 2010. Initiation complex dynamics direct the transitions between distinct phases of early HIV reverse transcription. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 1453–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquet R, Isel C, Ehresmann C, Ehresmann B. 1995. tRNAs as primer of reverse transcriptases. Biochimie 77: 113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merchant KA, Best RB, Louis JM, Gopich IV, Eaton WA. 2007. Characterizing the unfolded states of proteins using single-molecule FRET spectroscopy and molecular simulations. Proc Natl Acad Sci 104: 1528–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell M, Gillis A, Futahashi M, Fujiwara H, Skordalakes E. 2010. Structural basis for telomerase catalytic subunit TERT binding to RNA template and telomeric DNA. Nat Struct Mol Biol 17: 513–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt JR, Chemla YR, Smith SB, Bustamante C. 2008. Recent advances in optical tweezers. Annu Rev Biochem 77: 205–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty TJ, Marie-Egyptienne DT, Autexier C. 2004. Functional organization of repeat addition processivity and DNA synthesis determinants in the human telomerase multimer. Mol Cell Biol 24: 3720–3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy MC, Rasnik I, Cheng W, Lohman TM, Ha T. 2004. Probing single-stranded DNA conformational flexibility using fluorescence spectroscopy. Biophys J 86: 2530–2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TM, Cech TR. 1998. Reversing time: Origin of telomerase. Cell 92: 587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura TM, Morin GB, Chapman KB, Weinrich SL, Andrews WH, Lingner J, Harley CB, Cech TR. 1997. Telomerase catalytic subunit homologs from fission yeast and human. Science 277: 955–959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman KC, Nagy A. 2008. Single-molecule force spectroscopy: Optical tweezers, magnetic tweezers and atomic force microscopy. Nat Methods 5: 491–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor CM, Lai CK, Collins K. 2005. Two purified domains of telomerase reverse transcriptase reconstitute sequence-specific interactions with RNA. J Biol Chem 280: 17533–17539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olovnikov AM. 1971. [Principle of marginotomy in template synthesis of polynucleotides]. Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR 201: 1496–1499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks JW, Stone MD. 2014. Coordinated DNA dynamics during the human telomerase catalytic cycle. Nat Commun 5: 4146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks JW, Kappel K, Das R, Stone MD. 2017. Single-molecule FRET-Rosetta reveals RNA structural rearrangements during human telomerase catalysis. RNA 23: 175–188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Y, Mian IS, Lue NF. 2001. Analysis of telomerase processivity: Mechanistic similarity to HIV-1 reverse transcriptase and role in telomere maintenance. Mol Cell 7: 1201–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez CE, Gonzalez RL Jr, 2011. In vitro and in vivo single-molecule fluorescence imaging of ribosome-catalyzed protein synthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol 15: 853–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plaschka C, Lin PC, Nagai K. 2017. Structure of a pre-catalytic spliceosome. Nature 546: 617–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu G, Kaushal PS, Wang J, Shigematsu H, Piazza CL, Agrawal RK, Belfort M, Wang HW. 2016. Structure of a group II intron in complex with its reverse transcriptase. Nat Struct Mole Biol 23: 549–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasnik I, Myong S, Cheng W, Lohman TM, Ha T. 2004. DNA-binding orientation and domain conformation of the E. coli rep helicase monomer bound to a partial duplex junction: Single-molecule studies of fluorescently labeled enzymes. J Mol Biol 336: 395–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausch JW, Le Grice SF. 2004. ‘Binding, bending and bonding’: Polypurine tract-primed initiation of plus-strand DNA synthesis in human immunodeficiency virus. Internatl J Biochem Cell Biol 36: 1752–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards RJ, Wu H, Trantirek L, O’Connor CM, Collins K, Feigon J. 2006. Structural study of elements of Tetrahymena telomerase RNA stem-loop IV domain important for function. RNA 12: 1475–1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robart AR, Collins K. 2011. Human telomerase domain interactions capture DNA for TEN domain-dependent processive elongation. Mol Cell 42: 308–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothwell PJ, Berger S, Kensch O, Felekyan S, Antonik M, Wohrl BM, Restle T, Goody RS, Seidel CA. 2003. Multiparameter single-molecule fluorescence spectroscopy reveals heterogeneity of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase:primer/template complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 1655–1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy R, Hohng S, Ha T. 2008. A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nat Methods 5: 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarafianos SG, Marchand B, Das K, Himmel DM, Parniak MA, Hughes SH, Arnold E. 2009. Structure and function of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase: Molecular mechanisms of polymerization and inhibition. J Mol Biol 385: 693–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler B, Eaton WA. 2008. Protein folding studied by single-molecule FRET. Curr Opin Struct Biol 18: 16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shastry S, Steinberg-Neifach O, Lue N, Stone MD. 2018. Direct observation of nucleic acid binding dynamics by the telomerase essential N-terminal domain. Nucleic Acids Res 46: 3088–3102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence RA, Kati WM, Anderson KS, Johnson KA. 1995. Mechanism of inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase by nonnucleoside inhibitors. Science 267: 988–993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steczkiewicz K, Zimmermann MT, Kurcinski M, Lewis BA, Dobbs D, Kloczkowski A, Jernigan RL, Kolinski A, Ginalski K. 2011. Human telomerase model shows the role of the TEN domain in advancing the double helix for the next polymerization step. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108: 9443–9448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryer L, Haugland RP. 1967. Energy transfer: A spectroscopic ruler. Proc Natl Acad Sci 58: 719–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan E, Wilson TJ, Nahas MK, Clegg RM, Lilley DM, Ha T. 2003. A four-way junction accelerates hairpin ribozyme folding via a discrete intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci 100: 9308–9313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telesnitsky A, Goff SP. 1997. Reverse transcriptase and the generation of retroviral DNA. In Retroviruses (ed. Coffin JM, Hughes SH, Varmus HE). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Temin HM, Mizutani S. 1970. RNA-dependent DNA polymerase in virions of Rous sarcoma virus. Nature 226: 1211–1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theimer CA, Feigon J. 2006. Structure and function of telomerase RNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol 16: 307–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theimer CA, Blois CA, Feigon J. 2005. Structure of the human telomerase RNA pseudoknot reveals conserved tertiary interactions essential for function. Mol Cell 17: 671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco I Jr, Gonzalez RL Jr, 2011. Biological mechanisms, one molecule at a time. Genes Dev 25: 1205–1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallweber G, Gryaznov S, Pongracz K, Pruzan R. 2003. Interaction of human telomerase with its primer substrate. Biochemistry 42: 589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JD. 1972. Origin of concatemeric T7 DNA. Nat New Biol 239: 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]